Abstract

A mathematical model for the co-interaction of COVID-19 and dengue transmission dynamics is formulated and analyzed. The sub-models are shown to be locally asymptotically stable when the respective reproduction numbers are below unity. Using available data sets, the model is fitted to the cumulative confirmed daily COVID-19 cases and deaths for Brazil (a country with high co-endemicity of both diseases) from February 1, 2021 to September 20, 2021. The fitting was done using the fmincon function in the Optimization Toolbox of MATLAB. Parameters denoting the COVID-19 contact rate, death rate and loss of infection acquired immunity to COVID-19 were estimated using the two data sets. The model is then extended to include optimal control strategies. The appropriate conditions for the existence of optimal control and the optimality system for the co-infection model are established using the Pontryagin’s Principle. Different control strategies and their cost-effectiveness analyses were considered and simulated for the model, which include: controls against incident dengue and COVID-19 infections, control against co-infection with a second disease and treatment controls for both dengue and COVID-19. Highlights of the simulation results show that: (1) dengue prevention strategy could avert as much as 870,000 new COVID-19 infections; (2) dengue only control strategy or COVID-19 only control strategy significantly reduces new co-infection cases; (3) the strategy implementing control against incident dengue infection is the most cost-effective in controlling dengue and COVID-19 co-infections.

Introduction

Dengue and Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) may share clinical and laboratory features [1]. Since 2018, increase in the number of dengue cases in at risk regions to arbovirus outbreaks such as the Reunion Island has been highlighted [1]. The 2019 Coronavirus disease (COVID-19), now a global pandemic, is a respiratory disease caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARSCoV- 2 [2]. In tropical and sub-tropical areas of the world where arboviruses (viral or bacterial infections) and COVID-19 may coexist due to the geographical overlap of the two diseases, clinical diagnosis is difficult, and patients should be tested for both viruses. Verduyn et al. [1] reported the first confirmed case of co-infection of dengue fever and COVID-19 in a French overseas department located in the Indian Ocean. A comprehensive review of the data on plausible co-infection in a single individuals of dengue and COVID-19 has been reported [3]. Co-epidemics can create a high burden on communities and the health system in the affected areas [4]. Although COVID-19 and dengue are caused by different viruses, the symptomatic appearance of both infections is quite identical and may be hard to distinguish [5]. These similarity of dengue and COVID-19 symptoms could lead to misdiagnosis of one disease for the other and therefore minimizing the extend of co-infection of the two diseases [6].

Due to clinical characteristics and underlying co-morbidities similar to COVID-19 [2, 4, 7], Saddique et al. [5] reported that co-infection of COVID-19 and dengue is an emerging public health concern in dengue endemic countries and investigated what role dengue co-infection plays on the severity and outcome of COVID-19 patients [2]. Co-infection of COVID-19 with vector-borne disease such as malaria is a public health threat [8]. In fact, co-infection of COVID-19 and dengue has already been reported from Asian countries and the Americas, see [9–11] and the references therein. These studies highlight high mortality rate in dengue and COVID-19 co-infected patients that may lead to adverse consequences [9]. Dengue viruses circulate throughout the year in Maldives, a dengue holoendemic country [12]. Because clinical and epidemiological criteria may not be sufficient to differentiate COVID-19 and dengue infection, several co-infected patients may be misdiagnosed [13], which could potentially lead to minimizing the extend of the co-infection. Paradoxically, there has been a decrease in dengue cases in Guangzhou (China), mainly attributable to the impact of COVID-19 lockdown in early 2020 [14]. However, the emergence of COVID-19 and dengue co-infection warrants further investigations, at least at the population level to understand the potential of COVID-19 and dengue outbreaks, which could be exacerbated during the post-monsoon months with elevated dengue infections. Also, the dynamics and outcome of a disease may be altered when co-infection with another disease is present [12]. However, non-severe dengue may be more symptomatic than COVID-19 in a co-epidemic dengue endemic settings [7].

Modeling is often the timely option for informing quick decision-making, and to this effect, mathematical modeling for public health purposes has become more refined and used to provide framework for understanding the dynamics of infectious diseases, especially when direct experiments are not possible [8, 15–25]. More recently, Rehman et al. [26] studied a fractional order model for COVID-19, comparing the behavior of the model using different derivatives (Caputo, Caputo–Fabrizio and Atangana–Baleanu) and showed that Caputo presented better results in the form of stability as compared to the other two operators. We formulate and analyze a robust mathematical model for the co-infection of COVID-19 and dengue transmission dynamics, with optimal control and cost-effectiveness analyses. Using available data sets, the proposed model is fitted to the cumulative confirmed daily COVID-19 cases and deaths for Brazil (a country with high co-endemicity of both diseases), and some important parameters are also estimated.

The organization of the rest of the paper is as follows. The proposed co-dynamic model is formulated in Sect. 2 and theoretically analyzed in Sect. 3. By applying Pontryagin’s maximum principle, optimal control of the model to mitigate the spread of both diseases and cost-effectiveness of the interventions is presented in Sect. 5. Numerical simulations performed to support theoretical results and cost-effectiveness analysis are presented in Sect. 6. The conclusion is provided in Sect. 7.

