Abstract

Background:

Relapsed/refractory (R/R) acute myeloid leukemia (AML) has poor outcomes. While lower-intensity venetoclax-containing regimens are standard for older/unfit patients with newly diagnosed AML, it is unknown how such regimens compare to intensive chemotherapy (IC) for R/R AML.

Methods:

We compared outcomes of R/R AML treated with 10-day decitabine and venetoclax (DEC10-VEN) vs. IC-based regimens including idarubicin with cytarabine (IA), with or without cladribine (CLIA), clofarabine (CIA), or fludarabine (FIA or FLAG-IDA), with or without additional agents. Propensity scores derived from baseline characteristics of were used to match DEC10-VEN and IC patients to minimize bias.

Results:

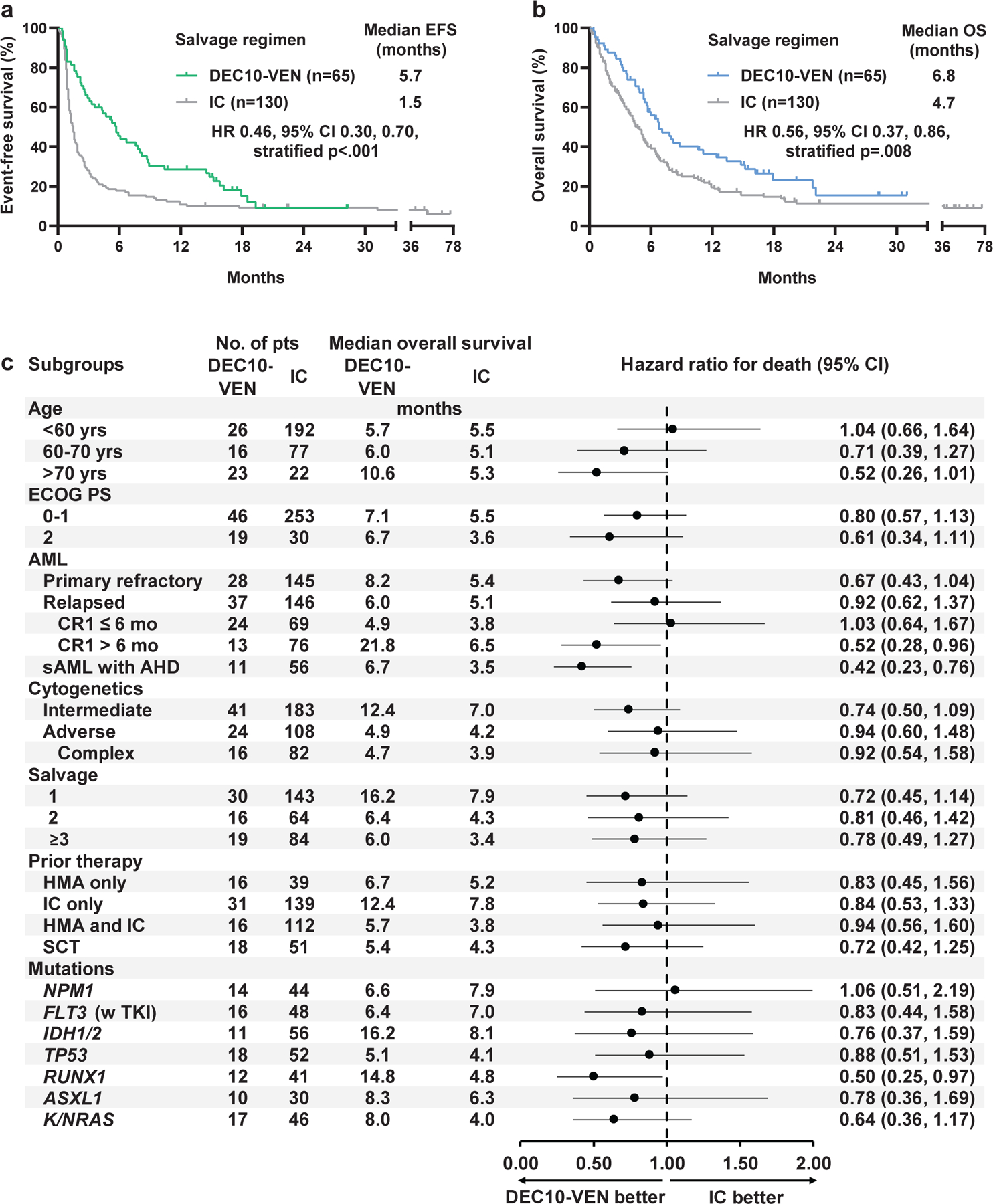

Sixty-five patients in DEC10-VEN cohort were matched to 130 IC recipients. The median age for DEC10-VEN and IC groups were 64 and 58 years, respectively, and baseline characteristics were balanced between the two cohorts. DEC10-VEN conferred significantly higher responses compared to IC including higher overall response rate (60% vs 36%, odds ratio [OR]= 3.28, p<.001), CRi (19% vs 6%, OR 3.56, p=.012), MRD-negative by flow cytometry (28% vs 13%, OR 2.48, p=.017) and lower rates of refractory disease. DEC10-VEN led to significantly longer median event-free survival (EFS) compared to IC (5.7 vs 1.5 months, hazard ratio [HR]=0.46, 95%CI 0.30–0.70, p<.001) as well as median overall survival (OS, 6.8 vs 4.7 months, HR=0.56, 95%CI 0.37–0.86, p=.008). DEC10-VEN was independently associated with improved OS compared to IC in multivariate analysis. Exploratory analysis for OS in 27 subgroups showed that DEC10-VEN was comparable to IC as salvage therapy for R/R AML.

Conclusion:

DEC10-VEN represents an appropriate salvage therapy and may offer better responses and survival compared to IC in adults with R/R AML.

Keywords: venetoclax, decitabine, intensive chemotherapy, AML, relapsed, refractory

Precis for use in Table of Contents

Ten-day decitabine with venetoclax (DEC10-VEN) offers potentially better outcomes compared to intensive chemotherapy for patients with relapsed or refractory acute myeloid leukemia. DEC10-VEN was associated with higher response rates, MRD-negativity and longer overall and event-free survival compared to intensive chemotherapy in R/R AML.

INTRODUCTION

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) with intermediate or adverse risk features have poor outcomes and more than 30–60% patients experience either refractory disease or relapse.1 Apart from AML with actionable mutations (e.g. FLT3, IDH1/2), there are no standard treatments for relapsed or refractory (R/R) AML and outcomes are poor with long-term survival of only 10–20%.2,3 With disease progression or each subsequent therapy, including stem-cell transplantation (SCT), it often becomes challenging to continue intensive chemotherapy (IC) in such patients. Consequently, R/R AML remains to be a therapeutic challenge with urgent need for novel lower-intensity therapies.

