Abstract

The energy market is extremely vulnerable to the uncertainty caused by the pandemic and leads to global lockdowns and stagnant economic activity. This study is important because energy prices (EPs) experience a dramatic decline due to the pandemic, which has negative consequences for the global economy. We aim to analyze EPs behaviour to coronavirus (COVID-19) from 2020:01 to 2021:05. The finding shows that EPs are extremely vulnerable to the uncertainty produced by the pandemic in the short run. The COVID-19 has a negative effect on EPs in the medium to upper quantile, which suggests that higher uncertainty caused by the pandemic results in rapid decline. However, the impact of the COVID-19 is greater on the oil prices (OPs) as compared to the natural gas (NGP) and the heating oil price (HOP). Moreover, the finding reveals that COVID-19 impact on EPs are consistently negative across all the quantile. The degree of the impact increases when the relationship changes from short to long run. The pandemic has affected the energy price in the short run, which needs prudent policies to fully grasp the magnitude of the COVID-19 impact on energy prices.

Keywords: Energy prices, Oil prices, COVID-19, Quantile-on-quantile, Wavelet transforms

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

The main purpose of this paper is to evaluate the impact of coronavirus (COVID-19) on the different energy prices (EPs) such as West Intermediate Texas price (WOP) and Brent oil price (BOP), natural gas (NGP) and heating oil price (HOP). The international energy market and uncertainty have a strong relationship [1], which is manifested in the current pandemic. The world is passing through a difficult phase due to the COVID-19 pandemic, which has a far-reaching impact on every segment of the economy [2,3]. The international Monetary Fund (IMF) predicts that the global economy will shrink by 4.4% in 2020 and shock is more severe than the global financial crisis in 2008 [4,5]. It shows that stagnant economic growth has a negative impact on energy consumption and demand [[6], [7], [8]]. The crisis has battered the global economy, causing the worst recession since the great depression of the 1930s. The economic shock caused by the imposing lockdowns proves costlier than the pandemic itself. Moreover, the pandemic is strangling the global economy, leading to layoffs, a tourism crisis and plunging oil prices (OPs) [9]. It has restricted transportation, air traveling and factories are closed, which results in less oil demand. Moreover, energy consumption declines because of the pandemic.

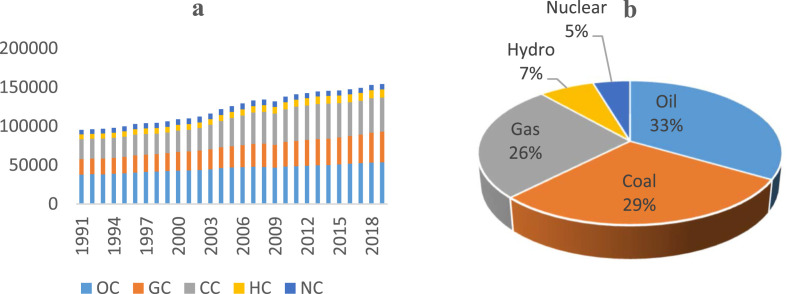

Fig. 1 shows the global energy consumption by source and the share of energy source in total. It explores that global energy consumption has increased rapidly in the last three decades, driven by robust economic growth [10,11]. The consumption of coal, oil and gas has been rising over the years (Fig. 1a) mainly caused by China, India and the Middle East. Similarly, Fig. 1b exhibits global energy sources which are mainly comprising fossil fuels of about 88% of the total energy. This rising demand has increased energy security and diversifying energy sources has become the important priority of the energy policy [12,13]. The energy consumption will increase for sustainable economic growth, which can be vulnerable to political and economic events [14,15].

Fig. 1.

Global energy sources consumption. b. share of energy sources in total. Note: OC denotes oil consumption; GC indicates gas consumption; CC represents coal consumption; HC expresses hydro consumption and NC denotes nuclear consumption.

The uncertainty caused by the pandemic has led to global lockdowns, travel restrictions, stagnant economic growth and the declaration of a state of emergency by the World Health Organization (WHO), which is extremely detrimental to EPs [[16], [17], [18], [19]]. There is a high level of uncertainty in wake of the COVID-19, which has disturbed EPs dynamics and investors sentiments [4,20,21]. The mobility constraints lead to demand drop and a huge decline in EPs because the aviation and transport sectors account for 60% of oil demand [2,22]. The international energy market is in the doldrums in the pre-pandemic period as a result of the feud between the major oil producers. This price has resulted in the oversupply in the market, which reflects in the low OPs [7]. The leading oil producer countries supply more oil than ever, leading to a collapse in price. However, the situation becomes worse with the breakout of the pandemic and leads 50% fall in EPs in March 2020. OPs have witnessed a historical fall and turn into negative and demand declines dramatically. EPs experience a rapid decline in April 2020 and first time in history oil futures falls negative [23]. Meanwhile, the major producing countries agree to cut oil production which couldn't control EPs fall. The international energy market has shown a moderate recovery as a result of countries emerge from the lockdown and OPEC agree to a production cut. However, a new wave of COVID-19 in August 2020 may cause OP to remain low for a long time, as longer global movement restrictions have led to a decline in the demand for fuel. Prices have shown a downward trend in September 2020 because of concerns about the recurrence of the pandemic. Similarly, the energy market saw its biggest decline since March in November 2020, as new and stricter lockdown measures may threaten an unstable demand recovery. Meanwhile, the successful vaccine trial and economic recovery of the major economies are positive indicators for the energy market. The demand increase and OPs rise to $60 a barrel. Moreover, NGP is negatively affected by the COVID-19 as demand declines in the short run [24]. NGP rise in February 2021, because the world is opening up, the economy is growing again, and prices rise accordingly [[25], [26], [27]]. It is normal for prices to rise after the recession, and NGP returns to pre-pandemic levels.

