Abstract

In 2020, migrant farmworkers in Canada, cast as essential to sustaining the national food supply, experienced relatively high COVID-19 infection rates. Taking Southern Ontario as its focus, this article reveals how the federal government response to COVID-19 in agriculture perpetuated the effects of longstanding laws and policies requiring migrant farmworkers, circumscribed in their ability to politically mobilize on account of their institutionalized deportability, to shoulder disproportionate amounts of economic, social, and health risks. Centering the transnational character of migrant farmworkers’ renewal, it identifies meaningful interventions to limit the structural disempowerment of migrant farmworkers and the externalization of their social reproduction.

Keywords: COVID-19, Migrant farmworkers, Seasonal Agricultural Worker Program, Canada, Social reproduction

Introduction

The 2020 global pandemic brought the contradictory dynamics underlying the maintenance of Canada’s food supply chain into stark relief. As longstanding “relative labour scarcities” (Sassen, 1981) in agriculture combined with shifting consumption patterns and new limitations on international migration and trade, the Canadian government made efforts to ensure that growers and food processors maintained access to workers, many of whom are migrants. Accordingly, when Canada closed its border to non-citizens for non-essential travel in late March 2020, exemptions were made for migrant farmworkers in an effort, as Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) (2020a) proclaimed, “to safeguard the continuity of trade, commerce, health and food security for all”. But, while farms and greenhouses were declared essential, these worksites proved to be prone to COVID-19 outbreaks.

Under “normal” circumstances, to meet the demand for low-cost food, the agricultural industry relies heavily on migrant workers coming to Canada under its Temporary Foreign Worker Program (TFWP)—workers primarily from relatively low-income countries in Caribbean and Latin American countries, who labour season-to-season in jobs undesirable to citizens or permanent residents. Canada issued 56,710 temporary work permits in agriculture in 2019; the possibility of temporary labour migration being interrupted by emergency public health measures in 2020, particularly international travel restrictions, thus posed potentially devastating consequences for growers. To mitigate this risk, in 2020, the government issued 52,040 temporary work permits in agriculture, a number comparable to previous years (IRCC, 2021).1

Focusing on migrant workers participating in Canada’s TFWP in primary agriculture (i.e., labouring on fruit and vegetable farms, greenhouses, and nurseries) in Ontario, this article critiques federal government interventions responding to the COVID-19 pandemic throughout 2020–2021 to address the risks confronting migrant farmworkers2 cast as essential. The analysis illustrates how these interventions, which aimed to better protect essential workers, perpetuated longstanding tendencies requiring migrant farmworkers to shoulder a disproportionate burden of economic, social, and health risks on account of their “temporary residency status” (see, e.g. Hennebry, 2012; Rajkumar et al., 2012). In Canada, migrant farmworkers are legal yet deportable (i.e. subject to acts or threats of removal) (Vosko, 2018), circumscribing their capacity to voice workplace grievances and/or to demand fair and safe working conditions, both individually and collectively (Vosko, 2019). The heightened risks this group faced during the COVID-19 pandemic thus reflect entrenched global inequalities perpetuated by immigration and labour laws and policies insulating the receiving state from responsibility for workers’ social reproduction—the daily (e.g. provision of food, clothing, and shelter) and intergenerational (e.g. income support, workplace health and safety, and healthcare over the lifecycle) material and social supports that enable people to engage in the labour process. Often justified on the basis of national sovereignty, laws and policies governing farmworkers’ work permit conditions and (in)access to statutory rights and social entitlements can effectively externalize the costs of labour renewal, which enable migrant farmworkers to perform work year-after-year, onto migrants, their households, and sending states. Focusing attention on policy interventions (or lack thereof) in the areas of income support, housing, and workplace health and safety during the pandemic, this inquiry thereby confronts the ways such institutional differentiation of processes of labour renewal help to define migrant labour’s distinct role as a component of the labour supply, namely, to address a “shortage” of structurally disempowered low-wage temporary labour in high-income receiving states (Sassen, 1981).

The disproportionately high rates of COVID-19 transmission and related illness in Canadian agriculture illustrate boldly that policies and practices fostering the externalization of workers’ labour renewal are indefensible. As on-farm worksites became a hotspot for COVID-19 outbreaks in Southern Ontario, the degree to which migrant workers, located in an industry characterized by high rates of work-related injury and illness and high levels of employer control, are made powerless (Burawoy, 1976) captured public attention. In this context, protective measures and guidelines proved insufficient and transitory, and the corresponding need for meaningful policy interventions acknowledging how Canada’s migration programs structurally disempower migrant workers and limit the externalization of the costs of migrant workers’ labour renewal could not be ignored. Centering workers’ efforts to assert their agency and demand greater accountability, despite the risks, thereby underscores the importance of thoroughgoing changes to laws and policies, emanating initially from the receiving state, directed towards deterritorializing (Mundlak, 2009) supports for labour renewal to ensure more equitable labour practices in agriculture.

Advancing these contentions, the ensuing investigation unfolds in five parts. To set the context for this case study, section one describes Canada’s TFWPs in agriculture, focusing on the key features of the Seasonal Agricultural Worker Program (SAWP) that foster precariousness and heighten health and safety risks among workers participating in the program, well documented by scholars prior to the pandemic. Section two introduces our analytic framework, rooted in a feminist political economy of labour migration that views migration as central to processes of social reproduction on a global scale—internationalized processes that involve the externalization of labour renewal onto migrant workers, their families and communities, and sending states. Applying this lens, section three assesses government policies addressing the threat of disruptions to agricultural production and hence the national food supply, especially federal guidelines seeking to maintain on-farm production while circumventing COVID-19 transmission and outbreaks. To develop this assessment, it probes the nature and extent of on-farm outbreaks occurring prior to and alongside the issuance of federal guidelines in Southern Ontario and evaluates their efficacy in three crucial areas of migrant worker protection: income support, housing, and workplace health and safety. While the socioeconomic costs of labour renewal are notoriously difficult to quantify, the concrete effects of inadequate protections for migrant farmworkers, which gained unprecedented public attention during the pandemic, were starkly revealed. On the basis of this evaluation, and centering the demands of Canada’s migrant justice movement, section four identifies principles and policy options aimed at circumventing the externalization of labour renewal among migrant farmworkers to strengthen worker protection and augment agency.

Before proceeding, a brief note on method: this investigation draws on documentary analysis of government policies, particularly federal guidelines, directed at migrant farmworkers issued in response to the first stage of the COVID-19 crisis as well as submissions to and minutes of board meetings of local public health units. Analysis of two legal cases heard by Ontario courts addressing the protection of migrant farmworkers during the pandemic was also undertaken (Schuyler Farms Limited v. Dr. Nesathurai, ONSC, 2020; Flores Flores v. Scotlynn Sweetpac Growers Inc., OLRB, 2020). To supplement these methods, statistical analysis, drawing on customized data requests from Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) and publicly accessible data from Public Health Ontario also informs the profile of Canada’s 2020 temporary migrant labour workforce, illustrating trends in entries, source country concentration, and rates of transmission.

This investigation also draws on an extensive survey of Canadian-based reporting on policy developments and on on-farm outbreaks.3 Prior to the pandemic, the urgent need for greater protections for migrant farmworkers received sporadic attention at best in the mainstream media (Marsden et al., 2021). As Southern Ontario farms became a hotspot for COVID-19 outbreaks, content analysis of media reporting revealed that the life and death implications of poor working conditions in agriculture reached a flashpoint in public discourse with a surge in media attention directed at the insufficiency of policy interventions in producing meaningful protections for essential migrant farmworkers. This media attention also offered a rare window into the concrete effects of the externalization of the socioeconomic costs of migrant farmworkers’ labour renewal.

With regard to the empirics engaged, a caveat is in order: this article was written at the height of the 2020–2021 global pandemic as knowledge about the virus and the effects of different public health interventions was rapidly shifting.4 Given the situatedness and partiality of knowledge5 about the virus at the time of writing, this analysis of COVID-19-related federal guidelines and interventions aims to identify continuities with and departures from past policy practices, which tend to limit Canada’s economic and social responsibility for migrant farmworkers. It is on this basis that it advances focused policy alternatives that aim to hold economic beneficiaries of migrant farmworkers’ labour to greater account both during and beyond the global pandemic.

