Abstract

Cardiomyocytes can adapt their size, shape, and orientation in response to altered biomechanical or biochemical stimuli. The process by which the heart undergoes structural changes—affecting both geometry and material properties—in response to altered ventricular loading, altered hormonal levels, or mutant sarcomeric proteins is broadly known as cardiac growth and remodeling (G&R). Although it is likely that cardiac G&R initially occurs as an adaptive response of the heart to the underlying stimuli, prolonged pathological changes can lead to increased risk of atrial fibrillation, heart failure, and sudden death. During the past few decades, computational models have been extensively used to investigate the mechanisms of cardiac G&R, as a complement to experimental measurements. These models have provided an opportunity to quantitatively study the relationships between the underlying stimuli (primarily mechanical) and the adverse outcomes of cardiac G&R, i.e., alterations in ventricular size and function. State-of-the-art computational models have shown promise in predicting the progression of cardiac G&R. However, there are still limitations that need to be addressed in future works to advance the field. In this review, we first outline the current state of computational models of cardiac growth and myofiber remodeling. Then, we discuss the potential limitations of current models of cardiac G&R that need to be addressed before they can be utilized in clinical care. Finally, we briefly discuss the next feasible steps and future directions that could advance the field of cardiac G&R.

Keywords: Cardiac growth, Myofiber remodeling, Multiscale modeling, Machine learning, Cardiomyopathy, Sarcomeres

Introduction

The heart, whose primary function is to pump blood through the circulatory system in a regulated manner, is a complex organ that is governed by multiple physics operating across multiple scales. It is able to adapt its geometry (Nakamura and Sadoshima 2018) and function (Rajendra Acharya et al. 2006; Swynghedauw 1986) accordingly with acute or chronic alterations in pumping demand. Similar to skeletal muscle (Wisdom et al. 2015), the myocardial cells that make up the heart muscle (Hill and Olson 2008) can evolve in size and dimension in response to neurohormonal, chemical, and mechanical stimulus signals. This process, referred to as cardiac growth and remodeling (G&R), includes sub-processes at the cellular level such as sarcomerogenesis (Ehler and Gautel 2008) and myocardial fibrosis (Weber and Brilla 1991). At the organ level, this hypertrophic response, depending on the disease, is manifested through wall thickening and/or chamber dilation. Usually in the field of cardiac biomechanics, the term “cardiac growth” refers to changes in the geometry of the heart, whereas “cardiac remodeling” refers to changes in material properties of the cardiac tissue, induced by myofiber disarray, myocardial fibrosis, and altered contractility.

Cardiac G&R can occur due to physiological-related demands (physiological hypertrophy) like pregnancy and athletic activities, or it can happen in response to pathological demands (pathological hypertrophy) such as valvular dysfunction and genetic mutation. Both types of cardiac G&R initiate as an adaptive response to the underlying stimuli but are significantly different in terms of the molecular mechanisms, signaling pathways, and the ultimate clinical outcome (Nakamura and Sadoshima 2018) as briefly described below.

Physiological hypertrophy is considered to be an adaptive mechanism where the cardiac mass increases due to the growth of cardiomyocytes in both length and width. A heart with physiological hypertrophy has preserved or even increased systolic function. However, this increase does not lead to changes in extracellular matrix or fibrosis (Chung and Leinwand 2014). In addition, physiological hypertrophy is a fully reversible phenomenon, except for the postnatal hypertrophy. For example, the left ventricular dimension in trained athletes is significantly larger than non-athletic individuals (Fagard 2003; Milliken et al. 1988) but can return to a normal size after training is stopped (Maron and Pelliccia 2006). During pregnancy, elevated hormones (Li et al. 2012), increased blood volume, and cardiac output (Savu et al. 2012) cause the left ventricle (LV) to undergo an adaptive hypertrophy that returns to the normal condition within 2 weeks postpartum (Umar et al. 2012).

Pathological hypertrophy is classified as an early adaptive and compensatory response to abnormal ventricular loading or mutant sarcomeric proteins (Frey and Olson 2003). Prolonged pathological hypertrophy, however, can be maladaptive, causing myocardial fibrosis and altering myocyte function (e.g., Ca2+ handling) that can impair systolic or diastolic function, which in turn can lead to irreversible growth and heart failure (Hill and Olson 2008; Shimizu and Minamino 2016). There are 2 classical types of pathological hypertrophy that are defined based on ventricular geometry resulting from the disease. (1) Concentric hypertrophy is when the LV wall thickens and cardiac mass increases with little or no change in the chamber volume because of the parallel deposition of sarcomeres in cardiomyocytes (Hill and Olson 2008). (2) Eccentric hypertrophy or dilated hypertrophy is when the chamber volume dilates and cardiac mass increases with a small change in the wall thickness due to the serial addition of sarcomeres and lengthening of cardiomyocytes (Hill and Olson 2008). Although many heart diseases can produce these 2 types of pathological cardiac hypertrophy, three prevalent causes are illustrated in the following.

Pressure overloading is an external abnormal mechanical loading in which the ventricular afterload increases. To overcome the elevated afterload, the contractile stress in the sarcomeres increases to generate enough force to pump blood out of the LV and into the rest of the body (Pitoulis and Terracciano 2020). In accordance with Laplace’s law, the heart increases the ventricular wall thickness by deposition of sarcomeres in parallel to alleviate the elevated wall stress. This wall thickening can result in diastolic dysfunction and impaired filling of the LV, which in turn can lead to heart failure (Lalande and Johnson 2008). This is the characteristic feature of concentric hypertrophy that is generally seen during pressure overloading. Among the different types of disorder in the vasculature that can cause pressure overloading, hypertension is arguably the most common one. It can be either the primary cause or the secondary outcome of other diseases like kidney or thyroid disorders (Berta et al. 2019; Drazner 2011). Another prevalent cause of pressure overloading is aortic stenosis, a valvular disease where the aortic valve does not open properly or becomes narrow (Carabello and Paulus 2009). A stenotic valve can happen due to congenital heart defects, like a bicuspid aortic valve (Siu and Silversides 2010), or the deposition of calcium on the aortic valve (Lindman et al. 2016).

Volume overloading is another type of abnormal ventricular loading in which the LV is filled with excess blood during diastole, which results in an elevated ventricular preload (Pitoulis and Terracciano 2020). Valvular disorders that lead to imperfect closure of the valves are the most prevalent cause of volume overloading. For instance, mitral valve regurgitation occurs when the mitral valve does not close properly during systole, causing back flow of the blood into the left atrium, which in turn increases diastolic filling of the ventricle (Enriquez-Sarano et al. 2009). Similarly, aortic valve regurgitation is another type of valvular disorder where the aortic valve does not tightly close during diastole, which leads to overloading of the LV by retrograde flow of blood from the aorta back into the LV (Akinseye et al. 2018). Excessive filling of the LV results in overstretching of sarcomeres, which initiates the process of sarcomerogenesis whereby the number of sarcomeres is increased in series (Ehler and Gautel 2008). This elongation process essentially re-establishes the sarcomeres back to an optimal force-generating length (Wisdom et al. 2015). Eccentric hypertrophy is a distinctive outcome of volume overloading whereby the dilated chamber would preserve the stroke volume in response to excessive diastolic filling (Carabello et al. 1992). According to Laplace’s law, dilation of the chamber volume elevates the wall stress because of the reduction in h/r ratio (Pitoulis and Terracciano 2020) where h and r are the ventricular wall thickness and chamber radius, respectively, but will be normalized by wall thickening of the LV to preserve the mass-to-volume ratio (Grossman et al. 1975).

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is the most common form of genetic heart disease, which is caused by mutations in the sarcomeric proteins in the myocardium (Maron and Maron 2013). It has been reported that patients with HCM are at high risk for atrial fibrillation, as well as heart failure and sudden death (Maron et al. 2018). Although HCM has been known to cause sudden death in youths, including athletes, it has also been reported as the cause of death in all age groups (Maron 2002). There are various mutations to the genes that encode the proteins of cardiac sarcomeres, which can lead to the onset of HCM at different time points over a life span (Maron et al. 2012; Vera et al. 2019). These mutations lead to hypercontractile sarcomeres by destabilizing the super-relaxed state of myosin heads, increasing myofilament activation, lowering efficient energy usage, and impairing Ca2+ cycling and sensitivity (Frey et al. 2011; Spudich 2019; Watkins et al. 2011). These underlying perturbations at the cellular level trigger the signaling pathways that induce cardiac hypertrophy to accommodate for the elevated contractile function of the heart. The hallmark feature of HCM is asymmetrical hypertrophy, especially in the septal wall, along with myocardial fibrosis and myofiber disarray (Maron 2018).

