Abstract

Background: Phenobarbital offers several possible advantages to benzodiazepines including a longer half-life and anti-glutamate activity, and is an alternative for the treatment of alcohol withdrawal. The objective of this analysis was to evaluate the safety and efficacy of a phenobarbital protocol for alcohol withdrawal newly implemented at our institution. Methods: This was a single-center, retrospective analysis of adult patients admitted to the medical/surgical/burn/trauma intensive care unit (ICU) with or at risk of severe alcohol withdrawal. Patients who were admitted prior to guideline implementation and received scheduled benzodiazepines (PRE) were compared to those who received phenobarbital post guideline update (POST). The primary outcome was ICU length of stay (LOS). Results: Upon analysis, 68 patients in the PRE and 64 patients in the POST were identified for inclusion. The median APACHE II score was significantly higher in the POST (4.5 [3:9] vs 10 [5:13], P < 0.001). ICU (2 [1:2] vs 2 [2:5], P = 0.002) and hospital (4.5 [3:6] vs 8 [6:12], P < 0.001) LOS were significantly longer in the POST. There was no difference in mortality or duration of mechanical ventilation. More patients required propofol or dexmedetomidine on day one in the POST (P < 0.001). Conclusion: Patients in the POST had significantly longer ICU and hospital LOS, and had a higher baseline severity of illness. Future research is needed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of phenobarbital compared to benzodiazepines for severe alcohol withdrawal.

Keywords: critical care, neurology, psychiatric

Introduction

Alcohol use disorder is common, with an estimated prevalence of 40% in hospitalized patients. 1 Alcohol binds to gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptors in the brain and leads to elevated GABA levels. The production of glutamate is consequently increased to counteract inhibitory neurotransmission. Upon alcohol cessation, sudden decreased levels of GABA and chronically elevated glutamate levels contribute to the signs and symptoms seen in alcohol withdrawal syndrome. These manifestations can range from minor symptoms, such as tremors, agitation, and diaphoresis, to major and life-threatening symptoms seen in severe alcohol withdrawal, such as seizures and delirium tremens. 2

Benzodiazepines are GABA-A receptor agonists, which have traditionally been the agents of choice to prevent and treat the symptoms and complications of alcohol withdrawal syndrome. 3 While benzodiazepines have data to support their efficacy and safety, the involvement of receptors other than GABA in alcohol withdrawal, such as N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA), kainate, and α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA), suggest that other medications may be beneficial.4,5 Additionally, benzodiazepine resistance may develop due to changes to the GABA receptor. 6 Phenobarbital is a potential alternative for the management of patients experiencing, or at risk of, developing alcohol withdrawal. 7 Phenobarbital has a wide range of receptor activity, including GABA, NMDA, kainite, and AMPA. Phenobarbital may have a role in the presence of benzodiazepine resistance as it binds to the GABA receptor at an allosteric site that conveys activity without requiring the presence of GABA. In addition to the anti-glutamate activity, the long half-life of phenobarbital may provide a more robust management of severe alcohol withdrawal.8,9

Our institution recently implemented a guideline for the use of phenobarbital in alcohol withdrawal syndrome (Appendix). The document provides guidance on phenobarbital initiation, loading dose considerations, and taper dosing, however, the provider ultimately selects the most optimal agent and regimen. The objective of this analysis was to determine the safety and efficacy of phenobarbital for alcohol withdrawal pre and post guideline implementation at our institution.

