Abstract

Abstract

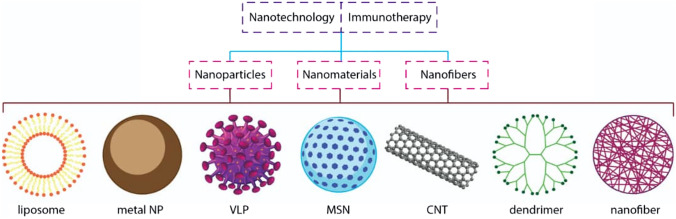

Currently, nanoscale materials and scaffolds carrying antitumor agents to the tumor target site are practical approaches for cancer treatment. Immunotherapy is a modern approach to cancer treatment in which the body’s immune system adjusts to deal with cancer cells. Immuno-engineering is a new branch of regenerative medicine-based therapies that uses engineering principles by using biological tools to stimulate the immune system. Therefore, this branch’s final aim is to regulate distribution, release, and simultaneous placement of several immune factors at the tumor site, so then upgrade the current treatment methods and subsequently improve the immune system’s handling. In this paper, recent research and prospects of nanotechnology-based cancer immunotherapy have been presented and discussed. Furthermore, different encouraging nanotechnology-based plans for targeting various innate and adaptive immune systems will also be discussed. Due to novel views in nanotechnology strategies, this field can address some biological obstacles, although studies are ongoing.

Graphic abstract

Keywords: Cancer, Immunotherapy, Regenerative medicine, Nanotechnology, Neoplasms

Introduction

The host’s immune system manages the health of the body and elides pathogens that threaten the general physiological condition of the host. The innate immune system has a primary role in identifying its cell-surface pattern receptors, recognizing pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMP) in the microorganisms and damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMP) that are released from damaged tissues to create a compatible response to microbial infections and tissue inflammations [1]. Immunotherapy, which can stimulate white blood cells to identify tumor tissues, is increasingly a promising strategy for managing cancer [2]. Immunomodulation for tumor management can be commenced as an exact tumor suppression procedure that is more effective than delivering cytotoxic agents to eradicate affected cells [3]. Its application for cancer patients is associated with long-term inhibition or even removal of tumor tissues, mainly due to the body’s systematic response to such intervention and long-term memory response. Generally, immunotherapy is a therapeutic approach for cancer patients that enhances natural defenses to cope with cancer. The success of cancer immunotherapy depends on the existence of three critical agents.

Cancer antigens should be effectively performed for white blood cells, particularly antigen-presenting cells (APCs).

Delivering an adjuvant to immune cells, along with antigens, shouting the immune system response.

Suppression of the immune system should be regulated to achieve an anticancer immune-therapeutics response.

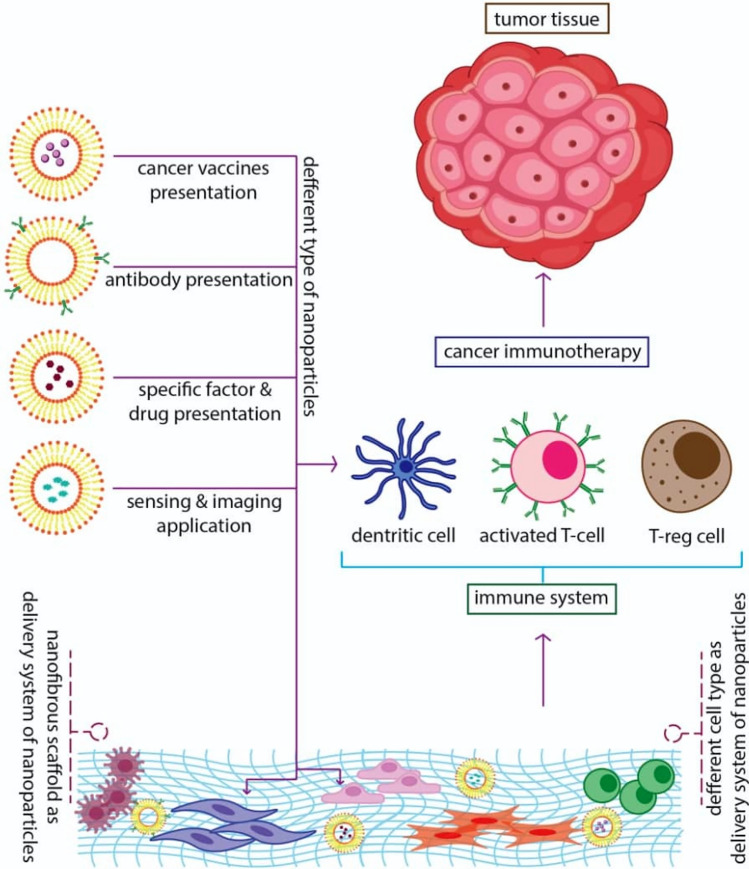

In this regard, nanotechnology-based products can effectively cause immune system response for each feature [4]. Recently, several cancer immunotherapies have been developed, like vaccines, chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy [5], immune checkpoint blockade [6], and administration of cytokines [7]. For instance, cancer vaccines are generated to strengthen cancer antigen presentation in Dendritic cells (DCs) to enhance the robustness of effector T-cell proliferation. Tumor microenvironment (TME) modulation intends to cause the “brake” for cytotoxic T cells (CTLs) in the suppression of the immune system TME, facilitating the ability to kill their targeted cancer cells [8]. Several immunological methods have been entirely described that immunotherapies and vaccines stimulate the immune systems (both adaptive and innate) at the single-cell level. As we know, one of the most critical applications of nanotechnology-based scaffolds and nanoparticles is targeted drug delivery, which the use of this three-dimensional system for cancer treatment could create a significant revolution in cancer treatment methods (Fig. 1). In recent years, findings demonstrate that the interaction between cancer cells and immune cells is critical in cancer research to understand the immune system behaviors which can suppress cancerous growth and apply protective functions. However, recently, it is well-established known that these cancer cells are associated with immune cells may appear acting jointly with restrict and enhances tumor development. Within the immune system, effector immune cells, including CD8+ cytotoxic T cells, effector CD4+ T cells, natural killer (NK) cells, dendritic cells, M1-polarized macrophages, and N1-polarized neutrophils are in the center of the antitumor process. In contrast, myeloid-derived suppressive cells (MDSC) or tumor-associated macrophages (TAM), their derived cytokines IL-6, tumor necrosis factor (TNF), IL-1β, IL-23, and regulatory T cells (Tregs) are frequently perceived as dominant tumor-promoting immune cells [9, 10]. Furthermore, Th17 cells, CD4+ CD25+ Foxp3+ Tregs, and cytokines related to immunoregulatory like TGF-β play dual roles concerning promoting or preventing cancer development, depending on the TME and the episodes preceding the primary promotion of tumor genesis [9, 10].

Fig. 1.

Summary illustration of nanoparticles/nanofibers application for enhancing of the immune system potency against cancer

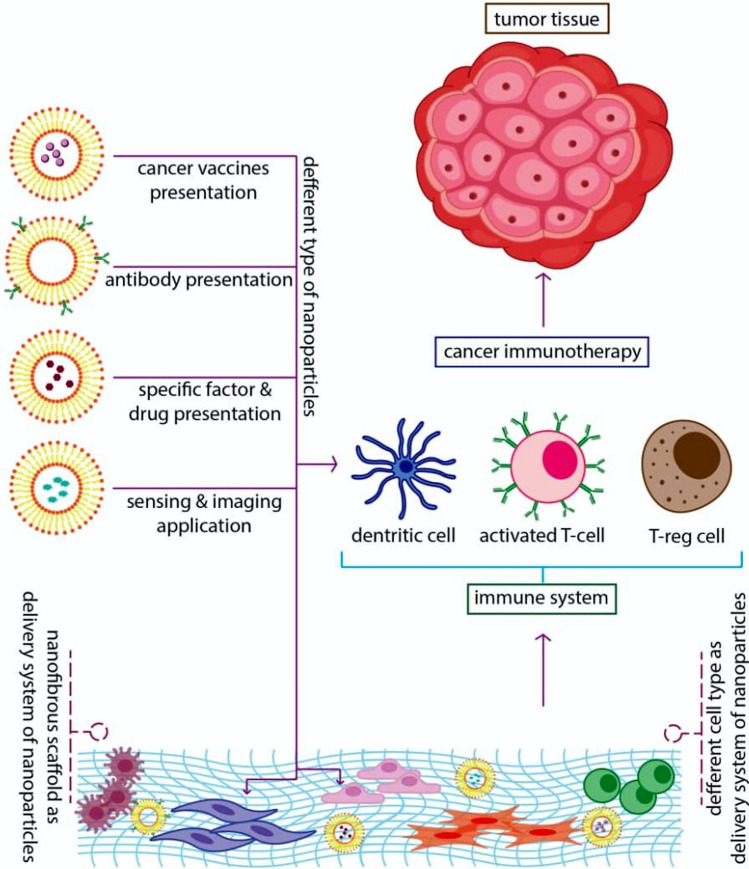

The cancer research field is a multidisciplinary area that contributes different scientists from diverse disciplines to the unit target. On the other hand, nanotechnology is a developing and promising field that has recently become tremendous exciting in the biomedical especially cancer therapy research. For instance, Mingxu You et al. recently developed a DNA-based gadget termed the “Nano-Claw” [11]. They combined the unique structure-switching properties of DNA aptamers with toehold-mediated strand condensation reactions to create a claw capable of performing an independent logic-based analysis of multiple cancer cell surface markers and producing a diagnostic signal and targeted photodynamic signal therapy in responding [11]. However, nanotechnology-based products (see Fig. 2) have various applications in different medical fields using various nanostructures [12]. Over the last decade, these products have been a noticeable impact in advanced medical technology, especially in multiple sectors of the cancer research fields containing the delivery mechanisms for cells, drugs, genes, and systems for protecting cells. However, structural and functional limitations in the cell range restrict the cancer therapy program’s development.

