Abstract

Background

The field of orthopaedic surgery has one of the lowest percentages of practicing female physicians. Studies have shown disparities in various academic societies’ award recipients by sex. Given the recent increased use of physician rating platforms by patients and focus on consumer-driven healthcare, our aim was to assess the recognition of female orthopaedic surgeons.

Methods

A twenty-year quantitative analysis was performed comparing the rate of top female orthopaedic surgeons listed on Castle Connolly's “America's Top Doctors” to the percentage of practicing female orthopaedic surgeons as reported by the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons.

Results

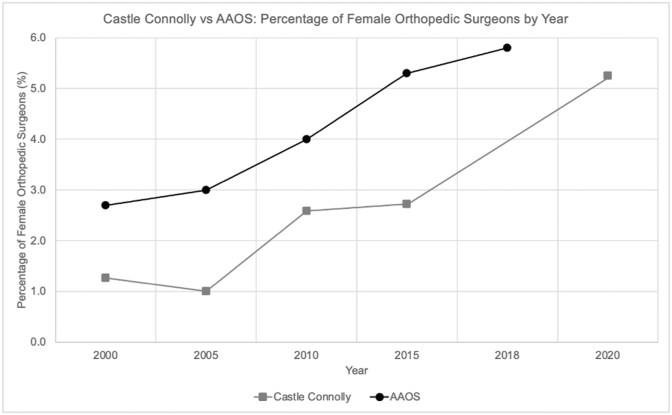

From 2000 to 2020, there was a statistically significant increase in the percentage of top female orthopaedic surgeons listed on Castle Connolly (1.3%–5.3%), as well as an increase in overall practicing AAOS female members (2.7%–5.8%). When comparing the rate of top female orthopaedic surgeons listed on Castle Connolly to the proportion of practicing female AAOS members from 2000 to 2020, there were no statistically significant differences.

Conclusions

The increase in the rate of top female orthopaedic surgeons recognized by Castle Connolly was proportionate to the increase in percentage of practicing female AAOS members over the past 20 years. This study highlights the persistence of a gender discrepancy in the academic sector of orthopaedic surgery.

Keywords: Castle connolly, Women, Orthopaedic surgeons, AAOS

1. Introduction

Women accounted for approximately 5.8% of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) 2018 membership while they comprise approximately half of all medical students within the United States.1 While other surgical fields have seen steady and consistent increases in female trainees, the percentage of women in orthopaedic surgery has remained consistently low around 5.0% over the last two decades.2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 Current literature has suggested that few women are currently practicing orthopaedic surgery due to lack of role models, female faculty, and exposure to musculoskeletal medicine.1,13,14

Castle Connolly annually publishes a listing of “America's Top Doctors” based on a multitude of factors including nomination, educational background, malpractice and disciplinary record, academic achievements as well as other criteria. The recent rise in online social media and increased emphasis on patient satisfaction has contributed to the growing trend of patients searching for physicians through online resources.15, 16, 17

While previous publications have investigated the reasons for the low percentage of women in orthopaedic surgery, to the best of our knowledge, there has not been a study to assess the recognition of female orthopaedic surgeons within the field of orthopaedic surgery.1 The objective of this study was to perform a quantitative analysis in order to characterize twenty-year trends of female AAOS membership and the recognition of top female orthopaedic surgeons in the United States, as represented by Castle Connolly's “America's Top Doctors”.

2. Materials and methods

Institutional review board approval was not required for this study.

