Abstract

Objective:

Many people prefer to learn secondary or “additional” findings from genomic sequencing, including findings with limited medical actionability. Research has investigated preferences for and effects of learning such findings, but not psychosocial and behavioral effects of receiving education about them and the option to request them, which could be burdensome or beneficial (e.g., causing choice overload or satisfying strong preferences, respectively).

Methods:

335 adults with suspected genetic disorders who had diagnostic exome sequencing in a research study and were randomized to receive either diagnostic findings only (DF; n=171) or diagnostic findings plus education about additional genomic findings and the option to request them (DF+EAF; n=164). Assessments occurred after enrollment (Time 1), after return of diagnostic results and—for DF+EAF—the education under investigation (Time 2), and three and six months later (Times 3, 4).

Results:

Time 2 test-related distress, test-related uncertainty, and generalized anxiety were lower in the DF+EAF group (ps=0.025–0.043). There were no other differences.

Conclusions:

Findings show limited benefits and no harms of providing education about and the option to learn additional findings with limited medical actionability.

Practice Implications:

Findings can inform recommendations for returning additional findings from genomic sequencing (e.g., to research participants or after commercial testing).

Keywords: Genomic sequencing, diagnostic sequencing, additional genomic findings, randomized controlled trial, test-related distress

1. Introduction

Genomic sequencing methods capable of examining changes in many genes at once (high-throughput methods) are an increasingly useful and cost-effective tool for clinical care and research. For instance, diagnostic sequencing can shorten patients’ diagnostic odyssey while informing clinical decision making[1, 2]. Growing use of these methods has spurred research on how to manage genomic findings unrelated to the primary indication for sequencing. These “secondary findings” offer information about genetic risks or conditions that may be relevant to health[3]). Recommendations from the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) focus on return of secondary findings related to conditions caused by changes in a single gene (monogenic disorders) with strong evidence of clinical utility (i.e., medically actionable findings related to health conditions with known medical treatments or prevention options)[4, 5]. We differentiate between findings like those covered by ACMG recommendations (hereafter called medically actionable secondary findings) and findings with less or no medical actionability that may found using sequencing methods such as genome, exome, or panel tests. The present study applies to the latter category, which we call “additional genomic findings.”

Although research has investigated people’s preferences for learning different types of genomic findings[6–9] and their responses to receiving primary, medically-actionable secondary, and additional genomic findings[10–13], we know of no research investigating a more general question regarding potential harms or benefits of providing people with education about a broad range of additional genomic findings and offering them the option to request them. This is a notable gap because of the prevailing assumption and some evidence that people strongly prefer to learn a broad range of findings from their sequencing[14], often including findings with limited medical actionability[6]. This assumption and evidence has motivated ongoing debate about whether and how to accommodate people’s preferences in clinical settings and research[14], including a call for research to inform revision and harmonization of regulations governing research participants’ access to their sequencing findings[15].

For diagnostic genomic sequencing and other sequencing applications that take patient preferences and consent into account, current practice supports informed decision making by providing people with education about topics that include the possibility of learning different types of findings from high-throughput genomic tests[16, 17], the potential value of this information, possible errors in interpretation, limitations of current technologies and scientific knowledge, evolving scientific and medical knowledge, and potential medical and/or psychosocial harms[18–20]. Similar education can be offered for additional findings, although it is unclear if this is common practice. Evidence regarding effects of this education and the option to learn additional findings would provide useful guidance for the field. Accordingly, we sought to investigate whether this education and option have harmful or beneficial effects on psychosocial outcomes and health behaviors in people undergoing diagnostic sequencing, for whom this education and the option to request additional genomic findings is layered upon pre-existing challenges such as poor health, strains caused by a diagnostic odyssey, and distress due to uncertainty (e.g., regarding the meaning of their diagnostic results, complexity of the information they are given, or their future health)[21, 22]. It is therefore important to consider the potential impact of providing education about and the option to request additional genomic findings.

1.1. Overview of the present study

The North Carolina Clinical Genomic Evaluation by NextGen Exome Sequencing (NCGENES) study[23] recruited adult and pediatric patients with a suspected genetic disorder to undergo diagnostic exome sequencing and receive their positive, uncertain, or negative diagnostic results. Participants also received medically actionable secondary findings in the rare case that any were found. In an embedded randomized controlled trial, eligible adult patients who received diagnostic results but no medically actionable secondary findings were randomized to either receive their diagnostic findings only (“Diagnostic Findings” group; DF) or their diagnostic findings plus education about a specified set of additional genomic findings and the option to request them (“Diagnostic Findings + Education about Additional Findings” group; DF+EAF).

Thus, the DF+EAF group layered education and the option to request additional genomic findings onto the potentially stressful diagnostic sequencing experience. Decision making research suggests that adding an additional challenge to a stressful situation could adversely affect psychosocial and behavioral outcomes. For instance, one meta-analysis showed that features of a decision associated with higher psychological “choice overload” (e.g., complex choices, difficult decision tasks, preference uncertainty) are associated with greater decision regret and lower satisfaction with and confidence in choices[24]. If education about and the option to request additional genomic findings is added to diagnostic sequencing, this addition could increase burden and distress, such as anxiety or uncertainty[21, 22]. Conversely, providing access to additional genomic findings could confer benefit. It is consistent with the strong favorable attitudes people generally report when asked their preferences about accessing personal genomic information[18]. It is also consistent with commonly expressed view that “knowledge is power”[25]. Also, people may respond favorably to getting more information if they construe it as something positive coming out of their sequencing experience [26, 27]. Research on people facing chronic conditions or health risk shows that this kind of positive response could bring about positive psychosocial outcomes and health behaviors[28].

In sum, research supports the plausibility of either negative or positive effects of receiving education about additional genomic findings and having the option to request them. Consequently, the present study explored research questions rather than testing hypotheses. NCGENES was designed to be an exploratory study[3] investigating whether providing participants with education regarding additional genomic findings and the option to request them would influence their psychosocial and behavioral outcomes in the short-term (two weeks after education delivery) and long-term (three and six months after education delivery). Outcomes included those that have been examined in past genomic research and that could be influenced by the education and option we offered, including test-related distress, positive experiences, and uncertainty; generalized anxiety and depressive symptoms; decision regret; information seeking difficulty; and self-reported healthcare utilization. Our primary outcome was test-related distress two weeks after education delivery.

