Highlights

-

•

Social prescribing is an important part of the United Kingdom’s national healthcare strategy, and this is the first evidence review on social prescribing for migrants in the UK.

-

•

Improved self-esteem, confidence, empowerment, and social connectivity were frequently reported outcomes.

-

•

Link workers frequently took on additional support roles and/or actively delivered prescribed activities themselves.

-

•

Despite low quality evidence, it is clear that migrants’ specific health and wellbeing needs, including the wider determinants of health, require social prescribing services to be adapted. Services should be tailored as much as possible to migrants’ preferences for language, culture, gender and service delivery format.

-

•

Robust evaluation should be embedded into the planning and commissioning of social prescribing programmes in future. Better recording of sociodemographic characteristics (e.g. indicators of migration like country of birth and migrant typology) will enable a richer understanding of how social prescribing works and for whom.

Keywords: Social prescribing, Migrant, Refugee, Asylum seeker, Link worker, Navigation, Health, Wellbeing

Abstract

Background

The health needs of international migrants living in the United Kingdom (UK) extend beyond mainstream healthcare to services that address the wider determinants of health and wellbeing. Social prescribing, which links individuals to these wider services, is a key component of the UK National Health Service (NHS) strategy, yet little is known about social prescribing approaches and outcomes for international migrants. This review describes the evidence base on social prescribing for migrants in the UK.

Methods

A systematic review was undertaken, which identified studies through a systematic search of 4 databases and 8 grey literature sources (January 2000 to June 2020) and a call for evidence on the UK government website (July to October 2020). Published and unpublished studies of evaluated social prescribing programmes in the UK were included where at least 1 participant was identified as a migrant. Screening, data extraction and quality appraisal were performed by one reviewer, with a second reviewer checking 20% of studies. A narrative synthesis was conducted.

Findings

Of the 4544 records identified, 32 were included in this review. The overall body of evidence was low in quality. Social prescribing approaches for migrants in the UK varied widely between programmes. Link workers who delivered services to migrants often took on additional support roles and/or actively delivered parts of the prescribed activities themselves, which is outside of the scope of the typical link worker role. Evidence for improvements to health and wellbeing and changes in healthcare utilisation were largely anecdotal and lacked measures of effect. Improved self-esteem, confidence, empowerment and social connectivity were frequently described. Facilitators of successful implementation included provider responsiveness to migrants’ preferences in relation to language, culture, gender and service delivery format. Barriers included limited funding and provider capability.

Conclusions

Social prescribing programmes should be tailored to the individual needs of migrants. Link workers also require appropriate training on how to support migrants to address the wider determinants of health. Robust evaluation built into future social prescribing programmes for migrants should include better data collection on participant demographics and measurement of outcomes using validated and culturally and linguistically appropriate tools. Future research is needed to explore reasons for link workers taking on additional responsibilities when providing services to migrants, and whether migrants’ needs are better addressed through a single-function link worker role or transdisciplinary support roles.

1. Introduction

Social prescribing is an important part of National Health Service (NHS) strategy in the United Kingdom (UK). The NHS Long Term Plan and Universal Personalised Care envisioned a shift towards individuals having more choice and control over their own health (National Health Service 2019, NHS England and NHS Improvement 2019). Social prescribing is defined by the NHS as a method by which referrals from healthcare professionals, statutory services, voluntary services as well as self-referrals are made to link workers, who in turn connect individuals with community, voluntary, statutory and other sector services to improve holistic health and wellbeing (NHS England 2021). The prescribed activities to which link workers refer individuals are often non-clinical in nature, and may include physical activity groups, arts and crafts, befriending, education and training, volunteering opportunities, and health-related therapies (Booth et al., 2015). Despite the increasing acceptance of social prescribing as a model of care in the UK, the evidence for its effectiveness in the general UK population is sparse and of low methodological quality (Bickerdike et al., 2017, Public Health England 2019).

Approaches to and effectiveness of social prescribing are likely to vary across different populations (Husk et al., 2019). There is political intent in regions like London to improve access to social prescribing schemes for underserved populations such as international migrants (London Assembly). Migrants can experience challenges accessing mainstream medical and healthcare services due to a multitude of barriers like language and lack of knowledge about the healthcare system (Agudelo-Suárez et al., 2012, Kang et al., 2019, O'Donnell et al., 2007). This can affect those who have relocated to the UK voluntarily or involuntarily, and whose immigration status is documented or undocumented. Depending on migrant typology, immigration status and origin, migrants can have different patterns of exposure to health risks and physical and mental health outcomes compared to the general population (Abubakar et al., 2018). In addition to being at greater risk of social exclusion and marginalisation, migrants in the UK without permanent residency (indefinite leave to remain) across a broad range of immigration status categories cannot access welfare benefits and housing assistance (NRPF Network 2021). For these reasons, social prescribing's holistic approach to addressing individuals’ needs may be effective at improving migrants’ health and wellbeing, and is likely to encompass a greater range of activities than for the general population. This could include support to access services like mainstream healthcare, immigration advice, interpreting and bilingual advocacy, and other support to address the wider determinants of health (Allen et al., 2018)

To date, no evidence review has focused on social prescribing for migrants in the UK. The limiting of previous reviews to social prescribing referrals from primary care (Bickerdike et al., 2017; Public Health England 2019) is also unlikely to capture migrants who have difficulties accessing mainstream healthcare services. This review aims to describe the evidence base for social prescribing for migrants in the UK. It specifically examines the approaches that have been evaluated for migrants, their effects on migrants, and the experiences of implementation from the perspectives of migrants, providers and referrers to social prescribing programmes.

2. Methods

A systematic review was undertaken, which incorporated a call for evidence.

2.1. Data sources & search strategy

A three-stage process was undertaken to source evidence.

First, a systematic search of published literature (PROSPERO protocol CRD42020187937) was conducted on 2 June 2020 in four electronic databases: Embase, PsycINFO, Web of Science, and Social Policy & Practice. Search strategies are detailed in Appendix A. Text-word search combinations of social prescribing and migrant terms in the search strategy (e.g. “social prescribing” migrants, “exercise referral” refugee) were conducted to identify grey literature from eight sources: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Journal Library, Google, Trip Medical database, Nesta, Nuffield Trust, King's Fund and Health Foundation. The first 100 results from each grey literature source were screened.

Second, a call for evidence was initiated on the UK government website from 1 July to 30 October 2020 (Appendix A) in response to the low number of eligible studies from systematic searches and the possibility of unpublished evidence (Public Health England 2020).

Third, the reference lists of systematic reviews and seminal studies from the systematic search and call for evidence were manually searched.

2.2. Eligibility criteria

Eligible study types included published and unpublished controlled and uncontrolled experimental study designs, observational studies, grey literature (e.g. evaluation reports, other programme/intervention-related reports with measurable outcomes, case reports and consultation summaries). Studies published (or conducted, in the case of unpublished literature) from 1 January 2000 were eligible.

Studies were included if they evaluated social prescribing programmes in the UK delivered to migrants through any approach such as referral, self-referral or signposting to a link worker, who in turn prescribes (i.e. refers or signposts to) activities (NHS England 2020). Studies were excluded if they only provided a description of the social prescribing programme with no evaluation of intervention effects or implementation. The criterion for population of interest was international migrants as defined by the International Organization of Migration (International Organization for Migration, Glossary on Migration 2019). Items were included if at least 1 migrant was identified within the study/report cohort.

2.3. Screening and data extraction

Studies that satisfied the inclusion criteria were divided across reviewers (systematic search: FW, CZ; call for evidence: CZ, AB). Each study underwent title and abstract screening and full text screening by one reviewer. A random 20% sample of studies underwent title, abstract and full text screening by a second reviewer (Garritty et al., 2020). Discrepancies were resolved between reviewers and agreements were reflected in the final selection.

Data extraction also involved one reviewer, with a second reviewer double-extracting 20% of studies. Extraction followed the Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcomes, Study design (PICOS) framework using a form created by the reviewers, which was piloted on 5 studies and subsequently adapted. Data were extracted on publication details, study aims, methods, participant demographics, social prescribing approaches (referral initiators, method of entry into the programme, providers, duration, location), prescribed activities, intervention effect and intervention implementation.

In studies that reported outcomes for migrants and non-migrants, data were extracted for only migrant participants where possible. Studies that described different activities or outcomes from the same social prescribing programme in the same or overlapping time period underwent data extraction and quality appraisal as one unit.

2.4. Quality appraisal

Qualitative studies and programme evaluations were assessed for quality and risk of bias by one reviewer using the NICE Quality Appraisal Checklists for qualitative and quantitative intervention studies (NICE, 2012a,NICE, 2012b). Mixed methods programme evaluations were appraised using both qualitative and quantitative intervention checklists. The NICE qualitative checklist was also used to appraise stakeholder consultation event summaries received as submissions to the call for evidence. The Joanna Briggs Institute Checklist for Case Reports (Moola et al., 2017) was used to appraise case reports. Quality of individual studies were presented in the form of ratings in Appendix B, and the overall quality of the evidence was summarised in narrative form.