Castle Connolly's “America's Top Doctors” editions were retrospectively reviewed by the authors to determine the number of female orthopaedic surgeons recognized from 2000 to 2020. Castle Connolly's “America's Top Doctors” 1st, 5th, 10th, and 15th hardcover editions were used to collect data for the years 2000, 2005, 2010, and 2015, respectively. Study data for 2020 was recorded directly from the official Castle Connolly website (www.castleconnolly.com, accessed October 12, 2020). Orthopaedic surgeons in each edition were reviewed. In accordance with previous methodology published by our group, three authors (AAC, BDB, GMP) then reviewed names of listed orthopaedic surgeons to estimate the number of female orthopaedic surgeons.18 Names which were considered gender neutral by the authors were verified using an official affiliated hospital or practice website to ensure proper tallies.18

To compare the proportion of female orthopaedic surgeons named “America's Top Doctors” by Castle Connolly to the proportion of practicing female orthopaedic surgeons in the U.S workforce, census reports were obtained from the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS).2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 AAOS census percentages for the established study time points were identified and recorded. The AAOS's 2018 OPUS survey data was used in lieu of workforce data for 2020, as the AAOS 2020 OPUS data was not available for review at the time of this publication. Trends between the two cohorts were compared using chi-square or Fisher's exact test. A Fisher's exact test was utilized if the sample size (n-value) was <5. A p-value of <0.05 was used to define statistical significance. Data were analyzed using SPSS version 27 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY).

3. Results

In 2000, 2 out of 158 (1.3%) orthopaedic surgeons listed by Castle Connolly were female. Top female orthopaedic surgeons decreased to 1% in 2005. From 2010 to 2020, there was an increase in rate of top female orthopaedic surgeons with 7 out of 271 in 2010 (2.6%) and 8 out of 294 (2.7%) in 2015 (Table 1). The most significant increase in female orthopaedic surgeons occurred between 2015 and 2020, as female recognition on Castle Connolly rose from 8 (2.7%) to 118 (5.3%), respectively (Table 1). In comparison, the percentage of practicing female orthopaedic surgeons as identified by the AAOS increased from 2.7% in 2000 to 5.8% in 2018 (Table 2).

Table 1.

Sex Distribution of Top Castle Connolly Orthopaedic Surgeons, by year

| Year | CC - Listed Female Orthopaedic Surgeons | CC - Listed Male Orthopaedic Surgeons | CC - Total Listed Orthopaedic Surgeons |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 2 | 156 | 158 |

| 2005 | 2 | 197 | 199 |

| 2010 | 7 | 264 | 271 |

| 2015 | 8 | 286 | 294 |

| 2020 | 118 | 2128 | 2246 |

| p-value | 0.0016 |

Table 2.

Sex Distribution of AAOS Orthopaedic Surgeons, by year

| Year | AAOS Female | AAOS Male | AAOS Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 311 | 11199 | 11510 |

| 2005 | 312 | 10084 | 10396 |

| 2010 | 377 | 9054 | 9431 |

| 2015 | 408 | 7296 | 7704 |

| 2018 | 393 | 6382 | 6775 |

| p-value | <0.00001 |

From 2000 to 2020, there was a statistically significant increase in top female orthopaedic surgeons listed on Castle Connolly (Table 1), as well as an increase in overall practicing AAOS female members (Table 2). When comparing the rate of top female orthopaedic surgeons listed on Castle Connolly to the rate of female AAOS membership from 2000 to 2020, there were no statistically significant differences (Table 3).

Table 3.

Rate Comparison of Top Female Castle Connolly Orthopaedic Surgeons versus Female AAOS Orthopaedic Surgeons

| Year | Top Female Surgeons Castle Connolly | AAOS Female Ortho | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 1.3 | 2.7 | 0.41 |

| 2005 | 1.0 | 3 | 0.34 |

| 2010 | 2.6 | 4 | 0.49 |

| 2015 | 2.7 | 5.3 | 0.07 |

| 2020 | 5.3 | 5.8 (2018) | 0.53 |

4. Discussion

Peer-reviewed physician directories may be influential in terms of patient education and guiding patients in the physician selection process. Our study indicates although there has been an increase of approximately 4.0% in the percentage of women in Castle Connolly's listing of orthopaedic surgeons between the years 2000–2020, total female orthopaedic surgeon award recipients are underrepresented as compared to their male counterparts which have consistently comprised >94.0% of award recipients (Fig. 1). Our group further noted that the percentage of female orthopaedic surgeons within Castle Connolly's official website (5.3%) compared to the AAOS's 2018 reporting of the percentage of practicing female orthopaedic surgeons within the workforce (5.8%) were statistically similar (Fig. 2). These findings are ubiquitous with previous reports demonstrating overall underrepresentation of women physicians among recognition award recipients within physical medicine and rehabilitation, dermatology, neurology, anesthesiology, head and neck surgery, and plastic surgery specialty organizations. However, these findings shed light into promising steps toward inclusion within the field of orthopaedic surgery, as the increased rate of female award winners has kept pace with increases in practicing female AAOS members.19, 20, 21

Fig. 1.

