Abstract

Rationale:

Nitric oxide (NO) produced by endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) protects against myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury (I/R). However, reperfusion of myocardium results in superoxide (O2•−) generation, which promotes eNOS glutathionylation that produces O2•− instead of NO. It is unclear whether glutathionylated eNOS (SG-eNOS) continues to produce O2•− indefinitely or undergoes a time-dependent degradation.

Objective:

To determine whether SG-eNOS continues to produce O2•− in I/R for a prolonged period causing accentuated I/R injury or it undergoes a time-dependent degradation.

Methods and Results:

Since SG-eNOS produces significant O2•− instead of NO, we sought to determine the time-course of SG-eNOS levels in the HCAEC in hypoxia/reoxygenation (H/R) by western analysis and immunoprecipitation. SG-eNOS was degraded by chaperone-mediated autophagy (CMA), as inhibitors of CMA rescued eNOS expression. We further confirmed CMA by high resolution confocal and electron microscopy. We showed that SG-eNOS is targeted by HSC70 chaperone via its interaction with glutathionylated-cysteine 691 and 910. Glutathionylation of cysteine 691 residue in H/R exposes 735QRYRL739 motif for interaction with HSC70, and consequent transportation to LAMP2A vesicle, where it is degraded by lysosomal proteases. Mutagenesis of these residues in eNOS inhibited its CMA. Using contrast echocardiography and electron paramagnetic resonance spectrometry (EPR), we found that Trx-Tg mice show improved myocardial perfusion and decreased myocardial apoptosis in I/R due to deglutathionylation of SG-eNOS and restoration of NO generation. Further, WT mice treated with recombinant human Trx (rhTrx) were protected against eNOS CMA, and restored NO production with improved myocardial perfusion and decreased I/R injury.

Conclusions:

SG-eNOS undergoes degradation via CMA, following prolonged retention in the cytosol. CMA of SG-eNOS terminates O2•− generation preventing further tissue damage but causes irreversible loss of eNOS and NO availability. Prompt deglutathionylation of SG-eNOS prevents CMA, promotes NO production, and improved myocardial perfusion, resulting in amelioration of reperfusion injury.

Subject Terms: Chronic Ischemic Heart Disease, Heart Failure, Myocardial Infarction

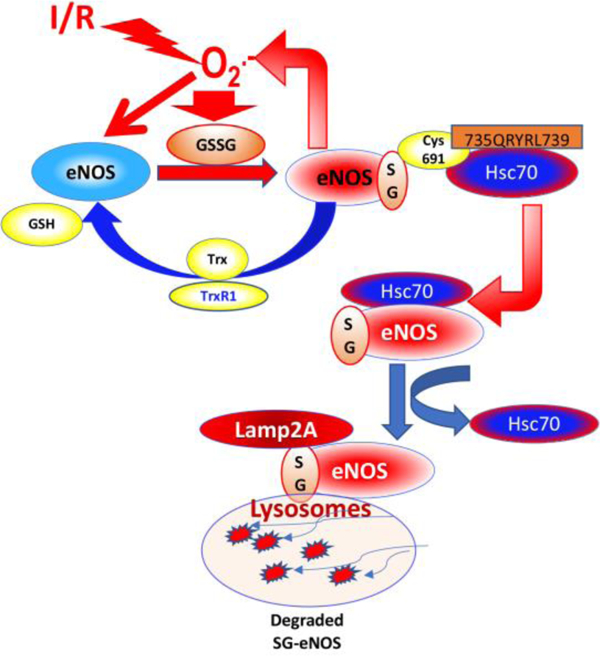

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Coronary heart disease with MI is a leading cause of mortality in USA and the world despite timely reperfusion of occluded coronary artery1. Restoration of blood flow following the removal of occlusion is associated with a complex pathophysiology, known as reperfusion injury, which may account for 50% of final MI size1. The molecular mechanisms of I/R are complex with myocardial cell death, vascular dysfunction, decrease bioavailability of nitric oxide (NO), generation of reactive oxygen (ROS) and nitrogen species (RNS), mitochondrial dysfunction and inflammation 2, 3. Impairment of coronary microvascular perfusion following I/R is a major detrimental factor in I/R that activates several vascular events leading to lethal reperfusion injury4. Microvascular dysfunction has been extensively evaluated, both clinically and in experimental models, and is highly prevalent post MI5, 6, which is associated with adverse outcomes such as larger MI size, lower LV ejection fraction, and adverse LV remodeling6. Myocardial ischemia-reperfusion induces impairment of coronary perfusion and myocyte death with time-dependent increase in infarct size leading to poor myocardial salvage. Progressive loss of functional myocardium in I/R injury is a major cause for adverse prognosis of MI patients. Reduced nitric oxide (NO) availability following I/R is a major detrimental factor in the loss of myocardium 3. Although findings in experimental animals show significant protective effect of NO in I/R injury, NO donors remain ineffective in protection against human I/R in clinical settings 2. On the contrary, pharmacological inhibition of NOS or eNOS-KO mice showed protection against I/R injury, demonstrating detrimental role of NO in I/R injury 2. However, these opposing effects of NO in I/R injury could be explained by the fact that temporal switching of eNOS to produce superoxide anion (O2•−) in I/R would accentuate I/R injury due to O2•− generation, which is known to interact with available NO and convert it to a more reactive peroxynitrite (OONO-).

A dysfunctional nitric oxide synthase (NOS) has been shown to produce deleterious O2•− instead of NO 7, 8 due to oxidation of its cofactor, tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) and/or due to S-glutathionylation 9. Thus, eNOS is a potent producer of O2•− in pathological conditions. The enzymatic production of O2•− by eNOS instead of NO is known as eNOS uncoupling 9. eNOS uncoupling due to BH4 oxidation resulting in O2•− production can further oxidize eNOS reactive cysteines, which would further promote eNOS-S glutathionylation 10. Therefore, BH4 oxidation and eNOS-S-glutathionylation complement each other in the production of O2•− instead of NO 11. Since, eNOS can produce both NO and O2•− depending upon the redox environment, cellular redox homeostasis is critical for maintaining the balance in NO and O2•− production by NOS. A balance favoring O2•− production depletes NO due to its interaction with O2•− that generates highly toxic peroxynitrite (OONO-) causing further damage to the cardiovascular tissue 12. While the deleterious effect of uncoupled eNOS due to O2•− generation and consequent decrease in NO bioavailability is well recognized as a detrimental factor in cardiovascular disorders the fate of uncoupled eNOS is yet unknown. It is also unknown whether uncoupled eNOS continues to generate O2•− in a sustained manner causing unabated cardiovascular events with accentuated tissue damage. This is a critical gap in our understanding of eNOS biology and its role in progression of myocardial injury and infarction.

Here, we provide evidence that eNOS produces O2•− due to S-glutathionylation in the coronary vasculature in I/R or in cultured endothelial cells in H/R. Our data indicate that glutathionylation of eNOS exposes KEFRQ-like motif that allows its interaction with chaperone protein HSC70, which transports it to the LAMP2A vesicles. Finally, SG-eNOS is degraded in autophagolysosomes via chaperone-mediated autophagy (CMA), indicating a highly regulated specific process of degradation of SG-eNOS, but not eNOS with other oxidative modifications. We further show that failure of SG-eNOS CMA due to depletion of HSC70 causes sustained production of O2•− with severe decrease in NO availability. We show that failure of an intervention to deglutathionylate eNOS results in unabated O2•− generation with more severe damage of the myocardium in reperfusion period. Collectively, our study demonstrates irreversible loss of eNOS in H/R or I/R due to its S-glutathionylation, and SG-eNOS CMA could be a protective mechanism to prevent extensive cellular damage due to continuous production of O2•− by SG-eNOS. We demonstrate that eNOS is irreversibly lost in the endothelium without further de novo synthesis if SG-eNOS reversal to eNOS is not achieved due to pharmacologic intervention. We further demonstrate that deglutathionylation of SG-eNOS by Thioredoxin (Trx) or other thiols such as N-acetyl L-cysteine (NAC) inhibits eNOS CMA and recycles eNOS back to produce NO.

METHODS

Data Availability.

Data supporting this study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. An expanded Materials and Methods section can be found in Online Supplement.

RESULTS

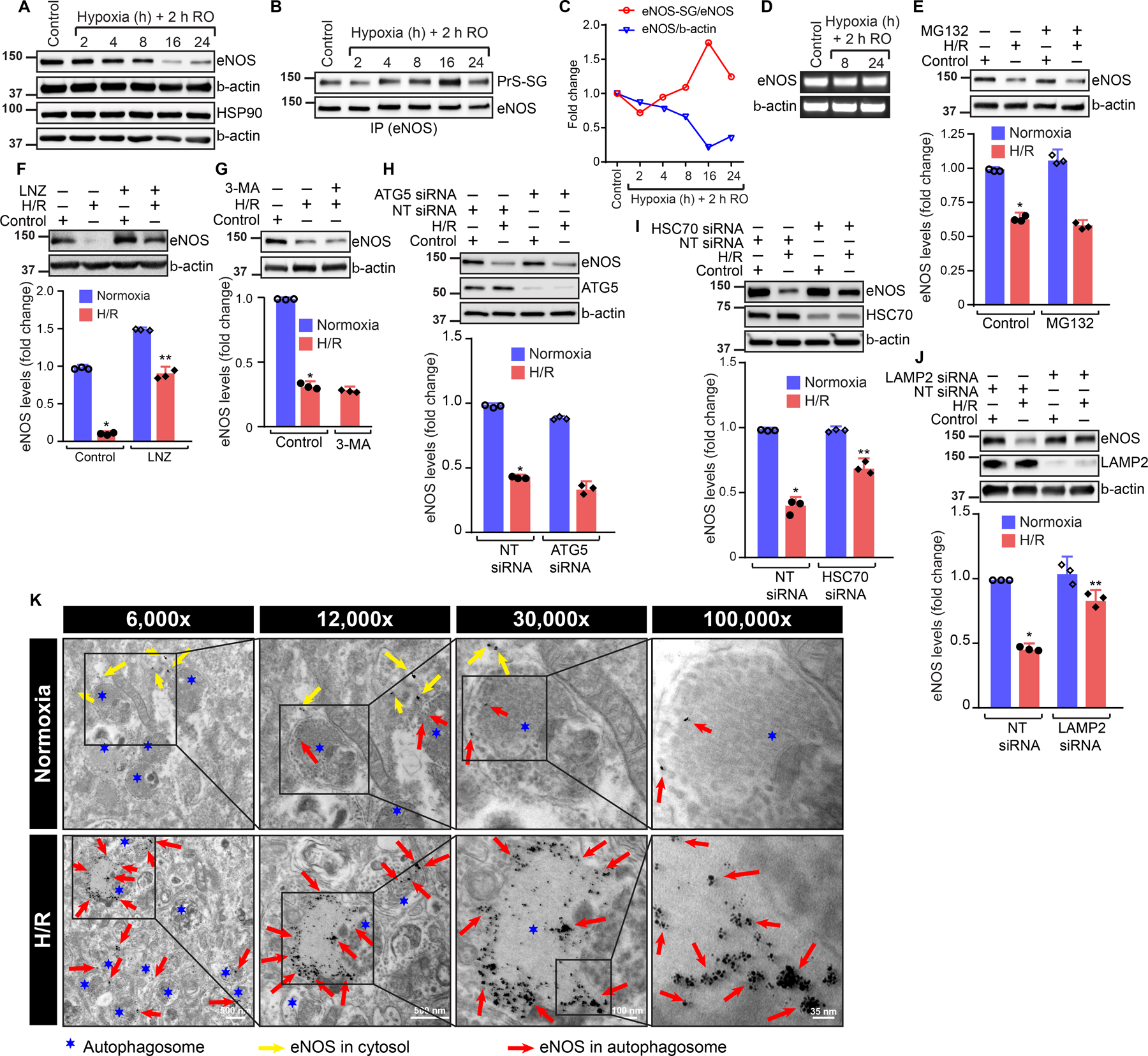

eNOS undergoes chaperone-mediated autophagy in H/R.

