Abstract

Alcohol and opioids are two major contributors to so-called deaths of despair. Though the effects of these substances on mammalian systems are distinct, commonalities in their withdrawal syndromes suggest a shared pathophysiology. For example, both are characterized by marked autonomic dysregulation and are treated with alpha-2 agonists. Moreover, alcohol and opioids rapidly induce dependence motivated by withdrawal avoidance. Resemblances observed in withdrawal syndromes and abuse behavior may indicate common addiction mechanisms. We argue that neurovisceral feedback influences autonomic and emotional circuits generating antireward similarly for both substances. Amygdala is central to this hypothesis as it is principally responsible for negative emotion, prominent in addiction and motivated behavior, and processes autonomic inputs while generating autonomic outputs. The solitary nucleus (NTS) has strong bidirectional connections to the amygdala and receives interoceptive inputs communicating visceral states via vagal afferents. These visceral-emotional hubs are strongly influenced by the periphery including gut microbiota. We propose that gut dysbiosis contributes to alcohol and opioid withdrawal syndromes by contributing to peripheral and neuroinflammation that stimulates these antireward pathways and motivates substance dependence.

Keywords: substance use disorders, alcohol, opioid, withdrawal, Microbiome, gut-brain axis, Amygdala, Inflammation

INTRODUCTION

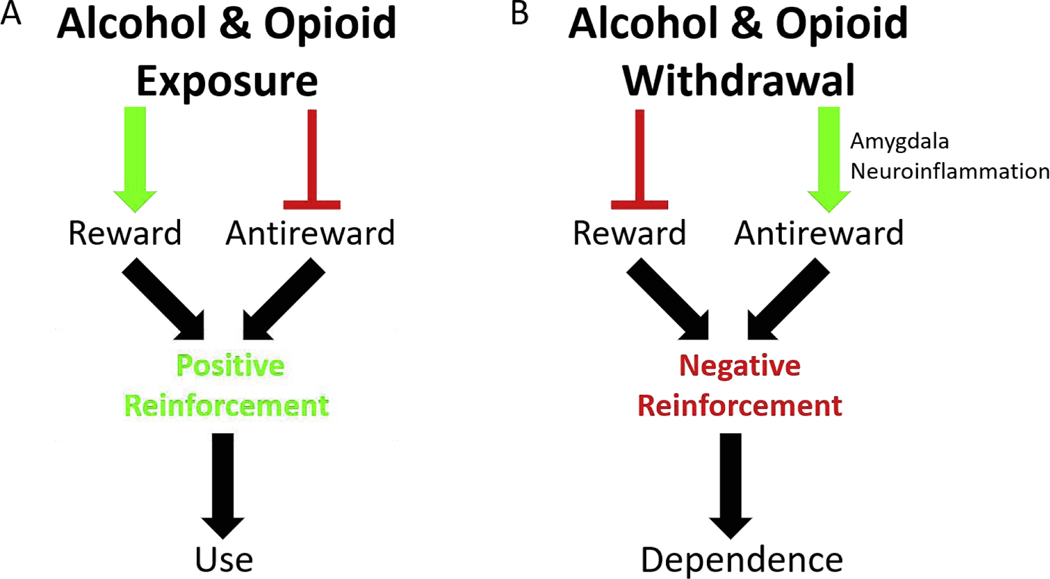

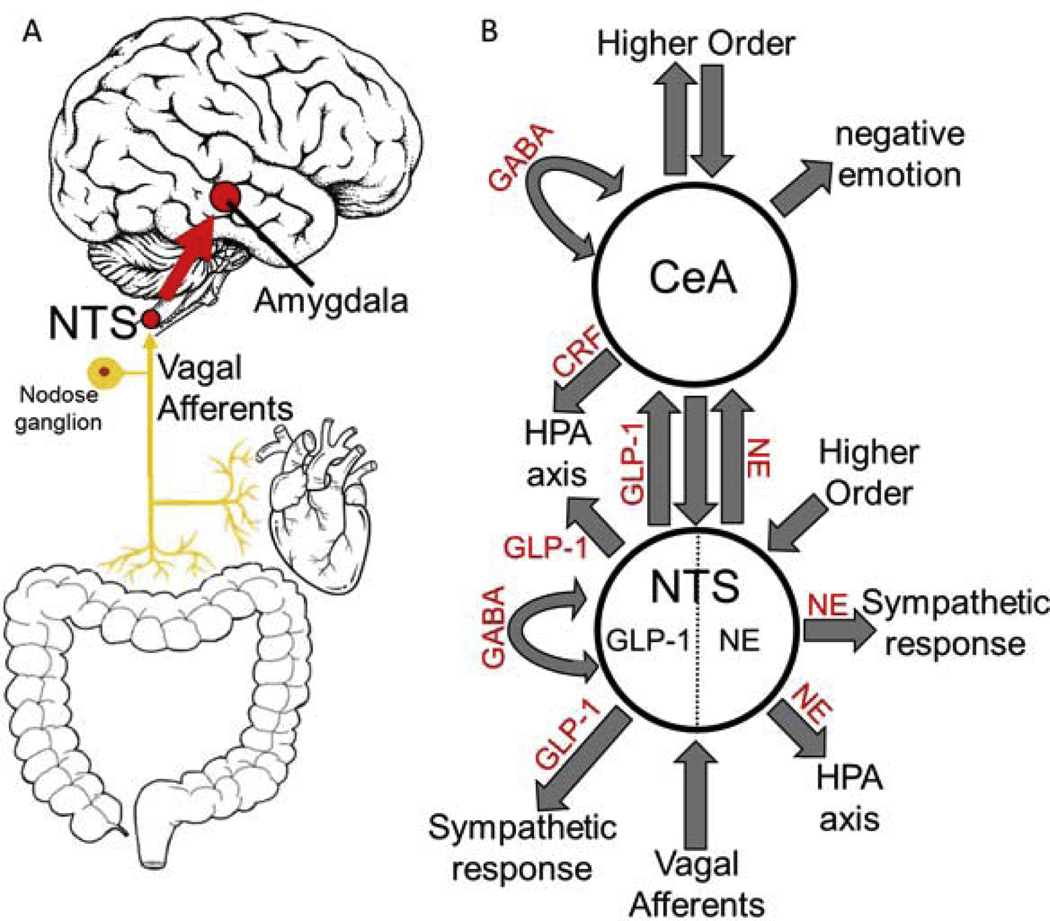

Drug addiction is commonly defined as compulsive drug-seeking coupled with failure to restrain intake (Koob and Le Moal, 2001). Models of addiction include positive and negative reinforcement mechanisms; both are supported by literature (Wise and Koob, 2014) (Fig. 1). Herein, we focus on the recent emergence of evidence suggesting inflammation may be a common driver of negative reinforcement for substances of different classes: alcohol and opioids (Crews, Zou and Qin, 2011; Jacobsen, Hutchinson and Mustafa, 2016). These substances have some similarities—activation of the mesolimbic dopamine (DA) pathway and severe withdrawal syndromes—but their mechanisms of action and psychoactive effects are distinct. Worryingly, both alcohol and opioids are widely abused and rates of overdose are increasing (CDC) (Jannetto, 2021). This review explores a visceral-emotional neuraxis possibly responsible for some of these observations (Fig. 2). We make a case for this visceral-emotional neuraxis as a common pathway that motivates drug-seeking in both alcohol and opioid dependence and as an auspicious clinical target for substance dependence and mental health treatments generally (O’Sullivan et al., 2019; O’Sullivan, 2020).

Figure 1. Schematic of Opponent-Process Model.

(A) Alcohol and/or opioid exposure has two effects: Stimulate reward, via the mesolimbic dopamine pathway, and inhibit antireward. These effects motivate substance use via positive reinforcement (B) Alcohol and/or opioid withdrawal has two effects. Inhibit reward, by inhibiting the mesolimbic dopamine pathway (not shown), and stimulate antireward. This review proposes that amygdala neuroinflammation mediated primarily by astrocytes is an endpoint in antireward stimulation in alcohol and opioid withdrawal, though this hypothesis warrants further testing. These effects, whatever the mechanism, motivate substance dependence via negative reinforcement.

Figure 2. Interoceptive Vagal Circuit and Visceral-Emotional Neuraxis.

(A) Interoceptive vagal afferents relay the state of the gut, which is highly influenced by gut microflora, and other peripheral organs to the nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS). This information is subsequently relayed to the amygdala and influences emotional states. (B) A simplified cartoon representation showing the integrative roles of the nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS) and the central nucleus of the amygdala (CeA) in emotion, stress, and autonomic regulation. Two neuronal subtypes, GLP-1 and NE neurons, are highlighted. Many anatomical and functional connections are omitted for clarity (NE, norepinephrine; GLP-1, glucagon-like peptide 1; GABA, γ-aminobutyric acid; HPA axis, hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis; CRF, corticotropin releasing hormone).