Computer and mathematical modeling of cardiac G&R has seen significant developments since its emergence nearly 30 years ago (Rodriguez et al. 1994). Computational cardiac G&R models have the potential to enhance our understanding of the complex interaction/behavior of how living systems adapt, especially when they are validated with experimental data collected at multiple scales. This is accomplished by developing mathematical relations between the underlying stimuli (e.g., mechanical signals) and the potential outcomes in the geometry and function of the heart (e.g., LV wall thickening, LV chamber dilation, myofiber disarray, hypercontractility). These computational models have helped to quantitatively investigate the effects of different hypotheses, such as the choice of mechanical stimuli (Mojumder et al. 2021; Rondanina and Bovendeerd 2020a) and the reversal of cardiac hypertrophy (Lee et al. 2015), on the hypertrophic behavior of the heart. With recent developments in cardiac G&R models, along the other computational models of the heart, it has been predicted that we will have comprehensive patient-specific models of the heart within the next decade (Peirlinck et al. 2021).

The objective of this review is to provide an overview of the current state of the art in computational modeling of cardiac G&R and discuss how the current models can be improved before implementation into personalized models for clinical use. To serve this purpose, in the “Current computational models of G&R” section, we summarize the most common computational models of cardiac G&R, including volumetric growth of the LV and myofiber remodeling. In the “Limitations of current models” section, we consider the limitations of the current models that need to be addressed. Finally, in the “Future perspectives” section, we discuss the future perspective of the field and explain how computational models can improve patient care in the future.

Current computational models of G&R

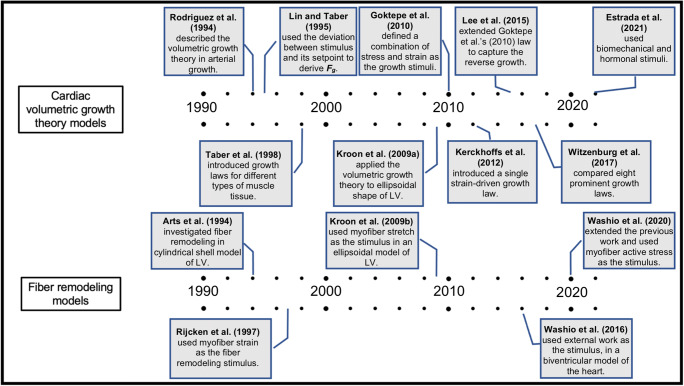

Computational models have been extensively developed and applied to simulate cardiac G&R (Fig. 1). In the following subsections, we recapitulate the key findings of current computational modeling of cardiac G&R.

Fig. 1.

Highlights on computational modeling of cardiac growth, based on volumetric growth theory and fiber remodeling, throughout the last three decades.

Volumetric growth theory

One of the most prevalent frameworks in modeling growth is “volumetric growth theory.” Utilizing the idea of a multiplicative decomposition of the deformation gradient F from continuum plasticity, Rodriguez et al. (1994) proposed splitting the deformation gradient as:

| 1 |

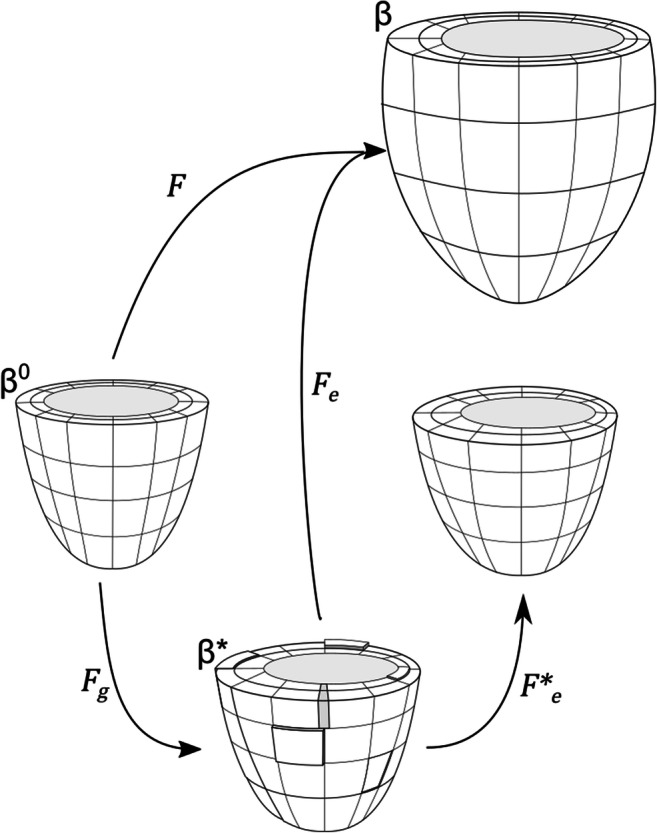

In this way, local changes in mass can be specified directionally via the inelastic growth tensor Fg as shown in Fig. 2. Applying Fg maps the reference configuration β0 to an intermediate configuration β∗ due to the stress-free removal or addition of material. Conventionally, addition in the fiber direction represents the serial addition of sarcomeres, while addition in the sheet and sheet normal directions represents the parallel addition of sarcomeres. In general, however, β∗ is not guaranteed to be “kinematically” compatible, meaning that gaps and overlaps can form. Compatibility is restored by applying an elastic deformation Fe* that restores continuity in the absence of any external loads, which can produce residual stresses (i.e., non-zero stresses without the presence of external load). In fact, this framework has been used to model the existence of residual stresses observed in vivo (Alastrue et al. 2007; Genet et al. 2015; Skalak et al. 1996). The total current configuration β is achieved by applying Fe to the intermediate configuration β∗. As growth occurs, Fe is altered, changing the stress response of the tissue for a given load.

Fig. 2.

Schematic showing how Fe, Fg, Fe*, and F map between configurations in volumetric growth theory. Ultimately F maps from the reference configuration β0 to the loaded, grown, and deformed configuration β. Fg maps from β0 to β∗ representing the stress-free removal or addition of material. This configuration is not necessarily compatible, as shown via discontinuities and overlaps here. Compatibility is restored via Fe* to a new unloaded geometry. Finally, Fe maps from the incompatible grown configuration β∗ to the final loaded configuration β.

This framework was originally used extensively in modeling arterial growth (Kuhl et al. 2007; Rachev et al. 1998; Rodriguez et al. 2007; Saez et al. 2014; Taber 1998b) and growth in the developing heart (Lin and Taber 1995; Ramasubramanian et al. 2008; Ramasubramanian and Taber 2008; Taber 1998a; Taber and Chabert 2002). Lin and Taber (Lin and Taber 1995) introduced the evolution of Fg as a differential equation involving the deviation of a growth stimulus from its homeostatic value. The first application of this framework to the geometry of a ventricle was by Kroon et al. (2009a). This work simulated inhomogeneous growth in 3D and extended the framework by updating the reference configuration incrementally as growth occurs. This led to steady-state growth in which the growth stimulus (deviation of end-diastolic myofiber strain from a homeostatic value) decreases as a steady-state configuration is reached.

Much of the focus since has been on the development of constitutive growth laws that govern the formulation of Fg. The question of what stimulus/stimuli is the driver of growth is still debated (Omens 1998), but conventionally, cardiac growth models use either stress, strain, or some combination of the two as their stimulus for driving the evolution of Fg. Grossman et al. (1975) found that peak systolic wall stress was consistent between normal hearts and those that experienced concentric or eccentric growth, leading to a hypothesis that fiber stress is a stimuli for growth. Stress-regulated growth has been used to successfully model cardiac growth in response to hypertension (Rausch et al. 2011) and myocardial infarction (Klepach et al. 2012) and recently to analyze the effects hypertrophy has on the electromechanics of the LV (Del Bianco et al. 2018).

Though Grossman’s hypothesis supports stress as a valid mechanical stimulus, Emery and Omens (1997) found that diastolic stresses remain elevated during growth, but end-diastolic fiber strains return to normal, suggesting that strain may be the dominant growth stimulus in response to volume overload. Guterl et al. (2007) further support strain as the regulator for cardiac growth after experiments on long-term cultured right ventricular papillary muscles showed that systolic stress played no role in the observed growth. Kroon et al. (2009a) used end-diastolic strain in their work to model growth during diastolic loading, comparing approaches that utilized either fixed or updated reference configurations. Kerckhoffs et al. (2012) proposed a strain-driven growth law that was able to qualitatively capture growth in response to both pressure and volume overload with a single set of growth parameters. This work was extended in 2018 by Witzenburg and Holmes (2018), connecting Kerckhoffs’ growth law to a compartmental model of the heart, which in turn was coupled with a circulatory model. They were able to quantitatively match multiple independent sets of growth data for pressure and volume overload as well as growth in response to myocardial infarction. In 2015 and 2016, Lee et al. (2015, 2016b) extended the framework proposed by Göktepe et al. (2010), using a strain-based growth law to predict the reversal of growth, as well as growth, integrating it into an electromechanical model of the heart. Genet et al. (2016) incorporated a strain-based growth law in a four-chamber model of the heart, predicting growth and also secondary effects such as valvular position and papillary muscle position. Recent studies on strain-driven growth include modeling forward and reverse growth due to cardiac dyssynchrony (Arumugam et al. 2019), incorporating multiscale and machine learning to analyze the predictive power of a strain-based growth model (Peirlinck et al. 2019), and incorporating an evolving set point to better predict growth reversal (Yoshida et al. 2020). Some works used a combination of stimuli for deriving their growth model. Göktepe et al. (2010) pre-selected the stimulus, using strain for eccentric growth and stress as the stimulus for concentric growth. Similarly, Berberoğlu et al. (2014) switched between stimuli when modeling cardiac dysfunction in grown hearts.

