Abstract

Individuals diagnosed with thoracic aortic aneurysm/dissection (TAAD) are given activity restrictions in an attempt to mitigate serious health complications and sudden death. The psychological distress resulting from activity restrictions has been established for other diseases or patient populations; however, individuals with non-syndromic TAAD have not been previously evaluated. Seventy-nine participants completed a questionnaire utilizing the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) and Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7) questionnaires, which assess levels of depression and anxiety respectively. Additionally, quantitative and qualitative questions explored self-reported psychological distress in response to activity restrictions. Individuals who reported higher PHQ + GAD scores had been living with a diagnosis longer than two years (p = 0.0004), were between 35 and 65 years old (p = 0.05), reported not coping well (p = 0.0035), and reported physical activity was “very important” (p = 0.04). Results from individual questions showed that individuals who reported their diagnosis affected them financially were 3.5 times more likely to report “feeling nervous, anxious, or on edge” (CI = [0.81, 15.6], p = 0.094). Qualitative analysis revealed themes that identified participant beliefs regarding distress, ability to cope, hindrances to coping ability, and resources. These results show psychological distress can result from physical activity restrictions in non-syndromic TAAD individuals. Additionally, certain subpopulations may be more susceptible to distress. This is the first study to examine the psychological distress individuals with non-syndromic TAAD experience as a result of prescribed activity restrictions. Genetic counselors and other healthcare professionals can utilize this information to provide more tailored cardiovascular genetic counseling and increase its therapeutic potential for patients.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12687-021-00545-0.

Keywords: Distress, Coping, Mental health, Psychosocial, Aortic aneurysm, Heart disease

Introduction

Thoracic aortic aneurysm and dissection (TAAD) is a potentially life-threatening cardiovascular disorder with serious medical implications and an incidence of 6 to 10 cases per 100,000 patient-years in the USA (Black et al. 2018). TAAD occurs as the result of known genetic conditions, such as Marfan, Loeys-Dietz, or vascular Ehlers-Danlos syndromes; however, as many as 20% of individuals with TAAD have a family history of the heart condition without a known syndromic etiology (Black et al. 2018). While all TAAD cases diagnosed under the age of 50 are thought to be genetic, these accepted incidence rates are likely an underestimate due to undiagnosed TAAD (Elefteriades and Farkas 2010). Individuals with non-syndromic TAAD will likely be seen more frequently by genetics professionals as genetic testing becomes increasingly available and part of the standard of care. As the non-syndromic TAAD population becomes more visible in the clinical setting, it is imperative that the most useful genetic counseling approaches are identified and implemented in order to effectively address psychological distress.

Individuals with a TAAD diagnosis are at an increased risk for sudden death. Because chronic aortic stress contributes to this risk, these individuals are recommended to refrain from high-intensity sports, heavy lifting, and isometric activities that can exacerbate aortic stress and increase their risk of sudden death beyond baseline. Instead, individuals with TAAD are encouraged to participate in low-intensity, noncompetitive exercise based on their degree of dilation and underlying etiology (Maron et al. 2015; Braverman et al. 2015). The American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology state that it is unfortunate for someone to have to withdraw from or cease particular physical activities, which can otherwise positively impact physiological and psychological health. It is not surprising that restricting physical activies leads to higher rates of depression in individuals with cardiac disease (Maron et al. 2015; Mausbach et al. 2011). In fact, competitive athletes diagnosed with cardiac disease were found to be profoundly impacted by activity restriction and experienced stages similar to those of grief (Asif et al. 2015). Furthermore, individuals with thoracic aortic disease experienced a reduced health-related quality of life due to their activity restrictions compared to a sex- and age-matched reference group (Olsson and Franco-Cereceda 2013).This study did not differentiate between syndromic and non-syndromic TAAD individuals; therefore, it is difficult to identify the cause of their reduced health-related quality of life. Although several studies have established the relationship between activity restrictions and psychological distress, and examined this distress in various populations with heart-related conditions (Liuten et al. 2016), it has not been explored specifically in non-syndromic TAAD patients. This study includes only non-syndromic patients in an effort to eliminate the potential confounding factor of a syndromic diagnosis, which can give rise to unique and often more complex psychological implications.

Genetic counselors are often involved in the process of providing the unwelcome news that a lifestyle of reduced physical activity should be adapted to reduce risk, yet there is no literature to help identify who might be at higher risk for emotional distress, or to suggest how genetic counselors can advise individuals on mitigating this distress. By definition, genetic counselors assist patients in the process of understanding the genetic basis of a disease and adapting to the psychological impact of genetic disease (Resta et al. 2006). This study explored distress levels experienced as a result of physical activity restrictions due to a non-syndromic TAAD diagnosis, in addition to demographic and lifestyle factors, to identify characteristics of at-risk patients who may be more susceptible to psychological distress. This could inform the framework that genetic counselors utilize to assist these individuals diagnosed with non-syndromic TAAD to mitigate feelings of depression and/or anxiety. In addition, the results of this study can improve post-diagnosis counseling by providing specific characteristics of individuals reporting increased depression and/or anxiety as well as increase awareness of the therapeutic potential of cardiovascular genetic counseling.

