Abstract

Objectives

To assess the humoral immune response to the BNT162b2 vaccine after allogeneic haematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT).

Methods

This is a prospective cohort study. The SARS-CoV-2 IgGII Quant (Abbott©) assay was performed 4–6 weeks after the second BNT162b2 vaccine for quantitative measurement of anti-spike antibodies.

Results

The cohort included 106 adult patients. Median time from HCT to vaccination was 42 (range 4–439) months. Overall, 15/106 (14%, 95% confidence interval (CI) 7–21%) were seronegative despite vaccination, 14/52 patients on immunosuppression (27%, 95%CI 19–35%) compared to only 1/54 patients off immunosuppression (1.8%, 95%CI 1–4%) (p 0.0002). The proportion of seronegative patients declined with time; it was 46% (6/13) during the first year, 12.5% (3/24) during the second year and 9% (6/69) beyond 2 years from transplant. Patients with acute graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) (odds ratio (OR) 3.3, 95%CI 0.97–11.1, p 0.06) and moderate to severe chronic GVHD (OR 5.9, 95%CI 1.2–29, p 0.03) were more likely to remain seronegative. Vaccination was well tolerated by most patients. However, 7% (7/106) reported that GVHD-related symptoms worsened within days following vaccination.

Conclusion

A significant proportion of allogeneic HCT recipients receiving immunosuppression demonstrated an inadequate humoral response to the BNT162b2 vaccine. These patients should be recognized and instructed to take appropriate precautions. Recipients who were off immunosuppression had a humoral response that was comparable to that of the general population.

Keywords: Allogeneic haematopoietic cell transplantation, BNT162b2 vaccine, Graft-versus-host disease, Immunosuppression, SARS-CoV-2

Introduction

Compared with the general population, patients after allogeneic haematopoietic cell transplantation (alloHCT) are at higher risk of developing severe disease or dying from coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) [1]. Immunosuppressive therapy and graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) may abrogate the ability of transplanted patients to mount an adequate immune response to vaccines [2]. Immunocompromised patients were excluded from phase III trials evaluating severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) vaccines [3]. Thus, data regarding the efficacy and safety of COVID vaccines after alloHCT are lacking. In the present study, we assessed the immune response of patients after alloHCT to the BNT162b2 vaccine (Pfizer-BioNTech) and identified patient- and treatment-related factors associated with humoral response in this population.

Methods

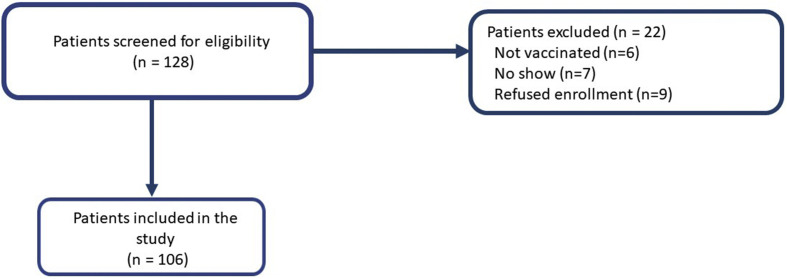

We conducted an observational prospective cohort study at the Rabin Medical Centre in Israel. It was approved by the local ethics committee. All patients signed an informed consent form after COVID-19 vaccination. Patients after alloHCT were eligible if they had no history of SARS-CoV-2 infection and received the two-dose BNT162b2 vaccine (Fig. 1 ). The SARS-CoV-2 IgG II Quant (Abbott©) assay was performed 4–6 weeks after the second vaccination for quantitative measurement of IgG antibodies to the spike protein (S-IgG) of SARS-CoV-2. The result was considered positive if the S-IgG level was ≥50 AU/mL [4].

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of patients' disposition.

We classified patients according to serological status (positive versus negative) 4 to 6 weeks after vaccination and used the likelihood ratio of the receiver-operating characteristics (ROC) curves to define the optimal cut-off for time from transplant. We used χ2 to compare variables on a categorical scale and Mann–Whitney to compare medians. To explore factors associated with seronegativity at 4–6 weeks after vaccination, we applied univariable logistic regression with age, gender and haematological diagnosis, time from transplant, acute and chronic GVHD status and immunosuppression as putative predictors. Since recovery of the immune system after transplant is time-dependent, we hypothesized that time from transplant predicts S-IgG titre levels after vaccination. To test this hypothesis, we used a linear regression model after transforming time in months and titre levels on a logarithmic scale to meet the linearity assumption of a linear model.