In newly diagnosed patients, venetoclax-containing lower intensity regimens are the current standard of care for older or unfit patients with AML.4,5 Venetoclax with hypomethylating agents (HMA) is potentially better than IC as frontline therapy for older patients including those who are eligible for IC.6 Such venetoclax-based lower intensity regimens are potentially efficacious in younger patients as well and prospective trials in this population are currently ongoing. We reported the results of the first prospective trial of venetoclax with decitabine in patients with R/R AML who are older than 18 years.7 However, it is unknown how such venetoclax and HMA regimens compare to IC for R/R AML.

Herein, we compared the outcomes of adult patients with R/R AML treated with 10-day decitabine and venetoclax (DEC10-VEN) on a phase 2 trial (NCT03404193) with outcomes of patients treated with IC.

METHODOLOGY

Patients and Treatment

The R/R cohort in the prospective phase 2 trial of DEC10-VEN enrolled adults older than 18 years with ECOG performance status (PS) of 3 or lower. Patients with ELN favorable risk cytogenetics or prior exposure to venetoclax were excluded. Patients received decitabine 20 mg/m2 daily for 10 days every 4–6 weeks with venetoclax 400 mg daily or equivalent (with concomitant azole antifungals) for induction. Subsequently after achievement of a response, patients received decitabine for 5 days with daily venetoclax for consolidation. Patients received cytoreduction to WBC <10×109/L prior to starting. All patients received monitoring and prophylaxis for tumor lysis syndrome (TLS), and antimicrobial prophylaxis during neutropenia.8

Patients in the comparator IC cohort were older than 18 years with ECOG performance status of 3 or lower. Patients received salvage therapy with either IA, CLIA, CIA, FIA or FLAG-Ida-based regimens without venetoclax on prospective phase 1b/2 clinical trials or as standard of care (Table S1A). The IA-based regimen comprised of idarubicin 10–12 mg/m2 IV on days 1–3 and cytarabine 1–2 g/m2 IV on days 1–4. CLIA-based regimens comprised of cladribine 5 mg/m2 IV on days 1–5, cytarabine 1–2 g/m2 IV on days 1–5 and idarubicin 10 mg/m2 IV on days 1–3. CIA-based regimens included clofarabine 15 mg/m2 IV daily on days 1–5, idarubicin 10 mg/m2 IV daily on days 1–3, and cytarabine 1 g/m2 IV daily on days 1–5. FLAG-Ida or FIA-based regimens included fludarabine 30 mg/m2 IV on D1–5, idarubicin 10 mg/m2 IV daily on days 1–3, and cytarabine 1–2 g/m2 IV daily on days 1–5, with or without filgrastim 5 mcg/kg SC on days 1–7. Details of additional agents in overall population and matched population are mentioned in Table S1B and S1C.

