Abstract

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a common chronic neurodegenerative disease induced by the death of dopaminergic neurons. Anthocyanins are naturally found antioxidants and well-known for their preventive effects in neurodegenerative disorders. Black carrots (Daucus carota L. ssp. sativus var. atrorubens Alef.) are a rich source of anthocyanins predominantly including acylated cyanidin-based derivatives making them more stable. However, there have been no reports analysing the neuroprotective role of black carrot anthocyanins (BCA) on PD. In order to investigate the potential neuroprotective effect of BCA, human SH-SY5Y cells were treated with MPP+ (1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium) to induce PD associated cell death and cytotoxicity. Anthocyanins were extracted from black carrots and the composition was determined by HPLC–DAD. SH-SY5Y cells were co-incubated with BCA (2.5, 5, 10, 25, 50, 100 µg/ml) and 0.5 mM MPP+ to determine the neuroprotective effect of BCA against MPP+ induced cell death and cytotoxicity. Results indicate that BCA concentrations did not have any adverse effect on cell viability. BCA revealed its cytoprotective effect, especially at higher concentrations (50, 100 µg/ml) by increasing metabolic activity and decreasing membrane damage. BCA exhibited antioxidant activity via scavenging MPP+ induced reactive oxygen species (ROS) and protecting dopaminergic neurons from ROS mediated apoptosis. These results suggest a neuroprotective effect of BCA due to its high antioxidant and antiapoptotic activity, along with the absence of cytotoxicity. The elevated stability of BCA together with potential neuroprotective effects may shed light to future studies in order to elucidate the mechanism and further neuro-therapeutic potential of BCA which is promising as a neuroprotective agent.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s10616-021-00500-4.

Keywords: Black carrot, Anthocyanins, SH-SY5Y, MPP+, Parkinson’s disease, Neuroprotective

Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is the second most common neurodegenerative disorder characterized by selective and progressive loss of dopaminergic neurons within the substantia nigra pars compacta (Ramalingam and Kim 2016; Shishido et al. 2019). While the etiology of dopaminergic neuronal loss remains elusive, several mechanisms are thought to be involved in the pathogenesis of the disease, such as abnormal protein aggregation linked to proteasomal impairments, mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress. The accumulation of all these correlated events are thought to be responsible for dopaminergic neurodegeneration by inducing apoptosis (Ramalingam and Kim 2016).

The 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium (MPP+) is an active metabolite of dopaminergic neurotoxin 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP). MPP+ inhibits tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) activity and selectively suppresses complex I of electron transport chain (ETC) in mitochondria. These events consequently lead to decreased ATP synthesis, excessive reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and ultimately cellular dysfunction and apoptotic cell death (Jiang et al. 2019). SH-SY5Y cells express dopamine transporter (DAT) which is mandatory for the entry of MPP+ to these specific dopaminergic cells. (Dagda et al. 2013). Therefore, MPP+ is widely applied to acutely model oxidative stress-induced in vitroPD model in combination with human dopaminergic SH-SY5Y cell line (Chen et al. 2018; Kim et al. 2010; Ramalingam and Kim 2016).

Owing to several biochemical and functional properties, the SH-SY5Y cells has been widely used to model dopaminergic neurons and study the mechanism of MPP+ mediated neurotoxicity (Ramalingam and Kim 2016; Xie et al. 2010). Initially, the SH-SY5Y cells express tyrosine and dopamine-β-hydroxylases and hence are able to synthesize dopamine (DA) and norepinephrine (NE). Moreover by the intake of MPP+ into SH-SY5Y cells via DAT, these cells imitate many features of the dopaminergic neuronal death and cytotoxicity detected in PD.

Anthocyanins are a group of polyphenolic flavonoids, responsible for the blue and purple colors of vegetables and fruits. They have recently gained a lot of attention because of their health benefits such as lowering the risk for diabetes, obesity, cancer, cardiovascular and neurodegenerative diseases. These essential benefits of anthocyanins have been attributed to their wide range of anti-oxidative, anti-inflammatory, anti-cancer, cardio- and neuroprotective activities (Li et al. 2017; Yousuf et al. 2016). Black carrots (Daucus carota L. ssp. sativus var. atrorubens Alef.) originating from Turkey are of prime importance as an anthocyanin source since they have very high anthocyanin content mainly consisting of acylated cyanidin-based anthocyanins which makes them more heat and pH stable than monomeric anthocyanins (Espinosa-Acosta et al. 2018; Sevimli-Gur et al. 2013; Tsutsumi et al. 2019). Studies have shown that daily intake of anthocyanins decrease the risk of neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and PD (Zhang et al. 2019). Supression of oxidative stress and neuroinflammation, prevention of apoptosis are some of the key mechanisms through which anthocyanins have been shown to protect neurons against toxicity (Gao et al. 2012; Winter and Bickford 2019; Zhang et al. 2019). The neuroprotective effects of anthocyanins are broadly studied. However, studies are generally about the monomeric cyanidin-3-O-glucoside (C3G) (Zhang et al. 2019) and little is known about the neuroprotective role of acylated black carrot anthocyanins (BCA) against PD.

The aim of the present study is to investigate the possible neuroprotective effect of BCA against MPP+ mediated dopaminergic neuronal cell death and cytotoxicity. In this quest, SH-SY5Y cells were used as an in vitro cell model of dopaminergic neurons for PD to study whether the treatment with BCA could alleviate the loss of cell viability and cytotoxicity, the generation of ROS and apoptosis induced by MPP+.

Materials and methods

Chemicals and reagents

For analytical assays, Folin-Ciocalteu’s phenol reagent, trolox, gallic acid, cyanidin-3-O-glucoside, and neocuproine were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Munich, Germany). Acetonitrile (HPLC grade, ≥ 99.9%), methanol (HPLC grade, ≥ 99.9%) and formic acid (98–100%) were purchased from IsoLab Chemicals (Wertheim, Germany). Unless noted, other analytical grade chemicals were purchased from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany).

For cell culture assays, DMEM/F-12, FBS, Trypsin/EDTA, primocin, cleaved caspase-3 ELISA kit and Annexin V Alexa Fluor 568 conjugate were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (MA, USA). 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) assay kits, DAPI, MPP+ neurotoxin were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Munich, Germany). Cellular ROS and PARP1 assay kits were purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, MA, USA).

Analytical assays

Extraction of anthocyanins from black carrot

Anthocyanin extraction was performed according to a method explained by Montilla et al. (Montilla et al. 2011). Black carrot (Daucus carota L. spp. sativus var. Atrorubens Alef.) slices was blanched at 100 °C with dH2O and an aqueous hydrochloric acid (19/1, v/v) solution was added. The suspension was cooled at 0 °C and then stored at room temperature (RT). In order to get rid of solid material, the suspension was filtered and then applied onto a conditioned D-101 resin column. The column was rinsed with dH2O to excess material and anthocyanins were eluted with ethanol. The eluate was concentrated under vacuum, dissolved in dH2O, freeze-dried and stored at − 80 °C for further use.

