Abstract

BACKGROUND

Schwannoma is a benign, encapsulated and slowly growing tumor originating from Schwann cells and is rarely seen in the peripheral nerve system. Typical symptoms are soreness, radiating pain and sensory loss combined with a soft tissue mass.

AIM

To evaluate pre- and postoperative symptoms in patients operated for schwannomas in the extremities and investigate the rate of malignant transformation.

METHODS

In this single center retrospective study design, all patients who had surgery for a benign schwannoma in the extremities from May 1997 to January 2018 were included. The location of the tumor in the extremities was divided into five groups; forearm, arm, shoulder, thigh and leg including foot. The locations of the tumor in the nerves were also categorized as either; proximal, distal, minor or major nerve. During the pre- and postoperative clinical evaluation, symptoms were classified as paresthesia, local pain, radiating pain, swelling, impairment of mobility/strength and asymptomatic tumors that were found incidentally (with magnetic resonance imaging). The patients were evaluated after surgery using the following categories: Asymptomatic or symptomatic patients (radiating and/or local pain) and those with complications. The follow up period was from the time of surgery until last examination of the particular physician. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to identify independent prognostic factors for postoperative significant symptoms at follow-up.

RESULTS

We identified 858 cases from the institutional pathology register. We excluded cases with duplicate diagnoses (n = 407), pathology not including schwannomas (n = 157), lesions involving the torso, spine and neck (n = 150) leaving 144 patients for further analysis. In this group 99 patients underwent surgery and there were five complications recorded: 2 infections (treated with antibiotics) and 3 nerve palsies (2 involving the radial nerve and one involving the median nerve) that recovered spontaneously. At the end of follow-up, 1.4 mo (range 0.5-76) postoperatively, we recorded a post-operative decrease in clinical symptoms: Local pain 76% (6/25), radiating pain 97% (2/45), swelling 20% (8/10). Symptoms of paresthesia increased by 2.8% (37/36) and there was no change in motor weakness before and after surgery 1% (1/1). Multivariate analysis showed that tumors located within minor nerves had a significantly higher prevalence of postoperative symptoms compared with tumors in major nerves (odds ratio: 2.63; confidence intervals: 1.22-6.42, P = 0.029). One patient with schwannoma diagnosed by needle biopsy was diagnosed to have malignant transformation diagnosed in the surgically removed tumor. No local recurrences were reported.

CONCLUSION

Surgery of schwannomas can be conducted with low risk of postoperative complications, acceptable decrease in clinical symptoms and risk of malignant transformation is low.

Keywords: Schwannoma, Extremities, Surgery, Removal, Symptoms, Outcome

Core Tip: Schwannoma is a benign slowly growing tumor which is most common in the central nerve system. Peripheral schwannomas can give symptoms as numbness, local- and radiating pain. Recent studies proves surgical excision can be made with low expectations for complications and a high rate of remission. Never the less, some patients show up with consisting and significant symptoms after surgery. Our study showed that location of tumor on the nerve is of importance when evaluating patients’ clinical symptoms post-operatively.

INTRODUCTION

Schwannomas are one of the most common benign tumors in the peripheral nervous system. They originate from Schwann cells and account for about 5% of all tumors in the upper extremity. The most common presentation of a schwannoma is as a slowly growing, non-invasive single mass with a diameter ranging from 10–250 mm[1]. Patients present most commonly in their third to fifth decades of life with no racial and gender difference[2-5]. Symptoms described in the literature are mainly sensory as radiating pain, local irritation and sensation of a heavy mass. Primary motor involvement has also been described leading to paresis and eventually paralysis[6].

Schwannomas is commonly diagnosed using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) but ultrasound and clinical examination is also well described[7,8].

Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors are rarely reported to have arisen from a primary schwannomas but when this occurs the reason ought to be malignant transformation of Schwann cells[9]. There are few studies documenting the malignant transformation of schwannomas[10,11]. The aim of our study was to describe the pre- and postoperative symptoms in patients treated surgically for benign schwannomas and examine whether tumor size, anatomical location or specific nerve location had an impact on the clinical symptoms prior to and after surgery. We also investigated the rate of malignant transformation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In this single center retrospective study design, all patients who had surgery due to benign schwannoma from May 1997 to January 2018 were included in the study. Patient data were collected both from our institutional pathology database and patient files.

