Abstract

Background

The effect of beta-blockade (BB) on response to vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) has not been reported in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF). In the ANTHEM-HF Study, 60 patients received chronic cervical VNS. Background pharmacological therapy remained unchanged during the study, and VNS intensity was stable once up-titrated. Significant improvement from baseline occurred in resting 24-hour heart rate (HR), 24-hour HR variability (SDNN), left ventricular EF (LVEF), 6-minute walk distance (6MWD), and quality of life (MLWHFS) at 6 months post-titration. We evaluated whether response to VNS was related to percentage of target BB dose (PTBBD) at baseline.

Methods

Patients were categorized by baseline PTBBD, then analyzed for changes from baseline in symptoms and function at 6 months after VNS titration.

Results

All patients received BB, either PTBBD ≥ 50 % (16 patients, 27 %; group 1) or PTBBD < 50 % (44 patients, 73 %; group 2). Heart rate, systolic blood pressure, LVEF, use of ACE/ARB, and use of MRA were similar between the two groups at baseline. Six months after up-titration, VNS reduced HR and significantly improved SDNN, LVEF, 6MWD, and MLWHFS equally in both groups.

Conclusions

In the ANTHEM-HF study, VNS responsiveness appeared to be independent of the baseline BB dose administered.

Keywords: Autonomic nervous system, Autonomic regulation therapy, Heart failure, Beta blockers, Sympathetic blockade, Vagus nerve stimulation

1. Introduction

Chronic heart failure (HF) is a syndrome that affects more than 6.2 million people in the US alone, with a worldwide prevalence expected to continue to increase significantly [1]. HF remains a leading cause of morbidity and mortality [2]. Beta-Blocker (BB) drugs are among the more effective therapies for patients with HF and reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) [3]. Despite improvements that have been brought about by these and other classes of drugs, many patients remain symptomatic and experience devastating effects on their quality of life and HFrEF continues to create a major socio-economic burden [4]. New therapies are therefore needed [5].

Numerous clinical studies have shown that patients with HFrEF have autonomic dysfunction that is associated with an increased sympathetic activity and vagal withdrawal [6], [7], [8]. Change in autonomic regulatory control leads to multiple pathophysiologic changes that have deleterious long-term consequences. Recently, novel implantable devices have been developed that deliver Autonomic Regulation Therapy (ART) via vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) [9], [10], [11]. This approach has an established safety profile for the treatment of refractory epilepsy or depression, and there is evidence of potential benefits for HFrEF through multiple cardioprotective mechanisms [12], [13], [14], [15], [16].

There is limited information in humans on the interaction between VNS and guideline directed medical therapy. In the ANTHEM-HF Study, 60 patients on optimal medical therapy for HFrEF received adjuvant chronic ART. VNS was associated with significant improvements from baseline in resting 24-hour heart rate (HR), 24-hour HR variability (SDNN), left ventricular EF (LVEF), 6-minute walk distance (6MWD) and quality of life (Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire score; MLWHFS) at 6 months after VNS titration [4]. We evaluated whether clinical response to VNS in the ANTHEM-HFrEF trial was related to the baseline beta-blocker dose, assessed as a percentage of target BB dose (PTBBD) administered at baseline.

2. Methods

The design, patient selection criteria, and safety and efficacy results of the ANTHEM-HF study have been previously described [9], [17]. The study was performed according to the Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol was approved at all sites by local ethics committees, and all patients gave written informed consent translated into local languages.

Briefly, sixty (n = 60) patients aged ≥ 18 with symptomatic HF (New York Heart Association (NYHA) class II-III) were enrolled at 10 sites over 13 months. Other inclusion criteria included LVEF ≤ 40 %, LV end-diastolic diameter ≥ 50 mm and < 80 mm, and QRS width ≤ 150 ms. Patients were also required to be capable of performing the 6-minute walk test with a measured baseline distance between 150 and 425 m and limited by symptoms of HF. Patients with confounding co-morbidities were excluded from the study. All 60 patients were in sinus rhythm at the time of enrollment, and received stable, guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT) for HF. This therapy included among others a stable dose of maximally tolerated BB therapy for at least 3 months. Patients also received stable doses of maximally tolerated angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, and spironolactone, for at least 1 month. Although medication changes during the study were permitted according to physician evaluation, no significant changes occurred during the study.

