Abstract

Purpose:

To address demands for timely germline information to guide treatments, we evaluated experiences of patients with ovarian, pancreatic, and prostate cancer with a mainstreaming genetic testing model wherein multigene panel testing was ordered by oncologists with standardized pre-test patient education, and genetic counselors delivered results and post-test genetic counseling via telephone.

Methods:

Among 1203 eligible patients, we conducted a prospective single-arm study to examine patient uptake and acceptability (via self-report surveys at baseline and three-weeks and three-months following result return) of this mainstreaming model.

Results:

Only 10% of eligible patients declined participation. Among 1054 tested participants, 10% had pathogenic variants (PV), 16% had variants of uncertain significance (VUS), and 74% had no variant identified (NV). Participants reported high initial acceptability, including high satisfaction with their testing decision. Variability over time in several outcomes existed for participants with PV or NV: Those with NV experienced a temporary increase in depression (pTime<0.001; pTime2<0.001), and those with PV experienced a small increase in genetic testing distress (p=0.03). Findings suggested that result type, sex, and cancer type were also associated with outcomes including clinical depression and uncertainty.

Conclusion:

This mainstreaming model may offer a feasible approach for extending access to germline genetic information.

Keywords: multigene panel testing, treatment-focused genetic testing, hereditary cancer, psychosocial outcomes

Introduction

Efficient yet effective genetic testing models are critically needed to meet growing demands for timely germline information to guide cancer treatment decisions. For example, targeted therapeutics, such as PARP inhibitors, are FDA-approved for patients with ovarian, pancreatic, and prostate cancer with inherited pathogenic variants (PV) in BRCA1/2, and may be effective for those with inherited PV in other DNA-repair genes (e.g., PALB2).1 Consequently, identification of a germline PV is important for clinical care. This information can also direct future cancer prevention strategies for patients and their families. However, traditional clinical genetics care delivery models are not well-aligned with the exigencies created by integrating germline information into standard oncologic care.

The traditional approach to delivering hereditary cancer genetic testing (HCGT) involves in-person, in-depth pre-test risk assessment, education, and genetic counseling by a genetic counselor; genetic testing; and then result notification with in-person, in-depth post-test counseling by a genetic counselor. Although this traditional model maximizes a patient’s ability to make an informed choice about HCGT by providing ample information and support, it is time and resource intensive, prompting the genetics community to consider alternative care models.2–5 For example, models employing remote delivery of genetic counseling through telephone6–8 have been adopted with equivalent outcomes including patient satisfaction, distress, and knowledge when compared to the in-person approach. Recently, “mainstreaming” models wherein non-genetics healthcare providers give patients information, obtain consent for HCGT, and directly order HCGT in lieu of traditional in-depth pre-test genetic counseling, and genetic counselors then provide support upon result disclosure, have begun to show potential in select populations. Observational studies of mainstreaming models for BRCA1/2 testing among women with breast or ovarian cancer have found positive outcomes in terms of patient uptake, satisfaction, and distress.9–14 Additionally, a single Australian RCT of a mainstreaming model for BRCA1/2 testing that incorporated mailed written educational materials with in-person post-test counseling produced similar levels of decisional conflict, distress, and knowledge as in-person pre- and post-test genetic counseling among 135 breast cancer patients.15 Although promising, these studies were limited to the setting of BRCA1/2 testing among women with breast or ovarian cancer. These studies also have not reflected the growing use of multigene panel testing (MGPT), a cost-effective, efficient HCGT approach involving the simultaneous analysis of multiple high- and moderate-penetrance cancer predisposition genes.16,17 To date, only one study has examined a mainstreaming model in conjunction with MGPT; a recent Australian prospective study of 66 men with prostate cancer found high uptake and satisfaction of oncologist-led MGPT ordering and result return.18

We sought to expand upon past research by implementing and evaluating a mainstreaming model for delivering MGPT to both female and male patients diagnosed with ovarian, pancreatic, and prostate cancer. Our mainstreaming model involved the delivery of standardized pre-test education and MGPT ordering by oncologists aided by study staff, with family history assessment, result return, and post-test genetic counseling delivered via telephone by genetic counselors. We conducted a prospective single-arm study to examine patient uptake and acceptability of MGPT through this mainstreaming model over time among patients receiving different test results. We operationalized patient acceptability as satisfaction with the pre-test education, genetic testing decision, and genetic counseling; anxiety; depression; genetic testing concerns; and knowledge. To gain additional insight into how patients may respond to this care model, we further explored how patient characteristics related to acceptability over time.

Materials and Methods

Participants

Participants were identified among predominantly advanced cancer patients seeing a medical oncologist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSK; NCT02917798) or the University of Pennsylvania (NCT03934606). Eligibility criteria included age 18 or older; diagnosis of invasive epithelial ovarian, peritoneal, fallopian tube, pancreatic, or prostate cancer; English-fluent (due to the language of educational materials and questionnaires); and deemed clinically appropriate for MGPT by the oncologist (e.g., a potential candidate for PARP inhibitors or clinical trials).

Procedure

Patients were recruited between October 2016-October 2019 during routine oncology appointments. During the appointment, the oncologist introduced the study and the prospect of MGPT to eligible patients, and with the support of study staff offered details about study participation and pre-test education through standardized, cancer-specific, educational materials. Materials were created by members of the study team including genetic counselors, oncologists, and a health psychologist along with the MSK Patient Education and Caregiver Department, and included an 8-minute video (script of approximately 6.9 grade reading level) and 2-page brochure (approximately 8.3 grade reading level) that provided an overview of hereditary cancer syndromes, MGPT risks and benefits, genes included in the MGPT, the meaning and implications of test results, and the ability to be referred to a genetic counselor prior to testing if desired, consistent with American Society of Clinical Oncology guidelines for informed consent in clinical cancer genetics.16 Following review of the pre-test educational materials, the oncologist and study staff were available to address any patient questions and to refer patients declining study participation to a genetic counselor for clinical testing if desired. Interested patients provided written informed consent for study participation and provided written informed consent and a blood or saliva sample for testing. MGPT included genes with clinical validity and potential actionability for patients with ovarian, pancreatic, or prostate cancer that are related to the specific cancer plus other hereditary cancers (e.g., colorectal cancer), many with potential therapeutic implications. The MGPT for patients with ovarian cancer included: ATM, BRCA1, BRCA2, BRIP1, EPCAM, MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PALB2, PMS2, RAD51C, RAD51D. The MGPT for patients with pancreatic cancer included: ATM, BARD1, BRCA1, BRCA2, CDK4, CDKN2A, CHEK2, EPCAM, FANCC, MEN1, MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, NBN, NF1, PALB2, PMS2, STK11, TP53, TSC1, TSC2, VHL. The MGPT for patients with prostate cancer included: ATM, BRCA1, BRCA2, CHEK2, EPCAM, FANCA, HOXB13, MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, NBN, PALB2, PMS2, RAD51C, RAD51D, TP53. Of further note, at the time of this study MGPT was a standard-of-care billable service for patients with ovarian cancer. Therefore, patients whose insurers’ policies would allow for payment for MGPT as delivered in our mainstreaming model were offered participation in this study, and their insurance was billed for the MGPT. At the time of this study, MGPT was not a standard-of-care billable service for patients with pancreatic or prostate cancers, and these patients therefore received no-cost MGPT through the study.