Methods

Participants

This study was approved by and carried out in accordance with the Indiana University Institutional Review Board (IRB# 1,705,458,555). Participants were enrolled between July 2019 and December 2019. Inclusion criteria included a diagnosis of TAAD; age 14 years or older; English-speaking; Indiana University Health (IUH) facility patient; no clinical or molecular diagnosis of TAAD syndromes including Marfan, Loeys-Dietz, vascular EDS, or another syndrome that explains the etiology of their TAAD. All TAAD diagnoses were verified by a cardiologist in an independent review of the echocardiogram or imaging used for the diagnosis. Individuals were invited to participate only if they had not received genetic testing or had genetic testing that did not identify a pathogenic or likely pathogenic variant in any gene analyzed. Eligible individuals were identified through the Cardiovascular Genetics clinics at IUH facilities as well as from the Pathogenetic Basis of Aortopathy and Aortic Valve Disease study (IRB# 150,997,731) and confirmed via the individuals’ electronic medical records. They were notified of their eligibility via an e-mail or a telephone call from study personnel. Upon notification, these individuals had the option to complete the survey online, request a mailed paper version of the survey instrument, or decline participation. Eligible individuals received up to three follow-up emails or phone calls. In total, 109 individuals consented to participate in the study, of whom 79 completed the questionnaire. The remaining 30 individuals did not complete the questionnaire and were excluded from data analyses.

Instrumentation

In order to assess psychological distress experienced by this patient population, we utilized a mixed-methods survey consisting of both quantitative and qualitative questions. Study data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at the Indiana Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute. REDCap is a secure, web-based application designed to support data capture for research studies (Harris et al. 2009). The survey instrument is provided as Supporting Information. Participants were first asked questions from the previously validated Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) and General Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7) questionnaires (Kroenke et al. 2016). The PHQ-9 consists of nine self-report questions while the GAD-7 consists of seven self-report questions. These assess an individual’s level of depression and anxiety, respectively, and have a reported Cronbach’s alpha of 0.8–0.9 when used in combination (Kroenke et al. 2016).

Responses to both questionnaires were provided as a 4-point Likert scale reporting the frequency that individuals experienced particular problems or feelings during a 2-week period. Potential responses included “not at all,” “several days,” “more than half the days,” and “nearly every day.” The responses were coded as 0, 1, 2, and 3 respectively (Kroenke et al. 2001; Spitzer et al. 2006) and summed to represent a total score. For each questionnaire, we asked the participants to answer the questions based on their feelings at the time they received their activity restrictions.

Additional demographic information collected included gender, current age, age at diagnosis, and race. Information related to the TAAD diagnosis included diagnoses of mental illness(es) before or after activity restrictions were placed and whether or not the activity restrictions had affected the individual financially, with “inability to continue current job, loss of athletic scholarship, etc.” provided as examples. Space was also provided for an open-ended response to “explain how you were affected financially in detail.” Participants were also asked about activity level prior to restrictions, importance of physical activity, and their adherence to the activity restriction guidelines using a 4-point Likert scale with 1 = extremely active, very important, and strict adherence, and 4 = never active, of no importance, and no adherence.

Qualitative data collection and analysis

Qualitative data were collected using open-ended questions throughout the questionnaire, the list of which can be found in the Supporting Information. Qualitative questions were utilized to further delineate psychological distress and collect information regarding factors which helped or hindered ability to cope with activity restrictions. Specifically, participants were asked (1) to personally assess their ability to cope; (2) if they attended a support group; (3) what hobbies or organizations they were involved in, such as a church or book club; (4) the factors that helped and/or hindered their ability to cope; (5) any resource(s) that could have been helpful to them following their TAAD diagnosis. The responses were analyzed by study personnel using thematic analysis completed by AM and then themes were confirmed by BMH as followed by that described by Vaismoradi et al. (2013). When a response was seen two or more times, it was categorized into a theme. Themes were considered to be mutually exclusive. Any responses seen only one time were compiled into a theme categorized as “other.” Answers that were left blank or stated “N/A” were not considered in the final analysis. Data were collected for the question of additional hobbies and activities of the participants; however, due to the variety in responses, comprehensive and segregated themes were unable to be constructed for these data and are therefore not reported.

Quantitative data analysis

PHQ and GAD data

The majority of respondents scored between 0 and 4 out of a possible 27 on the PHQ-9 (70%) or between 0 and 4 out of a possible 21 on the GAD-7 (73%). Therefore, the scores for both scales were added together to represent an overall score (PHQ + GAD) for depression and anxiety. Secondary analyses explored individual PHQ-9 or GAD-7 questions to assess specific topics of depression or anxiety. If the participant responded that they ever experienced the outcome (“several days,” “more than half the days,” or “nearly every day”), the response was recoded as “yes.” If the participant responded “not at all,” then the response was recoded as “no.” If more than 33% answered either yes or no, that specific question was included for further analysis.

Recoded variables

The majority of participants answered positively to the questions asking about physical activity and adherence to restrictions. Three people responded, “rarely active” or “never active” to the question “What would you consider your activity level to have been prior to your diagnosis?” For the question asking about importance of physical activity, one person responded, “of little importance” and one person responded, “of no importance.” For the question asking about adherence to physical activity restriction guidelines, five people responded, “little adherence” or “no adherence.” Therefore, these three questions were analyzed as binary variables comparing the most extreme category to all other categories, specifically “extremely active” vs. all other responses for acitivity level prior to diagnosis, “very important” vs. all other responses for importance of physical activity, and “strict adherence” vs. all other responses for adherence to physical activity restriction guidelines.