This study has several contributions to the existing literature. First, it explains that EPs collapse as a result of the COVID-19. EPs experience a dramatic decline during the pandemic, which has negative consequences for the global economy. This study offers a macro relationship and prompt effect across different quantiles. The results show that COVID-19 has influenced the EPs in the lower to upper quantile. However, the relationship becomes more regular in the decomposed series and shows a negative impact in the short run. Last, the study enriches the existing literature by introducing the novel approach, which is the combination of the QQ approach and wavelet transform. This is the first study to evaluate the COVID-19 impact on energy prices by employing the quantile on quantile (QQ) method. The finding provides useful input to the future policy for both the oil-exporting and importing countries. The procedure is useful to examine the nonlinear relationship of variables in the different quantiles. Thus, we analyze the impact of the COVID-19 on EPs. The finding shows that EPs are extremely vulnerable to the uncertainty produced by the pandemic in the short run. The COVID-19 has a negative effect on EPs in the medium to upper quantile, which suggests that higher uncertainty caused by the pandemic results in rapid decline. The energy demand collapses because of the traveling restriction, lockdown and contraction of the economic activity. Moreover, the finding reveals that COVID-19 impact on EPs is consistently negative across all the quantile. The degree of the impact increase when the relationship changes from short to long run.

Section 2 of this paper reviews the previous literature, which follows the methodology in section 3. Whereas the data is explained in section 4, which is followed by an empirical analysis in section 5. The conclusion of this study is highlighted in section 6.

2. Literature review

Nyga-Łukaszewska and Aruga [2] analyze the COVID-19 impact on oil and gas market. They find pandemic has severely hit the global energy market. It shows that COVID-19 has a negative effect on OP in the U.S. and Japan, while a positive impact on gas prices. Aruga et al. [28] examine the COVID-19 impact on energy consumption in India. The outcomes reveal that energy consumption declines dramatically during the lockdown. However, it recovers as the lockdown is relaxed. Mensi et al. [4] assess the upward and downward trends of COVID-19 on OP. The results express strong evidence of the pandemic impact on the oil price. The effect on the oil price is more strong in the downside trend, while the price is more inefficient in the pre-COVID-19 period. Aloui et al. [29] find that EPs are extremely vulnerable to the pandemic and have a negative impact on it. Likewise, speculation in the future market increases with the rise in the number of deaths. Yilmazkuday [30] finds the COVID-19 daily deaths on OP. It concludes that pandemic has no impact on the oil price drop, but the collapse of prices is caused by the disagreement between OPEC. Maijama'a et al. [31] examine the COVID-19 impact on global energy demand. The results show pandemic has a negative influence on the OP. Sharif et al. [32] evaluate the nexus between COVID-19, OP and geopolitical risk in the U.S. The outcome shows strong connections between the COVID-19 and OP, which are reflected in the rising economic uncertainty and geopolitical risk. Amadi et al. [33] find that pandemic has disrupted the global supply chain and travel restrictions which have translated into OP falls. Mzoughi et al. [20] find that the COVID-19 pandemic leads to a reduction in the oil demand and price collapse to negative. However, the negative response of the oil market is brief and recovers in the short run. Kingsly and Henri [34] show that OP plummets as the pandemic intensifies in Europe and North America. The oil demand will decline in the major importers countries as the industrial production may slow down.

Novan et al. [16] report that energy sectors have reacted quickly to the COVID-19. The strict lockdown has slammed the airline and transport industry which is reflected in the low demand for energy and low prices. Gao et al. [26] analyze the COVID-19 effects on the financial markets in the U.S. and China. The finding suggests that pandemic leads to a drastic decline in March 2020, which has increased uncertainty around the globe. Khan et al. [35] find dramatic OP declines as a result of the falling demand. Jiang et al. [36] explore that COVID-19 has caused great challenges to the global energy system. It has declined the energy demand and consumption and highlights the energy-related emerging opportunities for the energy sector in post pandemics. Norouzi et al. [37] show that COVID-19 has changed the energy market behaviour in Spain and declines energy consumption. Shaikh [38] unveils the COVID-19 impact on the energy market and suggest that WOP has shown extraordinary volatility during the pandemic. The uncertainty has a noticeable impact on the historical volatility of the energy market. Qin et al. [18,19] evaluate the relationship between oil prices and COVID-19 and conclude that pandemic has declined the oil demand and collapse oil prices. Devpura and Narayan [39] show that the COVID-19 drive the hourly OP volatility. Algamdi et al. [40] investigate the COVID-19 effects on OP in Saudi Arabia and the finding suggests that rising death number has a considerable impact on OP. Shahzad et al. [41] study the influence of COVID-19 on WOP and find that the variance of WOP is at the highest level during the pandemic outbreak and has adversely affected OP. Tang et al. [42] evaluate the role of COVID-19 on the relationship between the international and Chinese fossil fuels markets. The outcome reveals that COVID-19 does not influence the association between the Chinese and international fossil fuels market. However, the results show that the Chinese fossil fuels market are driven by the COVID-19. The preceding literature mostly covers the oil market and its behaviour during the pandemic. The two important oil prices WOP and BOP are discussed and concludes that the pandemic has squeezed the global economic activity which is reflected in falling oil demand. Meanwhile, oil prices witnesses historically low prices and WOP collapses to a negative level. However, there are different energy sources such as natural gas and heating oil prices which has been severely affected by the pandemic. Thus, the existing literature lacks sufficient studies about the entire energy market. Moreover, in terms of methodology, most of the studies present qualitative scenarios which may be unable to grasp the actual situation and to devise the relevant policy implications. Similarly, the period may be short for analysis because of the evolving situation of the crisis. Thus, the current study fills the gap to enhance the literature by examining the different EPs response to the uncertainty caused by the pandemic. The study covers a more extensive period and emphasizes quantitative analysis.

3. Methodology

3.1. Wavelet analysis

The application of wavelet analysis in economics is common [43,44]. It is like a wave oscillation starting at zero and altering and reverse back to zero [45]. We employ a wavelet with different frequencies to fit the time series in both the time and frequency domain [[46], [47], [48]]. We can construct dyadically the wavelet and converted a pair of particularly constructed function and such that:

| (1) |

| (2) |

where and denote the father wavelet and mother wavelet, respectively. The former detects the smooth and low-frequency components of the variable and later detect the comprehensive and high-frequency components of the variable. Thus, the achieved wavelet is illustrated as follow based on the above equations.

| (3) |

| (4) |

The number of observations restricts the maximum number of scales that the scrutiny can measure (T≥).

