Abstract

Drug delivery research pursues many types of carriers including proteins and other macromolecules, natural and synthetic polymeric structures, nanocarriers of diverse compositions and cells. In particular, liposomes and lipid nanoparticles represent arguably the most advanced and popular human-made nanocarriers, already in multiple clinical applications. On the other hand, red blood cells (RBCs) represent attractive natural carriers for the vascular route, featuring at least two distinct compartments for loading pharmacological cargoes, namely inner space enclosed by the plasma membrane and the outer surface of this membrane. Historically, studies of liposomal drug delivery systems (DDS) astronomically outnumbered and surpassed the RBC-based DDS. Nevertheless, these two types of carriers have different profile of advantages and disadvantages. Recent studies showed that RBC-based drug carriers indeed may feature unique pharmacokinetic and biodistribution characteristics favorably changing benefit/risk ratio of some cargo agents. Furthermore, RBC carriage cardinally alters behavior and effect of nanocarriers in the bloodstream, so called RBC hitchhiking (RBC-HH). This article represents an attempt for the comparative analysis of liposomal vs RBC drug delivery, culminating with design of hybrid DDSs enabling mutual collaborative advantages such as RBC-HH and camouflaging nanoparticles by RBC membrane. Finally, we discuss the key current challenges faced by these and other RBC-based DDSs including the issue of potential unintended and adverse effect and contingency measures to ameliorate this and other concerns.

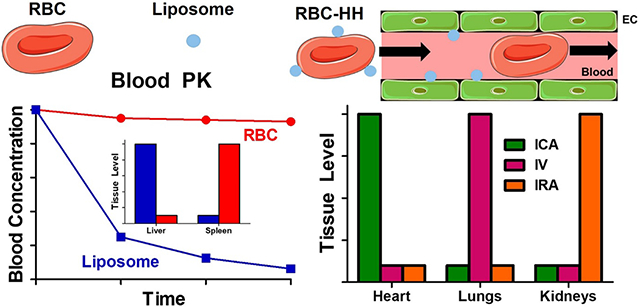

Visual Abstarct

Section 1. Introduction. RBC and liposomes: a historical overview.

Mephistopheles, seeking Dr. Faust’s signature on the devil’s contract, coined an aphorism “Blood is a juice of a very special kind,” which could characterize today’s field of hematology. Indeed, the mysterious ever-changing liquid is enormously important and complex. Take, for example, the ubiquitous corpuscles that paint blood red. Their narrative speaks of a dualism of many sorts including changing their very color from crimson in arteries to purple in veins.

Two individuals discovered erythrocytes independently. In 1658, Jan Swammerdam, a Dutch biologist, described miniature corpuscles in frog blood. In 1674, erythrocytes were redescribed by his famous compatriot, inventor of advanced microscopes and amateur-scientist Antonie van Leeuwenhoek. Royalties paid visits to him in the city of Delft to honor his discoveries. During a European tour in 1698, Peter the Great met Leeuwenhoek, who presented to the young Russian Emperor an optical device to observe blood in the capillaries.

Both the Latin and English terms, erythrocytes and red blood cells (RBCs) are misnomers, as RBCs are not complete cells. Cells, especially blood cells – leukocytes, lymphocytes, monocytes and even cell remnants platelets, are more complex structurally and functionally, diverse and heterogenous, delicate and capricious, reactive and dangerous than RBCs. Remnants of reticulocytes, RBCs lack nuclei and organelles, and are in essence membrane vesicles filled with hemoglobin. Yet, of course these refined biconcave discs are not that simple.

Indeed, in the three centuries that ensued since their discovery, RBCs have become the subject of many revelations. Accolades for RBC studies include Nobel Prizes to Ronald Ross for studies of the pathogenesis of malaria (1902), Jules Bordet for the discovery of the complement system (1919), Karl Landsteiner for the discovery of blood groups that enabled blood transfusion (1930), George H. Whipple for studies of anemia (1934), Max Perutz for studies of hemoglobin (1959), Peter Agre and Roderick McKinnon for discovery of aquaporins in RBC membranes (2003), Tu Youyou for new therapy against malaria (2015), and William Kaelin, Peter Ratcliffe, and Gregg Semenza for studies of biomedical features of oxygen and erythropoietin (2019).

RBCs are abundant, docile, and incredibly stable. As a blood transporting agent, these features lend themselves to carry drugs. Indeed, ideas to encapsulate pharmacological agents into isolated RBC to prolong circulation evolved nearly half a century ago [1, 2]. Alas, soon after these promising initial studies, the pandemics of HIV, hepatitis, and other infections transmitted with blood products all but decimated RBC-based drug delivery research for several decades.

Liposomes, artificial multimolecular assemblies made of phospholipids, cholesterol and other components, which form membranous structures with sizes ranging from <100 nm to ~500 nm, were discovered, or rather, invented in the early 1960s in Cambridge by Alec D. Bangham [3–5]. Curiously, he was a hematologist studying blood coagulation. Liposomes initially attracted the attention of basic researchers as models of biological membranes. This aspect remains an important area of liposome research. However, within a decade of their discovery, liposomes became a cornerstone in drug delivery research, giving rise to multiple formulations of synthetic nanocarriers. These advanced means for delivery of drugs in the body have yet to be the focus of a coveted Nobel Prize (which actually might happen in a few months this year, taking into account the global impact of BioNTech/Pfizer and Moderna COVID19 vaccine designed by the team led by Drew Weissman and Kati Kariko, based on modified mRNA packed into lipid nanoparticles).

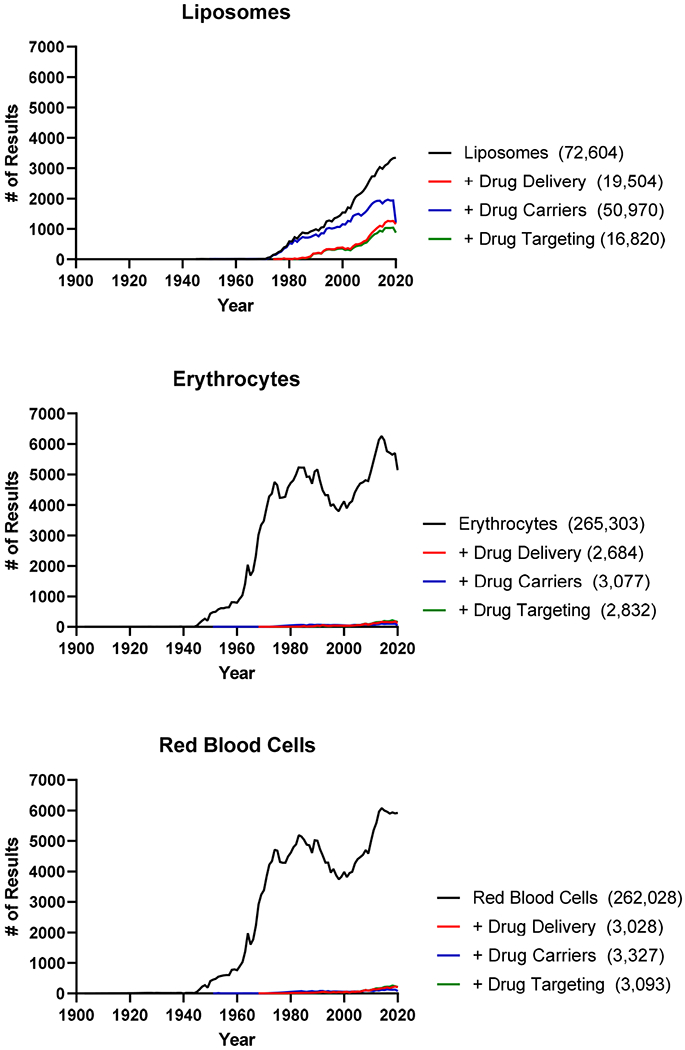

Today, the internet search terms “erythrocyte” and “RBC” yield several orders of magnitude more hits than “liposome”, reflecting the relative biomedical significance of these subjects studied for three centuries vs. half of a century, respectively (Table 1). However, a similar search on drug delivery, carriers, and targeting yields more hits for liposomes than erythrocytes and RBC combined. This is especially obvious in scientific databases such as PubMed: a search for liposome in the context of drug delivery and targeting yields about an order of magnitude more hits than a search for erythrocyte and two orders of magnitude more hits than a search for RBC (Figure 1). Furthermore, the liposome search hits deal with drug delivery, whereas most of the RBC and erythrocyte hits are irrelevant.

Table 1.

Liposomes and RBC/erythrocytes: history and citations.

| Category | Parameters | Liposomes | RBC |

|---|---|---|---|

| General search | Internet (Google) | 18 million | Erythrocytes: ~18 million |

| Red blood cells: ~435 million | |||

| PubMed | 70,000 | Erythrocytes: ~250,000 | |

| RBC: ~250,000 | |||

| Drug delivery | Internet (Google) | 3.8 million | Erythrocytes: 1.5 million |

| RBC: 2.7 million | |||

| PubMed | 18,300 | Erythrocytes: 2,500 | |

| RBC: 520 | |||

| Drug carriers | Internet (Google) | 7.6 million | Erythrocytes: 1.5 million |

| RBC: 5.4 million | |||

| PubMed | 47,800 | Erythrocytes: 2,800 | |

| RBC: 360 | |||

| Drug targeting | Internet (Google) | 14.9 million | Erythrocytes: 3.5 million |

| RBC: 5.4 million | |||

| PubMed | 15,700 | Erythrocytes: 2,600 | |

| RBC: 390 |

Figure 1.