Castle Connolly's Percentage of Orthopaedic Surgeons by Sex.

Fig. 2.

AAOS Percentage of Female Orthopaedic Surgeons in the US Workforce vs. Castle Connolly's Percentage of Female Orthopaedic Surgeons by Year.

There has been an addition of 100 female orthopaedic surgeons to Castle Connolly's award recipients between the years 2015–2020. When accounting for the total of both male and female award recipients, this amounts to approximately a one-fold increase. This change may be due to Castle Connolly's platform transitioning from hard copies to a web-based platform during that period or may be due to the time that it took for female orthopaedic residents and fellows to finish their training and develop a strong standing within the field. A study by Heest et al. estimates that 619 (15.4%) of 4021 resident positions in orthopaedic surgery are occupied by women.22 One recent study suggests that the number of female orthopaedic surgery resident trainees has had a slow increase and may actually be lagging behind other specialties, creating a barrier to have a more diverse workforce within orthopaedic surgery.23 Although our finding highlights underrepresentation of female orthopaedic surgeons in Castle Connolly's “America's Top Doctors” by total number, there were no statistical differences in representation when compared to the pool of practicing female orthopaedic surgeons.

In the United States, a study by Seetharam et al. noted that the percentage of female first and corresponding authors for one major orthopaedic journal has increased by nearly 30% from 1983 to 2015.24 However, there is much variability in the global recognition and recruitment of female orthopaedic surgeons. In India, recent literature has found that the percentage of female representation in orthopaedic surgery is only 1.0% of their workforce.25,26 A study by Khalifa et al. determined the prevalence of female authorship of 2 orthopaedic journals in Saudi Arabia and Egypt to be ∼14.0% and 0.3%, respectively.27 Contrarily, Portugal has passed legislation mandating a minimum 40% inclusion rate for men and women candidates for administrative boards of higher-education institutions, a change which some experts say may have contributed to women accounting for nearly half of all authors in their nation.28

When considering the lag in recognition of female orthopaedic surgeons some proposed reasons include the low percentage of practicing female orthopaedic surgeons, decreased number of female orthopaedic surgeons/mentors in high-ranking positions, perspective that the field is not friendly to females and/or conducive to females looking for a balanced work-life schedule and family planning, lack of exposure to orthopaedic principles and foundations in medical school, expensive pathway to becoming an orthopaedic surgeon, and greater fit of other medical specialties.1,23,25,26,29 Potential solutions to these impediments may include dedicated funding to support female recruitment, mandated candidate lists that include an equal percentage of men and women for professional postings, early exposure to orthopaedic surgery in medical school via appointed mentors, and improved training to avoid unconscious/conscious bias when recruiting female applicants to orthopaedic surgery or supporting female authors.26 Determining which of the aforementioned possibilities is the root cause will require additional data and analysis as we monitor trends in orthopaedic surgery in the coming years.

Our study is important for several reasons. First, a recent survey of both male and female graduating orthopaedic surgery residents has indicated that both genders have similar leadership and research aspirations, suggesting representation of both genders in such roles to be proportionate to the overall representation in the field.30 Our study supports these expectations, as increases in rate of female award recipients, as recognized by Castle Connolly, were similar to the increasing total number of practicing female AAOS members. Second, this study is the first to assess the recognition of female orthopaedic surgeons within “America's Top Doctors”. It highlights an increase in nationally recognized female orthopaedic surgeon award recipients that is proportionate to the pool of practicing female AAOS-affiliated orthopaedic surgeons. In doing so, we provide a concrete recruitment guide for mentors seeking to engage female applicants. Third, we demonstrate the most up-to-date longitudinal analysis of twenty-year trends that captures the effect of strategies designed to increase female recruitment. We encourage extension of our investigation to monitor yearly rate changes of female recognition within the field of orthopaedic surgery.