We define dependence as the induction of a state or network of allostasis. Allostasis describes an often maladaptive homeostasis or set point established in response to the persistent presence of a xenobiotic (Koob and Le Moal, 2001). Tolerance to doses of the xenobiotic that previously produced a physiologic or psychoactive effect is a defining symptom and reflects biological networks that have adapted or compensated for the persistent presence of the xenobiotic. In the state of dependence, the xenobiotic is required for this novel allostatic network to function optimally. In the absence of the xenobiotic, the often more fragile less robust allostatic network is overcompensated. In the case of substances of abuse, abstinence exposes this network fragility and the resulting network decompensation incites a withdrawal syndrome characterized by negative physical and emotional symptoms. Solomon & Corbit’s opponent-process model (1974) theorized that avoidance of these severe withdrawal symptoms motivates drug-seeking by providing negative reinforcement for continued substance dependence (Fig. 1). In this discussion, we refer to peripheral network decompensation as the biochemical state peripheral tissues experience during an acute withdrawal. Such decompensation, both peripheral and central, we argue is the basis of antireward. We define antireward as neurological circuits that when stimulated motivate behavior by negative reinforcement or when inhibited motivate behavior by positive reinforcement (Fig. 1). Herein, we implicate the visceral-emotional nuclei amygdala and solitary nucleus (NTS) as hubs for negative emotion stimulated in withdrawal by neurovisceral and other systems secondary to peripheral network decompensation that generate antireward (Figs. 1–2).

The mesolimbic DA pathway is one of the most studied circuits in addiction and thought to contribute principally to drug-seeking (Pierce and Kumaresan, 2006; Wise, 2008). This reward pathway is exogenously stimulated by most substances of abuse motivating incentive-based use (Fig. 1). Dependence (allostasis) followed by abstinence decreases mesolimbic DA signaling and a loss of reward (i.e. reward deficiency syndrome) is experienced as anhedonia. (Wise, 2008; Wise and Koob, 2014; Gold et al., 2018). The mesolimbic reward pathway has been clinically targeted directly and indirectly in addiction treatments with some success (Moreira and Dalley, 2015; Gold et al., 2018). However, skepticism has emerged concerning the comprehensiveness of this pathway in motivating addiction (Pierce and Kumaresan, 2006; Wise and Koob, 2014; Abrahao, Salinas and Lovinger, 2017; Gold et al., 2018). Koob & Le Moal (2008) propose that substances of abuse not only stimulate the mesolimbic reward pathway, but also suppress other less defined antireward pathways (Fig. 1).

This antireward model suggests that substance use and abuse are primarily motivated by decreasing negative emotion and dysphoria as opposed to increasing positive emotion and euphoria. There is convincing evidence to support both sides of this argument (Pierce and Kumaresan, 2006; Koob and Le Moal, 2008; Wise and Koob, 2014; Gold et al., 2018). We recognize the attractiveness of the reward model due to its well-defined involvement in substance dependence and parsimony, and instead focus on the antireward model as an understudied and underappreciated contributor in alcohol and opioid dependence. That is, mesolimbic reward is necessary but not sufficient in explaining addiction behavior. We explore antireward-driven negative reinforcement in the context of the well-established human negativity bias which describes the disproportionate behavioral influence of negative emotion on motivated behavior (Vaish, Grossmann and Woodward, 2008). Additionally, the visceral-emotional neuraxis (Fig. 2) and gut microflora have proven integral to physical and mental health to such an extent that we propose this antireward circuit likely has broader implications in mental health and so-called deaths of despair generally (Berthoud and Neuhuber, 2000; VanBuskirk and Potenza, 2010; Mayer, 2011; Maniscalco and Rinaman, 2018). We recognize that this hypothesis is similar to reward deficiency anhedonia which appreciates the importance of negative affective states influenced by the amygdala that motivate drug-seeking. We differ in our emphasis on peripheral feedback, inflammatory signaling, and gut microflora and by explicitly connecting the opponent-process model to antireward (Figs. 1–2).

Exogenous suppression of antireward pathways by substances of abuse implies activation of antireward pathways in withdrawal based on the opponent-process model (Fig. 1). This conjecture is supported with evidence of activation of stress pathways in alcohol and opioid withdrawal involving corticotropic releasing factor (CRF) activating the amygdala and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis (Heilig and Koob, 2007; Koob, 2009; Abrahao, Salinas and Lovinger, 2017; Gold et al., 2018). Additionally, amygdala is hyperactive in opioid craving and depressed with methadone administration in functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies in opioid-dependent people (Langleben et al., 2008; Murphy et al., 2018) Alcohol use also reduces amygdala activity and hyperactivity in amygdala-orbitofrontal circuits predicted future alcohol use in fMRI studies (Gorka et al., 2013; Peters et al., 2017) We provide additional evidence for the suppression of antireward pathways in alcohol and opioid use as well as the activation of antireward pathways in alcohol and opioid withdrawal below. Our studies suggest that inflammation in the amygdala, a limbic center wired for threat detection, and the activation of astroglia in particular, may be an important contributor to the severe negative emotion experienced in both alcohol and opioid withdrawal (O’Sullivan et al., 2019). Neurovisceral feedback is likely involved in this observation considering the established circuitry (Fig. 2). Thus, we hypothesize that peripheral network decompensation, and gut microflora dysbiosis in particular, incited by substance abstinence drive limbic neuroinflammation and subsequently contribute to the negative physical and emotional symptoms of both alcohol and opioid withdrawal syndromes.

PHYSICAL WITHDRAWAL

Alcohol and opioid withdrawal syndromes both involve autonomic dysregulation (Kosten and O’Connor, 2003). Shared symptoms include dysphoria, nausea, diaphoresis, tachycardia, and hypertension. That is, increased sympathetic tone and noradrenergic (NE) signaling. Alcohol withdrawal is more strongly characterized by pathologic glutamatergic signaling with seizure, delirium tremens, and death a dangerous possibility. Sympathetic hyperactivity is characteristic of opioid withdrawal resulting in pupillary dilatation, lacrimation, rhinorrhea, piloerection, yawning, sneezing, vomiting, and diarrhea. Toxic effects of ethanol on peripheral tissues, such as heart and liver, and the abundance of peripheral opioid receptors likely contribute to the severity of the peripherally-mediated effects of withdrawing from these substances (Holzer, 2009; An, Wang and Cederbaum, 2012; Piano, 2017).

Strikingly, alcohol and opioid withdrawal syndromes also share emotional symptoms: irritability, anxiety, and fear (Kosten and O’Connor, 2003). These emotional symptoms are likely influenced by neurovisceral afferents that relay information about peripheral network decompensation to central limbic nuclei (Fig. 2A) (Maniscalco and Rinaman, 2018). These interoceptive circuits include the well-studied gut-brain axis (Mayer, 2011), but also heart-brain, liver-brain, and other autonomically innervated tissues.

Similarities and differences in the withdrawal syndromes of alcohol and opioids are expected considering both substances stimulate the mesolimbic reward pathway through different mechanisms. Alcohol is a drug with more targets including major effects on the γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) ergic, glutamatergic, stress, and innate immune systems. (Vengeliene et al., 2009; Abrahao, Salinas and Lovinger, 2017). These primary mechanisms lead to the release of endogenous opioids that activate the mesolimbic reward pathway and alter amygdalar function (Söderpalm and Ericson, 2011). Opioids, conversely, are strong direct agonists of endogenous opioid receptors and act to stimulate the mesolimbic reward pathway directly, interfere with amygdalar function, and suppress NE neurons in the locus coeruleus (LC) (Rehni, Jaggi and Singh, 2013). We hypothesize, with others, that alteration of amygdalar activity in alcohol and opioid use constitutes the suppression of an antireward pathway, and that the conversely altered amygdalar activity in withdrawal syndromes activates this antireward pathway (Figs. 1–2) (Koob, 2009; Gardner, 2011; Gold et al., 2018).

The physical symptoms of acute alcohol withdrawal syndrome are mostly a manifestation of the effects alcohol has on sympathetic, GABAergic, and glutamatergic signaling. Alcohol exposure stimulates GABAA receptor (R) activity and suppresses N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA)Rs and sympathetic activity (Vengeliene et al., 2009; Abrahao, Salinas and Lovinger, 2017). In alcohol dependence, compensation to this exogenous stimulation leads to an allostatic state in which GABAergic activity is suppressed and glutamatergic and sympathetic activity is heightened. Abstinence exposes this maladapted network as overcompensated and the pathologic increase in overall nervous system activity can lead to seizures and death (Kosten and O’Connor, 2003).

The physical manifestations of opioid withdrawal syndrome are due primarily to NE system depression (Rehni, Jaggi and Singh, 2013). Activation of opioid receptors on NE neurons in the LC decreases intracellular cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) leading to decreased NE neurotransmission and depressed activity across the central nervous system. As tolerance develops, an allostatic network facilitating normal activity of NE neurons in the presence of opioids is achieved. Acute opioid abstinence exposes the LC neurons maladaptation and excessive NE neurotransmission manifests as sympathetic hyperactivity.