Fig. 2.

Different nanomaterials with unique structures that are applied in cancer immunotherapy

Generally, there are four comprehensive strategies for using nanomaterials and nanoparticles to regulate responses of the immune system:

The first approach contains ex vivo attaching and then internalizing immune cells, which means in vivo equipment of such cells for future injection. The nanoparticle load could deliver ingredients that stimulate the functions of immune cells or expose new functionalities to target cells.

A next strategy contains in vivo application of “natural targeting” of nanoparticles to phagocytic cells, administration of free particles scavenged by macrophages, monocytes, neutrophils, or DCs in the blood, liver, spleen, and bone marrow, as well as other cancer cells.

In the third method, “active” targeting is surveyed; thereby, particular antibodies or ligands on the exterior of nanoparticles are employed to achieve particular cell bindings in vivo [13].

In the fourth strategy, the nanofibrous scaffold can be applied as a delivery tool for certain biological factors. This strategy provides a combination biologic therapy plan contain concurrent delivery of genes, cells, and other drugs [12, 14].

Nanotechnology-based products can exclude some functional and structural barriers in cancer immunotherapy (Fig. 3). Nanotechnology has two leading roles in vaccine structure. First, they are used as a carrier for the transfer of vaccines, and, second, due to their innate adjuvanticity, they could improve the immune responses [15, 16]. Consequently, different nanostructures have been introduced as novel adjuvant manners for enhancing antigen delivery and presentation to APCs [13].

Fig. 3.

Cancer immunotherapy and its multidisciplinary requirements; nanotechnology can help cancer immunotherapy in different aspects

However, some nanomaterials, due to some specific physiochemical attributes, can inherently regulate the immune response; for instance, the nanoparticle shape influences antibody and cytokine production [17]. The benefits of using nanoparticles roots in the distinctive nanoscale characteristics of conveyors, morphology, non-rigid regulation of the conveyor magnititute, and surface attributes containing targeting moieties and charge. The enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) reaction, nanoparticles due to their weak lymphatic drainage and dripping vasculature, primarily gather within tumors [18]. Moreover, nanomaterials can be modified easily, and targeting ligands already loaded on the exterior can facilitate nanomaterials take up by particular cells. Although most common immunotoxicological investigations have solely investigated the suppression of the immune system, most nanoparticle research has investigated their inflammatory characteristics.

Nonetheless, the rest of the research reported that nanoparticles are applicable for delivering drugs developed for suppressing the immune system [19]. Usage of nanomaterials to imaging agents and delivering cytotoxic agents will advantage immunotherapy. Studies demonstrate that adjuvant and antigen to APCs’ concurrent delivery activates antigen-specific immune impacts. Moreover, cancer vaccines based on nanoparticles offer higher anticancer efficacy than naked curative agents shown in animal models [13, 20].

In the present study, the activation of the immune system in encountering cancerous conditions is investigated. After that, recent studies and prospects of nanotechnology-based cancer immunotherapy will be presented. Furthermore, examples of different encouraging nanotechnologies-based approaches for targeting various immune populations (either innate or adaptive) will also be discussed. We hope this paper could offer a new element of nanoparticle and nanofibrous scaffold applications in immune system function and attract readers and researchers of the cancer immunotherapy field investigating or will join this fast-developing field.

Activate the immune system

Despite many studies to understand the underlying causes of cancer, there is still no comprehensive answer to its etiology due to its complexity. Existing environmental factors in the micronucleus (micro-environment) cell, extracellular matrix, and even immune cells can influence the development and spontaneous proliferation of cancer tissues and metastatic cells and stop them. Therefore, cancerous cells and tumors should be examined in their natural niche to better study and treat cancer. The kind, density, and area of white blood cells that are called immune compositions around the tumor can predict disease progression even better than the past pathological methods; so that the immune cells around the tumor are more active than rest condition, the length of time the survival of the patient is also greater [1]. Clinical studies have determined that activating the innate antitumor immune response can treat relapsing-resistant cancers [2].

The Natural killer T cells (NKT) and γδ T cells have a role in immunities by interactivities with the adaptive immune cells. They are considered the connector of the adaptive and innate immune systems [1].

To suppress cancerous cells, the body employs the three strategies: (1) eliminating carcinogenic pathogens and protecting the body against the cytokines of these cells, (2) protecting the body against the pro-tumoral inflammatory environment, and (3) immunosurveillance in the activity of specific cells like T cells in the innate and acquired immune system that eliminates tumor cells [21].

The microenvironment of tumors usually includes an extracellular matrix and a broad spectrum of cells like fibroblasts, endothelial, immune cells (like NK, DC, polymorphonuclear leukocytes, and cytotoxic T lymphocytes [1]), cancerous tissues, and specific cytokines and receptors for these cells [22]. Accurately, type I macrophages, T helper (Th1), and NK cells are dramatically active at the cancer location to prevent its expansion [21]. Cancerous cells decrease the immune response by secreting some cytokines (called immunosuppressive challenges) [21]. If we want to explain more about the tumor microenvironment, enhanced Bcl2 expression increases fibroblasts and apoptosis resistance. It has also been shown that Bcl2 defends tumor cells against anticancer drugs [22]. Also, increased IL-6 expression in the aging increases TGF-β receptors’ expression, which causes tumorigenesis [22]. Many immunosuppressive factors are naturally a physiological regulatory mechanism applied by the body to prolong homeostasis to avert autoimmunity [23].

Interestingly, these are dual approaches for the system against cancer. The system has a paradoxical role, called the immunoediting hypothesis. However, in some conditions, T cells and antibodies against tumor-associated antigens (TAA) may induce more excellent tumor formation [1]. Thus, the immune system may enhance angiogenesis by producing and secreting some growth factors and cytokines and as well as by increasing chronic inflammation in the tumor environment, resulting in the activation of premalignant lesions [21]. In fact, chronic infections debilitate the immune system against tumor cells (an augmented cycle). For example, cancer risk is enhanced in AIDS infection (an immunosuppressive virus) that involves CD4+ T cells. Thus, by secreting a large amount of interferon, the number of CD8 cytotoxic cells increases, which causes cancer tissue death cells; however, the lack of CD4+ T cells prevents this reaction [21].

A variety of factors cause the host’s immune system to be unable to identify cancer cells or adapt to a tumor, thereby causing the tumor to grow in the body. The presence of some parasites is one of these factors. Helminths species (a parasitic worm) can act as an immune regulator by affecting the immune system. These parasites prevent TGF-β secretion by inhibiting the growth of T cells and encouraging the Treg cells growth. As a result, it obstacles the immune effect on cancer cells [21] and promotes angiogenesis [23].

The Tregs are divided into two groups: (1) natural Tregs (nTreg) that are Thymus-developed cells of FoxP3 lineage, and (2) inducible Tregs (iTreg) derived from naive CD4+ T-cell precursors under tolerogenic conditions and are upregulate FoxP3 expression [23]. Tregs regulate the immune system with 4 mechanisms: (i) Immunosuppressive molecules release, which is either soluble or membrane, (ii) straight cytolytic function, (iii) metabolic disorder, and (iv) DC suppression [23].

Another compelling factor is the age of the host. In aging, immune system activity attenuates through a decreased capacity of immunosurveillance [21, 22]. Thymopoiesis decline with an increase in age; it is thought to cause immune system damage (immunosenescence). Of course, the phenomenon of immunosenescence (refers to the gradual deterioration of the immune system brought on by biological age advancement) does not mean inactivation of all immune functions; It means that during one’s life, several functions decrease, others increment, while others remain unchanged [22]. Another critical age-related factor is thymus activity. The thymus is very useful in producing T cells and maintaining immunity. T cells play an essential role as an inducer of tumor immunity [22]. This lymph node is active between the ages of 10 and 19 and gradually decreases with increasing age. Agents may augment the risk of cancer in aging over the 65, such as (1) significantly reduced naive T cells, (2) decreased population of lymphocyte clones, (3) an increased frequency of regulatory T cells that reduces the T cells response, (4) a low grade, proinflammatory status, and (5) increasing the number of suppressor cells that are based on myeloid, which impedes the proper functioning of T cells and produces the reactive oxygen species [24]. Increasing age causes changes in the number, phenotype, and function of leukocytes, like metabolism of glucose, PAMP signaling, phagocytic volume, and cytokine release [24]. In aging, the combination of proinflammatory cytokines [e.g. IL-1 β, IFNγ, and granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF)] increases MDSCs release in the host bone marrow. It accumulates in the lymph nodes, increasing the production of MDSCs in the hose bone marrow and cumulating in the lymph. This increase in production suppresses T-cell proliferation and activity and enhances ROS production [24]. Besides, MDSCs prevent the positive effect of dendritic cell-based immunotherapies [24]. At the initial stages of tumor formation, some immune cells, like NK and CD8 + T cells, detect them and remove them [25]. At this stage, the tumor cells can run away from white blood cells by two strategies: The first is the runaway from the immune system’s identification. In this case, cancer cells prevent the identification of cytotoxic T cells by not expressing or reducing the expression of tumor antigens at their surface. Mutation or deletion of individual gene fragments in tumor tissues may down-regulate the presentation mechanism of the antigen, leading to resistance to T-cell effector molecules and the production of specific cytokines like IFN-γ [25]. The down-regulated NK cells cannot identify cancer cells, especially in lung and breast cancer. In non-small cell lung cancers, only 40% of HLAs remain on the cancer cell’s surface, impeding these cells’ identification. The same is true for metastatic colorectal cancer, which makes resistance to T-cell transfer therapy in these patients [25]. The second is cancer cells with the secretion of immunosuppressive molecules like IL-10 and VEGF, and deterrent checkpoint molecules expressions, like PD-L1 and V domain immunoglobulin suppressor of T-cell activation, induces activity in TAMs, MDSCs, and Tregs. This activation also can induce with secreting tumor cytokines like CC-chemokine ligand 2 (CCL2), colony-stimulating factor 1 (CSF1), CCL5, CCL22, C-X-C motif chemokine 5 (CXCL5), CXCL8, and CXCL12 [26].

