Abstract

The NF-κB/Rel family of eukaryotic transcription factors plays an essential role in the regulation of inflammatory, antiapoptotic, and immune responses. NF-κB is activated by many stimuli including costimulation of T cells with ligands specific for the T-cell receptor (TCR)-CD3 complex and CD28 receptors. However, the signaling intermediates that transduce these costimulatory signals from the TCR-CD3 and CD28 surface receptors leading to nuclear NF-κB expression are not well defined. We now show that protein kinase C-θ (PKC-θ), a novel PKC isoform, plays a central role in a signaling pathway induced by CD3-CD28 costimulation leading to activation of NF-κB in Jurkat T cells. We find that expression of a constitutively active mutant of PKC-θ potently induces NF-κB activation and stimulates the RE/AP composite enhancer from the interleukin-2 gene. Conversely, expression of a kinase-deficient mutant or antisense PKC-θ selectively inhibits CD3-CD28 costimulation, but not tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced activation of NF-κB in Jurkat T cells. The induction of NF-κB by PKC-θ is mediated through the activation of IκB kinase β (IKKβ) in the absence of detectable IKKα stimulation. PKC-θ acts directly or indirectly to stimulate phosphorylation of IKKβ, leading to activation of this enzyme. Together, these results implicate PKC-θ in one pathway of CD3-CD28 costimulation leading to NF-κB activation that is apparently distinct from that involving Cot and NF-κB-inducing kinase (NIK). PKC-θ activation of NF-κB is mediated through the selective induction of IKKβ, while the Cot- and NIK-dependent pathway involves induction of both IKKα and IKKβ.

NF-κB constitutes a family of Rel domain-containing transcription factors that play essential roles in the regulation of inflammatory, antiapoptotic, and immune responses (1, 4). The function of the NF-κB/Rel family members is regulated by a class of cytoplasmic inhibitory proteins termed IκBs that mask the nuclear localization domain of NF-κB causing its retention in the cytoplasm (4, 42). NF-κB can be activated by a number of stimuli including engagement of the T-cell receptor (TCR)-CD3 complexes and CD28 receptors, bacterial lipopolysaccharide, proinflammatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and interleukin-1β (IL-1β), and expression of human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 Tax transactivator protein (25, 27).

Activation of NF-κB by TNF-α and IL-1β involves a series of signaling intermediates, which may converge on the NF-κB-inducing kinase (NIK) (24). This kinase in turn activates the α and β IκB kinase (IKK) isoforms (10, 29, 31, 46, 48). These IKKs phosphorylate the two regulatory serines located in the N termini of IκB molecules (5, 6, 39, 41, 45), triggering rapid ubiquitination and degradation of IκB in the 26S proteasome complex (8, 35). The degradation of IκB unmasks a nuclear localization signal present in the NF-κB complex, allowing its rapid translocation into the nucleus, where it engages cognate κB enhancer elements and modulates the transcription of various NF-κB-responsive target genes (25).

Unlike the signaling pathways utilized by TNF-α and IL-1β, the pathway leading to activation of NF-κB induced by engagement of TCR-CD3 complexes and CD28 molecules remains less well defined. The cross-linking of TCR-CD3 complexes and CD28 molecules with antibodies specific for each receptor mimics the physiological costimulation of TCR-CD3 and CD28 induced by major histocompatibility complex molecules charged with the appropriate antigen and B7-1/B7-2 molecules present on antigen-presenting cells (APC) (7, 9, 34). This costimulatory reaction leads to the optimal production of cytokines such as IL-2. The promoter region of the IL-2 gene contains several regulatory sites, including a CD28 response element (CD28RE) (9, 15) and binding sites for several known transcription factors including NF-AT, NF-κB, Oct, and AP-1. Both NF-κB and NF-AT also bind to the CD28RE in vitro (13, 17, 23, 26, 32, 37). Stimulation via the TCR-CD3 complex alone is sufficient for activation of NF-AT (43) but is insufficient for activation of NF-κB and AP-1. The induction of NF-κB and AP-1 requires costimulation of the TCR-CD3 and CD28 receptors (17, 38). How CD3-CD28 costimulation induces NF-κB is not well defined. Recent studies have shown that costimulation of CD3 and CD28 leads to the activation of IKKs (14). Activation of the IKKs may be mediated through the activation of such upstream kinases as NIK, Cot (19), and MEK kinase 1 (MEKK1) (16). However, the signaling components connecting these kinases to CD3 and CD28 receptors on the surfaces of T cells remain to be defined.

One class of signaling components that play important roles in T cells is the family of protein kinase C (PKC) enzymes. The PKCs are serine/threonine-specific protein kinases. At present, 11 different PKC isoforms have been identified and have been grouped into three subsets based on their ability to respond to calcium (Ca2+) and/or diacylglycerols (DAG). Both the classic PKC isoforms such as α, βI, βII, and γ, and the novel PKC isoforms such as δ, ɛ, θ, and η, are activated by DAG or experimental analogs such as phorbol myristylacetate (PMA). However, the classic PKCs, not the novel PKCs, also respond to a change of intracellular calcium levels. In contrast, atypical PKC isoforms, such as ζ and λ/τ do not respond to either Ca2+ or PMA. Activation of PKC in T cells can be achieved by stimulation of cells with anti-CD3 antibodies. This stimulation in T cells leads to activation of phospholipase C-γ, which hydrolyzes inositol phospholipids into inositol polyphosphates (IP3) and DAG. The production of IP3 leads to an elevation of calcium levels through mobilization of intracellular stores. The elevated concentrations of intracellular calcium and DAG activate PKCs. Emerging evidence suggests that PKC-θ (2) may be the major isoform of PKC involved in CD3-CD28 costimulation. Recent studies (30) have shown that PKC-θ is the only isoform translocated to the site of contact between T cells and antigen-presenting cells. In addition, PKC-θ is translocated to the cytoplasmic membrane within 10 min after stimulation of the TCR-CD3 complex (40). Furthermore, ectopic expression of a constitutive active mutant of PKC-θ in cultured cells activates JNK and AP-1 transcription factors (3, 44). Conversely, ectopic expression of a kinase-deficient mutant of PKC-θ inhibits JNK activation induced by CD3-CD28 costimulation (44). Based on these observations, we hypothesized that PKC-θ might represent an important intermediate in a signaling pathway induced by CD3-CD28 costimulation leading to NF-κB activation. To test this hypothesis, we examined the ability of PKC-θ to activate the IKKs and to induce NF-κB activation in Jurkat T cells. We further analyzed whether PKC-θ participates in the CD3-CD28 costimulatory response leading to nuclear NF-κB expression and induction of the composite CD28RE-AP1 element in the IL-2 enhancer.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Expression vectors and biological reagents.