Recent works have focused more heavily on trying to deduce the best stimulus/combination of stimuli to accurately produce stable growth as well as incorporating more multiscale, mechanistic features. Witzenburg and Holmes (2017) compared eight existing growth laws in response to cyclical stretches meant to represent either volume or pressure overload. They found that only two models (Kerckhoffs et al. 2012; Lin and Taber 1995) could reach a steady-state growth in both simulations and also highlighted the need to accurately capture evolving hemodynamics. In a recent work, Mojumder et al. (2021) showed that myofiber stress has a better correlation with the predicted concentric growth in response to pressure overloading using finite element modeling. Though not utilizing the volumetric framework, the studies performed by Rondanina and Bovendeerd (2020a, 2020b) concluded that (1) using at least one stress-based stimulus and (2) accurately modeling hemodynamics, specifically hemodynamic feedback to maintain mean arterial pressure, yield a model that is able to capture growth while maintaining realistic pump function. Estrada et al. (2021) and Yoshida et al. (2020) have recently incorporated cell-level hormone networks into their models of growth. As with most modeling, the shift from phenomenological towards mechanistic models will drive the field forward regarding predictive capability and may shed light on the most relevant growth stimuli, mechanical or otherwise.

Constrained mixture theory

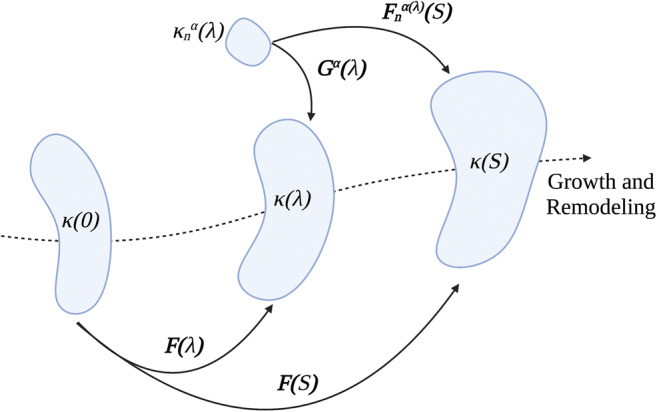

Another approach for modeling of G&R is based on the constrained mixture theory (Humphrey JDaR 2002). According to this theory, the different constituents of tissue (cell, collagen, elastin, etc.) have distinct production/turnover rates and are constrained to deform within a single continuum mixture. The key hypothesis in this theory is that deposition of new material for each constituent occurs at the current configuration. According to the constrained mixture theory, constituent α deposits in a preferred direction at time λ ∈ [0, s] with a homeostatic stretch or pre-stretch of Gα(λ). If we assume F(s) and F(λ) are the deformation gradient of the whole continuum from a reference configuration at t = 0 to the configurations at time s and λ, respectively, then F(s)F(λ)−1 accounts for deformation gradient of the whole continuum from time λ to the current configuration at time s. Consequently, the deformation gradient of constituent α from time λ to the current configuration at time s can be formulated as (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Schematic showing finite deformation of a soft tissue according to constrained mixture model. Each constituent α = 1, 2, …, n deposits within the current mixture with a preferred deposition stretch Gα(λ) at G&R time of λ ∈ [0, s] from its stress-free configuration of . However, the constituent α may have a different deformation because all constituents are constrained to deform within a single continuum from the configuration at time of λ, κ(λ), to current configuration at time s, κ(s). Constituent-specific deformation gradient associated with constituent-specific stored energy function then can be formulated as .

Constrained mixture theory has been widely used in G&R models of arteries and vessels (Cyron et al. 2016; Valentin et al. 2013). There are several reviews on constrained mixture-based G&R model, where the bulk of its mathematical background are summarized. For example, Ateshian and Humphrey (2012) reviewed the application of this theory to various illustrations of biological G&R and identified open problems in the field. Valentin and Holzapfel (2012) summarized the core hypotheses integrated in constrained mixture theory of arterial G&R and recapitulated the remarkable findings. In the most recent study, Humphrey (2021) reviewed the constrained mixture theory introduced 20 years ago and explored its application in various types of vascular conditions.

Compared to volumetric growth theory, constrained mixture modeling is computationally more complex because it needs to track the evolution of each constituent’s stress-free configuration at each growth time step. Therefore, constrained mixture models have been mainly used on arterial G&R by assuming simple 2D geometry, e.g., thin-wall membrane (Baek et al. 2006; Valentin and Holzapfel 2012). To the best of our knowledge, no study has implemented the constrained mixture theory into cardiac G&R, and only a few studies have implemented 3D finite element models of arterial G&R based on constrained mixture theory (Latorre and Humphrey 2020; Mousavi and Avril 2017; Valentin et al. 2013).

Although constrained mixture theory is not routinely employed in the field of cardiac G&R, Yoshida and Holmes (2021) suggested that this approach might address some limitations of volumetric growth theory for cardiac G&R. First, they observed that as the new constituent replaces the old one with a unique turnover rate, the homeostatic configuration evolves in such a way that the new stage is fundamentally different from the original ungrown stage. The authors suggested that the evolution of the homeostatic configuration in constrained mixture theory might be a better suited solution for evolving the growth setpoint, which was already suggested to be a potential solution for capturing the reversal of cardiac growth when the pressure overloading is removed (Yoshida et al. 2020). Second, they suggested that this approach might have some advantages in the modeling of myocardial fibrosis since it allows the modeling of different constituents of cardiac tissue. Hence, this approach will potentially address some limitations of kinematic (volumetric) growth theory and enhance the computational modeling of cardiac G&R.

Fiber remodeling

The development of organized myofiber architecture, from randomly distributed myocytes in embryonic cardiac jelly to a compact myocardium in the embryonic heart, is not well understood. The myofiber orientation changes at different stages of the maturation process. In a normal chick embryo, myofibers are oriented circumferentially in the secondary trabeculation stage, whereas in the tertiary trabeculation stage, myofibers in the epicardium of compact myocardium shift to a more longitudinal direction producing a transmural gradient in myofiber orientation (Sedmera et al. 2000; Tobita et al. 2005). The subsequent orientation of myofibers within the adult heart wall is complex, yet highly organized. The organization follows a helix-like pattern, where the helix angle varies transmurally ranging from +60° at the subendocardium to −60° at the subepicardium (Bovendeerd 2012; Ennis et al. 2008; Geerts et al. 2002; Nielsen et al. 1991; Streeter Jr. et al. 1969). This orientation of myofibers is similar in various species (Bovendeerd 2012).

Cardiac mechanics, in terms of homogeneous distributions of active muscle fiber stress, strain, shear deformation, and muscle fiber shortening, is sensitive to transmural variation of myofibers across the wall of the heart (Bovendeerd et al. 1992; Bovendeerd et al. 1994; Rijcken et al. 1997; Rijcken et al. 1999; Wang et al. 2016; Zhang et al. 2015). For example, Tobita et al. (2005) reported an alteration in transverse myofiber angle due to variations in mechanical load in the embryonic human heart. Myofiber disarray has also been observed in cardiac diseases such as hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (Finocchiaro et al. 2021) and myocardial infarction (Zimmerman et al. 2004). In order to investigate the mechanism of regional dysfunction caused by myofiber disarray, Usyk et al. (2001) developed a mathematical model using animal specific geometry. By increasing the myofiber angular dispersion and reducing sarcomere length in their model, they showed that focal changes in the microstructural properties of the disarrayed myocardium are directly responsible for the patterns of regional dysfunction in the LV.

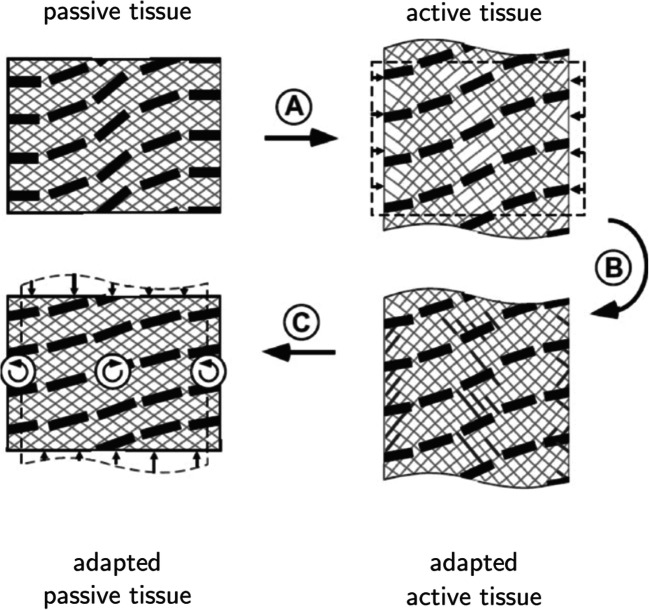

Several mathematical models have been proposed to describe myofiber reorientation in the heart. In one of the earliest models, Arts et al. (1994) developed a heart model consisting of adjoining concentric cylindrical shells. The fiber orientation in each shell was homogeneous, and the transmural gradients were represented as stepwise changes from shell to shell. In this model, with the adjustment of global contractility, the LV pressure was matched with a reference pressure. The adaptation of myofiber orientation in each shell occurred through regional optimization of the deviation of the sarcomere length at the beginning of ejection and the sarcomere shortening during systole from their corresponding prescribed reference points. The predicted transmural variation in myofiber orientation was consistent with experimental data. In another model developed by Kroon et al. (2009b), the local myofiber adaptation was driven by the pure deformation (excluding rigid body rotation but including shear deformation) in order to achieve the orientation of minimal fiber-cross fiber shear strain during a cardiac cycle. They assumed that the loss of structural integrity between extracellular matrix (ECM) and myofibers, induced by systolic myofiber contraction, is recovered by the continuous ECM turnover leading to the rearrangement of connections between myocytes, such that forces between myofibers and ECM would be reduced (Fig. 4). They described the evolution of the fiber orientation by:

| 2 |

Fig. 4.