The initial symptoms of withdrawal from these substances, and most other substances of abuse, are quite similar (Kosten and O’Connor, 2003). Though alcohol and opioid withdrawal syndromes have different clinical treatments, the sympathetic suppressant clonidine has been used for both. Lofexidine is currently used in opioid withdrawal and like clonidine also regulates autonomic function by activating alpha-2 adrenergic receptors. Moreover, NE is known to stimulate tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) production in microglia (Spengler et al., 1994) inspiring these authors to speculate that part of lofexidine’s mechanism of action in opioid withdrawal may be anti-neuroinflammatory. More recently, external devices providing peripheral neuronal stimulation have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat opioid withdrawal with remarkable efficacy (Qureshi et al., 2020). This development adds further evidence to our hypothesis that peripheral neurovisceral feedback contributes substantially to opioid withdrawal syndrome. Benzodiazepine drugs (BZDs) are the primary treatment for alcohol withdrawal syndrome. These GABAAR agonists can prevent alcohol withdrawal seizures. BZDs are not clinically approved for opioid withdrawal syndrome, but BZD use, abuse, and dependence is very common in opioid dependence (Jones, Mogali and Comer, 2012). The observation that opioid and BZD polydrug abuse is common may be an indicator of the importance of anxiety, GABAAR agonism in the amygdala, and antireward in opioid withdrawal. Like opioids and alcohol, BZDs are anxiolytics, and opioid abusers may desire BZDs due to their suppression of antireward pathways, including the highly GABAergic amygdala (Tanaka et al., 2000; Roberto, Kirson and Khom, 2020). The primary approved treatment for opioid withdrawal is opioid maintenance therapy with methadone or buprenorphine which suggests novel therapies are much needed.

EMOTIONAL WITHDRAWAL

The negative reinforcement model of addiction postulates that following the establishment of an allostatic state, substance dependence maintained by drug-seeking and use is motivated by avoidance of both physical and emotional withdrawal symptoms (Koob and Le Moal, 2008). We argue below that these two symptomatologies, physical and emotional, may be linked—that the physical withdrawal symptoms influence the emotional states and vice versa producing a single syndrome. Additionally, we highlight the role of neuroinflammatory processes and glial-neuronal interactions in the observed negative emotion.

Irritability, anxiety, and fear are the hallmark emotional symptoms of alcohol and opioid withdrawal syndromes. This observation has led investigators to study the amygdala—the limbic hub in which negative emotion emerges (Shin and Liberzon, 2010; Jacobsen, Hutchinson and Mustafa, 2016; Abrahao, Salinas and Lovinger, 2017; Gold et al., 2018; Roberto, Kirson and Khom, 2020). The amygdala has been well-described for its role in threat detection, fear memory, and anxiety and panic (Halgren et al., 1978; LeDoux, 2003). The central nucleus of the amygdala (CeA) receives stress-peptide input (CRH and NE) in substance withdrawal, and when these stress-peptide receptors are blocked, drug use and withdrawal symptoms decline (Koob, 2009; Abrahao, Salinas and Lovinger, 2017; Gold et al., 2018; Roberto, Kirson and Khom, 2020). Similarly, drug-taking is suppressed when the basolateral amygdala (BLA), which provides input to the CeA, is lesioned (Everitt and Robbins, 2005). Siggins & Roberto have investigated the effects of alcohol and opioid exposure and withdrawal on the CeA extensively (2012; 2014; 2020). They convincingly demonstrate that GABAergic and immune signaling in the CeA contribute to dependence. For example, they showed CRH and ethanol increased GABA signaling in the CeA, and the effect was more potent in dependence (Roberto et al., 2010). Corder & colleagues have also demonstrated convincingly the importance of the amygdala in pain and the therapeutic effects of opioids in blunting such pain consistent with our antireward model (Fig. 1A) (Corder et al., 2019; Kimmey et al., 2020; McCall, Wojick and Corder, 2020). Other observations implicating the amygdala as an important region involved in substance dependence include the high comorbidity of alcohol use disorder and anxiety, the common combination of opioids and BZDs, and the observation that stress induces drug cravings in alcohol and opioid abstinence (Kushner, Abrams and Borchardt, 2000; Heilig and Koob, 2007; Jones, Mogali and Comer, 2012; Evans and Cahill, 2016; Abrahao, Salinas and Lovinger, 2017; Gold et al., 2018). Additionally, human fMRI studies show amygdala hyperactivity in opioid craving and suppression with methadone or alcohol administration (Langleben et al., 2008; Gorka et al., 2013; Murphy et al., 2018). Taken together, these studies point to the amygdala as an antireward center that motivates incentive-based substance use via suppression of negative emotion whilst concurrently motivating withdrawal-avoidance substance dependence via generation of negative emotion in withdrawal (Fig. 1).

Higher brain centers and the periphery have potent inputs to the amygdala (Fig. 2). Here, we focus on the periphery and specifically vagal afferents that synapse in the solitary nucleus (NTS). Strong bidirectional connections from the NTS to the CeA indicate a direct visceral-emotional connection i.e. visceral-emotional neuraxis (J. S. Schwaber et al., 1982). Indeed, about 80 percent of vagal nerve fibers are afferents, and the influence of these visceral afferents on mood, emotion, and behavior is impressive (Berthoud and Neuhuber, 2000; Maniscalco and Rinaman, 2018). Feedback from the gut will be discussed below in detail, but hepatic, cardiac, and other viscera have also been shown to modulate emotion (Thayer and Lane, 2000; D’Mello and Swain, 2011). Alcohol and opioids are also highly toxic to heart and liver. Alcohol is particularly toxic to liver causing the release of many inflammatory compounds including TNFα (An, Wang and Cederbaum, 2012). Thus, allostatic network decompensation in these organs in withdrawal likely induces neurovisceral feedback that contributes to pathologic signaling in the amygdala and results in negative emotion.

Inflammation in the amygdala may be the common pathology that induces severe negative emotion in both alcohol and opioid withdrawal (Figs. 1–2) (Crews, Zou and Qin, 2011; Coller and Hutchinson, 2012; Cooper et al., 2016; Ray et al., 2017). Cytokine microinjection directly into the amygdala induces anxiety-like behavior in mice, and this effect was shown to be dependent on astrocytes (Yang et al., 2016). In a similar experiment, repeated cytokine and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) treatments before an alcohol binge increased anxiety-like behavior in alcohol withdrawal (Breese et al., 2008). TNFα has been identified by multiple groups as central to this process. Microinjection of TNFα into the amygdala increased anxiety-like behavior in alcohol withdrawal (Knapp et al., 2011). Further, opioid withdrawal symptoms were augmented by the release of TNFα from astroglia in the periaqueductal gray: another potential antireward center (Hao et al., 2011). Vagal afferents have also been shown to directly activate astrocytes in the NTS (McDougal, Hermann and Rogers, 2011). More recently, a group has demonstrated that a subset of anti-inflammatory astrocytes that release interferon-γ are under the control of the gut-microbiome (Sanmarco et al., 2021). Taken together, these studies suggest astrocyte-derived cytokines, and TNFα in particular, are key drivers of negative emotion in withdrawal syndromes, and that gut-brain signaling influences their function.

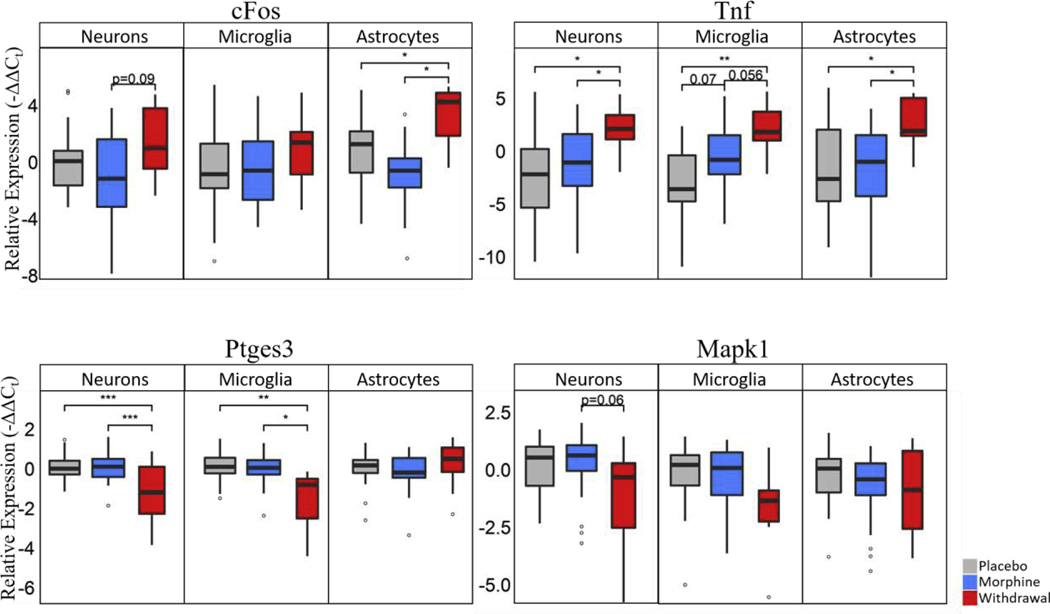

Studies out of our lab support these conclusions. We measured a panel of mRNAs using microfluidic reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) in ethanol dependent and withdrawn rats. We found inflammatory genes Ccl2, Nos2, Tnf, Tnfrsf1a and Cd74 upregulated and increased TNFα protein in the amygdala in withdrawal (Freeman, Brureau, et al., 2012). Additionally, we isolated single neurons, microglia, and astrocytes from the amygdala using laser capture microdissection and measured their transcription profile in morphine dependence and withdrawal (O’Sullivan et al. 2019; O’Sullivan et al. 2020). We found each cell type had a statistically significant increased level of Tnf expression in withdrawal with microglia showing a substantial upregulation of Tnf in morphine exposure as well (Fig. 3). Moreover, astrocytes showed the most profound changes in gene expression and expression correlation across the panel of genes measured further implicating their role in negative emotion in alcohol and opioid withdrawal syndromes (O’Sullivan et al., 2019). To our knowledge, we are the first, and of this writing only, group to publish that the gene expression of astrocytes is particularly perturbed in opioid withdrawal; However, we report with a high degree of confidence that other groups have replicated this finding in data presented at conferences or that is not yet published in animal and human models.

