Abstract

BACKGROUND

High-sensitivity cardiac troponin (hs-cTn) levels are frequently elevated in elderly patients presenting to the emergency department for non-cardiac events. However, most studies on the role of elevated hs-cTn in elderly populations have investigated the prognostic value of hs-cTn in patients with a specific diagnosis or have assessed the relationship between hs-cTn and comorbidities.

AIM

To investigate the in-hospital prognosis of consecutive elderly patients admitted to the Internal Medicine Department with acute non-cardiac events and increased hs-cTnI levels.

METHODS

In this retrospective study, we selected patients who were aged ≥ 65 years and admitted to the Internal Medicine Department of our hospital between January 2019 and December 2019 for non-cardiac reasons. Eligible patients were those who had hs-cTnI concentrations ≥ 100 ng/L. We investigated the independent predictors of in-hospital mortality by multivariable logistic regression analysis.

RESULTS

One hundred and forty-six patients (59% female) were selected with an age range from 65 to 100 (mean ± SD: 85.4 ± 7.61) years. The median hs-cTnI value was 284.2 ng/L. For 72 (49%) patients the diagnosis of hospitalization was an infectious disease. The overall in-hospital mortality was 32% (47 patients). Individuals who died did not have higher hs-cTnI levels compared with those who were discharged alive (median: 314.8 vs 282.5 ng/L; P = 0.565). There was no difference in mortality in patients with infectious vs non-infectious disease (29% vs 35%). Multivariable analysis showed that age (OR 1.062 per 1 year increase, 95%CI: 1.000-1.127; P = 0.048) and creatinine levels (OR 2.065 per 1 mg/dL increase, 95%CI: 1.383-3.085; P < 0.001) were the only independent predictors of death. Mortality was 49% in patients with eGFR < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2.

CONCLUSION

Myocardial injury is a malignant condition in elderly patients admitted to the hospital for non-cardiac reasons. The presence of severe renal impairment is a marker of extremely high in-hospital mortality.

Keywords: Internal medicine, High sensitivity troponin, Elderly, Non-cardiac admissions, Renal function, Prognosis

Core Tip: Many reports have shown that there is an association between acute myocardial injury and adverse outcomes in almost every clinical setting. However, data from consecutive elderly patients admitted to Internal Medicine Departments with acute non-cardiac events are limited. We found that these patients are at high risk of in-hospital death and that age and renal dysfunction were the only independent predictors of death. Elderly patients with acute myocardial injury from non-cardiac cause and chronic kidney disease stages IV or V had an extremely high risk (approximate 50%) of in-hospital death.

INTRODUCTION

Since the introduction of high-sensitive cardiac troponin (hs-cTn) assays, troponin testing has been used in a broad spectrum of patients to detect minor myocardial injury[1,2]. A variety of non-cardiac clinical conditions is accompanied by “troponinemia”[2,3] and many reports have investigated the association between serum hs-cTn concentrations and adverse outcomes in almost every clinical setting[4-6].

Hs-cTn levels increase over time in asymptomatic elderly individuals[7,8]. Moreover, they are frequently elevated in elderly patients presenting to the emergency department for non-cardiac events[9]. However, the 99th centile for the hospital population is not well defined and varies depending on the clinical setting, age and location when the test is requested[9-13]. Most studies on the role of elevated hs-cTn in elderly populations have investigated the prognostic value of hs-cTn in patients with a specific diagnosis or have assessed the relationship between hs-cTn and comorbidities[14-16].

The objective of this study was to investigate: (1) The in-hospital survival of consecutive elderly patients presenting to the emergency department with acute non-cardiac events, elevated hs-cTnI levels and admitted to the Internal Medicine Department; and (2) The independent predictors (i.e., comorbidities) of in-hospital mortality.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design and population

We conducted a retrospective observational study at the University Hospital of Ioannina in Greece. The study protocol conformed to the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the institutional ethics committee.