Studies have shown that treatment of cells with H/R induces S-glutathionylation of eNOS 9, and the glutathionylated eNOS (SG-eNOS) produces O2•− instead of NO 9. We hypothesized that SG-eNOS levels would increase in a time-dependent manner, as progressive increase in oxidative environment would result from eNOS uncoupling in I/R. We exposed HCAEC to H/R and found that the level of endothelial NOS (eNOS) was gradually decreased until 8 hours. However, eNOS expression was almost completely lost after 16 or 24 hours exposure to H/R (Fig 1A–C). In contrast, the level of S-glutathionylated eNOS (SG-eNOS) was steadily increased until 16 hours, after which the level of SG-eNOS was sharply decreased (Fig 1B–C). As shown in Fig 1C, the level of eNOS was decreased with concomitant increase in SG-eNOS until 16 hours, after which, both eNOS and SG-eNOS were severely decreased. Further, as shown in Fig I A–B, prolonged exposure to H/R did not recover eNOS. We also noted a basal steady state level of SG-eNOS (less than eNOS levels in 8 or 16 hours H/R exposure) in the normoxic cells, suggesting a dynamic equilibrium in the level of eNOS/SG-eNOS. There was no statistical difference in the eNOS mRNA levels (Fig 1D), indicating that post-translational S-glutathionylation of eNOS induces its degradation. To determine whether SG-eNOS is degraded by a specific pathway, we treated HCAEC with MG132, an ubiquitin ligase inhibitor21, but there was no statistical difference in the levels of eNOS in H/R and H/R+ MG132 treated cells (Fig 1E, H/R vs. H/R + MG132, non significant, 2-way ANOVA, P=0.8022). Further, treatment of cells with MG132 or 3MA (Fig IC) did not rescue the levels of eNOS, indicating that proteosomal degradation pathway is not involved in the SG-eNOS degradation process. However, lansoprazole (LNZ), an inhibitor of lysosomal pathway22 statistically significantly recovered eNOS after 24h H/R, suggesting a possible lysosomal degradation of eNOS due to S-glutathionylation (Fig 1F, H/R vs. H/R+LNZ, 2-way ANOVA, P=0.0001). In addition, as shown in Fig ID CMA inhibitors NH4Cl, CQ or LNZ increased eNOS expression in H/R, demonstrating a CMA pathway of degradation. Additionally, NH4Cl also increased SG-eNOS in H/R (Fig IE). Since LAMP2A and HSC70 interact with CMA substrates we evaluated the expression of these proteins in H/R. As shown in Fig IF, the expression of these proteins in H/R was similar to cells in normoxia. Additionally, the level of GAPDH remained unchanged in H/R or I/R, demonstrating GAPDH does not undergo CMA in H/R or I/R (Fig IG). Further, treatment of cells with 3-methyl adenine (3-MA), a macroautophagy inhibitor23 had no statistically significant effect on rescue of eNOS in H/R (Fig 1G, H/R vs. H/R+3MA, P=0.6499), suggesting macroautophagy is not a likely mechanism for elimination SG-eNOS. To delineate the specific autophagic process in SG-eNOS degradation, we depleted ATG5, a protein that is required for macroautophagy24 by RNA interference and evaluated its effect on eNOS levels. As shown in Fig 1H, depletion of ATG5 had no statistical significant effect on the loss of eNOS in H/R demonstrating that macroautophagy is not involved in the autophagy of SG-eNOS (H/R+NT siRNA vs. H/R+ATG siRNA, P=0.004856 (2-way ANOVA). Next, we depleted HSC70 that regulates CMA25 and found that depletion of HSC70 rescued eNOS protein level in H/R in a statistically significant manner (Fig 1I, H/R+NT siRNA vs. H/R+HSC70 siRNA, P=0.0001, 2-way ANOVA), suggesting a possible CMA pathway of eNOS degradation. Additionally, we depleted LAMP2, a rate-limiting protein in the CMA26, 27, and found that loss of LAMP2 resulted in statistically significant increase in eNOS levels in H/R (Fig 1J, H/R NT siRNA vs. H/R LAMP2 siRNA, P=0.0011, 2-Way ANOVA), demonstrating eNOS CMA in H/R. Finally, we analyzed eNOS autophagy using immuno-electron microscopy with gold nanoparticle labeled anti-eNOS and found eNOS localization within the double membrane bound autophagosome (Fig 1K). Taken together, these data provide evidence that eNOS undergoes CMA in H/R in endothelial cells.

Figure 1. eNOS undergoes chaperone-mediated autophagy in HCAEC in H/R.

A, Expression of eNOS and β-actin by Western blot analysis; B, anti-eNOS immunoprecipitates were analyzed with anti-GSH and anti-eNOS by WB; C, Time course of total eNOS and SG-eNOS levels (n=3); D, mRNA expression of eNOS and β-actin by RT-PCR; E, Western blot analysis in HCAECs treated with 10 μM of MG132 and exposed to H/R (16/2h). Fold change in eNOS expression, (n=3), P=0.8022 H/R vs. H/R +MG132 (Two-Way ANOVA); F, Western blot analysis of HCAECs treated with 10 μM of Lansoprazole (LNZ) and exposed to H/R (16/2h). Fold change in level of eNOS. (n=3), *P=0.0001 H/R vs. H/R+LNZ (Two-Way ANOVA); G, Western blot analysis in HCAECs treated with 1.5 mM of 3-methyladenine and exposed to H/R (16/2h). Fold change of eNOS. (n=3), P=0.6499, H/R vs. H/R+3MA; H, Western blot analysis of NT or ATG5 siRNA transfected HCAECs exposed to H/R (16/2h). Fold change of eNOS, (n=3), P=0.004856 (2-way ANOVA); I, Western blot analysis of NT or HSC70 siRNA transfected HCAECs exposed to H/R (16/2h). Fold change in level of eNOS, H/R+NT siRNA vs. H/R+HSC70 siRNA, P=0.0001, 2-way ANOVA (n=3); J, Western blot analysis of NT or LAMP2 siRNA transfected cells exposed to H/R (16/2h). Fold change of eNOS, (n=3), H/R NT siRNA vs. H/R LAMP2 siRNA, P=0.0011; K, Immunogold electron micrograph showing localization of eNOS in autophagolysosome in HCAECs exposed to H/R.

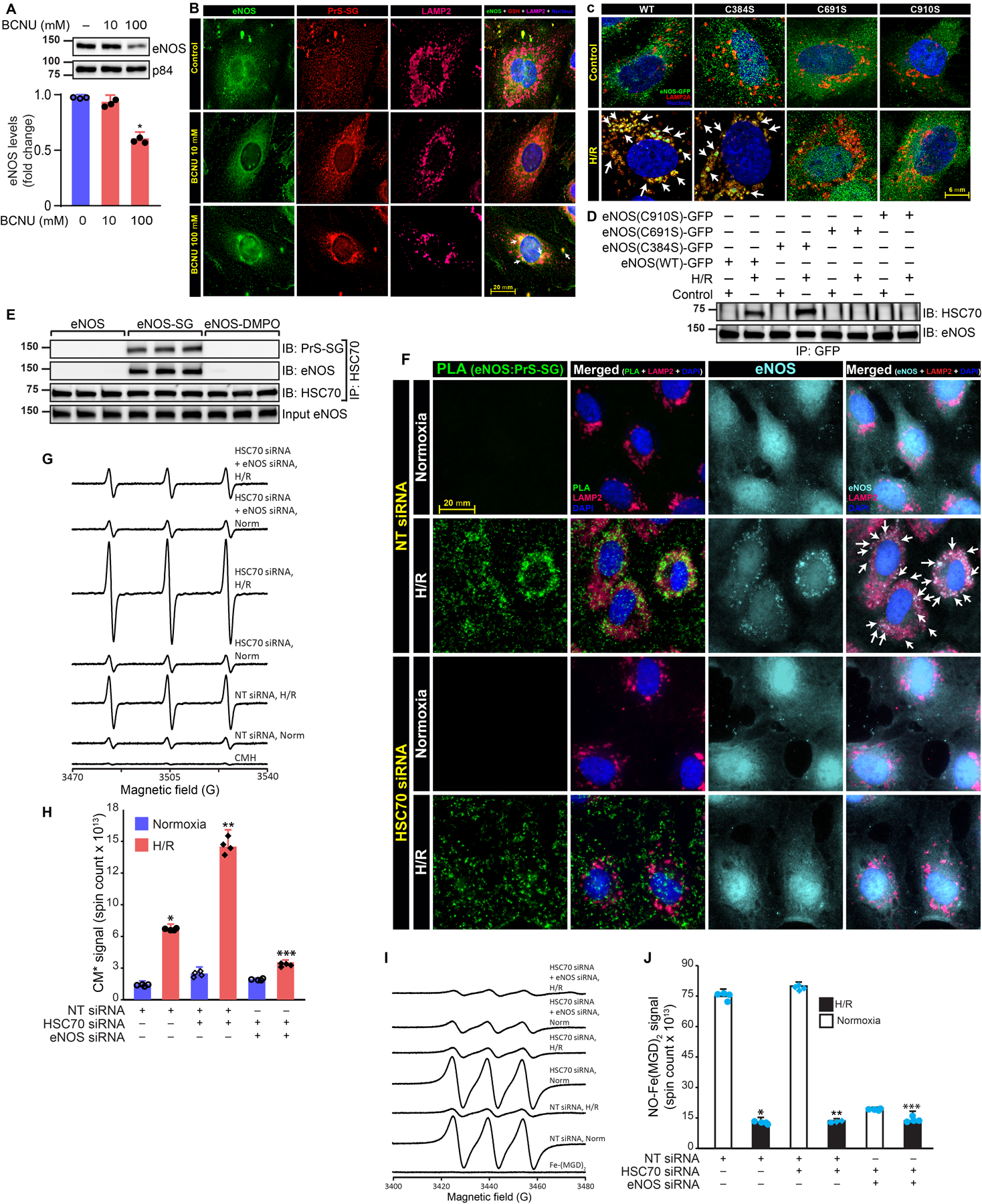

S-glutathionylation of eNOS induces its autophagy via HSC70 chaperone.

