Abstract

Increasingly countries are seeking to reduce emission of greenhouse gases from the agricultural industries, and livestock production in particular, as part of their climate change management. While many reviews update progress in mitigation research, a quantitative assessment of the efficacy and performance-consequences of nutritional strategies to mitigate enteric methane (CH4) emissions from ruminants has been lacking. A meta-analysis was conducted based on 108 refereed papers from recent animal studies (2000–2020) to report effects on CH4 production, CH4 yield and CH4 emission intensity from 8 dietary interventions. The interventions (oils, microalgae, nitrate, ionophores, protozoal control, phytochemicals, essential oils and 3-nitrooxypropanol). Of these, macroalgae and 3-nitrooxypropanol showed greatest efficacy in reducing CH4 yield (g CH4/kg of dry matter intake) at the doses trialled. The confidence intervals derived for the mitigation efficacies could be applied to estimate the potential to reduce national livestock emissions through the implementation of these dietary interventions.

Keywords: Beef cattle, Methane emissions abatement, Dairy cattle, Greenhouse gas, Sheep

1. Introduction

Recognising the urgent need to address climate change, nations have agreed to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, aiming for net zero emissions by the second half of this century (UNFCCC, 2015). Livestock enteric methane (CH4) contributes 11.6% of global GHG emissions from anthropogenic activities (Ripple et al., 2014), and it is the main source of GHG in agriculture, accounting for 43% of the GHG emissions from livestock globally (Herrero et al., 2016). Enteric CH4 emissions represent a waste of energy by the ruminant fermentation process, and efforts are being made to identify and encourage actions to reduce these emissions (Rivera-Ferre et al., 2016).

As CH4 has a relatively brief lifetime in the atmosphere (i.e., from 8.4 to 12 years, Ehhalt et al., 2001), mitigating CH4 may represent a timely contribution to achieving climate stabilisation targets (Reisinger et al., 2021). Mitigation efficacy of these many strategies have been reported and often combined in broad-ranging reviews (Martin et al., 2010; Cottle et al., 2011; Asizua et al., 2014; Patra, 2016; Grossi et al., 2019), the effect of feed management on animal productivity is less well assessed. Progress towards carbon neutrality for the ruminant production sector may involve nutritional strategies, as well as whole farm systematic approaches including vaccines, improving reproductive rate, stock number and productivity, pasture management and animal genetics.

The nutritional approach, more specifically rumen manipulation, encompasses a wide range of possibilities (e.g., oils, algae, nitrate, ionophores, protozoa population control, bacteriocins, phytochemicals, 3-nitrooxypropanol, acetogens, organic acids, among others). In this meta-analysis, we focus on nutritional strategies that are more likely to contribute to carbon neutrality in the near decades. Therefore, the approach of this assessment is to use CH4 mitigation data published since 2000 to quantify the technical potential of strategies for CH4 mitigation by ruminants (cattle and sheep), as well as quantifying the co-benefits and identifying barriers to implementation. The ultimate purpose of this assessment is to estimate the CH4 mitigation potential of nutritional strategies to inform the development of effective policies to support CH4 abatement.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Published literature screening

A database was created with publications from 2000 to 2020, using only reports of in vivo trials that measured ruminant enteric CH4 emissions. Studies included addressed the effects of a range of dietary abatement measures (oils, algae, nitrate, ionophores, protozoa population control, bacteriocins, phytochemicals, 3-nitrooxypropanol, acetogens, organic acids). Keywords used to identify papers were as follows: “ruminant”, “enteric”, “methane emission”, and one of the potential strategies. Pertinent literature cited in each considered article was also screened for inclusion. All data were from articles published in indexed journals identified through searches conducted using the Google Scholar search engine (https://scholar.google.com) from 18th of August 2019 to 26th of April 2020. Data were entered in an Excel spreadsheet in a systematic fashion in which each row represented a treatment and each column represented an exploratory variable (Sauvant et al., 2008). A summary of the data of all publications is presented in Table 1. Data reported in divergent units of measure were transformed to matching units. When a study did not report all needed results and it was possible to calculate from the reported data, appropriate calculations were performed from the reported data.

Table 1.

Summary of the data used in the meta-analysis of the effect of different strategies for enteric methane abatement.

| Study code | Source | Animal | Strategy | Methane analysis method | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Alemu et al. (2019) | Sheep | Phytochemicals, NO3- | GreenFeed | 22 |

| 2 | Beauchemin et al. (2006) | Beef | Phytochemicals, oil, organic acid | Chamber | 8 |

| 3 | Beauchemin et al. (2007) | Beef | Oil | Chamber | 4 |

| 4 | Beauchemin et al. (2009) | Dairy | Oil, protozoa control | Chamber | 4 |

| 5 | Benchaar (2016) | Dairy | Phytochemicals, ionophores | SF6 | 8 |

| 6 | Benchaar et al. (2015) | Dairy | Oil, protozoa control | Chamber | 6 |

| 7 | Bird et al. (2008) | Sheep | Protozoa control | Chamber | 7 |

| 8 | Caetano et al. (2019) | Beef | Phytochemicals | GreenFeed | 10 |

| 9 | Carulla et al. (2005) | Sheep | Phytochemicals, protozoa control | Chamber | 6 |

| 10 | Carvalho et al. (2016) | Beef | Oil | SF6 | 9 |

| 11 | Chung et al. (2013) | Beef | Phytochemicals, protozoa control | Chamber | 8 |

| 12 | Cooprider et al. (2011) | Beef | Ionophores | Chamber | 4 |

| 13 | Cosgrove et al. (2008) | Sheep | Oil | SF6 | 2 |

| 14 | Ding et al. (2012) | Sheep | Oil | other | 3 |

| 15 | Duthie et al. (2018) | Beef | NO3- | Chamber | 18 |

| 16 | El-Zaiat et al. (2014) | Sheep | Phytochemicals, NO3- | Chamber | 6 |

| 17 | Fiorentini et al. (2014) | Beef | Oil, protozoa control | SF6 | 9 |

| 18 | Grainger et al. (2008) | Dairy | Oil | SF6 | 6 |

| 19 | Grainger et al. (2008b) | Dairy | Ionophores | Chamber/SF6 | 15 |

| 20 | Grainger et al. (2009) | Dairy | Phytochemicals | SF6 | 10 |

| 21 | Grainger et al. (2010) | Dairy | Ionophores | Chamber/SF6 | 10/15 |

| 22 | Granja-Salcedo et al. (2019) | Beef | NO3- | SF6 | 10 |

| 23 | Guyader et al. (2015a) | Dairy | phytochemicals, NO3- | Chamber | 4 |

| 24 | Guyader et al. (2015b) | Dairy | Oil, NO3-, protozoa control | Chamber | 4 |

| 25 | Guyader et al. (2016) | Dairy | Oil, NO3- | Chamber | 8 |

| 26 | Haisan et al. (2014) | Dairy | 3-nitrooxypropanol (3-NOP) | SF6 | 5 |

| 27 | Haisan et al. (2017) | Dairy | 3-NOP | SF6 | 6 |

| 28 | Hegarty et al. (2008) | Sheep | Protozoa control | Chamber | 6 |

| 29 | Hess et al. (2016) | Sheep | Phytochemicals, protozoa control | Chamber | 6 |

| 30 | Hollmann et al. (2012) | Dairy | Oil | Chamber | 6 |

| 31 | Holtshausen et al. (2009) | Dairy | Phytochemicals, protozoa control | Chamber/SF6 | 4 |

| 32 | Hosoda et al. (2005) | Dairy | Phytochemicals | Chamber | 4 |

| 33 | Hristov et al. (2013) | Dairy | Phytochemicals | SF6 | 8 |

| 34 | Hristov et al. (2015) | Dairy | 3-NOP | GreenFeed | 12 |

| 35 | Hulshof et al. (2012) | Beef | NO3- | SF6 | 8 |

| 36 | Hünerberg et al. (2013a) | Beef | Oil | Chamber | 8 |

| 37 | Hünerberg et al. (2013b) | Beef | Oil | Chamber | 4 |

| 38 | Johnson et al. (2002) | Dairy | Oil | SF6 | 4 |

| 39 | Jordan et al. (2006a) | Beef | Oil | Chamber | 10 |

| 40 | Jordan et al. (2006b) | Beef | Oil | SF6 | 12 |

| 41 | Jordan et al. (2007) | Beef | Oil | SF6 | 4 |

| 42 | Jose Neto et al. (2019) | Beef | Oil | SF6 | 9 |

| 43 | Kim et al. (2019) | Beef | 3-NOP | GreenFeed | 9 |

| 44 | Kinley et al. (2020) | Beef | Seaweed | Chamber | 5 |

| 45 | Klevenhusen et al. (2011) | Sheep | Phytochemicals, protozoa control | Chamber | 6 |

| 46 | Lee et al. (2015) | Beef | NO3- | Chamber | 8 |

| 47 | Lee et al. (2017) | Beef | NO3- | Chamber | 7 |

| 48 | Lee et al. (2017) | Beef | NO3- | Chamber | 7 |

| 49 | Li et al. (2012) | Sheep | NO3- | Chamber | 5 |

| 50 | Li et al. (2013) | Sheep | NO3- | Chamber | 6 |

| 51 | Li et al. (2018) | Sheep | Seaweed | Chamber | 6 |

| 52 | Liu et al. (2011) | Sheep | Phytochemicals, oil | Chamber | 8 |

| 53 | Lopes et al. (2016) | Dairy | 3-NOP | GreenFeed | 6 |

| 54 | Ma et al. (2015) | Sheep | Phytochemicals | Chamber | 6 |

| 55 | Ma et al. (2017) | Sheep | Phytochemicals | Chamber | 6 |

| 56 | Machmüller et al. (2000) | Sheep | Oil, protozoa control | Chamber | 3 |

| 57 | Machmüller et al. (2001) | Sheep | Oil, protozoa control | Chamber | 3 |

| 58 | Machmüller et al. (2003) | Sheep | Oil, protozoa control | Chamber | 3 |

| 59 | Malik et al. (2017) | Sheep | Phytochemicals, protozoa control | SF6 | 10 |