2. Methods

2.1. Ethics statement

This study was performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations, including those set forth in the Declaration of Helsinki. Participants provided informed consent, and de-identified data were used for analyses and reporting. Procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC) and Vidant Medical System in Greenville, NC. The study was registered on clinicaltrials.gov (NCT01969370).

2.2. Participants

Participants were enrolled in NCGENES—part of the National Institutes of Health-funded Clinical Sequencing Exploratory Research (CSER) consortium. NCGENES participants were adult and pediatric patients referred from clinics at UNC and Vidant Medical Center[29]. Eligible patients had a health condition with a suspected genetic cause, selected from pre-specified diagnostic categories (e.g., possible hereditary cancer syndrome, cardiogenetics, neurodevelopmental). NCGENES participants had diagnostic exome sequencing and received their diagnostic sequencing findings (negative, uncertain, or positive) along with any medically actionable secondary findings we found, guided by a list created through expert consensus[30]. To be included in the present randomized controlled trial substudy, NCGENES participants had to be ≥18 years old and cognitively intact according to clinical judgment, and they had to attend an in-person study visit to receive their diagnostic sequencing results. We excluded participants who received a medically actionable secondary finding in NCGENES to limit burden placed on them. Substudy participants were enrolled in NCGENES between August, 2012, and January, 2016.

2.3. Procedures

We contacted referred patients to schedule an NCGENES enrollment visit, then mailed them a confirmation letter, consent/HIPAA forms, an intake questionnaire, and an initial study brochure describing exome sequencing, possible diagnostic results, and medically actionable secondary findings. The enrollment visit began with informed consent procedures, completed by a certified genetic counselor who described the study, diagnostic findings that could be returned (after confirmation in a CLIA-certified lab), medically actionable secondary findings, randomization, and potential to be randomized into a group that could request additional genomic findings, which were not described in detail. Immediately after consenting, participants submitted their completed intake questionnaire, completed a measure of health literacy[31], and had blood drawn for sequencing before ending their enrollment visit. Approximately two weeks later, they completed the Time 1 assessment (structured phone interview and mailed questionnaire). Approximately 6–12 months later, when their diagnostic results were ready, a staff member called to schedule an in-person follow-up visit. The staff member randomized participants and revealed their study arm assignment on this call. Participants were then mailed study materials appropriate to their assigned group. Both groups received a letter confirming their scheduled follow-up visit. DF+EAF participants also received an educational study brochure describing categories of additional genomic findings (see “Study arms”). At the follow-up visit, participants met with a study medical geneticist and genetic counselor to learn and receive counseling about their diagnostic findings. For DF+EAF participants, the clinicians then transitioned to discussing additional genomic findings and answering questions about them. Next, a study interviewer administered measures focused on additional genomic findings (e.g., intentions to learn them, reported previously[6]) before ending the visit. All participants completed the Time 2 assessment two weeks later (structured phone interview and mailed questionnaire), followed by structured phone interviews three and six months later (Times 3 and 4).

2.4. Study arms

DF+EAF group:

Because our additional genomic findings were highly heterogeneous, we grouped them into six categories representing similar clinical and psychosocial risk profiles[32]. This study arm’s educational brochure (see online supplement) described the chance for individuals to have genetic variants in any of the six categories, the potential benefits and harms of learning each category (including a discussion of medical actionability or lack thereof), procedures for requesting them, and how findings for each category would be returned if requested (see Table 1). It also included a simple values clarification exercise to support decision making[33]. At the follow-up visit, study clinicians (who had been part of the expert team that developed the brochure’s content) reviewed information from the brochure with participants in this study arm. The clinicians informed participants that we would not seek or interpret their additional genomic findings unless participants requested them. Thus, education about additional genomic findings was both standardized across patients (the brochure) and individualized (in-person education delivered by experienced clinicians who reiterated information in the brochure and extended it to account for each participant’s unique medical situation and questions). Fidelity across clinicians was enhanced through discussion at regular study team meetings.

Table 1:

Summary of additional genomic sequencing finding categories and methods for requesting them

| Category | Name of category | Description of category | Examples provided | Description of result most likely to be learned | Description of medical management | Method for learning resultsa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Risks for Common Diseases | Variants, called SNPs, that may slightly affect your risks for common diseases | Typical forms of heart disease, cancer, and diabetes | Average or slightly different risk compared to the general population | Routine recommendations such as eating right and getting exercise | Telephone |

| B | Pharmacogenomics | Variants that affect how your body responds to some medicines | Response to the blood thinner, Coumadin | Average or slightly different risk compared to the general population. | Possible change in the amount of medicine or avoidance of other medicine | Telephone |

| C | Carrier Status for Autosomal Recessive Conditions | Variants that do not usually affect your health but that increase the risk for health problems in your children and others in future generations | Cystic fibrosis, sickle cell anemia and many others | Everyone is expected to have 4 to 8 positive results. | No personal health problems | One in-person visit |

| D | Risk for the Common Form of Alzheimer’s Disease | Variants in the APOE gene that affect your risk, as compared to the average person, of getting the common form of Alzheimer’s Disease | Typical form of Alzheimer’s Disease | Average or slightly different risk compared to the general population | Routine recommendations such as eating right and getting exercise. | One in-person visit |

| E | Rare Genetic Diseases | Rare variants in genes that directly cause you to have an increased risk for a genetic disease that cannot be prevented, but that may have some treatments after symptoms develop | Adult polycystic kidney disease, factor V Leiden and many others | Normal | For some conditions, some symptoms can be treated | One in-person visit |

| F | Very rare variants in genes that directly cause severe and progressive diseases of the brain and nervous system that cannot be prevented and that have no effective treatments | Very rare variants in genes that directly cause severe and progressive diseases of the brain and nervous system that cannot be prevented and that have no effective treatment | Lou Gehrig’s Disease (ALS) and others | Normal | No prevention No treatment | Two in-person visits |

The one in-person visit for categories C through E were the same visit if participants requested findings from multiple categories, and this visit could also serve as the first of the two required category F visits.

DF group:

Participants in this study arm did not receive the brochure about additional genomic findings or the in-person education about these findings at their follow-up visit; however, study clinicians answered any direct questions about other genomic findings.