Number of publications returned annually from 1903-2020 via a PubMed search for liposomes, erythrocytes, and red blood cells.

Section 2. Translational aspects of artificial and natural carriers.

Since the mid-20th century, scores of researchers have worked on liposomes and other artificial carriers for drug delivery and targeting. These synthetic drug delivery systems (DDS) are amenable to controlled synthesis, purification, and characterization at the molecular and atomic levels, allowing rational and modular design, theoretical analysis and modeling, reiterative re-engineering, and modifications yielding structural and functional diversity of versatile pharmaceutical formulations. Artificial DDSs seem to have features that help meet challenges of industrial translation (stability, scaling up), commercialization and medical use (storage, distribution, dosing, timing, regulatory affairs).

Infusion of natural carriers, such as RBCs, has been used in clinical practice for centuries, dating back to the first xenotransfusion of sheep blood into humans by Richard Lower and Edmund King in 1667. The success of blood transfusions was dramatically increased by Landsteiner’s discovery of the main blood groups in the early 20th century. It is, in part, the presence of blood groups and unwanted immune responses against incompatible blood types, that limits ‘off-the-shelf’ applications of cell-based DDSs in clinical medicine. As a result, the use of RBCs as a DDS is currently limited to individualized therapy, wherein autologous, ex vivo-modified RBCs are reinfused into patients. This has limited the development of natural carriers for drug delivery applications and has made the ability to directly load circulating RBCs in vivo a critical direction of research for the field.

The roster of artificial carriers for drug delivery encompasses a multitude of classes and types of compounds including linear and branched polymers, polymersomes, and diverse micelles formed by amphiphilic di-block co-polymers, nanogels, lipid nanoparticles (LNP), dendrimers, protein conjugates, fusions, and multimolecular assemblies, etc. It seems safe to proclaim; however, that liposomes represent arguably one of the most studied and clinically relevant DDS. In many cases, comparison of drug delivery by RBC vs. liposomes would be similar to other nanocarriers; hence this paper focuses on liposomes, quite appropriately for celebration of the career and legacy of Frank Szoka [6–15].

Section 3. Overview of RBC and liposomes as drug delivery systems.

Section 3.1. RBC and liposomes: general, membrane and biomechanical features.

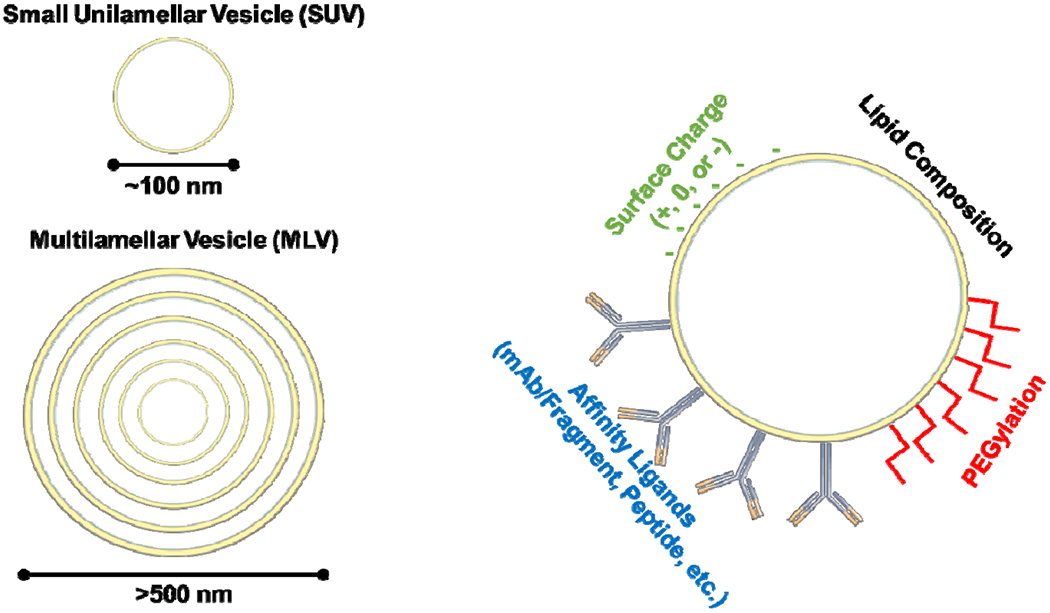

Scores of different garden varieties of liposomes have been described since Bangham. These multitudes feature distinct sizes, charges, and structure of the membranes (Figure 2). For example, large multilamellar vesicles (MLV) have found use for dermal drug delivery and cosmetics. In contrast, small unilamellar vesicles (SUV) represent arguably the most useful formulation for drug delivery via the bloodstream.

Figure 2:

Liposome engineering strategies. Liposomes can be produced with different numbers of lipid bilayers (lamellarity) and the lipid composition and surface coating can be engineered based on intended use.

Liposomes and RBC are very different from almost every aspect except that both represent in essence vesicles formed by a membrane bilayer composed of phospholipids, cholesterol and other components. RBC membranes contain scores of glycoproteins, which either span the membrane or are anchored in one of its leaflets. The inner surface of RBC membrane is reinforced by the cytoskeleton containing tens of proteins including spectrin forming the lattice underlying the membrane and connected to its integral and associated glycoproteins (Table 3).

Table 3.

Structural and biomechanical features of liposomes vs RBCs. Calculations of the liposome surface area and volume assumes 5 nm thick bilayer and range of particle diameters from 50-250 nm [18].

| Features | Parameters | Liposomes | RBC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Particle | Character and source | Artificial, synthesis | Natural, blood |

| General structure | Vesicle | Vesicle | |

| Size | 50-250 nm | 5,000 nm | |

| Shape | Spheres and elongated | Bi-concave disks | |

| Surface charge | Variable | Negative | |

| Homogeneity | Variable | Exceptionally high | |

| Inner volume | 3.3x10−5-7.2x10−3 μm3 | 94 μm3 [16] | |

| Surface area | 7.85x10−3- 0.20 μm2 | 136 μm2 | |

| Membrane | General structure | Phospholipid bilayer | Similar to liposomes |

| Leaflet asymmetry | Can be engineered | Yes (PS inside) | |

| Common lipid additions | Cholesterol | Diverse [17] | |

| Exotic lipid additions | Sphingomyelin, steroids | Diverse | |

| Main non-lipid components | None | Glycoproteins | |

| Outer surface additions | PEG, targeting moieties | Glycocalyx, sialic acids | |

| Inner surface additions | May contain some above | Membrane cytoskeleton | |

| General features | Relatively simple | Complex | |

| Biomechanics | Deformability | Variable | High |

| Mechanical sturdiness | Limited | Exceptionally high | |

| Role in the longevity | Unknown | Very important | |

| Distribution in flow | Marginal zone | Main stream | |

| “Collective behavior” | Not known | Form stacks | |

Abbreviations: PS - phosphatidylserine

These structural elements provide RBCs with exceptional biomechanical features, including their ability to change shape, permitting squeezing through capillaries smaller than the RBC and maintain their structural integrity under such harsh hydrodynamic conditions as the heart chambers and the aorta. This is one of the reasons why liposomes and RBC have dramatically different behaviors in the body.

Section 3.2. RBCs and liposomes in circulation.

From the first studies of liposome properties in vivo, it was apparent that, without additional engineering, liposomes injected directly into the bloodstream are cleared within minutes [19, 20]. These early studies not only revealed the poor circulation time of liposomes, but also their dose-dependence in pharmacokinetics (PK), primary clearance organ (liver), and main cells responsible for elimination (Kupffer cells and hepatocytes) [20]. Reasons for this rapid elimination from the circulation include: A) formation of a protein corona that includes molecules promoting recognition by phagocytes (e.g., complement and immunoglobulins) [21–24]; B) subsequent uptake by macrophages of the reticuloendothelial system (e.g., hepatic Kupffer cells); and C) extravasation into tissues with sufficiently ‘leaky’ vasculature (e.g., liver, spleen, tumor, sites of inflammation).

The poor circulation time of unmodified liposomes is a substantial barrier to liposome delivery to the desired organs, particularly if extravasation is required to reach the intended site, as in solid tumors. For the past 40 years, there has been significant investment in approaches to prolong the circulation time of liposomes, providing them with sufficient time to capitalize on enhanced vascular permeability in pathologically-altered tissues such as tumors and sites of inflammation. Early studies focused on introducing lipids into the bilayer that would either alter physicochemical properties, such as charge, thereby reducing interactions with endothelial cells and opsonins [25–28]. The most well-established technique used to prolong the circulation of liposomes is to coat the particle surface with polyethyleneglycol (PEG), which was first reported in the early 1990s to improve the circulatory half-life of liposomes from <30 minutes to 5 hours [29, 30]. PEGylated liposomes, also referred to as stealth liposomes, are widely used by groups pursuing liposomal drug delivery. Mechanistically, the flexible, hydrophilic PEG chains promote retention of liposomes in the bloodstream by repelling opsonins [31], inhibiting cellular interactions [32], and improving particle stability [33].

A more elaborate strategy that has been utilized to avoid clearance by the immune system is to mimic natural pathways that are employed by host cells and infectious agents (e.g., bacteria and viruses) to evade the host defense system. For example, when compared to spherical particles, elongated, flexible nanoparticles (filomicelles) that are able to align with blood flow were shown to have prolonged PK and improved targeting due to evasion of immune clearance [34–36].