| 60 | Mao et al. (2010) | Sheep | Phytochemicals, oil | Chamber | 8 |

| 61 | Martin et al. (2008) | Dairy | Oil | SF6 | 8 |

| 62 | Martin et al. (2016) | Dairy | Oil | SF6 | 4 |

| 63 | Martinez-Fernandez et al. (2018) | Beef | 3-NOP | Chamber | 4 |

| 64 | McGinn et al. (2004) | Beef | Oil, organic acid, ionophores | Chamber | 8 |

| 65 | McGinn et al. (2009) | Beef | Oil | SF6 | 30 |

| 66 | Melgar et al. (2020) | Dairy | NO3- | GreenFeed | 24 |

| 67 | Moate et al. (2011) | Dairy | Oil | Chamber | 4 |

| 68 | Moate et al. (2014) | Dairy | Phytochemicals, protozoa control | SF6 | 10 |

| 69 | Mohammed et al. (2004) | Dairy | Phytochemicals, protozoa control | Chamber | 4 |

| 70 | Moreira et al. (2013) | Sheep | Phytochemicals | SF6 | 3 |

| 71 | Mwenya et al. (2005) | Dairy | Ionophores | Other | 4 |

| 72 | Newbold et al. (2014) | Beef | NO3- | Chamber | 6 |

| 73 | Nguyen and Hegarty (2017) | Beef | Oil, protozoa control | Chamber | 6 |

| 74 | Nolan et al. (2010) | Sheep | NO3- | Chamber | 4 |

| 75 | Norris et al. (2020) | Beef | Phytochemicals, protozoa control | Chamber | 8 |

| 76 | Odongo et al. (2007) | Dairy | Oil | Chamber | 6 |

| 77 | Odongo et al. (2007b) | Dairy | Ionophores | Other | 12 |

| 78 | Olijhoek et al. (2016) | Dairy | NO3- | Chamber | 4 |

| 79 | de Oliveira et al. (2007) | Beef | Phytochemicals | SF6 | 8 |

| 80 | Patra et al. (2011) | Sheep | Phytochemicals | Chamber | 4 |

| 81 | Pen et al. (2007) | Sheep | Phytochemicals | Chamber | 4 |

| 82 | Rebelo et al. (2009) | Beef | NO3- | SF6 | 10 |

| 83 | Reynolds et al. (2014) | Dairy | 3-NOP | GreenFeed | 6 |

| 84 | Romero-Perez et al. (2014) | Beef | 3-NOP | Chamber | 8 |

| 85 | Romero-Perez et al. (2015) | Beef | 3-NOP | Chamber | 8 |

| 86 | Roque et al. (2019) | Dairy | Seaweed | GreenFeed | 12 |

| 87 | Rossi et al. (2017) | Beef | Oil | SF6 | 7 |

| 88 | Santoso et al. (2004) | Sheep | Phytochemicals | Chamber | 4 |

| 89 | Silva et al. (2018) | Beef | Oil | SF6 | 6 |

| 90 | Soltan et al. (2013) | Sheep | Phytochemicals | Chamber | 6 |

| 91 | Staerfl et al. (2012) | Beef | Phytochemicals, protozoa control | Chamber | 6 |

| 92 | Sun et al. (2017) | Beef | NO3- | Chamber | 4 |

| 93 | Tiemann et al. (2008) | Sheep | Phytochemicals | Chamber | 6 |

| 94 | Troy et al. (2015) | Beef | Oil, NO3- | Chamber | 6 |

| 95 | Van Wesemael et al. (2019) | Dairy | 3-NOP | GreenFeed | 10 |

| 96 | van Zijderveld et al. (2010) | Sheep | NO3- | Chamber | 5 |

| 97 | van Zijderveld et al. (2011a) | Dairy | Oil, Phytochemicals | Chamber | 10 |

| 98 | van Zijderveld et al. (2011b) | Dairy | NO3- | Chamber | 5 |

| 99 | Velazco et al. (2014) | Beef | NO3- | GreenFeed | 10 |

| 100 | Veneman et al. (2015) | Dairy | oil, NO3- | Chamber | 6 |

| 101 | Villar et al. (2019) | Beef | oil, NO3- | Chamber | 4 |

| 102 | Vyas et al. (2016) | Beef | 3-NOP | Chamber | 5 |

| 103 | Vyas et al. (2018a) | Beef | 3-NOP | Chamber | 5 |

| 104 | Vyas et al. (2018b) | Beef | 3-NOP, ionophores | Chamber | 5 |

| 105 | Waghorn et al. (2008) | Dairy | Ionophores | SF6 | 16 |

| 106 | Wang et al. (2009) | Sheep | Phytochemicals | Chamber | 4 |

| 107 | Yang et al. (2017) | Beef | Phytochemicals, protozoa control | Chamber | 4 |

| 108 | Zhou et al. (2011) | Sheep | Phytochemicals, protozoa control | Chamber | 3 |

n = total number of animals.

The investigated factors were body weight (BW; kg), dry matter (DM; kg/d) intake, liveweight gain (g/d), milk production (kg/d), diet chemical composition (crude protein, CP; neutral detergent fiber, NDF; fat; and non-fiber carbohydrate, NFC; %DM), and digestibility of nutrients (DM, CP, fat and NDF; %). Methane emissions were reported as CH4 production (g CH4/animal per d), CH4 yield (MY; g CH4/kg DMI) and CH4 emission intensity (MI; g CH4/kg animal product, typically milk or liveweight gain).

2.2. Inclusion criteria

For inclusion in the meta-analysis, studies were required to have MY (g/kg DMI) measured, as well as data reported on composition of diets and intake. Besides these, other variables required in the dataset were digestibility, animal performance and rumen fermentation indicators (pH, molar proportion of volatile fatty acids, and protozoa count). Overall, 108 publications met these requirements and were included in the analysis (Table 1).

2.3. Statistical analysis

The meta-analysis was performed using the MIXED procedure of SAS (version 9.4, SAS/STAT, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC), considering study as a random effect. Furthermore, to account for variations in precision across studies, the inverse of the squared standard error of the mean (SEM) (Wang and Bushman, 1999) of MY was used as a factor in the WEIGHT statement of the model (St-Pierre, 2001). The slopes and intercepts by study were included as random effects, specifying an unstructured variance-covariance matrix for the intercepts and slopes (St-Pierre, 2001). Differences between means were determined using the P-DIFF option of the LSMEANS statement, which is based on Fisher's F-protected least significant difference test. Significant difference was declared at P < 0.05.

3. Results and discussion

An appraisal of the quantitative potential enteric CH4 abatement of each considered dietary strategy is given below and summarized in Fig. 1. Among the strategies assessed, one may note that nutritional management can alter MPR and MY by multiple means that directly target methanogens or affect methanogenesis by altering residual hydrogen availability in the rumen.

Fig. 1.

Forest plot depicting the standardized mean effect of the estimated ratio of methane (CH4) yields for mitigation strategy vs. control emissions (mean CH4 emission in treatment with mitigation strategy divided by mean CH4 emission in control) and the 95% confidence interval (95% CI). Values below 1.0 (vertical line) indicate that the mitigation strategy yields a reduction in CH4 emissions.

3.1. Oils

Among the several dietary strategies specifically developed to mitigate enteric CH4 production, oil inclusion in the diet is the one with most papers published in the last 20 years, that were included in the meta-analysis (n = 35; Table 1). Our analysis revealed that the MY mitigation ranges from 12% to 20% (95% CI of the mean effect size; mean reduction of 15%). For every increase of 1% of oil (10 g/kg DM) from 2.85% to 6.20% inclusion, the MY was reduced by 1.02 ± 0.113 g CH4/kg DMI or 4.37% (P < 0.01; RMSE = 4.56). A previous meta-analysis (of 17 studies) examined the reduction in MY in response to oil in the diet and reported that for each 1% oil added to the diet MY was reduced by 5.6% (Beauchemin et al., 2007).

Oils (i.e., polyunsaturated fatty acids and the medium-chain saturated fatty acids) have been previously recognised to suppress CH4 production in ruminants (Blaxter and Czerkawski, 1966). For instance, adding oil to the ruminant diet reduces H2 producers (i.e., protozoa; Mao et al., 2010, Guyader et al., 2015a, Guyader et al., 2015b), as well as methanogen populations (Mao et al., 2010), and may act as a [H+] acceptor through fatty acid biohydrogenation, although the effect is small (Ungerfeld, 2015). Among the papers included, only two (Johnson et al., 2002, Silva et al., 2018) out of 35 showed that adding oil to the diet of dairy cattle, beef cattle, or sheep did not affect enteric CH4 production.

Oil addition within the range of the studies included reduced DMI by 1.24% to 6.17% (Fig. 2A), and reduced NDF digestibility by 6.30% to 13.0% (Fig. 2B). No effect of oil on growth rate was detected using the present database, whereas oil addition decreased milk production by 1.17% to 13.7% (95% CI). The extent of the CH4 mitigation by dietary oil may vary with basal diet. Oil can be added to a low-fibre diet without impairing fibre digestibility, but negative effects on DMI, fibre digestibility, as well as animal performance, have been reported from adding oil to ruminants fed high-fibre diets (Machmüller et al., 2001; Machmuller et al., 2003; Benchaar et al., 2015; Beauchemin and McGinn, 2006; Hollmann et al., 2012, Troy et al., 2015). Therefore, the risk of adverse effects on fibre digestibility could restrict the use of oils as a mitigation strategy for grazing livestock.

Fig. 2.

Mean effect of diets containing oil on dry matter intake (DMI; A), neutral detergent fibre digestibility (NDFd; B) and methane (CH4) intensity (g CH4/kg animal product; C), expressed relative to control diets.

A reduction in MI (g CH4/kg of milk or weight gain) from 14.4% to 21.5% (P < 0.01; Fig. 2C) was found. Supplementation with unsaturated fatty acid rich-oils may influence the biohydrogenation, yielding the production of trans-10 18:1 fatty acid, which may result in a greater concentration of anti-lypogenic conjugated linoleic acid (trans-10, cis 12) production in the mammary gland (Odongo et al., 2007), and therefore may depress milk production (Baumgard et al., 2002). Moreover, the practicality of oil supplementation in the diet in a farm setting should be evaluated considering its benefits in CH4 mitigation, as well as effects on animal performance and cost of feeding. Oil as a mitigation strategy can readily be applied to feedlot and dairy systems. The main barriers to adoption in grazing systems relate to reduction in fibre digestibility and logistics of delivery in extensive rangelands.

