Abstract

Nicotinamide recycling is critical to the development and function of Caenorhabditis elegans. Excess nicotinamide in a pnc-1 nicotinamidase mutant causes the necrosis of uv1 and OLQ cells and a highly penetrant egg laying defect. An EGF receptor (let-23) gain-of-function mutation suppresses the Egl phenotype in pnc-1 animals. However, gain-of-function mutations in either of the known downstream mediators, let-60/ Ras or itr-1, are not sufficient. Phosphatidylcholine synthesis is neither required nor sufficient, in contrast to its role in the let-23gf rescue of uv1 necrosis. The mechanism behind the let-23gf suppression of the pnc-1 Egl phenotype is unknown.

Figure 1.

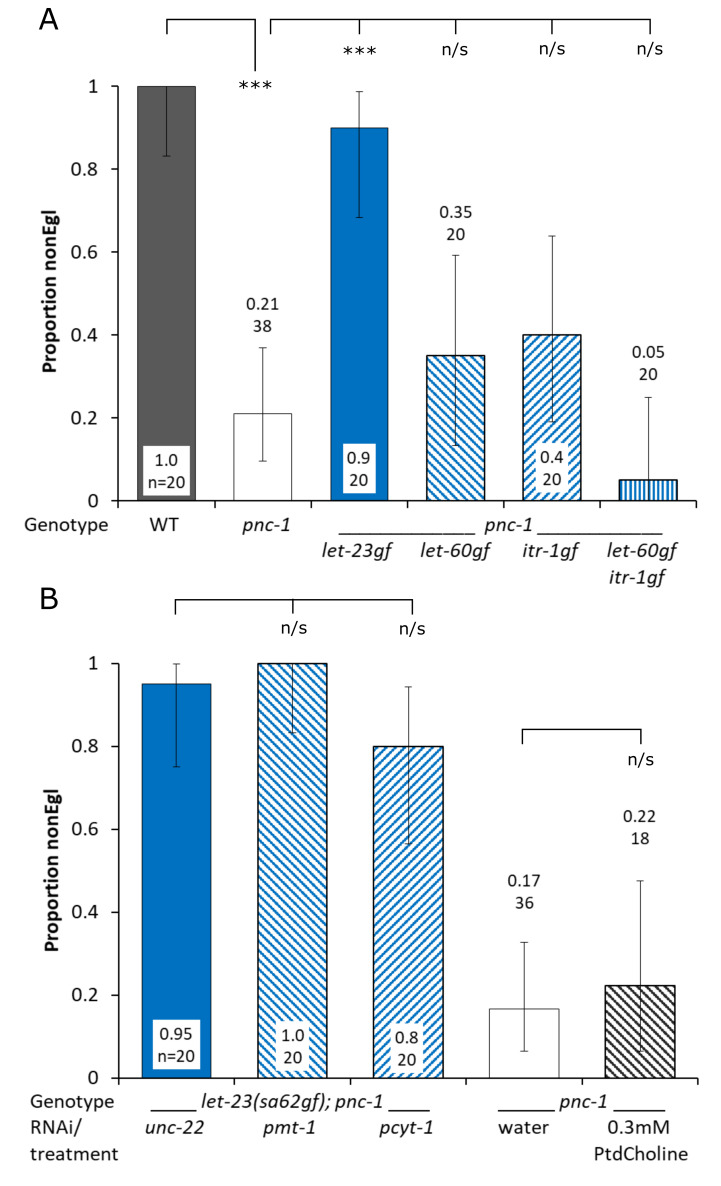

A let-23(sa62)gf mutation in C. elegans strongly suppresses a pnc-1(pk9605) egg-laying (Egl) phenotype, where adult pnc-1(pk9605) hermaphrodites form “bags of worms” by four days post L4>adult molt. A) A gain-of-function mutation in let-23 is sufficient to rescue the pnc-1 Egl phenotype, but gain-of-function mutations in downstream genes let-60 and/ or itr-1 are not. B) Phosphatidylcholine synthesis is neither required nor sufficient for the let-23(ga62)gf rescue of the pnc-1 Egl phenotype. WT = wild-type C. elegans N2 Bristol strain. Error bars are 95% confidence intervals, with proportion and sample size in the data labels. Proportions were analysed by pairwise.prop.test in R with Holm p value adjustment; *** and n/s represent p<0.0001 and non-significant, respectively.

Description

NAD+ is an electron carrier and a co-substrate for NAD+-dependent enzymes such as poly(ADP-ribose) polymerases (Bouchard et al. 2003; Sauve 2008). The byproduct of these enzymatic reactions, nicotinamide (NAM), must be salvaged to maintain a readily available NAD+ pool. In Caenorhabditis elegans the nicotinamidase PNC-1 acts both cell autonomously and non-cell autonomously to convert NAM into nicotinic acid (NA), an NAD+ precursor in this organism (Huang and Hanna-Rose 2006; Vrablik et al. 2009; Crook et al. 2014). Loss of PNC-1 function affects NAD+ pathway metabolites in two ways. It results in an increase in NAM, causing necrosis of OLQ and uv1 cells, and an egg-laying phenotype due to reduced muscle function. It also reduces NAD+ levels, resulting in gonad developmental delay and a male mating defect (Huang and Hanna-Rose 2006; Vrablik et al. 2009; Vrablik et al. 2011; Upadhyay et al. 2016).