Materials and Methods

A single-center, retrospective quasi-experimental analysis was performed at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, a 793-bed acute, tertiary care, academic medical center in Boston, MA. Approval from the Partners Institutional Review Board was obtained prior to the start of this study. Patients were identified from the hospital’s electronic health records through International Classification of Diseased, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) codes for alcohol withdrawal. Adult patients admitted to the medical/surgical/burn/trauma intensive care unit (ICU) were categorized into the PRE group if they had received scheduled benzodiazepines for at least 24 hours pre guideline update (September 1, 2016-April 1, 2017), or to the POST group if they had received phenobarbital for severe alcohol withdrawal post guideline update (September 1, 2017-April 1, 2018). Severe alcohol withdrawal was defined by at least one of the following criteria: alcohol withdrawal seizures on presentation, history of withdrawal seizures and at risk for withdrawal, delirium tremens on presentation, history of delirium tremens and at risk for withdrawal, or history of severe alcohol withdrawal. Patients were excluded from the study if they met any of the following criteria: underlying seizure disorder unrelated to alcohol withdrawal, comorbid condition causing permanently altered mental status, concurrent use of primidone, or pregnancy.

Data collected at baseline included patient demographics, past medical history, liver function tests, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II score, and Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score upon admission. Total daily doses of benzodiazepines and phenobarbital were collected along with additional sedative and antipsychotic requirements. The use of benzodiazepines in the 24 hours prior to the start of the treatment regimen was evaluated in both groups. Total benzodiazepine requirements were reported in lorazepam equivalents using the following dose equivalence: alprazolam 1 mg = chlordiazepoxide 25 mg = clonazepam 0.5 mg = diazepam 10 mg = lorazepam 1 mg = midazolam 2 mg = oxazepam 30 mg. 10 Continuous infusion sedative rates were collected hourly for the first 48 hours and then every 4 hours for up to 2 weeks after admission or until discharge.

The primary outcome of this analysis was ICU length of stay (LOS). Secondary outcomes included hospital LOS, duration of mechanical ventilation, total daily doses of benzodiazepines and phenobarbital, use and duration of phenobarbital taper, and the use of additional antipsychotics and sedatives. The need for intubation and the presence of withdrawal seizures and/or delirium tremens was also collected during admission. The Confusion Assessment Method for the ICU (CAM-ICU), and Richmond Agitation and Sedation Scale (RASS) scores were used to assess agitation and depth of sedation, respectively. The phenobarbital regimens were described by collecting characteristics of the loading dose if utilized (i.e., weight-based dose, divided vs single dose) and duration of taper if utilized.

Per our institution’s protocol, if the patient is to receive a phenobarbital loading dose, a divided dosing strategy is recommended. This is described in the protocol as 40% of the total dose initially, 30% 3 hours later, and the final 30% 3 hours after the second dose. Our protocol recommends a phenobarbital taper for patients with a history of severe withdrawal or patients who show signs and symptoms of withdrawal following the load. The taper begins on day 2 of therapy and continues for up to 6 days total starting with 64.8 mg enterally twice daily and decreasing dose by 50% every 2 days.

Post hoc, four subgroups were identified in an attempt to better understand the role of phenobarbital for alcohol withdrawal in targeted patient populations. The four subgroups were: (1) history of severe withdrawal, withdrawal seizures, or delirium tremens; (2) presentation with withdrawal seizures, or delirium tremens; (3) medical ICU (MICU) patients; and (4) phenobarbital load < 9 mg/kg ideal body weight versus ≥ 9 mg/kg ideal body weight. Additionally, a multivariable analysis was performed and controlled for the following characteristics: PRE versus POST, MICU versus surgical/burn/trauma ICU (SICU), APACHE II score, phenobarbital loading dose ≥ 9 mg/kg ideal body weight, age ≥ 65, and past medical history of alcohol use disorder with severe withdrawal.

A sample size of 63 patients per arm was calculated assuming an average LOS of 7 days with a 20% relative risk reduction based on 80% power and an alpha of 0.05. 11 Continuous data was analyzed using the paired t-test (parametric data, expressed as mean [standard deviation]) or Mann–Whitney U-test (non-parametric data, expressed as median and interquartile range [IQR]) when appropriate. The chi-square test was used for categorical data when appropriate.