Participants completed a baseline survey following consent. Genetic counselors then contacted participants by telephone to obtain family history information for pedigree construction and to deliver test results with standard-of-care in-depth post-test genetic counseling and discussion of appropriate medical management recommendations (including management of VUS according to family history and the possibility of additional reflex testing). Although the study workflow allowed for genetic counselors to ascertain family history via a separate telephone call prior to that used for disclosing test results, in 80% of cases these activities occurred during a single telephone call. Participants completed post-results disclosure follow-up surveys within three weeks and three months following receipt of their test results; surveys were completed via email, telephone, or paper at an appointment or by mail. The participating sites’ Institutional Review Boards approved this study.

Measures

Sociodemographic and medical characteristics including age, race, ethnicity, sex, and cancer diagnosis were abstracted from patient records. Family cancer history was derived from pedigrees (computed as the proportion of first- and second-degree relatives diagnosed with a non-cutaneous cancer among the total number of first- and second-degree relatives). Health status (ECOG Performance Status19) and education were self-reported at baseline.

Satisfaction with pre-test education was assessed at baseline with four investigator-designed items measuring the extent to which participants liked the video and found it informative (the scale had good internal consistency in this sample with Cronbach’s α=0.72).

Genetic testing decision satisfaction was assessed at each timepoint with four items from the Satisfaction with Decisions scale,20 which evaluates the extent to which participants were satisfied, felt informed, and believed the decision was best for them and consistent with their values (α≥0.96).

Genetic counseling satisfaction was assessed at the follow-up timepoints with the six-item Genetic Counseling Satisfaction Scale,21 which evaluates participants’ satisfaction with their interactions with the genetic counselor and with the content and quality of the genetic counseling session (α≥0.91).

Knowledge about genetic testing was assessed at each timepoint as the percentage of correct responses to 12 investigator-designed “true/false/don’t know” items derived from the pre-test educational materials (α≥0.70).

Generalized anxiety and depression were assessed at each timepoint with the anxiety (α≥0.85) and depression (α≥0.85) subscales of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS).22

Genetic testing concerns were assessed at each follow-up timepoint with the Multidimensional Impact of Cancer Risk Assessment (MICRA) questionnaire,23 which includes subscales measuring participants’ test-related distress (α≥0.85), uncertainty (α≥0.78), and positive experiences (α≥0.74).

Statistical analyses

Patient uptake in terms of refusal (i.e., actively or passively declining to consent to the study) and non-completion (i.e., consenting but not completing the baseline survey and/or MGPT) were compared by patient characteristics. Chi-square tests were used to compare sex, race, ethnicity, cancer type, study site, and for non-completers, type of results; independent samples t-tests were used for age. Baseline sociodemographic and medical characteristics as well as baseline acceptability outcomes were examined overall and by type of results.

We also conducted a model-based analysis of longitudinal changes in patient acceptability, stratified by type of test results, using a series of hierarchical linear models (HLM) with random per-person intercepts and testing linear time effects. For each outcome, we tested models both with and without a quadratic time effect and used the model with the best fit to the data, as determined by Akaike Information Criteria (AIC). These HLM models thus incorporate data from all baseline and follow-up timepoints, including cases with intermittent missing data. Note that genetic testing concerns as measured with the MICRA were first assessed at the three-week follow-up and scores on the MICRA-Distress subscale were highly skewed and thus we applied a logarithmic transformation prior to analysis.

Finally, to explore correlates of the acceptability outcomes over time, we conducted a series of generalized linear regression models to assess potential correlates after adjustment for the type of test results and time effect (when a baseline measure was available). For example, to assess sex as a correlate of depression at three-weeks follow-up, the three-weeks depression score is regressed on type of test result, sex, a time effect, and the interaction of time and sex. For such models, the interaction term is the parameter of interest. The outcomes included in this analysis were genetic testing decision satisfaction, genetic counseling satisfaction, knowledge, anxiety and depression (both continuous scores and binary classifications reflecting clinical cut-offs), and genetic testing concerns (i.e., MICRA subscales). Potential correlates included sociodemographic and medical characteristics (i.e., sex, race, ethnicity, age, education, cancer type, study site, test results, family history, health status), baseline knowledge, and baseline satisfaction with pre-test education. When no baseline outcome was assessed (e.g., MICRA scores), a single-level model was used with the main effect of the correlate as the parameter of interest. For continuous outcomes, η2 is reported as the measure of standardized effect sizes, while standardized odds ratios (OR) are reported for the binary measures (i.e., clinical anxiety and depression). This strategy of using standardized effect sizes and then probing non-trivial associations, rather than merely relying on p values, reduces the risk of inflated family-wise error rate when investigating a large number of potential moderators.24 For η2 in multiple regression, values of at least 0.02, 0.13, and 0.26 are considered small, medium, and large effect sizes, respectively; for standardized OR, values of at least 1.68 (or less than 0.60) are considered small.25 Findings meeting these thresholds were investigated with stratified analyses. All analyses were conducted in SAS version 9.4.