Analysis of anthocyanin components of black carrot extract by HPLC–DAD

Anthocyanins of the black carrot extract were characterized according to HPLC procedure described by Vagiri et al. with slight differences (Vagiri et al. 2012). A Shimadzu LC-20A HPLC system (Kyoto, Japan) consisted of a binary pump (LC-20AT), a UV–Vis photodiode-array detector (SPD-M20A), degasser (DGU-20A), and column oven (CTO-10AS) was used for characterization analyses of anthocyanins. Initially, black carrot extract was centrifuged, diluted and filtered before HPLC analyses. HPLC analyses were performed using a 5 μm Inertsil ODS-3 reversed-phase column (250 × 4.6 mm; GL Sciences). Injection volume of samples in HPLC–DAD was 20 μl. The separation was carried out with a mobile phase consisting of solvent A (water/formic acid, 93/7) and solvent B (acetonitrile/water/methanol, 90/5/5) under the gradient condition at 1.2 ml/min. The column was maintained at 25 °C. The chromatograms were recorded at 520 nm for anthocyanin. All mobile phases were filtered and degassed in the ultrasonic bath. Gradient elution was followed as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Gradient elution time and percentage of solvent B

| Time (min) | B% |

|---|---|

| 0 | 8 |

| 2 | 8 |

| 21.25 | 16 |

| 30 | 18 |

| 35 | 8 |

Total phenolic and anthocyanin contents

The total phenolic content (TPC) of the black carrot extract was calculated by the Folin-Ciocalteu assay with slight modifications (Rababah et al. 2011; Song et al. 2010). Initially, black carrot extract was mixed with 10% of Folin-Ciocalteu reagent. Then, 7.5% (w/v) sodium carbonate (Na2CO3) was added and the mixture was incubated in the dark for 60 min at RT. Absorbance was measured at 765 nm using a spectrophotometer (Shimadzu UV-1800). All analyses were performed in triplicate. Gallic acid was used as a reference standard with a concentration range of 0–250 µg/ml. The results were expressed as milligrams of gallic acid equivalent (mg GAE/g) of the sample.

The total anthocyanin content (TAC) was determined initially by monitoring HPLC chromatogram of C3G standard (Sigma, cat no: 52976) at 520 nm. Then, the calibration curve of C3G was plotted for the concentration range of 1–100 µg/ml. Anthocyanin peaks extracted from black carrot expressed at 520 nm in HPLC chromatogram were quantified using a C3G calibration curve and the results were indicated as milligrams of C3G equivalent (mg C3GE/g) of the sample. The LCsolution software (Ver.2.32 or later, Shimadzu) was used to analyze the data. All analyses were performed in triplicate. the peak areas.

Total antioxidant capacity assay (TEAC)

The CUPRAC (Cupric Ion Reducing Antioxidant Capacity) assay was applied to determine the radical scavenging ability of the black carrot extract due to the protocol described by Apak et al. (2008, 2006). Briefly, 1 ml 10−2 M Cu2+ (CuCl2) + 1 ml 7.5 × 10−3 M neocuproine + 1 ml 1 M NH4Ac were mixed. Antioxidant sample (or standard) and H2O were added to the initial solution and incubated for 30 min at RT before measuring the absorbance at 450 nm using a spectrophotometer (Shimadzu UV-1800). Trolox was used as a reference standard with a concentration range of 10–100 µmol/l (Apak et al. 2008, 2006).

In vitro assays

SH-SY5Y cell culture

SH-SY5Y cells (ATCC Number: CRL-2266, Lot Number: 64035832) were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC Distributor: LGC Standards, Wessel, Germany) company, thawed, subcultured and stored at liquid nitrogen for further use. Passage 5–20 cells were detached with 0.25% Trypsin/EDTA solution upon 70% confluency and seeded at a density of 4 × 104 cells/cm2 into a new 25 cm2 culture flask including DMEM:F-12 medium with 10% FBS and 0.1 mg/ml primocin, incubated at 37 ºC, 5% CO2 incubator. Medium was changed every 48 h, and the cells were passaged every 5 days.

Real-time cell analysis

The real-time cell analyzer (RTCA; xCELLigence, Roche) which allows for dynamic cell proliferation and cytotoxicity based upon impedance measurements was used to determine the median lethal dose (LD50) of MPP+ for dopaminergic neurons. The MPP+ was dissolved in DMEM:F12 medium, and further diluted to 0.5 mM (mmol/l) by the complete culture medium. SH-SY5Y cells were seeded on E-plates at a density of 2 × 104 cells/well and incubated in 37 °C, 5% CO2 incubator. Cells were then treated with different concentrations (0.1, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1, 1.5, 2 mM) of MPP+ for 24 h. The measured impedance was calculated and plotted by RTCA system as cell index which is proportional to cell number, morphology and adhesion. Cell index values were recorded in every 15 min for 24 h.

Secondly, SH-SY5Y cells were treated with extracted BCA to determine whether there is anthocyanin concentration dependent cytotoxicity. BCA was dissolved in culture medium and further diluted to final concentrations (2.5, 5, 10, 25, 50, 100 µg/ml). BCA was freshly prepared in each experiment.

Finally, to evaluate the possible neuroprotective effect of different concentrations of BCA, SH-SY5Y cells were treated with 0.5 mM MPP+ alone or co-incubated with MPP+ and various concentrations (2.5, 5, 10, 25, 50, 100 µg/ml) of BCA for 24 h.

Cell viability and cytotoxicity assays

In order to determine cell viability and cytotoxicity, colorimetric 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) assays were carried out. For all experiments, SH-SY5Y cells were treated with MPP+ and indicated concentrations of BCA simultaneously for 24 h and were compared with untreated (control) and MPP+ treated cells.

Viability assay (MTT)

MTT is used to assess cell viability by determining mitochondrial activity of living cells according to their ability to reduce the tetrazolium salt MTT (yellow), into formazan crystals (dark blue). SH-SY5Y cells were seeded on 96-well plates at a density of 2 × 104 cells/well and treated with MPP+ and BCA as noted above. Cells were incubated with MTT solution, then solubilization solution was added to solubilize formazan crystals and incubated overnight. Absorbance was measured at 570 nm using the microplate reader (Synergy H1, Biotek).

Cytotoxicity assay (LDH)

LDH, an oxidoreductase enzyme which catalyses the conversion of lactate in the presence of NAD to pyruvate and NADH, is released after cell damage and used to evaluate the presence of cytotoxicity. SH-SY5Y cells were seeded on 96-well plates at a density of 2 × 104 cells/well and treated with MPP+ and BCA as noted above. Cell culture medium samples and assay controls were prepared according to manufacturer’s instructions. A standard curve was plotted using NADH standards. After NADH-dependent a couple of reactions, formazan was detected by measuring absorbance at 450 nm using the microplate reader (Synergy H1, Biotek).

