Abstract

Fusidic acid (FA) is a natural tetracyclic triterpene isolated from fungi, which is clinically used for systemic and local staphylococcal infections, including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and coagulase-negative staphylococci infections. FA and its derivatives have been shown to possess a wide range of pharmacological activities, including antibacterial, antimalarial, antituberculosis, anticancer, tumor multidrug resistance reversal, anti-inflammation, antifungal, and antiviral activity in vivo and in vitro. The semisynthesis, structural modification and biological activities of FA derivatives have been extensively studied in recent years. This review summarized the biological activities and structure–activity relationship (SAR) of FA in the last two decades. This summary can prove useful information for drug exploration of FA derivatives.

Keywords: fusidic acid, biological activities, structure-activity relationship, tetracyclic triterpene, antimicrobial

1 Introduction

Over the past 40 years, more than half of the new chemical entities approved for the treatment of various diseases have originated from unmodified natural products, their semi-synthetic derivatives, or synthetic biological analogs (Newman and Cragg, 2020). Natural products are rich in structural types and have a wide range of biological activities, and are the main source for the discovery of new chemical entities and lead compounds (Chen et al., 2017; Agarwal et al., 2020). Thus, natural products have long been regarded as important sources in drug design, especially for drugs for cancer and infectious diseases (Brown et al., 2014; Rodrigues et al., 2016; Agarwal et al., 2020). Furthermore, almost all-important natural products, such as terpenes, alkaloids, sesquiterpenes, and sugars, can be produced by fungi (Aly et al., 2011; Singh et al., 2019).

Fusidic acid (FA) is a tetracyclic triterpenoids isolated from fungi, which was first isolated from Fusidium coccineum in 1960 (Godtfredsen WO. et al., 1962; Godtfredsen W. O. et al., 1962). FA binds to elongation factor G (EF-G) as an inhibitor of protein synthesis (Yamaki, 1965; Kinoshita et al., 1968). Since 1962, FA has been clinically used for systemic and local staphylococcal infections, including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and coagulase-negative staphylococci infections (Godtfredsen WO. et al., 1962; Zhao et al., 2013). FA has been widely used throughout Europe, Australia, China, India, and other countries. There are many reasons why FA is not approved by USFDA, especially in funds and laws (Fernandes and Pereira, 2011). At present, FA is being promoted for approval in the United States market by Cempra Pharmaceuticals (ClinicalTrials.gov, 2020).

FA and its derivatives have been shown to possess a wide range of pharmacological activities, including antibacterial (Godtfredsen W. O. et al., 1962), antiparasitic (Gupta et al., 2013; Salama et al., 2013), antituberculosis (Cicek-Saydam et al., 2001), anticancer (Ni et al., 2019), tumor multidrug resistance (MDR) reversal (Guo et al., 2019), anti-inflammation (Kilic et al., 2002), antifungal (Bi et al., 2020), and antiviral activity (Liu et al., 2019) in vivo and in vitro. However, there is no review on the semisynthesis, biological activities, and structure–activity relationship (SAR) studies of FA derivatives in the last 2 decades. This review summarized the semisynthesis, modification and bioactivities of FA derivatives. The SARs of FA and its derivatives in antibacterial, antiparasitic, antituberculosis, antitumor and tumor MDR reversal were summarized. This review provides useful information for the development of FA derivatives and gives a direction for further inspiration to enrich its structures with good pharmacological activities.

2 The Biological Activities and Structure–Activity Relationships of FA

2.1 Antimicrobial Activity

2.1.1 Anti-Gram-Positive Bacterial Activity

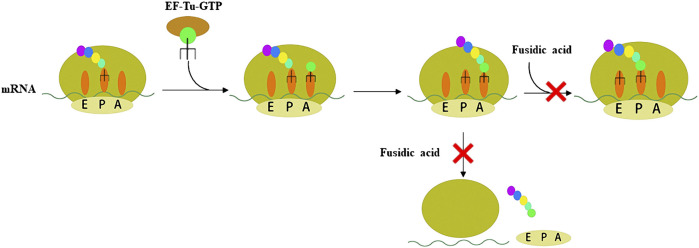

Resistance to antibiotic is a major obstacle to treating bacterial infection (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2019). Therefore, antibiotics with novel mechanisms of action and low drug-resistance to bacteria are needed. FA acts on EF-G, which is the only antibiotic that acts on this target. There are four stages of protein synthesis in bacteria: initiation, extension, translocation, and recycling (Figure 1, Fernandes, 2016). Translocation is catalyzed by EF-G with GTPase activity. FA forms a stable complex with EF-G-GTP hydrolysate (EF-G-GDP), which causes the translocation to be blocked (Bodley et al., 1969; Belardinelli and Rodnina, 2017). Another function of EF-G is to split the terminated ribosome with the help of ribosome releasing factor, and then the next mRNA translation can occur, so FA also blocks the recycling stage (Savelsbergh et al., 2009; Wilson, 2014). In other words, FA blocks the translocation and recycling stages of protein synthesis, thereby killing bacteria through this mechanism. Additionally, FA lacks appreciable cross-resistance with other antibiotics, which is mainly attributed to the particular mechanism of action of FA (Borg et al., 2015).

FIGURE 1.

Schematic representation of the two steps of peptide synthesis that FA blocks by binding to the EF-G-GDP complex.

According to previous metabolism studies of FA, the sodium salt of FA is well absorbed after oral administration with a bioavailability higher than 90%, and the FA binds highly and reversibly to protein (Turnidge, 1999; Still et al., 2011). Because of the high protein binding rate of FA, hyperbilirubinemia or jaundice is one of the main side effects of FA (Rieutord et al., 1995; Lapham et al., 2016). Many FA derivatives have been synthesized to develop antibiotics with better pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profiles.

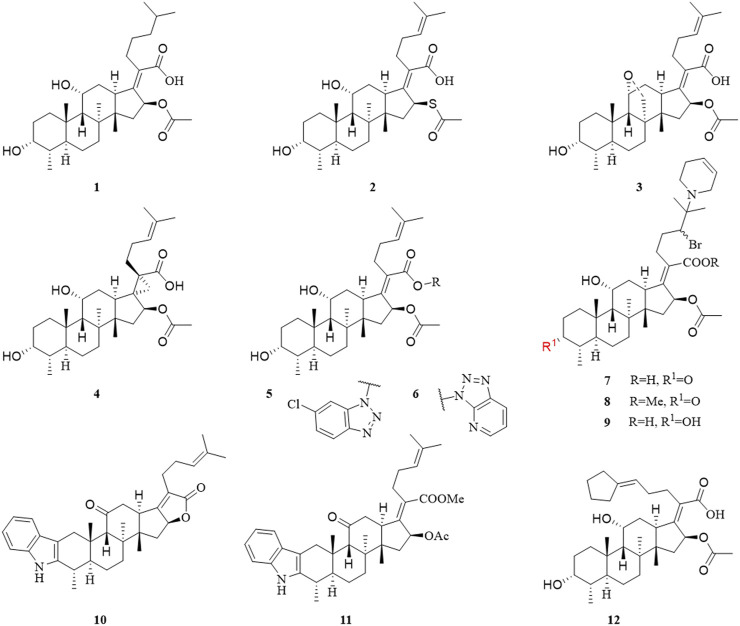

In 1979, Daehne et al. have synthesized more than 150 FA analogs, including modifications to the skeleton, the A, B, C, and D rings, and the side chains of FA, but the antibacterial activity of most of these derivatives was reduced or even completely abolished. The activity of a few compounds was maintained or enhanced, including derivatives with saturation of the delta-24 (25) double bond (1), substitution of the 16α-acetoxy by other groups (2), and conversion of the 11-OH to the corresponding ketone group (3) (Daehne et al., 1979).

Duvold et al. saturated the delta-17 (20) double bond of FA and obtained four stereoisomers, of which only 17(S),20(S)-dihydro-FA had the same potency as natural FA. This result indicated the necessity for the correct orientation and conformation of the side chains in a limited bioactive space for antimicrobial activity (Duvold et al., 2001). Subsequently, this group introduced a spiro-cyclopropane system in the delta-17 (20) double bond, and successfully synthesized 17(S),20(S)-methano-FA (4) (Figure 2), which exhibited the same activity against several Gram-positive bacteria as FA. This result further showed the importance of the side chains of FA for antimicrobial activity (Duvold et al., 2003).

FIGURE 2.

Structural formulae of compounds 1–12.

In 2006, to clarify the interaction between FA and its receptor EF-G, Riber et al. developed three photoaffinity-labeled FA derivatives with the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) values of 0.016–4 μg/ml. (Riber et al., 2006). In 2007, Schou et al. have synthesized two radiolabeled photolabile FA analogs. These derivatives are potential tools for revealing the interaction between FA and EF-G (Schou et al., 2007).

