Abstract

Synthetic biology has been developing rapidly in the last decade and is attracting increasing attention from many plant biologists. The production of high-value plant-specific secondary metabolites is, however, limited mostly to microbes. This is potentially problematic because of incorrect post-translational modification of proteins and differences in protein micro-compartmentalization, substrate availability, chaperone availability, product toxicity, and cytochrome p450 reductase enzymes. Unlike other heterologous systems, plant cells may be a promising alternative for the production of high-value metabolites. Several commercial plant suspension cell cultures from different plant species have been used successfully to produce valuable metabolites in a safe, low cost, and environmentally friendly manner. However, few metabolites are currently being biosynthesized using plant platforms, with the exception of the natural pigment anthocyanin. Both Arabidopsis thaliana and Nicotiana tabacum cell cultures can be developed by multiple gene transformations and CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing. Given that the introduction of heterologous biosynthetic pathways into Arabidopsis and N. tabacum is not widely used, the biosynthesis of foreign metabolites is currently limited; however, therein lies great potential. Here, we discuss the exemplary use of plant cell cultures and prospects for using A. thaliana and N. tabacum cell cultures to produce valuable plant-specific metabolites.

Key words: plant cell culture, synthetic biology, secondary metabolites

Both Arabidopsis thaliana and Nicotiana tabacum cell cultures can be used as bio-factories for the biosynthesis of high-value secondary metabolites in a safe, inexpensive, and environmentally friendly manner. This review discusses recent advances and current challenges in the use of model plant cell cultures for secondary metabolite synthesis.

Introduction

Plants synthesize series of specific secondary metabolites (estimated to be in excess of 200 000) for survival, reproduction, environmental resilience, the establishment of symbiotic relationships, and defense (Guerriero et al., 2018). Many of these chemicals are widely used in pharmaceutical, cosmeceutical, and nutraceutical formulations. Given these industrial interests, several plant secondary metabolites are in huge demand and are highly economically valued. However, such commercially important metabolites are generally present at low abundance and only occur in specific plant organs. Therefore, alternative platforms such as chemical synthesis, transgenic plants/microbes, and plant cell suspension cultures have been proposed for large-scale production of specific metabolites (Table 1). Given the structural and stereochemical intricacies of secondary metabolites, many attempts to produce plant metabolites by complete chemical synthesis have not been very successful. For example, paclitaxel (trade name Taxol) is a chemotherapy drug used in the treatment of various cancers, including ovarian, breast, esophageal, lung, and pancreatic cancer. Although there has been some success in its synthesis using hybrid approaches, the production of paclitaxel remains expensive (Lange, 2018). As most commercial metabolites are not produced by crops or model plants, the use of transgenic platforms to improve metabolite yield is more technically challenging than the use of microbes (Table 1). In addition, few secondary metabolites have been successfully biosynthesized in microbes to date, as the biosynthetic enzymes often require special post-translational modifications, cytochrome p450 (CYP450) reductase (CYR), coenzymes, or micro-compartmentalization (Pyne et al., 2019). Plant suspension cell cultures may overcome most of these limitations and have the advantages of safety, regulatory compliance, scalability, and low cost (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of different platforms.

| Species | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Bacteria | simple genetic content, easy genome sequencing, transformation and scale-up, rapid growth, more developed culture system | difficult to deal with post-translational modification, impaired CYP450 due to absence of endoplasmic reticulum, substrate and product inhibition, bacterial endotoxins requires carbon source and precursors |

| Yeast | simple genetic content, easy transformation and scale-up, rapid growth, more developed culture system | Requires carbon source and precursors, multigene engineering needed, issues with post-translational modification |

| Algae | simple genetic content, scale-up, photoautotrophic, post-translational modification performed, more developed culture system | insufficient genetic engineering tools, long-term growth cycle |

| Plant cell | scale-up, genetic transformation available, moderately rapid growth, post-translational modification performed, Cyt P450 present, constant supply of product, transgenic plant suspension culture has fewer regulatory issues compared with whole plants | requires carbon source and sometimes precursors, complex genetic content of non-model plant suspension culture, genetic instability |

| Native plant | biosynthetic pathway construction generally not required, requires less gene modification, has more toxicity tolerance, has potential to produce on a large scale | low yield, destruction of plant, downstream processing can be difficult, slow growth, requires large amount of natural resource |

| Chemical synthesis | scale-up, easy synthesis, quick | difficult to synthesize plant secondary metabolites with multiple chiral centers; hazardous chemicals, labeled as artificial |

A number of commercial plant suspension cell cultures from various plant species have been used successfully to produce both secondary metabolites like shikonin (Fujita et al., 1981) and paclitaxel (Tabata, 2004) and recombinant proteins like glucocerebrosidase (Hellwig et al., 2004; Kizhner et al., 2015). In addition, there has been increasing interest in plant cell-culture-derived active cosmetic ingredients in the past decade (Barbulova et al., 2014, 2015). Phytochemicals, such as polyphenols, phenolic acids, triterpenes, flavonoids, stilbenes, steroids, carotenoids, steroidal saponins, sterols, fatty acids, polysaccharides, sugars, and peptides, can be extracted with different solvents and used as active ingredients in cosmetic formulations (Georgiev et al., 2018). Plant cell culture is also used in the food industry (Rischer et al., 2020). Cocovanol, a freeze-dried, ground Theobroma cacao powder, can be extracted from T. cacao cell culture (Georgiev, 2015). Despite these achievements, platforms that produce at larger scales are limited by the availability of intercellular metabolites, and the majority of plant secondary metabolites are still derived from native plants, chemical synthesis, or hybrid microbial/semi-chemical synthesis (Arya et al., 2020). In addition, as model plant cell cultures are readily established at low cost, are easy to handle, are fast growing, and have multiple metabolic engineering methods already at hand (Menges and Murray, 2004), such systems provide exciting opportunities for larger-scale metabolite biosynthesis. Here, we discuss methods that utilize traditional heterologous overexpression pathways as well as new genome editing approaches in Arabidopsis thaliana and Nicotiana tabacum to facilitate the use of such cell cultures for the production of plant secondary metabolites.

Plant cell cultures as bio-factories

Since its emergence in the 1950s, plant cell culture technology has enabled the large-scale production of natural products that generally occur in very low amounts (Hellwig et al., 2004; Espinosa-Leal et al., 2018). Plant cell suspension cultures provide a cost-effective alternative to traditional cultivation methods (Kieran et al., 1997; Roberts, 2007) and have been suggested to be more reliable than collecting plants from the wild (Efferth, 2019). In addition to conserving wild populations of species, plant cell cultures are inexpensive to grow and maintain. Moreover, plant cells perform many of the post-translational modifications that rarely occur in prokaryotes, and, with the development of new gene-editing tools, the overexpression of heterologous genes is no longer difficult. With the development of synthetic biotechnology approaches in plants, plant cell culture bio-factories are highly achievable (Kowalczyk et al., 2020) for the production of both metabolites (Shih, 2018; Arya et al., 2020) and proteins (Hellwig et al., 2004).