The model

Consider a homogeneously mixed population, i.e., individuals in the population have equal probability of contact with each other. Using a deterministic compartmental modeling approach to describe the disease transmission dynamics, at any time t, the total population is subdivided into several epidemiological states depending on individuals health status: susceptible humans , infectious individuals with dengue , individuals who have recovered from dengue , infectious individuals with COVID-19 , individuals who have recovered from COVID-19 , infectious individuals with co-infected with dengue and COVID-19 .

The mosquito vector population is given by comprises the susceptible vectors , and the infectious vectors with dengue . All the model parameters and their description are provided in 1, while the flows between all the model variables (compartments) are shown in Fig. 1.

Table 1.

Description of the variables and parameters

| Variable | Interpretation | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Susceptible humans | |||

| Infectious individuals with dengue | |||

| Individuals who have recovered from dengue | |||

| Infectious individuals with COVID-19 | |||

| Individuals who have recovered from COVID-19 | |||

| Infectious individuals with co-infected with dengue and COVID-19 | |||

| Susceptible vectors | |||

| Infectious vectors with dengue | |||

| Parameter | Interpretation | Value | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human recruitment rate | [27] | ||

| Vector recruitment rate | 20,000 | [28] | |

| Human natural death rate | [27] | ||

| Loss of infection acquired immunity to dengue | 0.026 | [29] | |

| Effective contact rate for vector to human transmission of dengue | 0.43 | [28] | |

| Effective contact rate for human to vector transmission of dengue | 0.60 | [28] | |

| Dengue recovery rate | 0.15 | [29] | |

| Effective contact rate for human to human transmission of COVID-19 | 0.1958 | Fitted | |

| Loss of infection acquired immunity to COVID-19 | 0.00000043117 | Fitted | |

| COVID-19-induced death rate | 0.0060 | Fitted | |

| COVID-19 recovery rate | 0.1853 | Fitted | |

| Modification parameter accounting for susceptibility of dengue-infected | |||

| Individuals to COVID-19 | 1 | Assumed | |

| Modification parameter accounting for susceptibility of COVID-19-infected | |||

| Individuals to dengue | 1 | Assumed | |

| Dengue-induced death rate | 0.001 | [28] | |

| Vector removal rate | [28] |

Fig. 1.

Compartment diagram of the human component of the model

The model has the following assumptions:

-

i.

individuals infected with COVID-19 infection are susceptible to infection with dengue and vice versa.

-

ii.

co-infected infected individuals can transmit either COVID-19 or dengue but not the mixed infections at the same time,

-

iii.

co-infected infected individuals can recover either from COVID-19 or dengue but not from the mixed infections at the same time,

-

iv.

Rate of transmissibility for singly infected and co-infected individuals are assumed same.

Individuals are recruited into the population through birth or immigration at the rate . Susceptible humans, acquire COVID-19, following effective contacts with either singly or co-infected individuals with COVID-19 at the rate:

| 1 |

Similarly, the population is reduced due to infection with dengue at the rate:

| 2 |

The parameters and denote the effective contact rate for the acquisition of COVID-19 and dengue, respectively. The variables in the expressions are defined in Table 1.

Following from the assumptions above, the COVID-19-dengue co-infection model is given by the following system of equations (the flow diagram of the model is presented in Fig. 1, and related parameters of the model are given in Table 1.

From Fig. 1, we establish the following system of nonlinear ordinary differential equation describing the dynamics of dengue and COVID-19 co-infection.

| 3 |

with initial conditions

| 4 |

Model analysis

The main focus of our study is on investigating the impact of optimal control on dengue-COCIVD-19 co-dynamics. For this reason, the basic analysis of the dengue-only and COVID-19-only sub-models will focus on deriving the infection threshold parameter that governs the stability of the model equilibria.

Invariant regions

Since the above model monitors human and mosquito populations, it is assumed that all the state variables and parameters of the model are non-negative for all time . The COVID-19 and dengue transmission model (3) will therefore be analyzed in a feasible region .

Lemma 3.1

Solutions of model system (3) are contained in the region

Proof

Let

and

Assume that is a solution of the system with non-negative initial conditions. Then, by summing all the equations of the human-only component of the system (3) we have

Thus, on applying Birkhoff and Rota’s Theorem on differential inequality [30], as we obtain . Therefore, all feasible solutions of the human-only component of the system (3) enters the region

Similarly, it can be shown that

Thus, for , all possible solutions of (3) will enter the region which is positively invariant under the flow induced by the model system (3). Also, using the theory of permanence, it can be shown that all solutions on the boundary of eventually enter the interior of [31], and the usual existence, uniqueness and continuation results hold. Hence, the model system (3) is well-posed mathematically and epidemiologically, and it is sufficient to consider the dynamics of the flow generated by the model (3) in . Note that the proof of the boundedness of solutions uses the Gronwall’s inequality, see [32].

Analysis of the model without controls

Before analyzing the dynamics of the full model (3), we first analyze the two sub-models namely: COVID-19-only and dengue-only models.

COVID-19-only model

The COVID-19-only model is obtained by setting in (3). Thus, we have,

| 5 |

where, now, the total human population is given by, By adding up all the equations of the system (5), we have

Consider the region

Note that the region is positively invariant [33], and it is sufficient to consider the dynamics of the dengue only sub-model (5) in .