Background: Canada’s TFWPs in Agriculture

Canadian agriculture relies on racialized workers migrating under highly restrictive conditions rooted in settler colonial and imperial dynamics shaping Canada’s financial and political ties to, and extraction of resources and labour from, relatively low-income source countries, especially Caribbean and Latin American countries, which represent the principal sources for TFWPs (André, 1990; Satzewich, 1993; Smith, 2015; Chartrand & Vosko, 2020). Migrant workers engaged in Canadian agriculture thereby emigrate from contexts in which capacities to engage in sustainable forms of social reproduction, including the production and purchase of food, is circumvented by ongoing processes of land, resource, and labour expropriation (Sassen, 1981, 68)—processes that place significant pressure on workers to join the global labour force. They thus habitually migrate to perform essential work (e.g. preparation of fields, application of pesticides, fertilization, irrigation and harvesting, etc.), often at considerable risk to their own health and well-being.

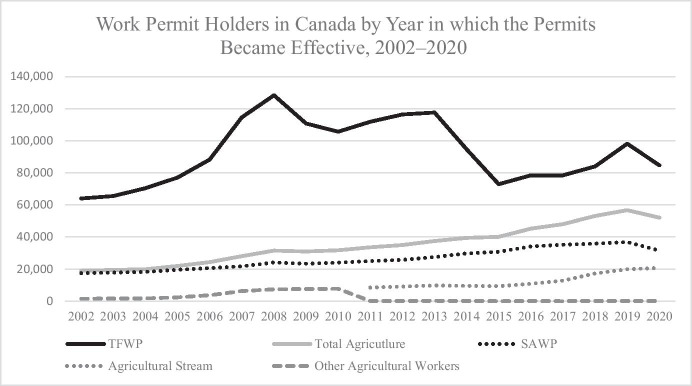

Legally authorized migrant farmworkers enter Canada principally through two subprograms of the TFWP—the Seasonal Agricultural Worker Program (SAWP) and the Agricultural Stream. After growing significantly in the early 2000s, the number of TFWP work permit holders contracted in the mid-2010s, while Canada’s less regulated International Mobility Program expanded (Vosko, 2020a, b). However, as Fig. 1 shows, even though the TFWP shrunk in this period, its most restrictive subprograms—the SAWP and the Agriculture Stream—grew slightly and represented a significant proportion of the TFWP.

Fig. 1.

Work Permit Holders in Canada by Year in which the Permits Became Effective, 2002–2020.

Source: IRCC, 2021

The SAWP is Canada’s largest and most longstanding temporary migrant worker program, operating without interruption since 1966 to meet agricultural employers’ need for low-wage, flexible labour on a seasonal basis. It provides for circular or rotational migration (i.e. repeated migration experiences, often on a seasonal basis (see Wickramasekara, 2011) and functions through agreements between the governments of Canada and Mexico and Caribbean states. These bilateral agreements set out the terms and conditions under which migrant farmworkers drawn from participating countries migrate to Canada temporarily. They also place the SAWP firmly in the federal jurisdiction, although jurisdictional distinctions and overlaps persist. For instance, while the federal government has primacy over immigration and negotiates MOUs and standard employment contracts with sending states, the provinces have the power to enact and enforce labour laws (except for workers falling in the federal jurisdiction) as well as policies applicable to (im)migrants, and municipalities implement public health measures; this patchwork contributes to gaps in protections for and access to rights among migrant workers.

SAWP participants’ conditions of entry produce precarious migration statuses (Goldring & Landolt, 2011) and compromise their security of presence. Work permits provided under the SAWP allow for a maximum 8-month stay and are employer-tied, enabling the grower to terminate and effectively repatriate workers prior to the expiration of their work permits if insufficient work is available or for other reasons (e.g. illness or injury). While in Canada, SAWP participants are deprived of the capacity to circulate freely in the labour force and constrained in their capacity to transfer employers (see, e.g. ESDC, 2021a, XV 1–3). Such work permit conditions heighten migrant farmworkers’ deportability—a social condition encompassing threats and acts of removal (Vosko, 2019)—that serves, in this instance, to discourage migrant workers from voicing grievances, making individual or collective demands, or engaging in any behaviour that might characterize them as “trouble-makers” (Binford, 2013).

Amplifying this insecurity, migrant farmworkers join an already precarious agricultural labour force in Canada. This precariousness is linked to agriculture’s longstanding treatment as a “special industry because it meets the vital human need for food” (Weiler et al., 2017, 51). While food production is a national priority, labour regulation falls within provincial jurisdiction and thus many provinces either exempt or partially exempt farmworkers (citizen and non-citizen alike) from legal protections enjoyed by other workers to keep food costs low and farming competitive (Preibisch, 2007; Barnetson, 2016). In Ontario, “farm worker exceptionalism” (Tucker, 2012) denies farmworkers’ access to statutory collective bargaining rights as well as minimum employment standards (Vosko et al., 2019). Furthermore, their access to the protections to which they are entitled is limited by an enforcement gap affecting all workers in Ontario (Vosko & Closing the Enforcement Gap Research Group, 2020).

Given the preponderance of precarious jobs in agriculture, an industry characterized by disproportionate occupational health and safety risks, bilaterally negotiated SAWP employment agreements provide farmworkers with certain formal entitlements regarding hours of work, rest periods, and wages as well as lodging, meals, and health insurance (see ESDC, 2021a, b), but these entitlements are limited or ill-enforced. For example, the SAWP requires that employers provide, free of cost (with the exception of BC), “clean, adequate living accommodations”, but the housing provided is generally “dilapidated, unsanitary, overcrowded and poorly ventilated” (Preibisch & Hennebry, 2011, 1035). It also requires employers to ensure migrant farmworkers are registered for provincial/territorial health insurance.6 Yet despite high rates of work-related illness and injury in agriculture, migrant workers often delay or do not seek the medical attention they require (Hennebry et al., 2016). Together, long working hours, limited knowledge of health insurance and/or coverage and how to access it, lack of independent modes of transportation (Barnes, 2013), social isolation (Horgan & Liinamaa, 2017), and fear of lost paid hours of work, termination, or medical repatriation (Orkin et al., 2014) create barriers to seeking healthcare. Moreover, sending states’ reliance on foreign remittances can motivate policies encouraging the export of labour constraining these state’s officials’ efforts to improve migrant workers’ conditions of work and residency and the enforcement of existing rights.7 In light of these enforcement gaps, on the receiving state side of the equation, alongside a series of regulatory and administrative changes designed to restrict employer access,8 in 2015 Canada’s federal government introduced minimalist regulations to reduce exploitation and enforce workers’ rights under the TFWP via amendments to the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act (2002). Although these measures have protective aims, they are “flawed by design” insofar as they rely on lax provincial authorities to enforce labour laws already characterized by multiple full and partial exemptions (Marsden et al., 2020). The shortcomings of such protections offered by standard employment agreements and federal regulations were boldly revealed in 2020–2021 during the COVID-19 pandemic. These shortcomings were, moreover, linked to the fact that such interventions sought to balance worker protections with employers’ interest in maintaining access to disempowered low-wage temporary labour force.

Insights on the Externalization of Social Reproduction from a Feminist Political Economy Perspective

Similar to settler colonial states, such as Australia, New Zealand, and the USA, Canada casts migrant farmworkers as essential to protecting the national food supply. At the same time, flowing from pressures to sustain competitiveness in a global economy, Canadian agriculture has come to rely on the federal government’s recruitment and retention of a workforce with limited mobility and access to rights and protections available to national citizens—a disempowered workforce that is limited in its ability to mobilize politically and essentially responsible for its own labour renewal. While the ways in which employers benefit from low-waged migrant farmworkers with limited job security is well documented in literature on the political economy of labour migration (see, e.g. Satzewich 1993; contributions to Choudry & Smith, 2016, among others), to analyse the roots and potential pathways beyond this fundamental tension, which came to the fore at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic in Canada, we employ a decidedly feminist political economy of migration lens.

Revisiting Saskia Sassen’s (1981) formative conceptualization of temporary labour migration as a process founded on the misallocation of resources necessary for sustainable processes of labour renewal provides a basis for analysing how heightened risks migrant farm workers faced during the COVID-19 pandemic are consistent with immigration and labour laws and policies insulating the receiving state from responsibility for such workers’ social reproduction. Temporary migrant work programs, including those directed at agriculture, ensure that the costs of reproducing workers are externalized to migrants’ countries of origin in two key ways: first, enforced limitations on participants’ duration of stay in the receiving country subject migrant workers to the ever-present possibility of repatriation and, second, on account of their temporary status, exclusion from full access to social and statutory benefits therein. As Sassen observes, migrant workers’ intergenerational reproduction occurs entirely in (typically low-income) sending states, and their daily maintenance takes place only partly in receiving states. Such institutional differentiation of processes of labour force reproduction and maintenance help to define migrant labour’s distinct role as a component of the labour supply, namely, to address a shortage of structurally disempowered low-wage temporary labour in high-income receiving states (Burawoy, 1976).