Results

Patient uptake and characteristics

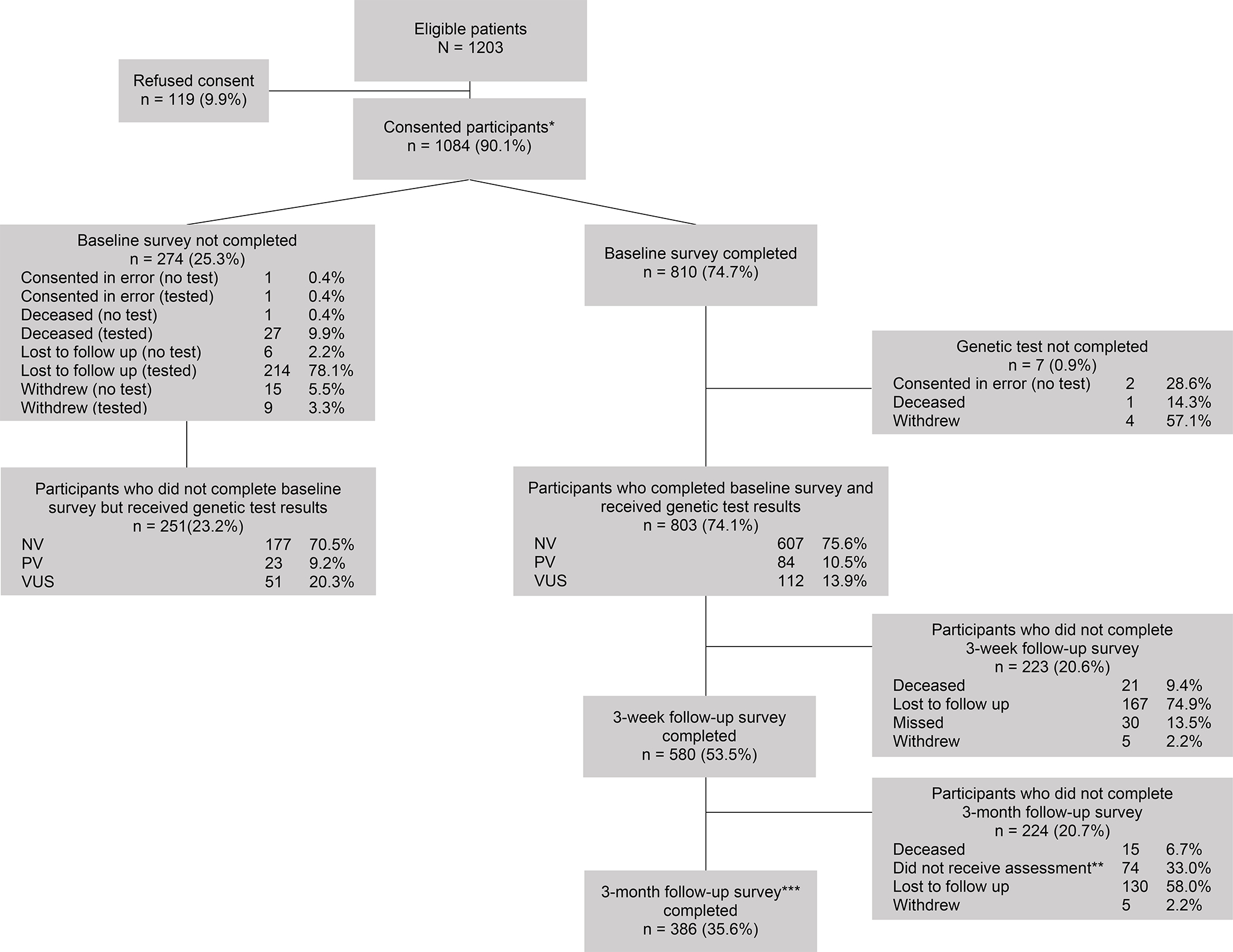

Figure 1 depicts study enrollment and completion. We approached 1203 eligible patients, of whom 1084 (90%) consented. Patients who declined were more likely to be Black/African American (27% refusal rate versus 7% for white patients, Χ2(2)=57, p<0.001; Table 1). Refusal rates also varied by site (3% at MSK versus 13% at University of Pennsylvania, Χ2(1)=30, p<0.001), but not by sex, ethnicity, cancer type, or age. Non-completion of the baseline survey and/or MGPT similarly differed by race and study site, though non-completion also varied by cancer type and age (Table 2). A total of 1054 participants underwent MGPT; testing identified pathogenic germline variants (PV) among 10% of participants, 16% had variants of uncertain significance (VUS), and 74% had no variant identified (NV).

Figure 1.

Study enrollment. PV = pathogenic variant; NV = no variant; VUS = variant of uncertain significance. * Thereafter, all percentages taken from total number of consented patients. ** Due to an administrative error, a subset of participants was not sent invitations to complete the 3-month follow-up survey. *** Total value includes participants who missed the 3-week follow-up survey but completed the 3-month follow-up survey.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients approached for study participation (N = 1203)

| Characteristic | Group | Provided Consent (n = 1084) |

Declined to Consent (n = 119) |

p a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Sex | Female | 342 (91%) | 34 (9%) | 0.51 |

| Male | 742 (90%) | 85 (10%) | ||

| Race | White | 878 (93%) | 67 (7%) | <0.001 |

| Black/African American | 109 (73%) | 40 (27%) | ||

| Asian | 38 (95%) | 2 (5%) | ||

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 1 (50%) | 1 (50%) | ||

| Other | 46 (88%) | 6 (12%) | ||

| Missing | 12 (80%) | 3 (20%) | ||

| Ethnicity | Hispanic | 31 (97%) | 1 (3%) | 0.19 |

| Not Hispanic | 1005 (90%) | 114 (10%) | ||

| Unknown/Missing | 48 (92%) | 4 (8%) | ||

| Cancer Type | Ovarian | 160 (93%) | 12 (7%) | 0.19 |

| Prostate | 507 (89%) | 65 (11%) | ||

| Pancreas | 417 (91%) | 42 (9%) | ||

| Age | Years, Mean (SD) | 67.9 (10.1) | 69.5 (10.3) | 0.11 |

| Study Site | Memorial Sloan Kettering | 406 (97%) | 14 (3%) | <0.001 |

| University of Pennsylvania | 678 (87%) | 105 (13%) | ||

p-values are based on a series of Chi-square tests, except for age which is tested using an independent-samples t-test.

Table 2.