Producing secondary metabolites in plant cell culture

There are many examples in which plant cells cultured in vitro are capable of synthesizing secondary metabolites. Generally, cultures are generated from the plant organs or tissues in which the desired phytochemical naturally accumulates. For example, roots are used for the production of ginsenoside (Rahimi et al., 2016), seeds of Trigonella spp. are used for the production of diosgenine (Chaudhary et al., 2015), and leaves of Catharanthus roseus are used for the production of vinblastine (Antonio et al., 2013; Parthasarathy et al., 2020). Jatropha curcas cell culture has been improved to scale up for in vitro lipid production (Correa et al., 2020). Nowadays, phenolics, alkaloids, terpenes, and steroids can be produced via plant cell cultures (Figure 1) (Smetanska, 2008). High-value pharmaceutical chemicals (such as paclitaxel, shikonin, and podophyllotoxin; Wilson and Roberts, 2012), fragrance compounds (sesquiterpenoids patchoulol and α/β-santalene; Zhan et al., 2014), antioxidants (Büttner-Mainik et al., 2011), and pigments (Wolf et al., 2010) are synthesized via plant cell cultures. Phenolics are a class of plant-derived secondary metabolites with anticancer, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, and antioxidant activities. Cell cultures have exhibited the capacity to bio-synthesize many of these products in vitro, thereby serving as important alternative sources of such phytochemicals (Ratnadewi, 2017) (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Simplified Scheme of secondary metabolite producing pathways in plant cell

Based on their biosynthetic origins, plant secondary metabolites can be divided into three major groups: Flavonoids and allied phenolic and polyphenolic compounds, alkaloids and terpenoids. Their producing process deeply rely on shikimate pathway or MEP/MVA pathway. Abbreviations: 4CL, 4-coumaroyl-CoA lyase; PAL, phenylalanine ammonia-lyase; TAL, tyrosine ammonia-lyase; 4CL, 4-coumaroyl-CoA lyase; CHS, chalcone synthase; CHI, chalcone isomerase; F3H, flavanone 3-hydroxylase; FLS, flavonol synthase; TDC, tryptophan decarboxylase; STR strictosidine synthase; SLS, secologanin synthase. MVA, Mevalonate; MEP, Methylerythritol phosphate; IPP, Isopentenyl diphosphate; DMAPP, Dimethylallyl pyrophosphate; GPP, Geranyl diphosphate; FPP, Farnesyl diphosphate; GGPP, Geranylgeranyl diphosphate; GFPP, Geranylfarnesyl diphosphate

Figure 2.

Overview of plant cell culture producing secondary metabolites

(A) WT Arabidopsis plant for cell culture. (B) Transformed Arabidopsis cell culture. (C) Scale up culture in bioreactors. (D) Chromatography purification.

Plant species selection

Suspension cultures have been generated from a range of plant species, including A. thaliana, Taxus cuspidata, Catharanthus roseus, and Bryophyta like Physcomitrella patens (Reski et al., 2015; Simonsen et al., 2018), as well as important domestic crops such as tobacco (Wang et al., 2016), alfalfa, rice, tomato, and soybean (Hellwig et al., 2004). These species were chosen because of the availability of their genome sequences, an understanding of their genetics, or their amenability to genetic transformation. The large variety of plants being cultured in vitro provides an opportunity to maintain true-to-type plant species and propagation systems that can produce a large number of plants from a single clone. For example, in vitro manipulation of different Artemisia species, including Artemisia annua, Artemisia sieberi, Artemisia vulgaris, Artemisia japonica, Artemisia nilagirica var. nilagirica, Artemisia absinthium, Artemisia abrotanum, Artemisia amygdalina, Artemisia carvifolia, Artemisia aucheri, Artemisia scoparia, Artemisia judaica, Artemisia chamaemelifolia, and Artemisia pallens, has been attempted for various purposes (Guerriero et al., 2018). To achieve commercial success in sustainable plant secondary metabolite production, the development of innovative transformation techniques to generate stably transformed cell lines with multigene constructs should be a high priority (Arya et al., 2020). Here we propose the use of A. thaliana and N. tabacum cell cultures as prospective bio-factories for metabolite biosynthesis.

A. thaliana and N. tabacum cell cultures as model bio-factories

As one of the most well-studied model plants, A. thaliana can be readily propagated in suspension cell culture. Over the past two decades, several Arabidopsis lines with the potential for large-scale biosynthesis have been developed (At7, T87, PSB-D) (Kwiatkowska et al., 2014; Pucker et al., 2019). Although the At7 genome has large-scale duplications and deletions compared with the Columbia-0 (Col-0) reference sequence and is therefore not widely used, PSB-D cells are a rapid-growing line derived from Ler stem explants and are easily cultivated using liquid Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium in the dark. Cells can be synchronized by applying an aphidicolin block/release or by removing and re-supplying sucrose. Similarly, T87 cells are derived from Col-0 plants and are maintained in liquid MS medium, where they also display rapid growth. Furthermore, both PSB and T87 cells (Segečová et al., 2018; Li et al., 2020) have been shown to generate fully functional chloroplasts when grown in the light. The PSB-D and T87 cell lines are available as Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center stocks and are widely used in plant research, particularly for studying protein-protein interactions and recombinant protein expression (Zhang et al., 2017, 2020b). With regard to tobacco, BY2 cells are derived from N. tabacum cv. Bright Yellow 2 plants (Nagata et al., 1992) and are similarly maintained in liquid MS medium. Although such lines display great potential for large-scale biosynthesis, few secondary metabolites are currently produced in either of these model plant cell cultures. To date, only anthocyanin has been shown to be produced at large scales in both tobacco and Arabidopsis suspension cell cultures, and this was achieved by introducing Rosea1 (AmRos1), an MYB transcription factor, and Delila (AmDel), a bHLH transcription factor, into cells (Appelhagen et al., 2018).

Given that the enzymes involved in secondary metabolite biosynthesis often require the presence of specific CYRs and post-translational modifications, only a few plant-specific metabolites have been synthesized in heterologous expression systems such as Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Guerriero et al., 2018). Plant cell cultures could overcome this limitation, as cytosolic CYRs and similar post-translational modification systems are available. Combined with well-established transformation methods and genome editing approaches, cell cultures derived from model plants such as Arabidopsis and N. tabacum are powerful tools that remain underutilized for the synthesis of organic products such as secondary metabolites.

Introducing heterologous genes into plant cells

Wild-type (Arabidopsis and N. tabacum) cell suspensions can be transformed with recombinant plasmids either by co-cultivation with Agrobacterium tumefaciens or by particle bombardment (Menges and Murray, 2004). There are several significant advantages in transferring DNA via Agrobacterium, including a reduction in transgene copy number, stable integration with fewer rearrangements of long DNA molecules with defined ends, and the ability to generate lines free from selectable marker genes (Smith and Hood, 1995; Cheng et al., 2004). In addition, a binary transformation system developed for plant cells is yet another unexplored strategy. It is based on the constitutive expression of the mutated virG (virGN54D) gene (derived from Agrobacterium), which can potentially mediate the transformation of a diverse range of recalcitrant plant species (Jones et al., 2005). Moreover, particle bombardment remains a robust, relatively efficient method for the genetic manipulation of plants (Dunwell, 2009).

Because the precursors of many metabolites and their corresponding enzymes are present throughout the plant kingdom, the use of both A. thaliana and N. tabacum cell cultures could be a promising alternative approach for synthesizing highly valuable plant secondary metabolites. In many cases, introducing part of a gene(s) from a pathway is sufficient to synthesize the secondary metabolite of interest. For example, vanillin (Chee et al., 2017) and resveratrol (Jeong et al., 2016) have both been successfully synthesized using this approach. In addition, the use of plant cell cultures to produce complex secondary metabolites that require CYP450 enzymes has a competitive advantage over the use of microbes. Various tailoring reactions catalyzed by CYP450 enzymes and their reducing partners (CYRs) are often difficult to express in microbes; however, the relevant genes can be easily engineered in plant cells, in addition to other target genes. For example, the production of heterologous secondary metabolites via multigene insertion has been investigated in different species, including Arabidopsis and N. tabacum (Appelhagen et al., 2018; Ikram et al., 2015). Figure 2 summarizes the main metabolic engineering approaches that have been explored to either enhance endogenous metabolite production or bio-synthesize novel secondary metabolites in plant cell cultures (Eibl et al., 2018).

