Abstract

Background

SARS-CoV-2 vaccines are an invaluable resource against COVID-19. Current vaccine shortage makes it necessary to prioritize distribution to the most appropriate segments of the population.

Methods

This is a prospective cohort study of 63 health care workers (HCWs) from a General Hospital. We compared antibody responses to two doses of BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine between HCWs with previous SARS-CoV-2 infection (experienced HCWs) and HCWs without previous infection (naïve HCWs).

Findings

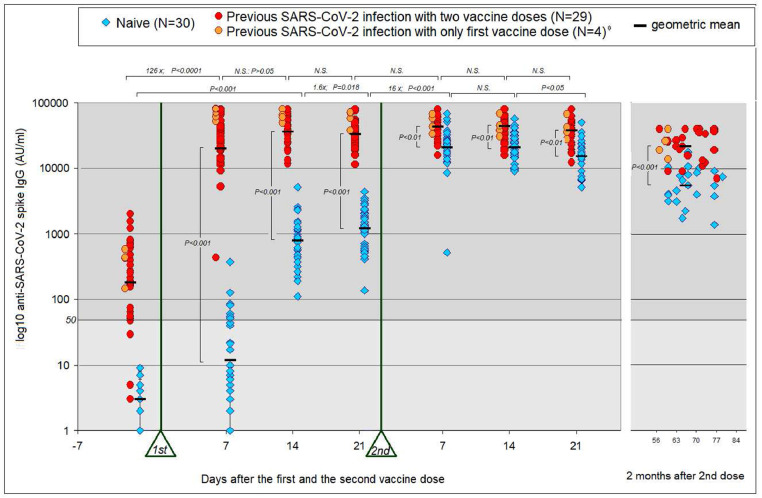

Seven days after the first vaccine dose, HCWs with previous infection experienced a 126-fold increase in antibody levels (p<0·001). However, in the HCW naïve group, response was much lower and only five showed positive antibody levels (>50 AU). After the second dose, no significant increase in antibody levels was found in experienced HCWs, whereas in naïve HCWs, levels increased by 16-fold (p<0·001). Approximately two months post-vaccination, antibody levels were much lower in naïve HCWs compared to experienced HCWs (p<0·001).

Interpretation

The study shows that at least ten months post-COVID-19 infection, the immune system is still capable of producing a rapid and powerful secondary antibody response following one single vaccine dose. Additionally, we found no further improvement in antibody response to the second dose in COVID-19 experienced HCWs. Nonetheless, two months later, antibody levels were still higher for experienced HCWs. These data suggest that immune memory persists in recovered individuals; therefore, the second dose of the COVID-19 vaccine in this group could be postponed until immunization of the remaining population is complete.

Keywords: Previous SARS-CoV-2 infection, SARS-CoV-2 vaccines, Secondary antibody response, Immune memory

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

Vaccines developed against COVID-19 have provided great public health benefits by protecting the global population from deadly SARS-CoV-2. Most countries have prioritized vaccine distribution to the most susceptible subgroups of the population. However, given the shortage of vaccine supplies, a more accurate vaccine prioritization is urgently required to achieve the highest healthcare benefits. Current vaccine administration protocols are based on results from clinical trials of individuals without previous COVID-19 infection. Recommendations, however, include individuals recovered from COVID-19 as candidates for vaccination, despite the low rate of reinfection in these individuals shown in cohort studies.

Added value of this study

In our study, we compared antibody responses to two doses of BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine between health care workers HCWs with SARS-CoV-2 infection before vaccination (experienced HCWs) and HCWs without previous infection (naïve HCWs). We report that ten months after diagnosis of COVID-19, experienced HCWs still showed an early and intense antibody response to the first dose of the vaccine. This was true even for those COVID-19 recovered individuals who were negative for anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies prior to vaccination. A second dose did not further improve the antibody response in COVID-19 recovered individuals. In contrast, naïve HCWs needed the second dose to reach their peak anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibody levels, but their levels were still lower than peak levels from experienced HCWs. Moreover, the anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibody levels two months after the end of the vaccination protocol remained higher in experienced HCWs vs. naïve HCWs.

