Abstract

Background:

Alopecia areata (AA) is an autoimmune, nonscarring hair loss disorder with slightly greater prevalence in children than adults. Various treatment modalities exist; however, their evidence in pediatric AA patients is lacking.

Objective:

To evaluate the evidence of current treatment modalities for pediatric AA.

Methods:

We conducted a systematic review on the PubMed database in October 2019 for all published articles involving patients <18 years old. Articles discussing AA treatment in pediatric patients were included, as were articles discussing both pediatric and adult patients, if data on individual pediatric patients were available.

Results:

Inclusion criteria were met by 122 total reports discussing 1032 patients. Reports consisted of 2 randomized controlled trials, 4 prospective comparative cohorts, 83 case series, 2 case-control studies, and 31 case reports. Included articles assessed the use of aloe, apremilast, anthralin, anti-interferon gamma antibodies, botulinum toxin, corticosteroids, contact immunotherapies, cryotherapy, hydroxychloroquine, hypnotherapy, imiquimod, Janus kinase inhibitors, laser and light therapy, methotrexate, minoxidil, phototherapy, psychotherapy, prostaglandin analogs, sulfasalazine, topical calcineurin inhibitors, topical nitrogen mustard, and ustekinumab.

Limitations:

English-only articles with full texts were used. Manuscripts with adult and pediatric data were only incorporated if individual-level data for pediatric patients were provided. No meta-analysis was performed.

Conclusion:

Topical corticosteroids are the preferred first-line treatment for pediatric AA, as they hold the highest level of evidence, followed by contact immunotherapy. More clinical trials and comparative studies are needed to further guide management of pediatric AA and to promote the potential use of pre-existing, low-cost, and novel therapies, including Janus kinase inhibitors.

Keywords: alopecia areata, contact immunotherapy, corticosteroids, JAK inhibitors, pediatric, quality of life

Alopecia areata (AA) is a nonscarring hair loss disorder that affects up to 2% of the global population.1 It is estimated that nearly 80% of patients with limited, patchy AA spontaneously recover.2 AA is characterized by relapsing and remitting patches of hair loss that may progress to severe subtypes, such as alopecia totalis (AT), alopecia universalis (AU), or alopecia ophiasis (AO), often resulting in significant psychological detriment. The pediatric population is particularly susceptible to the psychosocial consequences of AA, thus, adequate treatment is critical to prevent further morbidity associated with this disease.3 Although there are currently no treatments for AA approved by the Food and Drug Administration, there are numerous off-label treatment options for adults with AA. Therapeutic options for children and adolescents are limited. This systematic review sought to evaluate available off-label therapies for the treatment of AA in patients younger than 18 years of age.

METHODS

A systematic review was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Supplemental Table I; available via Mendeley at https://doi.org/10.17632/s9rx4myvnn.1). Using the PubMed database, a search for all published peer-reviewed articles was performed using the following search terms: ‘‘alopecia’’ and ‘‘areata’’ or ‘‘totalis’’ or ‘‘universalis’’ or ‘‘ophiasis’’ and ‘‘treatment’’ or ‘‘therapy’’ or ‘‘medication’’ or ‘‘drug.’’

These records were screened using defined criteria for eligibility, which consisted of English articles discussing the direct study or report of treatment modalities for AA in humans younger than 18 years of age. References of included reports were examined and additional sources not identified initially were incorporated. Review articles, animal studies, articles evaluating treatments that are no longer manufactured worldwide, including alefacept, and articles with unavailable full text were excluded. Articles that reported on results for both pediatric and adult patients were only included if individual-level data for the pediatric patients were provided.

The results were then further classified by the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine 2011 Levels of Evidence (LoE): level 1 (systematic review of randomized controlled trials [RCTs] or high-quality randomized controlled trial), level 2 (lesser quality RCTor prospective cohort study), level 3 (case-control study, non-randomized controlled cohort or follow-up study), level 4 (case series), or level 5 (expert opinion, mechanism-based reasoning).

RESULTS

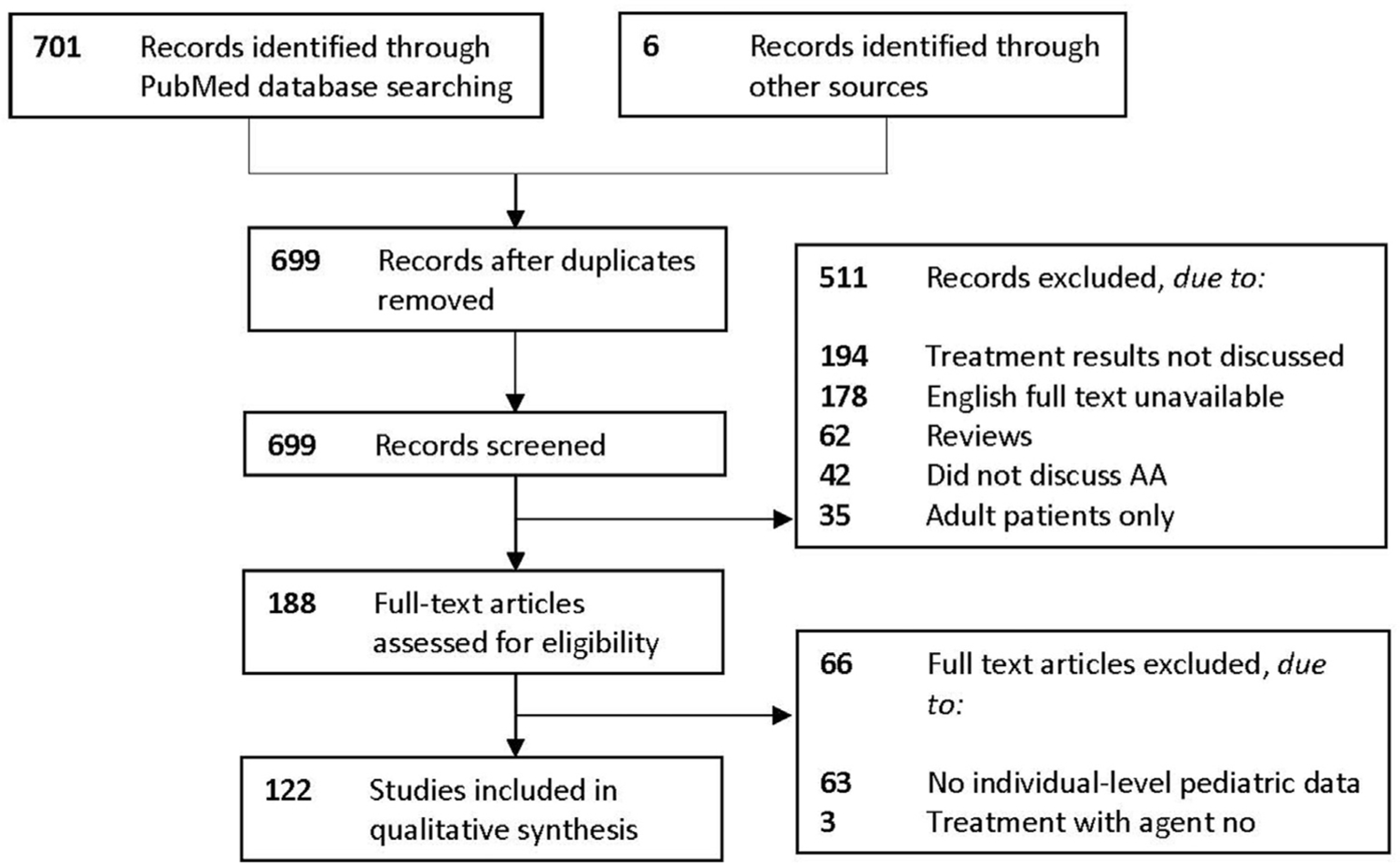

A total of 707 publications were retrieved, of which 122 reports were included (Fig 1). These reports consisted of 2 RCTs, 4 prospective comparative cohorts, 83 case series, 2 case-control studies, and 31 case reports. Included articles and results are summarized in Tables I to III.4–18

Fig 1.

PRISMA 2009 flow diagram illustrating a total of 707 publications retrieved, of which 122 reports were included. AA, Alopecia areata; PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses.

Table I.