To make sure no schwannomas were missed in the patients’ data files for the study, we conducted a search in the pathology register that included all nerve sheath tumors. We found 858 cases including schwannoma, neurofibroma, neuroma and malignant schwannoma (ICD Codes D36.10; D36.11; D36.17; C47).

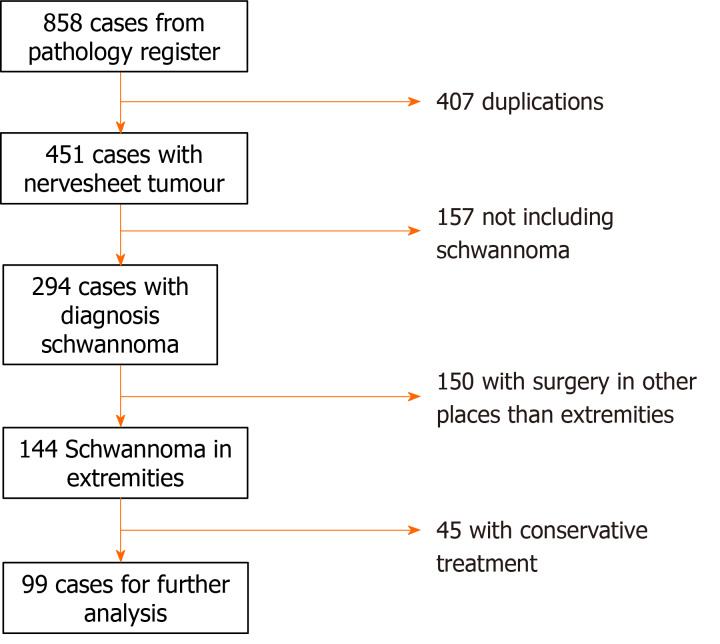

We excluded the following: Duplications of patients (n = 407), pathology other than solitary schwannoma (Schwannomatosis, Neuromas and Neurofibromas) (n = 157), surgery performed in the torso, spine, neck, pelvis and retroperitoneum (n = 150) and conservatively treated schwannomas (n = 45) thus leaving 99 patients treated surgically for further analyses (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart for exclusion.

By using data from patient files, we analyzed age, sex, data on nerve involvement including site and branch involved, pre- and postoperative symptoms and complications. We measured the size of the tumor by examining the patient’s pre-operative MRI. Post-operative symptoms and objective findings were recovered from patient records. Patients were not followed up further if they were symptom free at the first postoperative examination at two weeks. Symptoms were classified as either paresthesia, local pain, radiating pain, swelling, motor involvement and no symptoms (incidental MRI-finding).

The patients who were symptomatic at end of follow-up were followed up with a custom-made questionnaire January 2018 investigating symptoms before and after surgery.

Those patients who reported new symptoms, recurrence of a mass or unsatisfactory results were offered an MRI-scanning and a follow-up to rule out a recurrence or malign transformation of the schwannoma.

The location of the tumor in the extremities was divided into five groups; forearm, upper arm, shoulder, thigh and leg (including foot). The location of the tumor in the nerve was categorized as either proximal, distal, minor nerve or major nerve. Proximal locations were defined as upper arm, thigh and shoulder and distal locations as leg and forearm. Nerve branches were classified as follows: Minor nerve was defined as schwannoma on muscular or terminal branch and major nerve as tumors located on either ischial-, femoral-, peroneal- or tibia nerves in the lower limb and axillary-, radial, ulnar- or median nerves in the upper limb.

Surgical complications were categorized as infection (superficial or deep), transient paresis and reoperation (all causes). Symptoms categorized as significant were motor paresis and pain (both local and radiating).

The study was cleared by the National Patient Safety Authority (Case numbers 3-3013-1550/1 and 3-3013-1550/2) and by the Data Protection Agency of the Capital Region of Denmark (number: RH-2016-144, I-Suite number.: 04677).

