Abstract

Background

The prevalent rate of incontinence-associated dermatitis (IAD) trends upward in older populations. Skin breakdown from IAD impacts the quality of life of older adults and reflects the quality of care in hospitals and long-term care facilities. Specific and appropriate interventions for prevention and care are needed. This systematic review aims to review optimal strategies for prevention and care for older adults with IAD.

Methods

PubMed, CINAHL, SCOPUS, Medline, ProQuest, ThaiLIS, ThaiJo, and E-Thesis were searched for articles published between January 2010 and December 2020. Only articles focusing on older adults were included for the review.

Results

Eleven articles met the inclusion/exclusion criteria. Interventions for the prevention and care of IAD among older adults were categorized as assessment, incontinence management/causative factors management, cleansing, application of medical products for both skin moisturizing and skin barrier, body positioning, nutrition promotion, health education and training, and outcome evaluation. Specific prevention and care strategies for older adults with IAD included using specific assessment tools, applying skin cleansing pH from 4.0 to 6.8, body positioning, and promoting food with high protein. Other strategies were similar to those reported for adult patients.

Conclusion

The systematic review extracted current and specific prevention and care strategies for IAD in older adults. The prevention and care strategies from this systematic review should be applied in clinical practice. However, more rigorous research methodology is recommended in future studies, especially in examining intervention outcomes. Nurses and other health professionals should be educated and trained to understand the causes of IAD in older adults and the specific prevention and care strategies for this population. Because older adults are prone to skin damage, and this type of skin breakdown differs from pressure ulcers, the tools for assessment and evaluation, and the strategies for prevention and care require special attention.

Prospero Registration Number

CRD42021251711.

Keywords: incontinence-associated dermatitis, moisture-associated skin damage, skin barrier function, skin breakdown, older adults, systematic review

Video Abstract

Point your SmartPhone at the code above. If you have a QR code reader the video abstract will appear. Or use:

Introduction

Incontinence-associated dermatitis (IAD) is a type of moisture-associated skin damage (MASD) caused by physical and chemical irritants.1 Older adults are prone to skin damage, especially when hospitalized in semi-intensive care units, intensive care units, or living in long-term care facilities.2 When exposed to urine and fecal matter, the skin becomes erythematous with the potential of developing dermal and epidermal erosion.3 The combination of an alkaline pH and noxious chemical irritants can stimulate the skin to erode. Damage to the skin can occur within 10–15 minutes following contact with moisture from stool or urine, causing overhydration and a slight swelling.4 In addition, the presence of friction and shear mechanical forces can decrease skin functioning and cause skin injury.1,2,5 Thus, the potential for skin breakdown among incontinent older adults requires careful assessment and care.

The prevalence and complications related to IAD trend upward in older populations. The prevalence of all types of incontinence in older adult age ≥65 years has been reported by a multisite study as 28.3%, with 18.2% for urinary incontinence, 2.3% for fecal incontinence, and 7.8% for dual incontinence.6 Another multisite study found 46.6% of the patients had urinary, fecal, or dual incontinence.7 Elsewhere, researchers reported that over 10% of the population experienced urinary incontinence. Of those, 15% were healthy older adults and 65% were frail older adults. Fecal incontinence has been reported to be from 1% to 10% of healthy older adults and from 17% to 66% of hospitalized older patients.1,4 Urinary and fecal incontinence caused IAD in 33% of the hospitalized patients and 41% of residents in long-term care facilities.4

Gray and Giuliano (2018) reported that the prevalence of IAD among persons with any type of incontinence was 45.7%. Over 25% was present on admission and 73% was acquired during hospitalization. The clinical characteristics of IAD were 52.3% mild, 27.9% moderate, and 9.2% severe, with 14.8% also having a fungal rash (secondary infection).7 Incontinence, especially dual incontinence, were 1.63 to 1.64 times more likely to develop from a facility-acquired pressure injury compared with those with no incontinence.6,7 These statistics reflect the importance of assessing and caring for older adults who are prone to develop and suffer from IAD.8–10

As people age, the skin becomes more susceptible to breakdown because of the aging processes. These include the loss of connective tissue and collagen, the flattening of dermal papillae, and the cross-linking inside the structure of elastin that can decrease the skin’s elasticity.2 As the skin ages, the epidermis thins and loses some of its elasticity, cell turnover is reduced, and the skin becomes more fragile. As a result, the skin is drier, more fragile, and prone to injury from excessive moisture.1,2 A high incident rate of incontinence and degeneration of skin among older adults makes them at risk of IAD. When older adults experience urinary and fecal incontinence together with the aging processes, the combination of noxious chemicals and moisture stimulates IAD.8,10 Therefore, older adults’ skin becomes more susceptible to breakdown, leading to a higher incident rate of IAD in this population.

There are serious complications and negative outcomes from IAD. Skin damage to older adults causes not only physical and mental suffering, and the potential of secondary infections, but also increases the costs of care and longer lengths of stay.5 For example, Lumber (2019) reported that IAD patients’ symptom severity can range from a low level, such as feeling uncomfortable, to a high level, such as excessive painful ulceration. IAD was one significant factor in causing secondary infection with an increased susceptibility to pressure ulceration.2

Pressure ulcers and secondary infection cause longer lengths of stay and higher costs of care.4 In one financial study of IAD, the estimated product cost ranged between US$0.05 and $0.52 per application for prevention and between $0.20 and $0.35 for treatment. The product cost for prevention ranged between $0.23 and $20.17 per patient/day. The product cost of IAD prevention and treatment per patient/day ranged between $0.57 and $1.08.11 Moreover, medications used to treat these two conditions can cause iatrogenesis, such as drug interactions and side effects of treatment.2,5

First line prevention before the occurrence of these complicated problems is recommended. However, some people may already have IAD when they are admitted to a hospital or long-term care facility. The previously mentioned multisite study found that 25.1% of IAD was present on admission.7 In this case, both prevention and care strategies of IAD should be implemented.1

Several studies and systematic reviews have been conducted, and general prevention and care guidelines for IAD have been recommended.4,5,9,12–17 Beeckman et al (2016) reported that the principles of prevention and care for IAD are cleansing, moisturizing, and protecting.12 Others have provided details about general prevention and care guidelines, such as skin assessment, skin cleaning, skin barrier, containment device, and treatment of secondary infection.4,5 However, their populations were adult or pediatric patients.

What is lacking is a specific comprehensive review and strategic synthesis of various options for older adults. Health care providers need to evaluate multiple options and interventions applicable to their populations of interest, especially older adults. Therefore, in conducting a systematic review, we sought to answer a clinically important question: What are the specific and appropriate interventions required to prevent and care for older adults with IAD? The aim was to provide a comprehensive review of specific strategies for both the prevention and care of older adults with IAD.

Materials and Methods

Design

A systematic review with narrative summary was undertaken. We conducted the review using the Preferred Reporting Items of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) checklist guidelines and the standardized critical appraisal instruments from the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI). Our processes were started by formulating the review question and aim, defining the inclusion and exclusion criteria, developing the search strategy, locating and selecting relevant articles, assessing their quality, extracting data, and analyzing and interpreting the results.18 The protocol to conduct the systematic review was published and registered with PROSPERO (CRD42021251711).