Included studies evaluating topical and miscellaneous treatment of alopecia areata in pediatric patients

| First author | Year | Treatment | LoE | Study type | N | AA | AT | AU | AO | CR* | PR† | NR‡ | RR§ | SE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anthralin | ||||||||||||||

| Sardana19 | 2018 | Anthralin + leflunomide | 5 | Case report | 1 | - | - | - | 1 | 1 (100%) | - | - | NA | Itching, burning |

| Wu20 | 2018 | Anthralin | 4 | Case series | 37 | 24 | 8 | 3 | 2 | 12 (32%) | 15 (40%) | 5 (14%) | 16 (64%) | Irritation, LAD |

| Ozdemir21 | 2017 | Anthralin | 4 | Case series | 30 | 27 | 1 | 2 | - | 10 (33.3%) | 11 (36.7%) | 9 (30%) | 2 (9.5%) | Irritation, itching, LAD, hyperpigmentation, crusting, oozing, bullous eruption |

| Torchia22 | 2015 | Anthralin + TC | 5 | Case report | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | 1 (100%) | NA | LAD |

| Contact | ||||||||||||||

| Immunotherapy | ||||||||||||||

| Wasylyszyn23 | 2016 | DPCP + imiquimod vs DPCP | 3 | Case-control | 9 | 1 | 3 | 5 | - | Both-2/3 (66.7%) DPCP only-0/6 (0%) | Both-1/3 (33.3%) DPCP only-2/6 (33.3%) | Both-0/3 (0%) DPCP only-4/6 (66.7%) | NA | Scalp eczema, discomfort, LAD |

| Luk24 | 2012 | DPCP | 4 | Case series | 3 | - | 2 | 1 | - | - | - | 3 (100%) | NA | Itching, erythema, bulla, scaling, LAD, hyperpigmentation, urticarial reactions |

| Salsberg25 | 2012 | DPCP | 4 | Case series | 108 | 82 | - | - | 26 | 12 (11%) | 23 (21%) | 27 (25%) | NA | Edema, dermatitis, vesicles, desquamation, urticaria, erosions, LAD |

| Singh26 | 2007 | DPCP | 4 | Case series | 3 | - | - | - | 3 | 1 (33.3%) | 2 (66.7%) | - | NA | None |

| Sotiriadis27 | 2006 | DPCP | 4 | Case series | 14 | 7 | 3 | 4 | - | 2 (14.3%) | 8 (57.1%) | 4 (28.6%) | NA | Eczema, headache, itching, hyperpigmentation |

| Schuttelaar28 | 1996 | DPCP | 4 | Case series | 25 | 10 | 15 | - | - | 8 (32%) | 4 (16%) | 13 (52%) | 7 (58.3%) | Eczema, itching, vesicles, headache, LAD |

| Hull29 | 1991 | DPCP | 4 | Case series | 12 | 4 | 8 | - | - | 4 (33.3%) | 4 (33.3%) | 4 (33.3%) | 4 (50%) | Eczema with superimposed infection, blistering |

| Orecchia30 | 1985 | DPCP | 4 | Case series | 26 | 9 | 7 | 10 | - | 1 (3.8%) | 13 (50%) | 12 (46.1%) | 4 (28.6%) | LAD, itching, eczema |

| Chen31 | 2017 | SADBE | 5 | Case report | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | - | 1 (100%) | - | NA | Angioedema |

| Guerra32 | 2017 | SADBE | 5 | Case report | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | - | 1 (100%) | - | 1 (100%) | Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita |

| Tosti33 | 1996 | SADBE | 4 | Case series | 33 | - | 10 | 23 | - | 10 (30.3%) | 6 (18.2%) | 17 (51.5%) | 10 (62.5%) | Contact dermatitis, LAD |

| Orecchia34 | 1995 | SADBE | 4 | Case series | 28 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 9 (32.1%) | 6 (21.4%) | 13 (46.4%) | NA | None |

| Giannetti35 | 1983 | SADBE | 4 | Case series | 15 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 1 (6.6%) | 6 (40%) | 8 (53.3%) | NA | Eczema, LAD, itching |

| Cryotherapy | ||||||||||||||

| Jun36 | 2017 | Cryotherapy | 4 | Case series | 24 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 5 (20.8%) | 15 (62.5%) | 4 (16.7%) | NA | Pain, pruritus, inflammation, swelling |

| Minoxidil | ||||||||||||||

| Rai37 | 2017 | Minoxidil | 5 | Case report | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | 1 (100%)ǁ | NA | Hypertrichosis |

| Guerouaz38 | 2014 | Minoxidil | 5 | Case report | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | - | 1 (100%)ǁ | - | NA | Hypertrichosis |

| Herskovitz39 | 2013 | Minoxidil | 5 | Case report | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | - | 1 (100%)ǁ | - | NA | Hypertrichosis |

| Georgala40 | 2007 | Minoxidil | 4 | Case series | 3 | 2 | 1 | - | - | - | - | 3 (100%)ǁ | NA | Palpitations, dizziness, sinus tachycardia |

| Lenane41¶ | 2005 | Minoxidil | 4 | Case series | 1 | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | 1 (100%)ǁ | NA | None |

| Baral42# | 1989 | Minoxidil + TC + ILC | 5 | Case report | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | - | 1 (100%)ǁ | - | NA | Hypertrichosis |

| Weiss43 | 1981 | Minoxidil | 4 | Case series | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | - | 1 (100%) | - | NA | None |

| Topical Calcineurin Inhibitors | ||||||||||||||

| Jung44 | 2017 | Topical tacrolimus vs clobetasol, split-scalp | 2 | Prospective comparative cohort | 3 | 3 | - | - | - | TC-2/3 (66.7%) TT-0/3 (0%) | TC-1/3 (33.3%) TT-2/3 (66.7%) | TC-0/3 (0%) TT-1/3 (33.3%) | NA | None |

| Rigopoulos45 | 2007 | Topical pimecrolimus vs placebo, split-scalp | 2 | Prospective comparative cohort | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | 1 (100%) | NA | Burning |

| Price46 | 2005 | Topical tacrolimus | 4 | Case series | 2 | 2 | - | - | - | - | - | 2 (100%) | NA | None |

| Thiers47 | 2000 | Topical tacrolimus | 5 | Case report | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | 1 (100%) | NA | NA |

| Topical and Intralesional Corticosteroids | ||||||||||||||

| Sankararaman48 | 2017 | ILC | 5 | Case report | 1 | - | - | - | 1 | - | 1 (100%) | - | 1 (100%) | None |

| Jung44 | 2017 | Clobetasol vs topical tacrolimus, split-scalp | 2 | Prospective comparative cohort | 3 | 3 | - | - | - | TC-2/3 (66.7%) TT-0 (0%) | TC-1/3 (33.3%) TT-2/3 (66.7%) | TC-0/3 (0%) TT-1/3 (33.3%) | NA | None |

| Lalosevic49# | 2015 | Oral PDC + clobetasol | 4 | Case series | 65 | 35 | 15 | 15 | 26 (40%) | 17 (26.2%) | 22 (33.8%) | 11 (25.6%) | Headache (after oral PDC), skin atrophy | |

| Torchia22 | 2015 | Triamcinolone + clobetasol vs anthralin, split-scalp | 5 | Case report | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | TC side | - | Anthralin side | NA | None |

| Lenane50 | 2014 | Clobetasol vs hydrocortisone | 1 | Randomized controlled trial | 41 | 41 | - | - | - | >50% regrowth Clobetasol-17/20 (85%) Hydrocortisone-7/21 (33.3%) | <50% regrowth Clobetasol-3/20 Hydrocortisone-14/21 (66.7%) | NA | Skin atrophy | |

| Lenane41¶ | 2005 | TC | 4 | Case series | 4 | 2 | 2 | - | - | 2 (50%) | 1 (25%) | 1 (25%) | 1 (50%) | Skin atrophy |

| Baral42# | 1989 | Minoxidil + TC + ILC | 5 | Case report | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | 1 (100%)ǁ | NA | Hypertrichosis |

| Montes51 | 1977 | Halcinonide | 4 | Case series | 2 | 1 | 1 | - | - | 2 (100%) | - | - | NA | Folliculitis |

| Prostaglandins | ||||||||||||||

| Borchert52 | 2016 | Bimatoprost | 1/2 | Randomized controlled trial | 15 | NA | NA | NA | NA | - | Bimatoprost-5/9 (55.6%); Vehicle-1/6 (16.7%) | Bimatoprost-4/9 (44.4%); Vehicle-5/6 (83.3%) | NA | Conjunctival hyperemia, conjunctivitis, eczema, eyelid erythema |

| Li53 | 2016 | Bimatoprost (scalp) | 5 | Case report | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | 1 (100%) | - | - | NA | None |

| Zaheri54 | 2010 | Bimatoprost | 5 | Case report | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | 1 (100%) | - | - | NA | None |

| Yadav55 | 2009 | Latanoprost | 5 | Case report | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | 1 (100%) | - | - | NA | None |

| Mehta56 | 2003 | Latanoprost | 5 | Case report | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | - | 1 (100%) | - | NA | None |

AA, Alopecia areata; AO, alopecia ophiasis; AT, alopecia totalis; AU, alopecia universalis; CR, complete response; DPCP, diphenylcyclopropenone; ILC, intralesional corticosteroids; LAD, lymphadenopathy; LoE, level of evidence; N, number of pediatric patients; NA, not available; NR, no response; OC, oral corticosteroids; PDC, pulse dose corticosteroids; PR, partial response; PT, psychotherapy; RR, relapse rate; SADBE, squaric acid dibutylester; SE, side effects; TC, topical corticosteroids; TT, topical tacrolimus.

Complete response defined as $95% hair regrowth, (n %) = percent of total number of patients.

Partial response defined as\95% and[0% hair regrowth, (n %) = percent of total number of patients.

No response defined as 0% hair regrowth, (n %) = percent of total number of patients.

Relapse rate defined as number of patients who responded to treatment and experienced recurrence of hair loss, (n %) = percent of responsive patients.

Patient(s) discontinued study due to adverse events.

Study listed under both Minoxidil and TC sections as it provides data for both treatments in separate patients.

Study listed under multiple sections due to inclusion of multiple treatments.

Table III.