ROS analysis

Intracellular ROS was determined by Cellular ROS Assay Kit (abcam) which depends on the generation of red fluorescence of cell permeable dye in the presence of ROS. The generation of ROS and the potential protective role of BCA was monitored after the cells were co-treated with MPP+ and BCA. Cells were treated with ROS fluorescent probe for 1 h at 37 °C and counterstained with DAPI. Images were analyzed under fluorescent microscopy (Leica) and the fluorescence intensity was measured at λex: 650/λem: 675 nm using the microplate reader (Synergy H1, Biotek).

Annexin V apoptosis assay

Detection of apoptotic cells based on MPP+ and BCA treatment was performed using Annexin V Alexa Fluor 568 (Thermo) conjugate. Annexin V, a Ca2+-dependent phospholipid-binding protein, has high affinity for phosphatidylserine (PS) which translocates from the inner side of the apoptotic cell membrane to the outer side. SH-SY5Y cells were seeded on 96-well plates at a density of 2 × 104 cells/well and treated with MPP+ and BCA as mentioned earlier. Annexin V Alexa 568 labeling solution was prepared and applied according to manufacturer’s instructions and cells were counterstained with DAPI. Then, cells were analyzed under fluorescence microscopy (Leica) and fluorescent intensity relative to control cells was quantified using ImageJ software (ImageJ 1.50i, NIH, MD, USA).

Cleaved caspase-3 and poly ADP ribose polymerase 1 (PARP1) assay

Cleaved caspase-3 and PARP1 levels were measured using colorimetric human ELISA kits. SH-SY5Y cells were seeded on 96-well plates at a density of 2 × 104 cells/well and treated with MPP+ and BCA as mentioned above. The human cleaved PARP1 ELISA kit (Abcam) and human cleaved caspase-3 ELISA kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) were used based on the instractions of the manufacturer. Absorbance of cleaved caspase-3 and PARP1 were measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader (Synergy H1, Biotek).

Statistical analysis

Results are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) of three different replicate experiments, each carried out in triplicate. The paired t-test was performed to assess the differences between the samples. Differences were regarded as statistically significant at *p < 0.01 and **p < 0.001.

Results

Anthocyanin profile of black carrot extract

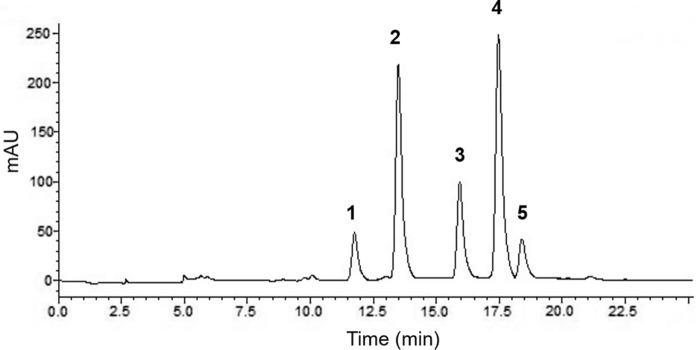

The HPLC–DAD chromatogram of C3G standard was monitored at 520 nm (Supplementary Fig. 1a) and a calibration curve was demonstrated (Supplementary Fig. 1b). The HPLC–DAD chromatogram (520 nm) of anthocyanins extracted from the black carrot is shown in Fig. 1 and the chromatographic characteristics of seperated compounds and quantities are present in Table 2. Relative percentages and concentrations of anthocyanin compounds were calculated from the peak areas plotted on the calibration curve and demonstrated as C3G equivalent. Identification of anthocyanins was carried out based on UV–visible spectra and retention times and the anthocyanin profile is consistent with previosly reported HPLC chromatogram data recorded at 520 nm from black carrot (Daucus carota L. ssp. sativus var. atrorubens Alef.) (Algarra et al. 2014; Barba-Espin et al. 2017; Montilla et al. 2011; Netzel et al. 2007).

Fig. 1.

HPLC chromatogram of anthocyanins from black carrot extract acquired at 520 nm detection. Peak numbers referred to compounds showed in Table 1

Table 2.

Anthocyanin compounds and relative proportions identified in black carrot extract

| Peak no | RT (min) | Compound identity | mg C3GE**/g | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 11.55 | Cyanidin 3-xylosyl(glucosyl)galactoside | 11.60 ± 2.9 | 7.25 |

| 2 | 13.40 | Cyanidin 3-xylosylgalactoside | 52 ± 1.5 | 32.50 |

| 3 | 15.75 | Cyanidin 3-xylosyl(sinapoylglucosyl)galactoside | 23.20 ± 3.7 | 14.50 |

| 4 | 17.30 | Cyanidin 3-xylosyl(feruloylglucosyl)galactoside | 62.54 ± 7.8 | 39.09 |

| 5 | 18.25 | Cyanidin 3-xylosyl(coumaroylglucosyl)galactoside | 10.65 ± 4.1 | 6.66 |

RT retention time

**The results were expressed as cyanidin 3-O-glucoside equivalent

Black carrot included 5 anthocyanins with the major peaks 4, 2, 3 consisting Cyanidin 3-xylosyl(feruloylglucosyl)galactoside, Cyanidin 3-xylosylgalactoside, Cyanidin 3-xylosyl(sinapoylglucosyl)galactoside, respectively (Fig. 1; Table 2.). The anthocyanin composition of black carrot consists mainly of acylated (60.25%) and non-acylated (39.75%) derivatives. The major anthocyanins detected are cyanidin-based non-acylated (peak 1 and 2), or cyanidin 3-xylosyl(glucosyl)galactosides acylated with ferulic acid (peak 4), sinapic acid (peak 3), and coumaric acid (peak 5). Peaks 4 and 2 represented about 39.09% and 32.50% of the total area at 520 nm and were identified as cyanidin 3-xylosyl(feruloylglucosyl)galactoside and cyanidin 3-xylosylgalactoside, respectively. The minor compund was peak 5 as cyanidin 3-xylosyl(coumaroylglucosyl)galactoside (Table 2).