2.5. Study Design, Randomization, and Concealment

This was a two-arm randomized controlled trial with parallel groups. Participants were assigned in a 1:1 ratio to the DF or DF+EAF group using computer-generated permuted block randomization (varied randomly blocks of two, four, and six) using a randomization schedule created by the study biostatistician. Concealment was implemented electronically within a data management system with strictly limited access to information about randomization. Follow up assessments were administered by interviewers who were blind to random assignment.

2.6. Measures

Sociodemographic variables.

In the intake questionnaire, participants self-reported their gender, race/ethnicity, marital/partner status, education, work status, insurance status, country of origin, language preference, and annual household income.

Medical variables.

Clinicians who referred patients reported their diagnosis/symptoms, which we confirmed and supplemented at enrollment. In the intake questionnaire, participants rated their physical functioning using a self-report version of the Karnofsky scale[34] (1=able to carry on normal activity with no complaints to 8=severely disabled) and reported whether they had genetic testing prior to NCGENES (0=no, 1=yes). Diagnostic results (0=Negative, 1=Positive, 2=Uncertain) were determined from participants’ exome sequencing by study molecular genetics experts.

Test-related distress, positive experiences, and uncertainty were assessed in the Time 2, 3, and 4 interviews with the Multidimensional Impact of Cancer Risk Assessment (MICRA)[35]. Respondents reported how often in the past week they experienced the following responses to their test results: distress (six items; e.g., feeling upset or sad), positive experiences (four items; e.g., feeling relieved), and uncertainty (10 items; e.g., being uncertain about the meaning of the results for risk). We adapted item wording for interview administration (“your” instead of “my”), return of multiple findings (“test results” rather than “test result”), and use of exome sequencing rather than BRCA1/2 testing. Responses (0=Never, 1=Rarely, 3=Sometimes, or 5=Often) were averaged for each subscale (Cronbach’s alphas from 0.86–0.88 for distress, 0.71–0.84 for positive experiences, 0.84–0.89 for uncertainty).

Generalized anxiety and depressive symptoms were assessed in interviews at all timepoints with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)[36], which assesses anxiety and depressive symptoms with two seven-item subscales. Responses were provided on a scale from 0 to 3 (with different labels across items) and summed. Higher scores indicate greater symptoms (Cronbach’s alphas from 0.84–0.86 for anxiety, 0.80–0.82 for depressive symptoms).

Decision regret was assessed at Times 2, 3, and 4 with the five-item Decision Regret Scale[37]. Participants rated how they felt about their decision to have exome sequencing (e.g., “It was the right decision”). Responses (1=Strongly disagree to 5=Strongly agree) were reverse scored as necessary, then averaged. Higher scores indicate greater regret (Cronbach’s alphas from 0.83–0.90).

Information seeking difficulty was assessed at Time 2 with five items adapted from the Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS) (e.g., “It took a lot of effort to get the information I needed”). Responses (1=Strongly disagree to 5=Strongly agree) were averaged. Higher scores indicate greater difficulty (Cronbach’s alpha=0.84).

Healthcare utilization was assessed in interviews at all timepoints with an item adapted from the Hospital Utilization and Access to Care questionnaire in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). Participants reported how many times they had seen a doctor or other health care professional about their health at a doctor’s office, clinic, hospital emergency room, at home, or some other place in the past 12 months (Time 1) or since their last NCGENES assessment (Times 2–4). Responses (1=1 time, 2=2–3 times, 3=4–9 times, 4=10–12 times, or 5=13+ times) were divided by 52 weeks for Time 1 responses or the number of weeks since the participant’s prior survey for Times 2–4 to estimate healthcare utilization per week.

Data analysis

First, we generated descriptive statistics and examined the psychometric properties of study variables. Next, we conducted two-sample t-tests (continuous variables) and chi-square tests (categorical variables) to evaluate differences between the study arms at Time 1. We then conducted generalized estimating equations (GEE), using an unstructured correlation matrix, to evaluate group differences in measures at Times 2, 3, and 4. This approach uses all available data; cases are not dropped for missing data. These models were adjusted for outcomes assessed at Time 1 (generalized anxiety, depressive symptoms, healthcare utilization only) and included Time × Group (study arm) interactions to evaluate group differences in trajectories of outcomes measured in more than one follow-up assessment. Because our measure of test-related distress was skewed at Times 3 and 4, we used robust variance estimation for the 95% confidence intervals and hypothesis testing.

Statistical power

We expected to randomize 190 participants into each study arm with ~5% dropout. Based on the estimated effect sizes of d=0.33 and 0.5, we anticipated reaching 88% and >99% power, respectively, for group comparisons under type-I error alpha equaling 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Sample