In referring to labour renewal—or the short-, medium-, and long-term socioeconomic processes of labour force reproduction and maintenance (i.e. social reproduction)—we rely on feminist political economy’s understanding of production for the market as intimately intertwined with social reproduction (Luxton & Bezanson, 2006, 3–4). Yet we also challenge tendency of methodological nationalism (Wimmer & Schiller, 2002) within the political economy of migration literature by reaching beyond the national scale (Katz, 2001). Prevailing analyses of the internationalization of social reproductive labour focus typically on the recruitment of racialized and feminized migrant workers, often as domestic workers, compelled to migrate abroad to perform work for receiving state citizen-workers, including middle-class women seeking to fulfil their own socially ascribed reproductive responsibilities (Arat-Koç, 2018; Castellani & Martín-Díaz, 2019; Parreñas, 2002). In applying this lens to the case of migrant farmworkers, our analysis seeks to contribute to and broaden the scope of such conceptualizations of internationalization of social reproduction: while the recruitment of a predominantly male migrant agricultural workforce to grow, harvest, and process food—activities integral to labour force renewal—does not involve the same dynamics,9 it entails the externalization of social reproduction onto predominantly racialized migrant workers, their households, and the sending state to ensure employer access to a highly flexible labour supply compelled to endure similarly undesirable conditions.

Migrant farmworkers are granted entry to Canada as economically necessary workers, but they are provided with differential access to rights and entitlements available to citizens and permanent residents (Vosko, 2020a, b). This treatment is justified, in part, by the assumption that a receiving state is not—and should not be—responsible for the socioeconomic costs of migrant workers’ renewal on account of the principle of national sovereignty (Marsden, 2012; Vosko, 2013); that is, as temporary residents, they are not entitled to the same protections or entitlements as national citizens. Yet migrant workers fill longstanding labour shortages in industries essential to the vitality of the nation, such as agriculture. In this context, high-income receiving states, such as Canada, play an integral role in shaping new and perpetuating continuous dynamics activating temporary labour migration. Paradoxically, while national borders are often assumed to interrupt and limit “exogenous” migration flows, their “selective enforcement” (Sassen, 1981) reproduces and sustains structural patterns of dependency, poverty, and underemployment in certain countries and world regions, fostering an international division of labour forged on colonial and imperial histories that produce high returns to capital and are deeply racialized (Chartrand & Vosko, 2020a, b).

Canada’s move to grant migrant farmworkers entry during a pandemic-imposed international travel ban illustrates decisively how state sovereignty and the selective enforcement of borders can be deployed to uphold the graduated hierarchy of nation states within global capitalism enabling typically high-income receiving states to benefit from temporary migrant labour, partly through externalization. Consistent with practices in recent decades, in 2020, migrant farmworkers were recruited to fill essential jobs undesirable to citizens and permanent residents, yet were denied access to supports that help to ensure sustainable processes of daily and long-term labour renewal. The consequences of this externalization surfaced starkly in the face of the escalating global pandemic, as the federal policy response to COVID-19 provided only partial and temporary relief to such longstanding problems confronting the so-called essential migrant farm workers.

Evaluating the Efficacy of Guidelines Directed at Agricultural Workplaces Engaging Migrants during the COVID-19 Pandemic: the Need for More Effective Interventions

On March 27, 2020, at the dawn of the global pandemic, Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC), Canada’s federal labour department, outlined temporary guidelines to which employers of migrant farmworkers were to adhere. In attempt to navigate the complex jurisdictional terrain at the nexus of labour and immigration policy surrounding the engagement of workers under the TFWP, including migrant farmworkers, these guidelines suggested that employers provide workers arriving in Canada with accessible information about COVID-19 and enable them to self-isolate for 14 days upon arrival. During their isolation period, employers of migrant farmworkers were to compensate employees for 30 h a week, at the hourly rate of pay stipulated contractually (ESDC, 2020a). The federal guidelines also indicated that employers could not authorize workers to work during the quarantine period, regardless of the nature of the work available (i.e. tasks otherwise presumed to be acceptable during self-isolation, such as administrative tasks, were not to be performed).10 Further guidance, issued by ESDC for employer-provided housing, included provision of separate housing for self-isolating and non-self-isolating workers. Simultaneously, federal guidelines noted that shared accommodations must allow for physical distancing, indicating, for example, that beds “must be at least two metres apart” and that common spaces must be cleaned and disinfected on a regular basis (ESDC, 2020a, s. 11). To support farmers, fish harvesters, and all food production and processing employers engaging migrant workers, the federal government announced that each employer was eligible to receive $1500 per migrant farmworker subject to self-isolation upon arrival—a subsidy to be used to cover wages or costs of accommodations during this period (AAFC, 2020). The federal government also provided $252 million to support farmers, food businesses, and food processors to address food supply chain interruptions and product surpluses brought about by COVID-19, along with a $200-million expansion of borrowing capacity in the sector.

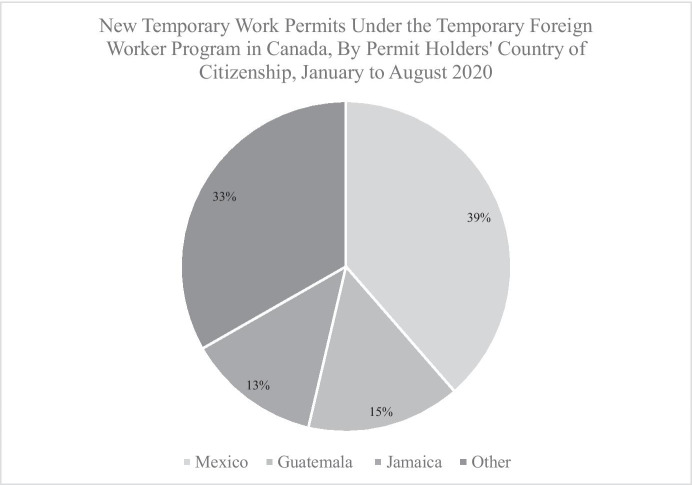

Alongside these financial interventions, selective border enforcement during the pandemic meant that by summer’s end 2020 work permit holders in agriculture received nearly 70% of all permits issued under the TFWP, compared with 58% in 2019 (IRCC, 2020a). This dramatic shift towards migrant work in agriculture had a notable impact on the TFWP’s top source countries; while migrants from Latin American and Caribbean countries comprised over 50% of those enrolled in the TFWP in 2018 (Chartrand & Vosko, 2020), workers from Mexico, Jamaica, and Guatemala held over 66% of new TFWP work permits by August 2020 (see Fig. 2), underscoring Canada’s deep dependence upon temporary labour migration forged on colonial and imperial histories that produce high returns to capital and are deeply racialized.

Fig. 2.

New Temporary Work Permits under the Temporary Foreign Worker Program in Canada by Permit Holders’ Country of Citizenship, January to August 2020.