2.5. Outcome measures

Outcomes of interest were social prescribing approaches, effects and implementation.

Intervention effect outcomes were consistent with those used in past reviews of social prescribing for the general population (Bickerdike et al., 2017; Public Health England 2019). These included any provider- or self-reported measures of the impact of social prescribing on:

-

•

physical and mental health and wellbeing, including pre/post changes in scores on validated physical and/or mental health and wellbeing tools

-

•

healthcare utilisation, including frequency of contact with primary health care services such as general practitioner (GP) consultations.

Additional intervention effect outcomes included those defined by Allen and colleagues (Allen et al., 2018) relevant to the migrant context:

-

•

self-esteem, confidence, control and empowerment

-

•

knowledge and skills

-

•

social connectivity

Intervention implementation outcomes included the experiences of the recipients of social prescribing services, the providers of these services, and those referring individuals to these services.

2.6. Synthesis

A narrative synthesis of included studies was completed by 3 reviewers (CZ, AB, SH) to describe the findings in terms of the types of social prescribing approaches, their effects and implementation. Due to the minimal reporting of effect sizes, no meta-analysis was conducted.

3. Results

3.1. Study selection

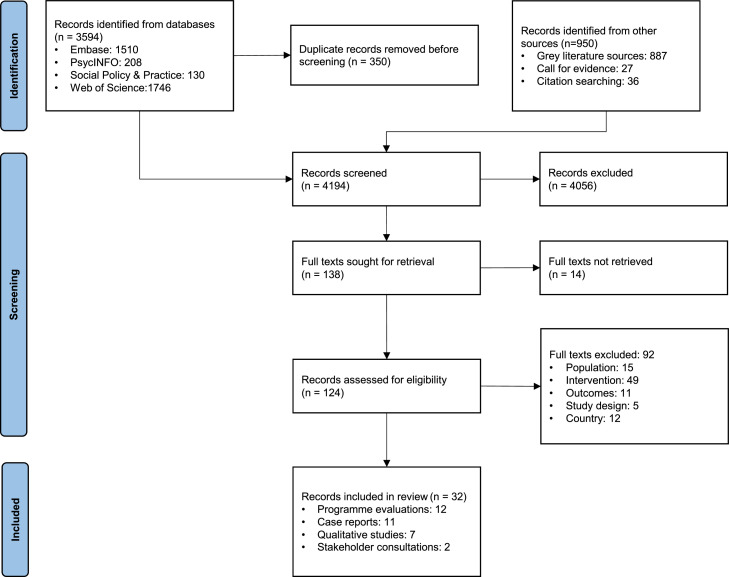

Of the 4544 records identified, 350 were identified as duplicates and removed. 4194 underwent title and abstract screening, 138 full text screening, and 32 were included in the review (Fig. 1). The vast majority of the 4056 studies that were excluded during title and abstract screening described interventions that did not meet our definition of social prescribing, did not undertake any evaluation for migrants, and/or were conducted outside of the UK.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

3.2. Study characteristics

Of the 32 included studies, programme evaluations were most common (12, 38%), followed by case reports (11, 34%), qualitative studies (7, 22%) and stakeholder consultation event summaries (2, 6%). Almost all (30, 94%) were conducted in England with 13 (41%) in London. Three (9%) were conducted in Glasgow, Scotland.

Sixteen studies (50%) sampled migrants only, and the most frequently mentioned migrant typologies were asylum seekers and refugees (14, 44%). Other migrant typologies identified were migrant workers, international students, individuals with undocumented migrant status, survivors of human trafficking and survivors of torture. The number of migrants in included studies ranged from 1 to 498, but almost half of included studies (14, 44%) involved less than 20 migrants. The characteristics of each study are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies.

| Study type | Location (author, year) | Population | Entry into social prescribing programme | Link worker role |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Programme evaluation | London (Tran, 2009) |

|

|

Link, prescribed activity, bilingual advocate |

| London (Islam, 2019) |

|

|

Link | |

| Sheffield (Voluntary Action Sheffield, 2018) |

|

|

Link | |

| London (Longwill, 2014) |

|

|

Link and prescribed activity | |

| London (Gray, 2002) |

|

|

Link and prescribed activity | |

| Croydon, Derby, Leeds, Nottingham & Redbridge (Gallagher and Featonby, 2019) |

|

|

Link, prescribed activity, casework | |

| Sussex (Sussex Interpreting Services 2017) |

|

|

Link, prescribed activity, volunteer linguist | |

| Sussex (Sussex Interpreting Services 2018b) |

|

|

Link, prescribed activity, volunteer linguist | |

| Sussex (Sussex Interpreting Services 2019) |

|

|

Link, prescribed activity, volunteer linguist | |

| Glasgow (NHS, Scotland 2014) |

|

|

Link and prescribed activity | |

| London (Cant and Taket, 2005) |

|

|

Link, prescribed activity, advocate, befriender | |

| Newcastle-upon-Tyne (Askins, 2014) |

|

|

Link, prescribed activity, befriender | |

| Case report | London (RedbridgeCVS, 2018) |

|

|

Link |

| Sussex (Sussex Interpreting Services 2018a) |

|

|

Link, prescribed activity, volunteer linguist | |

| Sussex (Rowe et al., 2020, Trust for Developing Communities 2020a, Sussex Interpreting Services 2020) |

|

|

Link, prescribed activity, volunteer linguist | |

| Sussex (Voices in Exile 2020, Trust for Developing Communities, 2020b) |

|

|

Link, prescribed activity, volunteer linguist | |

| Bradford (Dayson and Leather, 2020) |

|

|

Link | |

| Midlands, Sheffield, Glasgow, Rushmoor, Cornwall & London (The British Academy 2017) |

|

|

Link and prescribed activities | |

| St Helens (St Helens Council 2018) |

|

|

Link | |

| South Yorkshire (South Yorkshire Housing Association 2020) |

|

|

Link and prescribed activities | |

| Qualitative study | London, West of England & North of England (McLeish and Redshaw, 2015, McLeish and Redshaw, 2017, McLeish and Redshaw, 2017) |

|

|

Link, prescribed activity, peer support/mentor |

| London (McLeish and Redshaw, 2016) |

|

|

Link, prescribed activity, peer support/mentor | |

| London (Healthwatch Islington 2019) |

|

|

Link and prescribed activities | |

| North East England (Parks, 2015) |

|

|

Link, prescribed activity, children's centre staff | |

| Glasgow (Wren, 2007) |

|

|

Link and prescribed activities | |

| Stakeholder consultation event summary | London (Greater London Authority et al., 2020) |

|

|

Link and prescribed activities |

| Nottingham (Kellezi et al., 2020) |

|

|

Link and prescribed activities | |

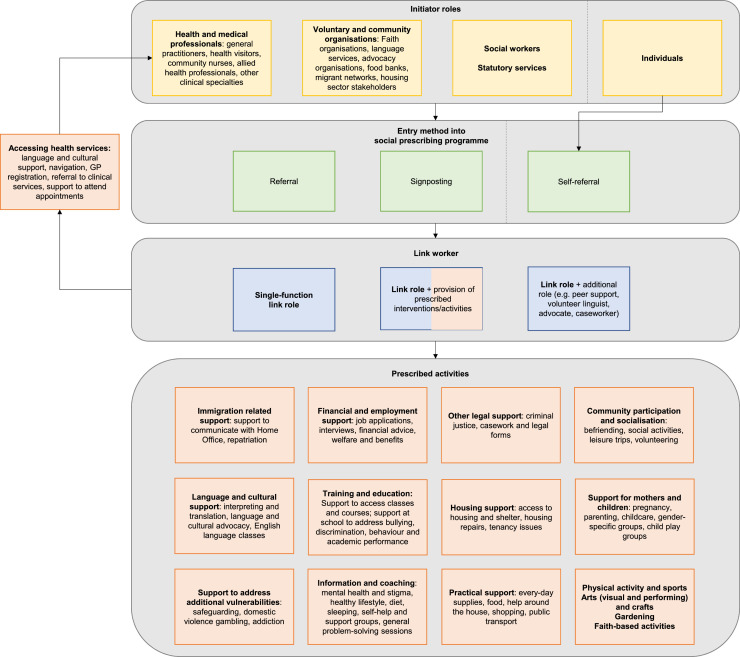

3.3. Social prescribing approaches

Social prescribing approaches are visually represented in Fig. 2, and the frequency of studies describing different types of approaches and outcomes are detailed in Table 2. Over 90% of studies described the mode of entry into a social prescribing programme via a referral. Other modes included signposting and self-referral (via a variety of methods including social media). Those initiating referrals or signposting to a social prescribing programme were stakeholders from health and social care, local authorities or voluntary and community organisations (described as ‘initiator roles’ in Fig. 2). In 84% of studies, link workers played the dual role of linking migrants to prescribed activities and delivering them. Some approaches that fell under the definition of social prescribing were undertaken as part of broader programmes that combined a link worker role with other roles like peer support, advocate, volunteer linguist and children's centre staff. Mechanisms by which individuals were linked to a prescribed activity were not well described, and few studies differentiated between referral and signposting mechanisms. Prescribed activities varied widely between studies.