The cDNAs encoding human wild-type, constitutively active (A148E) or dominantly negative (K409R) PKC-θ were excised from the pGilda vector by digestion with BamHI and XhoI and subcloned into the BamHI and XbaI sites, respectively, of the pEF4/His-C mammalian expression vector (Invitrogen) using standard techniques. This vector encodes in-frame six-His and Xpress tags upstream of the insert. The cDNAs encoding wild-type and constitutively active (A25E) forms of PKC-α were amplified by PCR from the pEF vector (22) and subcloned into the PCR-Script vector (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.). The wild-type and A25E inserts were digested with EcoRI and XbaI. The cDNAs encoding the constitutively active mutants of rat PKC-ɛ (A159E) and mouse PKC-ζ (A119E) were cloned in the eukaryotic expression vector pEFneo. The constitutively active mutant of PKC-δ (A147E) (36) was kindly provided by Peter Parker (Imperial Cancer Research Fund, London, United Kingdom). Expression plasmids encoding the antisense PKC-θ, -ɛ, and -ζ were constructed by insertion of PCR products that contain the first 500 bp of the respective cDNAs into the pRK6 vector. Expression plasmids encoding NIK, Cot, IKKα, and IKKβ have been described elsewhere (11, 20). The κB luciferase reporter plasmid was obtained from Stratagene. The LacZ reporter (pRC-β-actin-LacZ) construct driven by the β-actin promoter was obtained from M. Karin (University of California, San Diego, Calif.). The 4×RE/AP luciferase reporter was obtained from A. Weiss (University of California, San Francisco, Calif.) and has been described elsewhere (37). Recombinant human TNF-α was purchased from Endogen (Cambridge, Mass.). Mouse anti-human CD28 monoclonal antibodies were from Caltag (Burlingame, Calif.). Mouse anti-human CD3 monoclonal antibodies (OKT3) were obtained from the University of California, San Francisco pharmacy. Jurkat E6-1 cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 5% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, penicillin, and streptomycin.

Transfections and reporter assays.

Jurkat T cells were grown to a density of approximately 0.5 × 106 to 1 × 106 cells/ml and resuspended in serum-free RPMI 1640 medium at 5 × 107 cells/ml at room temperature. Cells from this suspension (0.4 ml) were used for electroporation pulsing at 250 V and 950 μF in 0.4-cm-diameter cuvettes in a Bio-Rad Gene Pulser. Cells were then incubated at room temperature for 10 min and resuspended in 7 ml of complete RPMI 1640 medium. After 15 to 20 h, selected cultures were stimulated with TNF-α (20 ng/ml), anti-human CD3 monoclonal antibodies (OKT3) alone, anti-human CD28 monoclonal antibodies alone, or combinations of anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 antibodies. Luciferase activity was typically measured 15 to 25 h after transfection with the enhanced luciferase assay kit and a Microbeta 1450 Trilux luminescence counter (Wallac Company, Gaithersburg, Md.). All transfections included the pRC-β-actin-LacZ plasmid to normalize for differences in gene transfer efficiency.

Immune complex kinase assay.

Jurkat T cells were transfected as described above. After 24 h, the cells were resuspended in lysis buffer (1% Nonidet P-40, 250 mM NaCl, 50 mM HEPES [pH 7.4], 1 mM EDTA) supplemented with a cocktail of protease inhibitors (Boehringer Mannheim), 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 50 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), and 50 mM Na3VO4 freshly prepared before use. The lysates were then immunoprecipitated with specific antibodies coupled to protein A-conjugated agarose beads. Immunoprecipitated beads were washed three times in lysis buffer, equilibrated in kinase buffer (10 mM HEPES [pH 7.4], 1 mM MnCl2, 5 mM MgCl2, 12.5 mM β-glycero-2-phosphate, 50 mM Na3VO4, 2 mM NaF, 50 mM DTT). After suspension in 20 μl of kinase buffer, the immunoprecipitates were incubated with 5 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP (6,000 Ci/mmol)–1 μg of recombinant glutathione S-transferase (GST)–IκBα(1-62) protein as an exogenous substrate for 30 min at 30°C. The reaction was terminated by adding sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) sample buffer. The samples were analyzed by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE), transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, and exposed to Hyperfilm MP (Amersham Life Sciences, Piscataway, N.J.). The membranes were subsequently probed with antibodies to determine the levels of immunoprecipitated kinases.

IKK complex phosphorylation assays.

The ability of either NIK or PKC-θ to phosphorylate the IKKs was assessed using kinase-inactive versions of either IKKα or IKKβ as substrates. Expression vectors encoding IKKβK44A-Flag and IKKαK44M-HA were electroporated into Jurkat cells alone or in the presence of NIK or PKC-θ. After 24 h, cells were resuspended in lysis buffer. Lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-IKKγ antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, Calif.) and protein A-conjugated agarose beads, washed three times in lysis buffer, and equilibrated in kinase buffer. Reactions were carried out in ATP-free kinase buffer containing 2 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP (6,000 Ci/mmol). After 30 min, reactions were terminated by the addition of an equal volume of dissociation buffer (50 mM Tris-Cl [pH 7.4], 20 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 10% SDS), and reaction mixtures were boiled for 15 min to completely dissociate the immunoprecipitated complex. The dissociated hemagglutinin (HA)- or Flag-tagged IKK proteins and beads were then resuspended in 1 ml of lysis buffer (without SDS) and centrifuged for 2 min at maximum speed. The supernatant was collected and subjected to a second immunoprecipitation with either anti-HA or anti-Flag antibody-conjugated agarose beads. After a minimum of 4 h, the immunoprecipitates were collected, washed with lysis buffer, and resuspended in SDS-PAGE buffer and boiled for 5 min. Products were separated by SDS-PAGE, electrophoretically transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, and exposed to Hyperfilm MP (Amersham Life Sciences). The membranes were subsequently probed with either HA-specific or Flag-specific antibodies to determine the amount of IKK present.

RESULTS

PKC isoforms are involved in CD3-CD28 costimulation-induced activation of IKK.