3.2. Seaweeds

In vivo animal trials testing seaweeds as a mitigation option have only recently been published. One study in sheep (Li et al., 2018), one in dairy cattle (Roque et al., 2019) and one in feedlot cattle (Kinley et al., 2020) are available, showing a dose dependent MY reduction from 30.0% up to 69.0% (95% CI; P < 0.01; n = 3; mean reduction of 49.0%), with Asparagopsis inclusion from 0.5% to 3.0%. Li et al. (2018) revealed reduction of 3.50 g CH4/kg DMI (i.e., or 23.3% CH4 mitigation) for every gram of Asparagopsis taxiformis intake, with no effect on DMI or blood chemistry and pathology, but with some effect on rumen fermentation (Li et al., 2018), in sheep. Roque et al., 2019 reported 38% DMI reduction and reduced milk production when Asparagopsis was fed to dairy cows at 1% of DM.

Seaweeds are macroalgae, complex and diverse multicellular organisms that can grow in both marine and fresh water environments (van der Spiegel et al., 2013). The term “seaweed” has no taxonomic importance but is commonly used to refer to the marine algae (Makkar et al., 2016). Based on the pigment involved in their photosynthetic process, seaweeds can be categorised as red algae (Rhodophyceae), brown algae (Phaeophyceae), and green algae (Chlorophyceae) (Chapman and Chapman, 1980). There are more than 13,000 species of macroalgae (Huisman et al., 1998) and several species of macroalgae have been proposed as a novel ingredient in ruminant diets (van der Spiegel et al., 2013; Halmemies-Beauchet-Filleau et al., 2018). Seaweeds vary in chemical composition (Machado et al., 2014; Makkar et al., 2016), digestibility (i.e., 15% to 94% as reviewed by Makkar et al., 2016) and show a wide diversity and concentration of secondary metabolites (Carroll et al., 2019), including those by which CH4 mitigation is achieved (Dubois et al., 2013; Machado et al., 2014; Kinley and Fredeen, 2015).

Previous studies have identified that the red macroalgae A. taxiformis has a high efficacy in CH4 abatement in vitro (Kinley and Fredeen, 2015; Machado et al., 2016; Machado et al., 2018) and in vivo (Li et al., 2018) due to its high content of bromoform, a halogenated CH4 analogue (Lanigan, 1972). Halogenated CH4 analogues inhibit enzymatic activity of the methyltransferase enzyme by reacting with the reduced vitamin B12 cofactor required in one of the final steps of CH4 formation, decreasing the cobamide-dependent pathway (Wood et al., 1968).

A previous study reported moderate potential of seaweed to be market-ready as a ruminant feed within 2 to 3 years (Halmemies-Beauchet-Filleau et al., 2018) and preparations are well underway for marketing of a commercial product in Australia. The biochemical profile varies between species of seaweeds (Machado et al., 2014; Carroll et al., 2019), and it seems that Asparagopsis is the most effective macroalgae for CH4 mitigation. However, the effect of feeding macroalgae to ruminants on diet digestibility, animal performance and health, together with CH4 abatement are yet to be extensively addressed using in vivo trials. Recently, studies reported residue in the milk (increased iodine and bromide concentrations) as a result of feeding Asparagopsis to dairy cattle (Stefenoni et al., 2021), thus, establishing the recommended concentration of Asparagopsis in the diet is necessary to enable its safe use as a feed additive.

Moreover, the mitigation effect of seaweed appears to vary among its species in vitro, and is influenced by basal diet (Machado et al., 2014, 2016; Maia et al., 2016), thus future in vivo studies should focus on the influence of basal diet on the seaweed mitigation effect. The animal performance response in a pasture-based setting is yet to be defined, as well as delivery method. Additionally, lifecycle assessment will be important, to quantify the net climate change effects of this strategy, including the seaweed production process. Among caveats to tackle before the adoption of seaweed as a mitigation strategy are the concerns that high harvesting rates in the wild may disrupt the equilibrium of coastal ecosystems (Makkar et al., 2016), and that cultivation of seaweeds may release bromoform, an ozone-depleting substance (Carpenter and Liss, 2000; Quack and Wallace, 2003).

3.3. Nitrate

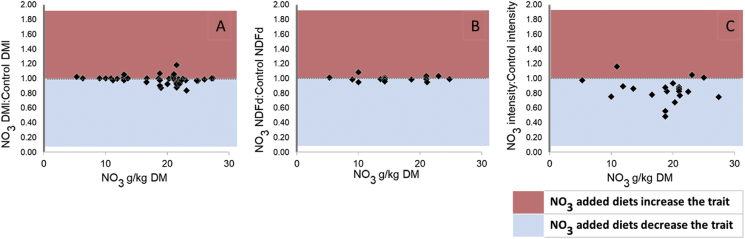

Our meta-analysis revealed that NO3- supplementation decreased MY by 15.7% on average, compared with a control diet (16.1 ± 0.855 g vs. 19.1 ± 0.853 CH4/kg DMI; P < 0.01; n = 25) in ruminants. Dietary NO3- inclusion from 17.2 to 22.1 g/kg DM (95% CI) led to MY reduction from 10.0% to 22.1% (95% CI; P < 0.05; n = 25). Unlike oils, NO3- supplementation does not impair DMI (P = 0.86; n = 25; Fig. 3A) or fibre digestibility (i.e., NDF digestibility; P = 0.86; n = 12; Fig. 3B), which is a beneficial outcome for grazing systems. Moreover, dietary NO3- supplies non-protein nitrogen to the rumen biota, reducing the need for other dietary non-protein nitrogen sources (Hulshof et al., 2012; Li et al., 2012; Villar et al., 2020). The overall reduction in MI (g CH4/kg of milk or weight gain) from NO3- inclusion ranged from 10.7% to 18.7% (P < 0.01; n = 11, Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

Mean effect of the estimated ratio of diets containing nitrate (NO3) and control diets in dry matter intake (DMI; A), neutral detergent fibre digestibility (NDFd; B) and methane (CH4) intensity (g/kg animal product; C).

The mechanism by which NO3- may lower ruminal CH4 production is through competition with methanogenesis for reducing equivalents. Because NO3- has a higher affinity for H2 than does CO2 in the rumen (Jones, 1972; Latham et al., 2016), CH4 production is reduced by feeding NO3- to ruminants. In the rumen, NO3- is initially reduced to NO2- (nitrite) and then to NH3, decreasing the availability of H2 for methanogens (Lewis, 1951; Nolan et al., 2016).

Since 2015, the Australian Emissions Reduction Fund has included a method through which carbon credits can be generated for feeding of NO3- to grazing ruminants (DoE, 2015). The major limitation of feeding NO3- to ruminants is the possibility of accumulation and absorption of intermediates of NO3- reduction (i.e., NO2- into the bloodstream). Besides being a precursor to carcinogenic compounds, NO2- can impair the capacity of blood to transport oxygen to an animal's tissues due to methaemoglobinaemia (Lewis, 1951; Sindelar and Milkowski, 2012; Bedale et al., 2016). In most studies used in the present analysis, blood methaemoglobin concentrations in nitrate-supplemented animals were higher than non-supplemented ones (Velazco et al., 2014; Guyader et al., 2016; Rebelo et al., 2019). None of the included studies that measured blood methaemoglobin levels observed clinical symptoms of methaemoglobinaemia, i.e., cyanosis and hypoxia that may arise at methaemoglobin >20% of total haemoglobin (Mensinga et al., 2003).

In this regard, management and nutritional strategies to reduce the risk of NO2- poisoning may be used, including adapting animals to NO3-, i.e., microbial acclimation (Lee and Beauchemin, 2014; Nolan et al., 2016), slowing the rate of NO3- reduction reaction in the rumen (e.g., by encapsulating in lipid; de Raphelis-Soissan et al., 2016), as well as combining different mitigation strategies (e.g., NO3- + oil; Nolan et al., 2016, Lee et al., 2017; Villar et al., 2019), so less NO3- is required in the diet. Evaluating the combined effect of using nitrate and an oil source for CH4 mitigation, the change in MY varied from 38.6% MY reduction up to 3.5% MY increase; (95% CI; P < 0.05; n = 4). Although these results were based on only four papers that evaluated the interaction of oil and NO3-, it seems that the combination of NO3- supplementation with oil would reduce the likelihood of nitrate poisoning.

3.4. Ionophores

The present study revealed that including an ionophore (monensin was used in the majority of studies) in cattle diets reduced MY by only 4% (95% CI from 0.5% to 7.4%; P = 0.05; n = 10; Fig. 1). Moreover, the use of ionophores as a mitigation strategy is limited to the period prior to microbiome adaptation. The current study showed only a modest MI reduction (g/CH4 per kg liveweight gain: 95% CI from 0% to 14.7%; P = 0.04; n = 5). Ionophores affect ammonia production, changing the fermentation dynamics towards improving energetics and N use in the rumen, as well as controlling acidosis. Ionophores are used mainly in feedlots and dairy herds (i.e., cattle fed high grain diets), and CH4 mitigation appears to be only a small co-benefit of the use of ionophores.

Ionophores are compounds of diverse chemical structures that are able to anchor to the lipid bilayer of cell membranes of organisms and translocate protons (H+) and metal ions through the membrane as futile ion fluxes leading to eventual death of the microbial cell (i.e., gram + bacteria and protozoa) (Russell and Strobel, 1989; Chow et al., 1994). Typically, this shifts the microbial population toward gram-negative bacteria that are less sensitive to ionophores, at the expense of H+-, ammonia-, and lactate-producing organisms, resulting in higher propionate production, less CH4, greater protein availability and higher ruminal pH (Russell and Houlihan, 2003).