Included studies evaluating miscellaneous treatment of alopecia areata in pediatric patients

| First author | Year | Treatment | LoE | Study type | N | AA | AT | AU | AO | CR* | PR† | NR‡ | RR§ | SE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liu4 | 2017 | Apremilast | 4 | Case series | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | 1 (100%) | NA | Diarrhea, nausea, headaches, lethargy |

| Cho5 | 2010 | Botulinum Toxin A | 4 | Case series | 3 | - | 1 | 2 | - | - | - | 3 (100%) | NA | None |

| Sarifakioglu6 | 2006 | Topical sildenafil | 4 | Case series | 8 | - | - | - | - | - | 3 (37.5%) | 5 (62.5%) | NA | None |

| Fessatou7 | 2003 | Gluten-free diet | 4 | Case series | 2 | - | - | - | - | 1 (50%) | 1 (50%) | - | NA | None |

| Boonyaleepun8 | 1999 | IVIG | 5 | Case report | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | - | 1 (100%) | - | NA | None |

| Shibuya9 | 1990 | Bone marrow transplant|| | 5 | Case report | 1 | - | 1 | - | - | 1 (100%) | - | - | NA | Chronic GVHD skin eruption |

| Rozin10 | 2003 | Cotrimoxazole | 5 | Case report | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | 1 (100%) | - | - | 1 (100%) | None |

| Zawahry11 | 1973 | Aloe | 4 | Case series | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | - | 1 (100%) | - | NA | None |

| Skurkovich12 | 2005 | Anti-IFN gamma antibodies | 4 | Case series | 16 | 11 | 5 | - | - | 12 (75%) | 4 (25%) | 1 (8.3%) | None | |

| Willemsen13 | 2006 | Hypnosis¶ | 4 | Case series | 2 | - | - | 2 | - | 1 (50%) | - | 1 (50%) | 1 (100%) | None |

| Letada14 | 2007 | Topical imiquimod | 5 | Case report | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | - | 1 (100%) | - | 1 (100%) | None |

| Koblenzer15 | 1995 | Psychotherapy# | 5 | Case report | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | - | 1 (100%) | - | NA | None |

| Putt16 | 1994 | Massage, relaxation, and reward | 5 | Case report | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | - | 1 (100%) | - | NA | None |

| Teshima17 | 1991 | Psychotherapy (PT) + OC and CYA vs OC and CYA | 3 | Case-control | 5 | - | - | 5 | - | PT + OC and CYA - 2/2 (100%); OC and CYA −1/3 (33.3%) | PT + OC and CYA - 0/2 (0%); OC and CYA - 2/3 (66.7%) | NA | None | |

| Arrazola18 | 1985 | Topical nitrogen mustard | 4 | Case series | 4 | 2 | 2 | - | - | - | 4 (100%) | - | NA | Allergic contact dermatitis |

AA, Alopecia areata; AO, alopecia ophiasis; AT, alopecia totalis; AU, alopecia universalis; CR, complete response; CYA, cyclosporin; DPCP, diphenylcyclopropenone; GVHD, graft-versus-host disease; ILC, intralesional corticosteroids; IFN, interferon; IVIG, intravenous immunoglobulin; LoE, level of evidence; N, number of pediatric patients; NA, not available; NR, no response; OC, oral corticosteroids; PR, partial response; PT, psychotherapy; RR, relapse rate; SE, side effects.

Complete response defined as ≥95% hair regrowth, (n %) = percent of total number of patients.

Partial response defined as <95% and >0% hair regrowth, (n %) = percent of total number of patients.

No response defined as 0% hair regrowth, (n %) = percent of total number of patients.

Relapse rate defined as number of patients who responded to treatment and experienced recurrence of hair loss, (n %) = percent of responsive patients.

Postoperative cyclosporin and short-term methotrexate were also given for graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis.

Both patients were simultaneously treated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.

Psychotherapy was supplemented by minoxidil and anthralin.

Topical therapies

Anthralin.

Useof the irritant anthralin to treat AA in pediatric patients was demonstrated in 4 case series or reports, including 69 patients (strongest LoE 4; Table I).19–22 Complete response rates ranged between 32% and 33.3% with relapse rates of 9.5% to 64%. One case reported complete regrowth when combined with leflunomide.19 The mean time to maximal response was approximately 9 to 15 months.19–22 Anthralin caused staining of the skin and regional lymphadenopathy (LAD), which resolved after cessation of treatment. Other side effects were itching, burning, oozing, and bullous eruptions, but systemic side effects were rare.118

Contact immunotherapy.

Diphenylcyclo propenone.

Treatment of the affected areas with diphenylcyclopropenone (DPCP) includes sensitization prior to initial treatment and escalating dose concentrations. The essentially painless application method makes DPCP an ideal and frequently utilized treatment option for the pediatric population. Eight articles reported DPCP treatment in 200 children with AA (strongest LoE 3).23–30 Complete response rates ranged from 0% to 33.3%, similar to the results of a meta-analysis (30.7%).119 Relapses were common, with relapse rates ranging from 12.5% to 58.3%.28,29,30 One case-control study noted the potential of imiquimod to improve DPCP efficacy.23 Side effects included eczematous reactions of the scalp, pruritus, regional LAD, vesiculation, or, rarely, a secondary infection.29 No systemic side effects except headache were reported.

Squaric acid dibutyl ester.

The efficacy of squaric acid dibutyl ester (SADBE) was studied in 78 pediatric patients (strongest LoE 4). Complete response rates ranged from 0% to 33.3%.33–35 A meta-analysis including adult and pediatric patients demonstrated slightly better complete response rates with SADBE (38.4%) than with DPCP (30.7%).119 Relapse rates ranged between 62.5% and 100%. Side effects included irritation, itching, LAD, and contact dermatitis.31 There was 1 case of epidermolysis bullosa aquisita that arose during treatment of AA with SADBE and regressed upon discontinuation.32 There was no evidence of systemic absorption through topical application.120

Cryotherapy.

One case series documented the use of cryotherapy in 24 patients <10 years of age and 40 patients between the ages of 10 and 20 (strongest LoE 4). Complete response was seen in 20.8% of patients <10 years of age. Side effects were localized, but included pain, pruritus, inflammation, and swelling.36,121

Minoxidil.

Minoxidil’s efficacy is equivocal for adult AA122 and only case reports exist evaluating its use in 9 children (strongest LoE 4). Minoxidil is mostly used as an adjunctive therapy.41,83 Side effects of minoxidil included extensive hypertrichosis.37–40,42 Although excessive topical administration may lead to systemic absorption (manifesting as palpitations, hypotension, etc.), the typical twice daily dose is generally safe.123

Topical calcineurin inhibitors.

The consensus of 4 studies that included 7 pediatric AA patients is that topical calcineurin inhibitors, tacrolimus and pimecrolimus, are not effective for the treatment of AA (strongest LoE 2). Approximately 29% showed only a minimal response,44 while the remaining 71% showed no response and often experienced disease progression.45–47,124

Topical and intralesional corticosteroids.

The use of topical corticosteroids, particularly high-potency topical corticosteroids, is supported by the literature (strongest LoE 1) and is considered a safe and effective first-line treatment option in children with patchy AA. High-potency topical corticosteroids showed a higher efficacy than low-potency topical corticosteroids in a RCT that included 41 pediatric patients.50 They were also superior to topical tacrolimus44 and anthralin22 and were often used as adjunctive therapies.49,51,63,83 High-potency topical corticosteroids were generally well tolerated in children. Side effects included skin atrophy, telangiectasias, and folliculitis. Although intralesional corticosteroid (triamcinolone) therapy is effective, these studies are rare in children due to the pain associated with the injections.48 Based on data on adult patients, the most common side effects are pain, skin atrophy, and dyspigmentation. Other adverse effects are rare, although anaphylaxis and cataracts and increased intraocular pressure, if used close to the eyes, have been reported.125

Prostaglandins.

Topical prostaglandins, including bimatoprost and latanoprost, may improve the regrowth of scalp and eyelash hair (strongest LoE 1–2) in AA,52–56 although statistically significant differences between bimatoprost and vehicle were not found in a RCT examining eyelash hair growth in pediatric AA patients.52 While prostaglandins, specifically latanoprost, can cause irreversible iris and eyelid hyperpigmentation, uveitis, eyelash curling, and conjunctival hyperemia, these side effects were not reported in patients with AA.52–56,126

Systemic therapies

Corticosteroids.

Systemic corticosteroid therapy was the most studied treatment modality for AA in both children and adults, comprising 27 studies, mostly case series, that included 272 pediatric patients (strongest LoE 2; Table II). The studies included combination therapy with an adjunctive systemic drug including methotrexate or cyclosporine,60–62,68,72 intravenous pulse-dosed corticosteroids,68,70–74,77,79,81,82 oral pulse-dosed corticosteroids,49,60,69,71,75,76,78,80 oral corticosteroid maintenance or tapered therapy,61,62,64–67 and intramuscular corticosteroids.57–59

Table II.

