Abstract

Giardia intestinalis and Blastocystis hominis cause frequent infections in children in developing countries. However, the role of intestinal inflammation in their pathogenesis is still poorly understood. Faecal calprotectin (FC) level is used as an indicator of intestinal inflammation and neutrophil migration in the intestinal tract. The present study aimed to evaluate intestinal inflammation by measuring FC level among children infected with either G. intestinalis or B. hominis before and after treatment. Stool samples were collected from 282 children inhabiting a rural area in Egypt and examined microscopically for intestinal parasites. FC level was estimated in a group of children infected with G. intestinalis (n = 12) or B. hominis (n = 12) before and 3 weeks after receiving nitazoxanide (200 mg twice daily for 3 days) and compared to a control group (n = 18) of parasite-free children. Cases of mixed infection were excluded. Nitazoxanide cure rate was 83% in both infections with a remarkable reduction of infection intensity in uncured children. The difference in FC levels between infected children and controls was not statistically significant. Also, the difference between the pre- and post-treatment estimations was not statistically significant. Elevated levels were observed before treatment in three children (two infected with G. intestinalis and one with B. hominis) who displayed normal post-treatment levels. Although G. intestinalis and B. hominis infections appear to cause no remarkable intestinal inflammation, they may induce abnormally elevated FC levels in a subset of children.

Keywords: Giardia, Blastocystis, Children, Calprotectin, Intestinal inflammation

Introduction

Enteric protozoa constitute a diverse group of unicellular microparasites colonizing the intestinal tract of high vertebrate hosts including humans. They are transmitted through ingestion of cysts/oocysts in contaminated food or water or through the person-to-person route (Fletcher et al. 2012). Inadequate sanitary conditions facilitate the dissemination of infection in developing countries. Several species of intestinal protozoa are linked to gastrointestinal symptoms in humans worldwide. The flagellate Giardia intestinalis and the stramenopile Blastocystis hominis are the most frequent and affect mainly young children in endemic areas with high rates of reinfection (Cama and Mathison 2015). However, the pathogenesis and host-parasite interaction of these infections are still poorly understood (Podewils et al. 2004; Torgerson et al. 2014).

Intestinal colonization by G. intestinalis causes villous flattening or atrophy and microvillus shortening although it is frequently asymptomatic (Farthing et al. 2009). The role of intestinal inflammation in giardiasis is unclear. Experimental infection with G. intestinalis has demonstrated neutrophilic infiltration in the jejunum during colonization (Chen et al. 2013). However, the absence of significant mucosal inflammation was reported in G. intestinalis infected individuals (Campbell et al. 2004). Blastocystis hominis has been linked to irritable bowel syndrome (Yakoob et al. 2010). Histologic examination of the caecum and colon of a murine model of B. hominis showed marked inflammatory cell infiltration with oedema of the lamina propria and sloughing of the mucosal layer (Moe et al. 1997).

One of the commonly used markers of intestinal inflammation is faecal calprotectin (FC). It is a 36.5 kDa oligomer of one heavy and two light subunits. It constitutes 5% of the total protein and 60% of the cytosolic protein in neutrophils and it is also found in monocytes and macrophages (Pathirana et al. 2018; Haisma et al. 2019). Assessment of FC level plays a pivotal role in the workup evaluation of patients with chronic diarrhea (Carrasco-Labra et al. 2019). It is mainly used as a marker for primary screening and follow-up of patients with inflammatory bowel diseases with 95% sensitivity and 91% specificity (Henderson et al. 2014; van Rheenen et al. 2010). An elevated level of FC is also found in allergic colitis, drug-induced enteropathy, and colorectal cancer (Hanevik et al. 2007; Damms and Bischoff 2008; Schoepfer et al. 2008). Elevated levels are also induced by gastrointestinal pathogens (Lam et al. 2014). The contribution of intestinal parasitic infections to intestinal inflammation and changes in FC levels in endemic areas is unclear. The present study aimed to estimate FC level before and after treatment of G. intestinalis and B. hominis infection among children residing in an Egyptian rural area.