In contrast to rapidly cleared liposomes, the typical lifespan of RBCs in circulation is on the order of 4 months, which is controlled by the interplay of several key factors. In circulation, the RBC population is, in essence, a distribution of cells ranging from freshly matured RBCs to aged, rigid RBCs about to be cleared by the spleen. First, RBCs are highly deformable, due to their lack of a nucleus. It has been appreciated for over 50 years that deformability of RBCs is critical to their in vivo lifespan [37, 38]. In fact, the spleen has evolved to sequester RBCs that have become more rigid as part of its natural function in clearing senescent and damaged RBCs [39, 40]. Second, many membrane components of the RBC protect them from opsonization and lysis by complement, including decay accelerating factor (DAF, CD55) [41–43], CD59 [44, 45], and Complement Receptor 1 (CR1, CD35) [46], blockade from recognition by host defense via terminal sialic acids of the glycocalyx [47–49], and specific ligands inhibiting uptake by phagocytes, such as CD47 [50–52]. Loss of any or all of these factors protect RBCs as a result of pathologies or normal cellular aging/senescence will accelerate RBC clearance, largely by red pulp macrophages in the spleen.

In recent years, there has been interest in harnessing the molecular mechanisms utilized by RBCs to protect themselves from elimination as tools to improve the circulation time of artificial nanoparticles. These approaches include: A) engineering biomechanical properties of nanoparticles to mimic those of RBCs [53, 54], B) conjugation of peptides derived from the “don’t eat me” marker, CD47, to the surface of nanoparticles in order to inhibit phagocytosis [55–58], C) inhibition of complement binding to nanoparticles by co-administering peptides derived from DAF [59], and D) camouflaging nanoparticles by wrapping them with fragments of the RBC membrane [60–63].

Of these approaches, there has been perhaps the most significant investment into coating nanoparticles with fragments of the RBC membrane. While this strategy does lead to substantial improvements in nanoparticle PK [62, 63], it does not lead to circulation times even remotely approaching that of pristine RBCs. This is likely due to factors including: A) damage to the RBC membrane during processing likely leads to loss of key structural features, such as shielding of phosphatidylserine on the inner leaflet of the membrane bilayer, and potential membrane inversion [64], and B) the biomechanical features of RBC-camouflaged nanoparticles do not match those of the natural RBC.

Section 4: Liposomal drug delivery: a bird’s eye view glancing over the huge continent.

The literature on liposomal drug delivery is immense (Figure 1). It encompasses tens of thousands of publications presenting hundreds of formulations of liposomes and other lipid-based DDS formulations including lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) that recently advanced to the use in patients for delivery of siRNA and mRNA-vaccines.

Any attempt to overview this field in the space of this paper would be overtly superficial and fragmentary. Here we just breeze over this field touching upon a few aspects most relevant in the context of comparison of liposomes and RBCs, while addressing interested readers to landmark reviews on liposome drug delivery, including the contributions of the esteemed addressee of this dedicated volume, one of the leading liposome pioneers and experts, Frank Szoka. Dr. Szoka’s work spanned over 40 years including the seminal PNAS manuscript in 1987 on reverse phase evaporation formulation of liposomes cited over 2300 times [65], among other foundational works [66–68], to the significant contributions in gene delivery [69–72], liposome formulation [73–75], targeting anti-microbial delivery [76], and cancer [66, 68–90].

Section 4.1. Loading liposomes: inner, surface and membrane.

In five decades of exploration of liposomal DDSs, these nanocarriers have been loaded with a wide variety of pharmacological agents. Insofar, the majority of agents have been encapsulated into the inner volume encircled by the liposome bilayer and several formulations employ intercalation of hydrophobic agents into the membrane proper, whereas coupling cargoes onto liposome surfaces represents a more exotic loading approach.

A diverse array of cargo drugs have been loaded into liposomes, ranging from small molecules to proteins and nucleic acids. A classic example of a small molecule drug that is efficiently loaded into liposomes is doxorubicin, which is able to achieve such high concentrations inside the particle that it forms crystals that are enveloped by the membrane. Loading of biotherapeutics into the aqueous core of liposomes provides protection from extracellular proteases/nucleases and permits intracellular delivery of the encapsulated therapeutic. Successful loading and delivery of any therapeutic using liposomes requires careful particle formulation.

Loading of small molecule drugs, for which there is the most experience in development of liposomal formulations, is dependent on the physicochemical properties of the drug itself, namely hydrophilicity/lipophilicity (Log(P)), solubility, pKa, etc. Considering one of these properties – hydrophilicity – as an example, a hydrophilic drug is defined as highly soluble (>1000 mg/ml), soluble (33-100 mg/ml) and sparingly soluble (10-33 mg/ml) [91]. Notable among the latter category is doxorubicin, which was the first FDA-approved liposomal formulation, Doxil [92, 93]. Essential considerations for the design of liposomes containing small molecule hydrophilic drug include composition of the lipid membrane and its permeability, driven in part by phospholipid tail length and charge [91], the size of the vesicles, and the approach to drug loading (see Table 5). As lipophilicity of drugs increases, the localization of drugs within the liposome shifts from the aqueous core (hydrophilic) to the lipid bilayer (hydrophobic), with amphililic molecules either associating with the membrane/core interface or forming micelles within the aqueous core.

Table 5.

Liposomal drug loading.

| Loading Method | Localization | Drug Properties | %EE | Pros | Cons | References [91, 97–104] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Passive | Thin film hydration | Aqueous core | Hydrophilic small molecules Proteins |

<5% | Small batch Good for lab scale |

Low encapsulation Small internal volume Not scalable High drug leak |

[67, 105] |

| Lipid bilayer | Lipophilic small molecules | <5% | |||||

| Freeze/thaw-extension of TFH | As above | As above | 5-20% | Increased internal volume Improved PDI |

Not scalable High drug leak |

[91, 106–108] | |

| Reverse phase evaporation | Aqueous core | Hydrophilic drugs | ≤50% | Increased loading Useful for protein drugs |

Solvent contamination | [65, 91, 107] [109] | |

| Active | pH/salt gradient | Aqueous core | Weak base small molecules | ≤100% | Increased loading | Limited to weak bases Potential resistance to drug release at target site |

[91, 110, 111] |

| Ionic gradient | Aqueous core | Weak acid small molecules | ≤100% | Increased loading and retention | Limited to weak acids | [100, 112, 113] | |

| Cyclodextrin pre-encapsulation | Aqueous core | Hydrophobic or poorly soluble/non-ionizable drugs | ≤95% | Enables active loading of non-ionizable drugs | Limited utility | [114–116] | |

| Dehydration-rehydration | Aqueous core | Proteins, other large molecules | 20-52% | Increased loading of large molecules | Potential protein denaturation | [91, 108, 117, 118] | |

Abbreviations: EE-encapsulation efficiency; TFH- thin film hydration, PDI-polydispersity index

Computational modeling of drug properties has been developed enabling the identification of viable drug candidates for remote loading into liposomes describing advantageous loading and leak parameters [94–96]. Good candidate drugs, or “active pharmaceutical ingredients” (API) were defined as loading at a drug to lipid mole ratio of >0.2-0.3 and load with 70-90% efficiency [96].

Section 4.2. Modification of liposomes by PEG, ligands, membrane permeating and responsive elements.

In all cases, the surface features of liposomes mediate their interactions with desirable targets and undesirable off-target destinations, which can be modulated by, among other methods, conjugation of affinity ligands or PEG (5-10 mol%) to the surface, respectively. By attaching affinity ligands (e.g. antibodies and fragments [Fab, scFv]) specific for target determinants to the surface of liposomes, both tissue and cellular selectivity of delivery can be enhanced. Beyond antibody-derived molecules, other affinity ligands that have been used include, carbohydrates, peptides, endogenous molecules (e.g. transferrin, growth factors, etc.), and aptamers.

In the early 1990s, it was described that by adding PEG to the surface of a liposome, the blood half-life could be improved from minutes to hours, likely by reducing opsonization and RES clearance [29, 30]. This engineering strategy was critical in development of liposomal doxorubicin (Doxil) and other FDA-approved formulations [93, 119]. The molecular features of PEG (e.g. hydrophilicity, hydration capacity, etc.) sterically impedes opsonization of liposomes [120]. Kristensen et al demonstrated that when stealth and antibody-stealth liposomes were probed in vivo, surface bound protein was found in greater amounts when compared to in vitro incubation with fetal bovine albumin serum. However, the protein coating was described as sparse, and in both cases, the liposome’s size and targeting properties were retained [121]. PEGylated lipids were originally thought to be immunologically inert, but immune responses to PEG-conjugated nanocarriers have been revealed to result in rapid clearance upon repeated administration, the production of antibodies against carrier components, and infusion reactions such as complement (C) activation-related pseudoallergy (CARPA) [122]. Correspondingly, PEG liposomes have resulted in cases of allergenic responses even in the treatment of naive patients [123].

Active, ligand-mediated liposome targeting was developed to provide specificity and focus to liposomal drug delivery. Early studies of monoclonal antibodies and scFv attached to stealth liposomes showed enhanced targeting including significant tumor accumulation with as few as 10s of ligands per particle attached to a PEGylated liposome [124, 125]. Expansive research has emerged since then into active targeting of liposomes using a variety of ligand types [103, 104, 126–129], and for myriad applications and therapeutic focus [97, 103, 129–131]. Ligand conjugation to formed liposomes is commonly facilitated by binding the targeting moiety to a functionalized phospholipid headgroup anchor exposed and somewhat distal to the vesicle surface [74]. Derivatization of lipids for this purpose is a wide field [132, 133] and the chemistries vary [102, 126, 134–141].