Fig. 2.

Social prescribing approaches for migrant populations.

Table 2.

Frequency of studies reporting various social prescribing approaches and outcomes.

| Number of studies (%)* | |

|---|---|

| Social prescribing approaches | |

| Method of entryReferralSignpostingSelf-referral | 29 (91%)6 (19%)12 (38%) |

| Link worker roleSingle-function link roleLink and provision of prescribed activitiesLink and additional role (e.g. peer support, caseworker) | 5 (16%)27 (84%)18 (56%) |

| Social prescribing outcomes | |

| Intervention effectsPhysical health and wellbeingMental health and wellbeingHealthcare utilisationSelf-esteem, confidence and empowermentKnowledge and skillsSocial connectivity | 7 (22%)17 (53%)10 (31%)24 (75%)8 (25%)24 (75%) |

| Intervention implementationProviders of social prescribing servicesReferrers to social prescribing servicesIndividuals receiving services | 23 (72%)6 (19%)17 (53%) |

Not mutually exclusive counts and percentages.

3.4. Intervention effects

Social prescribing effects of interest were quantitative or qualitative measures of changes in physical and mental health and wellbeing; healthcare utilisation; self-esteem, confidence and empowerment; knowledge and skills; and social connectivity. Since most studies were of low quality (Section 3.6) and outcomes were rarely reported in relation to a specific prescribed activity, the evidence has been presented as a high-level summary with further details where validated measures were used.

3.4.1. Physical and mental health and wellbeing

In two out of three studies that used validated tools to measure health and wellbeing outcomes, effects were associated with a broad range of prescribed activities involving migrants and non-migrants rather than specific activities concerning only migrants. The Measure Yourself Concerns and Wellbeing (MYCaW) tool was used to demonstrate a clinically significant improvement in general wellbeing (Islam, 2019). The General Anxiety Disorder (GAD7) was also used to demonstrate statistically significant reduction in anxiety (2.5-point difference, p<0.001), alongside the Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluation 10 (CORE-10) to show statistically significant reduction in anxiety, panic and suicidal ideation (p<0.001) (Longwill, 2014). One study involved only migrants, and used the Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale (WEMWBS) to show that the majority (72.2%) of survivors of human trafficking had an increase in overall mental wellbeing score at the end of a wider programme of interventions (including social prescribing), while a smaller proportion demonstrated a decrease (25.2%) or no change (2.8%) in score (Gallagher and Featonby, 2019).

Other improvements to mental wellbeing (Gray, 2002, South Yorkshire Housing Association 2020) and reductions in mental health concerns (Tran, 2009, Voluntary Action Sheffield, 2018, Longwill, 2014, RedbridgeCVS, 2018, Sussex Interpreting Services 2018, Rowe et al., 2020, Trust for Developing Communities 2020a, Sussex Interpreting Services 2020, Dayson and Leather, 2020, McLeish and Redshaw, 2015, McLeish and Redshaw, 2017, McLeish and Redshaw, 2017), physical health symptoms (Longwill, 2014, Rowe et al., 2020, Trust for Developing Communities 2020a, Sussex Interpreting Services 2020), and likelihood of children experiencing neglect or significant harm (Gray, 2002) were reported anecdotally and lacked measures of effect, or were measured using an unvalidated tool (St Helens Council 2018).

3.4.2. Healthcare utilisation

No studies quantitively measured changes to healthcare utilisation. Anecdotal reports concerning frequency of healthcare use included reductions in ‘unnecessary’ or ‘inappropriate’ GP consultations (Islam, 2019, Longwill, 2014) and mental health services (Longwill, 2014, Sussex Interpreting Services 2018a). Improved access to healthcare services were also anecdotally reported through support with language, culture, system navigation, service registration and appointment attendance (Tran, 2009, Gray, 2002, Gallagher and Featonby, 2019, Sussex Interpreting Services 2017, McLeish and Redshaw, 2015, McLeish and Redshaw, 2017, McLeish and Redshaw, 2017). Improved compliance with healthcare recommendations (Tran, 2009), involvement in healthcare related decisions and assertion of health needs to healthcare service providers (Longwill, 2014) were also described.

3.4.3. Self-esteem, confidence and empowerment

Improvements in general confidence, self-esteem and empowerment were reported anecdotally and qualitatively across sixteen studies (Islam, 2019, Longwill, 2014, Gray, 2002, Gallagher and Featonby, 2019, Rowe et al., 2020, Trust for Developing Communities, 2020a, Sussex Interpreting Services 2020, Voices in Exile 2020, Trust for Developing Communities, 2020b, St Helens Council 2018, South Yorkshire Housing Association 2020, McLeish and Redshaw, 2015, McLeish and Redshaw, 2017, McLeish and Redshaw, 2017, McLeish and Redshaw, 2016, Healthwatch Islington 2019), though effect sizes were not measured, and few quantified proportions of individuals affected. This included confidence to express feelings and disclose personal information (Voluntary Action Sheffield, 2018, NHS Scotland 2014, RedbridgeCVS, 2018, The British Academy 2017, McLeish and Redshaw, 2016), as well as increased independence, control and stability across the domains of employment and finances (Islam, 2019, Voluntary Action Sheffield, 2018, Sussex Interpreting Services 2019, Sussex Interpreting Services 2018a, Voices in Exile 2020, Trust for Developing Communities, 2020b, Healthwatch Islington 2019), parenting (Gray, 2002), decision-making (Longwill, 2014, McLeish and Redshaw, 2016) and using services within the community (Sussex Interpreting Services 2018b, Sussex Interpreting Services 2018a). Looking to the future was also described, with individuals feeling a sense of purpose (Voluntary Action Sheffield, 2018, Sussex Interpreting Services 2018a, McLeish and Redshaw, 2016) and hope (Islam, 2019, Dayson and Leather, 2020, McLeish and Redshaw, 2016).

3.4.4. Knowledge and skills

Knowledge and skills were discussed mostly in the context of proportions of individuals who were supported to access language and literacy classes (Sussex Interpreting Services 2018a, Voices in Exile 2020, Trust for Developing Communities, 2020b, The British Academy 2017, Parks, 2015), formal education and schooling (Longwill, 2014, Gallagher and Featonby, 2019, The British Academy 2017), and occupational skill development (Longwill, 2014, Gallagher and Featonby, 2019, Voices in Exile 2020, Trust for Developing Communities, 2020b). No studies measured improvements to knowledge and skill.

3.4.5. Social connectivity

Relationships, engagement with the community and social dynamics were discussed across the majority of studies through qualitative findings or brief anecdotal reports. New friendships were created (Voluntary Action Sheffield, 2018, Longwill, 2014, NHS Scotland 2014, Voices in Exile 2020, Trust for Developing Communities, 2020b, Dayson and Leather, 2020, Healthwatch Islington 2019, Wren, 2007) and existing relationships were strengthened with family and friends (Longwill, 2014, Gray, 2002). Around half of the studies also reported increased social networks within the community (Islam, 2019, Gray, 2002, Gallagher and Featonby, 2019, Cant and Taket, 2005, RedbridgeCVS, 2018, Voices in Exile 2020, Trust for Developing Communities, 2020b, Dayson and Leather, 2020, The British Academy 2017, McLeish and Redshaw, 2015, McLeish and Redshaw, 2017, McLeish and Redshaw, 2017, Parks, 2015) and improved participation in community activities (Voluntary Action Sheffield, 2018, Longwill, 2014, Gray, 2002, NHS Scotland 2014, St Helens Council 2018, South Yorkshire Housing Association 2020, McLeish and Redshaw, 2015, McLeish and Redshaw, 2017, McLeish and Redshaw, 2017). Inter- and intra-cultural connections were created (Voluntary Action Sheffield, 2018, Wren, 2007). There were mixed findings about the added social pressure from increased social connections (Gallagher and Featonby, 2019, McLeish and Redshaw, 2015, McLeish and Redshaw, 2017, McLeish and Redshaw, 2017). Connectedness through supporting others or receiving support was also a common theme (Longwill, 2014, Gray, 2002, Gallagher and Featonby, 2019, Sussex Interpreting Services 2018a, Dayson and Leather, 2020, McLeish and Redshaw, 2015, McLeish and Redshaw, 2017, McLeish and Redshaw, 2017). A third of studies also reported reduced loneliness and/or social isolation (Cant and Taket, 2005, Sussex Interpreting Services 2018a, Rowe et al., 2020, Trust for Developing Communities, 2020a, Sussex Interpreting Services 2020, The British Academy 2017, McLeish and Redshaw, 2015, McLeish and Redshaw, 2017, McLeish and Redshaw, 2017, Healthwatch Islington 2019).