The tumor-associated macrophages (TAM) and tumor-associated Tregs in cancer develop an immune tolerance in the host body that destroys the effects of innate and adaptive effector immune cells [6]. Two TAMs and Tregs cells producing immunosuppressive molecules like IL-10, TGF-β cause immune tolerance in TME (tumor microenvironment). Also, these cells can intervene in the IL-12 secretion of DCs, blocking the Th-1 response [25]. The activities of effector T cells are restrained by Treg-derived cytokines like IL-10, TGF-b, and IL-35 [23]. The impact of Treg on the DCs includes the following: (i) to express cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA-4) on Treg membrane and express CD80 and/or CD86 on DC membrane causes cell–cell signaling, to increase the production of 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) in DCs, (ii) to decrees DC capacity to activate effector T cells by inhibiting co-stimulatory molecules, (iii) to suppress of DC maturation via IL-10/TGF-b signaling, (iv) Treg–DC interactions mediated by lymphocyte-activation gene 3(LAG3) [23]. In one study shown in EMT6 breast cancer, inhibition of TGF-β secretion increases response to treatment with anti-PD-L1, leading to improved patient survival [25].

In breast cancer, hypoxia and stimulating angiogenesis can cause Treg to migrate to the tumor site. Whereas hypoxia augments CCL28 expression at the cancer cell surface, this ligand interacts with the CCR10 receptor on the Treg surface (with the cd4+/CD25+/Foxp3+marker). Also, in ovarian cancer, CCL28 expression is related to hypoxia-inducible factor 1a (HIF-1) expression, indicating a poor prognosis of the disease [23].

DCs and macrophages are APCs. In general, DCs are considered APCs with the highest effectiveness, required in activating CTLs through MHC class I molecules and costimulator (like CD80 and CD86) and in initiating an adaptive immune response. Aging may decrease the antigen-presenting capacity of APCs and the existence of co-stimulatory pathways on their exterior. Much experimental evidence suggests that one of the causes of decreased APC activity in aging is decreased proteasome expression. APCs with TLRs can detect self and non-self-pathogen-associated structures. The expression level of these receptors decreases with aging. Moreover, cytokine production essential for both distinction and functions of APCs, like IL-4 and IL-12, reduces in elders [25].

To sum up this section, cancer tissues can escape from the immune system in various ways. As a result, most safe immune processes, especially those embedded in complex and solid tumors, are only effective for a small number of patients. Therefore, the provision of immune cells to address the obstacles created by the suppression of the tumor’s immune cells is a pivotal immunotherapy approach. Empirical evidence has shown that immune-stimulating molecules that are delivered using nanoparticles and scaffolds with greater precision and intensity can stimulate the immune system to deliver these molecules through the solution; thus, its antitumor effects are also higher. Hence biologists and tissue engineers are working to determine which cells, pathways, and tools can enhance the effectiveness of this stimulation and activation of the immune system.

Nanoparticle and nanofibrous scaffold preparation

According to the recent advances in nanotechnology and its application in medicine and daily life, the last century can be named nanotechnology. There are several nanoparticles and nanofibrous scaffold fabrication methods such as emulsification and dispersion polymerization, solvent evaporation and solvent extraction processes, phase separation, interfacial polymer deposition following solvent displacement, spray drying, and also several industrial methods. Moreover, there are several nanofibrous mats fabrication methods such as Electrospinning, Self-assembly, Cell–matrix adhesion, Drawing and Patterning, which can produce by natural or synthetic polymers and the composite of them in the presence and absence of the immune-cells encapsulated nanoparticles. Due to specific cellular uptake and tissue bio-distribution, nanoparticles could have wide application in tissue and cell-based therapy related to cancer immune therapy [12, 27]. Several new studies have introduced nanoparticle applications as organ/cell-specific carriers and detection, imaging, tissue engineering, bio-fabrication, and therapeutic purposes [12, 28, 29]. In the following, we focus on studies and ideas that present nanotechnology-based products for developing cancer immunotherapy.

Nanotechnology and cancer immunotherapy

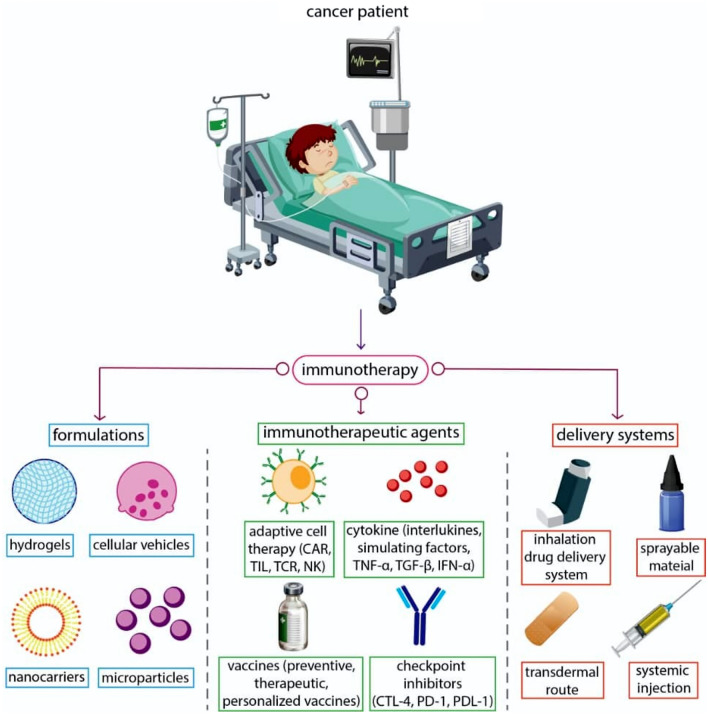

Nanoparticles and cancer immune-therapy

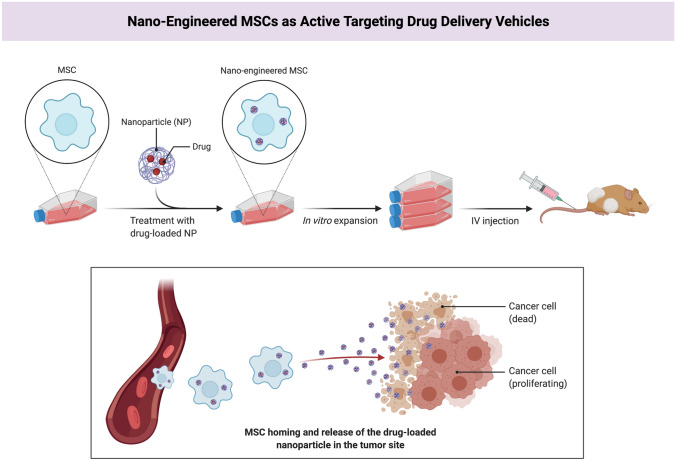

Nanoparticles are synthetic particles made up of polymers, lipids, or metals and are nanoscale in size. These nanoparticles can be used in biodegradable carriers and therapeutic agents that cause high-dose drug release in the target area (Fig. 1). The surface-to-volume ratio of these nanoparticles has enabled these materials to be coated with various ligands, including antibodies and aptamers, thereby facilitating the interaction with the desired molecules, including receptors located on the exterior of target cells. Moreover, nanoparticles can be applied in effective engineering cells as active targeting drug delivery vehicles (Fig. 4). Cell-based therapies, particularly stem cells, have led to optimism in treating different diseases, especially cancer [30–32]. This advantage of nanoparticles also can be valuable in engineering different cell-based therapy products for developing cancer immunotherapy.

Fig. 4.

Combining nanotechnology and cell therapy to generate “nano-engineered” mesenchymal stem cells. This biological product would be able to actively target the tumor site and protect the drug-loaded nanoparticle from vascular filtration and macrophage clearance; The figure is made with biorender (https://biorender.com/)

Furthermore, nanoparticles can enhance the pharmacokinetics of maximum drug loading [3], which effectively increases their ability to target cancer cells that escape the immune system. Labeling nanoparticles for specific receptors on cancer cells reinforces cellular absorption by aggregating the desired molecule and releasing it in place. In contrast, leukocytes can actively move through these chemokine gradients onto these nanoparticles towards tumor cells and consequently stimulate these cells as ultimate targets. Therapeutic delivery systems are one of the main challenges in therapeutic approaches [12, 33]. The delivery of immune-stimulatory drugs to antitumor immune cells brings about cancerous cells rather than delivering cytotoxic drugs, which results in almost no risk of recurrence.

Consequently, the successful delivery of immune-stimulating molecules to a small number of immune cells can significantly enhance antitumor and therapeutic efficacy while administering a large number of cytotoxic drugs and delivering them to many tumor cells may not change even in the progression of cancer. It is due to the cancerous cells being heterozygous and maybe a drug for several types of deadly clones, but not for many fatal ones, and/or some cloning cells survive due to lack of medication. In this regard, even if there is a resistant clone or insufficient penetration of the drug, few cancer cells survive, the risk of relapse may be 100% [34, 35]. Conversely, immune cells with memory cells can provide a more consistent and lasting response to all other types of therapies. Targeting nanoparticles for dendritic cells are more likely than targeting these nanoparticles for cancer cells [15, 36]. This can be attributed to the activities of our immune system. The secondary lymphoid organs, especially the spleen that is full of dendritic cells, accumulate in these structures due to the stomatal structure. Moreover, secondary lymphoid organs do not have physical inhibition due to a dense extracellular matrix for immune cell entry in solid tumor tissues [15, 36].