This study does have limitations. First, the AAOS collects data via surveys disseminated to their membership; consequently, there is a chance that not all orthopaedic surgeons in the United States are registered with the AAOS, introducing an element of selection bias. Second, the quantitative nature limits in-depth analysis of the complex decision-making process in selecting award recipients. Finally, when using hard copies of Castle Connolly's “America's Top Doctors”, names within the orthopaedic surgery section were browsed for traditionally gender neutral and female names, leaving room for a certain level of selection bias; however, this was mitigated by an ancillary search of official affiliated hospital or practice websites.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, our data shows that the increase in rate of Castle Connolly's award recipients has kept pace with the increasing total of practicing female AAOS-affiliated orthopaedic surgeons, a promising sign for future female applicants. Although the proportion and total number of female membership in the AAOS has increased over the last twenty years, there continues to be a disproportionately lower rate of females to receive academic recognition within orthopaedic surgery when compared to their male counterparts. This current study raises awareness regarding this gender gap through quantitative analysis with the goal of encouraging future research into this topic. Further research to delineate the root causes of the gender gap between male and female orthopaedic surgeons that are recognized for these prestigious awards within orthopaedic surgery is warranted. Awareness of selection factors may help female orthopaedic surgeons and academic societies to implement strategies designed to improve diversity within their ranks, enabling our future surgeons to care for diverse patient populations.

Conflicts of interest and source of funding

The authors have no declaration of interests. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Financial disclosures

None.

Funding

None.

IRB approval was not required for this study. This work involved the retrospective review of publicly accessible data; thus, patient consent was not required for this study.

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

This work was performed at Rutgers New Jersey Medical School, New Jersey, USA.

This work is not published or currently under consideration for publication at any other journal.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Akhil A. Chandra: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Resources, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Visualization. Brian D. Batko: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Visualization. Gabriela M. Portilla: Investigation, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Balazs Galdi: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Visualization. Kathleen Beebe: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Visualization.

Declaration of competing interest

None.

Contributor Information

Akhil A. Chandra, Email: ac1166@rwjms.rutgers.edu.

Brian D. Batko, Email: bdb103@njms.rutgers.edu.

Gabriela M. Portilla, Email: gmp148@rwjms.rutgers.edu.

Balazs Galdi, Email: galdiba@njms.rutgers.edu.

Kathleen Beebe, Email: kathleen.beebe@rutgers.edu.

References

- 1.Rohde R.S., Wolf J.M., Adams J.E. Where are the women in orthopaedic surgery? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2016;474:1950–1956. doi: 10.1007/s11999-016-4827-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Surgeons AAoO . AAOS; 2000. Orthopaedic Physician Census Report. 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Surgeons AAoO . AAOS; 2002. Orthopaedic Practice in the U.S. 2002-2003. Affairs DoRaS. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Surgeons AAoO . Affairs DoRaS. AAOS; 2004. Orthopaedic practice in the US 2004-2005 (OPUS 2004) [Google Scholar]