Total phenolic compound and antioxidant capacity of BCA

Total phenolic content was determined by the Folin-Ciocalteu method as gallic acid equivalents (GAE) and total anthocyanin content was determined by the HPLC chromatogram as C3G equivalent (C3GE). In order to assess the antioxidant and free radical scavenging properties, CUPRAC antioxidant assay was carried out and the results were given as trolox equivalent (TRE) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Total phenolic, anthocyanin content and antioxidant capacity of black carrot extract

| Sample | Phytochemicals | Antioxidant capacity | |

|---|---|---|---|

| TPC mg GAE*/g |

TAC mg C3GE**/g |

TEAC µmol TRE***/g |

|

| Black Carrot Extract | 457 ± 12.5 | 160 ± 4.8 | 4044 ± 29.2 |

Data are presented as the mean ± SD of three replicates

TPC: total phenolic content, TAC: total anthocyanin content, TEAC: Trolox equivalent anthocyanin capacity

*GAE is gallic acid equivalent

**C3GE is cyanidin 3-O-glucoside equivalent

***TRE is trolox equivalent

Isolation and purification of anthocyanins from black carrot was done by macroporous D101 resin to eliminate impurities and obtain highly purified BCA. The aim was to evaluate the total phenolic and anthocyanin content and antioxidant capacity of the purified anthocyanin rich black carrot extract used in the study therefore calculations were done from dry weight. Total phenolic content was 457 ± 12.5 mg GAE/g and total anthocyanin content was 160 ± 4.8 mg C3GE/g. According to the CUPRAC results, antioxidant capacity of BCA was 4044 ± 29.2 TEAC µmol TRE/g (Table 3) which was already expected due to the purification process and considerably high levels of total phenolics present in the black carrot extracts mainly consisting of acylated types which have been reported to have elevated total antioxidant capacity (Algarra et al. 2014).

BCA inhibits antiproliferative effect of MPP+ and shows a neuroprotective effect on MPP+ induced neurotoxicity

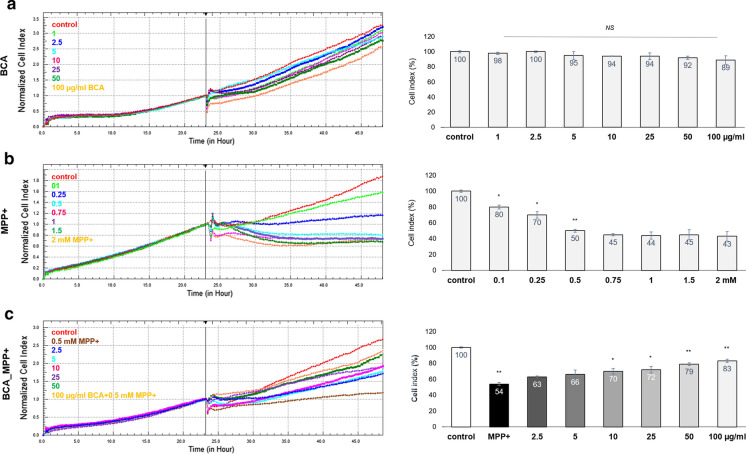

Potential protective effect of BCA on SH-SY5Y cells against MPP+ induced neurotoxicity was investigated by an impedance based system (Xcelligence-RTCA Roche). Live cell proliferation was continuously monitored and presented as a line graph indicating cell index vs time by the Xcelligence system software.

Initially, RTCA system was used to determine whether treatment of SH-SY5Y cells with BCA could result in any cytotoxicity. Each group of cells continued to proliferate and showed a similar pattern as control cells (Fig. 2a). Compared to control group, increasing anthocyanin concentration up to 100 µg/ml did not alter cell viability significantly. Therefore, specified concentrations were used safely in further experiments.

Fig. 2.

Determination of anti-proliferative effects of MPP+ and BCA on SH-SY5Y cells by Xcelligence RTCA. Line graphs of the Xcelligence RTCA software were reorganized to bar graphs representing the percentage of cell index normalized to each control group. a SH-SY5Y cells were treated with increasing concentrations of BCA, 2.5, 5, 10, 25, 50, 100 µg/ml, to evaluate BCA based cytotoxicity. b To asses the anti-proliferative effect and median lethal dose (LD50) of MPP+ for SH-SY5Y, cells were exposed to 0.1, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1, 1.5 and 2 mM MPP+ for 24 h. c Neuroprotective role of BCA is detected by treating cells with 0.5 mM MPP+ alone or with 2.5, 5, 10, 25, 50, 100 µg/ml BCA and 0.5 mM MPP+ simultaneously for 24 h. Error bars represent the standard deviation of the mean. *p < 0.01, **p < 0.001, NS non-significant

In order to assess the LD50 of MPP+ for SH-SY5Y cells, increasing concentrations from 0.1 to 2 mM MPP+ was applied to cells. Live cell proliferation was measured for 24 h using RTCA system. Our data showed that MPP+ elicit toxic effects upon its administration on SH-SY5Y cells. 0.1 mM MPP+ caused 20 ± 2.5% and 0.25 mM MPP+ 30 ± 4.1% cell death, respectively (p < 0.01; Fig. 2b). Our RTCA results showed that LD50 of MPP+ for SH-SY5Y cells were 0.5 mM. Increasing MPP+ concentration to 0.75 or to 1 mM barely changed cell viability with approximately 5 ± 0.7% decreased cell index. Therefore, 0.5 mM MPP+ was used to induce cell death in all experiments throughout the study.

SH-SY5Y cells were co-treated with indicated concentrations (2.5, 5, 10, 25, 50, 100 µg/ml) of BCA and 0.5 mM MPP+ simultaneously for 24 h to detect the possible neuroprotective effects of BCA. BCA protected the cells from MMP+’s proliferation inhibitory effect in a concentration dependent manner. 50 and 100 µg/ml BCA showed 25 ± 2.3% and 29 ± 3.1% protective activity against MPP+ induced cell death, respectively (p < 0.001). BCA at higher concentrations (50 and 100 µg/ml) significantly reversed antiproliferative effect of MPP+ and showed increased neuroprotective effect than lower concentrations (Fig. 2c). Taken together, our results suggest that BCA possesses neuroprotective activity against MPP+ induced cell death through inhibiting antiproliferative effect of MPP+.

BCA treatment alleviated cytotoxicity and increased cell viability in MPP+ induced SH-SY5Y cells

To elucidate the cytoprotective effects of BCA, SH-SY5Y cells were co-treated with indicated concentrations of BCA (2.5, 5, 10, 25, 50, 100 µg/ml) and 0.5 mM MPP+ for 24 h. Cell viability and cytotoxicity was determined using MTT and LDH assays, respectively. Furthermore, morphology of control, MPP+ treated, BCA and MPP+ co-treated SH-SY5Y cells were observed under a phase contrast microscope, to determine potential morphological changes of the cells. Our MTT assay results showed that 0.5 mM MPP+ alone reduced the viability of cells to 52 ± 2.9% compared to control group (p < 0.001; Fig. 3a). BCA co-treatment enhanced the viability of the cells starting from 58 ± 4.3% (2.5 µg/ml) up to 83 ± 3.3% (100 µg/ml) (p < 0.001). The results of LDH release assay, proportional to the cytotoxicity, confirmed MTT assay results demonstrating that 0.5 mM MPP+ alone showed the highest LDH release with 50 ± 3.2% of the cells having irreversible membrane damage (p < 0.001; Fig. 3a). Cytotoxicity decreased with increasing BCA concentrations and in particularly reaching its lowest point to 8 ± 2.1% upon 100 µg/ml BCA treatment (p < 0.001). Above all, 50 and 100 µg/ml BCA treatment significantly rescued the cell viability from 52 ± 2.9% to 78 ± 1.2% and 83 ± 3.3%; also diminished cytotoxicity from 50% ± 3.2 to 17 ± 2.7% and 8 ± 2.1%, respectively (p < 0.001; Fig. 3a).