In 2018, Salimova et al. synthesized some cyanoethyl derivatives of FA, which were screened primarily in vitro. Modification of FA with cyanoethyl fragments did not increase the activity, which is consistent with the previously summarized SAR (Salimova et al., 2018). Lu et al. have designed and synthesized 14 derivatives that blocked the metabolic sites (3-OH and 21-COOH) of FA, six of which had good antibacterial activity, MIC values of compounds 5 and 6 were less than 0.25 μg/ml; however, this result was contrary to previously SAR studies of the 21-COOH, as summarized by Daehne et al. Pharmacokinetic experiments were also performed, compounds 5 and 6 released FA in vivo, and their half-life was longer than that of FA. These derivatives provided a new concept for the structural modification of FA, with a triazole ring introduced at the 21-COOH. The activity of these FA derivatives was maintained, indicating that this was a new route to obtain long-lasting and effective antibiotics by structural modification (Daehne et al., 1979; Lu et al., 2019).

Shakurova et al. synthesized three quaternary pyridinium salts and tetrahydropyridine derivatives (7, 8, and 9) of FA using an effective one-pot method, but after antimicrobial screening, the results showed that there was no inhibitory activity against the tested strains when the concentration of the derivatives was 32 μg/ml (Shakurova et al., 2019). In 2020, Salimova et al. synthesized two new indole derivatives (10 and 11) of FA by the Fischer reaction. The antimicrobial activity of the derivatives was tested against MRSA (strain ATCC 43300), and the compounds showed comparable activity to FA (Salimova et al., 2020).

Chavez et al. have synthesized 14 FA analogs, compound 12 has equivalent potency against clinical isolates of Staphylococcus aureus and Enterococcus faecium as well as an improved resistance profile in vitro when compared to FA. Significantly, 12 displays efficacy against FA-resistant strain of Staphylococcus aureus in a soft-tissue murine infection model. This study indicated the structural features of FA necessary for potent antibiotic activity and demonstrates that the resistance profile can be improved for this target and scaffold (Chavez et al., 2021).

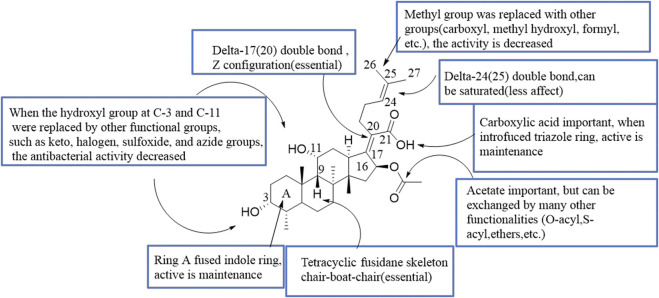

Since the marketing of FA, various structural modifications have been made, but only one derivative, l6-deacetoxy-l6β-acetylthio FA, is significantly more active than the parent antibiotic (Daehne et al., 1979). This review summarized the SAR of the antimicrobial activity of FA (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

SAR of the antibacterial activity of FA.

Recently, Hajikhani et al. used several international databases to discern studies addressing the prevalence of FA resistant S. aureus (FRSA), FA resistant MRSA (FRMRSA), and FA resistant methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (FRMSSA). The analyses manifested that the global prevalence of FRSA, FRMRSA, and FRMSSA was 0.5, 2.6, and 6.7%, respectively. These results indicated the need for prudent prescription of FA to stop or diminish the incidence of FA resistance. (Hajikhani et al., 2021).

In conclusion, since the antibacterial activity of FA was found, many structural modifications have been made to FA. However, the antibacterial activity of only two compounds reached the level of FA activity, the antibacterial activity of other derivatives is worse than FA. At present, the SAR summarized according to the existing literature is not perfect and needs to be further enriched. In recent years, drug-resistant bacterial of FA has appeared. It is necessary to study FA derivatives with better activity against drug-resistant bacterial.

2.1.2 Anti-M. tuberculosis Activity

According to the WHO, tuberculosis remains the world’s deadliest infectious killer. Worldwide, more than 4,000 people die of tuberculosis every day, and nearly 30,000 people are affected by this preventable and curable disease (World Health Organization, 2020b). In 1962, Godtfredsen et al. studied the antibacterial spectrum of FA and found that FA had some antituberculosis activity, but there was no further research performed (Godtfredsen WO. et al., 1962). In 1990, Hoffner et al. found that FA was effective against 30 clinically isolated Mycobacterium tuberculosis (M. tuberculosis) strains in vitro at concentrations of 32–64 mg/L, and was synergistic with ethambutol against M. tuberculosis (Hoffner et al., 1990). Fuursted et al. used a variety of tuberculosis bacilli (including drug-resistant tuberculosis bacilli) and determined the MIC values of FA against tuberculosis bacilli, which ranged from 8 to 32 mg/L (Fuursted et al., 1992; Fabry et al., 1996). Unlike the experimental results of Hoffner, Öztas did not observe either a synergistic or antagonistic effect when FA was used in combination with other standard antituberculosis drugs (Fuursted et al., 1992). The reason for this difference may be because the groups used different test methods. Previous studies have also found that FA was not cross-resistant with first-line drugs (Hoffner et al., 1990; Fuursted et al., 1992).

In 2008, Öztas et al. conducted susceptibility tests for FA in the sputum cultures of 728 tuberculosis patients. The results indicated that FA was effective at 32 mg/L in vitro, but resistance to FA was observed at 16 mg/L. This group suggested that FA might be an alternative antituberculosis drug (Öztas et al., 2008). FA was found to lack in vivo activity at doses of up to 200 mg/kg in a mouse model of tuberculosis (Shanika, 2017).

In 2014, to solve the problem that FA has no antituberculosis activity in vivo, Kigondu et al. adopted a repositioning strategy to determine whether FA could be used as an optional antituberculosis drug. They hope to synthesize and screen FA derivatives to study the antituberculosis activity and mechanism of action (Kigondu et al., 2014). In a recent study, Akinpelu et al. found that FA was a potential inhibitor of M. tuberculosis filamentous temperature sensitive mutant Z (FtsZ) by computer methods, including density function theory (DFT), molecular docking, and molecular dynamics simulations (Akinpelu et al., 2020).

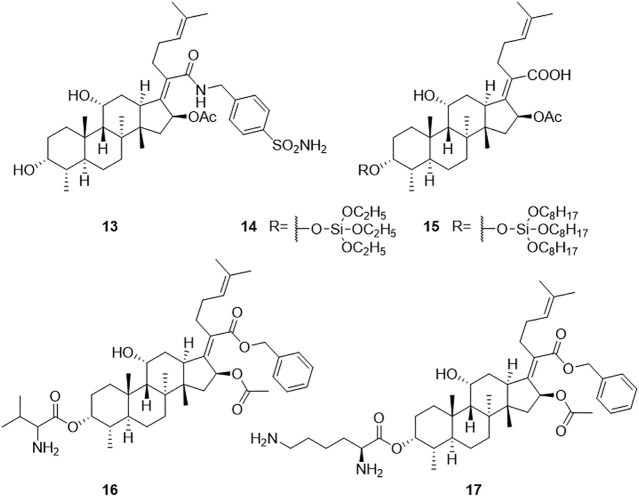

Dziwornu et al. have synthesized 28 FA derivatives, which were amidated at the 21-COOH, including C-21 FA ethanamides, anilides, and benzyl amides. All the derivatives were evaluated for their antituberculosis activity using the H37RvMa strain and the minimum inhibitory concentration required to inhibit the growth of 90% of the bacterial population (MIC90) values were determined. Compound 13 had the most potent antituberculosis activity with a MIC90 value of 2.71 μM, but not as good as FA with a MIC90 value of 0.24 μM (Figure 4) (Dziwornu et al., 2019).

FIGURE 4.

Structural formulae of compounds 13–17.

Njoroge et al. synthesized 27 derivatives of FA by esterification at the 3-OH and 21-COOH, including C-3 alkyl, aryl, and silicate esters, and the Mtb H37RvMa strain was used to determine the antituberculosis activity of the derivatives in vitro. The activities of the C-3 silicate derivatives were similar to that of FA. The minimum concentration required to inhibit the growth of 99% of the bacterial population (MIC99) values of compounds 14 and 15 against the Mtb H37RvMa strain were 0.2 and 0.3 μM, respectively, while FA with a MIC99 value of <0.15 μM (Njoroge et al., 2019).

Singh et al. used chemical biology and genetics, showed essentiality of its encoding gene fusA1 in M. tuberculosis by demonstrating that the transcriptional silencing of fusA1 is bactericidal in vitro and in macrophages. Thus, this study identified EF-G as the target of FA in M. tuberculosis. (Singh et al., 2021).