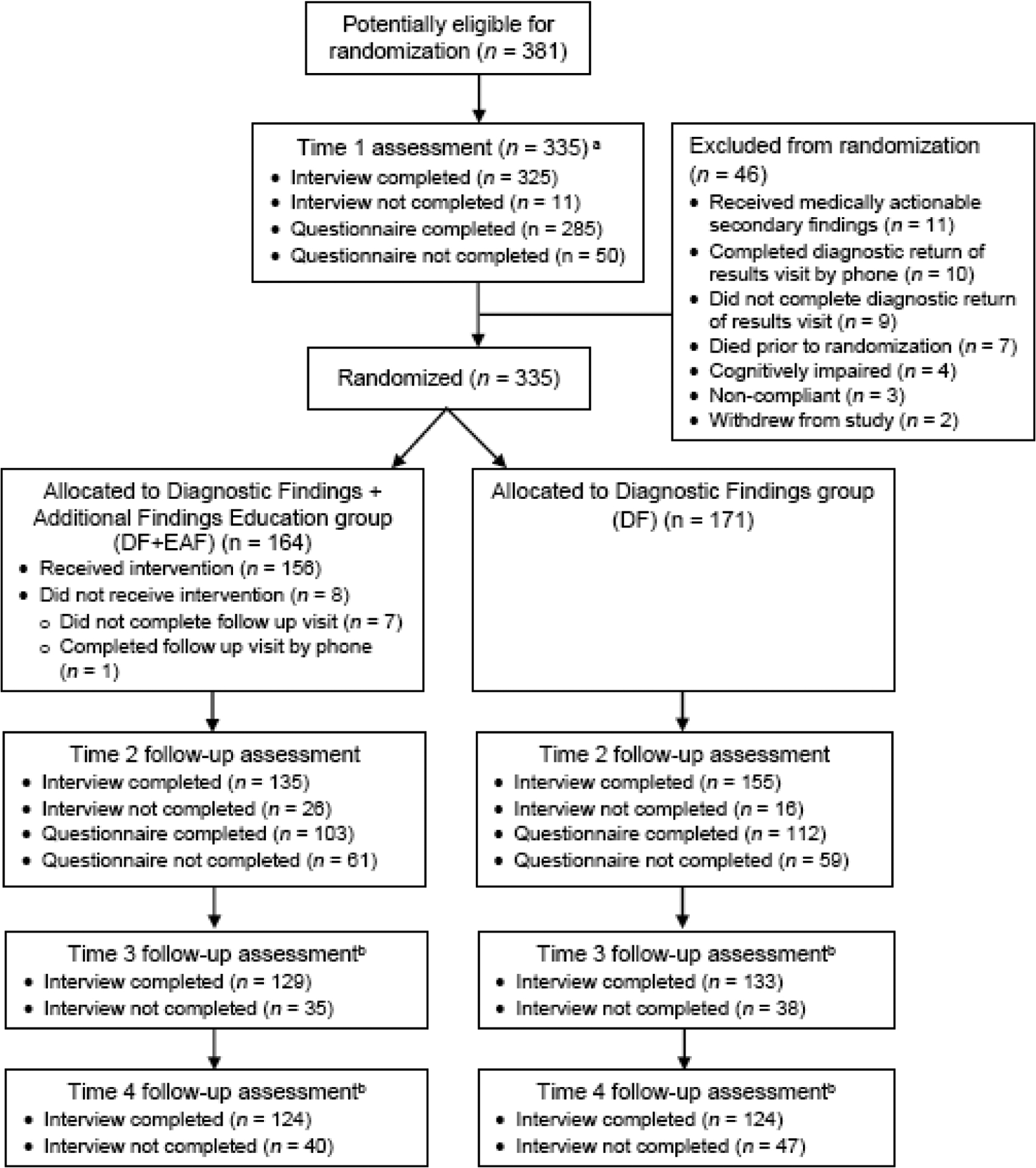

Of 381 adult patients enrolled in NCGENES, n=46 (12.1%) were not randomized: 11 received medically actionable secondary findings, 10 completed their follow-up visit by phone, 9 did not complete the follow-up visit, 7 died prior to randomization, 7 were cognitively impaired, 3 were non-compliant, and 2 withdrew prior to their follow-up visit. The remaining 335 were randomized. Figure 1 summarizes their flow through the study. Table 2 summarizes participant characteristics. The study arms did not differ in sociodemographic or medical characteristics, so we did not include these covariates in the multivariate models. There were also no group differences in outcomes measured at Time 1 (generalized anxiety, depressive symptoms, healthcare utilization; ps=0.74–0.84). Table 3 summarizes descriptive statistics for our outcomes and findings from analyses.

Figure 1:

Trial Flow Chart

a Time 1 completion statistics are provided for the randomized sample of n = 335; randomization occurred after the Time 1 assessment.

b The Time 3 and Time 4 assessments included interviews only; no questionnaires were administered at these assessments.

Table 2:

Sample descriptive statistics (N=335)

| Variables | DF+EAF group | DF group | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n=164) | (n=171) | ||||

| M (SD) | n (%) | M (SD) | n (%) | p-value | |

| Age | 48.7 (13.7) | 47.5 (14.9) | 0.46 | ||

| Female gender | 115 (70.6%) | 113 (66.1%) | 0.38 | ||

| Race/ethnicity | 0.62 | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 120 (73.2%) | 121 (71.3%) | |||

| African American/Black | 27 (16.5%) | 29 (17.0%) | |||

| Hispanic/Latinx | 9 (5.5%) | 12 (7.0%) | |||

| Asian | 3 (1.8%) | 2 (1.2%) | |||

| Other/Mixed | 4 (2.4%) | 5 (2.9%) | |||

| Missing | 1 (0.6%) | 2 (0.6%) | |||

| Had spouse or partner (partnered) | 127 (78.4%) | 121 (71.2%) | 0.13 | ||

| Annual household income (median range) | $45,000–59,999 | $60,000–74,999 | 0.60 | ||