Search Strategy

We searched for empirical articles published between January 2010 and December 2020 in eight databases: PubMed, CINAHL, SCOPUS, Medline, ProQuest, ThaiLIS, ThaiJo, and E-Thesis. An ancestry search of the references of identified studies was also conducted, including a manual search of journals. The following search terms were used to access all possible and matched studies: “incontinence associated dermatitis” OR IAD OR “incontinence-associated dermatitis” OR “moisture associated skin damage” OR “diaper dermatitis” OR “perineal skin injury” OR “irritant contact dermatitis of the vulva” OR “skin breakdown” OR “skin barrier function*.” The second group of keywords were intervention OR care OR prevention OR program OR protocol OR guideline OR treatment. The third group of keywords was “routine care” OR “usual care” OR “regular care.” The three groups were combined using “AND.”

Because we did not specify an older adult population as a search term, the results from the initial search mixed various age groups. This was an opportunity to appraise the studies more broadly. However, by subsequently applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria during the screening process, this allowed us to explore the germane research. Moreover, we took note of the multiple outcomes reported in the studies. Outcomes were typically reported and discussed in the studies’ results and discussion sections.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion criteria were that the articles reported on research, projects, or were a review of the literature related to incontinence-associated dermatitis; focused on older adults (60 years or older) or reported interventions or management of older adults; published in English or Thai peer reviewed journals or thesis/dissertations; and available online in full text. Abstracts from academic conferences without full text were excluded.

Data Extraction

On the JBI data extraction form,18 we recorded the authors, types of articles, designs, settings, level and certainty of evidence, methodological quality, sample size, prevention and care strategies for IAD, and outcomes. Research notes were added for comments. Prior to starting the review, we practiced screening articles, extracting data, and assessing the quality together to make sure that the processes and results we had undertaken were accurate.

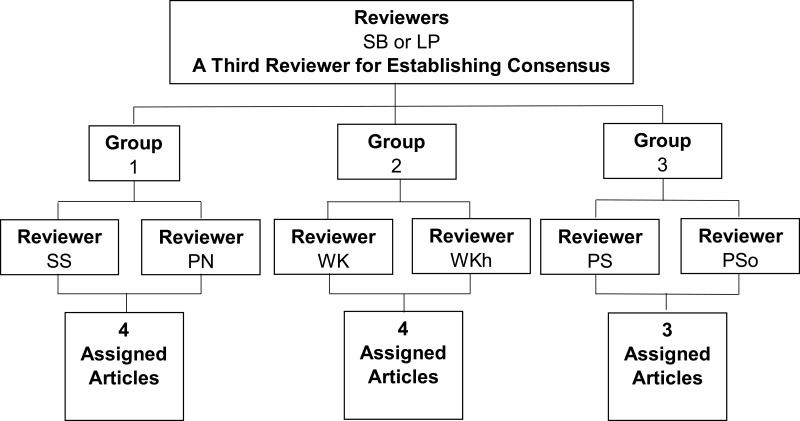

Of the eight reviewers, two were assigned to be a third opinion when reaching consensus. The other six reviewers were divided into three groups for screening and reviewing articles. First, they determined if studies met the inclusion/exclusion criteria. Then, the selected articles were appraised by their respective JBI checklists. To be considered for review, we used a cut point positive appraisal (ie, “yes”) for at least 50% of the items. Thereafter, we appraised the groups’ assigned articles and extracted data (Figure 1). If a group’s two reviewers could not agree on an appraisal, a third independent reviewer met with the group to reach consensus. The appraisal process was used to avoid errors and misinterpretations of research findings and to elevate the quality of the systematic review.

Figure 1.

Diagram for group assignment and independent review.

Quality Appraisal

We individually reviewed the selected articles under consideration using the respective JBI standardized critical appraisal checklists to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews,19 randomized controlled trials (RCTs),20 texts and opinions,21 and case report studies.22 Methodological quality was graded into the four categories of very low, low, moderate, and high quality.23 Because the GRADE methodology is outcome centric, it was applicable only to the quantitative studies we found (ie, RCTs and cases studies) and not the review articles.

We developed a table to collect all relevant data from the studies, minimize the risk of errors in transcription, guarantee precision when checking information, and serve as a record for the review. The table was also used to identify themes across the studies. Reviewers’ comments and data recording were collected and organized using Mendeley reference manager software.

Synthesis

Extraction of quantitative data to conduct meta-analysis was not possible due to the small sample size, heterogeneity of the study population, different types of research design, outcomes measures, time of measuring, and data analysis across the studies. The results were placed in tabular and narrative form to include the studies’ description, year, setting, design, sample size, prevention and care for IAD, and outcomes. A comment column was added for discussion and recommendation. We summarized the prevention and care strategies for IAD in older adults with additional discussion and suggestions.

Results

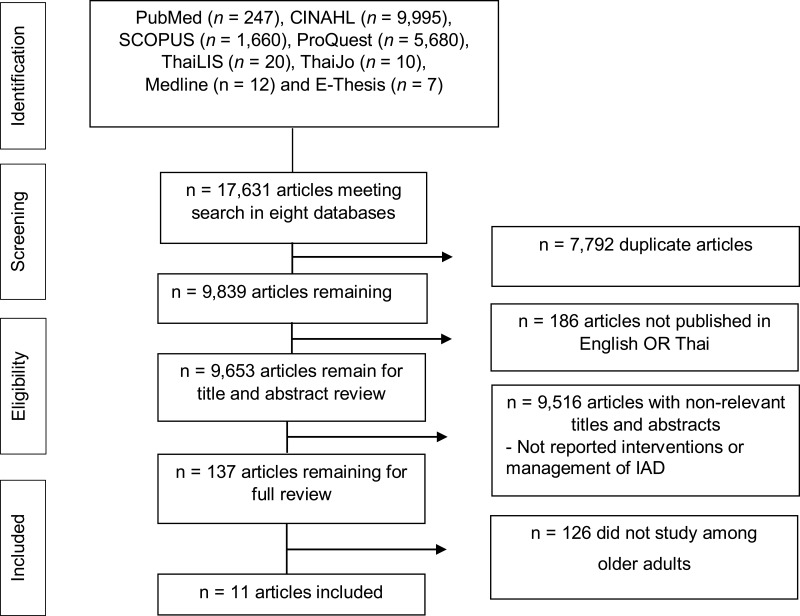

From the initial results of 17,631 articles, we screened the titles and abstracts of 9653 articles. Based on the inclusion/exclusion criteria and consensus among members of the research team, 11 articles were selected for the final comprehensive review, standardized critical appraisal, and synthesis. Figure 2 displays the PRISMA flow diagram of the information flow during the review process.

Figure 2.

Flow chart of the review process and results.

Notes: Adapted from: Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. doi:10.1136/bmj.n71.37 Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/legalcode).

Characteristics of the Articles

Scores for the critical appraisal of the two RCTs were 1024 and925 out of a possible 13 points (Table 1). The critical appraisal score of the integrative review was 7 out of 11 possible points26 (Table 2). The critical appraisal scores of the six literature reviews were427 and52,8,28–30 out of a possible 6 points (Table 3). Scores for the two case reports were51 and610 out of an 8 possible points (Table 4). Four articles were graded for level of quality. Two of those had low methodological quality,1,10 and two had moderate methodological quality24,25 (Table 5).

Table 1.