Coupling affinity ligands and other functional groups to the liposome surface provides benefits by attaching to the end groups of flexible spacers (e.g. PEG). However, this revealed a mechanistic conundrum. By ‘fouling’ PEG molecules with affinity ligands, the stealthiness (long circulation time, evasion of phagocytic clearance) provided by PEG was abrogated, resulting in more rapid clearance from the circulation. On the other hand, attaching ligands directly to the surface of the liposome (and between PEG molecules) impaired affinity-based interactions with the target, while maintaining stealthiness. Engineering of PEG (and other spacers) can help restore the balance between stealthiness and targeting. For example, by coupling PEG to the liposome surface with labile linkers sensitive to pathological changes in pH, temperature, enzymatic activity (e.g. thrombin, matrix metalloproteinases), etc., particles will remain stealthy (and thereby avoid clearance) until they reach the desired site. Upon exposure to pathophysiological cues, the PEG coating will be shed, exposing affinity ligands that can be directly coupled to the surface of the liposome, permitting specific recognition of target cells.

Once the target cell is engaged, internalization becomes the priority. Two major approaches to use for targeting are cellular determinants involved in vesicular uptake (e.g., endocytosis, phagocytosis or pinocytosis) and using membrane-permeating peptides inserting amphiphilic sequences into the plasmalemma and forming transmembrane channels. The specificity and safety of membrane permeabilizing proteins (MPPs) is a somewhat contentious issue. Indeed, making holes in the plasmalemma may be dangerous for the cell; after all, hemolysis caused by complement poking the RBC membrane is the natural way of interaction of MPP with cellular membranes.

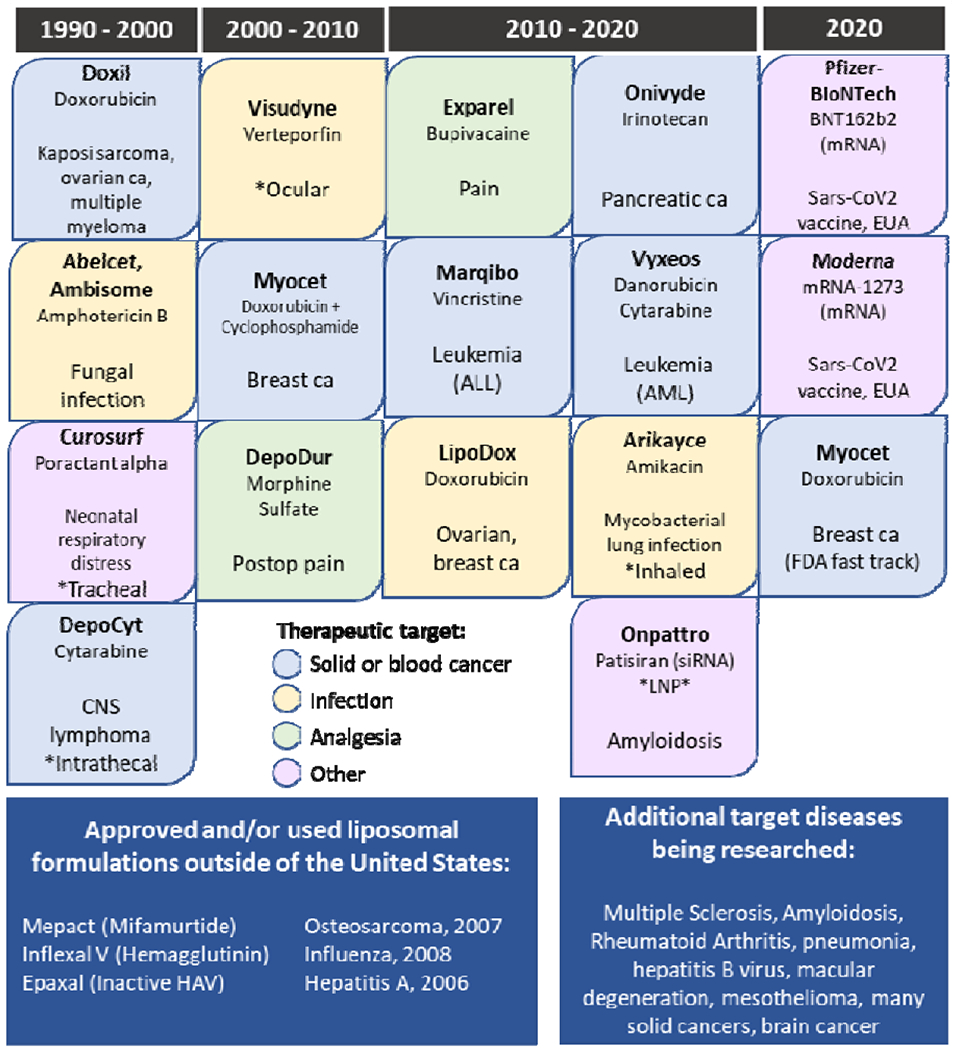

Section 4.3. Clinically used formulations.

Today, liposomes are widely used clinically for a variety of indications by multiple routes of delivery. The first liposomal nanomedicine to be FDA approved was Doxil (doxorubicin) in 1995 for the treatment of Kaposi’s sarcoma. Doxil was soon followed by approval of two liposomal formulations of amphotericin B, a potent but toxic anti-fungal used to treat invasive fungal infections. It is telling that the first approved medications were against cancer and infection, respectively, as the bulk of approved liposomes have remained in these two therapeutic categories (Figure 3). Most striking is the use of liposomal chemotherapies to treat cancer, whereby the liposome allows both for protection of the drug from host defenses and protection of off-target host cells from drug toxicities. Currently approved liposomal nanomedicines are used to treat solid tumors such as breast, ovarian, and pancreatic cancer as well as liquid tumors such as leukemia and lymphoma. While most liposomal formulations have been designed to be intravenously injected, there are several notable exceptions. Curosurf (poractant alpha) is delivered directly to the trachea where its site of action is in the distal lung alveoli. Visudyne (verteporfin) is delivered ocularly. Newest to the market, Arikayce (amikacin), is delivered via inhalation to treat nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary infection. Finally, two mRNA Sars-CoV-2 vaccines were granted emergency use authorization by the FDA in 2020. While these formulations are lipid nanoparticles not liposomes, their approval and use are noteworthy due to widespread use and acceptance worldwide [149–154].

Figure 3.

FDA-approved liposomal nanomedicines, including select lipid-based, non-liposome formulations

Section 4.4. Persisting challenges of liposomal DDS: limited bioavailability and efficacy of drug delivery.

Liposomes, LNPs and other lipid-based DDS provide remarkable improvements of the PK/BD, targeting and intracellular delivery of pharmacological agents. Indeed, the rapidly growing roster of these formulations approved for clinical use and in the human studies serves as convincing testimony of the general success of this DDS platform. However, persisting challenges remain, especially when we assess DDS performance in absolute rather than relative units. Analysis of two delivery parameters, namely blood level and uptake by the target, illustrates the point.

First, blood PK remains limited even for the most long-circulating formulations of PEG-stealth and camouflaged nanoparticles. It is true that they may afford orders of magnitude prolongation of the blood PK. However, their comparison with PK of basal formulations, featuring dismal t1/2 as short as few minutes, makes an impressive relative but not so impressive absolute gains. In general, blood PK has a lot of room for improvement.

Second, accumulation in the target tissues in most cases remains at levels of a percent of injected dose (%ID), even for DDS targeted by affinity ligands or equipped by sensors of the local microenvironment. The lion’s share of injected DDS goes elsewhere and misses the target.

New approaches are needed to resolve these formidable challenges. It appears that one such approach is to converge advantages of liposomes and other nanocarriers with advantages offered by the natural blood carriers, red blood cells.

Section 5: RBC drug delivery.

The general notion of using RBC as a carrier for drug delivery has been conceptualized and preliminary characterized in experimental model systems in the 1970s [2]. Initial animal studies provided rather mixed results, likely due to loss of RBC biocompatibility [155, 156]. In the 1980s, RBC drug delivery had been surpassed by liposomes and other synthetic carriers. Nevertheless, several labs persisted and devised biomedically useful approaches for RBC loading by drugs progressing from in vitro proof of principle [1, 157–159] and studies in animal models [160, 161], to clinical trials in human patients [162–165]. At the present time, there are two modes of drug loading to RBC: encapsulation into the inner volume vs. surface loading.

Section 5.1. Loading cargoes to carrier RBC.

From the somewhat oversimplified drug delivery standpoint, an RBC, like a liposome, has just the same three compartments that can be used for loading of pharmacological cargoes: A) aqueous inner volume, B) plasma membrane surface; and, C) membrane bilayer proper (Table 7). The loading into the RBC membrane itself is yet to be to explored. This proposition might seem strange on the first glance, but one must remember that a significant (in some cases major) fraction of some drugs injected in the bloodstream seems to naturally partition rapidly exactly into this underused compartment [166].

Table 7.