Included studies evaluating systemic treatment of alopecia areata in pediatric patients

| First author | Year | Treatment | LoE | Study type | N | AA | AT | AU | AO | CR* | PR† | NR‡ | RR§ | SE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intramuscular Corticosteroids | ||||||||||||||

| Seo57 | 2017 | IMC | 4 | Case series | 2 | - | 2 | - | - | 1 (50%) | 1 (50%) | - | NA | None |

| Sato-Kawamura58 | 2002 | IMC | 4 | Case series | 1 | - | 1 | - | - | 1 (100%) | - | - | NA | None |

| Michalowski59 | 1978 | IMC | 4 | Case series | 6 | - | 5 | 1 | - | 2 (33.3%) | 2 (33.3%) | 2 (33.3%) | 4 (100%) | Hypertrichosis, diabetes, moon facies, striae, dysmenorrhea, pseudoacanthosis nigricansǁ |

| Oral Corticosteroids | ||||||||||||||

| Anuset60# | 2016 | OC + MTX | 4 | Case series | 4 | 1 | 1 | 2 | - | 2 (50%) | - | 2 (50%) (1 on MTX only) | 2 (100%) | Transient elevation of transaminases, weight gain, cataracts, pneumocystis pneumoniaǁ |

| Gensure61 | 2013 | OC + cyclosporine | 5 | Case report | 1 | - | 1 | - | - | 1 (100%) | - | - | NA | Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis |

| Kim62 | 2008 | OC + cyclosporine | 4 | Case series | 9 | 5 | 4 | - | - | 5 (55.5%) | 3 (33.3%) | 1 (11.1%) | NA | Edema, acne, weight gain, hypertrichosis, GI disturbance, menstrual abnormality |

| Camacho63 | 1999 | OC vs ZBC | 2 | Prospective comparative cohort | 18 | 6 | 12 | 3 | - | OC-0/9 (0%) ZBC-3/9 (33.3%) | OC-4/9 (44.4%) ZBC-5/9 (55.5%) | OC-5/9 (55.5%) ZBC-1/9 (11.1%) | NA | Cushingoid features, delayed physical development |

| Alabdulkareem64 | 1998 | OC | 4 | Case series | 11 | - | 8 | 1 | - | 1 (9%) | 5 (45.4%) | 5 (45.4%) | 5 (83.3%) | Acne, striae, moon facies |

| Schindler65 | 1987 | OC | 5 | Case report | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | 1 (100%) | - | - | 0 (0%) | Weight gain, Cushingoid features |

| Unger66 | 1978 | OC | 4 | Case series | 6 | 1 | 4 | 1 | - | 3 (50%) | 3 (50%) | - | 3 (50%) | Weight gain |

| Winter67 | 1976 | OC | 4 | Case series | 12 | 3 | 4 | 5 | - | 5 (41.7%) | - | 7 (58.3%) | NA | Weight gain, abdominal pain, cataracts, acne, hypertension, seizure, psychological problems, obesity |

| Pulse Dose Corticosteroids | ||||||||||||||

| Chong68# | 2017 | IV PDC + MTX | 4 | Case series | 14 | - | 14 | - | 1 (7.1%) | 5 (35.7%) | 8 (57.1%) | NA | Abdominal discomfort | |

| John-Bassler69 | 2017 | IV PDC | 4 | Case series | 13 | 6 | 5 | 2 | - | 8 (61.5%) | - | 5 (38.5%) | 3 (37.5%) | Weight gain, acne |

| Lalosevic49# | 2015 | Oral PDC + TC | 4 | Case series | 65 | 35 | 15 | 15 | 26 (40%) | 17 (26.2%) | 22 (33.8%) | 11 (25%) | Headache, skin atrophy | |

| Smith70 | 2015 | IV PDC | 4 | Case series | 18 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 11 | 2 (11.1%) | 9 (50%) | 7 (38.9%) | 7 (63.6%) | Mood changes, metallic taste, acne, allergic reaction |

| Friedland71 | 2013 | IV PDC | 4 | Case series | 24 | 8 | 4 | 1 | 10 | 9 (37.5%); 5/8 AA, 1/4 AT, 0/2, AU, 3/10 AO | 7 (29.2%); 1/8 AA, 1/4 AT, 1/2, AU, 4/10 AO | 8 (33.3%); 2/8 AA, 2/4 AT, 1/2, AU, 3/10 AO | 13 (81.2%); 5/6 AA, 1/2 AT, 1/1, AU, 6/7 AO | Verrucae, gastritis, abdominal pain |

| Droitcourt72# | 2012 | IV PDC + MTX | 4 | Case series | 2 | 2 | - | - | - | 1 (50%) | 1 (50%) | - | 2 (100%) | Nausea, neutropenia |

| Sauerbrey73 | 2011 | IV PDC + TT | 4 | Case series | 2 | - | 1 | - | - | 2 (100%) | - | - | 1 (50%) | None |

| Hubiche74 | 2008 | IV PDC | 4 | Case series | 12 | - | 4 | 1 | 7 | - | 10 (83.3%) | 2 (16.7%) | 6 (60%) | None |

| Sethuraman75 | 2006 | Oral PDC + minoxidil | 5 | Case report | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | 1 (100%) | - | NA | None | |

| Bin Saif76 | 2006 | Oral PDC | 5 | Case report | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | 1 (100%) | - | - | 1 (100%) | Nocturnal enuresis |

| Seiter77 | 2001 | IV PDC | 4 | Case series | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 | - | 2 (50%); 2/2 AA, 0/1 AT, 0/1 AU | - | 2 (50%) | NA | Headache, fatigue, nausea, palpitations |

| Sharma78 | 1999 | Oral PDC | 4 | Case series | 4 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 4 (100%) | - | - | NA | NA |

| Friedli79 | 1998 | IV PDC | 4 | Case series | 7 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 (14.3%); 1/1 AA, 0/4 AT, 0/1 AU, 0/1 AO | 2 (28.6%); AA 0/1, AT 1/4, AU 0/1, AO 1/1 | 4 (57.1%); AA 1/1, 3/4 AT, AU 1/1, AO 0/1 | 2 (66.7%); AA 0/1, AT 1/1, 1/1 AO | Fatigue, headache, palpitations, dyspnea, nausea |

| Sharma80 | 1998 | Oral PDC | 4 | Case series | 16 | 13 | 3 | - | 1 | 6 (37.5%) | 6 (37.5%) | 3 (18.7%) | 4 (33.3%) | Epigastric burning, headache |

| Kiesch81 | 1997 | IV PDC | 4 | Case series | 7 | 3 | 1 | - | 3 | 5 (71.4%); AA 3/3, AO 2/3 | - | 2 (28.6%); AT 1/1, AO 1/3 | 1 (20%) | Abdominal pain |

| Perriard-Wolfensberger82 | 1993 | IV PDC | 4 | Case series | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | - | 1 (100%) | - | NA | Flushing |

| Hydroxychloroquine | ||||||||||||||

| Yun83 | 2018 | HCQ +/− TC and/or minoxidil | 4 | Case series | 9 | 6 | 1 | 2 | - | 1 (11.1%) | 5 (55.5%) | 3 (33.3%) | NA | Headache, abdominal pain, viral gastroenteritis |

| Methotrexate | ||||||||||||||

| Mascia84 | 2019 | MTX + azathioprine | 4 | Case series | 3 | 2 | 1 | - | - | - | 3 (100%) | - | NA | GI distress, lymphopeniaǁ |

| Chong68# | 2017 | MTX + IV PDC | 4 | Case series | 14 | - | 14 | - | 1 (7.1%) | 5 (35.7%) | 8 (57.1%) | NA | Abdominal discomfort | |

| Landis85 | 2018 | MTX | 4 | Case series | 11 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 4 (36.4%) | 7 (63.6%) | - | 2 (18.1%) | Leg weakness, tooth sensitivity |

| Anuset68¶ | 2016 | MTX + OC | 4 | Case series | 4 | 1 | 1 | 2 | - | 2 (50%) | - | 2 (50%) (1 on MTX only) | 2 (100%) | Transient elevation of transaminases, weight gain, cataracts, pneumocystis pneumoniaǁ |

| Batalla86 | 2016 | MTX | 4 | Case series | 3 | 1 | 1 | - | 1 | 2 (66.7%) | 1 (33.3%) | 1 (50%) | Elevated hepatic transaminases | |

| Lucas87 | 2016 | MTX | 4 | Case series | 13 | NA | NA | NA | NA | - | 5 (38.5%) | 8 (61.5%) | 2 (40%) | Recurrent nausea |

| Droitcourt72# | 2012 | MTX + IV PDC | 4 | Case series | 2 | 2 | - | - | - | 1 (50%) | - | - | 2 (100%) | Nausea, neutropenia |

| Royer88 | 2011 | MTX +/− OC | 4 | Case series | 14 | 7 | 7 | - | - | 11 (78.6%) | 3 (21.4%) | 3 (27.3%) | Nausea, herpes zoster | |

| Sulfasalazine and Mesalazine | ||||||||||||||

| Kiszewski89 | 2018 | Mesalazine +/− TC, OC, minoxidil | 4 | Case series | 5 | 3 | - | 1 | 1 | 5 (100%) | - | - | NA | None |

| Rashidi | 2008 | Sulfasalazine | 4 | Case series | 7 | 4 | 3 | - | - | - | 7 (100%) | - | NA | Dizziness, headache, dyspepsia |

| Bakar91 | 2007 | Sulfasalazine+ OC | 4 | Case series | 3 | 3 | - | - | - | - | 3 (100%) | - | NA | None |

| Ustekinumab | ||||||||||||||

| Aleisa92 | 2019 | Ustekinumab | 4 | Case series | 3 | 2 | 1 | - | - | 1 (33.3%) | 2 (66.7%) | - | NA | NA |

| Ortolan93 | 2019 | Ustekinumab | 4 | Case series | 3 | - | 3 | - | - | - | - | 3 (100%) | NA | NA |

| JAK Inhibitors | ||||||||||||||

| Jabbari94 | 2015 | Baricitinib | 5 | Case report | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | 1 (100%) | - | - | NA | None |

| Craiglow95 | 2019 | Tofacitinib | 4 | Case series | 4 | - | 1 | 3 | - | 2 (50%) | 1 (25%) | 1 (25%) | NA | None |

| Dai96 | 2019 | Tofacitinib | 4 | Case series | 3 | - | 2 | 1 | - | 1 (33.3%) | 2 (66.7%) | - | NA | Diarrhea, URI |