Schematic showing remodeling of myofiber orientation based on the remodeling law proposed by Kroon et al. (2009b). Transition (A) describes the deformation of tissue under contractile loading. Transition (B) shows how the contractile deformation results in local loss of matrix integrity. Transition (C) depicts the restoration of matrix that remodels the orientation of myofibers in the new passive state towards the orientation of myofibers in the active state. This figure is adopted from Bovendeerd with permission (Bovendeerd 2012).

where and represent the fiber direction in the unloaded reference and current state of the model, respectively, κ is a time constant, and F, R, and U denote the deformation gradient tensor, the rotation tensor, and the stretch tensor that excludes rigid body rotations, respectively. The implementation of this adaptation law on a truncated ellipsoid model of a dog heart yielded myofiber orientations that were consistent with experimental observations. However, further implementation of this adaptation model on human hearts could not predict the circumferential-radial shear strain compared with experimental data (Kroon 2009). By extending the LV mechanics model with a physiological sequence of activation and triaxial active stress development, Pluijmert et al. (2014) developed a combined model of LV mechanics and fiber orientation remodeling, which could predict the physiologic data for the circumferential-radial shear strain and myofiber strain.

Washio et al. (2016) recently developed a multiscale biventricular model and investigated the optimization of myofiber reorientation in response to maximum local mechanical indicators, i.e., the workloads and impulses. In their model, the distribution of fibers was represented by the branching fiber structure at each point by a central unit vector and n multi-directionally distributed unit vectors. While both optimization approaches achieved rapid convergence of the fiber structure, quantitative analysis showed that impulse optimization produced better results than workload optimization. Furthermore, this work was extended to investigate fiber remodeling in an infarcted human heart (Washio et al. 2020) by assuming active fiber stress as the stimulus. Starting from a nearly flat initial fiber distribution, their model predicted fiber remodeling near an infarcted region of the LV that agrees with experimental observations.

Limitations of current models

The current state of the art for cardiac G&R has certain limitations, which have hindered its use in clinical applications. In order to implement computational modeling into clinical care and improve patient outcomes, these limitations need to be addressed. Several of these key limitations are outlined as follows.

Contractile model of the heart

Several models of cardiac G&R (Göktepe et al. 2010; Klepach et al. 2012; Kroon et al. 2009a; Lee et al. 2015; Lin and Taber 1995) have only operated under passive loading of the LV (diastole) and neglected the active contractile behavior of myocardium during systolic ejection. In these models, the ventricular pressure was incrementally increased up to the end-diastolic pressure and then was kept constant to allow the ventricle to grow. Another group of works evaluated cardiac G&R during the full cardiac cycle by simulating both passive and active phases of cardiac function. Most of these models (Arts et al. 2005; Arumugam et al. 2019; Kerckhoffs et al. 2012; Lee et al. 2016b) utilized phenomenological Hill-type models of contraction to simulate the LV during systole. This model of contractile mechanics defines the magnitude of active force using a length-dependent force generation model (Guccione and McCulloch 1993; Guccione et al. 1993). Other studies (Estrada et al. 2021; Witzenburg and Holmes 2018) have used a time-varying elastance model of the ventricle (Beyar and Sideman 1984; Santamore and Burkhoff 1991) to simulate the full cardiac cycle. This model essentially assumes an exponential end-diastolic pressure-volume relationship and a linear end-systolic pressure-volume relationship. The pressure-volume relationship for any points between these two is described by a smooth time-varying function. Rondanina and Bovendeerd recently investigated the effects of different mechanical stimuli on cardiac growth (Rondanina and Bovendeerd 2020a; Rondanina and Bovendeerd 2020b). In this case, the contractile behavior of the ventricle was modeled by a one-fiber model of cardiac function (Bovendeerd et al. 2006) and was used to relate mechanics at the organ level, via ventricular pressure and volume, to mechanics at the tissue level, via myofiber stress and sarcomere length.

Generally, the myocardium has two types of mechanical behavior, namely passive and active. The passive mechanical properties of myocardium are primarily related to collagen and titin that control the passive tension of the myocytes during ventricular diastole. Titin is a large protein that spans from the Z disk to the M line of sarcomeres (Cazorla et al. 2000), while collagen, as part of the ECM, surrounds and interconnects cardiac myocytes, muscle fibers, and the coronary microcirculation (Janicki and Brower 2002). The active contractile mechanical properties of myocardium are related to the crossbridge cycling of myosin heads on the thick filament with actin binding sites on the thin filament, which drives the systolic behavior of the LV. This interaction is part of a cascade of multi-physics events that enable contraction. Briefly, an action potential leads to depolarization of the cell membrane, which activates Ca2+ channels and allows entry of Ca2+ into the cell. Ca2+ entry triggers the release of Ca2+ from the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) and increases the Ca2+ concentration within the cell (Bers 2002). Elevated Ca2+ concentration leads to the binding of Ca2+ to the myofilament troponin-C, which moves the tropomyosin on the surface of the thin myofilament. This exposes more available binding sites for attachment of myosin heads on the thick filament, which then generate the power stroke. For more insights on the regulatory system of myofilaments, we refer to the review by Solis and Solaro (2021).

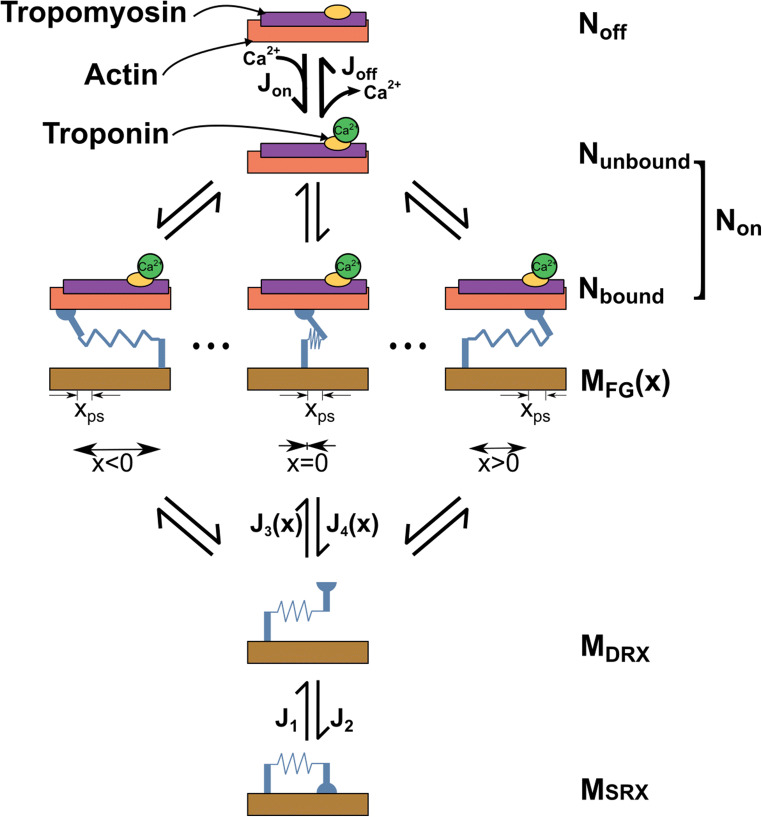

Although it is well accepted to simplify the sophisticated biological mechanisms of the beating heart in computational modeling, the contractile function is an integral process of the heart and should be modeled more accurately to allow the cardiac G&R to occur throughout the cardiac cycle, not just at certain timepoints such as end-diastole or end-systole. To our knowledge, none of the contractile models used in the current state of the art in cardiac G&R truly simulates the sliding of myofilaments based on the Huxley crossbridge formation (Huxley 1974) in the myosin level. To overcome this limitation, there are several models of sarcomere mechanics that could be employed, which describe the crossbridge cycling of myosin and actin binding sites using mathematical definitions (Campbell 2014; Campbell et al. 2018; Rice et al. 2008). These models typically assume a certain number of conformation states that myosin heads or binding sites can switch between throughout the contraction cycle based on the Ca2+ activation of actin binding sites. An example of a kinetic scheme is shown in Fig. 5. The transition between these states is usually described by a system of ordinary differential equations (ODEs) that depend on the present population of myosin heads or binding sites at each state, and transition rate factors. The sarcomere contraction model proposed by Campbell et al. (2014; 2018), which captures length-dependent activation, cooperativity between thick and thin filaments, and the strain-dependent behavior of cross-bridges, has successfully been implemented into several finite element models of LV mechanics. Zhang et al. (2018) implemented this model of contraction into a finite element model of a rat LV, where the myosin heads were only able to move between the disordered relaxed (DRX) and force-generating (FG) states. They showed that by considering key features of ventricular relaxation, they could predict both the global function and regional deformation of the LV compared to measured data. Mann et al. (2020) recently enhanced that model by adding the super-relaxed (SRX) state for myosin heads and concluded that the force-dependent recruitment from the myosin SRX state increased the end-systolic pressure-volume relationship. This level of sarcomere mechanics has yet to be implemented in models of cardiac G&R. Although these types of contraction schemes can increase the complexity of computational models, cardiac G&R would occur under more realistic conditions that can quantitatively explain the relation between the pathological cardiac diseases observed at the organ level and cellular events at the myosin level.