Ionophores have been commonly used as a performance enhancer in ruminants, for 4 decades. Several ionophores are registered and approved for use as feed additives (e.g., monensin, lasalocid, narasin, laidlomycin), but this varies between countries. Monensin, the most widely used ionophore in ruminant nutrition, is produced by Streptomyces spp. Over time, rumen microbes adapt, reducing the ionophore response, including the CH4 mitigation (Callaway et al., 2003). Rotating ionophores and antibiotics (daily, weekly or biweekly) may improve the longevity of the effect of ionophores on feed efficiency (Guan et al., 2006; Crossland et al., 2017). As ruminal bacteria become resistant to ionophores, one may argue that ionophore resistance poses a public health threat, as genes linked to ionophore resistance in ruminal bacteria have not yet been identified.

3.5. Protozoa population control

The meta-analysis found that when a protozoa population-controlling additive was used, the protozoa population reduced by 23% (95% CI = 12% to 35%; P < 0.01; n = 22) but rumen MY diminished by only 2% on average (95% CI = −0.16% to 14.0%; P = 0.03; n = 22; Fig. 1), noting wide variation inherent to diet. The reduction in MY may be due to a reduced methanogen population, an altered pattern of volatile fatty acid production and hydrogen availability; and greater dry matter digestion in the rumen. Our results did not show reduction in DM digestibility (P = 0.91) or NDF digestibility (P = 0.87). The decline in methanogenesis associated with removal of protozoa is greatest on high concentrate diets and this is in keeping with protozoa being relatively more important sources of hydrogen on starchy diets, as many starch-fermenting bacteria do not produce H2.

Some methanogens in the rumen exist as endo- and ecto-symbionts with ciliate protozoa (Finlay et al., 1994; Tokura et al., 1997) and such symbionts may account for up to 37% of the rumen methanogens (Finlay et al., 1994). Although protozoa are a significant proportion of the biomass in the rumen ecosystem, they are not essential (Newbold et al., 2015). On the contrary, some co-benefits of rumen defaunation (removing protozoa) have been reported, such as increases in growth rate and live weight gain of ruminants (Eugène et al., 2004, Newbold et al., 2015) especially when the feed is deficient in protein relative to energy content. In addition, rumen protozoa are significant H2 producers, due to their preferred production of acetate and butyrate rather than propionate.

In brief, one may use physical and chemical techniques to achieve defaunation of the rumen: the most commonly used techniques are the isolation of animals from their mothers at birth, and the use of surfactants and other chemicals (e.g., sodium lauryl sulfate, alkanes, synperonic NP9, calcium peroxide, copper sulfate), as well as emptying and washing the rumen (Hegarty et al., 2008; Newbold et al., 2015). Moreover, some feed additives used to mitigate CH4 or as efficiency enhancers may control the protozoan population including ionophores, oil, and NO3- supplementation. It is noteworthy that none of the available techniques is considered practical and/or efficient for commercial application to date.

3.6. Phytochemicals

For the purpose of the present study, a wide array of heterogeneous plant secondary compounds with antimethanogenic properties were grouped as phytochemicals (Patra and Saxena, 2010) including tannin-rich feeds, essential oils, and saponins but excluding macroalgal bromoform.

Our meta-analysis indicated no effect of phytochemical inclusion on DMI of dairy, beef cattle, and sheep (mean effect of 1.00 ± 0.00386; 95% CI 0.992 to 1.01; P = 0.81; n = 33; Fig. 4). Among studies included in the analysis, 24% trialed saponins, 50% used tannins and 21% fed essential oils, while 5% of these studies examined other phytochemicals (e.g., flavonoids). The estimated mean reduction in MY through phytochemical supplementation was 10% compared with the control diet (16.7 ± 1.11 g vs. 18.6 ± 1.12 CH4/kg DMI; P < 0.01; n = 33), with tannins and saponins having the greatest effect (Fig. 4). The observed mean reduction in MY due to phytochemical supplementation ranged from 8% to 14% (Fig.1; 95% CI; P < 0.01; n = 33). Phytochemical inclusion in the diet of ruminants affected fibre digestibility (mean reduction in NDF digestibility of 4.69%; 95% CI 0.86 – 8.56; P = 0.02; n = 21), without affecting total tract DM digestibility (mean effect 95% CI 0.97 – 1.01; P = 0.97; n = 21). Overall, phytochemical supplementation tended to reduce CH4 intensity in ruminant animals (mean effect 0.922 ± 0.0351; 95% CI 0.83 to 1.00; P = 0.08; n = 21).

Fig. 4.

Mean effect of the estimated ratio of diets essential oils (diamond), saponins (triangle), and tannins (circle) and control diets in methane (CH4) yield, dry matter intake (DMI), NDF (neutral detergent fibre) digestibility and DM (dry matter) digestibility.

When using phytochemicals as feed additives, one should pay close attention to the dose and purity, as they may possess anti-nutritional characteristics at higher concentrations. The aim is to find the equilibrium between the beneficial CH4 abatement and optimum nutrient utilisation. This balance is particularly complex to attain, as the composition and quantity of phytochemicals varies widely within natural sources (e.g., legumes), even when fed as extracts. More than 200,000 plant secondary compounds have been identified (Hartmann, 2007), and some have antimethanogenic proprieties.

Saponins are high molecular-weight glycosides that occur in a variety of plants, with triterpene saponins (i.e., saccharide chain units linked to a triterpene) more abundant in nature than steroidal saponins (Hostettmann and Marston, 2005). The CH4-suppressing traits of saponin-rich plants are principally related to the inhibition of rumen ciliate protozoa, which may enhance efficiency of synthesis of microbial protein (Patra and Saxena, 2009). Similar beneficial effects on N and energy ruminal metabolism have been observed when feeding tannins to ruminants (Norris et al., 2020). Tannins are high molecular weight polyphenolic compounds soluble in water and have capacity to interact with proteins (and carbohydrates) due to the presence of a large number of phenolic hydroxyl groups forming complexes (Patra and Saxena, 2010). They exist as hydrolysable tannins (HT) and condensed tannins (CT); both have antimethanogenic effects, however CT are more commonly used as a feed additive because HT represent a high risk of toxicity to the animal (Field and Lettinga, 1987; McSweeney et al., 2001).

Tannin-rich plants include legumes that may be used to improve pasture productivity as well as nitrogen level in the diet. The tropical legumes Desmanthus and Leucaena leucocephala have significant antimethanogenic properties, and are considered a promising approach for mitigation of enteric CH4 in beef production in the northern Australian rangelands (Suybeng et al., 2019; Tomkins et al., 2019; Vandermeulen et al., 2018). Leucaena is not currently recommended in southern Australia due to its propensity to become a weed.

Essential oils are not based on long chain fatty acids but are bio-active molecules with antimicrobial properties that can directly inhibit methanogens and hydrogen-producing microorganisms. They include garlic oil, thymol, cinnamaldehyde, peppermint, menthol and eucalyptus oils, as well as commercial blends. The type of essential oil determines the effect on CH4 production. It is important to consider the potential anti-nutritional effect of essential oils and the adaptation of rumen microbes to essential oils, the change in flavour of animal products due to presence of residues in meat and milk, as well as acceptability by the animals, which could affect DMI (Rae, 1999; Calsamiglia et al., 2007).

Due to high variation in the concentrations and types of antimethanogenic compounds between plant species, as well as spatial and temporal inconsistency, it is not possible to provide generic recommendations about the dietary inclusion of phytochemicals for CH4 mitigation.

3.7. 3-Nitrooxypropanol (3-NOP)

Reviewing previous studies, the in-feed doses of 3-NOP fed to ruminants ranged from 40 to 340 mg 3-NOP/kg DM (64.2 to 122 mg 3-NOP/kg DM; 95% CI) and responses are highly dose dependent. From our meta-analysis, 3-NOP supplementation decreased ruminant CH4 emission by 23.3% compared with a control diet (15.1 ± 0.995 g vs. 19.7 ± 1.11 CH4/kg DMI; P < 0.01; n = 14). The mean reduction in the MY ranged from 18 to 39% (95% CI; P < 0.01; n = 14; Fig. 1). All individual studies used in the meta-analysis noted the efficacy of 3-NOP in lowering enteric CH4 emissions (Table 1).

Previously, CH4 abatement achieved with dietary 3-NOP in ruminants was associated with a decrease in DMI (Romero-Perez et al., 2014; Vyas et al., 2016), and this was borne out in the current analysis where 3-NOP supplementation reduced DMI up to 4.5% (P = 0.02; Fig. 5A; n = 14). The reduction in DMI itself is not a concern if it results in the same liveweight gain by the animal, which would indicate improved feed use efficiency. In the present study, the 3-NOP supplementation did not alter fibre digestibility (i.e., NDF; P = 0.25; Fig. 5B; n = 5). The reduction in MY with 3-NOP ranged from 6.5% to 38% in dairy cattle (mean of 22.2%; P < 0.01; n = 7) and from 1.5% to 59% in beef cattle (mean of 30.0%; P < 0.01; n = 7). In contrast, previous studies suggested stronger antimethanogenic effects of 3-NOP in dairy cattle than in beef cattle (Dijkstra et al., 2018). Additionally, 3-NOP has a greater CH4 suppressing effect in high-forage than high-grain feedlot diets (Kim et al., 2019). One may expect a larger variation within grazing beef cattle compared to dairy production systems, because of the greater complexity involved in delivering any feed additive to cattle in a grazing situation. The overall reduction in CH4 intensity (g CH4/kg of milk or weight gain) from 3-NOP ranged from 13.2% to 39.9% (P < 0.01; Fig. 5C).

Fig. 5.

Mean effect of the estimated ratio of diets containing 3-nitrooxypropanol (3-NOP) and control diets in dry matter intake (DMI; A), neutral detergent fibre digestibility (NDFd; B) and methane (CH4) intensity (C).

The commercially developed compound 3-NOP provides a novel and promising feed additive to mitigate CH4. It is a structural analogue of the nickel enzyme methyl CoM reductase produced by the methanogenic archaea, thus it inhibits the last step of CH4 formation in the rumen (Duin et al., 2016). Previous studies have shown that 3-NOP is a potent CH4 suppressant, effective in a wide range of diet types, exhibiting no DMI nor digestibility reduction in beef or dairy cattle (Romero-Perez et al., 2014; Haisan et al., 2017; Jayanegara et al., 2017). Research has found that 3-NOP is metabolised rapidly, and does not accumulate in the mammal's bloodstream (Thiel et al., 2019). Moreover, 3-NOP and its metabolites were not found to have mutagenic or genotoxic potential (Thiel et al., 2019b). Thus, 3-NOP does not seem to represent a food security threat or risk to animal health.