Critical Appraisal of the Selected Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs)

| JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Randomized Controlled Trials* | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Studies/Total Score | Was true Randomization Used for Assignment of Participants to Treatment Groups? | Was Allocation to Treatment Groups Concealed? | Were Treatment Groups Similar at the Baseline? | Were Participants Blind to Treatment Assignment? | Were those Delivering Treatment Blind to Treatment Assignment? | Were Outcomes Assessors Blind to Treatment Assignment? | Were Treatment Groups Treated Identically Other Than the Intervention of Interest? | Was follow up Complete and if Not, were Differences Between Groups in Terms of their Follow up Adequately Described and Analyzed? | Were Participants Analyzed in the Groups to Which They were Randomized? | Were Outcomes Measured in the Same Way for Treatment Groups? | Were Outcomes Measured in a Reliable Way? | Was Appropriate Statistical Analysis Used? | Was the Trial Design Appropriate, and Any Deviations From the Standard Rct Design (Individual Randomization, Parallel Groups) Accounted for in the Conduct and Analysis of the Trial? |

| Sugama et al (2012)/(10/13)24 | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | U | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Kon et al (2017)/(9/13)25 | Y | Y | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U |

Notes: *Checklist reproduced from: Tufanaru C, Munn Z, Aromataris E, Campbell J, Hopp L. Chapter 3: Systematic reviews of effectiveness. In: Aromataris E, Munn Z, editors. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. JBI; 2020. Available from: https://synthesismanual.jbi.global20.

Abbreviations: Y, yes; N, no; U, unclear.

Table 2.

Critical Appraisal of the Selected Systematic Reviews

| JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Systematic Reviews and Research Syntheses* | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Studies/Total Score | Is the Review Question Clearly and Explicitly Stated? | Were the Inclusion Criteria Appropriate for the Review Question? | Was the Search Strategy Appropriate? | Were the Sources and Resources Used to Search For Studies Adequate? | Were the Criteria for Appraising Studies Appropriate? | Was Critical Appraisal Conducted by Two or More Reviewers Independently? | Were There Methods to Minimize Errors in Data Extraction? | Were the Methods Used to Combine Studies Appropriate? | Was the Likelihood of Publication Bias Assessed? | Were Recommendations For Policy and/or Practice Supported by the Reported Data? | Were the Specific Directives for New Research Appropriate? |

| Corcoran & Woodward. (2013)/(7/11)26 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | U | U | N | Y | Y |

Notes: *Checklist reproduced from: Aromataris E, Fernandez R, Godfrey C, Holly C, Kahlil H, Tungpunkom P. Summarizing systematic reviews: Methodological development, conduct and reporting of an Umbrella review approach. International Journal of Evidence Based Healthcare. 2015;13(3):132–140. https://doi.org/10.1097/XEB.0000000000000055.19 Copyright © 2015, International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare © 2015 The Joanna Briggs Institute.

Abbreviations: Y, yes; N, no; U, unclear.

Table 3.

Critical Appraisal of the Selected Reviews (Text and Opinion Papers)

| JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Text and Opinion Papers* | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Studies/Total Score | Is the Source of the Opinion Clearly Identified? | Does the Source of Opinion Have Standing in the Field of Expertise? | Are the Interests of the Relevant Population the Central Focus of the Opinion? | Is the Stated Position the Result of an Analytical Process, and is There Logic in the Opinion Expressed? | Is There Reference to the Extant Literature? | Is Any Incongruence with the Literature/Sources Logically Defended? |

| Kliangprom & Putivanit (2017)/(5/6)28 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N |

| Iamma, W. (2017)/(4/6)27 | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N |

| Yates A. (2018a)/(5/6)29 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N |

| Yates A. (2018b)/(5/6)30 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N |

| Lumbers M. (2019)/(5/6)2 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N |

| Holloway, S. (2019)/(5/6)8 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N |

Notes: *Checklist reproduced from: McArthur A, Klugarova J, Yan H, Florescu S. Innovations in the systematic review of text and opinion. International Journal of Evidence Based Healthcare. 2015;13(3):188–195. https://doi.org/10.1097/XEB.0000000000000060.21 Copyright © 2015, International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare © 2015 The Joanna Briggs Institute.

Abbreviations: Y, yes; N, no; U, unclear.

Table 4.

Critical Appraisal of the Selected Case Reports

| JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Case Reports* | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Studies/Total Score | Were Patient’s Demographic Characteristics Clearly Described? | Was the Patient’s History Clearly Described and Presented as a Timeline? | Was the Current Clinical Condition of the Patient on Presentation Clearly Described? | Were Diagnostic Tests or Assessment Methods and the Results Clearly Described? | Was the Intervention(s) or Treatment Procedure(s) Clearly Described? | Was the Post-Intervention Clinical Condition Clearly Described? | Were Adverse Events (Harms) or Unanticipated Events Identified and Described? | Does the Case Report Provide Takeaway Lessons? |

| Beldon, P. (2012)/(5/8)1 | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N |

| Parnham, Copson, and Loban (2020)/(6/8)10 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N |

Notes: *Checklist reproduced from: Moola S., Munn Z, Tufanaru C et al. Chapter 7: Systematic reviews of etiology and risk. In: Aromataris E, Munn Z, editors. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. JBI; 2020. Available from: https://synthesismanual.jbi.global.22

Abbreviations: Y, yes; N, no; U, unclear.

Table 5.

Quality Assessment Results of the Selected Studies

| Quality Assessment of the Evidence by GRADE Guideline* | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | a Risk of Bias (Limitation of Study Design, Confounding Factors, Missing Data, Adherence Measurement) | b Precision (Methodology, Statistical Certainty, Amount of Information on A Certain Factor How Precisely an Object of Study is Measured) | c Directness (Extent to Which the People, Interventions, and Outcome Measures are Similar to Those of Interest, Confident Results Come From the Direct Evidence) | d Consistency (Relevant Measurement Application Where Several Items that Propose to Measure the Same General Construct Produce Similar Scores, no Overlapping and Missing, Statistical Significance) | Certainty of Evidence | |||||

| Low | Unclear | High | Precise | Imprecise | Direct | Indirect | Consistent | Inconsistent | ||

| Beldon, P. (2012)1 | √ | √ | √ | √ | Low | |||||

| Sugama et al. (2012)24 | √ | √ | √ | √ | Moderate | |||||

| Kon et al. (2017)25 | √ | √ | √ | √ | Moderate | |||||

| Parnham, Copson, and Loban (2020)10 | √ | √ | √ | √ | Low | |||||

Notes: aRisk of bias; bPrecision; cDirectness; dConsistency. *GRADE guideline reproduced from: Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G, Oxman A, editors. GRADE Handbook. 2013. Available from: https://gdt.gradepro.org/app/handbook/handbook.html?fbclid=IwAR04O97yy. Retrieved June 4, 2021.23 © 2013 - The GRADE Working Group.

Publication years for the 11 articles ranged from 2012 to 2020. Two were in 2012;1,24 one in 2013;26 three in 2017;25,27,28 two in 2018;29,30 two in 2019;2,8 and one in 2020.10 Six articles were from the United Kingdom,1,2,8,10,29,30 two from Japan,24,25 two from Thailand,27,28 and one from a multi-site setting.26 The number of participants for the studies ranged from 3 to 1618 older adults.1,10,24–26 Because six studies were reviews of the literature, the authors did not report or need to report the participants2,8,27–30 (Table 6).

Table 6.