Characteristics of study participants (i.e., analytic sample) versus non-completers (i.e., those who did not complete the baseline survey and/or testing) (N = 1084)

| Characteristic | Group | Analytic Sample (n = 803) |

Non-Completers a (n = 281) |

p b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Sex | Female | 258 (75%) | 84 (25%) | 0.49 |

| Male | 545 (73%) | 197 (27%) | ||

| Race | White | 678 (77%) | 200 (23%) | <0.001 |

| Black/African American | 54 (50%) | 55 (50%) | ||

| Asian | 28 (74%) | 10 (26%) | ||

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 1 (100%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| Other | 35 (76%) | 11 (24%) | ||

| Missing | 7 (58%) | 5 (42%) | ||

| Ethnicity | Hispanic | 23 (74%) | 8 (26%) | 0.92 |

| Not Hispanic | 737 (73%) | 268 (27%) | ||

| Unknown/Missing | 43 (90%) | 5 (10%) | ||

| Cancer Type | Ovarian | 142 (89%) | 18 (11%) | <0.001 |

| Prostate | 390 (77%) | 117 (23%) | ||

| Pancreas | 271 (65%) | 146 (35%) | ||

| Type of Result | PV | 84 (79%) | 23 (22%) | 0.05 |

| NV | 607 (77%) | 177 (23%) | ||

| VUS | 112 (69%) | 51 (31%) | ||

| Missing | 0 (0%) | 30 (100%) | ||

| Site | Memorial Sloan Kettering | 376 (93%) | 30 (7%) | <0.001 |

| University of Pennsylvania | 427 (63%) | 251 (37%) | ||

| Age | Years, Mean (SD) | 67.1 (9.9) | 70.2 (10.4) | <0.001 |

PV = pathogenic variant; NV = no variant; VUS = variant of uncertain significance.

The majority of study non-completers (89.3%) completed genetic testing but not the baseline survey (see Figure 1. for details).

p-values are based on a series of Chi-square tests, except for age which is tested using an independent-samples t-test.

Overall, 803 participants consented, completed a baseline survey, and received MGPT results, thus comprising the analytic sample for acceptability outcomes. As shown in Table 3, participants (ages 30–94) were primarily male (68%), white (84%), non-Hispanic (92%), and had a college degree (64%). Study sites contributed roughly similar numbers of participants, although all ovarian patients came from MSK and nearly all (92%) pancreas patients came from University of Pennsylvania. On average, participants reported that 13% of their first- or second-degree relatives had a cancer history. Participants with a stronger family history were more likely to have PV and less likely to have VUS (F(2, 735)=4.5, p=0.01).

Table 3.

Baseline sociodemographic and medical characteristics and patient acceptability of the mainstreaming model, by type of test result

| Characteristic | Group | All (n = 803) | PV (n = 84) | NV (n = 607) | VUS (n = 112) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Sex | Female | 258 (32%) | 28 (33%) | 195 (32%) | 35 (31%) | 0.95 |

| Male | 545 (68%) | 56 (67%) | 412 (68%) | 77 (69%) | ||

| Age, Years, M (SD) | 67.1 (9.9) | 65.4 (9.3) | 67.3 (10.0) | 67.5 (9.8) | 0.23 | |

| Race | White | 678 (84%) | 74 (88%) | 518 (85%) | 86 (77%) | 0.34 |

| Black/African American | 54 (7%) | 5 (6%) | 36 (6%) | 13 (12%) | ||

| Asian | 28 (3%) | 1 (1%) | 21 (3%) | 6 (5%) | ||

| Other | 36 (4%) | 4 (5%) | 26 (4%) | 6 (5%) | ||

| Missing | 7 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 6 (1%) | 1 (1%) | ||

| Ethnicity | Hispanic | 23 (3%) | 5 (6%) | 17 (3%) | 1 (1%) | 0.12 |

| Not Hispanic | 737 (92%) | 77 (92%) | 552 (91%) | 108 (96%) | ||

| Missing | 43 (5%) | 2 (2%) | 38 (6%) | 3 (3%) | ||

| Education | High school or less | 123 (15%) | 13 (15%) | 93 (15%) | 17 (15%) | 0.87 |

| Post-secondary | 152 (19%) | 15 (18%) | 119 (20%) | 18 (16%) | ||

| College graduate | 249 (31%) | 26 (31%) | 189 (31%) | 34 (30%) | ||

| Post-graduate | 266 (33%) | 28 (33%) | 198 (33%) | 40 (36%) | ||

| Missing | 13 (2%) | 2 (2%) | 8 (1%) | 3 (3%) | ||

| Family Cancer History, Proportion, M (SD) | 0.13 (0.1) | 0.17 (0.1) | 0.13 (0.1) | 0.12 (0.1) | 0.01 | |

| Cancer Type | Ovarian | 142 (18%) | 15 (18%) | 113 (19%) | 14 (13%) | 0.49 |

| Prostate | 390 (49%) | 44 (52%) | 291 (48%) | 55 (49%) | ||

| Pancreas | 271 (34%) | 25 (30%) | 203 (33%) | 43 (38%) | ||

| Self-reported Health | Completely disabled | 3 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (0%) | 1 (1%) | 0.47 |

| Status (ECOG) | Limited selfcare | 26 (3%) | 3 (4%) | 20 (3%) | 3 (3%) | |

| Unable to work | 72 (9%) | 8 (10%) | 51 (8%) | 13 (12%) | ||

| Light work | 316 (39%) | 27 (32%) | 243 (40%) | 46 (41%) | ||

| Fully active | 372 (46%) | 44 (52%) | 281 (46%) | 47 (42%) | ||

| Missing | 14 (2%) | 2 (2%) | 10 (2%) | 2 (2%) | ||

| Study Site | Memorial Sloan Kettering | 376 (47%) | 46 (55%) | 281 (46%) | 49 (44%) | 0.27 |

| University of Pennsylvania | 427 (53%) | 38 (45%) | 326 (54%) | 63 (56%) | ||

| Gene b | BRCA1/2 | 59 (7%) | 40 (48%) | -- | 19 (17%) | -- |

| ATM | 30 (4%) | 9 (11%) | -- | 21 (19%) | ||

| CHEK2 | 24 (3%) | 13 (15%) | -- | 11 (10%) | ||

| Lynch syndrome (EPCAM, MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2) | 42 (5%) | 9 (11%) | -- | 33 (29%) | ||

| Other | 58 (7%) | 13 (15%) | -- | 45 (40%) | ||

| Satisfaction with Pre-test Education, M (SD) | 15.43 (2.1) | 15.99 (2.0) | 15.32 (2.1) | 15.65 (2.1) | 0.03 | |

| Genetic Testing Decision Satisfaction, M (SD) | 16.89 (2.9) | 16.83 (3.1) | 16.89 (2.9) | 16.89 (2.9) | 0.98 | |

| HADS-Anxiety, M (SD) | 5.45 (3.8) | 4.96 (3.6) | 5.62 (3.8) | 4.92 (4.1) | 0.10 | |

| Meets Clinical Criteria (score ≥ 8) | 213 (27%) | 20 (24%) | 168 (28%) | 25 (23%) | 0.44 | |

| HADS-Depression, M (SD) | 3.98 (3.5) | 3.22 (3.3) | 4.07 (3.6) | 4.08 (3.5) | 0.11 | |

| Meets Clinical Criteria (score ≥ 8) | 137 (17%) | 11 (13%) | 110 (18%) | 16 (14%) | 0.37 | |

| Knowledge about Genetic Testing, M (SD) | 0.56 (0.2) | 0.58 (0.2) | 0.55 (0.2) | 0.61 (0.2) | 0.03 | |