A special attribute of the wavelet expansion is the coefficient of the positioning attribute which signifies the information content of the function at the estimated position and frequency . Thus, the can be expanded underlying wavelet at the arbitrary level over different scales.

| (5) |

where. denotes a scaling function and scale coefficients, where the corresponding coarse scale coefficients and denote the comprehensive coefficients specified by and , respectively. The series (t) offers a smooth form of the original series (t), which detects the long run (i.e., low-frequency) features, whereas the series (t) notice local variations (i.e., the higher-frequency features) of (t).

3.2. Maximum overlap discrete wavelet transform

The wavelet transform is performed of the discrete sampled by Discrete wavelet transform (DWT). It is based on the scaling filter ( l, l = 0, … …. L−.) and the wavelet filter (. L∈ℕ denotes the length of the filter [49]. The wavelet filter fulfils these three characteristics.

| (6) |

The low- and high-pass filters are defined as quadrature mirror filters, which

| (7) |

Similarly, the scaling filter fulfils the conditions.

| (8) |

The wavelet and scaling coefficients of DWT at the pth level for p∈{1, …, p} are defined as:

| (9) |

The maximal overlap discrete wavelet transform (MODWT) suggested by Percival and Walden [49] decomposes the series. This method is useful in solving the DWT limitations. Daubechies least asymmetric, as well as the scaling coefficients, achieves the wavelet as it has high power to detect time-scale deviation in a series.

We decompose the main data series into a different frequency band and a set of wavelet coefficients. The rescaled scaling is achieved by incorporating the MODWT as follows;

| (10) |

As recommended by Mallat [50]; and are achieved by using the pyramid algorithm. It requires three inputs for each iteration of the MODWT algorithm. The first starts by faltering data and gives the listed wavelet and scaling coefficients

| (11) |

The scaling coefficients of the first step develop as input data vectors and are used to achieve the second step. We illustrate the second level wavelet as follows;

| (12) |

Likewise, the pth level MODWT wavelet and scaling coefficients of the time series Xt are expressed as:

| (13) |

3.3. The quantile-on-quantile method

The discrete wavelet transform (DWT) has drawbacks of the dyadic length restriction for the series to be transformed and that it is non-shift invariant. Thus, the MODWT is introduced to overcome the weaknesses of DWT by giving up its orthogonality and gaining the ability to handle any sample size regardless of whether the series is dyadic or not [51]. The MODWT has the advantage that it is capable of managing a multivariate analysis [52]. Moreover, the disadvantage of the quantile regression is the lack of power capture dependence in the entirety [53]. It overlooks the possibility of the nature (i.e., low, normal, or high levels) of COVID-19 also could influence the way EPs is predicted. The quantile regression does not consider the nature of large and small changes that impact the association [26]. The asymmetric relationship, such as the positive shock of one variable may have a different influence on the other as compared to the negative shock which is not assessed. Thus, the QQ method is applied to detect the dependence in its entirety so that correlation between variables could vary at each point of their respective distributions. Similarly, the QQ method offers a complete picture of dependence [53]. It can reveal the effects of shocks at varying degrees and heterogonous tail dependence structure. The QQ approach has the advantage of flexibility, which normally detects the functional form of the dependency nexus between variables.

We briefly explain the characteristic of the QQ method proposed by Sim and Zhou [54] and specify the model to investigate the COVID-19 impact on the energy price. The QQ method is used to detect the impact of the pandemic on EPs. Moreover, it is used to assess the dependency pattern of EPs on COVID-19. The approach is the aggregate of quantile regression and nonparametric estimation of local linear regression [55]. Therefore, we use the QQ approach to examine the impact of the quantiles of COVID-19 on the quantiles of the various energy prices such as WOP, BOP, NGP and HOP.

The procedure begins with the nonparametric quantile regression model.

| (14) |

We examine the association between the ϑth quantile in the background of COVIDτ by using local linear regression. As is unidentified, this function can be estimated by a first-order Taylor expansion about the quantile COVIDτ.

| (15) |

where show the partial derivative of in the context of COVID. The outcome is termed the marginal effect which can be construed like the slope coefficient in the linear regression model.

The parameters and are the conspicuous aspect of Equation (15) which are doubly indexed in and τ. Assumed that and are both functions of and , and that is a function of τ, it is clear that both and are functions of θ and τ. Furthermore, and can be retitled as and respectively. Therefore, Equation (15) can be rephrased as:

| (16) |

By replacing equation (14), (16) we get (17)

| (17) |

where EP represents the energy price of WOP, BOP, NGP and HOP. The part (∗) of Equation (17) is the th conditional quantile of COVID. However, unlike the function of the standard conditional quantile, this manifestation replicates the association between the th quantile of COVID and the τth quantile of EP because the parameters and , are doubly indexed in and τ. Likewise, a linear relation is not supposed at any time between the quantiles of the studied variables.

Estimating Equation (17) requires replacing and with their estimated counterparts and , respectively. The local linear regression estimates of the parameters and , which are estimates of and , respectively, are obtained by solving the following minimization problem:

| (18) |

where is the quantile loss function, defined as and I indicates the usual indicator function. K (∙) represents the Gaussian kernel function and ℎ represents the bandwidth parameter of the kernel. It determines the size of the neighbourhood about the target point and explores the smoothness of the resulting estimates. Hence, the selection of the bandwidth is more important in the nonparametric estimation method. The estimation can cause biased results when the large bandwidth is selected and a higher variance with smaller bandwidth. Thus, the appropriate bandwidth selection is very important to provide a balance between the bias and the variance [56]. The constant bandwidth is not appropriate for every situation and may results in biases in estimation [55]. This study employs bandwidth parameter ℎ = 0.05 for the estimation based on Sim and Zhou [54] methodological method.