Furthermore, both native and synthetic promoters have been successfully implemented for heterologous protein expression in plant cell cultures. Such constructs include the cauliflower mosaic virus (CaMV) promoter, cassava vein mosaic virus promoter, Agrobacterium rhizogenes rolD gene, and nopaline synthase (NOS) (Karimi et al., 2007). Several Arabidopsis promoters have also been used for heterologous gene expression, including the ubiquitin 10 promoter (Grefen et al., 2010), actin 2 promoter (Klahre and Chua, 1999), and tubulin promoter (Carpenter et al., 1992). Similarly, the terminators of octopine synthase, CaMV, TG7, NOS, ubiquitin 10, actin 2, and tubulin have also been used for gene overexpression in plants. Antibiotics such as kanamycin, hygromycin, gentamycin, and basta are also commonly used for the selection of positive transformants in plant cell cultures (Angenon et al., 1994). Because the use of single promoters can result in gene silencing, the ability to overexpress multiple genes at a time is an approach that has been used to produce more effective multigene transformations using different promoter and terminator pairs (Karimi et al., 2007). Apart from native promoters, many synthetic promoters have been investigated and implemented in transgenic plants (Ali and Kim, 2019). Synthetic promoters have the advantage of shrinking (simplifying) the operon size and helping to resolve one bottleneck in multiple pathway expression in plants. For example, Peramuna et al. (2018) created three synthetic promoters through the rational combination of different cis-regulatory elements (CREs) and tested them in moss cells, ultimately achieving expression levels similar to those obtained with the native Arabidopsis promoter AtUBQ10. More synthetic promoters tested in plants are reviewed by Liu and Stewart (2016). We still have the option to design de novo promoters, and an online tutorial describes how to build and regulate a promoter: http://parts.igem.org/Promoters/Design.

Heterologous pathway implementation in plant cell cultures

Although the expression of multiple heterologous proteins and the establishment of new biosynthetic pathways in plant cell cultures is still considered to be more expensive and difficult than expressing a single protein, plant cell cultures are increasingly being used to produce heterologous proteins and vaccines. Such advances in the field have recently been summarized by Guerriero et al. (2018). Some exciting discoveries that highlight the power of plant cell cultures to produce secondary metabolites include the metabolic engineering of tobacco to produce artemisinin at a level of 0.48–6.8 μg/g dry weight, which was achieved using transgenic plants with five mevalonate and artemisinin pathway genes expressed from a single vector (Farhi et al., 2011). Similarly, the expression of amorpha-4,11-diene synthase, amorphadiene monooxygenase, aldehyde Δ (13) reductase, and aldehyde dehydrogenase in N. tabacum leaf cells was shown to produce 0.01 mg/g dry weight of artemisinic alcohol (Zhang et al., 2011). In addition, Malhotra et al. (2016) transferred six genes from the mevalonate pathway to N. tabacum chloroplasts and genes from the artemisinin pathway to the nuclear genome, thereby generating transgenic plants that were able to produce approximately 0.8 mg/g dry weight of artemisinin. In a similar study, Ikram and Simonsen (2017) transferred all five genes of artemisinin biosynthesis into P. patens, producing 0.21 mg/g dry weight of artemisinin within 3 days of culture. They further investigated the accumulation of the important intermediate amorpha-4,11-diene and a second product, arteannuin B, via the same pathway (Ikram et al., 2019). In addition, Simonsen et al. (2018) have produced patchoulol, β-santalene, and sclareol via heterologous expression in P. patens. However, production of the artemisinin precursors artemisinic and dihydroartemisinic acid in plants remains challenging owing to internal glycosylation and insufficient oxidation of such acids. Although the use of Escherichia coli and S. cerevisiae has allowed the production of high concentrations of amorpha-4,11-diene and artemisinic acid, such systems are currently not able to produce active artemisinin (Farhi et al., 2011). Another example in which plant cell cultures have proven more advantageous than their microbial counterparts is the transformation of Silybum marianum (L.) Gaertn to produce resveratrol. Cell suspension cultures containing Vitis vinifera L. stilbene synthase led to increased accumulation of t-resveratrol (Hidalgo et al., 2017). In addition, enhanced expression of taxadiene synthase (TAS) in Taxus chinensis cell suspension cultures via overexpression of neutral/alkaline invertase (NINV) significantly increased the biosynthesis of seven individual taxanes (Dong et al., 2015; Kowalczyk et al., 2020).

Gene editing tools for plant cell culture

Gene engineering in plants is usually achieved by modifying the genome of cultured cells and then regenerating whole plants by exposing the modified cells to growth hormones (Baumann, 2020). This protocol has been improved by Maher et al. (2020). First, the authors developed a high-throughput platform to generate de novo meristems on the leaves of Nicotiana benthamiana seedlings grown in vitro by expressing the developmental regulators Wus2 and STM using Agrobacterium-mediated transient transformation. This transient expression leads to the formation of callus-like growths on the tissues of interest. Even though many calli remain undifferentiated, some form meristem-like structures that then differentiate into small shoots that can be transferred to rooting medium and ultimately to soil, thereby obtaining fully mature plants that are capable of reproduction (Baumann, 2020). Using a similar method on tomato seedlings, transient expression of Wus2, IPT, and STM has also been shown to regenerate whole tomato plants (Maher et al., 2020).

Plant cell suspensions do not need to differentiate into different organs but do require high gene transfer efficiency and rapid genome assembly. For instance, researchers have successfully introduced heterologous genes into plant protoplasts via Ti plasmids for decades (Krens et al., 1982). However, the introduction of multiple genes via multigene operons using Ti plasmids remains challenging because of the limited efficiency of restriction enzyme cloning (Shi et al., 2017). Despite such challenges, Ti plasmids, which originate from the soil-borne bacterium A. tumefaciens, are still the most promising vector for genetic engineering in plants (Dehkordi et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2020a; Mohan et al., 2020). Given that Ti plasmids are considerably longer than other vectors (vectors 15–30 kb are most common in prokaryotes), researchers need more efficient methods for engineering genes. With the development of gene editing tools in eukaryotes, plasmids under 20 kb can now be assembled in a matter of days (Gibson et al., 2008; Kuijpers et al., 2013). This assembly can also take place in plant cells, and this process has been investigated as a de novo method (King et al., 2016) (Figure 3). In addition, vector-free genetic transformation of P. patens has been achieved, enabling the introduction of heterologous genes via homologous recombination (Schaefer and Zrÿd, 1997). A recent report has documented the cellulase- and macerozyme-PEG-mediated transformation of P. patens (Batth et al., 2021). With this inspiration, it will be worth trying in other Bryophyte or haploid plant cells, thereby shortening the gene editing process.

Figure 3.

Homologous recombination provides an efficient way to build large vectors.

Multi-fragment cloning is no longer difficult. The diagram shows an example of homologous recombination in S. cerevisiae to build a vector containing six genes in one step. R1–7 indicate seven different homologous regions with over 60 bp. P and T represent the promoter and terminator. Recent research indicates the method enabled more than 30 fragments of ligase (Shih et al., 2016; Vashee et al., 2020).

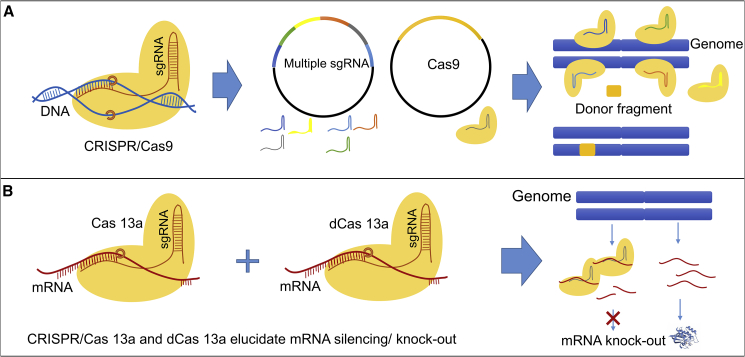

More recently, CRISPR/Cas and its variants are being increasingly used to elucidate the roles of individual genes(s) and their regulatory elements in plants (Arya et al., 2020). CRISPR/Cas9 targeted mutagenesis has been widely used to edit genes (and gene families) in order to understand how biosynthetic pathways are regulated and thus facilitate crop improvement (Che et al., 2018; Cox et al., 2017). Nuclease-dead Cas molecules (dCas9 and dCas12a) offer a platform for the precise control of genome function without gene editing (Xu and Qi, 2019). Application schemes of CRISPR/Cas9 are shown in Figure 4A. Given that some countries remain conservative in their approach to genetic modification, cell suspension cultures may prove more acceptable than the growth of engineered crop plants in the field.

Figure 4.

Examples of CRISPR/Cas gene editing for DNA and RNA.

(A) CRISPR/Cas enables the knock in of genes or promoter exchanges.

(B) CRISPR/Cas13a for RNA silencing.