Results

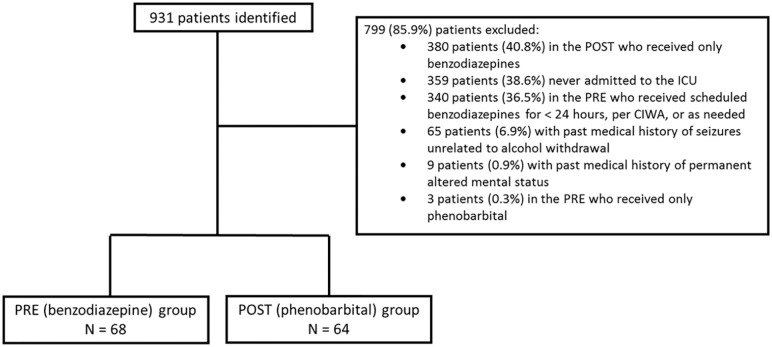

During the study period, 931 patients were evaluated for inclusion, of which 68 patients in the PRE and 64 patients in the POST were ultimately included in the final analysis. Reasons for exclusion are presented in Figure 1. Patient demographics are shown in Table 1. Significantly more patients in the PRE presented to the SICU (58.8% vs 32.8%, P = 0.003) and significantly more patients in the POST presented to the MICU (41.1% vs 67.2%, P = 0.003). Patients in the POST had significantly higher APACHE II scores (4 [3:9] vs 10 [5:13], P < 0.0001).

Figure 1.

Patient exclusion.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics.

| PRE (N = 68) | POST (N = 64) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years a | 49.1 [37:59] | 52 [44:60] | 0.384 |

| Male b | 49 (72) | 46 (71.8) | 0.902 |

| Weight (kg) a | 83.8 [68:95.5] | 82.9 [71:93.5] | 0.897 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | |||