The COVID-19-only model (5) has a DFE given by,

One measure of the potential for disease spread in a population is the threshold parameter know as the reproduction number, , which governs the local stability of the DFE of the COVID-19-only model. Using the approach in [34], the associated next generation matrices are given by

and

The associated basic reproduction number is given by

| 6 |

and the following result holds.

Lemma 3.2

The DFE of the COVID-19-only model (5) is locally asymptotically stable if and unstable if .

Proof

The stability of the DFE of the COVID-19-only model (5) is obtained from the eigenvalues of the characteristic polynomial, which states that the equilibrium is stable if the eigenvalues of the characteristic polynomial are all negative. For , the Jacobian matrix of the system is obtained as

The eigenvalues of characteristic polynomial are given by

Hence, the DFE of the COVID-19-only sub-model (5) is locally asymptotically stable if . For , prevalence of COVID-19 approaches an endemic equilibrium.

We will skip the proof of the global stability of the endemic equilibrium (EE) of model system (5) which was carried out in details in [8], where the COVID-19 only model is shown not to undergo the phenomenon of backward bifurcation, consequently, the EE of the model system (5) is globally asymptotically stable.

Dengue-only model

The dengue-only sub-model is obtained by setting in (3). Thus, we have

| 7 |

where, now, the total human population is and the vector population is The feasible region for the sub-model system (7) is

It can be shown that the region is positively invariant (so that it is sufficient to consider the dynamics of the model (7) in ).

The disease-free equilibrium (DFE) of the dengue-only model (7) is given by

and its associated next generation matrices are

and

so that,

| 8 |

The threshold parameter is the geometric mean of the average number of secondary host infections produced by one vector, and the average number of secondary vector infections produced by one host [35, 36]. In fact, the form of the basic reproduction number in a vector-borne disease is generally a geometric mean between infections caused by hosts and infections caused by vectors [36].

Lemma 3.3

The DFE of the Dengue-only model (7) is locally asymptotically stable if and unstable if .

Proof

The stability of the DFE of the Dengue-only model (7) is obtained from the eigenvalues of the characteristic polynomial, which states that the equilibrium is stable if the eigenvalues of the characteristic polynomial are all negative. For , the Jacobian matrix of the system is obtained as

The eigenvalues of characteristic polynomial are given by

and

where It can be shown that all eigenvalues of the characteristic equation have negative real parts if . Hence, the DFE of the Dengue-only model system (7) is locally asymptotically stable if .

For , prevalence of dengue approaches an endemic equilibrium.

Other analyses of the dengue-only sub-model have been adequately dealt with in [37], where also, the dengue only sub-model is shown to undergo the phenomenon of backward bifurcation under certain conditions.

Dengue-COVID-19 full model

The feasible region for system 3 is given by

with and are as defined in the previous sections. It can be shown following the approach in [15, 17] that all solutions of the co-infection Dengue-COVID-19 model system 3 with non-negative initial conditions remain non-negative for all time . Also, from the theory of permanence [31], all solutions on the boundary of eventually enter the interior of . Thus, is positively invariant and attracting under the flow induced by the system 3

Stability of the disease-free equilibrium

The disease-free equilibrium of the Dengue-COVID-19 3 is given by

| 9 |

Having derived the basic reproduction numbers for the COVID-19 only and Dengue only sub-models using the next generation method in [34], the associated reproduction number for the full model system 3 is given by

| 10 |

The following result follows from Theorem 2 in [34].

Theorem 4.1

The DFE of the Dengue-COVID-19 model 3 is locally asymptotically stable if the threshold parameter , and unstable if .

Optimal control model

In this section, we add time variant controls , , , and into (3) to obtain the optimal interventions for the eradication of COVID-19 and dengue. The controls are defined below:

-

i.

: control against incident dengue infection,

-

ii.

: control against incident COVID-19 infection,

-

iii.

: control against co-infection with a second disease,

-

iv.

: dengue treatment control,

-

v.

: COVID-19 treatment control.

The controls and satisfy following from the efficacy of the dengue vaccine reported in [29], , following the general efficacy of the COVID-19 vaccine [38], taking the average of both the dengue and COVID-19 vaccine efficacies. The dengue and COVID-19 treatment controls and are bounded as follows: , with the assumption that treatment cannot be 100% effective against either disease. The control system is presented thus:

| 11 |

subject to the initial conditions .

The following objective function is considered.

| 12 |

where T is the final time. The total cost includes the cost of COVID-19 and dengue vaccinations, and other preventive measures and COVID-19 and dengue treatment for all infected individuals. As a result, the nonlinear cost functional is used. In this sequel, we apply the quadratic objective functional for measuring the cost of the control [20]. We seek to find an optimal control, , such that

| 13 |

where , such that are measurable with , , for is the control set. The Hamiltonian is given by:

| 14 |

Theorem 5.1

Suppose the set minimizes J over U , then we have adjoint variables, (see Appendix for the expressions of ) satisfying the adjoint equations

with

| 15 |

Furthermore,

| 16 |

Proof of Theorem 5.1

Consider and being the associated solutions. Pontryagin’s Maximum Principle [39] is applied, such that there exist adjoint variables satisfying:

| 17 |

with .