Implications of all the available evidence

Our study confirms previous data regarding the antibody response from COVID-19 recovered individuals following vaccination and provides new and stronger evidence suggesting that immune memory persists over a long time in the recovered population. Therefore, we recommend a change in vaccination policy: the second dose of the COVID-19 vaccine in recovered individuals can be postponed until immunization of the rest of the population is complete.

Alt-text: Unlabelled box

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 mRNA vaccine BNT162b2 has shown up to 95% protection against the disease, although the efficacy study excluded participants with a prior clinical or microbiological diagnosis of COVID-19 disease [1]. Current recommendations, however, include individuals recovered from COVID-19 as candidates for vaccination, despite the low rate of reinfection in these individuals shown in cohort studies [2,4].

An urgent challenge is optimizing vaccine allocation in order to maximize public health benefits. We intend to show that individuals with previous SARS-CoV-2 infection should not be a priority group to receive the vaccine, or, alternatively, it would be sufficient for them to receive one single dose. To achieve this objective, we measured serum anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibody levels as a marker of immune response and compared antibody levels in HCWs with and without a history of COVID-19 infection. Samples were taken every seven days for three weeks, after the first and second doses of the BNT162b2 vaccine to monitor the immediate and delayed reaction to vaccine administration. Two months following the second dose of the vaccine, serum samples were obtained again to assess the persistence of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibody levels.

2. Methods

The Albacete General Hospital (CHUA) is a 675-bed hospital located in southeastern Spain, employing 3096 people. In January 2021, the BNT162b2 vaccine was offered to all of them without any prior exclusion and more than 90% of the personnel received the vaccine according to the standard protocol established by the manufacturer (Pfizer). In this observational prospective longitudinal cohort study, 66 health-care workers (HCWs) from the CHUA volunteered to measure their antibody levels before the onset of vaccination and after each of the two doses. The study was approved by the local Clinical Ethics Committee (Internal code: 2021-12 EOm). Informed consent was obtained from all volunteers before sampling. Participants were classified into two groups: “experienced”, which included those previously infected with SARS-CoV-2, and “naïve”, consisting of individuals without previous SARS-CoV-2 infection. The date of diagnosis is that of the first positive PCR or the approximate date on which they presented any symptoms compatible with covid-19 prior to the detection of anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG. None of the individuals in the “naïve” group had clinical or laboratory data suggestive of previous infection. Both groups of participants received the messenger RNA vaccine BNT162b2 (Pfizer–BioNTech).

Total IgG antibody levels (including neutralizing antibodies) against the S1 subunit of the SARS-CoV2 virus spike protein that binds to the receptor binding domain (RBD) were measured using the SARS-CoV-2 IgG II Quant immunoassay in the ARCHITECT i- System (Abbott, Abbott Park, US). The analytical measurement range is from 21·0 to 80,000 AU / mL and we used the manufacturer's recommended cutoff point of 50 AU/mL for determining positivity. To convert AU/ ml into international standard WHO units the conversion factor is 1/7 [5].

To evaluate the kinetics of the immune response, antibody levels were measured at seven time points: a) one day before or following dose one, and at 7, 14 and 21 days following dose one, and b) at 7, 14, and 21 days following dose two. Moreover, to evaluate the persistence of the antibody response, anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies were measured again eight to ten weeks after the second dose of the vaccine.

Total anti- SARS-CoV-2 spike RBD region IgG antibody levels were reported using geometric mean concentrations (GMC) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). Differences in the total IgG levels between the COVID-19 experienced and naïve groups were evaluated using the two-tailed Mann-Whitney U-test. Within group differences in total IgG levels obtained at the different time points were assessed employing the two-tailed Wilcoxon Sign test. The α-level of significance was set at 0.05. Demographic characteristics were expressed as median and range (minimum – maximum values). Additionally, a Multiple Linear Regression Analysis (IBM SPSS Statistics 20) for sex and age, as well as a Pearson's Correlation analysis for pre-vaccine anti- SARS-CoV-2 IgG levels were performed to explore potential confounding variables.

