Abstract

Background

Oncoplastic breast‐conserving surgery (O‐BCS) involves removing the tumour in the breast and using plastic surgery techniques to reconstruct the breast. The adequacy of published evidence on the safety and efficacy of O‐BCS for the treatment of breast cancer compared to other surgical options for breast cancer is still debatable. It is estimated that the local recurrence rate is similar to standard breast‐conserving surgery (S‐BCS) and also mastectomy, but the aesthetic and patient‐reported outcomes may be improved with oncoplastic techniques.

Objectives

Our primary objective was to assess oncological control outcomes following O‐BCS compared with other surgical options for women with breast cancer. Our secondary objective was to assess surgical complications, recall rates, need for further surgery to achieve adequate oncological resection, patient satisfaction through patient‐reported outcomes, and cosmetic outcomes through objective measures or clinician‐reported outcomes.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Breast Cancer Group's Specialized Register, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE (via OVID), Embase (via OVID), the World Health Organization's International Clinical Trials Registry Platform and ClinicalTrials.gov on 7 August 2020. We did not apply any language restrictions.

Selection criteria

We selected randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and non‐randomised comparative studies (cohort and case‐control studies). Studies evaluated any O‐BCS technique, including volume displacement techniques and partial breast volume replacement techniques compared to any other surgical treatment (partial resection or mastectomy) for the treatment of breast cancer.

Data collection and analysis

Four review authors performed data extraction and resolved disagreements. We used ROBINS‐I to assess the risk of bias by outcome. We performed descriptive data analysis and meta‐analysis and evaluated the quality of the evidence using GRADE criteria. The outcomes included local recurrence, breast cancer‐specific disease‐free survival, re‐excision rates, complications, recall rates, and patient‐reported outcome measures.

Main results

We included 78 non‐randomised cohort studies evaluating 178,813 women. Overall, we assessed the risk of bias per outcome as being at serious risk of bias due to confounding; where studies adjusted for confounding, we deemed these at moderate risk.

Comparison 1: oncoplastic breast‐conserving surgery (O‐BCS) versus standard‐BCS (S‐BCS)

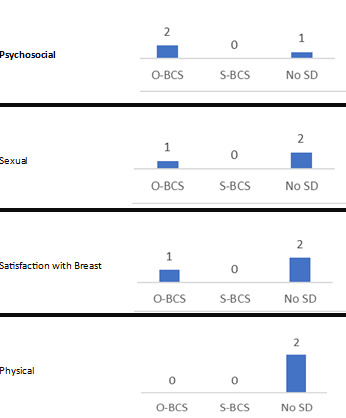

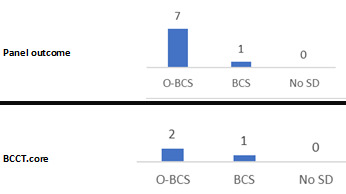

The evidence in the review found that O‐BCS when compared to S‐BCS, may make little or no difference to local recurrence; either when measured as local recurrence‐free survival (hazard ratio (HR) 0.90, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.61 to 1.34; 4 studies, 7600 participants; very low‐certainty evidence) or local recurrence rate (HR 1.33, 95% CI 0.96 to 1.83; 4 studies, 2433 participants; low‐certainty evidence), but the evidence is very uncertain due to most studies not controlling for confounding clinicopathological factors. O‐BCS compared to S‐BCS may make little to no difference to disease‐free survival (HR 1.06, 95% CI 0.89 to 1.26; 7 studies, 5532 participants; low‐certainty evidence). O‐BCS may reduce the rate of re‐excisions needed for oncological resection (risk ratio (RR) 0.76, 95% CI 0.69 to 0.85; 38 studies, 13,341 participants; very low‐certainty evidence), but the evidence is very uncertain. O‐BCS may increase the number of women who have at least one complication (RR 1.19, 95% CI 1.10 to 1.27; 20 studies, 118,005 participants; very low‐certainty evidence) and increase the recall to biopsy rate (RR 2.39, 95% CI 1.67 to 3.42; 6 studies, 715 participants; low‐certainty evidence). Meta‐analysis was not possible when assessing patient‐reported outcomes or cosmetic evaluation; in general, O‐BCS reported a similar or more favourable result, however, the evidence is very uncertain due to risk of bias in the measurement methods.

Comparison 2: oncoplastic breast‐conserving surgery (O‐BCS) versus mastectomy alone

O‐BCS may increase local recurrence‐free survival compared to mastectomy but the evidence is very uncertain (HR 0.55, 95% CI 0.34 to 0.91; 2 studies, 4713 participants; very low‐certainty evidence). The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of O‐BCS on disease‐free survival as there were only data from one study. O‐BCS may reduce complications compared to mastectomy, but the evidence is very uncertain due to high risk of bias mainly resulting from confounding (RR 0.75, 95% CI 0.67 to 0.83; 4 studies, 4839 participants; very low‐certainty evidence). Data on patient‐reported outcome measures came from single studies; it was not possible to meta‐analyse the data.

Comparison 3: oncoplastic breast‐conserving surgery (O‐BCS) versus mastectomy with reconstruction

O‐BCS may make little or no difference to local recurrence‐free survival (HR 1.37, 95% CI 0.72 to 2.62; 1 study, 3785 participants; very low‐certainty evidence) or disease‐free survival (HR 0.45, 95% CI 0.09 to 2.22; 1 study, 317 participants; very low‐certainty evidence) when compared to mastectomy with reconstruction, but the evidence is very uncertain. O‐BCS may reduce the complication rate compared to mastectomy with reconstruction (RR 0.49, 95% CI 0.45 to 0.54; 5 studies, 4973 participants; very low‐certainty evidence) but the evidence is very uncertain due to high risk of bias from confounding and inconsistency of results. The evidence is very uncertain for patient‐reported outcome measures and cosmetic evaluation.

Authors' conclusions

The evidence is very uncertain regarding oncological outcomes following O‐BCS compared to S‐BCS, though O‐BCS has not been shown to be inferior. O‐BCS may result in less need for a second re‐excision surgery but may result in more complications and a greater recall rate than S‐BCS. It seems that O‐BCS may give better patient satisfaction and surgeon rating for the look of the breast, but the evidence for this is of poor quality, and due to lack of numerical data, it was not possible to pool the results of different studies. It seems O‐BCS results in fewer complications compared with surgeries involving mastectomy.

Based on this review, no certain conclusions can be made to help inform policymakers. The surgical decision for what operation to proceed with should be made jointly between clinician and patient after an appropriate discussion about the risks and benefits of O‐BCS personalised to the patient, taking into account clinicopathological factors. This review highlighted the deficiency of well‐conducted studies to evaluate efficacy, safety and patient‐reported outcomes following O‐BCS.

Plain language summary

Oncoplastic breast‐conserving surgery (O‐BCS) for women with primary breast cancer

Background

Traditional surgery for early breast cancer is standard breast‐conserving surgery (S‐BCS) which aims to keep as much of the breast as possible. For women with large tumours compared to their breast size it can be difficult to conserve the breast whilst ensuring all the tumour is removed and may mean that mastectomy is needed. The most important part of surgical treatment for breast cancer is removing all cancer. In recent years, oncoplastic breast surgery techniques have been used to conserve the breast whilst removing breast cancer by applying the principles of plastic surgery, resulting in better cosmetic results. Oncoplastic breast‐conserving surgery (O‐BCS) may also result in better patient satisfaction and quality of life.

Traditionally, surgeons have either preserved the breast tissue by removing the cancerous lump (S‐BCS) or reconstructing immediately after mastectomy. O‐BCS involves removing cancer and either moving/adjusting the remaining breast tissue around (volume displacement) or bringing in tissue from elsewhere to fill the defect after breast cancer removal (volume replacement). There are many techniques that fall under O‐BCS that we have listed in full in other parts of the review; however, all are similar in their principle.

Review question

We reviewed the evidence about the effects of O‐BCS (that is, removing some of the breast tissue and then reconstructing the remaining breast by either mobilising the breast tissue (mammaplasty or volume displacement) or bringing the tissue from elsewhere (partial breast reconstruction or volume replacement)) compared to other S‐BCS (that is, removing the tumour in the breast without the need for further breast adjustment) or mastectomy (that is, removing all the breast tissue with or without reconstruction). We studied the effect on cancer‐related (local recurrence, disease‐free survival and overall survival), quality of life and cosmetic outcomes in women with breast cancer.

Study characteristics

The evidence is current to August 2020. We included 78 studies involving 178,813 patients with breast cancer. We split the studies into those that compared O‐BCS to S‐BCS, O‐BCS to mastectomy alone and O‐BCS to mastectomy with reconstruction. Some studies contributed to more than one comparison.

Key results

It seemed that O‐BCS resulted in similar rates of local recurrence (that is, whether cancer returned in the same breast) and disease‐free survival (free of any breast cancer after initial treatment) when compared to S‐BCS, and resulted in less need for a second re‐excision surgery (which may be required if the tumour is not fully removed in the first operation). O‐BCS may result in more complications and more biopsies in the years after the surgery compared to S‐BCS. It seems that O‐BCS may give better patient satisfaction and surgeon rating for the look of the breast, but the evidence for this is of poor quality, and due to lack of numerical data, it was not possible to pool the results of different studies.