Fig. 5.

Kinetic scheme. Sites on the thin filament switch between states that are available (Non) and unavailable (Noff) for cross-bridges to bind to. Myosin heads transition between a super-relaxed detached state (MSRX), a disordered-relaxed detached state (MDRX), and a single attached force-generating state (MFG). J terms indicate fluxes between different states.

Hemodynamic feedback control

Valvular disorders, such as aortic stenosis and mitral regurgitation, change the ventricular loading and cardiac function, but the arterial pressure and cardiac output normally remain unchanged (Everett et al. 2018; Gotzmann et al. 2019; Lloyd et al. 2017). Current approaches to cardiac G&R have mainly focused on the geometry of the LV and paid less attention to hemodynamic feedback. The baroreflex loop is an important short-term hemodynamic feedback mechanism that maintains the arterial pressure by adapting the cardiac contractility, heart rate, and vascular tone to acute changes in the ventricular loading. Current models are generally performed under constant heart rate and contractility assumptions, with no mechanisms for preserving the arterial pressure. The absence of hemodynamic feedback has been viewed as the potential cause of inaccuracy in certain model predictions of cardiac geometry and function, when compared to measured data. For example, Kerckhoffs et al. (2012) reported a mismatch between the calculated peak LV cavity pressure and that measured in experiments and posited that it could be due to the absence of fast baroreflex responses in their model. Recently, Rondanina and Bovendeerd (2020a) investigated the effect of mechanical stimulus signals on cardiac growth using a growth law lumped with a compartmental model of cardiovascular function. Their model erroneously predicted a 20 to 40% reduction in mean arterial pressure and cardiac output in response to aortic stenosis, aortic regurgitation, and mitral regurgitation. In their next study, Rondanina and Bovendeerd (2020b) incorporated a model of baroreflex feedback, along with their growth model, and suggested that using a mixed stress-strain growth model in conjunction with a model of hemodynamic feedback could capture more realistic cardiac growth and preserved cardiac pump function.

Reverse growth

The reversal of pathological hypertrophy is a primary goal of clinical interventions such as mitral valve replacement (Acker et al. 2014), aortic valve surgery (Treibel et al. 2018), implementation of LV assist devices (Birks et al. 2020), cardiac resynchronization (Stellbrink et al. 2001), and bioinjection hydrogel treatment (Lee et al. 2013; Wang et al. 2017; Wang et al. 2018). These interventions essentially normalize the ventricular loading by reducing overloading conditions, which can improve function and positively alter ventricular geometry, ultimately leading to more favorable clinical outcomes. In terms of simulating the onset of pathological hypertrophy, computational models of cardiac G&R enlarge the ventricular geometry when the underlying stimulus is higher than the homeostatic level. On the other hand, it is expected that during the reversal of an adverse event, when the stimulus signals are below the homeostatic level, the ventricle would shrink in order for the mechanical stimuli to return to their setpoint level.

However, current computational models have focused more on the prediction of “forward” cardiac growth, and only a few works have tried to study the “reverse” of cardiac growth. Lee et al. (2015) modified the eccentric growth law proposed by Göktepe et al. (2010) and could successfully capture the “reverse” growth for a thick-walled cylindrical tube and realistic LV geometry under certain types of loading. Arumugam et al. (2019) implemented a similar growth law into a biventricular FE model of the heart and used maximum elastic myofiber stretch over a cardiac cycle as the sole driving signal of their growth law. They lumped their growth model with an electromechanics model of the heart and showed that the model predicts growth in the LV chamber size and septal wall, but reversal of growth for RV chamber size and LV free wall in response to mechanical dyssynchrony. Recently, Yoshida et al. (2020) adopted the growth law proposed by Kerckhoffs et al. (2012) into a biventricular FE model of the heart and investigated the regression of concentric growth due to the removal of pressure overloading. Although this growth law was shown in a study to perform the best in predicting cardiac hypertrophy in comparison to seven other growth laws (Witzenburg and Holmes 2017), it was not able to predict the reversal of growth when the pressure overloading was lifted. The authors suggested that using an evolving growth setpoint might potentially address the inability of current models to predict the reversal of growth.

Fiber remodeling validation

Computational models of fiber remodeling face several challenges and limitations, from which we briefly describe two of the most prevalent. First, due to limitations in current measurement techniques, there is a large variation in the experimental data that have been reported for fiber orientations. For example, an estimated variation of ±10° for histological measurements and ±6° for magnetic resonance diffusion tensor imaging has been reported (Agger et al. 2020; Geerts et al. 2002). Therefore, the validation process of computational fiber remodeling has been challenging. Second, significant simplifying assumptions have been made in current fiber remodeling approaches, in terms of model geometry, tissue properties, and boundary conditions. Pluijmert et al. (Pluijmert et al. 2014; Pluijmert et al. 2017; Pluijmert et al. 2013; Pluijmert et al. 2012) investigated the impact of simplified modeling assumptions by adding various levels of complexity (triaxial active stress, asynchronous activation, biventricular geometry, etc.) to their initial model of fiber remodeling and recorded the changes in fiber evolution and global cardiac function. However, they could not address the observed mismatch between the model prediction and measured experimental data. This might also emphasize the importance of a multiscale approach for fiber remodeling to capture the effects of cardiac diseases at the organ level based on the remodeling of fibers at the cellular level.

Clinical application

In addition to the model limitations described above, there are other types of limitations that have hindered the field from being applied to clinical care. These limitations are more general and are applicable to most multiscale models of the heart, including growth and remodeling.

Firstly, mathematical models of cardiac G&R are computationally expensive. The finite element method is widely used to simulate the mechanics of the heart by numerically solving partial-differential equations for each element in both time and space. The solution then needs to be integrated over the entire domain (whole geometry of the heart) at each time step. This process for 3-dimensional models that are non-linear and time dependent is computationally intensive and time-consuming, since it requires multiple hours to simulate a single cardiac cycle (Dabiri et al. 2020). Secondly, these models, in general, require parameter identification and model calibration that add more sophistication in their application. Thirdly, computational models usually include uncertainties and variabilities that have limited their clinical application (Mirams et al. 2016). These uncertainties need to be quantified and propagated through different scales using statistical approaches, such as Bayesian inference and Gaussian process regression. Fourthly, performing computational models of cardiac G&R on the population scale is labor intensive. The number of trained technicians who can perform the computational simulations in comparison to the large pool of patients across the nation is lower, meaning that the ratio of demand over capacity is much larger than unity. Consequently, performing full patient-specific models of cardiac G&R for patients that need real-time results is not yet practical in the health care system.

Model calibration and validation

The accuracy of computational models of cardiac G&R can be assessed when they are calibrated and validated via experimental data. Animal models and clinical data from human patients are the main sources of measured experimental data. Animal models are more often used than patient data, since they are more available, and it is possible to conduct invasive measurements on them. On the other hand, acquiring data from human patients is more restricted, and only procedures that are part of standard care, including non-invasive imaging techniques or measuring clinical data, are typically used.

Animal models provide the opportunity to validate computational models in different scales. Organ-level data are usually acquired using non-invasive imaging devices such as echocardiography or cardiac magnetic resonance images (MRI). Imaging data are mainly utilized to construct the patient-specific geometry of the LV but can also provide information about myocardial deformation, such as displacement and strain. The predicted LV volume at end-diastole and end-systole, stroke volume, ejection fraction, and wall thickness can then be validated with the imaging data. This is also the case with regional strain patterns that are predicted by the model and then compared to in vivo measurements (Mann et al. 2020; Zhang et al. 2018). Calculated myofiber remodeling can also be evaluated against the measured values from magnetic resonance diffusion tensor imaging (MR-DTI) (Watson et al. 2018). At the cellular level, predicted hypertrophy is validated ex vivo by measured data for myocyte width and length, sarcomere number and length, and fibrosis from collected ventricular tissue samples

Model calibration is the adjustment of model parameters such that the model prediction best fit the data. However, the number of parameters in G&R models can be large, which in turn complicates the process of model calibration. A solution to this complexity is to define simplified relations between them to reduce the number of free parameters (Lee et al. 2016a). One of the main free parameters in growth laws is growth rate or gain factor. This parameter controls the speed of the growth algorithm and is usually adjusted in a way to fit the growth rate from the experimental data. Once the G&R model is calibrated, it needs to be validated against an independent set of measured data that has not been used in the calibration process. The process of model validation can be governed in two ways. First, the predicted results from computational models of cardiac G&R can be qualitatively compared with the experimental data by overlaying them in a single figure. A second approach is to quantitatively calculate the error between the computed results and measured ones over a range of inputs to quantify the level of agreement. This approach comprised statistical methods referred to as validation metrics. For more insights on different approaches for validation metrics, we refer to the review by Oberkampf and Baroneb (2006).