Surgical procedure

A preoperative MRI was used to plan excision and surgical approach. The affected nerve was exposed visualizing the tumor in the center with the proximal and distal healthy nerve ends. By using loupe magnification, nerve fascicles passing outside the tumor were identified and tested with a nerve stimulator and protected. The capsule of the tumor was incised away from nerve tissue. With a blunt dissector the tumor was loosened and removed when possible. If the tumor was attached to nerve tissue a swab was used to loosen the tumor under testing with the nerve stimulator. After removal, the tumor was sent to pathological examination. Hemostasis was secured and the wound closed with vicryl suture in fascia and subcutaneous layers and skin (intracutaneous). All patients were mobilized immediately and discharged from the hospital within 24 h.

Statistics

All data are presented as median values together with total range.

Univariate logistic regression analysis was carried out in order to identify predictable factors for significant symptoms at follow-up. Patients with significant symptoms at follow up were compared with those without symptoms. Median values were defined as cut off for both size (24 mm) and age (53 years). The parameters compared were anatomical location and location on a minor or major nerve. A multivariate analysis was performed to identify independent prognostic factors for significant postoperative symptoms. In multivariate analysis no elimination of parameters was performed.

We assumed variables mentioned above were normally distributed. No substitution was made for missing data points. The results of the logistic regression analyses were presented as the odds ratio (OR) together with the 95% confidence intervals (CI) and P values below 0.05 are considered significant.

RESULTS

We included 99 patients with the baseline characteristics shown in Table 1. There were 51 men and 49 women. Median age was 53 (17-89) years and median postoperative follow-up was 0.5 (0.5-76) mo.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics (n = 99)

| Category |

|

| Age, median (range) | 53 (17–89) |

| Male, n (%) | 51 |

| Tumor size (range) (mm) | 24 (5–175) |

| Preoperative symptoms | Local pain 25% |

| Radiating pain 45% | |

| Swelling 10% | |

| Motor weakness 1% | |

| Paresthesia 36% | |

| Nerve branch | Major 51 % |

| Anatomical localization of tumor | Distal 44% |

Preoperative symptoms were observed in 86% (85/99) of the operated patients, the remaining tumors were found incidentally on an unrelated MRI.

We recorded 5 complications: 1 superficial infection (treated with oral antibiotics), 1 reoperation (attempted arthroscopic excision was unsuccessful), and 3 transient nerve palsies (two involving radial and one involving median nerve).

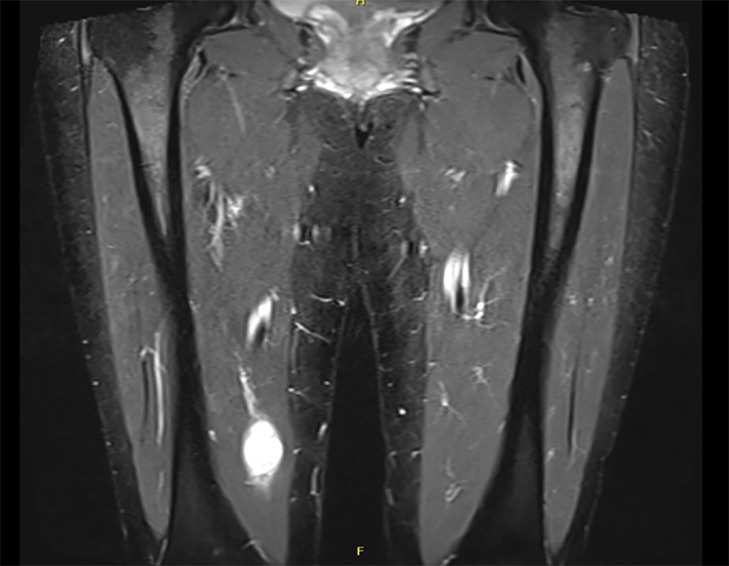

At the end of follow-up, we registered a post-operative decrease in symptoms: local pain 76% (6/25), radiating pain 97% (2/45), swelling 20% (8/10). Symptoms of paresthesia increased by 3% (37/36) and there was no change in motor weakness before and after surgery 1% (1/1). One patient with schwannoma diagnosed by needle biopsy had malignant transformation to Neurofibrosarcoma verified after final surgery (Figure 2). No local recurrences were reported.

Figure 2.

Patient with needle biopsy first diagnosed with schwannoma and after final biopsy showed to have a neurofibrosarcoma.