It was not possible to conclude whether or not cancer outcomes of local recurrence and disease‐free survival for O‐BCS were similar to mastectomy with or without reconstruction as there were not many good‐quality studies. It seems O‐BCS has fewer complications than surgeries involving mastectomy.

In practice, the decision to select O‐BCS should be done through shared decision making with the surgeon, discussing the potential risks and benefits.

Certainty of evidence

The certainty of the evidence in this review was very low. The studies had several methodological flaws. Differences between groups in cancer stage and other cancer treatments that were used may have affected the results. This is likely to have an impact on the findings, and future research is needed to investigate the topic further.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

Breast cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer in women worldwide (Bray 2018). Globally, incidence rates are increasing but mortality rates are decreasing with improved treatments, leaving many more breast cancer survivors (WHO 2010). In the UK an estimated 691,000 women are alive after a diagnosis of breast cancer, and this is predicted to rise to 840,000 women in 2020 (Breast Cancer Care 2020). There are over 3.8 million breast cancer survivors in the USA, including those who have finished treatment or are in the process of receiving treatment (BCRF 2019).

For the majority of women with primary breast cancer, the first treatment is breast surgery with curative intent (Breast Cancer Care 2020). As survival improves following breast cancer treatment, it has become imperative to improve quality of life, and long‐term appearance and aesthetic outcomes after surgery have become increasingly relevant.

Description of the intervention

Surgery for breast cancer has evolved considerably over the years, from the radical mastectomy of Halsted 1894 to the development and acceptance of breast‐conserving therapy as standard of care in recent years. Breast‐conserving surgery (BCS) usually refers to lumpectomy or wide local excision (WLE). BCS followed by radiotherapy has been found to be equivalent in disease‐free and overall survival when compared with mastectomy, and hence has become the standard of care for early‐stage breast cancer (Agarwal 2014; Fisher 2002; Van Maaren 2016; Vila 2015). A WLE may be difficult for patients with a large tumour‐to‐breast‐size ratio, resulting in poor cosmetic outcomes or patients may opt for a simple mastectomy (that is, the removal of the breast tissue up to the chest wall) (Regano 2009). There is large variation across countries in the rates of BCS (Munzone 2014; Sun 2018).

The primary goal of oncological surgery is cancer resection; that is, where the tumour, along with a margin of normal tissue is excised. There is also, however, increasing awareness that aesthetic outcomes of these procedures are extremely important. Patient expectations are increasing as they become aware that they need not be left with deformities after breast cancer surgery. Good aesthetic outcomes have been linked with significant improvements in patient satisfaction and quality of life (Kim 2015; Waljee 2008).

There are many breast reconstruction options for aesthetic improvement. Women being offered a mastectomy have the option of full breast reconstruction, using either implants or their own (autologous) tissue. Breast reconstruction can be done at the same time as the mastectomy (one‐stage) or as a separate operation (two‐stage). For women undergoing BCS for large tumours, the options include either volume displacement or partial volume replacement techniques using either implants or autologous tissue (ACS 2016).

Oncoplastic breast‐conserving surgery (O‐BCS) is the term used for oncological resection (breast tumour excisions) combined with plastic surgery techniques (Almasad 2008; Clough 2003; Rainsbury 2007; Regano 2009). O‐BCS can be broadly divided into the two fundamentally different techniques: 1) volume displacement techniques use breast tissue (glandular or dermoglandular) from the same breast and places (redistributes) it into the surgical site (also known as mammoplasty); and 2) volume replacement techniques use tissue, other than the breast, to compensate for volume loss after breast tumours have been excised.

The uniting principle of these two techniques is to conserve the breast shape/size.

Volume displacement techniques can include various techniques (Holmes 2011), for example:

wise pattern therapeutic mammaplasty;

vertical scar mammaplasty (and its variations);

circumareolar/Benelli’s/round block mammoplasty;

racquet handle/lateral mammaplasty.

Similarly, there are many techniques for autologous partial volume replacement techniques. The following techniques are recognised as partial volume replacement techniques, where the differentiating factor between which flap is used is usually the location of the tumour.

-

Defects in the lower aspects of the breast can be addressed using local flaps such as:

abdominal adipofascial flaps (Kijima 2014; Ogawa 2007);

-

thoracoepigastric flaps (Hamdi 2014; Kijima 2011; Takeda 2005);

superior epigastric artery perforator flap;

medial intercostal artery perforator;

internal mammary artery perforator;

anterior intercostal artery perforator.

-

Defects in the lateral half of the breast can be reconstituted with lateral chest wall perforator flaps such as:

lateral intercostal artery perforator (Hamdi 2006; Hu 2018);

lateral thoracic artery perforator (McCulley 2015);

thoracodorsal artery perforator flap (Munhoz 2011).

-

Defects in any breast quadrant can be addressed using distant flaps. Most often these are pedicled flaps, but free flaps could also be used for partial breast reconstruction such as:

mini‐latissimus dorsi (Raja 1997);

omental flaps (Zaha 2014);

other free flaps for partial breast reconstruction e.g. transverse upper gracilis flaps (McCulley 2011).

Many early‐stage breast cancers can be successfully treated by WLE; however, the lesions with large tumour‐to‐breast‐size ratio remain a challenge for breast surgeons to treat with BCS alone. O‐BCS allows the excision of tumours that cannot be excised by, or would result in poor cosmetic outcomes from S‐BCS. It allows these women to avoid mastectomy.

In this Cochrane Review, we will compare any O‐BCS technique to other surgical techniques used for BCS because any of the aforementioned techniques may be offered to women with breast cancer under varying circumstances. For small cancers, it is likely that WLE with or without partial reconstruction (using either autologous tissue or an implant) will be offered. In contrast, for large cancers, the options could include WLE with or without partial reconstruction; or mastectomy with or without reconstruction.

How the intervention might work

For women with early‐stage breast cancer, studies have shown that there is no detectable difference in overall survival or disease‐free survival in those who have BCS plus radiotherapy and those who have a mastectomy (Poggi 2003; Van Maaren 2016). There has been increased adoption of the practice in many countries to facilitate breast‐conserving therapy and avoid unnecessary mastectomies (Kaufman 2019). The emphasis remains on safe and adequate cancer resection, whilst aiming to achieve better aesthetic outcomes to improve quality of life.

There is evidence indicating that cosmesis, patient satisfaction and quality of life improve with BCS compared to mastectomy (Kim 2015; Waljee 2008). The options for surgical resection for breast cancer are dictated by the size of the tumour. There is an indirect correlation between the percentage of breast volume excised and cosmesis, which can have an impact on the satisfaction levels after BCS (Cochrane 2003). O‐BCS techniques aim to keep the breast shape and size similar despite oncological resection; therefore it would be logical to expect better patient satisfaction.

Why it is important to do this review

Although oncoplastic surgery has rapidly gained acceptance and is widely practised, cohesive evidence is still lacking on both the short‐term and long‐term outcomes, particularly for partial breast reconstruction.

Since the most recent systematic review of oncoplastic breast surgery concluded its search in 2015 (Yiannakopoulou 2016), there have been over 30 articles published regarding partial breast reconstruction. A summary of evidence from this literature will help clinicians understand the indications and clinical, oncological and cosmetic outcomes of such techniques. This Cochrane Review will update our understanding of this rapidly evolving area of clinical practice and address the questions unexplored by previous reviews. In addition, this review will focus on volume displacement and replacement techniques as separate subsets of O‐BCS, and compare these techniques with other alternatives.

Objectives

Our primary objective was to assess oncological control outcomes following O‐BCS compared with other surgical options for women with breast cancer. Our secondary objective was to assess surgical complications, recall rates, need for further surgery to achieve adequate oncological resection, patient satisfaction through patient‐reported outcomes, and cosmetic outcomes through objective measures or clinician‐reported outcomes.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We planned to include all randomised controlled trials (RCTs) assessing oncoplastic breast‐conserving surgery (O‐BCS) but anticipated that there would be no RCTs on the topic. We, therefore, expanded the inclusion criteria to include comparative non‐randomised studies (i.e. cohort studies, case‐control studies and prospectively designed patient registries).

We included studies published in all languages from 1980 onwards as this is the date at which partial breast reconstruction was introduced.

We excluded single‐arm studies, expert opinion and duplicate studies.

Types of participants

We included women with primary breast cancer who underwent any O‐BCS using either volume displacement or partial replacement breast reconstruction for cancer compared with women who underwent any other surgical technique for cancer.

We excluded men and people who have undergone surgery for benign breast conditions.

Types of interventions

Experimental interventions

Any oncoplastic breast‐conserving surgery techniques including:

-

volume displacement techniques

wise pattern therapeutic mammaplasty

vertical scar mammaplasty (and its variations)

circumareolar/Benelli’s/Round block mammoplasty

racquet handle/lateral mammaplasty

-

partial volume replacement techniques

abdominal adipofascial flaps/advancement flaps

-

lateral chest wall perforator flaps

lateral intercostal artery perforator flap

lateral thoracic artery perforator

thoracodorsal artery perforator flap

latissimus dorsi mini‐flap

-

thoracoepigastric flaps

superior epigastric artery perforator flap

medial intercostal artery perforator

internal mammary artery perforator

anterior intercostal artery perforator

omental flaps

free flaps for partial breast reconstruction

We included any other techniques if mentioned in the literature.