Figure 3. Boxplots of select genes demonstrating significant differential gene expression.

Statistics were calculated using nested ANOVA (*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.0001 n=4 animals for all treatments). See Fig. S3 for bar plots showing individual samples. Originally published in O’Sullivan et al. 2019.

Neuroinflammation in general, and TNFα in particular, causes neuronal hyperexcitability by increasing resting membrane potential (Schäfers and Sorkin, 2008). Additionally, acute alcohol exposure has been shown to increase neuronal activity in the CeA (Herman and Roberto, 2016). We propose that neuroinflammatory processes in the CeA in alcohol and opioid withdrawal contribute to neurons entering a hyperexcitable state. The amygdala has also been shown to receive stimulatory inputs of CRF, NE, glutamate, and glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) in withdrawal (Koob, 2009a). This scenario is a recipe for a hyperactive amygdala in both alcohol and opioid withdrawal. Amygdala hyperactivity generates panic, anxiety, and fear: emotional symptoms common to both alcohol and opioid withdrawal syndrome (Halgren et al., 1978; Kosten and O’Connor, 2003).

The anti-neuroinflammatory pharmaceutical ibudilast decreases opioid cravings and withdrawal symptoms, methamphetamine relapse, and is currently under investigation in alcohol withdrawal (Beardsley et al., 2010; Cooper et al., 2016; Ray et al., 2017). Ibudilast has been shown to inhibit phosphodiesterases and macrophage migration inhibotry factor (Cho et al., 2010). The effectiveness of ibudilast in clinical trials for substance dependence and other diseases involving neuroinflammatory processes such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and multiple sclerosis points to the significance of neuroinflammation in neurological and psychiatric disease. Ibudilast’s efficacy in these clinical trials also suggests targeting neuroinflammation may be a fruitful method for modifying behavior. This emphasizes the importance of understanding the underlying pathophysiology of substance dependence so that proper treatments can be developed. Below, we propose an additional contributor to this process: gut microbiota.

GUT-BRAIN AXIS in WITHDRAWAL and ADDICTION

Recent study of the gut-brain axis has established the link between peripheral disturbances (i.e. network decompensation) and emotional sequelae (Fig. 2) (Mayer, 2011; Bonaz, Bazin and Pellissier, 2018; Maniscalco and Rinaman, 2018). The involvement of this axis and other peripheral to central feedback circuits have not been thoroughly studied as contributors to negative emotion in alcohol or opioid withdrawal, though preliminary studies and explanations are compelling (Leclercq et al., 2014; de Timary et al., 2015; Skosnik and Cortes-Briones, 2016; Meckel and Kiraly, 2019; Everett et al., 2021). Our hypothesis is that interoceptive feedback (i.e. vagal afferents) may substantially influence the negative physical and emotional symptoms of alcohol and opioid withdrawal syndromes. This hypothesis is based on the known effects of these substances on the periphery, their addiction potential, and the observed similarity in negative emotion evoked in their withdrawal syndromes. Below we explore this possibility as a systems-wide antireward circuit and implicate gut microbiota as a potential contributor. We do this in a context that recognizes vagal efferents also contribute to gut dysbiosis generating an “inflammatory reflex” (Bonaz, Bazin and Pellissier, 2018). Lastly, we recognize recent data showing gut-brain axis involvement in the mesolimbic DA reward pathway and consider alternative hypotheses (Han et al., 2018).

The effects of alcohol on gastrointestinal permeability have been well-studied (de Timary et al., 2015; Gorky and Schwaber, 2016). Increased gut permeability in alcohol dependence leads to endotoxinemia that stimulates liver macrophages (Kupffer cells) to release a host of cytokines, most notably TNFα. Alcohol exposure has also been shown to induce growth of pro-inflammatory bacterial species in the gut while reducing commensal bacteria (Gorky and Schwaber, 2016). Taken together, these studies suggest chronic alcohol use increases peripheral inflammation. Paradoxically, an acute ethanol binge seems to decrease innate immunity (Szabo and Mandrekar, 2009). The relationship between alcohol and the immune system is complex, but alcohol has been shown to alter gut microbiota composition, gut permeability, and immune function leading to increased dependence. This was convincingly demonstrated by Leclercq et al., 2014 who found that in a subset of recovering alcohol-dependent patients, gut dysbiosis correlated with intestinal permeability, negative emotion, and alcohol craving. Gut dysbiosis, leaky gut, and peripheral inflammation are also linked to impaired blood brain barrier integrity and function which can lead to neuroinflammation (Fiorentino et al., 2016). Meckel & Kiraly provide an encyclopedic table of experiments that have measured the specific changes the gut microbiome experiences in response to alcohol (2019). Given these studies, we postulate that the effects of alcohol on the gut contribute to the negative emotions experienced in alcohol withdrawal that drive dependence via negative reinforcement. More specifically, we speculate that gut microfloral changes induced by alcohol, and opioids, alter interceptive vagal signaling resulting in limbic overactivation and autonomic dysregulation (Fig. 2) (Mayer, 2011). We go even further by recognizing diet alone can activate this antireward pathway or simply negative emotion in a top-down inflammatory reflex (Bonaz, Bazin and Pellissier, 2018).

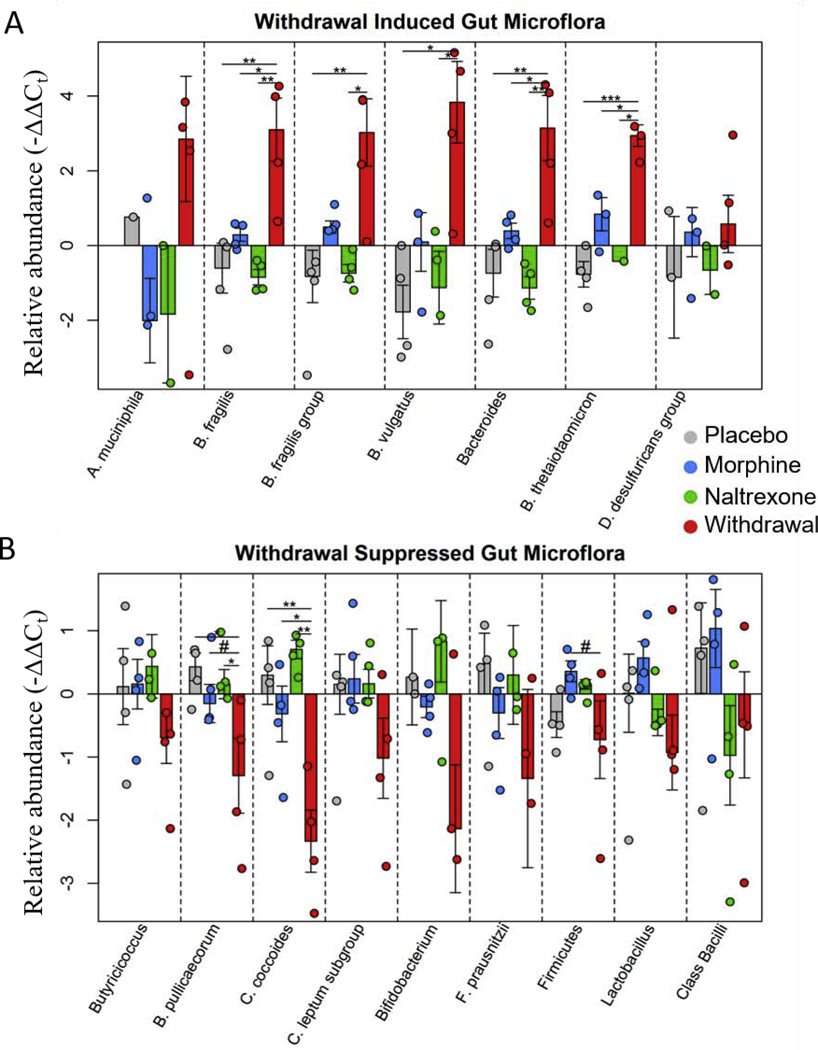

The gut microbiome is perturbed by opioid use and withdrawal (Fig. 4) (Wang et al., 2018; O’Sullivan et al., 2019). This is not surprising considering the large number of opioid receptors in the gut and the essentially universal side-effect of constipation (Holzer, 2009). The microbiome alterations are indeed striking. Species associated with inflammation such as E. faecalis and B. vulgatus increase in opioid withdrawal while commensal beneficial bacteria including Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus, and F. prausnitzii species decrease (O’Sullivan et al., 2019). Moreover, the two major phyla that comprise mammalian gut microflora, Firmicutes and Bacteroides, were found to shift in opposite directions lowering the Firmicutes to Bacteroides ratio in opioid withdrawal. A decreased Firmicutes to Bacteroides ratio is a consistent marker of inflammation and dysbiosis (Tamboli et al., 2004; Collins, 2014; Sampson et al., 2016; Rowin et al., 2017). Additionally, increased TNFα transcription in CeA neurons, microglia, and astrocytes suggested a connection between gut microbiota dysbiosis and limbic neuroinflammation (O’Sullivan et al., 2019). Opioids have also been shown to increase gut permeability leading to bacteria translocation (Wang et al., 2018), and act as agonists for inflammatory toll-like 4 receptors (TLR4) (Wang et al., 2012).