Methods of RBC drug loading.

| Drug loading | Approaches | |

|---|---|---|

| Inner | Via pores induced by hypotonic swelling | Established |

| Using MPP | Exploratory | |

| Genetic modification of reticulocytes | In progress | |

| Surface | Chemical conjugation to surface proteins | Exploratory |

| Insertion into membrane phospholipids | As above | |

| Physical absorption | As above | |

| Binding mediated by affinity ligand | As above | |

| Membrane | ||

Abbreviations: MPP – membrane permeabilizing protein

To our knowledge, most drug delivery applications of RBCs that have reached the clinical phase of development employ the first compartment, i.e., encapsulation of cargoes into RBC. Surface loading approaches, which in theory are arguably more diversified in terms of the loading mechanisms and features of amenable cargoes, are rapidly picking up the developmental race. Below we briefly outline inner and surface loading.

Section 5.1.2. Encapsulation of cargoes into RBC.

RBC represent, in essence, membrane vesicles filled with hemoglobin that renders this corpuscle with an ability to bind, transport, and release oxygen - arguably, the most important natural cargo of RBC. From the initial experimental attempts to use RBC for drug delivery, most researchers loaded pharmacological cargoes - small drugs and biological macromolecules alike – into the inner space of RBC [2]. Such loading usually occurs at the expense of loss of at least fraction of hemoglobin (and many other RBC proteins, which normally reside within the aqueous inner volume). Some drugs and radioisotopes (e.g., 51Cr) may have affinity for hemoglobin that can be harnessed to achieve high internal cargo loading.

In a way, placement of the cargo inside RBC is similar to encapsulation into liposome. However, in contrast with liposomes, which can be loaded during their formation with minimal interference in the integrity and features of the membrane, RBC is already pre-formed by Mother Nature and, therefore, cargoes must be smuggled across the RBC membrane. This is not a trivial task taking into consideration the key role of this unique structure in RBC biocompatibility and longevity.

There are several approaches to achieve this goal including use of membrane-permeating peptides (MPP) and amphiphilic agents, such as TAT-peptide from HIV, which has been employed for delivery of a plethora of agents including diverse nanocarriers into the cytosol of variety of cells. TAT is positively charged and likely its cationic nature plays a role in universality of its binding to the plasmalemma of diverse cell types, usually negatively charged. The mechanism, specificity, safety and limitations of TAT-mediated delivery into cells apparently involves macropinocytosis and perhaps alternative mechanisms of active vesicular transport, which do not exist in RBC. Most likely, TAT and other MPPs form mono- and multimolecular insertions into RBC membrane bilayer, just as melittin, the hemolytic agent from bee venom. The downsides of MPP-mediated drug loading into RBC include obvious risk of hemolysis, limited dosing, technical difficulties, lack of specificity, and translational issues, e.g., QC, scale up, cost.

Alternative approaches are based on formation of transient openings in the RBC membrane. Some relatively exotic methods use physical force such as ultrasound, but so far, the most popular and clinically advanced method is based on formation of transient openings in the RBC membrane via osmotic swelling in hypotonic solution. Cargo enters the RBC in exchange for hemoglobin leaving the cell, both driven by a concentration gradient, and post-loading the RBC (or, more precisely, its ghost) gets resealed by return to isotonic buffer. There are several European models of semi-automatic machines designed for this procedure, which takes about half an hour and can be applied to either autologous blood taken from the patient before a procedure or allogeneic donor blood.

RBC-encapsulated pharmacological agents including drugs, nanocarriers, biotherapeutics, probes and magnetic compounds have been devised and studied in vitro, and, to a lesser extent, in vivo – both in laboratory animals and in patients. The advantages of having drugs inside RBC, just like in liposomes, include reduced unintended interactions of the cargo with the body and, in many cases, deceleration of clearance from blood of agents that have short life span in circulation. Thus, enhancement of bioavailability of a circulating pool of RBC-encapsulated drugs can potentiate and prolong effects of drugs that act upon target molecules diffusing via the RBC membrane.

Alternatively, “silent” RBC-encapsulated agents may be viewed as pro-drugs, which act on their therapeutic targets upon release from the RBC carrier. However, the controlled release of the cargoes from RBC carriers is a fairly challenging and as of today not achieved goal. Prototype studies imply that natural mechanisms of RBC lysis by complement might be co-opted for this purpose, but translation of this idea to the practical use has yet to be achieved [167].

Finally, RBC-encapsulated agents may exert their effects upon uptake by phagocytic cells. In this context, the more damaged the carrier RBC is due to loading, the more effective is the “passive targeting” to host defense cells. This paradigm offers an advantage of co-opting natural biological mechanisms for delivery agents modulating host defense in many possible ways. First, RBC-loaded with anti-inflammatory drugs such as dexamethasone or other steroids or NSAIDs can help to minimize systemic adverse effects of these drugs. On the contrary, delivery of agents inducing activity or transformation of macrophages from M1 to M2 phenotypes and vice versa may help modulate these components of anti-tumor defense. Further, delivery of antigens loaded into RBC to the macrophages including dendritic cells may help modulate presentation to lymphocytes leading to cellular and humoral immunity or/and immunological memory.

Section 5.1.3. Coupling therapeutics to the RBC surface.

Surface RBC loading has also been explored for decades using diverse methods and cargoes. The most advanced and widely explored approaches include non-specific adsorption, insertion into phospholipid bilayer, chemical conjugation to RBC reactive groups (e.g., on membrane glycoproteins), genetic modification of RBC precursor cells, and affinity targeting to RBC surface determinants. These approaches include non-covalent attachment of agents via streptavidin to RBC covalently conjugated with biotin derivatives. Of note, such biotinylated RBCs are widely employed in clinical investigations to trace circulation of RBC in the bloodstream after injection in human subjects. Detection of biotinylated erythrocytes provides more accurate measurements than can be afforded by optical tracings, while avoiding use of radioactive isotopes undesirable for studies in humans.

Coupling drugs to the RBC surface avoids membrane damage inflicted by creation of pores or transmembrane permeation needed for encapsulation in the inner space. It also bypasses the need for release of drugs encapsulated in RBCs which is yet to be developed into a practically applicable approach [168]. Further, surface loading can be performed in one step, either in vitro or in vivo.

Section 5.1.4. Chemical conjugation of drugs to RBC.

Chemical conjugation of antigens and immunoglobulins to RBCs (devised a century ago for agglutination-based immunological tests) has been adopted to conjugate cargoes to carrier RBCs [169–171]. However, non-specific cross-linking agents such as glutaraldehyde and tannic acid provided no control over the attachment site and profoundly altered RBC membranes.

These methods were surpassed by conjugation to RBC amino acids [172–174], sulfhydryl groups [175], sugars [176] and lipids [177, 178]. However, biocompatibility of modified RBCs remained an issue [179–183]. Early RBC carriers activated complement [177, 184], leading to hemolysis [185] and rapid elimination of RBCs [184, 186–189].

Development of more precisely controlled conjugation methods [171, 177, 190–192], preserving endogenous inhibitors of complement (DAF and CD59) in the RBC membrane [192–194] permitted coupling of drugs to RBCs with less damage. The circulation of RBC/drug complexes approximated those of control RBCs for at least several days after injection in rats and mice [190, 195].

Of note, DAF and CD59 are anchored onto the luminal surface of RBC membranes via a glycophosphatidyl inositol (GPI) anchor [196]. Methods to insert DAF, CD59 and other GPI-linked proteins into the RBC plasmalemma using lipid anchors have been developed [197, 198]. Insertion of GPI-anchored CD59 into the RBC plasmalemma protects against complement [199]. Insertion of GPI-linked cargoes into RBCs might be employed for drug delivery [200], in particularly for transfer cargoes to vascular cells [201] and to host defense cells [202].

Further, non-covalent attachment via streptavidin provides a modular approach for RBC surface loading of diverse biotinylated agents. Biotin groups for this purpose can be inserted non-covalently via phospholipid biotin derivatives, or covalently conjugated to selected amino acids including tyrosine and glycine and sugar moieties [167, 177, 187, 189–191, 194, 195]. Genetic modification of reticulocytes allowing site-specific conjugation of biotin groups offers a new approach for this purpose [203]. Of note, biotinylated RBCs are widely employed in clinical investigations to trace circulation of RBC in the bloodstream after injection in human subjects. Detection of biotinylated erythrocytes provides more accurate measurements than can be afforded by optical tracings, while avoiding use of radioactive isotopes undesirable for studies in humans [204–206].

Section 5.1.5. Targeting cargoes to RBC surface determinants.

As Karl Landsteiner discovered a century ago, RBCs express on their surface scores of epitopes recognizable by immunoglobulins that can be found in blood of animals injected with RBC - heterologous and homologous (i.e., of different and the same animal species) [207, 208]. This discovery -- defining ABO blood groups on human RBC -- provided the basis for safe, effective worldwide practice of blood transfusion beyond the realm of autologous RBC i.e., auto-donated by the same patient (as it turned out, autologous RBC may inflict immune reactions when injected after inadequate storage leading to RBC damage).

Taking the paramount importance of safe blood transfusion and management of natural blood group conflict between the fetus and mother, the multitudes of studies identified the specific RBC proteins and glycoproteins defining the immunological properties of RBCs. In addition to ABO and Rhesus families of RBC antigens, these efforts yielded tens of other epitopes exposed normally or upon RBC senescence and their mapping on RBC proteomics. Also, clinical and animal studies characterized the consequences and management of the hemolysis ensuing from the RBC immunological conflict. These studies defined the toxic features of free hemoglobin and mechanisms of acute damage in diverse organs notably the kidney. Pathological pro-inflammatory adhesion of RBC to endothelium and host defense cells plays important roles in malaria, PNH, SCD and other RBC-related conditions.