| Raw number a | 27 [23:31] | 27.2 [24.5:29] | 0.810 |

| <18.5 b | 3 (4.4) | 3 (4.7) | 0.939 |

| >30 b | 21 (30.9) | 11 (17.2) | 0.067 |

| Height, cm a | 175 [167:180] | 175 [169.5:180.5] | 0.897 |

| Ethnicity b | |||

| Caucasian | 55 (80.1) | 46 (71.8) | 0.222 |

| African American | 9 (13.2) | 7 (10.9) | 0.686 |

| Hispanic | 4 (5.9) | 8 (12.5) | 0.186 |

| Asian | 0 | 2 (3.13) | — |

| Other | 0 | 1 (1.56) | — |

| Past medical history b | |||

| Alcohol use disorder (AUD) | 61 (89.7) | 57 (89) | 0.905 |

| AUD + severe withdrawal | 41 (60.3) | 35 (54.7) | 0.515 |

| AUD + delirium tremens | 15 (7.4) | 20 (31.25) | 0.232 |

| AUD + seizures | 19 (27.9) | 20 (31.25) | 0.677 |

| Psychiatric disorder | 35 (51.5) | 33 (51.5) | 0.992 |

| Liver disease | 6 (8.8) | 11 (17.1) | 0.152 |

| Presentation b | |||

| Delirium tremens | 8 (11.8) | 9 (14.1) | 0.694 |

| Withdrawal seizures | 5 (7.4) | 13 (20.3) | 0.056 |

| Baseline labs a | |||

| AST, U/L | 34.5 [18:65] | 32 [19.75:87.75] | 0.617 |

| ALT, U/L | 51.5 [30:108] | 59.5 [32:127.25] | 0.490 |

| Total bilirubin, mg/dL | 0.4 [0.4:0.9] | 0.7 [0.4:1.4] | 0.037 |

| INR | 1.1 [1:1.2] | 1.1 [1.1:1.2] | 0.447 |

| Albumin, g/dL | 3.82 [3.4:4.4] | 4 [3.5:4.3] | 0.332 |

| Serum creatinine, mg/dL | 0.81 [0.67:0.96] | 0.8 [0.62:1.03] | 0.675 |

| BUN, mg/dL | 9 [6:13] | 9 [6:14] | 0.549 |

| MELD | 6 [6:8] | 7 [6:9] | 0.603 |

| APACHE II Score | 4 [3:9] | 10 [5:13] | <0.0001 |

| ICU unit b | |||

| Medical ICU | 28 (41.1) | 43 (67.2) | 0.003 |

| Surgical ICU | 40 (58.8) | 21 (32.8) | 0.003 |

Note. ALT = alanine aminotransferase; APACHE = Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation; AST = aspartate aminotransferase; AUD = alcohol use disorder; BMI = body mass index; BUN = blood urea nitrogen; ICU = intensive care unit; INR = international normalized ratio; MELD = Model for End-Stage Liver Disease.

Data presented as median [interquartile range].

Data presented as n (%).

ICU and hospital LOS were significantly longer in the POST group (Table 2). There was no difference in mortality, need for intubation, time on mechanical ventilation, or seizures between groups (Table 2). No significant difference was seen in the occurrence of RASS > 0, positive CAM-ICU scores, or the requirement of restraints. Significantly more patients in the POST received dexmedetomidine and propofol on day 1 of admission. There was no significant difference in the use of additional clonidine, antipsychotics, or phenobarbital/benzodiazepines.

Table 2.

Primary and Secondary Outcomes.

| PRE (N = 68) | POST (N = 64) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary outcome | |||

| ICU LOS a | 2 [1:2] | 2 [2:5] | 0.002 |

| Secondary outcome | |||

| Hospital LOS a | 4 [3:6] | 8 [6:12] | <0.001 |

| ICU mortality b | 1 (1.5) | 1 (1.6) | 1 |

| Hospital mortality b | 1 (1.5) | 5 (7.8) | 0.542 |

| Need for intubation b | 24 (35.3) | 34 (53.1) | 0.074 |

| Time on mechanical ventilation, days a | 1 [1:2] | 2 [1:4] | 0.061 |

| Seizures after treatment initiation b | 2 (3) | 2 (3.2) | 1 |

| Need for restraints b | 12 (17.6) | 10 (15.6) | 0.842 |

| Use of additional phenobarbital or benzodiazepines, respectively b | 12 (17.6) | 11 (17.2) | 0.945 |

| Use of dexmedetomidine on day 1 b | 4 (5.9) | 28 (43.8) | <0.001 |

| Use of clonidine on day 1 b | 5 (7.4) | 3 (4.7) | 0.521 |

| Use of propofol on day 1 b | 4 (5.9) | 23 (35.9) | <0.001 |

| Use of antipsychotics on day 1 b | 14 (20.5) | 8 (12.5) | 0.213 |

| RASS > 0 on day 1 b | 41 (60.3) | 26 (40.6) | 0.637 |

| CAM-ICU positive on day 1 b | 24 (35.8) | 32 (50) | 0.087 |

Data presented as median [interquartile range].

Data presented as n (%).

In addition to patient outcomes, the characteristics of the phenobarbital regimens were described. Most patients received a phenobarbital loading dose (90.6%) administered as a one-time dose in 22.4% of patients compared to divided doses per protocol in 77.6% of patients. The median loading dose was 9 mg/kg [7:10] based on ideal body weight. A taper was administered in 65.6% of patients for a median of 4 days. In comparison, average duration of benzodiazepine therapy was 2.9 days; the median was 3 days. More patients in the PRE received benzodiazepines 24 hours prior to the start of treatment (72% vs 60%); the average total dose in lorazepam equivalents was 8.3 mg versus 8.5 mg.