A Summary of the Reviewed Studies About Prevention and Care Among Older Adults with Incontinence-Associated Dermatitis (IAD)

| Authors | Type of Article and Design | Settings | Level, Certainty of Evidence and Methodological Quality | Sample Size | Prevention, Care, and Outcomes | Research Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beldon, P. (2012)1 | Mixed: Literature review and cases report | United Kingdom (In-patient department) | Level 4.d Lowbd (5/8) | 3 mixed sex | 1. Assessment and management of the causes of incontinence. 2. Use skin cleansing pH between 4 to 6.8 to maintain an acid mantle, natural oils, and a moist surface. Cleansing after each episode of incontinence should be performed promptly. Soap and water are not advised. 3. Apply skin moisturizing to replace natural lubricants lost during skin cleansing. 4. Apply skin barrier such as petroleum, dimethicone (LBF Barrier Cream), lanolin or zinc oxide-based cream. Individual care is recommended. 5. Use an incontinence pad or containment devices. 6. Three patients who were washed by water including a small amount of emollient, water alone and patted dry, warm water and patted dry, and applying LBF barrier cream, reported restored skin integrity, improved skin texture, reduced pain, and provided comfort and assurance of efficacy to the individual. |

1. An intervention with products used for prevention and care of IAD, a flow chart or step by step guideline is not provided. 2. The methodology of implementing the intervention (LBF Barrier Cream) did not control for confounding factors (age, chronic diseases, conditions, and severity levels of IAD) when studying the outcomes (skin recovery, pain, and comfortable). |

| Sugama et al. (2012)24 | Research Article: RCT | Japan (Geriatric medical hospital) | Level 1.c Moderatea (10/13) | 60 female | 1. To prevent IAD, the researchers developed an improved apertured film plus feminine pad to decrease inflammation caused by incontinence. This special design was the dry-feel Attends Incontinence Care Pad with frontal absorbent material on a pad 23 cm. wide. The pad was designed to absorb urine in the frontal area by using a combination of absorbent polymer and pulp only to minimized exposure of the buttocks to urine, while a second sheet is embedded between the top sheet and the absorbent material to prevent the absorbed urine from flowing back to the pad surface and buttocks area. In addition, the slit in the urinary excretion point and the flexed convex surface of the pad fit in the perineal region, also preventing leakage to the buttock area. This pad improved frontal absorption and backflow as compared with conventional products. The number of patients recovered completely from IAD in the experimental group (13 patients) than in the control group (4 patients). The time of recovery in experimental group was significantly faster than control group. However, moisture content and skin pH were similar in both groups. | 1. The experimental group wore the hospital standard pad and a diaper during the night (20:00–9:00) because the volume of the test pad was not adequate for changing the incontinence pad during the night in the test hospital. The control group wore the standard pad and diaper at all times. This may affect research findings because experimental group wore mixed styles of pad. If health care professionals expect the same results in practice, they should apply the same procedure used in the study. Wearing the test pad for 24 hours needs to be explored in future study. 2. This study included only females, bedridden, older adults; therefore, its findings cannot be applied to males and older adults living sedentary or ambulatory lifestyles. 3. The RCT study did not calculate sample size based on a power analysis, so level of evidence from this study was quiet low. |

| Corcoran & Woodward. (2013)26 | Research Article: Integrative review | Multiple settings (Long term care and in-patient department) | Level 3.b-(7/11) | 6 studies (1618 mixed sex) | 1. The products to prevent and treat IAD were the following: barrier film for 14 days, zinc oxide oil for 14 days, skin cleanser, barrier cream, Cavilon barrier film 3 times a week, 12% zinc oxide after each incontinent episode, 1% dimethicone after each incontinent episode, 43% petrolatum after each incontinent episode, 98% petrolatum after each incontinent episode, a non-aqueous product, a petrolatum containing water in oil, a petrolatum containing oil-in-water, two zinc-oxide-based products, glycerin, a moisturizer containing lanolin, a fine-grain emulsion of 50% lanolin, beeswax and petrolatum, Cavilon barrier film 3 times a day, and a petrolatum ointments as needed. 2. The zinc oxide product was the most effective in preventing irritation to skin but offered the least hydration. In contrast, the glycerin offered the most hydration, with the oil-in-water and dimethicone product offering hydration up to 6 hours. |

1. Studies showed that using the barrier as part of a skin care protocol can help to prevent and/or treat IAD; however, there is insufficient evidence to recommend any one barrier product for use in a standard skin care protocol for IAD. 2. Some of the studies had small sample sizes and short evaluation times. Using larger sample sizes and a long-term study may return stronger and more effective recommendations to guide practice. 3. The studies used a variety of methods to assess skin integrity. Some did not report what instrument was being used to measure the severity of IAD. This may affect validity of the selected studies. 4. Some studies reported only the product used, however, authors did not report how to apply or how often the products were being used to prevent or treat IAD. 5. Females were the majority group in the studies, so this may have affected the results. A subgroup analysis to compare between male and female should be conducted. 6. Results could be biased because the products were received from the companies. 7. One study included in this review reported that participants had poor compliance with the protocol and was lost to follow-up. The results may not represent the true effect of the products. 8. Some studies applied the products under a protocol. However, it is difficult to conclude that the results were from the product or protocol. 9. The authors systematically searched the literature but did not use all standard processes for their review. This could limit their quality of the review. |

| Kliangprom & Putivanit (2017)28 | Academic Article: Literature review | Thailand | Level 5.c-(5/6) | - | 1. Assessment and reassessment (no identification when and how often to assess) 2. Avoid and reduce causes and risks of skin breakdown: Avoid rubbing, wiping and rinsing. Leave adhesive bandage/gauze on the skin for over 24 hours. When removing adhesive bandage, peel it back carefully rather than pulling it up and off; olive oil helps loosen the adhesive during removal. Manage incontinence: If using a diaper, change it every four hours instead of eight hours. 3. Apply skin protectant: Skin barrier film (Aloe Vesta 2-in-1 Protective Ointment, Secura TM Protective Ointment, and Baza Protect); skin barrier cream. 4. Select skin cleansing creme with natural pH and surfactant as well as skin nourishing products. Cleansing products should have a pH 5.2–5.5. Apply skin care lotion and moisturizer at least two times a day, and eat food with high protein. |

This is a literature review that did not provide systematic search methods. Articles may not represent all studies with older adults. Details for caring for IAD were not given, such as what were the recommend products, how to apply the products, the quantity to apply, the frequency to apply, and when to apply? An outcome evaluation to identify the effectiveness of IAD care was not provided. |

| Iamma, W. (2017)27 | Academic article (miscellaneous): Literature review | Thailand | Level 5.c-(4/6) | - | 1. Observe and manage cause of incontinence, such as evacuation and urinary catheterization. 2. Clean immediately after each episode of urine and bowel incontinence by using products without alcohol, chemical color, lotion, and perfume/fragrance. Do not use warm water to wash. If using soap, use 2–3 small drops of liquid soap for children. Gently clean the wet skin with a soft towel. 3. Nurture skin by applying lotion without alcohol, chemical color, and perfume/fragrance. 4. Apply skin barrier cream, such as petroleum gel, zinc oxide, and dimethicone. 5. Use a pad instead of a diaper to promote air flow and decrease area of skin contact with urine and feces. 6. Position the person on one side instead of laying on the back to decrease the area of skin contact with urine and feces. |

1. Missing was how the product was to be applied, the quantity to apply, and the frequency to apply. 2. All preventions and treatments were based on the author’s experience, which was the lowest level of evidence. An outcome evaluation to identify the effectiveness of IAD care was not provided. |

| Kon et al. (2017)25 | Research article: RCT | Japan (Long term care) | Level 1.c Moderateb (9/13) | 33 female | 1. Intervention group received skin cleansing with wet towels at each pad change, moisturizing and protective skin cleanser (including polyquaternium-51, an emollient and copolymer; and dimethicone were applied once a day); moisturizing (skin cream under investigation was applied three times daily and after product changes); and skin protectant (3M Cavilon Skin Barrier Cream was applied three times daily) for 14 days. The control group received only cleansing with wet towels at each pad change, moisturizing, and protective skin cleanser, including polyquaternium-51, an emollient and copolymer, and dimethicone once a day for 14 days. 2. In the experimental group, erythema was lower than in the control group after 14 days (p = 0.004). Moreover, the application of skin barrier cream was significantly associated with increased stratum corneum hydration (B = 0.443, p = 0.031), decreased skin pH (B = −0.439, p = 0.020), and decreased magnitude of erythema (B = −0.451, p = 0.018). |