PV = pathogenic variant; NV = no variant; VUS = variant of uncertain significance; ECOG = Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; HADS = Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale.

p-values are based on Chi-square tests for categorical variables or ANOVAs for continuous variables.

See text for a full list of genes included in the multigene panel testing.

Initial acceptability of the mainstreaming model

Baseline survey data suggested a relatively high degree of initial acceptability of the mainstreaming model (Table 3). On average, participants reported high satisfaction with the pre-test education (M±SD=15.4±2.1, 4–20 scale). Participants were also generally satisfied with their decision to undergo testing (16.9±2.9, 4–20 scale). Anxiety and depression (5.5±3.8 and 4.0±3.5, respectively, 0–21 scales) were low, although 27% and 17% of participants met clinical criteria, respectively. At baseline assessment (i.e., following review of the pre-test educational materials), knowledge about genetic testing was incomplete, with participants correctly answering 56% of these questions on average, and responding “don’t know” to an average of 29% of the knowledge questions.

Longitudinal changes in acceptability

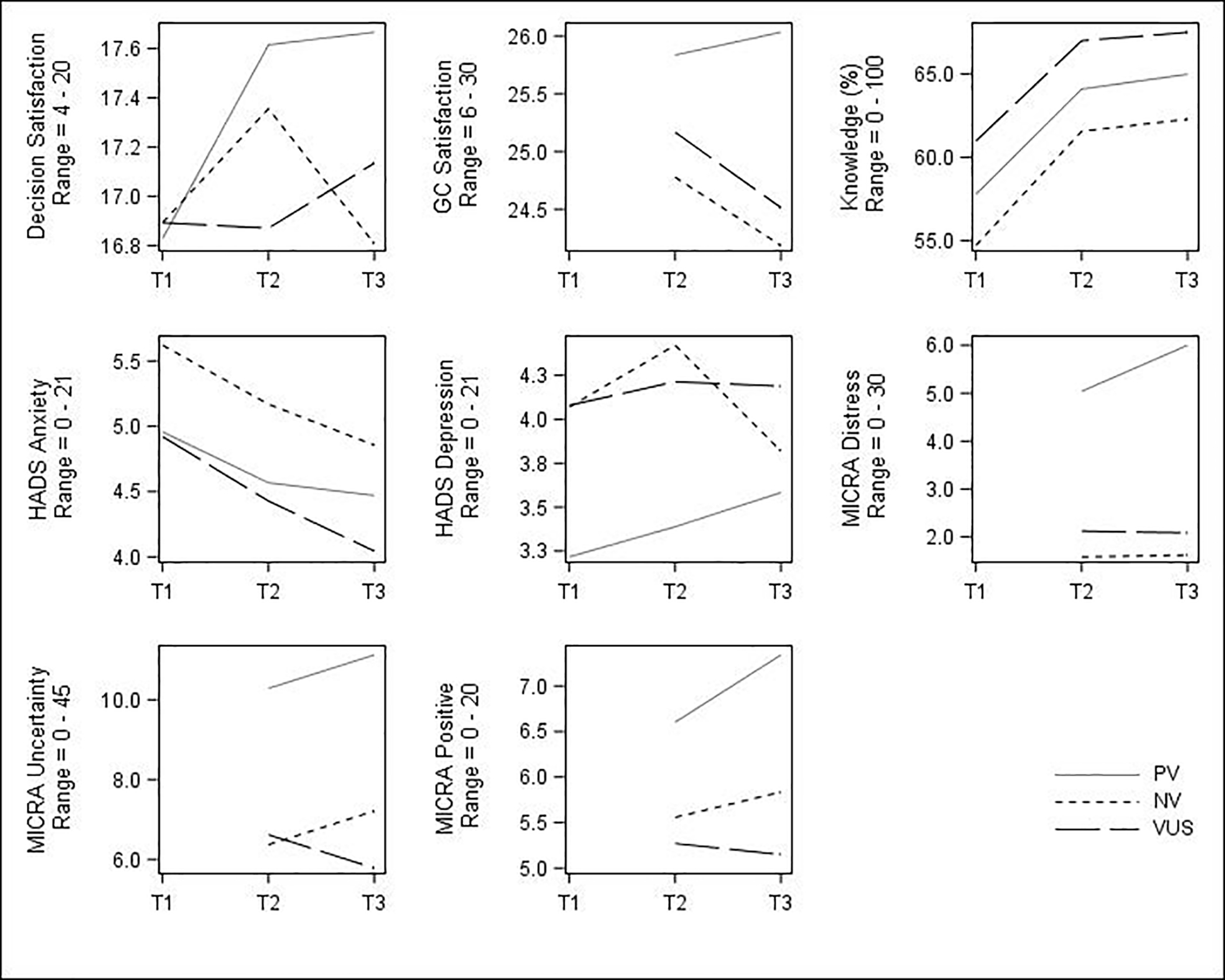

Changes in acceptability outcomes, by test result group, appear in Figure 2. Overall, genetic testing decision satisfaction increased over time (months) in a quadratic fashion (βTime=0.94, pTime=0.01; βTime2= −0.31, pTime2=0.008), though this effect was driven by a constant increase from baseline to three-months for the PV group and a temporary increase for the NV group at three-weeks. Change in genetic counseling satisfaction did not significantly vary by result type, although the PV group appeared to increase whereas the others decreased. Knowledge increased from baseline to three-weeks for all groups and then remained near this level at three-months (βTime=0.11, pTime<0.001; βTime2= −0.03, pTime2<0.001). Anxiety decreased over time (βTime= −0.12, p=0.004). Depression showed a slight, non-linear increase (βTime=1.10, pTime<0.001; βTime2= −0.33, pTime2<0.001), though the increase for NV participants was only temporary and then reduced below baseline. Although rates of clinically significant anxiety and depression over time appeared to vary by test result, these effects were not statistically significant (see Supplemental Figure 1). None of the MICRA subscales showed significant overall changes between three-weeks and three-months, although those with PV experienced a significant increase in distress (βTime=0.73, p=0.03).