Enrolled patients were randomized 1:1 to receive VNS Therapy System implantation (Demipulse Model 103 pulse generator and PerenniaFLEX Model 304 lead; LivaNova, Houston, Texas) with lead placement either on the left or the right cervical vagus nerve based upon 1:1 randomization. The pulse generator was activated 15 ± 3 days after implantation. All patients were initially stimulated at a pulse width of 130 μsec and a pulse frequency of 10 Hz using continuous cyclic stimulation having a duty cycle comprising 14-second active [on] and 66-second inactive [off]. The duty cycle repeated itself a total of 1080 times per day. VNS was titrated during clinic visits over a 10-week titration period by systematically adjusting the stimulation parameters to a pulse frequency of 10 Hz, pulse width of 250 μsec, and target output current amplitude of up to 3.0 mA. During each titration session, the intensity of stimulation was gradually increased with a radiofrequency programmer (Model 250 programming system; LivaNova) in increments of 0.25 mA until transient acute VNS-related side effects were observed during the on-time of the duty cycle. This established a tolerance boundary for each titration session that was manifested, typically by an expiratory reflex consisting of a mild cough. Once the VNS tolerance boundary was established, the output current was reduced to ensure that the therapy could be well tolerated with no VNS-related side effects between titration sessions. At the end of the titration period, the average output current reached was 2.0 ± 0.1 mA (left VNS: 2.2 ± 0.2 mA; right VNS: 1.8 ± 0.2 mA).

For this analysis, patients were categorized into two groups according to baseline PTBBD. Group 1 (n = 16) included patients with PTDBB greater than or equal to 50 %. Group 2 (n = 44) included patients with PTDBB<50 %. Patients were then analyzed for change from baseline in both cardiac function and HF symptoms after 6 months of chronic therapy. The following measurements were made: HR, SDNN, LVEF, 6MWD and MLWHFS. The effect of VNS was calculated using a paired Student’s t-test. Data are reported as means ± standard deviation. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

All 60 randomized patients were classified as NYHA functional class II (57 %) or III (43 %) with an average LVEF of 32 ± 7 % for the study population. The etiology of the heart failure was ischemic in 75 % of patients. Median baseline NT-proBNP was 868 pg/mL (IQR 322–1,875 pg/mL). NT-proBNP tended to decrease overall in association with VNS (Median [IQR]: 851 [313, 1951] to 714 [344, 1239]; p = NS. This 16 % decrease was modest, and its non-significance was not surprising given the wide variability in NT-proBNP that is known to occur clinically and the small cohort of patients (n = 60) studied [18].All were successfully implanted with a VNS system; 100 % were receiving a stable dose of BB, 85 % were receiving an ACE inhibitor or ARB and 85 % were receiving a MRA as baseline therapy. There were no ICD or CRT devices implanted at the time of enrollment into the study and there was no significant change in HF medications during the study.