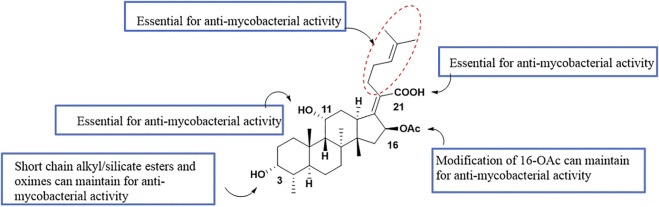

Singh et al. have summarized the preliminary SAR of 58 antituberculosis FA derivatives (Figure 5). It was found that the 11-OH, 21-COOH, and lipid side chains were necessary for antituberculosis activity, while modification at the 3-OH with short chain alkyl or silicate esters and oximes could maintain the activity, and replacing the acetoxy group of C-16 with a propionyloxy group maintained the activity (Singh et al., 2020).

FIGURE 5.

SAR of the antituberculosis activity of FA.

In conclusion, similar to the antibacterial modification of FA, the antituberculosis modification of FA has not made significant progress and needs to be further explored. And the reason why FA has no antituberculosis activity in vivo needs to be further clarified. It is also necessary to continue to study FA derivatives with antituberculosis activity in vivo and in vitro. If the above problems are solved, FA will be repositioned as an antituberculosis drug with novel mechanism of action.

2.1.3 Antifungal Activity

Many adults and pediatric patients use strong chemotherapy agents to treat hematological malignancies, thus increasing the incidence of invasive mycosis (Zając-Spychała et al., 2019; Malhotra, 2020). Because antifungal drugs are available in a limited number and are prone to drug resistance, there is a view that the key to the future development of antifungal drugs is the repurposing of marketed drugs (Zida et al., 2017; Nicola et al., 2019).

FA itself has no antifungal activity, but recently it has been reported that FA derivatives have antifungal activity. Cao et al. inadvertently found that FA derivative 16 inhibited the growth of Cryptococcus neoformans. The inhibition rate of compound 16 against C. neoformans was 94.58% at a concentration of 32 μg/ml. Among the reported compounds, compound 17 had the strongest MIC value (4 μg/ml) against C. neoformans (Cao et al., 2020). In another study, Shakurova et al. synthesized quaternary pyridinium salts, and the tetrahydropyridine derivative 9 had moderate activity at a concentration of 32 μg/ml against C. neoformans (Figure 4) (Shakurova et al., 2019).

There are a limited number of antifungal FA derivatives reported in the literature, but the data provide insights for the development of FA antifungal activity. Furthermore, this information provides guidance for the future design of FA derivatives with good antifungal activity and selectivity.

2.2 Antiparasitic Activity

2.2.1 Antimalarial Activity

According to the World Health Organization (WHO) World Malaria Report 2020, it was estimated that there were 229 million new malaria infections, and 409,000 people died of malaria, worldwide in 2019 (World Health Organization, 2020a). Plasmodium falciparum is resistant to existing antimalarial drugs, including artemisinin, which poses a challenge for antimalarial treatment. Therefore, there is an urgent need for new antimalarial drugs, especially those with novel mechanisms of action and no cross-resistance to existing drugs (Biddau and Sheiner, 2019).

As early as 1985, FA was found to have antimalarial activity in vitro (Black et al., 1985). Johnson et al. found that FA killed malaria parasites (P. falciparum line D10) with an IC50 value of 52.8 µM, and then characterized the possible target of FA against malaria, which is EF-G in two organelles of Plasmodium, the apicoplast and mitochondria. It could be an effective lead compound because of its mechanism of action (Johnson et al., 2011). Compared with P. falciparum mitochondria EF-G, FA had a better effect on apicoplast EF-G. The reason for mitochondrial EF-G resistance is at least partly because there is a conservative three amino acid sequence (GVG motif) in the switch I loop, however this motif is not found in apicoplast EF-G (Gupta et al., 2013).

Kaur et al. synthesized a series of compounds in which the 21-COOH of FA was substituted with various bioisosteres, and evaluated the activity in vitro with the chloroquine-sensitive NF54 strain of the malaria parasite P. falciparum. Among these compounds, the antiplasmodial activity IC50, CC50 and selection index of the most active compound 18 were 1.7, 77.4, and 46 μM, respectively. The IC50, CC50, and selection index of FA were 59.0, 194.0, and 3 μM, respectively. Compared with FA, compound 18 has a higher SI value. Furthermore, this group constructed apicoplast and mitochondrial EF-G homology structure models of P. falciparum, and compound 18 was docked with these two models. The docking results showed that the EF-G binding site of compound 18 and FA was consistent, but compound 18 had a higher binding score (Figure 6) (Kaur et al., 2015).

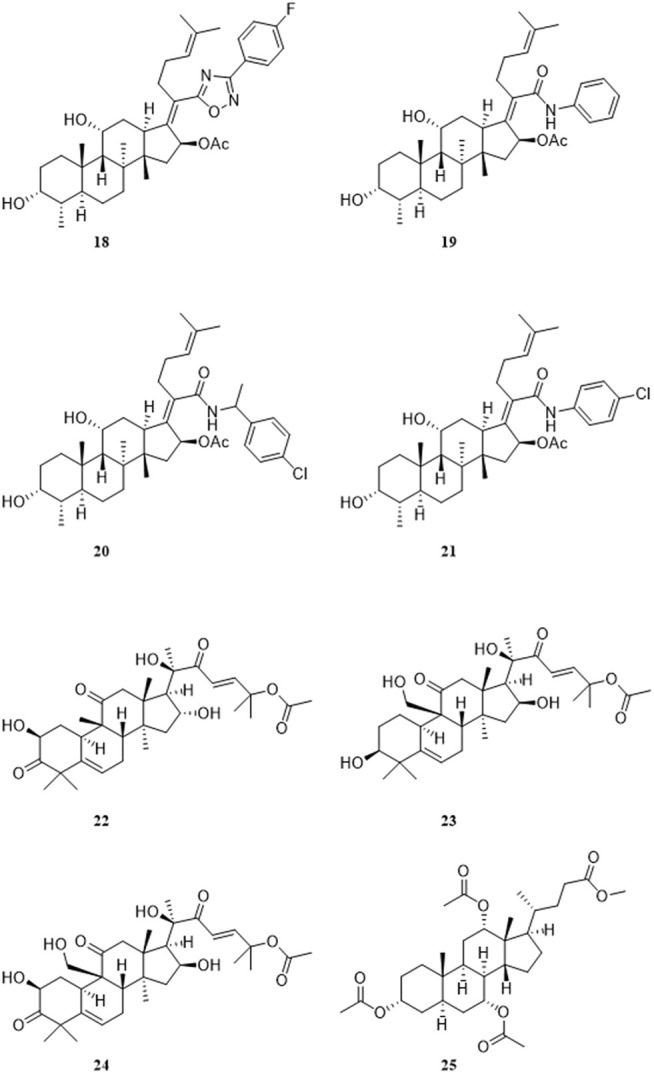

FIGURE 6.

Structural formulas of compounds 18–25.

Espinoza-Moraga et al. amidated or esterified the 21-COOH in FA with various substituents, including ester chains and aromatic compounds, and evaluated the antiplasmodial activity of these compounds in vitro against the chloroquine-sensitive NF54 strains and multidrug-resistant K1 strains of the malarial parasite P. falciparum. Compound 19 had the best antiplasmodial activity, with IC50 values of 1.2 and 1.4 μM against the NF54 and K1 strains, respectively. Unfortunately, the mechanism of action was not explored (Espinoza-Moraga et al., 2016). Kaur et al. developed a 3D-QSAR model based on the antiplasmodial activity of 61 FA derivatives that they had synthesized previously. The verified Hypo2 model was used as a three-dimensional structure search query to screen combinatorial libraries based on FA. Eight virtual screening hit compounds were selected and synthesized, of which compounds 20 and 21 had IC50 values of 0.3 and 0.7 μM, respectively, for the NF54 strain of P. falciparum. The IC50 values of these two compounds for the drug-resistant K1 strain of P. falciparum were both 0.2 μM, and no appreciable cytotoxicity was detected (Kaur et al., 2018).

Pavadai et al. used FA as a search query, and adopted two-dimensional fingerprint- and three-dimensional shape-based virtual screening methods to obtain new inhibitors of P. falciparum from their in-house database, including 708 steroid-type natural products. After further screening, this group successfully identified nine compounds that inhibited the growth of the NF54 strain of P. falciparum, with IC50 values of less than 20 μM. The IC50 values of the four most active compounds 22–25 were 1.39, 1.76, 2.92, and 3.45 μM, respectively. Moreover, the predicted absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) properties of these four compounds were comparable to FA (Pavadai et al., 2017).

To date, the chemical modification of FA for antimalarial activity has been mainly concentrated on the 21-COOH. Esterification or amidation is beneficial to the activity, and amidation is better than esterification for activity. The structural modification of other sites of FA needs to be further explored. FA derivatives have good inhibitory activity against P. falciparum, and apicoplast EF-G is the main action site of FA. It is necessary to modify FA to improve selectivity for apicoplast EF-G. Thus, FA derivatives have potential to be repositioned as an antimalarial drug.