To explore if individuals diagnosed recently responded differently than those living for a longer period of time with a diagnosis, the length of time living with a diagnosis was calculated as current age – age at TAAD diagnosis. A binary categorical variable was coded as follows: those living with a diagnosis in the last 2 years (length of time with diagnosis ≤ 2 years) and those living with a diagnosis for > 2 years. Similarly, to distinguish if younger individuals responded different than older individuals, an age group variable was coded for three groups defined as follows: current age ≤ 35 years, 35 < current age < 65, and current age ≥ 65 years.

Statistical analyses

The data were examined for potential confounds between demographic variables. Tests of associations between categorical demographic variables were performed using chi-squared tests, denoted as X2 (degrees of freedom). Student t-tests were used to test if quantitative variables were different between binary demographic variables. An analysis of variance (ANOVA) was employed to test if the following factors predicted the total PHQ + GAD score: financial effect (yes/no), gender, activity prior to diagnosis, importance of physical activity, age group (3 groups divided at age 35 and 65), time with a diagnosis (≤ 2 years vs. > 2 years), type of hobby, how well the individual reported coping with the diagnosis (well, fair, not well, or not reported), or adherence to restrictions (“strict” vs. all other categories). Due to the exploratory nature of this study, variables with p < 0.10 were retained in the final model. Since the PHQ + GAD distribution was not unimodal and symmetric, a non-parametric Wilcoxon test was utilized to confirm if variables from the final ANOVA model remained significant. The Wilcoxon test allows for only one variable to be tested in a model. A logistic regression model was used to test if the same variables described above predicted the binary outcomes of the subset of individual PHQ-9 or GAD-7 questions when more than 33% answered either yes (I experienced this outcome several days, more than half the days, or nearly every day) or no (not at all). Similarly, variables with p < 0.10 were retained in the final model.

Results

Cohort demographics

A total of 679 individuals were invited to participate in the study, and 109 individuals enrolled (16%). Of those, 79 individuals completed the study questionnaire (72%). Of the individuals who completed the questionnaire, 72% were male and 28% were female, which is consistent with the known increased prevalence of TAAD among male patients. Eight percent of individuals had undergone genetic testing at the time of enrollment with 83% having been identified to have at least one variant of uncertain significance (VUS) identified and 17% having had negative genetic testing. Seveteen percent also had a diagnosis of bicuspid aortic valve. Ninety-five percent of individuals who completed the survey were identified as non-Hispanic Caucasian, 1% identified as Latino or Hispanic, 1% identified as Native American or Alaskan Native, 1% identified as Asian, and 1% chose not to report their race/ethnicity. The age of individuals at time of enrollment ranged from 15 to 87, with a mean age of 58 years (standard deviation (SD) = 16, median = 62, interquartile range (IQR) = 19). When grouped by age, 11% were ≤ 35 years old, 47% were between 35 and 65 years old, and 42% were ≥ 65 years old. The age at diagnosis of TAAD ranged from birth to 82 years old with a mean age of 51 (SD = 19, median = 19, IQR = 18). The length of time since diagnosis ranged from 0 to 69 years, with a mean of 7 years (SD = 10, median = 3, IQR = 4). The majority of participants (80%) received the diagnosis in the previous 5 years. Narrowing the time frame resulted in 34% living with a diagnosis for ≤ 2 years with the remainder of the sample living with a diagnosis for > 2 years (66%). Nineteen percent of participants reported having a diagnosis of mental illness such as depression or anxiety prior to TAAD diagnosis, while 81% reported no mental illness prior to TAAD. Ten percent of participants reported being diagnosed with a mental illness such as depression or anxiety since their TAAD diagnosis, while 90% reported no mental illness diagnosis since TAAD. These data are summarized in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Participant demographics

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 57 (72) |

| Female | 22 (28) |

| Race(s)/ethnicity(ies) | |

| Non-Hispanic Caucasian | 75 (95) |

| Latino or Hispanic | 1 (1) |

| Native American or Alaskan Native | 1 (1) |

| Asian | 1 (1) |

| No answer provided | 1 (1) |

| Age at time of enrollment | |

| ≤ 35 years old | 9 (11) |

| Between 35–65 years old | 37 (47) |

| ≥ 65 years old | 33 (42) |

| Time living with diagnosis | |

| ≤ 2 years | 36 (34) |

| > 2 years | 51 (66) |

| Mental illness prior to TAAD diagnosis | |

| Yes | 15 (19) |

| No | 64 (81) |

| Mental illness since TAAD diagnosis | |

| Yes | 8 (10) |

| No | 71 (90) |

TAAD thoracic aortic aneurysm/dissection

Table 2.

Ages of participants at time of diagnosis and time study of enrollment

| Range | Mean | Standard deviation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis (years) | 0–82 | 51 | 19 |

| Age at time of enrollment (years) | 15–87 | 58 | 16 |

| Length of time since diagnosis (years) | 0–69 | 7 | 10 |

Quantitative results

Demographics

There was no association between gender and the following variables: adherence to activity restriction, the importance of physical activity, onset of a mental illness since TAAD diagnosis, or experiencing a financial effect due to TAAD (all p > 0.10). In addition, there were no associations between any of the TAAD-related variables themselves: adherence to activity restriction, the importance of physical activity, onset of mental illness since TAAD diagnosis, or experiencing a financial effect due to TAAD (all p > 0.31). There was no difference in age or length of time since diagnosis by gender (p > 0.25). There was, however, an association of gender and the categorical variable of time living with a diagnosis. While the majority of individuals living with a TAAD diagnosis for ≤ 2 years were male (88%), very few females had been recently diagnosed (12%, X2(1) = 4.9, p = 0.03). Therefore, gender and length of time with a diagnosis were tested separately and included in the final model if p < 0.10. Although there was a modest association of time living with the diagnosis and the age group (X(2) = 4.8, p = 0.09), this was primarily due to no individuals living with the diagnosis for less than 2 years and being in the youngest age category.

