Abstract

Through aging, D. melanogaster males and females change their social spacing. Flies are initially more social, but reduce sociability as they grow older. This preferred social space is inherited in their progeny. Here, we report that in females, the profiles of cuticular hydrocarbons (CHC), which are known to promote social interaction between individuals, similarly are affected by age. Importantly, for a subset of those CHC, the progeny’s CHC levels are comparable to those of their parents, suggesting that parental age influences offspring CHC expression. Those data establish a foundation to identify the relationship between CHC levels and social spacing, and to understand the mechanisms of the inheritance of complex traits.

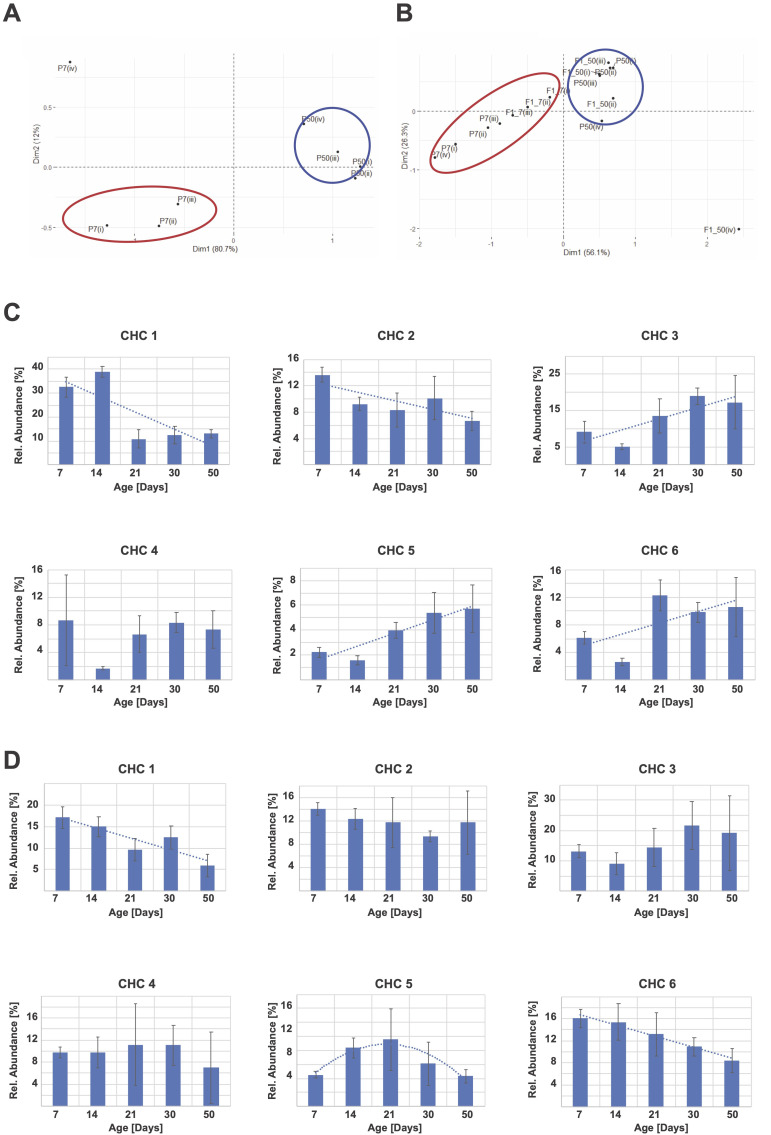

Figure 1. Age-dependent CHC patterns may be inherited to the F1 generation.

A) PCA analysis of CHC amounts of young (7 days old, red circles) and old female flies (50 days old, blue circles) cluster in distinct regions of the PCA graph, suggesting age-dependent changes of CHC expression levels.

B)CHC amounts in young 7 days old offspring of 50-day-old parents (blue circles, P50 and F1_50) cluster in different PCA graph areas compared to flies of the same age of 7 days , and offspring of young 7 days old parents (red circles, P7 and F1_7). P: female parents; F1_X: F1 female offspring of the female parents of the indicated ages; roman numerals depict individual replicates.

