Abstract

Interpositional gap arthroplasty has established itself as the the standard surgical treatment of Temporomandibular joint (TMJ) ankylosis. The autogenous tissue has replaced the alloplastic and other xenografts materials owing to its bioavailability, easy uptake, and no additional cost. Commonly used autogenous tissue has been temporalis muscle and fascia, fascia lata, skin graft, auricular and costal cartilage, the masseter and/or medial pterygoid muscle. With the turn of the century, TMJ surgeons started using autogenous fat from the lower abdomen and today it has taken over as the most favored autogenous filler material in TMJ ankylosis surgery or total joint replacement (TMJ-TJR). The use of buccal fat pad (BFP) has increased in the last decade due to its local availability and pedicled nature. This paper will discuss various autogenous tissues used in interposition and bring forth the journey of the autogenous fat as the preferred interpositional material now and rest the case in its favor.

Keywords: Temporomandibular joint, Buccal fat pad, Abdominal fat, TMJ ankylosis, Interpositional gap arthroplasty, Autogenous fat graft, TMJ total joint replacement

Introduction

Interpositional gap arthroplasty has over the past few decades become the standard surgical treatment of temporomandibular joint (TMJ) ankylosis [1–4]. The first interpositional graft was developed by Eschmarc in the latter half of the nineteenth century who described the pterygo-masseteric sling technique of suturing together the masseter and medial pterygoid muscles across a divided mandibular ramus [5]. The rationale behind the procedure was to obliterate the dead space created after removal of ankylotic bony mass that, if not filled, will again pool in blood and encourage reformation of heterotopic bone. It also encourages hemostasis and prevents clot formation thus minimizing the chances of reankylosis [6].

Various materials have been used over the years, and slowly and steadily, the autogenous tissue has replaced the alloplastic and other xenografts materials owing to its bioavailability, easy uptake, and no additional cost. Alloplastic materials such as acrylic, silicon, and various metals showed significantly high rejection rates and foreign body reactions which necessitated its removal [7]. In the previous century, the most commonly used autogenous tissue has been temporalis muscle and fascia, others being fascia lata, skin graft, auricular and costal cartilage, the masseter, or medial pterygoid muscle. Most of the literature published from the period highlighted temporalis muscle as the ideal autogenous tissue because of its local availability and ease of rotation [8–10].

With the turn of the century, TMJ surgeons started using autogenous fat from the lower abdomen due to its ease in harvesting, abundance, minimal morbidity, and long-term survival. Today, it has taken over as the most favored autogenous filler material in TMJ ankylosis surgery or total joint replacement (TMJ-TJR). The use of buccal fat pad (BFP) has increased in the last decade due to its local availability and pedicled nature. The fluid nature of the fat helps it to obliterate the dead space completely and achieve hemostasis [11]. This paper will bring forth the journey of autogenous fat as the most favored interpositional material today and rest the case in its favor.

Autogenous Tissue as Interpositional Material

Interpositional grafts should fulfill the following criteria: It should be cost-effective, obliterate the created gap, avoid aesthetic and functional morbidity at the donor site, tolerate and adapt to masticatory forces, be associated with low risk of infection, and guard against heterotopic bone formation leading to reankylosis [12]. It is imperative to discuss the history, advantages, and disadvantages of other commonly used autogenous tissues to have a better understanding of the material of interest, i.e., autogenous fat.

Temporalis Muscle and/or Fascia

The use of temporalis muscle and/or fascia was first proposed by Verneuil in 1860 and later strengthened in a review of 212 cases by Blair in 1913 [13, 14]. The ease and availability of temporalis muscle and fascia due to its proximity and reliable blood supply made it easy to rotate it in the gap created [8, 9]. The most commonly used Al-Kayat Bramley modified preauricular incision to expose the TMJ region provided a common approach for both the gap arthroplasty procedure and temporalis rotation. This is in common with the harvesting of BFP where no additional site is opened, thus nullifying any donor site morbidity. Feinberg and Larsen stated that one of the most important roles of the temporalis muscle flap is the maintenance of functional movements [10]. Because the flap is attached to the coronoid process, when the mandible translates, the movement of the mandible pulls the muscle flap in an anterior direction, simulating the natural functional movements of the disk. But temporal hollowing, hematoma formation, pain, and tenderness associated with temporal muscle rotation have been a few of the associated complications. Muscle scarring and resorption of fascia were attributed to the disrupted vascularity. Pain and tenderness at the surgical site led to decreased patient compliance for active jaw physiotherapy that indirectly increased the chances of reankylosis [15].