The study had a small sample size (33 instead of 133 from sample calculation), included females only, and had a short time evaluation period. This study included patients with mild IAD (inflammation only without skin loss or cutaneous rash). Thus, the findings may not be generalizable to older women with higher severity of IAD. However, the study controlled for confounding factors, such as temperature (controlled at 20–26 degree Celsius) and relative humidity (35–52%) at studied settings. |

| Yates, A. (2018a)29 | Academic article: Literature review | United Kingdom | Level 5.c-(5/6) | - | 1. Screening: Incontinence assessment, IAD risk assessment, and skin damaging assessment (if skin is already damaged) should be performed. 2. Cleaning: Remove irritants from skin such as urine/feces by using skin cleanser with pH near to that of the skin, use a gentle technique to minimize friction, avoid alkaline soaps, use a no-rinse liquid cleanser or pre-moistened wipe, and be gentle with dry skin. 3. Protection: Place a barrier on skin to prevent direct contact with urine/feces using petroleum jelly, zinc oxide, dimethicone, and acrylate terpolymer. 4. Restoring: Replenish the skin barrier using a tropical skin care product such as moisturizers or emollients. 5. Other: Identify, assess, and treat patients with incontinence, use skin risk assessment tools, provide good skin care regime, use appropriate barrier products, use the correct continence products (fecal management system, pads), use the correct absorbency pad product (ie, too high absorbency can be as damaging as not high enough), smooth pads to prevent creases, inspect skin at regular intervals, and keep individuals hydrated. Don’ts: Use traditional soap and water, avoid use of certain creams/talcum powder, do not double pad, do not rub skin dry, do not assume it is a pressure sore, do not assume incontinence is inevitable, and leave soiled pad products in contact with skin for any length of time. |

This review provided specific care for older adults. However, the author did not state the process used to comprehensively search to confirm that all relevant articles were included before making a conclusion. Moreover, the recommendation missed some specific details, such as the quantity of the product to apply, the frequency of application, and when to apply the product. Finally, the author provided only interventions or products to deal with IAD but did not indicate when results would be noticed after applying the interventions and products and how to evaluate the outcomes. |

| Yates, A. (2018b)30 | Academic article: Literature review | United Kingdom | Level 5.c-(5/6) | - | 1. Prevention of skin problems: Incontinence assessment, IAD risk assessment, and grade of damage should be conducted if IAD has already occurred. Avoidance of IAD should be the first priority. This should include routine continence and skin assessment, appropriate containment, and implementation of an IAD management system. 2. Use of barrier products: Barrier products can act as a waterproof physical barrier between the skin and other substances. Following an episode of incontinence, the skin should be cleaned immediately using a cleanser with a similar pH to the skin, avoiding soap and water. The skin barriers can be creams, ointments, pastes, and spray. Applying greasy creams and ointments is a concern. They might clog pores on a continence pad product, leading to pad product failure and leakage. Advances in product development and improvement in pads might be used to fix the problem of clogging. |

This academic article provided few concepts of taking care of IAD in older adults. More information is needed, such as names of the recommended products and how to apply and when we can use the product. The health care professional will find it is difficult to apply knowledge from this article. |

| Lumbers, M. (2019)2 | Academic article: Literature review | United Kingdom | Level 5.c-(5/6) | - | 1. Clean: Skin following an episode of incontinence should be cleaned and dried carefully as soon after the event as possible. Maintaining a pH of 5.5 and ensuring a slightly acidic mantle to discourage bacteria colonization while removing any debris are important. 2. Protect and Restore: Barrier products, in the form of creams, films, and sprays, should be applied to prevent moisture from urine and feces causing overhydration and damage to the skin. A product for promoting moisturizing intact skin should be applied. Some barrier products adversely affect the absorption ability of fluid into incontinence. This is a concern because it may block the pores of the incontinence pads, preventing the fluid from being absorbed into the pad. Thus, fluid may leak and create a wet environment that contributes to further skin damage. 3. Address causative factors: First line management should involve a review of the patient’s toilet practices. A non-invasive method should be the first choice in preventing incontinence. 4. Educate staff, patients, and care givers, who should take part in caring for IAD. If they are educated, they not only address issues but are well placed to help prevent recurrence. |

This academic article provided the concepts of taking care of a patient with IAD. However, few details are provided. The article presents concepts, but the practitioner needs more concrete guidelines in caring for patients with IAD. |

| Holloway, S. (2019)8 | Academic article: Literature review | United Kingdom | Level 5.c-(5/6) | - | 1. Structured skin care regimen included:

|

The author provided only concepts of taking care of IAD, with few details. The concepts would be difficult to implement in practice because skin care, cleaning procedures, and barrier products to take care of IAD were not given. More information is need about the quantity of the products to be applied, when to apply the product, how long to clean up after each episode of incontinence, and the frequency of application. |

| Parnham, Copson, and Loban (2020)10 | Research Article: Cases report | United Kingdom (In-patient department) | Level 4.d Lowbd (6/8) | 3 female | 1. Assessment: Three assessment tools were provided, including IAD severity instrument which gives a severity score, anatomical location, and range of photographs:

2. Address the underlying causes: Management system of incontinence. 3. Implement a structured skin care regimen:

|

1. Only concepts were presented but a product’s name was reported in three case studies. 2. Few case studies may limit the conclusion of this studies. 3. One of the three cases was classified as severe IAD, other two were not classified. The authors present the effectiveness of products only for patients who had IAD but did not address IAD prevention. |

|

Joanna Briggs Institute levels of evidence Level 1.c - Experimental study: Randomized controlled trial Level 3.b - Observational analytical study: Systematic review of quasi-experimental and other lower study designs Level 4.d - Observational descriptive study: Case study Level 5.c – Expert opinion: Bench research/single expert opinion | ||||||

|

GRADE Working Group Grades of Evidence for certainty of evidence High: The research provides a very good indication of the likely effect. The likelihood that the effect will be substantially different is low. Moderate: The research provides a good indication of the likely effect. The likelihood that the effect will be substantially different is moderate. Low: The research provides some indication of the likely effect. The likelihood that it will be substantially different (a large enough difference that it might have an effect on a decision) is high. Very low: The research does not provide a reliable indication of the likely effect. The likelihood that the effect will be substantially different (a large enough difference that it might influence a decision) is very high. | ||||||

|

Explanations a. Risk of bias (low, unclear, high) b. Consistency (consistency, inconsistency, unknown/non applicable) d. Precision (precise, imprecise) | ||||||

Notes: The scores of Methodological Quality of the Studies are shown in fractions based on Joanna Briggs Institute and the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tools.

Of the five studies that indicated the participants’ sex, two reported both males and females,1,26 whereas three focused only on female older adults.10,24,25 There were seven reviews and four research articles. Six articles were literature reviews with concluding text and opinions.2,8,27–30 One article was an integrative review,26 whereas one article incorporated a mixed design using a literature review and case reports.1 One article was only a case report.10 Two articles were studies that used an RCT design24,25 (Table 6).