We sought to determine whether eNOS CMA is specifically induced due to S-glutathionylation, but not due to other oxidative modifications. If SG-eNOS specifically triggered CMA, then we should be able to increase eNOS CMA by agents that induce eNOS S-glutathionylation. We induced S-glutathionylation of eNOS by treating HCAEC with 1,3-Bis (2-chloethyl)-1 nitrosourea (BCNU) that increases GSSG by inhibiting glutathione reductase28, which is required to convert GSSG to GSH29. Increased levels of GSSG are known to S-glutathionylate reactive cysteines in protein thiols9. As shown in Fig 2A, eNOS expression was decreased in a dose-dependent statistically significant manner due to treatment of cells with BCNU (P=0.00111, untreated vs. lized in the lysosomal vesicle (Fig 2B), indicating SG-eNOS CMA in HCAEC without H/R. We also evaluated the effect of BCNU on HSC70 and LAMP2A. As shown in Fig II, there was no change in the expression of HSC70 or LAMP2A, although the level of eNOS was decreased in a concentration-dependent manner. We have previously reported that BCNU treatment results in increased GSSG levels 18.In addition, when we mutated the C691 and C910 residues in eNOS that are known to be glutathionylated in I/R9, 17, eNOS failed to localize in the lysosomal vesicle, indicating that S-glutathionylation of eNOS on those residues is required for its translocation to the autophagosome (Fig 2C). To demonstrate whether C691 and C910 are specifically contacted by HSC70 for eNOS autophagy, we transfected GFP-WT-eNOS and mutated GFP-eNOS into HCAEC and determined HSC70 co-immunoprecipitation in the IP samples of GFP. As shown in Fig 2D, HSC70 was co-immunoprecipitated with WT-eNOS and C384S eNOS mutant (C384 is not involved in glutathionylation) 10, but not in glutathionylation-defective C691S and C910S mutants, indicating that S-glutathionylation of C691 and C910 is required for eNOS CMA. Additionally, we found that WT-eNOS and C384S-eNOS-GFP were co-localized with LAMP2A vesicle, but C910S and C691S -eNOS-GFP did not co-localize with LAMP2A, indicating C691 and C910 residue glutathionylation is specifically required for CMA (Fig III). Further, we oxidized and S-glutathionylated purified eNOS protein, and transfected purified SG-eNOS into HCAEC, and as shown in Fig IV, transfected SG-eNOS was localized in the LAMP2A vesicle, indicating CMA. We also tested whether other eNOS modifications would induce eNOS autophagy. DMPO specifically interacts with reactive cysteine residues by covalent bond, and could inactivate the enzyme due to blockade of active sites 30. Protein thiols conjugated with DMPO are readily identified by western analysis using anti-DMPO antibodies 31. As shown in Fig 2E, eNOS-DMPO, an oxidatively modified eNOS did not undergo autophagy as demonstrated by its interaction with HSC70. Additionally, we oxidized eNOS in vitro, and treated it with anti-DMPO and transfected eNOS-DMPO into HCAEC to demonstrate whether other oxidative modifications of eNOS would undergo autophagy. As shown in Fig V, transfected purified eNOS-DMPO protein did not localize into lysosomal vesicle, indicating the absence of CMA in oxidative modifications of eNOS. We also immunoprecipitated HSC70 and found that SG-eNOS was co-immunoprecipitated with HSC70, but eNOS-DMPO did not co-IP with HSC70, confirming that SG-eNOS specifically interacts with HSC70 (Fig 2E). Next, we depleted HSC70 and determined localization of SG-eNOS by simultaneous PLA and immunofluorescence staining (Fig 2F and enlarged 2F in supplementary figures). We found that significant number of PLA signals representing high level of eNOS glutathionylation in H/R and this was further increased by loss of HSC70. Interestingly, depletion of HSC70 resulted in localization of SG-eNOS in cytosol instead of LAMP2A vesicles as seen in control cells in H/R. Collectively, these data demonstrate that HSC70 interacts with specific cysteine residues involved in S-glutathionylation. We reasoned that depletion of HSC70 would result in increased O2•− production due to accumulation of SG-eNOS, as CMA would be inhibited. To test this hypothesis, we depleted HSC70 in H/R and determined O2•− generation. As shown in Fig 2G–H, statistically significant (P=0.0000000001, 2-Way ANOVA) amount of O2•− was generated in HSC70 depleted cells compared to control cells, which was sensitive to eNOS depletion, as well as treatment with L-NAME (Fig VI), indicating that SG-eNOS continues to produce O2•− in the absence of CMA. We also measured the levels of NO in HSC70 or eNOS depleted cells. As shown in Fig 2I–J, NO production was statistically significantly decreased (P=0.00000001, 2-Way ANOVA) in H/R in HSC70 depleted cells and in eNOS depleted cells, demonstrating loss of NO production with concomitant increase in O2•− generation. We further evaluated whether O2•− produced by SG-eNOS would trigger CMA by mediating HSC70 interaction with SG-eNOS, as O2•− has been shown to induce autophagy32. As shown in supplementary Fig VIIA, the interaction of HSC70 with eNOS was not disrupted due to treatment of cells with PEG-SOD to remove O2•− produced by SG-eNOS. Likewise, PEG-SOD had no effect on eNOS-HSC70 interaction in eNOS depleted cells, as eNOS was associated with HSC70 in HSC70 immunoprecipitated cell lysates, and this association was not disrupted by PEG-SOD treatment (Fig VIIB). These data demonstrate that O2•− does not play any role in the interaction of SG-eNOS with HSC70.

Figure 2. S-glutathionylation of eNOS promotes its association with HSC70 and shuttling to LAMP2A vesicles.

A, Immunoblot of HCAECs treated with BCNU for 24h. Fold change of eNOS, *P=0.00111, untreated vs. BCNU (One Way ANOVA) (n=3); B, Immunofluorescence of eNOS and GSH; C, Confocal microscopy of HCAECs transfected with bovine-eNOS (WT)-GFP and cysteine mutants, exposed to H/R (16/2h), stained for LAMP2A and GFP, white arrow shows LAMP2A lysosomal eNOS; D, Immunoblot for HSC70 and eNOS in anti-GFP immunoprecipitated samples from HCAECs transfected with bovine eNOS (beNOS) (WT)-GFP and cysteine mutants (C384S, C691S and C910S), exposed to H/R (12/2h); E, Cell lysate from eNOS siRNA transfected and H/R-exposed HCAECs was incubated with purified eNOS or eNOS-SG or eNOS-DMPO. HSC70 was immunoprecipitated from the reaction and western analysis of immunoprecipitates was performed using anti-PrS-SG, and anti-eNOS; F, siRNA transfected HCAECs exposed to H/R (16/2h) and PLA was performed. Anti-LAMP2 antibodies were used to mark autophagosomes. Cyan pseudocolor was used to specify the localization of eNOS. Green foci-proximity signals of eNOS and PrS-SG; G, EPR spectra of CMH signal in HCAECs exposed to H/R (18/2h); H, Superoxide generation was calculated and plotted as bar graph, (n=4), H/R vs. H/R + HSC70 siRNA, **P=0.0000000001, (2-Way ANOVA), NT siRNA H/R vs H/R HSC70 siRNA+eNOS siRNA, ***P=0.0000000001; I, NO production was significantly decreased in HSC70 depleted cells, and also in eNOS depleted cells exposed to hypoxia,(n=3), ***P=0.00000001, 2-Way ANOVA (J).

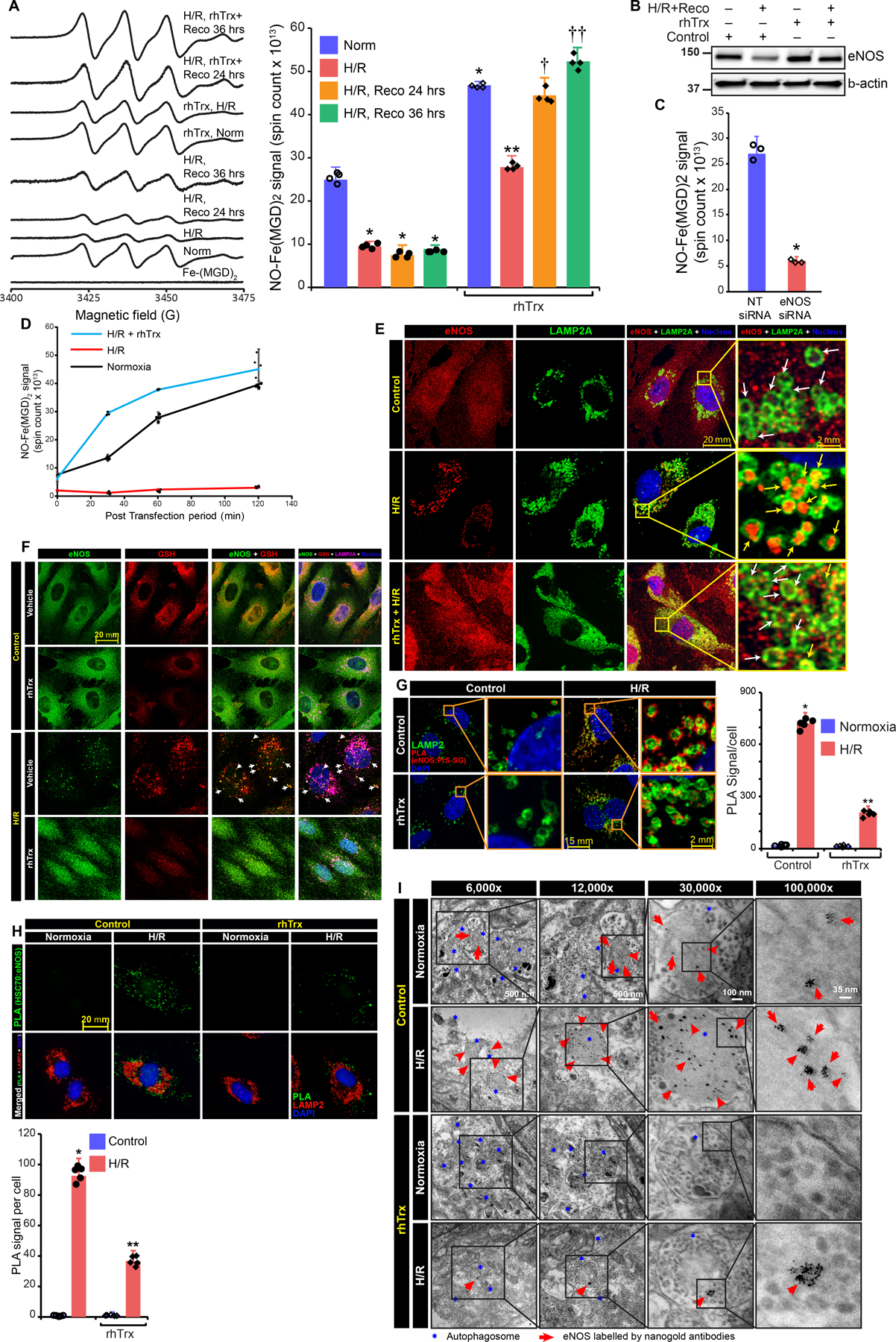

Prolonged retention of uncoupled eNOS in the cytosol results in CMA, but prompt deglutathionylation by deglutathionylating agents regenerates eNOS and prevents CMA.