| < $29,999 | 47 (28.7%) | 47 (27.5%) | |||

| $30,000 to < $60,000 | 29 (17.6%) | 32 (18.7%) | |||

| $60,000 to < $90,000 | 34 (20.8%) | 27 (15.8%) | |||

| $90,000 to < $120,000 | 15 (9.2%) | 10 (5.8%) | |||

| ≥ $120,000 | 28 (17.0%) | 39 (22.8%) | |||

| Missing | 11 (6.7%) | 16 (9.4%) | |||

| Education | 0.92 | ||||

| Less than high school | 13 (7.9%) | 15 (8.8%) | |||

| High school diploma/GED | 22 (13.4%) | 21 (12.3%) | |||

| Some college | 37 (22.6%) | 38 (22.2%) | |||

| 2-year college degree/technical school | 24 (14.6%) | 26 (15.2%) | |||

| 4-year college degree | 40 (24.4%) | 34 (19.9%) | |||

| Graduate or professional degree | 24 (14.6%) | 36 (21.1%) | |||

| Missing | 4 (2.4%) | 1 (0.6%) | |||

| Working full or part time | 70 (42.7%) | 60 (35.1%) | 0.15 | ||

| Had health insurance | 141 (86.5%) | 157 (91.8%) | 0.12 | ||

| Born in United States | 150 (92.6%) | 153 (90.5%) | 0.50 | ||

| English language preferred | 158 (96.3%) | 167 (97.7%) | 0.48 | ||

| Health Literacy (REALM[30]) | 62.47 (7.90) | 62.72 (7.28) | 0.77 | ||

| Prior genetic test | 79 (53.4%) | 80 (54.1%) | 0.91 | ||

| Diagnostic category | |||||

| Cancer (personal or family history) | 60 (36.6%) | 52 (30.4%) | |||

| Cardiogenetics | 33 (20.1%) | 22 (12.9%) | |||

| Neurodevelopmental | 14 (8.5%) | 18 (10.5%) | |||

| Other condition | 57 (34.8%) | 78 (45.6%) | |||

| Diagnostic findings | 0.49 | ||||

| Negative | 104 (63.4%) | 117 (68.4%) | |||

| Uncertain | 35 (21.3%) | 28 (16.4%) | |||

| Positive | 25 (15.2%) | 26 (15.2%) | |||

| Outcome variables assessed at Time 1 | |||||

| Generalized anxiety | 6.94 (4.23) | 6.78 (4.55) | |||

| Depressive symptoms | 4.98 (3.80) | 5.11 (4.20) | |||

| Healthcare utilization | 0.07 (0.03) | 0.07 (0.02) | |||

DF = Group that received Diagnostic Findings only. DF+EAF = Group that received Diagnostic Findings + Additional Findings Education along with option to request additional genomic findings.

Table 3:

Summary of results (N = 335)

| Outcome/effect | DF+EAF group | DF group | β | 95% CI | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n=164) | (n=171) | ||||

| M (SD) | M (SD) | ||||

| Time 2 | |||||

| Test-related distress | 0.39 (0.81) | 0.58 (0.91) | −0.20 | −0.40, −0.01 | 0.043 |

| Test-related positive experiences | 1.76 (1.43) | 1.73 (1.34) | 0.01 | −0.30, 0.33 | 0.934 |

| Test-related uncertainty | 0.92 (0.82) | 1.13 (0.95) | −0.22 | −0.42, −0.02 | 0.035 |

| Generalized anxiety | 5.20 (3.70) | 6.04 (4.38) | −0.74 | −1.38, −0.09 | 0.025 |

| Depressive symptoms | 4.40 (3.37) | 4.63 (4.06) | −0.11 | −0.73, 0.51 | 0.730 |

| Decision regret | 1.48 (0.55) | 1.47 (0.55) | −0.002 | −0.13, 0.12 | 0.978 |

| Information seeking difficulty | 2.31 (0.77) | 2.26 (0.81) | 0.05 | −0.13, 0.23 | 0.583 |

| Self-reported healthcare utilization | 0.08 (0.04) | 0.08 (0.04) | −0.004 | −0.012, 0.004 | 0.281 |

| Time 3 | |||||

| Test-related distress | 0.35 (0.83) | 0.39 (0.71) | −0.04 | −0.22, 0.14 | 0.671 |

| Test-related positive experiences | 2.46 (1.60) | 2.70 (1.56) | −0.32 | −0.69, 0.05 | 0.093 |

| Test-related uncertainty | 0.74 (0.84) | 0.80 (0.84) | −0.08 | −0.27, 0.12 | 0.451 |

| Generalized anxiety | 5.54 (3.99) | 6.20 (4.52) | −0.55 | −1.29, 0.18 | 0.141 |

| Depressive symptoms | 4.43 (3.48) | 4.90 (4.14) | −0.41 | −1.05, 0.24 | 0.221 |

| Decision regret | 1.53 (0.57) | 1.49 (0.52) | 0.04 | −0.08, 0.17 | 0.497 |

| Self-reported healthcare utilization | 0.16 (0.11) | 0.18 (0.13) | −0.02 | −0.04, 0.01 | 0.244 |

| Time 4 | |||||

| Test-related distress | 0.36 (0.85) | 0.36 (0.65) | −0.01 | −0.19, 0.17 | 0.916 |

| Test-related positive experiences | 2.36 (1.73) | 2.67 (1.72) | −0.38 | −0.79, 0.03 | 0.070 |

| Test-related uncertainty | 0.75 (0.89) | 0.78 (0.91) | −0.06 | −0.27, 0.16 | 0.595 |

| Generalized anxiety | 5.43 (3.83) | 5.71 (4.52) | −0.15 | −0.83, 0.54 | 0.679 |

| Depressive symptoms | 4.26 (3.52) | 4.44 (4.05) | −0.07 | −0.77, 0.64 | 0.854 |

| Decision regret | 1.56 (0.62) | 1.49 (0.54) | 0.09 | −0.05, 0.24 | 0.193 |

| Self-reported healthcare utilization | 0.15 (0.09) | 0.15 (0.10) | 0.001 | −0.02, 0.02 | 0.945 |

DF = Group that received Diagnostic Findings only. DF+EAF = Group that received Diagnostic Findings + Additional Findings Education along with option to request additional genomic findings.

3.2. Effects of group assignment on short-term test-related distress (Time 2)

The model evaluating effects of Study Arm on our primary outcome, test-related distress two weeks after the follow-up visit (Time 2), revealed that short-term test-related distress was lower for DF participants than for DF+EAF participants.

3.3. Effects of group assignment on secondary outcomes

Findings showed no evidence for group differences in test-related distress at Times 3 or 4. The Time × Group interaction for test-related distress was not significant (p=.06), indicating lack of support for a study arm difference in trajectories of test-related distress.

For test-related positive experiences, there were no group differences at Times 2–4. The Time × Group interaction was not significant (p=0.11).

For test-related uncertainty, DF participants reported greater uncertainty than did DF+EAF participants at Time 2, but the groups did not differ at Times 3 or 4. The Time × Group interaction was not significant (p=0.13).

For generalized anxiety, DF participants reported greater anxiety than did DF+EAF participants at Time 2, but there were no group differences at Times 3 or 4. The Time × Group interaction was not significant (p=0.17).

For other secondary outcomes (test-related positive experiences, depressive symptoms, decision regret, information seeking difficulty, self-reported healthcare utilization), there was no group difference at Times 2–4, nor did the Time × Group interactions reach significance for the secondary outcomes assessed at multiple assessments.