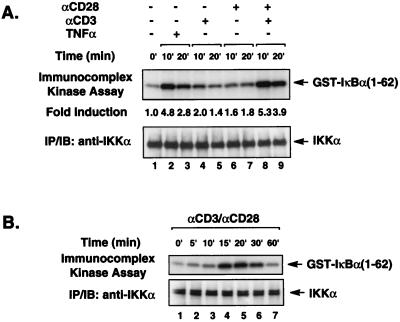

To confirm that the IKK complex is activated in response to CD3-CD28 costimulation, we first determined IKK enzymatic activity in Jurkat T cells by immunocomplex kinase assay. Endogenous IKK complexes were immunoprecipitated from Jurkat T-cell lysates using anti-IKKα antibodies following stimulation of these cells with various combinations of anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 antibodies or with TNF-α as a positive control. IKK activity was assessed based on the ability of IKK to phosphorylate exogenously added purified GST–IκBα(1-62). Consistent with a previous report (14), stimulation with either anti-CD3 or anti-CD28 antibodies alone only slightly induced IKK activity. However, costimulation with a combination of these antibodies significantly activated endogenous IKK enzymatic activity (Fig. 1A, lanes 8 and 9). The induction of IKK activity by these costimulatory signals peaked between 15 and 30 min and declined by 60 min (Fig. 1B).

FIG. 1.

CD3-CD28 transiently activates endogenous IKK signalsome complexes. (A) Jurkat T cells (∼2 × 106) were stimulated with antibodies specific for CD3 (2 μg/ml) or CD28 (2 μg/ml) alone or in combination as indicated. Endogenous IKK complexes were immunoprecipitated (IP) using anti-IKKα antibodies, and then in vitro kinase reactions were performed with the immunoprecipitates using GST–IκBα(1-62) as an exogenously added substrate. The kinase reaction products were analyzed by SDS-PAGE, transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, and subjected to autoradiography. The level of IKKα present in each immunoprecipitate is shown in the lower blot. (B) IKK enzymatic activity was assessed as described for panel A over a longer time course. IB, immunoblot.

To test the potential involvement of PKC in this costimulatory signaling pathway, we assessed IKK activation following CD3-CD28 costimulation in the presence and the absence of bisindolylmaleimide, a relatively specific PKC inhibitor. We found that bisindolylmaleimide significantly, although not completely, inhibited IKK activation induced by CD3-CD28 costimulation (Fig. 2, lanes 8 to 10). In contrast, this PKC inhibitor failed to inhibit IKK activation induced by TNF-α (Fig. 2). Together, these data suggest that one or more PKC isoforms participate in the CD3-CD28 costimulatory response leading to IKK activation.

FIG. 2.

A PKC inhibitor blocks IKK activation induced by CD3-CD28 costimulation. Jurkat T cells (∼2 × 106) were incubated in medium with or without bisindolylmaleimide (12 μM) for 30 min and then stimulated with a combination of antibodies specific for CD3 (2 μg/ml) and CD28 (2 μg/ml) or TNF-α (10 ng/ml). The enzymatic activity of the endogenous IKK complexes was assessed using phosphorylated GST–IκBα(1-62) as described for Fig. 1. The kinase reactions are shown in the upper panel. The lower panel shows the level of immunoprecipitated endogenous IKKα in each kinase reaction mixture.

PKC-θ participates in NF-κB activation induced by CD3-CD28 costimulation.

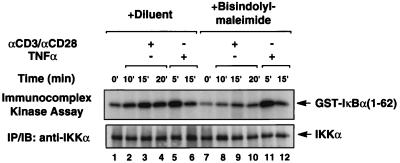

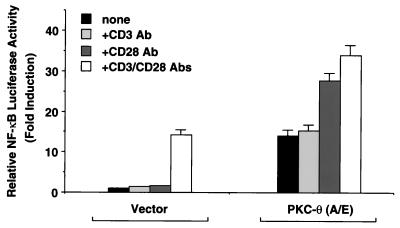

Previous studies suggested that PKC-θ may be involved in CD3-CD28 costimulatory signaling (30, 44). Accordingly, we tested whether this PKC isoform played a role in CD3-CD28-induced NF-κB activation. We first examined the effects of ectopic expression of a constitutively active form (A/E) of PKC-θ containing a glutamine-for-alanine substitution at residue 148. Similarly, constitutively active mutants of PKC-α, -ɛ, -δ, and -ζ were tested in parallel, as well as a kinase-deficient mutant (K/R) of PKC-θ. Jurkat T cells were cotransfected with an NF-κB-dependent luciferase reporter together with plasmids encoding the constitutively active PKC-θ, -α, -ɛ, -δ, and -ζ mutants, and luciferase activity was assayed 20 h later. We found that expression of PKC-θ (A/E) potently induced NF-κB activation, while the kinase-deficient K/R mutant of PKC-θ failed to do so (Fig. 3A). Expression of PKC-ɛ (A/E) slightly induced NF-κB activation; however, expression of PKC-α (A/E), PKC-δ (A/E), and PKC-ζ (A/E) did not induce NF-κB activation in these Jurkat T cells (Fig. 3A).

FIG. 3.

PKC-θ plays a role in NF-κB induction following CD3-CD28 costimulation. (A) Jurkat T cells (∼2 × 107) were transfected with 5 or 10 μg of plasmids encoding either a constitutively active form (A/E) of PKC-θ, -α, -ɛ, -δ, and -ζ or a kinase-deficient form (K/R) of PKC-θ together with 10 μg of 5× κB luciferase and 5 μg of β-actin–β-galactosidase reporter plasmids. Cell lysates were prepared from the cultures 20 h after transfection, and luciferase activities were determined. (B to D) Jurkat T cells were transfected with 10 μg of 5× κB luciferase and 5 μg of β-actin–β-galactosidase reporter plasmids together with 0, 5, 10, 20, or 40 μg of PKC-θ (K/R) (B) or antisense expression vectors of PKC-θ, -ɛ, or -ζ (C and D). The total DNA concentration was held constant by supplementation with the parental vector DNA. Twenty hours after the transfection, the cells were stimulated with a combination of antibodies specific for CD3 (2 μg/ml) and CD28 (2 μg/ml) or TNF-α (10 ng/ml) for 5 h. Cell lysates were prepared from the cultures, and luciferase activities were determined. The β-galactosidase activities in these lysates were determined and used to normalize for differences in transfection efficiency. The standard deviations were derived from independent transfections performed in triplicate.

We next examined whether expression of PKC-θ (K/R) inhibits NF-κB activation induced by CD3-CD28 costimulation. We observed that expression of PKC-θ (K/R) inhibited NF-κB activation induced by CD3-CD28 costimulation in a dose-dependent manner. In contrast, this mutant did not significantly inhibit NF-κB activation induced by TNF-α (Fig. 3B). In addition, expression of antisense PKC-θ specifically inhibited NF-κB activation induced by CD3-CD28 costimulation (Fig. 3C) but not by TNF-α (Fig. 3D). In contrast, expression of antisense PKC-ɛ or PKC-ζ did not inhibit NF-κB activation induced by CD3-CD28 costimulation (Fig. 3C). Together, these data suggest that PKC-θ plays a role in a signaling pathway induced by CD3-CD28 costimulation leading to NF-κB activation. Of note, the expression of PKC-θ (K/R) only inhibited about 60% of the maximal NF-κB activation induced by CD3-CD28 costimulation (Fig. 3B), raising the possibility that a PKC-θ-independent pathway induced by CD3-CD28 costimulation may also exist.