2.2.2 Other Antiparasitic Activities

Rizk et al. described the inhibitory effects of FA on the in vitro growth of bovine and equine Babesia and Theileria parasites. The in vitro growth of four Babesia species that was significantly inhibited by micromolar concentrations of FA (IC50 values = 144.8, 17.3, 33.3, and 56.25 µM for Babesia bovis, Babesia bigemina, Babesia caballi, and Theileria equi, respectively). These results indicate that FA might be incorporated in treatment of babesiosis (Rizk et al., 2020).

Payne et al. investigated the therapeutic value of FA for T. gondii and found that the drug was effective in tissue culture, but not in a mouse model of infection. This work highlights the necessity of in vivo follow-up studies to validate in vitro drug investigations. (Payne et al., 2013).

2.3 Tumor Related Activity

2.3.1 Antitumor Activity

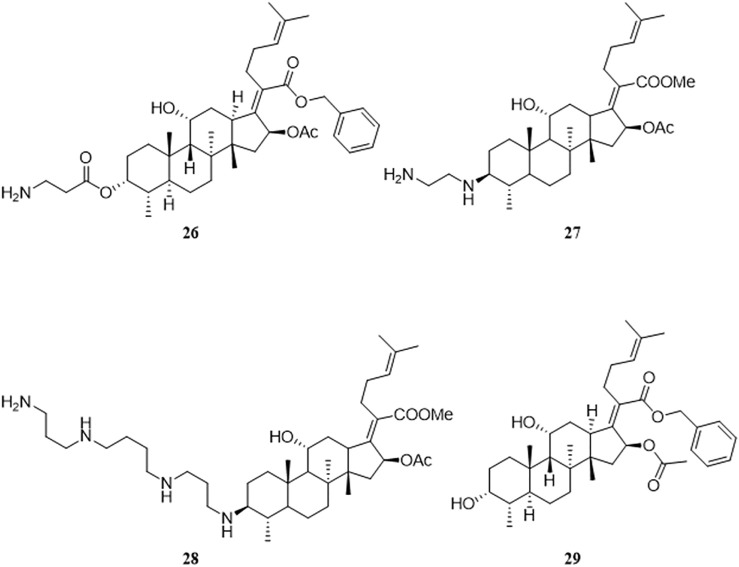

Malignant tumors are a health issue all over the world. There were an estimated 19.3 million new cases of cancer and almost 10.0 million deaths from cancer worldwide in 2020. (Ferlay et al., 2021). In 2019, Ni et al. accidentally discovered that FA derivatives have antitumor activity. Among the derivatives synthesized by this group, compounds where the 21-COOH was modified by a benzyl group, and with amino terminal modification at the C-3 position, had antitumor activity, of which compound 26 was the most active compound (Ni et al., 2019). Compound 26 had antitumor activity against various tumor cell lines including HeLa, U87, KBV, MKN45, and JHH-7, with IC50 values ranging from 1.26 to 3.57 μM. A preliminary mechanistic study was performed, which indicated that neo-synthesized proteins were decreased in HeLa cells under the action of compound 26, and the ratio of cells in the Sub-G0/G1 phase was increased, as determined by flow cytometry monitoring, thus leading to HeLa cell apoptosis. Compound 26 also exhibited good antitumor activity in vivo against a xenograft tumor of HeLa cells in athymic nude mice (Figure 7).

FIGURE 7.

Structural formulae of compounds 26–29.

Salimova et al. adopted different substituted amino groups to modify the 3-OH of FA, with or without esterification of the 21-COOH, to synthesize a series of 3-amino-substituted FA derivatives. To determine the antitumor activity of these derivatives, the researchers used nine different types of human tumor cell lines (sourced from the American Cancer Institute NCI-60) to study the antitumor activity of these compounds in vitro. Compound 27 had the highest cytotoxicity against leukemia cells and compound 28 had the broadest antitumor activity, including against leukemia, non-small cell lung cancer, colon cancer, neurological tumors, melanoma, ovarian cancer, and renal cancer (Salimova et al., 2019).

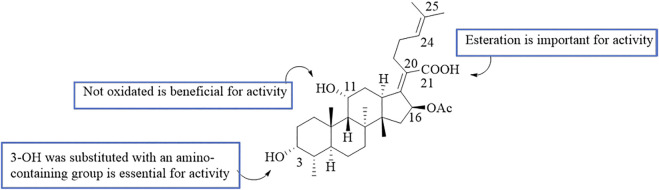

By analyzing the relationship between antitumor activity and structure of FA, the following preliminary SAR was obtained (Figure 8) (Ni et al., 2019; Salimova et al., 2019).

FIGURE 8.

SAR of the antitumor activity of FA.

2.3.2 Tumor Multidrug Resistance Reversal Activity

MDR is the main cause of drug resistance in many tumors, and is the main factor leading to the failure of chemotherapy. MDR affects patients with a variety of hematological and solid tumors (Persidis, 1999). Drug-sensitive cells can be killed by chemotherapeutics, but there may be a proportion of drug-resistant tumor cells left behind, which grow later, resulting in resistance to chemotherapeutics, leading to treatment failure (Lage, 2008). Currently, it is considered that the most effective strategy to overcome MDR is to develop MDR reversal agents.

Several MDR reversal agents have failed in clinical trials because of inherent toxicity, low selectivity, or complex pharmacokinetic interactions (Palmeira et al., 2012). Therefore, a safe and effective MDR reversal agent with low toxicity is urgently needed. To date, many natural products with different structural types have been developed as potential MDR reversal agents (Kumar and Jaitak, 2019).

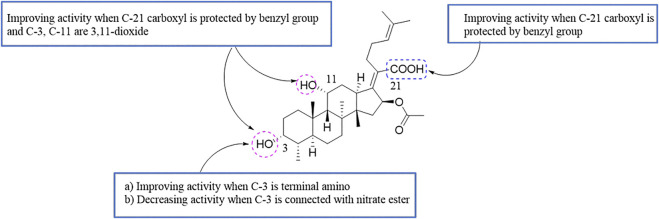

Guo et al. found that FA derivatives have tumor MDR reversal activity. The derivative 29, which was modified with a benzyl group at the 21-COOH, had good MDR reversal activity in vitro. Further studies revealed that the combination of derivative 29 with paclitaxel re-sensitized the multidrug-resistant oral epidermoid carcinoma (KBV) cell line to paclitaxel. A mechanism study found that compound 29 enhanced the ATPase activity of P-glycoprotein (P-gp) by inhibiting the drug pump activity of P-gp, but did not affect the expression of P-gp (Guo et al., 2019).

According to the results for MDR reversal activity, the SAR of FA derivatives has been preliminarily summarized (Figure 9).

FIGURE 9.

SAR of the tumor multidrug resistance reversal activity of FA.

According to the existing literature, FA has certain potential in antitumor and tumor MDR reversal activity. However, there are few studies in antitumor and tumor MDR reversal activity of FA, which needs to be further explored.

2.4 Anti-Inflammatory Activity

Inflammation is a complex biological response to injury, and to attack pathogens as part of the body’s immune response, which results in symptoms that include pain, fever, erythema, and edema (Ferrero-Miliani et al., 2007). The impact of antimicrobial agents on the immune and inflammatory systems and their possible clinical significance have greatly attracted the interest of scientists (Bosnar et al., 2019).

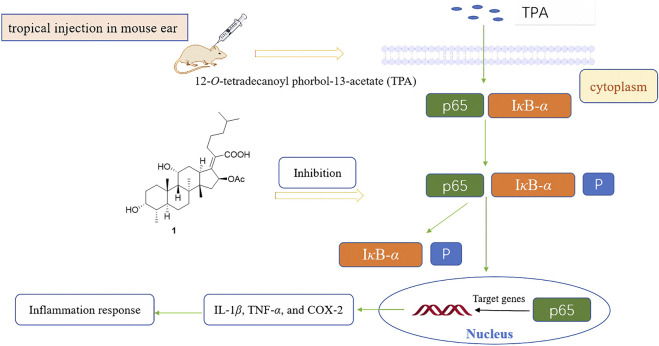

FA has been found to have some anti-inflammatory effects in mice and rats in vivo, especially by reducing the release of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) (Table 1) (Bosnar et al., 2019). In 2018, Wu et al. saturated the delta-24 (25) double bond of FA and thus obtained the hydrogenated derivative 1. The antimicrobial activity of FA and compound 1 were tested against six bacterial strains, and the results showed that both FA and 1 showed high levels of antimicrobial activity against Gram-positive strains. The anti-inflammatory activity of these compounds was evaluated using the 12-O-tetradecanoyl phorbol-13-acetate (TPA)-induced mouse ear edema model. The results showed that FA and 1 effectively reduced TPA-induced ear edema in a dose-dependent manner, and this inhibitory effect was associated with the inhibition of TPA-induced upregulation of the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β, TNF-α, and COX-2. Furthermore, 1 significantly inhibited the expression levels of p65, IκB-α, and p-IκB-α in TPA-induced mouse ear edema models (Figure 10) (Wu PP. et al., 2018).