We speculated that recovery of endothelial cells in room air following H/R might deglutathionylate SG-eNOS. We attributed this to the reversibility of S-glutathionylated proteins29. However as shown in Fig 3A, NO production was severely decreased in H/R, but did not improve in 24 or 36 hours of recovery in room air, demonstrating prolonged dysfunction of eNOS in H/R. We have earlier reported that Thioredoxin (Trx) a small cellular redox protein, deglutathionylates SG-eNOS18. Therefore, we treated HCAEC with recombinant human Trx (rhTrx) followed by exposure to H/R and recovery. As shown in Fig 3A, addition of Trx in the culture media statistically significantly increased (P=000013, 2-Way ANOVA) NO production in normoxia and rescued NO generation in H/R and in the recovery period. In addition, Trx rescued eNOS protein that was lost in H/R (Fig 3B), suggesting that deglutathionylation of SG-eNOS by Trx rescued eNOS protein. In addition, there was no change in eNOS mRNA in NT or Trx-Tg mice in I/R (Fig VIIIA) or HCAEC treated with rhTrx and exposed H/R (Fig VIIIB). To conclusively establish that deglutathionylation is critical for NO generation in H/R, we depleted endogenous eNOS, which caused significant reduction in NO production (Fig 3C) and transfected purified SG-eNOS protein into eNOS depleted cells with further exposure of these cells to H/R, room air or H/R plus rhTrx. As demonstrated in Fig 3D, SG-eNOS transfected cells exposed to H/R did not produce NO, suggesting the failure of cellular redox systems to deglutathionylate SG-eNOS in H/R. However, when SG-eNOS transfected cells were exposed to normoxia, NO production was increased in a linear manner over 2-hours, suggesting deglutathionylation of transfected SG-eNOS by normal cellular redox systems resulting in NO production, as these cells lack endogenous eNOS. Additionally, cells treated with rhTrx demonstrated robust NO production in H/R, indicating that deglutathionylation of SG-eNOS could be achieved by rhTrx under H/R stress (Fig 3D). Further, using high-resolution microscopy we found that eNOS remains within LAMP2A vesicles in H/R. But, in the presence of rhTrx it does not localize within the LAMP2A vesicle. This data demonstrates that SG-eNOS specifically undergoes CMA in H/R and rhTrx inhibits CMA due to deglutathionylation of SG-eNOS (Fig 3E).

Figure 3. Trx rescues eNOS expression, inhibits eNOS interaction with HSC70 and LAMP2A and prevents trafficking to autophagolysosomes in H/R.

A, EPR spectra of NO-Fe-MGD adduct formed from untreated or rhTrx (2 μg/mL) pretreated HCAECs exposed to H/R or rhTrx added after 24–36h recovery. Absolute spin counts of paramagnetic NO-Fe2+-MGD2 adduct signal. (n=4), * P = 0.00001 H/R vs control (ANOVA), **P =0.000111 H/R vs, H/R+rhTrx (2-Way ANOVA), †P =0000000836 H/R vs H/R+Trx recovery 24 h, ††P=00000065 H/R vs. H/R+rhTrx, recovery 36 h; B, immunoblot analysis in HCAECs exposed to H/R (24h/2h) and recovered for 24 in normoxic condition with and without treatment of rhTrx; C, NO generation was measured by EPR spectrometry, NO-Fe(MGD)2 spin counts were plotted as bar graph, (n=3), *P=000927 NT vs. eNOS siRNA (t-test, non-parametric); D, purified SG-eNOS protein was transfected either with or without rhTrx into H/R treated or untreated in eNOS depleted HCAECs. NO generation was determined by EPR spectrometry over 2-hours time (n=4); E, confocal microscopy of eNOS and LAMP2A. Yellow arrow shows LAMP2A localized eNOS; F, Confocal microscopy for eNOS, GSH, and LAMP2A. Arrow shows LAMP2A-localized eNOS; G, PLA using anti-eNOS and anti-PrS-SG antibodies in rhTrx pretreated HCAECs, exposed to H/R (16/2h); Anti-LAMP2A was used to mark autophagolysosomes; Red foci-proximity signals of eNOS and PrS-SG were counted and plotted as a bar graph. (n=5), ** (P=0.000000, 2-Way ANOVA); H, PLA using anti-eNOS and anti-HSC70 in rhTrx HCAECs. Anti-LAMP2A was used to mark autophagolysosomes. Green foci-proximity signals of eNOS and HSC70 were counted and plotted, (n=5). *P= 0.0000000001 H/R vs H/R+rnTrx, (2-Way-ANOVA). I, Immunogold transmission electron micrograph shows autophagolysosome localized eNOS in rhTrx pretreated and H/R (16/2h) exposed HCAECs.

We next determined whether SG-eNOS enters LAMP-2A vesicles using confocal microscopy and found co-localized GSH and eNOS immunofluorescence signals in LAMP-2A vesicles, which demonstrates that only glutathionylated form of eNOS shuttled to autophagolysosomes (Fig 3F). We further confirmed the SG-eNOS and LAMP2A association by PLA. As shown in Fig 3G, statistically significant increase (P=0.000000, 2-Way ANOVA) in proximity counts was noted in H/R treated HCAEC, however, cells treated with rhTrx following H/R had significant reduction in proximity counts. Because HSC70 is essential in the translocation of proteins for lysosomal degradation in CMA15, we determined whether SG-eNOS associates with HSC70 in H/R and whether this association could be disrupted by deglutathionylation of SG-eNOS by rhTrx. As shown in Fig 3H, treatment with rhTrx statistically significantly decreased (P=0.00000003) SG-eNOS:HSC70 interaction and presence in LAMP-2A vesicles. This data demonstrates that HSC70 interacts with SG-eNOS and translocates it to the surface of lysosomal vesicle where it interacts with LAMP-2A for subsequent internalization and degradation in the vesicle. We also tested whether N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC), which increases cellular glutathione levels and promotes deglutathionylation of glutathionylated proteins33, 34, would restore eNOS expression with decreased CMA. As shown in Fig IXA, treatment of cells with NAC deglutathionylated SG-eNOS, and rescued eNOS protein degradation in H/R (Fig. IXB) and decreased HSC70 interaction with eNOS (Fig IXC). We employed PLA to establish the deglutathionylating role of NAC. As shown in Fig X significant eNOS glutathionylation was observed as indicated by high GSSG-eNOS proximity that was decreased in NAC treatment of cells. We further evaluated eNOS localization within the autophagosome using immuno-electron microscopy. As shown in Fig 3I, treatment with rhTrx significantly decreased eNOS localization in the autophagosome, indicating that inhibition of SG-eNOS CMA is due to deglutathionylation by Trx.

Mutation of KFERQ-like motif of eNOS prevents its association with HSC70 and accumulation in LAMP2A vesicles.