Fig. 2 illustrates the research chart flow which shows the sequence of the study. The flow chart illustrates that introduction explains the global energy consumption trends, the objective of the study, and emphasized the main contribution. The literature review summarizes the previous studies about energy prices and COVID-19 and highlights the drawbacks of the previous studies and enumerates the advantages of the present paper. The QQ method is used data to analyze the impact of COVID-19 on EPs in the different quantiles which confirms that COVID-19 has a consistently negative impact on EPs. Moreover, the study has a significant contribution to the policymakers.

Fig. 2.

Research flow chart.

4. Data

4.1. Data description

We investigate the COVID-19 effect on the various EPs. The daily new cases of the COVID-19 are retrieved from the WHO and the spot prices of EPs are obtained from the U.S. Energy Information Administration. The series are converted to a natural logarithmic form. The starting point of this study is extremely important because of China; one of the leading energy consumers of the world has experienced a chaotic situation because of COVID-19. It has resorted to the complete lockdown on January 23rd, 2020, to control the virus spread. This has created a fear of a potential pandemic in the world, which has slammed the economy and EPs. Furthermore, the WHO declares the COVID-19 an emergency on 30th January 2020, which increases the uncertainty and has the greatest impact on EPs [16].

We decompose the regression series into short, medium and long-term trends. The short-run reveals COVID-19 impact on EPs in the short-term horizon (between 1 and 16 days). The medium-term horizon measures the variation between 32 and 64 days. Similarly, the COVID-19 impact on EPs in the long-term horizon from 128 to 256 days. Table 1 highlights the summary of the variable series. In the energy series, BOP has the highest mean values. However, WOP has the highest standard deviation, which implies its greater global usage and exposure to any uncertainty. This is evident in the pandemic that WOP declines more quickly to a negative level for the first time in history. The skewness values show that the series skewed to left, suggesting greater volatility. However, the kurtosis values of WOP, BOP, NGP and HOP are less than 3, which is platykurtic distribution. We label the leptokurtic distribution COVID-19 because its value is greater than 3. Last, the non-normally distribution is confirmed WOP, BOP and HOP by the Jarque-Bera test. In the case of the COVID-19 and NGP, the series are normally distributed.

Table 1.

Summary statistics.

| Mean | Std. Dev | Skewness | kurtosis | J-B | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COVID-19 | 11.923 | 2.089 | −0.610 | 3.145 | 4.278 |

| WOP | 3.371 | 1.090 | −5.871 | 43.503 | 5038.865∗∗∗ |

| BOP | 3.537 | 0.518 | −0.408 | 1.859 | 5.571∗∗∗ |

| NGP | 0.600 | 0.065 | −0.626 | 2.988 | 4.452 |

| HOP | 0.212 | 0.270 | −0.334 | 1.905 | 4.664∗∗∗ |

Note: ∗∗∗ denote significance level at 1%.

We explain the correlation coefficients between COVID-19 and EPs in Table 2 . The outcome illustrates that COVID-19 and EPs are highly positively correlated for all the energy sources. Furthermore, the highest correlation coefficient is recorded for the NGP, followed by BOP and WOP. The correlations are highly significant, evident from the p-values which are statistically significant at 1% level.

Table 2.

Correlation results of COVID-19 and EPs.

| COVID-19 | Correlation | t-value | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| WOP | 0.224 | 4.164∗∗∗ | 0.000 |

| BOP | 0.295 | 5.591∗∗∗ | 0.000 |

| NGP | 0.4.84 | 9.889∗∗∗ | 0.000 |

| HOP | 0.134 | 2.457∗∗∗ | 0.000 |

Note: ∗∗∗ denotes the significance level at 1%.

4.2. Data behaviour

The energy market is facing challenges because of the price war between Russia and Saudi Arabia, which maybe further serious by the pandemic. From February to March 2020, the energy market has witnessed increasing oil supply mainly driven by the price rivalry between Russia and Saudi Arabia. Similarly, the U.S. oil supply hit a record level per day due to heavy borrowing by the U.S. companies. However, the oversupply is overshadowed by the COVID-19 and OPs have fallen by more than half in late March 2020. Moreover, the U.S. oil production falls in April 2020. The oil supply is rising, refineries and storage are brimming because the pandemic coincides with surging oil production. Crude oil is traded on futures contracts and fears of no storage may lead to a severe drop in WOP from $18 a barrel to around -$37 a barrel. Similarly, oil witnesses a severe drop to its lowest in 18 years at the global level and the demand has declined by nearly more than half since mid-March 2020 because of lockdown and traveling restrictions to contain the virus spread. The major producing countries such as Saudi Arabia and Russia keep pumping throughout March and have cut down in April by 10 million barrels per day. The production cut is not matched with the decrease in demand and EPs continue to decline. The gradual reopening of the various economies sustains the market sentiment, which causes EPs to recover to a moderate level. The prices recover as countries emerge from the lockdown and OPEC agree to a production cut. However, a fresh wave of the COVID-19 case could cause prolonged low crude OP as demand for fuel is plunging from longer movement restrictions globally. BOP declines in August 2020 because of a fresh wave of COVID-19 and new lockdowns may restrain demand. Meanwhile, the total global cases have crossed 20 million and record deaths in the U.S. which shows a weaker energy demand. The price shows a declining trend in September 2020 due to concern over the resurgence of pandemics and the expectation of oversupply. However, BOP and WOP remain at an average of $41.80 and $40.05, respectively. Likewise, the energy market has posted the largest decline in November 2020 since March as new tougher lockdown measures to control pandemic which can threaten demand recovery.