Genetic circuit design in plant cell culture

Plant cells, as higher eukaryotes, have massive internal metabolite networks. The adjustment of fluxes from one pathway to another is a foreseeable method for optimizing the cell culture platform. In addition, the microbe platform foreshadows this emerging field (Patron, 2020; Guha et al., 2017). Some of the usable genetic circuit designs are listed below. Synthetic sensors are self-regulating systems that are widely used in microbes (Meyer et al., 2019). Genetic sensors allow cells to receive environmental as well as internal cell homeostasis information. Several genomic switches have been implemented in eukaryotes, serving as flux sensors in specific pathways and indicating the concentrations of different cellular metabolites (Chen et al., 2020; Havens et al., 2012). More mature circuit components can be found at the International Genetically Engineered Machine registry (IGEM; http://parts.igem.org/Collections/Plants). Different genomic switches can work as orthogonal components, eventually forming a genetic circuit to obtain AND, OR, NOT-AND, and NOR Boolean logic gates (Andres et al., 2019). With the implementation of genetic circuits, one can develop “smart” plants that are able to actively respond to changing conditions. One potential application of smart plants is the ability of plants to sense environmental stimuli and implement a response, such that plant growth and development are maintained. In plant cell cultures, sensors for drought (pSpark), temperature (pCBF), and plant maturity (pSAG12) have been generated, which confer higher efficiency of carbon fixation and sugar generation (Brophy and Voigt, 2014).

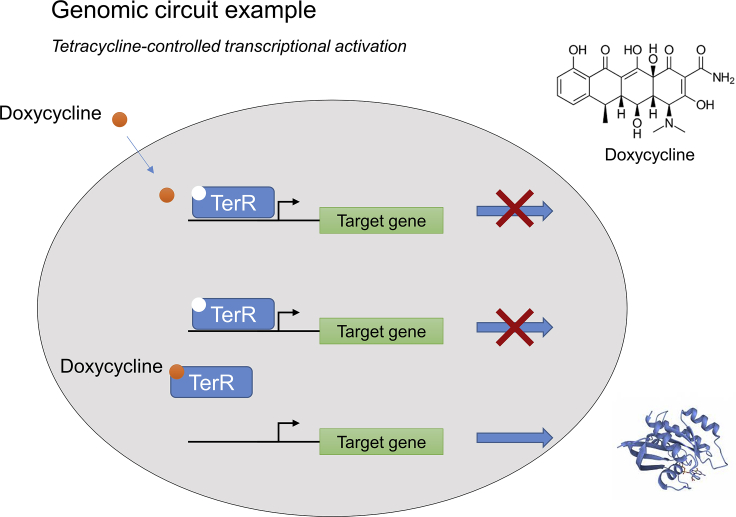

As the key components used to build a multi-stage system, a range of sensors and switches have been developed and are summarized in Pouvreau et al. (2018) and Kassaw et al. (2018). Promising switches that have been implemented in plant cells include inducible switches such as the lac operator and TetR/tetO (Figure 5), Cas-based switches, and light-driven switches (Andres et al., 2019). Furthermore, positive and negative regulatory configurations can be achieved through fusion of a transactivator or transrepressor to TetR or modification of the synthetic promoter region (Kramer et al., 2004; Hörner and Weber, 2012).

Figure 5.

Working mechanism of the Tet repressor.

TetR is a repressor that can bind to a specific promoter region (tetO) and repress the expression of the target gene. Tetracycline serves as an inducer for the release of TetR from the region. The repression model indicates the basic principle of inducer switches.

All switches should work orthogonally to one another in the cell. Plant transcriptional regulation involves complex combinations of negative and/or positive regulators that engage in feedback loops and Boolean logic gate computing mechanisms (Bateman, 1998; Savageau, 1974; Sorrells and Johnson, 2015). As plant regulatory systems are inherently more complex than their prokaryotic counterparts, researchers have turned to the characterization of simple prokaryotic regulatory elements as a starting platform to enable the engineering of artificial, exogenously controlled gene expression systems in both prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells (Lebar et al., 2014; Ajo-Franklin et al., 2007). For example, the tetracycline-regulated gene (tetA) was one of the first inducible gene switches found in E. coli, and it controls tetracycline resistance (Beck et al., 1982). Other inducible gene switches developed in yeast and animal cells have the ability to sense antibiotics, metabolites, and volatiles. For example, antibiotics such as tetracycline (Gossen et al., 1995), isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) (Hansen et al., 1998), copper (McKenzie et al., 1998), macrolides and pristinamycin (Frey et al., 2001), and ethanol (Roslan et al., 2001) have all been used to trigger genetic switches. In plants, steroid-based systems are still the most widely used, as they allow precise temporal control over cellular processes (Schena et al., 1991). More recently, Cas9-based repressors and regulatory modules of hormone signaling pathways (HACRs; involved in auxin, GA, and jasmonate signaling) have been implemented in Arabidopsis (Khakhar et al., 2018). HACRs have the ability to sense both exogenous hormone treatments and endogenous hormone levels and result in degradation of the switch, which in turn regulates target gene expression (Figure 4B). This tool can be applied to other hormones or any target of interest, allowing the manipulation of stress tolerance and even yield in crop plants. With the exception of chemical gene switches, light-controlled genetically encoded molecular devices have also been engineered and implemented in living cells, giving rise to the nascent field of optogenetics (Andres et al., 2019).

While transcriptional gene switches currently play a major role in customized gene expression and are used for a broad range of applications, synthetic RNA-based switches constitute a complementary approach for controlling gene expression at the translational level. In plants, specific RNA-based gene silencing using artificial antisense mRNAs or microRNAs has been widely used for more than 20 years (Abudayyeh et al., 2017; Masclaux et al., 2004). Although such systems can be controlled using tissue-specific or inducible promoters, RNA-based gene silencing usually suffers from off-target effects, provides limited exogenous and quantitative control, and is less efficient overall compared with alternative methods (Carbonell et al., 2014). Other examples of translational control of gene expression in plants are limited to applications in plastids (Verhounig et al., 2010). Faden et al. (2016) reported a post-transcriptional switch for the downregulation of proteins based on a temperature-controlled N-terminal degradation signal in planta.

With the exception of switches, gene regulation also involves the overexpression or downregulation of metabolic pathways by diverting common precursors, enzymes, or regulatory proteins with the help of recombinant DNA technology (Chandran et al., 2020). By understanding the pathways for the biosynthesis of complex metabolites in plant cells, such metabolites can be reconstituted within plants or heterologous hosts for overproduction and isolation of economically important plant metabolites (Chandran et al., 2020).

Flux balance analysis in plant cell culture

Flux balance analysis (FBA) is a mathematical method for simulating metabolism in genome-scale reconstructions of metabolic networks. FBA finds applications in bioprocess engineering to systematically identify modifications to metabolic networks of microbes used in fermentation processes that improve the product yields of chemicals (Orth et al., 2010). Determination of biomass composition is crucial to the use of FBA metabolic models for predicting flux distribution. Given that intracellular fluxes are based on biomass synthesis fluxes (Pramanik and Keasling, 1997; Schwender and Hay, 2012), it is important to define the biomass composition during the development of large-scale metabolic models, ideally for the conditions under study. Experimental evidence shows that biomass composition varies between species, cell types, and physiological conditions (Hay and Schwender, 2011; Novak and Loubiere, 2000). However, the biomass compositions used in plant large-scale metabolic models are often collected from diverse measurement types, experiments, research groups, and even cell types and plant species (Collakova et al., 2012) because organism-specific and/or condition-specific experimental information is lacking. Recent research on the characteristics of published Arabidopsis metabolic models concentrated on three particular models with distinct model structures and biomass component compositions (Yuan et al., 2016). Three Arabidopsis models were used to investigate variability in biomass composition and structure of models from the same species. Central metabolic fluxes and growth rates were insensitive to variations in biomass composition but were significantly affected by model structure. This work represents a thorough set of analyses performed in plants by constraint-based modeling, providing relevant information on how critical FBA solutions can be affected by biomass composition and, more importantly, model structure. Despite differences in several aspects, such as model structure and the numbers of metabolites and reactions included, each of the evaluated models has its own merits. Comparative analysis of the models paves the way for exploring the existence of principles that are relevant to the regulation and robustness of plant central carbon metabolism. Although it is highly informative and not as laborious as the initial plant genome scale metabolic models (GEMs), this approach still requires genome sequence information in order to assemble the required stoichiometric models. Furthermore, it has not yet been used extensively for secondary metabolites. However, other useful innovations of this approach include growth-by-osmotic-expansion (GrOE) FBA, a framework developed for tomato cells that accounts for both metabolic and ionic contributions to the osmosis that drives cell expansion (Shameer et al., 2020). It seems likely that this approach will inform synthetic biology approaches in cell culture in the future.