First, we searched the electronic medical records and we selected patients who were aged ≥ 65 years, admitted to the Internal Medicine Department between January 2019 and December 2019, and had hs-TnI levels ≥ 100 ng/L. Then, the paper medical records of the included patients were also reviewed. In our tertiary hospital elderly patients presenting with acute coronary syndromes or other acute cardiac events are admitted exclusively in the Cardiology Department. Additionally, all patients with a final diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction (based on serial troponin measurements, symptoms, and electrocardiogram) after admission were excluded from the study. Patients on hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis were also excluded.

Demographic, clinical and biochemical data were extracted from patient records. Serum creatinine at presentation was used to calculate the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) using the modification of diet in renal disease study equation[17]. High-sensitivity-cTnI was measured using two-site immunoenzymatic (“sandwich”) assay (Beckman Coulter, Inc. Brea, CA, United States). The assay’s 99th centile is 19.8 ng/L for men and 11.6 ng/L for women according to the manufacturer. However, troponin concentrations and the 99th percentile upper reference limits (URL) depend on several other factors including age and ethnicity/race[18].

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as means ± SD or median (interquartile range) as appropriate. Deviation of continuous variables from the normal distribution was tested using the Shapiro-Wilk test (for a chosen alpha level of 0.05). The student’s t-test and the Mann-Whitney test were used to compare normally and not normally distributed data, respectively. Only the first hs-cTnI measurement ≥ 100 ng/L of the included patients was considered for the analysis, and log transformation was also used for troponin values (because of non-normal distribution with positive skew). Categorical data were presented as counts and percentages and were compared using the χ2 or the Fischer’s exact test as appropriate. Correlation between continuous variables was determined with the Pearson’s correlation coefficient. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was performed to evaluate the diagnostic performance of parameters for predicting in-hospital death. We performed binary logistic regression analysis to identify independent predictors of in-hospital death. A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant and all tests were two-sided. Statistical analysis was performed with the SPSS/PC (version 22.0, IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, United States) software package.

RESULTS

During the study period (January 2019 to December 2019), 146 patients (59% female) fulfilled our inclusion criteria. Patient age ranged from 65 years to 100 years (median: 87, mean ± SD: 85.4 ± 7.61). There was a substantial burden of comorbidities: 53 (36%) patients had diabetes mellitus, 38 (26%) coronary artery disease, 64 (44%) atrial fibrillation, and 46 (32%) chronic kidney disease (CKD). For 72 (49%) patients the diagnosis of hospitalization was an infectious disease. The second most commonly diagnosis was stroke (15 patients, 10%). Eleven patients (8%) were admitted due to gastrointestinal causes, 8 (5%) due to explained or unexplained falls, 7 (5%) due to pulmonary embolism, 6 (4%) due to severe anemia or pancytopenia, 5 (3%) due to “senility”, 4 (3%) due to hypoglycemia or hyperglycemia, 4 (3%) due to cancer, and 14 (10%) due to other causes.

The median hs-cTnI value was 284.25 ng/L (interquartile range 553.4), while the mean was 946.4 (± 2336.07) ng/L. High-sensitivity-cTnI was correlated with creatinine levels (r = 0.169, P = 0.042) and eGFR (r = -0.240, P = 0.004).