Response Assessment and Outcomes

Responses were graded per the European LeukemiaNet 2017 guidelines.9 Overall response rate (ORR) include complete remission (CR), CR with incomplete hematologic recovery (CRi) and morphologic leukemia-free state (MLFS). Response was established by the time of completion of up to two cycle of IC and up to four cycles of DEC10-VEN. Minimal residual disease was assessed in bone marrow specimens using multiparametric flow cytometry validated to a sensitivity level of 0.01–0.1%.10 Adverse events were determined per the NCI Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events v4.0. Event-free survival (EFS) was defined for all patients and was measured from start of therapy to the date of primary refractory disease, or relapse from CR/CRi, or death from any cause; patients not known to have either of these events were censored at last follow-up. Overall survival (OS) was measured from start of therapy until death or censored at last follow-up. Relapse-free survival was measured from date of achievement of CR/CRi, until relapse, death or censored at last follow-up.

Statistical Analysis

Propensity score methods in retrospective studies attempt to approximate populations in randomized controlled trials. This is achieved by selecting for comparable patient characteristics by balancing specified co-variates between comparator groups using propensity scores to reduce the potential for confounding or bias in estimating treatment effect in observational studies.11 A propensity score is the probability that a given patient would receive a given treatment based on their clinical scenario, treating clinician, and care setting.12 Propensity scores were calculated by logistic regression using baseline characteristics well recognized to be prognostic in the salvage setting including age, ECOG performance status, number of prior lines of therapies, primary refractory vs relapsed disease, CR1 duration, prior allogeneic stem-cell transplantation, ELN cytogenetic risk, FLT3 and TP53 mutation status.13,14 Propensity score matching (PSM) with the nearest neighbor method was used to select the IC comparison group using a 1:2 matching with a caliper control of 0.3.15,16

Pairwise comparison of patient characteristics and outcomes were performed using the t-test or the Wilcoxon signed-rank test for continuous variables, and the McNemar’s test for categorical variables or the Fischer’s exact test for unpaired comparisons. The Kaplan-Meier method with stratified log-rank test were used to compare time-to-event variables. The Cox proportional-hazards model with stratification to account for matched pairs was used to estimate the hazard ratio between comparator groups. Univariate and multivariable Cox models were used in the unmatched population to evaluate the associations between patient characteristics and OS. Factors significant in the univariate models at significance level 0.1 were included in the multivariate model. Backward model selection was used to remove variables from the model until all remaining variables were statistically significant with p<0.05 while treatment effect variable was forced in the final multivariable model. SPSS 24 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY), R Essentials for SPSS version 24, PSMATCHING3.03 package, and R version 3.2 (R Foundation, Vienna, Austria) were used for analysis.

RESULTS

Patients

Sixty-five out of 65 patients treated with DEC10-VEN were best matched to 130 out of 291 patients treated with IC (Fig. S1). The standardized mean differences of variables selected for PSM before and after matching was low (range, −0.04 to 0.23) suggesting significant reduction of bias between the two intervention groups (Table S2). Patients in DEC10-VEN cohort were treated between January 2018 and September 2020 while patients in IC cohort received treatment between June 2005 and July 2019. The median age of the DEC10-VEN cohort was 64 years (range 18–85) and for the IC cohort was 58 years (range 19–80) and baseline characteristics were well balanced between the two groups (Table 1). The median number of prior lines of therapy was similar in DEC10-VEN and IC cohorts at 2 (range 1–8) vs. 2 (range 1–10), respectively (p=.721). Details of regimens administered in the IC cohort are shown in Table S1C. In DEC10-VEN cohort, patients received a median of 2 cycles of therapy (range 1–16) and in IC cohort patients had received a median of 1 cycle of therapy (range 1–5). FLT3 inhibitors were used in 16 out of 16 patients treated with DEC10-VEN compared to 25 out of 34 patients treated with IC (p=.043). No patients in either group received IDH1/2 inhibitors.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of matched patients with relapsed or refractory acute myeloid leukemia who received 10-day decitabine with venetoclax (DEC10-VEN), and intensive chemotherapy (IC)

| Patient characteristics | DEC10-VEN (N=65) | IC (N=130) |

p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 64 [18–85] | 58 [19–80] | .113 |