Material and methods

Study subjects

A cross-sectional community-based survey was carried out to detect G. intestinalis and B. hominis infection among 282 children aged 6–12 years residing in a rural area in Alexandria, Egypt. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Medical Research Institute, Alexandria University, Egypt. Oral informed consent for participation in the study was obtained from parents /guardians of children.

Collection and examination of stool samples

Fresh stool samples were collected and examined using the formalin ethyl acetate concentration (FEAC) technique to detect intestinal parasitic infection (Garcia 2016). The intensity of G. intestinalis and B. hominis infection were estimated by the number of organisms/10 HPF as follows: few ≤ 2; moderate 3–9 and heavy ≥ 10.

Stool samples of G. intestinalis and B. hominis positive children showing no other detectable parasites by FEAC were further examined using Kato-Katz and modified Ziehl–Neelsen stain to exclude associated helminthic and coccidial infections respectively. Fresh stool samples microscopically negative for B. hominis were cultured in Jones' medium and examined 48–72 h later to confirm the absence of B. hominis infection (Zhang et al. 2012).

FC level

Children infected with G. intestinalis, a corresponding group of children with B. hominis infection, and a control group of parasite-free children were subjected to history taking, clinical examination, and estimation of faecal calprotectin level. Children with mixed parasitic infection, including combined G. intestinalis and B. hominis infection, children with known chronic diseases such as diabetes mellitus and chronic kidney diseases, and those who have received antibiotics or anti-inflammatory drugs within 2 weeks before the study were excluded. Infected children received nitazoxanide in a dose of 200 mg twice daily for 3 days under medical supervision. Treated children were revaluated 3 weeks post-treatment for improvement of symptoms, parasitological cure and FC level.

FC level was estimated using sandwich enzyme-linked immune- sorbent (ELISA) Calprest R kit (Eurospital, Trieste, Italy; REF:9031). Fresh stool samples were mixed with the extraction solution provided by the kit and stored at − 20 °C for later measurement. Levels above 150 mg/kg stool were considered abnormally elevated (D'Angelo et al. 2017).

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed using the statistical package for social sciences (SPSS, version 17.0, 2006; SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA). Chi-square test was used to study age and gender distribution of infection. Improvement of symptoms after treatment was analyzed by the Marginal Homogeneity Test. FC level analyzed using Mann Whitney test for comparison between two groups and Kruskal Wallis for more than two groups and Wilcoxon signed ranks to compare measurements before and after treatment.

Results

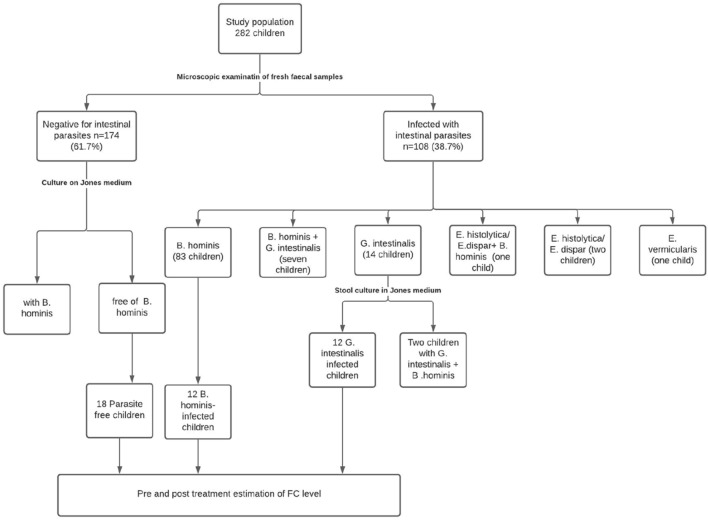

Out of 282 examined children, 108 children (38.2%) were infected with one or more intestinal parasites. Blastocystis hominis was the most frequent (91 children, 32.2%) followed by G. intestinalis (21 children, 7.4%). Among children infected with G. intestinalis (n = 21), nine children (42.9%) had mixed infection with B. hominis. Parasites detected in the study population and the children eligible for estimation of FC level are shown in Fig. 1. There was no significant age or gender differences in both G. intestinalis and B. hominis infections (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Flow chart showing parasites detected in the study population and the groups evaluated for FC level

Table 1.