Source: IRCC, 2020b

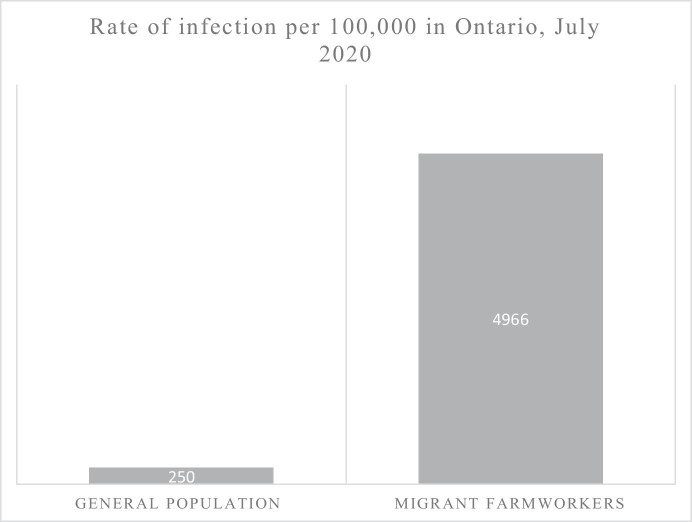

As the growing season progressed, deficiencies in addressing heightened risks to farmworkers’ health and safety became apparent. Although estimates vary by source, over 1000 migrant farmworkers in Ontario tested positive for COVID-19 between April and July 2020.11 Thus, while Ontario documented 36594 cases by July 2020 (i.e. 250 per 100000) (Detsky and Bogoch 2020), the rate of infection among migrant farmworkers, 20,015 of whom entered Ontario during the spring and summer growing season, was approximately 4996 cases per 100000 people (Fig. 3). Three workers from Mexico died from the virus in 2020. Bonifacio Eugenio-Romero, a 31-year-old migrant worker, died of COVID-19 complications in Windsor-Essex on May 30, 2020, just 30 min after receiving delayed medical treatment. Twenty-four year-old Rogelio Muñoz died in an Essex County hospital in early June. And Juan Lopez Chaparro, a 55-year-old father of four, died on June 18, 2020 in a London Ontario hospital after fighting COVID-19 for 3 weeks.12 Highlighting the scale of outbreaks on individual Southern Ontario farms, data from Ontario’s Workplace Safety and Insurance Board reveals that the farms with the largest outbreaks filed between 100 and 200 lost time claims related to COVID-19 in 2020 (WSIB 2021).13 Outbreaks on farms continued throughout the shoulder and into the 2021 season and by June 26, 2021, Public Health Ontario (2021) documented 3056 positive COVID-19 cases associated with on-farm outbreaks (cumulative since April 2020). Between March and June 2021, 5 workers died during the mandatory quarantine period upon arrival in Ontario, at least one of which, Fausto Ramirez Plazas, from Mexico, from complications arising from COVID-19, which he contracted while quarantining upon arrival in Canada (MWAC, 2020).14

Fig. 3.

Rate of Infection per 100,000 in Ontario, July 2020

In this context, the social costs of externalizing migrant workers’ labour renewal became visible and the federal guidelines came under scrutiny. The policy response to COVID-19 provided partial temporary solutions to problems that are by no means temporary—namely, well-established policies and practices, often codified in intergovernmental agreements, that externalize migrant farmworkers labour renewal even though they undertake essential jobs undesirable to nationals, typically on an ongoing (albeit seasonal) basis. Prompted by the ongoing threat of contracting COVID-19 while in Canada, some workers shared their concerns about conditions of work and health with the media, community groups, and unions, even though such actions heightened risks of termination of employment (typically prompting repatriation). As the unjust social, economic, and health risks migrant workers’ shoulder was centred in public discourse, longstanding demands to expand access to income support, develop and implement minimum standards in temporary housing, and to bolster workplace health and safety by limiting employer reprisals gained new traction, revealing the shortcomings of the federal government’s guidelines and highlighting the potential and need for more effective interventions (Fig. 3).

Income Support: Expanding Access?

In the Spring of 2020, as migrant farmworkers started to arrive in Canada, federal guidelines required them to self-isolate for 2 weeks to limit the risks of transmission associated with international travel. To account for the resulting loss of wages, dramatic in a contract of duration, the federal government mandated and subsidized income replacement for migrant farmworkers during this 14-day period. The introduction of quarantine pay for migrant workers is a significant protective measure that offered migrant farmworkers, typically excluded from short- and long-term income supports, with temporary income security in a moment characterized by unprecedented uncertainty.

Illustrating the limitations of this quarantine requirement and subsidy, however, some employers mistakenly required migrant workers to reimburse them for quarantine pay in the form of future wages,15 allowing employers to extract greater profit by squeezing workers’ income supports and wages. Meanwhile, though migrant workers were ultimately technically entitled to the Canadian Emergency Relief Benefit—an income support for anyone directly affected by COVID-19—prior income requirements and other eligibility criteria that assumed recipients to be citizens made it inaccessible to many. Language and literacy barriers also circumvented workers’ capacity to access this income support before and after the mandatory self-isolation period.

The shortcomings of federal government income support in response to COVID-19 reflect longstanding patterns. For instance, migrant farmworkers contribute to Canada’s unemployment insurance system, known as Employment Insurance (EI), and they are technically entitled to its suite of special benefits (i.e. sickness, compassionate/caregivers’, and parental benefits), but requirements for proof of an ongoing work permit and a functional social insurance number (SIN), together with qualifying requirements tied to duration of employment, often make them ineligible for even these limited benefits as well as for the regular EI benefits to which they contribute. Moreover, prior to the pandemic, workers’ low wages were already squeezed by employers (e.g. employers can deduct costs of utilities, food, insurance, and travel as well as housing in British Columbia and they are often exempt from provincial employment standards legislation governing entitlements such as overtime pay); the federal government (e.g. recall that contributions to EI are mandatory yet most regular and many special benefits are inaccessible to closed work permit holders); and sending states (e.g. Jamaican SAWP participants are required to provide a portion of their wages back to their government to cover costs associated with travel, health, and administrative services16 (ESDC, 2020a)). Additionally, SAWP recruitment policies prioritize workers with dependents to ensure workers’ annual return to countries of origin; many participants’ families thus rely on remittances to meet basic needs (McLaughlin, 2010; Wells et al., 2014). Thus, unexpected interruptions in workers’ wages can have far-reaching consequences for transnational families, compelling some to labour under unsafe and/or unsanctioned conditions— for example, during an on-farm COVID-19 outbreak—to avoid loss of income.

While the federal government’s efforts to mandate and subsidize income supports for migrant workers that lost income in quarantine was a noteworthy step, it failed to acknowledge farmworkers’ need for income supports both during and at the conclusion of their seasonal employment contracts. Exemplifying this limitation, in December 2020, SAWP workers from Trinidad and Tobago, stranded in Canada due to travel restrictions, were initially unable to access EI despite being physically present in Canada after their contracts came to an end. Initial rejection letters from ESDC deemed these workers ineligible for EI on account of not being “ready and available for work” because of their employer-specific work permits, which prevent migrant farmworkers from seeking employment elsewhere (Keung, 2020). In March 2020, Trinidad and Tobago closed its borders to all international flights due to the COVID-19 pandemic, but 505 essential Trinidadian workers were still permitted to travel to Canada under the SAWP to fill jobs integral to the nation’s food supply (IRCC, 2020a). Yet these Trinidadian SAWP workers lost access to income in Fall 2020 when the harvest season ended until December 15, 2020—the same day SAWP workers’ employer-specific work permits expire annually—when IRCC introduced a special provision that allowed the stranded workers to apply for an open work permit, which would make them EI eligible until their departure. Prompted by extensive lobbying on the part of advocates representing migrant farmworkers’ concerns and considerable public outcry, this unprecedented (albeit exceptional) policy intervention points to the possibility for more transformative change.

Housing: Towards Decent Minimum Standards?

During the pandemic, consistent with the greater likelihood of transmission indoors, shared housing corresponded with heightened rates of transmission of COVID-19, as demonstrated by major outbreaks among workers and residents of long-term care homes in Canada and internationally (Comas-Herrera et al., 2020; Hsu et al., 2020).

Acknowledging the risks associated with shared housing, amplified by those tied to international travel, the federal government asked employers to make it possible for migrant workers to self-isolate upon arrival in Canada. The standard to which this expectation was to be met was, however, unclear given the parallel decision to conduct exclusively desk-based federal inspections of agricultural worksites and living quarters relying on photographs supplied by farmers and interviews with workers onsite as evidence (Baum & Grant, 2020b), unreliable means of assessing the presence or absence of violations, as studies of employment standards enforcement demonstrate (Vosko et al., 2019). Also absent in the federal guidelines addressing housing was any direction to employers in allocating resources, including subsidies made available to improve overcrowded and poorly ventilated accommodations.

The poor conditions of migrant farmworkers’ living accommodations are no secret; prevailing research reveals employer-provided housing to be overcrowded, unsanitary, pest-infested, lacking privacy, and in general disrepair (Díaz Mendiburo & McLaughlin, 2016; Perry, 2018; Preibisch & Otero, 2014). Moreover, when employer-provided accommodations are located on or in close proximity to the worksite, housing can blur divisions between work for wages and hours of leisure and rest in ways that heighten employer control (Perry, 2018) at the same time as reducing employer accountability to workers, many of whom they may engage seasonally on a rotational basis. Mandatory onsite housing under the SAWP (with the exception of BC) also fosters transnational dependencies without due regard to the immediate and long-term health and well-being of workers and their families. When on-farm outbreaks were reported across Southern Ontario in Spring 2020, the effects of this lack of accountability for migrant workers’ renewal became acute as the risks of community-to-farm transmission associated with over-capacity and poor-quality congregate accommodations surfaced. For instance, at Scotlynn Sweetpac Growers (Scotlynn Growers) in Haldimand-Norfolk county, workers testing positive for COVID-19 described to the Globe and Mail “overcrowded living conditions, including small bedrooms with multiple sets of bunk beds” as well as “ill workers living with healthy ones, leaky toilets, and showers that only ran hot water” (Baum & Grant, 2020a). Despite the veritable risk of repatriation that closed work permit holders face when voicing concerns and grievances, some workers anonymously shared footage of their overcrowded living quarters. For instance, national news outlets reported on a video taken by a migrant farmworker on June 16, 2020, revealing living conditions in a Windsor-Essex bunkhouse that did not allow for physical distancing: bunkbeds separated by cardboard and bedsheets positioned only a few feet apart (CBC News, 2020a, b; J4MW, 2020).