Future perspectives

Multiscale modeling of cardiac G&R

Despite the limitations listed above, current models have done a reasonable job in simulating cardiac G&R due to extrinsic mechanical conditions such as valvular disorders (Kerckhoffs et al. 2012; Rondanina and Bovendeerd 2020a; Witzenburg and Holmes 2018), systemic and pulmonary hypertension (Rausch et al. 2011), and myocardial infarction (Klepach et al. 2012; Witzenburg and Holmes 2018). However, cardiac G&R can occur due to intrinsic events, such as altered hormone level or mutant sarcomeric proteins, which have not been thoroughly investigated in the field of computational biomechanics. Multiscale modeling has the potential to solve many of the issues with current cardiac G&R models and will most likely be the focus of cardiac biomechanics in the near future.

Inspired by the field of systems biology, there are several models that simulate the complex network of signaling pathways within the cell, which can predict cell growth in response to altered hormones. Ryall et al. (2012) proposed a model of hypertrophic signaling pathways to predict the change in cell area of a cardiomyocyte in response to hormonal alteration and biomechanical stretching. Frank et al. (2018) recently modified this model and validated it with in vivo data from multiple mouse models. Yoshida and Holmes (2021) investigated pregnancy-induced cardiac growth by coupling a signaling pathway network that could predict the cell-level hypertrophy with a compartmental model of the rat heart in a circulatory system. Ultimately, they simulated the pregnancy condition by developing volume overload in conjunction with a surge in hormone levels. Their model successfully predicted cardiac growth in response to pregnancy that is consistent with experimental data and concluded that most of the growth, especially during the first half of pregnancy, was due to an early rise in progesterone. Estrada et al. (2021) went further and proposed a multiscale model of cardiac hypertrophy by adopting this approach into a finite element model of a LV, to investigate the prediction of concentric hypertrophy in response to transverse aortic constriction (TAC), which includes both elevated afterload along with the change in hormone levels. Interestingly, they concluded that the hormonal inputs had a larger effect than the mechanical signals in the prediction of hypertrophy due to TAC. Both studies emphasized the importance of multiscale modeling of cardiac growth wherein they could monitor the interaction of both mechanical and hormonal stimuli in the development of cardiac growth.

Multiscale modeling of cardiac G&R could also be beneficial in quantitatively studying familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM). This type of genetic heart disease—known as an intrinsic cause of cardiac hypertrophy—is mainly induced by mutant sarcomeric proteins. Different types of mutations associated with either the thick or thin myofilaments can cause HCM. Although the underlying mechanism of mutant genes and development of HCM is not completely clear, numerous mutations in the genes of sarcomeres have been identified that lead to HCM. Genetic mutations associated with the myosin heavy chain (MYH7) and myosin binding protein C (MYBPC3) are the most common cause of HCM (Maron and Maron 2013; Toepfer et al. 2019). In general, these mutations affect the motor function of myosin heads, potentially destabilizing the SRX state and increasing the number of myosin heads that can interact with actin. Another outcome of thick filament mutations is the increase of energy required for myosin ATPase, which in turn can reduce the activity of other ATP-consuming processes such as sarcoendoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase (SERCA) (Watkins et al. 2011). HCM mutations can also occur in thin filament genes including cardiac troponin T (TNNT2), cardiac troponin I (TNNI3), α-tropomyosin (TPM1), and cardiac actin (ACTC). The thin filament-associated mutations ultimately lead to alterations in the Ca2+ balance within the cell by increasing the sensitivity of troponin C for calcium (Robinson et al. 2007; Watkins et al. 2011). Eventually, all of these molecular-level perturbations alter the signaling pathways (Nakamura and Sadoshima 2018) and develop hypercontractile sarcomeres (Spudich 2019) that lead to asymmetrical hypertrophy in the septal wall, along with myofiber disarray.

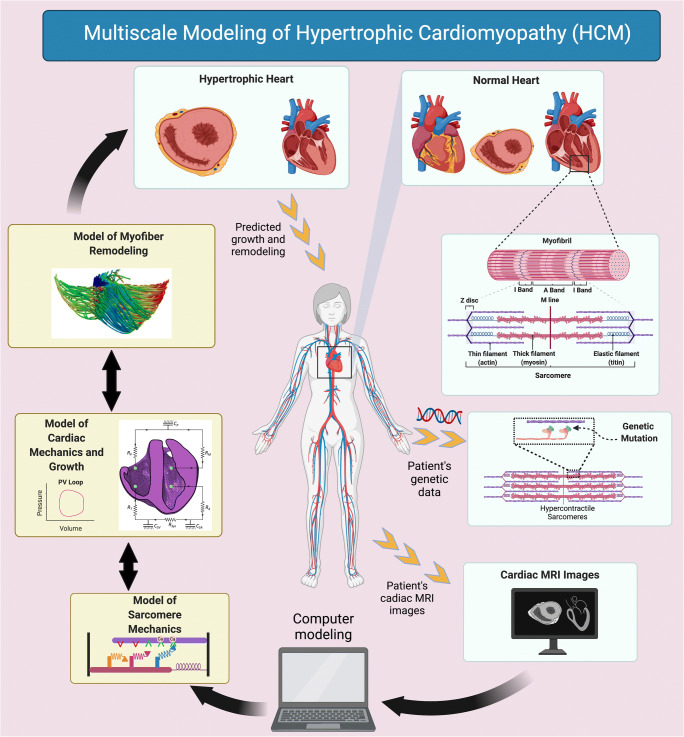

To date, no computational models have studied cardiac G&R in response to HCM. Here, we briefly hypothesize two potential solutions for modeling of HCM across multiple scales, from molecular level to organ level. The first solution to fill this gap is to lump a model of the signaling pathway network, wherein it represents the interaction of pathological biochemical stimuli involved in HCM, with a mechanical model of cardiac G&R. In this approach, the effects of mutant genes, which disturb the signaling pathway within the myocardial cell, can be observed on larger scale events such as LV hypertrophy and myofiber remodeling. However, since HCM is a disease of the sarcomeres, it is important to simulate the mechanics of sarcomeres in a biologically relevant way and mimic the effects of mutant genes at the molecular level. Therefore, the second solution could be utilizing a mechanistic model of sarcomeres, rather than phenomenological models, for simulating the contractile behavior of the heart. As described in the “Limitations of current models” section, coupling a model of sarcomere mechanics, which simulates the interaction of myosin heads and actin biding sites to generate the active contractile force, with a model of cardiac G&R could be very beneficial. Due to the ability of these models, perturbations in molecular-level events such as an increased number of accessible heads to interact with actin binding sites, elevated ATPase, or even perturbed Ca2+ handling can be quantitatively predicted (Campbell et al. 2020). Thus, implementing a growth law that utilizes these perturbations in molecular events as the stimuli to predict cardiac growth, in terms of ventricular size, would be a remarkable success in the field of cardiac biomechanics. In addition to growth of the LV, hypercontractile sarcomeres will lead to the development of myofiber disarray in the myocardium of HCM patients (Ariga et al. 2019). In the study by Avazmohammadi et al. (2019), the authors emphasized that multiscale modeling of the heart was needed to better understand the myofiber remodeling that was observed in the presence of pulmonary arterial hypertension. With this in mind, the “prospective” multiscale model of HCM (Fig. 6) can be completed by incorporating a model of myofiber reorientation as well as volumetric growth. Consequently, the effect of key perturbations in molecular and cellular events on the growth of the LV and myofiber reorientation/disarray can be predicted simultaneously. This level of multiscale modeling will also have the ability to simulate the effects of pharmaceutical interventions for treating HCM, such as small molecule therapeutics, which would be a milestone step in the field of cardiac biomechanics.

Fig. 6.

Multiscale patient-specific modeling scheme for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM). A patient’s genetic data drives the model properties of the sarcomere mechanics and determines the HCM mutations. Cardiac magnetic resonance images (MRI) form the patient-specific geometry of the heart for computational modeling. A multiscale model of HCM then predicts the progression of cardiac growth and remodeling (G&R) in response to specific mutations associated with HCM. The bi-ventricular scheme of the heart for “model of cardiac mechanics and growth” subfigure is adopted from Sack et al. with permission (Sack et al. 2018). The schematic subfigure for “model of myofiber remodeling” is adopted from Washio et al. with permission (Washio et al. 2016).