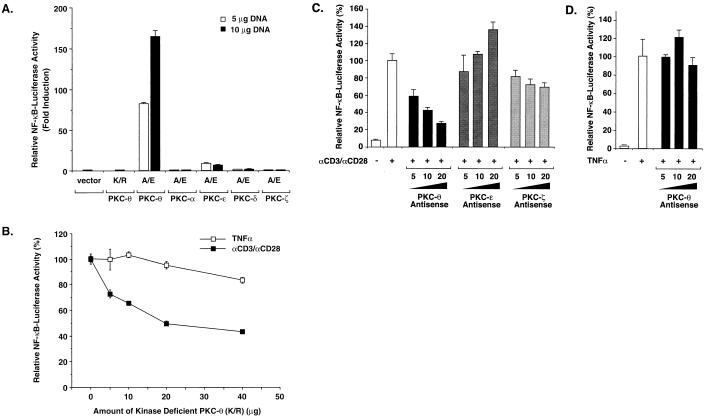

PKC-θ activates the CD28 response element of the IL-2 promoter.

Since previous studies demonstrated that CD3-CD28 costimulatory signals are integrated via CD28RE and the flanking AP-1 site in the IL-2 promoter (37), we next assessed whether ectopic expression of PKC-θ could activate the CD28RE. Plasmids encoding the constitutively active mutants (A/E) of PKC-θ, -α, -ɛ, -δ, and -ζ were transfected into Jurkat T cells together with the RE/AP luciferase reporter plasmid, in which a luciferase gene is placed under the control of a composite enhancer element (RE/AP) containing the CD28RE and the downstream AP-1 site of the IL-2 promoter (37). Expression of PKC-θ (A/E), but not the corresponding constitutively active mutants of PKC-α, -ɛ, -δ, and -ζ, potently stimulated RE/AP-dependent transcription (Fig. 4). This activation of RE/AP proved dependent on the kinase activity of PKC-θ, since the kinase-deficient mutant (K/R) failed to activate the RE/AP element (Fig. 4). Together, these results further support a role for PKC-θ in a signaling pathway induced by CD3-CD28 costimulation.

FIG. 4.

PKC-θ activates the CD28 response element of the IL-2 promoter. Jurkat T cells (∼2 × 107) were transfected with 5 μg of plasmids encoding a constitutively active form (A/E) or a kinase-deficient form (K/R) of PKC-θ, -α, -ɛ, -δ, and -ζ together with 10 μg of a luciferase reporter plasmid containing a composite enhancer motif from the human IL-2 gene corresponding to the CD28RE and AP-1 sites (RE/AP-Luciferase) and 5 μg of β-actin–β-galactosidase reporter plasmids. Cell lysates were prepared 20 h after transfection and assayed for luciferase activity. The β-galactosidase activities in these lysates were determined and used to normalize for differences between transfection efficiencies in the various cultures. The standard deviations were derived from independent triplicate transfections.

CD28 stimulation enhances PKC-θ-induced NF-κB activation.

Since stimulation of T cells by TCR-CD3 complexes alone leads to translocation of PKC-θ to the plasma membrane (40), we hypothesized that ectopic expression of a constitutively active mutant of PKC-θ might substitute for CD3 stimulation in Jurkat T cells. To test this hypothesis, we examined NF-κB activation with or without the expression of PKC-θ (A/E) in Jurkat T cells following stimulation with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 antibodies, either alone or in combination. While the addition of anti-CD3 antibodies had no effect on PKC-θ-induced NF-κB activation, stimulation of cells with anti-CD28 antibodies or a combination of anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 antibodies significantly enhanced PKC-θ-induced NF-κB activation (Fig. 5). These data suggest that expression of PKC-θ (A/E) can partially mimic CD3 signals leading to the induction of NF-κB and also suggest that CD28 stimulation induces an undefined signaling event that can enhance the function of PKC-θ (A/E) in Jurkat T cells.

FIG. 5.

CD28 stimulation enhances PKC-θ-induced NF-κB activation. Jurkat T cells (∼2 × 107) were transfected with 2.5 μg of plasmids encoding a constitutively active form (A/E) of PKC-θ together with 10 μg of 5 × κB luciferase and 5 μg of β-actin–β-galactosidase reporter plasmids or with the luciferase and reporter plasmids alone. About 15 h after the transfection, the cells were stimulated for 5 h with antibodies specific for CD3 (2 μg/ml) and CD28 (2 μg/ml), either alone or in combination as indicated. Cell lysates were then prepared from the cultures, and luciferase activities were determined. The β-galactosidase activities in these lysates were assayed and used to normalize for differences in transfection efficiency. The standard deviations were derived from independent transfections performed in triplicate.

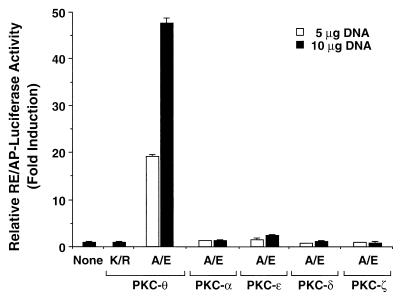

PKC-θ activates IKKβ but not IKKα.

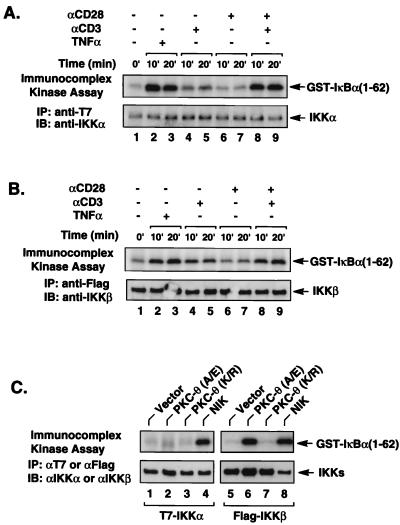

Since CD3-CD28 costimulation effectively activates endogenous IKK complexes (Fig. 1A) and since previous studies suggest that endogenous IKKα and IKKβ form heterodimeric complexes, we next determined whether CD3-CD28 costimulation could activate both IKKα and IKKβ. To selectively assess the activity of IKKα and IKKβ, plasmids encoding epitope-tagged IKKα or IKKβ were individually transfected into Jurkat T cells. The transfected cells were then stimulated with various combinations of anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 antibodies. IKKα and IKKβ kinase activity was determined by immunoprecipitation followed by an in vitro kinase assay using GST–IκBα(1-62) as a substrate. Similar to what was found for endogenous IKK complexes, CD3-CD28 costimulation induced the enzymatic activity of both transfected IKKα (Fig. 6A) and transfected IKKβ (Fig. 6B), indicating that CD3-CD28 costimulation leads to activation of both IKKα and IKKβ.