3.5. Intervention implementation

Social prescribing implementation was examined from the perspectives of individuals receiving, providing and referring to social prescribing services. Overall, satisfaction with social prescribing services was expressed by all three parties (Tran, 2009, Islam, 2019, Voluntary Action Sheffield, 2018, Longwill, 2014, Cant and Taket, 2005, Askins, 2014, RedbridgeCVS, 2018, McLeish and Redshaw, 2015, McLeish and Redshaw, 2017, McLeish and Redshaw, 2017, McLeish and Redshaw, 2016). With the other themes detailed below, experiences sometimes differed within and between recipients, providers and referrers.

3.5.1. Service access

Early referrals and close collaboration between referrers and providers were considered important by both parties (Gray, 2002, Kellezi et al., 2020), though the outcome of referrals was not always communicated back to the referrer (Greater London Authority et al., 2020). Long waitlists were reported by some providers and recipients (Longwill, 2014, Gallagher and Featonby, 2019, Healthwatch Islington 2019). Providers also expressed concern about not being able to refuse inappropriate referrals due to unfilled gaps in service provision (Rowe et al., 2020, Trust for Developing Communities, 2020a, Sussex Interpreting Services 2020, Healthwatch Islington 2019, Greater London Authority et al., 2020). Even after entering the social prescribing service, some recipients felt a lack of readiness to accept help (Islam, 2019). Women sometimes felt that asking for help was a burden to others (McLeish and Redshaw, 2015, McLeish and Redshaw, 2017, McLeish and Redshaw, 2017, McLeish and Redshaw, 2016) or were unsure what help they could ask for (McLeish and Redshaw, 2015, McLeish and Redshaw, 2017, McLeish and Redshaw, 2017).

3.5.2. Service resourcing and coverage

While GPs making referrals to one programme considered continued funding for social prescribing a high priority (Longwill, 2014), discontinuation of funding and funding shortages was a challenge for providers (Sussex Interpreting Services 2018b, NHS Scotland 2014, Askins, 2014, Healthwatch Islington 2019, Wren, 2007, Greater London Authority et al., 2020) and limited their service capacity (South Yorkshire Housing Association 2020, Healthwatch Islington 2019, Kellezi et al., 2020). Limited coverage (Healthwatch Islington 2019, Wren, 2007) and strict eligibility criteria (Sussex Interpreting Services 2019) resulted in providers’ perceptions that migrants were ‘falling through gaps in service provision’ (Wren, 2007). Additionally, some recipients, providers and referrers perceived that service provision was not frequent enough or sessions were too short (Longwill, 2014, McLeish and Redshaw, 2016), while others felt services were flexible and adequate in timing and duration (Gallagher and Featonby, 2019, Sussex Interpreting Services 2018b, McLeish and Redshaw, 2015, McLeish and Redshaw, 2017, McLeish and Redshaw, 2017, McLeish and Redshaw, 2016).

3.5.3. Service delivery

Roles and boundaries between social prescribing and associated services were confusing to some recipients and providers (Islam, 2019, Healthwatch Islington 2019, Wren, 2007), and some recipients felt there were too many people involved in their case (Gray, 2002). The blurred lines between the role of professional and friend also made the relationship between link workers and their clients challenging (Tran, 2009, Gray, 2002, Gallagher and Featonby, 2019, Rowe et al., 2020, Trust for Developing Communities, 2020a, Sussex Interpreting Services 2020, McLeish and Redshaw, 2015, McLeish and Redshaw, 2017, McLeish and Redshaw, 2017, McLeish and Redshaw, 2016). Nevertheless, rapport and relationships between recipients, providers and other connected agencies was considered crucial to the success of social prescribing (Gallagher and Featonby, 2019, Rowe et al., 2020, Trust for Developing Communities, 2020a, Sussex Interpreting Services 2020, The British Academy 2017, Greater London Authority et al., 2020). Recipients discussed the need for time to build connections with the link worker (Islam, 2019), and that trust was grounded in longer term non-medical relationships with the provider (Islam, 2019, Askins, 2014, McLeish and Redshaw, 2015, McLeish and Redshaw, 2017, McLeish and Redshaw, 2017, Gray, 2002).

The tailoring of the environment to individual needs was also perceived to be important by all parties, particularly regarding language and interpreting (Gray, 2002, Sussex Interpreting Services 2018b, Rowe et al., 2020, Trust for Developing Communities, 2020a, Sussex Interpreting Services 2020, The British Academy 2017, Healthwatch Islington 2019, Parks, 2015, Greater London Authority et al., 2020, Kellezi et al., 2020) and gender-specific service delivery (Gallagher and Featonby, 2019, The British Academy 2017, McLeish and Redshaw, 2015, McLeish and Redshaw, 2017, McLeish and Redshaw, 2017, Healthwatch Islington 2019). While some recipients valued the cultural tailoring of services (Gray, 2002, Cant and Taket, 2005), others preferred providers with different sociocultural characteristics to reduce social pressure and gossip (McLeish and Redshaw, 2015, McLeish and Redshaw, 2017, McLeish and Redshaw, 2017). Some women also felt group environments in prescribed activities were stressful (McLeish and Redshaw, 2015, McLeish and Redshaw, 2017, McLeish and Redshaw, 2017). Additionally, recognising and responding to complex challenges were discussed as critical to the provider's role (Islam, 2019), such as taking into account multiple morbidities (Cant and Taket, 2005), considering the impact of trauma and safeguarding from harm and exploitation (Gray, 2002, The British Academy 2017, Kellezi et al., 2020).

3.5.4. Service capability

Some providers reported a lack of knowledge regarding migrant-specific health issues (e.g. entitlements to healthcare, barriers to GP registration) and the complex needs of specific migrant groups like asylum seekers (Voices in Exile 2020, Trust for Developing Communities, 2020b, Wren, 2007, Greater London Authority et al., 2020). However, other providers reported increased confidence and capability in their roles through on-the-job learning, multidisciplinary networking, or formal training in areas like cultural awareness, problem-solving, and migrants’ lived experiences (Voluntary Action Sheffield, 2018, Sussex Interpreting Services 2019, Askins, 2014, RedbridgeCVS, 2018, Greater London Authority et al., 2020).

3.5.5. External considerations

There were mixed reports from referrers about their awareness of social prescribing services (Islam, 2019, Longwill, 2014), though some described its benefits in assisting health and social care services to gain a more holistic understanding of patients’ needs (Tran, 2009). Providers, however, consistently reported that health and social care services demonstrated a lack of awareness of social prescribing models for migrants (Greater London Authority et al., 2020, Kellezi et al., 2020), and more broadly, a lack of awareness of the impacts of social prescribing on addressing migrant health needs (McLeish and Redshaw, 2016, Kellezi et al., 2020). Providers and recipients reported barriers for migrants in accessing healthcare services (Gallagher and Featonby, 2019, McLeish and Redshaw, 2015, McLeish and Redshaw, 2017, McLeish and Redshaw, 2017, Greater London Authority et al., 2020, Kellezi et al., 2020). Some recipients, particularly women, contrasted their experiences with social prescribing (and other related activities within the same programme) with their poor experiences of mainstream health and social care (The British Academy 2017, McLeish and Redshaw, 2015, McLeish and Redshaw, 2017, McLeish and Redshaw, 2017), including perceptions of misaligned priorities between recipients and health and medical professionals (McLeish and Redshaw, 2015, McLeish and Redshaw, 2017, McLeish and Redshaw, 2017, McLeish and Redshaw, 2016).

Finally, the ‘hostile environment’, which refers to immigration policies implemented by the UK government since 2012 that have been criticised as harsh and detrimental to the health and livelihood of vulnerable migrants (Weller et al., 2019), was mentioned by some providers as a barrier to successful social prescribing. For asylum seekers and those subject to immigration control, the lack of appropriate statutory service provision, instability and unpredictability as a result of dispersal and movement, discrimination and misinformation further complicated social prescribing provision (Gallagher and Featonby, 2019, Wren, 2007, Greater London Authority et al., 2020).