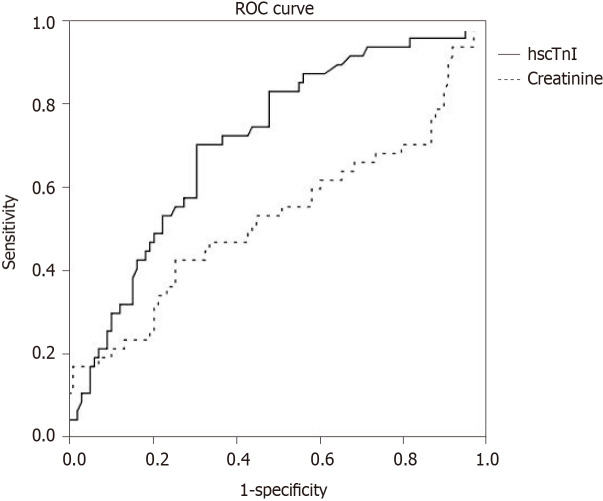

The overall in-hospital mortality was 32% (47 patients). Differences between patients who died in-hospital and those who were discharged alive are shown in Table 1. Individuals who died did not have significantly higher hs-cTnI levels (median: 314.8 vs 282.5 ng/L; Mann-Whitney U test, P = 0.565). There were no significant differences in mortality according to diagnosis (infectious vs non-infectious disease: 29% vs 35%), gender (males vs females: 35% vs 30%), diabetes (30% vs 33%), history of coronary artery disease (32% vs 32%), and atrial fibrillation (28% vs 35%). Mortality was higher among patients with known CKD (52% vs 23%, P = 0.001). Moreover, individuals who died had higher creatinine levels (2.10 ± 1.03 vs 1.66 ± 0.95 mg/dL, P = 0.008) and lower eGFR (35.32 ± 19.85 vs 47.17 ± 24.22 mL/min/1.73 m2, P = 0.002). In ROC analysis, the area under the curves was 0.527 for hs-cTnI, and 0.711 for creatinine (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Differences between patients who died in-hospital and those who were discharged alive

|

|

Patients who died (n = 47)

|

Discharged alive (n = 99)

|

P

value

|

| Age (yr), mean ± SD | 87.5 ± 5.3 | 83.4 ± 8.3 | 0.001 |

| Gender, n (%) | 0.59 | ||

| Female | 26 (30) | 60 (70) | |

| Male | 21 (35) | 39 (65) | |

| History of CAD, n | 12 | 26 | 1 |

| Atrial fibrillation/flutter, n | 18 | 46 | 0.38 |

| Renal function, n (%) | |||

| Known history of CKD | 24 (52) | 22 (48) | 0.001 |

| No history of CKD | 23 (23) | 77 (77) | |

| Creatinine levels, mg/dL | 2.10 (1.03) | 1.66 (0.95) | 0.008 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2), mean ± SD | 35.32 ± 19.85 | 47.17 ± 24.22 | 0.002 |

| On antihypertensive therapy, n | 28 | 74 | 0.082 |

| Diabetes Mellitus, n | 16 | 37 | 0.69 |

| On statin therapy, n | 19 | 45 | 0.6 |

| Diagnosis on admission, n (%) | 0.86 | ||

| Infectious diseases | 21 (31) | 46 (69) | |

| Non-infectious diseases | 26 (33) | 53 (67) | |

| CRP (mg/L), mean ± SD | 178.16 ± 130.81 | 154.27 ± 125.30 | 0.26 |

| hs-TnI (ng/L) | |||

| Median | 314.8 | 282.5 | 0.57 |

| Log-hsTnI, mean ± SD | 2.57 ± 0.57 | 2.59 ± 0.42 | 0.89 |

CAD: Coronary artery disease; CKD: Chronic kidney disease; eGFR: Estimated glomerular filtrated rate; SD: Standard deviation; CRP: C-reactive protein; hs-cTnI: High sensitive cardiac troponin I; Log: Logarithm 10.

Figure 1.

The area under the curves in receiver operating characteristic analysis. ROC: Receiver operating characteristic; hs-cTnI: High-sensitivity cardiac troponin I.