Results

Our cohort included 106 adult patients (Table 1 ). Overall, 15/106 (14%, 95%CI 7–21%) tested negative for S-IgG after vaccination, 14/52 patients on immunosuppression (27%, 95%CI 19–35%) compared with only 1/54 patients off immunosuppression (1.8%, 95%CI 1–4%) (p 0.0002).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Age, median (range) | All patients n = 10665 (23–80) | Seropositive n = 9166 (23–77) | Seronegative n = 1563 (25–80) | p0.54 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender, % (n) | ||||

| Male | 59 (63) | 58 (53) | 66 (10) | 0.54 |

| Female | 41 (43) | 42 (38) | 34 (5) | |

| alloHCT indication, % (n) | ||||

| Acute leukaemia | 72 (76) | 75 (68) | 53 (8) | 0.33 |

| MDS | 14 (15) | 0 | 20 (3) | |

| Lymphoma | 9 (10) | 0 | 20 (3) | |

| Other | 5 (5) | 4 (4) | 7 (4) | |

| Donor type, % (n) | ||||

| MSD | 39 (41) | 13 (12) | 33 (5) | 0.76 |

| MUD | 58 (61) | 8 (7) | 60 (9) | |

| Alternative | 3 (4) | 3 (3) | 7 (1) | |

| Conditioning intensity, % (n) | ||||

| Myeloablative | 65 (69) | 68 (62) | 48 (7) | 0.11 |

| Reduced intensity | 35 (37) | 32 (29) | 53 (8) | |

| Acute GVHD | ||||

| n (%) | 49 (52) | 46 (41) | 73 (11) | 0.05 |

| Months from GVHD to vaccination, median (range) | 25 (0–158) | 39 (0–158) | 13 (1–58) | 0.025 |

| Chronic GVHD, % (n) | ||||

| n (%) | 71 (75) | 70 (63) | 80 (12) | 0.40 |

| Months from GVHD to vaccination, median (range) | 20 (0–152) | 27 (0–152) | 8 (0–55) | 0.018 |

| Months from alloHCT, median (range) | 41.5 (4–439) | 50 (6–439) | 22 (4–60) | <0.001 |

| IS at time of vaccination, % (n) | ||||

| No IS | 51 (54) | 58 (53) | 7 (1) | <0.0001 |

| Steroids only | 23 (25) | 23 (21) | 27 (4) | |

| CNI only | 3 (3) | 1 (1) | 13 (2) | |

| CNI + steroids | 23 (24) | 18 (16) | 53 (8) | |

alloHCT, allogeneic haematopoietic cell transplantation; MDS, myelodysplastic syndrome; MSD, matched sibling donor; MUD, matched unrelated donor; GVHD, graft-versus-host disease; IS, immunosuppression; CNI, calcineurin inhibitor.

The proportion of seronegative patients declined with time from transplant; it was 46% (6/13) during the first year, 12.5% (3/24) during the second year and 9% (6/69) beyond 2 years from transplant.

We divided the cohort into patients who were transplanted within (60/106, 57%) versus beyond (46/106, 43%) 4.5 years (area under the curve: 0.77, 95%CI 0.66–0.88). With this cut-off, sensitivity was 0.93. In univariate analysis, patients vaccinated within 4.5 years of transplantation (odds ratio (OR) 13.7, 95%CI 1.8–108.5, p 0.013), still receiving immunosuppression (OR 9.8, 95%CI 2.1–44.7, p 0.004) and patients with acute GVHD (OR 3.3, 95%CI 0.97–11.1, p 0.06) or moderate to severe chronic GVHD (OR 5.9, 95%CI 1.2–29, p 0.03) were more likely to remain seronegative (Table 2 ). Age, gender, type of disease and absolute lymphocyte count were not associated with seronegativity. The median dose of prednisone among 49/106 patients on steroids (46%) at time of vaccination was 7 (1–30) mg/day. Prednisone treatment was associated with seronegativity (OR 3.8, 95%CI 1.1–12.9, p 0.03).

Table 2.