C) Age affects CHC expression levels in female flies. Flies of the indicated ages were analyzed for CHC expression. CHC are shown in proportional representation of each CHC peak and depicted as “% of total CHC”. Trendlines are shown as dotted lines for CHC with a of p<0.05 for age correlation.

D) Age-dependent changes to CHC expression in females may be transmitted to their female offspring. 7-day-old female offspring of parents of the indicated ages were analyzed for CHC profiles. Most CHC are unchanged, regardless of parental age. A few CHC show deviations from day 7 expression levels (best fit trendlines are shown for CHC with a p<0.05 for parental age correlation.

Description

Pheromones modulate social behaviors like aggregation, aggression, attraction, foraging, group behavior and courtshipin insects (Amrein 2004; Antony et al. 1985; Billeter et al. 2012; Bontonou and Wicker-Thomas 2014; Fletcher 1968; Greene and Gordon 2003; Krupp et al. 2008; Lebreton et al. 2012; Lu and Teal 2001; Pankiw 2004; Smedal et al. 2009; Wang and Anderson 2010). Molecularly, many pheromones are long-chain hydrocarbons that differ in chain length and saturation status and have recently been proposed to also play a role in the regulation of aging and longevity. For example, the brood pheromone of the honeybee A. mellifera has been shown to suppress extreme longevity (Smedal et al. 2009), and pheromone sensing is associated with modulation of life span in the roundworm C. elegans (Kawano et al. 2005; Ludewig et al. 2013). In the vinegar fly Drosophila melanogaster, most pheromones are produced by specialized cells called oenocytes (for review see Martins and Ramalho-Ortigao 2012) that are associated with the fly fat body. Following synthesis, those fly pheromones are displayed on the cuticle of the animal and referred to as cuticular hydrocarbons (CHC). CHC profiles change with increasing age (Kuo et al. 2012), and altering CHC levels in the adult changes both mating behavior and longevity (Joseph et al. 2018). In addition, the putative pheromone co-receptor Or83b has been shown to affect fly life span (Libert et al. 2007). Finally, male D. melanogaster prefer younger females to older females, and this evaluation is largely made through the females age-specific CHC profiles (Kuo et al. 2012). Together, these data suggest that pheromone levels may be related to aging and longevity and may thus serve as aging biomarkers (Yew and Chung 2015).

Some health traits, such as onset of diabetes, weight or even longevity, have been suggested to be transmitted to subsequent generations by epigenetic-inheritance mechanisms. Data obtained from an isolated human population in Sweden shows that parental diet influences the longevity of their offspring (Bygren et al. 2001; Kaati et al. 2007). Furthermore, health traits, especially the development of diabetes, were also transmitted to the next generation (Kaati et al. 2002). Data obtained in mice suggests that a paternal low-protein diet leads to epigenetic changes that are transmitted to the offspring (Carone et al. 2010), while a maternal high-fat diet leads to increased body size that persists into the F3 generation in mice (Dunn and Bale 2011). Importantly, manipulation of genes involved in epigenetic modification has been shown to change parental longevity in the nematode C. elegans, which can be transmitted for several generations (Greer et al. 2010). Epigenetic inheritance may affect not just metabolism, but even behavioral traits, such as learning and memory, mating and courtship, and circadian behaviour (for review Shimaji et al. 2019), from mice to Drosophila. And in Drosophila, young progeny of old D. melanogaster maintain a social spacing behavior that is similar to the behavior of old parents, rather than resembling the behavior of young flies (Brenman-Suttner et al. 2018). Together, these data suggest that social behavior may be an age-dependent and epigenetically-inherited trait, with implications for the aging process as well.