Upon analysis of the prespecified subgroups, the outcomes of ICU LOS, hospital LOS, and APACHE II score remained significantly higher in the POST in the following subgroups: history of severe withdrawal, withdrawal seizures, or delirium tremens, presentation with seizures or delirium tremens, and only MICU admissions (Table 3). There was no difference found in requirement of intubation or duration of mechanical ventilation in the three aforementioned subgroups. The fourth subgroup assessed low versus high phenobarbital loading doses; the dividing point of 9 mg/kg was selected as this was the median loading dose for the total POST. The need for intubation was significantly higher in the lower phenobarbital load group 74% versus 42% (P = 0.023). The APACHE II score was significantly higher in the lower phenobarbital load group 10 [7:16] versus 8 [4:13] (P = 0.014). The time on mechanical ventilation, ICU LOS, and hospital LOS were not significantly different. A multivariable analysis was performed to control for the previously determined patient characteristics. There was no difference in ICU LOS after controlling for PRE versus POST, MICU versus SICU, phenobarbital loading dose ≥ 9 mg/kg ideal body weight, age ≥ 65, and past medical history of alcohol use disorder with severe withdrawal. After controlling for APACHE II scores, a higher APACHE II score correlated with increased ICU LOS (P < 0.001).

Table 3.

Subgroup Analysis.

| History of severe withdrawal, withdrawal seizures, or delirium tremens | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| PRE (N = 46) | POST (N = 35) | P-value | |

| ICU LOS a | 1 [1:2] | 2 [1:4] | 0.002 |

| Hospital LOS a | 4 [3:5.25] | 8 [5:9] | <0.0001 |

| APACHE II a | 4 [2:8.25] | 10 [5:13] | 0.0005 |

| Need for intubation b | 18 (39.1) | 13 (37.1) | 0.855 |

| Time on mechanical ventilation, days a | 1 [1:2.75] | 2 [1:3] | 0.414 |

Data presented as median [interquartile range].

Data presented as n (%).

Discussion

Patients in the POST had significantly longer ICU and hospital LOS. The POST was not associated with a significant change in agitation, mortality, requirement of intubation, or time on the ventilator. There was higher utilization of dexmedetomidine and propofol in the POST but no difference in use of additional phenobarbital or benzodiazepines, clonidine, or antipsychotics. To our knowledge, this is the first study that has shown a negative result with the use of phenobarbital for the treatment of severe alcohol withdrawal in critically ill patients.

A recent systematic review published by Hammond et al found patients in the phenobarbital group to be associated with similar rates of ICU and hospital LOS, and decreased time on mechanical ventilation while our study found an increase in ICU and hospital LOS, and no difference in time on mechanical ventilation. 12 Of note the study by Hammond et al included non-ICU patients while our study only included ICU patients. Evaluation of the baseline characteristics revealed the differences between the PRE and POST groups. Patients in the POST had a significantly higher baseline severity of illness in comparison to the benzodiazepine group as evident by the APACHE II scores. Although this was not a randomized study, we found that our providers may be preferentially selecting phenobarbital in patients with a higher severity of illness. Evaluation of the four prespecified subgroups and performance of a multivariable analysis did not identify significant differences that varied from analysis of the initial cohort for all except one outcome. In the subgroup comparing low versus high loading doses, patients in the lower weight-based load group had significantly higher rates of intubation. APACHE II scores were significantly higher in the lower weight-based load group. However, there may have been factors, not included in the calculation of the score, that influenced the decision to use a lower phenobarbital loading dose. Additionally, a lower dose may have been used to prevent further prolonged respiratory depression and aid with weaning mechanical ventilation.

One of the aims of this study was to describe the phenobarbital regimens of the cohort. Our institutional protocol’s recommendations for phenobarbital loading is modeled from a study published by Nisavic et al 13 and adopted by a sister-institution within our health-care system’s network. The protocol stratifies the severity of illness and recommends a different weight-based loading dose. The rationale for each patient’s weight-based load was difficult to ascertain and not collected. Of the patients who received a phenobarbital loading dose, most patients received the dose divided, per protocol, into a 40%/30%/30% split. Most of the patients in our study did receive a taper. It is unclear what the optimal dose and duration a phenobarbital taper should be. A taper can offer better control of withdrawal symptoms however it can prolong hospitalization and contribute to respiratory depression. Future studies may aid in identifying the most appropriate patient population and dosing regimen for a phenobarbital taper.