Auricular Cartilage

Auricular cartilage was proposed to mimic the articular disk when placed in the gap by several authors. Perko was the first to report the use of fresh autogenous auricular cartilage for disk repair [16]. Animal studies conducted by Ioannides and Maltha showed that the autogenous auricular cartilage retained its viability without reactive or resorptive changes and appeared to be suitable as an autogenous tissue graft in both experiments [17]. Contrary to this, long-term histological examination in the animal model showed fibrous adhesion of the grafted auricular cartilage to the condyle and the presence of a fibrous layer containing fragmented cartilage on the articular surface. There was a tendency of the auricular graft to fragment, proliferate and result in fibrous ankylosis of the TMJ with progressive limitation of mouth opening. Slowly over some time, it phased out from being an interpositional material of choice [18, 19].

Dermis Graft

Dermis has been used for the repair of the TMJ disk as well as for the treatment of ankylosis and was first introduced by Georgiade et al. in 1957 as an interpositional graft in the management of TMJ ankylosis and later in 1962 as a substitute after disk replacement in TMJ discectomy cases [20]. Since then, there have only been a few clinical studies published on the use of dermis grafts for disk repair and disk replacement material in the TMJ. The clinical study by Dimitroulis of 35 joints in 29 patients demonstrated that dermis grafts were effective in reducing joint sounds, but the author conceded that dermis grafts were difficult to anchor and failed to prevent regressive remodeling of the condyle [21].

Costochondral Grafts

The costochondral graft (CCG) has dominated as an ideal reconstruction material to replace the lost ramal-condylar unit (RCU). Its growth potential has made it an ideal graft in young patients with TMJ ankylosis. But various complications like over- or undergrowth, resorption, and donor site morbidity have been reported over the years. In a systematic review, the author's unit had found no concrete evidence of any advantage of costochondral grafts in comparison with other reconstruction materials [22].

Biology of Fat Interposition

The biological basis of using autogenous fat lies in its dual property of encouraging hemostasis and inhibition of osteogenesis. According to Lexer, the hemostatic property of fat is due to the fast attachment of fat tissue to a bleeding site, therefore blocking the vessels and preventing further bleed in the gap. Surrounding tissue is prevented to grow in, form scar tissue, and form heterotopic bone [23]. Merikanto et al. demonstrated that fat grafts inhibit osteogenesis in bone defects and encourage adipogenesis. [24] Saunders et al. demonstrated that free fat grafts go through a period of the initial breakdown of fat cells, followed by revascularization, resulting in normal-appearing fat, although a smaller volume than originally grafted. The fat grafts were almost normal at 6 months [25]. Yamaguchi et al. demonstrated the importance of early and adequate revascularization of autogenous fat grafts for maintenance of graft volume and the production and interaction of adipocyte-derived angiogenic peptides such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and leptin, important for graft survival and volume maintenance [26]. Qi et al. demonstrated that at early stages following free fat grafting, the fat showed ischemia. The adipocytes released lipid and dedifferentiated to preadipocytes. After revascularization, the preadipocytes began to absorb lipid and became mature adipocytes [27].