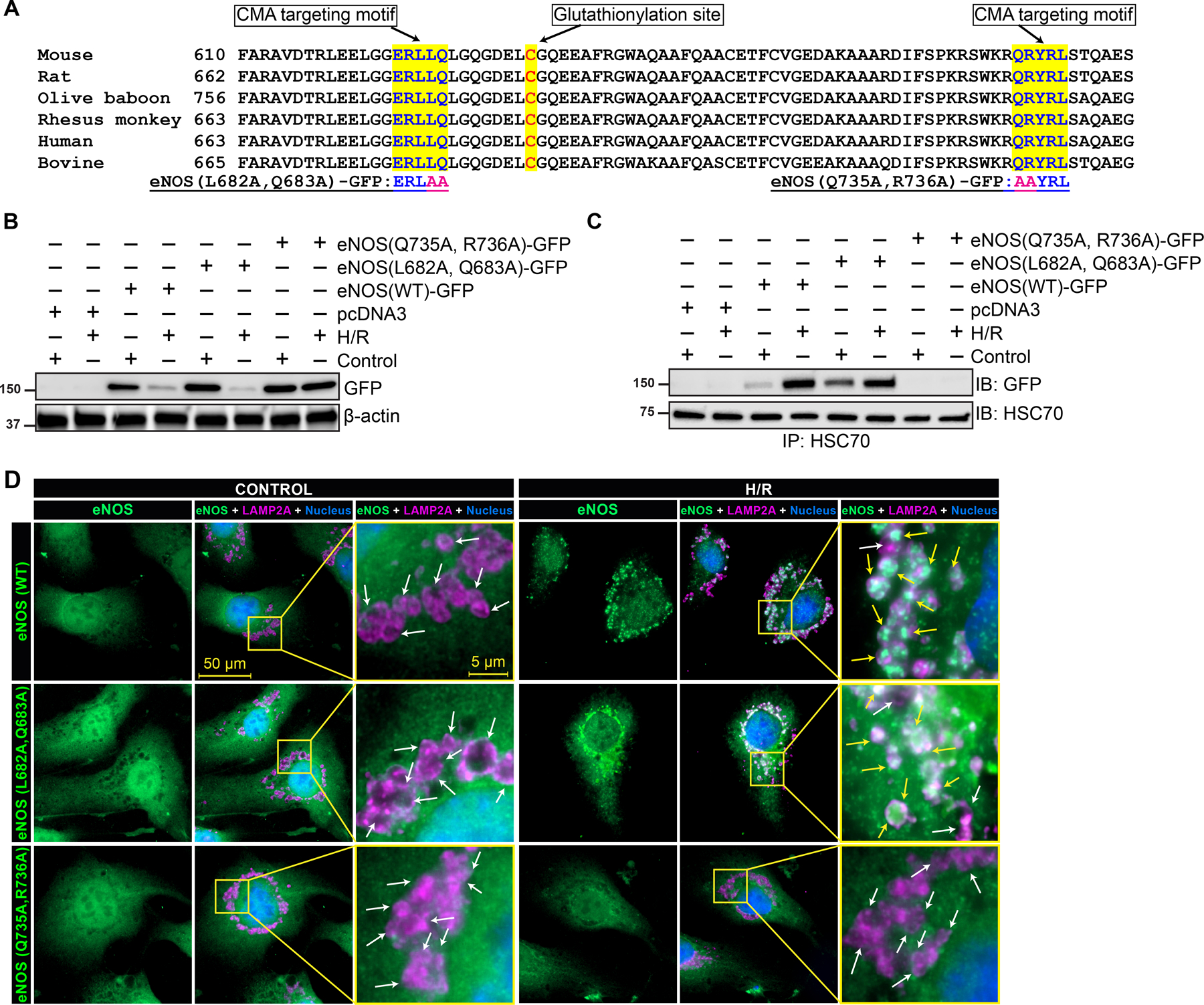

We analyzed bovine eNOS sequence for KFERQ-like motif using KFERQ finder 15. The search revealed the presence of two KFERQ like motifs in proximity to Cys691, 679ERLLQ683 and 735QRYRL739 (Fig 4A). Since, glutathionylation is reported to enhance solvent accessibility by exposing the site 35, 36, we selected the KFERQ-like pentapeptide motif located at 679 and 735 and mutated these residues by site directed mutagenesis. Previous studies have shown that mutation of amino acid flanking Q in the pentapeptide was sufficient to disrupt HSC70 binding 26, 37. Hence, we generated eNOS(L682A, Q683A)-GFP and eNOS(Q735A, R736A)-GFP by site directed mutagenesis and determined the ability of the mutant to bind to HSC70 and its accumulation in LAMP2A vesicles. HCAECs were transfected with pcDNA3-eNOS(WT)-GFP, pcDNA3-eNOS(L682A, Q683A)-GFP and pcDNA3-eNOS(Q735A, R736A)-GFP and exposed to H/R. We used GFP-tag to determine the level of overexpressed WT or mutant eNOS. Both eNOS(WT)-GFP and eNOS(L682A, Q683A)-GFP were degraded by H/R. But disruption of the 735QRYRL739 motif resulted in the blockade of eNOS degradation by H/R (Fig 4B). Next, we determined the ability of mutated eNOS to interact with HSC70 by co-immunoprecipitation. Association of eNOS(WT)-GFP with HSC70 was induced in H/R-treated HCAECs. While the association of eNOS was not affected by L682A-Q683A mutation, eNOS(Q735A, R736A)-GFP failed to interact with HSC70 (Fig 4C). Taken together, the results shown in Fig. 4A & B demonstrate that the motif 735QRYRL739 in SG-eNOS is essential for its interaction with HSC70 and degradation by CMA. To further confirm the role of the 735QRYRL739 motif in eNOS degradation by CMA, we visualized localization of eNOS mutants using anti-GFP antibodies in pcDNA3-eNOS(WT)-GFP, pcDNA3-eNOS(L682A, Q683A)-GFP or pcDNA3-eNOS(Q735A, R736A)-GFP transfected HCAECs. Fig 4D shows the accumulation of eNOS(WT)-GFP and eNOS(L682A, Q683A) in LAMP2A vesicles in H/R-treated cells. Interestingly, eNOS(Q735A, R736A)-GFP did not localize in LAMP2A vesicles. Therefore, we concluded that glutathionylation of Cys691 in eNOS during H/R exposes 735QRYRL739 motif for interaction with HSC70, which shuttles eNOS to autophagosomes and facilitates its degradation.

Figure 4. Mutating KFERQ-like motif of eNOS prevents its association with HSC70 and accumulation into LAMP2A vesicles.

Analysis of the amino acid sequence of eNOS from mouse, rat, olive baboon, rhesus monkey, human and bovine species revealed the presence two canonical CMA target motifs proximate to the glutathionylation site. The analysis also showed that both the motif and glutathionylation sites are conserved across the species (A). Mutated residues are indicated at the bottom of the panel. pcDNA3 constructs coding eNOS-GFP, eNOS(L682A, Q683A)-GFP or eNOS(Q735A, R736A)-GFP were transfected to HCAECs and exposed subjected to H/R. Cell lysates were analyzed for expression of eNOS-GFP and its mutants by Western blotting using anti-GFP antibodies (B). An equal amount of protein from cell lysates was immunoprecipitated using anti-HSC70 antibodies and associated eNOS was detected by anti-GFP antibodies (C). (D) Immunofluorescence microscopy of HCAECs transfected with eNOS-GFP, eNOS(L682A, Q683A)-GFP or eNOS(Q735A, R736A)-GFP, exposed to H/R (16/2h), stained for LAMP2A and GFP, white arrow shows LAMP2A vesicles and yellow arrows points to eNOS in LAMP2A lysosomal bodies.

Deglutathionylation of SG-eNOS by thiol reductants inhibits CMA and regenerates eNOS that restores NO production and improves myocardial perfusion in I/R.

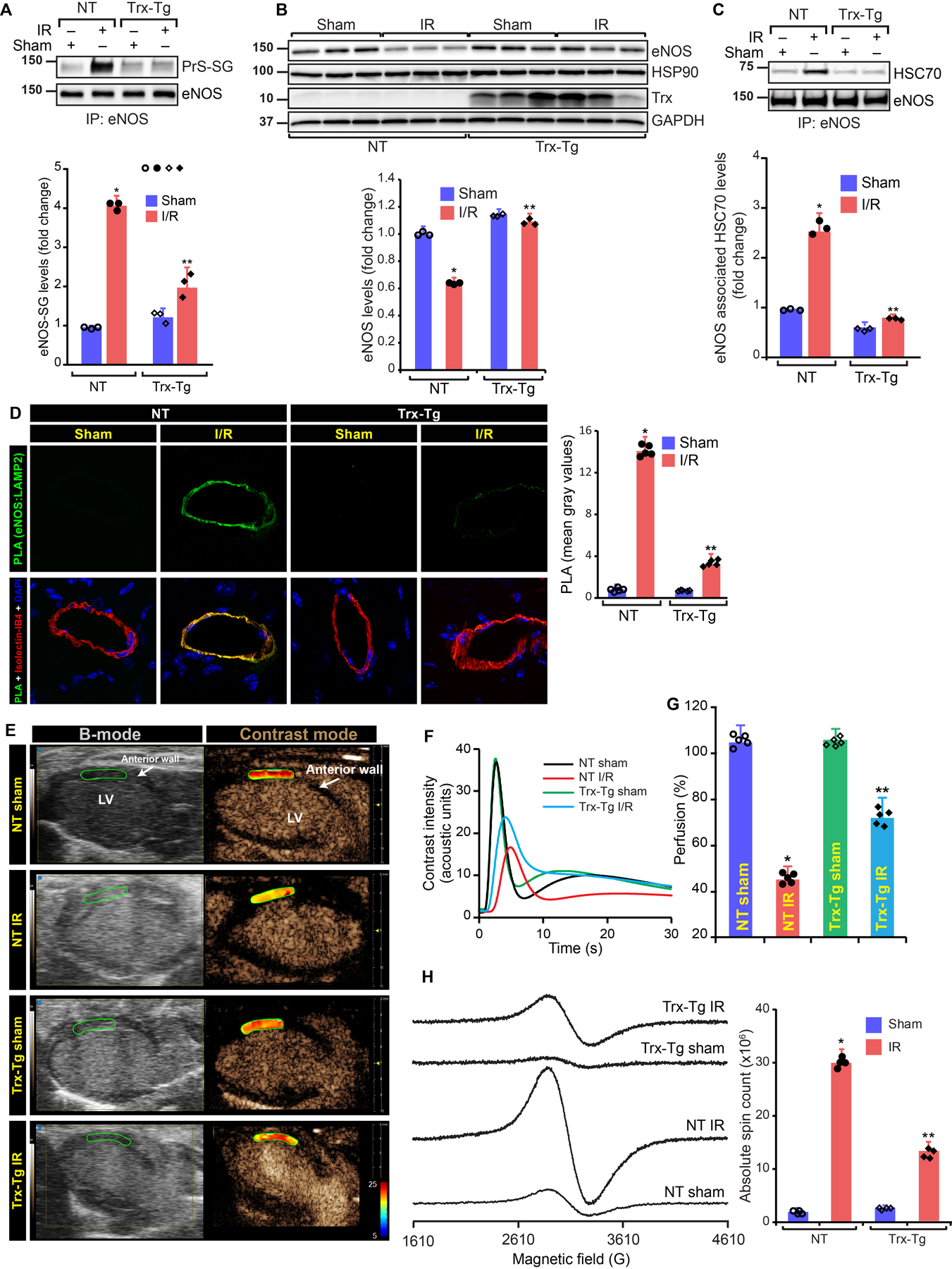

We determined eNOS CMA in I/R in the heart from non-transgenic (NT) or Trx-Tg mice. NT mice subjected to I/R had statistically significant increase (P=000124, 2-Way ANOVA) in SG-eNOS in the infarcted myocardium (Fig 5A). In contrast, Trx-Tg mice had statistically significantly decreased levels (P=0.010958, 2-Way ANOVA) of SG-eNOS (Fig 5A). Additionally, NT mice subjected to I/R had significant loss of eNOS protein in the infarcted area (Fig 5B). However, Trx-Tg mice exposed to I/R had undiminished levels of eNOS contrary to NT mice (Fig 5B). Since NT mice in I/R had significant SG-eNOS compared to Trx-Tg mice, we reasoned that HSC70 would interact with SG-eNOS in I/R in NT mice, but this interaction should be absent in Trx-Tg mice due to deglutathionylation of SG-eNOS. As shown in Fig 5C, significant level of HSC70 was co-immunoprecipitated with eNOS in infarcted hearts of NT mice (P=0.000711, 2-Way ANOVA), but not in Trx-Tg mice suggesting that increased levels of Trx in Trx-Tg mice prevents eNOS glutathionylation and consequently prevents eNOS-HSC70 association. We performed PLA to visualize co-localization of LAMP2A and eNOS in mouse heart sections following I/R to establish whether eNOS autophagy in vivo is the major mechanism of loss of NO in I/R. As presented in Fig 5D, there was a strong and statistically significant proximity count (P=0.000000001, 2-Way ANOVA) of eNOS and LAMP2A in I/R sections in the infarcted area of heart in NT mice, but not in sections from sham animals in endothelial cells. In contrast, there were no PLA signals in sections from Trx-Tg mice in I/R indicating that CMA of eNOS is a major mechanism of loss of NO production in I/R in vivo. However, Trx-Tg mice that underwent I/R did not show the presence of HSC70 or LAMP2A in association with eNOS (Fig 5D, upper right panels). Because eNOS remains functional in I/R in Trx-Tg mice, we determined whether preservation of eNOS function in I/R would result in improved myocardial perfusion using contrast echocardiography. As shown in Fig 5E–G, there was a statistically significant decrease in myocardial perfusion index in NT mice in I/R (P=00014802, 2-Way ANOVA); however, the perfusion index in the Trx-Tg mice remained comparable to untreated mice in I/R, indicating restoration of proper myocardial perfusion in I/R in Trx-Tg mice. Additionally, we evaluated myocardial apoptosis of entire infarcted tissue in I/R using an EPR-based modified method20. We found that Trx-Tg mice had statistically significantly lesser binding (P=0.000000000019179, 2-Way ANOVA) of paramagnetic iron-conjugated annexin-V that shows decreased apoptosis in I/R compared to NT mice (Fig 5H).