Perspective

In this review, we highlight the use of model plant cell cultures as cell factories to produce valuable secondary metabolites. Although this technology has great potential in pharmaceutical, cosmeceutical, and nutraceutical applications, some specific challenges still need to be overcome, including epigenetic silencing, altered enzyme activity, production inhibition, and toxic intermediates. Co-expression of the P19 virus protein could greatly decrease gene silencing. Substrate channeling (also known as metabolon formation) involves non-covalently bound complexes that come together in a transient fashion to enable the regulation of metabolic pathway flux by dynamic assembly, and several metabolic advantages of metabolons have been postulated. These include increased catalytic efficiency, local substrate enrichment, protection of the cell from cytotoxic intermediates, prevention of decomposition of unstable compounds, overcoming of thermodynamically unfavorable equilibrium, and avoidance of competing pathways (Zhang et al., 2017, 2020b; Zhang and Fernie, 2020a). Thus, investigating the substrate channeling of biosynthetic pathways would be useful for engineering full pathways in heterologous cell culture hosts to avoid toxic intermediates and production inhibition (Zhang and Fernie, 2020b). In addition, specific product transporters could also be introduced, which would also simplify metabolite extraction. Moreover, FBA provides us with a thorough set of plant central carbon metabolism analyses performed by means of constraint-based modeling and theory for optimizing secondary metabolite production pathways in the future.

In the last two decades, since the foundational publications on synthetic devices, synthetic biology has evolved into a mature discipline that has already revolutionized research, biomedicine, and the biotechnology industry. A broad range of synthetic molecular tools, regulatory and metabolic circuitry, and even synthetic organelles and genomes have been engineered and successfully applied in bacterial, yeast, and animal systems (Brophy and Voigt, 2014). As described in this article, several synthetic biosensors and switches for the control of gene expression (including several optogenetic modules), genome editing, and protein stability have already been implemented in plants. In particular, overexpression of multiple genes and genome editing systems in Arabidopsis and N. tabacum cell culture could provide valuable commercial platforms for the biosynthesis of valuable metabolites.

To accelerate industrial production, researchers must optimize methods both in vivo and in silico. It is the development and implementation of artificial neural networks that provide us with insight into the significant factors that influence multifactorial processes (García-Pérez et al., 2020).

Through the implementation of heterologous pathways with overlapping and increasingly precise regulatory systems (for example, ethanol-inducible switches that force precursor flux in the desired direction combined with light-dependent switches that enable orthogonal gene expression during the day), plant cell cultures display huge potential for the production of economically important secondary metabolites at commercial scales.

Funding

This work was supported by funding from the Max Planck Society (Y.Z., T.W., and A.R.F.). A.R.F. and Y.Z. would like to thank the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation program, project PlantaSYST (SGA-CSA no. 664621 and no. 739582 under FPA no. 664620), for supporting their research. T.W. would like to thank the China Scholarship Council (CSC) scholarship for supporting his study. S.M.K. would like to thank the Leibniz Institute für Gemüse- und Zierpflanzenbau (IGZ) as part of the Leibniz Association.

Author contributions

T.W. and Y.Z. wrote the manuscript. Y.Z., A.R.F., and S.M.K. revised the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Bar-Even group and Yuan Zhou at the Max Planck Institute of Molecular Plant Physiology for help with photography. The authors declare no competing interests.

Published: August 23, 2021

Footnotes

Published by the Plant Communications Shanghai Editorial Office in association with Cell Press, an imprint of Elsevier Inc., on behalf of CSPB and CEMPS, CAS.

References

- Abudayyeh O.O., Gootenberg J.S., Essletzbichler P., Han S., Joung J., Belanto J.J., Verdine V., Cox D.B.T., Kellner M.J., Regev A. RNA targeting with CRISPR–Cas13. Nature. 2017;550:280–284. doi: 10.1038/nature24049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ajo-Franklin C.M., Drubin D.A., Eskin J.A., Gee E.P.S., Landgraf D., Phillips I., Silver P.A. Rational design of memory in eukaryotic cells. Genes Dev. 2007;21:2271–2276. doi: 10.1101/gad.1586107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali S., Kim W.-C. A fruitful decade using synthetic promoters in the improvement of transgenic plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2019;10:1433. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2019.01433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andres J., Blomeier T., Zurbriggen M.D. Synthetic switches and regulatory circuits in plants. Plant Physiol. 2019;179:862–884. doi: 10.1104/pp.18.01362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angenon G., Dillen W., Van Montagu M. In: Plant Molecular Biology Manual. Gelvin Stanton B., Schilperoort Robbert A., editors. Springer; Dordrecht: 1994. Antibiotic resistance markers for plant transformation; pp. 125–137. [Google Scholar]

- Antonio C., Mustafa N.R., Osorio S., Tohge T., Giavalisco P., Willmitzer L., Rischer H., Oksman-Caldentey K.-M., Verpoorte R., Fernie A.R. Analysis of the interface between primary and secondary metabolism in Catharanthus roseus cell cultures using 13C-stable isotope feeding and coupled mass spectrometry. Mol. Plant. 2013;6:581–584. doi: 10.1093/mp/sss156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appelhagen I., Wulff-Vester A.K., Wendell M., Hvoslef-Eide A.-K., Russell J., Oertel A., Martens S., Mock H.-P., Martin C., Matros A. Colour bio-factories: towards scale-up production of anthocyanins in plant cell cultures. Metab. Eng. 2018;48:218–232. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2018.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arya S.S., Rookes J.E., Cahill D.M., Lenka S.K. Next-generation metabolic engineering approaches towards development of plant cell suspension cultures as specialized metabolite producing biofactories. Biotechnol. Adv. 2020;45:107635. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2020.107635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbulova A., Apone F., Colucci G. Plant cell cultures as source of cosmetic. Active Ingredients. 2014;1:94–104. [Google Scholar]

- Barbulova A., Colucci G., Apone F. New trends in cosmetics: by-products of plant origin and their potential use as cosmetic. Active Ingredients. 2015;2:82–92. [Google Scholar]