Abdominal Fat

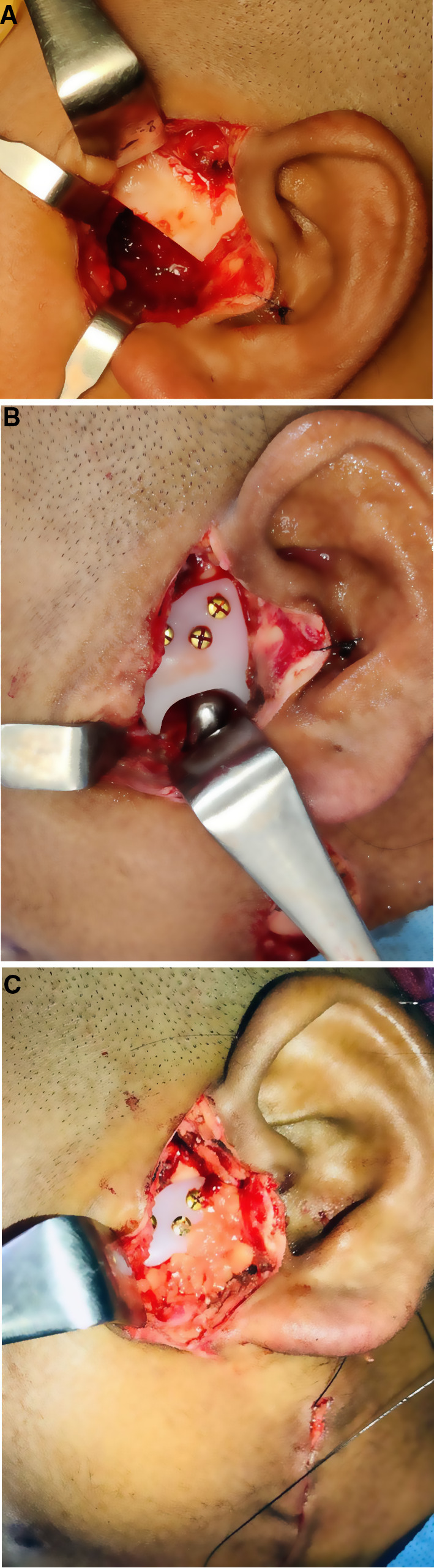

The use of abdominal fat (AF) as interpositional material has a longer history than BFP. Both dermis fat and free fat have been used extensively in TMJ surgeries (Table 1). The added advantage of the attached dermis layer is that it prevents fragmentation of the fat although free fat has been increasingly used now for all TMJ surgeries. Wolford and Karras showed the advantages of fat grafting around alloplastic implants in the TMJ [28, 29]. They rationalized the use of dermis-fat as an interpositional graft due to its abundance in the lower abdomen, low donor site morbidity, and also its ability to act as a simple space filler for the joint cavity to prevent direct contact between the ramal stump and glenoid fossa. The volume of harvested AF ranges from 5 to 20 ml. Wolford et al. have advised harvesting 20–30% more fat to cover for a potential shrinkage in the postoperative period [28, 29]. TJR requires an approximate gap of 3 cm as compared to 1–1.5 in gap arthroplasty in TMJ ankylosis cases (Fig. 1a–c). BFP may lack in volume to fill in space created for TJR, and hence, surgeons prefer AF in TJR surgery. Long-term survival of AF has shown it to have a shrinkage value ranging from 20 to 75% [30]. MRI studies have narrowed down the shrinkage to around 33% after 1 year. While the signal intensity of the grafted fat was lower than that of normal subcutaneous fat tissue in the first 6 weeks following surgery, the intensity had recovered to normal status by 1 year after surgery. This shows adipogenesis in the fat under function and has been explained later in this text [31].

Table 1.

Review of literature for the use of abdominal fat (AF) after gap arthroplasty in TMJ ankylosis

| S No | Authors | N | Nature of study | Follow up | Recurrence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | Wolford et al.,1997 [28] | 15 | Free fat interposition | 1 Year | 0 |

| 3 | Dimitroulis G et al., 2004 [21] | 11 | Dermis fat interposition | 2–6 Years | 1 |

| 4 | Dimitroulis G et al., 2008 [30] | 11 | MRI evaluation after Dermis Fat interposition | 2–6 Years | 1 |

| 5 | Mehrotra D et al., 2008 [15] | 8 | Dermal Fat vs Temporal Fascia (TF) interposition | 2 Years | 0 |

| 7 | Mercuri LG et al., 2008 [42] | 20 | Free Fat interposition | 2–9 Years | 0 |

| 8 | Thangavelu A et al., 2011 [44] | 7 | Dermal Fat interposition | 1–2 years | 0 |