Although housing of SAWP participants falls in the federal jurisdiction, some local health units in Ontario took additional steps to curb foreseeable outbreaks linked to shared housing. For instance, at the beginning of the pandemic, Haldimand-Norfolk’s medical officer of health implemented requirements, through a Sect. 22 Order of the Health Protection and Promotion Act (1990), that no more than three workers could be housed together during the self-isolation period. However, a local employer successfully challenged the requirement, arguing that the rule would result in prohibitive costs leading to labour shortages and crop reduction, “jeopardizing food security” (Schuyler Farms Limited v Nesathurai HSARB para. 41) (2020). The Health Services Appeal and Review Board overturned the requirement in July, mandating that more than three people can safely practice physical distancing if a bunkhouse is large enough. Then, in late August, a divisional court reinstated the three-person to a bunkhouse requirement, stating that the decision to allow “larger numbers to isolate together exposes migrant farmworkers to a level of risk not tolerated for others in the community, thereby increasing the vulnerability of an already vulnerable group” (Schuyler Farms Limited v. Dr. Nesathurai ONSC, 2020 para. 88).

While in place, the three-person per bunkhouse requirement may have had positive impacts.17 Yet it neither addressed the ongoing risks of living in bunkhouses during the pandemic nor the possibility of workers contracting the virus from the larger community while abroad.18 Illustrating how migrant farmworkers’ capacity to spread the virus took priority over their own health, clear capacity restrictions after the mandatory self-isolation period were lacking in both federal and local policy contexts. This absence of direction was shaped by the misconception that migrant farmworkers were vectors of the disease,19 when the opposite was often the case: public health officials reported that the sources of the outbreak at Greenhill Produce in Chatham-Kent, for instance, were two locals (Pedro, 2020).20

The limitations of the federal interventions, together with municipal measures, call for a more a more robust approach to farmworker accommodation, broadly conceived. A 2018 independent study on employer-provided housing for migrant workers, commissioned by the federal government, found a “lack of uniformity” in housing conditions and enforcement mechanisms, highlighting the need for a “uniform national standard” (NHICC, 2018). Yet Canada still lacks a national housing standard. At the close of the 2020 growing season, in response to the mounting pressure from the migrant rights justice movement to address inadequate housing conditions for migrant farm workers, ESDC proposed minimum requirements for employer-provided accommodations for the TFWP in 2021 and launched a housing consultation, engaging provinces and territories, employers, workers, workers’ advocacy groups, and foreign partner countries (ESDC, 2020c). Minimum requirements in terms of building structure, common living spaces, sleeping quarters, and washroom, laundry, and eating facilities would no doubt represent an improvement over vague directives provided in employment contracts, but the pandemic has revealed that a more ambitious response is needed.

Workplace Health and Safety: Countering Employer Reprisals?

As COVID-19 spread rapidly within agricultural worksites, threats to workers’ workplace health and safety quickly became apparent. Yet federal guidance was limited in its directions in this vital domain. Handwashing stations were recommended, for example, but directives for ensuring that enclosed work and living spaces are well-ventilated; that tasks and work shifts are adjusted to allow for physical distancing; that shared surfaces, equipment, and tools are disinfected; and that personal protective equipment is provided were ill-enforced. Additionally, provincial enforcement of workplace health and safety during the pandemic lacked meaningful deterrence.

Exacerbating the situation, the SAWP employment contract offered minimal anti-reprisal protection for workers voicing workplace-related concerns (i.e. it exclusively deferred to the minimalist and ill-enforced provisions contained in the provincial labour laws to which the parties are to adhere). Though provincial labour laws offer protection against employer reprisal, arbitrary dismissal, typically prompting premature repatriation and often hindering future employment, is permissible under state-sanctioned employment agreements (e.g. SAWP contracts list workers’ “non-compliance, refusal to work, or any other sufficient reason” as acceptable justifications for early cessation of employment (see, e.g. ESDC, 2021a X.2)). This possibility benefits employers insofar as the threat of removal that employer-specific permit holders face not only encourages productivity at low wages but also a reluctance to voice workplace concerns (Binford 2013; Vosko 2013, 2019; Basok et al., 2014). Indeed, migrant farmworkers’ fears of removal enable employers to overlook those aspects of renewal for which they are responsible, including workers’ health and safety on the job, without concern for repercussions as it reduces the likelihood of worker complaints. Unsurprisingly, institutionalized deportability was largely unaltered by federal interventions aimed at ensuring workers’ health and safety on-the-job during the global pandemic.

While it is typically difficult to draw a decisive link between ensuring occupational health and safety and the threat of reprisal, and thereby repatriation, the pandemic thrust workers’ deportability into the spotlight. Spurred by the death of his bunkmate, Lopez Chaparro, an employee of Scotlynn Growers, was terminated after voicing workplace safety concerns anonymously to the media and his supervisor (PCLS, 2020). Given the absence of meaningful protections offered under the federally negotiated SAWP employment contract for employees facing employer reprisal, the terminated employee sought recourse through available avenues at the provincial level, most centrally, in this instance, Ontario’s Occupational Health and Safety Act (OHSA). Representing the terminated employee, who had contracted COVID-19 during an outbreak that infected 190 workers, Parkdale Community Legal Services filed a complaint with Ontario’s Labour Relations Board under Sect. 50 of OHSA. It argued that the OHSA prohibits employers from disciplining or dismissing a worker acting in compliance with or seeking its enforcement. Specifically, Parkdale Community Legal Services contended that the employee, who shared a bunkhouse apartment with approximately 12 other workers, was terminated 1 day after raising “concerns about health and safety at Scotlynn to his supervisor” (para. 53). Though the employer denied that the employee in question was dismissed, Scotlynn Growers also argued that even if the employee “was dismissed for making comments to the media, it would not engage the protections of the [OHS]Act” (Luis Gabriel Flores Flores v Scotlynn Sweetpac Growers Inc. para 35) (2020). In deciding the case, the Ontario Labour Relations Board found that the respondent, who carries the burden of proof under Sect. 50(5) of the OHSA, failed to sufficiently demonstrate that it did not act in a manner that violated the Act. It thereby ruled that the complainant had, in fact, been illegally terminated for raising health and safety concerns at the farm. Notably, such health and safety concerns—including the failure to isolate workers with COVID symptoms as well as a disregrad for masking and disinfection protocols—were formally recognized more than a year later in September, 2021, when Scotlynn was charged with 20 offences under the Occupational Health and Safety Act on the basis of an inspection led by the provincial labour ministry (Lupton 2021).21

This decision is notable because it recognizes migrant workers’ heightened dependency upon their employers for “wages, shelter, and transportation”, in finding that “reprisal can strike a far deeper wound than might otherwise occur in a traditional employer relationship”, a conclusion amplified in a global pandemic (para. 94). Still, the decision is also atypical insofar as dismissal, resulting in the termination of a closed work permit, routinely triggers immediate repatriation. In this case, the complainant was uniquely successful in challenging his arbitrary dismissal because he managed to secure temporary housing, normally inaccessible to terminated workers’ due to their employer-provided accommodation as well as legal representation prior to being deported. More typically, in June 2020, two Mexican farm workers without these options, employed on a British Columbia farm with a “no-visitor” policy were dismissed and promptly repatriated after inviting two members of a migrant support group into their employer-provided housing (Beaumont, 2020). The contrast between these two outcomes illustrates the need for interventions that not only ensure workplace health and safety but protect migrant farmworkers from reprisals when voicing health and safety concerns.