Comparator interventions

Any other surgical treatment. The comparators were stratified into partial resection and mastectomy. These include:

standard breast‐conserving surgery (S‐BCS) e.g. wide local excision (WLE), quadrantectomy, segmentectomy, partial mastectomy;

partial volume replacement using non‐autologous tissue;

mastectomy with no reconstruction;

mastectomy with breast reconstruction using an implant alone;

mastectomy with breast reconstruction using autologous tissue including pedicled and free flaps.

The main analyses were:

any O‐BCS versus S‐BCS

any O‐BCS versus mastectomy without reconstruction

any O‐BCS versus mastectomy with reconstruction procedures

Co‐interventions

We recognised that some women with breast cancer may also undergo hormonal therapy, chemotherapy or radiotherapy, or a combination of therapies. We collected data on whether patients received these co‐interventions; we did not, however, conduct a subgroup analysis as no study reported outcomes based on these. This information can be found in Table 4, which describes confounding variables; differences in these co‐interventions informed the risk of bias for each study.

1. Confounding variables.

| Study name | Clinicopathological variables: significantly different | Clinicopathological variables: demonstrated balance | Clinicopathological variables: matched | Clinicopathological variables: statistical adjustment | Co‐interventions: significantly different | Co‐interventions: demonstrated balance | Co‐interventions: matched | Co‐interventions: statistical adjustment |

| Acea‐Nebril 2005 | Size (BCS) | Age (BCS, Mx), size (Mx) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Acea‐Nebril 2017 | Age, menopausal status, tumour size, tumour stage, axillary lymph node status, location of tumour, multifocality | BMI, histological type, immunohistochemical receptors | ‐ | ‐ | Neoadjuvant CT, axillary management | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Acosta‐Marin 2014 | Preoperative bra size, tumour size, | Age, BMI | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Amitai 2018 | Age, axillary node status, immunohistochemical receptors, | Smoking status, BMI, histological type, tumour size | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Adjuvant RT | ‐ | ‐ |

| Angarita 2020 | Age, BMI, race, smoking status, alcohol consumption, COPD, PCI, HTN, bleeding disorder, steroid use, previous vascular disease, previous cardiac surgery, dialysis,hemiplegia, TIA, CVA, ASA status, histological type | Weight loss, transfusion, diabetes mellitus | ‐ | ‐ | Axillary management, neoadjuvant chemotherapy, anaesthetic technique | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Atallah 2015 | Age, BMI, menopausal status, tumour size, location, histological type, immunohistochemical receptors | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |

| Bali 2018 | Tumour size | Age, histological type, immunohistochemical receptors, tumour locations | ‐ | ‐ | Neoadjuvant CT, adjuvant CT | Adjuvant RT | ‐ | ‐ |

| Borm 2019 | Age, tumour size, tumour grade, axillary node status, immunohistochemical receptors (ER status), | Immunohistochemical receptors (PR, HER2) | ‐ | ‐ | Adjuvant CT, adjuvant ET | Neo‐adjuvant CT, adjuvant RT | ‐ | ‐ |

| Carter 2016 | Age (BCS, Mx, Mx+R), BMI (BCS), tumour size (BCS, Mx, Mx+R), tumour stage (BCS, Mx, Mx+R), tumour grade (BCS), axillary node status (BCS), immunohistochemical receptors (HER2), multifocality (BCS, Mx, Mx+R). | BMI (Mx, Mx+R), Tumour grade (Mx, Mx+R), axillary node status (Mx, Mx+R), immunohistochemical receptors (ER, PR‐ Mx), lymphovascular invasion | In LR calculation multivariate analysis | ‐ | Neoadjuvant CT (BCS, Mx, Mx+R), adjuvant RT (Mx/MxR), adjuvant CT (BCS, Mx, Mx+R) | Adjuvant RT (BCS) | ‐ | ‐ |

| Cassi 2016 | ‐ | Age, BMI, tumour size | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Adjuvant RT | ‐ | ‐ |

| Chakravorty 2012 | Histological type, tumour size, grade, sample weight | Age, axillary node status | ‐ | ‐ | Neoadjuvant CT | Adjuvant RT, adjuvant CT | ‐ | ‐ |

| Chauhan 2016 (1) | Age, tumour size, tumour location | Histological type, grade, axillary node status, immunohistochemical receptors | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Chauhan 2016 (2) | Age, tumour size, tumour location | Axillary node status | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Crown 2015 | Tumour size, immunohistochemical receptors | Age, histological type | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Adjuvant RT | ‐ | ‐ |

| Crown 2019 | Tumour size, immunohistochemical receptors | Age, smoking, BMI, histological type | ‐ | ‐ | Neoadjuvant CT | Adjuvant CT | ‐ | ‐ |

| DeLorenzi 2016 (1) | Tumour size and multifocality | Menopausal, histological type, grade, axillary node status, immunohistochemical receptors, lymphovascular invasion | Age (within 5 years), year of surgery (within 2 years), tumour size (T) and multifocality | Adjuvant CT, Adjuvant RT, Adjuvant ET | ‐ | ‐ | ||

| DeLorenzi 2016 (2) | Multifocality | Grade, immunohistochemical receptors | Age (within 5 years), year of surgery (within 2 years), number of positive axillary lymph nodes, tumour subtype, multifocality | Adjuvant RT | Adjuvant CT, Adjuvant ET | ‐ | ‐ | |

| DeLorenzi 2018 | Menopausal, grade | Age, BMI, tumour size, immunohistochemical receptors, multifocality | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Adjuvant RT, any adjuvant therapy | ‐ | ‐ |

| Di Micco 2017 | Age, axillary node status | Smoking status, BMI, histological type, tumour size, immunohistochemical receptor, tumour location | Radiation boost, adjuvant CT | Neoadjuvant CT, adjuvant ET, axillary management, adjuvant RT | ||||

| Dolan 2015 | Age, tumour size, axillary node status | Histological type, grade, immunohistochemical receptor | ‐ | ‐ | Adjuvant CT | Adjuvant RT, adjuvant ET, axillary management | ‐ | ‐ |

| Down 2013 | Tumour size | Age, histological type, grade | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Adjuvant RT | ‐ | ‐ |

| Eichler 2013 | Tumour size | Age, histological type, grade | ‐ | ‐ | Neoadjuvant CT | Adjuvant CT | ‐ | ‐ |

| Fan 2019 | ‐ | Histological type | Age, BMI, stage | ‐ | ‐ | Neoadjuvant CT, adjuvant RT, adjuvant CT, adjuvant ET | ‐ | |

| Farooqi 2019 | Tumour size, | Age, histological type | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Neoadjuvant CT | ‐ | ‐ |

| Gendy 2003 | Histological type, tumour size | Age, grade, axillary node status | ‐ | ‐ | Adjuvant RT | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Gicalone 2007 (1) | Age | BMI, histological type, tumour size, grade, axillary node status, immunohistochemical receptor | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Gicalone 2007 (2) | Age | BMI, tumour size, tumour location | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |

| Gicalone 2015 | ‐ | Age, smoking status, diabetes, BMI, other medical comorbidities, histological type, tumour size | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |

| Gulcelik 2013 | ‐ | Age, tumour size, immunohistochemical receptor | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Adjuvant CT, Adjuvant ET, axillary management, adjuvant RT | ||

| Hamdi 2008 | Age, histological type, tumour size, | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Axillary management | ‐ | ‐ |

| Hart 2015 | Age, BMI | Stage | ‐ | ‐ | Adjuvant RT | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Hashimoto 2019 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Hilli‐Betz 2014 | Tumour size, preoperative bra size | Axillary node status | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Axillary management | ‐ | ‐ |

| Hu 2019 | ‐ | Age, tumour size, immunohistochemical receptor | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Neoadjuvant CT, axillary management | ‐ | ‐ |

| Jiang 2015 | ‐ | Age, weight, histology type,tumour size, grade, stage, tumour location | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Kahn 2013 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Adjuvant CT (BCS, Mx, Mx+R) | ‐ | ‐ |

| Keleman 2019 | Preoperative bra size, axillary node status | Age, smoking status, diabetes, BMI, type of cancer, tumour size, grade, stage, immunohistochemical receptor | ‐ | ‐ | Neoadjuvant CT, adjuvant CT, adjuvant ET, axillary management | Adjuvant RT | ‐ | ‐ |

| Kelsall 2017 | ‐ | Axillary node status | Age, tumour size, date of surgery, breast size | ‐ | Adjuvant RT | Neoadjuvant CT | Adjuvant CT, adjuvant ET | ‐ |

| Kimball 2018 | Age, medical comorbidities, histological type | BMI | ‐ | ‐ | Adjuvant RT, adjuvant CT, axillary management | ‐ | ‐ | |

| Klit 2017 | Age (BCS, Mx), BMI (BCS, Mx), tumour size (BCS, Mx), axillary node status (BCS, Mx) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Axillary management, Adjuvant RT (BCS) | Adjuvant CT (BCS, Mx), Adjuvant RT (Mx) | ‐ | ‐ |

| Lansu 2014 | ‐ | Age, tumour size, tumour location | ‐ | ‐ | Neoadjuvant CT | Adjuvant CT, Adjuvant ET, axillary management, adjuvant RT | ‐ | |