Thus, 3-NOP may offer a reliable and effective strategy for CH4 abatement in beef, sheep and dairy cattle, yet as a relatively novel feed additive, there may be resistance to adoption. The magnitude of the mitigation differ between ruminant types. Optimal doses of 3-NOP are yet to be defined, to support registration as a permitted feed additive, enabling the use of 3-NOP in the meat, wool and dairy industries.

3.8. Other CH4 mitigation strategies

Among the reviewed CH4 reduction strategies, it was found that comprehensive data regarding the use of bacteriocins (for review: Garsa et al., 2019), organic acids and prebiotics (e.g., acetogens, yeasts) (Martin et al., 2010; Patra, 2016) is too sparse to support adoption in the next 10 years. Moreover, these technologies generally yield modest results in CH4 abatement, thus they were not included in the present meta-analysis.

4. Conclusions

This meta-analysis assessed dietary strategies for CH4 mitigation in ruminant production systems. Seaweed, 3-NOP and NO3- are the most effective feed additives for abatement of ruminant CH4 emissions, and show promise as mitigation strategies available to the livestock sector within the short term.

Further investigation is required to assess combinations of different strategies for CH4 mitigation using a systematic approach, and to devise delivery method to enable their use in grazing systems.

Author contributions

Amelia Katiane de Almeida: Formal analysis, Data Curation, Conceptualization, Interpretation of Results, Writing - Original Draft. Roger Hegarty: Interpretation of Results, Writing - Original Draft, Review & Editing. Annette Cowie: Conceptualization, Interpretation of Results, Writing - Review & Editing.

Conflict of interest

We declare that we have no financial and personal relationships with other people or organizations that can inappropriately influence our work, and there is no professional or other personal interest of any nature or kind in any product, service and/or company that could be construed as influencing the content of this paper.

Acknowledgment

This study was funded by the NSW Climate Change Fund through the NSW Primary Industries Climate Change Research Strategy.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chinese Association of Animal Science and Veterinary Medicine.

References

- Alemu A.W., Romero-Perez A., Araujo R.C., Beauchemin K.A. Effect of encapsulated nitrate and microencapsulated blend of essential oils on growth performance and methane emissions from beef steers fed backgrounding diets. Animals. 2019;9(1):21. doi: 10.3390/ani9010021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asizua D., Mpairwe D., Kabi F., Mutetikka D., Kamatara K., Hvelplund T., Weisbjerg M.R., Mugasi S., Madsen J. Growth performance, carcass and non-carcass characteristics of Mubende and Mubende× Boer crossbred goats under different feeding regimes. Livest Sci. 2014;169:63–70. [Google Scholar]

- Baumgard L.H., Matitashvili E., Corl B.A., Dwyer D.A., Bauman D.E. trans-10, cis-12 conjugated linoleic acid decreases lipogenic rates and expression of genes involved in milk lipid synthesis in dairy Cows1. J Dairy Sci. 2002;85:2155–2163. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(02)74294-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauchemin K.A., McGinn S.M. Methane emissions from beef cattle: effects of fumaric acid, essential oil, and canola oil1. J Anim Sci. 2006;84:1489–1496. doi: 10.2527/2006.8461489x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauchemin K.A., McGinn S.M., Petit H.V. Methane abatement strategies for cattle: lipid supplementation of diets. Can J Anim Sci. 2007;87:431–440. [Google Scholar]

- Beauchemin K.A., McGinn S.M., Benchaar C., Holtshausen L. Crushed sunflower, flax, or canola seeds in lactating dairy cow diets: effects on methane production, rumen fermentation, and milk production. J Dairy Sci. 2009;92:2118–2127. doi: 10.3168/jds.2008-1903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedale W., Sindelar J.J., Milkowski A.L. Dietary nitrate and nitrite: benefits, risks, and evolving perceptions. Meat Sci. 2016;120:85–92. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2016.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benchaar C. Diet supplementation with cinnamon oil, cinnamaldehyde, or monensin does not reduce enteric methane production of dairy cows. Animal. 2016;10:418–425. doi: 10.1017/S175173111500230X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benchaar C., Hassanat F., Martineau R., Gervais R. Linseed oil supplementation to dairy cows fed diets based on red clover silage or corn silage: effects on methane production, rumen fermentation, nutrient digestibility, N balance, and milk production. J Dairy Sci. 2015;98:7993–8008. doi: 10.3168/jds.2015-9398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird S.H., Hegarty R.S., Woodgate R. Persistence of defaunation effects on digestion and methane production in ewes. Aust J Exp Agric. 2008;48 [Google Scholar]

- Blaxter K.L., Czerkawski J. Modification of the methane production of the sheep by supplementation of ITS diet. J Sci Food Agric. 1966;17:417–421. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.2740170907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano M., Wilkes M.J., Pitchford W.S., Lee S.J., Hynd P.I. Effect of ensiled crimped grape marc on energy intake, performance and gas emissions of beef cattle. Anim Feed Sci Technol. 2019;247:166–172. [Google Scholar]

- Callaway T., Edrington T., Rychlik J., Genovese K., Poole T., Jung Y.S., Bischoff K., Anderson R., Nisbet D.J. 2003. Ionophores: their use as ruminant growth promotants and impact on food safety. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calsamiglia S., Busquet M., Cardozo P.W., Castillejos L., Ferret A. Invited review: essential oils as modifiers of rumen microbial fermentation. J Dairy Sci. 2007;90:2580–2595. doi: 10.3168/jds.2006-644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter L., Liss P. On temperate sources of bromoform and other reactive organic bromine gases. J Geophys Res: Atmospheres. 2000;105:20539–20547. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll A.R., Copp B.R., Davis R.A., Keyzers R.A., Prinsep M.R. 2019. Marine natural products. Natural product reports. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carulla J., Kreuzer M., Machmüller A., Hess H. Supplementation of Acacia mearnsii tannins decreases methanogenesis and urinary nitrogen in forage-fed sheep. Aust J Exp Agric. 2005;56:961–970. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho IPCd, Fiorentini G., Berndt A., Castagnino PdS., Messana J.D., Frighetto R.T.S., Reis R.A., Berchielli T.T. Performance and methane emissions of Nellore steers grazing tropical pasture supplemented with lipid sources. Rev Bras Zootec. 2016;45:760–767. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman V.J., Chapman D.J. Chapman and Hall. 1980. Seaweeds and their Uses (3rd ed.) [Google Scholar]

- Chow J.M., Van Kessel J.A.S., Russell J.B. Binding of radiolabeled monensin and lasalocid to ruminal microorganisms and feed. J Anim Sci. 1994;72:1630–1635. doi: 10.2527/1994.7261630x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung Y.-H., Mc Geough E., Acharya S., McAllister T., McGinn S., Harstad O., Beauchemin K. Enteric methane emission, diet digestibility, and nitrogen excretion from beef heifers fed sainfoin or alfalfa. J Anim Sci. 2013;91:4861–4874. doi: 10.2527/jas.2013-6498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooprider K.L., Mitloehner F.M., Famula T.R., Kebreab E., Zhao Y., Van Eenennaam A.L. Feedlot efficiency implications on greenhouse gas emissions and sustainability. J Anim Sci. 2011;89:2643–2656. doi: 10.2527/jas.2010-3539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosgrove G.P., Waghorn G.C., Anderson C.B., Peters J.S., Smith A., Molano G., Deighton M. The effect of oils fed to sheep on methane production and digestion of ryegrass pasture. Aust J Exp Agric. 2008;48 [Google Scholar]

- Cottle D.J., Nolan J.V., Wiedemann S.G. Ruminant enteric methane mitigation: a review. Anim Prod Sci. 2011;51:491–514. [Google Scholar]

- Crossland W.L., Tedeschi L.O., Callaway T.R., Miller M.D., Smith W.B., Cravey M. Effects of rotating antibiotic and ionophore feed additives on volatile fatty acid production, potential for methane production, and microbial populations of steers consuming a moderate-forage diet. J Anim Sci. 2017;95:4554–4567. doi: 10.2527/jas2017.1665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Oliveira S.G., Berchielli T.T., Pedreira MdS., Primavesi O., Frighetto R., Lima M.A. Effect of tannin levels in sorghum silage and concentrate supplementation on apparent digestibility and methane emission in beef cattle. Anim Feed Sci Technol. 2007;135:236–248. [Google Scholar]

- de Raphelis-Soissan V., Nolan J.V., Newbold J., Godwin I., Hegarty R. Can adaptation to nitrate supplementation and provision of fermentable energy reduce nitrite accumulation in rumen contents in vitro? Anim Prod Sci. 2016;56:605–612. [Google Scholar]

- Dijkstra J., Bannink A., France J., Kebreab E., van Gastelen S. Short communication: antimethanogenic effects of 3-nitrooxypropanol depend on supplementation dose, dietary fiber content, and cattle type. J Dairy Sci. 2018;101:9041–9047. doi: 10.3168/jds.2018-14456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding X., Long R., Zhang Q., Huang X., Guo X., Mi J. Reducing methane emissions and the methanogen population in the rumen of Tibetan sheep by dietary supplementation with coconut oil. Trop Anim Health Prod. 2012;44:1541–1545. doi: 10.1007/s11250-012-0103-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois B., Tomkins N.W., Kinley R.D., Bai M., Seymour S., Paul N.A., de Nys R. Effect of tropical algae as additives on rumen in vitro gas production and fermentation characteristics. Am J Plant Sci. 2013;4:34–43. [Google Scholar]