3. Role of funding source

This work did not receive any financial support.

4. Results

66 HCWs were tested for IgG levels at baseline, before vaccination. Of these, three participants were excluded; one, due to treatment with methotrexate and corticosteroids for autoimmune disease, and the other due to rituximab treatment for lymphoma. A third participant was excluded for presenting symptomatic COVID-19 (PCR positive) in the first week after the first dose of the vaccine.

Demographic characteristics of the 63 remaining participants are summarized in Table 1. 33 HCWs had previous COVID-19, 32 of them between March and April 2020, and the remaining one in September 2020. Five were asymptomatic, 22 had mild symptoms and another six experienced pneumonia, of which only one of them required oxygen therapy and hospitalization. The median time elapsed between COVID-19 diagnosis and the date of the first vaccine dose was 303 days (range 131-338): all but one of the individuals in the COVID-19 experienced group received their first dose of the vaccine ten months after diagnosis (Table 1). HCWs with prior COVID-19 were older than HCWs without prior infection. The distribution by sex was similar in the two groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the participants in the study.

| Experienced-Covid-19 | Naive-Covid-19 | Univariate test *** | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 33 | 30 | |

| Age in years (Mean ± SD*;Range**) | 50.1±12.6 (25-67) | 41.2±15.2 (25-63) | p = 0,019 |

| Gender [number of females (% of females)] | 21 (67%) | 21 (70%) | p = 0.79 |

| Days between 1st and 2nd dose (Mean ± SD*; Range**) | 23.3 ± 3.7 (21-28) | 22.4 ± 1.2 (21-27) | p = 0.21 |

| Days between Covid-19 diagnosis and vaccine (Median; Range) | 303 (131-338) | N/A |

*SD: Standard Desviation.

** Range: lowest and highest values.

*** Student t test, Chi-Squared test.

N/A: not applicable.

The results of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies measurements are represented in Fig. 1. Out of 33 HCWs with previous COVID-19, 29 (88%) had positive (>50 AU) anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibody levels at baseline (GMC=311 AU; 95% CI: 144-479). Seven days after receiving their first vaccine dose, all of them, including the four seronegative HCWs, experienced a 126-fold increase in antibody levels (GMC 26955 AU; 95% CI 18785-35125; p <0·0001). At day 14 post-vaccination, they showed a small, non-significant increase in the anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibody titer (GMC 40701 AU; 95%, CI 34161-47241; p = 0·086), with no increase observed on day 21. A positive correlation was found in the experienced HCWs between their baseline anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibody levels and their antibody levels following vaccination, particularly two weeks after the the first dose of the vaccine (Pearson's Correlation Coefficient = 0.518, p=0.004, see S1, supplementary material). Regarding the HCW “naïve” group, all of them were seronegative in the days prior to vaccination. Seven days following the administration of the first dose of the vaccine, only five of the naïve HCWs showed positive IgG values (> 50 AU). At day 14, all of them presented detectable antibody values, although the values reached were still modest (GMC 774 AU; CI: 416-1132; p<0·001). Their levels continued to increase (1·6-fold) until day 21 (GMC 1233 AU; 95% CI 865-1602; p =0·018).

Fig. 1.

Immunogenicity of the BNT162b2 vaccine. SARS-CoV-2 (IgG II Quant, Abbott) peak antibody titers from 63 individuals. The moment of administration of the two doses is marked with a triangle and the sampling times are counted from each one of them. The time elapsed between the two vaccine administrations ranged between 21 and 28 days. Some of the individuals with pre-existing immunity had antibody titers below detection level (21 AU) or below the level established by the manufacturer (50 AU) in the days prior to vaccination.