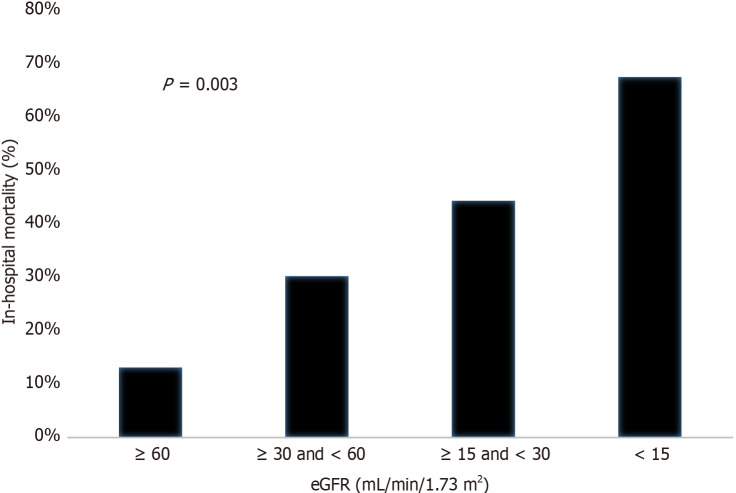

Multivariable analysis showed that age (OR 1.062 per 1 year increase, 95%CI: 1.00-1.13; P = 0.048) and creatinine levels (OR 2.07 per 1 mg/dL increase, 95%CI: 1.38-3.09; P < 0.001) were the only independent predictors of death. When renal function was estimated as eGFR, it was also a significant independent predictor of mortality (OR 1.04 per 1 mL/min/1.73 m2 decrease, 95%CI: 1.01-1.06; P = 0.001). Figure 2 shows the percentages of patients who died in-hospital according to the CKD stages. Mortality was 49% in patients with severe CKD (eGFR < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2).

Figure 2.

The percentages of patients who died in-hospital according to the chronic kidney disease stages.

DISCUSSION

We performed a retrospective investigation of in-hospital mortality in elderly patients admitted to the Internal Medicine Department with non-acute cardiac events and elevated hs-cTnI levels. Our major findings are that (1) these patients were at high risk of in-hospital death; (2) age and renal dysfunction were the only independent predictors of death among the parameters assessed; and (3) patients who died did not have higher hs-cTnI levels compared with those who were discharged alive.

Previous studies have reported that hs-cTnI concentrations and their 99th percentile strongly depend on the characteristics of the population being assessed[7] and that more than 20% of elderly inpatients may have hs-TnI levels above URL[11]. Advancing age and decreasing eGFR were shown to be independent predictors of hs-TnI concentration greater than the recommended URL[11]. Moreover, the 99th percentile of elderly inpatients (after excluding participants diagnosed as having acute myocardial infarction) may be 10 times higher than the recommended URL[11]. Eggers et al[7] reported the 99th percentile for hs-cTnI near our cut-off value (i.e., 100 ng/L) regarding individuals with age distribution and cardiac history similar to our study group.

The high in-hospital mortality in patients with high troponin levels admitted for non-cardiac causes is in line with previously published studies[5,6,12,19]. The relatively higher mortality in our study could be mainly explained by differences in baseline characteristics of the included patients, since our study population was older, had more frequently a history of CKD and higher creatinine levels (and thus, lower eGFR)[5,6,12,19]. We showed that age and renal function were the only independent predictors of in-hospital mortality in elderly patients admitted with high hs-cTnI levels and non-cardiac causes in the Internal Medicine Department. It is worth noting that the majority of prior research has been conducted in patients with infectious diseases, while in our unselected elderly study group, 50% of the elderly inpatients suffered from other diseases. However, there were no significant differences regarding mortality according to the cause of admission (infectious vs non-infectious disease) and no differences regarding the CRP concentrations between patients who died and patients who were discharged alive.

Our study showed that although elderly patients with non-cardiac events and hs-cTnI ≥ 100 ng/L have a high risk of in-hospital death, individuals who died did not have higher hs-cTnI levels compared with those who were discharged alive. Similarly, Frencken et al[5] also showed that troponin release beyond hs-cTnI plasma concentrations of approximate 100 ng/L does not carry an additional mortality risk in patients with sepsis. This non-linear relationship between troponin levels and mortality may be present even in patients with revascularized acute coronary syndromes[12]. The nonlinear relationship with mortality is difficult to explain. It is possible that in patients with non-cardiac acute events, the presence of myocardial injury (and not the extent of injury) maybe a marker of increased mortality. This hypothesis is supported from our ROC analysis, since the area under the curve for hs-cTnI was approximately 0.5, thereby indicating that the level of the troponin (the level of myocardial injury) has no discrimination capacity for further distinguish the risk of in-hospital death.