Univariate analysis showed a tendency (OR: 2.19; 95%CI: 0.97-5.09; P = 0.063) towards a higher degree of significant postoperative symptoms if a minor rather than a major nerve was involved. Multivariate analysis showed that tumor location on a minor nerve had a statistically significant higher risk of having significant symptoms after surgery (OR: 2.63; 95%CI: 1.22-6.42; P = 0.029) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Predictive factors for consisting symptoms after surgical removal of schwannomas

|

Univariate

|

Multivariate

|

Reference

|

|||

|

|

OR (CI)

|

P

value

|

OR (CI)

|

P

value

|

|

| Localization | 1.48 (0.65-3.40) | 0.354 | 1.61 (0.69-3.85) | 0.276 | Proximal |

| Nerve | 2.19 (0.97-5.09) | 0.063 | 2.63 (1.22-6.42) | 0.029 | Minor |

| Size | 0.84 (0.37-1.90) | 0.680 | 0.91 (0.39-2.13) | 0.828 | < 24 mm |

| Age | 0.65 (0.29-1.46) | 0.301 | 0.57 (0.23-1.35) | 0.205 | < 53 yr |

OR: Odds ratio; CI: Confidence interval.

Tumor location (proximal or distal), size (24 mm cut off) and age (53 years cut off) had no influence on the surgical outcomes.

Our letter with the questionnaire was sent out to 98% (97/99) of the patients and in total 44% (44/99) replied. Out of these 18 got a second MRI and one patient had an ultrasound examination as she had contraindication against MRI (because of an ICD-unit). None of the patients who had a second scan had local recurrence or malignant transformation. All the patients whom reported symptoms had scar tissue and adherence mass around the operative field on MR scanning.

DISCUSSION

Our report investigated symptoms and remission rate after surgical removal of peripheral benign schwannomas in the extremities. The most significant finding was that surgical removal of tumors involving terminal nerve branches showed an increased risk of getting significant symptoms (local or radiating pain) compared to tumors originating from major nerve branches.

We decided to exclude those who had more than one schwannoma and Schwannomatosis as these patients often have many operations, larger operation area, multiple affected nerves and clinical results regarding symptoms after operation can be difficult to categorize. Gosk et al[12] included patients with more than one schwannoma[12]. Four of their patients had a total of 14 tumors removed and due to the reasons mentioned above, we believe this complicates analysis of the clinical outcome and could contribute to bias regarding the post-surgical evaluation.

Other articles have investigated complications after surgery of schwannomas and have reported numbers as high as 76.6%[13] and 42.7%[14] where they define loss of sensibility immediately after operation as a complication, even though it is often just transient.

We choose not to include loss of sensibility after surgery as a complication, as we do not consider it to be an adverse effect when studies showed that loss of sensibility had a remission rate of 73%-100%[6,13,15,16]. This difference in the definition made our rate of complications remarkably lower.

Several studies have shown an incidence of neurological deficits after surgery ranging between 1.5% and 80%[6,13,15,17-20]. One reason for this may be the vast variation in follow-up periods. Another contributing factor could be the differences in the definition of neurological deficits. We did not define neurological deficits as a combined group but instead divided it into either local pain, radiating pain, paresis and/or paresthesia. The first two subgroups (local pain and radiating pain) showed a decrease in symptoms with time but the last group (paresthesia) actually showed an increase after surgery. This highlights the importance of recording different components of preoperative deficits before comparing this to changes of neurological status after surgery. Combining sensory and motor deficits could compromise evaluation of outcomes.

Previous reports have shown that the incidence of postoperative complications was significantly higher in patients with larger tumors, tumors on the upper extremities[6,13,15], younger age[6] and tumors originating from the ulnar nerve[21], but these features were not found to be risk factors in our study.

Other studies report that surgery for schwannomas originating from unidentified terminal branches in the muscle or in the skin does not cause postoperative neurological symptoms[22]. Our study proved that this might not be the case as many of our patients who had excisions of tumors involving terminal nerve branches had significant postoperative symptoms.

One possible reason for our finding of higher risk of symptoms after surgery in terminal branches, may be due to the lower soft tissue coverage distally than proximally. Adani et al[17] described this phenomenon but found that tumors lying distally and in the upper limb gave more symptoms after surgery, something we could not conclude in our report.