TABLE 1.

Experiments show that FA modulates immunity and the inflammatory process.

| Pharmacological actions | References |

|---|---|

| FA decreased the plasma peak of TNF-α, improved the survival rate of neonatal mice, and decreased plasma TNF-α during endotoxic shock | Genovese et al. (1996) |

| FA protected mice from concanavalin-A-induced hepatitis. At the same time, the plasma levels of IL-2, IFN-γ, and TNF-α were significantly decreased, but the levels of IL-6 were increased | Nicoletti et al. (1998) |

| FA was beneficial for the treatment of experimental autoimmune neuritis in rats (a model of Guillain-Barre syndrome), where the serum levels of interferon-gamma, IL-10, and TNF-α were reduced | Marco et al. (1999) |

| FA could alleviate the tissue edema caused by local formalin injection in rats | Kilic et al. (2002) |

| The co-administration of FA and daptomycin significantly reduced the joint and tissue levels of systemic TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β, and other pro-inflammatory cytokines in mice infected with multidrug-resistant group B streptococci | El-Shemi and Faidah (2011) |

FIGURE 10.

Schematic representation of the anti-inflammation mechanism of compound 1 in TPA-induced mouse ear edema models.

According to current research, FA derivative has showed anti-inflammatory activity in vivo and in vitro. However, there is no literature yet reported the structural modification of anti-inflammatory of FA, which needs to be enriched. And other possible anti-inflammatory mechanisms need to be further studied.

2.5 Antiviral Activity

Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), a new type of RNAβ coronavirus, has caused a pandemic worldwide (Gallelli et al., 2020). There is currently no effective treatment for the virus, and effective preventive and therapeutic drugs need to be identified (Sanders et al., 2020). There have been many reports of antibiotic agents that have antiviral activity. Minocycline, a tetracycline drug, can effectively inhibit human immunodeficiency viruses (HIV) (Zink et al., 2005). Aminoglycoside antibiotics can inhibit the replication of the herpes simplex virus, influenza A virus, and Zika virus in vivo and in vitro (Gopinath et al., 2018).

As early as 1967, the first antiviral research on FA appeared, FA was found to be ineffective against coxsackie A21 or rhinovirus infection, both orally and intranasally, and fifteen derivatives were found to be inactive or toxic (Acornley et al., 1967). There have been several reports regarding the effectiveness of FA toward human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and the mechanism of action has also been studied. FA is an anionic surfactant that acts on the lipid molecular layer of infected cells, exposing the viral proteins to the host immune system to prevent the HIV from forming syncytium in vitro (Lloyd et al., 1988). Additionally, FA can directly inhibit reverse transcriptase and thus has anti-HIV activity (Famularo et al., 1993). Four clinical trials of FA in HIV-infected patients have been conducted, but the results were contradictory (Faber et al., 1987; Youle et al., 1989; Hørding et al., 1990; Famularo et al., 1993). Furthermore, a study has shown that human leukocyte interferon can enhance the anti-HIV effect of FA (Degre and Beck, 1994).

In recent years, it has been reported that FA was effective against John Cunningham virus (JCV) in vivo and in vitro (Brickelmaier et al., 2009; Chan et al., 2015). Liu et al. found that FA had good antiviral activity against enterovirus A71 (EV-A71) and coxsackievirus A16 (CV-A16). The potential antiviral mechanism is related to the inhibition of viral RNA replication and the synthesis of viral proteins (Liu et al., 2019). Kwofie et al. found that FA was the potential anti-SARS-CoV-2 compounds by antiviral activity predictions (Kwofie et al., 2021).

Although it has been found that FA has good in vivo and in vitro activity against a variety of viruses, there have been few studies on the antiviral effects of FA derivatives, which merit future exploration. Furthermore, whether FA has a therapeutic effect against SARS-CoV-2 is also a possible research direction.

2.6 Other Activities

Some antibiotics have been discovered to have the potential to treat neurological diseases, acting as neuroprotective agents via various pathways, including rifampicin, rapamycin, d-cycloserine, and ceftriaxone (Batson et al., 2017; Lin et al., 2017; Reglodi et al., 2017; Wu X. et al., 2018). Additionally, the property of easily crossing the blood-brain barrier is one of the necessary criteria for a neuroprotective agent, and researchers have found that FA has this characteristic (Mindermann et al., 1993).

Park et al. first discovered that FA had neuroprotective effects. This group used sodium nitroprusside (SNP) to pretreat C6 glial cells, and found that FA prevented SNP-induced cell death in a dose-dependent manner at 5–20 μM. Moreover, a mechanism study was performed, and the results indicated that FA had a neuroprotective effect against SNP-induced cytotoxicity through the 5′ adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) pathway and apoptotic events (Park et al., 2019).

Unfortunately, this research was only performed in vitro, not in vivo. Additionally, the mechanism of action of FA was not fully elucidated, and more studies are needed to clarify the mechanism. Nevertheless, the results of this study have provided a potential clinical strategy, suggesting that FA derivatives may be used for the treatment of neurological disease as neuroprotective agents.

3 Conclusion and Perspectives

FA can be obtained by fermentation, and has attracted increasing attention in recent years. In summary, FA is a promising natural bioactive substance with a variety of pharmacological activities for the potential treatment of many diseases. Great progress has been achieved in the investigation of the pharmacological activity, SAR, and mechanism of action of FA. FA consists of a tetracyclic skeleton with several available sites for chemical modification, which enables the synthesis of novel compounds with potentially higher potency and selectivity, and with fewer side effects.

Despite extensive research and development into FA in recent years, considerable challenges still lie ahead because of the limited amount of studies on the pharmacological activities and mechanisms of action to date. FA has a very short half-life after oral absorption. Consequently, FA must be administered frequently, resulting in fluctuations in the plasma drug concentration and increasing the risk of poor clinical outcomes, including side effects and adverse reactions, limiting the application of FA in clinical use. Considering that triterpenes are known to possess a wide range of pharmacological activities, it is possible that other new pharmacological effects of FA still to be discovered. Much of the present research has been confined to in vitro rather than in vivo studies; hence, whether FA is effective or sufficiently efficient in vivo is questionable and must be validated.

In view of the above challenges, the following strategies will be of great value in future research into the drug development and clinical application of FA:

1) Extending the half-life of FA by adopting appropriate pharmaceutic or chemical methods. For example, FA is administered in liposomes or structural modifications that occlude the 21 COOH metabolic site.

2) From the view of the pharmacology and mechanism, further investigation of the potential pharmacological activities of FA expands the scope of its use. Meanwhile, more research into the mechanism of action will enable a better understanding of how FA works. Furthermore, a large number of in vivo studies should be conducted to validate its effectiveness, because a high sensitivity in vitro study does not necessarily represent the same result in vivo.

3) Synthesizing novel derivatives by structural modification at the confirmed modification sites, or other potentially available sites of FA, to explore more promising agents with higher activity and better drug-like properties.

4) As a clinically used drug, FA has the possibility of repositioning as an antituberculous or antimalarial drug, which requires more research in these fields. The antitumor, tumor MDR reversal, anti-inflammatory, antifungal activities of FA are newly discovered biological activities in recent years, which have larger research value.

In conclusion, the knowledge regarding FA has been growing rapidly in recent years, but there is still room for improvement in the understanding of its pharmacology, mechanism of action, and structural modification.

Acknowledgments

We thank Victoria Muir, PhD, from Liwen Bianji, Edanz Group China (www.liwenbianji.cn/ac), edited the English text of a draft of this manuscript.