Dendritic cells are the primary triggers for acquired immune responses and are, therefore, the most important targets for anticancer nano-drugs. Simultaneous systemic administration of antigen and adjuvants can result in antigens delivery to some DCs and delivery of adjuvant to other dendritic cells. Delivery of antigen to DCs in the absence of adjuvant results in immunologic tolerance and prevents the strengthening of antitumor responses. Simultaneous placement of antigens and adjuvants in a particle can simultaneously deliver these two components of the same dendritic cell, resulting in enhanced stimulation of specific antigens of CD8+ T cells, a primary antitumor immunity mediator. Research has shown that the efficient release of the antigen from a particle (as an antigen source) to dendritic immune cells by enhancing the antigen delivery to immune cells can lead to further increase of the killer T cells and improve cancer, including Papilloma [37, 38].

On the other hand, a series of dendritic cells are essential in the induction, stimulation and immune activities regulation. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells can be converted from inactive to the active and immune-stimulating state by attracting Toll-like receptor agonists (TLRs). Hence, using several dendritic cell subgroups, the effectiveness of antitumor drugs can be maximized by simultaneously stimulating hemorrhagic and cellular immune responses [39]. Zhang et al. have recently reported that their nanoparticle formulations can effectively improve the severe toxicities of immune-stimulatory agents for antitumor immunity. They designed nanoparticle (PEGylated) liposomes bearing surface-conjugated interleukin 2 (IL-2) and anti-CD137, and observed that anchoring IL-2 and anti-CD137 on the surface of nanoparticles allows such immune agonists to aggregate in cancer tissues by systemic IV injection quickly. This study introduces a general approach for using nanoparticles to apply the potent inducing function of immune agonists in cancer immunotherapy [40]. Therefore, nanoparticles provide an interactional condition for the cooperation of two or multiple chemotherapeutic factors. In another study, polyethylene glycol-modified poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid) nanoparticles were used to increase the synergic effect of IRAK1/4 inhibitor and ABT-737 in T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL) mice. They were reported to enhance the survival duration of T-ALL on the mouse model [40].

Nanostructural scaffolds and cancer immune-therapy

In addition to nanoparticles, scaffolds with a nano structure can also be used to produce anticancer vaccines. The self-assembling (SA) is a considerable change by which targets of nanophase/molecules evolve to instant categories [41]. Different SA systems are introduced, ranging from copolymers in blocks to 3D cell culture scaffolds. These structures can manage various materials, such as different polymers, and use them in cancer therapy and tissue engineering [41]. Nanostructural scaffolds are applied to address some of the clinical obstacles to immunotherapies that use T cells and result in a new perspective on this evolving area at the interface of cancer immunotherapy and nanotechnology-based products. Moreover, scaffolds could be usefully similar to conventional dendritic cell-based vaccines, which require the isolation, ex vivo manipulation and re-entry of dendritic cells into the patient’s body for the use of them.

Polymeric and hydrogel scaffolds that containing inflammatory cytokines, tumor antigens, and topical immune-compromised signals in one place can be transplanted or injected as an appropriate topical medication. A study has shown that hydrogel scaffolds containing manipulated mesenchymal stem cells secreting antitumor proteins showed a robust antitumor effect on the tumor site [39]. Another study was shown that insertion of lysed tumor particles, CpG oligonucleotide, GM-CSF chemokine, TLR9 agonist in a porous PLGA scaffold and its subcutaneous transplantation could activate and homing of the dendritic cells. Consequently, it triggered the destruction of tumors in the place or the farthest position [42]. This ability, because of delivering antigen and adjuvant messenger to an immune cell simultaneously [42]. As previously mentioned, this simultaneous delivery of the vaccine components as a solution into a single cell with very low probability occurs.

Solid tumors generally create a dense environment around them and suppress the immune system at the tumor site and prevent activating ACT, which escapes the immune system via this way. The transfer of lymphocytes to biodegradable polymeric scaffolds can promote the growth and release of tumor-degrading T-cells in the tumor and most efficiently reduce the risk of cancer recurring rather than when T cells are used systemically or even topically applied [43, 44].

Hence nanoparticles and nanostructural scaffolds as valuable tools can be applied in cancer Immune-therapy. In the following, we review the nanotechnology-based product’s interaction with immune system agents in the cancerous condition during its immunotherapy strategies.

Nanomaterials for modulating innate immune system

Nanoparticles can increase the immunomodulator’s delivery to immune cells and recuperate the effect of immunotherapy. Most studies indicate that it is feasible to apply immunotherapy by adjusting innate immune cells. Nanoparticles can modulate various innate immune cells, including monocytes, NK cells, TAMs, neutrophils, DCs, and MDSCs [45]. For instance, TAMs can act as antigen-presenting cells and produce different solubles to interact with other immune cells. In addition, they play a crucial role in cancer immunotherapy [45]. For instance, Song et al. [46] used the extra benefits of the high accumulation of TAMs in hypoxic regions of cancer tissues and elevated reactivity of manganese dioxide nanoparticles (MnO2 NPs). They intended to produce hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) for the concurrent modulation of pH and production of O2 for effective reduction of tumor hypoxia by targeting the delivery of MnO2 NPs to the hypoxic area. Hence, they reported that combined management of cancer tissues with Man-HA-MnO2 NPs and Doxorubicin considerably increases apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) values of breast cancer cells.

Moreover, cancer cell oxygenation was increased, hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) down-regulated, and cancer cell proliferation and growth were inhibited compared to the sole chemotherapy [46]. Silva et al. [47], in a study on the utilization of dextran crosslinked-iron oxide nanoparticles in Lewis lung carcinoma tumor-bearing mice, reported changed phenotypes of TAM. In the nanoparticle-treated group, the variation of TAM to proinflammatory type was significant. Thus, this research requires consideration in that inorganic iron oxide nanoparticles operated as both an image contrast agent and a TAM-reprogramming agent [47].

As well as, Liu et al. showed that self-crosslinked redox-responsive nanoparticles based on galactose-functionalized n-butylamine-poly (l-lysine) -b-poly (l-cysteine) polypeptides (GLC) coated with DCA-grafted sheddable poly(ethylene glycol) PEG-PLL (sPEG) copolymers was successfully used to deliver miR155 to TAMs [48]. Recently it was reported that miR155 engagaed in reducing cytokine secretion and to polarize M2-type macrophages toward M1 type. Management of miR155-loaded sPEG/GLC (sPEG/GLC/155) nano-complexes enhanced miR155 expression in TAMs about 100–400 folds both in vivo and in vitro. The sPEG/GLC/155 also effectively repolarized immunosuppressive TAMs to antitumor M1 macrophages through increasing M1 macrophage markers (IL-12, iNOS, MHC II) and suppressing M2 macrophage markers (Msr2 and Arg1) in TAMs. It was found that treatment with sPEG/GLC/155 increased activated NK cells and T lymphocytes in tumors, which resulted in strong reversion of the tumor [48].

In comparison to TAMs, few research described modulating NK cells, which can produce proteins like proteases and perforin to marginal cancer tissues and enhance the permeability of the membrane of target cells [49]. In this regard, a series of nanomaterials are investigated for their properties to modulate or stimulate the NK cells [50]. Jang et al. studied nanoparticles with magnetic properties to regulate the transfer of NK cells to tumor tissues [50]. They separated and loaded NK cells with nanoparticles with magnetic properties using a magnetic field. They intravenously injected the human B cell lymphoma-bearing mice to expose them to an external magnetic field. Simultaneously by exposure magnetic field, a robust fluorescent color signal was identified in the cancer tissues. Their findings proved the migration of NK cells. This procedure lets us open another clinical therapeutic intervention with the lessened toxicity of the nanoparticles and increased infiltration into target cells [50].

MDSCs are another component of innate immunity that cannot be differentiated into mature forms, such as granulocytes and dendritic cells. It is found that the accommodation of MDSCs at tumor cells can include active NK cells and suppress T cell proliferation while enhancing the regulatory T cells distinction. The nanomaterial-mediated selective modulation of MDSCs at tumor tissues was associated with improved immune system suppression and showed a novel method for immunotherapy. Again, evidence regarding the nanomaterials to modulate MDSCs are not sufficient [51]. Since MDSCs cooperate in the negative regulation of antitumor immune reactions, decreasing MDSCs are a significant point to invert suppression of the immune system in the tumor microenvironment. Kong et al. in a study described a type of biodegradable hollow mesoporous silica nanoparticle (dHMSN) for co-arranged delivery of all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA), doxorubicin (DOX), and interleukin-2 (IL-2) to get increased antitumor efficiency in chemo-immunotherapy [52]. It was found that ATRA was helpful for differentiating the MDSCs from antitumor immune cells like mature dendritic cells (DCs), granulocytes, and macrophages and ameliorates the tumor-specific immune response. Hence, ATRA has a remarkable ability to regulate MDSC-induced immunosuppression [53]. According to interventions that are based on MDSC modulation, particular MDSC-targeting strategies require further evaluations. For instance, Liu et al. applied MDSC aptamer modified liposomes. Based on their findings, T1 aptamer was successfully binded to both MDSCs and tumor cells [54]. Besides, studies in the differentiation field [52] found that the lipid nanomaterials were employed for modulating MDSCs also could deliver cytotoxic anticancer pharmaceutical ingredients. The delivery of cytotoxic anticancer drug-loaded nanoparticles may increase the ability to distinct MDSCs and kill them. Future research on differentiation of MDSCs can use MDSC-specific nanomaterials, which may utilize favorable activities without destroying MDSCs [52, 54].