3.6. Quality of evidence

As detailed in Appendix B, most studies were low quality and fulfilled under half of the quality criteria in their respective appraisal checklist (25, 76%). A small proportion were medium quality (4, 12%) and high quality (4, 12%). Risk of bias was high in individual studies as well as across studies particularly regarding selective reporting of only positive outcomes. Internal validity was low, and some studies did not report the exact number of migrants in their sample. No comparator interventions were reported in any of the studies. There was inconsistent and infrequent reporting of measures of effect, and when effect measures were reported (Islam, 2019, Longwill, 2014, Gallagher and Featonby, 2019), it was unclear whether tools had been validated with migrant populations (Barkham et al., 2013, Pfizer 2014, Taggart et al., 2013, Paterson et al., 2007). Teasing out the effect of social prescribing in isolation was difficult due to the broad remit of programmes that encompassed more than just social prescribing activities. While qualitative studies provided more robust findings, it was difficult in some cases to separate the effect of the ‘link’ role from other concurrent roles that link workers played. Generalisability (external validity) was also low across studies as the majority were situated within very specific contexts.

4. Discussion

The UK is one of the first countries to embed social prescribing into its national healthcare policies, but there is room for improvement. It is clear that migrants require services that are specific to their health and wellbeing needs, and policies should reflect these requirements. As the evidence base for social prescribing in the UK is still in its formative stages, there is a policy imperative to finance and deliver social prescribing programmes in a way that integrates more robust evaluation processes.

4.1. Social prescribing effects

With the minimal use of validated tools and lack of comparative study designs, improvements to migrants’ health and wellbeing and changes in healthcare utilisation after social prescribing were mostly anecdotally reported. In studies involving migrant and non-migrant participants, it was often difficult to identify outcomes specific to migrants. Nonetheless, largely positive general wellbeing and mental health outcomes, particularly those measured using the same validated tools, were reported by studies involving migrants and studies that examined the general UK population (Bickerdike et al., 2017, Public Health England 2019, Islam, 2019, Longwill, 2014, Gallagher and Featonby, 2019). While there is a risk of selective reporting of positive outcomes regarding social prescribing, it can also suggest what works for a general population in social prescribing may improve the general wellbeing and mental health of migrant populations.

The high frequency of reporting of outcomes like confidence, empowerment and social connectivity for migrants compared to studies in the general UK population (Bickerdike et al., 2017, Public Health England 2019) could suggest migrants’ greater need for support to address these wider determinants of health (Allen et al., 2018, Phillimore et al., 2007). Improved access to mainstream healthcare services for migrants (Tran, 2009, Gray, 2002, Gallagher and Featonby, 2019, Sussex Interpreting Services 2017, McLeish and Redshaw, 2015, McLeish and Redshaw, 2017, McLeish and Redshaw, 2017) also reinforces that healthcare access, including access to more culturally and linguistically appropriate healthcare, can be an important outcome of social prescribing for migrants.

4.2. Implications for social prescribing approaches and implementation

The majority of studies described link workers providing prescribed activities themselves and/or undertaking additional roles not within the scope of the traditional link worker (NHS England 2020). This was reported more frequently in the literature about migrants than of the general population (Public Health England 2019), which could reflect less-established networks of services to support social prescribing for migrants. This highlights important implications for the implementation of social prescribing in migrant populations. First, future research should investigate whether the complexity of migrants’ needs is better addressed through a single-function link worker role coupled with improvements to programme networks (Sussex Interpreting Services 2019, Healthwatch Islington 2019, Wren, 2007), or through a transdisciplinary support role that combines elements of social prescribing alongside other support functions. Second, commissioners, service planners, service managers and referrers to social prescribing services should consider the additional responsibilities that link workers may take on when providing services to migrants, and how this may affect the way that link worker role boundaries are defined. Third, link workers should be equipped with sound knowledge of migrants’ entitlements to healthcare and other public services in the UK, as well as the skills to support migrants to assert their rights to accessing services (Greater London Authority et al., 2020). Finally, to address the complex needs of migrant typologies like asylum seekers, refugees, survivors of torture and survivors of human trafficking, link workers may require additional support and training to look after their own mental wellbeing whilst making appropriate decisions concerning clients’ health, wellbeing and safeguarding (McLeish and Redshaw, 2017).

Recommendations from the broader literature about the need for services to be responsive to individual preferences are also reflected in this review, particularly in relation to language, culture, gender and service delivery format (e.g. individual vs. group) (Gray, 2002, Gallagher and Featonby, 2019, Sussex Interpreting Services 2018b, Cant and Taket, 2005, Rowe et al., 2020, Trust for Developing Communities, 2020a, Sussex Interpreting Services 2020, The British Academy 2017, McLeish and Redshaw, 2015, McLeish and Redshaw, 2017, McLeish and Redshaw, 2017, Healthwatch Islington 2019, Parks, 2015, Greater London Authority et al., 2020, Kellezi et al., 2020). Entry into, continuity of, and preparedness of services is also an important consideration for migrants (Gallagher and Featonby, 2019, Wren, 2007, Greater London Authority et al., 2020) in the context of rapid changes to housing, legal status and location which can disrupt social prescribing plans (e.g. dispersal policies in the case of asylum seekers). Fluctuations in migrants’ readiness to engage with services vary at different points along their dynamic migration journeys highlights the need to identify a ‘window of opportunity’ for service provision (Public Health England 2021).

4.3. Implications for evaluation

Like other reviews of social prescribing for the general population in the UK (Bickerdike et al., 2017, Public Health England 2019), there is scarce evidence on social prescribing for migrant populations, a lack of robust data collection and low rigour of programme evaluation. Internal validity, reliability and external validity of the body of evidence were also low.

These limitations highlight an opportunity for better data collection and monitoring of social prescribing activities for migrants in the UK. For example, commissioners could ensure that social prescribing programmes are adequately funded not only to enable service delivery, but to also allow in-built robust evaluation with comparative study designs and prospective data collection (Bickerdike et al., 2017, Public Health England 2019). Improved measurement of social prescribing outcomes (Greater London Authority et al., 2020) could also be supported by using consistent frameworks like the NHS England and NHS Improvement Social Prescribing Common Outcomes Framework (NHS England 2020). Triangulation of provider- and patient-reported outcomes with routine data sources like electronic health records could improve the capturing of referral data and measures of effect for outcomes like healthcare utilisation (NHS England 2020). Patient-reported tools for measuring health and wellbeing outcomes should be validated in migrant populations and assessed for cultural and linguistic appropriateness (Wild et al., 2005). More thorough recording of the sociodemographic characteristics of social prescribing recipients, including indicators of migration like country of birth and migrant typology, will also enable a richer understanding of how social prescribing works and for whom (Bickerdike et al., 2017).

4.4. Strengths and limitations

This is the first evidence review of social prescribing for migrant populations in the UK. It incorporated a call for evidence to capture the breadth of social prescribing approaches, effects and implementation for migrants in published and unpublished literature. However, the inclusion of a greater number of studies came at the cost of poorer quality studies with low sample representativeness and high risk of sampling bias, observer bias and information bias. A large proportion of migrants in the included studies entered social prescribing via referral from healthcare services, and given the well-documented barriers to healthcare access faced by migrants (Agudelo-Suárez et al., 2012, Kang et al., 2019, O'Donnell et al., 2007), included studies were not likely representative of migrants who experience relatively greater barriers entering social prescribing programmes via traditional routes. Inclusion of studies where the effects of social prescribing on migrants could not be separated from the rest of the general population could have biased study selection, but the overall lack of ability to draw definitive conclusions about intervention effects from the poor quality evidence is consistent with studies of social prescribing in the general UK population (Bickerdike et al., 2017, Public Health England 2019). Despite the COVID-19 pandemic, a good response was received to the call for evidence, though pandemic pressures may have limited some stakeholders’ capacity to compile a submission.

5. Conclusions

This review systematically collated evidence to provide an overview of social prescribing for migrants in the UK and described gaps in the literature. While social prescribing has enabled healthcare, voluntary and community sector professionals to refer migrants to local and non-clinical services, positive outcomes were largely anecdotal in relation to health and wellbeing; healthcare utilisation; self-esteem, confidence and empowerment; and social connectivity. Approaches to implementation varied widely between programmes. Link workers frequently took on additional support roles and/or actively delivered parts of the prescribed activities themselves, and reasons behind this difference in social prescribing delivery for migrants requires further investigation. In addition to the types of activities prescribed for the general population, migrants were in some instances supported to access mainstream healthcare services, highlighting a pathway into healthcare services for migrants who may not have otherwise gained access. Provider responsiveness to the individual needs and preferences of migrants facilitated social prescribing success. Challenges with referral pathways, service funding and provider capability posed barriers to effective implementation. Link workers should be provided with appropriate training to address the complexities of migrants’ needs, including understanding migrants’ entitlements to public services, responding to trauma, and safeguarding from harm and exploitation. In future, more robust data collection of participant characteristics and measurement of outcomes together with rigorous evaluation designs will provide a better understanding of social prescribing coverage, implementation and outcomes for migrants in the UK.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author contributions

Conceptualisation, FW, CZ, ICM and DZ

Methodology, FW, CZ, ICM, RB, RA and AT

Formal analysis, FW, CZ, AB and SH

Writing - original draft, CZ and FW

Writing - review & editing, CZ, FW, ICM, AB, SH, DZ, RB, RA and AT

Project administration, CZ and FW

All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Declaration of interest

Dominik Zenner is an Associate Editor of the Journal of Migration and Health. No other authors have competing interests to declare.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Barbara Norrey for her advice on grey literature searching.