Figure 5. Overexpression of human Trx in mice (Trx-Tg) prevents eNOS glutathionylation, rescues eNOS expression and inhibits eNOS CMA in I/R and protect myocardium from IR-induced hypoperfusion and apoptosis.

A, Immunoblot of eNOS immunoprecipitates from derivatized tissue lysate using anti-GSH antibodies and eNOS immunoprecipitates from controls. Fold change in the level of eNOS glutathionylation, (n=3) (P=000124, 2-Way ANOVA); B, Immunoblot of left ventricle lysate. Fold change in eNOS (n=3), (P=0.010958, 2-Way ANOVA); C, Immunoblot of HSC70 in eNOS immunoprecipitates from heart. Fold change in eNOS associated HSC70. (n=3), (P=0.000711, 2-Way ANOVA); D, PLA using anti-eNOS and anti-LAMP2A. Green foci-proximity signals of eNOS-LAMP2A were counted and plotted, (n=5); E, B-mode/contrast mode images of the wall below ligation from long-axis view of NT and Trx-Tg mice. Heat map shows the level of perfusion. F, Contrast intensities in the left ventricle (LV) anterior wall was quantitated and plotted over time, (n=5); G, Perfusion index was calculated and plotted as a bar graph. Values are means ± SD (n=5). **P=00014802, 2-Way ANOVA) versus NT I/R; H, EPR spectra of iron bound to annexin-V in sham or I/R heart of NT or Trx-Tg mice. Graph shows an absolute spin count of Fe-bound to Annexin-V. Values are means ± SD (n=4). **P=0.000000000019179, 2-Way ANOVA versus NT I/R.

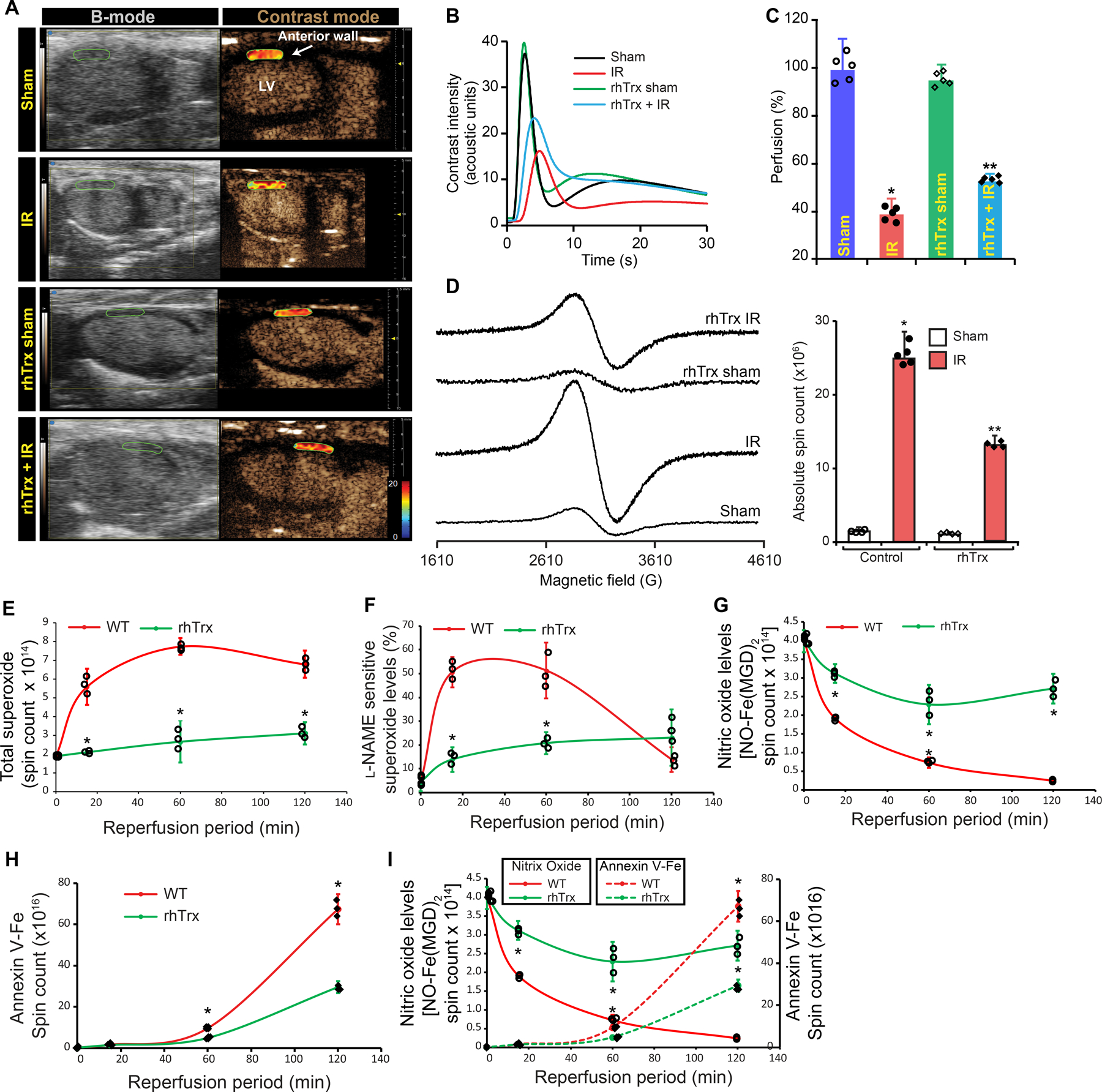

Injection of rhTrx at the beginning of reperfusion ameliorates MI by decreasing L-NAME sensitive and L-NAME resistant O2•− generation in a temporal manner.

We injected rhTrx to WT mice and determined myocardial perfusion following I/R to demonstrate if pharmacological administration of rhTrx would protect against impaired perfusion due to better availability of NO, as SG-eNOS is deglutathionylated by Trx 18. rhTrx is known to be internalized by cells, when injected to mice or applied to cultured cells 38–41. As shown in Figs 6A–C, significant improvement of myocardial perfusion was observed in rhTrx-injected mice, as demonstrated by significant increase in perfusion index in rhTrx-injected mice in I/R (P=0.00000161, NT-I/R vs rhTrx-I/R, ANOVA). We further, determined myocardial apoptosis in rhTrx-injected mice in I/R. As demonstrated in Fig 6D, significant decrease in myocardial apoptosis of entire infarct area was observed (P=0.000000001, 2-Way ANOVA). Collectively, these data demonstrate the translational efficacy of rhTrx in amelioration of impaired myocardial perfusion in I/R brought about by improved NO generation due to deglutathionylation of SG-eNOS. We also assessed the time course of O2•− generation starting from the beginning of reperfusion until 2-hours following reperfusion. As shown in Fig 6E, the maximal amount of O2•− was produced within first one hour of reperfusion, followed by a gradual decline, but still at a higher level at the end of 2-hour reperfusion. In contrast, mice treated with rhTrx had significantly lower levels of O2•− at a linear rate (Fig 6E). However, L-NAME-resistant O2•− was acutely increased in the first 20 minutes of reperfusion and began to rapidly decline after 1-hr following reperfusion, but rhTrx treated mice had significantly lower O2•− levels (Fig 6F). NO production was decreased slowly within first 70 minutes of reperfusion in rhTrx treated mice (Fig 6G). In contrast, untreated mice showed rapid decline in NO production beyond 70 minutes of reperfusion with almost complete loss of NO by 2 hours. Consistent with the disappearance of NO after 1-hr reperfusion, there was a sharp rise in myocardial apoptosis (Fig 6H). However, myocardial apoptosis was significantly lower in rhTrx treated mice (Fig 6H). When we superimposed the rate of NO production with myocardial apoptosis (Fig 6I), the data revealed that loss of NO occurs due to eNOS autophagy following about 70 minutes of reperfusion with concomitant increase in myocardial apoptosis that increased after 70 minutes of reperfusion without rhTrx treatment.

Figure 6. Administration of rhTrx prevents I/R-induced myocardial hypoperfusion and tissue apoptosis by preserving eNOS function.