Figure 4. Relative abundance of gut microflora from rat cohort 2.

Barplots display relative abundance of bacterial species (-ΔΔCt values). #p<0.1, *p<0.05, **p<0.008, ***p=0.0009; two-way ANOVA n=4 animals for each treatment. Originally published in O’Sullivan et al. 2019.

Perhaps even more fascinating is the effect alcohol, opioids, and the gut microbiome have on food preferences and diet. Recovery from alcohol dependence increases the inclination for sweets and often results in weight gain (Krahn et al., 2006). Similarly, opioid dependence commonly increases cravings for processed foods with a high glycemic index (Mysels and Sullivan, 2010; Neale et al., 2012). There is even evidence that an inclination for sweet foods—high fructose corn syrup in particular—may increase the risk for alcohol and opioid dependence (Ayoub et al., 2020). Taken together with recent findings that gut microbiota influence food preference (Leitão-Gonçalves et al., 2017), these studies suggest that dysbiosis incited by alcohol and opioid dependence may contribute to detrimental dietary change. Moreover, these findings are consistent with the hypothesis that an inflammatory mix of gut microflora may predispose to alcohol or opioid dependence or other psychiatric illness (Mayer, 2011). Considering diet has more influence on gut microbiome composition than any other environmental factor (Scott et al., 2013), eating processed foods following alcohol and opioid detoxification may encourage a pro-inflammatory gut microbiome. This scenario would lead to low grade peripheral and central inflammation, which may increase substance cravings (Leclercq et al., 2014; de Timary et al., 2015). We postulate this may be due to antireward circuit activation motivating incentive-based use to blunt negative emotion (Fig. 1A).

The field of nutrition in recovery from alcohol and opioid dependence is a complex and understudied topic. It is explored in detail in elsewhere (Wiss, 2018; Chavez and Rigg, 2020). What we speculate on here, based on these data, is that antireward pathway activation by neurovisceral feedback may stem from gut dysbiosis. That is, gut dysbiosis, whether originating from substance use, processed foods, or top-down negative emotion, likely increases vulnerability to substance dependence or relapse because interoceptive and blood-borne signaling activate antireward centers through, in part, inflammatory processes. If this is true, processed food intake should correlate with substance dependence. Socioeconomic, environmental, genetic, and metabolic variables confound these real-world analyses, but obesity and highly palatable processed foods are correlated with mental illness including substance dependence (VanBuskirk and Potenza, 2010). However, alternative hypotheses also explain this observation. Highly palatable processed foods stimulate the same mesolimbic DA reward pathway that alcohol, opioids, and other substances of abuse stimulate. It may simply be the case that those vulnerable to motivated behavior by DA reward for whatever reason will find processed food and substances of abuse addicting.

The connection between DA reward pathways, food intake, and substance dependence is well-studied (Volkow, Wise and Baler, 2017). Gut microbiota and their relationship to DA signaling has mostly been studied in the context of Parkinson’s disease (PD) (Parashar and Udayabanu, 2017) but also schizophrenia (Severance, Yolken and Eaton, 2016). Antibiotics, probiotics, fecal transplant, germ-free animals, and gut infection have been shown to affect DA signaling in PD and PD models suggesting a connection between gut microbiota and DA signaling. We also note that an important ligand in anxiogenic signaling from the NTS to the amygdala, GLP-1, also has an endocrine role in food intake and is linked to drug addiction (Fig. 2B) (Hayes and Schmidt, 2016). More recently, Han et al. 2018 used optogenetics in vagal afferents to show that vagal input increases DA release by substantia nigra neurons. They claim their “findings establish the vagal gut-to-brain axis as an integral component of the neuronal reward pathway.” The influence that gut microbiota have on vagal signaling implicate gut microflora in this phenomenon (Mayer, 2011; Bonaz, Bazin and Pellissier, 2018).

As mentioned above, the absence of signaling in the DA mesolimbic reward pathway is a likely contributor to the negative emotion experienced in alcohol and opioid withdrawal (Fig. 1B). Though parsimonious, this mesolimbic centric explanation does not fully account for the addiction potential, stress, negative emotion, neuroinflammation, and autonomic dysregulation observed in alcohol and opioid withdrawal (Pierce and Kumaresan, 2006; Koob and Le Moal, 2008; Wise and Koob, 2014). Additionally, the well-studied human negativity bias, and the disproportionate influence of negative emotion on motivated behavior, further implicates antireward circuits as a major contributor to substance use and dependence (Vaish, Grossmann and Woodward, 2008). Given the ubiquitous influence of gut microbiota on health and the general complexity of biology, it is likely that gut dysbiosis in substance withdrawal contributes to both the inhibition of reward signaling and stimulation of antireward signaling (Fig. 1B) (Wise and Koob, 2014).

The time course of alcohol and opioid withdrawal syndromes provides further clues as to the role of peripheral inflammation, neuroinflammation, and vagal input. The negative emotional symptoms of alcohol withdrawal emerge within 8 hours of abstinence in humans (Kosten and O’Connor, 2003). This time course suggests that peripheral inflammation precipitated by alcohol withdrawal does not directly cause astrocyte and microglial activation in the antireward pathways of the amygdala. That is, the negative emotions emerge too quickly for the peripheral immune system to contribute. However, vagal afferents relaying the state of the periphery to central nuclei, most notably the NTS, can respond immediately and influence NTS astrocytes (McDougal, Hermann and Rogers, 2011). We find activation of immune gene networks in rat amygdala and NTS at 4 and 8 hour time points in alcohol withdrawal (Freeman, Brureau, et al., 2012; Freeman, Staehle, et al., 2012; Freeman et al., 2013). Additionally, substantial gut dysbiosis was observed 24 hours following naltrexone-precipitated opioid withdrawal with correlated neuroinflammation in the amygdala (Fig. 4) (O’Sullivan et al., 2019). These relatively fast alterations in central inflammation with correlated gut dysbiosis suggest vagal involvement. However, the gut microbiome has been shown to control astrocyte interferon-γ release via peripheral immune cells (Sanmarco et al., 2021). To our knowledge, gut dysbiosis in alcohol withdrawal has only been measured 3 weeks following detoxification (Leclercq et al., 2014).

Additionally, peak withdrawal symptoms in humans for both ethanol and heroin are observed at ~72 hours following substance abstinence (Kosten and O’Connor, 2003). The peripheral innate immune system can respond within minutes of immunological challenge and is fully active 48–72 hours following challenge. The convergence in the time course of peak withdrawal symptoms for ethanol, heroin and fentanyl and peripheral immune response may indicate a relationship between peripheral allostatic decompensation, inflammatory signaling, and negative emotion in alcohol and opioid withdrawal syndromes. Substance pharmacokinetics have strong influence on peak withdrawal symptoms as well. Yet, the opioids of choice for opioid-dependent patients behave on this time course suggesting the time course of the withdrawal syndrome and immune activation may contribute to the addictive properties. This is highly speculative, and we only mention it to be complete.

The role of the NTS in this antireward pathway is far more well-defined. This region of the medulla receives the most vagal input and is a key limbic structure that has strong bidirectional connections to the CeA (Schwaber et al. 1982) (Fig. 2). More specifically, the vagus nerve forms synapses with preproglucagon neurons in the NTS which signal to GLP-1R containing neurons in various brain regions including the paraventricular nucleus, the ventrolateral medulla, and central nucleus of the amygdala (Fig. 2) (Holt and Trapp, 2016). These anxiogenic inputs to limbic, HPA axis, and sympathetic structures result in emotional, stress-endocrine, and sympathetic responses; all of which characterize alcohol and opioid withdrawal. Interestingly, these GLP-1 inputs strongly regulate food intake as well, so it is not surprising that gut microbiota would strongly influence this brain region (Mayer, 2011; Scott et al., 2013; Holt and Trapp, 2016; Maniscalco and Rinaman, 2018). We note the influence of alcohol on other gut peptides critical to this process elsewhere (Gorky and Schwaber, 2016). A recent study demonstrating the influence of oxytocin on vagal afferents and methamphetamine self-administration deserves mention (Everett et al., 2021). Vagotomy blunted the effect of oxytocin in mitigating use.