- Duin E.C., Wagner T., Shima S., Prakash D., Cronin B., Yanez-Ruiz D.R. Mode of action uncovered for the specific reduction of methane emissions from ruminants by the small molecule 3-nitrooxypropanol. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:6172–6177. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1600298113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duthie C.A., Troy S.M., Hyslop J.J., Ross D.W., Roehe R., Rooke J.A. The effect of dietary addition of nitrate or increase in lipid concentrations, alone or in combination, on performance and methane emissions of beef cattle. Animal. 2018;12:280–287. doi: 10.1017/S175173111700146X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehhalt D., Prather M., Dentener F., Derwent R., Dlugokencky E. In: Climate Change 2001: The Scientific Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Third Assessment Report of the IPCC. Cambridge, United Kingdom. Houghton J.T., Ding Y., Griggs D.J., Noguer M., van der Linden P.J., Dai X., editors. Cambridge University Press; New York: 2001. Atmospheric Chemistry and Greenhouse Gases; pp. 239–287. [Google Scholar]

- El-Zaiat H., Araujo R., Soltan Y.A., Morsy A.S., Louvandini H., Pires A., Patino H.O., Corrêa P.S., Abdalla A.L. Encapsulated nitrate and cashew nut shell liquid on blood and rumen constituents, methane emission, and growth performance of lambs. J Anim Sci. 2014;92:2214–2224. doi: 10.2527/jas.2013-7084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eugène M., Archimède H., Sauvant D. Quantitative meta-analysis on the effects of defaunation of the rumen on growth, intake and digestion in ruminants. Livest Prod Sci. 2004;85:81–97. [Google Scholar]

- Field J.A., Lettinga G. The methanogenic toxicity and anaerobic degradability of a hydrolyzable tannin. Water Res. 1987;21:367–374. [Google Scholar]

- Finlay B.J., Esteban G., Clarke K.J., Williams A.G., Embley T.M., Hirt R.P. Some rumen ciliates have endosymbiotic methanogens. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1994;117:157–161. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1994.tb06758.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiorentini G., Carvalho I.P.C., Messana J.D., Castagnino P.S., Berndt A., Canesin R.C., Frighetto R.T.S., Berchielli T.T. Effect of lipid sources with different fatty acid profiles on the intake, performance, and methane emissions of feedlot Nellore steers. J Anim Sci. 2014;92:1613–1620. doi: 10.2527/jas.2013-6868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garsa A.K., Choudhury P.K., Puniya A.K., Dhewa T., Malik R.K., Tomar S.K. Bovicins: the bacteriocins of streptococci and their potential in methane mitigation. Probiotics Antimicrob Proteins. 2019;11:1403–1413. doi: 10.1007/s12602-018-9502-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grainger C., Auldist M.J., Clarke T., Beauchemin K.A., McGinn S.M., Hannah M.C., Eckard R.J., Lowe L.B. Use of monensin controlled-release capsules to reduce methane emissions and improve milk production of dairy cows offered pasture supplemented with grain. J Dairy Sci. 2008;91:1159–1165. doi: 10.3168/jds.2007-0319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grainger C., Clarke T., Auldist M., Beauchemin K., McGinn S., Waghorn G., Eckard R.J. Potential use of Acacia mearnsii condensed tannins to reduce methane emissions and nitrogen excretion from grazing dairy cows. Can J Anim Sci. 2009;89:241–251. [Google Scholar]

- Grainger C., Clarke T., Beauchemin K.A., McGinn S.M., Eckard R.J. Supplementation with whole cottonseed reduces methane emissions and can profitably increase milk production of dairy cows offered a forage and cereal grain diet. Aust J Exp Agric. 2008;48 [Google Scholar]

- Grainger C., Williams R., Eckard R.J., Hannah M.C. A high dose of monensin does not reduce methane emissions of dairy cows offered pasture supplemented with grain. J Dairy Sci. 2010;93:5300–5308. doi: 10.3168/jds.2010-3154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granja-Salcedo Y.T., Fernandes R.M., de Araujo R.C., Kishi L.T., Berchielli T.T., de Resende F.D., Berndt A., Siqueira G.R. Long-term encapsulated nitrate supplementation modulates rumen microbial diversity and rumen fermentation to reduce methane emission in grazing steers. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:614. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossi G., Goglio P., Vitali A., Williams A.G. Livestock and climate change: impact of livestock on climate and mitigation strategies. Animal Front. 2019;9:69–76. doi: 10.1093/af/vfy034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan H., Wittenberg K.M., Ominski K.H., Krause D.O. Efficacy of ionophores in cattle diets for mitigation of enteric methane. J Anim Sci. 2006;84:1896–1906. doi: 10.2527/jas.2005-652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyader J., Doreau M., Morgavi D.P., Gerard C., Loncke C., Martin C. Long-term effect of linseed plus nitrate fed to dairy cows on enteric methane emission and nitrate and nitrite residuals in milk. Animal. 2016;10:1173–1181. doi: 10.1017/S1751731115002852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyader J., Eugène M., Doreau M., Morgavi D.P., Gérard C., Loncke C., Martin C. Nitrate but not tea saponin feed additives decreased enteric methane emissions in nonlactating cows. J Anim Sci. 2015;93:5367–5377. doi: 10.2527/jas.2015-9367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyader J., Eugène M., Meunier B., Doreau M., Morgavi D.P., Silberberg M., Rochette Y., Gerard C., Loncke C., Martin C. Additive methane-mitigating effect between linseed oil and nitrate fed to cattle. J Anim Sci. 2015;93:3564–3577. doi: 10.2527/jas.2014-8196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haisan J., Sun Y., Guan L., Beauchemin K., Iwaasa A., Duval S., Barreda D., Oba M. The effects of feeding 3-nitrooxypropanol on methane emissions and productivity of Holstein cows in mid lactation. J Dairy Sci. 2014;97:3110–3119. doi: 10.3168/jds.2013-7834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haisan J., Sun Y., Guan L., Beauchemin K.A., Iwaasa A., Duval S., Kindermann M., Barreda D.R., Oba M. The effects of feeding 3-nitrooxypropanol at two doses on milk production, rumen fermentation, plasma metabolites, nutrient digestibility, and methane emissions in lactating Holstein cows. Anim Prod Sci. 2017;57:282–289. [Google Scholar]

- Halmemies-Beauchet-Filleau A., Rinne M., Lamminen M., Mapato C., Ampapon T., Wanapat M., Vanhatalo A. Alternative and novel feeds for ruminants: nutritive value, product quality and environmental aspects. Animal. 2018;12:s295–s309. doi: 10.1017/S1751731118002252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann T. From waste products to ecochemicals: fifty years research of plant secondary metabolism. Phytochemistry. 2007;68:2831–2846. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2007.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegarty R.S., Bird S.H., Vanselow B.A., Woodgate R. Effects of the absence of protozoa from birth or from weaning on the growth and methane production of lambs. Br J Nutr. 2008;100:1220–1227. doi: 10.1017/S0007114508981435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrero M., Henderson B., Havlík P., Thornton P.K., Conant R.T., Smith P., Wirsenius S., Hristov A.N., Gerber P., Gill M., Butterbach-Bahl K., Valin H., Garnett T., Stehfest E. Greenhouse gas mitigation potentials in the livestock sector. Nat Clim Change. 2016;6:452–461. [Google Scholar]

- Hess H.D., Beuret R.A., Lötscher M., Hindrichsen I.K., Machmüller A., Carulla J.E., Lascano C.E., Kreuzer M. Ruminal fermentation, methanogenesis and nitrogen utilization of sheep receiving tropical grass hay-concentrate diets offered with Sapindus saponaria fruits and Cratylia argentea foliage. Anim Sci. 2016;79:177–189. [Google Scholar]

- Hollmann M., Powers W.J., Fogiel A.C., Liesman J.S., Bello N.M., Beede D.K. Enteric methane emissions and lactational performance of Holstein cows fed different concentrations of coconut oil. J Dairy Sci. 2012;95:2602–2615. doi: 10.3168/jds.2011-4896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtshausen L., Chaves A.V., Beauchemin K.A., McGinn S.M., McAllister T.A., Odongo N.E., Cheeke P.R., Benchaar C. Feeding saponin-containing Yucca schidigera and Quillaja saponaria to decrease enteric methane production in dairy cows. J Dairy Sci. 2009;92:2809–2821. doi: 10.3168/jds.2008-1843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosoda K., Nishida T., Park W.-Y., Eruden B. Influence of Mentha× piperita L.(peppermint) supplementation on nutrient digestibility and energy metabolism in lactating dairy cows. AJAS (Asian-Australas J Anim Sci) 2005;18:1721–1726. [Google Scholar]

- Hostettmann K., Marston A. Cambridge University Press; 2005. Saponins. [Google Scholar]

- Hristov A.N., Lee C., Cassidy T., Heyler K., Tekippe J., Varga G., Corl B., Brandt R. Effect of Origanum vulgare L. leaves on rumen fermentation, production, and milk fatty acid composition in lactating dairy cows. J Dairy Sci. 2013;96:1189–1202. doi: 10.3168/jds.2012-5975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hristov A.N., Oh J., Giallongo F., Frederick T.W., Harper M.T., Weeks H.L., Branco A.F., Moate P.J., Deighton M.H., Williams S.R.O. An inhibitor persistently decreased enteric methane emission from dairy cows with no negative effect on milk production. Proc Natl Acad Sci Unit States Am. 2015;112:10663–10668. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1504124112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huisman J.M., Cowan R.A., Entwisle T.J. Botanica Marina. 1998. Biodiversity of Australian marine macroalgae — a progress report; p. 89. [Google Scholar]