Depression and anxiety

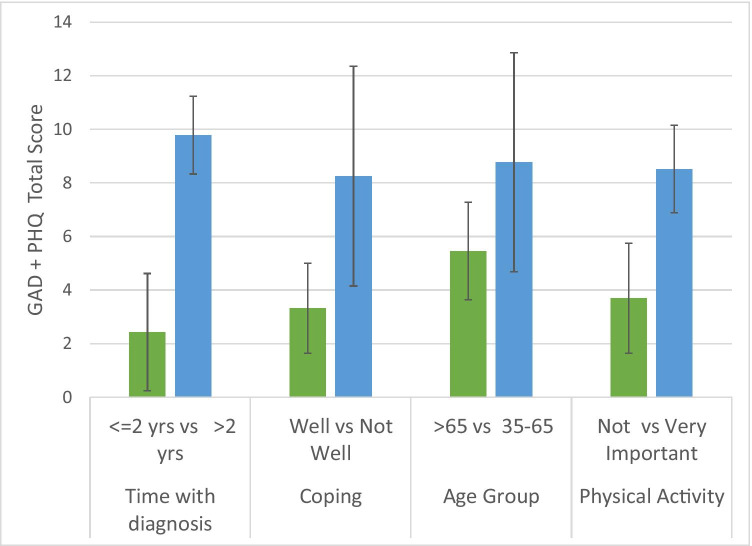

The initial ANOVA to examine which factors were associated with PHQ + GAD total score included all variables tested in one model; therefore, no Bonferroni correction was applied. This revealed that male participants and those who experienced a financial effect due to their diagnosis reported higher anxiety and depression scores (both p < 0.04). However, these variables were not significant predictors of the PHQ + GAD total score after accounting for the remaining variables (both p > 0.13). The final model indicated that individuals living with a diagnosis for a longer period of time (> 2 years, F(1,75) = 13.79, p = 0.0004; Wilcoxon p = 0.0045), individuals between the 35 and 65 age range (F(2,75) = 3.08, p = 0.05; Wilcoxon p = 0.0008), those who reported that physical activity was “very important” (compared to everyone else F(1,75) = 4.39, p = 0.04; Wilcoxon p = 0.089), and individuals who self-reported that they were not coping well (F(3,75) = 3.15, p = 0.03; Wilcoxon p = 0.0035) had high total scores. These results are summarized in Fig. 1. There was no significant association of any other variables with the PHQ + GAD total score (all p > 0.14).

Fig. 1.

Factors associated with combined PHQ + GAD score

Secondary analyses revealed variability in the yes versus no responses (i.e., at least 33% did or did not experience the outcome) for two PHQ-9 and three GAD-7 questions, resulting in a Bonferroni-adjusted alpha of 0.01. These findings are summarized in Table 3. Individuals who experienced a financial effect due to their diagnosis of TAAD were marginally more likely to have “trouble falling or staying asleep, or sleeping too much,” (p = 0.09). Participants who answered they “felt tired or had little energy” were more likely to be in the 35–65-year-old range (p = 0.002), or more recently diagnosed (p = 0.009). Individuals who “felt nervous, anxious, or on edge” were again between 35 and 65 years of age (p = 0.0072), with non-significant effects for being male (p = 0.045), or experiencing a financial effect due to their diagnosis and activity restrictions (p = 0.094). The younger age group reported “worrying too much about different things” (≤ 35 years old, p = 0.022) more often than individuals over the age of 65, as did those who felt physical activity was “very important” (p = 0.031). Participants who reported that they were “extremely active” prior to their diagnosis were surprisingly less likely to worry (p = 0.009). Individuals who responded that they became “easily annoyed or irritable” were most likely to have been recently diagnosed (p = 0.041) and middle aged (age 35–65 years, p = 0.030).

Table 3.

Variables associated with individual PHQ-9 and GAD-7 questions

| Survey: | Question: | Question: | % yes: | Variable: | p-value: | OR: | Lower CI-upper CI: |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PHQ-9 | 3 | Trouble falling or staying asleep, or sleeping too much | 58 | Financial effect (yes versus no) | 0.095 | 4.0 | 0.7–20.8 |

| PHQ-9 | 4 | Feeling tired or having little energy | 57 | 35 < age < 65 versus ≥ 65 years | 0.0021 | 8.2 | 2.5–26.6 |

| PHQ-9 | 4 | Feeling tired or having little energy | ≤ 2 years versus > 2 year since diagnosis | 0.0089 | 5.0 | 1.5–16.6 | |

| GAD-7 | 1 | Feeling nervous, anxious, or on edge | 40 | Financial effect (yes versus no) | 0.094 | 3.5 | 0.8–15.6 |