Figure 2.

Changes in patient acceptability of the mainstreaming model over time among participants with different MGPT results. T1 = baseline; T2 = 3-week follow-up; T3 = 3-month follow-up; GC = genetic counseling; HADS = Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; MICRA = Multidimensional Impact of Cancer Risk Assessment; PV = pathogenic variant; NV = no variant; VUS = variant of uncertain significance. GC Satisfaction and MICRA subscales were only assessed at T2 and T3. Significant (p<0.05) non-linear trends observed for genetic testing decision satisfaction, knowledge, and HADS-Depression; significant (p<0.05) linear trends observed for HADS-Anxiety and MICRA-Distress; see text for details.

Exploring correlates of acceptability over time

Result type, sex, and cancer type each had small associations with MICRA-Uncertainty scores at three-weeks, though not at three-months. Specifically, participants with PV had an average of 3.88 points higher MICRA-Uncertainty scores compared to participants with either VUS or NV results (η2=0.03, p<0.01). A small effect (η2=0.03, p<0.01) was found for sex and MICRA-Uncertainty; at three-weeks, females exhibited higher uncertainty than males if they received either PV (mean difference=3.95) or NV (mean difference=2.44), though males with VUS exhibited slightly higher uncertainty than their female counterparts (mean difference=0.68). Since sex and cancer type are not independent in this sample, we assessed whether a sex effect persisted in the pancreatic cancer subsample (which included both sexes); a similar pattern was exhibited.

Result type (standardized OR VUS versus NV=0.48, standardized OR PV versus NV=0.47, overall p=0.24), sex (standardized OR female versus male=1.81, p=0.02), and cancer type (standardized OR ovarian versus prostate=1.92, overall p=0.07) produced findings that met the threshold for small standardized effects, suggesting associations with a change in clinically significant depression at three-weeks, but not at three-months. Although cell sizes were small, among those with who were clinically depressed at baseline, 73% of participants with NV were still depressed at three-weeks, compared to63% of participants with PV and67% of participants with VUS. Among those participants who were not clinically depressed at baseline, males and females had similar rates of clinical depression at three-weeks if they received either PV or NV, but males had higher incident depression (11%) than females (5%) if they had VUS. The association for cancer type was not driven by this sex effect, as among those without baseline clinical depression, for those with both NV and VUS the rate of incident depression for participants with pancreatic cancer was not within the bounds of the rates for ovarian or prostate cancer. For those with NV, incident depression in the pancreatic cancer group was 11%, compared to 6% for those with ovarian cancer and 8% for those with prostate cancer. For participants with VUS, incident depression among those with pancreatic cancer was 5%, compared to 10% for those with ovarian cancer and 11% for those with prostate cancer.

Further, result type was associated with MICRA-Distress at three-weeks: Participants with PV had a mean MICRA-Distress score of 5.04, compared to 1.59 and 2.12 for those with NV and VUS, respectively (η2=0.07, p<0.01). Satisfaction with pre-test education was moderately associated with genetic counseling satisfaction at three-weeks (η2=0.09, p<0.01), with a comparable positive correlation regardless of test result.

Discussion

We implemented a MGPT mainstreaming model involving standardized pre-test education and test ordering by oncologists paired with telephone-based result disclosure and post-test counseling by genetic counselors. Among a large sample of patients with ovarian, pancreatic, and prostate cancers, study uptake was high; only 10% of invited patients declined participation, and 97% of those who consented underwent MGPT through the mainstreaming model. Refusal rates did not differ based on sex, cancer diagnosis, or age. However, Black/African American patients were less likely to consent and to complete the baseline survey and/or MGPT. Racial disparities including unmet needs for discussing genetic testing with providers26,27 and lower use of genetic testing27,28 are well documented, and additional efforts must be undertaken to identify appropriate strategies for addressing barriers encountered by these individuals.

We evaluated self-reported acceptability of the mainstreaming model, including satisfaction, anxiety, depression, genetic testing concerns, and knowledge. We also examined changes in these outcomes over time for participants with different test results, and explored how patient characteristics, baseline knowledge, and satisfaction with the pre-test education may be associated with acceptability. Overall, participants reported high satisfaction with the pre-test education consisting of a video and brochure. Participants’ genetic testing decision satisfaction was also high, with our sample reporting mean values in the top quartile of this scale. Longitudinal analyses indicated that genetic testing decision satisfaction increased over time, driven primarily by a sustained increase among patients with PV and a temporary increase among patients with NV. The potential utility of PV to patients’ therapeutic management may explain these findings, although this should be further explored. In addition, levels of genetic counseling satisfaction were also high and remained stable over time for participants regardless of results. Participants who were more satisfied with the pre-test education also reported higher genetic counseling satisfaction shortly after receipt of their results. No other patient characteristics were associated with decision or counseling satisfaction at the follow-up timepoints, indicating similar levels of satisfaction across patient sociodemographic and medical characteristics.

Anxiety and depression levels were low, on average, among participants. Further, anxiety levels significantly decreased over time for all study participants regardless of result. For those with NV, depression peaked (albeit at a low average magnitude) at three-weeks, but diminished below pre-testing levels by three-months. We also observed that the overall proportion of participants meeting clinical criteria for anxiety and depression did not vary by time and test result. However, the likelihood of a participant developing incident clinical depression at the three-week follow-up was associated with their sex; while not statistically significant, analyses also suggest possible trends in the resolution and development of clinical depression based on result type and cancer diagnosis, respectively. The pattern of these results includes men with VUS being more likely to develop clinical depression, as were patients with pancreatic cancer who had NV. Additionally, patients with pancreatic cancer who had VUS were less likely to develop depression than patients with the other cancer diagnoses who received similar results. Explanations for these findings are not clear, and it is important to acknowledge the exploratory nature of these analyses as well as the various unmeasured factors (e.g., cancer progression, ongoing treatment side effects) that may contribute to patients’ experiences of depression. Nonetheless, it is possible that a lack of actionable germline variants for informing treatment for those with NV may explain trends toward greater depression in these individuals. Past work demonstrates that patients have high expectations for sequencing to provide additional treatment options,29,30 yet less is known about how patients respond when these hopes are not realized. Patients with pancreatic cancer, who face particularly poor prognoses and have more negative psychological outcomes than those with other cancers,31 may be particularly vulnerable to disappointment (e.g., in response to a NV) or sustained hope (e.g., in response to a VUS). Such possibilities, and optimal strategies for supporting patients who are facing these challenges, are worthy of future investigation.