The limitations of our study are inherent in its retrospective design. Also data files show a vast number of surgeons operating schwannoma, and also a great discrepancy in the charts describing clinical symptoms at final exam. The follow-up period was varying among patients and most were relatively short.

CONCLUSION

The authors of this study found evidence for reduction of pre-operative symptoms especially regarding local pain and radiating pain after surgical excision of solitary schwannomas of the extremities and opine that this balances the risks of operative treatment.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

Schwannomas are one of the most common benign tumors in the peripheral nervous system and symptoms described in the literature are mainly sensory as radiating pain, local irritation, and sensation of a heavy mass, while primary motor involvement leading to paresis is uncommon.

Research motivation

Surgical removal of schwannomas in the peripheral nervous system is by many surgeons considered a high risk procedure with surgery directly on peripheral nerves and since the literature regarding the clinical results that can be expected after this procedure is relatively sparse, we found it of interest to examine the postoperative results after this procedure.

Research objectives

To evaluate the pre- and postoperative symptoms in patients treated surgically for benign schwannomas and examine whether tumor size, anatomical location or specific nerve location had an impact on the clinical symptoms prior to and after surgery. Finally, we also aimed to investigate the rate of malignant transformation.

Research methods

All patients who had surgery due to benign schwannomas from May 1997 to January 2018 at our institution were identified and included in the study. We registered preoperative baseline data and postoperative symptoms and objective findings were recovered from patient records and a questionnaire. Patients that reported new symptoms, recurrence of a mass, or unsatisfactory results were offered an magnetic resonance imaging-scanning and a follow-up to rule out a recurrence or malignant transformation of the tumor.

Research results

At the end of follow-up we recorded a significant post-operative decrease in clinical symptoms such as local pain and radiating pain. Multivariate analysis showed that tumors located within minor nerves had a significantly higher prevalence of postoperative symptoms compared with tumors in major nerves. One patient with schwannoma diagnosed initially by needle biopsy was diagnosed to have malignant transformation diagnosed in the surgically removed tumor. No local recurrences were reported.

Research conclusions

Surgery of schwannomas can be conducted with low risk of postoperative complications, acceptable decrease in clinical symptoms and risk of local recurrence and malignant transformation is low.

Research perspectives

Future studies should provide prospective data and especially give more detailed information for those few patients who got worsening of their pre-operative symptoms and give further information about the specific characteristics of the patient and the tumor that may affect the outcome of the surgical tumor removal.

Footnotes

Institutional review board statement: The study was reviewed and approved by the University of Copenhagen Review Board, No. RH-2016-144.

Informed consent statement: All study participants or their legal guardian provided informed written consent about personal and medical data collection prior to study enrolment.

Conflict-of-interest statement: All authors have nothing to disclose.

STROBE statement: The authors have read the STROBE Statement-checklist of items, and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the STROBE Statement-checklist of items.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Peer-review started: February 5, 2021

First decision: May 3, 2021

Article in press: September 8, 2021

Specialty type: Orthopedics

Country/Territory of origin: Denmark

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Ertan A S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: A P-Editor: Xing YX

Contributor Information

Andreas Saine Granlund, Musculoskeletal Tumor Section, Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Copenhagen University Hospital, Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen 2100, Denmark. andreas.saine@gmail.com.

Michala Skovlund Sørensen, Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Copenhagen University Hospital, Copenhagen 2200, Denmark.

Claus Lindkær Jensen, Musculoskeletal Tumor Section, Department of Orthopedic Surgery, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen 2100, Denmark.

Birthe Højlund Bech, Department of Radiology, Rigshospitalet, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen 2100, Denmark.

Michael Mørk Petersen, Musculoskeletal Tumor Section, Department of Orthopedic Surgery, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen 2100, Denmark.