On the interior of the set, where for all (), we have that

| 18 |

Therefore,

| 19 |

| 20 |

Baseline values of the parameters and model fitting

The total population of Brazil is estimated at 212,559,409 [27], while the life expectancy in Brazil is estimated at 75.88 years. Hence, we set the recruitment rat of humans to per day, whereas the natural death rate for humans is set at per day. The dengue recovery rate is estimated at 0.15 per day [28, 29] so that we set per day. There is no clinical evidence to tell us about the susceptibility of COVID-19 patients to dengue or vice versa. Hence, we set . The other dengue-related parameters are presented in Table 1, together with the references. The initial conditions are set as follows: . The total dengue cases in Brazil for 2021, as at August, 2021 are estimated at 671,732 [40]. Hence, we set , , . The total active COVID-19 cases as at February 1, 2021, were 942,878. Hence, we set . The total recoveries from COVID-19 as at that same day is 50,925. Thus, we set .

The model fitting was performed using fmincon function in the Optimization Toolbox of MATLAB [41]. Using the data sets for cumulative confirmed daily COVID-19 cases and deaths for Brazil from February 1, 2021, to September 20, 2021 [27], the COVID-19-related parameters are estimated as follows: = 0.1494, = 0.0047, = 0.36978. Figures 2 and 3 present the fitting of the model (3) to the cumulative confirmed daily COVID-19 cases and cumulative daily COVID-19 deaths for Brazil from 1 February, 2021 to 20 September, 2021. Both figures show that our model fits well to the two data sets obtained from [27]

Fig. 2.

Model fitting to cumulative confirmed daily COVID-19 cases for Brazil from 1 February, 2021 to 20 September, 2021

Fig. 3.

Model fitting to cumulative daily COVID-19 deaths for Brazil from 1 February, 2021 to 20 September, 2021

Numerical simulations

Simulations carried out on the control system (11), adjoint Eq. (17) and characterizations of the control (20) are run in MATLAB using the forward backward sweep by the Runge–Kutta method. The balancing factors are assumed as follows: . Likewise, the quadratic cost functions , and are applied, over time, in order to compute the total cost for each strategy implemented. The weight constants are set as follows: and . It is assumed here that, the cost of implementing the dengue prevention control (vaccination and use of treated bed nets and insecticides spray) is less compared to the cost of implementing the COVID-19 prevention control (vaccination, use of hand sanitizers and personal hygiene, use of face-masks in public places and use of personal protective equipments (PPE) by medical personnel). We also assumed that the cost of implementing control against co-infection with a second disease should be more than the cost of preventive control against respective diseases. It is also assumed that the cost of dengue treatment control should be less compared to the cost of COVID-19 treatment control.

Strategy A: Control against incident dengue infection ()

Simulations of the optimal control system (11) when the strategy that prevents incident dengue infection () is administered are presented in Figs. 4, 5, 6 and 7 , respectively. It is observed that when this intervention strategy is implemented, for and , so that the reproduction number, , there is a significant reduction in the number of individuals infected with dengue (Fig. 4) (as expected). Interestingly, this dengue prevention strategy also averts about 870,000 new COVID-19 cases (as depicted by Fig. 5). Also, worthy of note is that, this strategy against incident dengue infection also has positive population level impact on number of individuals co-infected with dengue and COVID-19 (as shown in Fig. 6, where a total of 4,196,644 new co-infection cases were averted). Moreover, this strategy also averts 346,181 cases of vector infections, thereby significantly reducing the infectious vector population (Fig. 7). The control profile for this control strategy is presented in Fig. 8. The control profile shows that this strategy is at its peak for the first 15 days, drops and then rises again and remains at its peak for the remaining days of the simulation.

Fig. 4.

Individuals infected with dengue when strategy A is implemented

Fig. 5.

Individuals infected with COVID-19 when strategy A is implemented

Fig. 6.

Individuals co-infected with dengue and COVID-19 infections when strategy1 A is implemented

Fig. 7.

Infectious vectors infected with dengue when strategy A is implemented

Fig. 8.

Control profile for strategy A

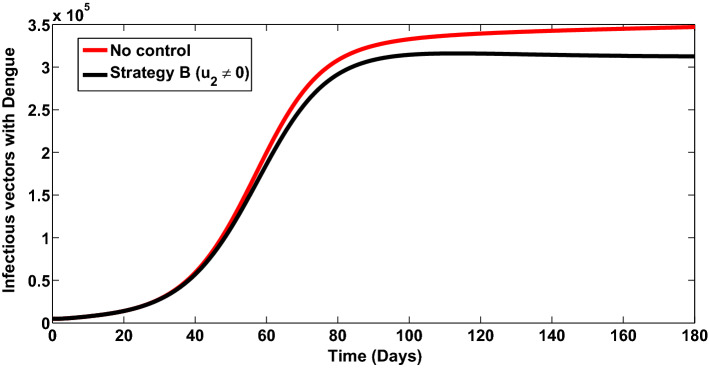

Strategy B: Control against incident COVID-19 infection ()

Simulations of the model (11) when the strategy that prevents incident COVID-19 infection () is implemented are presented in Figs. 9, 10 and 11. It is observed that when this strategy is implemented, for and , so that the reproduction number, , there is a significant reduction in the number of individuals infected with COVID-19 infection (Fig. 9) (as expected). Also, it is imperative to note that, this control against incident COVID-19 infection also has positive impact on number of individuals co-infected with dengue and COVID-19 (Fig. 10, where a total of 4,204,905 new co-infection cases were prevented). In addition, this control also averts about 34,400 vector infections, thereby significantly bringing down the infectious vector population (Fig. 11). The control profile for this control strategy is depicted in Fig. 12. The control profile shows that this strategy is at its peak for the first 15 days, drops and then rises again, and remains at its peak for the remaining days of the simulation.