* The IgG values from these four individuals (orange circles) were only taken into account to analyze the effects of the first dose of the vaccine.

With regard to the second vaccine administration, there were no significant changes in antibody levels in the experienced HCW group (Fig. 1). However, in the group without previous infection another increment was observed seven days following the second dose: a 16-fold increase in the antibody titer (GMC 20227 AU; 95% CI: 2576-25275; p<0·001), reflecting a classic secondary response. Also in this group, the antibody titers remained stable until day 14 post-vaccination (GMC 20751 AU; 95% CI 16641-24861; NS), but decreased when measured on day 21 post-vaccination (GMC=15408 AU; 95% CI 118016-19001; p=0·036). The antibody titers of HCWs with pre-existing immunity were higher than those in the naïve HCWs at all time points following doses (p<0·01). The greatest difference was found on day 7 days after the first dose (2300 fold), and it was gradually reduced to a factor of up to 2 fold by days 14 to 21 following the second dose (Fig. 1)

Multiple Linear Regression Analysis showed no significant differences in antibody levels regarding sex or age at the different time-points of sample extraction (see S2 supplementary material). Neither were there any differences within the group of patients with previous infection between the HCWs who were seropositive before the vaccine and the HCWs who were already negative.

Four HCWs with previous COVID-19 did not receive the second dose of the vaccine; however, they maintained anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibody levels similar to HCWs who were treated with two doses. The data of these 4 HCWs are represented in Fig. 1, in another color and slightly shifted to the left. These four experienced HCWs were not included in the statistical analysis of the effects of the second dose compared with the first dose.

Approximately two months (median 66 days; interval 57-86) after the second dose of the vaccine, new samples were taken for antibody determination, with a notable decrease in titers observed in all cases (Fig. 1). The level of antibodies was much lower in patients without previous infection compared with experienced HCWs (GMC 6595 AU vs 25003 AU; p<0·001). In addition, we calculated the percentage of antibody level decrease for each HCW individual in relation to their highest titer, finding that the decrease was more pronounced in the HCW naïve group than in the HCW group with previous infection (average 76·46% vs 56%; p<0·0001).

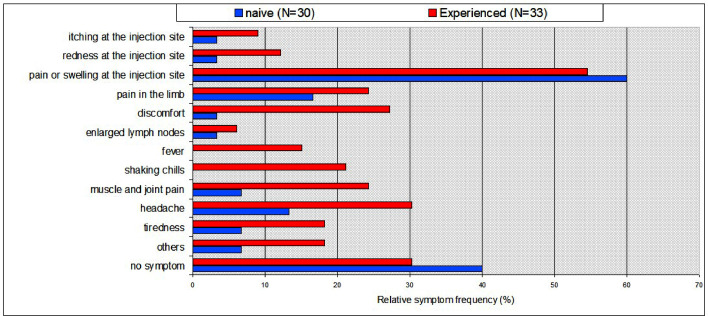

We also compared the frequency of adverse reactions following the first and second vaccine doses in both groups (Fig. 2). The HCWs with previous COVID-19 showed more side effects after the first vaccine administration than the naïve group. However, after the second dose of the vaccine there were no significant differences between the COVID-19 –experienced and naïve groups. The vaccine was generally well tolerated and medical attention was not required for any of the participants.

Fig. 2.

Vaccine-associated side effects experienced after the first dose (N = 66 individuals). Side effects occurred more frequently in people with pre-existing immunity, particularly systemic symptoms. Fever or chills were not observed among patients without pre-existing immunity.