Neutrophils are essential for innate immune responses and advocacy against annoying infections. In response to chemotaxis, they can quickly transmigrate to infected or injured areas. In this regard, the accumulation of nanocarriers containing circulating neutrophils can provide a chance for therapeutic drug delivery management. Hence, the application of neutrophil-mediated drug delivery is investigated for cancer immunotherapy [55]. In another research by Chu et al., they used a strategy (i.e. monoclonal antibody TA99 specific for gp75 antigen of melanoma) for snatching neutrophils in vivo by nanoparticles to transfer therapeutics into the tumor [56]. In a mouse model of melanoma after injection, the photosensitizer (pyropheophorbide-a-loaded albumin nanoparticles) was anticipated to adjoin to neutrophils in the blood. To manage the neutrophils to cancer cells, the TA99, as co-injected, can modulate neutrophils to melanoma cancer cells by affecting antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity. Hence, this study determines a novel way to cure cancer through NP hitchhiking of the immune system to increase pharmaceutical ingredients transfer to cancer cells [56]. As well, Chu et al. conducted another study about the remodeling of tumor microenvironments that can enhance the delivery of nanoparticles [57]. Since the CD11b antibody was applied as a signal for activating neutrophils, they used this antibody with gold nanoparticles for increasing the neutrophils infiltration into cancer cells. A drug delivery platform consisted of NPs coated with anti-CD11b antibodies that target activated neutrophils. To increase neutrophils infiltration to cancer infected tissues, pyropheophorbide was administered to mice and clarified at 660 nm. The investigators assumed that, in tumor cells, photosensitization-induced might perform the gold nanoparticle-bound neutrophils to permeate the tissues. In conclusion, the group treated by CD11b-antibody-decorated gold nanoparticles demonstrated prolonged survival and reduced tumor growth those that received pegylated gold nanoparticles [57].

In all peripheral tissues, DCs are innate-similar cells, which are interfacing cells that associate the innate and adaptive immune reactions because they can activate native T-cells and B-cells (sometimes). These cells were gathering antigens from the circumambient fluid and remaining on stable vigilance for “danger signals”—molecular motifs implicating pathogen invasion or tissue damage. As a response caused by the innate immune system, DCs are capable of expressing various diagnostic receptors, like a stimulator of interferon genes (STING), TLRs, a retinoic acid-inducible gene I (RIG-I)-like receptors (RLRs), NOD-like receptors (NLRs), and C-type lectins. These molecules are responsible for activating DCs in cellular damage or pathogen exposure [45]. Several immunomodulators like STING agonists and TLR agonists are created to increase the DCs’ activities within cancer management. Regrettably, such immunomodulators have side effects. In addition, they are unstable. For solving this significant challenge, investigators are looking to use nanomaterials for delivering these immunomodulators. Hence, nanomaterials are intended to co-deliver immunomodulators for maximizing the effect of immunomodulators [58].

Nanoparticles increase DC activation effects on APCs by encapsulating or representing danger signals. Also, by “programming” the stimulation of DCs, nanoparticle formulations can directly affect humoral induction and cellular immunity to immunotherapies and vaccines [13]. For instance, Luo et al. reported in the study that activation of STING promotes the antigen-presenting capability and maturation of DCs [59]. In this study, a synthetic polymeric nanoparticle, PC7A NP, was produced with a peptide antigen as a nanovaccine that causes a potent cytotoxic T-cell activity, with a limited systemic cytokine expression. Upon administration, these nanoparticles were spread in the nodes of the lymph. According to the findings, PC7A presented a high binding property for STING. Thus, according to in vitro investigation based on DCs derived from bone marrow, these nanoparticles presented an adjuvant impact on DC evolution and increased maturation markers’ expression, comprising CD80 and CD86 [59]. Furthermore, in mouse models of colorectal cancer, melanoma, and lymphoma, vaccination with PC7A nanoparticles was more significant in tumor prevention than injecting vaccines that contained free antigen [13].

In another study, TLR7/8 agonist, imiquimod, treating basal skin carcinoma was approved by the FDA, and it is sold as a topical cream under the name Aldara® [60]. Imiquimod was co-encapsulated with the photothermal-responsive factor that means indocyanine green in the hydrophobic portion of biodegradable poly (lactic-co-glycolic) acid nanoparticles. Intravenous injection of indocyanine green/imiquimod-loaded polymeric nanoparticles demonstrated accumulation in tumor tissues. Afterward, according to the findings, irradiation could separate the primary cancer tissues of CT26 colon tumor-bearing mice. Indeed, this removal resulted in increased antigen presentation and DCs’ maturation [60]. Hence, available evidence has centralized on the innate immune cell biology mechanisms and their connection with cancer (Table 1).

Table 1.

Nanomaterials used as a goal of modulating innate immune cells for immunotherapy

| Nanomaterial | Targeted cell | Purpose | Tumor models | Cargo (Payload) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liposome | TAM | TAM reduction | KPC | Clodronate | [61] |

| Carboxylated polystyrene | TAM | TAM activation | E0771/E2 | [62] | |

| Glucomannan polysaccharide | TAM | TAM reduction | S180 | Alendronate | [63] |

| Hyaluronic acid-protamine @ cationic liposome | TAM | TAM activation | B16F10 | CD47 siRNA | [64] |

| Poly(b-amino ester)g-poly(ethylene glycol)-g-histamine | TAM | TAM reprogramming | B16F10 | IL-12 | [65] |

| Poly(L-lysine)b-poly(L-cysteine) @ Poly(ethylene glycol)-poly(Llysine)-g-(1,2dicarboxyliccyclohexene) | TAM | TAM reprogramming | B16F10 | miR155 | [48] |

| M2-like TAM dual-targeting nanoparticles (M2NPs) | TAM | TAM reduction | B16F10 | Anti-CSF-1R siRNA (siCD115) | [66] |

| Iron oxide/carboxymethyldextran nanoparticle | TAM | TAM reprogramming | KP1 | ferumoxytol | [67] |

| Hyaluronic acid -MnO2 nanoparticle | TAM | TAM reprogramming | 4T1 | [46] | |

| cyclodextrin nanoparticles (CDNPs) | TAM | TAM reduction | RAW 264.7 and B16.F10 | TLR7/8-agonist | [68] |

| Lipid NPs (C12-200, cholesterol, PEG-DMG) | TAM | TAM reduction | EL4, CT26 | CCR2 siRNA | [69] |

| Liposome/sialic acid | TAM | TAM eradication | S180 sarcoma | Epirubicin | [70] |

| High-density lipoprotein-like NPs (HDL) | MDSCs | MDSC reduction | B16F10 | lipophilic fluorophore dialkylcarbocyanine (DiD) | [71] |

| Micelles of pply propylene sulfide (PPS) | MDSCs | MDSC depletion | B16F10, E.G7-OVA | 6-thioguanine(TG) | [72] |

| Liposome/DSPE-PEG-PDP | MDSCs | MDSC differentiation | 4T1 | Complement C3 | [73] |

| Mesoporous Silica @ liposome | MDSCs | MDSC differentiation | B16F10 | All trans retinoic acid | [52] |

| Liposome | MDSCs | MDSC reduction | EG07-OVA B16F10 | Lauroyl gemcitabine | [74] |

| Liposome | MDSCs | MDSC depletion | 4T1 | Doxorubicin | [54] |

|

UCNP-PEG-PEI (UPP) nanoparticles upconversion (UCNP) polyethylene glycol (PEG) polyethylenimine (PEI) |

DC | DC activation | C57BL/6 | Antigen ovalbumin (OVA) | [75] |

| Poly(lactic-co-glycolic) acid | DC | DC activation | CT26 | Indocyanine green, imiquimod | [76] |

| HDL mimicking nanodisc | DC | DC activation | B16F10 | CpG ODN, antigen peptide | [20] |

| MoS2 PEG nanosheets | DC | DC activation | C57BL/6 | CpG | [77] |

| A polymer-templated protein nano-ball with thhemagglutinin1 (H1) (H1-NB) | DC | DC Stimulation | C57BL/6 | Ovalbumin (OVA) | [78] |

| Poly(ethylene glycol)-b-poly-2-(hexamethylene-imino) ethyl methacrylate | DC | DC activation | B16F10 MC38 TC | Antigen peptide | [59] |

| D-α-tocopherol polyethylene glycol succinate (TPGS) | DC | DC activation | CT26-FL3 |

The micellar delivery of quercetin (Q) and alantolactone (A) (QA-M) |

[79] |

| Binary cooperative prodrug nanoparticle (BCPN) | DC | DC activation | 4T1 | (oxaliplatin)OXA and NLG919 | [80] |

| Fe3O4 @ SiO2 nanoparticle | NK cell | NK cell migration | RPMI8226 | [50] | |

| Cationic liposome | NK cell | NK cell activation | CMT167 | Plasmid encoding TUSC2 | [49] |

| Cationic liposome | Neutrophil | Neutrophil mediated delivery | G422 | Paclitaxel | [81] |

| Denatured albumin + TA99 Ab | Neutrophil | Neutrophil mediated delivery | B16 | Pyropheophorbide-a | [56] |

| Gold nanoparticle | Neutrophil | Neutrophil mediated delivery | 3LL | [57] |

Nanomaterials for modulating adaptive immune system (AIS)

T-cells and B-cells are components of the AIS. These cells express various clonal antigen receptors and identify an extensive group of antigens expressed by either cancer cells or other pathogens. Indeed, these cells can evolve to memory cells, which can ‘remember’ prior exposures with antigens and begin a quick immune reaction against those that are formerly faced [13].