Machine learning and multiscale modeling of cardiac G&R

Although advances in multiscale modeling of living matter, such as cardiac G&R, can provide more insight on the underlying mechanisms, it can introduce more complexity into the computational models in terms of both physics and parameters (Alber et al. 2019; Raissi and Karniadakis 2019). That is why the fully patient-specific model of the heart seems theoretically possible, but practically computationally expensive and labor intensive, which has hindered the field from being applied to clinical care (Peirlinck et al. 2021). Machine learning is recognized as a powerful tool in the biological, biomedical, and behavior sciences that integrates multi-modality and multi-fidelity data to identify the correlation among different phenomena. However, this technique weakens when dealing with spare data (Alber et al. 2019). Physics-based models, such as multiscale models, have been found helpful to address this issue. Essentially, machine learning can be integrated with multiscale models to learn both the underlying mechanisms (physics) in terms of governing equations and boundary equations (Rudy et al. 2017), and the model parameters for a particular physics-based problem. On the other hand, multiscale models can utilize machine learning to identify the correlation, characterize the system parameters, and quantify the uncertainties between scales. Therefore, machine learning and multiscale models can mutually complement and benefit one another. In recent years, machine learning has been successfully integrated with patient-specific multiscale models of the heart and showed promising results in predicting LV mechanics (Buoso et al. 2021; Dabiri et al. 2020), cardiac activation mapping (Costabal et al. 2020), and risk predictions of sudden cardiac death (Shade et al. 2021).

In general, the concept of growth and remodeling of living matter is most applicable to the field of biomechanics, in conjunction with machine learning (Peng et al. 2021). Multiscale modeling of cardiac G&R, in particular, can benefit from being integrated with machine learning. At the basic research phase, machine learning and multiscale modeling can complement one another. Specifically, techniques from machine learning can identify the correlations for different growth stimuli from the measured (i.e., experimental and/or clinical) data, while multiscale modeling of cardiac G&R can assess the causality of the phenomena with the highest correlation (Alber et al. 2019). Secondly, the predictive power of growth laws can be quantified before being applied to clinical care cases. For instance, Peirlinck et al. (2019) quantified that their stretch-driven growth law can explain 52.7% of the changes in myocyte length in response to mitral regurgitation. Thirdly, the uncertainties from the experimental and clinical data can be quantified and then propagated throughout the physics-based computational models using techniques from machine learning, such as Bayesian inference and Gaussian process regression (Lee et al. 2020; Peirlinck et al. 2019). Fourthly, machine learning can learn the underlying dynamic system of cardiac G&R from the multiscale modeling and identify the system parameters such as growth factors and homeostatic level of stimuli signals, based on the trained dataset.

Ultimately, the full patient-specific multiscale models of cardiac G&R can be replaced by surrogate models through the integration of machine learning and multiscale models, which are computationally more efficient. These surrogate models use experimental, clinical, computational, and multi-modality imaging data from different scales and sources to predict the prognosis of cardiac G&R in response to various cardiovascular diseases. By moving the field closer to real-time predictive models, this event will be a big achievement towards the application of multiscale modeling in clinical cardiac care.

Code availability

Not applicable

Author contribution

Each author contributed equally to this review in terms of writing, editing, and figure generation.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health grant U01HL133359.

Data availability

Not applicable

Declarations

Ethics approval

Not applicable

Consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Acker MA, et al. Mitral-valve repair versus replacement for severe ischemic mitral regurgitation. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:23–32. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1312808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agger P, Omann C, Laustsen C, Stephenson RS, Anderson RH (2020) Anatomically correct assessment of the orientation of the cardiomyocytes using diffusion tensor imaging NMR Biomed 33:e4205 doi:10.1002/nbm.4205 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Akinseye OA, Pathak A, Ibebuogu UN. Aortic valve regurgitation: a comprehensive review. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2018;43:315–334. doi: 10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2017.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alastrue V, Pena E, Martinez MA, Doblare M. Assessing the use of the "opening angle method" to enforce residual stresses in patient-specific arteries. Ann Biomed Eng. 2007;35:1821–1837. doi: 10.1007/s10439-007-9352-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alber M, et al. Integrating machine learning and multiscale modeling-perspectives, challenges, and opportunities in the biological, biomedical, and behavioral sciences. NPJ Digit Med. 2019;2:115. doi: 10.1038/s41746-019-0193-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ariga R, et al. Identification of myocardial disarray in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and ventricular arrhythmias. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73:2493–2502. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.02.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arts T, Delhaas T, Bovendeerd P, Verbeek X, Prinzen FW. Adaptation to mechanical load determines shape and properties of heart and circulation: the CircAdapt model. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;288:H1943–H1954. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00444.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arts T, Prinzen FW, Snoeckx LH, Rijcken JM, Reneman RS. Adaptation of cardiac structure by mechanical feedback in the environment of the cell: a model study. Biophys J. 1994;66:953–961. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80876-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arumugam J, Mojumder J, Kassab G, Lee LC. Model of anisotropic reverse cardiac growth in mechanical dyssynchrony. Sci Rep. 2019;9:12670. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-48670-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ateshian GA, Humphrey JD. Continuum mixture models of biological growth and remodeling: past successes and future opportunities. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2012;14:97–111. doi: 10.1146/annurev-bioeng-071910-124726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avazmohammadi R, Mendiola E, Li D, Vanderslice P, Dixon R, Sacks M (2019) Interactions between structural remodeling and volumetric growth in right ventricle in response to pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Biomech Eng. 10.1115/1.4044174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Baek S, Rajagopal KR, Humphrey JD. A theoretical model of enlarging intracranial fusiform aneurysms. J Biomech Eng. 2006;128:142–149. doi: 10.1115/1.2132374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berberoğlu ES, H.O., Göktepe S. Computational modeling of coupled cardiac electromechanics incorporating cardiac dysfunctions. Eur J Mech - A/Solids. 2014;48:60–73. doi: 10.1016/j.euromechsol.2014.02.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bers DM. Cardiac excitation-contraction coupling. Nature. 2002;415:198–205. doi: 10.1038/415198a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berta E et al. (2019) Hypertension in thyroid disorders front endocrinol (Lausanne) 10:482 doi:10.3389/fendo.2019.00482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Beyar R, Sideman S. Model for left ventricular contraction combining the force length velocity relationship with the time varying elastance theory. Biophys J. 1984;45:1167–1177. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(84)84265-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birks EJ, et al. Prospective multicenter study of myocardial recovery using left ventricular assist devices (RESTAGE-HF [Remission from Stage D Heart Failure]): medium-term and primary end point results. Circulation. 2020;142:2016–2028. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.046415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bovendeerd PH. Modeling of cardiac growth and remodeling of myofiber orientation. J Biomech. 2012;45:872–881. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2011.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bovendeerd PH, Arts T, Huyghe JM, van Campen DH, Reneman RS. Dependence of local left ventricular wall mechanics on myocardial fiber orientation: a model study. J Biomech. 1992;25:1129–1140. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(92)90069-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bovendeerd PH, Borsje P, Arts T, van De Vosse FN. Dependence of intramyocardial pressure and coronary flow on ventricular loading and contractility: a model study. Ann Biomed Eng. 2006;34:1833–1845. doi: 10.1007/s10439-006-9189-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bovendeerd PH, Huyghe JM, Arts T, van Campen DH, Reneman RS. Influence of endocardial-epicardial crossover of muscle fibers on left ventricular wall mechanics. J Biomech. 1994;27:941–951. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(94)90266-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buoso S, Joyce T, Kozerke S. Personalising left-ventricular biophysical models of the heart using parametric physics-informed neural networks. Med Image Anal. 2021;71:102066. doi: 10.1016/j.media.2021.102066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell KS. Dynamic coupling of regulated binding sites and cycling myosin heads in striated muscle. J Gen Physiol. 2014;143:387–399. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201311078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell KS, Chrisman BS, Campbell SG. Multiscale modeling of cardiovascular function predicts that the end-systolic pressure volume relationship can be targeted via multiple therapeutic strategies. Front Physiol. 2020;11:1043. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2020.01043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell KS, Janssen PML, Campbell SG. Force-dependent recruitment from the myosin off state contributes to length-dependent activation. Biophys J. 2018;115:543–553. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2018.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carabello BA, Paulus WJ. Aortic stenosis. Lancet. 2009;373:956–966. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60211-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carabello BA, Zile MR, Tanaka R, Cooper GT. Left ventricular hypertrophy due to volume overload versus pressure overload. Am J Physiol. 1992;263:H1137–H1144. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1992.263.4.H1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cazorla O, et al. Differential expression of cardiac titin isoforms and modulation of cellular stiffness. Circ Res. 2000;86:59–67. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung E, Leinwand LA. Pregnancy as a cardiac stress model. Cardiovasc Res. 2014;101:561–570. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvu013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costabal FSY, Perdikaris P, Hurtado DE, Kuhl E (2020) Physics-informed neural networks for cardiac activation mapping. Front Physiol:8. 10.3389/fphy.2020.00042