This wealth of knowledge of “what can go wrong” in relationships of RBCs with the rest of the body provides a priceless inheritance for the RBC drug delivery field. In particular, the notion of immunological recognition of RBC antigens and epitopes provided the basis for the RBC drug delivery strategies using affinity ligands for non-covalent loading of drugs and their carriers to RBC surface. This is a highly modular and versatile approach.

Varieties of ligands binding to RBC surface determinants and used for affinity loading of the cargoes include antibodies, their fragments and recombinant derivatives including single chain variable region fragments (scFvs) and heavy chain-only camelid antibody fragments (nanobodies), as well as affinity peptides isolated by screening of phage display libraries. With respect to IgG-based ligands, the above sequence represents the line of progression that started with use of antibodies - polyclonal in the early studies and predominantly monoclonal counterparts for the last quarter of century. Yet, all antibody-based ligands have translational challenges and, more importantly, exert unintended effects on the RBC including but not limited to epitope clustering, cross-linking, agglutination, rigidification and Fc-fragment phagocytosis and complement activation. Using scFv and nanobodies and other recombinant derivatives featuring monovalency and absence of an Fc domain solves these issues.

Varieties of the RBC determinants used for binding of these ligands and their conjugates include epitopes of major RBC proteins such as glycophorin A (GPA), band 3, and Rh system antigens, as well as relatively scarce RBC sites such as CR1. The latter determinant is fairly unique in that it allows non-damaging binding to RBC of not just CR1 antibody, but multimolecular conjugates consisting of anti-CR1 and antibodies to pathological mediators, pathogens and cytokines. RBC carrying such multimolecular complexes bind these objects circulating in the bloodstream and deliver them to macrophages in the RES where this blood waste gets captured from the RBC surface without damaging the RBC. It may be that in addition to some not yet understood features of CR1, its low density on the RBC is important (<1,000 copies per RBC). High-density RBC glycoproteins such as GPA and Band 3 enable much heavier loading of ligand-coupled drugs and nanocarriers to RBC, but exceeding 10,000-20,000 molecules per RBC impairs carrier biocompatibility. More recent studies addressed this issue using human RBC and found that epitopes of Rh system seem more amenably undamaging binding of ligands than GPA and Band 3 [209].

The varieties of cargoes conjugated with these ligands using chemical or recombinant techniques include model drugs and drug delivery systems including antibody-coated liposomes and agents for management of thrombosis, bleeding, inflammation, stroke, blood clearance of pathogens, immune response and other conditions. In general, RBC surface loading offers unique features and opportunities including: A) Unprecedented level of control of specific sites on the RBC used for binding of the cargo and dosing of the load, B) Cognizant modulation of the strength of binding, allowing control of the rate of loading and its reversibility, and C) the affinity-mediated binding of drugs to the RBC surface allows unique possibilities to load drugs and nanocarriers directly on RBC circulating in bloodstream, avoiding the necessity of ex vivo loading and transfusion.

Section 5.1.6. Functional features of RBC-conjugated drugs.

The roster of pharmacological agents surface-loaded onto RBCs is extended, diverse and grows rapidly. It features proteins including ligands of all sorts (antibodies, immunoglobulins and their fragments, peptides, modulators such as cytokines and molecules capturing these mediators), enzymes (e.g., fibrinolytics), and non-enzymatic modulators (e.g., thrombomodulin). Chemical conjugation of diverse polymers has been designed to mask blood group determinants in the quest for artificial universal donor blood as well as to improve the hydrodynamic properties of modified RBC and provide the flexible extended linkers for coupling of other cargoes.

Candidate cargoes for surface loading RBCs include antigens and cytokines to modulate host defense [210], present ligands for vascular targeting of RBC cargoes [170, 211, 212], capture circulating pathological agents [213–215], or provide complement inhibitors to protect RBCs against pathological hemolysis, e.g., in the syndrome paroxysmal nocturnal hematuria (PNH) [216].

Due to relatively limited accessibility of extravascular compartments to the 5-micron RBC, this carrier seems most attractive for the agents whose targets are localized within the blood. For example, considerable attention is devoted to RBC surface loading and delivery of drugs that help control blood fluidity, coagulation, bleeding and thrombosis included conjugating to RBCs fibrinolytics [211] and heparin [217]. Anti-thrombotic agents used in emergent settings [218, 219] but requiring rapid elimination dictates use of high doses [220] posing risk of bleeding [221–224] and other side effects [225].

Coupling anti-thrombotic drugs to the RBC [211, 217, 226] prolongs their circulation and minimizes diffusion into the CNS and pre-existing hemostatic plugs. RBC/PA complexes injected in mice and rats circulate orders of magnitude longer than PA, providing prophylactic delivery of PA to the interior of nascent thrombi while a 10-fold higher dose of soluble PA is ineffective [227–229]. RBC/PA trapped within growing clots rapidly form patent channels that permit perfusion of oxygen-carrying host RBCs prior to complete clot disintegration [227, 228]. Delivery of PAs to the interior of nascent thrombi, while sparing preformed clots, make them suitable for thromboprophylaxis in settings where the risk of thrombosis and bleeding are both high [229, 230].

RBC carriage favorably alters several important PA features: i) it switches PA from activating pro-inflammatory receptors in the CNS parenchyma to protective signaling via intravascular receptors [231–234]; ii) the RBC glycocalyx attenuates inactivation of coupled PA by plasma inhibitors [235] and its adverse interactions with vascular cells [236]. RBC/PA: i) lyse cerebral thrombi in mice and rats, providing reperfusion, brain protection and improving survival; ii) alleviates brain injury in rats with intracranial hemorrhage and blunt trauma; and iii) protects brain in pigs with cerebral thrombosis [233, 234, 237–239]. In stark contrast, free PA causes CNS bleeding, neurotoxicity and lethality in these settings.

RBC may also be utilized to modulate the immune response – skewing it towards either immunogenic or tolerogenic phenotypes. One such approach involves loading RBCs with either steroids or protein antigens [240, 241]. Several studies have highlighted the ability of RBC-based drug delivery to bias the immune response [242–245]; however, the mechanisms underlying the directionality of immune modulation (activation vs. suppression) are not fully elucidated at this point [246, 247]. It is likely that this response is controlled by a myriad of factors, including, but not limited to: loading approach, extent of loading, changes in RBC biocompatibility, surface patterning of antigen, dose amount, and route of administration [248, 249]. This nascent and rapidly evolving field of RBC-based immune modulation has potential applications in a wide range of therapeutic areas.

Section 5.2. Clinical testing and applications of RBC-encapsulated drugs.

RBC-encapsulated drugs are currently used therapeutically in clinical trials and several formulations have reached clinical trials (Table 9) [250–252]. Two RBC-encapsulated enzymes, asparaginase and thymidine phosphorylase, have been used in humans. Asparaginase has been encapsulated into RBCs and studied for therapeutic use in mammals since 1976 [253] and in humans since 2011 [254]. Known to be effective in acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), the enzyme asparaginase has been a mainstay in the treatment of ALL since the 1970s. However, it exhibits significant toxicity to non-cancer cells. By encapsulating asparaginase into autologous RBCs in a study of 13 patients, half-life was increased from 10 to 50 hours and no clinical host toxicity was observed [164, 165]. Further developed by Erytech Pharma and now called GRASPA®, RBC-encapsulated asparaginase causes fewer and less severe allergic reactions compared to the usual asparaginase formulation used in pediatric ALL [254]. Currently, GRASPA is in a Phase 3 trials for pancreatic duct adenocarcinoma and Phase 2 for refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia.

Table 9.

Examples of DDS based on encapsulation of cargoes into RBC.

| Cargo | Disease | Principle | Testing Phase |

|---|---|---|---|

| L-Asparaginase | Acute lymphoblastic leukemia Pancreatic cancer Ulcerative Colitis |

RBC are loaded with asparaginase to act as drug depot that increases enzyme half-life and reduces toxicity to host | Phase 2 Phase 3 Phase 2 |

| Phenylalanine ammonia lyase (PAL) | Phenylketonuria | RBC are modified to produce PAL, an enzyme that breaks down phenylalanine, with increased half life and reduced immune-mediated side effects | Phase 1 (active, not recruiting) |

| Thymidine phosphorylase | Mitochondrial neurogastrointestinal encephalomyopathy | RBC are loaded with thymidine phosphorylase, replacing the enzyme missing in this autosomal recessive condition | Phase 2 |

| Adenosine deaminase | ADA | Progenitor cells are transduced with lentiviral vector- cDNA for human ADA | Phase 2 |

| Dexamethasone | Ataxia telangectasia Breast cancer |

Delivery to host defense cells *only non-enzyme drug* |

Phase 3 Phase 3 |

Thymidine phosphorylase, another enzyme that has been encapsulated by RBC, has also seen early progress in humans. A Phase 1 trial in which 3 subjects with mitochondrial neurogastrointestinal encephalomyopathy were given erythrocyte-encapsulated thymidine phosphorylase, two patients were noted to improve clinically, and none had serious adverse events [255, 256]. This therapy has been approved for Phase 2 testing although is not yet recruiting.

The last RBC-carried enzyme, phenylalanine ammonia lyase (PAL) is not encapsulated, but is expressed by genetically engineered transfused RBC and used to treat phenylketonuria, an inborn defect in metabolism. The investigational drug, RTX-134, is composed of allogeneic RBC that are engineered to express Anabaena variabilis phenylalanine ammonia lyase [257]. Recruiting for the Phase 1b trial is currently on hold.