Author Contributions

JL, WJ and YB wrote the first draft and provided the organization and frame work of the article. DZ and YZ provided critical revisions. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

Funding

This work was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81773563), The Science and Technology Support Program for Youth Innovation in Universities of Shandong (No. 2020KJM003), Top Talents Program for One Case One Discussion of Shandong Province.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors, and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- Acornley J. E., Bessell C. J., Bynoe M. L., Godtfredsen W. O., Knoyle J. M. (1967). Antiviral Activity of Sodium Fusidate and Related Compounds. Br. J. Pharmacol. Chemother. 31, 210–220. 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1967.tb01992.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal G., Carcache P. J. B., Addo E. M., Kinghorn A. D. (2020). Current Status and Contemporary Approaches to the Discovery of Antitumor Agents from Higher Plants. Biotechnol. Adv. 38, 107337. 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2019.01.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akinpelu O. I., Lawal M. M., Kumalo H. M., Mhlongo N. N. (2020). Drug Repurposing: Fusidic Acid as a Potential Inhibitor of M. tuberculosis FtsZ Polymerization - Insight from DFT Calculations, Molecular Docking and Molecular Dynamics Simulations. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 121, 101920. 10.1016/j.tube.2020.101920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aly A. H., Debbab A., Proksch P. (2011). Fifty Years of Drug Discovery from Fungi. Fungal Divers. 50, 3–19. 10.1007/s13225-011-0116-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Batson S., De Chiara C., Majce V., Lloyd A. J., Gobec S., Rea D., et al. (2017). Inhibition of D-Ala:D-Ala Ligase through a Phosphorylated Form of the Antibiotic D-Cycloserine. Nat. Commun. 8, 1939–1947. 10.1038/s41467-017-02118-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belardinelli R., Rodnina M. V. (2017). Effect of Fusidic Acid on the Kinetics of Molecular Motions during EF-G-Induced Translocation on the Ribosome. Sci. Rep. 7, 10536–10538. 10.1038/s41598-017-10916-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bi Y., Lu J., Ni J., Cao Y. (2020). Application of Amino Substituted Fusidic Acid Derivatives in Preparing Antifungal Drugs. Beijing: China National Intellectual Property Administration. CN Patent No ZL 2018 1 1 479612.8. [Google Scholar]

- Biddau M., Sheiner L. (2019). Targeting the Apicoplast in Malaria. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 47, 973–983. 10.1042/BST20170563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black F. T., Wildfang I. L., Borgbjerg K. (1985). Activity of Fusidic Acid against Plasmodium Falciparum In Vitro . Lancet 1, 578–579. 10.1016/s0140-6736(85)91234-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodley J. W., Zieve F. J., Lin L., Zieve S. T. (1969). Formation of the Ribosome-G Factor-GDP Complex in the Presence of Fusidic Acid. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 37, 437–443. 10.1016/0006-291X(69)90934-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borg A., Holm M., Shiroyama I., Hauryliuk V., Pavlov M., Sanyal S., et al. (2015). Fusidic Acid Targets Elongation Factor G in Several Stages of Translocation on the Bacterial Ribosome. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 3440–3454. 10.1074/jbc.M114.611608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosnar M., Haber V. E., Graham G. G. (2019). “Influence of Antibacterial Drugs on Immune and Inflammatory Systems,” in Nijkamp and Parnham's Principles of Immunopharmacology. Editors Parnham M. J., Nijkamp F. P., Rossi A. G. (New York, NYCham: Springer; ), 589–611. 10.1007/978-3-030-10811-3_29 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brickelmaier M., Lugovskoy A., Kartikeyan R., Reviriego-Mendoza M. M., Allaire N., Simon K., et al. (2009). Identification and Characterization of Mefloquine Efficacy against JC Virus In Vitro . Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53, 1840–1849. 10.1128/AAC.01614-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown D. G., Lister T., May-Dracka T. L. (2014). New Natural Products as New Leads for Antibacterial Drug Discovery. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 24, 413–418. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2013.12.059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y., Ni J., Ji W., Shang K., Liang K., Lu J., et al. (2020). Synthesis, Antifungal Activity and Potential Mechanism of Fusidic Acid Derivatives Possessing Amino-Terminal Groups. Future Med. Chem. 12, 763–774. 10.4155/fmc-2019-0289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2019). Antibiotic Resistance Threats Report in the United States. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/pdf/threats-report/2019-ar-threats-report-508.pdf (Accessed August 07, 2021).

- Chan J. F., Ma M. K., Chan G. S., Chan G. C., Choi G. K., Chan K. H., et al. (2015). Rapid Reduction of Viruria and Stabilization of Allograft Function by Fusidic Acid in A Renal Transplant Recipient with JC Virus-Associated Nephropathy. Infection 43, 577–581. 10.1007/s15010-015-0721-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia Chavez M., Garcia A., Lee H. Y., Lau G. W., Parker E. N., Komnick K. E., et al. (2021). Synthesis of Fusidic Acid Derivatives Yields a Potent Antibiotic with an Improved Resistance Profile. ACS. Infect. Dis. 7, 493–505. 10.1021/acsinfecdis.0c00869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., de Bruyn Kops C., Kirchmair J. (2017). Data Resources for the Computer-Guided Discovery of Bioactive Natural Products. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 57, 2099–2111. 10.1021/acs.jcim.7b00341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicek-Saydam C., Cavusoglu C., Burhanoglu D., Hilmioglu S., Ozkalay N., Bilgic A. (2001). In Vitro Susceptibility of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis to Fusidic Acid. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 7, 700–702. 10.1046/j.1469-0691.2001.00341.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ClinicalTrials.gov (2020). Oral Sodium Fusidate (CEM-102) for the Treatment of Staphylococcal Bone or Joint Infections. Available at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02569541? term=fusidic+acid&cntry=US&draw=2&rank=1 (Accessed September 14, 2021).