FIG. 6.

PKC-θ activates IKKβ but not IKKα. Jurkat T cells (∼2 × 107) were transfected with 5 μg of IKKα-T7 (A) or 2 μg of IKKβ-Flag (B). Twenty hours after transfection, the cultures were stimulated with antibodies specific for CD3 (2 μg/ml) and CD28 (2 μg/ml), either alone or in combination as indicated. The transfected IKKα-T7 and IKKβ-Flag were then immunoprecipitated (IP) with anti-T7 and anti-Flag antibody-coupled agarose, respectively. The immunoprecipitates were then subjected to an in vitro kinase reaction using GST–IκBα(1-62) as an exogenously added substrate. The kinase reaction products were then analyzed by SDS-PAGE and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, and the resultant autoradiographs are shown in the upper portion of each panel. The phosphorylated GST–IκBα(1-62) is indicated on the right. The lower portion of each panel shows the levels of immunoprecipitated IKKα-T7 or IKKβ-Flag present in each kinase reaction mixture. (C) Jurkat T cells (∼2 × 107) were transfected with 5 μg of IKKα-T7 or 2 μg of IKKβ-Flag plasmids in the presence or absence of plasmids encoding PKC-θ (A/E), PKC-θ (K/R), or NIK. Twenty hours after transfection, the transfected IKKα-T7 and IKKβ-Flag proteins were immunoprecipitated using anti-T7 and anti-Flag antibody-conjugated agarose, respectively, and then subjected to an in vitro kinase reaction as described for panels A and B. The resultant autoradiographs are shown in the upper portion of the panel. The phosphorylated GST–IκB(1-62) is indicated on the right. The lower portion of the panel shows the level of immunoprecipitated IKKα-T7 or IKKβ-Flag present in each kinase reaction mixture. IB, immunoblot.

We next determined whether PKC-θ similarly induces NF-κB activation through stimulation of both IKKα and IKKβ. Plasmids encoding the constitutively active or inactive mutants of PKC-θ together with epitope-tagged IKKα or IKKβ constructs were cotransfected into Jurkat T cells. The kinase activity of IKKα and IKKβ was similarly determined by an immunocomplex kinase assay using GST–IκBα(1-62) as a substrate. We found that expression of the constitutively active PKC-θ (A/E) mutant, but not the kinase-deficient PKC-θ (K/R) mutant, potently induced IKKβ. In contrast, PKC-θ (A/E) did not induce IKKα activity (Fig. 6C). However, IKKα was effectively induced in the presence of NIK (Fig. 6C, lane 4). Together, these data indicate that PKC-θ activates NF-κB through the selective induction of IKKβ enzymatic activity.

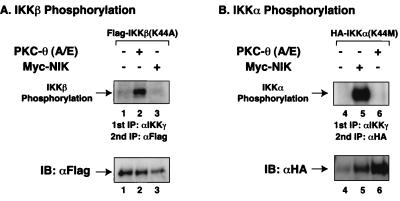

PKC-θ induces phosphorylation of IKKβ but not IKKα.

To elucidate the molecular mechanism underlying PKC-θ induction of IKKβ activity, we examined the ability of PKC-θ to phosphorylate IKKβ. In this experiment, kinase-deficient mutants of IKKα and IKKβ were assessed as potential substrates for PKC-θ in comparison to NIK, which had previously been shown to phosphorylate IKKα (21). Plasmids encoding the epitope-tagged kinase-deficient mutant (K44A) of IKKβ were cotransfected together with PKC-θ (A/E) or NIK into Jurkat T cells. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-IKKγ antibodies to isolate signalsome-coupled IKKβ(K44A), exploiting the finding that IKKγ is an essential subunit of functional IKK signalsome complexes (28, 33, 47). Immunoprecipitates were then subjected to an in vitro kinase assay. To eliminate endogenous IKKα that may have associated with transfected IKKβ(K44A) and to ensure that only IKKβ phosphorylation status was evaluated, IKKβ(K44A) was reisolated by a second immunoprecipitation following heat dissociation in an SDS buffer. In this assay system, we found that expression of PKC-θ (A/E) effectively induced IKKβ phosphorylation (Fig. 7A). In contrast, expression of NIK did not produce IKKβ phosphorylation (Fig. 7A). However, NIK, not PKC-θ (A/E), induced IKKα phosphorylation (Fig. 7B) in a similar experiment using IKKα(K44M) as the substrate. Together, these data indicate that PKC-θ activates IKKβ through selective phosphorylation of IKKβ. It remains unknown whether this reaction involves a direct or indirect mechanism.

FIG. 7.

PKC-θ selectively induced IKKβ phosphorylation but not IKKα phosphorylation. Jurkat T cells (∼2 × 107) were transfected with kinase-deficient mutants of IKKα(K44M)-HA or IKKβ(K44A)-Flag in the presence or absence of a constitutively active form (A/E) of PKC-θ or NIK. After 20 h, cell lysates were prepared from the cultures. Physiological signalsome complexes containing these IKKs were immunoprecipitated (IP) using anti-IKKγ antibodies. The immunoprecipitates were subjected to an in vitro kinase assay. The IKK complexes in the kinase reaction mixtures were then dissociated in a buffer containing a high concentration of SDS (10%) by boiling for 15 min. IKKα(K44M)-HA and IKKβ(K44A)-Flag in the heat-dissociated samples were then reimmunoprecipitated after dilution of the SDS using anti-HA and anti-Flag antibody-conjugated agarose, respectively. The immunoprecipitates were then analyzed by SDS-PAGE and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, and the autoradiographs are shown in the upper portions of the panels. The lower portions show the level of immunoprecipitated IKKα(K44M)-HA or IKKβ(K44A)-Flag proteins present in each kinase reaction mixture. IB, immunoblot.

PKC-θ functions upstream or in a parallel pathway to Cot and NIK.