| Lee 2018 | Tumour size (BCS, Mx, Mx+R), stage (BCS, Mx, Mx+R) | Age (BCS, Mx, Mx+R), BMI (BCS, Mx, Mx+R) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Losken 2009 | Age, histological type, stage | BMI | ‐ | ‐ | Adjuvant CT, axillary surgery | Adjuvant RT | ‐ | ‐ |

| Losken 2014 | Age, BMI | Histological type, tumour size, stage, immunohistochemical receptor | ‐ | ‐ | Neoadjuvant CT | ‐ | ‐ | |

| Malhaire 2015 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Mansell 2015 | Age (both), histological type (BCS), tumour size (BCS), grade (BCS), axillary node status (BCS), immunohistochemical receptor (ER, PR) | Histological type (Mx), tumour size (Mx), grade (Mx), axillary node status (Mx), immunohistochemical receptor (HER2) | ‐ | ‐ | Adjuvant RT (MxR), adjuvant CT (BCS), adjuvant ET (BCS) | Adjuvant RT (BCS), adjuvant CT (MxR), adjuvant ET (MxR) | ‐ | ‐ |

| Mansell 2017 | Age (both), histological type (BCS), tumour size (BCS), grade (BCS), axillary node status (BCS), immunohistochemical receptor (ER) | Histological type (Mx), tumour size (Mx), grade (Mx), axillary node status (Mx), immunohistochemical receptor (HER2) | ‐ | ‐ | Adjuvant RT (MxR), adjuvant CT (BCS), adjuvant ET (BCS) | Adjuvant RT (BCS), adjuvant CT (MxR), adjuvant ET (MxR) | ‐ | ‐ |

| Matrai 2014 | Tumour size | Age, histological type, grade, tumour location, bra size, immunohistochemical receptor, axillary lymph node status | Matched of clinicopathological factors ‐ details not given | ‐ | Adjuvant CT | Axillary surgery, adjuvant RT, adjuvant ET | ‐ | ‐ |

| Mazouni 2013 | Immunohistochemical receptor (ER), tumour location | Histological type, tumour size, grade, axillary node status, immunohistochemical receptor (PR) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Axillary surgery, neoadjuvant CT, adjuvant RT | ‐ | ‐ |

| Morrow 2019 | Age (all), histological type (BCS, Mx), tumour size (BCS, Mx), grade (BCS, Mx), axillary node status (Mx, MxIR) | Histological type (MxIR), tumour size (MxIR), grade (MxIR), axillary node status (BCS), immunohistochemical receptors | ‐ | ‐ | Adjuvant CT (BCS), Adjuvant RT (all) | Adjuvant CT (Mx, MxIR), adjuvant ET (Mx, MxIR) | ‐ | ‐ |

| Mukhtar 2018 | Tumour size | "No significant difference in patient or tumour characteristics" | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Mustonen 2004 | Tumour size | Age | ‐ | ‐ | Adjuvant, RT | Adjuvant CT | ‐ | ‐ |

| Nakada 2019 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Nakagomi 2019 | Age, tumour size, stage | Histological type, axillary node status, immunohistochemical receptor status | ‐ | ‐ | Neoadjuvant CT | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Niinikoski 2019 (2) | Age, tumour size, grade, axillary node status, immunohistochemical status (ER, TN), multifocality, | Histological type, immunohistochemical receptor status (PR, HER2) | ‐ | ‐ | Adjuvant CT, adjuvant ET | Adjuvant RT, axillary management | ‐ | ‐ |

| Ojala 2017 | Tumour size, tumour location, axillary node status, multifocality, histological type, | Age, grade | ‐ | ‐ | Axillary management | Adjuvant RT | ‐ | ‐ |

| Ozmen 2016 | Age, BMI, multifocality | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Adjuvant RT | ‐ | ‐ |

| Ozmen 2020 | Age, menopausal status, BMI, tumour size, grade, axillary node status, immunohistochemical receptor status (ER), multifocality | histological type, immunohistochemical receptor status (PR, HER2, TN) | ‐ | ‐ | Adjuvant RT, axillary management | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Palsodittlir 2018 | Age, smoking status, tumour size | Histological type, axillary node status | ‐ | ‐ | Adjuvant ET | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Peled 2014 | Age, BMI | Smoking status, diabetes | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Neoadjuvant CT | ‐ | ‐ |

| Piper 2016 | Tumour stage | BMI, histological type | Age | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| PlaFarnos 2018 | Multifocality | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Previous breast surgery | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Potter 2020 | Age (Mx, Mx+R), diabetes (Mx, Mx+R), BMI (Mx, Mx+R), other medical comorbidities ( Mx, Mx+R), histological type (Mx, Mx+R), grade (Mx, Mx+R), axillary node status (Mx, Mx+R), immunohistochemical receptors (BCS, Mx, Mx+R), multifocality (BCS, Mx, Mx+R) | Smoking status (Mx, Mx+R) | ‐ | ‐ | Neoadjuvant CT (Mx, Mx+R), adjuvant RT (Mx, Mx+R), adjuvant CT (Mx, Mx+R), axillary surgery (Mx, Mx+R) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Ren 2014 | ‐ | Histological type, tumour location | Age, tumour size, axillary lymph node status, immunohistochemical receptor, (ER, HER2) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Rose 2019 | Menopausal status, axillary node status | ‐ | ‐ | Age, lymphovascular invasion, grade, tumour size, multifocality, immunohistochemical receptor (ER, HER2) | Axillary surgery | Adjuvant RT, adjuvant CT, adjuvant ET | ‐ | ‐ |

| Rose 2020 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Age, follow‐up time, menopausal status, tumour size, bra size, tumour location, bra size, BMI, smoking status, marital status, living arrangement and education | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Adjuvant RT, adjuvant CT, adjuvant ET, immunotherapy, axillary surgery |

| Santos 2015 | BMI, histological type, axillary node status, | Age, menopausal status, tumour size, grade, immunohistochemical receptor, tumour location | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Axillary surgery | ‐ | ‐ |

| Scheter 2019 | Age, smoking status, tumour size, , | Preoperative bra size, axillary lymph node status | Diabetes, BMI | ‐ | ‐ | Axillary surgery, adjuvant CT, adjuvant ET, adjuvant RT | ‐ | ‐ |

| Sherwell‐Cabello 2006 | Tumour size | Age, other comorbidities, axillary node status, tumour location | ‐ | ‐ | Neoadjuvant CT | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Srivastava 2018 | ‐ | ‐ | Margin of excision | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Tang 2016 | Age, BMI, tumour size, stage | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Axillary management | ‐ | ‐ | |

| Tenofsky 2014 | ‐ | Age, BMI, tumour size | ‐ | ‐ | Adjuvant RT | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Tong 2016 | Age, diabetes, BMI, other comorbidities, preoperative bra size | Smoking status, tumour size, stage | ‐ | ‐ | Neoadjuvant RT, adjuvant RT | Neoadjuvant CT, adjuvant CT | ‐ | ‐ |

| Viega 2010 | ‐ | Age, BMI, tumour location | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Adjuvant RT, adjuvant CT | ‐ | ‐ |

| Viega 2011 | ‐ | Age, BMI, tumour size, tumour location | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Adjuvant RT, adjuvant CT, axillary management | ‐ | ‐ |

| Vieira 2016 | ‐ | Age, histological type, stage, immunohistochemical receptor | Tumour size, grade | ‐ | ‐ | Neoadjuvant CT, adjuvant RT | ‐ | ‐ |

| Wijgman 2017 | Tumour size, tumour location | Age, menopausal status, smoking, diabetes, BMI, other medical comorbidities, histological type, sample volume resected, sample weight resected | ‐ | ‐ | Adjuvant CT, adjuvant ET | Neoadjuvant CT, adjuvant RT, axillary surgery | ‐ | ‐ |

| Wong 2017 | Tumour size | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Zhou 2019 | Tumour size | Age, BMI, preoperative bra size, histological type, tumour location, multifocality, axillary node status | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Adjuvant RT, axillary management | ‐ | ‐ |

BCS: breast‐conserving surgery BMI: body mass index CT: chemotherapy ER: oestrogen receptor ET: endocrine therapy HER2: human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 IR: immediate reconstruction Mx: mastectomy PR: progesterone receptor R: reconstruction RT: radiotherapy TN: triple negative

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

The primary outcomes focused on oncological control by O‐BCS by assessing the following.

Local recurrence: locoregional recurrence (that is, ipsilateral breast tumour recurrence), defined as cancer detected in the same breast where cancer had been diagnosed. Some studies reported this as local recurrence‐free survival ‐ defined as the time from the date of treatment to the first date of local relapse.

Disease‐free survival: breast cancer‐specific disease‐free survival, defined as the time from the date of completing initial treatment (that is, completing the surgical procedure) to the first date of a local, regional, or distant relapse, diagnosis of a second primary breast cancer, or death due to this.

Overall survival: overall survival, defined as the time from the date of treatment to death from any cause, or number of deaths from any cause.

Follow‐up was described as 1 year, 1 to 5 years, 5 years, and 10 years if reported as dichotomous outcomes; or longest reported follow‐up if hazard ratios were reported.

Secondary outcomes

The secondary outcomes focused on oncological, surgical and cosmetic outcomes by assessing the following.

Re‐excision rates: need for further breast surgery due to inadequate cancer resection (for example, re‐excision for further margin resection or completion mastectomy).

Complications: surgical complications, for example, flap necrosis, infection, wound dehiscence and any other complications reported in the literature.