| <60 years | 26 (40) | 74 (57) | .038 |

| Male sex | 39 (60) | 72 (55) | .539 |

| AML type | |||

| Primary refractory AML | 28 (43) | 54 (42) | .837 |

| Relapsed AML | 37 (57) | 76 (58) | .891 |

| Secondary AML from AHD | 11 (17) | 21 (16) | |

| ECOG performance status | |||

| 0–1 | 46 (71) | 95 (73) | .734 |

| ≥2 | 19 (29) | 35 (27) | |

| Bone marrow blasts, % | 34 [1–96] | 35 [0–98] | .536 |

| ELN 2017 cytogenetic group | |||

| Favorable | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | .958 |

| Intermediate | 41 (63) | 80 (62) | |

| Adverse | 24 (37) | 50 (38) | |

| Mutations | |||

| NPM1 | 14 (22) | 15 (12) | .605 |

| FLT3-ITD/TKD | 16 (25) | 34 (26) | |

| IDH1/2 | 11 (17) | 28 (22) | |

| TP53 | 18 (28) | 32 (25) | |

| RUNX1 | 12 (18) | 22 (17)1 | |

| ASXL1 | 10 (15) | 14 (11)1 | |

| ELN 2017 risk group | |||

| Favorable | 10 (15) | 11 (8) | .302 |

| Intermediate | 12 (18) | 30 (23) | |

| Adverse | 43 (66) | 89 (68) | |

| No. of prior therapies | 2 [1–8] | 2 [1–10] | .721 |

| Prior therapies | |||

| HMA only | 16 (25) | 24 (18) | .214 |

| IC only | 31 (48) | 53 (41) | |

| IC and HMA | 16 (25) | 53 (41) | |

| SCT | 18 (28) | 36 (28) |

Results reported as n (%), or median [range]. AHD = antecedent hematological disorder, ELN = European LeukemiaNet. IC = intensive chemotherapy, HMA = hypomethylating agent, SCT = allogeneic stem cell transplantation.

RUNX1 and ASXL1 status was unknown for 9 patients.

Efficacy: Response Rates

Rates of overall response (ORR), CRi, MLFS and negative MRD by flow cytometry were significantly higher with DEC10-VEN compared to IC. ORR was achieved in 60% patients with DEC10-VEN vs 36% patients treated with IC, odds ratio [OR], 3.28, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.73, 6.23, stratified test p<.001, (Table 2). CRi rates were 19% vs 6%, respectively, OR 3.56, 95% CI 1.32, 9.61, stratified test p=.012, rates of MLFS were 15% vs. 5%, respectively, OR 3.33, 95% CI 1.21, 9.17, stratified test p=.020, and MRD-negative rate was 28% vs 13%, respectively, OR 2.48, 95% CI 1.17, 5.24, stratified test p=.017. The rate of refractory disease was significantly lower with DEC10-VEN (35% vs 55%, OR 0.46, 95% CI 0.25, 0.84, stratified test p=.011). The median no. of cycles to best response in DEC10-VEN cohort was 1 (range 1–4) and in IC cohort was 1 (range 1–3).

Table 2.

Outcomes of propensity of matched patients with relapsed or refractory acute myeloid leukemia who received 10-day decitabine with venetoclax (DEC10-VEN), and intensive chemotherapy (IC)

| Outcomes | DEC10-VEN (N=65) | IC (N=130) |

OR / HR (95% CI) | Stratified p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall response rate (ORR) | 37 (60) | 36 (28) | 3.28 (1.73, 6.23) | <.001 |

| CR/CRi | 27 (42) | 30 (23) | 2.52 (1.26, 5.03) | .009 |

| CR | 15 (23) | 22 (17) | 1.44 (0.70, 2.94) | .320 |

| CRi | 12 (19) | 8 (6) | 3.56 (1.32, 9.61) | .012 |

| MLFS | 10 (15) | 6 (5) | 3.33 (1.21, 9.17) | .020 |

| MRD negativity | 18 (28) | 17 (13) | 2.48 (1.17, 5.24) | .017 |

| Refractory | 22 (35) | 71 (55) | 0.46 (0.25, 0.84) | .011 |

| Inevaluable1 | 1 (2) | 1 (1) | 2.00 (0.13, 31.98) | .624 |

| Relapse | 19 (51) | 17 (47) | 0.75 (0.24, 2.38) | .630 |

| 30-day mortality | 5 (8) | 16 (12) | 0.58 (0.2, 1.70) | .322 |

| 60-day mortality | 8 (12) | 35 (27) | 0.40 (0.18, 0.91) | .029 |

Results reported as n (%), n/N (%). ORR = CR+CRi+MLFS, CR = complete remission; CRi = CR with incomplete hematologic recovery, MLFS = morphologic leukemia-free state. MRD = minimal residual disease evaluated using multiparametric flow cytometry validated to a sensitivity level of 0.1–0.01%; OR = odds ratio; HR = hazard ratio, NA= not applicable,