Social spacing is the preferred distance between individuals of an undisturbed group, and is a very basic form of social interaction, that probably takes place before more complex behaviors such as aggression or mating. Social spacing is maintained through a balance between attractive and repulsive cues, possibly including, but not limited to, vision but not classical olfaction (Simon et al. 2012). How the central nervous system is underlying the decision process of spacing has been investigated: A sex specific neural circuit is emerging as a modulator of social spacing. It involves dopaminergic signalling (Fernandez et al. 2017, Xie et al. 2018), and cholinergic neurons of the mushroom body (Burg et al. 2013). At the synaptic level, Neurobeachin (an anchor protein- Wise et al. 2015) and Neuroligin (a cell adhesion protein – Yost et al. 2020) are implicated in social space, as well. Finally, FoxP, a highly conserved transcription factor associated to human neurodevelopmental and speech disorders, is also crucial in flies for their control of social spacing (Castells-Nobau et al. 2019). However, we do not know which of the perceived cues lead to appropriate social spacing. Because CHC modulate behavior (Wang et al. 2008), including group formation, and CHC profiles are themselves altered by social experience (Everaerts et al. 2010; Kent et al. 2008; Krupp et al. 2008; Yew and Chung 2017), it is possible that CHC also play a role in social spacing within a stable group.

As social-spacing is inherited (Brenman-Suttner et al. 2018), we hypothesized that some CHC may similarly be affected by epigenetic inheritance. Furthermore, CHC expression profile changes may be preserved in the first generation offspring of old parents (50 days old). If so, inherited effects on CHC production may underlie the observed shift in social spacing. In this study, we measured age-dependent CHC expression of adult D. melanogaster throughout their life span. We then compared CHC expression profiles of aging flies to the CHC profiles of their respective young offspring to determine whether F1 CHC profiles were more similar to the profiles of young or aged parents. Here we focused on females, but further work will address male CHC profiles. In this study, we report the results of our first observations on six unidentified CHCs.

We conducted Principal Component Analysis (PCA) of pheromone profiles of young (7 days old) and old flies (50 days old), and their respective offspring to test whether parental age affects CHC expression patterns. Profiles of young and old flies cluster in distinct regions of the PCA analysis, indicating that pheromone expression patterns change with age, as has been reported previously (Figure 1A; Kuo et al. 2012). Interestingly, when the pheromone profiles of 7 days old offspring of the respectively aged parents are included in the PCA, the distinct clustering is largely retained (Fig. 1B). These data suggest that the CHC profile of young F1 offspring of young parents is similar to the profile of young parents, while the profile of young F1 offspring to old parents is likewise similar to the old parental CHC profile. Since all offspring were measured at 7 days of age, these data demonstrate that age-dependent CHC profile changes are inherited to the offspring, presumably via an epigenetic mechanism.

Next, we investigated the nature of the age-dependent CHC profile changes by analyzing six unidentified CHCs present at all ages in all samples (see methods). Depending on the CHC under observation, CHC abundance may not change, increase, or decrease with age (Fig. 1C). In order to elucidate further how age-dependent CHC changes may be transmitted, we then analyzed those same CHC in the 7 days old offspring. As expected, most CHCs do not show different expression levels based on the parental age. However, in a small number of cases, F1 CHCs levels are dependent on parental age (Fig. 1D), suggesting that age-dependent expression changes are transmitted to the offspring of these aging flies.

We have recently shown that social avoidance behavior may be an epigenetically inherited trait in vinegar flies (Brenman-Suttner et al. 2018). Because behaviors are mediated by pheromones, here we investigated whether pheromone expression levels could likewise be epigenetically inherited. Our data show that the expression level of some pheromones depends on parental expression levels, although not for the majority of CHC. Our results provide a possible explanation for previously observed epigenetically inherited behavioral changes in social spacing. This also suggests that other traits associated with these specific CHC, such as specific behaviors or even longevity, could similarly be inherited. Additional studies will be necessary to identify each CHC, and potentially confirm their involvement in social spacing. However, our data provides supporting evidence for the inheritance of complex traits, and a starting point to investigate the molecular mechanisms of this effect.

Methods

Aging fly stock: As reported by Brenman-Suttner et al. (2018). In short, ourlaboratory control strain Canton-S Drosophila melanogaster was reared in mixed sex groups in bottles over Jazz Mix media (brown sugar, corn meal, yeast, agar, benzoic acid, methyl paraben and propionic acid; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). All flies were maintained at 25°C, 50% humidity with a 12:12 light: dark cycle, lights on at 08:00. New bottles were made bi-weekly when the parents were less than seven days old. After 5 days of laying eggs, existing flies in bottles were removed to prevent new emerging flies cohabitating with their parents. As soon as the flies started emerging, they were collected from the bottles (40 flies/vial, with approximately equal number of males and females, 7 vials/week) under cold anesthesia. Flies were transferred to new media in vials every two-to-three day and were maintained for up to seven weeks.