One non-enzyme small molecule drug, dexamethasone, has been encapsulated into RBC as dexamethasone-21-phosphate (dex-21-P) [181]. Several studies have demonstrated clinical improvement in patients with irritable bowel disease who were treated with autologous dex-21-P loaded RBC [258].

Section 5.3. Genetically Modified RBC.

In recent years, there have been concerted efforts made to genetically engineer RBC precursors to provide mature RBCs with desirable features. One such example that is relevant for drug delivery is the introduction of functional groups permitting site-specific conjugation of molecules to the RBC surface. By introducing an amino acid sequence recognized by bacterial Sortase A (LPETG) into select membrane proteins, specific conjugation of biotin [259] and antigenic peptides [260] was achieved without substantial adverse effects on the RBC. More recently, direct fusions of RBC surface proteins to antibody fragments have been introduced to generate RBCs with endogenous affinity to select target molecules [261], In addition to drug delivery applications, genetic engineering of RBC precursors has been used to improve outcomes in transfusion medicine by generating RBCs that have the appropriate surface markers for a given patient [262]. This approach has great potential in improving outcomes in patient populations requiring chronic blood transfusions (e.g. sickle cell disease, β-thalassemia, etc.).

Section 5.4. Applications of RBCs as Sensors

Beyond the use of RBCs as ‘natural’ DDSs, there has been significant interest in converting RBCs into biosensors and diagnostic agents [263]. Encapsulation of magnetic nanoparticles, namely superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles (SPIO), into RBCs has been shown to improve the circulation time of these particles [264]. This approach has been applied in animal models to use SPIO-loaded RBCs as MRI contrast agents that can be used for long-term monitoring [265–267]. This provides utility in monitoring disease progression in chronic diseases without the need for frequent administration of contrast agents.

RBCs have also been loaded with molecules that change their optical activity in response to a given stimulus, termed erythrosensors, providing a non-invasive approach to detect concentrations of certain molecules in the bloodstream [268]. A fairly straightforward example that was developed for in vitro use was encapsulation of a pH-sensitive fluorophore (FITC) into erythrocytes to monitor pH changes. Briefly, as the internal pH of the erythrosensor equilibrated to the bulk solution pH, fluorescence changed in a quantifiable manner, providing a highly sensitive readout of pH [269]. An ideal erythrosensor would be able to detect changes in blood markers in vivo (e.g. blood glucose levels) with high sensitivity. There have been several publications describing the use of red blood cell-derived vesicles as biosensors [270, 271]; however, to date, there are no descriptions of in vivo erythrosensor applications using intact RBCs or RBC ghosts.

Section 5.5. Comparison of RBC vs liposomal DDS.

As highlighted above (Section 3.2), the behavior of RBC and liposomes in the circulation is drastically different, with RBCs circulating for months and liposomes circulating for no more than a few days, despite substantial efforts being devoted to engineering their PK. However, beyond simple consideration of circulation time, their capacity for achieving drug delivery to desired sites must be considered when devising a drug delivery strategy (Table 10).

Table 10.

Comparison of drug delivery features of liposomes and RBC.

| Features | Parameters | Liposomes | RBC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carrier | Target access | Relatively high | High in blood |

| Extravasation | Yes | Normally none | |

| Effect of pathology | Varies from EPR to blocking access | Massive uptake in clots and bleeding sites | |

| Circulation time | Minutes to days | Months | |

| Majority of injected dose | Rapidly taken by RES | Remains in blood cells | |

| Clearance organs | Liver | Spleen | |

| DDS utility | Improving PK of insoluble drugs | Long-term pool in blood | |

| Targets | Blood, RES and tissue components | Blood, vascular cells and RES | |

| Intracellular delivery | Yes, in many cell types via many mechanisms | To macrophages in RES | |

| Advances and issues | Versatility | High | Limited |

| Control of structure | Considerable | ||

| Challenges | Heterogeneity | ||

| Immunogenicity | Relatively low | Self-tolerance to autologous RBC |

A key component to drug delivery is access of the DDS to the target site, which is controlled by many carrier (size, charge, flexibility, targeting ligand, etc.) and pathology (perfusion, edema, cellular infiltration) -dependent properties. For a target that resides within the vasculature, both liposome- and RBC-based DDS will face no accessibility barriers following intravascular administration, barring complete loss of blood flow to the pathologically altered tissue. On the other hand, micron-sized RBCs have effectively no access to extravascular sites under normal conditions, save for the splenic red pulp. Sites of bleeding would provide a rare example where RBCs could be used for drug delivery to an extravascular site. On the other hand, liposomes are generally an order of magnitude smaller than RBCs, with typical diameters of 50-300 nm. This smaller size may allow extravasation of liposomal DDS into select tissues with ‘leaky’ vasculature, such as liver, spleen, bone marrow, tumors, and sites of inflammation [272].

Beyond achieving delivery on a tissue-level, drugs must reach the desired cells and sub-cellular destinations in order to elicit a beneficial effect. Internalization of RBCs is only performed by phagocytes that recognize damaged or aged cells; therefore, achieving intracellular drug delivery with drugs encapsulated within the RBC is likely only to provide high drug load in splenic macrophages. Intracellular delivery of liposomes can be achieved not only non-specifically by phagocytes, but also through affinity targeting to internalizable membrane receptors. This can provide delivery of liposomes and their encapsulated cargoes to specific cells and endosomal sorting pathways.

By considering circulation time (3.2), clearance organs (3.2), and target accessibility, potential biomedical applications of RBC- and liposome-based DDS can be identified. RBCs, which circulate for months and are confined to the bloodstream, are able to serve as long-term depots of drug in the bloodstream. Small molecule drugs will utilize the RBC carrier as a slow-release depot, with the drug leaking from the long-circulating RBCs into the plasma. This would be analogous to either a slow infusion, but with much greater capacity for providing sustained delivery over prolonged periods of time. On the other hand, liposomes, while useful for chronic applications (e.g. repeated doses of Doxil in oncology), are not able to match the 4 month lifespan of RBCs. This suggests that RBC carriage could be amenable to reducing the dosing frequency needed compared to liposomal drugs. However, these carriers are excellent for enabling use of insoluble drugs that cannot be otherwise administered parenterally. Liposomes are also useful for directing increased fractions of the dose relative to free drug to desired sites, either passively (EPR, edema) or via active targeting, sparing organs that may be susceptible to adverse effects. For example, liposomal doxorubicin reduces drug uptake into the heart, thereby reducing the severe, long-term cardiotoxicities associated with free doxorubicin administration [273, 274].

In addition to considerations of PK and biodistribution, utility of any DDS can be limited by recognition by host defense systems, particularly with chronic dosing. While lipid vesicles are not generally immunogenic per se, engineering their surface to improve their in vivo behavior may result in unwanted immune system recognition. Following the first injection, the circulation time of PEGylated liposomes is typically significantly longer than their bare counterparts. However, the accelerated blood clearance (ABC) phenomenon, wherein clearance increases upon subsequent doses, was identified within just a few years of PEGylation becoming a popular approach in nanomedicine [275, 276]. The underlying mechanism of this phenomenon was identified as formation of anti-PEG IgM following liposome injection, indicating formation of an adaptive immune response [277, 278]. The use of RBCs as DDS is not anticipated to lead to any adverse immune reactions as current protocols rely on reinfusion of drug-loaded, autologous RBCs, which will be recognized as ‘self’ by the host immune system.

Section 6. Using RBC for vascular delivery of nanocarriers.

The earliest report of loading nanoparticles onto the RBC surface was published 45 years ago by Juliano and Stamp who extracted sialoglycoproteins from erythrocyte membranes and incorporated them into liposomes. These liposomes were then bound to the RBC surface in vitro and the authors suggested that this approach could be useful for the development of targeted liposomes [279]. Antibody-based coupling of liposomes to the RBC surface was first described by the Papahadjopoulos group who used anti-RBC (Fab)2 and Fab fragments to obtain specific binding of liposomes to human RBC [280, 281]. The potential for antibody-directed loading of liposomes onto the erythrocyte surface was demonstrated in blood in the mid-1980s, both in vitro and in vivo, reducing uptake by the RES without impacting RBC circulation [282, 283]. In the late 1980s, a comparison of the effects of liposomes coated with anti-RBC Fab on RBC circulation was performed that demonstrated dose-dependent clearance of RBC induced by liposome injection [284, 285]. These pioneering studies were critical in demonstrating A) specific binding of immunoliposomes to RBCs, B) PK of RBC-coupled liposomes, and C) impact of RBC-coupled liposomes on erythrocyte biocompatibility; however, there were no clear biomedical applications of RBC-directed nanocarriers.

In addition to antibody-based targeting, in recent years several groups have reported alternative affinity ligands for coupling nanoparticles to the surface of RBCs. One of the most widely reported of these is the glycophorin A-binding peptide, ERY1, which has been shown to provide specific binding of nanoparticles to RBCs with minimal effects on RBC biocompatibility [286, 287]. Corn starch nanoparticles were demonstrated to preferentially bind to malaria-infected RBCs vs. naive RBCs due to expression of a hexose transporter in infected cells [288].

Targeting liposomes to the RBC membrane was first utilized for treatment of malaria in preclinical species. Liposomes coated with RBC-binding antibody fragments were used to facilitate the delivery of chloroquine to RBCs in mice infected with Plasmodium berghei [289–292]. Despite promising results of this strategy in the early 1990s, relatively few reports were published describing RBCs as a carrier for nanoparticles over the ensuing decades. This approach was revived in 2015 with a report describing treatment of Plasmodium falciparum infection in mice with glycophorin A-targeted liposomes [293]. Further work improved the specificity of liposomal treatment of malaria by targeting to a parasite-derived RBC surface marker (Plasmodium falciparum erythrocyte membrane protein 1, PfEMP1) to deliver multiple anti-malarial drugs to infected erythrocytes [294–296].