| GAD-7 | 1 | Feeling nervous, anxious, or on edge | 35 < age < 65 versus ≥ 65 years old | 0.0072 | 5.5 | 1.6–18.4 | |

| GAD-7 | 1 | Feeling nervous, anxious, or on edge | Gender (male versus female) | 0.058 | 3.1 | 0.9–10.1 | |

| GAD-7 | 3 | Worrying too much about different things | 39 | ≤ 35 years old versus ≥ 65 years old | 0.045 | 6.2 | 1.2–30.9 |

| GAD-7 | 3 | Worrying too much about different things | Physical activity: very important versus all others | 0.031 | 4.0 | 1.1–13.8 | |

| GAD-7 | 3 | Worrying too much about different things | Prior activity: extremely active versus all others | 0.009 | 0.2 | 0.05–0.7 | |

| GAD-7 | 6 | Becoming easily annoyed or irritable | 38 | 35 < age < 65 versus ≥ 65 years | 0.030 | 1.8 | 1.4–13.1 |

| GAD-7 | 6 | Becoming easily annoyed or irritable | ≤ 2 years versus > 2 year since diagnosis | 0.041 | 3.3 | 1.1–10.5 |

PHQ-9 patient health questionnaire-9; GAD-7 generalized anxiety disorder-7; OR odds ratio; CI 95% confidence interval

Qualitative data results

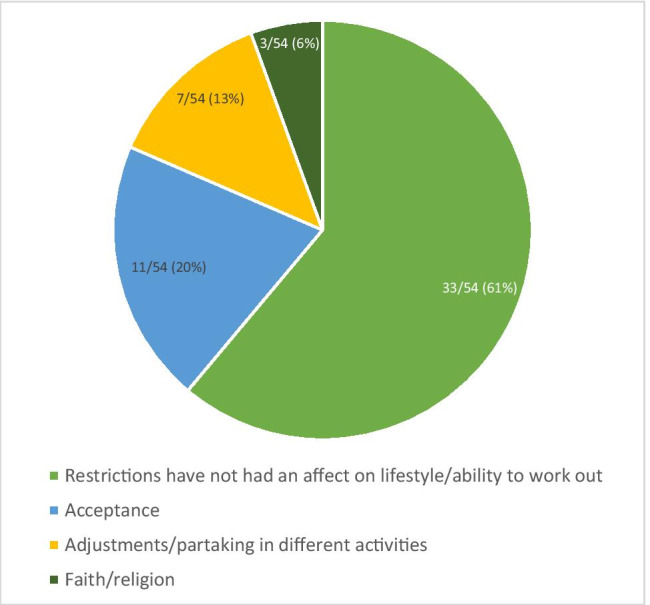

Perception of why physical activity restrictions have caused psychological distress

Participants expressed different reasons that restriction of physical activities caused psychological distress (N = 17). These findings are summarized in Fig. 2. Participants most often reported the change in their ability to work out and its impact on overall lifestyle as the largest factor influencing their level of distress (N = 9, 53%). These participants expressed feelings of isolation and concern regarding no longer being able to participate in the activities that they once enjoyed and that contributed in large part to their identity. These feelings contributed to their levels of psychological distress following activity restrictions.

“Especially in high school sports, it was difficult to explain why I couldn’t do weight training to my teammates. These restrictions made me feel abnormal or weaker.”

“I have been a runner since early 1983 and competed in high school cross country and road races. I was devastated when my cardiologist told me I couldn’t run. I miss running and the psychological release it provides. I also used to run on occasion with family and friends, and I can’t do that anymore.”

Fig. 2.

Perception of why physical activity restrictions have caused psychological distress

Other participants stated that their distress was heavily influenced by the psychological symptoms (N = 6, 35%) as well as the physical effects they experienced (N = 2, 12%).

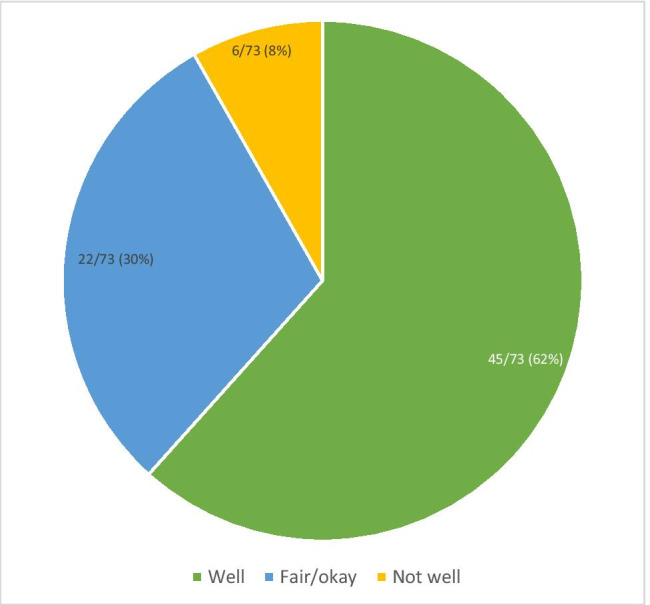

Perception of why physical activity restrictions have not caused psychological distress (S1).