Fig. 3.

Evaluation of cell viability and cytotoxicity of SH-SY5Y cells treated with MPP+ and BCA. SH-SY5Y cells were treated with 0.5 mM MPP+ alone or co-treated with 2.5, 5, 10, 25, 50, 100 µg/ml BCA and 0.5 mM MPP+ simultaneously for 24 h. a Quantitative analysis of cell viability and cytotoxicity was assed by MTT and LDH assay kits and absorbance was measured at 570 and 450 nm, respectively. Data were normalized to control group of each experiment and presented as the percentage of control. Error bars represent the standard deviation of the mean. **p < 0.001. b Representative cell morphology and viability was detected using a phase-contrast microscope at 10X magnification. Arrows indicate collapsed cells

To confirm the protective effects of BCA on cell morphology, SH-SY5Y cells were observed under phase-contrast microscope 24 h after induction with MPP+. Cells in the control group displayed typical characteristics of normal SH-SY5Y cell morphology (Fig. 3b). MPP+ induction for 24 h led to severe cell death and remaining cells had a collapsed morphology. Higher BCA concentrations, especially 50 and 100 µg/ml, rescued the attached cells and prevented cell shrinkage (Fig. 3b).

These data demonstrate that, in consistent with the viability graph and cellular morphology, BCA treatment revealed its cytoprotective role by increasing cell viability and decreasing membrane damage of cells upon MPP+ exposure, in a dose dependent manner.

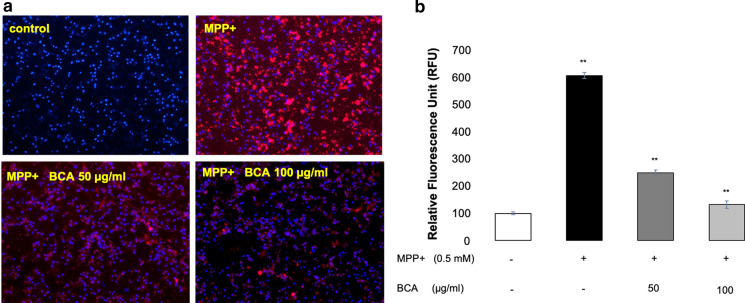

BCA reduced MPP+ induced intracellular ROS production

To investigate the antioxidant activity of BCA against MPP+ induced ROS generation, SH-SY5Y cells were co-treated with the highest concentrations of BCA (50, 100 µg/ml) and 0.5 mM MPP+ for 24 h and intracellular ROS levels were measured. Figure 4 demonstrates relative fluorescence unit (RFU) for each group, directly proportional to the amount of ROS present, normalized to control group. As expected, MPP+ exposure induced considerably high levels of ROS (608 ± 10.6 RFU), nearly six fold greater than control group (100 ± 5.2 RFU) (p < 0.001; Fig. 4b). 50 and 100 µg/ml BCA treatment were able to protect the cells against MPP+ induced ROS production in a concentration dependent manner demonstrating 250 ± 9.8 and 132 ± 13.6 RFU (p < 0.001; Fig. 4b) respectively, suggesting a direct proportion with BCA concentration and antioxidant activity. We postulate that BCA exhibited antioxidant activity by protecting SH-SY5Y cells from oxidative stress through limiting ROS generation.

Fig. 4.

Antioxidant effects of BCA on intracellular ROS generation of SH-SY5Y cells induced with MPP+. Inhibition of intracellular ROS accumulation by BCA was quantified after co-incubation of cells with 0.5 mM MPP+, 50 and 100 μg/ml BCA. a Fluorescent images were captured by a fluorescence microscope at 10X magnification and b fluorescence intensity proportional to the amount of ROS present, was measured by a fluorescent microplate reader. Error bars represent the standard deviation of the mean. **p < 0.001

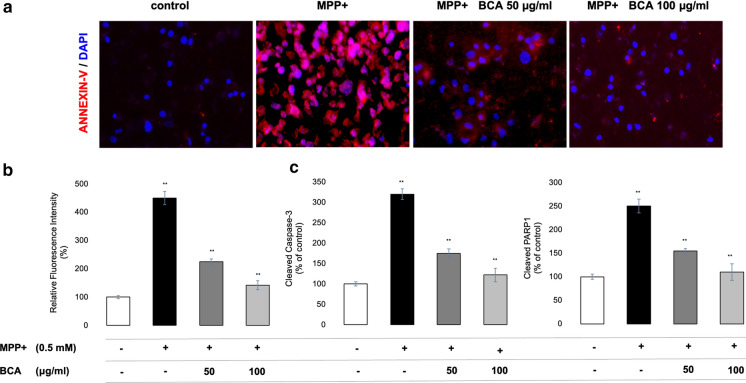

BCA prevented apoptosis in MPP+-induced SH-SY5Y cells

In order to evaluate the neuroprotective effects of BCA from MPP+ induced apoptosis, SH-SY5Y cells were stained with Annexin V after co-incubation of the cells with BCA (50, 100 µg/ml) and 0.5 mM MPP+ for 24 h (Fig. 5). Fluorescent intensity was quantified from at least 10 different Annexin V stained images from each group using imageJ software (Fig. 5b). Furthermore, cleaved caspase-3 and PARP1 levels of each group were quantified to confirm the neuroprotective potential of BCA.

Fig. 5.

Neuroprotective effects of BCA on MPP+ induced SH-SY5Y apoptosis. Antiapoptotic effects of BCA was quantified after co-treatment of cells with 0.5 mM MPP+ and 50, 100 μg/ml BCA. a Fluorescent images were captured by a fluorescence microscope at 20X magnification and b fluorescence intensity relative to control, proportional to the percentage of apoptotic cell death, was determined by ImageJ software. c Cleaved caspase-3 and PARP1 levels were measured by ELISA. Error bars represent the standard deviation of the mean. **p < 0.001

In early stages of apoptosis, phosphatidylserine translocates from the inner layer of the plasma membrane to the outer layer. Annexiv V protein has a high affinity to phosphatidylserine and therefore suitable to detect early apoptotic cells. As indicated in Fig. 5, MPP+ treatment led to apoptotic death (both early and late) of dopaminergic neurons 4.5 ± 0.5 fold greater relative to control cells (p < 0.001; Fig. 5b). Fluorescence intensity decreased to almost half of the MPP+ induced cells from 450 ± 10.4% to 225 ± 5.7% (p < 0.001) demonstrating the protective effect of 50 μg/ml BCA treatment against MPP+ . Moreover, 100 μg/ml BCA treatment significantly protected cells from both early and late apoptosis showing a significant decrease 3,1 ± 0.8 folds (p < 0.001) of that in MPP+ induced group.