Generating the progeny of old parents: As described above, the old flies were generated through maintaining Canton-S Drosophila melanogaster and transferring them to new food every two days. At different ages (7, 14, 21, 30 and 50 days), their progeny were saved and allowed to develop to adulthood (F1: first generation).

Preparation of flies for CHC extraction: As described in Pardy et al. (2019). In short, 5 Drosophila melanogaster females aged 7, 14, 21, 30, and 50 days were collected under cold anesthesia and placed in Eppendorf tubes in a -4°C freezer. The 7 days old female progeny of parents aged 7, 14, 21, 30, and 50 days were also collected and frozen in batches of 5 until later use. We collected at least 3 replicates for each sample.

CHC extraction: As described in Pardy et al. (2019). In short, the three replicates of 5 frozen flies per treatment were washed 100 μl hexane and then the fly body was removed and discarded. Octadecane (C18) and n-hexacosane (C26) were added to the extract as internal standards (10 ng/μl). Samples were analyzed on an Agilent Technologies (Wilmington, USA) 6890 N dual channel gas chromatograph (GC). Hydrogen was used as the carrier gas.

CHC profile analysis: Samples were normalized to the internal standard and a 5% threshold was applied to filter out noise. PCA analysis was then performed using the open software suite RStudio (https://www.rstudio.com/; RRID:SCR_000432) and the factoextra package function. The PCA analysis was performed using approximately 37 individual elution peaks, that were present in at least 2 of our biological replicates.

For analysis of age-dependence of CHC levels, after removal of peaks inconsistent between replicates, noise-corrected GC peaks were re-normalized to total peak intensity. We then applied exclusion criteria: the peaks we focused on had to be present in each of our biological replicates (16 out of the 37 peaks – which was linked to their abundance), as well at all ages tested. Only 6 peaks fulfilled those criteria, and we analyzed their variation with age as a % of total CHC.

Statistical Analysis: Statistical analyses, including One-way ANOVA for CHC age-dependence, were performed using the Prism suite of biostatistical software (GraphPad, San Diego; RRID:SCR_002798).

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Nathalia Vilchis, Rashmita Singh, Hermione Xian and Brian Chow for their help in curating the GC data sets.

Funding

This work was supported by NSERC Discovery Grant RGPIN-2015-06773 to A.J.M., RGPIN-2015-04275 to A.F.S. J.H.B. was supported by the Sac State Center for Interdisciplinary Molecular Biology: Education, Research and Advance (CIMERA), and a Sac State Research and Creative Activity (RCA) Award. A.G.M. is a Sac State RISE Scholar.