The NTS receives information via vagal afferents from many internal organs in addition to the gut. Cardiovascular and blood pressure-related inputs from the heart and blood vessels are of particular interest because these systems experience network decompensation in alcohol withdrawal in particular (Piano, 2017). The established connection between stress, anxiety, Takotsubo cardiomyopathy, and afferent and efferent vagal signaling points to the power of the vagus in converting emotional distress to physical dysfunction or the reverse in a myocardial infarction (Hocaoglu, H.Yeloglu and Polat, 2011). Thus, NTS outputs are capable of generating severe physical and emotional symptoms and our group has observed prominent neuroinflammation in this region in alcohol withdrawal (Freeman, Brureau, et al., 2012; Freeman, Staehle, et al., 2012). This is not surprising given vagal afferents directly activate NTS astrocytes (McDougal, Hermann and Rogers, 2011). Taken together, the influence of gut microbiota on vagal signaling and vice versa implicate the gut-NTS-amygdala connection i.e visceral-emotional neuraxis (Fig. 2) in not just alcohol and opioid withdrawal syndromes but also mental and physical health generally.

If our hypothesis is true, anti-neuroinflammatory treatments, whole-food anti-inflammatory diets, and probiotics should be effective treatments for alcohol and opioid withdrawal syndromes and the prevention of relapse. Human trials using the macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) inhibitor ibudilast have been promising in decreasing opioid withdrawal symptoms and methamphetamine relapse (Beardsley et al., 2010; Cooper et al., 2016). Ibudilast is currently being tested for effectiveness in alcohol withdrawal and relapse (Ray et al., 2017). To date, few studies have focused on diet as a primary component of alcohol or opioid dependence recovery (Biery, Williford and McMullen, 1991). There is a literature on nutrition for alcohol or opioid recovery (Jeynes and Gibson, 2017; Wiss, 2018; Chavez and Rigg, 2020). Its main focus is on malnutrition in substance dependence and nutrition education in recovery, as opposed to the role of an anti-inflammatory prebiotic diet in shifting the gut microbiome to positively influence emotional circuits and ultimately behavior. However, clinicians have noticed that whole foods aid in substance recovery while high-sugar foods increase relapse susceptibility (Holford, Miller and Braly, 2008).

The above literature suggests that the effects of alcohol and opioid dependence on peripheral systems contributes to physical and emotional withdrawal symptoms. We go further by suggesting that common inflammatory mechanisms, possibly originating from gut microbiome dysbiosis, play a major role in both alcohol and opioid withdrawal syndromes. We are not the first to speculate that gut dysbiosis contributes to substance abuse via negative reinforcement (de Timary et al., 2015; Skosnik and Cortes-Briones, 2016; Meckel and Kiraly, 2019). Gut microflora influence the visceral-emotional neuraxis directly and play a major role in inflammatory processes and behavior (Mayer, 2011; Scott et al., 2013; Bonaz, Bazin and Pellissier, 2018). This interoceptive circuit and neuroinflammation are both implicated in the negative physical and emotional symptoms of alcohol and opioid withdrawal syndromes suggesting gut microbiota may be an important component of this phenomenon. We can claim with confidence that gut dysbiosis is, at least, an epiphenomenon in opioid and alcohol dependence and withdrawal.

CONCLUSION

Alcohol and opioid dependence pose major challenges to American society. Understanding the reward pathways that govern compulsive use has resulted in treatment targets for these epidemics though efficacy is limited. Antireward pathways, including the visceral-emotional neuraxis (Figs. 1–2), are less studied with fewer therapies available. The similarity in the severity and time course of the withdrawal syndromes of alcohol and opioids along with BZD use and fMRI imaging suggests that some common mechanisms drive the negative physical and emotional side effects experienced in both withdrawal syndromes. Inflammatory glial-neuronal signaling, particularly in the amygdala and NTS, may be important similarities that explain the efficacy of the anti-neuroinflammatory ibudilast and its therapeutic benefits in withdrawal from multiple substances. Lastly, we suggest that dysbiotic gut microbiota contribute to inflammation and pathologic gut-brain signaling in withdrawal. Treatments that target these common withdrawal symptoms may be beneficial in blunting negative reinforcement across multiple substances of abuse and support relapse prevention. Further, understanding this antireward pathway may lead to treatments for general anxiety and depression that could combat other so-called deaths of despair.

Highlights.

Alcohol and opioid withdrawal syndromes share physical and emotional symptoms

Neuroinflammation in the visceral-emotional neuraxis likely contributes to this observation

Vagal neurovisceral feedback influenced by gut dysbiosis contributes to this inflammation

This process constitutes an antireward pathway and treatment target for addiction

Acknowledgments

FUNDING

The work presented here is funded through NIH HLB U01 HL133360 awarded to JS and NIDA R21 DA036372 awarded to JS.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abrahao KP, Salinas AG and Lovinger DM (2017) ‘Alcohol and the Brain: Neuronal Molecular Targets, Synapses, and Circuits’, Neuron. Cell Press, pp. 1223–1238. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.10.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An L, Wang X. and Cederbaum AI (2012) ‘Cytokines in alcoholic liver disease’, Archives of Toxicology, 86(9), pp. 1337–1348. doi: 10.1007/s00204-012-0814-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayoub SM et al. (2020) ‘Effects of high fructose corn syrup on ethanol self-administration in rats’, Alcohol. Elsevier BV doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2020.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajo M. et al. (2014) ‘Acute morphine alters GABAergic transmission in the central amygdala during naloxone-precipitated morphine withdrawal: Role of cyclic AMP’, Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience. Frontiers Research Foundation, 8(JUNE). doi: 10.3389/fnint.2014.00045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beardsley PM et al. (2010) ‘The glial cell modulator and phosphodiesterase inhibitor, AV411 (ibudilast), attenuates prime- and stress-induced methamphetamine relapse’, European Journal of Pharmacology, 637(1–3), pp. 102–108. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2010.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berthoud H-R and Neuhuber WL (2000) ‘Functional and chemical anatomy of the afferent vagal system’, Autonomic Neuroscience. Elsevier, 85(1–3), pp. 1–17. doi: 10.1016/S1566-0702(00)00215-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biery JR, Williford JH and McMullen EA (1991) ‘Alcohol craving in rehabilitation: assessment of nutrition therapy.’, Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 91(4), pp. 463–6. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2016494 (Accessed: 4 February 2019). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonaz B, Bazin T. and Pellissier S. (2018) ‘The vagus nerve at the interface of the microbiota-gut-brain axis’, Frontiers in Neuroscience. Frontiers Media S.A, p. 49. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2018.00049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breese GR et al. (2008) ‘Repeated lipopolysaccharide (LPS) or cytokine treatments sensitize ethanol withdrawal-induced anxiety-like behavior.’, Neuropsychopharmacology : official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. NIH Public Access, 33(4), pp. 867–76. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavez MN and Rigg KK (2020) ‘Nutritional Implications of Opioid Use Disorder: A Guide for Drug Treatment Providers’, Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. Educational Publishing Foundation. doi: 10.1037/adb0000575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho Y. et al. (2010) ‘Allosteric inhibition of macrophage migration inhibitory factor revealed by ibudilast’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. National Academy of Sciences, 107(25), pp. 11313–11318. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002716107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coller JK and Hutchinson MR (2012) ‘Implications of central immune signaling caused by drugs of abuse: Mechanisms, mediators and new therapeutic approaches for prediction and treatment of drug dependence’, Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 134(2), pp. 219–245. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2012.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins SM (2014) ‘A role for the gut microbiota in IBS’, Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 11(8), pp. 497–505. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2014.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ZD et al. (2016) ‘The effects of ibudilast, a glial activation inhibitor, on opioid withdrawal symptoms in opioid-dependent volunteers’, Addiction Biology, 21(4), pp. 895–903. doi: 10.1111/adb.12261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corder G. et al. (2019) ‘An amygdalar neural ensemble that encodes the unpleasantness of pain’, Science. American Association for the Advancement of Science, 363(6424), pp. 276–281. doi: 10.1126/science.aap8586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crews FT, Zou J. and Qin L. (2011) ‘Induction of innate immune genes in brain create the neurobiology of addiction’, Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. Academic Press, 25, pp. S4–S12. doi: 10.1016/J.BBI.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Mello C. and Swain MG (2011) ‘Liver-brain inflammation axis’, American Journal of Physiology-Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology. American Physiological Society; Bethesda, MD, 301(5), pp. G749–G761. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00184.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans CJ and Cahill CM (2016) ‘Neurobiology of opioid dependence in creating addiction vulnerability.’, F1000Research. Faculty of 1000 Ltd, 5. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.8369.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everett NA et al. (2021) ‘The vagus nerve mediates the suppressing effects of peripherally administered oxytocin on methamphetamine self-administration and seeking in rats’, Neuropsychopharmacology. Springer Nature, 46(2), pp. 297–304. doi: 10.1038/s41386-020-0719-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everitt BJ and Robbins TW (2005) ‘Neural systems of reinforcement for drug addiction: from actions to habits to compulsion’, Nature Neuroscience. Nature Publishing Group, 8(11), pp. 1481–1489. doi: 10.1038/nn1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiorentino M. et al. (2016) ‘Blood–brain barrier and intestinal epithelial barrier alterations in autism spectrum disorders’, Molecular Autism. BioMed Central, 7(1), p. 49. doi: 10.1186/s13229-016-0110-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman K, Staehle MM, et al. (2012) ‘Rapid temporal changes in the expression of a set of neuromodulatory genes during alcohol withdrawal in the dorsal vagal complex: molecular evidence of homeostatic disturbance.’, Alcoholism, clinical and experimental research. England, 36(10), pp. 1688–1700. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2012.01791.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman K, Brureau A, et al. (2012) ‘Temporal changes in innate immune signals in a rat model of alcohol withdrawal in emotional and cardiorespiratory homeostatic nuclei.’, Journal of neuroinflammation. BioMed Central, 9, p. 97. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-9-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman K. et al. (2013) ‘Coordinated dynamic gene expression changes in the central nucleus of the amygdala during alcohol withdrawal.’, Alcoholism, clinical and experimental research. NIH Public Access, 37 Suppl 1(0 1), pp. E88–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2012.01910.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner EL (2011) ‘Addiction and Brain Reward and Antireward Pathways’, in Chronic Pain and Addiction. Basel: KARGER, pp. 22–60. doi: 10.1159/000324065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold MS et al. (2018) ‘Molecular role of dopamine in anhedonia linked to reward deficiency syndrome (RDS) and anti-reward systems’, Frontiers in Bioscience - Scholar. Frontiers in Bioscience, 10(2), pp. 309–325. doi: 10.2741/s518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorka SM et al. (2013) ‘Alcohol attenuates amygdala-frontal connectivity during processing social signals in heavy social drinkers: A preliminary pharmaco-fMRI study’, Psychopharmacology. Springer, 229(1), pp. 141–154. doi: 10.1007/s00213-013-3090-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorky J. and Schwaber J. (2016) ‘The role of the gut–brain axis in alcohol use disorders’, Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry. Elsevier, 65, pp. 234–241. doi: 10.1016/J.PNPBP.2015.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halgren E. et al. (1978) ‘Mental phenomena evoked by electrical stimulation of the human hippocampal formation and amygdala.’, Brain : a journal of neurology, 101(1), pp. 83–117. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/638728 (Accessed: 11 April 2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han W. et al. (2018) ‘A Neural Circuit for Gut-Induced Reward’, Cell. Cell Press, 175(3), pp. 665–678.e23. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.08.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao S. et al. (2011) ‘The Role of TNFα in the Periaqueductal Gray During Naloxone-Precipitated Morphine Withdrawal in Rats’, Neuropsychopharmacology, 36(3), pp. 664–676. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes MR and Schmidt HD (2016) ‘GLP-1 influences food and drug reward.’, Current opinion in behavioral sciences. NIH Public Access, 9, pp. 66–70. doi: 10.1016/j.cobeha.2016.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heilig M. and Koob GF (2007) ‘A key role for corticotropin-releasing factor in alcohol dependence’, Trends in Neurosciences. Elsevier Current Trends, 30(8), pp. 399–406. doi: 10.1016/J.TINS.2007.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman MA and Roberto M. (2016) ‘Cell-type-specific tonic GABA signaling in the rat central amygdala is selectively altered by acute and chronic ethanol’, Addiction Biology. Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 21(1), pp. 72–86. doi: 10.1111/adb.12181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hocaoglu C, Yeloglu HC and Polat (2011) ‘Cardiac Disease and Anxiety Disorders’, in Szirmai A. (ed.) Anxiety and Related Disorders. IntechOpen, pp. 139–150. doi: 10.5772/INTECHOPEN.84024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holford P, Miller D. and Braly J. (2008) How to quit without feeling s**t : the fast, effective way to stop cravings without drugs. Piatkus. [Google Scholar]