Giardia and Blastocystis infection among the examined children according to age and gender

| No. examined | G. intestinalis | B. hominis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | % | No | % | ||

| Age (years) | |||||

| 6–8 | 156 | 10 | 6.4 | 46 | 29.5 |

| 9–10 | 74 | 6 | 8.1 | 26 | 35.1 |

| 11–12 | 52 | 5 | 9.6 | 19 | 36.5 |

| p | 0.748 | 0.559 | |||

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 140 | 13 | 9.3 | 44 | 31.4 |

| Female | 142 | 8 | 5.6 | 47 | 33.1 |

| p | 0.243 | 0.764 | |||

p: p value for comparing between the different categories. Diagnosis was based on microscopic examination of stool samples using FEAC technique

Cure rates were assessed in 12 G. intestinalis and 12 B. hominis infected children 3 weeks after nitazoxanide treatment. Before treatment, G. intestinalis infection among these children was mild in two, moderate in five, and heavy in five children whereas B. hominis infection was mild in one, moderate in three, and heavy in eight children. The overall cure rate for each parasite was 83.3% (10 out of 12 children). Treatment failure was recorded in two (out of 5) children with heavy Giardia infection and two (out of 8) children with heavy B. hominis infection (Fig. 2). All uncured children showed a reduction in infection intensity.

Fig. 2.

Nitazoxanide cure rate in G. intestinalis and B. hominis infected children according to intensity of infection

All treated children were complaining of abdominal pain before receiving nitazoxanide. Significant improvement occurred after receiving nitazoxanide where nine G. intestinalis infections (75%) and 11 B. hominis infections (91.7%) became asymptomatic (p < 0.05) (Table 2). Abdominal pain persisted in children with uncured G. intestinalis infection (n = 2) and in one of the two children with uncured B. hominis. However, abdominal pain also persisted in one child after elimination of G. intestinalis.

Table 2.

Improvement of symptoms in Giardia and Blastocystis infected children 3 weeks after nitazoxanide treatment

| Symptoms | G. intestinalis (n = 12) | B. hominis (n = 12) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | % | No | % | |

| Before treatment | ||||

| Asymptomatic | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Symptomatic | 12 | 100.0 | 12 | 100.0 |

| After treatment | ||||

| Asymptomatic | 9 | 75.0 | 11 | 91.7 |

| Symptomatic | 3 | 25.0 | 1 | 8.3 |

| MHp | 0.003* | 0.001* | ||

MHp: p value of Marginal Homogeneity Test

*Statistically significant at p ≤ 0.05

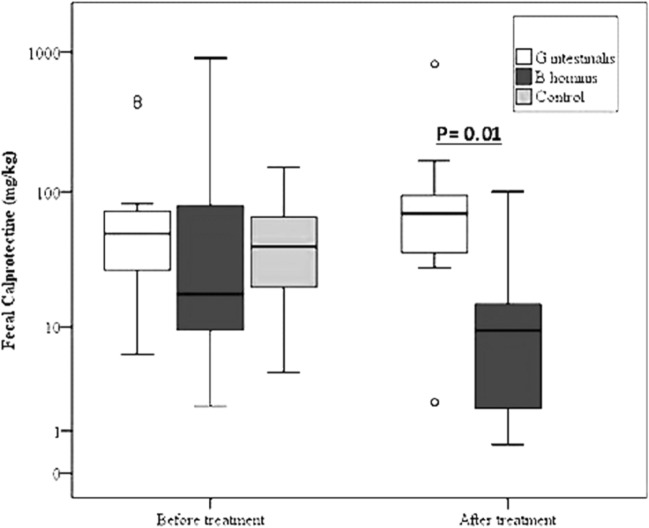

Among G. intestinalis infected children, FC levels ranged from 6 to 460 mg/kg. The median value was slightly higher than that of the control (50 vs 40 mg/kg, p > 0.05). Only two G. intestinalis-infected children displayed abnormally elevated levels. After nitazoxanide treatment, the level ranged from 2.2 to 820 mg/kg and the median value was non-significantly elevated compared to the pretreatment value (70 vs 50 mg/kg). Elevated post-treatment levels were recorded in two children, one of them continued to excrete few G. intestinalis cysts.