- Bateman E. Autoregulation of eukaryotic transcription factors. Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol. 1998;60:133–168. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)60892-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batth R., Cuciurean I.S., Kodiripaka S.K., Rothman S.S., Greisen C., Simonsen H.T. Cellulase and macerozyme-PEG-mediated transformation of moss protoplasts. Bio Protoc. 2021;11:e3782. doi: 10.21769/BioProtoc.3782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann K. Plant gene editing improved. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2020;21:66. doi: 10.1038/s41580-019-0207-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck C.F., Mutzel R., Barbe J., Müller W. A multifunctional gene (tetR) controls Tn10-encoded tetracycline resistance. J. Bacteriol. 1982;150:633–642. doi: 10.1128/jb.150.2.633-642.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brophy J.A., Voigt C.A. Principles of genetic circuit design. Nat. Methods. 2014;11:508–520. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Büttner-Mainik A., Parsons J., Jérôme H., Hartmann A., Lamer S., Schaaf A., Schlosser A., Zipfel P.F., Reski R., Decker E.L. Production of biologically active recombinant human factor H in Physcomitrella. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2011;9:373–383. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2010.00552.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carbonell A., Takeda A., Fahlgren N., Johnson S.C., Cuperus J.T., Carrington J.C. New generation of artificial MicroRNA and synthetic trans-acting small interfering RNA vectors for efficient gene silencing in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2014;165:15–29. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.234989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter J.L., Ploense S.E., Snustad D.P., Silflow C.D. Preferential expression of an alpha-tubulin gene of Arabidopsis in pollen. Plant Cell. 1992;4:557–571. doi: 10.1105/tpc.4.5.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandran H., Meena M., Barupal T., Sharma K. Plant tissue culture as a perpetual source for production of industrially important bioactive compounds. Biotechnol. Rep. 2020;26:e00450. doi: 10.1016/j.btre.2020.e00450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhary S., Chikara S.K., Sharma M.C., Chaudhary A., Alam Syed B., Chaudhary P.S., Mehta A., Patel M., Ghosh A., Iriti M. Elicitation of diosgenin production in Trigonella foenum-graecum (fenugreek) seedlings by methyl jasmonate. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015;16:29889–29899. doi: 10.3390/ijms161226208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Che P., Anand A., Wu E., Sander J.D., Simon M.K., Zhu W., Sigmund A.L., Zastrow-Hayes G., Miller M., Liu D. Developing a flexible, high-efficiency Agrobacterium-mediated sorghum transformation system with broad application. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2018;16:1388–1395. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chee M.J.Y., Lycett G.W., Khoo T.-J., Chin C.F. Bioengineering of the plant culture of capsicum frutescens with vanillin synthase gene for the production of vanillin. Mol. Biotechnol. 2017;59:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s12033-016-9986-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Zhang S., Young E.M., Jones T.S., Densmore D., Voigt C.A. Genetic circuit design automation for yeast. Nat. Microbiol. 2020;5:1349–1360. doi: 10.1038/s41564-020-0757-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng M., Lowe B.A., Spencer T.M., Ye X., Armstrong C. Factors influencing Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of monocotyledonous species. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2004;40:31–45. [Google Scholar]

- Collakova E., Yen J.Y., Senger R.S.J. Are we ready for genome-scale modeling in plants? Plant Sci. 2012;191:53–70. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2012.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correa S.M., Alseekh S., Atehortúa L., Brotman Y., Ríos-Estepa R., Fernie A.R., Nikoloski Z. Model-assisted identification of metabolic engineering strategies for Jatropha curcas lipid pathways. Plant J. 2020;104:76–95. doi: 10.1111/tpj.14906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox D.B.T., Gootenberg J.S., Abudayyeh O.O., Franklin B., Kellner M.J., Joung J., Zhang F. RNA editing with CRISPR-Cas13. Science. 2017;358:1019–1027. doi: 10.1126/science.aaq0180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehkordi E.A., Alemzadeh A., Tanaka N. Plant Cell Biotechnology and Molecular Biology. 1st–2nd. Vol. 19. International Knowledge Press; India: 2018. Agrobacterium-MEDIATED Transformation OF Ovary OF BREAD Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) with A Gene Encoding A TOMATO ERF PROTEIN; pp. 24–33. [Google Scholar]

- Dong Y., Duan W., He H., Su P., Zhang M., Song G., Fu C., Yu L.J.P. Enhancing taxane biosynthesis in cell suspension culture of Taxus chinensis by overexpressing the neutral/alkaline invertase gene. Process Biochem. 2015;50:651–660. [Google Scholar]

- Dunwell J.M. In: Transgenic Wheat, Barley and Oats: Production and Characterization Protocols. Jones H.D., Shewry P.R., editors. Humana Press; Totowa, NJ: 2009. Transgenic wheat, barley and oats: future prospects; pp. 333–345. [Google Scholar]

- Efferth T.J.E. Biotechnology applications of plant callus cultures. Engineering. 2019;5:50–59. [Google Scholar]

- Eibl R., Meier P., Stutz I., Schildberger D., Hühn T., Eibl D. Plant cell culture technology in the cosmetics and food industries: current state and future trends. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018;102:8661–8675. doi: 10.1007/s00253-018-9279-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espinosa-Leal C.A., Puente-Garza C.A., García-Lara S. In vitro plant tissue culture: means for production of biological active compounds. Planta. 2018;248:1–18. doi: 10.1007/s00425-018-2910-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faden F., Ramezani T., Mielke S., Almudi I., Nairz K., Froehlich M.S., Höckendorff J., Brandt W., Hoehenwarter W., Dohmen R.J. Phenotypes on demand via switchable target protein degradation in multicellular organisms. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:12202. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farhi M., Marhevka E., Ben-Ari J., Algamas-Dimantov A., Liang Z., Zeevi V., Edelbaum O., Spitzer-Rimon B., Abeliovich H., Schwartz B.J. Generation of the potent anti-malarial drug artemisinin in tobacco. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011;29:1072–1074. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey A.D., Rimann M., Bailey J.E., Kallio P.T., Thompson C.J., Fussenegger M.J. Novel pristinamycin-responsive expression systems for plant cells. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2001;74:154–163. doi: 10.1002/bit.1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita Y., Hara Y., Suga C., Morimoto T. Production of shikonin derivatives by cell suspension cultures of Lithospermum erythrorhizon. Plant Cell Rep. 1981;1:61–63. doi: 10.1007/BF00269273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Pérez P., Lozano-Milo E., Landín M., Gallego P.P. Combining medicinal plant in vitro culture with machine learning technologies for maximizing the production of phenolic compounds. Antioxidants (Basel) 2020;9:210. doi: 10.3390/antiox9030210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgiev V. Mass propagation of plant cells–an emerging technology platform for sustainable production of biopharmaceuticals. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2015;4:e180. [Google Scholar]