Cardiac troponin concentrations are often increased in CKD patients[20]. Although the reasons are not clear, higher troponin values in CKD patients are considered to be primarily caused by chronic myocardial injury, and thus troponin release to the circulation, and secondarily by decreased clearance. Miller-Hodges et al[21] evaluated hs-TnI testing in patients with suspected acute coronary syndrome with and without renal impairment. They reported that patients with elevated troponin and renal impairment had a greater risk for cardiac events at 1 year. Although previous studies have investigated the prognostic role of troponins in elderly patients[7,8,12], data regarding the evaluation of CKD in elderly patients with non-cardiac admissions and elevated hs-Tn measurements are sparse. We report an extremely high risk of in-hospital death among elderly patients with renal impairment admitted to the hospital for non-cardiac causes with elevated hs-cTnI levels. Elderly inpatients with CKD stages IV or V had a risk of approximate 50% for in-hospital death. This may emphasize the need for more aggressive monitoring and treatment in this group in order to avoid complications and death.

Our study had several limitations. First, all retrospective studies using electronic/paper medical records have inherent methodological problems[22]. Second, we did not use a control group (e.g., patients with “normal” hs-cTnI levels) for comparison purposes. Third, other potential prognostic indices (e.g., brain natriuretic peptides) were available only in a very small number of patients, hence we did not include them in the analysis. Finally, although in almost all the cases cardiology examination was performed, in clinical practice it is often difficult to exclude from the diagnosis an acute coronary syndrome, especially in elderly patients with non-specific symptoms.

CONCLUSION

Myocardial injury is a malignant condition in elderly patients admitted to the hospital for non-cardiac reasons and indicates poor overall prognosis. The presence of severe renal impairment remains as an independent marker of extremely high in-hospital mortality in this selected patient group.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

Many reports have shown that there is an association between acute myocardial injury and adverse outcomes in almost every clinical setting.

Research motivation

Data from consecutive elderly patients admitted to the Internal Medicine Department with acute non-cardiac events and acute myocardial injury are limited.

Research objectives

To investigate: (1) The in-hospital survival of consecutive elderly patients presenting to the emergency department with acute non-cardiac events, elevated high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I (hs-cTnI) levels and admitted to the Internal Medicine Department; and (2) The independent predictors (i.e., comorbidities) of in-hospital mortality.

Research methods

This was a single centre, retrospective, observational study, involving 146 elderly (≥ 65 years) patients (59% female) admitted to the Internal Medicine Department with acute non-cardiac events and elevated hs-cTnI (≥ 100 ng/L).

Research results

Patient age ranged from 65 to 100 (mean ± SD: 85.4 ± 7.61) years. The median hs-cTnI value was 284.2 ng/L. The overall in-hospital mortality was 32% (47 patients). Multivariate analysis showed that age (OR 1.062 per 1 year increase, 95%CI: 1.000-1.127; P = 0.048) and creatinine levels (OR 2.065 per 1 mg/dL increase, 95%CI: 1.383-3.085; P < 0.001) were the only independent predictors of death. Mortality was 49% in patients with eGFR < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2.

Research conclusions

Myocardial injury is a malignant condition in elderly patients admitted to the hospital for non-cardiac reasons and indicates poor overall prognosis. The presence of severe renal impairment remains as an independent marker of extremely high in-hospital mortality in this selected patient group.

Research perspectives

Our results emphasize the need for more aggressive monitoring and treatment in elderly patients with severe renal impairment admitted to the hospital for non-cardiac reasons in order to avoid complications and death.

Footnotes

Institutional review board statement: The study was reviewed and approved by the University Hospital of Ioannina Institutional Review Board, No. 123, 25-02-2019 / 6303.

Informed consent statement: Signed informed consent form was not needed for this study, University Hospital of Ioannina has given permission to conduct this study.

Conflict-of-interest statement: None of the authors has any conflicts of interest.

STROBE statement: The authors have read the STROBE Statement—checklist of items, and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the STROBE Statement—checklist of items.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Peer-review started: April 25, 2021

First decision: June 17, 2021

Article in press: September 8, 2021

Specialty type: Geriatrics and Gerontology

Country/Territory of origin: Greece

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Xi K S-Editor: Wu YXJ L-Editor: A P-Editor: Wang LYT

Contributor Information

Ioanna Samara, Second Department of Cardiology, University Hospital of Ioannina, Ioannina 45110, Greece.