Among B. hominis infected pre-treated children, FC level showed a wide range (2–900 mg/kg) and the median value was lower than that of the control (18.6 and 40 mg/ kg respectively) with a non-significant difference. Abnormally elevated levels were found in three children. After nitazoxanide treatment, lower median FC level was observed (9.4 vs 18.6 mg/ kg, p = 0.06) and all children displayed normal FC level ranging from 60 to 100 mg/kg. Of note, G. intestinalis infected children displayed significantly higher post-treatment FC levels than B. hominis infected children (p = 0.01) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

FC levels (mg/kg) in children infected with Giardia (n = 12) and Blastocystis (n = 12) compared to healthy controls (n = 17) and the corresponding post-treatment levels in infected children

Based on our objective to estimate the changes in fecal calprotectin level (mg/kg) in B. hominis infected children 3 weeks after nitazoxanide treatment, we calculated post-hoc power analysis and concluded 90% power of our study to determine the median difference of fecal calprotectin before treatment (18.6, Range: 2–900) and after treatment (median 9.4, range 0.60–100.0). Power analysis was calculated after non-parametric correction of the Independent sample t-test at 0.05 significance level using R software.

Discussion

Giardia intestinalis and B. hominis infections are common worldwide. Rates of infection in the current study are relatively higher than those reported in developed countries (Harhay et al. 2010) but concur with a previous study in Egypt indicating a constant unchanging pattern of infection (Omaran et al. 2013). Neither age nor gender-related differences were detected suggesting equal exposure and/or susceptibility to infection. Generally, dissemination of intestinal protozoa reflects the sanitary, hygienic, and socio-economic standards of the population as they are transmitted primarily through the faeco-oral route (Fletcher et al. 2012).

The parasitological and clinical cure rates of nitazoxanide observed in the present study agree with previous reports which reported that nitazoxanide rapidly and efficiently reduced the duration of illness in G. intestinalis infected patients even before the parasitological cure was achieved (Rossignol et al. 2005; Escobedo and Cimerman 2007; Ordóñez-Mena et al. 2018). Treatment failure that was observed in four children may be attributed to high infection intensity and/or variable drug sensitivity among genetically different isolates. An in vitro study illustrated that nitazoxanide had highest efficacy against Blastocystis subtype 1 isolate at 0.1 mg/ml. However, at an increased concentration, subtype 5 was more sensitive to the treatment with an efficacy of 95.1% (Rossignol et al. 2012; Girish et al. 2015).

Despite significant improvement of symptoms in nitazoxanide-treated children, abdominal pain persisted after clearance of G. intestinalis infection in one child. A similar observation was previously reported after treatment of G. intestinalis infection acquired in a waterborne outbreak. Possible explanations include bacterial overgrowth, prolonged lactose intolerance, or post-infectious functional disorder (Hanevik et al. 2007).

High calprotectin level in feces is an indicator of neutrophil migration towards the intestinal tract and it correlates with the degree of intestinal mucosal inflammation (D'Angelo et al. 2017). Data of the present study indicate that G. intestinalis and B. hominis infection had no significant impact on calprotectin levels in children. The present result is consistent with a recent study in rural Bangladesh demonstrating a non-significant association between the presence of G. intestinalis in stool and high FC among 203 children (George et al. 2018). Among Guatemalan children, neither the presence nor the intensity of G. intestinalis infection had an association with FC (Soto-Méndez et al. 2016). Fecal myeloperoxidase, another marker of neutrophil inflammation, was found to be unexpectedly lower in children with giardiasis (McCormick et al. 2017). Other authors suggested that G. intestinalis infection is classically characterized by little or no inflammatory intestinal response (Roxström-Lindquist et al. 2006).

Regarding B. hominis, a recent study in Italy found no association between B. hominis colonization and FC level in both symptomatic and asymptomatic patients (Sulekova et al. 2018). Nieves-Ramírez et al. (2018) detected even a significantly lower calprotectin concentration among B. hominis colonized compared to non-colonized persons. In contrast to these studies, Tibble et al. (2002) examined eight children with infectious diarrhea, with seven having confirmed giardiasis and observed excess FC level.