Recently, two forms of targeting to murine glycophorin A, antibody (Ter119) and peptide (ERY1), were compared as approaches to prolong the circulation of tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) encapsulated within nanoparticles. The authors demonstrated that nanoparticles with Ter119 on the surface had markedly prolonged PK and reduced uptake by the RES vs. peptide-coated and uncoated nanoparticles without overt adverse effects [297]. This demonstrates the key role that affinity ligand selection can play in utilizing RBCs to enhance PK of nanoparticles.

The use of RBCs as supercarriers for liposomes and other nanoparticles has significant advantages beyond modulation of pharmacokinetics and immune recognition of cargo nanocarriers. RBCs also have an extraordinary ability to enhance delivery of nanoparticles to specific, desirable sites in the vasculature. This approach, termed RBC hitchhiking, will be discussed in detail below.

Section 6.1. Nanoparticles hitchhiking on RBC (RBC HH): from early prototypes to proof of principle in animal studies.

Like other pharmacological cargoes, nanocarriers including diverse imaging probes and contrast agents have also been loaded both into the RBC inner volume and onto the RBC surface [267, 298]. In fact, binding of immunoliposomes to RBC have been reported in the 1980s [284, 285]. Standard approaches using osmotic swelling permit encapsulation of particles smaller than 50 nm [299, 300], while surface loading to RBC is more size-permissive [301]. Studies of several groups including our laboratories showed that loading onto RBCs cardinally changes the fate of nanoparticles (NP) in vivo.

First, coupling to RBCs prolongs NP circulation [302–304]. After IV injection in rats, polystyrene particles (~200-450 nm in diameter) were cleared in minutes, whereas RBC-bound nanoparticles remained in circulation for hours [305]. Dual labeling showed that while NPs eventually are removed from the blood, the RBCs to which NP were attached remained in circulation [305]. A kinetic model of detachment of nanoparticles from the RBC surface was consistent with the measured pharmacokinetics of RBC-bound nanoparticles [305]. Further, the in vitro rate of shear-induced detachment correlates with the in vivo circulation in rats [306]. Mechanical forces eventually remove nanoparticles from the RBC surface, which led to their clearance by the liver and spleen [307].

After IV injection, RBC-bound NP rapidly accumulate in the lungs, transferring to the vascular cells from RBC squeezing through the pulmonary microvascular bed, the first “capillary trap” after IV injection [307]. This is an example of the classical first pass phenomenon, described for several DDS targeted to endothelial cells [308–311]. First pass transfer varies for RBC-bound liposomes, albumin-NPs, lipid nanoparticles, polystyrene NP, and AAV loaded on RBC. For example, approximately 5 vs 30% of injected dose of RBC-bound PS NP vs. liposomes accumulated in mouse lungs after IV injection [312]. RBC HH improved lung-to-liver ratio for liposomes by almost 2 orders of magnitude.

Double-isotope tracing of cargo nanocarriers (including liposomes) and carrier RBC, flow cytometry and confocal microscopy asserted that A) after unloading of NP in the capillaries RBC continue to circulate as normal RBC, B) NP delivered by RBC to the pulmonary microvasculature transfer to endothelial cells, and C) neither carrier RBC nor cargo nanocarriers clumped or were entrapped in the lung capillary lumens [312]. A moderate fraction of the RBC HH NPs was taken up by marginated leukocytes [312], white blood cells that transiently reside in the capillary lumen, especially in the lungs [313]. Live cell imaging in vitro reveals that stationary phagocytes would grab RBCs flowed past them and remove the adsorbed NPs [312]. Thus, RBC HH with translatable NPs is produced by transfer from RBCs to endothelial cells and marginated leukocytes.

RBC HH of nanocarriers to the lungs might have important diagnostic and therapeutic implications [307, 312, 314, 315]. For example, RBC HH of nanocarriers loaded with fibrinolytic plasminogen activators afforded more effective dissolution of pulmonary thrombi in mouse model of fibrin clots lodged in the lung vasculature [312]. RBC HH of nanoparticles showed promising results in treating lung metastasis in murine models [314, 315]. NP loading has been reproduced using mouse, rat, pig and human RBCs. RBC HH worked in vivo in pigs, and in fresh, ex vivo human lungs that were oxygenated and perfused [312].

RBC HH is not limited to the lungs. It can be directed to other organs by infusion in the feeding arteries using intra-arterial (IA) catheters. Animal studies showed that this administration maneuver (widely used in clinical practice) enables an order of magnitude enhancement of the uptake of RBC-bound NP in the heart, kidneys and brain of mice [312].

The lung uptake of RBC-hitchhiking NPs was comparable with that of NPs targeted to lungs by antibodies to endothelial epitopes. For example, antibodies and single chain variable fragments to PECAM-1 and ICAM-1 are known to target cargoes to the vasculature especially in the lungs after IV injection [316–319]. Adsorption of ICAM-1 antibody on RBC HH NP enhanced residence of NP in the lungs, whereas pulmonary uptake increased to >50% vs 20% of injected dose for RBC-loaded vs. free anti-PECAM-NPs [312]. Combining RBC HH with NP targeting mediated by affinity ligands represents an attractive avenue of further development of this approach. In addition, modulation of NP geometry and mechanical feature allows the possibility to optimize their targeting and uptake by the target cells [320, 321]. In this context it is important that RBC-hitchhiking anti-ICAM-1 targeted rod-shaped nanoparticles exhibited a 6-fold improvement in lung/liver accumulation ratio compared to that by their spherical counterparts [322].

Section 6.2. RBC HH: New developments

Conventionally, RBC HH was devised for delivering nanocarriers to vasculatures immediately downstream the injection sites [307, 323]. New advances are emerging to understand the interplay between RBC HH and host defense system and to exploit the same for modulation of immune responses. In particular, nanocarriers carrying immunomodulatory agents, for example, antigens or adjuvants, can be delivered to target organs (e.g., lungs) by RBC HH and regulate local immune environments [324, 325]. This is exemplified by the recent demonstration that RBC HH could leverage metastases in the lungs and enable the induction of systemic anti-tumor immune responses for tumor eradication [324]. In brief, ImmunoBaits, chemokine loaded PLGA nanocarriers, were dominantly delivered to the lung capillary endothelium by RBC HH where metastasized cancer cells prefer to reside. Co-localization of ImmunoBaits with metastasized tumor cells and subsequent release of immunomodulatory chemokines awakened host defense cells to attack tumor cells that generated a systemic immune response that were able to eradicate local lung metastases while also preventing tumor recurrence [324]. This example highlights the immunological therapeutic potential that the combination of RBC HH with selected immunomodulatory nanocarriers can achieve opening up a window of opportunity to target disease environments for controlled regulation of immune responses.

Biologically, RBCs have close contact with immune cells in immunoactive organs such as the liver and spleen. In fact, immune cells in the spleen and liver continuously screen the status of circulating RBCs [50, 326]. For example, stationary phagocytes in the liver and spleen including Kupffer cells recognize and take up pathogens that bind to RBC surface via the immune adherence mechanism [327, 328]. These immunological attributes open up new possibilities of engineering RBC HH to deliver nanocarriers to these immune cells for immunomodulation purposes. The RBC HH process itself has been demonstrated to be able to modulate RBC biochemical and biophysical properties [329, 330] which in turn alter the location of and responses to the delivered nanocarriers. In particular, attachment of nanocarriers to RBCs induces concentration-dependent membrane alternations to carrier RBCs [325, 330]. It was demonstrated that when the nanocarrier to RBC ratio is increased above a certain threshold, the stiffness of RBC membranes increases due to limited fluidity of lipid domains [330]. Nanocarrier-induced RBC membrane stiffening likely reduces the stretching of RBCs in lung capillaries and thus reduces deposition of nanocarriers in the lungs. In addition, the increase in nanocarrier to RBC ratios also flips phosphatidylserine from the inner membrane to be expressed on to outer membrane of RBCs [325] which contributes to the increased cross-talk between immune cells in the spleen and RBCs. The two effects (RBC membrane stiffening and elevated phosphatidylserine expression), when combined, make a new RBC HH system capable of bypassing lung delivery and depositing nanocarriers to the spleen [325]. By controlling the nanocarrier to RBC ratio, the RBC HH system managed to prevent lung accumulation and caused enough phosphatidylserine expression to facilitate efficient delivery to the antigen-presenting cells in the spleen. This unique hand-off mechanism demonstrated significantly better efficacy for sustained splenic delivery of nanocarriers as compared to unhitchiked counterparts, without the sacrifice of the carrier RBCs. When using ovalbumin-coated nanocarriers as a model, hitchhiked nanocarriers led to an improved humoral and cellular response to the attached antigen. When tested in an ovalbumin-expressing lymphoma model, vaccination by hitchhiked nanocarriers performed as well as the CpG adjuvant without the need for an exogenous adjuvant [325]. This RBC HH approach involving transiently perturbed RBCs opens up opportunities for targeted delivery of nanocarriers to the spleen and for adjuvancy without depending on exogenous adjuvants which expands possibilities in the vaccine design space for speeding the vaccine development cycle to cope with many diseases including pandemic diseases such as the COVID-19.