One patient was taken off DEC10-VEN after receiving only 2 days of therapy and another patient was taken off IC after 1 day off therapy due to adverse event

Efficacy: Survival Outcomes

The median follow-up for the DEC10-VEN cohort was 17.5 months and for IC cohort was 49.3 months. The median EFS with DEC10-VEN was 5.7 months versus 1.5 months with IC (hazard ratio [HR] 0.46, 95% CI 0.30, 0.70, stratified test p<.001, Fig. 1a). The median OS with DEC10-VEN was 6.8 months compared to 4.7 months with IC (HR 0.56, 95% CI 0.37, 0.86, stratified test p=.008, Fig. 1b). Relapse-free survival was similar with DEC10-VEN and IC (8.4 vs 8.4 months, HR 1.103, 95% CI 0.59, 2.07, p=.743, Fig. S2). Fifteen patients (23%) in the DEC10-VEN cohort and 21 patients (16%) in the matched IC cohort received SCT after achievement of a response (p=.247). The median OS after SCT was numerically higher in DEC10-VEN vs IC cohorts (18.7 vs 12.9 months, HR 1.11, 95% CI 0.44, 2.84, p=.813, Fig. S3).

Fig. 1.

a.Event-free survival (EFS), and b. Overall survival (OS) in patients with relapsed or refractory acute myeloid leukemia who received salvage therapy with 10-day decitabine with venetoclax (DEC10-VEN) versus intensive chemotherapy (IC); c. exploratory subgroup analysis for OS in unmatched populations.

The dotted line represents hazard ratio of 1.00. Only patients receiving FLT3 inhibitors were chosen for the subgroup analysis comparing outcomes in FLT3mut AML. All 16 patients treated with DEC10-VEN received FLT3 inhibitor including gilteritinib (n=7), sorafenib (n=6), midostaurin (n=3); and all 48 selected patients treated with intensive chemotherapy received FLT3 inhibitor including sorafenib (n=33), crenolanib (n=10), gilteritinib (n=2), midostaurin (n=2), and ponatinib (n=1). ECOG PS = Eastern Co-operative Oncology Group performance status, sAML = secondary AML, AHD = antecedent hematological disorder, HMA = hypomethylating agent, SCT = allogeneic stem-cell transplantation.

Exploratory subgroup analyses for OS in unmatched cohorts showed that DEC10-VEN was comparable to IC across most subgroups of age, diagnosis, cytogenetic risk, line of salvage therapy, type of previous therapy, and major mutational subgroups (Fig. 1c). Although 95% CI were wide, the HRs marginally favored DEC10-VEN in most subgroups and the benefit was significant in patients with CR1 duration of more than 6 months and patients with antecedent hematological disorder. In patients with CR1 duration more than 6 months, the median OS with DEC10-VEN was 21.8 months (n=13) compared to 6.5 months with IC (n=76, HR 0.52, 95% CI 0.28, 0.96, p=.023). In patients with antecedent hematological disorder, the median OS with DEC10-VEN was 6.7 months (n=11) compared to 3.5 months with IC (n=56, HR 0.42, 95% CI 0.23, 0.76, p=.017). Patients with FLT3mut AML treated with DEC10-VEN and FLT3 inhibitor (n=16) versus IC with FLT3 inhibitor (n=48) had comparable OS (6.4 months vs 7.0 months, HR 0.83, 95% CI 0.44, 1.58, p=0.587).

Multivariate analysis for OS in unmatched population showed that DEC10-VEN was independently associated with significant improvement in OS (HR 0.66, 95% CI 0.48, 0.92, p=.012; Table S3) and IDH1/2 mutation was associated with a lower risk of death (HR 0.70, 95% CI, 0.51, 0.97, p=.029). There was higher risk of death in patients with an antecedent hematological disorder (HR 1.84, 95% CI 1.35, 2.51, p<.001), ELN adverse risk cytogenetics (HR 1.57 95% CI 1.21, 2.03, p<.001), TP53 mutation (HR 1.71, 95% CI 1.25, 2.34, p<.001), and failure two or more lines of therapy. Overall survival was comparable among patients who achieved CR or CR/CRi with DEC10-VEN or IC (Fig. S4, S5)

Safety

The 60-day mortality was 12% (n=8) with DEC10-VEN compared to 27% (n=35) with IC (OR 0.40, 95% CI 0.18, 0.91, stratified test p=.029). Prospectively collected adverse event data was available for all patients in DEC10-VEN cohort compared to 28 patients (22%) in IC cohort. Non-hematologic grade 3/4 treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAE), at least possible related to study regimen, occurred in 21 (75%) of 28 patients receiving IC and 45 (69%) of 65 patients receiving DEC10-VEN (p=.628, Table 3). Grade 3/4 infectious AEs occurred in 25 out of 65 (38%) patients in DEC10-VEN cohort compared to 5 out of 28 (18%) patients in IC (p=.057). Febrile neutropenia was noted in 20 patients (30%) in DEC10-VEN cohort compared to 14 patients (50%) in IC cohort (p=.101).