Data sharing statement

Statistical code and dataset available from the corresponding author at andreas.saine@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Ogose A, Hotta T, Morita T, Yamamura S, Hosaka N, Kobayashi H, Hirata Y. Tumors of peripheral nerves: correlation of symptoms, clinical signs, imaging features, and histologic diagnosis. Skeletal Radiol. 1999;28:183–188. doi: 10.1007/s002560050498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goyal A, Belzberg AJ. Benign and malignant tumors of peripheral nerve. Texas: Elsevier 2017: 1587–1619. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gosk J, Zimmer K, Rutowski R. Peripheral nerve tumours--diagnostic and therapeutical basics. Folia Neuropathol. 2004;42:31–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhou J, Man XY, Zheng M, Cai SQ. Multiple plexiform schwannoma of a finger. Eur J Dermatol. 2012;22:149–150. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2011.1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pilavaki M, Chourmouzi D, Kiziridou A, Skordalaki A, Zarampoukas T, Drevelengas A. Imaging of peripheral nerve sheath tumors with pathologic correlation: pictorial review. Eur J Radiol. 2004;52:229–239. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2003.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Siqueira MG, Socolovsky M, Martins RS, Robla-Costales J, Di Masi G, Heise CO, Cosamalón JG. Surgical treatment of typical peripheral schwannomas: the risk of new postoperative deficits. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2013;155:1745–1749. doi: 10.1007/s00701-013-1818-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Höglund M, Muren C, Engkvist O. Ultrasound characteristics of five common soft-tissue tumours in the hand and forearm. Acta Radiol. 1997;38:348–354. doi: 10.1080/02841859709172081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hughes DG, Wilson DJ. Ultrasound appearances of peripheral nerve tumours. Br J Radiol. 1986;59:1041–1043. doi: 10.1259/0007-1285-59-706-1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gupta G, Mammis A, Maniker A. Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2008;19:533–543, v. doi: 10.1016/j.nec.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Louis DS. Peripheral nerve tumors in the upper extremity. Hand Clin. 1987;3:311–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Idler RS. Benign and malignant nerve tumors. Hand Clin. 1995;11:203–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gosk J, Gutkowska O, Urban M, Wnukiewicz W, Reichert P, Ziółkowski P. Results of surgical treatment of schwannomas arising from extremities. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:547926. doi: 10.1155/2015/547926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim SM, Seo SW, Lee JY, Sung KS. Surgical outcome of schwannomas arising from major peripheral nerves in the lower limb. Int Orthop. 2012;36:1721–1725. doi: 10.1007/s00264-012-1560-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hirai T, Kobayashi H, Akiyama T, Okuma T, Oka H, Shinoda Y, Ikegami M, Tsuda Y, Fukushima T, Ohki T, Ishibashi Y, Sawada R, Goto T, Tanaka S. Predictive factors for complications after surgical treatment for schwannomas of the extremities. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2019;20:166. doi: 10.1186/s12891-019-2538-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Park MJ, Seo KN, Kang HJ. Neurological deficit after surgical enucleation of schwannomas of the upper limb. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2009;91:1482–1486. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.91B11.22519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abe K, Takeuchi A, Yamamoto N, Hayashi K, Tada K, Miwa S, Inatani H, Aoki Y, Higuchi T, Tsuchiya H. Symptomatic small schwannoma is a risk factor for surgical complications and correlates with difficulty of enucleation. Springerplus. 2015;4:751. doi: 10.1186/s40064-015-1547-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Adani R, Baccarani A, Guidi E, Tarallo L. Schwannomas of the upper extremity: diagnosis and treatment. Chir Organi Mov. 2008;92:85–88. doi: 10.1007/s12306-008-0049-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kang HJ, Shin SJ, Kang ES. Schwannomas of the upper extremity. J Hand Surg Br. 2000;25:604–607. doi: 10.1054/jhsb.2000.0472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sawada T, Sano M, Ogihara H, Omura T, Miura K, Nagano A. The relationship between pre-operative symptoms, operative findings and postoperative complications in schwannomas. J Hand Surg Br. 2006;31:629–634. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsb.2006.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Donner TR, Voorhies RM, Kline DG. Neural sheath tumors of major nerves. J Neurosurg. 1994;81:362–373. doi: 10.3171/jns.1994.81.3.0362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fujibuchi T, Miyawaki J, Kidani T, Miura H. Risk factors for neurological complications after operative treatment for schwannomas. J Clin Neurosci. 2017;46:136–140. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2017.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kwon BC, Baek GH, Chung MS, Lee SH, Kim HS, Oh JH. Intramuscular neurilemoma. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2003;85:723–725. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Statistical code and dataset available from the corresponding author at andreas.saine@gmail.com.