| Brown97 | 2018 | Tofacitinib | 5 | Case report | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | 1 (100%) | - | - | NA | Headache |

| Patel98 | 2018 | Tofacitinib | 4 | Case series | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | - | 1 (100%) | - | NA | Increased appetite, weight gain |

| Castelo-Soccio99 | 2017 | Tofacitinib | 4 | Case series | 6 | - | - | 6 | - | - | 6 (100%) | - | NA | None |

| Craiglow100 | 2017 | Tofacitinib | 4 | Case series | 13 | 6 | 1 | 6 | - | 1 (7.7%) | 8 (69.2%) | 4 (30.8%) | NA | Headache, URI, transient elevation in hepatic transaminases |

| Liu101 | 2019 | Ruxolitinib | 4 | Case series | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | 1 (100%) | - | - | NA | URI, weight gain, acne, easy bruising, fatigueǁ |

| Putterman102 | 2018 | Topical tofacitinib | 4 | Case series | 11 | 1 | 4 | 6 | - | 3 (27.3%) | 5 (45.4%) | 1 (9%) | NA | Irritation |

| Bayart103 | 2017 | Topical tofacitinib or topical ruxolitinib | 4 | Case series | 6 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 (16.7%) | 3 (50%) | 2 (66.7%) | NA | None | |

| Craiglow104 | 2016 | Topical ruxolitinib | 5 | Case report | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | - | 1 (100%) | - | NA | Minor decrease in WBC |

| Laser and Light Therapy | ||||||||||||||

| Fenniche105 | 2018 | 308 nm excimer lamp + topical khellin | 5 | Case report | 1 | - | - | - | 1 | 1 (100%) | - | - | None | Mild transient erythema |

| Al-Mutairi106 | 2009 | 308 nm excimer laser | 4 | Case series | 11 | 9 | 2 | - | - | 5 (45.4%) | 3 (27.3%) | 3 (27.3%) | 4 (50%) | Mild erythema, peeling |

| Al-Mutairi107 | 2007 | 308 nm excimer laser | 4 | Case series | 4 | 4 | - | - | - | - | 1 (25%) | 3 (75%) | NA | Mild erythema, peeling |

| Zakaria108 | 2004 | 308 nm excimer laser | 4 | Case series | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | - | 1 (100%) | - | NA | Mild erythema, hyperpigmentation |

| Phototherapy | ||||||||||||||

| Jury109 | 2006 | NBUVB | 4 | Case series | 6 | NA | NA | NA | NA | - | 1 (16.7%) | 5 (83.3%) | NA | Erythema, blistering, anxiety |

| Ersoy-Evans110 | 2008 | PUVA | 4 | Case series | 10 | 3 | 4 | 3 | - | 2 (20%) | NA | Erythema, pruritus, burning | ||

| Yoon111 | 2005 | PUVA + TT | 5 | Case report | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | 1 (100%) | - | - | NA | None |

| Mitchell112 | 1985 | PUVA | 4 | Case series | 5 | 3 | 2 | - | - | - | 5 (100%) | - | 3 (75%) | None |

| Claudy113 | 1983 | PUVA | 4 | Case series | 7 | 2 | 2 | 3 | - | 3 (42.8%) | - | 4 (57.1%) | NA | Pruritus |

| Amer114 | 1983 | PUVA | 4 | Case series | 2 | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | - | 2 (100%) | NA | None |

| Lux-Battistelli115 | 2015 | PUVA + zinc | 4 | Case series | 1 | - | 1 | - | - | - | 1 (100%) | - | 1 (100%) | Seborrheic dermatitis, acne |

| Majumdar116 | 2018 | Topical psoralen + natural sunlight | 4 | Case series | 5 | 4 | - | 1 | - | - | 5 (100%) | - | NA | Erythema, irritation, hyperpigmentation, scaling |

| Belezos117 | 1965 | UV irradiation + topical estrogen | 4 | Case series | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | 1 (100%) | - | - | NA | None |

AA, Alopecia areata; AO, alopecia ophiasis; AT, alopecia totalis; AU, alopecia universalis; CR, complete response; GI, gastrointestinal; IMC, intramuscular corticosteroids; IV, intravenous; LoE, level of evidence; MTX, methotrexate; N, number of patients; NA, not available; NBUVB, narrow-band ultraviolet B; NR, no response; OC, oral corticosteroids; PDC, pulse dose corticosteroids; PR, partial response; PUVA, psoralen ultraviolet A; RR, relapse rate; SE, side effects; TC, topical corticosteroids; TT, topical tacrolimus; URI, upper respiratory infection; UV, ultraviolet; WBC; white blood cells; ZBC, zinc biotin, and clobetasol.

Complete response defined as ≥95% hair regrowth, (n %) = percent of total number of patients.

Partial response defined as <95% and >0% hair regrowth, (n %) = percent of total number of patients.

No response defined as 0% hair regrowth, (n %) = percent of total number of patients.

Relapse rate defined as number of patients who responded to treatment and experienced recurrence of hair loss, (n %) = percent of responsive patients.

Adverse events reported in both adult and pediatric patients.

Patient(s) discontinued study due to adverse events.

Study listed under multiple sections due to inclusion of multiple treatments.

Although doses and frequencies varied among each route of administration, approximately 45% (range 0% to 100%) of patients receiving intravenous or oral pulse-dosed corticosteroids demonstrated a complete response and 34% (range 0% to 55.5%) of patients receiving traditional oral corticosteroid regimens demonstrated a complete response. For pulse-dosed therapy, shorter disease duration, younger age at disease onset, and multifocal disease (as opposed to AT and AU) were found to be associated with a better response.71 Relapse rates ranged between 16.7 and100% for pulse-dosed and 50% and 100% for non-pulse-dosed corticosteroids.59,64 Significant side effects were reported, including weight gain, cataracts, infections, hypertension, Cushingoid features, psychiatric disturbances, striae, and acne. Side effects were greater and more frequent for non-pulse-dosed regimens (Table II).127,128

Hydroxychloroquine.

A single case series of 9 pediatric patients examined the use of hydroxychloroquine (strongest LoE 4). When used in conjunction with topical corticosteroids and/or minoxidil, complete response was seen in 11% and partial response in 55% of patients.83 Reported side effects included abdominal pain and headache.83

Methotrexate.

Eight articles reported studies of methotrexate, either as a solitary agent or in conjunction with oral or intravenous corticosteroids or azathioprine, for the treatment of AA in 42 pediatric patients (strongest LoE 4).60,68,72,84–88 Complete response was seen on average in 17.9% (range 0% to 50%; Table II) and partial response in 47.9% (range 0% to 100%) with doses ranging from 2.5 mg to 25 mg per week.60,72,85–88 A meta-analysis revealed a higher complete response in adult versus pediatric AA patients (44.7% vs 11.6%), although the relapse rate in children was significantly lower than that in adults (31.7% vs 52%).129 Reported side effects included nausea, elevations in hepatic transaminases, and hematologic changes (Table II).

Sulfasalazine and mesalazine.

Limited data exist for the use of sulfasalazine and mesalazine for pediatric AA (strongest LoE 4). Complete response to mesalazine, with or without concurrent oral or topical corticosteroids and minoxidil, was reported in 1 case series of 5 pediatric patients.89 Ten adolescent AA patients treated with oral sulfasalazine in 2 studies all demonstrated partial response with a starting dose of 1 g/week, which was escalated to a final dose of 3 g/week.90,91 Side effects for sulfasalazine included dizziness, headache, and dyspepsia (Table II). This was similar to the side-effect profile in adults, which included gastrointestinal distress, rash, headache, and lab abnormalities.130

Ustekinumab.

A report of 3 adults whose AA responded to ustekinumab, a monoclonal antibody used for psoriasis that blocks interleukins 12 and 23,131 prompted the treatment in pediatric AA and AT patients with variable results (strongest LoE was 4). One case series showed a complete or partial response in all 3 patients, while the other study reported no response.92,93 Although injection-site reactions, infections, nausea, and vomiting are known side effects of ustekinumab, none were reported in these 2 studies.

Janus kinase inhibitors.

Increasing evidence suggests that JAK inhibitors may be effective in the treatment of AA, but data in children are limited (strongest LoE 4). Side effects included infections, diarrhea, hypertension, thrombosis, gastrointestinal perforation, laboratory abnormalities, and hematologic malignancies.132

Baricitinib.

Clinical trials have been initiated to evaluate the safety and efficacy of baricitinib for the treatment of AA in adults but not yet in children.133,134 Only 1 pediatric case has been reported (strongest LoE 5). A 17-year-old male with a longstanding history of recalcitrant AA initially showed a partial response with baricitinib 7 mg once daily, followed by a complete response when the dose was increased to 11 mg once daily.94 No relapse was reported.

Ruxolitinib.

A case series of 8 AA patients treated with ruxolitinib included only 1 pediatric patient, who was treated with ruxolitinib 10 mg twice daily for 10 months and experienced a 91% improvement in the Severity of Alopecia Tool score with no adverse events.101

Tofacitinib.

Clinical trials are currently evaluating the efficacy of tofacitinib to treat AA in adults.99 Six case series and reports evaluated systemic tofacitinib for the treatment of AA in 28 pediatric patients.95–100 Of these patients, 82% showed complete or partial response and all nonresponders were patients with AU. Similarly, adults with severe AT or AU present for >10 years were less likely to respond to tofacitinib.100 Side effects included diarrhea, headaches, upper respiratory infection, increased appetite, weight gain, fatigue, and transient elevation in transaminases.