- Holt MK and Trapp S. (2016) ‘The physiological role of the brain GLP-1 system in stress.’, Cogent biology. Taylor & Francis, 2(1), p. 1229086. doi: 10.1080/23312025.2016.1229086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holzer P. (2009) ‘Opioid receptors in the gastrointestinal tract’, Regulatory Peptides. Elsevier, 155(1–3), pp. 11–17. doi: 10.1016/J.REGPEP.2009.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoots BE et al. (no date) 2018 ANNUAL SURVEILLANCE REPORT OF DRUG-RELATED RISKS AND OUTCOMES UNITED STATES. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/ (Accessed: 12 December 2018).

- Jacobsen JHW, Hutchinson MR and Mustafa S. (2016) ‘Drug addiction: targeting dynamic neuroimmune receptor interactions as a potential therapeutic strategy’, Current Opinion in Pharmacology, 26, pp. 131–137. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2015.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jannetto PJ (2021) ‘The North American Opioid Epidemic’, Therapeutic Drug Monitoring. Ovid Technologies (Wolters Kluwer Health), 43(1), pp. 1–5. doi: 10.1097/ftd.0000000000000817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeynes KD and Gibson EL (2017) ‘The importance of nutrition in aiding recovery from substance use disorders: A review’, Drug and Alcohol Dependence. Elsevier, 179, pp. 229–239. doi: 10.1016/J.DRUGALCDEP.2017.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones JD, Mogali S. and Comer SD (2012) ‘Polydrug abuse: A review of opioid and benzodiazepine combination use’, Drug and Alcohol Dependence. Elsevier, 125(1–2), pp. 8–18. doi: 10.1016/J.DRUGALCDEP.2012.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimmey BA et al. (2020) ‘Engaging endogenous opioid circuits in pain affective processes’, Journal of Neuroscience Research. John Wiley and Sons Inc, p. jnr.24762. doi: 10.1002/jnr.24762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knapp DJ et al. (2011) ‘Cytokine involvement in stress may depend on corticotrophin releasing factor to sensitize ethanol withdrawal anxiety’, Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. Academic Press, 25, pp. S146–S154. doi: 10.1016/J.BBI.2011.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF (2009) ‘Brain stress systems in the amygdala and addiction.’, Brain research. NIH Public Access, 1293, pp. 61–75. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.03.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF and Le Moal M. (2001) ‘Drug Addiction, Dysregulation of Reward, and Allostasis’, Neuropsychopharmacology. Nature Publishing Group, 24(2), pp. 97–129. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(00)00195-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF and Le Moal M. (2008) ‘Addiction and the Brain Antireward System’, Annual Review of Psychology, 59(1), pp. 29–53. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.59.103006.093548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosten TR and O’Connor PG (2003) ‘Management of Drug and Alcohol Withdrawal’, New England Journal of Medicine. Massachusetts Medical Society, 348(18), pp. 1786–1795. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra020617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krahn D. et al. (2006) ‘Sweet intake, sweet-liking, urges to eat, and weight change: Relationship to alcohol dependence and abstinence’, Addictive Behaviors, 31(4), pp. 622–631. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.05.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushner MG, Abrams K. and Borchardt C. (2000) ‘The relationship between anxiety disorders and alcohol use disorders: A review of major perspectives and findings’, Clinical Psychology Review. Pergamon, 20(2), pp. 149–171. doi: 10.1016/S0272-7358(99)00027-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langleben DD et al. (2008) ‘Acute effect of methadone maintenance dose on brain fMRI response to heroin-related cues’, American Journal of Psychiatry. American Psychiatric Association, 165(3), pp. 390–394. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07010070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leclercq S. et al. (2014) ‘Intestinal permeability, gut-bacterial dysbiosis, and behavioral markers of alcohol-dependence severity.’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. National Academy of Sciences, 111(42), pp. E4485–93. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1415174111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeDoux J. (2003) ‘The emotional brain, fear, and the amygdala.’, Cellular and molecular neurobiology, 23(4–5), pp. 727–38. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14514027 (Accessed: 11 April 2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leitão-Gonçalves R. et al. (2017) ‘Commensal bacteria and essential amino acids control food choice behavior and reproduction’, PLOS Biology. Edited by Vosshall L. Public Library of Science, 15(4), p. e2000862. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.2000862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maniscalco JW and Rinaman L. (2018) ‘Vagal Interoceptive Modulation of Motivated Behavior’, Physiology. American Physiological Society Bethesda, MD, 33(2), pp. 151–167. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00036.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer E. a (2011) ‘Gut feelings: the emerging biology of gut-brain communication.’, Nature reviews. Neuroscience. Nature Publishing Group, 12(8), pp. 453–66. doi: 10.1038/nrn3071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCall NM, Wojick JA and Corder G. (2020) ‘Anesthesia analgesia in the amygdala’, Nature Neuroscience. Nature Research, 23(7), pp. 783–785. doi: 10.1038/s41593-020-0645-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDougal DH, Hermann GE and Rogers RC (2011) ‘Vagal Afferent Stimulation Activates Astrocytes in the Nucleus of the Solitary Tract Via AMPA Receptors: Evidence of an Atypical Neural-Glial Interaction in the Brainstem’, Journal of Neuroscience. Society for Neuroscience, 31(39), pp. 14037–14045. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2855-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meckel KR and Kiraly DD (2019) ‘A potential role for the gut microbiome in substance use disorders’, Psychopharmacology. Springer Verlag, pp. 1513–1530. doi: 10.1007/s00213-019-05232-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreira FA and Dalley JW (2015) ‘Dopamine receptor partial agonists and addiction’, European Journal of Pharmacology, 752, pp. 112–115. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2015.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy A. et al. (2018) ‘Time-dependent neuronal changes associated with craving in opioid dependence: an fMRI study’, Addiction Biology. Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 23(5), pp. 1168–1178. doi: 10.1111/adb.12554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mysels DJ and Sullivan MA (2010) ‘The relationship between opioid and sugar intake: review of evidence and clinical applications.’, Journal of opioid management. NIH Public Access, 6(6), pp. 445–52. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21269006 (Accessed: 29 January 2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neale J. et al. (2012) ‘Eating patterns among heroin users: a qualitative study with implications for nutritional interventions’, Addiction, 107(3), pp. 635–641. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03660.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Sullivan SJ et al. (2019) ‘Single-Cell Glia and Neuron Gene Expression in the Central Amygdala in Opioid Withdrawal Suggests Inflammation With Correlated Gut Dysbiosis’, Frontiers in Neuroscience. Frontiers, 13, p. 665. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2019.00665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Sullivan SJ et al. (2020) ‘Combining laser capture microdissection and microfluidic qpcr to analyze transcriptional profiles of single cells: A systems biology approach to opioid dependence’, Journal of Visualized Experiments. Journal of Visualized Experiments, 2020(157), p. e60612. doi: 10.3791/60612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Sullivan SJ (2020) The Effect of Alcohol and Opioid Withdrawal on Single-Cell Glia and Neuronal Gene Expression in the Visceral Emotional Neuraxis. Thomas Jefferson University. [Google Scholar]