During apoptosis, cleavage of PARP1 by activated caspase-3 ultimately leads to neuronal cell death. Thus, activated caspase-3 and cleaved-PARP1 are considered to be two important pathological hallmarks of apoptosis. In accordance with previous results, treatment with MPP+ caused a significant increase in the level of both cleaved caspase-3 and PARP1 (p < 0.001; Fig. 5c) due to the apoptotic cell death. BCA co-treatment significantly reduced the cleavage and thereby activation of caspase-3 from 320 ± 13.1 in MPP+ tretated cells to 175 ± 11 and 122 ± 16.5 in 50 and 100 µg/ml BCA treated cells, respectively (p < 0.001). Moreover, cleaved and inactivated PARP1 was also significantly decreased from 250 ± 14.7 to 155 ± 4.5 in 50 ug/ml and to 110 ± 17.6 in 100 ug/ml BCA co-treated cells, respectively. (p < 0.001; Fig. 5c).

These results suggested that 50 and 100 μg/ml BCA treatment attenuated the apoptotic effects of MPP+ and protected cells from apoptotic cell death in a concentration dependent manner.

Discussion

PD is one of the leading neurodegenerative disorders characterised by a progressive loss of DA containing neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta (Rabiei et al. 2019; Zeng et al. 2018). The majority of current pharmaceutical therapies are not effective and even can cause further neurodegeneration (Chen et al. 2018). For this reason, any approaches that can diminish dopaminergic cell death and cytotoxicity will be invaluable for prevention from PD. Anthocyanins are well characterised and broadly studied for their role in health promotion, protection and disease prevention (Li et al. 2017; Yousuf et al. 2016). However, there have been no reports analysing the neuroprotective role of BCA on PD. In this study, for the first time we identified that BCA have a neuroprotective activity on MPP+ induced SH-SY5Y cell death via inhibition of ROS mediated oxidative stress and apoptosis.

HPLC–DAD detected anthocyanin profile of black carrot was comparable with those early reported, consisting predominantly acylated derivatives of cyanidin by synaptic, coumaric and ferulic acids and of glucose, galactose and xylose as main sugar moieties (Barba-Espin et al. 2017; Smeriglio et al. 2018). Nevertheless, the yield of cyanidin based anthocyanins may vary among studies due to developmental stage, varieties, enviromental conditions and extraction procedure. In correlation with previous studies, our results displayed a good correlation between the total phenolics and the antioxidant capacity (Algarra et al. 2014). Elevated antioxidant capacity can be attributed to the high levels of acylated anthocyanins compared to non-acylated ones, as recently reported (Moriya et al. 2015). Moreover, acylated anthocyanidins have higher heat stability, thus maintain the structure even in different pH conditions for a prolonged time (Khoo et al. 2017). Therefore, they could be a promising candidate for applications in food and pharmaceutical industries.

It has been shown that significant decrease in the activity of complex I of the ETC is observed in the substantia nigra of PD patients (Hu and Wang 2016). Since MPP+ is a complex 1 inhibitor which is taken into dopaminergic cells via DAT and SH-SY5Y cells own many biochemical characteristics of dopaminergic neurons (Dagda et al. 2013; Xie et al. 2010) we treated the SH-SY5Y cells with MPP+ to model PD in vitro.

Both undifferentiated and differentiated SH-SY5Y cells have been extensively studied as an in vitro model of dopaminergic neurons for PD research (Xie et al. 2010). However, the majority of studies suggest that some differentiation agents confer resistance on SH-SY5Y cells, hence, neuro-toxicity or protection cannot be determined in these differentiated cells (Cheung et al. 2009). In agreement with these studies, we used undifferentiated SH-SY5Y cells as an appropriate cell model for studying neuroprotection in experimental PD research.

Since anthocyanins are among the most frequently consumed flavonoids in our daily diet, they are generally recognized as safe (Winter and Bickford 2019). Nevertheless, dose dependent in vitro cytotoxicity values of numerous studies using anthocyanin rich extracts are varied in terms of anthocyanin content, cell type and exposure time. In our study, viability of SH-SY5Y cells was not significantly affected up to 100 µg/ml BCA treatment for 24 h.

To detect the cytoprotective effects of BCA against MPP+, we initially used Xcelligence, a real time impedance based cell proliferataion detection system. Then, cell viability was assessed with the most commonly used method for quantification of viable cells based on a determination of metabolic activity, MTT assay. Consequently, results of both impedance and metabolic activity based detection methods confirmed that 100 µg/ml BCA treatment significantly rescued the cell viability, with an approximately %30 rise in viable cells after MPP+ treatment. BCA treatment also showed neuroprotective effect via reducing antiproliferative effects of MPP+. Furthermore, we examined the level of plasma membrane damage by LDH release assay. Our results indicates elevated levels of leakiness of cell membrane upon MPP+ exposure, which is then reversed by BCA treatment showing its role in maintaning membrane integrity. The morphology observations support all results above because collapsed cells were dramatically reduced with 100 µg/ml BCA treatment. Indeed, previous studies supported that phytochemicals with higher antioxidant capacity can boost neuronal cell survival (Vargas et al. 2018). These results exhibit that BCA would be safe and convenient for possible functional food applications.

Under normal conditions, the ROS are of great importance because they are intracellular signaling molecules that control many cellular processes and have useful effects on cell survival (Benassi et al. 2016; Hung et al. 2014; Kim et al. 2015). However, oxidative stress occurs when intracellular elevated ROS production overwhelms intrinsic antioxidant capacity and leads to apoptosis by damaging mitochondria (Lin and Beal 2006; Winter and Bickford 2019). Several studies have shown that MPP+ increase ROS in neuroblastoma cells (Cassarino et al. 1997; Fall and Bennett 1999; Zeng et al. 2010) via inhibition of mitochondrial complex I and hence exerts oxidative stress on cells. In our study, exposure of 0.5 mM MPP+ for 24 h caused significantly high levels of ROS accumulation in cells as expected.

Numerous studies have documented reduced levels of ROS and oxidative damage in neuronal cells after treatment with anthocyanin rich extracts obtained from various food sources like boysenberry, blackcurrant, blueberries and black rice bran (Meng et al. 2018; Torma et al. 2017; Vargas et al. 2018; Zhang et al. 2019).