A, C57BL6 mice were injected with 3 dosages of rhTrx via tail vein (2.5 mg/kg) at 48-hour intervals for three consecutive days. 12 hours after the third injection, mice were subjected to sham or myocardial IR surgery. B-mode/contrast mode images were acquired in the wall from long-axis view of control and rhTrx-injected mice. Heat map shows the level of perfusion; B, Contrast intensities in the left ventricle (LV) anterior wall below ligation was quantitated and plotted over time, (n=5); C, Perfusion index was calculated and plotted as a bar graph. Values are means ± SD (n=5). P=0.00000161, NT-I/R vs rhTrx-I/R, ANOVA; D, EPR spectra of paramagnetic iron bound to annexin-V in sham or I/R myocardium of control or rhTrx-injected mice. Graph shows an absolute spin count of Fe-bound to Annexin-V. Values are means ± SD (n=4), P=0.000000001, 2-Way ANOVA; E, Mice were subjected to sham or 30 min myocardial ischemia followed by 15 minutes to 2 hours reperfusion. At the end of reperfusion period, heart was excised, cannulated and perfused with 1X PSS. The infarcted tissue was excised and incubated with 100 µM CMH in presence of 25 µM desferoxamine and 2.5 µM diethyldithiocarbamate at 37°C. Superoxide generated by infarcted tissue was detected as paramagnetic nitroxide radical (CM*) using Bruker EMX Micro spectrometer. To determine protective function of rhTrx, 2.5 mg/kg reduced-rhTrx was injected to mice at the beginning of reperfusion. To inhibit eNOS-based superoxide formation, samples were pretreated with 100 µm L-NAME for 10 min and then used in superoxide quantification. EPR spectra were simulated with nitroxide radical-EPR signals and absolute spin counts were obtained using Xenon 1.2 software and plotted as a graph. F, Superoxide formed from dysfunctional eNOS was calculated by subtracting L-NAME sensitive superoxide counts from total spin counts and plotted as percentage of the total superoxide. Values are means ± SD (n = 3)*, p =0.00000628 vs WT (ANOVA); G, At the end of reperfusion period, heart was excised, cannulated and perfused with annexin-Ve-Fe complex as described in Methods. The infarcted tissue was excised, and tissue bound annexin-V was quantified by measuring annexin-V conjugated iron in EPR. Annexin V-paramagnetic iron spin count was calculated from EPR spectra and plotted as bar graph. Values are mean ± SEM (n = 3). *, P=00600 vs. WT (ANOVA); H, the infarcted tissue was excised and incubated 10 µM ACh and generated NO was detected by EPR spectrometry using Fe-(MGD)2 as described in Materials and Methods. EPR spectra were simulated with NO-Fe(MGD)2 radical and absolute spin counts were obtained using Xenon 1.2 software and plotted as a graph. Values are means ± SD (n = 3), P=0.001374 vs. WT; I, Line graphs from panel G and H are presented together with dual axis to explain critical time point of recovery or growth of MI.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we have shown that eNOS protein is lost by CMA when it is glutathionylated in reperfusion injury. We have provided evidence that SG-eNOS is degraded via CMA that causes irreversible loss of eNOS resulting in severe deficiency of NO production. Glutathionylation of Cys691 exposes the 735QRYRL739 motif that interacts with chaperone protein HSC70, which transports SG-eNOS to the autophagosomes for degradation by lysosomal proteases (Fig XI). Additionally, we found that in the absence of SG-eNOS autophagy, the generation of O2•− remains unabated with failure of eNOS to produce NO. We further found that agents that deglutathionylate eNOS are effective in its rescue from irreversible degradation in I/R resulting in restoration of NO production and better perfusion of myocardial tissue. Our study also demonstrates the efficacy of rhTrx in a translational model to alleviate poor myocardial perfusion resulting from I/R due to better availability of NO. Collectively, our study demonstrated that loss of eNOS via autophagy is a major mechanism of irreversible loss of NO production in reperfused myocardium in I/R. Prompt deglutathionylation by rhTrx or thiols at the beginning or the reperfusion period could provide significant benefits against reperfusion injury with decreased MI. Although we found significant glutathionylation of eNOS in H/R, cells in normoxia showed basal level of glutathionylated eNOS. Metabolically active cells always generate a basal level of ROS that could glutathionylate eNOS and which is expected to be deglutathionylated by endogenous systems such as glutaredoxin or thioredoxin. Therefore, SG-eNOS and eNOS equilibrium may be dynamically regulated in the physiological state. However, in a pathophysiological setting such as I/R, overwhelming levels of ROS may exhaust the endogenous deglutathionylating systems and additional reducing power is needed to mitigate high levels of glutathionylated proteins such as eNOS. Thus, physiological basal glutathionylation is dynamically regulated by deglutathionylation; however, pathological glutathionylation outcompetes cellular redox systems for deglutathionylation and therefore, it is necessary for the regulated system of CMA to eliminate deleterious SG-eNOS.

Our data demonstrate that ROS are generated at the beginning of reperfusion that causes eNOS glutathionylation, which uncouples eNOS resulting in further increase in O2•− and could produce peroxynitrite (OONO-) by its interaction with O2•−. Further, loss of SG-eNOS by CMA with irreversible loss of eNOS and myocyte necrosis occurs, resulting unsalvageable myocardium with significant increase in MI. Intervention with Trx or other deglutathionylating agents or a combination of antioxidants with deglutathionylating agents within 3-hour window is likely to regenerate functional eNOS, re-establishes myocardial perfusion resulting in decreased MI size with increased myocardial salvage. In support of this hypothesis, it has been reported that patients undergoing cardiopulmonary bypass showed increased O2•− production after reperfusion42 and S-glutathionylation of eNOS was found to be the major mechanism of eNOS uncoupling following bypass surgery42. eNOS activity was significantly decreased in these patients, and neither Nox2 inhibition nor BH4 supplementation improved NO production42, suggesting additional mechanisms are involved in loss of eNOS activity in I/R. Systemic administration of rhTrx via intraperitoneal injection has been shown to be taken up by cardiomyocytes in mice40. There are no adverse report of injected rhTrx in any animal systems. Therefore, rhTrx could be used as a therapeutic intervention to counter reperfusion injury and restore NO production in reperfused myocardium. As shown in Fig 5A–B the level of O2•− was rapidly increased within first 5–20 minutes in contrast to an earlier study reporting increased hydroxyl radicals in 1–2 minutes 43. However, in this study the investigators used an ex vivo isolated rat heart model in contrast to our in vivo I/R model. We measured the O2•− only in the infarcted area. Thus, there is a significant difference in these studies with respect to generation and measurement of O2•−. Nonetheless, both studies show very early generation of O2•− that is expected to dismutate to H2O2 and further increase in hydroxyl radicals. We have shown that 70 minutes after reperfusion, there is an inverse correlation of increased apoptosis with loss of NO (Fig 5G, H, I). This inverse correlation was disrupted with treatment of mice with rhTrx, which is known to deglutathionylate SG-eNOS 18. We have also shown that deglutathionylation by Trx is independent of Grx1/GSH system18. Following a gradual decline in NO production in reperfusion in rhTrx treated mice, the levels of NO did not decrease after 70 minutes concomitant with significantly lower potential of cells committed to myocardial apoptosis, suggesting deglutathionylation eNOS after about 70 minutes of reperfusion with rhTrx, which restored NO production (Fig 5H and I).

Generation of O2•− by SG-eNOS is not only damaging to cardiovascular tissue, but also causes NO depletion by interacting with NO and producing highly toxic OONO- that could cause further damage to all macromolecules 12. Further, OONO- is known to inhibit mitochondrial respiration and causes mitochondrial permeability transition pore opening, which is a critical target of for cardioprotection by ischemic preconditioning3. Therefore, it is essential to inhibit this chain reaction to decrease oxidant load in the vascular tissue. CMA of SG-eNOS terminates the O2•− generating system in the endothelial cells preventing further tissue damage and depletion of NO. We showed that prolonged retention of SG-eNOS in the cells induces its CMA. This retention time allows cellular redox systems to deglutathionylate SG-eNOS that would restore NO generating function of eNOS. However, since prolonged retention could cause severe oxidative damage, it is necessary to eliminate SG-eNOS by autophagy if cellular reducing systems are ineffective in deglutathionylation of SG-eNOS. Consistent with this reasoning we found that prolonged retention of SG-eNOS (~16 hours) induces its CMA. Since recovery of cells in room air following exposure to H/R did not improve NO production, we speculated that the redox system might have been completely exhausted of reducing equivalents needed for deglutathionylation. Therefore, we reason that externally added reducing systems should recover eNOS by deglutathionylation. Consistent with this reasoning the reduced Trx or NAC deglutathionylated SG-eNOS and restored NO generating function of eNOS with inhibition of eNOS autophagy.

Nitric oxide and NO donors prevent coronary spasm and collateral blood flow and reduce myocardial oxygen demand44. eNOS deficient mice develop severe LV dysfunction, but overexpression of eNOS in mice attenuate LV dysfunction in MI indicating beneficial role of NO in heart failure. However, studies failed to show consistent benefit of NO donors45, 46. Our study demonstrates that eNOS CMA is a new mechanism of irreversible loss of NO in I/R, that prevents SG-eNOS mediated O2•− production. Further, our finding explains progressive loss of myocardium due to enhanced apoptosis/necrosis of myocytes due to complete loss of NO generating system in late reperfusion period. Consistent with the loss of eNOS via CMA, the level of eNOS-mediated O2•− was significantly decreased with complete loss of L-NAME-sensitive O2•− at about 120 minutes (Fig 6I). However, at this time point the level of total O2•− levels were significantly higher, indicating other sources of O2•− generation such as activated mitochondria or NADPH oxidases. We believe that CMA of SG-eNOS occurs during 2–6 hours resulting myocardial necrosis and complete loss of viable heart muscle6. Intervention with Trx or other deglutathionylating agents very early during the reperfusion period could potentially regenerate functional eNOS and decrease oxidant load and will improve myocardial salvage during reperfusion period.

Supplementary Material

NOVELTY AND SIGNIFICANCE.

What Is known?

Restoration of blood flow following removal of vascular occlusion causes reperfusion injury.

Endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), is known to generate toxic superoxide anion during reperfusion that may react with and decrease available nitric oxide.

During reperfusion injury, eNOS is oxidatively conjugated to glutathione forming S-glutathionylated eNOS, which produces superoxide anion.

The fate of glutathionylated-eNOS (SG-eNOS), and how long the superoxide is produced in the myocardium is unclear.

What New Information Does this article Contribute?

SG-eNOS is irreversibly lost after reperfusion in a mouse model of coronary ischemia-reperfusion injury.

Prolonged retention of SG-eNOS induces an association with HSC70 and LAMP2A that promotes its degradation via chaperone-mediated autophagy (CMA).

SG-eNOS is targeted by HSC70 chaperone via its interaction with glutathionylated-cysteine 691 and glutathionylation of cysteine 691 residues expose the 735QRYRL739 motif for interaction with HSC70, and consequent transportation to LAMP2A vesicle, where it is degraded by lysosomal proteases.

Deglutathionylation of SG-eNOS by recombinant human thioredoxin (rhTrx) or N-Acetyl-L-Cysteine (NAC) restores NO production, resulting in decreases myocardial infarct size.

Endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) produces nitric oxide (NO) that maintains arterial blood flow. During reperfusion of an ischemic heart, eNOS is S-glutathionylated (SG-eNOS) producing superoxide anion instead of NO. eNOS activity is significantly decreased in coronary bypass patients, and neither Nox2 inhibition nor BH4 supplementation improves NO production. In this study, we found that prolonged retention of SG-eNOS promotes its degradation causing irreversible loss of eNOS. We further found that only SG-eNOS, but not functional eNOS interacts with chaperone protein HSC70 via glutathionylation of cysteine 691 residue exposing the 735QRYRL739 motif to interaction with HSC70, and consequent transportation to a LAMP2A vesicle, where it is degraded by lysosomal proteases. However, deglutathionylation of SG-eNOS by human recombinant thioredoxin or N-acetyl-L-cysteine inhibits CMA and restores NO production and decreases myocardial infarction size. In this study, we demonstrate that loss of eNOS during reperfusion can be reversed by deglutathionylating agents and subsequently protect against loss of myocardial tissue due to reperfusion injury.

SOURCE OF FUNDING

Funding for this study is provided by National Heart Lung and Blood Institute of National Institutes of Health in R01 HL107885, R01HL132953 and R01HL 144610 (KCD).