Lessons from On-Farm Outbreaks During the COVID-19 Pandemic

The magnitude of illness among migrant farmworkers in Southern Ontario, and Canada more broadly, reflects the emphasis, deeply ingrained in programs emblematic of migration management such as the SAWP, on keeping labour costs low in the interest of protecting the national food supply. It underscores the damaging immediate and long-term effects of prioritizing productivity at the expense of racialized migrant workers’ renewal. Indicative of such consequences, a significant response to the on-farm outbreaks and deaths of Mexican nationals in Ontario, came on June 15, 2020, when Mexico put a hold on sending workers to Canada, and called for the federal government’s assurance that greater protective measures would be put in place to protect its nationals labouring on farms.22 Posing a major threat to Canadian agricultural employers’ access to this group of principally SAWP participants, a highly motivated Canadian federal government responded quickly. By June 21, 2020, Mexico and Canada reached an agreement to improve “sanitary conditions” for Mexican SAWP workers and to “ensure adequate access to health, inspections and timely medical care for workers” (STPS, 2020). This agreement represented a u-turn in federal policy guidelines, including the reversal of the decision to engage in exclusively reactive desk-based inspections of on-farm housing. Subsequently, the federal government announced $58.6 million would be put towards strengthening the TFWP through direct outreach via advocacy groups, bolstering inspections, and improvements in infrastructure directed at living quarters and worksites (ESDC, 2020b). In conjunction with these efforts to strengthen protections for TFWP participants, simultaneously the Canadian federal government made efforts to enlarge the SAWP and Agricultural Stream by expanding the National Commodity List (NCL) to increase farmers’ access to migrant workers in the 2021 season. Adding seed corn, oil seed, grains, and maple syrup to the NCL means that ESDC can continue to “provide labour where it is most needed” (ESDC, 2020d).

In this expansionary context, piecemeal and short-term interventions are insufficient in addressing migrant farmworkers’ conditions of work and welfare. The global pandemic brought into clear view the inequalities shaping the tenuous interdependency of the sustainability of the national food supply, the productivity of the agricultural industry, and migrant workers’ conditions of work and residency, not only have longstanding demands for policy changes become more pressing, they are potentially more achievable.

Given this inquiry’s concern with responding to the treatment of migrant farmworkers as responsible for their own renewal (Sassen, 1981) laid bare in the COVID-19 pandemic, focused policy alternatives, informed by key principles, are required for implementation mainly by the receiving state to hold the economic beneficiaries of migrant farmworkers’ labour to greater account.

Informed by an expansive (i.e. transnational) understanding of social reproduction, three overarching principles aimed at relieving migrant farmworkers of unjust burdens of renewal and structural disempowerment (e.g. by minimizing barriers limiting worker agency), which could be embraced by the federal government in Canada, guide the articulation of these alternatives: universality in income supports (i.e. accessible to all workers regardless of citizenship status); sufficiency in accommodations (i.e. conditions that provide satisfactorily for rest, nourishment, recovery, and leisure); and security of presence (i.e. the ability to live and work without fear of deportation) (on security of presence, see Rajkumar et al., 2012).

With regard to income support, the principle of universality requires that all workers, regardless of citizenship status and duration in the receiving country, be entitled and enabled to access EI and other income-related benefits (Tucker et al., 2020). This principle seeks to reduce pressure on households encompassing workers labouring transnationally to bear the burden of labour renewal during and beyond the life of employment contracts. Its implementation would mean meaningful access to income supports in the face of illness, injury, unemployment, and other interruptions in employment, circumventing the pressure many migrant farmworkers face to suppress concerns around their personal and collective health and safety on-the-job. As an OECD report on the impact of COVID-19 on immigrants and migrants globally recommends, policymakers should ensure that “economic and employment support measures do reach migrants” and that “the contributions of migrants are not forgotten” (OECD, 2020). Accordingly, requirements such as a non-expired work permit, which can make migrant farmworkers holding employer-tied time-specific work permits ineligible for most income supports to which they are otherwise entitled, should be eliminated. The transnational character of migrant farmworkers’ labour is, as the COVID-19 pandemic has illustrated, essential to sustaining the food supply and Canadian agriculture over the long-term. Migrant farmworkers should thus be able to collect income support during and in-between contracts regardless of their geographic location, especially during periods of seasonal unemployment mandated by bilateral agreements.

With respect to accommodation, the principle of sufficiency is based on the premise that living quarters represent a space where workers are meant to rest, be nourished, and partake in leisure activities in order to return to work day-after-day. In the case of migrant farmworkers, realizing this principle entails recognizing that quality of housing, which is by no means temporary infrastructure given that farmworkers migrate seasonally year-after-year, is vital to workers’ short-, medium-, and long-term renewal. Ensuring sufficiency in housing in the Canadian case, as elsewhere, requires no less than a permanent well-enforced national housing standard. Receiving states like Canada should develop standards in this domain that, at the very least, meet the following criteria outlined by UN: security of tenure; availability of services, materials, facilities, and infrastructure (including safe drinking water, energy and space for food storage and preparation, etc.); affordability; habitability (i.e. protected against cold, damp, heat, wind, other threats to health, etc. with provision for privacy); accessibility; location (i.e. not cut off from healthcare services, grocery stores, and social facilities); and cultural adequacy (OHCHR, 2014, 3–4; for detailed recommendations, see specifically UFCW, 2020; MWH-EWG, 2020b). Additionally, receiving country government agencies, including Canada’s federal labour and immigration authorities, should mandate unannounced and regular inspections of housing, informed by confidential participation of employees protected by a firewall between housing inspectors and the Canadian Border Services Agency,23 to ensure that workers’ health is not at risk, that their standard of living can be sustained both at work and when they require recuperation from injury or illness, and that they can speak candidly about housing conditions without fear of reprisal.

Finally, to circumvent the threat of repatriation when voicing workplace grievances and/or demanding fair and safe working conditions, security of presence is essential. At the very least, making this principle meaningful entails barring dismissal without just cause during the term of an employment contract in standard employment agreements under the SAWP (Vosko, 2019, 113). Accordingly, to eliminate the need for worker-initiated complaints about termination without just cause, a proactive complaint mechanism should be triggered every time a temporary migrant worker is fired before the expiry of an employment contract (Vosko, 2019, 115). As the Migrant Worker Health-Expert Working Group, a Canada-based research group comprised of occupational health and safety practitioners and migration scholars recommended to Canadian, Mexican, and Caribbean representatives re-negotiating standard employment agreements under the SAWP, an independent tribunal could adjudicate requests for dismissal, where the burden of proof of just cause for termination rests on the employer (MWH-EWG, 2020a). More substantially, permanent status on arrival or, at a minimum, meaningful opportunities for permanent residency—a priority for many migrant farmworkers who seek to remain in receiving states long-term and reunite with their families—would bolster workers’ security of presence. Well-designed pathways to permanent residency would limit externalization of labour renewal and thwart repatriation as a means of employer retaliation, on the basis of discrimination, including against workers compelled to complain. As a bridge to these reforms, but not an end in and of itself, fully open work permits for all migrant agricultural workers would reduce barriers to voicing complaints about unsafe work and/or living conditions in the knowledge that there are exit options beyond repatriation.

Conclusion

The continued subordination of migrant farmworkers’ social reproduction to the competitive interests of Canadian agriculture is both unjust and unsustainable. While deeply reliant on migrant farmworkers, the externalization of labour renewal (including the costs of providing support during periods of unemployment and other income disriptions and of raising and training the next generation of workers) by high-income receiving states, like Canada, challenges workers, households, communities, and sending states already under stress. The COVID-19 pandemic, as it unfolded in Canada in 2020–2021, revealed greater fault lines in — and indeed serious consequences of — this externalization of labour renewal; large outbreaks interrupted production and compromised migrant farmworkers’ renewal in new ways. Policy interventions responding to, yet reaching beyond, the impacts of this pandemic must confront receiving states’ (and agricultural employers’ therein) deep reliance on disempowered workers migrating from contexts in which the ongoing ability to support workers’ renewal in the long term is circumscribed. Interventions seeking to ensure migrant workers can continue to play an essential role in agriculture should they elect to do so—a role that nationals in receiving states, such as Canada, often do not wish to undertake—must target the graduated hierarchies of nation states that structurally disempower transnational workers and allow high-income receiving states to reap unjust benefits from the recruitment of labour and resources of lower-income sending states.

Acknowledgements

We thank Heather Steel, Ella Bedard, and anonymous reviewers for the Journal of International Migration and Integration for their comments on earlier versions of this paper.

Footnotes

Simultaneously, immigration officials expedited hiring processes to move unemployed migrant workers, already present in Canada and threatened with a loss of (residency) status more quickly, approving those who had secured jobs to start working even before a work permit was issued (IRCC, 2020b).

“Temporary foreign worker” is the term applied to migrant workers recognized as “legal” (i.e. legally present) by the state insofar as they labour under Canada’s TFWP. This term has an exclusionary force, accentuated during the 2020 global pandemic when many otherwise legally present workers became “undocumented” as their work permits expired alongside the implementation of new restrictions on international travel. As such, and as we neither view the constructed categories of “illegal” and “legal” migrants as legitimate (or stable) nor accurate reflections of workers’ agency, we use the term migrant farmworkers to refer to TFWP participants labouring under its two subprograms in agriculture.