Table 3.

Adverse events in propensity score matched patients with relapsed or refractory acute myeloid leukemia who received 10-day decitabine with venetoclax (DEC10-VEN) versus intensive chemotherapy (IC).

| Event | DEC10-VEN (n=65) | IC (n=28) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any grade | Grade 3/4 | Any grade | Grade 3/4 | |

| Infection with ANC <1.0 × 109/L | 25 (38) | 25 (38) | 6 (21) | 5 (17) |

| Febrile neutropenia | 20 (30) | 20 (30) | 14 (50) | 14 (50) |

| Infection with ANC >1.0 × 109/L | 14 (21) | 11 (16) | 3 (10) | 3 (10) |

| Mucositis | 4 (6) | .. | 4 (14) | 1 (3) |

| Hyperbilirubinemia | 3 (4) | 3 (4) | 8 (28) | 2 (7) |

| Nausea | 3 (4) | .. | 1 (3) | . |

| Tumor lysis syndrome | 3 (4) | 1 (1) | 1 (3) | 1 (3) |

| Constipation | 2 (3) | .. | .. | . |

| Renal Failure | 2 (3) | 2 (3) | .. | . |

| Pain | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 4 (14) | 2 (7) |

| Hypokalemia | 1 (1) | .. | .. | . |

| Vomiting | 1 (1) | .. | .. | . |

| ALT/AST elevation | .. | .. | 10 (35) | 1 (3) |

| Hemorrhage | .. | .. | 4 (14) | 3 (10) |

| Rash | .. | .. | 4 (14) | .. |

| Creatinine elevation | .. | .. | 3 (10) | .. |

| Altered mental status | .. | .. | 1 (3) | 1 (3) |

| Cardiac arrhythmia | .. | .. | 1 (3) | .. |

| Cholecystitis | .. | .. | 1 (3) | 1 (3) |

| Dyspnea | .. | .. | 1 (3) | 1 (3) |

| Hypoxia | .. | .. | 1 (3) | 1 (3) |

| Pruritus | .. | .. | 1 (3) | .. |

ANC = absolute neutrophil count, ALT = alanine aminotransferase, AST = aspartate aminotransferase CNS = central nervous system.

DISCUSSION

Heterogeneous biology in R/R AML without actionable mutations make it a challenging disease for drug development and only modest progress has been made in the last several decades. While IC has been the mainstay so far, declining functional status in R/R AML and treatment-related toxicities are considerable barriers to treatment and limit the testing of novel agents due to risk of additive toxicity. Venetoclax-based lower intensity regimens have been a paradigm shifting development in the field owing to modest end-organ toxicity apart from myelosuppression and resultant infections. This has enabled treatment delivery in frail patients who otherwise would not have tolerated intensive therapies and have accelerated the development of rational combination therapies in AML.

Our retrospective comparison shows that DEC10-VEN is an appropriate option for venetoclax-naïve patients with R/R AML. In a population with a median of 2 prior lines of therapy and majority with adverse risk AML, DEC10-VEN showed significantly higher ORR, rate of CRi, MRD-negativity, lower rates of 60-day mortality, refractory disease and significantly longer EFS and OS. The OS benefit noted was further confirmed on multivariate analysis. While OS was only modestly improved compared to IC, it was encouraging to note that the despite potential confounders, the HRs across most subgroups favored DEC10-VEN over IC. In particular, the trend noted in patients with antecedent hematological disorder, CR1 duration longer than 6 months and RUNX1 mutations was encouraging. It is possible that the improvement in OS may have been due to patients surviving with MLFS. Although significantly more patients achieved MLFS compared to IC, it did not translate into significantly higher number of patients transitioning to SCT in the DEC10-VEN cohort. However, attaining MLFS does provide the opportunity to take such patients to transplant as suboptimal responders can still experience OS benefit with SCT even in the absence of full count recovery.17 While our safety analysis focused on non-hematologic toxicity, some CRi and MLFS responses noted with DEC10-VEN can be potentially related to venetoclax-induced myelosuppression.

Based on these results we have initiated two phase II trials of oral regimens of 10-day and 5-day decitabine/cedazuridine (ASTX727) with venetoclax for R/R AML (NCT04746235), however, prospective randomized studies are needed to confirm these findings. Ongoing evaluation of venetoclax with FLAG-IDA (NCT03214562), CPX-351 (NCT03629171), and CLIA (NCT02115295) have shown promising early results and will help determine the optimal backbone for venetoclax in R/R AML.18,19 However, for patients with multiply R/R AML with poor PS who are venetoclax-naïve and ineligible for intensive therapy, DEC10-VEN maybe a potential salvage option.