- Georgiev V., Slavov A., Vasileva I., Pavlov A.J. Plant cell culture as emerging technology for production of active cosmetic ingredients. Eng. Life Sci. 2018;18:779–798. doi: 10.1002/elsc.201800066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson D.G., Benders G.A., Axelrod K.C., Zaveri J., Algire M.A., Moodie M., Montague M.G., Venter J.C., Smith H.O., Hutchison C.A. One-step assembly in yeast of 25 overlapping DNA fragments to form a complete synthetic Mycoplasma genitaliumgenome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2008;105:20404–20409. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811011106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gossen M., Freundlieb S., Bender G., Muller G., Hillen W., Bujard H. Transcriptional activation by tetracyclines in mammalian cells. Science. 1995;268:1766. doi: 10.1126/science.7792603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grefen C., Donald N., Hashimoto K., Kudla J., Schumacher K., Blatt M.R. A ubiquitin-10 promoter-based vector set for fluorescent protein tagging facilitates temporal stability and native protein distribution in transient and stable expression studies. Plant J. 2010;64:355–365. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04322.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerriero G., Berni R., Muñoz-Sanchez J.A., Apone F., Abdel-Salam E.M., Qahtan A.A., Alatar A.A., Cantini C., Cai G., Hausman J.-F. Production of plant secondary metabolites: examples, tips and suggestions for biotechnologists. Genes (Basal) 2018;9:309. doi: 10.3390/genes9060309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guha T.K., Wai A., Hausner G. Programmable genome editing tools and their regulation for efficient genome engineering. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2017;15:146–160. doi: 10.1016/j.csbj.2016.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen L.H., Knudsen S., Sørensen S.J. The effect of the lacY gene on the induction of IPTG inducible promoters, studied in Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas fluorescens. Curr. Microbiol. 1998;36:341–347. doi: 10.1007/s002849900320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havens K.A., Guseman J.M., Jang S.S., Pierre-Jerome E., Bolten N., Klavins E., Nemhauser J.L. A synthetic approach reveals extensive tunability of auxin signaling. Plant Physiol. 2012;160:135–142. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.202184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay J., Schwender J.J.T. Metabolic network reconstruction and flux variability analysis of storage synthesis in developing oilseed rape (Brassica napus L.) embryos. Plant J. 2011;67:526–541. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04613.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellwig S., Drossard J., Twyman R.M., Fischer R. Plant cell cultures for the production of recombinant proteins. Nat. Biotechnol. 2004;22:1415–1422. doi: 10.1038/nbt1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo D., Martínez-Márquez A., Cusidó R., Bru-Martínez R., Palazón J., Corchete P.J. Silybum marianum cell cultures stably transformed with Vitis vinifera stilbene synthase accumulate t-resveratrol in the extracellular medium after elicitation with methyl jasmonate or methylated β-cyclodextrins. Eng. Life Sci. 2017;17:686–694. doi: 10.1002/elsc.201600241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hörner M., Weber W. Molecular switches in animal cells. FEBS Lett. 2012;586:2084–2096. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikram N.K., Simonsen H.T. A review of biotechnological artemisinin production in plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2017;8:1966. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.01966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikram N.K.B., Zhan X., Pan X.-W., King B.C., Simonsen H.T. Stable heterologous expression of biologically active terpenoids in green plant cells. Front. Plant Sci. 2015;6:129. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.00129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikram N.K.K., Kashkooli A.B., Peramuna A., Krol A.R.V., Bouwmeester H., Simonsen H.T. Insights into heterologous biosynthesis of arteannuin b and artemisinin in Physcomitrella patens. Molecules. 2019;24:3822. doi: 10.3390/molecules24213822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong Y.J., An C.H., Woo S.G., Park J.H., Lee K.-W., Lee S.-H., Rim Y., Jeong H.J., Ryu Y.B., Kim C.Y. Enhanced production of resveratrol derivatives in tobacco plants by improving the metabolic flux of intermediates in the phenylpropanoid pathway. Plant Mol. Biol. 2016;92:117–129. doi: 10.1007/s11103-016-0497-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones H.D., Doherty A., Wu H. Review of methodologies and a protocol for the Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of wheat. Plant Methods. 2005;1:5. doi: 10.1186/1746-4811-1-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karimi M., Bleys A., Vanderhaeghen R., Hilson P. Building blocks for plant gene assembly. Plant Physiol. 2007;145:1183–1191. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.110411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassaw T.K., Donayre-Torres A.J., Antunes M.S., Morey K.J., Medford J.I. Engineering synthetic regulatory circuits in plants. Plant Sci. 2018;273:13–22. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2018.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khakhar A., Leydon A.R., Lemmex A.C., Klavins E., Nemhauser J.L. Synthetic hormone-responsive transcription factors can monitor and re-program plant development. eLife. 2018;7:e34702. doi: 10.7554/eLife.34702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kieran P.M., MacLoughlin P.F., Malone D.M. Plant cell suspension cultures: some engineering considerations. J. Biotechnol. 1997;59:39–52. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1656(97)00163-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King B.C., Vavitsas K., Ikram N.K.B., Schrøder J., Scharff L.B., Bassard J.-É., Hamberger B., Jensen P.E., Simonsen H.T. In vivo assembly of DNA-fragments in the moss, Physcomitrella patens. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:25030. doi: 10.1038/srep25030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kizhner T., Azulay Y., Hainrichson M., Tekoah Y., Arvatz G., Shulman A., Ruderfer I., Aviezer D., Shaaltiel Y. Characterization of a chemically modified plant cell culture expressed human α-galactosidase-A enzyme for treatment of Fabry disease. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2015;114:259–267. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2014.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klahre U., Chua N.-H. The Arabidopsis ACTIN-RELATED PROTEIN 2 (AtARP2) promoter directs expression in xylem precursor cells and pollen. Plant Mol. Biol. 1999;41:65–73. doi: 10.1023/a:1006247600932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowalczyk T., Wieczfinska J., Skała E., Śliwiński T., Sitarek P. Transgenesis as a tool for the efficient production of selected secondary metabolites from in vitro plant cultures. Plants (Basel) 2020;9:132. doi: 10.3390/plants9020132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer B.P., Fischer C., Fussenegger M.J. BioLogic gates enable logical transcription control in mammalian cells. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2004;87:478–484. doi: 10.1002/bit.20142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krens F.A., Molendijk L., Wullems G.J., Schilperoort R.A. In vitro transformation of plant protoplasts with Ti-plasmid DNA. Nature. 1982;296:72–74. [Google Scholar]

- Kuijpers N.G.A., Solis-Escalante D., Bosman L., van den Broek M., Pronk J.T., Daran J.-M., Daran-Lapujade P. A versatile, efficient strategy for assembly of multi-fragment expression vectors in Saccharomyces cerevisiae using 60 bp synthetic recombination sequences. Microb. Cell Fact. 2013;12:47. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-12-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwiatkowska A., Zebrowski J., Oklejewicz B., Czarnik J., Halibart-Puzio J., Wnuk M. The age-dependent epigenetic and physiological changes in an Arabidopsis T87 cell suspension culture during long-term cultivation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2014;447:285–291. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.03.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange B.M. In: Biotechnology of Natural Products. Schwab W., Lange B.M., Wüst M., editors. Springer International Publishing; Cham: 2018. Commercial-scale tissue culture for the production of plant natural products: successes, failures and outlook; pp. 189–218. [Google Scholar]

- Lebar T., Majerle A., Šter B., Dobnikar A., Benčina M., Jerala R.J.N. Designable DNA-binding domains enable construction of logic circuits in mammalian cells. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2014;10:203. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B., Takahashi D., Kawamura Y., Uemura M. Plasma membrane proteome analyses of Arabidopsis thaliana suspension-cultured cells during cold or ABA treatment: relationship with freezing tolerance and growth phase. J. Proteomics. 2020;211:103528. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2019.103528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W., Stewart C.N., Jr. Plant synthetic promoters and transcription factors. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2016;37:36–44. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2015.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maher M.F., Nasti R.A., Vollbrecht M., Starker C.G., Clark M.D., Voytas D.F. Plant gene editing through de novo induction of meristems. Nat. Biotechnol. 2020;38:84–89. doi: 10.1038/s41587-019-0337-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra K., Subramaniyan M., Rawat K., Kalamuddin M., Qureshi M.I., Malhotra P., Mohmmed A., Cornish K., Daniell H., Kumar S.J. Compartmentalized metabolic engineering for artemisinin biosynthesis and effective malaria treatment by oral delivery of plant cells. Mol. Plant. 2016;9:1464–1477. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2016.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masclaux F., Charpenteau M., Takahashi T., Pont-Lezica R., Galaud J.-P. Gene silencing using a heat-inducible RNAi system in Arabidopsis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004;321:364–369. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.06.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie M.J., Mett V., Reynolds P.H.S., Jameson P.E. Controlled cytokinin production in transgenic tobacco using a copper-inducible promoter. Plant Physiol. 1998;116:969–977. doi: 10.1104/pp.116.3.969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menges M., Murray J.A. Cryopreservation of transformed and wild-type Arabidopsis and tobacco cell suspension cultures. Plant J. 2004;37:635–644. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2003.01980.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer A.J., Segall-Shapiro T.H., Glassey E., Zhang J., Voigt C.A. Escherichia coli “Marionette” strains with 12 highly optimized small-molecule sensors. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2019;15:196–204. doi: 10.1038/s41589-018-0168-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohan C., Ashwin Narayan J., Esterling M., Yau Y.-Y. In: Climate Change, Photosynthesis and Advanced Biofuels: The Role of Biotechnology in the Production of Value-Added Plant Bio-Products. Kumar A., Yau Y.-Y., Ogita S., Scheibe R., editors. Springer Singapore; Singapore: 2020. Current transformation methods for genome-editing applications in energy crop sugarcane; pp. 369–388. [Google Scholar]