Interventions for prevention and care of IAD were categorized into eight groups: assessment, incontinence management/causative factors management, cleansing, medical products application, body positioning, nutrition promotion, health education and training, and outcomes evaluation (Table 6). Finally, outcomes were reported for five studies.1,10,24–26 Details for each intervention and care are provided, as follows.

Prevention and Care for Older Adults with IAD

Assessment

Assessment was an initial process either to identify the risk of IAD if it had not yet developed or to grade or determine the severity level of the IAD if it was present. Assessment was found in five articles. The following assessment tools were mentioned: Incontinence Assessment, IAD Risks Assessment, Skin Damage Assessment, Grade of Skin Damage, IAD Severity Instrument, Ghent Global IAD Categorization Tool, and Skin Moisture Alert Reporting Tool.1,10,28–30 Researchers and experts recommended that health care providers should start at assessment to seek for causes of incontinence, risks of IAD, and levels of skin damage before planning to prevent and care for IAD.1,10,28–30 This would help health care professionals to identify the levels of risk and severity of IAD and to provide specific prevention and care strategies for each level of skin damage.

Incontinence Management/Causative Factors Management

Because prevention should be the major concern, managing IAD causative factors is the preferred strategy. Methods to manage incontinence and address causative factors were reported in eight articles. Example were the use of diapers, evacuation and urinary catheterization, absorbency and smooth pads, an improved aperture film plus a feminine pad, and a review of patient toileting techniques. However, some authors recommended using an appropriate containment or continence management system without giving the details of a guideline or explaining what the appropriate containment might be.8,10,30 Other authors provided more details about what interventions or products should be used to manage incontinence or prevent causative factors, such as diapers,28 evacuation and urinary catheterization,27 absorbency and smooth pads,29 an improved aperture film plus feminine pad,24 and a review of patient toileting techniques.2 However, Iamma (2017) points out that using a pad instead of a diaper is a better way to promote air flow and decrease the area of skin contact from urine and fecal matter.27 Most importantly, the use of an invasive technique in trying to control incontinence is not the first choice for managing IAD.2

Cleansing

The way to decrease chemical irritation and moisture damage to the skin is cleansing the affected area after each episode of urination and defecation. This process includes medical material removal, cleansing products, cleaning techniques, and water or waterless applications. Kliangprom and Putivanit (2017) state that a bandage or gauze dressing applied to the buttock area should remain in place for over 24 hours before removal and cleaning. Moreover, olive oil should be used to aid removing the bandage and peel back the bandage when removing it, not pulling upward on the skin.28 Cleansing should be started either immediately of incontinence,27,30 as quickly as possible,1,2 at least twice a day,28 or after each episode of incontinence.10,26 The cleansing product should not contain alcohol, chemical color, lotion, or perfume/fragrance.27 Some authors suggested that the pH for skin cleansing should range from 4.0 to 6.8.1,2,8,27,29,30 Soap and warm water,1,10,30 wet cloths and towels,10 and alkaline soap were not advised;30 however, Kon et al (2017) recommended using wet towels.25 If using soap, however, liquid soap for children was preferred.27 A disposable wash basin for cleaning the skin should be used to reduce cross infection.8 Rub, wipe, and rinse were actions to be avoided.27,28,30 In contrast, tapping technique and no-rinse cleansers, such as liquids,29 soaps, sprays, and foams,10 and gentle blotting of moisture27,28 should be used to reduce any cause or risks of skin breakdown. Examples of moisturizing and protective skin cleansers were provided.10,25

Medical Products Application

Medical products are any products used to diagnose or manage older adults with IAD, including pharmaceutical products and medical devices. We found two groups of medical products mentioned by authors: skin moisturizers and skin barriers.8 The skin moisturizing products included a lotion without alcohol, chemical colors, or perfumes/fragrances;27 and moisturizers or emollients.29 The skin barriers could be creams, ointments, pastes, and sprays.2,10,30 There were seven articles reporting skin barrier products. Some authors reported only ingredients contained in the products,26,27,29 but others gave the commercial names of the products.1,10,25,28

The authors did not always indicate the quantity that was to be applied for treatment or prevention. However, some reported the frequency and duration of use, such as at every episode of incontinence, three time a day (as needed), or applied for 14 days.26 The authors recommended that the barrier products might be of concern because they could block the pores of the incontinence pads and prevent absorption of moisture.2 Corcoran and Woodward (2013) reported that zinc oxide was the most effective in preventing skin irritation;26 however, Parnham, Copson and Loban, (2020) pointed out that spray films were the strongest recommended product because they dried quickly on the skin surface and reduced the risk of skin tearing on dressing removal.10

Body Positioning

Body positioning is a method to decrease the surface area of skin irritation. The purpose of this method for IAD prevention and care (decreasing area of irritation and promoting air flow) differs from preventing pressure ulcers (decreasing pressure force on buttocks). One review showed that body positioning can be used to prevent IAD. Iamma (2017) recommended placing the person on either the right or left side instead of on the back to prevent and decrease the severity of IAD.27 These positions could be used to decrease the area of skin contact from urine and feces, which are the major causes of chemical irritation that induce IAD occurrence and severity progression.

Nutrition Promotion

Tissue recovery is faster when supported by nutrient-rich sources, especially protein. Only one article reported that nutrition can be a significant factor to prevent IAD and promote recovery from IAD. Kliangprom and Putivanit (2017) recommended that foods high in protein should be promoted to both prevent patients from IAD and recover patients who already had IAD for faster wound healing.28

Health Education and Training

Health education is one strategy for training and implementing health promotion and disease prevention programs, such as IAD. Training refers to the teaching and learning activities necessary to help participants apply the requisite knowledge, skills, abilities, and attitudes needed to prevent IAD and care for those patients. The essentials of IAD health education and training was found in two articles. Two authors strongly recommended that persons who give care to older adults should be educated and trained about skin care.2,8 These should include staff, patients, and caregivers. The staff and caregivers are not only positioned to address the issues but also are well placed to observe and prevent recurrence of IAD.2

Outcomes Evaluation

Outcome evaluation is the last process after implementing prevention and care strategies for IAD patients. It should be used to confirm goal achievement and guide what the next steps that should be taken. The importance of outcome evaluation processes were found in six articles.1,10,24–26,28 Based on the specific purposes of the articles and the variety of outcomes that were studied, three categories of outcome evaluation were identified: use of statistical measures, medical indicators, and research instruments. Outcomes could be evaluated by using statistical measures, such as incidence and prevalence rates of IAD; medical indicators, such as stratum corneum hydration and skin pH surface; and research instrument evaluation, such as Incontinence Associated Dermatitis and its Severity Instrument (IADS) and Ghent Global IAD Categorization Tool (GLOBIAD). Using these methods of outcome evaluation, researchers chose the following times to measure the outcome: at 6 hours,26 14 days,10,25 and at 24 and 49 days10 after initiating their interventions. However, not all authors indicated the timing of an evaluation.