Recall rates: defined as abnormal surveillance on mammogram resulting in additional imaging or biopsy.

Time to adjuvant therapy: time in days from surgery to initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy.

Patient‐reported outcome measures: such as patient satisfaction, that derive from validated questionnaires (for example, Breast‐Q; Cohen 2016).

Cosmetic evaluation: surgeon‐reported cosmetic outcomes that derive from subjective or objective validated scales (for example, the Harris scale and Breast Analyzing Tool; Harris 1979; Krois 2017).

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the following databases on 7 August 2020.

The Cochrane Breast Cancer's Specialised Register. Details of the search strategies used by the Group for the identification of studies and the procedure used to code references are outlined on the Group's website (breastcancer.cochrane.org/sites/breastcancer.cochrane.org/files/public/uploads/specialised_register_details.pdf). We extracted trials with the following key words and considered them for inclusion in the review: abdominal adipofascial flaps, lateral chest wall perforator flaps, lateral intercostal artery perforator flap, latissimus dorsi mini‐flap, omental flaps, thoracoepigastric flaps, superior epigastric artery perforator flap, medical intercostal artery perforator, internal mammary artery perforator, anterior intercostal artery perforator, advancement/random pattern or rotation flaps, free flaps for partial breast reconstruction, breast‐conserving surgery, oncoplastic breast surgery, partial volume replacement breast, partial breast reconstruction and partial mastectomy. We will search for papers including women with breast cancer who are undergoing any kind of oncoplastic breast‐conserving surgery, as it is often the case for breast‐conserving surgeries to be grouped together.

CENTRAL (in the Cochrane Library, August 2020). See Appendix 1.

MEDLINE (via Ovid SP) from 1980 to August 2020. See Appendix 2.

Embase (via Ovid SP) from 1980 to August 2020. See Appendix 3.

The World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) search portal (apps.who.int/trialsearch/Default.aspx) for all prospectively registered and ongoing trials. See Appendix 4.

ClinicalTrials.gov. See Appendix 5.

Searching other resources

Bibliographic searching

We screened the studies in the reference lists of identified relevant trials or reviews (for example Chen 2018; De La Cruz 2016; Haloua 2013; Losken 2014; Yoon 2016). We obtained a copy of the full‐text article for each reference reporting a potentially eligible study.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

We uploaded our references into Covidence. Two review authors (AN and JH) independently examined each title and abstract to determine whether reports appear to meet the inclusion criteria based on the protocol, and resolved any differences by discussion. For those studies with multiple publications of duplicate data sets, the study with the shorter follow‐up time or fewer participant numbers for outcomes of interest was excluded so as not to duplicate data in the analysis.

We obtained copies of potentially eligible reports and two review authors (AN and JH) examined the full‐text articles independently. We used Cochrane Task Exchange to help with translations for six studies (2 Spanish, 1 French, 1 Hungarian and 2 Chinese (Mandarin)). We did not have any potentially relevant studies that we were unable to translate. The review author team reviewed all potentially eligible reports and decided which studies should be included in the review. We recorded the selection process in a PRISMA flow diagram (Page 2021); we recorded excluded studies in the 'Characteristics of excluded studies table.

Data extraction and management

The review author team designed and agreed upon the uniform criteria for data extraction and create a standardised form in Excel prior to review commencement. Three review authors (AN, JH and SA) independently undertook data extraction, with at least two authors reviewing each study. Any differences were resolved by discussion, and when needed we consulted a fourth review author (PR) to help resolve any disagreements. For those studies with more than one publication, we extracted data from all publications and considered the version with the longest follow‐up as the primary reference for the study and excluded the other from the analysis.

We tabulated the study characteristics for each included study to determine whether we were able to synthesise these data and present them in text or tabular form. We included the following information from the individual studies on standardised data extraction forms.

-

General Information

Author names, countries and year of publication

Study design and level of evidence

Conflicts of interest and funding

-

Demographics

Number of participants

Number of breasts treated

Age of participants

Smoking history

History of diabetes

History of steroid intake or immunosuppression

body mass index (BMI)

-

Breast factors

Preoperative breast/bra size

-

Oncological parameters

Type of cancer (invasive or in situ)

Grade

Stage

Axillary nodal status

Hormone receptor status (oestrogen receptor, progesterone receptor), HER2 status

Size of tumour including any associated additional foci

Location of tumour (which quadrant)

-

Tumour–nipple distance

Solitary, multifocal or multicentric

Presence of lymphovascular invasion

-

Cancer treatment

Adjuvant radiotherapy

Prior neoadjuvant or adjuvant chemotherapy

Previous breast surgery

-

Technical surgical details

Incision used

Reconstruction performed

Flap included a skin paddle used to reconstruct a skin defect

-

Postsurgical details

Median follow‐up duration

Loss to follow‐up expressed as a percentage

-

Primary outcomes as described above

Local recurrence

Survival (for example, disease‐specific (breast cancer) and overall survival)

-

Secondary outcomes, as described above

Patient‐reported outcome measures (for example, patient satisfaction)

Time to adjuvant therapy (days)

Surgical complications

Recall rates

Need for further surgery to address aesthetics/symmetry

Surgeon‐reported cosmetic outcomes

-

Surgical outcomes

-

Early complications, for example:

completion mastectomy rates

flap necrosis

infection

readmission

generic surgical complications

-

Late complications, for example:

correction of symmetry (contralateral augmentation/reduction or nipple reconstruction)

correction of deformity (lipomodelling, scar revision etc.)

any other breast procedures

-

-

Cosmetic outcomes

Clinician‐reported

Patient‐reported outcome measures, such as satisfaction and quality of life

Any symmetrisation surgery

-

For non‐randomised studies

Methods used to control for confounders

Adjusted and unadjusted outcome measures

List of variables included in analyses for adjusted estimates

If reports related to the same study appear in multiple publications, we combined them under the overall study ID.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We planned to use Cochrane's risk of bias tool for RCTs (RoB 1; Higgins 2011) and the ROBINS‐I tool for non‐randomised studies (Sterne 2016). We planned to compare study protocols with final papers where possible and would have noted if key information was missing across all study types. However, there were no RCTs in this review nor any protocols.

Non‐randomised studies

Three review authors (AN, SA and JH) applied the ROBINS‐I tool, as described in Sterne 2016, to assess the risk of bias of effect of assignment in the results of non‐randomised studies that compare health effects of two or more interventions. We resolved disagreements by discussion. We used the ROBINS‐I tool for cohort studies, case‐control studies and prospective patient registries. We completed separate ROBINS‐I tables to generate an overall risk of bias for each outcome: local recurrence, disease‐free survival, overall survival, re‐excision rates, complications, recall rates, time to adjuvant therapy, cosmetic evaluation, and patient‐reported outcome measures. We assessed the risk of bias according to the following domains.

Pre‐intervention bias

-

Due to confounding: for example comorbidities of patients, associated ductal carcinoma in situ, the predominance of small tumour size or small tumour:breast ratio (no established cut‐offs exist for defining size), lack of pathology reporting in published literature, smoking status, age, ethnicity, genetic risk for breast cancer.

For oncological outcomes (local recurrence, disease‐free survival and overall survival we would expect the following confounders to be controlled for: oncological parameters of tumour (type, size, grade, stage, nodal status, hormonal status) and cancer treatment.

For re‐excision rates we would expect the following confounders to be controlled for: oncological parameters of tumour (especially tumour size and location) and cancer treatment.

For complication rates we would expect the following confounders to be controlled for: age, comorbidities, oncological parameters of tumour (especially stage and size) and cancer treatment (especially axillary surgery and adjuvant radiotherapy).

For time to adjuvant therapy we would expect the following confounders to be controlled for: comorbidities and cancer treatment.

For patient‐reported outcome measures we would expect the following confounders to be controlled for: oncological parameters of tumour (especially tumour size and location) and cancer treatment.

For cosmetic evaluation, we would expect the following confounders to be controlled for: oncological parameters of tumour (especially tumour size and location) and cancer treatment.

In the selection of participants into the study

At‐intervention bias

In the classification of the intervention

Post‐intervention bias

-

Due to deviations from the intended intervention

This includes bias due to differences in surgeon technique and experience between control and intervention within studies.

Due to missing data

In the measurement of outcomes: for example, cosmetic assessment being subjective and not using validated anonymised questionnaires

In the selection of the reported results

We scored each of these domains as having low, moderate, serious, or critical risk of bias. Based on these scores, we determined an overall risk of bias for each study per outcome. If we graded any domain as serious, we deemed the overall risk of bias as serious.