4. Discussion and Conclusion

4.1. Discussion

We explored short- and long-term psychosocial and behavioral outcomes in two groups of adults undergoing diagnostic exome sequencing in the context of research: a group that received only their diagnostic findings and a group that received diagnostic findings (DF) plus education regarding additional genomic findings and the option to request them (DF+EAF). Our participants were on a diagnostic odyssey and/or dealing with a known clinical diagnosis, poor health, and uncertainty about their own and their family’s future health. Two weeks after receiving their diagnostic results and the education we investigated, participants in the DF+EAF group had lower test-related distress, test-related uncertainty, and generalized anxiety than did participants in the DF group. These benefits were no longer significant three and six months later. We did not observe group differences for other outcomes. In short, patients did not appear to experience a negative effect that could indicate choice overload[24]. Rather, they demonstrated limited short-term benefits but no lasting benefit or harm. Although short-lived, benefits were reported at a meaningful time point during a potentially distressing process. Reduced distress and uncertainty could make a difference in patients’ lives in that moment, even if temporary.

These findings could reflect short-term positive responses to the possibility of getting additional health-relevant information, consistent with research showing favorable attitudes toward learning additional genomic findings[6] and the common belief that “knowledge is power”[25]. Few participants later requested these findings and mainly received them after the study ended, so it is perhaps not surprising that these benefits were short-lived. It is also possible that the findings reflect short-term harms for DF group participants, who were broadly aware that their sequencing could yield some kind of additional findings and that they were assigned to a group not able to learn these findings. The distinction between short term benefits for one group versus short term harms for the other group is difficult to disentangle in this study, but qualitative research could be useful for clarifying the nuances of participants’ responses.

Our Time 2 findings could also occur if DF+EAF participants believe that their additional genomic findings could eventually provide insight into their health concern—a misperception that our clinical team often observed despite having provided clear education to the contrary[27]. This belief could stem from participants’ more general belief that “knowledge is power”[25] and/or common self-protective cognitive mechanisms through which people find positive meaning in threatening situations[26, 27]. Theory-based research would help elucidate the potentially complex explanations for these effects.

Prior research in this sample evaluated DF+EAF participants’ intentions to request at least some of their additional genomic findings[6] and their actual requests[7]. Fifty participants requested at least some additional genomic findings: 54% requested all six categories, 22% requested all but category F, and 24% requested other combinations with no apparent pattern[7]. We have not yet studied how this small subset of participants responded to receiving their results, which always occurred after Time 2 (usually after participants completed the study). Studying these responses will be complicated because each participant received information about a different number of genes and variants, including some indicating increased health risks and others indicating reduced health risks. These responses would not affect our approach to evaluating group differences, however, which was a standard approach for analyzing a rigorous randomized controlled trial.

It is important to consider how our study has been affected by evolution in how the clinical and scientific communities think about return of various types of secondary findings, including those we refer to as additional genomic findings. We designed NCGENES to inform best practices for returning these findings at a time when experts were debating pressing research questions about the pros and cons of returning them and best practices for returning them. The ACMG recommendations, released in 2013 after this study started in 2012[5], subsequently focused the field’s attention on secondary findings similar to the medically actionable secondary findings returned routinely along with participants’ diagnostic results in NCGENES. Yet, our investigation of education about and the option to request additional genomic findings with limited medical actionability remains highly relevant in light of evolving recommendations about return of secondary findings[e.g., 4, 14, 15] as well as growing use of high-throughput genomic sequencing methods in research (where return of additional genomic findings may be considered for various reasons), consumer-driven broad sequencing applications, and continued investigation of how patients are affected by making decisions about getting all types of information from genomic sequencing. Despite changes in the field and in recommendations for returning secondary and additional genomic findings, our results provide a broad and relevant foundation for these contexts.

This study had several limitations. First, generalizability may be limited by our sample’s relatively high education and prior experience with genetic testing. Additionally, we did not systemically assess the specific content of discussions between participants and study staff. Also, DF group participants were aware that their sequencing data could contain additional genomic information, although they received only a broad, brief explanation of this potential and were told that the data would remain unanalyzed. Because providers in a clinical setting are more likely to focus on possible diagnostic results rather than additional findings that patients will not receive, this feature of our study may reduce generalizability to clinical diagnostic settings. However, this limitation is reduced by the fact that some patients in clinical settings currently learn about their option to request carrier and pharmacogenomic findings. Finally, we offered DF+EAF participants a complex set of findings that may have been challenging to understand. Our findings may not apply to more focused or less complex sets of findings.

The study also had notable strengths, including a large sample that was diverse in terms of race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status, and use of a rigorous randomized controlled trial design that enabled evaluation of a novel research question.

4.2. Conclusion

Our findings revealed how patients undergoing diagnostic genomic sequencing may respond to learning about and having the option to request genomic findings with medical actionability that falls below the high degree of actionability covered by current ACMG recommendations. As recommendations for returning a broader range of genomic findings continue to evolve—for instance, recommendations for returning them in research or commercial testing—the need for evidence that informs policy becomes increasingly pressing. This study provided useful and novel information relevant to that need.

4.3. Practice Implications

There appear to be limited benefits and no harms of providing patients with education about, and the opportunity to learn, a broad range of genomic findings in the context of diagnostic genomic sequencing. These findings may be useful for guiding practice decisions and communication of the likelihood of potential benefits and harms in informed consent procedures.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Genomic sequencing can yield findings unrelated to primary sequencing indication

Education about them and the option to learn them may burden or benefit patients

Findings show a few benefits and no harms of providing this education and option

Findings may inform recommendations for returning a broad range of genomic findings

Acknowledgements

Research reported in this publication was supported by National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI), the National Cancer Institute (NCI) and the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD) of the National Institutes of Health under award number U01HG006487 (PIs: James P. Evans, Jonathan S. Berg, Karen E. Weck, Kirk C. Wilhelmsen, and Gail E. Henderson). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or of the U.S. Government Accountability Office. We would like to thank Noel Brewer for his involvement in early plans for the study, Elizabeth Moore for her assistance with data collection, and the patients who participated in this research. Trial registration: clinicaltrials.gov NCT01969370.

Required informed consent and patient details statement: I confirm all patient/personal identifiers have been removed or disguised so the patient/person(s) described are not identifiable and cannot be identified through the details of the story.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declarations of interest: none.