- 5.Surgeons AAoO . Affairs DoRaS. AAOS; 2006. Orthopaedic Practice in the US 2005-2006. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Surgeons AAoO . Value ADoCQa. AAOS; 2019. Orthopaedic practice IN the U.S. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Surgeons AAoO . AAOS; 2016. ORTHOPAEDIC PRACTICE IN THE U.S. Department of Research Q, and Scientific Affairs. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Surgeons AAoO . Affairs DoRaS. AAOS; 2015. Orthopaedic practice IN the U.S. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Surgeons AAoO . Affairs DoRaS. AAOS; 2013. Orthopaedic practice IN the U.S. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Surgeons AAoO . Affairs DoRaS. AAOS; 2011. Orthopaedic practice IN the U.S. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Surgeons AAoO . Affairs DoRaS. AAOS; 2008. Orthopaedic practice in the U.S. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blakemore L.C., Hall J.M., Biermann J.S. Women in surgical residency training programs. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85:2477–2480. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200312000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang Y., Li J., Wu X. Factors influencing subspecialty choice among medical students: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2019;9 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-022097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Heest A.E., Agel J. The uneven distribution of women in orthopaedic surgery resident training programs in the United States. JBJS. 2012;94:e9. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.01583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hanauer D.A., Zheng K., Singer D.C., Gebremariam A., Davis M.M. Public awareness, perception, and use of online physician rating sites. J Am Med Assoc. 2014;311:734–735. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.283194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holliday A.M., Kachalia A., Meyer G.S., Sequist T.D. Physician and patient views on public physician rating websites: a cross-sectional study. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32:626–631. doi: 10.1007/s11606-017-3982-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Donnally C.J., III, Li D.J., Maguire J.A., Jr. How social media, training, and demographics influence online reviews across three leading review websites for spine surgeons. Spine J. 2018;18:2081–2090. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2018.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rynecki N.D., Krell E.S., Potter J.S., Ranpura A., Beebe K.S. How well represented are women orthopaedic surgeons and residents on major orthopaedic editorial boards and publications? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2020;478:1563–1568. doi: 10.1097/CORR.0000000000000824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Silver J.K., Bhatnagar S., Blauwet C.A. Female physicians are underrepresented in recognition awards from the American Academy of physical medicine and rehabilitation. Pharm Manag PM R. 2017;9:976–984. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2017.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Silver J.K., Bank A.M., Slocum C.S. Women physicians underrepresented in American Academy of Neurology recognition awards. Neurology. 2018;91:e603–e614. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000006004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Silver J.K., Slocum C.S., Bank A.M. Where are the women? The underrepresentation of women physicians among recognition award recipients from medical specialty societies. Pharm Manag PM R. 2017;9:804–815. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2017.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van Heest A. Gender diversity in orthopedic surgery: we all know it's lacking, but why? Iowa Orthop J. 2020;40:1–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chambers C.C., Ihnow S.B., Monroe E.J., Suleiman L.I. Women in orthopaedic surgery: population trends in trainees and practicing surgeons. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2018;100:e116. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.17.01291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Seetharam A., Ali M.T., Wang C.Y. Authorship trends in the journal of orthopaedic research: a bibliometric analysis. J Orthop Res. 2018;36:3071–3080. doi: 10.1002/jor.24054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Madhuri V., Khan N. Orthopaedic women of India: impediments to their growth. Indian J Orthop. 2020;54:409–410. doi: 10.1007/s43465-020-00130-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vaishya R, Vaish A. Disproportionate gender representation in orthopaedics and its research. J. Clin. Orthop. Trauma. 2021;22:101572. doi: 10.1016/j.jcot.2021.101572. ISSN 0976-5662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khalifa A.A., El-Hawary A.S., Sadek A.E., Ahmed E.M., Ahmed A.M., Haridy M.A. Comparing the gender diversity and affiliation trends of the authors for two orthopaedics journals from the Arab world. Journal of Taibah University Medical Sciences. 2021;16:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jtumed.2020.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Francescon D. Vol. 2021. Elsevier Connect: Elsevier; 2021. (Portugal Leads in Gender Equality in Research: What Can We Learn from Their Leaders?). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mulcahey M.K., Nemeth C., Trojan J.D., OʼConnor M.I. The perception of pregnancy and parenthood among female orthopaedic surgery residents. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2019;27:527–532. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-18-00216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hariri S., York S.C., O'Connor M.I., Parsley B.S., McCarthy J.C. Career plans of current orthopaedic residents with a focus on sex-based and generational differences. JBJS. 2011;93:e16. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.00489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]