- Parashar A. and Udayabanu M. (2017) ‘Gut microbiota: Implications in Parkinson’s disease’, Parkinsonism & Related Disorders. Elsevier, 38, pp. 1–7. doi: 10.1016/J.PARKRELDIS.2017.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters S. et al. (2017) ‘Amygdala-orbitofrontal connectivity predicts alcohol use two years later: a longitudinal neuroimaging study on alcohol use in adolescence’, Developmental Science. Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 20(4), p. e12448. doi: 10.1111/desc.12448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piano MR (2017) ‘Alcohol’s Effects on the Cardiovascular System’, Alcohol research : current reviews. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, pp. 219–241. Available at: https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/ (Accessed: 9 July 2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce RC and Kumaresan V. (2006) ‘The mesolimbic dopamine system: The final common pathway for the reinforcing effect of drugs of abuse?’, Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. Pergamon, 30(2), pp. 215–238. doi: 10.1016/J.NEUBIOREV.2005.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qureshi IS et al. (2020) ‘Auricular neural stimulation as a new non-invasive treatment for opioid detoxification’, Bioelectronic Medicine. Springer Science and Business Media LLC, 6(1). doi: 10.1186/s42234-020-00044-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray LA et al. (2017) ‘Development of the Neuroimmune Modulator Ibudilast for the Treatment of Alcoholism: A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Human Laboratory Trial’, Neuropsychopharmacology, 42(9), pp. 1776–1788. doi: 10.1038/npp.2017.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehni AK, Jaggi AS and Singh N. (2013) ‘Opioid withdrawal syndrome: emerging concepts and novel therapeutic targets.’, CNS & neurological disorders drug targets, 12(1), pp. 112–25. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23244430 (Accessed: 14 December 2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberto M. et al. (2010) ‘Corticotropin Releasing Factor–Induced Amygdala Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid Release Plays a Key Role in Alcohol Dependence’, Biological Psychiatry, 67(9), pp. 831–839. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberto M, Gilpin NW and Siggins GR (2012) ‘The central amygdala and alcohol: role of γ-aminobutyric acid, glutamate, and neuropeptides.’, Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in medicine. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, 2(12), p. a012195. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a012195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberto M, Kirson D. and Khom S. (2020) ‘The Role of the Central Amygdala in Alcohol Dependence’, Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, p. a039339. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a039339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowin J. et al. (2017) ‘Gut inflammation and dysbiosis in human motor neuron disease.’, Physiological reports. Wiley-Blackwell, 5(18). doi: 10.14814/phy2.13443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson TR et al. (2016) ‘Gut Microbiota Regulate Motor Deficits and Neuroinflammation in a Model of Parkinson’s Disease’, Cell, 167(6), pp. 1469–1480.e12. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanmarco LM et al. (2021) ‘Gut-licensed IFNγ+ NK cells drive LAMP1+TRAIL+ anti-inflammatory astrocytes’, Nature. Nature Research. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-03116-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schäfers M. and Sorkin L. (2008) ‘Effect of cytokines on neuronal excitability’, Neuroscience Letters. Elsevier, 437(3), pp. 188–193. doi: 10.1016/J.NEULET.2008.03.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwaber J. et al. (1982) ‘Amygdaloid and basal forebrain direct connections with the nucleus of the solitary tract and the dorsal motor nucleus’, Journal of Neuroscience. Society for Neuroscience, 2(10), pp. 1424–1438. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.02-10-01424.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwaber JS et al. (1982) ‘Amygdaloid and basal forebrain direct connections with the nucleus of the solitary tract and the dorsal motor nucleus.’, The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 2(10), pp. 1424–38. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6181231 (Accessed: 25 July 2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott KP et al. (2013) ‘The influence of diet on the gut microbiota’, Pharmacological Research. Academic Press, 69(1), pp. 52–60. doi: 10.1016/J.PHRS.2012.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Severance EG, Yolken RH and Eaton WW (2016) ‘Autoimmune diseases, gastrointestinal disorders and the microbiome in schizophrenia: more than a gut feeling’, Schizophrenia Research, 176(1), pp. 23–35. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2014.06.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin LM and Liberzon I. (2010) ‘The Neurocircuitry of Fear, Stress and Anxiety Disorders’, Neuropsychopharmacology. Nature Publishing Group, 35(1), pp. 169–191. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skosnik PD and Cortes-Briones JA (2016) ‘Targeting the ecology within: The role of the gut–brain axis and human microbiota in drug addiction’, Medical Hypotheses. Churchill Livingstone, 93, pp. 77–80. doi: 10.1016/J.MEHY.2016.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Söderpalm B. and Ericson M. (2011) ‘Neurocircuitry Involved in the Development of Alcohol Addiction: The Dopamine System and its Access Points’, in. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, pp. 127–161. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-28720-6_170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon RL and Corbit JD (1974) ‘An opponent-process theory of motivation: I. Temporal dynamics of affect.’, Psychological Review, 81(2), pp. 119–145. doi: 10.1037/h0036128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spengler RN et al. (1994) ‘Endogenous norepinephrine regulates tumor necrosis factor-alpha production from macrophages in vitro.’, The Journal of Immunology, 152(6). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabo G. and Mandrekar P. (2009) ‘A Recent Perspective on Alcohol, Immunity, and Host Defense’, Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd (10.1111), 33(2), pp. 220–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00842.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamboli CP et al. (2004) ‘Dysbiosis in inflammatory bowel disease.’, Gut. BMJ Publishing Group, 53(1), pp. 1–4. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14684564 (Accessed: 4 March 2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka M. et al. (2000) ‘Noradrenaline systems in the hypothalamus, amygdala and locus coeruleus are involved in the provocation of anxiety: basic studies’, European Journal of Pharmacology. Elsevier, 405(1–3), pp. 397–406. doi: 10.1016/S0014-2999(00)00569-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thayer JF and Lane RD (2000) ‘A model of neurovisceral integration in emotion regulation and dysregulation’, Journal of Affective Disorders. Elsevier, 61(3), pp. 201–216. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327(00)00338-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Timary P. et al. (2015) ‘A dysbiotic subpopulation of alcohol-dependent subjects’, Gut Microbes. Taylor & Francis, 6(6), pp. 388–391. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2015.1107696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaish A, Grossmann T. and Woodward A. (2008) ‘Not All Emotions Are Created Equal: The Negativity Bias in Social-Emotional Development’, Psychological Bulletin. NIH Public Access, 134(3), pp. 383–403. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.134.3.383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanBuskirk KA and Potenza MN (2010) ‘The treatment of obesity and its co-occurrence with substance use disorders’, Journal of Addiction Medicine. NIH Public Access, pp. 1–10. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0b013e3181ce38e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vengeliene V. et al. (2009) ‘Neuropharmacology of alcohol addiction’, British Journal of Pharmacology. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd (10.1111), 154(2), pp. 299–315. doi: 10.1038/bjp.2008.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Wise RA and Baler R. (2017) ‘The dopamine motive system: implications for drug and food addiction’, Nature Reviews Neuroscience. Nature Publishing Group, 18(12), pp. 741–752. doi: 10.1038/nrn.2017.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F. et al. (2018) ‘Morphine induces changes in the gut microbiome and metabolome in a morphine dependence model’, Scientific Reports. Nature Publishing Group, 8(1), p. 3596. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-21915-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X. et al. (2012) ‘Morphine activates neuroinflammation in a manner parallel to endotoxin’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109(16), pp. 6325–6330. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1200130109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise RA (2008) ‘Dopamine and reward: The anhedonia hypothesis 30 years on’, Neurotoxicity Research. NIH Public Access, 14(2–3), pp. 169–183. doi: 10.1007/BF03033808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise RA and Koob GF (2014) ‘The Development and Maintenance of Drug Addiction’, Neuropsychopharmacology. Nature Publishing Group, 39(2), pp. 254–262. doi: 10.1038/npp.2013.261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiss DA (2018) ‘The role of nutrition in addiction recovery: What we know and what we don’t’, in The Assessment and Treatment of Addiction: Best Practices and New Frontiers. Elsevier, pp. 21–42. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-323-54856-4.00002-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L. et al. (2016) ‘Systemic inflammation induces anxiety disorder through CXCL12/CXCR4 pathway’, Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 56, pp. 352–362. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2016.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]