Fig. 9.

Individuals infected with dengue when strategy B is implemented

Fig. 10.

Individuals co-infected with dengue and COVID-19 infections when strategy B is implemented

Fig. 11.

Infectious vectors infected with dengue when strategy B is implemented

Fig. 12.

Control profile for strategy B

Strategy C: Control against co-infection with a second disease ()

The optimal control simulations for the system (11) when the strategy that implements control against co-infection with a second disease () is administered are presented in Figs. 13 and 14 . It is revealed that when this strategy is implemented, for and , so that the reproduction number, , there is a great reduction in the co-infection new cases (as shown in Fig. 13), where a total of 3,155,000 co-infection new cases were averted. Also, this strategy also averts about 18,300 vector infections, thus significantly bringing down the infectious vector population (Fig. 14). The control profile for this control strategy is given in Fig. 15. The control profile shows that this strategy is at its peak for the entire simulation period.

Fig. 13.

Individuals co-infected with dengue and COVID-19 infections when strategy C is implemented

Fig. 14.

Infectious vectors infected with dengue when strategy C is implemented

Fig. 15.

Control profile for strategy C

Strategy D: Dengue treatment control ()

The control model (11) simulations when dengue treatment strategy alone () is administered are given in Figs. 16, 17 and 18 . It is observed that when dengue treatment strategy alone is implemented, for and , so that the reproduction number, , there is a gross reduction in the number of individuals infected with dengue (Fig. 16) (as expected). Also, worthy of note is that, this strategy equally has positive population level impact on co-infected individuals (as depicted by Fig. 17, where a total of 2,349,000 new co-infection cases were averted). In addition, this strategy also prevents 55,200 vector infections (as shown in Fig. 18). The control plot is presented in Fig. 19. The control profile shows that this strategy only attains its peak value and is most effective after about 120 days.

Fig. 16.

Individuals infected with dengue when strategy D is implemented

Fig. 17.

Individuals co-infected with dengue and COVID-19 infections when strategy D is implemented

Fig. 18.

Infectious vectors infected with dengue when strategy D is implemented

Fig. 19.

Control profile for strategy D

Strategy E: COVID-19 treatment control ()

The control model (11) simulations when COVID-19 treatment control () is the only administered strategy are presented in Figs. 20, 21 and 22 . It is seen from the simulations, which were carried out for and , so that the reproduction number, , that there is a significant reduction in the number of individuals infected with COVID-19 (Fig. 20) (as expected). Interestingly, this strategy also has positive population level impact on co-infection new cases (as presented in Fig. 21, where a total of 2,544,000 new co-infection cases were averted). Nonetheless, this strategy also averts about 11,200 cases of vector infections, thus bringing down the infectious vector population (Fig. 22). The control plot against time, for this strategy, is given in Fig. 23. The control profile shows that this strategy attains its peak value for the initial days of the simulation, drops and then rises to its peak again after about 140 days.

Fig. 20.

Individuals infected with dengue when strategy E is implemented

Fig. 21.

Individuals co-infected with dengue and COVID-19 infections when strategy E is implemented

Fig. 22.

Infectious vectors infected with dengue when strategy E is implemented

Fig. 23.

Control profile for strategy E

Cost-effectiveness analysis

In this section, we seek to determine the intervention strategy which is most cost-effective in the fight against dengue and COVID-19 co-infections. In order to realize this, the methods used are: the average cost-effectiveness ratio (ACER) and the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER). ”The cost-effectiveness analysis is used to evaluate the health interventions related benefits so as to justify the costs of the strategies . This is obtained by comparing the differences among the health outcomes and costs of those interventions. ACER deals with a single intervention strategy and weighing the intervention against its baseline option. It is the ratio of the total cost of the intervention to the total number of infection averted by the intervention” [20]. The formula is as follows:

In a similar manner, ICER deals with the comparison of the differences in the costs and health benefits of two alternate competing interventions. ”It is the ratio of the change in costs of two alternative strategies to the change in the total number of infection averted by the two strategies”. The ICER formula is given by:

Since our major objective is on how to reduce the co-infection of both dengue and COVID-19 in the population, the total co-infected cases averted and the total cost of the strategies applied shall be used for the cost-effectiveness analysis in this section. These are presented in Table 2. The total cases averted is obtained by calculating the difference in the population of co-infected individuals when control is applied and when control is not applied.

Table 2.