References

- Amrein H. Pheromone perception and behavior in Drosophila. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2004 Aug 01;14(4):435–442. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2004.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antony C, Davis TL, Carlson DA, Pechine JM, Jallon JM. Compared behavioral responses of maleDrosophila melanogaster (Canton S) to natural and synthetic aphrodisiacs. J Chem Ecol. 1985 Dec 01;11(12):1617–1629. doi: 10.1007/BF01012116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billeter JC, Jagadeesh S, Stepek N, Azanchi R, Levine JD. Drosophila melanogaster females change mating behaviour and offspring production based on social context. Proc Biol Sci. 2012 Feb 01;279(1737):2417–2425. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2011.2676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bontonou G, Wicker-Thomas C. Sexual Communication in the Drosophila Genus. Insects. 2014 Jun 18;5(2):439–458. doi: 10.3390/insects5020439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenman-Suttner DB, Long SQ, Kamesan V, de Belle JN, Yost RT, Kanippayoor RL, Simon AF. Progeny of old parents have increased social space in Drosophila melanogaster. Sci Rep. 2018 Feb 27;8(1):3673–3673. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-21731-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burg ED, Langan ST, Nash HA. Drosophila social clustering is disrupted by anesthetics and in narrow abdomen ion channel mutants. Genes Brain Behav. 2013 Mar 11;12(3):338–347. doi: 10.1111/gbb.12025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bygren LO, Kaati G, Edvinsson S. Longevity determined by paternal ancestors' nutrition during their slow growth period. Acta Biotheor. 2001 Mar 01;49(1):53–59. doi: 10.1023/a:1010241825519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carone BR, Fauquier L, Habib N, Shea JM, Hart CE, Li R, Bock C, Li C, Gu H, Zamore PD, Meissner A, Weng Z, Hofmann HA, Friedman N, Rando OJ. Paternally induced transgenerational environmental reprogramming of metabolic gene expression in mammals. Cell. 2010 Dec 23;143(7):1084–1096. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castells-Nobau A, Eidhof I, Fenckova M, Brenman-Suttner DB, Scheffer-de Gooyert JM, Christine S, Schellevis RL, van der Laan K, Quentin C, van Ninhuijs L, Hofmann F, Ejsmont R, Fisher SE, Kramer JM, Sigrist SJ, Simon AF, Schenck A. Conserved regulation of neurodevelopmental processes and behavior by FoxP in Drosophila. PLoS One. 2019 Feb 12;14(2):e0211652–e0211652. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0211652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn GA, Bale TL. Maternal high-fat diet effects on third-generation female body size via the paternal lineage. Endocrinology. 2011 Mar 29;152(6):2228–2236. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-1461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everaerts C, Farine JP, Cobb M, Ferveur JF. Drosophila cuticular hydrocarbons revisited: mating status alters cuticular profiles. PLoS One. 2010 Mar 01;5(3):e9607–e9607. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez RW, Akinleye AA, Nurilov M, Feliciano O, Lollar M, Aijuri RR, O'Donnell JM, Simon AF. Modulation of social space by dopamine in Drosophila melanogaster, but no effect on the avoidance of the Drosophila stress odorant. Biol Lett. 2017 Aug 01;13(8) doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2017.0369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher BS. Storage and release of a sex pheromone by the Queensland fruit fly, Dacus tryoni (Diptera: Trypetidae). Nature. 1968 Aug 10;219(5154):631–632. doi: 10.1038/219631a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene MJ, Gordon DM. Social insects: Cuticular hydrocarbons inform task decisions. Nature. 2003 May 01;423(6935):32–32. doi: 10.1038/423032a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greer EL, Maures TJ, Hauswirth AG, Green EM, Leeman DS, Maro GS, Han S, Banko MR, Gozani O, Brunet A. Members of the H3K4 trimethylation complex regulate lifespan in a germline-dependent manner in C. elegans. Nature. 2010 Jun 16;466(7304):383–387. doi: 10.1038/nature09195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph NM, Elphick NY, Mohammad S, Bauer JH. Altered pheromone biosynthesis is associated with sex-specific changes in life span and behavior in Drosophila melanogaster. Mech Ageing Dev. 2018 Oct 10;176:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2018.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaati G, Bygren LO, Pembrey M, Sjöström M. Transgenerational response to nutrition, early life circumstances and longevity. Eur J Hum Genet. 2007 Apr 25;15(7):784–790. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaati G, Bygren LO, Edvinsson S. Cardiovascular and diabetes mortality determined by nutrition during parents' and grandparents' slow growth period. Eur J Hum Genet. 2002 Nov 01;10(11):682–688. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawano T, Kataoka N, Abe S, Ohtani M, Honda Y, Honda S, Kimura Y. Lifespan extending activity of substances secreted by the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans that include the dauer-inducing pheromone. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2005 Dec 01;69(12):2479–2481. doi: 10.1271/bbb.69.2479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent C, Azanchi R, Smith B, Formosa A, Levine JD. Social context influences chemical communication in D. melanogaster males. Curr Biol. 2008 Sep 11;18(18):1384–1389. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.07.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krupp JJ, Kent C, Billeter JC, Azanchi R, So AK, Schonfeld JA, Smith BP, Lucas C, Levine JD. Social experience modifies pheromone expression and mating behavior in male Drosophila melanogaster. Curr Biol. 2008 Sep 11;18(18):1373–1383. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.07.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo TH, Yew JY, Fedina TY, Dreisewerd K, Dierick HA, Pletcher SD. Aging modulates cuticular hydrocarbons and sexual attractiveness in Drosophila melanogaster. J Exp Biol. 2012 Mar 01;215(Pt 5):814–821. doi: 10.1242/jeb.064980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebreton S, Becher PG, Hansson BS, Witzgall P. Attraction of Drosophila melanogaster males to food-related and fly odours. J Insect Physiol. 2011 Oct 31;58(1):125–129. doi: 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2011.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Libert S, Zwiener J, Chu X, Vanvoorhies W, Roman G, Pletcher SD. Regulation of Drosophila life span by olfaction and food-derived odors. Science. 2007 Feb 01;315(5815):1133–1137. doi: 10.1126/science.1136610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu F, Teal PE. Sex pheromone components in oral secretions and crop of male Caribbean fruit flies, Anastrepha suspensa (Loew). Arch Insect Biochem Physiol. 2001 Nov 01;48(3):144–154. doi: 10.1002/arch.1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludewig AH, Izrayelit Y, Park D, Malik RU, Zimmermann A, Mahanti P, Fox BW, Bethke A, Doering F, Riddle DL, Schroeder FC. Pheromone sensing regulates Caenorhabditis elegans lifespan and stress resistance via the deacetylase SIR-2.1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013 Mar 18;110(14):5522–5527. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1214467110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martins GF, Ramalho-Ortigao JM. 2012. Oenocytes in insects. Invert Survival Journal 9: 139-152.