Little variability over time in genetic testing concerns was observed, although participants with PV had greater distress at three-weeks than those with VUS or NV, and had a significant increase in distress from three-weeks to three-months. Small, short-term increases in distress have often been reported among patients with PV.17,32–35 In addition, those with PV had greater uncertainty than those with VUS or NV at three-weeks. This observation of higher MICRA-Uncertainty scores among patients with PV, reflecting greater uncertainty and concerns regarding cancer risk and the behavioral and interpersonal implications of these test results, is consistent with other studies that utilized this measure.34–37 Interestingly, males with VUS also experienced slightly more uncertainty than females at this timepoint. Psychological experiences of men following receipt of MGPT17 or VUS38 are understudied.

Finally, knowledge about genetic testing among participants following pre-test education was incomplete. Although scores reflecting correct knowledge were moderate at baseline, participants responded “don’t know” to an average of 29% of the items comprising this measure, indicating a lack of specific knowledge rather than inaccurate knowledge. Knowledge scores increased significantly for participants with all types of results following post-test counseling and were sustained over time. Baseline knowledge was also unrelated to any subsequent measures of patient acceptability. These findings demonstrate room for improvement in the clarity, content, or delivery of our educational materials. However, they also suggest that this suboptimal baseline knowledge did not lead to adverse patient outcomes, likely due to the in-depth post-test counseling provided to all participants. These findings also highlight important theoretical questions about the decision-making experiences of patients in such a mainstreaming model. Namely, whether an informed decision-making process has occurred when patient recall of factual information is limited, and whether the presence of positive decision outcomes (e.g., satisfaction) may be sufficient for demonstrating that the decision-making experience was good. While such questions remain to be answered, strategies to streamline the provision of genetic services should acknowledge and integrate the critical role of genetic counseling in accurately and clearly conveying genetic risk information to patients.

This study has strengths as well as limitations. Contrary to past studies, the sample was large and diverse in cancer diagnoses and sex, thereby increasing generalizability of these findings. However, participants were predominantly non-Hispanic and white, only recruited from two sites in the Northeastern US, levels of refusal and completion varied across sites, and there was high attrition across assessments. Although we prospectively evaluated outcomes of our mainstreaming model over time using multiple validated measures, we cannot make direct comparisons to outcomes that may have been obtained via the traditional HCGT model. Future research using a randomized design, coupled with economic analyses, would provide stronger evidence regarding the utility of this MGPT mainstreaming model. Similarly, future research should directly explore the perspectives of oncologists and genetic counselors to obtain complementary insight into the acceptability of this model. In addition, this study did not plan for a fully powered moderator analysis to examine correlates of acceptability outcomes, and thus we have reported and draw conclusions upon standardized effect sizes.24 Caution should be used when relying on standardized effect sizes for more than generating hypotheses for confirmation in future work.

While future work needs to determine if this model performs similarly for unaffected patients, a distinctive feature of this study was our focus on cancer patients for whom the pre-test decision is less preference-sensitive given its treatment implications,39 and whose openness to testing and subsequent satisfaction may be influenced by the potential access to additional therapeutic options. Opportunities exist for utilizing such a mainstreaming model among cancer patients as a catalyst for “cascade” testing of at-risk relatives, which would have a substantial impact on the rate of detection of all individuals with cancer-predisposing PV in the US population.40 Additionally, the increasing use of telegenetics involving videoconferencing5 may be integrated into this model. Yet, efforts to further develop and evaluate this and related cancer genetics mainstreaming models must also be responsive to the needs of racially, ethnically, and culturally diverse patients to ensure that existing health disparities in this domain are not further exacerbated.

In conclusion, we evaluated a novel mainstreaming model for delivering MGPT to patients with ovarian, pancreatic, and prostate cancers. We observed high uptake and promising indicators of short-term patient acceptability, including high decision and genetic counseling satisfaction and limited anxiety and genetic testing concerns. Further, we identified several novel subgroups, including men and those with pancreatic cancer whose germline MGPT results are unlikely to inform treatment, who may benefit from additional support. Together, these findings highlight the potential value and future research directions for applying a mainstreaming model to extend access to germline genetic information.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the MSK Survivorship, Outcomes, and Risk Developmental Funds Award (J.G.H., M.E.R.), Breast Cancer Research Foundation (S.M.D., M.E.R., K.O.), Basser Center for BRCA (S.M.D.), Prostate Cancer Foundation (M.I.C.), NCI P30 CA008748, NCI 5-P30-CA-016520–38, the Gray Foundation, and The Robert and Kate Niehaus Center for Inherited Cancer Genomics. J.G.H. was also supported by a Mentored Research Scholar Grants in Applied and Clinical Research, MRSG-16–020-01-CPPB, from the American Cancer Society. We are extremely grateful to all participating patients.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Notification

Disclosure: The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Ethics Declaration

This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Boards (IRB) of both participating sites (Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center and the University of Pennsylvania). Informed consent was obtained from all study participants as required by the IRB.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