| 9 | Gandhiraj S et al., 2013 [48] | 5 | Dermal Fat interposition | 2 Years | 0 |

| 10 | Karamese M et al., 2013 [49] | 11 | TF + AF interposition | 3–6 Years | 0 |

| 12 | Thangavelu A et al., 2015 [31] | 5 | MRI evaluation after Dermis Fat interposition | 0.5–5 years | 0 |

| 13 | Hegab AF, 2015 [50] | 14 | Dermal Fat interposition | 2–4 Years | 0 |

| 14 | Wolford et al., 2016 [29] | 32 | Free Fat interposition | 1–14 Years | 2 |

| 15 | El Gengehy MT et al., 2019 [32] | 5 | CCG with/without Fat interposition | 0.5 Years | 0 |

Fig. 1.

a–c Interpositional gap arthroplasty with abdominal fat (AF) after fixation of TJR (picture courtesy: Prof. Ajoy Roychoudhury, AIIMS, New Delhi)

Malhotra et al. in their comparative study of dermis fat with temporal fascia found that interposition of dermis-fat graft in TMJ ankylosis showed better results in terms of mouth-opening, jaw function, and recurrence, because of the bulk of viable material interposed in the surgically created gap after the arthroplasty [15]. Gengehy et al. compared the outcome of costochondral grafts in TMJ reconstruction with and without AF in bilateral temporomandibular joint ankylosis. Though the results were encouraging, it was non-significant in the context of relapse or mouth opening [32]. In a systematic review of the use of AF in TJR surgeries, Bogaert et al. found that despite all the positive results regarding the use of AF in TMJ TJR, scientific evidence remains limited [11]. Further evaluation employing a prospective multicenter randomized controlled trial is needed to achieve more definitive results of this seemingly promising technique.

Buccal Fat Pad

The author's unit was the first to use and report BFP as interpositional material in 2006 and its long-term fate in an MRI study in 2011 [33–35]. We have subsequently used it in more than 300 cases of TMJ ankylosis since 2005. Its availability in the proximity of the surgical site and retrieval from the same preauricular incision (predominately Al-Kayat and Bramley incision) are its primary advantage (Fig. 2 a–c). Its independent vascular supply owing to its pedicled nature helps in its long-term survival. Its sufficient volume especially in children and minimal morbidity makes it an ideal material for a younger cohort of patients. Our recently published data on quality of life assessment in TMJ ankylosis patients treated with BFP interpositional gap arthroplasty showed improved outcomes in both adult and pediatric populations in all parameters [36–38]. Malhotra et al. advocated the use of BFP in lateral arthroplasty cases where the medially displaced condyle is preserved to maintain the vertical of the ramus. The BFP prevents heterotopic bone formation at the lateral aspect of the condyle [39]. BFP is slowly gaining acceptance due to its proximity and ease of retrieval in TMJ ankylosis cases (Table 2).

Fig. 2.

a–c Interposition of buccal fat pad (BFP) after gap arthroplasty in TMJ ankylosis

Table 2.

Review of literature for the use of buccal fat pad (BFP) as interpositional material after gap arthroplasty in TMJ ankylosis

| S No | Authors | N | Nature of study | Follow Up | Recurrence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Rattan V, 2006 [33] | 2 | Pilot study for BFP interposition | 1–2 years | 0 |

| 2 | Ko EC et al., 2009 [47] | 2 | Intraoral gap arthroplasty and harvest of BFP with interposition | > 1 Year | 0 |

| 3 | Singh V, 2011[45] | 10 | Prospective non-comparative BFP interposition | 0.5–2 Years | 0 |

| 4 | Singh V, 2012 [46] | 10 | BFP interposition with Sternoclavicular graft | 6–9 Months | 0 |

| 5 | Gaba S et al., 2012 [34] | 18 | MRI study after BFP interposition | 1 Year | 0 |

| 6 | Bansal V et al., 2015 [40] | 11 | USG study after BFP interposition | 2–3 Years | 0 |

| 7 | Malhotra VL et al., 2019 [39] | 10 | Lateral arthroplasty with BFP interposition | 0.5–2.5 Years | 0 |

| 8 | Roychoudhury et al., 2020 [41] | 18 | MRI evaluation after AF and BFP interposition | 1 Year | 0 |