This was a retrospective study with all inherent limitations. However, propensity score matching for important effect modifiers and treatment in prospective clinical trials helped to minimize such bias, as noted from the low standardized mean differences after matching and similar baseline characteristics in the cohorts. Although propensity score matching can balance important effect modifiers, there could have still been other factors which influenced the differences observed. While many other baseline characteristics and comorbidities could have influenced findings in our multivariable analysis, retrospective nature of this study and some missing data precluded inclusion of those factors. We had limited patients in the DEC10-VEN cohort for exploratory subgroup analysis which resulted in large confidence intervals decreasing the precision of our findings. All these trials were single-center studies and outcomes maybe have been different in other institutions or the community, particularly with other common regimens like MEC, CLAG, etc. Provision of two more cycles of treatment for responses assessment with DEC10-VEN compared to IC introduced the potential for immortal time bias in our analysis. However, retrospective results of venetoclax with HMA in R/R AML have shown identical to better outcomes supporting reproducibility of our findings.20 Overall, these results raise new questions and warrant validation in larger studies.

In conclusion, this retrospective analysis suggests that DEC10-VEN may be considered as a potential salvage option offering outcomes comparable to non-venetoclax based IC in patients with R/R AML who have not received venetoclax before. The high ORR, rates of CRi, MLFS, MRD-negativity, better OS, EFS, and low-intensity nature makes this regimen a potential option as a bridge to SCT, and as a reasonable choice for a low-intensity backbone for adding novel therapies in the salvage setting.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

This study was supported in part by the MD Anderson Cancer Center Support Grant CA016672 from the National Cancer Institute and the Research Project Grant Program (R01CA235622) from the National Institutes of Health. A. Maiti was supported by the American Society of Clinical Oncology Young Investigator Award from the Conquer Cancer Foundation. We thank the patients, their caregivers, and members of the study teams involved in these trials.

Financial disclosures:

AM: Research funding from Celgene Corporation. CDD: Personal fees from Abbvie, personal fees from Agios, personal fees from Novartis, personal fees from ImmuneOnc, personal fees from Daiichi Sankyo, personal fees from Celgene, personal fees from Jazz, personal fees from Notable Labs, outside the submitted work. TMK: None, EJJ: Consultancy Research funding from Takeda, BMS, Adaptive, Amgen, AbbVie, Pfizer, Cyclacel LTD, Research grants with Amgen, Abbvie, Spectrum, BMS, Takeda, Pfizer and Adaptive. CRR: None. NGD: reports grants from Abbvie, Genentech, Astellas, Daiichi-Sankyo, Pfizer, BMS, Immunogen, Novimmune, Forty-seven; personal fees from Abbvie, Genentech, Astellas, Daiichi-Sankyo, Pfizer, BMS, Immunogen, Jazz pharmaceuticals, Trillium, Forty-seven, Gilead, Kite, Novartis NP: reports personal fees from Pacylex Pharmaceuticals, grants and other from Affymetrix, grants from SagerStrong Foundation, personal fees from Incyte, personal fees and other from Novartis, personal fees from LFB Biotechnologies, personal fees, non-financial support and other from Stemline Therapeutics, personal fees and non-financial support from Celgene, personal fees, non-financial support and other from AbbVie, personal fees and non-financial support from MustangBio, personal fees from Roche Diagnostics, personal fees from Blueprint Medicines, personal fees and non-financial support from DAVA Oncology, other from Samus Therapeutics, other from Cellectis, other from Daiichi Sankyo, other from Plexxikon, outside the submitted work. GB: AbbVie: Research Funding; Incyte: Research Funding; Janssen: Research Funding; GSK: Research Funding; Cyclacel: Research Funding; BioLine Rx: Consultancy and Research Funding; NKarta: Consultancy; PTC Therapeutics: Consultancy; Oncoceutics, Inc.: Research Funding. NJS: reports grants from Takeda Oncology, Astellas; Personal fees from Takeda Oncology, AstraZeneca, Amgen. YA: none. MY: None. KSM: None. AW: None. REM: None. JAG: None. KV: None. CAB: None. SAP: None. HMK: grants and other from AbbVie, grants and other from Agios, grants and other from Amgen, grants from Ariad, grants from Astex, grants from BMS, from Cyclacel, grants from Daiichi-Sankyo, grants and other from Immunogen, grants from Jazz Pharma, grants from Novartis, grants and other from Pfizer, other from Actinium, other from Takeda, outside the submitted work. FR: Personal fees and research grants from Abbvie. MYK: has received grants from NIH, NCI, Abbvie, Genentech, Stemline Therapeutics, Forty-Seven, Eli Lilly, Cellectis, Calithera, Ablynx, Astra Zeneca; Consulting/honorarium from AbbVie, Genentech, F. Hoffman La-Roche, Stemline Therapeutics, Amgen, Forty-Seven, Kisoji; clinical trial support from Ascentage; stocks/royalties in Reata Pharmaceutical.