Univariate analysis for individual variables only revealed significant differences for “disconfort" and "shaking chills" (Fisher Exact Test two tailed p<0.05). Chi-Squared test (2 x N) analysis showed an overall significant difference in reactivity to vaccination between the experienced HCW and naïve HCW groups (p<0.001)

6. Discussion

Our study provides evidence for an early, stronger and more durable immune response in COVID-19 experienced HCWs vs naïve HCWs following vaccination with the BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine. An early and strong response of a similar order of magnitude has been described after the first dose of the vaccine in previous studies in experienced individuals [3,[5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14]]. It is important to note that this early and strong response was also shown by experienced HCWs who were negative for anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies prior to receiving the first dose of the BNT162b2 vaccine. As in previous studies [3,[10], [11], [12], [13], [14]], we found that the second dose of the vaccine did not increase anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibody levels in experienced individuals, contrasting with the marked antibody increase still shown by naïve individuals. Therefore, a single dose may be sufficient for experienced individuals to achieve antibody levels equal to or higher than those obtained by the complete vaccination schedule in individuals without previous infection.

The anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibody levels two months after the end of the vaccination protocol were higher in experienced HCWs vs naïve HCWs. Moreover, the decline in antibody levels with respect to peak level was nearly two fold more pronounced in the naïve HCW group. These findings should affect the regimen of administration for potential further doses of the vaccine.

One limitation of this study is employing an assay that detects total IgG type antibodies against the S1 subunit of the SARS-CoV2 virus spike protein as a surrogate marker of the immune response, versus measuring neutralizing antibodies specifically. Nevertheless, several experiments have shown high levels of correlation between assessment of the anti-RBD binding antibodies used in this study and neutralizing antibodies [7,15]. Another limitation of the current study was that we were not equipped to evaluate the cellular immune response. However, a correlation between humoral and cellular immunity after vaccination has been recently shown by other authors [11]. Other limitations were the following: single centre study, which may limit generalisation of findings, short follow up time, small sample size, none of the participants were older than 67 nor belonged to racial or ethnic minorities. However, previous single center studies using small sample sizes and short follow-up time showed similar results in antibody levels after a first dose of the vaccine. 6–11 So far, a role for ethnicity in antibody response to COVID-19 vaccination has not been observed [16]. However, lower immune response to the BNT162b2 vaccine has been shown in older people [16]. Waning antibody levels were demonstrated in this and other recent studies employing anti-SARS-CoV-2 vaccines [17,18]. Longer term data collection is necessary to properly assess this phenomenon. We are currently gathering data at regular intervals from individuals up to one year post- vaccination.

In conclusion, our study shows that at least ten months following infection from SARS-CoV2, the immune system is still capable of producing a rapid and powerful secondary antibody response after one single dose of the vaccine. Additionally, we found no further improvement in antibody response to the second dose in individuals with previous COVID-19 infection. Nonetheless, two months later, anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibody levels were still higher in the experienced HCWs. These data suggest that immune memory persists over a long time in recovered individuals; therefore, the second dose of the COVID-19 vaccine in this group could be postponed until immunization of the remaining population is complete. With the emergence of new SARS-CoV-2 variants, further research will be necessary to optimize both the characteristics of the vaccines and vaccination schedules [13,19].

Contributors

Conceptualization: JO, JS, JB, Formal analysis: JO, JS, JB, Investigation: JO, JS, JB, CdC, CS, ER-E, AG, LM, LS, JLB, LN, CSdB, Verification of the underlying data: JO, JS, Writing – original draft preparation: CdC, JO, JS, Writing – review and editing: CdC, JO, JS, JB, LM, RR, LS, CS Supervision: JO, CdC, JS

Funding

This work did not receive any financial support.

Data sharing

The metadata will be available through the - RUIdeRA Repositorio Institucional of the University of Castilla- La Mancha (Data repository from Castilla - La Mancha University) and will be available for secondary analysis once the study has been published.

Declaration of Competing Interest

We declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the health care workers who participated in the study. The authors also wish to thank the CEO and the Board of Directors of the Albacete General Hospital for their continued support and Alexandra L. Salewski MSc. for expert English review of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.ebiom.2021.103656.

Contributor Information

Carlos de Cabo, Email: carlosd@sescam.jccm.es.