- Pankiw T. Worker honey bee pheromone regulation of foraging ontogeny. Naturwissenschaften. 2004 Feb 27;91(4):178–181. doi: 10.1007/s00114-004-0506-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimaji K, Tomida S, Yamaguchi M. Regulation of animal behavior by epigenetic regulators. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 2019 Mar 01;24:1071–1084. doi: 10.2741/4769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon AF, Chou MT, Salazar ED, Nicholson T, Saini N, Metchev S, Krantz DE. A simple assay to study social behavior in Drosophila: measurement of social space within a group. Genes Brain Behav. 2011 Nov 23;11(2):243–252. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2011.00740.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smedal B, Brynem M, Kreibich CD, Amdam GV. Brood pheromone suppresses physiology of extreme longevity in honeybees (Apis mellifera). J Exp Biol. 2009 Dec 01;212(Pt 23):3795–3801. doi: 10.1242/jeb.035063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Anderson DJ. Identification of an aggression-promoting pheromone and its receptor neurons in Drosophila. Nature. 2009 Dec 01;463(7278):227–231. doi: 10.1038/nature08678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Dankert H, Perona P, Anderson DJ. A common genetic target for environmental and heritable influences on aggressiveness in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008 Apr 11;105(15):5657–5663. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801327105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise A, Tenezaca L, Fernandez RW, Schatoff E, Flores J, Ueda A, Zhong X, Wu CF, Simon AF, Venkatesh T. Drosophila mutants of the autism candidate gene neurobeachin (rugose) exhibit neuro-developmental disorders, aberrant synaptic properties, altered locomotion, and impaired adult social behavior and activity patterns. J Neurogenet. 2015 Jul 14;29(2-3):135–143. doi: 10.3109/01677063.2015.1064916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie T, Ho MCW, Liu Q, Horiuchi W, Lin CC, Task D, Luan H, White BH, Potter CJ, Wu MN. A Genetic Toolkit for Dissecting Dopamine Circuit Function in Drosophila. Cell Rep. 2018 Apr 10;23(2):652–665. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.03.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yew JY, Chung H. Drosophila as a holistic model for insect pheromone signaling and processing. Curr Opin Insect Sci. 2017 Sep 14;24:15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cois.2017.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yew JY, Chung H. Insect pheromones: An overview of function, form, and discovery. Prog Lipid Res. 2015 Jun 14;59:88–8105. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2015.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yost RT, Robinson JW, Baxter CM, Scott AM, Brown LP, Aletta MS, Hakimjavadi R, Lone A, Cumming RC, Dukas R, Mozer B, Simon AF. Abnormal Social Interactions in a Drosophila Mutant of an Autism Candidate Gene: Neuroligin 3. Int J Mol Sci. 2020 Jun 29;21(13) doi: 10.3390/ijms21134601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]