Meanwhile, the improvement in China and India, booming freight market is supportive of the energy demand revival. Similarly, the U.S. presidential election and the OPEC + meeting in November have a significant impact on the price and future outlook. The OPEC face challenges to keep the supply in control as Libya and Iraq are expected to return output. However, Iraq affirms to support the OPEC + production cuts, Norway will supply to the pre-COVID-19 level. The vaccine trial in November 2020, which is very successful and the market looks for a brighter future with a victory over the pandemic. The dramatic improvement in sentiment as a result of the oil market fundamentals and supported by the financial market. Furthermore, the WHO data shows that COVID-19 is declining, which is a positive indication for the oil market and the expectation of demand is rising. The oil demand has surged by 50% since October but recovery still facing obstacles in global fuel demand. BOP surges since January and WOP reach $60 a barrel because of rising demand and reopening of economies. During the period, NGP is suppressed by the COVID-19 as demand declines. The impact is more evident in the short run, mainly caused by the pandemic and the mild winter seasons. Moreover, the gas industry in the crisis in the pre-COVID-19 period which is furthered by the emergence of the pandemic [26,57]. A price hike is witnessed in the gas in February 2021 because the world is opening up and the economy is again on the rise and prices are rising along with it. The rising prices are normal after the recession and the gas prices are going back to the level before the pandemic.

5. Empirical results

We exhibit the QQ results of the original and decomposed series in Fig. 3 . The τth quantile of COVID-19 applies on the ϑth quantile of WOP is detected by the values in the z-axis. The outcome of the original data shows in Fig. 3 (A) that daily cases have a significant negative impact on WOP and the impact is observed in the upper quantile (0.90–0.90). The highest impact (−0.047) is observed in the upper quantile which reveals that pandemic at the upper quantile leads to higher declines in WOP. As WOP are the U.S. oil price benchmark, that has witnessed excessive supply from the producer in the pre-pandemic period and the energy market is further damaged by the COVID-19. The results are similar to Gao et al. [26] which explains the pandemic influence the two major countries, China and the U.S. and conclude that COVID-19 has a severe impact on the energy market in these countries.

Fig. 3.

QQ estimates of slope coefficient. Impact of COVID-19 on WOP. Note: graph demonstrates quantiles of COVID-19 in the x-axis and the quantiles of EPs in the y-axis.

We highlight the decomposed data outcomes in Fig. 3 (B-D). It shows that the COVID-19 influence the WOP negatively in the short run in the medium to upper quantile (0.55–0.75). The highest impact of the pandemic on WOP (−0.008) is witnessed, which reveals that uncertainty caused by the COVID-19 leads to a rapid decline in WOP in the short run. WOP declines rapidly when the pandemic breakout. The supply has increased by the U.S. producer even as prices fall and production reaches the highest level of 13.1 million barrels per day in February 2020. The U.S. companies are reluctant to slow down because of heavy borrowing. Henceforth, the daily case has affected WOP in the upper quantile (0.70–0.80) in the medium term. Similarly, the impact of COVID-19 on WOP is negative in the short run. It shows the greatest effect (−0.013) of COVID-19 on WOP in the medium period in the upper quantiles. It shows that price falls by more than a half in late March 2020 and oil production in the U.S. declines in April. The negative effect is detected in the long run in the medium to upper quantile (0.55–0.85). The coefficient (−0.933) indicates that as the crisis getting worse, the pandemic lockdown has resulted in the decline of oil demand and WOP turn negative for the first time in history.

The QQ technique decomposes the estimates of quantile regression which allowing particular estimates to be achieved for various quantiles of the explanatory variable. In this study, the quantile regression is based on the θth quantile of CVID-19 on EPs. The parameters of COVID-19 and EPs are indexed by θ and τ. Furthermore, the QQ process comprises more disaggregated material about the COVID-19 and EPs nexus than the quantile regression. The QQ approach is heterogeneous across different quantiles. In this regard, the QQ approach is used because of the decomposition characteristics to recover the estimates from the standard quantile regression. Thus, the parameters of quantile regression are indexed by , which is estimated by averaging the QQ parameters along τ. The slope coefficient measures the impact of COVID-19 on EPs and is represented by and estimated as follows:

| (19) |

where s is quantile numbers τ = [0.10,0.15, …..0.90].

Fig. 4(a–d) illustrates the validity results by QQ estimates and quantile regression. The outcome reveals that the effect of COVID-19 on WOP is consistently negative across all quantiles. However, the effect of COVID-19 on WOP is detected in the upper quantile, which suggests that higher uncertainty caused by the pandemic results in rapid decline. It concludes that WOP is less responsive to COVID-19 at the start, while the lockdown and traveling restriction leads to a rapid decline in oil demand, which is readily reflected in WOP.

Fig. 4.

Quantile Regression and QQ estimates. Note: quantile regression is denoted by the black line and QQ estimates are represented by the red line.

We display the QQ results of the original series in Fig. 5 (E) . The COVID-19 has a negative effect on BOP in the upper quantile (0.80–0.90). The greatest impact (−0.034) is detected in the upper quantile, suggesting the greater decline in BOP caused by the pandemic. At the start of the pandemic, the major producing countries agree to cut production and stabilize the price. However, the market moves in the opposite direction and price declines massively. Likewise, the new agreement of production cut between Saudi Arabia and Russia could not materialize and price war may increase the production.

Fig. 5.

QQ estimates of slope coefficient. Impact of COVID-19 on BOP.

The decomposed data results are illustrated in Fig. 5 (B–H). It shows that COVID-19 has affected BOP negatively in the upper (0.70–0.80) in the short term. This reveals the highest impact (−0.421) of COVID-19 on BOP, which implies that the pandemic has an extremely detrimental effect on BOP in the short run. The global demand for crude oil declines by a third in early March 2020 because of strict lockdown and travel restrictions. The supply continues to increase, refineries and storage tanks are brimming because the pandemic coincides with surging production around the world. The price war between Russia and Saudi Arabia results in the oversupply of oil, which has worsened the OP [58]. Similarly, the demand has declined by nearly half since mid-March 2020 and consumption plunges by 70%. This is a global phenomenon and billions of people remain under strict lockdown and social distancing to slow the spread of the virus. Similarly, the COVID-19 has a negative impact on BOP in the lower to medium quantile in the medium term (0.40–0.70), with a coefficient (−0.059). A moderate recovery is witnessed in the medium term which has boosted the oil demand. The price recovers as some economies relax the restriction due to vaccine arrival and natural decline which increase the oil demand. Moreover, the OPEC and non-OPEC increase the supply to recover their production cut and to regain shares in the market. However, the results suggest that pandemics influence BOP in the upper quantile (0.60–0.85) in the long run. It shows the greatest impact (−0.816) of COVID-19 on BOP in the upper quantile which demonstrates that higher pandemic uncertainty leads to a greater decline in BOP. However, BOP declines again due to the second wave in August 2020 in the long run.