LET-23 is the sole C. elegans Epidermal Growth Factor (EGF) receptor and is involved in a range of biological and developmental processes, including vulval development and specification of the uv1 cells (Chang et al. 1999; Moghal and Sternberg 2003). A gain-of-function mutation in the extracellular domain, let-23(sa62)gf, results in precocious activation of LET-23 independent of its EGF ligand LIN-3 (Katz et al. 1996).Overactivation of LET-23 rescues the uv1 cell necrosis phenotype of pnc-1 loss-of-function mutants, and this rescue requires phosphatidylcholine synthesis (Huang and Hanna-Rose 2006; Crook et al. 2016; Crook and Hanna-Rose 2020). We noted that the egg-laying phenotype of pnc-1 was also ameliorated by overactivation of LET-23 and decided to investigate the mechanism.

To study the role of EGF signaling in the prevention of the egg-laying phenotype we placed individual L4 hermaphrodites on Nematode Growth Medium (NGM) agar plates spotted with Escherichia coli OP50. Individual animals were observed after two, three and four days at 20C and scored as non-Egg laying defective (nonEgl) adults or “bags of worms” (Egl), where larvae hatch in the uterus due to a failure to lay eggs. Proportion nonEgl was calculated as the number nonEgl adults/ total number of individuals at day four. All nonEgl adults had laid eggs by day 4. We found that the pnc-1(pk9605) loss-of-function allele reduced the proportion of nonEgl adults to 0.21 and that the let-23(sa62) gain-of-function (gf) allele in a pnc-1(pk9605) background restored that to 0.9 (Fig. 1a). However, gain-of-function mutations in let-60 or itr-1, which mediate signal transduction downstream of let-23 (Clandinin et al. 1998; Chang et al. 1999), had no effect on the pnc-1 egg-laying phenotype (Fig. 1a).

Phosphatidylcholine synthesis is required for let-23(sa62)gf mediated rescue of uv1 necrosis and exogenous phosphatidylcholine alone is partially sufficient for uv1 survival (Crook et al. 2016). PMT-1 is part of the Sequential Methylation Pathway (SMP) that synthesizes phosphocholine (Brendza et al. 2007), and PCYT-1 turns phosphocholine from the Sequential Methylation and Kennedy pathways into CDP-choline, the precursor of phosphatidylcholine (Kennedy and Weiss 1956). To test if phosphatidylcholine synthesis was required for the let-23(sa62)gf-mediated rescue of the pnc-1 egg-laying phenotype we knocked down pmt-1 or pcyt-1 by RNAi. unc-22 (control), pmt-1 and pcyt-1 RNAi bacterial cultures were spotted onto NGM plates containing 50 μg.ml-1 ampicillin and 1 mM IPTG, then individual L4 hermaphrodites were added to each plate and scored as above. We found that neither pmt-1 nor pcyt-1 were required for rescue in a let-23(sa62)gf; pnc-1(pk9605) background (Fig. 1b). pmt-1 or pcyt-1 RNAi did however reduce uv1 cell survival in nonEgl adults in experiments run concurrently with this project (Crook et al. 2016), suggesting that RNAi knockdown of the target genes was effective. Next, we wanted to see if phosphatidylcholine alone was sufficient for rescue, as it ameliorates the uv1 necrosis phenotype (Crook et al. 2016). We supplemented pnc-1 animals with 0.3 mM phosphatidylcholine but found no effect on the pnc-1 egg-laying phenotype (Fig. 1b).

We have shown that overactivation of the C. elegans let-23 EGF receptor robustly rescues the pnc-1 egg-laying phenotype, but that gain-of-function mutations in the known downstream signaling mediators let-60/ Ras and itr-1 are not sufficient. Phosphatidylcholine synthesis is not required for the let-23(sa62)gf rescue of the egg-laying phenotype and phosphatidylcholine supplementation of pnc-1 had no significant effect at the sample sizes used, in contrast to the role of phosphatidylcholine in let-23(sa62)gf rescue of uv1 necrosis. We have clearly demonstrated another role for let-23 outside that of growth and development. However, the mechanism by which overactive LET-23 rescues egg-laying in pnc-1 animals is not clear. LET-23 may act via an as yet unknown pathway that restores uterine or vulval muscle function by either reducing the production of nicotinamide in those tissues or promoting some other compensatory mechanism.