- Hulshof R., Berndt A., Gerrits W., Dijkstra J., Van Zijderveld S., Newbold J., Perdok H. Dietary nitrate supplementation reduces methane emission in beef cattle fed sugarcane-based diets. J Anim Sci. 2012;90:2317–2323. doi: 10.2527/jas.2011-4209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hünerberg M., McGinn S.M., Beauchemin K.A., Okine E.K., Harstad O.M., McAllister T.A. Effect of dried distillers grains plus solubles on enteric methane emissions and nitrogen excretion from growing beef cattle. J Anim Sci. 2013;91:2846–2857. doi: 10.2527/jas.2012-5564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hünerberg M., McGinn S.M., Beauchemin K.A., Okine E.K., Harstad O.M., McAllister T.A. Effect of dried distillers' grains with solubles on enteric methane emissions and nitrogen excretion from finishing beef cattle. Can J Anim Sci. 2013;93:373–385. doi: 10.2527/jas.2012-5564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayanegara A., Sarwono K.A., Kondo M., Matsui H., Ridla M., Laconi E.B., Nahrowi Use of 3-nitrooxypropanol as feed additive for mitigating enteric methane emissions from ruminants: a meta-analysis. Ital J Anim Sci. 2017;17:650–656. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson K.A., Kincaid R.L., Westberg H.H., Gaskins C.T., Lamb B.K., Cronrath J.D. The effect of oilseeds in diets of lactating cows on milk production and methane emissions. J Dairy Sci. 2002;85:1509–1515. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(02)74220-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones G.A. Dissimilatory metabolism of nitrate by the rumen microbiota. Can J Microbiol. 1972;18:1783–1787. doi: 10.1139/m72-279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan E., Kenny D., Hawkins M., Malone R., Lovett D.K., O'Mara F.P. Effect of refined soy oil or whole soybeans on intake, methane output, and performance of young bulls. J Anim Sci. 2006;84:2418–2425. doi: 10.2527/jas.2005-354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan E., Lovett D.K., Hawkins M., Callan J.J., O'Mara F.P. The effect of varying levels of coconut oil on intake, digestibility and methane output from continental cross beef heifers. Anim Sci. 2007;82:859–865. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan E., Lovett D.K., Monahan F.J., Callan J., Flynn B., O'Mara F.P. Effect of refined coconut oil or copra meal on methane output and on intake and performance of beef heifers. J Anim Sci. 2006;84:162–170. doi: 10.2527/2006.841162x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jose Neto A., Messana J.D., Rossi L.G., Carvalho I.P.C., Berchielli T.T. Methane emissions from Nellore bulls on pasture fed two levels of starch-based supplement with or without a source of oil. Anim Prod Sci. 2019;59 [Google Scholar]

- Kim S.-H., Lee C., Pechtl H.A., Hettick J.M., Campler M.R., Pairis-Garcia M.D., Beauchemin K.A., Celi P., Duval S.M. Effects of 3-nitrooxypropanol on enteric methane production, rumen fermentation, and feeding behavior in beef cattle fed a high-forage or high-grain diet. J Anim Sci. 2019;97:2687–2699. doi: 10.1093/jas/skz140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinley R., Fredeen A. In vitro evaluation of feeding North Atlantic stormtoss seaweeds on ruminal digestion. J Appl Phycol. 2015;27:2387–2393. [Google Scholar]

- Kinley R.D., Martinez-Fernandez G., Matthews M.K., de Nys R., Magnusson M., Tomkins N.W. Mitigating the carbon footprint and improving productivity of ruminant livestock agriculture using a red seaweed. J Clean Prod. 2020;259 [Google Scholar]

- Klevenhusen F., Zeitz J.O., Duval S., Kreuzer M., Soliva C.R. Garlic oil and its principal component diallyl disulfide fail to mitigate methane, but improve digestibility in sheep. Anim Feed Sci Technol. 2011;166:356–363. [Google Scholar]

- Lanigan G. Metabolism of pyrrolizidine alkaloids in the ovine rumen. IV. Effects of chloral hydrate and halogenated methanes on rumen methanogenesis and alkaloid metabolism in fistulated sheep. Aust J Agric Res. 1972;23:1085–1091. [Google Scholar]

- Latham E.A., Anderson R.C., Pinchak W.E., Nisbet D.J. Insights on alterations to the rumen ecosystem by nitrate and nitrocompounds. Front Microbiol. 2016;7 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C., Beauchemin K.A. A review of feeding supplementary nitrate to ruminant animals: nitrate toxicity, methane emissions, and production performance. Can J Anim Sci. 2014;94:557–570. [Google Scholar]

- Lee C., Araujo R.C., Koenig K.M., Beauchemin K.A. Effects of encapsulated nitrate on enteric methane production and nitrogen and energy utilization in beef heifers. J Anim Sci. 2015;93:2391–2404. doi: 10.2527/jas.2014-8845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C., Araujo R.C., Koenig K.M., Beauchemin K.A. Effects of encapsulated nitrate on growth performance, carcass characteristics, nitrate residues in tissues, and enteric methane emissions in beef steers: finishing phase. J Anim Sci. 2017;95:3712–3726. doi: 10.2527/jas.2017.1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis D. The metabolism of nitrate and nitrite in the sheep; the reduction of nitrate in the rumen of the sheep. Biochem J. 1951;48:175–180. doi: 10.1042/bj0480175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L., Davis J., Nolan J., Hegarty R. An initial investigation on rumen fermentation pattern and methane emission of sheep offered diets containing urea or nitrate as the nitrogen source. Anim Prod Sci. 2012;52:653–658. [Google Scholar]

- Li L., Silveira C.I., Nolan J.V., Godwin I.R., Leng R.A., Hegarty R.S. Effect of added dietary nitrate and elemental sulfur on wool growth and methane emission of Merino lambs. Anim Prod Sci. 2013;53 [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Norman H.C., Kinley R.D., Laurence M., Wilmot M., Bender H., de Nys R., Tomkins N. Asparagopsis taxiformis decreases enteric methane production from sheep. Anim Prod Sci. 2018;58:681–688. [Google Scholar]

- Liu H., Vaddella V., Zhou D. Effects of chestnut tannins and coconut oil on growth performance, methane emission, ruminal fermentation, and microbial populations in sheep. J Dairy Sci. 2011;94:6069–6077. doi: 10.3168/jds.2011-4508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopes J., de Matos L., Harper M., Giallongo F., Oh J., Gruen D., Ono S., Kindermann M., Duval S., Hristov A.N. Effect of 3-nitrooxypropanol on methane and hydrogen emissions, methane isotopic signature, and ruminal fermentation in dairy cows. J Dairy Sci. 2016;99:5335–5344. doi: 10.3168/jds.2015-10832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma T., Chen D.D., Tu Y., Zhang N.F., Si B.W., Diao Q.Y. Dietary supplementation with mulberry leaf flavonoids inhibits methanogenesis in sheep. Anim Sci J. 2017;88:72–78. doi: 10.1111/asj.12556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma T., Chen D.D., Tu Y., Zhang N.F., Si B.W., Deng K.D., Diao Q.Y. Effect of dietary supplementation with resveratrol on nutrient digestibility, methanogenesis and ruminal microbial flora in sheep. J Anim Physiol Anim Nutr. 2015;99:676–683. doi: 10.1111/jpn.12264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machado L., Magnusson M., Paul N.A., de Nys R., Tomkins N. Effects of marine and freshwater macroalgae on in vitro total gas and methane production. PLoS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0085289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machado L., Magnusson M., Paul N.A., Kinley R., de Nys R., Tomkins N. Dose-response effects of Asparagopsis taxiformis and Oedogonium sp. on in vitro fermentation and methane production. J Appl Phycol. 2016;28:1443–1452. [Google Scholar]

- Machado L., Tomkins N., Magnusson M., Midgley D.J., de Nys R., Rosewarne C.P. In vitro response of rumen microbiota to the antimethanogenic red macroalga Asparagopsis taxiformis. Microbial ecology. 2018;75:811–818. doi: 10.1007/s00248-017-1086-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machmüller A., Dohme F., Soliva C.R., Wanner M., Kreuzer M. Diet composition affects the level of ruminal methane suppression by medium-chain fatty acids. Aust J Exp Agric. 2001;52:713–722. [Google Scholar]

- Machmuller A., Machmuller A., Soliva C.R., Kreuzer M. Methane-suppressing effect of myristic acid in sheep as affected by dietary calcium and forage proportion. Br J Nutr. 2003;90:529–540. doi: 10.1079/bjn2003932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machmüller A., Ossowski D.A., Kreuzer M. Comparative evaluation of the effects of coconut oil, oilseeds and crystalline fat on methane release, digestion and energy balance in lambs. Anim Feed Sci Technol. 2000;85:41–60. [Google Scholar]

- Machmüller A., Soliva C.R., Kreuzer M. Effect of coconut oil and defaunation treatment on methanogenesis in sheep. Reprod Nutr Dev. 2003;43:41–55. doi: 10.1051/rnd:2003005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maia M.R., Fonseca A.J., Oliveira H.M., Mendonça C., Cabrita A.R. The potential role of seaweeds in the natural manipulation of rumen fermentation and methane production. Sci Rep. 2016;6:32321. doi: 10.1038/srep32321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makkar H.P.S., Tran G., Heuzé V., Giger-Reverdin S., Lessire M., Lebas F., Ankers P. Seaweeds for livestock diets: a review. Anim Feed Sci Technol. 2016;212:1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Malik P.K., Kolte A.P., Baruah L., Saravanan M., Bakshi B., Bhatta R. Enteric methane mitigation in sheep through leaves of selected tanniniferous tropical tree species. Livest Sci. 2017;200:29–34. [Google Scholar]

- Mao H.-L., Wang J.-K., Zhou Y.-Y., Liu J.-X. Effects of addition of tea saponins and soybean oil on methane production, fermentation and microbial population in the rumen of growing lambs. Livest Sci. 2010;129:56–62. [Google Scholar]

- Martin C., Ferlay A., Mosoni P., Rochette Y., Chilliard Y., Doreau M. Increasing linseed supply in dairy cow diets based on hay or corn silage: effect on enteric methane emission, rumen microbial fermentation, and digestion. J Dairy Sci. 2016;99:3445–3456. doi: 10.3168/jds.2015-10110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin C., Morgavi D.P., Doreau M. Methane mitigation in ruminants: from microbe to the farm scale. Animal. 2010;4:351–365. doi: 10.1017/S1751731109990620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin C., Rouel J., Jouany J.P., Doreau M., Chilliard Y. Methane output and diet digestibility in response to feeding dairy cows crude linseed, extruded linseed, or linseed oil. J Anim Sci. 2008;86:2642–2650. doi: 10.2527/jas.2007-0774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Fernandez G., Duval S., Kindermann M., Schirra H.J., Denman S.E., McSweeney C.S. 3-NOP vs. halogenated compound: methane production, ruminal fermentation and microbial community response in forage fed cattle. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:1582. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGinn S.M., Beauchemin K.A., Coates T., Colombatto D. Methane emissions from beef cattle: effects of monensin, sunflower oil, enzymes, yeast, and fumaric acid. J Anim Sci. 2004;82:3346–3356. doi: 10.2527/2004.82113346x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGinn S.M., Chung Y.H., Beauchemin K.A., Iwaasa A.D., Grainger C. Use of corn distillers' dried grains to reduce enteric methane loss from beef cattle. Can J Anim Sci. 2009;89:409–413. [Google Scholar]