The average QQ regression outcomes express the impact of different measurements and are described in Fig. 6 (e–h). It demonstrates that the impact of COVID-19 on BOP is consistently negative across all the quantiles. The finding endorses that the extent of the impact is more causative in the short and long run. It is explained that when the pandemic has started; BOP falls faster, and in the medium term, because of the partial recovery of the economy, oil demand increased and prices stabilized. However, in the long run, BOP declines again as a result of the second wave of the pandemic, which increases the uncertainty and has a negative effect on BOP.

Fig. 6.

Quantile Regression and QQ estimates.

The QQ impact of COVID-19 on NGP is highlighted in Fig. 7 (I) . The finding reveals that the negative effect of COVID-19 on NGP in the lower to upper quantile (0.40–0.95). The greater effect of the pandemic on NGP is (−0.002) in the lower-upper quantile, which means that the moderate uncertainty caused by the pandemic is followed by an extreme decline in NGP. The pandemic has a profound impact on NGP and predicted that demand may decline by 4% in 2020 [24], which is heightened by the COVID1-19 [26]. However, the gas sectors are in crisis before COVID-19, characterized by short-run oversupply, low prices and record level investment in the future supply. The situation gets worse because of COVID-19 as the demand collapse in the short run. Thus, the pandemic is causing a decline in the demand for natural gas because of economic contraction, which is hitting all energy resources. Similarly, the structural transformation takes place where the industry transitioned from the long and rigid contracts to a system where real-time information is reflected in the price. The gas industry experiences a geopolitical transformation shaped by the rise of major players-the U.S. Russia, Qatar and China, which affect the global gas market.

Fig. 7.

QQ estimates of slope coefficient. Impact of COVID-19 on NGP.

Fig. 7 (J-K) illustrates the wavelet decomposed data result of NGP. The outcome of suggests that COVID1-19 has a negative impact on the NGP in the short run in the lower to upper quantile (0.60–0.80). The extent of the impact is strong, as evident by the coefficient (−0.231), which infers that pandemic is extremely harmful to NGP in the short run. This may be because in the early stages of the pandemic, fears are very high, and most countries adopted strict lockdowns and travel restrictions, which is reflected in the decline in energy demand. Similarly, COVID-19 has negatively impacted NGP in the medium to upper quantiles (050–0.80) and coefficient (−0.006) indicates the size of impact in the midterm. In the long run, COVID-19 has the highest impact (0.580) on NGP in the lower to upper quantile (0.20–0.90). It reveals that pandemic has a positive effect on NGP in the long and the price increase in February 2021 because the world is opening and the economic activity is on the rise. The rising prices are normal after the recession and NGP are going back to the level before the pandemic.

The validity of the results are examined by comparing QQ and QQ regression, which is stated in Fig. 8 (i–l). It demonstrates that the impact of COVID-19 on NGP is negative except in the long run. The size of the impact is strong in short, which is evident that sudden break out of the pandemic results in the rapid decline in NGP, which follows a recovery in the long run.

Fig. 8.

Quantile Regression and QQ estimates.

The COVID-19 impact on HOP is shown in Fig. 9 (P) . It exhibits that COVID-19 has a negative impact on HOP in the lower to upper quantile (0.25–0.85), with the highest impact of (−0.010). It implies that there is a huge uncertainty at the beginning of the pandemic, severe lockdown and global traveling restriction collapse the energy demand. Thus, HOP has observed a declining trend and reaches the lowest level in May 2020. The wavelet decomposed results are exhibited in Fig. 9 (Q-S). It shows the negative impact of COVID-19 on HOP in the upper quantiles (0.75–0.85) in the short run. The coefficient (−0.146) recommends the highest negative impact of the pandemic on HOP. Similarly, the COVID-19 has a negative impact on HOP in the lower to upper quantile (0.30–0.80) in the midterm. The size of the impact is shown by the coefficient (−0.305), which suggests that the economic activity is contracted and energy demand witnesses the lowest trend, which results in the collapse of the energy price to a negative level. The price starts to rebound in June 2020 and obtain the pre-COVID-19 level in February 2021. Last, the COVID-19 has a negative effect on HOP in the upper to lower quantile (0.90–0.20) in the long run. Furthermore, the extent of effect (−0.148) is strong and indicates that the pandemic has squeezed the energy demand and HOP has been adversely affected. This is evident in the last quarter of 2020 that HOP witness an increasing trend in response to the demand.

Fig. 9.

QQ estimates of slope coefficient. Impact of COVID-19 on HOP.

However, the average QQ regression results show the influence of parameters of the COVID-19 in Fig. 10 (p–s). The outcome confirms that COVID-19 impact on HOP is consistently negative across all the quantiles. The level of influence increases as the relationship changes from short to medium and long run.

Fig. 10.

Quantile Regression and QQ estimates.