Topical tofacitinib and ruxolitinib.

In 3 reports documenting a total of 18 pediatric patients, 13 responded to topical therapy.102–104 Side effects included application site irritation102 and 1 case of borderline leukopenia in a patient with baseline low white blood cell count.104

Laser and phototherapy

Laser therapy.

Seventeen patients received treatment with a 308 nm excimer laser twice weekly with 58.8% response rate (strongest LoE 4).105–108 Side effects included mild scalp erythema and desquamation.

Phototherapy.

There were 6 reports involving 26 pediatric AA patients treated with psoralen and ultraviolet A therapy (strongest LoE 4).110–115,117 All 5 adolescents treated with a psoralen-soaked towel followed by sun exposure demonstrated partial response.116 Narrow-band ultraviolet B therapy was largely ineffective in pediatric patients,109 similar to the results in adults.135 Mild irritation, erythema, pruritus, and scaling were noted as side effects of phototherapy, similar to adult patients with AA.116

DISCUSSION

AA is an immune-mediated disease causing non-scarring hair loss with significant psychosocial impact.1 While a majority of children with limited AA spontaneously recover, the variability of the disease course and unpredictable response to therapy make AA challenging to treat. Although numerous therapies have been reported, the evidence is mostly weak. As a general guideline, low-risk topical therapies are a reasonable option for limited AA, while higher-risk systemic therapies may be warranted for patients who have extensive AA refractory to other therapies and who experience a significant psychosocial impact.

A limited number of trials have been conducted in pediatric AA patients, mostly involving topical corticosteroids.44,50 These studies provide the highest LoE for treatment with high-potency topical corticosteroids and have led to their preference as first-line therapy for pediatric AA. While intralesional corticosteroids are recommended as first-line treatment for patchy AA in adults,136 their use in children is limited by pain.137 Systemic steroids also can be efficacious, particularly in patients with a shorter disease duration, those who are at a younger age at disease onset, and those with multifocal disease71; however, their use is limited by significant side effects.127,128

Other treatment options include contact immunotherapy with DPCP or SADBE, although evidence in children is limited to case series24–30,33–35 (Table I). Protocols for the application of SADBE at home have been utilized more recently, increasing its convenience but increasing out-of-pocket cost when purchasing SADBE from compounding pharmacies. With respect to topical adjuvant therapy, minoxidil is commonly used as the ‘‘go-to’’ secondary agent in clinical practice, but our evidence does not support its use as a first-line agent122 (Table I). Topical calcineurin inhibitors are ineffective.45–47,124

A better understanding of the molecular pathogenesis of AA has resulted in the development of targeted therapies, including JAK inhibitors. Current clinical trials for adults with AA include treatment with tofacitinib, ruxolitinib, and baricitinib.133 Furthermore, clinical trials have been initiated recently to evaluate a JAK inhibitor, PF-06651600, for AA treatment in adults and adolescents older than 12 years of age.133 If pediatric data are able to reflect preliminary adult responses to systemic JAK inhibitors, these currently show promise as potential future therapies, but more trials, including trials with pediatric patients, are needed. While systemic JAK inhibitors may be an effective new therapy, their safety profile as well as cost may significantly limit their use to severe, treatment-refractory cases.99,132

It is also important to counsel patients and families regarding the chronicity of AA and the relapsing and remitting nature of the disease. Because of the lack of an evidence-based treatment algorithm, we recommend counseling patients and their families on the wide range of severity and varied responses to treatment among the different AA subtypes. Specifically, most data on AA are generalized from heterogenous groups of individuals, including patients with AT and AU. Subtype-specific response to treatment is not well-documented; however, it is known that the AT and AU subtypes generally bode more recalcitrant disease and worse outcomes. Clinicians should also highlight the existence and impact of AA comorbidities, particularly co-occurring autoimmune conditions, such as vitiligo, which add to the psychosocial impact of an AA diagnosis and can have long-lasting effects on self-esteem during childhood.138

CONCLUSIONS

Pediatric AA has a variable disease course with significant psychosocial impact. Although topical corticosteroids remain the preferred first-line treatment for pediatric AA, RCTs, and prospective comparative studies are needed to help define treatment guidelines. Additionally, a better understanding of prognostic markers in AA would be valuable.

Supplementary Material

CAPSULE SUMMARY.

Numerous therapies have been used to treat children and adolescents with alopecia areata (AA) with variable efficacy.

Topical corticosteroids have the highest level of evidence for the treatment of pediatric AA, followed by contact immunotherapy. More clinical trials and comparative studies are needed to further guide management of pediatric AA.

Acknowledgments

Funding sources: Dr Kiuru’s involvement in this article is in part supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculo-skeletal and Skin Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under award number K23AR074530.

Abbreviations used:

- AA

alopecia areata

- AO

alopecia ophiasis

- AT

alopecia totalis

- AU

alopecia universalis

- DPCP

diphenylcyclopropenone

- LAD

lymphadenopathy

- LoE

Levels of Evidence

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses

- RCT

randomized controlled trial

- SADBE

squaric acid dibutyl ester

Footnotes

IRB approval status: Not applicable.