Participants who reported that they did not experience psychological distress as a result of their physical activity restrictions were asked to expand on their beliefs of why they did not experience significant distress (total N = 54). Themes identified for this question included acceptance of the diagnosis and activity restrictions, ability to adjust and partake in different activities, and faith and religion (N = 11, 7, 3; 20%, 13%, 6% respectively). The majority of individuals who did not identify with feeling distress reported that it was due to the restrictions not having a significant impact on their lifestyle or ability to work out (N = 33, 61%). Thus, both groups identified this as the most significant factor despite having different psychological distress patterns. These findings are summarized in Fig. 3.

“I’m not really interested in weightlifting anymore anyways.”

“I hardly notice the activity restrictions.”

“I didn’t do much physical activity before.”

Fig. 3.

Perception of why physical activity restrictions have not caused psychological distress

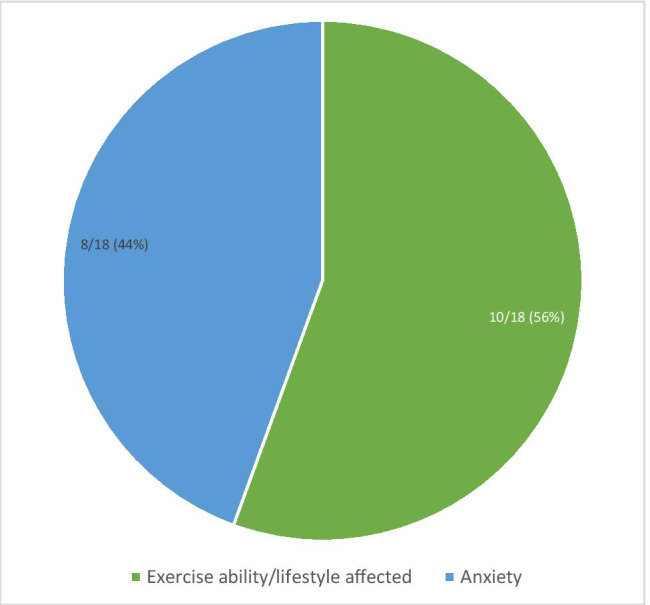

Perception of ability to cope with physical activity restrictions

When asked to describe their ability to cope with the physical activity restrictions (total N = 73), participant responses were categorized as well, fair/okay, and not well. The majority of participants reported their ability to cope as “well” (N = 45, 62%), while the rest of the participants reported their ability to cope as “fair/okay” (N = 22, 30%) or “not well” (N = 6, 8%). These data are summarized in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Perception of ability to cope with physical activity restrictions

Perceived factors hindering ability to cope with physical activity restrictions

Participants were asked to describe any factors that they felt hindered their ability to cope (total N = 18). While some participants reported anxiety was hindering their ability to cope (N = 8, 44%), the majority stated that this was related to lifestyle and exercise being affected (N = 10, 56%). These findings are summarized in Fig. 5. The importance of restrictions on lifestyle and ability to exercise is consistent with the findings described in Figs. 2 and 3.

“I would like to be able to exercise freely without thinking about it.”

“I haven’t been able to run like I used to. I used to run several times a week with my running buddy.”

Fig. 5.

Perceived factors hindering ability to cope with physical activity restrictions

Suggested resources for minimizing distress

In an attempt to identify resources that could be of potential use to non-syndromic TAAD patients, participants were asked to reflect on any resources that they believe could have been helpful to them in minimizing their psychological distress following their diagnosis of TAAD and associated activity restrictions (total N = 17). Themes such as psychological support (N = 11, 33%), ability to continue regular physical activity (N = 2, 6%), and a variety of other responses that were categorized as “other” (N = 3, 9%) emerged. The majority of responses were found to have an underlying theme of additional education and/or information (N = 17, 52%). These data are summarized in Fig. 6.

“Better information on safe, alternative activities would’ve been helpful so I didn’t feel like I just couldn’t do anything.”

“Knowing which activities are still OK.”

“One clear set of restrictions would be nice. I’m still not sure what I can and can’t lift.”

Fig. 6.

Suggested resources for minimizing distress

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the psychological impact of the physical activity restrictions due to a diagnosis of non-syndromic TAAD. While the physical symptoms and effects associated with TAAD are known and well-described within the medical literature, this study identified specific characteristics that may increase susceptibility to feelings of depression and/or anxiety.

Our results revealed that non-syndromic TAAD individuals with higher anxiety and depression also described physical activity as a very important component of their lifestyle and who had more difficulty coping with and adapting to the restrictions. Furthermore, the importance of physical activity was associated with feeling annoyed or irritated. Previous studies of cardiovascular patients similarly report that individuals engaging in physical activities prior to their diagnosis experienced difficulty adapting (Asif et al 2015; Luiten et al 2016). These findings suggest that it is critical to identify individuals who are likely to engage in physical acitivities, such as those involved in athletics or who work out daily, as they are more likely to experience greater distress. Earlier identification of these individuals could enable genetic counselors and other medical professionals involved in these patients’ management to better anticipate and provide the psychosocial support that is needed.

Our results indicated that individuals living for a longer period of time with the TAAD diagnosis, and those between the age of 35 and 65 years were more likely to report increased anxiety and depression, feeling tired or having no energy, and feeling easily annoyed or irritated. As more hereditary causes are identified and genetic testing becomes less costly, non-syndromic TAAD will become more prevalent in the clinical setting, which will likely lead to identification of at-risk or affected individuals earlier in life. The characteristics associated with a higher likelihood of depression and/or anxiety identified by this study will be crucial for genetic counselors to take into consideration during counseling sessions in an effort to address these concerns at the earliest possible time.