This survey, conducted from March 2020 to December 2020, encompassed national dailies and major dailies in every province, with a focus on Ontario, and covered issues tied to migrant farmworkers’ labour renewal during the pandemic, including access to income supports, housing, personal protective equipment, healthcare, food, and other services, supports, and amenities. It also included major online national news outlets as well as social media published by migrant workers’ advocacy groups.

For example, at the time of writing, knowledge about COVID-19 infection fatality rates was evolving (Brown, 2020; Ioannidis, 2021), a process that continued through to publication. So, too, was knowledge about the costs and benefits of large scale COVID-19 interventions, such as municipal or provincial/state lockdowns, with attention to other public health metrics such as psychological and social well-being (see, e.g. Lau et al., 2020; Bagus, Peña-Ramos & Sánchez-Bayón, 2021; Joffe, 2021).

On the situatedness of knowledge claims, see Haraway 1988; for two recent efforts to apply and expand this concept, see Simandan, 2019; Vosko, 2019

In Ontario, SAWP workers are entitled to provincial health insurance upon arrival (see Ontario Health Act, Recommendation 522, Sect. 1.3(2)). In jurisdictional contexts where SAWP workers are not eligible for provincial health insurance, private health insurance must be acquired, though it can be paid for through deductions from wages (ESDC, 2021a, V 2.c; VI 9).

As two illustrative examples in the Canadian context, McLaughlin (2009, 196–197) documents sending state consular officials’ role in screening workers for illnesses, including HIV, before accepting them into the program, and Vosko (2016) analyzes a 2014 legal case heard by BC’s Labour Relations Board that documents consular officials’ role in blacklisting SAWP workers involved in union organizing.

Changes included increases in application fees, introduction of an inspection regime, and restrictions on which employers can apply based on local employment conditions and occupation/sector (ESDC 2014).

On the gendered effects of the migration of predominantly male workers (including men who migrate to perform work integral to social reproduction, such as nursing) on households, communities, and labour forces in sending states, see, for example, Walton-Roberts, 2019 and Perry, 2018

In a move notable for its recognition of the need to better protect employer and time-specific work permit holders’ conditions of employment, in a 2021 update to the guidelines, ESDC added a requirement that the mandatory 14-day self-isolation period is additional to the minimum 240 h of pay specified in the SAWP contract. Additionally, the updated guidelines included a new provision barring employers from “deny[ing] assistance if the foreign worker requires the employer to assist with access to necessities of life” during the mandatory quarantine period (ESDC, 2021a, b).

On July 7, 2020, the Toronto Star reported that infected migrant farmworker count surpassed 1000 (Mojtehedzadeh 2020b), and, through a survey of local public-health units, the Globe and Mail also reported over 1000 cases among migrant farmworkers on July 13, 2020 (Baum & Grant 2020b).

Following calls for a public inquest into these deaths, the Office of the Chief Coroner launched a confidential review of migrant workers who died after contracting COVID-19, yet advocates and media characterized this review as no substitute for a much-needed public inquest (Mojtehedzadeh and Mendleson 2021).

The farms with the greatest number of claims were Scotlynn Sweetpac Growers Ltd (199); Nature Fresh Farms Inc. (195); Highline Produce Limited (171); Agriville Farms Ltd. (147); Greenhill Produce Ltd. (124)) (WSIB 2021).

Logan Grant, from Jamaica, died March 22, 2021 while in a quarantine hotel (cause of death unknown); Romario Morgan, from St. Vincent, died April 29, 2021, also while in a quarantine hotel (cause of death unknown) (MWAC 2020; Mojtehedzadeh & Keung 2021). Jose Antonio Coronado, from Mexico, died shortly after arriving in the St. Elgin, Ontario area on April 21, 2021, and an unnamed worker, from Guatemala, died in June 2021 while isolating upon arrival in Ontario (Mojtehedzadeh & Keung 2021).

For instance, in March 2020, the BC Fruit Growers’ Association issued a letter to its members erroneously suggesting that employers treat quarantine pay as an advance (MacNaull, 2020).

Moreover, in the context of the global pandemic, the government of Jamaica reportedly required SAWP participants to sign a waiver before travelling to Canada acknowledging the heightened risks of virus transmission associated with international travel and releasing this sending state from liability “for any harm, injury, loss, or damage which may arise” due to exposure to COVID-19 (Mojtehedzadeh 2020a). In requiring SAWP participants to sign an “Instrument of Release and Discharge Document”, Jamaica, reliant on remittances and invested in maintaining good standing as a sending state, limited its own liabilities further.

In a presentation to the Haldimand-Norfolk Board of Health after the decision, the county’s medical officer of health noted that, while in place, this bunkhouse restriction circumvented serious outbreaks during the self-isolation period, noting of the outbreaks reported during self-isolation periods “had an insignificant impact on the workers or the farming operation because 3 or fewer workers were isolating together” (HNHU, 2020a, 42).

For instance, after leading an unsuccessful challenge to the Haldimand-Norfolk’s housing requirement, Schuyler farms experienced an outbreak in November 2020 involving at least 13 migrant farmworkers (HNHU, 2020b).

On the relationship between pandemic management and the ideological recasting of the migrant worker as a “medical risk”, see Ye (2021)

Acknowledging the possibility of infection throughout the season, the City of Windsor opened a 125-bed isolation and recovery centre, administered by the Canadian Red Cross, a charitable organization, and funded by Public Safety Canada, for farmworkers exposed to or infected with COVID-19 in November 2020. In response to the threats of closure due to financial instability, the federal government committed 17.8 million to keep the centre open for the entirety of 2021 (PHAC, 2021).

Pointing to the limited effects of this win, however, after receiving an open work permit under the federal governments’ Open Work Permit for Vulnerable Workers program (IRCC 2021), the former Scotlynn employee, who had returned to Mexico during the winter months, told the Toronto Star that he was struggling to secure a flight back to Canada due to international travel restrictions and feared he would lose his new job commencing March 1, 2021 (Mojtehedzdeh & Keung, 2021).

While Mexico expressed confidence in the rules in place in Canada, its Ambassador characterized a lack of enforcement as the major problem, noting that “the reason why there have been infections and sadly three deaths now is because on some farms these rules are not being followed”, a notable admonishment given the sending state’s longstanding reliance on farmworkers’ remittances (CTV News, 2020a, b).

While firewall protections are necessarily limited (Anderson, 2008), an early iteration of the UN’s Compact on Migration likewise called for a firewall between immigration enforcement and social services and protections to reduce precariousness associated with status and ensure safe access to public supports (UN, 2018).

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC). (2020, April 13). Keeping Canadians and workers in the food supply chain safe. https://www.canada.ca/en/agriculture-agri-food/news/2020/04/keeping-canadians-and-workers-in-the-food-supply-chain-safe.html. Accessed 30 Dec 2020.

- Anderson B. Migrants and work-related rights. Ethics & International Affairs. 2008;22(2):199–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-7093.2008.00144.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Andre I. The genesis and persistence of the Commonwealth Caribbean Seasonal Agricultural Workers Program in Canada. Osgoode Hall LJ. 1990;28:243. [Google Scholar]

- Arat-Koç, S. (2018). Migrant and domestic and care workers: Unfree labour, crises of social reproduction and the unsustainability of life under ‘vagabond capitalism.’ Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Bagus P, Peña-Ramos JA, Sánchez-Bayón A. COVID-19 and the political economy of mass hysteria. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021;18(4):1376. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18041376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes N. Is health a labour, citizenship or human right? Mexican seasonal agricultural workers in Leamington. Canada. Global Public Health. 2013;8(6):654–669. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2013.791335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnetson B. Capitalist farms, vulnerable workers. In: MacDonald S, Barnetson B, editors. Farm Workers in Western Canada: Injustices and Activism. Edmonton: University of Alberta Press; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Baum, K., & Grant, T. (2020a, June 16). Essential but expendable: How Canada failed migrant farm workers. The Globe and Mail. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/article-essential-but-expendable-how-canada-failed-migrant-farm-workers/. Accessed 30 Dec 2020.

- Baum, K., & Grant, T. (2020b, July 13). Ottawa didn’t enforce rules for employers of migrant workers during pandemic. The Globe and Mail.https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/article-how-ottawas-enforcement-regime-failed-migrant-workers-during-the/. Accessed 30 Dec 2020.

- Basok, T., Bélanger, D., & Rivas, E. (2014). Reproducing deportability: Migrant agricultural workers in South-Western Ontario. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies,40(9), 1394–1413.