Outcomes

The outcome is the result or effect of an action, situation, or event. This includes something that follows as a result or consequence after completing interventions or strategies for the prevention of IAD and care of those patients. Five studies reported outcomes after implementing their interventions.1,10,24–26 Skin integrity, skin texture, pain, comfort and assurance of efficacy to the individual were improved after cleaning by warm water, patting the area dry, and applying LBF Barrier Cream.1 The number of patients was higher and actual recovery time was faster from IAD after using an improved apertured film plus feminine pad than the patients who used conventional products. However, moisture content and skin pH were similar in both groups.24 Skin irritation was prevented by a zinc oxide product, and hydration was promoted by the use of glycerin.26 The magnitude of erythema and skin pH was decreased, but stratum corneum hydration was increased after applying a skin barrier cream.25 Finally, healing was noticeable in the 2nd, 4th, and 7th weeks after applying Medi Derma-Pro Foam and Spray Incontinence Cleanser with the soft and disposable wipe.10

Discussion

We found that assessment was the first activity of most prevention and care strategies. Assessment is the first thing that a health care professional should do to identify risk and severity levels of IAD before developing a care plan.13 This should cover both risk and dermatitis assessments. De Meyer et al (2019) reported on 10 instruments for measuring erythema associated with IAD in all age groups.31 We found seven instruments for use in older adults. Although there is some overlap between what they reported and those we found, the seven instruments might be better suited for assessing IAD in older adults because the authors recommended, approved, and used them in this vulnerable population.

Incontinence management for urinary and fecal incontinence should be a primary focus following assessment because both are the two main causes of IAD.17 Fecal collection devices significantly reduce the incidence of IAD. Examples include anal pouch collection devices, anal pouches connected to negative-pressure suction devices, anal catheter/tube collection devices, and anal catheters/tubes connected to negative-pressure suction devices.17 A retraining Foley catheter for urine incontinence is optional. However, non-invasive strategies should always be placed as the first choice of use.2 Examples of non-invasive strategies are reviewing the patients’ toileting habits, wearing a condom catheter, using a soft pad, and putting on a diaper.2,27 Pads are more advantageous than diapers because they promote airflow and avoid chemical irritation form urine and feces.

The recommended pH cleansing agent should be between 4.0 and 6.8. A low pH has been recommended in younger populations.9,14 An acid skin pH (4–4.5) keeps the resident bacterial flora attached to the skin. Moreover, the acidic pH of the stratum corneum is considered to present an antimicrobial barrier preventing colonization.32,33 If the skin becomes more alkaline, its ability to inhibit bacterial growth is compromised.26 The pH of commercially available skin cleansers is generally about 9.0; their frequent use can strip the skin of its natural barrier.26 This can cause both IAD and secondary infection. Caregivers of older adults with IAD should be educated to select acid mantle products. Finally, different time frames were recommended for cleaning patients after an episode of incontinence. The best recommendation is within 10–15 minutes because IAD can take place when the skin becomes irritated during that period.4

Older adults are prone to skin break down because of the previously mentioned aging physiological processes. The use of both skin moisturizing and skin barrier products are strongly recommended.9,14,34,35 Specific products include zinc oxide oil, 3MTM Cavilon No Sting Barrier Film, no-rinse cleansing foam plus moisturizer, no-rinse pH-balanced liquid cleanser and barrier cream, 3MTM Cavilon DurableTM barrier cream, dimethicone, emollients, and petrolatum containing products. The superiority of one product over the other may be difficult to ascertain,26,34 although Lichterfeld-Kottner et al (2020) recommend that a lower pH product, especially 4.0, will provide better effects as a skin barrier.9 In addition, using a combination of skin moisturizer and skin barrier will provide a more desirable effect of IAD care.35

Although nutrition support and repositioning the body (turning) in bed are recommended to sustain skin integrity in older adults, they are not suggested as actions for the adult and pediatric populations.9,14,34,35 These two recommendations may be specific to older adults as part of their IAD risk factors. Body areas of irritation in older adults are larger than in the pediatric population, thus positioning in children may not significantly prevent IAD. Because over 8% of community dwelling older adults and up to 30% of hospitalized older adults experience malnutrition, nutrition support and promotion are important for cell growth and healing.36 These are the reasons why promoting nutrition and turning positioning are specific strategies for prevention and care for older adults with IAD.

Health education and training of staff, patients, and caregivers are important findings in our review of the literature. The same has been reported in the care of adults.35 Health education and training increase knowledge in learning the difference between IAD and pressure ulcers. If there is a lack of awareness of the difference in presentation and cause of the two conditions, staff and caregivers may misdiagnose and wrongly apply non-specific interventions.26,35 Education and training not only provide prevention and care for IAD, patients and caregivers help observe and report when risk factors are detected, including the early signs of IAD.2,8

Outcomes of intervention evaluation for older adults are the same as in other populations.9,14,31,34,35 Outcomes may be placed into three categories: statistical measures, medical indicators, and research instrument evaluation based on the specific purposes of the studies and assortment of outcomes. The time frame of outcome evaluation varied among the articles we reviewed, depending on the type of intervention/outcome. Unfortunately, most of the authors did not specify the best time for the appropriate evaluation. A similar conclusion about core outcomes in IAD has been reported elsewhere.35 Outcome evaluation of interventions is an area recommended for future study and exploration.

We found five articles that reported outcomes after implementing prevention and care interventions for older adults with IAD. Outcomes were skin integrity, skin texture, skin pH, skin irritation, moisture content or stratum corneum hydration, magnitude of erythema, the number of recovered patients, time of recovery, pain, comfort, and assurance of efficacy to the individual. Major outcomes in our review focused on medical indicators. However, the studies of adult patients included in a systematic review by Beeckman et al (2016) focused on statistical measures, such as the number of participants with and without IAD, and the cost of treatment and care.12 Finally, we found the same limitations and conclusions that Beeckman et al (2016) drew in their research. The available evidence on prevention and care, especially for skin cleansing, skin moisturizing, and skin barrier products, is limited. More research needs to be conducted to make more informed conclusions.

Strengths and Limitations

This systematic review included recommendations from international studies and perspectives. The articles provided specific prevention and care strategies applicable to the older population. However, it was difficult for us to conclude which interventions or medical products had superior effectiveness because of the heterogeneity of measurement tools, designs, outcomes, time points, and interventions. Moreover, most of the articles did not indicate how to apply the products, the quantity to be applied, the frequency of application, and when to apply. Therefore, implications for practice are quite limited.

Conclusions and Recommendations

We searched eight databases for empirical articles and applied a narrative method to report findings about the prevention and care of IAD. Out of 17,631 initial articles, 11 articles were selected for final review. Specific prevention and care strategies for older adults with IAD included using specific assessment tools, applying skin cleansing pH from 4.0 to 6.8, body positioning, and promoting food with high protein. Other strategies we identified were similar to those used with adult patients. Health care professionals and others who care for older adults should be educated about the prevention and care of IAD so that they are able to provide specific interventions and quality of care for this population. If a commercial product is used, an acid pH should be determined, and the instructions should be followed carefully. Research needs to be conducted to establish the most effective cleanser, skin moisturizer, and skin barrier products on the market. For this, RCTs on product effectiveness for prevention and care of IAD among older adults are highly recommended. Finally, because evaluation is an important part of prevention and care for IAD, the questions of when and how to evaluate the interventions’ outcomes require special consideration and attention in future research.

Acknowledgments

We thank those who contributed to this systematic review for their collaboration and support. Special appreciation is extended to Dr. Andrew C. Mills for reviewing early drafts.