One notable limitation with our study is the difference in patient populations. Two similar time frames pre and post protocol implementation were selected, and patients were identified based on ICD-10 codes and records of medication administration. Although the use of ICD-10 codes is common in retrospective analyzes, the mis-coding or incomplete coding of patients may affect the study’s sample population. Despite attempts to identify similar populations, it is evident that the patients in the POST had a significantly higher baseline severity of illness in comparison to the PRE. Additionally, the time frame where patients in the PRE were identified was when the use of dexmedetomidine was restricted at our institution and not allowed for the management of alcohol withdrawal. This may have impacted the choice of sedation and use of additional agents.

Conclusion

Our analysis found that after implementation of an institutional phenobarbital protocol for alcohol withdrawal, patients in the POST had significantly longer ICU and hospital LOS, and had a higher baseline severity of illness. A comparison of patient populations with more similar characteristics and severity of illness may further aid in evaluating the safety and efficacy of phenobarbital for the treatment of severe alcohol withdrawal.

Appendix

Brigham and Women’s Hospital

Adult Drug Administration Guideline Committee

Drug monograph

Phenobarbital (Luminal)

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Melanie Goodberlet  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8241-5167

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8241-5167

References

- 1. Maldonado JR, Sher Y, Ashouri JF, et al. The “Prediction of Alcohol Withdrawal Severity Scale” (PAWSS): systematic literature review and pilot study of a new scale for the prediction of complicated alcohol withdrawal syndrome. Alcohol. 2014;48(4):375-390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bayard M, Mcintyre J, Hill KR, Woodside J. Alcohol withdrawal syndrome. Am Fam Phys. 2004;69(6):1443-1450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Saitz R, Horton NJ, Larson MJ, Winter M, Samet JH. Primary medical care and reductions in addiction severity: a prospective cohort study. Addiction. 2005;100(1):70-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Carta M, Olivera DS, Dettmer TS, Valenzuela CF. Ethanol withdrawal upregulates kainate receptors in cultured rat hippocampal neurons. Neurosci Lett. 2002;327(2):128-132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Haugbol SR, Ebert B, Ulrichsen J. Upregulation of glutamate receptor subtypes during alcohol withdrawal in rats. Alcohol Alcohol. 2005;40(2):89-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sanna E, Mostallino MC, Busonero F, et al. Changes in GABA(A) receptor gene expression associated with selective alterations in receptor function and pharmacology after ethanol withdrawal. J Neurosci. 2003;23(37):11711-11724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kwan P, Brodie MJ. Phenobarbital for the treatment of epilepsy in the 21st century: a critical review. Epilepsia. 2004;45(9):1141-1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Spies CD, Rommelspacher H. Alcohol withdrawal in the surgical patient: prevention and treatment. Anesth Analg. 1999;88(4):946-954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kramp P, Rafaelsen OJ. Delirium tremens: a double-blind comparison of diazepam and barbital treatment. Acta Psychiat Scand. 1978;58(2):174-190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Quan D. Chapter 177. Benzodiazepines. In: Tintinalli JE, Stapczynski JS, Cline DM, Ma OJ, Cydulka RK, Meckler GD. eds. Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide. 7th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hjermø I, Anderson JE, Fink-Jensen A, Allerup P, Ulrichsen J. Phenobarbital versus diazepam for delirium tremens—a retrospective study. Dan Med Bull. 2010;57(8):1-5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hammond D, Rowe J, Wong A, et al. Patient outcomes associated with phenobarbital use with or without benzodiazepines for alcohol withdrawal syndrome: a systematic review. Hosp Pharm. 2017;52(9):607-616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nisavic M, Nejad SH, Isenberg BM, et al. Use of phenobarbital in alcohol withdrawal management—a retrospective comparison study of phenobarbital and benzodiazepines for acute alcohol withdrawal management in general medical patients. Psychosomatics. 2019;60(5):458-467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]