Javier Solera, Email: solera53@gmail.com.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Polack FP, Thomas SJ, Kitchin N. Safety and Efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 Vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2439–2450. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2034577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hall VJ, Foulkes S, Charlett A. SARS-CoV-2 infection rates of antibody-positive compared with antibody-negative health-care workers in England: a large, multicentre, prospective cohort study (SIREN) Lancet. 2021;397:1459–1469. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00675-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.AbuRaddad LJ, Chemaitelly H, Malek JA. Assessment of the risk of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) reinfection in an intense reexposure setting. Clin Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1846. ciaa1846. Corrected proof. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lumley SF, O'Donnell D, Stoesser NE. Oxford university hospitals staff testing group. antibody status and incidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in health care workers. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:533–540. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2034545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Perkmann T, PerkmannNagele N, Koller T. Anti-spike protein assays to determine SARS-CoV-2 antibody levels: a head-to-head comparison of five quantitative assays. Microbiol Spectr. 2021;9 doi: 10.1128/spectrum.00247-21. e00247-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prendecki M, Clarke C, Brown J. Effect of previous SARS-CoV-2 infection on humoral and T-cell responses to single-dose BNT162b2 vaccine. Lancet. 2021;397:1178–1181. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00502-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saadat S, RikhtegaranTehrani Z, Logue J. Binding and neutralization antibody titers after a single vaccine dose in health care workers previously infected with SARS-CoV-2. JAMA. 2021;325:1467–1469. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.3341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bradley T, Grundberg E, Selvarangan R. Antibody responses after a single dose of SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:1959–1961. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2102051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Manisty C, Otter AD, Treibel TA. Antibody response to first BNT162b2 dose inpreviously SARS-CoV-2- infected individuals. Lancet. 2021;397:1057–1058. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00501-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krammer F, Srivastava K, Alshammary H. Antibody responses in seropositive persons after a single dose of SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine. New Engl J Med. 2021;384:1372–1374. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2101667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.LozanoOjalvo D, Camara C, LopezGranados E. Differential effects of the second SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine dose on T cell immunity in naive and COVID-19 recovered individuals. Cell Reports. 2021;36 doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2021.109570. 109570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fraley E, LeMaster C, Geanes E. Humoral immune responses during SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine administration in seropositive and seronegative individuals. BMC Med. 2021;19 doi: 10.1186/s12916-021-02055-9. 169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stamatatos L, Czartoski J, Wan YH. mRNA vaccination boosts cross-variant neutralizing antibodies elicited by SARS-CoV-2 infection. Science. 2021 doi: 10.1126/science.abg9175. eabg9175. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Velasco M, Galán MI, Casas ML, Pérez-Fernández E, Martínez-Ponce D, González-Piñeiro B, Castilla V, Guijarro C. Alcorcón COVID-19 working group. Impact of previous coronavirus disease 2019 on immune response after a single dose of BNT162b2 severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 vaccine. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2021;8 doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofab299. ofab299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dan JM, Mateus J., Kato Y. Immunological memory to SARS-CoV-2 assessed for up to 8 months after infection. Science. 2021;371 doi: 10.1126/science.abf4063. eabf4063Epub 2021 Jan 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.AbuJabal K, BenAmram H, Beiruti K. Impact of age, ethnicity, sex and prior infection status on immunogenicity following a single dose of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine: real-world evidence from healthcare workers, Israel. Euro Surveill. 2021;26 doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2021.26.6.2100096. pii=2100096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.DoriaRose N, Suthar MS, Makowski M. Antibody persistence through 6 months after the second dose of mRNA-1273 vaccine for Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:2259–2261. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2103916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khoury DS, Cromer D, Reynaldi A. Neutralizing antibody levels are highly predictive of immune protection from symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat Med. 2021;27:1205–1211. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01377-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Urbanowicz RA, Tsoleridis T, Jackson HJ. Two doses of the SARS-CoV-2 BNT162b2 vaccine enhance antibody responses to variants in individuals with prior SARS-CoV-2 infection. Sci Transl Med. 2021 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abj0847. eabj0847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.