- Daehne W. V., Godtfredsen W. O., Rasmussen P. R. (1979). Structure-Activity Relationships in Fusidic Acid-type Antibiotics. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 25, 95–146. 10.1016/S0065-2164(08)70148-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degré M., Beck S. (1994). Anti-HIV Activity of Dideoxynucleosides, Foscarnet and Fusidic Acid Is Potentiated by Human Leukocyte Interferon in Blood-Derived Macrophages. Chemotherapy 40, 201–208. 10.1159/000239193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duvold T., Sørensen M. D., Björkling F., Henriksen A. S., Rastrup-Andersen N. (2001). Synthesis and Conformational Analysis of Fusidic Acid Side Chain Derivatives in Relation to Antibacterial Activity. J. Med. Chem. 44, 3125–3131. 10.1021/jm010899a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duvold T., Jørgensen A., Andersen N. R., Henriksen A. S., Dahl Sørensen M., Björkling F. (2003). 17S,20S-Methanofusidic Acid, a New Potent Semi-synthetic Fusidane Antibiotic. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 12, 3569–3572. 10.1016/S0960-894X(02)00797-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dziwornu G. A., Kamunya S., Ntsabo T., Chibale K. (2019). Novel Antimycobacterial C-21 Amide Derivatives of the Antibiotic Fusidic Acid: Synthesis, Pharmacological Evaluation and Rationalization of Media-dependent Activity Using Molecular Docking Studies in the Binding Site of Human Serum Albumin. Med. Chem. Commun. 10, 961–969. 10.1039/C9MD00161A [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Shemi A. G., Faidah H. S. (2011). Synergy of Daptomycin with Fusidin against Invasive Systemic Infection and Septic Arthritis Induced by Type IV Group B Streptococci in Mice. Afr. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 5, 1125–1131. 10.5897/AJPP11.396 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Espinoza-Moraga M., Singh K., Njoroge M., Kaur G., Okombo J., De Kock C., et al. (2016). Synthesis and Biological Characterisation of Ester and Amide Derivatives of Fusidic Acid as Antiplasmodial Agents. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 27, 658–661. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2016.11.077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faber V., Dalgleish A. G., Newell A., Malkovsky M. (1987). Inhibition of HIV Replication In Vitro by Fusidic Acid. Lancet 2, 827–828. 10.1016/S0140-6736(87)91016-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabry W., Schmid E. N., Ansorg R. (1996). Comparison of the E Test and A Proportion Dilution Method for Susceptibility Testing of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis. J. Med. Microbiol. 44, 394–401. 10.1099/00222615-44-3-227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Famularo G., De Simone C., Tzantzoglou S., Trinchieri V., Moretti S., Tonietti G. (1993). In Vivo and In Vitro Efficacy of Fusidic Acid in HIV Infection. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 685, 341–343. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb35885.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferlay J., Colombet M., Soerjomataram I., Parkin D. M., Piñeros M., Znaor A., et al. (2021). Cancer Statistics for the Year 2020: An Overview. Int. J. Cancer 149, 778–789. 10.1002/ijc.33588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes P., Pereira D. (2011). Efforts to Support the Development of Fusidic Acid in the United States. Clin. Infect. Dis. 52, S542–S546. 10.1093/cid/cir170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes P. (2016). Fusidic Acid: A Bacterial Elongation Factor Inhibitor for the Oral Treatment of Acute and Chronic Staphylococcal Infections. Cold Spring Harb Perspect. Med. 6, a025437. 10.1101/cshperspect.a025437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrero-Miliani L., Nielsen O. H., Andersen P. S., Girardin S. E. (2007). Chronic Inflammation: Importance of NOD2 and NALP3 in Interleukin-1beta Generation. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 147, 227–235. 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2006.03261.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuursted K., Askgaard D., Faber V. (1992). Susceptibility of Strains of the Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Complex to Fusidic Acid. APMIS 100, 663–667. 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1992.tb03983.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallelli L., Zhang L., Wang T., Fu F. (2020). Severe Acute Lung Injury Related to COVID-19 Infection: A Review and the Possible Role for Escin. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 60, 815–825. 10.1002/jcph.1644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genovese F., Mancuso G., Cuzzola M., Cusumano V., Nicoletti F., Bendtzen K., et al. (1996). Improved Survival and Antagonistic Effect of Sodium Fusidate on Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha in A Neonatal Mouse Model of Endotoxin Shock. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40, 1733–1735. 10.1128/AAC.40.7.1733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godtfredsen W. O., Jahnsen S., Lorck H., Roholt K., Tybring L. (1962a). Fusidic Acid: A New Antibiotic. Nature 193, 987. 10.1038/193987a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godtfredsen W. O., Roholt K., Tybring L. (1962b). Fucidin, A New Antibiotic. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 86, 1122–1123. 10.1016/S0140-6736(62)91968-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gopinath S., Kim M. V., Rakib T., Wong P. W., Van Zandt M., Barry N. A., et al. (2018). Topical Application of Aminoglycoside Antibiotics Enhances Host Resistance to Viral Infections in a Microbiota-independent Manner. Nat. Microbiol. 3, 611–621. 10.1038/s41564-018-0138-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo M., Ren Q., Wang B., Ji W., Ni J., Feng Y., et al. (2019). Discovery and Synthesis of 3- and 21-substituted Fusidic Acid Derivatives as Reversal Agents of P-Glycoprotein-Mediated Multidrug Resistance. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 182, 111668. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2019.111668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta A., Mir S. S., Saqib U., Biswas S., Vaishya S., Srivastava K., et al. (2013). The Effect of Fusidic Acid on Plasmodium Falciparum Elongation Factor G (EF-G). Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 192, 39–48. 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2013.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajikhani B., Goudarzi M., Kakavandi S., Amini S., Zamani S., van Belkum A., et al. (2021). The Global Prevalence of Fusidic Acid Resistance in Clinical Isolates of Staphylococcus aureus: a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control. 10, 75. 10.1186/s13756-021-00943-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hørding M., Christensen K. C., Faber V. (1990). Fusidic Acid Treatment of HIV Infection: No Significant Effect in A Pilot Trial. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 22, 649–652. 10.3109/00365549009027116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffner S. E., Olsson-Liljequist B., Rydgård K. J., Svenson S. B., Källenius G. (1990). Susceptibility of Mycobacteria to Fusidic Acid. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 9, 294–297. 10.1007/BF01968066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson R. A., McFadden G. I., Goodman C. D. (2011). Characterization of Two Malaria Parasite Organelle Translation Elongation Factor G Proteins: The Likely Targets of the Anti-malarial Fusidic Acid. PLoS One 6, e20633. 10.1371/journal.pone.0020633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur G., Singh K., Pavadai E., Njoroge M., Espinoza-Moraga M., De Kock C., et al. (2015). Synthesis of Fusidic Acid Bioisosteres as Antiplasmodial Agents and Molecular Docking Studies in the Binding Site of Elongation Factor-G. Med. Chem. Commun. 6, 2023–2028. 10.1039/C5MD00343A [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur G., Pavadai E., Wittlin S., Chibale K. (2018). 3D-QSAR Modeling and Synthesis of New Fusidic Acid Derivatives as Antiplasmodial Agents. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 58, 1553–1560. 10.1021/acs.jcim.8b00105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kigondu E. M., Wasuna A., Warner D. F., Chibale K. (2014). Pharmacologically Active Metabolites, Combination Screening and Target Identification-Driven Drug Repositioning in Antituberculosis Drug Discovery. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 22, 4453–4461. 10.1016/j.bmc.2014.06.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilic F. S., Erol K., Batu O., Yildirim E., Usluer G. (2002). The Effects of Fusidic Acid on the Inflammatory Response in Rats. Pharmacol. Res. 45, 265–267. 10.1006/phrs.2001.0946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita T., Kawano G., Tanaka N. (1968). Association of Fusidic Acid Sensitivity with G Factor in A Protein-Synthesizing System. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 33, 769–773. 10.1016/0006-291X(68)90226-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A., Jaitak V. (2019). Natural Products as Multidrug Resistance Modulators in Cancer. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 176, 268–291. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2019.05.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwofie S. K., Broni E., Asiedu S. O., Kwarko G. B., Dankwa B., Enninful K. S., et al. (2021). Cheminformatics-Based Identification of Potential Novel Anti-SARS-CoV-2 Natural Compounds of African Origin. Molecules 26, 406. 10.3390/molecules26020406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lage H. (2008). An Overview of Cancer Multidrug Resistance: A Still Unsolved Problem. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 65, 3145–3167. 10.1007/s00018-008-8111-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapham K., Novak J., Marroquin L. D., Swiss R., Qin S., Strock C. J., et al. (2016). Inhibition of Hepatobiliary Transport Activity by the Antibacterial Agent Fusidic Acid: Insights into Factors Contributing to Conjugated Hyperbilirubinemia/Cholestasis. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 29, 1778–1788. 10.1021/acs.chemrestox.6b00262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin D., Jing X., Chen Y., Liang Y., Lei M., Peng S., et al. (2017). Rifampicin Pre-treatment Inhibits the Toxicity of Rotenone-Induced PC12 Cells by Enhancing Sumoylation Modification of α-synuclein. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 485, 23–29. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.01.100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Zeng S., Meng X., Jiang X., Guo X. (2019). Antiviral Activity of Fusidate Sodium against Enterovirus A71. China Trop. Med. 19, 519–524. 10.13604/j.cnki.46-1064/r.2019.06.05 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd G., Atkinson T., Sutton P. M. (1988). Effect of Bile Salts and of Fusidic Acid on HIV-1 Infection of Cultured Cells. Lancet 1, 1418–1421. 10.1016/s0140-6736(88)92236-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J., Ni J. X., Wang J. A., Liu Z. Y., Shang K. L., Bi Y. (2019). Integration of Multiscale Molecular Modeling Approaches with the Design and Discovery of Fusidic Acid Derivatives. Future Med. Chem. 11, 1427–1442. 10.4155/fmc-2018-0567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra P. (2020). “Mycoses in Hematological Malignancies,” in Clinical Practice of Medical Mycology in Asia. Editor Arunaloke C. (Singapore: Springer Singapore; ), 119–134. 10.1007/978-981-13-9459-1_9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Di Marco R., Khademi M., Wallstrom E., Muhallab S., Nicoletti F., Olsson T. (1999). Amelioration of Experimental Allergic Neuritis by Sodium Fusidate (Fusidin): Suppression of IFN-γ and TNF-α and Enhancement of IL-10. J. Autoimmun. 13, 187–195. 10.1006/jaut.1999.0317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mindermann T., Zimmerli W., Rajacic Z., Gratzl O. (1993). Penetration of Fusidic Acid into Human Brain Tissue and Cerebrospinal Fluid. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 121, 12–14. 10.1007/BF01405176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman D. J., Cragg G. M. (2020). Natural Products as Sources of New Drugs over the Nearly Four Decades from 01/1981 to 09/2019. J. Nat. Prod. 83, 770–803. 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.9b01285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni J., Guo M., Cao Y., Lei L., Liu K., Wang B., et al. (2019). Discovery, Synthesis of Novel Fusidic Acid Derivatives Possessed Amino-Terminal Groups at the 3-Hydroxyl Position with Anticancer Activity. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 162, 122–131. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2018.10.059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicola A. M., Albuquerque P., Paes H. C., Fernandes L., Costa F. F., Kioshima E. S., et al. (2019). Antifungal Drugs: New Insights in Research & Development. Pharmacol. Ther. 195, 21–38. 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2018.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicoletti F., Beltrami B., Raschi E., Di Marco R., Magro G., Grasso S., et al. (1998). Protection from Concanavalin A (Con A)-Induced T Cell-dependent Hepatic Lesions and Modulation of Cytokine Release in Mice by Sodium Fusidate. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 110, 479–484. 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1997.4091423.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Njoroge M., Kaur G., Espinoza-Moraga M., Wasuna A., Dziwornu G. A., Seldon R., et al. (2019). Semisynthetic Antimycobacterial C-3 Silicate and C-3/C-21 Ester Derivatives of Fusidic Acid: Pharmacological Evaluation and Stability Studies in Liver Microsomes, Rat Plasma, and Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Culture. ACS Infect. Dis. 5, 1634–1644. 10.1021/acsinfecdis.9b00208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Öztas S., Kurutepe M., Adigüzel N., Acartürk E., Saraç S., Marasli D., et al. (2008). Vitro Efficacy of Fusidic Acid on Drug Resistant Strains of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis. Turk Toraks Dergisi 9, 109–112. [Google Scholar]