Contributor Information

Claire X. Zhang, Email: claire.zhang.19@ucl.ac.uk.

Fatima Wurie, Email: fatima.wurie@phe.gov.uk.

Annabel Browne, Email: annabel.browne@phe.gov.uk.

Steven Haworth, Email: shawora@essex.ac.uk.

Rachel Burns, Email: r.burns@ucl.ac.uk.

Robert Aldridge, Email: r.aldridge@ucl.ac.uk.

Dominik Zenner, Email: d.zenner@qmul.ac.uk.

Anh Tran, Email: anh.tran@phe.gov.uk.

Ines Campos-Matos, Email: ines.campos-matos@phe.gov.uk.

Appendix A. Methodology annex

A.1. Call for evidence

The call for evidence published on GOV.UK can be accessed at https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/social-prescribing-approaches-for-migrants-call-for-evidence.

A.2. Search terms

Database search strategies and grey literature search terms (Table A.1) were adapted from previous reviews of the UK social prescribing literature (Bickerdike et al., 2017, Public Health England 2019, Chatterjee et al., 2018) and expanded to capture the heterogeneity of terms used to describe social prescribing. For example, link worker roles have the same core elements as, and can in some situations be synonymous with, other roles in the UK such as community connectors and navigators (NHS England 2020), so these additional terms were included in the search strategy. Migration related search terms based on past evidence searches conducted for other Public Health England and UCL migrant health projects were also added to define the population of interest (Burns et al., 2021).

Table A.1.

Systematic search terms for grey literature search engines.

| Social prescribing terms | Migrant terms |

|---|---|

| "social prescribing" | migrant |

| "non-medical referral" | refugee |

| "exercise referral" | "asylum seeker" |

| "link worker" | |

| signpost | |

| "peer navigator" |

Table B.1.

Quality appraisal ratings for individual studies using the NICE Quality Appraisal Checklist Appendix F (quantitative intervention).

| Quality criteria | Tran, 2009 (quantitative components only) | Islam, 2019 (quantitative components only) | Longwill, 2014 (quantitative components only) | Gallagher & Featonby, 2019 (quantitative components only) | Healthwatch Islington, 2019 (quantitative components only) | Sussex Interpreting Services, 2017 | Sussex Interpreting Services, 2018a | Sussex Interpreting Services, 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.1. Is the source population or source area well described? | Yes/appropriate | Yes/appropriate | Yes/appropriate | Yes/appropriate | Unclear/not all sources of bias addressed | No/significant sources of bias persist | No/significant sources of bias persist | No/significant sources of bias persist |

| 1.2. Is the eligible population or area representative of the source population or area? | Unclear/not all sources of bias addressed | Unclear/not all sources of bias addressed | Unclear/not all sources of bias addressed | Yes/appropriate | No/significant sources of bias persist | No/significant sources of bias persist | No/significant sources of bias persist | No/significant sources of bias persist |

| 1.3. Do the selected participants or areas represent the eligible population or area? | Unclear/not all sources of bias addressed | Unclear/not all sources of bias addressed | Unclear/not all sources of bias addressed | Unclear/not all sources of bias addressed | No/significant sources of bias persist | No/significant sources of bias persist | No/significant sources of bias persist | No/significant sources of bias persist |

| 2.1. Allocation to intervention (or comparison). How was selection bias minimised? | Unclear/not all sources of bias addressed | No/significant sources of bias persist | No/significant sources of bias persist | No/significant sources of bias persist | No/significant sources of bias persist | No/significant sources of bias persist | No/significant sources of bias persist | No/significant sources of bias persist |

| 2.2. Were interventions (and comparisons) well described and appropriate? | Yes/appropriate | Yes/appropriate | Yes/appropriate | Yes/appropriate | No/significant sources of bias persist | Yes/appropriate | Yes/appropriate | Yes/appropriate |

| 2.3. Was the allocation concealed? | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 2.4. Were participants or investigators blind to exposure and comparison? | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 2.5. Was the exposure to the intervention and comparison adequate? | Yes/appropriate | Yes/appropriate | Yes/appropriate | Unclear/not all sources of bias addressed | Unclear/not all sources of bias addressed | Unclear/not all sources of bias addressed | Unclear/not all sources of bias addressed | Unclear/not all sources of bias addressed |

| 2.6. Was contamination acceptably low? | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 2.7. Were other interventions similar in both groups? | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 2.8. Were all participants accounted for at study conclusion? | No/significant sources of bias persist | No/significant sources of bias persist | No/significant sources of bias persist | Unclear/not all sources of bias addressed | No/significant sources of bias persist | No/significant sources of bias persist | No/significant sources of bias persist | No/significant sources of bias persist |

| 2.9. Did the setting reflect usual UK practice? | Not reported | Unclear/not all sources of bias addressed | Unclear/not all sources of bias addressed | No/significant sources of bias persist | Unclear/not all sources of bias addressed | Unclear/not all sources of bias addressed | Unclear/not all sources of bias addressed | Unclear/not all sources of bias addressed |

| 2.10. Did the intervention or control comparison reflect usual UK practice? | Unclear/not all sources of bias addressed | Unclear/not all sources of bias addressed | Unclear/not all sources of bias addressed | No/significant sources of bias persist | Unclear/not all sources of bias addressed | Unclear/not all sources of bias addressed | Unclear/not all sources of bias addressed | Unclear/not all sources of bias addressed |

| 3.1. Were outcome measures reliable? | Unclear/not all sources of bias addressed | Unclear/not all sources of bias addressed | Unclear/not all sources of bias addressed | No/significant sources of bias persist | No/significant sources of bias persist | No/significant sources of bias persist | No/significant sources of bias persist | No/significant sources of bias persist |

| 3.2. Were all outcome measurements complete? | Unclear/not all sources of bias addressed | No/significant sources of bias persist | Unclear/not all sources of bias addressed | Unclear/not all sources of bias addressed | Unclear/not all sources of bias addressed | No/significant sources of bias persist | No/significant sources of bias persist | No/significant sources of bias persist |

| 3.3. Were all important outcomes assessed? | No/significant sources of bias persist | No/significant sources of bias persist | Unclear/not all sources of bias addressed | No/significant sources of bias persist | No/significant sources of bias persist | No/significant sources of bias persist | No/significant sources of bias persist | No/significant sources of bias persist |

| 3.4. Were outcomes relevant? | Yes/appropriate | Unclear/not all sources of bias addressed | Yes/appropriate | Yes/appropriate | Unclear/not all sources of bias addressed | Yes/appropriate | Yes/appropriate | Yes/appropriate |

| 3.5. Were there similar follow-up times in exposure and comparison groups? | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 3.6. Was follow-up time meaningful? | Unclear/not all sources of bias addressed | Unclear/not all sources of bias addressed | Unclear/not all sources of bias addressed | Unclear/not all sources of bias addressed | N/A | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| 4.1. Were exposure and comparison groups similar at baseline? If not, were these adjusted? | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 4.2. Was intention to treat (ITT) analysis conducted? | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 4.3. Was the study sufficiently powered to detect an intervention effect (if one exists)? | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 4.4. Were the estimates of effect size given or calculable? | No/significant sources of bias persist | Unclear/not all sources of bias addressed | Unclear/not all sources of bias addressed | No/significant sources of bias persist | No/significant sources of bias persist | No/significant sources of bias persist | No/significant sources of bias persist | No/significant sources of bias persist |

| 4.5. Were the analytical methods appropriate? | Unclear/not all sources of bias addressed | Unclear/not all sources of bias addressed | Unclear/not all sources of bias addressed | Unclear/not all sources of bias addressed | No/significant sources of bias persist | No/significant sources of bias persist | No/significant sources of bias persist | No/significant sources of bias persist |

| 4.6. Was the precision of intervention effects given or calculable? Were they meaningful? | No/significant sources of bias persist | No/significant sources of bias persist | No/significant sources of bias persist | No/significant sources of bias persist | No/significant sources of bias persist | No/significant sources of bias persist | No/significant sources of bias persist | No/significant sources of bias persist |

| 5.1. Are the study results internally valid (i.e. unbiased)? | No/significant sources of bias persist | No/significant sources of bias persist | No/significant sources of bias persist | Unclear/not all sources of bias addressed | No/significant sources of bias persist | No/significant sources of bias persist | No/significant sources of bias persist | No/significant sources of bias persist |

| 5.2. Are the findings generalisable to the source population (i.e. externally valid)? | Unclear/not all sources of bias addressed | Unclear/not all sources of bias addressed | No/significant sources of bias persist | Unclear/not all sources of bias addressed | No/significant sources of bias persist | No/significant sources of bias persist | No/significant sources of bias persist | No/significant sources of bias persist |

| Overall rating | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

Individual rating: Yes/appropriate, Unclear/not all sources of bias addressed, No/significant sources of bias persist, Not reported, Not applicable (N/A).