T-cells have a significant role in the ability of the body to remove tumors and intracellular pathogens. Treatment with adoptive T-cell transfer or checkpoint blockade antibodies are primarily dependent on the strength of the cytotoxic CD8 + T-cells spoil cancer cells and infiltrate tumors, showing significant responses in the clinic. Also, abnormal T-cell reactions cause severe autoimmune disorders like MS and Type 1 diabetes. Hence, some strategies are needed for modulating the activities of T-cells, either increasing or preventing their role in a variety of diseases [82]. Tumor-antigen-specific T-cells that naturally increase in patients, expanded by a cancer vaccine, or presented by adoptive cell treatment may eradicate cancer tissues. The critical point is applying strategies for developing these T-cells, particularly in in vivo or preventing signals that indicate the suppression of the immune system. Hence, nanoparticle delivery factors have been investigated to increase the activity of T-cell-based immunity in various mechanisms.

In this regard, Stephan et al. manipulated cytokine encapsulating multilamellar lipid nanoparticles and linked them (chemically) to T-cells ex vivo previous to adoptive transfer [83]. They reported that conjugating nanoparticles to free thiols on T-cell surface proteins caused minimum particle internalization after several days of culture. Nanocarriers, meanwhile, produce encapsulated cytokines to stimulate modulated autocrine of cell exteriors’ receptors. Since T-cells contained nanoparticle “backpacks” carrying stimulatory cytokines, this procedure could show 80-fold enhanced T-cell proliferation in vivo and notable developments in the ACT efficacy, with no harmful effect (i.e. toxicity). Thus, particle-decorated T-cells could capture tumor tissues. Besides, it was shown that cell-bound nanoparticles could be moved from the cell’s surface into the tumor cell/T-cell interface (i.e. synapse-directed drug delivery) [83]. Kwong et al. have also used nanoparticles to carry protective or stimulatory cues to T-cells in the tumor microenvironment [84]. They created immunostimulatory liposomes while the surface of PEGylated liposomes was conjugated with IL-2 and anti-CD137. Such particles are intended to administer high doses of IL-2 and anti-CD137 into tumors without systemic diffusion. Therefore, local stimulation of T-cell was done without systemic toxicity. After intratumoral administration of anti-CD137 and IL-2 fixed on liposomes into melanomas, which caused ameliorated proportions of tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T-cells to regulatory T-cells (T-regs), treated about 70% of subjects, and primed T-cells that were not close to the administration site to stop the proliferation of other tumor cells [84].

Nanoparticles are also used for treating autoimmune diseases by enabling preferred re-modification of autoreactive T-cells. For example, T1D is because of CD8+ T-cells, which identify several epitopes secreted by islet cells of the pancreas. Therefore, Tsai et al. reported that activation of self-antigen-specific CD8+ T-cells through iron oxide nanoparticles linked with pMHC-NPs increased the number of autoregulatory memory-like T-cells [85]. Hence, such autoregulatory memories-like T-cells inhibited the stimulation of autoreactive CD8+ T-cells via knocking out of APCs capable of presenting auto-antigens. Table 2 shows other nanomaterials used for regulating adaptive immune (T-cells) cells for immunotherapy [85].

Table 2.

Characteristics of nanoparticles used as platforms for immunotherapy to modulate T- cells

| Nanoparticles (NPs) | Size | Payload | Tumor model | Effects | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coated/conjugating | Encapsulated | |||||

| Trimethylchitosan complex | 150 nm | Paclitaxel (PTX) and DNA encoding (GM-CSF)-Fc | HeLa and B16 melanoma cells |

Nano-complex upregulated the co-stimulatory molecules of CD80 and CD86, promoted the proliferation of CD4 + and CD8 + T cells, reduced the generation of immunosuppressive FoxP3 + Treg cells Nano-complex increased immune stimulation and reduced immune escape inhibited tumor growth and prolonged survival in vivo |

[86] | |

| Cationic liposome | 160 nm | Monophosphoryl lipid A (MPLA) and mRNA encoding OVA | N/A | Liposome induced high antigen expression and active antigen-specific T cell immunity in vivo without provoking a type I IFN response | [87] | |

| poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) | 72.2–656 nm | OVA | Proteolipid peptides (PLP) | N/A |

Immune cells’ cellular interaction induced by 80 nm PLGA NP was significantly lower than the 400 nm PLGA NP Induction of Tregs was particle size and concentration-dependent |

[88] |

| Lipid-calcium-phosphate (LCP) | 58 nm | Anti-CTLA-4 antibody and mRNA encoding tumor antigen MUC | Murine TNBC 4T1 mammary carcinoma | Nanoliposome targeted to mannose receptors on DCs, led to tumor antigen expression and induced a strong, antigen-specific CTL response against tumor cells | [89] | |

| Lipid-calcium phosphate | 73 nm | Sunitinib; Trp2, CpG, | Murine B16F10 melanoma |

Increasing cytotoxic T-cell infiltration Decreasing the number and percentage of MDSCs and Tregs in the TME, Inducing a shift in cytokine expression from Th2 to Th1 type in tumor |

[90] | |

| Lipid-PLGA/tLyp1 | 10–200 nm | (PEG-DSPE) and (DPPC) | Imatinib, anti-CTLA-4 mAb | Murine B16 melanoma |

Prolonging survival rate, Enhancing tumor inhibition Reducing intratumoral Treg cells Elevating intratumoral CD8 + T cells against tumor were observed when combined with checkpoint-blockade by using anti-cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen-4 antibody |

[91] |

| Carbon nanotubes (PEG-SWCNTs)/anti-GITR mAb | 101 nm | Fluorochrome | Murine B16 melanoma |

Naturally increased intratumor Treg vs. effector T cell (Teff) ratio Active targeting of markers that are enriched in intratumor vs. splenic Treg |

[92] | |

| lipid-protamine-DNA (LPD) | 129 nm | Cationic liposomes (DOTAP and cholesterol) | PD-L1 trap plasmid | BALB/c C57BL/6 mice | CD8 + T cells, CD4 + T cells and activated DCs were significantly increased inside the tumor of colorectal cancer | [93] |

| Lipid (nanoscale coordination polymer (NCP) core–shell nanoparticles) | 73.8–103.4 nm | Lipid bilayer containing a cholesterol-DHA | Oxaliplatin (OxPt) and dihydroartemisinin (DHA) prodrugs | BALB/c and C57BL/6 mice | Effective combination therapy can increase the intratumoral infiltration of CD8 + T cells to increase the response rate in colorectal cancer significantly | [94] |

| poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) | –- |

1:TDPAs 2:amine- polyethylene glycol (NH2-PEG) (NH2 AC-NP) 3: 1,2-Dioleoyloxy-3-(trimethylammonium)propane (DOTAP AC-NP) |

B16F10 melanoma | AC-NPs induced expansion of CD8 + cytotoxic T cells Increased both CD4 + /Treg and CD8 + /Treg ratios | [95] | |

| Nitric oxide (NO) | 120 nm | Dinitrosyl iron complex (DNIC) | C3H/HeNCrNarl male mice and nude male mice | Inceasing tumour-infiltrating T cells,CD8 + and CD4 + in liver cancer | [96] | |

| PLGA-PEG-Mal | 166.9 ± 6.5 nm | Conjugating aPD1 and aOX40 | B16F10 melanoma and C57BL/6 mice |

Increasing the ratio of CD8 + to regulatory T-cells infiltrating the tumor Inducing higher T-cell activation |

[97] | |

| MnO2 | 15 nm |

Allylamine hydrochloride (PAH) polyethylene glycol (PEG) |

Female Balb/c mice | CD4 + and CD8 + T cells are essential to the abscopal effect in inhibiting distant tumor | [98] | |

| CaCO3 nanoparticles | 100 nm | The anti-CD47 antibody in the fibrin gel | Female C57BL/6 mice | Increasing CD8 + T cells | [99] | |

| Alginate (ALG) | 310 nm | OVA | Murine E.G7-OVA T-lymphoma |

Alginate NPs enhanced in vivo trafficking of OVA to draining lymph nodes and strengthened cross-presentation of OVA to T cell hybridoma Alginate NPs induced primary CTL response and the inhibition of tumor growth in vivo |

[100] | |

| Organosilica | 200 nm | OVA and TLR agonist (CpG) | Murine B16-OVA melanoma |

OVA- and CpG-Organosilica NP decreased GSH level Increasing ROS level in vitro and in vivo Facilitating CTL proliferation, reducing tumor growth and prolonged survival in melanoma mice model |

[101] | |

| Layered double hydroxide (LDH) | 108.4 nm | Neo-epitopes and CpG | Murine B16F10 melanoma | LDH-NP induced significantly higher CTL activity and inhibited melanoma growth in vivo | [102] | |

| Hollow mesoporous silica (HMS) nanospheres | 3–6 nm | OVA | C57BL/6 mice | Improving the population of CD4 + and CD8 + effector memory T cells in the bone marrow | [103] | |

| Polyplex | –– | Salmonellae | B16 melanoma | Bacterium-based vaccines can induce systemic T cell responses including polyfunctional cytokine-secreting CD4 + and CD8 + T-cells | [104] | |

| Liposomes and liposome-like synthetic | 100–300 nm |

Cytokines IL-15, IL-21 |

C57Bl/6 mice | Increaasing CD8 + , CD4 + and memory T | [83] | |

| Lipid | 100–300 nm | Conjugating NSC-87877-loaded NPs to the surface of tumor-specific T cell | SHP1/2 PTPase inhibitor | Male C57BL/6 albino mice | Increasing CD8 + in prostate cancer | [105] |

| Synthetic high-density lipoprotein (sHDL)– like nanodiscs | 50 nm | Conjugated DOX to 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphothioethanol (PTD) with an N-b-maleimidopropionic acid hydrazide (BMPH) cross-linker | BALB/c or C57BL/6 mice, | sHDLwih DOX + aPD-1 therapy recruited the highest frequency of CD8a + T cells into the tumor microenvironment of colorectal cancer | [106] | |

| Tumor-targeted lipid-dendrimer-calcium-phosphate (TT-LDCP) | 110.5 nm |

1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphate (DOPA), 1,2-dioleoyl3-trimethylammonium-propane (DOTAP), cholesterol, and (DSPE-PEG2000) |

siRNA/pDNA | C3H/HeNCrNarl male mice |

Increasing tumoral infiltration and activation of CD8 + T cells Augmenting the efficacy of cancer vaccine immunotherapy, and suppressed HCC progression |