Univariate analysis of variables predicting seronegative status

| Variable | Odds ratio | 95% confidence interval |

|---|---|---|

| <4.5 y from allogeneic HCT | 13.7 | 1.8–108.5 |

| Immunosuppressive treatment | 9.8 | 2.1–44.7 |

| Moderate to severe chronic GVHD | 5.9 | 1.2–29 |

| Acute GVHD | 3.3 | 0.97–11.1 |

| Male gender | 1.4 | 0.45–4.5 |

| Age >60 years | 1 | 0.97–1.04 |

| Lymphoma versus | ||

| acute lymphoblastic leukaemia | 7.3 | 0.6–82.6 |

| acute myeloblastic leukaemia | 3.1 | 0.65–14.9 |

| myelodysplastic syndrome | 1.7 | 0.27–10.9 |

HCT, haematopoietic cell transplantation; GVHD, graft-versus-host disease.

Since 14/15 seronegative patients (93%) were transplanted within 4.5 years, we performed a subgroup analysis of the 60/106 patients (57%) who were transplanted within this time frame. Among these, patients receiving immunosuppression (39/60, 65%) were more likely to remain seronegative (OR 10, 95%CI 1.1–93, p 0.03); 14/39 patients on immunosuppression (36%) remained seronegative compared with none of the patients (21/60, 35%) off immunosuppression (p 0.002). Among the 46/106 patients who were vaccinated >4.5 years after HCT (43%), 15/46 (33%) were still receiving immunosuppression. Yet only 1/15 (6.6%) in this subgroup tested negative.

Titre levels in seropositive patients ranged between 60 and 80 000 AU/mL (median 5319). In 60/106 (57%) of our patients, subsequent serological tests were available at a median follow-up period of 4 (range 2–6) months from the second vaccination. Titre levels decreased by a median of 20% (range 13–76%) per month and consequently 4/60 patients (7%) lost humoral response during the follow-up period. We found that time from transplant explained 16% of the variance in titre levels (y = 1.27x + 1.36, R2 0.16).

Adverse events

The vaccine was well tolerated by most patients. Until now, none of our patients developed COVID-19. No new cases of GVHD have been reported following vaccination. However, seven patients with chronic GVHD (mild, n = 2; moderate, n = 1; severe, n = 4) reported that GVHD-related symptoms worsened within days following the first, second or both vaccines. Notably, one patient with severe chronic GVHD developed grade 4 steroid-refractory immune thrombocytopenia 2 weeks after the first vaccine.

Discussion

The results of the present study show that the vast majority of alloHCT recipients mounted a positive S-IgG antibody response to the two-dose BNT162b2 vaccine. Given the uncertainty regarding immunogenicity of vaccines in this immunocompromised population, these outcomes are remarkably good [5]. The results we obtained are considerably better than those reported in lung (18%), kidney (36.5%), liver (47.5%) and heart (50%) transplant recipients [[6], [7], [8], [9]]. Even after confining the analysis only to HCT recipients still receiving immunosuppression, the S-IgG antibody response proportion among HCT recipients (38/52, 73%) was still substantially superior to those reported after solid-organ transplantation.

B-cell-depleting monoclonal antibodies impair humoral response to vaccines, including the BNT1612b2 vaccine [10]. However, none of our patients received these agents during or after transplant and none received immunoglobulins.

Our study has several limitations. First, the study cohort is relatively small and any subgroup analysis is therefore exploratory in nature. Second, although we did not include patients with documented COVID-19 disease, yet we did not perform pre-vaccination serology testing. Therefore, we cannot exclude the possibility that patients with past unrecognized infection were included. Furthermore, the assay result was considered positive if S-IgG levels were ≥50 AU/mL. It should be kept in mind that this cut-off for positive antibody titre was established in healthy people. Studies are needed to determine whether this defined cut-off also applies to alloHCT recipients or whether this vulnerable population requires higher antibody titres for protection. Last, lymphocyte subpopulations, T-cell immunity and levels of neutralizing antibodies were not measured in our study.

Currently data regarding the durability of the humoral response to SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in the healthy population are scarce, and there are no data about its durability in HCT recipients [11]. Indeed, as part of the current study we intend to monitor S-IgG levels after 3, 6 and 12 months.

Although vaccination was usually well tolerated, it is worth noting that several individuals reported exacerbation of their GVHD symptoms, including one individual who developed severe immune thrombocytopenia. This is likely to have resulted from a robust vaccine-elicited immune response which may have fuelled GVHD. These findings will need to be examined in subsequent studies. It is worth mentioning that vaccinations with influenza and human papillomavirus were not associated with acute worsening of GVHD symptoms, and GVHD did not develop de novo with these vaccines [12,13].