- Cyron CJ, Aydin RC, Humphrey JD. A homogenized constrained mixture (and mechanical analog) model for growth and remodeling of soft tissue. Biomech Model Mechanobiol. 2016;15:1389–1403. doi: 10.1007/s10237-016-0770-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dabiri Y, Van der Velden A, Sack KL, Choy JS, Guccione JM, Kassab GS. Application of feed forward and recurrent neural networks in simulation of left ventricular mechanics. Sci Rep. 2020;10:22298. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-79191-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Bianco F, Colli Franzone P, Scacchi S, Fassina L. Electromechanical effects of concentric hypertrophy on the left ventricle: a simulation study. Comput Biol Med. 2018;99:236–256. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2018.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drazner MH. The progression of hypertensive heart disease. Circulation. 2011;123:327–334. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.845792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehler E, Gautel M. The sarcomere and sarcomerogenesis. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2008;642:1–14. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-84847-1_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emery JL, Omens JH. Mechanical regulation of myocardial growth during volume-overload hypertrophy in the rat. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:H1198–H1204. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.273.3.H1198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ennis DB, et al. Myofiber angle distributions in the ovine left ventricle do not conform to computationally optimized predictions. J Biomech. 2008;41:3219–3224. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2008.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enriquez-Sarano M, Akins CW, Vahanian A. Mitral regurgitation. Lancet. 2009;373:1382–1394. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60692-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estrada AC, Yoshida K, Saucerman JJ, Holmes JW. A multiscale model of cardiac concentric hypertrophy incorporating both mechanical and hormonal drivers of growth. Biomech Model Mechanobiol. 2021;20:293–307. doi: 10.1007/s10237-020-01385-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everett RJ, Clavel MA, Pibarot P, Dweck MR. Timing of intervention in aortic stenosis: a review of current and future strategies. Heart. 2018;104:2067–2076. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2017-312304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagard R. Athlete's heart. Heart. 2003;89:1455–1461. doi: 10.1136/heart.89.12.1455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finocchiaro G et al. (2021) Arrhythmogenic potential of myocardial disarray in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: genetic basis, functional consequences and relation to sudden cardiac death Europace doi:10.1093/europace/euaa348 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Frank DU, Sutcliffe MD, Saucerman JJ. Network-based predictions of in vivo cardiac hypertrophy. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2018;121:180–189. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2018.07.243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey N, Luedde M, Katus HA. Mechanisms of disease: hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2011;9:91–100. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2011.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey N, Olson EN. Cardiac hypertrophy: the good, the bad, and the ugly. Annu Rev Physiol. 2003;65:45–79. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.65.092101.142243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geerts L, Bovendeerd P, Nicolay K, Arts T. Characterization of the normal cardiac myofiber field in goat measured with MR-diffusion tensor imaging. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;283:H139–H145. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00968.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genet M, Lee LC, Baillargeon B, Guccione JM, Kuhl E. Modeling pathologies of diastolic and systolic heart failure. Ann Biomed Eng. 2016;44:112–127. doi: 10.1007/s10439-015-1351-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genet M, et al. Heterogeneous growth-induced prestrain in the heart. J Biomech. 2015;48:2080–2089. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2015.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Göktepe S, Abilez OJ, Parker KK, Kuhl E. A multiscale model for eccentric and concentric cardiac growth through sarcomerogenesis. J Theor Biol. 2010;265:433–442. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2010.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotzmann M, et al. Hemodynamics of paradoxical severe aortic stenosis: insight from a pressure-volume loop analysis. Clin Res Cardiol. 2019;108:931–939. doi: 10.1007/s00392-019-01423-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman W, Jones D, McLaurin LP. Wall stress and patterns of hypertrophy in the human left ventricle. J Clin Invest. 1975;56:56–64. doi: 10.1172/JCI108079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guccione JM, McCulloch AD. Mechanics of active contraction in cardiac muscle: Part I--Constitutive relations for fiber stress that describe deactivation. J Biomech Eng. 1993;115:72–81. doi: 10.1115/1.2895473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guccione JM, Waldman LK, McCulloch AD. Mechanics of active contraction in cardiac muscle: Part II--Cylindrical models of the systolic left ventricle. J Biomech Eng. 1993;115:82–90. doi: 10.1115/1.2895474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guterl KA, Haggart CR, Janssen PM, Holmes JW. Isometric contraction induces rapid myocyte remodeling in cultured rat right ventricular papillary muscles. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;293:H3707–H3712. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00296.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill JA, Olson EN. Cardiac plasticity. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1370–1380. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra072139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey JDaR, K. R. (2002) A constrained mixture model for growth and remodeling of soft tissues Mathematical Models and Methods in Applied Sciences 12:407-430

- Huxley AF. Muscular contraction. J Physiol. 1974;243:1–43. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1974.sp010740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- J. D. Humphrey (2021) Constrained mixture models of soft tissue growth and remodeling – twenty years after Journal of Elasticity doi:10.1007/s10659-020-09809-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Janicki JS, Brower GL. The role of myocardial fibrillar collagen in ventricular remodeling and function. J Card Fail. 2002;8:S319–S325. doi: 10.1054/jcaf.2002.129260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerckhoffs RC, Omens J, McCulloch AD. A single strain-based growth law predicts concentric and eccentric cardiac growth during pressure and volume overload. Mech Res Commun. 2012;42:40–50. doi: 10.1016/j.mechrescom.2011.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klepach D, et al. Growth and remodeling of the left ventricle: a case study of myocardial infarction and surgical ventricular restoration. Mech Res Commun. 2012;42:134–141. doi: 10.1016/j.mechrescom.2012.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroon W, Delhaas T, Arts T, Bovendeerd P. Computational modeling of volumetric soft tissue growth: application to the cardiac left ventricle. Biomech Model Mechanobiol. 2009;8:301–309. doi: 10.1007/s10237-008-0136-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroon W, Delhaas T, Bovendeerd P, Arts T (2009b) Computational analysis of the myocardial structure: adaptation of cardiac myofiber orientations through deformation. Med Image Anal 13:346–353. 10.1016/j.media.2008.06.015 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kroon WD, T.; Bovendeerd, P., Arts, T.; (2009c) Adaptive reorientation of cardiac myofibers: comparison of left ventricular shear in model and experiment In: Ayache N, Delingette H, Sermesant M (eds) Functional imaging and modeling of the heart FIMH 2009 Lecture Notes in Computer Science 5528 doi:10.1007/978-3-642-01932-6_7

- Kuhl E, Maas R, Himpel G, Menzel A. Computational modeling of arterial wall growth. Attempts towards patient-specific simulations based on computer tomography. Biomech Model Mechanobiol. 2007;6:321–331. doi: 10.1007/s10237-006-0062-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lalande S, Johnson BD. Diastolic dysfunction: a link between hypertension and heart failure. Drugs Today (Barc) 2008;44:503–513. doi: 10.1358/dot.2008.44.7.1221662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latorre M, Humphrey JD (2020) Fast, rate-independent, finite element implementation of a 3d constrained mixture model of soft tissue growth and remodeling. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng 368. 10.1016/j.cma.2020.113156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lee LC, Genet M, Acevedo-Bolton G, Ordovas K, Guccione JM, Kuhl E. A computational model that predicts reverse growth in response to mechanical unloading. Biomech Model Mechanobiol. 2015;14:217–229. doi: 10.1007/s10237-014-0598-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee LC, Kassab GS, Guccione JM. Mathematical modeling of cardiac growth and remodeling Wiley Interdiscip. Rev Syst Biol Med. 2016;8:211–226. doi: 10.1002/wsbm.1330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee LC, Sundnes J, Genet M, Wenk JF, Wall ST. An integrated electromechanical-growth heart model for simulating cardiac therapies. Biomech Model Mechanobiol. 2016;15:791–803. doi: 10.1007/s10237-015-0723-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee LC, et al. Algisyl-LVR with coronary artery bypass grafting reduces left ventricular wall stress and improves function in the failing human heart. Int J Cardiol. 2013;168:2022–2028. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee T, Bilionis I, Tepole AB (2020) Propagation of uncertainty in the mechanical and biological response of growing tissues using multi-fidelity Gaussian process regression. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng:359. 10.1016/j.cma.2019.112724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Li J, et al. New frontiers in heart hypertrophy during pregnancy. Am J Cardiovasc Dis. 2012;2:192–207. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin IE, Taber LA. A model for stress-induced growth in the developing heart. J Biomech Eng. 1995;117:343–349. doi: 10.1115/1.2794190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindman BR, Clavel MA, Mathieu P, Iung B, Lancellotti P, Otto CM, Pibarot P. Calcific aortic stenosis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016;2:16006. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2016.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd JW, Nishimura RA, Borlaug BA, Eleid MF. Hemodynamic response to nitroprusside in patients with low-gradient severe aortic stenosis and preserved ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70:1339–1348. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.07.736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann CK, Lee LC, Campbell KS, Wenk JF. Force-dependent recruitment from myosin OFF-state increases end-systolic pressure-volume relationship in left ventricle. Biomech Model Mechanobiol. 2020;19:2683–2692. doi: 10.1007/s10237-020-01331-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maron BJ. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a systematic review. JAMA. 2002;287:1308–1320. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.10.1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maron BJ. Clinical course and management of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1977. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1812159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maron BJ, Maron MS. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Lancet. 2013;381:242–255. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60397-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]