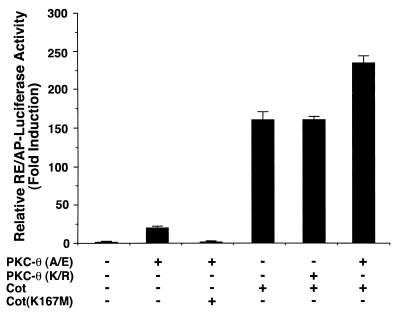

Our previous studies suggested that mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinases Cot and NIK participate in the CD3-CD28 signaling pathway leading to activation of IKKα and IKKβ (19). To determine whether PKC-θ functions upstream of Cot and NIK, we cotransfected plasmids encoding PKC-θ and Cot together with the RE/AP luciferase reporter into Jurkat T cells. Expression of kinase-deficient mutants of either Cot or Cot(K167M) (Fig. 8) or NIK(KK429/430AA) (data not shown) inhibited PKC-θ (A/E)-induced RE/AP activation. In contrast, expression of PKC-θ (K/R) had no effect on Cot-induced RE/AP activation and expression of PKC-θ (A/E) enhanced Cot-induced RE/AP activation (Fig. 8). Together, these results suggest that PKC-θ functions upstream or in a parallel pathway to Cot and NIK, perhaps utilizing a common downstream component (Fig. 9) following CD3-CD28 costimulation.

FIG. 8.

PKC-θ functions upstream or in a parallel pathway to Cot. Jurkat T cells (∼2 × 107) were transfected with 5 μg of plasmids encoding a constitutively active form (A/E) of PKC-θ or Cot with 10 μg of a luciferase reporter plasmid containing a composite enhancer motif from the human IL-2 gene corresponding to the CD28RE and AP-1 sites (RE/AP-Luciferase) and 5 μg of β-actin–β-galactosidase reporter plasmids. In some samples, 10 μg of plasmids encoding the kinase-deficient form (K/R) of PKC-θ or the kinase-deficient form (K167M) of Cot was added. Cell lysates were prepared 20 h after transfection and assayed for luciferase activity. The β-galactosidase activities in these lysates were determined and used to normalize for differences in transfection efficiency in the various cultures. The standard deviations were derived from independent triplicate transfections.

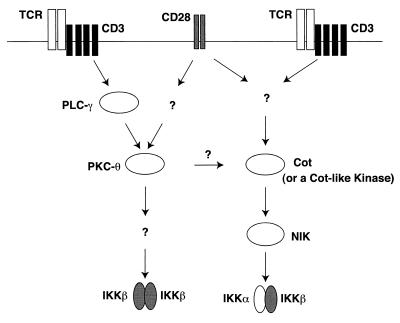

FIG. 9.

A working model for IKK activation induced by CD3-CD28 costimulation. CD3-CD28 costimulation induces at least two parallel pathways leading to activation of NF-κB. One pathway involves the activation of signalsomes containing IKKα-IKKβ heterodimers through NIK and Cot (or a Cot-like kinase). The other pathway leads to activation of IKKβ-IKKβ homodimers through the induction of PKC-θ. PLC-γ, phospholipase C-γ.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we demonstrate that PKC-θ is a major PKC isoform involved in NF-κB activation induced by CD3-CD28 costimulation in Jurkat T cells. The evidence supporting this conclusion includes the finding that expression of a constitutively active mutant (A/E) of PKC-θ potently activates NF-κB in Jurkat T cells, whereas expression of similar constitutively active mutants of other PKC isoforms, including the α, ɛ, δ, and ζ isoforms, either fails to activate or only slightly activates NF-κB (Fig. 3). Furthermore, ectopic expression of a kinase-deficient mutant (K/R) of PKC-θ selectively inhibits NF-κB activation induced by CD3-CD28 costimulation but not by TNF-α. Additionally, expression of a constitutively active mutant of PKC-θ, but not similar mutants of PKC-α, -ɛ, -δ, and -ζ, leads to a potent induction of the luciferase reporter gene controlled by a composite enhancer element containing the CD28 response element and the flanking AP-1 site (RE/AP) from the IL-2 promoter (Fig. 4). Thus, ectopic expression of PKC-θ (A/E) in Jurkat T cells mimics many of the effects of CD3-CD28 costimulation. Taken together, these results suggest that PKC-θ is a major PKC isoform involved in NF-κB activation induced by CD3-CD28 costimulation.

In this study, we demonstrate that PKC-θ selectively stimulates IKKβ, but not IKKα, enzymatic activity, leading to the induction of NF-κB. (Fig. 6). Moreover, this active mutant of PKC-θ is capable of inducing phosphorylation of IKKβ but fails to induce phosphorylation of IKKα (Fig. 7). In contrast, NIK expression induces phosphorylation of IKKα but not IKKβ (Fig. 7). Since CD3-CD28 costimulation can activate both IKKα and IKKβ (Fig. 6A and B), our results showing that PKC-θ only activates IKKβ while NIK activates IKKα raise the possibility that multiple pathways are activated by CD3-CD28 costimulation leading to induction of NF-κB. Together with our previous findings showing that NIK and Cot are involved in the CD3-CD28 costimulatory pathway (19), these data suggest that CD3-CD28 costimulation likely induces at least two parallel pathways leading to activation of IKKα and IKKβ (Fig. 9). One pathway leads to activation of IKKα through activation of Cot (or a Cot-like kinase) and likely NIK (19). This activated IKKα could then activate IKKβ. In contrast, the second pathway leads directly to induction of IKKβ enzymatic activity through activation of PKC-θ. Consistent with this hypothesis, expression of PKC-θ (A/E) enhances Cot-induced RE/AP activation, whereas expression of PKC-θ (K/R) has no effect on Cot-induced RE/AP activation (Fig. 8). Inhibition of PKC-θ-induced RE/AP activation by Cot(K167M) suggests that Cot may be a homologue of a downstream component utilized by PKC-θ or may compete for a downstream component in the PKC-θ pathway. We are currently searching for additional components of the PKC-θ pathway that may be targeted by kinase-deficient forms of Cot and NIK.

Previous studies have shown that endogenous IKKα and IKKβ preferentially form heterodimeric complexes. However, ectopically expressed IKKα and IKKβ are capable of forming both homodimers and heterodimers in transfected cells (46). The existence of IKKβ homodimers in HeLa cells has recently been reported (28). While the physiological role of these homodimeric and heterodimeric IKK complexes remains to be defined, it is possible that these different IKK dimers may couple in a distinct manner to upstream signaling components in response to different stimuli. In this study, we showed that PKC-θ selectively phosphorylates IKKβ, suggesting that it may preferentially function through IKKβ homodimers. Specifically, we find that PKC-θ induces IKKβ phosphorylation when IKKβ is ectopically expressed (Fig. 7A), a condition which leads to the formation of IKKβ homodimers. In further support of this possibility, we find that expression of IKKβ together with either wild-type or kinase-deficient mutants of IKKα, a condition which likely leads to the formation of IKKα and IKKβ heterodimers, inhibits PKC-θ-induced IKKβ phosphorylation (data not shown). Thus, PKC-θ may be a signaling intermediate that selectively targets IKKβ homodimers.