- Palmeira A., Sousa E., Vasconcelos M. H., Pinto M. M. (2012). Three Decades of P-Gp Inhibitors: Skimming through Several Generations and Scaffolds. Curr. Med. Chem. 19, 1946–2025. 10.2174/092986712800167392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park E., Kim D. K., Kim C. S., Kim J. S., Kim S., Chun H. S., et al. (2019). Protective Effects of Fusidic Acid against Sodium Nitroprusside-Induced Apoptosis in C6 Glial Cells. NeuroReport 30, 1222–1229. 10.1097/WNR.0000000000001354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavadai E., Kaur G., Wittlin S., Chibale K. (2017). Identification of Steroid-like Natural Products as Antiplasmodial Agents by 2D and 3D Similarity-Based Virtual Screening. Medchemcomm 8, 1152–1157. 10.1039/C7MD00063D [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne A. J., Neal L. M., Knoll L. J. (2013). Fusidic Acid Is an Effective Treatment against Toxoplasma Gondii and Listeria Monocytogenes In Vitro, but Not in Mice. Parasitol. Res. 112, 3859–3863. 10.1007/s00436-013-3574-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persidis A. (1999). Cancer Multidrug Resistance. Nat. Biotechnol. 17, 94–95. 10.1038/5289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reglodi D., Renaud J., Tamas A., Tizabi Y., Socías S. B., Del-Bel E., et al. (2017). Novel Tactics for Neuroprotection in Parkinson's Disease: Role of Antibiotics, Polyphenols and Neuropeptides. Prog. Neurobiol. 155, 120–148. 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2015.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riber D., Venkataramana M., Sanyal S., Duvold T. (2006). Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of Photoaffinity Labeled Fusidic Acid Analogues. J. Med. Chem. 49, 1503–1505. 10.1021/jm050583t [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieutord A., Bourget P., Troche G., Zazzo J. F. (1995). In Vitro Study of the Protein Binding of Fusidic Acid: A Contribution to the Comprehension of its Pharmacokinetic Behaviour. Int. J. Pharm. 119, 57–64. 10.1016/0378-5173(94)00369-G [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rizk M. A., El-Sayed S. A. E., Nassif M., Mosqueda J., Xuan X., Igarashi I. (2020). Assay Methods for In Vitro and In Vivo Anti-babesia Drug Efficacy Testing: Current Progress, Outlook, and Challenges. Vet. Parasitol. 279, 109013. 10.1016/j.vetpar.2019.109013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues T., Reker D., Schneider P., Schneider G. (2016). Counting on Natural Products for Drug Design. Nat. Chem. 8, 531–541. 10.1038/nchem.2479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salama A. A., AbouLaila M., Moussa A. A., Nayel M. A., El-Sify A., Terkawi M. A., et al. (2013). Evaluation of In Vitro and In Vivo Inhibitory Effects of Fusidic Acid on Babesia and Theileria Parasites. Vet. Parasitol. 191, 1–10. 10.1016/j.vetpar.2012.08.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salimova E. V., Mamaev A. G., Tret’yakova E. V., Kukovinets O. S., Mavzyutov A. R., Shvets K. Y., et al. (2018). Synthesis and Biological Activity of Cyanoethyl Derivatives of Fusidic Acid. Russ. J. Org. Chem. 54, 1411–1418. 10.1134/S1070428018090245 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Salimova E. V., Tret’yakova E. V., Parfenova L. V. (2019). Synthesis and Cytotoxic Activity of 3-amino Substituted Fusidane Triterpenoids. Med. Chem. Res. 28, 2171–2183. 10.1007/s00044-019-02445-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Salimova E. V., Magafurova A. A., Tretyakova E. V., Kukovinets O. S., Parfenova L. V. (2020). Indole Derivatives of Fusidane Triterpenoids: Synthesis and the Antibacterial Activity. Chem. Heterocycl Comp. 56, 800–804. 10.1007/s10593-020-02733-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders J. M., Monogue M. L., Jodlowski T. Z., Cutrell J. B. (2020). Pharmacologic Treatments for Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): A Review. JAMA 323, 1824–1836. 10.1001/jama.2020.6019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savelsbergh A., Rodnina M. V., Wintermeyer W. (2009). Distinct Functions of Elongation Factor G in Ribosome Recycling and Translocation. RNA 15, 772–780. 10.1261/rna.1592509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schou S. C., Riber D., Grue-Sørensen G. (2007). Synthesis of Radiolabelled Photolabile Fusidic Acid Analogues. J. Label Compd. Radiopharm. 50, 1260–1261. 10.1002/jlcr.1458 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shakurova E. R., Salimova E. V., Mescheryakova E. S., Parfenova L. V. (2019). One-pot Synthesis of Quaternary Pyridinium Salts and Tetrahydropyridine Derivatives of Fusidane Triterpenoids. Chem. Heterocycl Comp. 55, 1204–1210. 10.1007/s10593-019-02602-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shanika P. S. (2017). Semi-synthesis and Evaluation of Fusidic Acid Derivatives as Potential Antituberculosis Agents. Dissertation/master’s thesis. Cape Town (Western Cape): University of Cape Town. [Google Scholar]

- Singh A. K., Rana H. K., Pandey A. K. (2019). “Fungal-Derived Natural Product: Synthesis, Function, and Applications,” in Recent Advancement in White Biotechnology through Fungi. Editors Yadav A. N., Singh S., Mishra S., Gupta A. (New York, NY: Springer Cham; ), 229–248. 10.1007/978-3-030-14846-1_8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singh K., Kaur G., Shanika P. S., Dziwornu G. A., Okombo J., Chibale K. (2020). Structure-Activity Relationship Analyses of Fusidic Acid Derivatives Highlight Crucial Role of the C-21 Carboxylic Acid Moiety to its Anti-mycobacterial Activity. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 28, 115530. 10.1016/j.bmc.2020.115530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh V., Dziwornu G. A., Mabhula A., Chibale K. (2021). Rv0684/fusA1, an Essential Gene, Is the Target of Fusidic Acid and its Derivatives in Mycobacterium tuberculosis . ACS. Infect. Dis. 7, 2437–2444. 10.1021/acsinfecdis.1c00195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Still J. G., Clark K., Degenhardt T. P., Scott D., Fernandes P., Gutierrez M. J. (2011). Pharmacokinetics and Safety of Single, Multiple, and Loading Doses of Fusidic Acid in Healthy Subjects. Clin. Infect. Dis. 52, S504–S512. 10.1093/cid/cir174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnidge J. (1999). Fusidic Acid Pharmacology, Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 12, 23–34. 10.1016/S0924-8579(98)00071-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson D. N. (2014). Ribosome-Targeting Antibiotics and Mechanisms of Bacterial Resistance. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 12, 35–48. 10.1038/nrmicro3155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2020a). World Malaria Report 2020. Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240015791 (Accessed August 07, 2021).

- World Health Organization (2020b). World Tuberculosis Day 2020. Available at: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/336069/9789240013131-eng.pdf (Accessed August 07, 2021).

- Wu P. P., He H., Hong W. D., Wu T. R., Huang G. Y., Zhong Y. Y., et al. (2018a). The Biological Evaluation of Fusidic Acid and its Hydrogenation Derivative as Antimicrobial and Anti-inflammatory Agents. Infect. Drug Resist. 11, 1945–1957. 10.2147/IDR.S176390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X., Liang Y., Jing X., Lin D., Chen Y., Zhou T., et al. (2018b). Rifampicin Prevents SH-SY5Y Cells from Rotenone-Induced Apoptosis via the PI3K/Akt/GSK-3β/CREB Signaling Pathway. Neurochem. Res. 43, 886–893. 10.1007/s11064-018-2494-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaki H. (1965). Inhibition of Protein Synthesis by Fusidic and Helvolinic Acids, Steroidal Antibiotics. J. Antibiot. 18, 228–232. 10.11554/antibioticsa.18.5_228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youle M. S., Hawkins D. A., Lawrence A. G., Tenant-Flowers M., Shanson D. C., Gazzard B. G. (1989). Clinical, Immunological, and Virological Effects of Sodium Fusidate in Patients with AIDS or AIDS-Related Complex (ARC): An Open Study. J. Acquired Immune Defic. Syndr. 2, 59–62. 10.1007/BF01643625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zając-Spychała O., Skalska-Sadowska J., Wachowiak J., Szmydki-Baran A., Hutnik Ł., Matysiak M., et al. (2019). Infections in Children with Acute Myeloid Leukemia: Increased Mortality in Relapsed/Refractory Patients. Leuk. Lymphoma 60, 3028–3035. 10.1080/10428194.2019.1616185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao M., Gödecke T., Gunn J., Duan J. A., Che C. T. (2013). Protostane and Fusidane Triterpenes: A Mini-Review. Molecules 18, 4054–4080. 10.3390/molecules18044054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zida A., Bamba S., Yacouba A., Ouedraogo-Traore R., Guiguemdé R. T. (2017). Anti-Candida Albicans Natural Products, Sources of New Antifungal Drugs: A Review. J. Mycol. Med. 27, 1–19. 10.1016/j.mycmed.2016.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zink M. C., Uhrlaub J., DeWitt J., Voelker T., Bullock B., Mankowski J., et al. (2005). Neuroprotective and Anti-human Immunodeficiency Virus Activity of Minocycline. JAMA 293, 2003–2011. 10.1001/jama.293.16.2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]