Increasing order of the total co-infection cases averted using the control strategies

| Strategy | Total infection averted | Total cost | ACER |

|---|---|---|---|

| D: | 2,349,000 | 1000 | 0.0004257 |

| E: | 2,544,000 | 1200 | 0.0004717 |

| C: | 3,155,930 | 2000 | 0.006339 |

| A: | 4,196,644 | 900 | 0.002145 |

| B: | 4,204,905 | 1500 | 0.0003567 |

The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) for strategies D (dengue treatment control ) and strategy E (COVID-19 treatment control ) are now evaluated.

Comparing ICER (D) and ICER(E), it is observed that ICER (E) is greater than ICER (D), showing that strategy E is more costly and less effective compared to strategy D. Therefore, strategy E is removed from proceeding ICER computations, shown in Table 3. We shall now compare strategies D and C (Table 4).

Table 3.

ICER computations for strategies D and E

| Strategy | Total infection averted | Total cost | ACER | ICER |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| D: | 2,349,000 | 1000 | 0.0004257 | 0.0004257 |

| E: | 2,544,000 | 1200 | 0.0004717 | 0.001026 |

Table 4.

ICER computations for strategies D and C

| Strategy | Total infection averted | Total cost | ACER | ICER |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| D: | 2,349,000 | 1000 | 0.0004257 | 0.0004257 |

| C: | 3,155,000 | 2000 | 0.0006339 | 0.001241 |

Computing ICER for strategies D (dengue treatment control ()) and C (control against co-infection with a second disease ()), it is observed that ICER (C) is greater than ICER (D), showing that strategy C is more costly and less effective compared to strategy D. Hence, strategy C is removed from subsequent ICER computations. We shall now compare strategies D and A (Table 5).

Computing ICER for strategies D (dengue treatment control ()) and A (control against incident dengue infection ()), it is observed that ICER (D) is greater than ICER (A), showing that strategy D is more costly and less effective compared to strategy A. Thus, strategy A is used in subsequent ICER computations, while strategy D is removed. We shall now compare strategies A and B (Table 6).

Table 5.

ICER computations for strategies D and A

| Strategy | Total infection averted | Total cost | ACER | ICERr |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| D: | 2,349,000 | 1000 | 0.0004257 | 0.0004257 |

| A: | 4,196,644 | 900 | 0.0003567 | – 0.00005412 |

Table 6.

ICER computations for strategies A and B

| Strategy | Total infection averted | Total costr | ACER | ICER |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A: | 4,196,644 | 900 | 0.0002145 | 0.0002145 |

| B: | 4,204,905 | 1500 | 0.0003567 | 0.07263 |

Computing ICER for strategies A (control against incident dengue infection ()) and B (control against incident COVID-19 infection ()), it is observed that ICER (B) is greater than ICER (A), showing that strategy B is more costly and less effective compared to strategy A. Hence, strategy A is the most cost-effective in controlling dengue and COVID-19 co-infections.

Conclusion

We have formulated and analyzed a mathematical model for the co-infection and COVID-19 and dengue transmission dynamics, with optimal control and cost-effectiveness analysis. The sub-models are shown to be locally asymptotically stable when the respective reproduction numbers are below unity. Using available data sets, the model is fitted to the cumulative confirmed daily COVID-19 cases and deaths for Brazil (a country with high co-endemicity of both diseases) from February 1, 2021 to September 20, 2021. The fitting was done using the fmincon function in the Optimization Toolbox of MATLAB. Parameters denoting the COVID-19 contact rate, death rate and loss of infection acquired immunity to COVID-19 were estimated using the two data sets. The appropriate conditions for the existence of optimal control and the optimality system for the co-infection model are established using the Pontryagin’s Principle. Different control strategies were considered and simulated for the model, which include: controls against incident dengue and COVID-19 infections, control against co-infection with a second disease and treatment controls for both dengue and COVID-19. Highlights of the simulation results show that:

-

i.

dengue prevention strategy could avert as much as 870,000 new COVID-19 infections (as depicted in Fig. 5);

-

ii.

dengue only control strategy or COVID-19 only control strategy significantly reduces new co-infection cases. These are presented in Figs. 6 and 10 ;

-

iii.

the strategy that implements control against incident COVID-19 infection (vaccination, use of hand sanitizers and personal hygiene, use of face-masks in public places and use of personal protective equipments (PPE) by medical personnel) averts the highest number of co-infection cases than any of the administered control strategies. This is depicted by Fig. 10, where a total of 4,204,905 new co-infection cases were averted.

-

iv.

the strategy implementing control against incident dengue infection is the most cost-effective in controlling dengue and COVID-19 co-infections as presented in Sect. 6.6).

As COVID-19 pandemic threatens the delivery of dengue services, the lockdown could have further impacted the continuation of dengue control programs, and there is an urgent need for rapid and effective responses to avoid dengue outbreaks.