Although we find that PKC-θ selectively activates IKKβ, the underlying mechanism is yet to be defined. One possible mechanism is that PKC-θ may directly phosphorylate IKKβ, as suggested by a recent observation that an atypical isoform of PKC, PKC-ζ, directly phosphorylates IKKβ in vitro and physically associates with IKKβ in 293 cells (18). However, thus far we have been unable to detect a physical association between PKC-θ and the IKK complexes. An alternative explanation is that PKC-θ may indirectly activate IKKβ through one or more intermediate components. One such signaling intermediate might be MEKK1, which also has been implicated as an intermediate in CD3-CD28 costimulation leading to NF-κB activation through selective activation of IKKβ (16). Of note, the results in this study (Fig. 3) and others (12) showing that expression of a constitutively active mutant of PKC-ζ is not sufficient for activation of NF-κB in T cells differ from the observation that expression of a constitutively active mutant of PKC-ζ in other cell types activates NF-κB. This apparent discrepancy could indicate that the function of PKC-ζ in T cells may be different from that in other cells.

Previous observations revealed that PKC-θ is the principal PKC isoform responding to stimulation by APC (30) or anti-TCR-CD3 antibodies, since it rapidly translocates to the plasma membranes of T cells (40). Although it is clear that stimulation of T cells with anti-TCR-CD3 antibodies is sufficient to induce membrane localization of PKC-θ, the functional significance of costimulation by CD28 is unclear. In this study, we find that expression of a constitutively active mutant of PKC-θ is sufficient to activate NF-κB. However, CD28 stimulation significantly enhances NF-κB activation induced by PKC-θ (Fig. 5). These results suggest that CD28 costimulation may create an optimal microenvironment for activation of PKC-θ, or alternatively may relocate the downstream signaling components in greater proximity to PKC-θ. These hypotheses will be tested in our future studies.

In summary, we demonstrate that PKC-θ is the major isoform of PKC that is involved in NF-κB activation induced by CD3-CD28 costimulation. CD3-CD28 costimulation appears to induce at least two parallel signaling pathways leading to the activation of NF-κB (Fig. 9). One pathway results in the induction of both IKKα and IKKβ enzymatic activity and appears to involve upstream signaling by two MAP3Ks, namely NIK and Cot (or a Cot-like kinase) (19). Our present study suggests a second pathway involving PKC-θ, which likely activates signalsomes containing IKKβ homodimers and leads to NF-κB activation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Amnon Altman and Peter Parker for PKC expression plasmids.