The fate of Abdominal vs buccal Fat

According to Lexer, a fat graft shrinks in 1 year, and the volume can diminish as much as two-thirds of its original volume. He stated that multiple small fat grafts do not survive as well as a single large graft. He concluded that fat grafts survive with an average loss of about 45% of their original weight and volume 1 year after transplantation [23]. Bansal et al. used ultrasonography to perform a volumetric analysis of BFP in TMJ ankylosis cases. The mean volume of BFP harvested was 1.1–1.8 ml, and the shrinkage was approximately 28% after 6 months [40]. Their results corroborated with our MRI results and showed that BFP retained its significant volume after a year of follow-up. Roychoudhary et al. have compared the fate of both AF and BFP with MRI over 1 year. AF was shown to be more resistant to resorption than BFP. The reason advocated has been its larger volume, large-sized lobules, and firm consistency [41]. The basic difference between the BFP and AF is the pedicled nature of the former and the large volume of the latter. Trevor et al. showed there was no demonstrable difference in treatment outcomes following placement of a free fat graft vs. a pedicle fat graft [42]. Hence, the most important criteria narrow down to the adequate volume of fat that completely obliterates the cavity. In this context, abdominal fat scores high than BFP that has a limited volume to be used because of its attached pedicle.

Conclusion

It is no controversy now that autogenous fat has replaced every other tissue as the ideal interpositional material in TMJ joint ankylosis or TJR surgeries. The scale tilts more toward BFP because of its local presence, easy harvesting, and pedicled nature. It should be the first choice in gap arthroplasties where the gap is not more than 1–1.5 cm. Long-term studies have shown it to be viable and maintaining its position at the surgical site. Abdominal fat has a longer history of use in TMJ surgeries and is still the first choice for many surgeons across the world. Its abundance in volume and long-term survival have kept it a primary option for TJR surgeries where the created gap is larger than a routine gap arthroplasty in ankylosis cases.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Topazian RG. Comparison of gap and interpositional arthroplasty. J Oral Surg. 1966;24:405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moorthy AP, Finch LD. Interpositional arthroplasty for ankylosis of the temporomandibular joint. Oral Surg. 1983;55:545. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(83)90366-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rowe NL. Ankylosis of the temporomandibular joint. J R Coll Surg Edinb. 1982;27:67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tideman H, Doddridge M. Temporomandibular joint ankylosis. Aust Dent J. 1987;32:171. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.1987.tb01850.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moore JR, editor. Surgery of the face and mouth. Oxford, UK: Blackwell; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pogrel MA, Kaban LB. The role of the temporalis fascia and muscle flap in temporomandibular surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1990;48:14. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(90)90173-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Al-Moraissi EA, El-Sharkawy TM, Mounair RM, El-Ghareeb TI. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the clinical outcomes for various surgical modalities in the management of temporomandibular joint ankylosis. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015;44(4):470–482. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2014.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Albert TW, Merrill RG. Temporalis muscle flap for reconstruction of the temporomandibular joint. Oral Maxillofac Clin N Am. 1989;1:341. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brusati R, Raffaini M, Sesenna E. The temporalis muscle flap in temporomandibular joint surgery. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 1990;18:352. doi: 10.1016/S1010-5182(05)80055-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feinberg SE, Larsen PE. The use of a pedicled temporalis muscle-pericranial flap for the replacement of the TMJ disc. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1989;47:142. doi: 10.1016/S0278-2391(89)80104-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Van Bogaert W, De Meurechy N, Mommaerts MY. Autologous fat grafting in total temporomandibular joint replacement surgery. Ann Maxillofac Surg. 2018;8:299–302. doi: 10.4103/ams.ams_165_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dimitroulis G. A critical review of interpositional grafts following temporomandibular joint discectomy with an overview of the dermis-fat graft. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011;40(6):561–568. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2010.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blair VP. Operative treatment of ankylosis of the mandible. Trans South Surg Assoc. 1913;28:435. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murphy JB. Arthroplasty for intra-articular bony and fibrous ankylosis of temporomandibular articulation. JAMA. 1914;62:1783–1794. doi: 10.1001/jama.1914.02560480017006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mehrotra D, Pradhan R, Mohammad S, Jaiswara C. Random control trial of dermis-fat graft and interposition of temporalis fascia in the management of temporomandibular ankylosis in children. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;46:521–526. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perko M. Indikationen und Kontraindikationen für chirurgische Eingriffe am Kiefergelenk: Schweiz. Mschr. Zahnheilkunde 1973:83 [PubMed]