Our model was created based on the focus of COVID-19 and dengue co-infection only. Thus, we did not investigate the impact of multiple COVID-19 stains and waves on the dynamics of the two diseases. Also, the emergence of COVID-19 and dengue co-infection warrants further investigations at the individual level (within host dynamics). While this is to the best of our knowledge seemingly the first study of the co-interaction of COVID-19 and dengue, more studies should be devoted to the mathematical (agent based, within/intra-host dynamics) and epidemiological dynamics of this co-infection. Due to the uncertainty of several aspects and characteristics of both diseases, we realize the difficulty in finding estimates for certain parameters in this study. Specific parameters difficult to estimate are the modification parameters accounting for susceptibility of dengue infected individuals to COVID-19 and the modification parameter accounting for susceptibility of COVID-19 infected individuals to dengue. Because mathematical models are symbolic representations of biological systems, by construction, they inherit the loss of information which could potentially make the prediction of model outcomes imprecise. Therefore, exploring sensitivity analysis of the model variables and parameters to changes in the assumptions made regarding the characteristics of the disease is viable.

It is important to note from Fig. 15 that the control for the co-infection is optimally applied for the entire simulation period. On the contrary, the other four controls and all start at a high lever, but deepens after a short time before returning to the optimum. This striking result may be due to the initial inadequate treatment when the disease emerged, and vaccine hesitancy/denial at the onset of the vaccination campaign. It has been reported how hesitancy/denial is challenging the vaccination campaigns with the number of those infected increasing relative to the percentage of population that avoids getting vaccinated [42]. This is an area that warrants further investigation as well as the impact of multiple waves of COVID-19 on disease co-interaction.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments and queries which greatly help improve the manuscript.

Appendix: Adjoint functions of optimality system

Data Availability Statement

This manuscript has associated data in a data repository. [Authors’ comment: The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.]

References

- 1.Verduyn M, Allou N, Gazaille V, Andre M, Desroche T, Jaffar M-C, et al. Co-infection of dengue and COVID-19: a case report. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2020;14(8):e0008476. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0008476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Masyeni S, Santoso MS, Widyaningsih PD, Asmara DW, Nainu F, Harapan H, Sasmono RT. Serological cross-reaction and coinfection of dengue and COVID-19 in Asia: experience from Indonesia. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2021;102:152–154. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.10.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lansbury L, Lim B, Baskaran V, Lim WS. Co-infections in people with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Infect. 2020;81(2):266–275. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.05.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Malibari AA, Al-Husayni F, Jabri A, Al-Amri A, Alharbi M. A patient with dengue fever and COVID-19: coinfection or not? Cureus. 2020;12(12):e11955. doi: 10.7759/cureus.11955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saddique A, Rana MS, Alam MM, et al. Emergence of co-infection of COVID-19 and dengue: a serious public health threat. J. Infect. 2020;81(6):e16–e18. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hussein MIH, Albashir AAD, Elawad OAMA, et al. Malaria and COVID-19: unmasking their ties. Malar. J. 2020;19:457. doi: 10.1186/s12936-020-03541-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Joubert A, Andry F, Bertolotti A, Accot F, Koumar Y, Legrand F, et al. Distinguishing non severe cases of dengue from COVID-19 in the context of co-epidemics: a cohort study in a SARSCoV-2 testing center on Reunion island. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2021;15(4):e0008879. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0008879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tchoumi SY, Diagne ML, Rwezaura H, Tchuenche JM. Malaria and COVID-19 co-dynamics: a mathematical model and optimal control. Appl. Math. Model. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.apm.2021.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miah MA, Husna A. Coinfection, coepidemics of COVID-19, and dengue in dengue-endemic countries: a serious health concern. J. Med. Virol. 2021;93(1):161–162. doi: 10.1002/jmv.26269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nacher M, Douine M, Gaillet M, Flamand C, Rousset D, Rousseau C, et al. Simultaneous dengue and COVID-19 epidemics: difficult days ahead? PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2020;14(8):e0008426. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0008426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khalil A, Badr B, Wright H, Talo M, Atteiya M. Dengue fever and COVID-19 co-infection at the emergency department of a tertiary care hospital in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Eur J. Case Rep. Intern. Med. 2020;7(12):002167. doi: 10.12890/2020_002167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hilmy AI, Dey RK, Imad HA, et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 and dengue: two case reports. J. Med. Case Rep. 2021;15:171. doi: 10.1186/s13256-021-02707-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haqqi A, Awan UA, Ali M, Saqib MAN, Ahmed H, Afzal MS. COVID-19 and dengue virus coepidemics in Pakistan: a dangerous combination for an overburdened healthcare system. J. Med. Virol. 2021;93(1):80–82. doi: 10.1002/jmv.26144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jiang L, Liu Y, Su W, Liu W, Yang Z. Decreased dengue cases attributable to the effect of COVID-19 in Guangzhou in 2020. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2021;15(5):e0009441. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0009441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mtisi E, Rwezaura H, Tchuenche JM. A mathematical analysis of malaria and tuberculosis co-dynamics. Discrete Cont. Dyn. Syst. B. 2009;12(4):827–864. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pinto CMA, Tenreiro MJA. Fractional model for malaria transmission under control strategies. Comput. Math. Appl. 2013;66(5):908–916. doi: 10.1016/j.camwa.2012.11.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mukandavire Z, Gumel AB, Garira W, Tchuenche JM. Mathematical analysis of a model for HIV-malaria co-infection. Math. Biosci. Eng. 2009;6(2):333–362. doi: 10.3934/mbe.2009.6.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kavitha C, Gowrisankar A, Banerjee S. The second and third waves in India: when will the pandemic be culminated? Eur. Phys. J. Plus. 2021;136:596. doi: 10.1140/epjp/s13360-021-01586-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Easwaramoorthy D, Gowrisankar A, Manimaran A, Nandhini S, Rondoni L, Banerjee S. An exploration of fractal-based prognostic model and comparative analysis for second wave of COVID-19 diffusion. Nonlinear Dyn. 2021;8:1–21. doi: 10.1007/s11071-021-06865-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Omame A, Nnanna CU, Inyama SC. Optimal control and cost-effectiveness analysis of an HPV-chlamydia trachomatis co-infection model. Acta Biotheor. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s10441-020-09401-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Omame A, Okuonghae D. A co-infection model for oncogenic Human papillomavirus and tuberculosis with optimal control and cost-effectiveness analysis. Optim. Control. Appl. Methods. 2021 doi: 10.1002/oca.2717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chukukere EC, Omame A, Onyenegecha CP, Inyama SC. Mathematical analysis of a model for Chlamydia and Gonorrhea codynamics with optimal control. Results Phys. 2021;27:104566. doi: 10.1016/j.rinp.2021.104566. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nwajeri UK, Omame A, Onyenegecha CP. A fractional order model for HPV and CT co-infection. Results Phys. 2021;28:104643. doi: 10.1016/j.rinp.2021.104643. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Njeuhmeli E, Schnure M, Vazzano A, Gold E, Stegman P, Kripke K, Tchuenche M, Bollinger L, Forsythe S, Hankins C. Using mathematical modeling to inform health policy: a case study from voluntary medical male circumcision scale-up in eastern and southern Africa and proposed framework for success. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(3):e0213605. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0213605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Okuonghae D, Omame A. Analysis of a mathematical model for COVID-19 population dynamics in Lagos, Nigeria. Chaos Solitons Fractals. 2020;139:110032. doi: 10.1016/j.chaos.2020.110032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rehman A, Singh R, Agarwal P. Modeling, analysis and prediction of new variants of Covid-19 and dengue co-infection on complex network. Chaos Solitons Fractals. 2021;150:111008. doi: 10.1016/j.chaos.2021.111008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brazil: Coronavirus Pandemic Country Profile. https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus/country/brazil. Accessed 21st Sep 2021