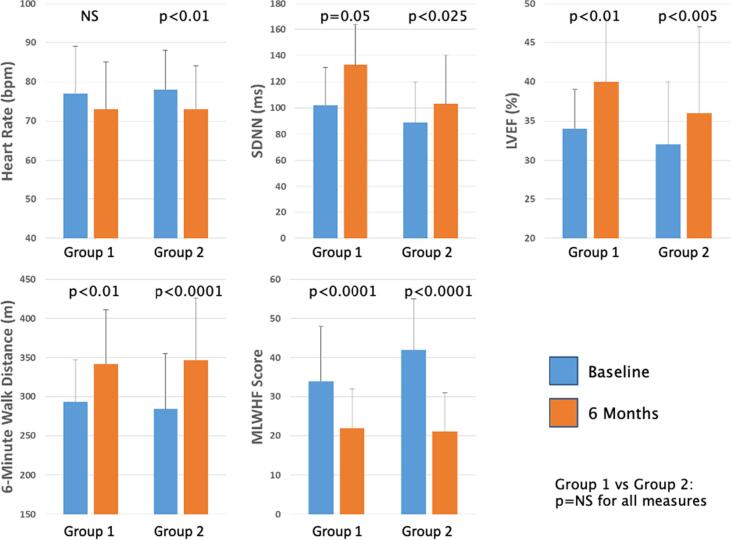

For this analysis, patients were categorized based upon receiving either PTBBD ≥ 50 % (Group 1, n = 16, 27 %) or PTBBD < 50 % (Group 2, n = 44, 73 %) at baseline [19]. The baseline characteristics of Group 1 and Group 2, including systolic blood pressure, LVEF, use of ACE/ARB and use of MRA, were not significantly different. Changes in efficacy parameters from baseline to 6 months in the two groups are summarized in Table 1 and Fig. 1. Chronic VNS was associated with significant improvements from baseline in both study groups. SDNN improved significantly in both group 1, by 31 ± 58 ms (102 ± 29 ms to 133 ± 71 ms, p < 0.05), and group 2, by 4 ± 43 ms (89 ± 31 ms to 103 ± 37 ms, p < 0.025). LVEF increased significantly, by 4 ± 9 % in both groups (34 ± 5 % to 40 ± 8 % in group 1, p < 0.01, and 32 ± 8 % to 36 ± 11 % in group 2, p < 0.005). 6MWD improved from a baseline value of 293 ± 54 m to 342 ± 69 m (Δ = 48 ± 60 m, p < 0.01) in group 1 and from 284 ± 71 m to 347 ± 79 m (Δ = 63 ± 92 m, p < 0.0001) in group 2. Quality of Life score improved significantly, by 14 ± 10 in group 1 (p < 0.0001) and 20 ± 13 in group 2 (p < 0.0001). Although HR decreased similarly in the two groups, the decrease was found to be significantly reduced in group 2 (p < 0.01) which had a larger sample size. The effect of BB on symptomatic and functional responsiveness to VNS was significant for both groups, and no significant differences were noted in any of these parameters when analyzed by baseline PTBBD.

Table 1.

|

100 %≥TDBB ≥ 50 % (Group 1, n = 16) |

STDBB < 50 % (Group 2, n = 44) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 6 months | Delta | p 1 | Baseline | 6 months | Delta | p 1 | p 2 | |

| HR | 77 ± 12 | 73 ± 12 | −3 ± 10 | NS | 78 ± 10 | 73 ± 11 | −4 ± 10 | <0.01 | NS |

| SDNN | 102 ± 29 | 133 ± 71 | 31 ± 58 | 0.05 | 89 ± 31 | 103 ± 37 | 4 ± 43 | <0.025 | NS |

| LVEF | 34 ± 5 | 40 ± 8 | 4 ± 9 | <0.01 | 32 ± 8 | 36 ± 11 | 4 ± 9 | <0.005 | NS |

| 6MWD | 293 ± 54 | 342 ± 69 | 48 ± 60 | <0.01 | 284 ± 71 | 347 ± 79 | 63 ± 92 | <0.0001 | NS |

| MLWHFS | 34 ± 14 | 22 ± 10 | −14 ± 10 | <0.0001 | 42 ± 13 | 21 ± 10 | −20 ± 13 | <0.0001 | NS |

Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation.

TDBB = target BB dose; HR = heart rate; SDNN = Standard deviation of the NN (R-R) intervals; LVEF = Left ventricular ejection fraction; 6MWD = 6-minute walk distance; MLWHFS = Minnesota living with heart failure questionnaire score.

Fig. 1.

Comparison of 6-month improvement in efficacy parameters between high-dose and low-dose BB patient groups.

4. Discussion

Several trials of ART in heart failure have yielded favorable safety results and shown some improvement in cardiac function and heart failure symptoms [20], [21], [9]. INOVATE-HF has been the largest randomized controlled study to date and was terminated due to inability to demonstrate a reduction in the primary endpoint of death or heart failure events [22]. Inadequate stimulation levels may have been responsible for the inability to demonstrate a reduction in morbidity and mortality [23] and the smaller improvements in symptoms and function that occurred in that study and in NECTAR-HF when compared to ANTHEM-HF [23].

In the ANTHEM-HF study, chronic VNS therapy was shown to be feasible, well tolerated by patients, and was associated with significant improvements in heart rate, heart rate variability, cardiac function and HF symptoms [9]. These improvements were associated with evidence of autonomic engagement, as demonstrated by subtle R-R interval changes that occurred in response to VNS onset during the VNS duty cycle [24]. This response was more pronounced with stimulation of the right vagus nerve, and there was a correlation between stimulus intensity and autonomic engagement. In contrast, no evidence of autonomic engagement was demonstrated in other ART trials that did not show improvement in cardiac function [25].

In this post-hoc analysis of ANTHEM-HF study data, VNS responsiveness was independent of baseline BB dose administered. In groups with both high and low baseline BB dose, there were significant improvement from baseline in SDNN, LVEF, 6MWD, and quality of life. These results suggest that VNS could be an effective treatment for HF patients regardless of the underlying dose of BB administered.

The findings from this analysis should be interpreted with caution. ANTHEM-HF was an uncontrolled study. It is possible that the analysis was influenced to some degree by the placebo effect or Hawthorne effect, in particular in the more subjective evaluations such as Quality of Life. These findings need to be validated in a randomized, controlled trial. The ongoing ANTHEM-HFrEF pivotal study (ClinicalTrials.gov #NCT03425422) is likely to provide further insights.