Funding:

National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, Conquer Cancer Foundation.

Footnotes

Clinical trial registration information: NCT03404193

Data sharing: Please contact the corresponding author with request for original patient level data.

References

- 1.Herold T, Rothenberg-Thurley M, Grunwald VV, et al. Validation and refinement of the revised 2017 European LeukemiaNet genetic risk stratification of acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia 2020;1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roboz GJ, Rosenblat T, Arellano M, et al. International randomized phase III study of elacytarabine versus investigator choice in patients with relapsed/refractory acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol 2014;32(18). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bose P, Vachhani P, Cortes JE. Treatment of Relapsed/Refractory Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Curr Treat Options Oncol 2017;18(3):17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DiNardo CD, Jonas BA, Pullarkat V, et al. Azacitidine and Venetoclax in Previously Untreated Acute Myeloid Leukemia. N Engl J Med 2020;383(7):617–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wei AH, Montesinos P, Ivanov V, et al. Venetoclax plus LDAC for newly diagnosed AML ineligible for intensive chemotherapy: a phase 3 randomized placebo-controlled trial. Blood 2020;135(24):2137–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maiti A, Qiao W, Sasaki K, et al. Venetoclax with decitabine vs intensive chemotherapy in acute myeloid leukemia: A propensity score matched analysis stratified by risk of treatment‐related mortality. Am J Hematol 2021;96(3):282–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DiNardo CD, Maiti A, Rausch CR, et al. 10-day decitabine with venetoclax for newly diagnosed intensive chemotherapy ineligible, and relapsed or refractory acute myeloid leukaemia: a single-centre, phase 2 trial. Lancet Haematol 2020;7:e724–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DiNardo CD, Maiti A, Rausch CR, et al. 10-day Decitabine with Venetoclax in Acute Myeloid Leukemia: A Single-center Phase 2 Trial. Lancet Haematol 2020;In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Döhner H, Estey E, Grimwade D, et al. Diagnosis and management of AML in adults: 2017 ELN recommendations from an international expert panel. Blood 2017;129(4):424–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Short NJ, Ravandi F. How close are we to incorporating measurable residual disease into clinical practice for acute myeloid leukemia? Haematologica 2019;104(8):1532–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haukoos JS, Lewis RJ. The Propensity Score. JAMA 2015;314(15):1637–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika 1983;70(1):41–55. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Breems DA, Van Putten WLJ, Huijgens PC, et al. Prognostic Index for Adult Patients With Acute Myeloid Leukemia in First Relapse. J Clin Oncol 2005;23(9):1969–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schlenk RF, Müller-Tidow C, Benner A, Kieser M. Relapsed/refractory acute myeloid leukemia: any progress? Curr Opin Oncol 2017;29(6):467–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thomas L, Li F, Pencina M. Using Propensity Score Methods to Create Target Populations in Observational Clinical Research. JAMA 2020;323(5):466–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rubin DB. Using Propensity Scores to Help Design Observational Studies: Application to the Tobacco Litigation. Health Serv Outcomes Res Methodol 2001;2(3):169–88. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Short NJ, Rafei H, Daver N, et al. Prognostic impact of complete remission with MRD negativity in patients with relapsed or refractory AML. Blood Adv 2020;4(24):6117–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aboudalle I, Konopleva MY, Kadia TM, et al. A Phase Ib/II Study of the BCL-2 Inhibitor Venetoclax in Combination with Standard Intensive AML Induction/Consolidation Therapy with FLAG-IDA in Patients with Newly Diagnosed or Relapsed/Refractory AML. Blood 2019;134(Supplement_1):176–176. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kadia TM, Garcia-Manero G, Yilmaz M, et al. Venetoclax (Ven) added to intensive chemo with cladribine, idarubicin, and AraC (CLIA) achieves high rates of durable complete remission with low rates of measurable residual disease (MRD) in pts with newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia (AML). J Clin Oncol 2020;38(15_suppl):7539–7539. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bewersdorf JP, Giri S, Wang R, et al. Venetoclax as monotherapy and in combination with hypomethylating agents or low dose cytarabine in relapsed and treatment refractory acute myeloid leukemia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Haematologica [Internet] 2020. [cited 2020 Jul 8];Available from: http://www.haematologica.org/content/early/2020/01/21/haematol.2019.242826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.