- 28.Garba SM, Gumel AB, Abu Bakar MR. Backward bifurcations in dengue transmission dynamics. Math. Biosci. 2008;215:11–25. doi: 10.1016/j.mbs.2008.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.K.O. Okuneye, J.X. Velasco-Hernandez, A.B. Gumel, The “unholy” Chikungunya-Dengue-Zika Trinity: a theoretical analysis. J. Biol. Syst. 25(4), 545–585 (2017)

- 30.Birkhoff G, Rota GC. Ordinary Differential Equations. 4. New York: Wiley; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hutson V, Schmitt K. Permanence and the dynamics of biological systems. Math. Biosci. 1992;111:1–71. doi: 10.1016/0025-5564(92)90078-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nazir A, Ahmed N, Khan U, Mohyud-Din ST, Sooppy NKS, Khan I. An advanced version of a conformable mathematical model of Ebola virus disease in Africa. Alex. Eng. J. 2020;59(5):3261–3268. doi: 10.1016/j.aej.2020.08.050. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ali M, Shah STH, Khan MIA. The role of asymptomatic class, quarantine and isolation in the transmission of COVID-19. J. Biol. Dyn. 2020;14(1):389–408. doi: 10.1080/17513758.2020.1773000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van den Driessche P, Watmough J. Reproduction numbers and sub-threshold endemic equilibria for compartmental models of disease transmission. Math. Biosci. 2002;180(1):29–48. doi: 10.1016/S0025-5564(02)00108-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kribs-Zaleta C. Vector consumption and contact process saturation in sylvatic transmission of T. cruzi. Math. Pop. Stud. 2016;13:132–152. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Crawford B, Kribs-Zaleta C. A metapopulation model for sylvatic T. cruzi transmission with vector migration. Math. Biosci. Eng. 2014;11(3):471–509. doi: 10.3934/mbe.2014.11.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bonyah E, Khan MA, Okosun KO, Gómez-Aguilar JF. On the co-infection of dengue fever and Zika virus. Optim. Control Appl. Methods. 2019;40(3):394–421. doi: 10.1002/oca.2483. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Interim Clinical Considerations for Use of COVID-19 Vaccines Currently Authorized in the United States https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/clinical-considerations/covid-19-vaccines-us.html . Accessed July 14, 2021

- 39.L. Pontryagin, V. Boltyanskii, R. Gamkrelidze, E. Mishchenko, The Mathematical Theory of Optimal Control Process 4, New York/London 1962 (Wiley, New York, 1963)

- 40.Pan American Health Organization https://www3.paho.org/data/index.php/en/mnu-topics/indicadores-dengue-en.html. Accessed 4th Aug 2021

- 41.McCall J. Genetic algorithms for modelling and optimisation. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2005;184:205–222. doi: 10.1016/j.cam.2004.07.034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yigit M, Ozkaya-Parlakay A, Senel E. Evaluation of COVID-19 vaccine refusal in parents. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2021;40(4):e134–e136. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000003042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

This manuscript has associated data in a data repository. [Authors’ comment: The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.]