References

- [1].Wise AL, Manolio TA, Mensah GA, Peterson JF, Roden DM, Tamburro C, Williams MS, and Green ED, Genomic medicine for undiagnosed diseases, Lancet 394 (2019) 533–540. 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31274-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Strande NT, and Berg JS, Defining the Clinical Value of a Genomic Diagnosis in the Era of Next-Generation Sequencing, Annu. Rev. Genomics Hum. Genet 17 (2016) 303–332. 10.1146/annurev-genom-083115-022348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Berg JS, Amendola LM, Eng C, Van Allen E, Gray SW, Wagle N, Rehm HL, DeChene ET, Dulik MC, Hisama FM, Burke W, Spinner NB, Garraway L, Green RC, Plon S, Evans JP, and Jarvik GP, Processes and preliminary outputs for identification of actionable genes as incidental findings in genomic sequence data in the Clinical Sequencing Exploratory Research Consortium, Genet. Med 15 (2013) 860–867. 10.1038/gim.2013.133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Kalia SS, Adelman K, Bale SJ, Chung WK, Eng C, Evans JP, Herman GE, Hufnagel SB, Klein TE, Korf BR, McKelvey KD, Ormond KE, Richards CS, Vlangos CN, Watson M, Martin CL, and Miller DT, Recommendations for reporting of secondary findings in clinical exome and genome sequencing, 2016 update (ACMG SF v2.0): a policy statement of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics, Genet. Med 19 (2017) 249–255. 10.1038/gim.2016.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Green RC, Berg JS, Grody WW, Kalia SS, Korf BR, Martin CL, McGuire AL, Nussbaum RL, O’Daniel JM, Ormond KE, Rehm HL, Watson MS, Williams MS, Biesecker LG, and American College of Medical, and Genomics, ACMG recommendations for reporting of incidental findings in clinical exome and genome sequencing, Genet. Med 15 (2013) 565–74. 10.1038/gim.2013.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Rini C, Khan CM, Moore E, Roche MI, Evans JP, Berg JS, Powell BC, Corbie-Smith G, Foreman AKM, Griesemer I, Lee K, O’Daniel JM, and Henderson GE, The who, what, and why of research participants’ intentions to request a broad range of secondary findings in a diagnostic genomic sequencing study, Genet. Med 20 (2018) 760–769. 10.1038/gim.2017.176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Roche MI, Griesemer I, Khan CM, Moore E, Lin FC, O’Daniel JM, Foreman AKM, Lee K, Powell BC, Berg JS, Evans JP, Henderson GE, and Rini C, Factors influencing NCGENES research participants’ requests for non-medically actionable secondary findings, Genet. Med 21 (2019) 1092–1099. 10.1038/s41436-018-0294-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Hamilton JG, Shuk E, Genoff MC, Rodriguez VM, Hay JL, Offit K, and Robson ME, Interest and attitudes of patients with advanced cancer with regard to secondary germline findings from tumor genomic profiling, J. Oncol. Pract 13 (2017) e590–e601. 10.1200/JOP.2016.020057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Brothers KB, East KM, Kelley WV, Wright MF, Westbrook MJ, Rich CA, Bowling KM, Lose EJ, Bebin EM, Simmons S, Myers JA, Barsh G, Myers RM, Cooper GM, Pulley JM, Rothstein MA, and Clayton EW, Eliciting preferences on secondary findings: the Preferences Instrument for Genomic Secondary Results, Genet. Med 19 (2017) 337–344. 10.1038/gim.2016.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Hart MR, Biesecker BB, Blout CL, Christensen KD, Amendola LM, Bergstrom KL, Biswas S, Bowling KM, Brothers KB, Conlin LK, Cooper GM, Dulik MC, East KM, Everett JN, Finnila CR, Ghazani AA, Gilmore MJ, Goddard KAB, Jarvik GP, Johnston JJ, Kauffman TL, Kelley WV, Krier JB, Lewis KL, McGuire AL, McMullen C, Ou J, Plon SE, Rehm HL, Richards CS, Romasko EJ, Miren Sagardia A, Spinner NB, Thompson ML, Turbitt E, Vassy JL, Wilfond BS, Veenstra DL, Berg JS, Green RC, Biesecker LG, and Hindorff LA, Secondary findings from clinical genomic sequencing: prevalence, patient perspectives, family history assessment, and health-care costs from a multisite study, Genet. Med (2019) 21, 1100–1110. 10.1038/s41436-018-0308-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Wynn J, Lewis K, Amendola LM, Bernhardt BA, Biswas S, Joshi M, McMullen C, and Scollon S, Clinical providers’ experiences with returning results from genomic sequencing: an interview study, BMC Med. Genomics 11 (2018) 45. 10.1186/s12920-018-0360-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Wynn J, Martinez J, Bulafka J, Duong J, Zhang Y, Chiuzan C, Preti J, Cremona ML, Jobanputra V, Fyer AJ, Klitzman RL, Appelbaum PS, and Chung WK, Impact of receiving secondary results from genomic research: a 12-month longitudinal study, J. Genet. Couns 27 (2018) 709–722. 10.1007/s10897-017-0172-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Sapp JC, Johnston JJ, Driscoll K, Heidlebaugh AR, Miren Sagardia A, Dogbe DN, Umstead KL, Turbitt E, Alevizos I, Baron J, Bonnemann C, Brooks B, Donkervoort S, Jee YH, Linehan WM, McMahon FJ, Moss J, Mullikin JC, Nielsen D, Pelayo E, Remaley AT, Siegel R, Su H, Zarate C, Program NCS, Manolio TA, Biesecker BB, and Biesecker LG, evaluation of recipients of positive and negative secondary findings evaluations in a hybrid CLIA-research sequencing pilot, Am. J. Hum. Genet 103 (2018) 358–366. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2018.07.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Ormond KE, O’Daniel JM, and Kalia SS, Secondary findings: How did we get here, and where are we going?, J. Genet. Couns 28 (2019) 326–333. 10.1002/jgc4.1098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Returning individual research results to participants: guidance for a new research paradigm, The National Academies Press, Washington, DC, 2018. 10.17226/25094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Appelbaum PS, Fyer A, Klitzman RL, Martinez J, Parens E, Zhang Y, and Chung WK, Researchers’ views on informed consent for return of secondary results in genomic research, Genet. Med 17 (2015) 644–650. 10.1038/gim.2014.163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Weiner C, Anticipate and communicate: ethical management of incidental and secondary findings in the clinical, research, and direct-to-consumer contexts (December 2013 report of the Presidential Commission for the Study of Bioethical Issues), Am. J. Epidemiol 180 (2014) 562–564. 