- 17.Ioannides C, Maltha JC. Replacement of the intraarticular disc of the craniomandibular joint with fresh autogenous sternal or auricular cartilage. J Cranio Maxillofac Surg. 1988;16:343. doi: 10.1016/S1010-5182(88)80077-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Takatsuka S, Narinobou M, Nakagawa K, et al. Histologic evaluation of articular cartilage grafts after discectomy in the rabbit craniomandibular joint. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1996;54:1216. doi: 10.1016/S0278-2391(96)90355-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sandler NA, MacMillan C, Buckley MJ, Barnes L. Histological and histochemical changes in failed auricular cartilage grafts used for a temporomandibular joint disc replacement. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1997;55:1014–1019. doi: 10.1016/S0278-2391(97)90082-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Georgiade NG. The surgical correction of temporomandibular joint dysfunction by means of autogenous der- mal grafts. Plast Reconstr Surg Transplant Bull. 1962;30:68–73. doi: 10.1097/00006534-196207000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dimitroulis G. The interpositional dermis-fat graft in the management of temporomandibular joint ankylosis. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004;33:755–760. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2004.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kumar P, Rattan V, Rai S. Do costochondral grafts have any growth potential in temporomandibular joint surgery? A systematic review. J Oral Bio Craniofac Res. 2015;5(3):198–202. doi: 10.1016/j.jobcr.2015.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lexer E. Freie fett transplantation. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 1910;36:640. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Merikanto JE, Alhopuro S, Ritsilä VA. Free fat transplant prevents osseous reunion of skull defects A new approach in the treatment of craniosynostosis. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg. 1987;21(2):183–188. doi: 10.3109/02844318709078098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saunders MC, Keller JT, Dunsker SB, Mayfield FH. Survival of autogenous fat grafts in humans and in mice. Connect Tissue Res. 1981;8:85–91. doi: 10.3109/03008208109152128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yamaguchi M, Matsumoto F, Bujo H, et al. Revascularization determines volume retention and gene expression by fat grafts in mice. Exp Biol Med. 2005;230:742–748. doi: 10.1177/153537020523001007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Qi Z, Li E, Wang H. Experimental study on free grafting of fat particles. Zhonghua Zheng Xing Shal Shang Wai Ke Za Zhi. 1997;13:54–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wolford LM, Karras SC. Autologous fat transplantation around temporomandibular joint total joint prostheses: preliminary treatment outcomes. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1997;55:245–251. doi: 10.1016/S0278-2391(97)90535-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wolford L, Movahed R, Teschke M, Fimmers R, Havard D, Schneiderman E. Temporomandibular joint ankylosis can be successfully treated with TMJ concepts patient-fitted total joint prosthesis and autogenous fat grafts. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2016;74(6):1215–1227. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2016.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dimitroulis G, Trost N, Morrison W. The radiological fate of dermis-fat grafts in the human temporomandibular joint using magnetic resonance imaging. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;37(3):249–254. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2007.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thangavelu A, Thiruneelakandan S, Prasath CH, Chatterjee D. Fate of free fat dermis graft in tmj interpositional gap arthroplasty: a long term MRI study. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2015;14(2):321–326. doi: 10.1007/s12663-014-0672-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gengehy El, Ali S, Abdel-Moneim HS. Costochodral graft with abdominal fat as interpositinal graft versus costochodral graft alone for reconstruction of temporomandibular joint in bilateral ankylosis in adults: randomized controlled clinical trial. Egyptian Dental J. 2019;65:1025–1033. doi: 10.21608/edj.2019.72018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rattan V. A simple technique for use of buccal pad of fat in temporomandibular joint reconstruction. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;64(9):1447–1451. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2005.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gaba S, Sharma RK, Rattan V, Khandelwal N. The long-term fate of pedicled buccal pad fat used for interpositional arthroplasty in TMJ ankylosis. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2012;65(11):1468–1473. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2012.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rattan V, Rai S, Vaiphei K. Use of buccal pad of fat to prevent heterotopic bone formation after excision of myositis ossificans of medial pterygoid muscle. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;66(7):1518–1522. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2007.