Reagents

Strains:

N2 Bristol

BL5715 inIs179 (ida-1::gfp) II

HV560 inIs179 (ida-1::gfp) II; pnc-1(pk9605) IV

HV639 inIs179 (ida-1::gfp) II; pnc-1(pk9605) let-60(n1046gf) itr-1(sy290gf) unc-24(e138) IV

HV662 inIs179 (ida-1::gfp) II; pnc-1(pk9605) let-60(n1046gf) IV

HV663 inIs179 (ida-1::gfp) II; pnc-1(pk9605) itr-1(sy290gf) unc-24(e138) IV

HV776 let-23(sa62gf) inIs179(ida-1p::gfp) II; pnc-1(pk9605) IV

The strains used in this study are available from the authors upon request.

We used the following clones from the Ahringer RNAi library: pmt-1 ZK622.3 II-4G04, pcyt-1 F08C6.2 X-3N20, unc-22 ZK617.1 IV-6K06.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

Some strains used to make the strains in this study were provided by the CGC, which is funded by NIH Office of Research Infrastructure Programs (P40 OD010440).

Funding

R01GM086786

References

- Bouchard VJ, Rouleau M, Poirier GG. PARP-1, a determinant of cell survival in response to DNA damage. Exp Hematol. 2003 Jun 01;31(6):446–454. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(03)00083-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brendza KM, Haakenson W, Cahoon RE, Hicks LM, Palavalli LH, Chiapelli BJ, McLaird M, McCarter JP, Williams DJ, Hresko MC, Jez JM. Phosphoethanolamine N-methyltransferase (PMT-1) catalyses the first reaction of a new pathway for phosphocholine biosynthesis in Caenorhabditis elegans. Biochem J. 2007 Jun 15;404(3):439–448. doi: 10.1042/BJ20061815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang C, Newman AP, Sternberg PW. Reciprocal EGF signaling back to the uterus from the induced C. elegans vulva coordinates morphogenesis of epithelia. Curr Biol. 1999 Mar 11;9(5):237–246. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80112-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clandinin TR, DeModena JA, Sternberg PW. Inositol trisphosphate mediates a RAS-independent response to LET-23 receptor tyrosine kinase activation in C. elegans. Cell. 1998 Feb 20;92(4):523–533. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80945-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crook M, Hanna-Rose W. Overactive EGF signaling promotes uv1 cell survival via increased phosphatidylcholine levels and suppression of SBP-1. MicroPubl Biol. 2020 Jun 29;2020 doi: 10.17912/micropub.biology.000266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crook M, Upadhyay A, Ido LJ, Hanna-Rose W. Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Cell Survival Signaling Requires Phosphatidylcholine Biosynthesis. G3 (Bethesda) 2016 Nov 01;6(11):3533–3540. doi: 10.1534/g3.116.034850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crook M, Mcreynolds MR, Wang W, Hanna-Rose W. An NAD(+) biosynthetic pathway enzyme functions cell non-autonomously in C. elegans development. Dev Dyn. 2014 May 10;243(8):965–976. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.24139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L, Hanna-Rose W. EGF signaling overcomes a uterine cell death associated with temporal mis-coordination of organogenesis within the C. elegans egg-laying apparatus. Dev Biol. 2006 Aug 12;300(2):599–611. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz WS, Lesa GM, Yannoukakos D, Clandinin TR, Schlessinger J, Sternberg PW. A point mutation in the extracellular domain activates LET-23, the Caenorhabditis elegans epidermal growth factor receptor homolog. Mol Cell Biol. 1996 Feb 01;16(2):529–537. doi: 10.1128/MCB.16.2.529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KENNEDY EP, WEISS SB. The function of cytidine coenzymes in the biosynthesis of phospholipides. J Biol Chem. 1956 Sep 01;222(1):193–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moghal N, Sternberg PW. The epidermal growth factor system in Caenorhabditis elegans. Exp Cell Res. 2003 Mar 10;284(1):150–159. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4827(02)00097-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauve AA. NAD+ and vitamin B3: from metabolism to therapies. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007 Dec 28;324(3):883–893. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.120758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Upadhyay A, Pisupati A, Jegla T, Crook M, Mickolajczyk KJ, Shorey M, Rohan LE, Billings KA, Rolls MM, Hancock WO, Hanna-Rose W. Nicotinamide is an endogenous agonist for a C. elegans TRPV OSM-9 and OCR-4 channel. Nat Commun. 2016 Oct 12;7:13135–13135. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vrablik TL, Wang W, Upadhyay A, Hanna-Rose W. Muscle type-specific responses to NAD+ salvage biosynthesis promote muscle function in Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Biol. 2010 Nov 16;349(2):387–394. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vrablik TL, Huang L, Lange SE, Hanna-Rose W. Nicotinamidase modulation of NAD+ biosynthesis and nicotinamide levels separately affect reproductive development and cell survival in C. elegans. Development. 2009 Nov 01;136(21):3637–3646. doi: 10.1242/dev.028431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]