Individuals in this study who reported experiencing a negative financial effect as a result of their physical restrictions were more likely to have trouble sleeping or feel nervous or anxious. These results are important for gentic counselors to keep in mind, since financial impact can happen in a multitude of ways and affect individuals of all demographic backgrounds. For example, someone who earns their living and provides for their family through a manual labor job may be forced to leave their job, while a high school student who planned to attend college on an athletic scholarship may no longer have that option. While earlier identification of at-risk individuals could allow for earlier career plan modification, the diagnosis and physical activity restrictions also have the potential to cause psychological distress at a younger age. This is where genetic counselors and their specialized training could undoubtedly be beneficial by addressing psychological distress at an earlier stage. This could lead to earlier adaptation by the individual as well as provide the opportunity for earlier psychological support and intervention.

Although this study identified specific characteristics contributing to the psychological impact experienced by a subset of individuals with non-syndromic TAAD, the prospect of depression and anxiety is a potential reality with every genetic diagnosis. Therefore, the results of this study could be applicable when treating and providing support for patients in the cardiology and cardiovascular genetics settings where physical activity abilities can be affected by diagnoses and medical management. They should be considered in an attempt to improve standard clinical practice and create a more intentional, patient-centered counseling experience within the cardiovascular genetics setting.

Study limitations

Limitations of this study include a potential ascertainment bias for individuals who were previously active and therefore more impacted by their diagnosis and interested in participating as a result. This, in conjunction with the low response rate of 88%, could suggest that these results are not generalizable to the non-respondents or to individuals with TAAD in general. These results remain relevant, however, to individuals who engaged in physical activity prior to their diagnosis. We could not control for the fact that individuals who were managed by different physicians may have received varying guidelines regarding physical activity restrictions, resulting in the possibility of varying restrictions across participants. To be as inclusive as possible, we did not search patient records for aorta size or scoring of size. While the degree of dilation could impact the recommendation for activity restrictions, we conservatively included individuals who may not have had to restrict their physical activity. In addition, it is possible that aorta dimensions and other measuares could influence distress; however, our study specifically sought to address the TAAD diagnosis itself and its impact on distress/psychosocial adaptation.

While the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 questionnaires have been validated in previous research, they have not been validated specifically in this patient population, nor have they been validated to retroactively assess depression or anxiety. Furthermore, even if the questionnaires had been administered at the time of the diagnosis, activity restrictions would have been recommended at the same time. Thus, it would be difficult for patients to differentiate the source of depression and/or anxiety as being the diagnosis or the activity restrictions. However, some studies have verified that both the PHQ-9 and the GAD-7 accurately assess depression and anxiety after experiencing a condition such as a stroke (Williams et al. 2005) or brain injury (Donders and Darland 2017).

Although we could not control for the amount of time since diagnosis of TAAD, the time period for which participants retrospectively responded covered a range of 0–69 years, only five people received the diagnosis 20 or more years previously, with the majority of respondents receiving the diagnosis in the last 5 years. Thus, the retrospective nature of the responses was not a considerably long period of time for most participants. Participants were asked to recall the distress they experienced but substantial differences in amount of time since diagnosis between individuals could lead to discrepancies in terms of recollection or recall bias. However, we utilized the the length of time with a diagnosis to reveal important results that inform the field of genetic counseling. The PHQ-9, GAD-7, and various open-ended questions could be considered sensitive due to assessing the presence of depression, anxiety, and/or other mental illnesses, which could result in participants not being entirely honest with their responses. This sample consisted of a subset of individuals with TAAD who live in a specific geographical location, and therefore the results of this study may not be generalizable to the greater population of those with non-syndromic TAAD. Finally, the sample size was small, which resulted in reduced power to explore factors associated with individual PHQ/GAD questions, and impeded the ability to thoroughly explore any measure of severity of anxiety and/or depression. However, despite the small numbers, several results would survive a Bonferroni correction for both parametric and non-parametric tests, indicating a large effect size for several factors explored in this study.

Practice implications

Genetic counseling is a specialty that not only addresses the physical symptoms of genetic disease but also the psychological impact it can have on an individual in both the short- and long-term setting. Addressing the psychological implications of disease should continue to move toward the forefront of our practices to ensure a patient-focused approach and the most optimal patient outcomes. Risk counseling for exercise and physical activity will be most effective when tailored to each individual and provided by an aortopathic specialist. This could be expanded to involve a multidisciplinary approach involving guidance from sports cardiologist and sports medicine specialists who are familiar with aortopathies. A more global approach from the American Heart Association to create and distribute patient-centered information about TAAD, physical activity, and support resources would also provide a bridge for patients to identify personalized activity recommendations with their own healthcare providers.

This study identified specific aspects of which to be mindful for this patient population. Genetic counselors can utilize this information to implement practices that maximize the psychological and therapeutic benefits of genetic counseling for these individuals. Because genetic counselors are specifically and specially trained to address the distress incurred by patients as the result of genetic disease, they play an integral role in the healthcare team for cardiovascular patients and should continue to be included into standard medical practice in the cardiovascular setting.