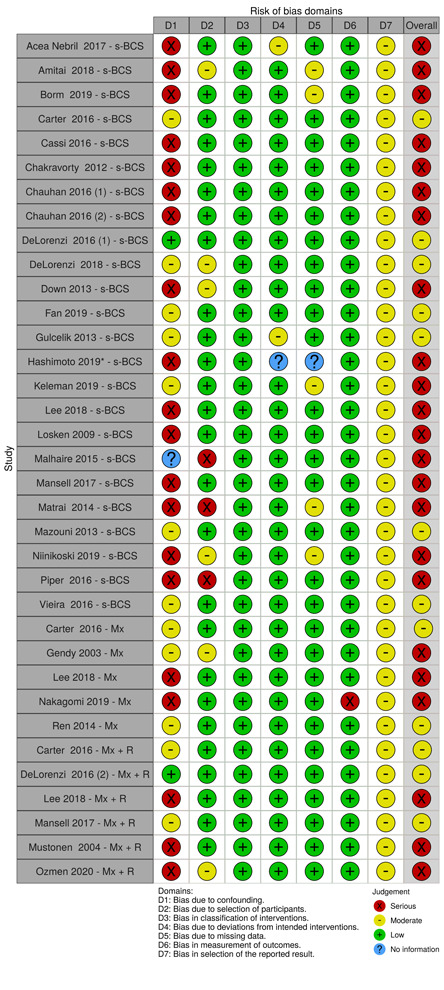

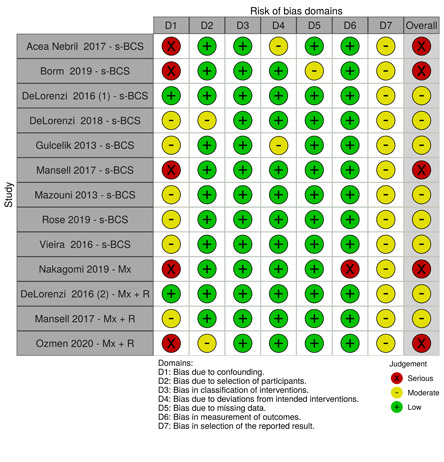

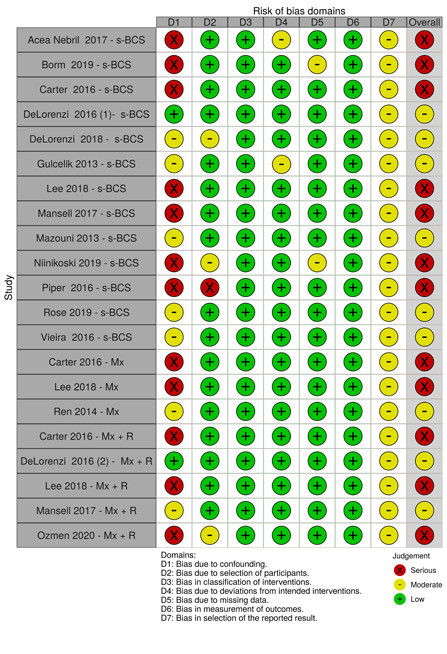

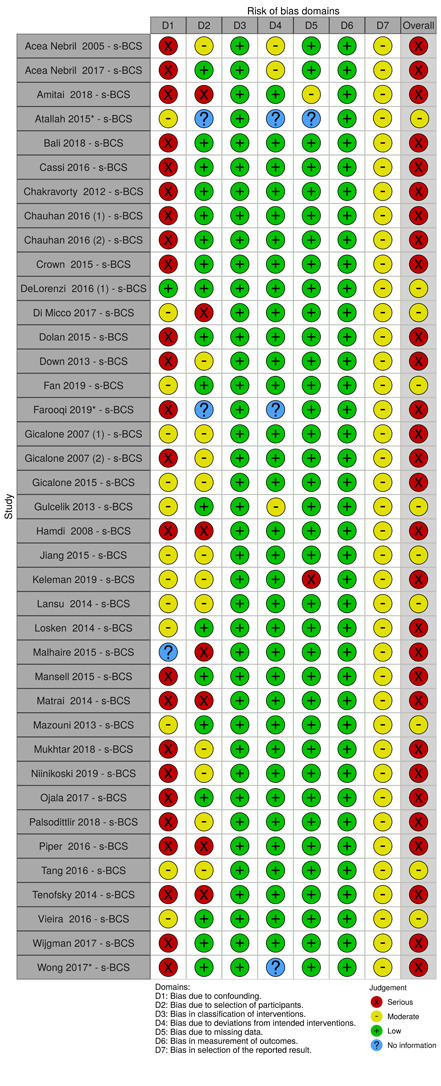

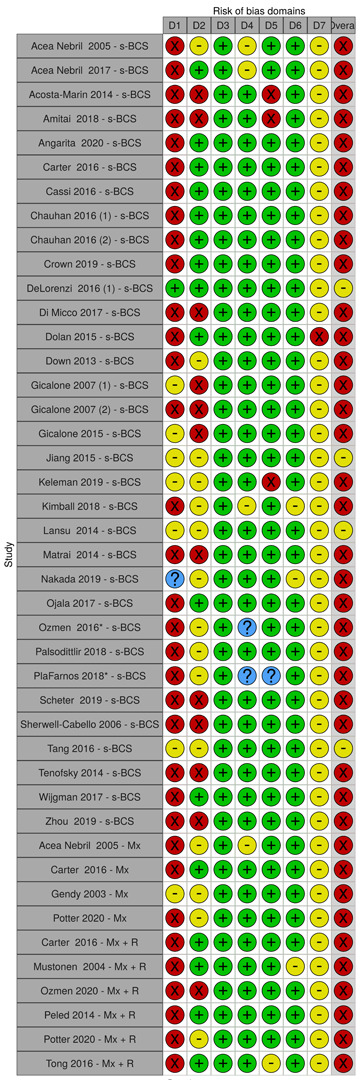

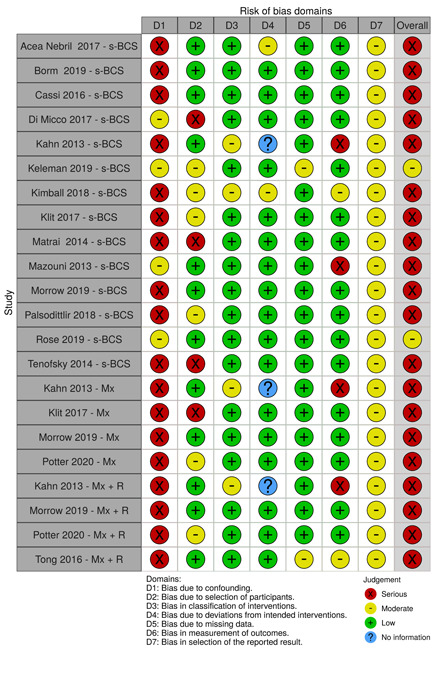

We summarised the risk of bias judgements across different studies for each of the domains listed and summarised results in separate risk of bias tables (Table 5; Table 6; Table 7; Table 8; Table 9; Table 10; Table 11; Table 12; Table 13).

2. Risk of bias for local recurrence.

| Study | Control | Confounding | Selection | Classification of intervention | Deviations from intended intervention | Missing data | Measurement of outcomes | Selection of reported results | Overall |

| Acea‐Nebril 2017 | S‐BCS | Serious | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Low | Moderate | Serious |

| Some clinicopathological variables significantly different (age, menopausal status, tumour size, tumour stage, axillary lymph node status, location of tumour, multifocality). Some co‐interventions balanced (neoadjuvant CT and axillary management), some missing | All participants eligible included | Classification of interventions clear and determined at the start of intervention. Some aspects may be determined retrospectively | Deviation from intended co‐intervention (adjuvant therapy time) | All patients followed up | Objective outcome measure | No indication of selected reporting | |||

| Amitai 2018 | S‐BCS | Serious | Moderate | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Moderate | Serious |

| Most clinicopathological variables significantly different (age, axillary node status, immunohistochemical receptors). Adjuvant RT demonstrated balanced, most co‐interventions missing | Selection may be related to the outcome (those with Mx eventually excluded) | Classification of interventions clear and determined at the start of intervention. Operative details given clearly | All patients received the surgical intervention described in the methods | Analysis unlikely to have removed risk of bias from missing data | Objective outcome measure | No indication of selected reporting | |||

| Borm 2019 | S‐BCS | Serious | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Moderate | Serious |

| Most clinicopathological variables significantly different: age, tumour size, tumour grade, axillary node status, immunohistochemical receptors (ER status). Important co‐interventions (adjuvant CT, adjuvant ET) not balanced across intervention group and may affect the outcome | All participants eligible included | Classification of interventions clear and determined at the start of intervention. Operative details given clearly | All patients received the surgical intervention described in the methods | Analysis unlikely to have removed risk of bias from missing data | Objective outcome measure | No indication of selected reporting | |||

| Carter 2016 | S‐BCS | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Moderate |

| Most clinicopathological variables significantly different (age, BMI, tumour size, stage, axillary node status, immunohistochemical receptors (ER, PR, multifocality). Adjusted for in LR calculation. Important co‐interventions not balanced across intervention group and may affect the outcome (neoadjuvant CT (all), adjuvant RT (Mx/Mx+R), adjuvant CT) | All participants eligible included | Classification of interventions clear and determined at the start of intervention. Operative details given clearly | All patients received the surgical intervention described in the methods | Most patients followed up | Objective outcome measure | No indication of selected reporting | |||

| Cassi 2016 | S‐BCS | Serious | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Serious |

| Some clinicopathological variables demonstrated balance (age, BMI, tumour size), most missing. Important co‐interventions balanced across intervention group (adjuvant RT) some information missing | All participants eligible included | Classification of interventions clear and determined at the start of intervention. Operative details given clearly | All patients received the surgical intervention described in the methods | Most patients followed up | Objective outcome measure | No indication of selected reporting | |||

| Chakravorty 2012 | S‐BCS | Serious | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Serious |