[2] |

| Poly lactic-co-glycolic acid(PLGA) | 209.8 nm | Agonistic α-CD40-mAb | B16-OVA Subcutaneous tumor | Co-encapsulating Ag and adjuvants efficiently drive specific T cell responses and attractive method to improve the efficacy of protein-based cancer vaccines | [107] | |

The humoral immune response (B cells) plays a unique role by exploiting both antigen-specific effector cells and APCs. B cells maintain the extracellular spaces of the host and are critical for free pathogens clearance. Prevention (i.e. through vaccines) is the best approach to get prolonged conservation against contagious agents using humoral immune reactions. Licensed vaccines were protected via stimulating neutralizing antibody reactions. Therefore, introducing nanoparticles to increase the activation and engagement of antigen-specific B-cells plays a vital role in vaccine development [108]. Nanoparticles of biological sources like virus-like particles (VLPs), exosomes, inactivated and weakened viruses have been widely applied in various vaccines to ameliorate the antibody activities. Such vaccines’ proficiency relies on repetitive particulate antigens for activating responses of the B-cell, which act simultaneously with the monovalent ligation of the B-cell receptors (BCR) [109].

A little evidence is available regarding the tumur stimulated immunologic functions of B cells, which consist of a different subset of functions, and their modulation has an essential effect on tumoricidal function. Moreover, those stimulated by the BCR pathway, TLR, and microRNA pathway can show antitumor immunity by secreting antibodies, chemokines, and cytokines, which are naive APCs, and organizing tertiary lymphoid structures [110].

Plasma cells that are a subset of B cells can generate antibodies that cause antitumor reactions like complement-dependent cytotoxicity (CDC) and antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC). Furthermore, mature follicular B cells can evolve to Be-1 and -2 and generate cytokines like IL-2, -12, TNF-α, IFN-γ for increasing antitumor Immunity of NK and T cells. By stimulating the CD40-CD40 ligand (CD40L) signaling pathway, B cells turn into naive APCs in cancer tissues. They can conserve the survival and growth of T cells that can infiltrate cancer cells for lasting antitumor reactions.

Antitumor immunity, which is negatively regulated by regulatory B cells (B regs), is triggered by a variety of mechanisms:

B regs secret mediators that can suppress the immune system like cytokines and IDO-1, which prevent the activation and proliferation of NK as well as T cells.

B regs inactivate cells that can stimulate the immune system by expressing regulators of the immune system like PD-1.

B regs upgrade the progression of cancer tissues by producing TGF-β for EMT.

When B regs produce the death-stimulating molecule Fas ligand (FASL), they, in turn, stimulate the death of effector T cells.

As specified above, using antibodies against programmed cell death-1 (PD-1), programmed cell death ligand-1 (PD-L1), and the role of PD-1 inhibitors in non–small cell lung cancer, melanoma, and bladder, renal, and head and neck cancers, as well as Hodgkin’s lymphoma, is well proved. Recently, various immunotherapeutic antibodies accompanied with nanoparticles as drug delivery were confirmed by the US FDA (Table 3). Thus, approaches applied to transform or target B regs can create a therapeutic potential for improving antitumor immunotherapy. For example, Schmid et al. targeted CD8+ T-lymphocytes by the PD-1 antibody after eliminating the Fc fragments and connecting to poly (D, L-lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) nanoparticles [111]. Furthermore, the nanoparticle covers an inhibitor of TGF-β, which is useful for immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment preservation and immune adjuvants TLR7/8 agonists. Then, PD-1 positive T-lymphocytes were targeted in tumor tissue and blood. The TGF-β inhibitors and TLR7/8 agonists increased the immune reactions, enhanced the vulnerability of the tumor to subsequent anti-PD-1 therapies, and enhanced the ratio of CD8 T-lymphocytes that can infiltrate the tumor. They reported a macrophage dual-targeted CpG-loading nanoparticle created by mannosylated carboxymethyl Chitosan and hyaluronan (HA). This nanosystem caused enhanced secretion of proinflammatory cytokines, phosphoinositide 3-kinase/Akt signal pathways, activated NF-κB, and stimulated Fas/FasL-mediated cell death in models developed for breast cancer [111]. As mentioned above, B cells are indirectly affected by this nanosystem like that some of these immunity mechanisms that regulate negatively via regulatory B cells. When B-lymphocyte receptors are interconnected, B-cell growth and differentiation into plasma cells that can produce particular antibodies are begun. Temchura et al. [112] were demonstrated biodegradable calcium phosphate nanoparticles that have protein antigens on their exterior and provided the efficacy of the B-cell stimulation following the presentation to the nanoparticles mentioned above. The nanoparticles were activated with the model antigen Hen Egg Lysozyme (HEL) and preferentially internalized and limited by the tumor antigen-specific B-lymphocytes. Co-generation of HEL-specific B-cells with activated nanoparticles enhanced exterior production of B-cell stimulator markers and induced high humoral immunity. Nanoparticles can cross-link B-cell receptors effectively at the exterior of antigen-matched B-cells. Furthermore, it is found that their efficiency is significantly higher (about 100-times) in activating B-cells, compared to the soluble shape of tumor antigen. Hence, these nanoparticles covered with protein antigens are appropriate vaccines for humoral immunity [112].

Table 3.

List of cancer immunotherapeutic antibodies along with nanoparticles as drug delivery approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)

| Drug/treatment | Type of cancer | Drug type (target) | Approval | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Durvalumab (Imfinzi®) | Locally advanced or metastatic bladder cancer | Monoclonal antibody (PD-L1) | Approved | 2017 |

| Avelumab (Bavencio®) | Locally advanced or metastatic bladder cancer | Monoclonal antibody (PD-L1) | Approved | 2017 |

| Nivolumab (OPDIVO®) | Classical Hodgkin lymphoma (cHL) | IgG4 kappa monoclonal antibody (PD‐1) | Approved | 2016 |

| Atezolizumab (Tecentriq®) | Locally advanced or metastatic bladder cancer | Monoclonal antibody (PD-L1) | Approved | 2016 |

| Pembrolizumab (Keytruda®) | Advanced refractory melanoma and non–small cell lung cancer | Monoclonal antibody (PD-L1) | Approved | 2014 |

| Nivolumab (Opdivo®) | Unresectable or metastatic melanoma squamous non–small cell lung cancer | Monoclonal antibody (PD-L1) | Approved | 2014 |

As efficient adjuvants in the formulation of antitumor vaccine are critical, Yan et al. were examined two-layered double hydroxide (LDH) nanoparticles and nanosheets (NSs) as adjuvants to stimulate the immune reactions for antitumor purposes [113]. They showed that immunogen ovalbumin (OVA) carried by both nanomaterials could induce more robust humoral and cell-mediated immune reactions, combined with an immune stimulant (i.e. TLR9 ligand CpG), as documented using increased levels of IgG1, IgG2a, and interferon-γ. Also, LDH NSs presented enhanced function to increase particular antibody activities compared with LDH NPs. It was found that immunizing mice with OVA-CpG vaccines developed with both nanomaterials, presented more robust inhibition of the inoculated tumor proliferation. Besides, an increased survival is reported [113]. In another study, Martucci et al. demonstrated a novel drug delivery mechanism for active targeting of B-cell lymphoma [114]. A novel customized B-cell lymphoma treatment, which uses a site-specific receptor-mediated drug delivery system and natural silica-based nanoparticles (diatomite), have been altered to target the antiapoptotic factor B-cell lymphoma/leukemia 2 (Bcl2) with small interfering RNA (siRNA). Aggressive murine A20 lymphoma cells, using as ligand an idiotype-specific peptide (Id-peptide) endowed with high affinity into the B-cell receptor. This Id-peptide was applied as a homing to assure the specific targeting of target cells. Diatomite nanoparticles (DNPs) loaded with siRNA directed against Bcl2 and conjugated with an Id-peptide, powerfully produced in the majority of B-cell lymphomas, are provided as a ligand-mediated delivery system. Hence, specific uptake of nanoparticle guided using the Id-peptide was increased by three times in target cells than nonspecific myeloma cells. When a random control peptide was exploited, instead of Id-peptide, and siRNA was administered to modified nanoparticles, the specific internalization yield was increased fourfold [114].

In conclusion, gene silencing has a high biological role and provides a chance for customized lymphomas. As mentation above, B cells are closely related to APCs and T cells, and most of their functions in cancer suppression are based on modulating and regulating T cells. So, B cells are frequently considered as helper cells during immunotherapy.

B cell-targeting nanoparticles for immunotherapy in infectious diseases

Another aspect of immunotherapy using nanoparticles can be observed in the immune response to infectious diseases. The immune reaction to local microbial agents and vaccines has induced the investigation of synthetic nanoparticles that contain identical structural features in antigen represent to enhance humoral immunity. Engineered nanoparticles offer flexibility over the manner of particulate antigen presentation. On the other hand, the surface presentation of peptide and protein antigens on nanoparticle exterior imitating bacterial and viral agents can conjugate and stimulate antigen-specific B cells with an increased rate compared to encapsulated antigens [115].