Funding Statement

Grant Information: this work was financially supported by the Research and Training Center of Enhancing Quality of Life of Working Age People (Grant Number QWFM64-003), Research Cluster in Gerontological Nursing, Faculty of Nursing, Khon Kaen University (Grant Number FM64-1-2-2-3) and Research and Graduate Studies, Khon Kaen University (Grant Number GS64-1-2-2-3). Appreciation is extended to these research cluster and training centers for making the research possible.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest for this work and declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- 1.Beldon P. Incontinence-associated dermatitis: protecting the older person. Br J Nurs. 2012;21(7):402–407. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2012.21.7.402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lumbers M. How to manage incontinence-associated dermatitis in older adults. British Journal of Community Nursing. 2019;24(7):332–337. doi: 10.12968/bjcn.2019.24.7.332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gray M, Beeckman D, Bliss DZ, et al. Incontinence associated dermatitis: a comprehensive review and update. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2012;39(1):61–74. doi: 10.1097/WON.0b013e31823fe246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nix D, Haugen V. Prevention and management of incontinence-associated dermatitis. Drugs Aging. 2010;27(6):491–496. doi: 10.2165/11315950-000000000-00000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leblebiciglu Y, Khorshid L, Ondogan Z, Ozturk G. Development of a new incontinence containment product and an investigation of its effect on perineal dermatitis in patients with fecal incontinence: a pilot study in women. Wound Manag Prev. 2019;65(1):20–27. doi: 10.25270/WMP/2019.1.2027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hödl M, Blanař V, Amir Y, Lohrmann C. Association between incontinence, incontinence-associated dermatitis and pressure injuries: a multisite study among hospitalized patients 65 years or older. Australas J Dermatol. 2020;61(1):e144–e146. doi: 10.1111/ajd.13163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gray M, Giuliano KK. Incontinence-associated dermatitis, characteristics and relationship to pressure Injury: a multisite epidemiologic analysis. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2018;45(1):63–67. doi: 10.1097/WON.0000000000000390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holloway S. Skin considerations for older adults with wounds. Br J Community Nurs. 2019;24(Suppl 6):S15–S19. doi: 10.12968/bjcn.2019.24.Sup6.S15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lichterfeld-Kottner A, El Genedy M, Lahmann N, Blume-Peytavi U, Büscher A, Kottner J. Maintaining skin integrity in the aged: a systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2020;103:1–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2019.103509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parnham A, Copson D, Loban T. Moisture-associated skin damage: causes and an overview of assessment, classification and management. Br J Nurs. 2020;29(12):S30–S37. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2020.29.12.S30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Raepsaet C, Fourie A, Hecke AV, Verhaeghe S, Beeckman D. Management of incontinence‐associated dermatitis: a systematic review of monetary data. Int Wound J. 2021;18(1):79–94. doi: 10.1111/iwj.13496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beeckman D, Damme NV, Schoonhoven L, et al. Interventions for preventing and treating incontinence-associated dermatitis in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;11(11):CD011627. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011627.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Geraldo MS, Cleber AR, Flávio DM, Ronaldo AJ, Rosimar Aparecida AD, Amanda Gabriele T. Algorithms for prevention and treatment of incontinence-associated dermatitis. Revista Estima. 2020;18:1–10. doi: 10.30886/estima.v18.837_IN [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lim YSL, Carville K. Prevention and management of incontinence-associated dermatitis in the pediatric population. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2019;46(1):30–37. doi: 10.1097/WON.0000000000000490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pather P, Dip G, Cert G, Hines S. Best practice nursing care for ICU patients with incontinence-associated dermatitis and skin complications resulting from fecal incontinence and diarrhea. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2016;14:15–23. doi: 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Van Wissen K, Blanchard D. Preventing and treating incontinence-associated dermatitis in adults. Br J Community Nurs. 2019;24(1):32–33. doi: 10.12968/bjcn.2019.24.1.32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yan Z, Leng M, Guo J, Duan J, Zhiwen W. The effectiveness of faecal collection devices in preventing incontinence-associated dermatitis in critically ill patients with faecal incontinence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Aust Crit Care. 2021;34(1):103–112. doi: 10.1016/j.aucc.2020.04.152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aromataris E, Munn Z. Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer’s Manual. Adelaide: Joanna Briggs Institute; [cited 20 February 2018.]. 2017. Available from: https://reviewersmanual.joannabriggs.org/. Accessed 4 October 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aromataris E, Fernandez R, Godfrey C, Holly C, Kahlil H, Tungpunkom P. Summarizing systematic reviews: methodological development, conduct and reporting of an umbrella review approach. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13(3):132–140. doi: 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tufanaru C, Munn Z, Aromataris E, Campbell J, Hopp L. Chapter 3: systematic reviews of effectiveness. Aromataris E, Munn Z, editors. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis: 2020. Available from https://synthesismanual.jbi.global. Accessed October 4, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 21.McArthur A, Klugarova J, Yan H, Florescu S. Innovations in the systematic review of text and opinion. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13(3):188–195. doi: 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moola S, Munn Z, Tufanaru C, et al. Chapter 7: systematic reviews of etiology and risk. Aromataris E, Munn Z, editors. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis: 2020. Available from https://synthesismanual.jbi.global. Accessed October 4, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G, Oxman A, GRADE Handbook; 2013. Available from: https://gdt.gradepro.org/app/handbook/handbook.html?fbclid=IwAR04O97yyXIeJA1u6kyzMgweSVpFcA0uJsIpWXRwzKQhPBlBJ9aX3u7UN94. Accessed October 4, 2021.

- 24.Sugama J, Sanada H, Shigeta Y, Nakagami G, Konya C. Efficacy of an improved absorbent pad on incontinence-associated dermatitis in older women: cluster randomized controlled trial. BMC Geriatr. 2012;12(22):1–7. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-12-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kon Y, Ichikawa-Shigeta Y, Luchi T, et al. Effects of a skin barrier cream on management of incontinence-associated dermatitis in older women. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2017;44(5):481–486. doi: 10.1097/WON.0000000000000353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Corcoran E, Woodward S. Incontinence-associated dermatitis in the elderly: treatment option. Br J Nurs. 2013;22(8):1234–1239. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2013.22.8.450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Iamma W. Knowledge for caregivers: skin care for older persons with bowel incontinence. Thai J Nurs Midwifery Pract. 2017;4(1):55–58. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kliangprom J, Putivanit S. Prevention of skin breakdown in the older person. South Coll Netw J Nurs Public Health. 2017;4(3):249–258. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yates A. Incontinence-associated dermatitis in older people: prevention and management. Br J Community Nurs. 2018a;23(5):218–224. doi: 10.12968/bjcn.2018.23.5.218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yates A. Preventing skin damage and incontinence-associated dermatitis in older people. Br J Nurs. 2018b;27(2):76–77. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2018.27.2.76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.De Meyer D, Gabriel S, Kottner J, et al. Outcome measurement instruments for erythema associated with incontinence‐associated dermatitis: systematic review. J Adv Nurs. 2019;75:2393–2417. doi: 10.1111/jan.14102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lambers H, Piessens S, Bloem A, Pronk H, Finkel P. Natural skin surface pH is on average below 5, which is beneficial for its resident flora. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2006;28(5):359–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-2494.2006.00344.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Proksch E. pH in nature, humans and skin. J Dermatol. 2018;45:1044–1052. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.14489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Priscilla P, Sonia H, Kate K, Fiona C. Effectiveness of topical skin products in the treatment and prevention of incontinence-associated dermatitis: a systematic review. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2017;15:1473–1496. doi: 10.11124/JBISRIR-2016-003015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Van den Bussche K, Kottner J, Beele H, et al. Core outcome domains in incontinence-associated dermatitis research. J Adv Nurs. 2018;74:1605–1617. doi: 10.1111/jan.13562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Griffin A, O’Neill A, O’Connor M, Ryan D, Tierney A, Galvin R. The prevalence of malnutrition and impact on patient outcomes among older adults presenting at an Irish emergency department: a secondary analysis of the OPTI-MEND trial. BMC Geriatr. 2020;20:455. doi: 10.1186/s12877-020-01852-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]