10.1093/aje/kwu217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Delanne J, Nambot S, Chassagne A, Putois O, Pelissier A, Peyron C, Gautier E, Thevenon J, Cretin E, Bruel AL, Goussot V, Ghiringhelli F, Boidot R, Tran Mau-Them F, Philippe C, Vitobello A, Demougeot L, Vernin C, Lapointe AS, Bardou M, Luu M, Binquet C, Lejeune C, Joly L, Juif C, Baurand A, Sawka C, Bertolone G, Duffourd Y, Sanlaville D, Pujol P, Genevieve D, Houdayer F, Thauvin-Robinet C, and Faivre L, Secondary findings from whole-exome/genome sequencing evaluating stakeholder perspectives. A review of the literature, Eur. J. Med. Genet 62 (2019) 103529. 10.1016/j.ejmg.2018.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Burke W, Matheny Antommaria AH, Bennett R, Botkin J, Clayton EW, Henderson GE, Holm IA, Jarvik GP, Khoury MJ, Knoppers BM, Press NA, Ross LF, Rothstein MA, Saal H, Uhlmann WR, Wilfond B, Wolf SM, and Zimmern R, Recommendations for returning genomic incidental findings? We need to talk!, Genet. Med 15 (2013) 854–859. 10.1038/gim.2013.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Butterfield RM, Evans JP, Rini C, Kuczynski KJ, Waltz M, Cadigan RJ, Goddard KAB, Muessig KR, and Henderson GE, Returning negative results to individuals in a genomic screening program: lessons learned, Genet. Med 21 (2019) 409–416. 10.1038/s41436-018-0061-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Bartley N, Napier C, Best M, and Butow P, Patient experience of uncertainty in cancer genomics: a systematic review, Genet. Med 22 (2020) 1450–1460. 10.1038/s41436-020-0829-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Han PKJ, Umstead MS KL, Bernhardt BA, Green RC, Joffe S, Koenig B, Krantz I, Waterston LB, Biesecker LG, and Biesecker BB, A taxonomy of medical uncertainties in clinical genome sequencing, Genet. Med 19 (2017) 918–925. 10.1038/gim.2016.212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Roche MI, and Berg JS, Incidental findings with genomic testing: implications for genetic counseling practice, Curr. Genet. Med. Rep 3 (2015) 166–176. 10.1007/s40142-015-0075-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Chernev A, Böckenholt U, and Goodman J, Choice overload: a conceptual review and meta-analysis, J. Consum. Psychol 25 (2015) 333–358. 10.1016/j.jcps.2014.08.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Mighton C, Carlsson L, Clausen M, Casalino S, Shickh S, McCuaig L, Joshi E, Panchal S, Graham T, Aronson M, Piccinin C, Winter-Paquette L, Semotiuk K, Lorentz J, Mancuso T, Ott K, Silberman Y, Elser C, Eisen A, Kim RH, Lerner-Ellis J, Carroll JC, Glogowski E, Schrader K, and Bombard Y, Development of patient “profiles” to tailor counseling for incidental genomic sequencing results, Eur. J. Hum. Genet 27 (2019) 1008–1017. 10.1038/s41431-019-0352-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Taylor SE, Adjustment to threatening events - a theory of cognitive adaptation,” Am. Psychol 38 (1983) 1161–1173. 10.1037/0003-066X.38.11.1161. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Skinner D, Raspberry KA, and King M, The nuanced negative: Meanings of a negative diagnostic result in clinical exome sequencing, Sociol. Health Illn 38 (2016) 1303–1317. 10.1111/1467-9566.12460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Schiavon CC, Marchetti E, Gurgel LG, Busnello FM, and Reppold CT, Optimism and hope in chronic disease: a systematic review, Front. Psychol 7 (2016) 2022. 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.02022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Moore EG, Roche M, Rini C, Corty EW, Girnary Z, O’Daniel JM, Lin FC, Corbie-Smith G, Evans JP, Henderson GE, and Berg JS, Examining the cascade of participant attrition in a genomic medicine research study: barriers and facilitators to achieving diversity, Public Health Genomics 20 (2017) 332–342. 10.1159/000490519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Berg JS, Foreman AK, O’Daniel JM, Booker JK, Boshe L, Carey T, Crooks KR, Jensen BC, Juengst ET, Lee K, Nelson DK, Powell BC, Powell CM, Roche MI, Skrzynia C, Strande NT, Weck KE, Wilhelmsen KC, and Evans JP, A semiquantitative metric for evaluating clinical actionability of incidental or secondary findings from genome-scale sequencing, Genet. Med 18 (2016) 467–475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Davis TC, Crouch MA, Long SW, Jackson RH, Bates P, George RB, and Bairnsfather LE, Rapid assessment of literacy levels of adult primary care patients, Fam. Med 23 (1991) 433–435. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Berg JS, Khoury MJ, and Evans JP, Deploying whole genome sequencing in clinical practice and public health: meeting the challenge one bin at a time, Genet. Med 13 (2011) 499–504. 10.1097/GIM.0b013e318220aaba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].O’Connor A, and Jacobsen MJ, Workbook on developing and evaluating patient decision aids. https://decisionaid.ohri.ca/docs/develop/Develop_DA.pdf, 2003. (accessed 21 January 2021).

- [34].Wingard JR, Curbow B, Baker F, and Piantadosi S, Health, functional status, and employment of adult survivors of bone marrow transplantation, Ann. Intern. Med 114 (1991) 113–118. 10.7326/0003-4819-114-2-113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Cella D, Hughes C, Peterman A, Chang CH, Peshkin BN, Schwartz MD, Wenzel L, Lemke A, Marcus AC, and Lerman C, A brief assessment of concerns associated with genetic testing for cancer: the Multidimensional Impact of Cancer Risk Assessment (MICRA) questionnaire, Health Psychol. 21 (2002) 564–572. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Zigmond AS, and Snaith RP, The hospital anxiety and depression scale, Acta Psychiatr. Scand 67 (1983) 361–70. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Brehaut JC, O’Connor AM, Wood TJ, Hack TF, Siminoff L, Gordon E, and Feldman-Stewart D, Validation of a decision regret scale, Med. Decis. Making 23 (2003) 281–292. 10.1177/0272989X03256005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.