On the other hand, studies about BCA are commonly about the anticancer activities against various cancer cell lines (HT-29, HL-60) by inhibiting cell proliferation (Jing et al. 2008; Netzel et al. 2007; Akhtar et al. 2017) and protective effects against diabetes (Akhtar et al. 2017) and cardiovascular diseases (Wright et al. 2013) by decreasing the blood glucose and cholesterol levels (Ahmad et al. 2019). To date, MPP+ induced ROS scavenging activity of BCA in neural cells has never been tested. Our results demonstrate that BCA exhibited antioxidant activity in a dose dependent manner, via limiting MPP+ induced ROS and protecting dopaminergic neurons against oxidative cell damage.

MPP+ give rise to considerably high cellular levels of ROS which can cause damage to cellular components and thereby lead to activation of cell death processes such as apoptosis. Owing to the significant ROS scavenging activity, the potential anti-apoptotic effect of BCA was evaluated using Annexin V staining method and analysis of cleaved caspase-3 and PARP1 levels on MPP+ treated SH-SY5Y cells.

Studies about the anthocyanins, extracted from purple basil, blackcurrant, blueberry (Strathearn et al. 2014) and mulberry (Kim et al. 2010) have shown the neuroprotective effects of anthocyanins in in vitro and in vivo PD models (Zhang et al. 2019). A recent study have pointed out the neuroprotective effects of cyanidin against MPP+ triggered SH-SY5Y cell death due to its anti-apoptotic and anti-oxidative activities. (Chen et al. 2018). In agrement with these studies, our results indicate, that 50 and 100 μg/ml BCA co-treatment, in addition to its antioxidant properties, presented anti-apoptotic and neuroprotective activity and protected dopaminergic neurons from MPP+ triggered apoptotic cell death.

Conclusion

Overall, our study present the first evidence that BCA significantly protected SH-SY5Y cells from MPP+ induced neurotoxicity by inhibiting ROS mediated oxidative stress and apoptosis. Since there is growing interest in the use of anthocyanins as dietary antioxidant and nutraceutical, further research is required to elucidate the mechanisms of neuroprotection and to illuminate the potential therapeutic effect of BCA in in vivo PD models.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary file1 (TIF 96328 kb) Supplementary Fig. 1 HPLC chromatogram and calibration curve of cyanidin-3-O-glucoside. a HPLC chromatogram of cyanidin-3-O-glucoside standard monitored at 520 nm detection. b Calibration curve of cyanidin-3-glucoside standard.

Acknowledgements

We thank Cihan Altintas and Cagin Cevik for technical support.

Author contributions

MZ designed and performed the experiments, analyzed the results, wrote the paper, and approved the final version; AM analyzed the data, revised the manuscript and approved the final version; IK revised the manuscript and approved the final version.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from Nisantasi University Scientific Research Committee (Project No: BAP00017).