Conflicts of interest

None disclosed.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lee HH, Gwillim E, Patel KR, et al. Epidemiology of alopecia areata, ophiasis, totalis, and universalis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2020;82(3):675–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ito T Advances in the management of alopecia areata. J Dermatol 2012;39(1):11–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Christensen T, Yang JS, Castelo-Soccio L. Bullying and quality of life in pediatric alopecia areata. Skin Appendage Disord 2017;3(3):115–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu LY, King BA. Lack of efficacy of apremilast in 9 patients with severe alopecia areata. J Am Acad Dermatol 2017;77(4): 773–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cho HR, Lew BL, Lew H, Sim WY. Treatment effects of intradermal botulinum toxin type A injection on alopecia areata. Dermatol Surg 2010;36(Suppl 4):2175–2181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sarifakioglu E, Degim IT, Gorpelioglu C. Determination of the sildenafil effect on alopecia areata in childhood: an open-pilot comparison study. J Dermatolog Treat 2006;17(4):235–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fessatou S, Kostaki M, Karpathios T. Coeliac disease and alopecia areata in childhood. J Paediatr Child Health 2003; 39(2):152–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boonyaleepun S, Boonyaleepun C, Schlactus JL. Effect of IVIG on the hair regrowth in a common variable immune deficiency patient with alopecia universalis. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol 1999;17(1):59–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shibuya A, Shinozawa T, Danya N, Maeda K. Successful bone marrow transplant and re-growth of hair in a patient with posthepatic aplastic anemia complicated by alopecia totalis. Acta Paediatr Jpn 1990;32(5):552–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rozin AP, Schapira D, Bergman R. Alopecia areata and relapsing polychondritis or mosaic autoimmunity? The first experience of co-trimoxazole treatment. Ann Rheum Dis 2003;62(8):778–780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zawahry ME, Hegazy MR, Helal M. Use of aloe in treating leg ulcers and dermatoses. Int J Dermatol 1973;12(1):68–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Skurkovich S, Korotky NG, Sharova NM, Skurkovich B. Treatment of alopecia areata with anti-interferon-gamma antibodies. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc 2005;10(3):283–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Willemsen R, Vanderlinden J, Deconinck A, Roseeuw D. Hypnotherapeutic management of alopecia areata. J Am Acad Dermatol 2006;55(2):233–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Letada PR, Sparling JD, Norwood C. Imiquimod in the treatment of alopecia universalis. Cutis 2007;79(2):138–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koblenzer CS. Psychotherapy for intractable inflammatory dermatoses. J Am Acad Dermatol 1995;32(4):609–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Putt SC, Weinstein L, Dzindolet MT. A case study: massage, relaxation, and reward for treatment of alopecia areata. Psychol Rep 1994;74(3 Pt 2):1315–1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Teshima H, Sogawa H, Mizobe K, Kuroki N, Nakagawa T. Application of psychoimmunotherapy in patients with alopecia universalis. Psychother Psychosom 1991;56(4): 235–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arrazola JM, Sendagorta E, Harto A, Ledo A. Treatment of alopecia areata with topical nitrogen mustard. Int J Dermatol 1985;24(9):608–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sardana K, Gupta A, Gautam RK. Recalcitrant alopecia areata responsive to leflunomide and anthralin-potentially undiscovered JAK/STAT inhibitors? Pediatr Dermatol 2018;35(6): 856–858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu SZ, Wang S, Ratnaparkhi R, Bergfeld WF. Treatment of pediatric alopecia areata with anthralin: a retrospective study of 37 patients. Pediatr Dermatol 2018;35(6):817–820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Özdemir M, Balevi A. Bilateral half-head comparison of 1% anthralin ointment in children with alopecia areata. Pediatr Dermatol 2017;34(2):128–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Torchia D, Schachner LA. Bilateral treatment for alopecia areata. Pediatr Dermatol 2010;27(4):415–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wasylyszyn T, Borowska K. Possible advantage of imiquimod and diphenylcyclopropenone combined treatment versus diphenylcyclopropenone alone: an observational study of nonresponder patients with alopecia areata. Australas J Dermatol 2017;58(3):219–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luk NM, Chiu LS, Lee KC, et al. Efficacy and safety of diphenylcyclopropenone among Chinese patients with steroid resistant and extensive alopecia areata. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2013;27(3):e400–e405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Salsberg JM, Donovan J. The safety and efficacy of diphencyprone for the treatment of alopecia areata in children. Arch Dermatol 2012;148(9):1084–1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Singh G, Okade R, Naik C, Dayanand CD. Diphenylcyclopropenone immunotherapy in ophiasis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2007;73(6):432–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sotiriadis D, Patsatsi A, Lazaridou E, Kastanis A, Vakirlis E, Chrysomallis F. Topical immunotherapy with diphenylcyclopropenone in the treatment of chronic extensive alopecia areata. Clin Exp Dermatol 2007;32(1):48–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schuttelaar ML, Hamstra JJ, Plinck EP, et al. Alopecia areata in children: treatment with diphencyprone. Br J Dermatol 1996; 135(4):581–585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hull SM, Pepall L, Cunliffe WJ. Alopecia areata in children: response to treatment with diphencyprone. Br J Dermatol 1991;125(2):164–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Orecchia G, Rabbiosi G. Treatment of alopecia areata with diphencyprone. Dermatologica 1985;171(3):193–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen CA, Carlberg V, Kroshinsky D. Angioedema after squaric acid treatment in a 6-year-old girl. Pediatr Dermatol 2017; 34(1):e44–e46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guerra L, Pacifico V, Calabresi V, et al. Childhood epidermolysis bullosa acquisita during squaric acid dibutyl ester immunotherapy for alopecia areata. Br J Dermatol 2017; 176(2):491–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tosti A, Guidetti MS, Bardazzi F, Misciali C. Long-term results of topical immunotherapy in children with alopecia totalis or alopecia universalis. J Am Acad Dermatol 1996;35(2 Pt 1):199–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Orecchia G, Malagoli P. Topical immunotherapy in children with alopecia areata. J Invest Dermatol 1995;104(5 suppl):35S–36S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Giannetti A, Orecchia G. Clinical experience on the treatment of alopecia areata with squaric acid dibutyl ester. Dermatologica 1983;167(5):280–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jun M, Lee NR, Lee WS. Efficacy and safety of superficial cryotherapy for alopecia areata: a retrospective, comprehensive review of 353 cases over 22 years. J Dermatol 2017;44(4): 386–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rai AK. Minoxidil-induced hypertrichosis in a child with alopecia areata. Indian Dermatol Online J 2017;8(2):147–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guerouaz N, Mohamed AO. Minoxidil induced hypertrichosis in children. Pan Afr Med J 2014;18:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Herskovitz I, Freedman J, Tosti A. Minoxidil induced hypertrichosis in a 2 year-old child. F1000Res 2013;2:226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Georgala S, Befon A, Maniatopoulou E, Georgala C. Topical use of minoxidil in children and systemic side effects. Dermatology 2007;214(1):101–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lenane P, Pope E, Krafchik B. Congenital alopecia areata. J Am Acad Dermatol 2005;52(2 suppl 1):8–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Baral J. Minoxidil and tail-like effect. Int J Dermatol 1989; 28(2):140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Weiss VC, West DP, Mueller CE. Topical minoxidil in alopecia areata. JAAD 1981. 10.1016/s0190-9622(81)80077-1 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Jung KE, Gye JW, Park MK, Park BC. Comparison of the topical FK506 and clobetasol propionate as first-line therapy in the treatment of early alopecia areata. Int J Dermatol 2017; 56(12):1487–1488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rigopoulos D, Gregoriou S, Korfitis C, et al. Lack of response of alopecia areata to pimecrolimus cream. Clin Exp Dermatol 2007;32(4):456–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Price VH, Willey A, Chen BK. Topical tacrolimus in alopecia areata. J Am Acad Dermatol 2005;52(1):138–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thiers BH. Topical tacrolimus: treatment failure in a patient with alopecia areata. Arch Dermatol 2000;136(1):124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sankararaman S, Bobonich M, Aktay AN. Alopecia areata in an adolescent with inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Pediatr 2017;56(14):1350–1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lalosevic J, Gajic-Veljic M, Bonaci-Nikolic B, Nikolic M. Combined oral pulse and topical corticosteroid therapy for severe alopecia areata in children: a long-term follow-up study. Dermatol Ther 2015;28(5):309–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lenane P, Macarthur C, Parkin PC, et al. Clobetasol propionate, 0.05%, vs hydrocortisone, 1%, for alopecia areata in children: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol 2014;150(1):47–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Montes LF. Topical halcinonide in alopecia areata and in alopecia totalis. J Cutan Pathol 1977;4(2):47–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Borchert M, Bruce S, Wirta D, et al. An evaluation of the safety and efficacy of bimatoprost for eyelash growth in pediatric subjects. Clin Ophthalmol 2016;10:419–429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Li AW, Antaya RJ. Successful treatment of pediatric alopecia areata of the scalp using topical bimatoprost. Pediatr Dermatol 2016;33(5):e282–e283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zaheri S, Hughes B. Successful use of bimatoprost in the treatment of alopecia of the eyelashes. Clin Exp Dermatol 2010;35(4):e161–e162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yadav S, Dogra S, Kaur I. An unusual anatomical colocalization of alopecia areata and vitiligo in a child, and improvement during treatment with topical prostaglandin E2. Clin Exp Dermatol 2009;34(8):e1010–e1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mehta JS, Raman J, Gupta N, Thoung D. Cutaneous latanoprost in the treatment of alopecia areata. Eye 2003;17(3):444–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Seo J, Lee YI, Hwang S, Zheng Z, Kim DY. Intramuscular triamcinolone acetonide: an undervalued option for refractory alopecia areata. J Dermatol 2017;44(2):173–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sato-Kawamura M, Aiba S, Tagami H. Acute diffuse and total alopecia of the female scalp. A new subtype of diffuse alopecia areata that has a favorable prognosis. Dermatology 2002;205(4):367–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Michalowski R, Kuczynska L. Long-term intramuscular triamcinolon-acetonide therapy in alopecia areata totalis and universalis. Arch Dermatol Res 1978;261(1):73–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Anuset D, Perceau G, Bernard P, Reguiai Z. Efficacy and safety of methotrexate combined with low- to moderate-dose corticosteroids for severe alopecia areata. Dermatology 2016;232(2):242–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gensure RC. Clinical response to combined therapy of cyclosporine and prednisone. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc 2013;16(1):S58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kim BJ, Uk min S, Park KY, et al. Combination therapy of cyclosporine and methylprednisolone on severe alopecia areata. J Dermatol Treat 2008;19(4):216–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Camacho FM, Garcia-Hernandez MJ. Zinc aspartate, biotin, and clobetasol propionate in the treatment of alopecia areata in childhood. Pediatr Dermatol 1999; 16(4):336–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Alabdulkareem AS, Abahussein AA, Okoro A. Severe alopecia areata treated with systemic corticosteroids. Int J Dermatol 1998;37(8):622–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Schindler AM. The boy whose hair came back. Hosp Pract 1987;22(9):185–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Unger WP, Schemmer RJ. Corticosteroids in the treatment of alopecia totalis. Systemic effects. Arch Dermatol 1978; 114(10):1486–1490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Winter RJ, Kern F, Blizzard RM. Prednisone therapy for alopecia areata. A follow-up report. Arch Dermatol 1976; 112(11):1549–1552. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chong JH, Taieb A, Morice-Picard F, Dutkiewicz AS, Léauté-Labrèze C, Boralevi F. High-dose pulsed corticosteroid therapy combined with methotrexate for severe alopecia areata of childhood. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2017; 31(11):e476–e477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jahn-Bassler K, Bauer WM, Karlhofer F, Vossen MG, Stingl G. Sequential high- and low-dose systemic corticosteroid therapy for severe childhood alopecia areata. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 2017;15(1):42–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Smith A, Trüeb RM, Theiler M, Hauser V, Weibel L. High relapse rates despite early intervention with intravenous methylprednisolone pulse therapy for severe childhood alopecia areata. Pediatr Dermatol 2015;32(4):481–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Friedland R, Tal R, Lapidoth M, Zvulunov A, Ben Amitai D. Pulse corticosteroid therapy for alopecia areata in children: a retrospective study. Dermatology 2013;227(1):37–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Droitcourt C, Milpied B, Ezzedine K, et al. Interest of high-dose pulse corticosteroid therapy combined with methotrexate for severe alopecia areata: a retrospective case series. Dermatology 2012;224(4):369–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sauerbrey A Successful immunsuppression in childhood alopecia areata. Klin Padiatr 2011;223(4):244–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hubiche T, Léauté-Labrèze C, Taïeb A, Boralevi F. Poor long term outcome of severe alopecia areata in children treated with high dose pulse corticosteroid therapy. Br J Dermatol 2008;158(5):1136–1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sethuraman G, Malhotra AK, Sharma VK. Alopecia universalis in Down syndrome: response to therapy. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2006;72(6):454–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bin Saif GA. Oral mega pulse methylprednisolone in alopecia universalis. Saudi Med J 2006;27(5):717–720. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Seiter S, Ugurel S, Tilgen W, Reinhold U. High-dose pulse corticosteroid therapy in the treatment of severe alopecia areata. Dermatology 2001;202(3):230–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sharma VK, Gupta S. Twice weekly 5 mg dexamethasone oral pulse in the treatment of extensive alopecia areata. J Dermatol 1999;26(9):562–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Friedli A, Labarthe MP, Engelhardt E, Feldmann R, Salomon D, Saurat JH. Pulse methylprednisolone therapy for severe alopecia areata: an open prospective study of 45 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol 1998;39(4):597–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sharma VK, Muralidhar S. Treatment of widespread alopecia areata in young patients with monthly oral corticosteroid pulse. Pediatr Dermatol 1998;15(4):313–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kiesch N, Stene JJ, Goens J, Vanhooteghem O, Song M. Pulse steroid therapy for children’s severe alopecia areata? Dermatology 1997;194(4):395–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Perriard-Wolfensberger J, Pasche-Koo F, Mainetti C, Labarthe MP, Salomon D, Saurat JH. Pulse of methylprednisolone in alopecia areata. Dermatology 1993;187(4):282–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Yun D, Silverberg NB, Stein SL. Alopecia areata treated with hydroxychloroquine: a retrospective study of nine pediatric cases. Pediatr Dermatol 2018;35(3):361–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mascia P, Milpied B, Darrigade AS, et al. Azathioprine in combination with methotrexate: a therapeutic alternative in severe and recalcitrant forms of alopecia areata? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2019;33(12):e494–e495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Landis ET, Pichardo-Geisinger RO. Methotrexate for the treatment of pediatric alopecia areata. J Dermatolog Treat 2018;29(2):145–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Batalla A, Flórez Á, Abalde T, Vázquez-Veiga H. Methotrexate in alopecia areata: a report of three cases. Int J Trichology 2016;8(4):188–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lucas P, Bodemer C, Barbarot S, Vabres P, Royer M, Mazereeuw-Hautier J. Methotrexate in severe childhood alopecia areata: long-term follow-up. Acta Derm Venereol 2016;96(1): 102–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Royer M, Bodemer C, Vabres P, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of methotrexate in severe childhood alopecia areata. Br J Dermatol 2011;165(2):407–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kiszewski AE, Bevilaqua M, De Abreu LB. Mesalazine in the treatment of extensive alopecia areata: a new therapeutic option? Int J Trichology 2018;10(3):99–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Rashidi T, Mahd AA. Treatment of persistent alopecia areata with sulfasalazine. Int J Dermatol 2008;47(8):850–852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Bakar O, Gurbuz O. Is there a role for sulfasalazine in the treatment of alopecia areata? J Am Acad Dermatol 2007; 57(4):703–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Aleisa A, Lim Y, Gordon S, et al. Response to ustekinumab in three pediatric patients with alopecia areata. Pediatr Dermatol 2019;36(1):e44–e45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ortolan LS, Kim SR, Crotts S, et al. IL-12/IL-23 neutralization is ineffective for alopecia areata in mice and humans. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2019;144(6):1731–1734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Jabbari A, Dai Z, Xing L, et al. Reversal of alopecia areata following treatment with the JAK1/2 inhibitor baricitinib. EBioMedicine 2015;2(4):351–355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Craiglow BG, King BA. Tofacitinib for the treatment of alopecia areata in preadolescent children. J Am Acad Dermatol 2019;80(2):568–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Dai YX, Chen CC. Tofacitinib therapy for children with severe alopecia areata. J Am Acad Dermatol 2019;80(4):1164–1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Brown L, Skopit S. An excellent response to tofacitinib in a pediatric alopecia patient: a case report and review. J Drugs Dermatol 2018;17(8):914–917. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Patel NU, Oussedik E, Grammenos A, Pichardo-Geisinger R. A case report highlighting the effective treatment of alopecia universalis with tofacitinib in an adolescent and adult patient. J Cutan Med Surg 2018;22(4):439–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Castelo-Soccio L Experience with oral tofacitinib in 8 adolescent patients with alopecia universalis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2017;76(4):754–755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Craiglow BG, Liu LY, King BA. Tofacitinib for the treatment of alopecia areata and variants in adolescents. J Am Acad Dermatol 2017;76(1):29–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Liu LY, King BA. Ruxolitinib for the treatment of severe alopecia areata. J Am Acad Dermatol 2019;80(2):566–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Putterman E, Castelo-Soccio L. Topical 2% tofacitinib for children with alopecia areata, alopecia totalis, and alopecia universalis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2018;78(6):1207–1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Bayart CB, DeNiro KL, Brichta L, Craiglow BG, Sidbury R. Topical Janus kinase inhibitors for the treatment of pediatric alopecia areata. J Am Acad Dermatol 2017;77(1):167–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Craiglow BG, Tavares D, King BA. Topical ruxolitinib for the treatment of alopecia universalis. JAMA Dermatol 2016; 152(4):490–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Fenniche S, Hammami H, Zaouak A. Association of khellin and 308-nm excimer lamp in the treatment of severe alopecia areata in a child. J Cosmet Laser Ther 2018;20(3):156–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Al-Mutairi N 308-nm excimer laser for the treatment of alopecia areata in children. Pediatr Dermatol 2009;26(5):547–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Al-Mutairi N 308-nm excimer laser for the treatment of alopecia areata. Dermatol Surg 2007;33(12):1483–1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Zakaria W, Passeron T, Ostovari N, Lacour JP, Ortonne JP. 308-nm excimer laser therapy in alopecia areata. J Am Acad Dermatol 2004;51(5):837–838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Jury CS, McHenry P, Burden AD, Lever R, Bilsland D. Narrowband ultraviolet B (UVB) phototherapy in children. Clin Exp Dermatol 2006;31(2):196–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Ersoy-Evans S, Altaykan A, Sahin S, Kolemen F. Phototherapy in childhood. Pediatr Dermatol 2008;25(6):599–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Yoon TY, Kim YG. Infant alopecia universalis: role of topical PUVA (psoralen ultraviolet A) radiation. Int J Dermatol 2005; 44(12):1065–1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Mitchell AJ, Douglass MC. Topical photochemotherapy for alopecia areata. J Am Acad Dermatol 1985;12(4):644–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Claudy AL, Gagnaire D. PUVA treatment of alopecia areata. Arch Dermatol 1983;119(12):975–978. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Amer MA, El Garf A. Photochemotherapy and alopecia areata. Int J Dermatol 1983;22(4):245–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Lux-Battistelli C. Combination therapy with zinc gluconate and PUVA for alopecia areata totalis: an adjunctive but crucial role of zinc supplementation. Dermatol Ther 2015; 28(4):235–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Majumdar B, De A, Ghosh S, et al. ‘‘Turban PUVAsol:’’ A simple, novel, effective, and safe treatment option for advanced and refractory cases of alopecia areata. Int J Trichology 2018;10(3):124–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Belezos NK. Local estrogen and ultraviolet irradiation in the treatment of total alopecia (areata). Dermatologica 1965; 131(4):304–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Shapiro J Current treatment of alopecia areata. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc 2013;16(1):S42–S44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Lee S, Kim BJ, Lee YB, Lee WS. Hair regrowth outcomes of contact immunotherapy for patients with alopecia areata: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatol 2018; 154(10):1145–1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Singh G, Lavanya M. Topical immunotherapy in alopecia areata. Int J Trichology 2010;2(1):36–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Zawar VP, Karad GM. Liquid nitrogen cryotherapy in recalcitrant alopecia areata: a study of 11 patients. Int J Trichology 2016;8(1):15–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Stoehr JR, Choi JN, Colavincenzo M, Vanderweil S. Off-label use of topical minoxidil in alopecia: a review. Am J Clin Dermatol 2019;20(2):237–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Suchonwanit P, Thammarucha S, Leerunyakul K. Minoxidil and its use in hair disorders: a review. Drug Des Devel Ther 2019;13:2777–2786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Price VH. Therapy of alopecia areata: on the cusp and in the future. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc 2003;8(2):207–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Kumaresan M Intralesional steroids for alopecia areata. Int J Trichology 2010;2(1):63–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Coronel-Pérez IM, Rodŕıguez-Rey EM, Camacho-Martínez FM. Latanoprost in the treatment of eyelash alopecia in alopecia areata universalis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2010;24(4): 481–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Shreberk-Hassidim R, Ramot Y, Gilula Z, Zlotogorski A. A systematic review of pulse steroid therapy for alopecia areata. J Am Acad Dermatol 2016;74(2):372–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Efentaki P, Altenburg A, Haerting J, Zouboulis CC. Medium-dose prednisolone pulse therapy in alopecia areata. Dermatoendocrinol 2009;1(6):310–313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Phan K, Ramachandran V, Sebaratnam DF. Methotrexate for alopecia areata: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2019;80(1):120–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Aghaei S An uncontrolled, open label study of sulfasalazine in severe alopecia areata. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2008;74(6):611–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Guttman-Yassky E, Ungar B, Noda S, et al. Extensive alopecia areata is reversed by IL-12/IL-23p40 cytokine antagonism. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2016;137(1):301–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Gilhar A, Keren A, Paus R. JAK inhibitors and alopecia areata. Lancet 2019;393(10169):318–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133. Accessed October, 2019. https://www.clinicaltrials.gov.

- 134.Howell MD, Kuo FI, Smith PA. Targeting the Janus kinase family in autoimmune skin diseases. Front Immunol 2019;10:2342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Mlacker S, Aldahan AS, Simmons BJ, et al. A review on laser and light-based therapies for alopecia areata. J Cosmet Laser Ther 2017;19(2):93–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Messenger AG, McKillop J, Farrant P, McDonagh AJ, Sladden M. British Association of Dermatologists’ guidelines for the management of alopecia areata 2012. Br J Dermatol 2012;166(5):916–926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Goldberg LJ, Castelo-Soccio LA. Alopecia: kids are not just little people. Clin Dermatol 2015;33(6):622–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Vivar KL, Kruse L. The impact of pediatric skin disease on self-esteem. Int J Womens Dermatol 2018;4(1):27–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.