| Some clinicopathological variables demonstrated balance (age, axillary node status) and some different (histological type, tumour size, grade, sample weight), most missing. Important co‐interventions balanced across intervention group (adjuvant RT, adjuvant CT) | All participants eligible included | Classification of interventions clear and determined at the start of intervention. Operative details given clearly | All patients received the surgical intervention described in the methods | Most patients followed up | Objective outcome measure | No indication of selected reporting | |||

| Chauhan 2016 (1) | S‐BCS | Serious | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Serious |

| Some clinicopathological variables demonstrated balance (histological type, grade, axillary node status, immunohistochemical receptors) and some different (age, tumour size, tumour location), most missing Important co‐interventions predefined and uniform across studies | All participants eligible included | Classification of interventions clear and determined at the start of intervention. Operative details given clearly | All patients received the surgical intervention described in the methods | Most patients followed up | Objective outcome measure | No indication of selected reporting | |||

| Chauhan 2016 (2) | S‐BCS | Serious | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Serious |

| Axillary node status demonstrated balance and some clinicopathological variables different (age, tumour size, tumour location), most missing. Important co‐interventions predefined and uniform across studies | All participants eligible included | Classification of interventions clear and determined at the start of intervention. Operative details given clearly | All patients received the surgical intervention described in the methods | Most patients followed up | Objective outcome measure | No indication of selected reporting | |||

| DeLorenzi 2016 (1) | S‐BCS | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Moderate |

| Important clinicopathological factors demonstrated balance (menopausal, histological type, grade, axillary node status, immunohistochemical receptors, lymphovascular invasion) or matched (age (within 5 years), year of surgery (within 2 years), tumour size. Important co‐interventions balanced across intervention group (adjuvant CT, adjuvant RT, adjuvant ET) | All participants eligible included | Classification of interventions clear and determined at the start of intervention | All patients received the surgical intervention described in the methods | Most patients followed up | Objective outcome measure ‐ due to margin status | No indication of selected reporting | |||

| DeLorenzi 2018 | S‐BCS | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Moderate |

| Important clinicopathological factors demonstrated balance (age, BMI, tumour size, immunohistochemical receptors, multifocality), some significantly different (menopausal, grade) Some co‐interventions balanced across intervention group (adjuvant RT, any adjuvant therapy) | Selection may be related to the outcome (Mx eventually excluded) | Classification of interventions clear and determined at the start of intervention | All patients received the surgical intervention described in the methods | Most patients followed up | Objective outcome measure ‐ due to margin status | No indication of selected reporting | |||

| Down 2013 | S‐BCS | Serious | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Serious |

| Some clinicopathological variables demonstrated balance (age, histological type, grade), tumour size different, some missing adjuvant RT balanced across intervention group, some co‐interventions missing | All patients included. Patients were selected for intervention if cosmetic outcome with control would be bad (selection bias but does not affect this outcome) | Classification of interventions clear and determined at the start of intervention, details of operations described | All patients received the surgical intervention described in the methods | Most patients followed up | Objective outcome measure | No indication of selected reporting | |||

| Fan 2019 | S‐BCS | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Moderate |

| Important clinicopathological factors matched (age, BMI, stage) or demonstrated balance (histological type), some missing Important co‐interventions demonstrated balance (neoadjuvant CT, adjuvant RT, adjuvant CT, adjuvant ET) | All participants eligible included, control selected for | Classification of interventions clear and determined at the start of intervention, operative details given clearly | All patients received the surgical intervention described in the methods | All patients followed up for 30 days and for re‐excisions specifically | Objective outcome measure | No indication of selected reporting | |||

| Gulcelik 2013 | S‐BCS | Moderate | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Low | Moderate | Moderate |

| Important clinicopathological factors demonstrated balance (age, tumour size, immunohistochemical receptor), most missing. Important co‐interventions demonstrated balance (adjuvant CT, adjuvant ET, axillary management, adjuvant RT) | All participants eligible included | Classification of interventions clear and determined at the start of intervention, operative details given clearly | All patients received the surgical intervention described in the methods. Included from the beginning of uptake of intervention | All patients included but some did not have sufficient follow‐up so excluded. Details not given | Objective outcome measure | No indication of selected reporting | |||

| Hashimoto 2019* | S‐BCS | Serious | Low | Low | No information | No information | Low | Moderate | Serious |

| Rate of advanced cases of cancer higher in intervention ‐ | All participants eligible included | Classification of interventions clear and determined at the start of intervention. Some aspects maybe determined retrospectively | ‐ | ‐ | Objective outcome measure | No indication of selected reporting | |||

| Keleman 2019 | S‐BCS | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Moderate | Serious |

| Some variables demonstrated balance (age, smoking status, diabetes, BMI, type of cancer, tumour size, grade, stage, immunohistochemical receptor) some different (preoperative bra size, axillary node status) but unlikely to affect outcome Important co‐intervention of adjuvant RT demonstrated balance, some significantly different (neoadjuvant CT, adjuvant CT, adjuvant ET, axillary management) but less of an impact on outcome | All intervention participants eligible included, random patients selected for control | Classification of interventions clear and determined at the start of intervention | All patients received the surgical intervention described in the methods. Two experienced breast surgeons | Patients missed due to loss to follow‐up and did not respond to outcome, equal numbers in both groups so impact may be similar across groups | Objective outcome measure | No indication of selected reporting | |||

| Lee 2018 | S‐BCS | Serious | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Serious |

| Some variables demonstrated balance (age, BMI), some significantly different (tumour size and stage). No breakdown between control and study groups for data on cancer treatment | All participants eligible included | Classification of interventions clear and determined at the start of intervention | All patients received the surgical intervention described in the methods. Centre with large numbers | Most patients followed up | Objective outcome measure | No indication of selected reporting | |||

| Losken 2009 | S‐BCS | Serious | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Serious |

| Some variables demonstrated balance, some significantly different: age, histological type, stage. Important co‐interventions demonstrated balance, some significantly different: adjuvant CT, axillary surgery | All participants eligible included | Classification of interventions clear and determined at the start of intervention | All patients received the surgical intervention described in the methods. Experienced surgeon | All patients included followed up | Objective outcome measure | No indication of selected reporting | |||

| Malhaire 2015 | S‐BCS | No information | Serious | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Serious |

| ‐ | Selection based on localisation techniques | Classification of interventions clear and determined at the start of intervention | All patients received the surgical intervention described in the methods. All surgeons had training in O‐BCS | All patients included followed up | Objective outcome measure | No indication of selected reporting | |||

| Mansell 2017 | S‐BCS | Serious | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Serious |

| Important clinicopathological factors significantly different: age, histological type, tumour size, grade, axillary node status, immunohistochemical receptor (ER, PR). Important co‐interventions balanced, some significantly different: adjuvant CT, adjuvant ET | All participants eligible included | Classification of interventions clear and determined at the start of intervention | All patients received the surgical intervention described in the methods | All patients included followed up until June 2015 | Objective outcome measure | No indication of selected reporting | |||

| Matrai 2014 | S‐BCS | Serious | Serious | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Moderate | Serious |

| Tumour size significantly different. Some variables demonstrated balance (age, histological type, grade, tumour location, bra size, immunohistochemical receptor, axillary lymph node status). Matching of patients reported but not defined: "the same clinicopathological parameters of 60 traditional breast‐conserving surgeries operated by the same breast surgeon were used". Important co‐interventions including adjuvant RT demonstrated balance. Adjuvant CT significantly different | Unclear why these 60 patients selected (not consecutive, some retrospective and some prospective), controls matched | Classification of interventions clear and determined at the start of intervention | All patients received the surgical intervention described in the methods. Experienced surgeon | Groups followed up for different amounts of time: "The mean follow‐up time was 32.2 months in the BCS group compared to only 8.7 months in the OPS group" | Objective outcome measure | No indication of selected reporting | |||

| Mazouni 2013 | S‐BCS | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Moderate |

| Important clinicopathological factors balance: histological type, tumour size, grade, axillary node status, immunohistochemical receptor (PR). Important co‐interventions predefined and uniform across studies (axillary surgery, neoadjuvant CT, adjuvant RT) | All participants eligible included | Classification of interventions clear and determined at the start of intervention | All patients received the surgical intervention described in the methods | All patients included followed up | Objective outcome measure | No indication of selected reporting | |||

| Niinikoski 2019 (2) | S‐BCS | Serious | Moderate | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Moderate | Serious |

| Important clinicopathological factors significantly different: age, tumour size, grade, axillary node status, immunohistochemical status (ER, TN), multifocality Important co‐intervention demonstrated balance (adjuvant RT), some significantly different (adjuvant CT and ET) | All participants eligible included. Excluded on basis on diagnosis by biopsy/incidental. Excluded those without adjuvant therapy nor axillary surgery. Also excluded if follow‐up < 3 years | Classification of interventions clear and determined at the start of intervention | All patients received the surgical intervention described in methods. | Some loss to follow‐up for local recurrence free survival: 140/611 in intervention group, 249/1189 in control group | Objective outcome measure | No indication of selected reporting | |||

| Piper 2016 | S‐BCS | Serious | Serious | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Serious |

| Some variables demonstrated balance (BMI, histological type), age matched for and stage significantly different Important co‐interventions missing | Patients without negative margins excluded, minimum 2 years follow‐up (O‐BCS done more recently) | Classification of interventions clear and determined at the start of intervention: "All reduction mammoplasties were performed either via an inferior or superior‐medial pedicle approach, with a Wise pattern or vertical skin pattern incision, based on tumour location" | All patients received the surgical intervention described in methods | All patients included followed up | Objective outcome measure | No indication of selected reporting | |||