Overall rating: Low quality <50% of the quality criteria fulfilled; Medium quality 50–75% of the quality criteria fulfilled; High quality >75% of the quality criteria fulfilled.

Table B.2.

Quality appraisal ratings for individual studies using the NICE Quality Appraisal Checklist Appendix H (qualitative).

| Quality criteria | McLeish & Redshaw, 2015, 2017a & 2017b | McLeish & Redshaw, 2016 | Healthwatch Islington, 2019 (qualitative components only) | Parks, 2015 | Wren, 2007 | Tran, 2009 (qualitative components only) | Islam, 2019 (qualitative components only) | Longwill, 2014 (qualitative components only) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Is a qualitative approach appropriate? | Yes/appropriate | Yes/appropriate | Yes/appropriate | Yes/appropriate | Yes/appropriate | Yes/appropriate | Unclear | Yes/appropriate |

| 2. Is the study clear in what it seeks to do? | Yes/appropriate | Yes/appropriate | No/not appropriate/inadequate | Yes/appropriate | Yes/appropriate | No/not appropriate/inadequate | No/not appropriate/inadequate | No/not appropriate/inadequate |

| 3. How defensible/rigorous is the research design/methodology? | Yes/appropriate | Yes/appropriate | No/not appropriate/inadequate | Yes/appropriate | Yes/appropriate | No/inadequate | No/inadequate | No/inadequate |

| 4. How well was the data collection carried out? | Yes/appropriate | Yes/appropriate | No/inadequate | Yes/appropriate | Yes/appropriate | Unclear | No/inadequate | No/inadequate |

| 5. Is the role of the researcher clearly described? | Yes/appropriate | Yes/appropriate | No/inadequate | Yes/appropriate | No/inadequate | No/inadequate | No/inadequate | No/inadequate |

| 6. Is the context clearly described? | Yes/appropriate | Yes/appropriate | No/inadequate | Yes/appropriate | Yes/appropriate | Yes/appropriate | No/inadequate | No/inadequate |

| 7. Were the methods reliable? | No/inadequate | No/inadequate | No/inadequate | Yes/appropriate | Yes/appropriate | No/inadequate | No/inadequate | No/inadequate |

| 8. Is the data analysis sufficiently rigorous? | Yes/appropriate | Yes/appropriate | No/inadequate | Yes/appropriate | Yes/appropriate | Yes/appropriate | No/inadequate | No/inadequate |

| 9. Is the data 'rich'? | Yes/appropriate | Yes/appropriate | No/inadequate | Yes/appropriate | No/inadequate | No/inadequate | No/inadequate | No/inadequate |

| 10. Is the analysis reliable? | No/inadequate | No/inadequate | No/inadequate | No/inadequate | Unclear | No/inadequate | No/inadequate | No/inadequate |

| 11. Are the findings convincing? | Yes/appropriate | Yes/appropriate | No/inadequate | Yes/appropriate | Yes/appropriate | No/inadequate | No/inadequate | No/inadequate |

| 12. Are the findings relevant to the aims of the study? | Yes/appropriate | Yes/appropriate | Yes/appropriate | Yes/appropriate | No/inadequate | No/inadequate | Unclear | Yes/appropriate |

| 13. Conclusions, and is there adequate discussion of any limitations encountered? | Yes/appropriate | Yes/appropriate | Yes/appropriate | No/inadequate | No/inadequate | No/inadequate | No/inadequate | No/inadequate |

| 14. How clear and coherent is the reporting of ethics? | Yes/appropriate | Yes/appropriate | No/inadequate | No/inadequate | No/inadequate | Yes/appropriate | No/inadequate | No/inadequate |

| Overall rating | High | High | Low | Medium | Medium | Low | Low | Low |

Table B.2 (continued).

| Quality criteria | Gallagher & Featonby, 2019 (qualitative components only) | Grey, 2002 | Askins, 2014 | Cant & Taket, 2005 | NHS Scotland, 2014 | HEAR Equality and Human Rights Network, Greater London Authority & London Plus, 2020 | Kellezi et al., 2020 | Voluntary Action Sheffield, 2018 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Is a qualitative approach appropriate? | Yes/appropriate | Yes/appropriate | Yes/appropriate | Yes/appropriate | Unclear | Unclear | Yes/appropriate | Unclear |

| 2. Is the study clear in what it seeks to do? | Yes/appropriate | No/inadequate | Yes/appropriate | No/inadequate | No/inadequate | Yes/appropriate | Yes/appropriate | No/inadequate |

| 3. How defensible/rigorous is the research design/methodology? | No/inadequate | No/inadequate | No/inadequate | No/inadequate | No/inadequate | No/inadequate | No/inadequate | No/inadequate |

| 4. How well was the data collection carried out? | Unclear | Yes/appropriate | Yes/appropriate | No/inadequate | No/inadequate | No/inadequate | No/inadequate | No/inadequate |

| 5. Is the role of the researcher clearly described? | No/inadequate | Yes/appropriate | No/inadequate | No/inadequate | No/inadequate | No/inadequate | No/inadequate | No/inadequate |

| 6. Is the context clearly described? | Yes/appropriate | Yes/appropriate | No/inadequate | Yes/appropriate | No/inadequate | Yes/appropriate | Yes/appropriate | No/inadequate |

| 7. Were the methods reliable? | No/inadequate | No/inadequate | Yes/appropriate | Yes/appropriate | No/inadequate | No/inadequate | Unclear | No/inadequate |

| 8. Is the data analysis sufficiently rigorous? | No/inadequate | No/inadequate | No/inadequate | Yes/appropriate | No/inadequate | No/inadequate | No/inadequate | No/inadequate |

| 9. Is the data 'rich'? | Yes/appropriate | No/inadequate | Yes/appropriate | Yes/appropriate | No/inadequate | No/inadequate | No/inadequate | No/inadequate |

| 10. Is the analysis reliable? | No/inadequate | No/inadequate | No/inadequate | No/inadequate | No/inadequate | Unclear | Unclear | No/inadequate |

| 11. Are the findings convincing? | No/inadequate | No/inadequate | Yes/appropriate | Yes/appropriate | No/inadequate | No/inadequate | No/inadequate | No/inadequate |

| 12. Are the findings relevant to the aims of the study? | Yes/appropriate | Unclear | Yes/appropriate | Yes/appropriate | No/inadequate | Yes/appropriate | Yes/appropriate | No/inadequate |

| 13. Conclusions, and is there adequate discussion of any limitations encountered? | Yes/appropriate | No/inadequate | Yes/appropriate | Yes/appropriate | No/inadequate | Yes/appropriate | Yes/appropriate | No/inadequate |

| 14. How clear and coherent is the reporting of ethics? | No/inadequate | No/inadequate | Yes/appropriate | Yes/appropriate | No/inadequate | No/inadequate | Unclear | No/inadequate |

| Overall rating | Low | Low | Medium | Medium | Low | Low | Low | Low |

Individual rating: Yes/appropriate, No/inadequate, Unclear, Not applicable (N/A).

Overall rating: Low quality <50% of the quality criteria fulfilled; Medium quality 50–75% of the quality criteria fulfilled; High quality >75% of the quality criteria fulfilled.

Table B.3.

Quality appraisal ratings for individual studies using The Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Checklist for Case Reports.

| Quality criteria | RedbridgeCVS, 2018 | Sussex Interpreting Services, 2018b | Rowe et al., Trust for Developing Communities & Sussex Interpreting Services, 2020 | Voices in Exile & Trust for Developing Communities, 2020 | Dayson & Leather, 2020 | The British Academy, 2017 | St Helen's Council, 2014 | South Yorkshire Housing Association, 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Were patient's demographic characteristics clearlydescribed? | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| 2. Was the patient's history clearly described and presented as a timeline? | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| 3. Was the current clinical condition of the patient onpresentation clearly described? | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| 4. Were diagnostic tests or assessment methods and theresults clearly described? | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 5. Was the intervention(s) or treatment procedure(s) clearlydescribed? | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| 6. Was the post-intervention clinical condition clearlydescribed? | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| 7. Were adverse events (harms) or unanticipated events identified and described? | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| 8. Does the case report provide takeaway lessons? | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Overall rating | Low | Low | Low | Low | Medium | Low | Low | Medium |

Individual rating: Yes, No, Unclear, Not applicable (N/A).