5. Conclusions

Responsiveness to VNS in ANTHEM-HF did not appear to be affected by BB dose administration. In patients with both higher and lower baseline BB doses, there were significant improvements from baseline in HR, SDNN, LVEF, 6MWD, and MLWHFS. This analysis suggests that the clinical efficacy of ART may not be dependent on the underlying dose of BB medication that is administered.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- 1.Benjamin E.J., Muntner P., Alonso A., Bittencourt M.S., Callaway C.W., Carson A.P., Chamberlain A.M., Chang A.R., Cheng S., Das S.R., Delling F.N., Djousse L., Elkind M.S.V., Ferguson J.F., Fornage M., Jordan L.C., Khan S.S., Kissela B.M., Knutson K.L., Kwan T.W., Lackland D.T., Lewis T.T., Lichtman J.H., Longenecker C.T., Loop M.S., Lutsey P.L., Martin S.S., Matsushita K., Moran A.E., Mussolino M.E., O'Flaherty M., Pandey A., Perak A.M., Rosamond W.D., Roth G.A., Sampson U.K.A., Satou G.M., Schroeder E.B., Shah S.H., Spartano N.L., Stokes A., Tirschwell D.L., Tsao C.W., Turakhia M.P., VanWagner L.B., Wilkins J.T., Wong S.S., Virani S.S. American Heart Association Council on E, Prevention Statistics C and Stroke Statistics S. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2019 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2019;139:e56–e528. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yancy C.W. Comprehensive treatment of heart failure: state-of-the-art medical therapy. Rev Cardiovasc Med. 2005;6(Suppl 2):S43–S57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Effect of metoprolol CR/XL in chronic heart failure Metoprolol CR/XL Randomised Intervention Trial in Congestive Heart Failure (MERIT-HF) Lancet. 1999;353:2001–2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schwartz P.J. Can we Modulate the Autonomic Nervous System to Improve the Life of Patients with Heart Failure? The Case of Vagal Stimulation. Arrhythm Electrophysiol Rev. 2014;3:120–122. doi: 10.15420/aer.2014.3.2.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Joffe S.W., Webster K., McManus D.D., Kiernan M.S., Lessard D., Yarzebski J., Darling C., Gore J.M., Goldberg R.J. Improved survival after heart failure: a community-based perspective. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013;2 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.113.000053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eckberg D.L., Drabinsky M., Braunwald E. Defective cardiac parasympathetic control in patients with heart disease. N Engl J Med. 1971;285:877–883. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197110142851602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brunner-La Rocca H.P., Esler M.D., Jennings G.L., Kaye D.M. Effect of cardiac sympathetic nervous activity on mode of death in congestive heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2001;22:1136–1143. doi: 10.1053/euhj.2000.2407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schwartz P.J., De Ferrari G.M. Sympathetic-parasympathetic interaction in health and disease: abnormalities and relevance in heart failure. Heart Fail Rev. 2011;16:101–107. doi: 10.1007/s10741-010-9179-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Premchand R.K., Sharma K., Mittal S., Monteiro R., Dixit S., Libbus I., DiCarlo L.A., Ardell J.L., Rector T.S., Amurthur B., KenKnight B.H., Anand I.S. Autonomic regulation therapy via left or right cervical vagus nerve stimulation in patients with chronic heart failure: results of the ANTHEM-HF trial. J Card Fail. 2014;20:808–816. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2014.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gold M.R., Van Veldhuisen D.J., Hauptman P.J., Borggrefe M., Kubo S.H., Lieberman R.A., Milasinovic G., Berman B.J., Djordjevic S., Neelagaru S., Schwartz P.J., Starling R.C., Mann D.L. Vagus Nerve Stimulation for the Treatment of Heart Failure: The INOVATE-HF Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68:149–158. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.03.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zannad F., De Ferrari G.M., Tuinenburg A.E., Wright D., Brugada J., Butter C., Klein H., Stolen C., Meyer S., Stein K.M., Ramuzat A., Schubert B., Daum D., Neuzil P., Botman C., Castel M.A., D'Onofrio A., Solomon S.D., Wold N., Ruble S.B. Chronic vagal stimulation for the treatment of low ejection fraction heart failure: results of the NEural Cardiac TherApy foR Heart Failure (NECTAR-HF) randomized controlled trial. Eur Heart J. 2015;36:425–433. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li W., Olshansky B. Inflammatory cytokines and nitric oxide in heart failure and potential modulation by vagus nerve stimulation. Heart Fail Rev. 2011;16:137–145. doi: 10.1007/s10741-010-9184-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sabbah H.N., Ilsar I., Zaretsky A., Rastogi S., Wang M., Gupta R.C. Vagus nerve stimulation in experimental heart failure. Heart Fail Rev. 2011;16:171–178. doi: 10.1007/s10741-010-9209-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shen M.J., Zipes D.P. Role of the autonomic nervous system in modulating cardiac arrhythmias. Circ Res. 2014;114:1004–1021. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.113.302549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buckley U., Shivkumar K., Ardell J.L. Autonomic Regulation Therapy in Heart Failure. Curr Heart Fail Rep. 2015;12:284–293. doi: 10.1007/s11897-015-0263-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hadaya J., Ardell J.L. Autonomic Modulation for Cardiovascular Disease. Front Physiol. 2020;11 doi: 10.3389/fphys.2020.617459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.DiCarlo L.A., Libbus I., Amurthur B., KenKnight B.H., Anand I.S. Autonomic regulation therapy for the improvement of left ventricular function and heart failure symptoms: The ANTHEM-HF Study. J Cardiac Fail. 2013;19:655–660. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2013.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anand I., Ardell J.L., Gregory D., Libbus I., DiCarlo L., Premchand R.K., Sharma K., Mittal S., Monteiro R. Baseline NT-proBNP and responsiveness to autonomic regulation therapy in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction. Int J Cardiol Heart Vasc. 2020;29 doi: 10.1016/j.ijcha.2020.100520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Premchand R.K., Sharma K., Mittal S., Monteiro R., Libbus I., Ardell J.L., Gregory D.D., KenKnight B.H., Amurthur B., DiCarlo L.A., Anand I.S. Background pharmacological therapy in the ANTHEM-HF: comparison to contemporary trials of novel heart failure therapies. ESC Heart Fail. 2019;6:1052–1056. doi: 10.1002/ehf2.12484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Ferrari G.M., Crijns H.J.G.M., Borggrefe M., Milasinovic G., Smid J., Zabel M., Gavazzi A., Sanzo A., Dennert R., Kuschyk J., Raspopovic S., Klein H., Swedberg K., Schwartz P.J. Chronic vagus nerve stimulation: a new and promising therapeutic approach for chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:847–855. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zannad F., De Ferrari G.M., Tuinenburg A.E., Wright D., Brugada J., Butter C., Klein H., Neuzil P., Botman C., Castel M.A., D'Onofrio A., De Borst G.J., Solomon S., Stein K.M., Meyer S., Schubert B., Stalsberg K., Wold N., Ruble S., Stolen C. Long Term Safety and Efficacy Results of the NEural Cardiac TherApy foR Heart Failure (NECTAR-HF) Trial. J Card Fail. 2015;21:936. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gold M., Berman B.J., Borggrefe M. The effect of vagus nerve stimulation in heart failure: primary results of the Increase of Vagal Tone in Chronic Heart Failure (INOVATE-HF) Trial. American College of Cardiology Scientific Sessions. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anand I.S., Konstam M.A., Klein H.U., Mann D.L., Ardell J.L., Gregory D.D., Massaro J.M., Libbus I., DiCarlo L.A., Udelson J.J.E., Butler J., Parker J.D., Teerlink J.R. Comparison of symptomatic and functional responses to vagus nerve stimulation in ANTHEM-HF, INOVATE-HF, and NECTAR-HF. ESC Heart Fail. 2020;7:75–83. doi: 10.1002/ehf2.12592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nearing B.D., Libbus I., Amurthur B., KenKnight B.H., Verrier R.L. Acute Autonomic Engagement Assessed by Heart Rate Dynamics During Vagus Nerve Stimulation in Patients With Heart Failure in the ANTHEM-HF Trial. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2016;27:1072–1077. doi: 10.1111/jce.13017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.De Ferrari G.M., Stolen C., Tuinenburg A.E., Wright D.J., Brugada J., Butter C., Klein H., Neuzil P., Botman C., Castel M.A., D'Onofrio A., de Borst G.J., Solomon S., Stein K.M., Schubert B., Stalsberg K., Wold N., Ruble S., Zannad F. Long-term vagal stimulation for heart failure: Eighteen month results from the NEural Cardiac TherApy foR Heart Failure (NECTAR-HF) trial. Int J Cardiol. 2017;244:229–234. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2017.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]