This work was supported by grants from the UCSF Center for AIDS Research (MH 59037) and from Pfizer.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baeuerle P A, Baltimore D. NF-κB: ten years after. Cell. 1996;87:13–20. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81318-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baier G, Telford D, Giampa L, Coggeshall K M, Baier-Bitterlich G, Isakov N, Altman A. Molecular cloning and characterization of PKC-θ, a novel member of the protein kinase C (PKC) gene family expressed predominantly in hematopoietic cells. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:4997–5004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baier-Bitterlich G, Überall F, Bauer B, Fresser F, Wachter H, Grunicke H, Utermann G, Altman A, Baier G. Protein kinase C-θ isoenzyme selective stimulation of the transcription factor complex AP-1 in T lymphocytes. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:1842–1850. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.4.1842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baldwin A J. The NF-κB and IκB proteins: new discoveries and insights. Annu Rev Immunol. 1996;14:649–683. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.14.1.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brockman J A, Scherer D C, McKinsey T A, Hall S M, Qi X, Lee W Y, Ballard D W. Coupling of a signal response domain in IκBα to multiple pathways for NF-κB activation. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:2809–2818. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.5.2809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown K, Gerstberger S, Carlson L, Franzoso G, Siebenlist U. Control of IκBα proteolysis by site-specific, signal-induced phosphorylation. Science. 1995;267:1485–1488. doi: 10.1126/science.7878466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chambers C A, Allison J P. Co-stimulation in T cell responses. Curr Opin Immunol. 1997;9:396–404. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(97)80087-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen Z, Hagler J, Palombella V J, Melandri F, Scherer D, Ballard D, Maniatis T. Signal-induced site-specific phosphorylation targets IκBα to the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Genes Dev. 1995;9:1586–1597. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.13.1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crabtree G R, Clipstone N A. Signal transmission between the plasma membrane and nucleus of T lymphocytes. Annu Rev Biochem. 1994;63:1045–1083. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.63.070194.005145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DiDonato J A, Hayakawa M, Rothwarf D M, Zandi E, Karin M. A cytokine-responsive IκB kinase that activates the transcription factor NF-κB. Nature. 1997;388:548–554. doi: 10.1038/41493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Geleziunas R, Ferrell S, Lin X, Mu Y, Cunningham E J, Grant M, Connelly M A, Hambor J E, Marcu K B, Greene W C. Human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 Tax induction of NF-κB involves activation of the IκB kinase α (IKKα) and IKKβ cellular kinases. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:5157–5165. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.9.5157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Genot E M, Parker P J, Cantrell D A. Analysis of the role of protein kinase C-α, -ɛ, and -ζ in T cell activation. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:9833–9839. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.17.9833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ghosh P, Tan T H, Rice N R, Sica A, Young H A. The interleukin 2 CD28-responsive complex contains at least three members of the NF kappa B family: c-Rel, p50, and p65. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:1696–1700. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.5.1696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harhaj E W, Sun S C. IκB kinases serve as a target of CD28 signaling. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:25185–25190. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.39.25185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jain J, Loh C, Rao A. Transcriptional regulation of the IL-2 gene. Curr Opin Immunol. 1995;7:333–342. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(95)80107-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kempiak S J, Hiura T S, Nel A E. The Jun kinase cascade is responsible for activating the CD28 response element of the IL-2 promoter: proof of cross-talk with the IκB kinase cascade. J Immunol. 1999;162:3176–3187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lai J H, Horvath G, Subleski J, Bruder J, Ghosh P, Tan T H. RelA is a potent transcriptional activator of the CD28 response element within the interleukin 2 promoter. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:4260–4271. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.8.4260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lallena M J, Diaz-Meco M T, Bren G, Payá C V, Moscat J. Activation of IκB kinase β by protein kinase C isoforms. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:2180–2188. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.3.2180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin X, Cunningham E T, Jr, Mu Y, Geleziunas R, Greene W C. The proto-oncogene Cot kinase participates in CD3/CD28 induction of NF-κB acting through the NF-κB-inducing kinase and IκB kinases. Immunity. 1999;10:271–280. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80027-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin X, Mu Y, Cunningham E T, Jr, Marcu K B, Geleziunas R, Greene W C. Molecular determinants of NF-κB-inducing kinase action. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:5899–5907. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.10.5899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ling L, Cao Z, Goeddel D V. NF-κB-inducing kinase activates IKK-α by phosphorylation of Ser-176. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:3792–3797. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.3792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu Y, Liu Y C, Meller N, Giampa L, Elly C, Doyle M, Altman A. Protein kinase C activation inhibits tyrosine phosphorylation of Cbl and its recruitment of Src homology 2 domain-containing proteins. J Immunol. 1999;162:7095–7101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maggirwar S B, Harhaj E W, Sun S C. Regulation of the interleukin-2 CD28-responsive element by NF-ATp and various NF-κB/Rel transcription factors. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:2605–2614. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.5.2605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Malinin N L, Boldin M P, Kovalenko A V, Wallach D. MAP3K-related kinase involved in NF-κB induction by TNF, CD95 and IL-1. Nature. 1997;385:540–544. doi: 10.1038/385540a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.May M J, Ghosh S. Signal transduction through NF-κB. Immunol Today. 1998;19:80–88. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(97)01197-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McGuire K L, Iacobelli M. Involvement of Rel, Fos, and Jun proteins in binding activity to the IL-2 promoter CD28 response element/AP-1 sequence in human T cells. J Immunol. 1997;159:1319–1327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mercurio F, Manning A M. Multiple signals converging on NF-κB. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1999;11:226–232. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(99)80030-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mercurio F, Murray B W, Shevchenko A, Bennett B L, Young D B, Li J W, Pascual G, Motiwala A, Zhu H, Mann M, Manning A M. IκB kinase (IKK)-associated protein 1, a common component of the heterogeneous IKK complex. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:1526–1538. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.2.1526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mercurio F, Zhu H, Murray B W, Shevchenko A, Bennett B L, Li J, Young D B, Barbosa M, Mann M, Manning A, Rao A. IKK-1 and IKK-2: cytokine-activated IκB kinases essential for NF-κB activation. Science. 1997;278:860–866. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5339.860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Monks C R, Kupfer H, Tamir I, Barlow A, Kupfer A. Selective modulation of protein kinase C-θ during T-cell activation. Nature. 1997;385:83–86. doi: 10.1038/385083a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Regnier C H, Song H Y, Gao X, Goeddel D V, Cao Z, Rothe M. Identification and characterization of an IκB kinase. Cell. 1997;90:373–383. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80344-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rooney J W, Sun Y L, Glimcher L H, Hoey T. Novel NFAT sites that mediate activation of the interleukin-2 promoter in response to T-cell receptor stimulation. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:6299–6310. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.11.6299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rothwarf D M, Zandi E, Natoli G, Karin M. IKK-γ is an essential regulatory subunit of the IκB kinase complex. Nature. 1998;395:297–300. doi: 10.1038/26261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rudd C E. Upstream-downstream: CD28 cosignaling pathways and T cell function. Immunity. 1996;4:527–534. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80479-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Scherer D C, Brockman J A, Chen Z, Maniatis T, Ballard D W. Signal-induced degradation of IκB α requires site-specific ubiquitination. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:11259–11263. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.24.11259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schönwasser D C, Marais R M, Marshall C J, Parker P J. Activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase pathway by conventional, novel, and atypical protein kinase C isotypes. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:790–798. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.2.790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shapiro V S, Truitt K E, Imboden J B, Weiss A. CD28 mediates transcriptional upregulation of the interleukin-2 (IL-2) promoter through a composite element containing the CD28RE and NF-IL-2B AP-1 sites. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:4051–4058. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.7.4051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Su B, Jacinto E, Hibi M, Kallunki T, Karin M, Ben N Y. JNK is involved in signal integration during costimulation of T lymphocytes. Cell. 1994;77:727–736. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90056-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sun S, Elwood J, Greene W C. Both amino- and carboxyl-terminal sequences within IκBα regulate its inducible degradation. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:1058–1065. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.3.1058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Szamel M, Appel A, Schwinzer R, Resch K. Different protein kinase C isoenzymes regulate IL-2 receptor expression or IL-2 synthesis in human lymphocytes stimulated via the TCR. J Immunol. 1998;160:2207–2214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Traenckner E B, Pahl H L, Henkel T, Schmidt K N, Wilk S, Baeuerle P A. Phosphorylation of human IκBα on serines 32 and 36 controls IκBα proteolysis and NF-κB activation in response to diverse stimuli. EMBO J. 1995;14:2876–2883. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07287.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Verma I M, Stevenson J K, Schwarz E M, Van A D, Miyamoto S. Rel/NF-κB/IκB family: intimate tales of association and dissociation. Genes Dev. 1995;9:2723–2735. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.22.2723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Weiss A, Littman D R. Signal transduction by lymphocyte antigen receptors. Cell. 1994;76:263–274. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90334-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Werlen G, Jacinto E, Xia Y, Karin M. Calcineurin preferentially synergizes with PKC-θ to activate JNK and IL-2 promoter in T lymphocytes. EMBO J. 1998;17:3101–3111. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.11.3101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Whiteside S T, Ernst M K, LeBail O, Laurent W C, Rice N, Israel A. N- and C-terminal sequences control degradation of MAD3/IκB in response to inducers of NF-κB activity. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:5339–5345. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.10.5339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Woronicz J D, Gao X, Cao Z, Rothe M, Goeddel D V. IκB kinase-β: NF-κB activation and complex formation with IκB kinase-α and NIK. Science. 1997;278:866–869. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5339.866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yamaoka S, Courtois G, Bessia C, Whiteside S T, Weil R, Agou F, Kirk H E, Kay R J, Israël A. Complementation cloning of NEMO, a component of the IκB kinase complex essential for NF-κB activation. Cell. 1998;93:1231–1240. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81466-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zandi E, Rothwarf D M, Delhase M, Hayakawa M, Karin M. The IκB kinase complex (IKK) contains two kinase subunits, IKKα and IKKβ, necessary for IκB phosphorylation and NF-κB activation. Cell. 1997;91:243–252. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80406-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]