NONSTANDARD ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS:

- 3-MA

3-methyl adenine

- ATG5

Autophagy-related 5

- BCNU

1,3-Bis (2-chloethyl)-1 nitrosourea

- CMA

Chaperone-mediated autophagy

- DMPO

5,5-Dimethyl-1-Pyrroline-N-Oxide

- eNOS

Endothelial nitric oxide synthase

- EPR

Electron spin resonance

- GSH

γ-L-Glutamyl-L-cysteinyl-glycine

- H/R

Hypoxia/Reoxygenation

- HCAEC

Human coronary artery endothelial cells

- HSC70

Heat-shock cognate protein, 71 kDa

- I/R

Ischemia/Reperfusion

- IP

Immunoprecipitation

- LAMP-2

Lysosome-associated membrane protein 2

- L-NAME

Nω-Nitro-L-arginine methyl ester hydrochloride

- LNZ

Lansoprazole

- NAC

N-acetyl-L-cysteine

- NO

Nitric oxide

- NOS

Nitric oxide synthase

- NT

Non-transgenic

- PEG-SOD

polyethylene glycol-superoxide dismutase

- PLA

Proximity ligation assay

- rhTrx

Recombinant human thioredoxin

- SG-eNOS

S-glutathionylated eNOS

- Trx-Tg

Thioredoxin transgenic mouse strain

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This article is published in its accepted form. It has not been copyedited and has not appeared in an issue of the journal. Preparation for inclusion in an issue of Circulation Research involves copyediting, typesetting, proofreading, and author review, which may lead to differences between this accepted version of the manuscript and the final, published version.

COMPETEING INTERESTS

Authors declare no competing interests.

DISCLOSURES

The authors have nothing to disclose

REFERENCES

- 1.Fordyce CB, Gersh BJ, Stone GW, Granger CB. Novel therapeutics in myocardial infarction: Targeting microvascular dysfunction and reperfusion injury. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2015;36:605–616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Griffiths K, Lee JJ, Frenneaux MP, Feelisch M, Madhani M. Nitrite and myocardial ischaemia reperfusion injury. Where are we now? Pharmacol Ther 2021;223:107819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Otani H The role of nitric oxide in myocardial repair and remodeling. Antioxid Redox Signal 2009;11:1913–1928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yellon DM, Hausenloy DJ. Myocardial reperfusion injury. N Engl J Med 2007;357:1121–1135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prasad A, Gersh BJ. Management of microvascular dysfunction and reperfusion injury. Heart 2005;91:1530–1532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prasad A, Stone GW, Holmes DR, Gersh B. Reperfusion injury, microvascular dysfunction, and cardioprotection: The “dark side” of reperfusion. Circulation 2009;120:2105–2112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carnicer R, Crabtree MJ, Sivakumaran V, Casadei B, Kass DA. Nitric oxide synthases in heart failure. Antioxid Redox Signal 2013;18:1078–1099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giraldez RR, Panda A, Xia Y, Sanders SP, Zweier JL. Decreased nitric-oxide synthase activity causes impaired endothelium-dependent relaxation in the postischemic heart. J Biol Chem 1997;272:21420–21426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen CA, Wang TY, Varadharaj S, Reyes LA, Hemann C, Talukder MA, Chen YR, Druhan LJ, Zweier JL. S-glutathionylation uncouples enos and regulates its cellular and vascular function. Nature 2010;468:1115–1118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen CA, De Pascali F, Basye A, Hemann C, Zweier JL. Redox modulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase by glutaredoxin-1 through reversible oxidative post-translational modification. Biochemistry 2013;52:6712–6723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crabtree MJ, Brixey R, Batchelor H, Hale AB, Channon KM. Integrated redox sensor and effector functions for tetrahydrobiopterin- and glutathionylation-dependent endothelial nitric-oxide synthase uncoupling. J Biol Chem 2013;288:561–569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Speckmann B, Steinbrenner H, Grune T, Klotz LO. Peroxynitrite: From interception to signaling. Arch Biochem Biophys 2016;595:153–160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Das KC. Thioredoxin-deficient mice, a novel phenotype sensitive to ambient air and hypersensitive to hyperoxia-induced lung injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2015;308:L429–442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sowa G, Liu J, Papapetropoulos A, Rex-Haffner M, Hughes TE, Sessa WC. Trafficking of endothelial nitric-oxide synthase in living cells. Quantitative evidence supporting the role of palmitoylation as a kinetic trapping mechanism limiting membrane diffusion. J Biol Chem 1999;274:22524–22531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kirchner P, Bourdenx M, Madrigal-Matute J, Tiano S, Diaz A, Bartholdy BA, Will B, Cuervo AM. Proteome-wide analysis of chaperone-mediated autophagy targeting motifs. PLoS Biol 2019;17:e3000301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martinet W, Timmermans JP, De Meyer GR. Methods to assess autophagy in situ--transmission electron microscopy versus immunohistochemistry. Methods Enzymol 2014;543:89–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hilgers RH, Kundumani-Sridharan V, Subramani J, Chen LC, Cuello LG, Rusch NJ, Das KC. Thioredoxin reverses age-related hypertension by chronically improving vascular redox and restoring enos function. Sci Transl Med 2017;9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Subramani J, Kundumani-Sridharan V, Hilgers RH, Owens C, Das KC. Thioredoxin uses a gsh-independent route to deglutathionylate endothelial nitric-oxide synthase and protect against myocardial infarction. J Biol Chem 2016;291:23374–23389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Subramani J, Kundumani-Sridharan V, Das KC. Thioredoxin protects mitochondrial structure, function and biogenesis in myocardial ischemia-reperfusion via redox-dependent activation of akt-creb- pgc1alpha pathway in aged mice. Aging (Albany NY) 2020;12:19809–19827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fabisiak JP, Borisenko GG, Kagan VE. Quantitative method of measuring phosphatidylserine externalization during apoptosis using electron paramagnetic resonance (epr) spectroscopy and annexin-conjugated iron. Methods Mol Biol 2014;1105:613–621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee DH, Goldberg AL. Proteasome inhibitors: Valuable new tools for cell biologists. Trends Cell Biol 1998;8:397–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu W, Baker SS, Trinidad J, Burlingame AL, Baker RD, Forte JG, Virtuoso LP, Egilmez NK, Zhu L. Inhibition of lysosomal enzyme activities by proton pump inhibitors. J Gastroenterol 2013;48:1343–1352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seglen PO, Gordon PB. 3-methyladenine: Specific inhibitor of autophagic/lysosomal protein degradation in isolated rat hepatocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1982;79:1889–1892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuma A, Hatano M, Matsui M, Yamamoto A, Nakaya H, Yoshimori T, Ohsumi Y, Tokuhisa T, Mizushima N. The role of autophagy during the early neonatal starvation period. Nature 2004;432:1032–1036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaushik S, Cuervo AM. Chaperone-mediated autophagy: A unique way to enter the lysosome world. Trends Cell Biol 2012;22:407–417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cuervo AM, Dice JF. A receptor for the selective uptake and degradation of proteins by lysosomes. Science 1996;273:501–503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cuervo AM, Dice JF. Unique properties of lamp2a compared to other lamp2 isoforms. J Cell Sci 2000;113 Pt 24:4441–4450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang Y, Qiao M, Mieyal JJ, Asmis LM, Asmis R. Molecular mechanism of glutathione-mediated protection from oxidized low-density lipoprotein-induced cell injury in human macrophages: Role of glutathione reductase and glutaredoxin. Free Radic Biol Med 2006;41:775–785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gallogly MM, Mieyal JJ. Mechanisms of reversible protein glutathionylation in redox signaling and oxidative stress. Curr Opin Pharmacol 2007;7:381–391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen CA, Lin CH, Druhan LJ, Wang TY, Chen YR, Zweier JL. Superoxide induces endothelial nitric-oxide synthase protein thiyl radical formation, a novel mechanism regulating enos function and coupling. J Biol Chem 2011;286:29098–29107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kang PT, Zhang L, Chen CL, Chen J, Green KB, Chen YR. Protein thiyl radical mediates s-glutathionylation of complex i. Free Radic Biol Med 2012;53:962–973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen Y, Azad MB, Gibson SB. Superoxide is the major reactive oxygen species regulating autophagy. Cell Death Differ 2009;16:1040–1052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ghezzi P Protein glutathionylation in health and disease. Biochim Biophys Acta 2013;1830:3165–3172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ghezzi P, Romines B, Fratelli M, Eberini I, Gianazza E, Casagrande S, Laragione T, Mengozzi M, Herzenberg LA, Herzenberg LA. Protein glutathionylation: Coupling and uncoupling of glutathione to protein thiol groups in lymphocytes under oxidative stress and hiv infection. Mol Immunol 2002;38:773–780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen J, Chen CL, Rawale S, Chen CA, Zweier JL, Kaumaya PT, Chen YR. Peptide-based antibodies against glutathione-binding domains suppress superoxide production mediated by mitochondrial complex i. J Biol Chem 2010;285:3168–3180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Garcin ED, Bruns CM, Lloyd SJ, Hosfield DJ, Tiso M, Gachhui R, Stuehr DJ, Tainer JA, Getzoff ED. Structural basis for isozyme-specific regulation of electron transfer in nitric-oxide synthase. J Biol Chem 2004;279:37918–37927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Valdor R, Mocholi E, Botbol Y, Guerrero-Ros I, Chandra D, Koga H, Gravekamp C, Cuervo AM, Macian F. Chaperone-mediated autophagy regulates t cell responses through targeted degradation of negative regulators of t cell activation. Nat Immunol 2014;15:1046–1054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kundumani-Sridharan V, Subramani J, Das KC. Thioredoxin activates mkk4-nfkappab pathway in a redox-dependent manner to control manganese superoxide dismutase gene expression in endothelial cells. J Biol Chem 2015;290:17505–17519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Das KC, Lewis-Molock Y, White CW. Elevation of manganese superoxide dismutase gene expression by thioredoxin. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 1997;17:713–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tao L, Gao E, Bryan NS, Qu Y, Liu HR, Hu A, Christopher TA, Lopez BL, Yodoi J, Koch WJ, Feelisch M, Ma XL. Cardioprotective effects of thioredoxin in myocardial ischemia and reperfusion: Role of s-nitrosation [corrected]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2004;101:11471–11476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tao L, Gao E, Hu A, Coletti C, Wang Y, Christopher TA, Lopez BL, Koch W, Ma XL. Thioredoxin reduces post-ischemic myocardial apoptosis by reducing oxidative/nitrative stress. Br J Pharmacol 2006;149:311–318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jayaram R, Goodfellow N, Zhang MH, Reilly S, Crabtree M, De Silva R, Sayeed R, Casadei B. Molecular mechanisms of myocardial nitroso-redox imbalance during on-pump cardiac surgery. Lancet 2015;385 Suppl 1:S49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kramer JH, Arroyo CM, Dickens BF, Weglicki WB. Spin-trapping evidence that graded myocardial ischemia alters post-ischemic superoxide production. Free Radic Biol Med 1987;3:153–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sattur S, Brener SJ, Stone GW. Pharmacologic therapy for reducing myocardial infarct size in clinical trials: Failed and promising approaches. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther 2015;20:21–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jugdutt BI. Intravenous nitroglycerin unloading in acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol 1991;68:52D–63D [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Morris JL, Zaman AG, Smyllie JH, Cowan JC. Nitrates in myocardial infarction: Influence on infarct size, reperfusion, and ventricular remodelling. Br Heart J 1995;73:310–319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting this study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. An expanded Materials and Methods section can be found in Online Supplement.