Research recommendations

The results of this study should be confirmed by additional research utilizing patient populations from multiple institutions and/or centers across a wider geographical area. This would allow for a greater sample size, and results based on a more diverse patient population would allow for more specific recommendations that would be generalizable to the non-syndromic TAAD population as a whole. Future research could also control for degree of physical activity prior to diagnosis to determine if those who are physically active experience more anxiety or depression compared to those who are not active. Ideally, the amount of time between prescription of activity restrictions and completion of the questionnaire would be minimized to allow for the most accurate data regarding psychological distress experienced as a result of activity restrictions. Additionally, this study did not include a large number of younger patients. Individuals who are teenagers or young adults may report different experiences, specific distressors, or degrees of physical activity, or may have made different lifestyle choices to help them adjust to their restrictions.

Conclusions

We conclude that TAAD patients with specific characteristics are more susceptible to psychological distress following the prescription of activity restrictions. In particular, individuals living with a diagnosis for more than 2 years, were not coping well, were between 36 and 65 years old, or reported physical activity was important to them or critical to their job, may be more prone to feelings of depression and/or anxiety. We recommend that genetic counselors, as well as other healthcare professionals who interact with TAAD patients, recognize these considerations and take them into account when providing counseling to these individuals. Overall, this will allow for tailored therapeutic measures that can aid in an individual’s overall physical and psychological wellbeing.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Samantha Freeze, MS, LCGC, for her contributions to study conception and design. The authors would also like to acknowledge Eric Traub, MS, CGC, for the contributions he made to the study design. The completion of this work fulfilled a degree requirement for the first author.

Author contribution

Alexis McEntire, Benjamin M. Helm, Benjamin Landis, Lindsey Elmore, Theodore Wilson, and Stephanie M. Ware contributed to the acquisition and interpretation of data. Leah Wetherill provided data analysis and interpretation. All authors contributed to conception or design of the work, drafted and revised the work, provided final approval of the version to be published, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

This work was partially supported by the Indiana University Health—Indiana University School of Medicine Strategic Research Initiative and Physician Scientist Initiative (S.M.W.).

Data availability

This is not federally funded research; therefore, the data are not publicly accessible. Individuals may contact the corresponding author for access to data.

Code availbaility

Not applicable.

Declarations

Ethics approval

This study was approved by and carried out in accordance with the Indiana University Institutional Review Board (IRB# 1705458555). All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000 (5).

Consent to participate

All participants provided their informed consent prior to their inclusion in the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Asif IM Price D Fisher LA Zakrajsek RA Larsen LK Raabe JJ Bejar MP … Drezner JA (2015) Stages of psychological impact after diagnosis with serious or potentially lethal cardiac disease in young competitive athletes: a new model. J Electrocardiograph, 48, 298-310 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Black III, J.H., Greene, C.L., & Woo, J. (2018, Oct 29). Epidemiology, risk factors, pathogenesis, and natural history of thoracic aortic aneurysm. Retrieved from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/epidemiology-risk-factors-pathogenesis-and-natural-history-of-thoracic-aortic-aneurysm

- Braverman AC, Harris KM, Kovacs RJ, Maron BJ. Eligibility and disqualification recommendations for competitive athletes with cardiovascular abnormalities: task force 7: aortic diseases, including marfan syndrome. Circulation. 2015;132:e303–e309. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elefteriades JA, Farkas EA. Thoracic aortic aneurysm: clinical pertinent controversies and uncertainties. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:841–857. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.08.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donders J, Darland K. Psychometric properties and correlates of the PHQ-2 and PHQ-9 after traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj. 2017;31:1871–1875. doi: 10.1080/02699052.2017.1334962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap) – a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Wu J, Yu Z, Bair MJ, Kean J, Stump T, Monahan PO. The Patient Health Questionnaire Anxiety and Depression Scale (PHQ-ADS): initial validation in three clinical trials. Psychosom Med. 2016;78:716–727. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luiten RC, Ormond K, Post K, Asif IM, Wheeler MT, Caleshu C. Exercise restrictions trigger psychological difficulty in active and athletic adults with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Open Heart. 2016;3:1–7. doi: 10.1136/openhrt-2016-000488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maron BJ, Zipes DP, Kovacs RJ. Eligibility and disqualification recommendations for competitive athletes with cardiovascular abnormalities: preamble, principles, and general considerations. Circulation. 2015;132:e256–e261. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mausbach BT, Chattillion EA, Moore RC, Roepke SK, Depp CA, Roesch S. Activity restriction and depression in medical patients and their caregivers: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2011;31:900–908. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2011.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsson C, Franco-Cereceda A. Health-Related Quality of Life in Thoracic Aortic Disease. Aorta. 2013;1:153–161. doi: 10.12945/j.aorta.2013.13-028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resta R, Biesecker BB, Bennett R, Blum S, Hahn SE, Strecker MN, Williams JL. A new definition of genetic counseling: National Society of Genetic Counselors’ task force report. J Genet Couns. 2006;15:77–83. doi: 10.1007/s10897-005-9014-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Lowe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1092–1097. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaismoradi M, Turunen H, Bondas T. Content analysis and thematic analysis: implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nurs Health Sci. 2013;15:398–405. doi: 10.1111/nhs.12048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams LS, Brizendine EJ, Plue L, Bakas T, Tu W, Hugh H, Kroenke K. Performance of the PHQ-9 as a screening tool for depression after stroke. Stroke. 2005;36:635–638. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000155688.18207.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

This is not federally funded research; therefore, the data are not publicly accessible. Individuals may contact the corresponding author for access to data.

Not applicable.