The extent of gut inflammation may be related to the clinical presentation of the studied patients. All children included in the present study were complaining of abdominal pain and none had diarrhea. Sulekova et al. (2018) found that FC level in B. hominis infection was significantly higher in patients with diarrhea than in the asymptomatic group or those with other gastrointestinal symptoms. They suggested the use of calprotectin as a marker for B. hominis pathogenicity. Furthermore, the present study was carried out in an endemic area with possibly high rates of reinfection. Reduction in inflammatory response and protection against disease severity probably occur with recurrent G. intestinalis infection (Kohli et al. 2008).

Abnormally elevated FC levels were observed in the present study in few children (two infected with G. intestinalis and three with B. hominis. Similarly, A study in Iraq reported FC positive test results in 10 out of 47 G. intestinalis cases and in one out of 31 B. hominis positive samples (Salman et al. 2017). In an Australian study, mild inflammation of the duodenal mucosa was observed in only 3.7% of 567 G. intestinalis patients (Oberhuber et al. 1997).

The parasite genotype may determine the degree of intestinal inflammation. Giardia intestinalis assemblage B has been linked to extensive mucosal damage and infiltration by inflammatory cells while G. intestinalis assemblage A does not induce overt intestinal pro-inflammatory responses and may attenuate intestinal neutrophil recruitment (Campbell et al. 2004; Cotton et al. 2014). Differential induction of the anti-inflammatory cytokine, IL-10 by Blastocystis subtypes was also reported (Yakoob et al. 2014).

Post-treatment FC level was higher in G. intestinalis infected than in B. hominis infected children. Moreover, a slightly elevated FC level was observed in a G. intestinalis infected child despite clearance of infection. Slow recovery of mucosal inflammation was previously reported following treatment of G. intestinalis infection acquired in an outbreak (Asseman et al. 1999). A histopathological study using murine models demonstrated increased neutrophils infiltration and myeloperoxidase activity throughout the gut, 35 days after Giardia elimination (Campbell et al. 2004). On the other hand, the normal post-treatment FC level in B. hominis infected children denotes recovery of all affected children.

A limitation in the study was the difficulty in recruiting children with single Giardia infection; associated Blastocystis infection was detected in 9 out of 21 Giardia infected children (42.9%) using the direct microscopic method and culture in Jones's medium. Due to the small number of children with a single infection who were initially examined for FC level, the pre and post-treatment comparison was performed to confirm the study findings.

In conclusion, both G. intestinalis and B. hominis infections appear to cause no remarkable intestinal inflammation. However, they may elicit abnormally elevated levels in a subset of children who may be erroneously diagnosed as having inflammatory bowel disease.

Funding

No fund was obtained for the execution of the study.

Availability of data and materials

The data supporting the findings of this study are contained within the manuscript. The raw data are available by the corresponding author when requested.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

No conflict of interest to declare.

Consent to participate

Verbal consent was obtained from all participants (parents /guardians of children).