| Vieira 2016 | S‐BCS | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Moderate |

| Important clinicopathological factors demonstrated balance. Matched for demographic and oncological aspects Important co‐interventions demonstrated balance, missing data on axillary management of cases (97.4% for control group) | All O‐BCS participants eligible included, matched standard breast conserving surgery: "cases were matched to decrease a possible bias selection" | Classification of interventions clear and determined at the start of intervention | All patients received the surgical intervention described in methods | All patients included followed up | Objective outcome measure | No indication of selected reporting | |||

| Carter 2016 | Mx | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Moderate |

| Most clinicopathological variables significantly different (age, BMI, tumour size, stage, axillary node status, immunohistochemical receptors (ER, PR, TN), multifocality). Adjusted for in local recurrence calculation. Important co‐interventions not balanced across intervention group and may affect the outcome (neoadjuvant CT (all), adjuvant RT (Mx/MxR), adjuvant CT) | All participants eligible included | Classification of interventions clear and determined at the start of intervention. Operative details given clearly | All patients received the surgical intervention described in the methods | Most patients followed up | Objective outcome measure | No indication of selected reporting | |||

| Gendy 2003 | Mx | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Serious |

| Important clinicopathological factors balanced (Age, grade, axillary node status), some significantly different (histological type, tumour size), some missing. Important co‐interventions different across intervention group, likely to influence outcome. All those that recurred had had RT | All contactable participants | Classification of interventions clear and determined at the start of intervention, operative details given clearly | All patients received the surgical intervention described in the methods | All patients included followed up | Objective outcome measure | No indication of selected reporting | |||

| Lee 2018 | Mx | Serious | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Serious |

| Some variables demonstrated balance (age, BMI), some significantly different (tumour size and stage). No breakdown between control and study groups for data on cancer treatment | All participants eligible included | Classification of interventions clear and determined at the start of intervention | All patients received the surgical intervention described in the methods | Most patients followed up | Objective outcome measure | No indication of selected reporting | |||

| Nakagomi 2019 | Mx | Serious | Low | Low | Low | Low | Serious | Moderate | Serious |

| Some variables demonstrated balance (histological type, axillary node status, immunohistochemical receptor status), some significantly different (age, tumour size, stage), many missing. Important co‐interventions missing (RT, axillary management), neoadjuvant CT significantly different | All participants eligible included | Classification of interventions clear and determined at the start of intervention: latissimus dorsi mini flap or mastectomy | All patients received the surgical intervention described in methods. | All patients included followed up | Objective outcome measure but details of follow‐up time not given | No indication of selected reporting | |||

| Ren 2014 | Mx | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Moderate |

| Important clinicopathological factors demonstrated balance (histological type and location) or matched (age, tumour size, axillary lymph node status, immunohistochemical receptor, (ER, HER2)). Co‐intervention information missing for control group | All participants eligible included | Classification of interventions clear and determined at the start of intervention | All patients received the surgical intervention described in methods | Most patients included: "The median follow‐up time was 83 months in s‐BCS and 81 months in mastectomy" | Objective outcome measure | No indication of selected reporting | |||

| Carter 2016 | Mx + R | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Moderate |

| Most clinicopathological variables significantly different (age, BMI, tumour size, stage, axillary node status, immunohistochemical receptors (ER, PR, TN), multifocality). Adjusted for in LR calculation. Important co‐interventions not balanced across intervention group and may affect the outcome (neoadjuvant CT (all), adjuvant RT (Mx/MxR), adjuvant CT) | All participants eligible included | Classification of interventions clear and determined at the start of intervention. Operative details given clearly | All patients received the surgical intervention described in the methods | Most patients followed up | Objective outcome measure | No indication of selected reporting | |||

| DeLorenzi 2016 (2) | Mx + R | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Moderate |

| Important clinicopathological factors demonstrated balance (grade, immunohistochemical receptors) or matched (age (within 5 years), year of surgery (within 2 years), number of positive axillary lymph nodes, tumour subtype). Important co‐interventions balanced across intervention group (adjuvant CT, adjuvant ET), adjuvant RT different | All participants eligible included | Classification of interventions clear and determined at the start of intervention | All patients received the surgical intervention described in the methods | Most patients followed up | Objective outcome measure ‐ due to margin status | No indication of selected reporting | |||

| Lee 2018 | Mx + R | Serious | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Serious |

| Some variables demonstrated balance (age, BMI), some significantly different (tumour size and stage). No breakdown between control and study groups for data on cancer treatment | All participants eligible included | Classification of interventions clear and determined at the start of intervention | All patients received the surgical intervention described in the methods | Most patients followed up | Objective outcome measure | No indication of selected reporting | |||

| Mansell 2017 | Mx + R | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Moderate |

| Some clinicopathological significantly different: age, immunohistochemical receptor (ER, PR). Other important clinicopathological factors balance: histological type, tumour size, grade, axillary node status, immunohistochemical receptor (HER2). Important co‐interventions demonstrated balance, adjuvant RT significantly different | All participants eligible included | Classification of interventions clear and determined at the start of intervention | All patients received the surgical intervention described in the methods | All patients included followed up until June 2018 | Objective outcome measure | No indication of selected reporting | |||

| Mustonen 2004 | Mx + R | Serious | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Serious |

| Age demonstrated balance, tumour size significantly different, most missing. Adjuvant CT balanced, adjuvant radiotherapy significantly different, other co‐interventions missing | All participants eligible included | Classification of interventions clear and determined at the start of intervention | All patients received the surgical intervention described in methods. | All patients included followed up | Objective outcome measure | No indication of selected reporting | |||

| Ozmen 2020 | Mx + R | Serious | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Serious |

| Important clinicopathological factors balance, some different (age, menopausal status, BMI, tumour size, grade, axillary node status, immunohistochemical receptor status (ER), multifocality), some missing. Important co‐interventions significantly different (adjuvant RT and axillary management), some missing (neoadjuvant RT + CT, adjuvant CT + ET) | Women chose their operation after being told the potential risks and benefits. Bias in assignment: "Both two procedures were explained to patients, and their choices were recorded." | Classification of interventions clear and determined at the start of intervention | All patients received the surgical intervention described in methods. All interventions done by a single surgeon with more than 30 years of experience in breast surgery. | Most patients included: "Median follow‐up time was 56 (14‐116) months." | Objective outcome measure | No indication of selected reporting |

BMI: body mass index CT: chemotherapy ER: oestrogen receptor ET: endocrine therapy HER2: human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 Mx: mastectomy PR: progesterone receptor R: reconstruction RT: radiotherapy

LR: local recurrence

3. Risk of bias for disease‐free survival.

| Study | Control | Confounding | Selection | Classification of intervention | Deviations from intended intervention | Missing data | Measurement of outcomes | Selection of reported results | Overall |

| Acea‐Nebril 2017 | S‐BCS | Serious | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Low | Moderate | Serious |

| Some clinicopathological variables significantly different (age, menopausal status, tumour size, tumour stage, axillary lymph node status, location of tumour, multifocality). Some co‐interventions balanced (neoadjuvant CT and axillary management), some missing | All participants eligible included | Classification of interventions clear and determined at the start of intervention. Some aspects maybe determined retrospectively | Deviation from intended co‐intervention (adjuvant therapy time), co‐interventions significantly different | All patients followed up | Objective outcome measure | No indication of selected reporting | |||

| Borm 2019 | S‐BCS | Serious | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Moderate | Serious |

| Most clinicopathological variables significantly different: age, tumour size, tumour grade, axillary node status, immunohistochemical receptors (ER status). Important co‐interventions (adjuvant CT, adjuvant ET) not balanced across intervention group and may affect the outcome | All participants eligible included | Classification of interventions clear and determined at the start of intervention. Operative details given clearly | All patients received the surgical intervention described in the methods | Analysis unlikely to have removed risk of bias from missing data | Objective outcome measure | No indication of selected reporting | |||

| DeLorenzi 2016 (1) | S‐BCS | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Moderate |

| Important clinicopathological factors demonstrated balance (menopausal, histological type, grade, axillary node status, immunohistochemical receptors, lymphovascular invasion) or matched (age (within 5 years), year of surgery (within 2 years), tumour size. Important co‐interventions balanced across intervention group (adjuvant CT, adjuvant RT, adjuvant ET) | All participants eligible included | Classification of interventions clear and determined at the start of intervention | All patients received the surgical intervention described in the methods | Most patients followed up | Objective outcome measure ‐ due to margin status | No indication of selected reporting | |||

| DeLorenzi 2018 | S‐BCS | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Moderate |

| Important clinicopathological factors demonstrated balance (age, BMI, tumour size, immunohistochemical receptors, multifocality), some significantly different (menopausal, grade). Some co‐interventions balanced across intervention group (adjuvant RT, any adjuvant therapy) | Selection may be related to the outcome (mastectomy eventually excluded) | Classification of interventions clear and determined at the start of intervention | All patients received the surgical intervention described in the methods | Most patients followed up | Objective outcome measure ‐ due to margin status | No indication of selected reporting | |||

| Gulcelik 2013 | S‐BCS | Moderate | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Low | Moderate | Moderate |