Overall rating: Low quality <50% of the quality criteria fulfilled; Medium quality 50–75% of the quality criteria fulfilled; High quality >75% of the quality criteria fulfilled.

A.3. Example search strategy

Database: Embase <1980 to 2020 Week 23>

Search Strategy:

——————————————————————————–

-

1

exp *migrant/

-

2

exp *migration/

-

3

exp *refugee/

-

4

exp *undocumented immigrant/

-

5

human trafficking/

-

6

((international or oversea*) adj2 student*).tw.

-

7

(migrant* or immigrant* or emigrant* or refugee* or "asylum seeker*" or "displaced person*" or "temporarily displaced" or expat* or departe* or foreign* or traffick* or "undocumented migra*").tw.

-

8

1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7

-

9

"social prescri*".tw.

-

10

((community or non-medical or supported or non-medical) adj1 referral*).tw.

-

11

"non-clinical intervention*".tw.

-

12

"referral scheme*".tw.

-

13

((exercise or "physical activity") adj1 referral*).tw.

-

14

((wellbeing or "well being" or voluntary or statutory or peer or outreach or education* or housing or community) adj (program* or support or service*)).tw.

-

15

((exercise or art* or book* or gardening) adj1 prescrib*).tw.

-

16

("link worker*" or "care navigator*" or "peer navigator").tw.

-

17

(referral adj (agent* or co-ordinator*)).tw.

-

18

signpost*.tw.

-

19

or/9–18

-

20

*patient referral/

-

21

((GP or primary care) adj2 referral*).tw.

-

22

14 or 15

-

23

20 or 21

-

24

8 and 19

-

25

8 and 22 and 23

***************************

A.4. Identification of migrants

Migrants were explicitly labelled as ‘migrant’ in their respective study or were inferred by the reviewers to be migrants using indicators like country of birth, English as a second or other language, interpreter need and immigration status.

Appendix B

Quality appraisal

References

- Abubakar I., Aldridge R.W., Devakumar D., Orcutt M., Burns R., Barreto M.L. The UCL–Lancet Commission on Migration and Health: the health of a world on the move. Lancet. 2018;392(10164):2606–2654. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32114-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agudelo-Suárez A.A., Gil-González D., Vives-Cases C., Love J.G., Wimpenny P., Ronda-Pérez E. A metasynthesis of qualitative studies regarding opinions and perceptions about barriers and determinants of health services’ accessibility in economic migrants. BMC Heal. Serv. Res. 2012;12 doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-12-461. [Online] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen J., Goldblatt P., Daly S., Jabbal J., Marmott M. 2018. Reducing Health Inequalities Through New Models of Care: A Resource for New Care Models.http://www.instituteofhealthequity.org/resources-reports/reducing-health-inequalities-through-new-models-of-care-a-resource-for-new-care-models (accessed May 4, 2020) [Google Scholar]

- Askins K. 2014. Being Together: Exploring the West End Refugee Service Befriending Scheme Research Report.http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/99205/1/99205.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Barkham M., Bewick B., Mullin T., Gilbody S., Connell J., Cahill J., Mellor-Clark J., Richards D., Unsworth G., Evans C. The CORE-10: a short measure of psychological distress for routine use in the psychological therapies. Couns. Psychother. Res. 2013;13:3–13. doi: 10.1080/14733145.2012.729069. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bickerdike L., Booth A., Wilson P.M., Farley K., Wright K. Social prescribing: less rhetoric and more reality. A systematic review of the evidence. BMJ Open. 2017;7 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth A., Wilson P., Bickerdike L., Farley K. 2015. Social Prescribing: A Systematic Review of the Evidence; pp. 1–4.https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42015023501%0AReview PROSPERO 2015 CRD42015023501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns R., Zhang C.X., Patel P., Eley I., Campos-Matos I., Aldridge R.A. Migration health research in the United Kingdom: a scoping review. J. Migr. Heal. 2021;4:100061. doi: 10.1016/j.jmh.2021.100061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cant B., Taket A. Promoting social support and social networks among Irish pensioners in South London, UK. Divers. Heal. Soc. Care. 2005;2:263–270. https://diversityhealthcare.imedpub.com/promoting-social-support-and-social-networks-among-irish-pensioners-in-south-london-uk.php?aid=2471 accessed April 21, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee H.J., Camic P.M., Lockyer B., Thomson L.J.M. Non-clinical community interventions: a systematised review of social prescribing schemes. Arts Health. 2018;10:97–123. doi: 10.1080/17533015.2017.1334002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dayson C., Leather D. 2020. Evaluation of HALE Community Connectors Social Prescribing Service 2018-19.http://shura.shu.ac.uk/25768/1/eval-HALE-comm-connectors-social-prescribing-service-2018-19.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher J., Featonby J. 2019. Hope for the Future: Support for Survivors of Trafficking after the National Referral Mechanism. UK Integration Pilot – Evaluation and Policy Report.https://www.redcross.org.uk/-/media/documents/about-us/research-publications/human-trafficking-and-modern-slavery/hope-for-the-future.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Garritty C., Gartlehner G., Kamel C., King V.J., Nussbaumer-Streit B., Stevens A., Hamel C., Affengruber L. 2020. Cochrane Rapid Reviews: Interim Guidance from the Cochrane Rapid Reviews Methods Group. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray B. Working with families in Tower Hamlets: an evaluation of the Family Welfare Association's Family Support Services. Health Soc. Care Commun. 2002;10:112–122. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2524.2002.00347.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HEAR Equality and Human Rights Network. Greater London Authority, London Plus, HEAR Equality and Human Rights Network . 2020. Public Health England Consultation on Social Prescribing Approaches for Migrants: Response from the Mayor of London (unpublished results) [Google Scholar]

- Healthwatch Islington . 2019. Social Prescribing and Navigation Services in Islington.https://www.healthwatchislington.co.uk/sites/healthwatchislington.co.uk/files/DiverseCommunities2019_0.pdf accessed April 23, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Husk K., Elston J., Gradinger F., Callaghan L., Asthana S. Social prescribing: where is the evidence? Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2019;69:6–7. doi: 10.3399/bjgp19x700325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Organization for Migration . 2019. Glossary on Migration.https://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/iml_34_glossary.pdf accessed June 17, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Islam N. 2019. Social Prescribing Service Bromley by Bow Centre Annual Report: April 2018 - March 2019.https://www.bbbc.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/BBBC-Social-Prescribing-Annual-Report-April-2018-March-2019-FINAL.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Kang C., Tomkow L., Farrington R. Access to primary health care for asylum seekers and refugees: a qualitative study of service user experiences in the UK. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2019;69:e537–e545. doi: 10.3399/bjgp19x701309. [Online]Available from: <doi:10.3399/bjgp19×701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellezi B., Bowe M., Wakefield J. 2020. Public Health England Social Prescribing Approaches for Migrants: Call for Evidence Submission (unpublished results)http://irep.ntu.ac.uk/id/eprint/42633/1/1427901_Kellezi.pdf [Google Scholar]

- London Assembly, Health Committee meeting: social prescribing in London (Appendix 1), n.d. https://www.london.gov.uk/about-us/londonassembly/meetings/documents/s73422/05aSPscopingpaper.pdf.

- Longwill A. 2014. Independent Evaluation of Hackney WellFamily Service.https://www.family-action.org.uk/content/uploads/2014/07/WellFamily-Evaluation-Executive-Summary.pdf [Google Scholar]

- McLeish J., Redshaw M. Peer support during pregnancy and early parenthood: a qualitative study of models and perceptions. BMC Pregnancy Childb. 2015;15 doi: 10.1186/s12884-015-0685-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeish J., Redshaw M. We have beaten HIV a bit”: a qualitative study of experiences of peer support during pregnancy with an HIV Mentor Mother project in England. BMJ Open. 2016;6 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeish J., Redshaw M. I didn’t think we’d be dealing with stuff like this”: a qualitative study of volunteer support for very disadvantaged pregnant women and new mothers. Midwifery. 2017;45:36–43. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2016.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeish J., Redshaw M. Mothers’ accounts of the impact on emotional wellbeing of organised peer support in pregnancy and early parenthood: a qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy Childb. 2017;17 doi: 10.1186/s12884-017-1220-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moola S., Munn Z., Tufanaru C., Aromataris E., Sears K., Sfetcu R., Currie M., Qureshi R., Mattis P., Lisy K., Mu P.-.F. In: Joanna Briggs Inst. Rev. Man. Aromataris E., Munn Z., editors. The Joanna Briggs Institute; 2017. Chapter 7: systematic reviews of etiology and risk.https://reviewersmanual.joannabriggs.org/ [Google Scholar]

- National Health Service . 2019. The NHS Long Term Plan.https://www.longtermplan.nhs.uk/publication/nhs-long-term-plan/ [Google Scholar]