In conclusion, the proportion of non-responders to BNT162b2 vaccine among individuals off immunosuppression, as well as those vaccinated >4.5 years after alloHCT and still receiving immunosuppression (6.5%), is similar to that of the general population. Therefore, routine serology testing after vaccination in this population is not indicated. In contrast, one third (36%) of individuals vaccinated <4.5 years after alloHCT and still receiving immunosuppression remain seronegative. These patients should be identified and instructed to take appropriate precautions. Whether a third booster dose of BNT162b2 would improve immunogenicity in seronegative patients still needs to be explored.

Author contributions

MY, OP and UR conceived the study and participated in its design and coordination. MY, OP and UR drafted the manuscript. LS, HBZ, MR and MSN were responsible for data collection. MY and UR performed the statistical analysis; DY, OW and PR participated in the interpretation of data and revised the paper critically. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Transparency declaration

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest. The study was supported by the Ministry of Health, Israel.

Editor: L. Scudeller

References

- 1.Sharma A., Bhatt N.S., St Martin A., Abid M.B., Bloomquist J., Chemaly R.F., et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of COVID-19 in haematopoietic stem-cell transplantation recipients: an observational cohort study. Lancet Haematol. 2021;8:e185–e193. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(20)30429-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Karras N.A., Weeres M., Sessions W., Xu X., Defor T., Young J.-A.H., et al. A randomized trial of one versus two doses of influenza vaccine after allogeneic transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2013;19:109–116. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2012.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Polack F.P., Thomas S.J., Kitchin N., Absalon J., Gurtman A., Lockhart S., et al. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2603–2615. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2034577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abbott laboratories . 2020. SARS-CoV-2 IgG II quant.https://www.corelaboratory.abbott/int/en/offerings/segments/infectious-disease/sars-cov-2 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Conrad A., Alcazer V., Valour F., Ader F., Lyon H.S.G., Lyon HEMINF Study Group Vaccination post-allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: what is feasible? Expert Rev Vaccines. 2018;17:299–309. doi: 10.1080/14760584.2018.1449649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shostak Y., Shafran N., Heching M., Rosengarten D., Shtraichman O., Shitenberg D., et al. Early humoral response among lung transplant recipients vaccinated with BNT162b2 vaccine. Lancet Respir Med. 2021;9:e52–e53. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00184-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rozen-Zvi B., Yahav D., Agur T., Zingerman B., Ben-Zvi H., Atamna H., et al. Antibody response to SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine among kidney transplant recipients: a prospective cohort study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2021;27:1173.e1–1173.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2021.04.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Itzhaki Ben Zadok O., Shaul A.A., Ben-Avraham B., Yaari V., Ben Zvi H., Shostak Y., et al. Immunogenicity of the BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine in heart transplant recipients – a prospective cohort study. Eur J Heart Fail. 2021;23:1555–1559. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.2199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rabinowich L., Grupper A., Baruch R., Ben-Yehoyada M., Halperin T., Turner D., et al. Low immunogenicity to SARS-CoV-2 vaccination among liver transplant recipients. J Hepatol. 2021;75:435–438. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2021.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gurion R., Rozovski U., Itchaki G., Gafter-Gvili A., Leibovitch C., Raanani P., et al. Humoral serologic response to the BNT162b2 vaccine is abrogated in lymphoma patients within the first 12 months following treatment with anti-CD2O antibodies. Haematologica. 2021 doi: 10.3324/haematol.2021.279216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Widge A.T., Rouphael N.G., Jackson L.A., Anderson E.J., Roberts P.C., Chappell J.D., et al. Durability of responses after SARS-CoV-2 mRNA-1273 vaccination. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:80–82. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2032195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stratton P., Battiwalla M., Tian X., Abdelazim S., Baird K., Barrett A.J., et al. Immune response following quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccination in women after hematopoietic allogeneic stem cell transplant: a nonrandomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6:696–705. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.6722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ditschkowski M., Elmaagacli A.H., Beelen D.W. H1N1 in allogeneic stem cell recipients: courses of infection and influence of vaccination on graft-versus- host-disease (GVHD) Ann Hematol. 2011;90:117–118. doi: 10.1007/s00277-010-0971-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]