Consent for publication

All authors agree for publication.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Medical Research Institute (MRI), Alexandria University (IORG 0008812). All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Asseman C, Mauze S, Leach MW, Coffman RL, Powrie F. An essential role for interleukin 10 in the function of regulatory T cells that inhibit intestinal inflammation. J Exp Med. 1999;190(7):995–1004. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.7.995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cama VA, Mathison BA. Infections by Intestinal Coccidia and Giardia duodenalis. Clin Lab Med. 2015;35(2):423–444. doi: 10.1016/j.cll.2015.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell DI, McPhail G, Lunn PG, Elia M, Jeffries DJ. Intestinal inflammation measured by fecal neopterin in Gambian children with enteropathy: association with growth failure, Giardia lamblia, and intestinal permeability. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2004;39(2):153–157. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200408000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrasco-Labra A, Lytvyn L, Falck-Ytter Y, Surawicz CM, Chey WD. AGA technical review on the evaluation of functional diarrhea and diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome in adults (IBS-D) Gastroenterology. 2019;157(3):859–880. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen TL, Chen S, Wu HW, et al. Persistent gut barrier damage and commensal bacterial influx following eradication of Giardia infection in mice. Gut Pathog. 2013;5(1):26. doi: 10.1186/1757-4749-5-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotton JA, Motta JP, Schenck LP, Hirota SA, Beck PL, Buret AG. Giardia duodenalis infection reduces granulocyte infiltration in an in vivo model of bacterial toxin-induced colitis and attenuates inflammation in human intestinal tissue. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(10):e109087. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0109087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damms A, Bischoff SC. Validation and clinical significance of a new calprotectin rapid test for the diagnosis of gastrointestinal diseases. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2008;23(10):985–992. doi: 10.1007/s00384-008-0506-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Angelo F, Felley C, Frossard JL. Calprotectin in daily practice: where do we stand in 2017? Digestion. 2017;95:293–301. doi: 10.1159/000476062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escobedo AA, Cimerman S. Giardiasis: a pharmacotherapy review. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2007;8(12):1885–1902. doi: 10.1517/14656566.8.12.1885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farthing MJ, Cevallos AM, Kelly P. Intestinal protozoa. In: Cook GC, Zumla AL, editors. Manson’s tropical diseases. 22. London: Elsevier; 2009. pp. 1375–1406. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher SM, Stark D, Harkness J, Ellis J. Enteric protozoa in the developed world: a public health perspective. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2012;25(3):420–449. doi: 10.1128/CMR.05038-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia LS. Macroscopic and microscopic examination of fecal specimens. In: Garcia LS, editor. Diagnostic medical parasitology. 6. Washington, DC: ASM Press; 2016. pp. 782–830. [Google Scholar]

- George CM, Burrowes V, Perin J, et al. Enteric infections in young children are associated with environmental enteropathy and impaired growth. Trop Med Int Health. 2018;23(1):26–33. doi: 10.1111/tmi.13002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girish S, Kumar S, Aminudin N, Ali T. (Eurycoma longifolia): a possible therapeutic candidate against Blastocystis sp. Parasit Vectors. 2015;8:332. doi: 10.1186/s13071-015-0942-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haisma SM, van Rheenen PF, Wagenmakers L, Kobold AM. Calprotectin instability may lead to undertreatment in children with IBD. Arch Dis Child. 2019 doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2018-316584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanevik K, Hausken T, Morken MH, et al. Persisting symptoms and duodenal inflammation related to Giardia duodenalis infection. J Infect. 2007;55(6):524–530. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2007.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harhay MO, Horton J, Olliaro PL. Epidemiology and control of human gastrointestinal parasites in children. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2010;8(2):219–234. doi: 10.1586/eri.09.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson P, Anderson NH, Wilson DC. The diagnostic accuracy of fecal calprotectin during the investigation of suspected pediatric inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109(5):637–645. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohli A, Bushen OY, Pinkerton RC, et al. Giardia duodenalis assemblage, clinical presentation and markers of intestinal inflammation in Brazilian children. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2008;102(7):718–725. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam YA, Warouw SM, Wahani AMI, Manoppo JIC, Salendu PM. Correlation between gut pathogens and fecal calprotectin levels in young children with acute diarrhea. Paediatr Indones. 2014;54(4):193–197. doi: 10.14238/pi54.4.2014.193-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick BJJ, Lee GO, Seidman JC, et al. Dynamics and trends in fecal biomarkers of gut function in children from 1–24 months in the MAL-ED study. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2017;96(2):465–472. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.16-0496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moe KT, Singh M, Howe J, et al. Experimental Blastocystis hominis infection in laboratory mice. Parasitol Res. 1997;83(4):319–325. doi: 10.1007/s004360050256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieves-Ramírez ME, Partida-Rodríguez O, Laforest-Lapointe I et al (2018) Asymptomatic intestinal colonization with protist Blastocystis is strongly associated with distinct microbiome ecological patterns. mSystems 3(3):e00007–18. 10.1128/mSystems.00007-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Oberhuber G, Kastner N, Stolte M. Giardiasis: a histologic analysis of 567 cases. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1997;32(1):48–51. doi: 10.3109/00365529709025062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omaran EK, Hamed AF, Yousef MA. Common parasitic infection among rural population Sohag Governorate. Egypt J Am Sci. 2013;9(4):596–601. [Google Scholar]