- Nagata T., Nemoto Y., Hasezawa S. In: International Review of Cytology. Jeon K.W., Friedlander M., editors. Academic Press; Japan: 1992. Tobacco BY-2 cell line as the “HeLa” cell in the cell biology of higher plants; pp. 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Novak L., Loubiere P.J. The metabolic network of Lactococcus lactis: distribution of 14C-labeled substrates between catabolic and anabolic pathways. J. Bacteriol. 2000;182:1136–1143. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.4.1136-1143.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orth J.D., Thiele I., Palsson B.Ø. What is flux balance analysis? Nat. Biotechnol. 2010;28:245–248. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parthasarathy R., Shanmuganathan R., Pugazhendhi A. Vinblastine production by the endophytic fungus Curvularia verruculosa from the leaves of Catharanthus roseus and its in vitro cytotoxicity against HeLa cell line. Anal. Biochem. 2020;593:113530. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2019.113530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patron N.J. Beyond natural: synthetic expansions of botanical form and function. New Phytol. 2020;227:295–310. doi: 10.1111/nph.16562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peramuna A., Bae H., Rasmussen E.K., Dueholm B., Waibel T., Critchley J.H., Brzezek K., Roberts M., Simonsen H.T. Evaluation of synthetic promoters in Physcomitrella patens. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2018;500:418–422. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.04.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pouvreau B., Vanhercke T., Singh S. From plant metabolic engineering to plant synthetic biology: the evolution of the design/build/test/learn cycle. Plant Sci. 2018;273:3–12. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2018.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pramanik J., Keasling J.J. Stoichiometric model of Escherichia coli metabolism: incorporation of growth-rate dependent biomass composition and mechanistic energy requirements. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 1997;56:398–421. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0290(19971120)56:4<398::AID-BIT6>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pucker B., Rückert C., Stracke R., Viehöver P., Kalinowski J., Weisshaar B. Twenty-five years of propagation in suspension cell culture results in substantial alterations of the Arabidopsis thaliana genome. Genes (Basel) 2019;10:671. doi: 10.3390/genes10090671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyne M.E., Narcross L., Martin V.J.J. Engineering plant secondary metabolism in microbial systems. Plant Physiol. 2019;179:844–861. doi: 10.1104/pp.18.01291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahimi S., Kim Y.J., Sukweenadhi J., Zhang D., Yang D.C. PgLOX6 encoding a lipoxygenase contributes to jasmonic acid biosynthesis and ginsenoside production in Panax ginseng. J. Exp. Bot. 2016;67:6007–6019. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erw358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratnadewi D. Alternatives in Synthesis, Modification and Application. IntechOpen; Bulgarian: 2017. Alkaloids in plant cell cultures. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reski R., Parsons J., Decker E.L. Moss-made pharmaceuticals: from bench to bedside. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2015;13:1191–1198. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rischer H., Szilvay G.R., Oksman-Caldentey K.-M. Cellular agriculture — industrial biotechnology for food and materials. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2020;61:128–134. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2019.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts S.C. Production and engineering of terpenoids in plant cell culture. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2007;3:387–395. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2007.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roslan H.A., Salter M.G., Wood C.D., White M.R., Croft K.P., Robson F., Coupland G., Doonan J., Laufs P., Tomsett A.B. Characterization of the ethanol-inducible alc gene-expression system in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2001;28:225–235. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2001.01146.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savageau M.A.J. Comparison of classical and autogenous systems of regulation in inducible operons. Nature. 1974;252:546–549. doi: 10.1038/252546a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer D.G., Zrÿd J.-P. Efficient gene targeting in the moss Physcomitrella patens. Plant J. 1997;11:1195–1206. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1997.11061195.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schena M., Lloyd A.M., Davis R.W. A steroid-inducible gene expression system for plant cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 1991;88:10421–10425. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.23.10421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwender J., Hay J.O.J. Predictive modeling of biomass component tradeoffs in Brassica napus developing oilseeds based on in silico manipulation of storage metabolism. Plant Physiol. 2012;160:1218–1236. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.203927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segečová A., Červený J., Roitsch T. Advancement of the cultivation and upscaling of photoautotrophic suspension cultures using Chenopodium rubrum as a case study. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2018;135:37–51. [Google Scholar]

- Shameer S., Vallarino J.G., Fernie A.R., Ratcliffe R.G., Sweetlove L.J.J. Flux balance analysis of metabolism during growth by osmotic cell expansion and its application to tomato fruits. Plant J. 2020;103:68–82. doi: 10.1111/tpj.14707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi P., Fu X., Liu M., Shen Q., Jiang W., Li L., Sun X., Tang K. Promotion of artemisinin content in Artemisia annua by overexpression of multiple artemisinin biosynthetic pathway genes. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2017;129:251–259. [Google Scholar]

- Shih P.M. Towards a sustainable bio-based economy: redirecting primary metabolism to new products with plant synthetic biology. Plant Sci. 2018;273:84–91. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2018.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shih P.M., Vuu K., Mansoori N., Ayad L., Louie K.B., Bowen B.P., Northen T.R., Loqué D.J. A robust gene-stacking method utilizing yeast assembly for plant synthetic biology. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:1–8. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonsen H., Chen D.-f., Xin Z., Xiwu P., King B.C. 2018. Heterologous Production of Patchoulol, β-Santalene, and Sclareol in Moss Cells: Google Patents. [Google Scholar]

- Smetanska I. Production of secondary metabolites using plant cell cultures. Adv. Biochem. Eng. Biotechnol. 2008;111:187–228. doi: 10.1007/10_2008_103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith R.H., Hood E.E. Agrobacterium tumefaciens transformation of monocotyledons. Plants (Basel) 1995;35:301–309. [Google Scholar]

- Sorrells T.R., Johnson A.D. Making sense of transcription networks. Cell. 2015;161:714–723. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabata H. Paclitaxel production by plant-cell-culture technology. Adv. Biochem. engineering/biotechnology. 2004;87:1–23. doi: 10.1007/b13538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vashee S., Arfi Y., Lartigue C. Budding yeast as a factory to engineer partial and complete microbial genomes. Curr. Opin. Syst. Biol. 2020;24:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.coisb.2020.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhounig A., Karcher D., Bock R. Inducible gene expression from the plastid genome by a synthetic riboswitch. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2010;107:6204–6209. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914423107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B., Kashkooli A.B., Sallets A., Ting H.-M., de Ruijter N.C.A., Olofsson L., Brodelius P., Pottier M., Boutry M., Bouwmeester H. Transient production of artemisinin in Nicotiana benthamiana is boosted by a specific lipid transfer protein from A. annua. Metab. Eng. 2016;38:159–169. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2016.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson S.A., Roberts S.C. Recent advances towards development and commercialization of plant cell culture processes for the synthesis of biomolecules. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2012;10:249–268. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2011.00664.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf L., Rizzini L., Stracke R., Ulm R., Rensing S.A. The molecular and physiological responses of Physcomitrella patens to ultraviolet-B radiation. Plant Physiol. 2010;153:1123–1134. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.154658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X., Qi L.S. A CRISPR–dCas toolbox for genetic engineering and synthetic biology. J. Mol. Biol. 2019;431:34–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2018.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan H., Cheung C.Y.M., Hilbers P.A.J., van Riel N.A. Flux balance analysis of plant metabolism: the effect of biomass composition and model structure on model predictions. Front. Plant Sci. 2016;7:537. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhan X., Zhang Y.-H., Chen D.-F., Simonsen H.T. Metabolic engineering of the moss Physcomitrella patens to produce the sesquiterpenoids patchoulol and α/β-santalene. Front. Plant Sci. 2014;5:636. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2014.00636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Chen M., Siemiatkowska B., Toleco M.R., Jing Y., Strotmann V., Zhang J., Stahl Y., Fernie A.R. A highly efficient agrobacterium-mediated method for transient gene expression and functional studies in multiple plant species. Plant Commun. 2020;1:100028. doi: 10.1016/j.xplc.2020.100028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Fernie A.R. Metabolons, enzyme-enzyme assemblies that mediate substrate channeling, and their roles in plant metabolism. Plant Commun. 2020:100081. doi: 10.1016/j.xplc.2020.100081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Fernie A.R. Stable and temporary enzyme complexes and metabolons involved in energy and redox metabolism. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2020 doi: 10.1089/ars.2019.7981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Nowak G., Reed D.W., Covello P.S. The production of artemisinin precursors in tobacco. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2011;9:445–454. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2010.00556.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Sampathkumar A., Kerber S.M.-L., Swart C., Hille C., Seerangan K., Graf A., Sweetlove L., Fernie A.R. A moonlighting role for enzymes of glycolysis in the co-localization of mitochondria and chloroplasts. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:1–15. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-18234-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y.J., Beard K.F.M., Swart C., Bergmann S., Krahnert I., Nikoloski Z., Graf A., Ratcliffe R.G., Sweetlove L.J., Fernie A.R. Protein-protein interactions and metabolite channelling in the plant tricarboxylic acid cycle. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:15212. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]