6. Conclusion

We examine the COVID-19 impact on EPs by using the QQ method. The finding shows that EPs are extremely vulnerable to the uncertainty produced by the pandemic in the short run. The COVID-19 has a negative effect on EPs in the medium to upper quantile, which suggests that higher uncertainty caused by the pandemic results in rapid decline. The energy demand collapses because of the traveling restriction, lockdown and contraction of the economic activity. However, the impact of the COVID-19 is greater on OPs as compared to NGP and HOP. Moreover, the finding reveals that COVID-19 impact on EPs is consistently negative across all the quantile. The degree of the impact increase when the relationship changes from short to long run. The study offers some useful policy implications for the relevant. First, the results indicate that pandemic has greatly impacted the energy price in the short run. Thus, prudent policies are required to fully grasp the magnitude of the COVID-19 impact on energy prices. Our finding may help to describe the extent of pandemic impact and devising future policies. Similarly, the supply side can be managing by the concerned governments to support the national oil companies. Second, the result suggests that the energy market experience a crisis before the COVD-19 emergence which is aggravated by the pandemic. Therefore, to mitigate the expected similar future crisis and its magnitude, the concerned policymakers should solve pre-COVID-19 problems. The issues consist of the price war, geopolitical tensions and structural transformation which can minimize the magnitude of the impact and may help in speedy recovery. By solving the pre-COVID-19 issues may help because the market condition is more resilient to change. Moreover, the successful diversification of the energy system other than the conventional fossil fuels may help in minimizing the extent of pandemic shock. This is more important for the oil-exporting countries because of their heavy dependence on oil revenues and oil collapse may have negative repercussions. Last, the finding is useful for devising the energy management policies in response to the expected crisis in the future. The proactive measure can reduce the magnitude of the impact and risk of price collapse. We can expand this study to evaluate the explosive behaviour of EPs, as the pandemic has put pressure on global commodities. The disruption of the supply chain has affected commodities, which indicates an upward trend. The energy market is no exception and has been greatly impacted by the uncertainty of the pandemic. Similarly, the cointegration of these EPs can be examined in the context of pandemic uncertainty. It will be a useful discussion to investigate the relationship among different energy prices in the presence of COVID-19. Moreover, the pandemic has resulted in a rising trend in commodity prices which has severe consequences for the global economy. The EPs shows an explosive behaviour in the wake of the COVID-19 which is closely related with the other commodity market. Therefore, EPs bubble detection in different energy prices can be a useful area of future research that will offer useful information for the stakeholders.

Author statement

Khalid Khan: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software. Chi Wei Su: Data curation, Writing – original draft preparation. Meng Nan Zhu: Writing- Reviewing and Editing,

FUNDING

This research is supported by the National Social Science Fund of China (20BJY021).

Declaration of competing interest

We declare it this article has no conflicting interest.

References

- 1.Aloui D., Goutte S., Guesmi K., Hchaichi R. 2020. COVID 19's impact on crude oil and natural gas S&P GS Indexes. Available at: SSRN 3587740. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Algamdi A., Brika S.K.M., Musa A., Chergui K. COVID-19 deaths cases impact on oil prices: probable scenarios on Saudi Arabia economy. Frontires Pub Health. 2021;9:1–6. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.620875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amadi A.H., Ebube O.F., Aire S.I., Marcus C.B. Effects of covid-19 on crude oil price and future forecast using a model application and machine learning. European J Eng Technol Res. 2020;5(12):14–18. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aruga K., Islam M., Jannat A. Effects of COVID-19 on Indian energy consumption. Sustainability. 2020;12(14):5616. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aydin Gökhan, Karakurt I., Aydiner Kerim. Analysis and mitigation opportunities of methane emissions from the energy sector. Energy Sources, Part A Recovery, Util Environ Eff. 2012;34(11):967–982. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aydin Gökhan. The modeling and projection of primary energy consumption by the sources. Energy Sources B Energy Econ Plann. 2015;10(1):67–74. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aydin Gökhan. The Application of trend analysis for coal demand modeling. Energy Sources B Energy Econ Plann. 2015;10(2):183–191. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Azadeh A., Tarverdian S. Integration of genetic algorithm, computer simulation and design of experiments for forecasting electrical energy consumption. Energy Pol. 2007;35(10):5229–5241. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crowley P.M. A guide to wavelets for economists. J Econ Surv. 2007;21(2):207–267. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crowley P.M., Lee J. Bank of Finland Research Discussion Paper, (12); 2005. Decomposing the co-movement of the business cycle: a time-frequency analysis of growth cycles in the euro area. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Devpura N., Narayan K.P. Hourly oil price volatility: the role of COVID-19. Energy Res Lett. 2021;1(1):1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feng Y.Y., Zhang L.X. Scenario analysis of urban energy saving and carbon abatement policies: a case study of Beijing city, China. Procedia Environmental Sciences. 2012;13:632–644. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gao X., Ren Y., Umar M. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja; 2021. To what extent does COVID-19 drive stock market volatility? A comparison between the U.S. and China; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gozgor G., Lau C.K.M., Lu Z. Energy consumption and economic growth: new evidence from the OECD countries. Energy. 2018;153:27–34. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Graps A. An introduction to wavelets. IEEE Comput Sci Eng. 1995;2(2):50–61. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gupta R., Pierdzioch C., Selmi R., Wohar M.E. Does partisan conflict predict a reduction in US stock market (realized) volatility? Evidence from a quantile-on-quantile regression model. N Am J Econ Finance. 2018;43:87–96. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haniff N.M., Masih A.M.M. Do Islamic stock returns hedge against inflation? A wavelet approach. Emerg Mark Finance Trade. 2018;54(10):2348–2366. [Google Scholar]

- 18.IEA . International Energy Agency; Paris, France: 2020. Oil market report—april.https://www.iea.org/reports/oil-market-report-april-2020 Available online: 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 19.IEA . International Energy Agency; Paris, France: 2020. Gas (2020b)https://www.iea.org/reports/gas-2020 Available online: [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khan K., Su C.W., Umar M., Yue X.G. Do crude oil price bubbles occur? Resour Pol. 2021:101936. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jiang P., Van Fan Y., Klemeš J.J. Impacts of COVID-19 on energy demand and consumption: challenges, lessons and emerging opportunities. Appl Energy. 2021;285:116441. doi: 10.1016/j.apenergy.2021.116441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khan K., Su C.W., Tao R. Defence and Peace Economics; 2020. Does oil prices cause financial liquidity crunch? Perspective from geopolitical risk; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khurshid A., Khan K. Environmental Science and Pollution Research; Forthcoming: 2020. How COVID-19 shock will drive the economy and climate? A data-driven approach to model and forecast. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kingsly K., Henri K. 2020. COVID-19 and oil prices.https://ssrn.com/abstract=3555880 Available at: SSRN: [Google Scholar]