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sharma VK, Rattan V, Rai S, Malhi P. Quality of life assessment in temporomandibular joint ankylosis patients after interpositional arthroplasty: a prospective study. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2019;48(11):1448–1455. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2019.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sharma VK, Rattan V, Rai S, Malhi P. Assessment of paediatric quality of life in temporomandibular joint ankylosis patients after interpositional arthroplasty: a pilot study. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2020;49(2):244–249. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2019.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mokhtar EA, Rattan V, Rai S, Jolly SS, Lal V. Analysis of maximum bite force and chewing efficiency in unilateral temporomandibular joint ankylosis cases treated with buccal pad of fat interpositional arthroplasty. British J Oral and Maxillofac Surg. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2021.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Malhotra VL, Singh V, Rao JD, et al. Lateral arthroplasty along with buccal fat pad inter-positioning in the management of Sawhney type III temporomandibular joint ankylosis. J Korean Assoc Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2019;45(3):129–134. doi: 10.5125/jkaoms.2019.45.3.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bansal V, Bansal A, Mowar A, Gupta S. Ultrasonography for the volumetric analysis of the buccal fat pad as an interposition material for the management of ankylosis of the temporomandibular joint in adolescent patients. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015;53(9):820–825. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2015.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Roychoudhury A, Acharya S, Bhutia O, Seith Bhalla A, Manchanda S, Pandey RM. Is there a difference in volumetric change and effectiveness comparing pedicled buccal fat pad and abdominal fat when used as interpositional arthroplasty in the treatment of temporomandibular joint ankylosis? J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2020;78(7):1100–1110. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2020.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Trevor PB, Martin RA, Saunders GK, Trotter EJ. Healing characteristics of free and pedicle fat grafts after dorsal laminectomy and durotomy in dogs. Vet Surg. 1991;20(5):282–290. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-950X.1991.tb01268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mercuri LG, Ali FA, Woolson R. Outcomes of total alloplastic replacement with periarticular autogenous fat grafting for management of reankylosis of the temporomandibular joint. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;66:1794–1803. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2008.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thangavelu A, Santhosh Kumar K, Vaidhyanathan A, Balaji M, Narendar R. Versatility of full thickness skin-subcutaneous fat grafts as interpositional material in the management of temporomandibular joint ankylosis. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011;40(1):50–56. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2010.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Singh V, Dhingra R, Sharma B, Bhagol A, Kumar P. Retrospective analysis of use of buccal fat pad as an interpositional graft in temporomandibular joint ankylosis: preliminary study. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011;69(10):2530–2536. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2011.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Singh V, Dhingra R, Bhagol A. Prospective analysis of temporomandibular joint reconstruction in ankylosis with sternoclavicular graft and buccal fat pad lining. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012;70(4):997–1006. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2011.02.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ko EC, Chen MY, Hsu M, Huang E, Lai S. Intraoral approach for arthroplasty for correction of TMJ ankylosis. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;38(12):1256–1262. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2009.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gandhiraj S, Chauhan S, Prakash, Efficacy of abdominal dermis fat graft as the interpositional material in the management of temporomandibular joint ankylosis in children-an original study. IOSR J Dental Med Sci. 2013;3(6):7–11. doi: 10.9790/0853-0360711. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Karamese M, Duymaz A, Seyhan N, Keskin M, Tosun Z. Management of temporomandibular joint ankylosis with temporalis fascia flap and fat graft. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2013;41(8):789–793. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2013.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hegab AF. Outcome of surgical protocol for treatment of temporomandibular joint ankylosis based on the pathogenesis of ankylosis and re-ankylosis a prospective clinical study of 14 patients. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015;73(12):2300–2311. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2015.06.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]