Friede et al. showed that, at similar doses, liposomes with surface-bound peptide antigens exploited a more robust B-cell reaction than those with encapsulated peptide antigens [116]. Protein conjugated on the exterior of calcium phosphate nanoparticles increases linking of BCR in vitro, with increased effectiveness in stimulating antigen-specific B cells than soluble proteins. Furthermore, many physicochemical factors can affect the function of nanoparticles to involve B-cells. In this regard, Stefanick et al. demonstrated how peptide linker length, peptide capacity, PEG coating density, peptide hydrophilicity, and PEG linker length could considerably change cellular absorption for peptide-functionalized liposomes that bind to targeted cells [117].

More silica, gold, and calcium phosphate nanoparticles (CaP) have been applied for developing vaccines in the past decade. Compared to biologic or nanoparticles based on polymer, they pose more benefits in feasibility, generation, safety, and storehouse costs. For instance, Zilker et al. reported that CaP coated with proteins effectively activates antigen-specific B-cells in vitro [118]. They showed that immunization with CaP-nanoparticles elicits more robust responses compared to monovalent antigens. Furthermore, the function of the CaP-nanoparticles with TRL-ligands can modulate the level of mucosal IgA antibodies and the IgG subtype response. Also, the functionalization of CaP with CpG or T-helper cell epitopes provides overcoming the absence of T-helper cells. Hence, their results indicate that CaP nanoparticle-based B-cell targeting vaccines functionalized with TLR-ligands can be used as a multiplatform to dramatically modulate and induce humoral immune responses in vivo [118].

Another study was reported by Kasturi et al., who developed a vaccine based on nanoparticles, like a virus, in composition and size [119]. They used a biodegradable synthetic PLGA to synthesize ~ 300 nm nanoparticles with TLR4, TLR7, or both ligands with an antigen. Immunization of mice with this composition considerably enhanced antigen-specific serum IgG titer against influenza virus hemagglutinin than immunization with a single TLR agonist. A remarkable characteristic of the immune response stimulated by this vaccine is the induction of long-lived germinal centers (GCs) and continuous antigen-specific B and T cell responses, similar to those observed with viral infections. In conclusion, encapsulated TLR4 and TLR7 ligand in PLGA formulations increase the GC mechanism of memory B cell development and prolonged plasma cell reactions [119]. Almost all studies have found that nanoparticle surface-indicated antigens can increase high-affinity antibodies compared to soluble antigen immunization and the formation of the germinal center (GCs).

Conclusion and promising perspective of future

In sum, nano-based cancer immunotherapy is still in its initial stage but has succeeded in improving cancer vaccines’ safety and efficacy. This fast-developing field has attracted many researchers to make applicable the theoretical thesis in the experimental exploitation. Nevertheless, there are 295 clinical trials recorded on the NIH clinical trials website (https://clinicaltrials.gov/) that aim to assess the impact of diverse nanoparticles on various cancers (“Search of: Nanoparticles|Cancer—Search was done at Date 2021-March 11th).

Nanotechnology combined with biocomputing capabilities has the potential to enable the development of sophisticated nanorobotic devices for a wide range of biomedical applications, including intelligent sensors and new therapeutic agents. DNA/RNA-based computing techniques have been developed recently that may have innovative clinical applications, such as analysing cells and delivering agents [120]. However, the effectiveness and complexity of this field remain largely unknown in cancer immunotherapy. Cellular “hitchhiking,” or the use of cells as vehicles for the co-delivery of cancer therapeutics and nanoparticles to the target tissue, is a novel strategy for extending the circulation of nanoparticles [121].

Perhaps it can be concluded that significant primary progress in the administration of nanoparticles in immunotherapy for those with cancer includes illustrating and adjusting the function of immune cells in the context of the tumor microenvironment. However, polymeric nanoparticles are the most investigated nanomaterials in cancer immunotherapy for delivery systems of drugs and immune factors. Moreover, the importance of gold nanoclusters, liposomes, inorganic porous material in this field should not be overlooked [122]. The biomaterial research field’s development currently provides significant opportunities for successful Nanobiotechnology’s clinical trials as an advanced technology in medicine. According to our review, over the last 20 years, many nanoparticle-based ingredients, including encapsulated or conjugated cytotoxic drug delivery systems, have entered clinical trials. There is great promise for nanotechnology to achieve clinical translations of biomedical applications and clinically relevant diagnostic and therapeutic multifunctional systems. Due to the unique features of these products, some critical issues are entirely investigated. The new investigation focused on producing non-toxic, non-immunogenic, stable, completely biocompatible, and reusable administration with little or no side effects for cancer patients. These features make nanotechnology-based products an excellent candidate for personalized medical planning. Indeed, some of the effective nanoparticle therapeutic outcomes used in cancer immunotherapy help quickly translate engineered nano-immunotherapeutics into cancer management clinics.

Acknowledgements

The authors did not recipe any financial support for the research. I want to acknowledge and give my thanks to Elham Geravandi, who help us for revising the manuscript.

Author contributions

AG contributed to the study’s conception and design. The first draft of the manuscript was written by AG, LMA and AA, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. Finally, all authors read, approved, and revised the final manuscript.

Data availability

NA.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

Informed consent

Not applicable.

Research involving human and/or animals participants

The authors declare that there is no research on human participants or animals.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Ali Golchin, Email: agolchin.vet10@yahoo.com, Email: golchin.a@umsu.ac.ir.

Arezo Azari, Email: azari.arezo@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Liu Y, Zeng G. Cancer and innate immune system interactions: translational potentials for cancer immunotherapy. J Immunother. 2012;35:299–308. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e3182518e83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huang K-W, Hsu F-F, Qiu JT, et al. Highly efficient and tumor-selective nanoparticles for dual-targeted immunogene therapy against cancer. Sci Adv. 2020;6:eaax5032. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aax5032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goldberg MS. Immunoengineering: how nanotechnology can enhance cancer immunotherapy. Cell. 2015;161:201–204. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Park W, Heo YJ, Han DK. New opportunities for nanoparticles in cancer immunotherapy. Biomater Res. 2018;22:24. doi: 10.1186/s40824-018-0133-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Singh AK, McGuirk JP. CAR T cells: continuation in a revolution of immunotherapy. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:e168–e178. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30823-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kalbasi A, Ribas A. Tumour-intrinsic resistance to immune checkpoint blockade. Nat Rev Immunol. 2020;20:25–39. doi: 10.1038/s41577-019-0218-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chulpanova DS, Kitaeva KV, Green AR, et al. Molecular aspects and future perspectives of cytokine-based anti-cancer immunotherapy. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2020;8:402. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2020.00402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Melero I, Gaudernack G, Gerritsen W, et al. Therapeutic vaccines for cancer: an overview of clinical trials. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2014;11:509–524. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2014.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zamarron BF, Chen W. Dual roles of immune cells and their factors in cancer development and progression. Int J Biol Sci. 2011;7:651–658. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.7.651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lei X, Lei Y, Li JK, et al. Immune cells within the tumor microenvironment: Biological functions and roles in cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Lett. 2020;470:126–133. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2019.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.You M, Peng L, Shao N, et al. DNA “Nano-Claw”: logic-based autonomous cancer targeting and therapy. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:1256–1259. doi: 10.1021/JA4114903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Golchin A, Hosseinzadeh S, Roshangar L. The role of nanomaterials in cell delivery systems. Med Mol Morphol. 2017;51:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s00795-017-0173-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Irvine DJ, Hanson MC, Rakhra K, Tokatlian T. Synthetic nanoparticles for vaccines and immunotherapy. Chem Rev. 2015;115:11109–11146. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ardeshirylajimi A, Golchin A, Khojasteh A, Bandehpour M. Increased osteogenic differentiation potential of MSCs cultured on nanofibrous structure through activation of Wnt/β-catenin signalling by inorganic polyphosphate. Artif Cells Nanomed Biotechnol. 2018;46:S943–S949. doi: 10.1080/21691401.2018.1521816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yan S, Zhao P, Yu T, Gu N. Current applications and future prospects of nanotechnology in cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Biol Med. 2019;16:486–497. doi: 10.20892/j.issn.2095-3941.2018.0493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Qian H, Liu B, Jiang X. Application of nanomaterials in cancer immunotherapy. Mater Today Chem. 2018;7:53–64. doi: 10.1016/j.mtchem.2018.01.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith MJ, Brown JM, Zamboni WC, Walker NJ. From immunotoxicity to nanotherapy: the effects of nanomaterials on the immune system. Toxicol Sci. 2014;138:249–255. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfu005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maeda H, Tsukigawa K, Fang J. A retrospective 30 years after discovery of the enhanced permeability and retention effect of solid tumors: next-generation chemotherapeutics and photodynamic therapy-problems, solutions, and prospects. Microcirculation. 2016;23:173–182. doi: 10.1111/micc.12228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Azzi J, Tang L, Moore R, et al. Polylactide-cyclosporin A nanoparticles for targeted immunosuppression. Faseb j. 2010;24:3927–3938. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-154690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuai R, Ochyl LJ, Bahjat KS, et al. Designer vaccine nanodiscs for personalized cancer immunotherapy. Nat Mater. 2017;16:489–496. doi: 10.1038/nmat4822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jacqueline C, Bourfia Y, Hbid H, et al. Interactions between immune challenges and cancer cells proliferation: timing does matter! Evol Med Public Heal. 2016;2016:299–311. doi: 10.1093/emph/eow025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Malaguarnera L, Cristaldi E, Malaguarnera M. The role of immunity in elderly cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2010;74:40–60. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Facciabene A, Motz GT, Coukos G. T-regulatory cells: key players in tumor immune escape and angiogenesis. Cancer Res. 2012;72:2162–2171. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bowdish DME. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells, age and cancer. Oncoimmunology. 2013 doi: 10.4161/onci.24754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]