- 1.Yap TA, Plummer R, Azad NS, Helleday T. The DNA damaging revolution: PARP inhibitors and beyond. American Society of Clinical Oncology Educational Book. 2019(39):185–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCuaig JM, Armel SR, Care M, Volenik A, Kim RH, Metcalfe KA. Next-generation service delivery: A scoping review of patient outcomes associated with alternative models of genetic counseling and genetic testing for hereditary cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2018;10(11). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buchanan AH, Rahm AK, Williams JL. Alternate service delivery models in cancer genetic counseling: A mini-review. Front Oncol. 2016;6:120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cohen SA, Huziak RC, Gustafson S, Grubs RE. Analysis of advantages, limitations, and barriers of genetic counseling service delivery models. J Genet Couns. 2016;25(5):1010–1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Greenberg SE, Boothe E, Delaney CL, Noss R, Cohen SA. Genetic counseling service delivery models in the United States: Assessment of changes in use from 2010 to 2017. J Genet Couns. 2020;29(6):1126–1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schwartz MD, Valdimarsdottir HB, Peshkin BN, et al. Randomized noninferiority trial of telephone versus in-person genetic counseling for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(7):618–626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kinney AY, Butler KM, Schwartz MD, et al. Expanding access to BRCA1/2 genetic counseling with telephone delivery: A cluster randomized trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106(12). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bradbury AR, Patrick-Miller LJ, Egleston BL, et al. Randomized noninferiority trial of telephone vs in-person disclosure of germline cancer genetic test results. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2018;110(9):985–993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wright S, Porteous M, Stirling D, et al. Patients’ views of treatment-focused genetic testing (TFGT): Some lessons for the mainstreaming of BRCA1 and BRCA2 testing. J Genet Couns. 2018;27(6):1459–1472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.George A, Riddell D, Seal S, et al. Implementing rapid, robust, cost-effective, patient-centred, routine genetic testing in ovarian cancer patients. Sci Rep. 2016;6:29506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Colombo N, Huang G, Scambia G, et al. Evaluation of a streamlined oncologist-led BRCA mutation testing and counseling model for patients with ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(13):1300–1307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoberg-Vetti H, Bjorvatn C, Fiane BE, et al. BRCA1/2 testing in newly diagnosed breast and ovarian cancer patients without prior genetic counselling: The DNA-BONus study. Eur J Hum Genet. 2015;24(6):881–888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McLeavy L, Rahman B, Kristeleit R, et al. Mainstreamed genetic testing in ovarian cancer: Patient experience of the testing process. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2019;30(2):221–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scheinberg T, Young A, Woo H, Goodwin A, Mahon KL, Horvath LG. Mainstream consent programs for genetic counseling in cancer patients: A systematic review. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Quinn VF, Meiser B, Kirk J, et al. Streamlined genetic education is effective in preparing women newly diagnosed with breast cancer for decision making about treatment-focused genetic testing: A randomized controlled noninferiority trial. Genet Med. 2017;19(4):448–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Robson ME, Bradbury AR, Arun B, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology policy statement update: Genetic and genomic testing for cancer susceptibility. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(31):3660–3667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hamilton JG, Robson ME. Psychosocial effects of multigene panel testing in the context of cancer genomics. Hastings Cent Rep. 2019;49 Suppl 1:S44–S52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scheinberg T, Goodwin A, Ip E, et al. Evaluation of a mainstream model of genetic testing for men with prostate cancer. JCO Oncology Practice. 2021;17(2):e204–e216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oken MM, Creech RH, Tormey DC, et al. Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Am J Clin Oncol. 1982;5(6):649–656. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holmes-Rovner M, Kroll J, Schmitt N, et al. Patient satisfaction with health care decisions: The Satisfaction with Decision scale. Med Decis Making. 1996;16(1):58–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.DeMarco TA, Peshkin BN, Mars BD, Tercyak KP. Patient satisfaction with cancer genetic counseling: A psychometric analysis of the Genetic Counseling Satisfaction Scale. J Genet Couns. 2004;13(4):293–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67(6):361–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cella D, Hughes C, Peterman A, et al. A brief assessment of concerns associated with genetic testing for cancer: The Multidimensional Impact of Cancer Risk Assessment (MICRA) questionnaire. Health Psychol. 2002;21(6):564–572. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garamszegi LZ. Comparing effect sizes across variables: Generalization without the need for Bonferroni correction. Behav Ecol. 2006;17(4):682–687. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen H, Cohen P, Chen S. How big is a big odds ratio? Interpreting the magnitudes of odds ratios in epidemiological studies. Commun Stat - Simul. 2010;39(4):860–864. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jagsi R, Griffith KA, Kurian AW, et al. Concerns about cancer risk and experiences with genetic testing in a diverse population of patients with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(14):1584–1591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cragun D, Weidner A, Lewis C, et al. Racial disparities in BRCA testing and cancer risk management across a population-based sample of young breast cancer survivors. Cancer. 2017;123(13):2497–2505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nikolaidis C, Duquette D, Mendelsohn-Victor KE, et al. Disparities in genetic services utilization in a random sample of young breast cancer survivors. Genet Med. 2018;21(6):1363–1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rohrmoser A, Pichler T, Letsch A, et al. Cancer patients’ expectations when undergoing extensive molecular diagnostics-A qualitative study. Psychooncology. 2020;29(2):423–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roberts JS, Gornick MC, Le LQ, et al. Next-generation sequencing in precision oncology: Patient understanding and expectations. Cancer Med. 2019;8(1):227–237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bauer MR, Bright EE, MacDonald JJ, Cleary EH, Hines OJ, Stanton AL. Quality of life in patients with pancreatic cancer and their caregivers: A systematic review. Pancreas. 2018;47(4):368–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hamilton JG, Lobel M, Moyer A. Emotional distress following genetic testing for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer: A meta-analytic review. Health Psychol. 2009;28(4):510–518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vansenne F, Bossuyt PM, de Borgie CA. Evaluating the psychological effects of genetic testing in symptomatic patients: A systematic review. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers. 2009;13(5):555–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Culver JO, Ricker CN, Bonner J, et al. Psychosocial outcomes following germline multigene panel testing in an ethnically and economically diverse cohort of patients. Cancer. 2021;127(8):1275–1285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Idos GE, Kurian AW, Ricker C, et al. Multicenter prospective cohort study of the diagnostic yield and patient experience of multiplex gene panel testing for hereditary cancer risk. JCO Precision Oncology. 2019(3):1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Peters MLB, Stobie L, Dudley B, et al. Family communication and patient distress after germline genetic testing in individuals with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer. 2019;125(14):2488–2496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mighton C, Shickh S, Uleryk E, Pechlivanoglou P, Bombard Y. Clinical and psychological outcomes of receiving a variant of uncertain significance from multigene panel testing or genomic sequencing: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Genet Med. 2021;23(1):22–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Medendorp NM, van Maarschalkerweerd PEA, Murugesu L, Daams JG, Smets EMA, Hillen MA. The impact of communicating uncertain test results in cancer genetic counseling: A systematic mixed studies review. Patient Educ Couns. 2020;103(9):1692–1708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schupmann W, Jamal L, Berkman BE. Re-examining the ethics of genetic counselling in the genomic era. J Bioeth Inq. 2020;17(3):325–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Offit K, Tkachuk KA, Stadler ZK, et al. Cascading after peridiagnostic cancer genetic testing: An alternative to population-based screening. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(13):1398–1408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.