Stavroula Tsiara, Second Department of Internal Medicine, University Hospital of Ioannina, Ioannina 45110, Greece.

Michail I Papafaklis, Second Department of Cardiology, University Hospital of Ioannina, Ioannina 45110, Greece.

Konstantinos Pappas, Second Department of Cardiology, University Hospital of Ioannina, Ioannina 45110, Greece.

Georgios Kolios, Laboratory of Biochemistry, University Hospital of Ioannina, Ioannina 45110, Greece.

Nikolaos Vryzas, Second Department of Cardiology, University Hospital of Ioannina, Ioannina 45110, Greece.

Lampros K Michalis, Second Department of Cardiology, University Hospital of Ioannina, Ioannina 45110, Greece.

Eleni T Bairaktari, Laboratory of Clinical Chemistry, School of Health Sciences, Faculty of Medicine, University of Ioannina, Ioannina 45110, Greece.

Christos S Katsouras, Second Department of Cardiology, University Hospital of Ioannina, Ioannina 45110, Greece. cskats@yahoo.com.

Data sharing statement

No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Thygesen K, Mair J, Giannitsis E, Mueller C, Lindahl B, Blankenberg S, Huber K, Plebani M, Biasucci LM, Tubaro M, Collinson P, Venge P, Hasin Y, Galvani M, Koenig W, Hamm C, Alpert JS, Katus H, Jaffe AS Study Group on Biomarkers in Cardiology of ESC Working Group on Acute Cardiac Care. How to use high-sensitivity cardiac troponins in acute cardiac care. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:2252–2257. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Collinson PO, Apple F, Jaffe AS. Use of troponins in clinical practice: Evidence in favour of use of troponins in clinical practice: Evidence in favour of use of troponins in clinical practice. Heart. 2020;106:253–255. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2019-315622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mariathas M, Curzen N. Use of troponins in clinical practice: Evidence against the use of troponins in clinical practice. Heart. 2020;106:251–252. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2019-315765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blankenberg S, Salomaa V, Makarova N, Ojeda F, Wild P, Lackner KJ, Jørgensen T, Thorand B, Peters A, Nauck M, Petersmann A, Vartiainen E, Veronesi G, Brambilla P, Costanzo S, Iacoviello L, Linden G, Yarnell J, Patterson CC, Everett BM, Ridker PM, Kontto J, Schnabel RB, Koenig W, Kee F, Zeller T, Kuulasmaa K BiomarCaRE Investigators. Troponin I and cardiovascular risk prediction in the general population: the BiomarCaRE consortium. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:2428–2437. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frencken JF, Donker DW, Spitoni C, Koster-Brouwer ME, Soliman IW, Ong DSY, Horn J, van der Poll T, van Klei WA, Bonten MJM, Cremer OL. Myocardial Injury in Patients With Sepsis and Its Association With Long-Term Outcome. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2018;11:e004040. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.117.004040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vestjens SMT, Spoorenberg SMC, Rijkers GT, Grutters JC, Ten Berg JM, Noordzij PG, Van de Garde EMW, Bos WJW Ovidius Study Group. High-sensitivity cardiac troponin T predicts mortality after hospitalization for community-acquired pneumonia. Respirology. 2017;22:1000–1006. doi: 10.1111/resp.12996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eggers KM, Lind L, Venge P, Lindahl B. Factors influencing the 99th percentile of cardiac troponin I evaluated in community-dwelling individuals at 70 and 75 years of age. Clin Chem. 2013;59:1068–1073. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2012.196634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eggers KM, Venge P, Lindahl B, Lind L. Cardiac troponin I levels measured with a high-sensitive assay increase over time and are strong predictors of mortality in an elderly population. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:1906–1913. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.12.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang AZ, Schaffer JT, Holt DB, Morgan KL, Hunter BR. Troponin Testing and Coronary Syndrome in Geriatric Patients With Nonspecific Complaints: Are We Overtesting? Acad Emerg Med. 2020;27:6–14. doi: 10.1111/acem.13766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang SJ, Wang Q, Cui YJ, Wu W, Zhao QH, Xu Y, Wang JP. High-sensitivity cardiac troponin T in geriatric inpatients. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2016;65:111–115. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2016.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mariathas M, Allan R, Ramamoorthy S, Olechowski B, Hinton J, Azor M, Nicholas Z, Calver A, Corbett S, Mahmoudi M, Rawlins J, Simpson I, Wilkinson J, Kwok CS, Cook P, Mamas MA, Curzen N. True 99th centile of high sensitivity cardiac troponin for hospital patients: prospective, observational cohort study. BMJ. 2019;364:l729. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaura A, Panoulas V, Glampson B, Davies J, Mulla A, Woods K, Omigie J, Shah AD, Channon KM, Weber JN, Thursz MR, Elliott P, Hemingway H, Williams B, Asselbergs FW, O'Sullivan M, Kharbanda R, Lord GM, Melikian N, Patel RS, Perera D, Shah AM, Francis DP, Mayet J. Association of troponin level and age with mortality in 250 000 patients: cohort study across five UK acute care centres. BMJ. 2019;367:l6055. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l6055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu W, Li DX, Wang Q, Xu Y, Cui YJ. Relationship between high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T and the prognosis of elderly inpatients with non-acute coronary syndromes. Clin Interv Aging. 2018;13:1091–1098. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S157048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tang O, Daya N, Matsushita K, Coresh J, Sharrett AR, Hoogeveen R, Jia X, Windham BG, Ballantyne C, Selvin E. Performance of High-Sensitivity Cardiac Troponin Assays to Reflect Comorbidity Burden and Improve Mortality Risk Stratification in Older Adults With Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2020;43:1200–1208. doi: 10.2337/dc19-2043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Di Micoli A, Scarciello C, De Notariis S, Cavazza M, Muscari A. Determinants of troponin T and I elevation in old patients without acute coronary syndrome. Emergency Care J. 2019;15:1. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sedighi SM, Nguyen M, Khalil A, Fülöp T. The impact of cardiac troponin in elderly patients in the absence of acute coronary syndrome: A systematic review. Int J Cardiol Heart Vasc. 2020;31:100629. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcha.2020.100629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Froissart M, Rossert J, Jacquot C, Paillard M, Houillier P. Predictive performance of the modification of diet in renal disease and Cockcroft-Gault equations for estimating renal function. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:763–773. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004070549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clerico A, Ripoli A, Masotti S, Musetti V, Aloe R, Dipalo M, Rizzardi S, Dittadi R, Carrozza C, Storti S, Belloni L, Perrone M, Fasano T, Canovi S, Correale M, Prontera C, Guiotto C, Cosseddu D, Migliardi M, Bernardini S. Evaluation of 99th percentile and reference change values of a high-sensitivity cTnI method: A multicenter study. Clin Chim Acta. 2019;493:156–161. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2019.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lala A, Johnson KW, Januzzi JL, Russak AJ, Paranjpe I, Richter F, Zhao S, Somani S, Van Vleck T, Vaid A, Chaudhry F, De Freitas JK, Fayad ZA, Pinney SP, Levin M, Charney A, Bagiella E, Narula J, Glicksberg BS, Nadkarni G, Mancini DM, Fuster V Mount Sinai COVID Informatics Center. Prevalence and Impact of Myocardial Injury in Patients Hospitalized With COVID-19 Infection. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76:533–546. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.deFilippi CR, Herzog CA. Interpreting Cardiac Biomarkers in the Setting of Chronic Kidney Disease. Clin Chem. 2017;63:59–65. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2016.254748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miller-Hodges E, Anand A, Shah ASV, Chapman AR, Gallacher P, Lee KK, Farrah T, Halbesma N, Blackmur JP, Newby DE, Mills NL, Dhaun N. High-Sensitivity Cardiac Troponin and the Risk Stratification of Patients With Renal Impairment Presenting With Suspected Acute Coronary Syndrome. Circulation. 2018;137:425–435. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.030320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vassar M, Holzmann M. The retrospective chart review: important methodological considerations. J Educ Eval Health Prof. 2013;10:12. doi: 10.3352/jeehp.2013.10.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No additional data are available.