- Binford, L. (2013). Tomorrow we're all going to the harvest: Temporary foreign worker programs and neoliberal political economy. Austin: University of Texas Press.

- Beaumont, H. (2020). Coronavirus sheds light on Canada’s poor treatment of migrant workers. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/jul/20/canada-migrant-farm-workers-coronavirus. Accessed 30 Dec 2020.

- Burawoy M. The functions and reproduction of migrant labour: Comparative material from Southern Africa and the United States. American Journal of Sociology. 1976;81(5):1050–1087. doi: 10.1086/226185. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RB. Public health lessons learned from biases in coronavirus mortality overestimation. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness. 2020;14(3):364–371. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2020.298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CBC News. (2020). Information revealed about video showing alleged local migrant worker living conditions. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/windsor/information-revealed-about-video-showcasing-local-migrant-worker-living-conditions-1.5618395. Accessed 30 Dec 2020.

- Castellani S, Martín-Díaz E. Re-writing the domestic role: Transnational migrants’ households between informal and formal social protection in Ecuador and in Spain. Comparative Migration Studies. 2019;7(1):1–18. doi: 10.1186/s40878-018-0108-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chartrand, T., & Vosko, L. F. (2020). Canada’s Temporary Foreign Worker and International Mobility Programs: Charting change and continuity among source countries. International Migration.

- CTV News. (2020). Power play: Agreement with Mexico. https://winnipeg.ctvnews.ca/video?clipId=1982386. Accessed 30 Dec 2020.

- Comas-Herrera, A., Zalakaín, J., Litwin, C., Hsu, A. T., Lane, N., & Fernández, J. L. (2020). Mortality associated with COVID-19 outbreaks in care homes: early international evidence. LTCcovid.org International Long-Term Care Policy Network.

- Choudry A, Smith AA, eds. (2016) Unfree labour?: Struggles of migrant and immigrant workers in Canada. Oakland, CA: PM Press.

- Detsky A, Bogoch I. COVID-19 in Canada: Experience and response. JAMA. 2020;324(8):743–744. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.14033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Díaz Mendiburo A, McLaughlin J. Vulnerabilitad estructural y salud en los trabajadores agrícolas temporales in Canadá. Alteridades. 2016;26(51):85–95. [Google Scholar]

- ESDC. (2021a). Contract for the employment in Canada of Commonwealth Caribbean seasonal agricultural workers – 2020. Last modified January 15, 2021. https://www.canada.ca/en/employment-social-development/services/foreign-workers/agricultural/seasonal-agricultural/apply/caribbean.html. Accessed 25 June 2021.

- ESDC. (2021b). Contract for the employment in Canada of seasonal agricultural workers from Mexico – 2020. Last modified January 15, 2021. https://www.canada.ca/en/employment-social-development/services/foreign-workers/agricultural/seasonal-agricultural/apply/mexico.html. Accessed 25 June 2021.

- ESDC. (2020a). Guidance for employers of temporary foreign workers regarding COVID-19. Government of Canada. Last modified April 22, 2020. https://www.canada.ca/en/employment-social-development/services/foreign-workers/employer-compliance/covid-guidance.html. Accessed 30 Dec 2020.

- ESDC. (2020b). Government of Canada invests in measures to boost protections for Temporary Foreign Workers and Address COVID-19 Outbreaks on Farms Last modified July 31, 2020. https://www.canada.ca/en/employment-social-development/news/2020/07/government-of-canada-invests-in-measures-to-boost-protections-for-temporary-foreign-workers-and-address-covid-19-outbreaks-on-farms.html. Access 30 Dec 2020.

- ESDC. 2020c. Share your thoughts: Temporary foreign worker accommodations. Last modified January 12, 2021. https://www.canada.ca/en/employment-social-development/programs/temporary-foreign-worker/consultation-accommodations.html. Accessed 30 Dec 2020.

- ESDC. 2020d. Government of Canada expands National Commodity List to give farmers greater access to labour. Last modified November 27, 2020. https://www.canada.ca/en/employment-social-development/news/2020/11/blank.html. Accessed 30 Dec 2020.

- Goldring L, Landolt P. Caught in the work–citizenship matrix: The lasting effects of precarious legal status on work for Toronto immigrants. Globalizations. 2011;8(3):325–341. doi: 10.1080/14747731.2011.576850. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hennebry, J. (2012). Permanently temporary? Agricultural migrant workers and their integration in Canada. IRPP Study, 26(1). https://irpp.org/wp-content/uploads/assets/research/diversity-immigration-and-integration/permanently-temporary/IRPP-Study-no26.pdf. Accessed 30 December 2020.

- Hennebry J, McLaughlin J, Preibisch K. Out of the loop:(In) access to health care for migrant workers in Canada. Journal of International Migration and Integration. 2016;17(2):521–538. doi: 10.1007/s12134-015-0417-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, Amy T., Natasha Lane, & Samir K. Sinha. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 on residents of Canada’s long-term care homes–ongoing challenges and policy response. International Long-Term Care Policy Network. https://ltccovid.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/LTCcovid-country-reports_Canada_Hsu-et-al_May-10-2020-2.pdf. Accessed 30 December 2020.

- Haldimand-Norfolk Health Unit [HNHU] (2020a). HNHU Board of Health - 2020–06–19 [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yHKCRjn9uGA. Accessed 30 Dec 2020.

- Haldimand-Norfolk Health Unit (2020b, November 16). News & Events: Update: Outbreak at Schuyler Farms. https://hnhu.org/update-outbreak-at-schuyler-farms-nov-16/. Accessed 30 Dec 2020.

- Horgan M, Liinamaa S. The social quarantining of migrant labour: Everyday effects of temporary foreign worker regulation in Canada. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies. 2017;43(5):713–730. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2016.1202752. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ioannidis JPA. Infection fatality rate of COVID-19 inferred from seroprevalence data. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2021;99:19–33F. doi: 10.2471/BLT.20.265892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IRCC. (2020a). Canada - Work permit holders by program, country of citizenship and year in which permit(s) became effective, 2002 - August 2020. Customized Data Request CR-20–0307. On file with authors.

- IRCC. (2020b). Canada provides update on exemptions to travel restrictions to protect Canadians and support the economy. Government of Canada. Last modified March 27, 2020. https://www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/news/2020/03/canada-provides-update-on-exemptions-to-travel-restrictions-to-protect-canadians-and-support-the-economy.html. Accessed 30 Dec 2020.

- IRCC. (2021). Canada - Work permit holders by program, country of citizenship and year in which permit(s) became effective, 2002 - March 31, 2021. Customized Data Request CR-21–0358. On file with authors.

- Joffe, A. (2021). COVID-19: Rethinking the lockdown groupthink. Frontiers in public health,9(1–25). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Justicia for Migrant Workers (J4MW). (2020). Bunkhouse conditions for migrant farm workers in Canada. [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=1&v=z-7bSBhPiXY&feature=emb_title. Accessed 30 Dec 2020.

- Katz C. Vagabond capitalism and the necessity of social reproduction. Antipode. 2001;33(4):709–728. doi: 10.1111/1467-8330.00207. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Keung, N. (2020). ‘We don’t have winter clothes or boots’: these migrant farm workers toiled through the pandemic. Now they’re stuck in Canada. Toronto Star.https://www.thestar.com/news/canada/2020/12/09/we-dont-have-winter-clothes-or-boots-these-migrant-farm-workers-toiled-through-the-pandemic-now-theyre-stuck-in-canada.html. Accessed 30 Dec 2020.

- Lau, H., Khosrawipour, V., Kocbach, P., Mikolajczyk, A., Schubert, J., Bania, J., & Khosrawipour, T. (2020). The positive impact of lockdown in Wuhan on containing the COVID-19 outbreak in China. Journal of travel medicine, 27(3), 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Luis Gabriel Flores Flores v Scotlynn Sweetpac Growers Inc, 2020 ON LRB 88341. https://www.canlii.org/en/on/onlrb/doc/2020/2020canlii88341/2020canlii88341.html?searchUrlHash=AAAAAQA6THVpcyBHYWJyaWVsIEZsb3JlcyBGbG9yZXMgdiBTY290bHlubiBTd2VldHBhYyBHcm93ZXJzIEluYwAAAAAB&resultIndex=1. Accessed 30 December 2020.

- Lupton, A. (2021). Ontario farm with migrant worker who died of COVID-19 hit with 20 charges. CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/amp/1.6191405?fbclid=IwAR1Ncjq1fxr-s-Co4P90H2f-vFJ5m9qek7-rF7GYVNK4jxeHoPVWikLMDtM