- McSweeney C.S., Palmer B., McNeill D.M., Krause D.O. Microbial interactions with tannins: nutritional consequences for ruminants. Anim Feed Sci Technol. 2001;91:83–93. [Google Scholar]

- Melgar A., Harper M., Oh J., Giallongo F., Young M., Ott T., Duval S., Hristov A. Effects of 3-nitrooxypropanol on rumen fermentation, lactational performance, and resumption of ovarian cyclicity in dairy cows. J Dairy Sci. 2020;103:410–432. doi: 10.3168/jds.2019-17085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mensinga T.T., Speijers G.J.A., Meulenbelt J. 17Health implications of exposure to environmental nitrogenous compounds. Toxicol Rev. 2003;22:41–51. doi: 10.2165/00139709-200322010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moate P.J., Williams S.R., Torok V.A., Hannah M.C., Ribaux B.E., Tavendale M.H., Eckard R.J., Jacobs J.L., Auldist M.J., Wales W.J. Grape marc reduces methane emissions when fed to dairy cows. J Dairy Sci. 2014;97:5073–5087. doi: 10.3168/jds.2013-7588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moate P.J., Williams S.R.O., Grainger C., Hannah M.C., Ponnampalam E.N., Eckard R.J. Influence of cold-pressed canola, brewers grains and hominy meal as dietary supplements suitable for reducing enteric methane emissions from lactating dairy cows. Anim Feed Sci Technol. 2011;166:254–264. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammed N., Ajisaka N., Lila Z., Hara K., Mikuni K., Hara K., Kanda S., Itabashi H. Effect of Japanese horseradish oil on methane production and ruminal fermentation in vitro and in steers. J Anim Sci. 2004;82:1839–1846. doi: 10.2527/2004.8261839x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreira G.D., Lima Pde M., Borges B.O., Primavesi O., Longo C., McManus C., Abdalla A., Louvandini H. Tropical tanniniferous legumes used as an option to mitigate sheep enteric methane emission. Trop Anim Health Prod. 2013;45:879–882. doi: 10.1007/s11250-012-0284-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mwenya B., Sar C., Santoso B., Kobayashi T., Morikawa R., Takaura K., Umetsu K., Kogawa S., Kimura K., Mizukoshi H., Takahashi J. Comparing the effects of β1-4 galacto-oligosaccharides and l-cysteine to monensin on energy and nitrogen utilization in steers fed a very high concentrate diet. Anim Feed Sci Technol. 2005;118:19–30. [Google Scholar]

- Newbold C.J., De La Fuente G., Belanche A., Ramos-Morales E., McEwan N.R. The role of ciliate protozoa in the rumen. Front Microbiol. 2015;6:1313. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.01313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newbold J., Van Zijderveld S., Hulshof R., Fokkink W., Leng R., Terencio P., Powers W., Van Adrichem P., Paton N., Perdok H. The effect of incremental levels of dietary nitrate on methane emissions in Holstein steers and performance in Nelore bulls. J Anim Sci. 2014;92:5032–5040. doi: 10.2527/jas.2014-7677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen S.H., Hegarty R.S. Effects of defaunation and dietary coconut oil distillate on fermentation, digesta kinetics and methane production of Brahman heifers. J Anim Physiol Anim Nutr. 2017;101:984–993. doi: 10.1111/jpn.12534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolan J.V., Godwin I.R., de Raphélis-Soissan V., Hegarty R.S. Managing the rumen to limit the incidence and severity of nitrite poisoning in nitrate-supplemented ruminants. Anim Prod Sci. 2016;56:1317–1329. [Google Scholar]

- Nolan J.V., Hegarty R., Hegarty J., Godwin I., Woodgate R. Effects of dietary nitrate on fermentation, methane production and digesta kinetics in sheep. Anim Prod Sci. 2010;50:801–806. [Google Scholar]

- Norris A.B., Crossland W.L., Tedeschi L.O., Foster J.L., Muir J.P., Pinchak W.E., Fonseca M.A. Inclusion of quebracho tannin extract in a high-roughage cattle diet alters digestibility, nitrogen balance, and energy partitioning. J Anim Sci. 2020;98 doi: 10.1093/jas/skaa047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odongo N.E., Bagg R., Vessie G., Dick P., Or-Rashid M.M., Hook S.E., Gray J.T., Kebreab E., France J., McBride B.W. Long-term effects of feeding monensin on methane production in lactating dairy cows. J Dairy Sci. 2007;90:1781–1788. doi: 10.3168/jds.2006-708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odongo N.E., Or-Rashid M.M., Kebreab E., France J., McBride B.W. Effect of supplementing myristic acid in dairy cow rations on ruminal methanogenesis and fatty acid profile in milk. J Dairy Sci. 2007;90:1851–1858. doi: 10.3168/jds.2006-541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olijhoek D.W., Hellwing A.L.F., Brask M., Weisbjerg M.R., Hojberg O., Larsen M.K., Dijkstra J., Erlandsen E.J., Lund P. Effect of dietary nitrate level on enteric methane production, hydrogen emission, rumen fermentation, and nutrient digestibility in dairy cows. J Dairy Sci. 2016;99:6191–6205. doi: 10.3168/jds.2015-10691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patra A.K. Recent advances in measurement and dietary mitigation of enteric methane emissions in ruminants. Front Vet Sci. 2016;3:39. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2016.00039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patra A.K., Saxena J. The effect and mode of action of saponins on the microbial populations and fermentation in the rumen and ruminant production. Nutr Res Rev. 2009;22:204–219. doi: 10.1017/S0954422409990163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patra A.K., Saxena J. A new perspective on the use of plant secondary metabolites to inhibit methanogenesis in the rumen. Phytochemistry. 2010;71:1198–1222. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2010.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patra A.K., Kamra D.N., Bhar R., Kumar R., Agarwal N. Effect of Terminalia chebula and Allium sativum on in vivo methane emission by sheep. J Anim Physiol Anim Nutr. 2011;95:187–191. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0396.2010.01039.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pen B., Takaura K., Yamaguchi S., Asa R., Takahashi J. Effects of Yucca schidigera and Quillaja saponaria with or without β 1–4 galacto-oligosaccharides on ruminal fermentation, methane production and nitrogen utilization in sheep. Anim Feed Sci Technol. 2007;138:75–88. [Google Scholar]

- Quack B., Wallace D.W.R. Air-sea flux of bromoform: controls, rates, and implications. Global Biogeochem Cycles. 2003;17 [Google Scholar]

- Rae H.A. Onion toxicosis in a herd of beef cows. Can Vet J. 1999;40:55. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebelo L.R., Luna I.C., Messana J.D., Araujo R.C., Simioni T.A., Granja-Salcedo Y.T., Vito E.S., Lee C., Teixeira I.A.M.A., Rooke J.A., Berchielli T.T. Effect of replacing soybean meal with urea or encapsulated nitrate with or without elemental sulfur on nitrogen digestion and methane emissions in feedlot cattle. Anim Feed Sci Technol. 2019;257 [Google Scholar]

- Reisinger A., Clark H., Cowie A., Emmet-Booth J., Gonzalez Fischer C., Herrero M. How necessary and feasible are reductions of methane emissions from livestock to support stringent temperature goals? Philos Trans Royal Soc A. 2021;379 doi: 10.1098/rsta.2020.0452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds C.K., Humphries D.J., Kirton P., Kindermann M., Duval S., Steinberg W. Effects of 3-nitrooxypropanol on methane emission, digestion, and energy and nitrogen balance of lactating dairy cows. J Dairy Sci. 2014;97:3777–3789. doi: 10.3168/jds.2013-7397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ripple W.J., Smith P., Haberl H., Montzka S.A., McAlpine C., Boucher D.H. Ruminants, climate change and climate policy. Nat Clim Change. 2014;4:2–5. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera-Ferre M.G., López-i-Gelats F., Howden M., Smith P., Morton J.F., Herrero M. Re-framing the climate change debate in the livestock sector: mitigation and adaptation options. Wiley Interdisc Rev: Clim Change. 2016;7(6):869–892. [Google Scholar]

- Romero-Perez A., Okine E., McGinn S., Guan L., Oba M., Duval S., Kindermann M., Beauchemin K. The potential of 3-nitrooxypropanol to lower enteric methane emissions from beef cattle. J Anim Sci. 2014;92:4682–4693. doi: 10.2527/jas.2014-7573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero-Perez A., Okine E., McGinn S., Guan L., Oba M., Duval S., Kindermann M., Beauchemin K. Sustained reduction in methane production from long-term addition of 3-nitrooxypropanol to a beef cattle diet. J Anim Sci. 2015;93:1780–1791. doi: 10.2527/jas.2014-8726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roque B.M., Salwen J.K., Kinley R., Kebreab E. Inclusion of Asparagopsis armata in lactating dairy cows' diet reduces enteric methane emission by over 50 percent. J Clean Prod. 2019;234:132–138. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi L.G., Fiorentini G., Vieira B.R., Neto A.J., Messana J.D., Malheiros E.B., Berchielli T.T. Effect of ground soybean and starch on intake, digestibility, performance, and methane production of Nellore bulls. Anim Feed Sci Technol. 2017;226:39–47. [Google Scholar]

- Russell J.B., Houlihan A.J. Ionophore resistance of ruminal bacteria and its potential impact on human health. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2003;27:65–74. doi: 10.1016/S0168-6445(03)00019-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell J.B., Strobel H. Effect of ionophores on ruminal fermentation. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1989;55:1. doi: 10.1128/aem.55.1.1-6.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]