- 25.Köne A.Ç., Büke T. Forecasting of CO2 emissions from fuel combustion using trend analysis. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2010;14(9):2906–2915. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li K., Yuan W. The nexus between industrial growth and electricity consumption in China–New evidence from a quantile-on-quantile approach. Energy. 2021;231:120991. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maijama'a R., Musa K.S., Garba A., Baba U.M. Coronavirus outbreak and the global energy demand: a case of people's Republic of China. Am J Environ Resour Econ. 2020;5(1):10–13. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mallat S.G. A theory for multiresolution signal decomposition: the wavelet representation. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 1989;11(7):674–693. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mensi W., Sensoy A., Vo X.V., Kang S.H. Impact of COVID-19 outbreak on asymmetric multifractality of gold and oil prices. Resour Pol. 2020;69:101829. doi: 10.1016/j.resourpol.2020.101829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mzoughi H., Urom C., Uddin G.S., Guesmi K. The effects of COVID-19 pandemic on oil prices, CO2 emissions and the stock market: evidence from a VAR model. CO2 Emissions and the Stock Market: Evidence from a VAR Model. SSRN Electronic Journal. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Norouzi N., Zarazua de Rubens G.Z., Enevoldsen P., Behzadi Forough A. The impact of COVID-19 on the electricity sector in Spain: an econometric approach based on prices. Int J Energy Res. 2021;45(4):6320–6332. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Novan A., Machlev R., Carmon D., Onile E.A., Belikov J., Levron Y. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on energy systems and electric power grids—a review of the challenges ahead. Energies. 2021;14:1056. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nyga-Łukaszewska H., Aruga K. Energy prices and COVID-immunity: the case of crude oil and natural gas prices in the U.S. And Japan. Energies. 2020;13(23):6300. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Percival D.B., Mofjeld H.O. Analysis of subtidal coastal sea level fluctuations using wavelets. J Am Stat Assoc. 1997;92(439):868–880. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Qin M., Zhang Y.C., Su C.W. The essential role of pandemics-A fresh insight into the oil market. Energy Res Lett. 2021;1(1):1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Qin M., Su C.W., Tao R. BitCoin: a new basket for eggs? Econ Modell. 2021;94:896–907. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shahbaz M., Zakaria M., Shahzad S.J.H., Mahalik M.K. The energy consumption and economic growth nexus in top ten energy-consuming countries: fresh evidence from using the quantile-on-quantile approach. Energy Econ. 2018;71:282–301. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sharif A., Aloui C., Yarovaya L. COVID-19 pandemic, oil prices, stock market, geopolitical risk and policy uncertainty nexus in the U.S. economy: fresh evidence from the wavelet-based approach. Int Rev Financ Anal. 2020;70:101496. doi: 10.1016/j.irfa.2020.101496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shehzad K., Zaman U., Liu X., Górecki J., Pugnetti C. Examining the asymmetric impact of COVID-19 pandemic and global financial crisis on Dow Jones and oil price shock. Sustainability. 2020;13(9):4688. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shaikh I. Economic Change and Restructuring; 2021. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on the energy markets; pp. 1–52. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sim N., Zhou H. Oil prices, U.S. stock return, and the dependence between their quantiles. J Bank Finance. 2015;55:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Smith L.V., Tarui N., Yamagata T. Assessing the impact of COVID-19 on global fossil fuel consumption and CO2 emissions. Energy Econ. 2021;97:105170. doi: 10.1016/j.eneco.2021.105170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Su C.W., Khan K., Tao R., Nicoleta-Claudia M. Does geopolitical risk strengthen or depress oil prices and financial liquidity? Evidence from Saudi Arabia. Energy. 2019;187:116003. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Su C.W., Khan K., Tao R., Umar M. Energy; 2020. A review of resource curse burden on inflation in Venezuela; p. 204. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Su C.W., Khan K., Umar M., Zhang W. Does renewable energy redefine geopolitical risks? Energy Pol. 2021;158:112566. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Su C.W., Yuan X., Tao R., Umar M. Can new energy vehicles help to achieve carbon neutrality targets? J Environ Manag. 2021;297:113348. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.113348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Su C.W., Song Y., Umar M. Financial aspects of marine economic growth: from the perspective of coastal provinces and regions in China. Ocean Coast Manag. 2021;204:105550. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Su C.W., Cai X.Y., Qin M., Tao R., Umar M. Can bank credit withstand falling house price in China? Int Rev Econ Finance. 2021;71:257–267. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Su C.W., Qin M., Zhang X.L., Tao R., Umar M. Should Bitcoin be held under the US partisan conflict? Technol Econ Dev Econ. 2021;27(3):511–529. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tang C., Aruga K. Effects of the 2008 financial crisis and COVID-19 pandemic on the dynamic relationship between the Chinese and international fossil fuel markets. J Risk Financ Manag. 2020;14(5):207–212. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tao R., Umar M., Naseer A., Razi U. The dynamic effect of eco-innovation and environmental taxes on carbon neutrality target in emerging seven (E7) economies. J Environ Manag. 2021;299:113525. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.113525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tao R., Su C.W., Xiao Y., Dai K., Khalid F. Robo advisors, algorithmic trading and investment management: wonders of fourth industrial revolution in financial markets. Technol Forecast Soc Change. 2021;163:120421. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tao R., Su C.W., Yaqoob T., Hammal M. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja; 2021. Do financial and non-financial stocks hedge against lockdown in Covid-19? An event study analysis; pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Torrence C., Webster P.J. Interdecadal changes in the ENSO–monsoon system. J Clim. 1999;12(8):2679–2690. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yahya M., Oglend A., Dahl R.E. Temporal and spectral dependence between crude oil and agricultural commodities: a wavelet-based copula approach. Energy Econ. 2019;80:277–296. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yilmazkuday H. 2020. Coronavirus disease 2019 and the global economy. Available at: SSRN 3554381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang K.H., Su C.W., Lobonţ O.R., Umar M. Whether crude oil dependence and CO2 emissions influence military expenditure in net oil importing countries? Energy Pol. 2021;153:112281. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang K.H., Su C.W., Umar M. Geopolitical risk and crude oil security: a Chinese perspective. Energy. 2021;219:119555. [Google Scholar]