Availability of data and materials

All data generated and/or analyzed during this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests regarding the publication of this paper.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Ahmad T, et al. Phytochemicals in Daucus carota and their health benefits-review. Foods. 2019;8:424. doi: 10.3390/foods8090424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akhtar S, Rauf A, Imran M, Saleem Q, Riaz M, Mubarak MS. Black carrot (Daucus carota L.), dietary and health promoting perspectives of its polyphenols: a review. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2017;66:36–47. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2017.05.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Algarra M, Fernandes A, Mateus N, Freitas V, Joaquim CG, da Silva E, Casado J. Anthocyanin profile and antioxidant capacity of black carrots (Daucus carota L. ssp. sativus var. atrorubens Alef.) from Cuevas Bajas, Spain. J Food Compos Anal. 2014;33:71–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jfca.2013.11.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Apak R, Güçlü K, Özyürek M, Karademir SE, Erçağ E. The cupric ion reducing antioxidant capacity and polyphenolic content of some herbal teas. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2006;57:292–304. doi: 10.1080/09637480600798132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apak R, Güçlü K, Özyürek M, Çelik ES. Mechanism of antioxidant capacity assays and the CUPRAC (cupric ion reducing antioxidant capacity) assay. Microchim Acta. 2008;160:413–419. doi: 10.1007/s00604-007-0777-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barba-Espin G, et al. Foliar-applied ethephon enhances the content of anthocyanin of black carrot roots (Daucus carota ssp. sativus var. atrorubens Alef.) BMC Plant Biol. 2017;17:70. doi: 10.1186/s12870-017-1021-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benassi B, et al. Extremely low frequency magnetic field (ELF-MF) exposure sensitizes SH-SY5Y cells to the pro-Parkinson's disease toxin MPP(.) Mol Neurobiol. 2016;53:4247–4260. doi: 10.1007/s12035-015-9354-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassarino DS, et al. Elevated reactive oxygen species and antioxidant enzyme activities in animal and cellular models of Parkinson's disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1997;1362:77–86. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4439(97)00070-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Sun J, Jiang J, Zhou J. Cyanidin protects SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cells from 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium-induced neurotoxicity. Pharmacology. 2018;102:126–132. doi: 10.1159/000489853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung YT, Lau WK, Yu MS, Lai CS, Yeung SC, So KF, Chang RC. Effects of all-trans-retinoic acid on human SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma as in vitro model in neurotoxicity research. Neurotoxicology. 2009;30:127–135. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2008.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dagda RK, Das Banerjee T, Janda E. How Parkinsonian toxins dysregulate the autophagy machinery. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14:22163–22189. doi: 10.3390/ijms141122163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espinosa-Acosta G, et al. Stability analysis of anthocyanins using alcoholic extracts from black carrot (Daucus carota ssp. sativus Var. atrorubens Alef.) Molecules. 2018;23:1. doi: 10.3390/molecules23112744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fall CP, Bennett JP., Jr Characterization and time course of MPP+-induced apoptosis in human SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells. J Neurosci Res. 1999;55:620–628. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19990301)55:5<620::AID-JNR9>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao X, Cassidy A, Schwarzschild MA, Rimm EB, Ascherio A. Habitual intake of dietary flavonoids and risk of Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2012;78:1138–1145. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31824f7fc4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Q, Wang G. Mitochondrial dysfunction in Parkinson's disease. Transl Neurodegener. 2016;5:14. doi: 10.1186/s40035-016-0060-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung KC, Huang HJ, Lin MW, Lei YP, Lin AM. Roles of autophagy in MPP+-induced neurotoxicity in vivo: the involvement of mitochondria and alpha-synuclein aggregation. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e91074. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0091074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X, Jin T, Zhang H, Miao J, Zhao X, Su Y, Zhang Y. Current progress of mitochondrial quality control pathways underlying the pathogenesis of Parkinson's disease. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2019;2019:4578462. doi: 10.1155/2019/4578462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jing P, Bomser JA, Schwartz SJ, He J, Magnuson BA, Giusti MM. Structure-function relationships of anthocyanins from various anthocyanin-rich extracts on the inhibition of colon cancer cell growth. J Agric Food Chem. 2008;56:9391–9398. doi: 10.1021/jf8005917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khoo HE, Azlan A, Tang ST, Lim SM. Anthocyanidins and anthocyanins: colored pigments as food, pharmaceutical ingredients, and the potential health benefits. Food Nutr Res. 2017;61:1361779. doi: 10.1080/16546628.2017.1361779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HG, et al. Mulberry fruit protects dopaminergic neurons in toxin-induced Parkinson's disease models. Br J Nutr. 2010;104:8–16. doi: 10.1017/S0007114510000218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim MJ, et al. Transduced PEP-1-PON1 proteins regulate microglial activation and dopaminergic neuronal death in a Parkinson's disease model. Biomaterials. 2015;64:45–56. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li D, Wang P, Luo Y, Zhao M, Chen F. Health benefits of anthocyanins and molecular mechanisms: update from recent decade. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2017;57:1729–1741. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2015.1030064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin MT, Beal MF. Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in neurodegenerative diseases. Nature. 2006;443:787–795. doi: 10.1038/nature05292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng L, et al. Anthocyanins extracted from Aronia melanocarpa protect SH-SY5Y cells against amyloid-beta (1–42)-induced apoptosis by regulating Ca(2+) homeostasis and inhibiting mitochondrial dysfunction. J Agric Food Chem. 2018;66:12967–12977. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.8b05404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montilla EC, Arzaba MR, Hillebrand S, Winterhalter P. Anthocyanin composition of black carrot (Daucus carota ssp. sativus var. atrorubens Alef.) cultivars Antonina, Beta Sweet, Deep Purple, and Purple Haze. J Agric Food Chem. 2011;59:3385–3390. doi: 10.1021/jf104724k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriya C, et al. New acylated anthocyanins from purple yam and their antioxidant activity. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2015;79:1484–1492. doi: 10.1080/09168451.2015.1027652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Netzel MNG, Kammerer DR, Schieber A, Carle R, Simons LBI, Bitsch R, Konczak I. Cancer cell antiproliferation activity and metabolism of black carrot anthocyanins. Innov Food Sci Emerg Technol. 2007;8:365–372. doi: 10.1016/j.ifset.2007.03.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rababah TM, Ereifej KI, Esoh RB, Al-u'datt MH, Alrababah MA, Yang W. Antioxidant activities, total phenolics and HPLC analyses of the phenolic compounds of extracts from common Mediterranean plants. Nat Prod Res. 2011;25:596–605. doi: 10.1080/14786419.2010.488232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabiei Z, Solati K, Amini-Khoei H. Phytotherapy in treatment of Parkinson's disease: a review. Pharm Biol. 2019;57:355–362. doi: 10.1080/13880209.2019.1618344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramalingam M, Kim SJ. The neuroprotective role of insulin against MPP(+)-induced Parkinson's disease in differentiated SH-SY5Y cells. J Cell Biochem. 2016;117:917–926. doi: 10.1002/jcb.25376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sevimli-Gur C, Cetin B, Akay S, Gulce-Iz S, Yesil-Celiktas O. Extracts from black carrot tissue culture as potent anticancer agents. Plant Foods Hum Nutr. 2013;68:293–298. doi: 10.1007/s11130-013-0371-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shishido T, et al. Synphilin-1 has neuroprotective effects on MPP(+)-induced Parkinson's disease model cells by inhibiting ROS production and apoptosis. Neurosci Lett. 2019;690:145–150. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2018.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smeriglio A, Denaro M, Barreca D, D'Angelo V, Germano MP, Trombetta D. Polyphenolic profile and biological activities of black carrot crude extract (Daucus carota L. ssp sativus var. atrorubens Alef.) Fitoterapia. 2018;124:49–57. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2017.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song FL, Gan RY, Zhang Y, Xiao Q, Kuang L, Li HB. Total phenolic contents and antioxidant capacities of selected chinese medicinal plants. Int J Mol Sci. 2010;11:2362–2372. doi: 10.3390/ijms11062362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strathearn KE, et al. Neuroprotective effects of anthocyanin- and proanthocyanidin-rich extracts in cellular models of Parkinsons disease. Brain Res. 2014;1555:60–77. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2014.01.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torma PD, et al. Hydroethanolic extracts from different genotypes of acai (Euterpe oleracea) presented antioxidant potential and protected human neuron-like cells (SH-SY5Y) Food Chem. 2017;222:94–104. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsutsumi A, et al. Acylated anthocyanins derived from purple carrot (Daucus carota L.) induce elevation of blood flow in rat cremaster arteriole. Food Funct. 2019;10:1726–1735. doi: 10.1039/c8fo02125b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vagiri M, Ekholm A, Andersson SC, Johansson E, Rumpunen K. An optimized method for analysis of phenolic compounds in buds, leaves, and fruits of black currant (Ribes nigrum L.) J Agric Food Chem. 2012;60:10501–10510. doi: 10.1021/jf303398z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vargas CG, et al. Bioactive compounds and protective effect of red and black rice brans extracts in human neuron-like cells (SH-SY5Y) Food Res Int. 2018;113:57–64. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2018.06.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter AN, Bickford PC. Anthocyanins and their metabolites as therapeutic agents for neurodegenerative disease. Antioxidants. 2019 doi: 10.3390/antiox8090333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright OR, Netzel GA, Sakzewski AR. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of the effect of dried purple carrot on body mass, lipids, blood pressure, body composition, and inflammatory markers in overweight and obese adults: the QUENCH trial. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2013;91:480–488. doi: 10.1139/cjpp-2012-0349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie HR, Hu LS, Li GY. SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cell line: in vitro cell model of dopaminergic neurons in Parkinson's disease. Chin Med J. 2010;123:1086–1092. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yousuf B, Gul K, Wani AA, Singh P. Health benefits of anthocyanins and their encapsulation for potential use in food systems: a review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2016;56:2223–2230. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2013.805316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng G, et al. Salvianolic acid B protects SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells from 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium-induced apoptosis. Biol Pharm Bull. 2010;33:1337–1342. doi: 10.1248/bpb.33.1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng XS, Geng WS, Jia JJ, Chen L, Zhang PP. Cellular and molecular basis of neurodegeneration in Parkinson disease. Front Aging Neurosci. 2018;10:109. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2018.00109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, et al. Neuroprotective effects of anthocyanins and its major component cyanidin-3-O-glucoside (C3G) in the central nervous system: an outlined review. Eur J Pharmacol. 2019;858:172500. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2019.172500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary file1 (TIF 96328 kb) Supplementary Fig. 1 HPLC chromatogram and calibration curve of cyanidin-3-O-glucoside. a HPLC chromatogram of cyanidin-3-O-glucoside standard monitored at 520 nm detection. b Calibration curve of cyanidin-3-glucoside standard.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated and/or analyzed during this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.