- Ordóñez-Mena JM, McCarthy ND, Fanshawe TR. Comparative efficacy of drugs for treating giardiasis: a systematic update of the literature and network meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2018;73(3):596–606. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkx430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pathirana WGW, Chubb SP, Gillett MJ, Vasikaran SD. Faecal calprotectin. Clin Biochem Rev. 2018;39(3):77–90. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podewils LJ, Mintz ED, Nataro JP, Parashar UD. Acute, infectious diarrhea among children in developing countries. Semin Pediatr Infect Dis. 2004;15(3):155–168. doi: 10.1053/j.spid.2004.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossignol JF, Kabil SM, Said M, Samir H, Younis AM. Effect of nitazoxanide in persistent diarrhea and enteritis associated with Blastocystis hominis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3(10):987–991. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(05)00427-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossignol JF, Lopez-Chegne N, Julcamoro LM, Carrion ME, Bardin MC. Nitazoxanide for the empiric treatment of pediatric infectious diarrhea. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2012;106(3):167–173. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2011.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roxström-Lindquist K, Palm D, Reiner D, Ringqvist E, Svärd SG. Giardia immunity—an update. Trends Parasitol. 2006;22(1):26–31. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2005.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salman YJ, Ali CA, Razaq AAA. Fecal calprotectin among patients infected with some protozoan infections. Int J Curr Microbiol App Sci. 2017;6(6):3258–3274. doi: 10.20546/ijcmas.2017.606.384. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schoepfer AM, Trummler M, Seeholzer P, Seibold-Schmid B, Seibold F. Discriminating IBD from IBS: comparison of the test performance of fecal markers, blood leukocytes, CRP, and IBD antibodies. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14(1):32–39. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soto-Méndez MJ, Aguilera CM, Mesa MD, et al. Interaction of Giardia intestinalis and systemic oxidation in preschool children in the western highlands of Guatemala. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2016;63(1):118–122. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000000891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulekova LF, De Angelis M, Milardi G et al (2018) Clinical and epidemiological profile of patients with Blastocystis spp and evaluation of faecal calprotectin as potential surrogate marker of pathogenicity. In: 28th ECCMID European congress of clinical microbiology and infectious diseases. Madrid, Spain, 21–24 April, P1328

- Tibble JA, Sigthorsson G, Foster R, Forgacs I, Bjarnason I. Use of surrogate markers of inflammation and Rome criteria to distinguish organic from nonorganic intestinal disease. Gastroenterology. 2002;123(2):450–460. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.34755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torgerson PR, de Silva NR, Fèvre EM, et al. The global burden of foodborne parasitic diseases: an update. Trends Parasitol. 2014;30(1):20–26. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Rheenen PF, Van de Vijver E, Fidler V. Faecal calprotectin for screening of patients with suspected inflammatory bowel disease: diagnostic meta-analysis. BMJ. 2010;341:c3369. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c3369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yakoob J, Jafri W, Beg MA et al (2010) Irritable bowel syndrome: is it associated with genotypes of Blastocystis hominis [published correction appears in Parasitol Res 2011 Dec;109(6):1745]. Parasitol Res 106(5):1033–1038. 10.1007/s00436-010-1761-x [DOI] [PubMed]

- Yakoob J, Abbas Z, Usman MW, et al. Cytokine changes in colonic mucosa associated with Blastocystis spp. subtypes 1 and 3 in diarrhoea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Parasitology. 2014;141(7):957–969. doi: 10.1017/S003118201300173X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Qiao J, Wu X, Da R, Zhao L, Wei Z. In vitro culture of blastocystis hominis in three liquid media and its usefulness in the diagnosis of blastocystosis. Int J Infect Dis. 2012;16(1):e23–e28. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2011.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are contained within the manuscript. The raw data are available by the corresponding author when requested.

Not applicable.