Abstract

Background

Epidemiological data from the COVID-19 pandemic report that patients with pre-existing cardiovascular disease have worse outcomes and higher mortality, and that pregnant women should be considered at high risk.

Case summary

A 25-year-old pregnant woman on the waiting list for a heart transplant, with a history of complete atrioventricular canal surgery, mitral mechanical prosthetic implant (St Jude-27), and cardiac resynchronization therapy (Boston Scientific) was hospitalized at 30 weeks of gestation for treatment of heart failure. After 7 days of hospitalization, she had a positive RT–PCR test for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 with progressive worsening of her clinical condition and acute foetal distress. Hence emergency caesarean section was performed. After the birth, the patient required mechanical ventilation, progressing to multiple organ system failures. Conventional inotropic drugs, antibiotics, and mechanical ventilation for 30 days in the intensive care unit provided significant clinical, haemodynamic, and respiratory improvement. However, on the 37th day, she suddenly experienced respiratory failure, gastrointestinal and airway bleeding, culminating in death.

Discussion

Progressive physiological changes during pregnancy cause cardiovascular complications in women with severe heart disease and higher susceptibility to viral infection and severe pneumonia. COVID-19 is known to incite an intense inflammatory and prothrombotic response with clinical expression of severe acute respiratory syndrome, heart failure, and thromboembolic events. The overlap of these COVID-19 events with those of pregnancy in this woman with underlying heart disease contributed to an unfortunate outcome and maternal death.

Keywords: COVID-19, Congenital heart disease, Pregnancy, Maternal death, Heart failure, Case report

Learning points

During pregnancy, immunological system changes increase susceptibility to the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection and can induce severe pneumonia COVID-19.

Physiological changes in cardiovascular and coagulation systems usually cause complications in pregnant women with underlying heart diseases.

The overlap of the COVID-19 inflammatory and prothrombotic response with those complications of heart disease during pregnancy can induce serious complications leading to maternal death.

The management of ventilation, septic shock, and therapy for thrombosis, remain a great challenge in the third trimester of gestation.

Introduction

Epidemiological data from severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) have documented a worse evolution of COVID-19 in pregnant women with previous heart disease.1–4 In fact, the physiological changes of pregnancy induce greater susceptibility to viral infections and severe COVID-19 pneumonia.5,6 Because of this, some are suggesting that protocols be based on the stratification of the risk of heart disease.7,8

We report the case of a young woman with complex congenital heart disease who presented with COVID-19 in the third trimester of pregnancy with a catastrophic evolution.

Timeline

| Data from 11 June to 20 July 2020 |

| Day of admission—a pregnant woman in the 30th week of gestation with pre-existing heart disease was admitted for treatment of heart failure and control of non-sustained ventricular tachycardia |

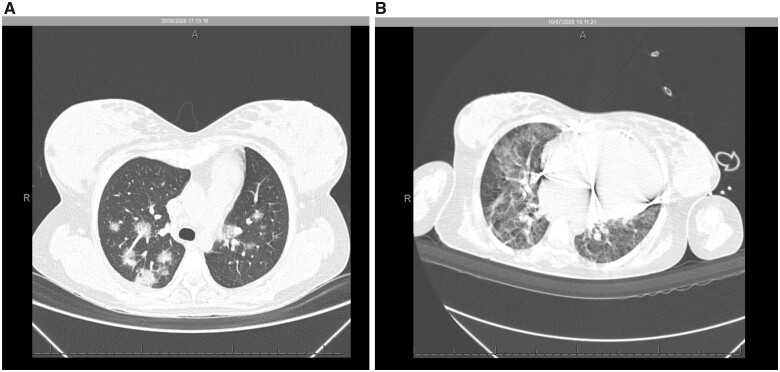

| 8th day—the patient had achieved a well-balanced clinical condition when she complained of sore throat and cough; by this time her COVID-19 test result was positive. A non-contrast chest computed tomography scan revealed bilateral ground-glass opacities in up to 25% of the lungs |

| 12th–14th day—the patient had fever, pulse oximetry oscillating between 89% and 93% SaO2 in room air, progressive reduction of arterial pressure, and foetal distress signs requiring emergency caesarean delivery at the 32nd week of gestation. The healthy premature baby was born with a negative RT–PCR test for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection |

| 15th–29th day—after the delivery, the patient developed progressive multisystem organ failure, following septic shock with a significant increase in inflammatory and prothrombotic biomarkers and severe impairment of the pulmonary parenchyma. She underwent ventilation in volume control mode with standard intensive care unit ventilators followed by antibiotic therapy, amiodarone, methylprednisolone, therapeutic unfractionated heparin, and inotropic drugs |

| 30th–36th day—the patient experienced a gradual clinical improvement in her overall condition, without fever. She was extubated and put onto non-invasive support; she remained conscious, breathing with nasal oxygen catheter and recovering physically. |

| 37th–38th day—the patient rapidly deteriorated following massive bleeding from the digestive tract and airways. She developed tachypnoea, tachycardia, and respiratory failure requiring re-intubation; however, her condition progressed to cardiopulmonary arrest followed by death |

Case presentation

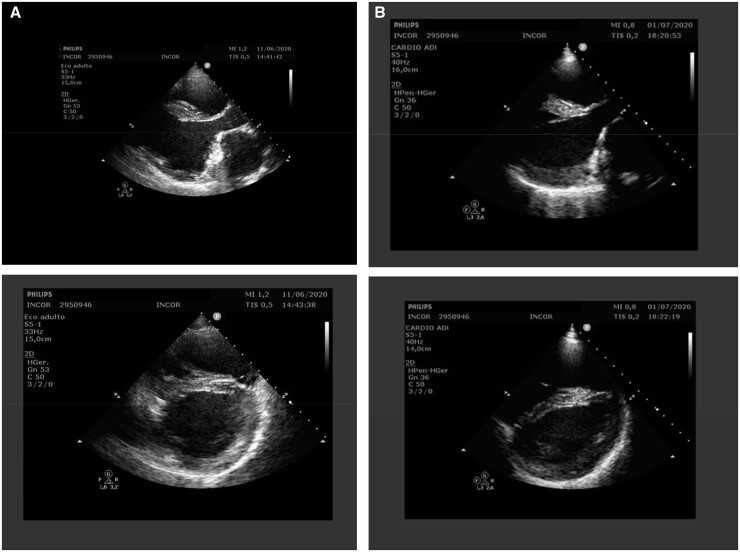

A 25-year-old pregnant woman, on the waiting list for a heart transplant was admitted for treatment of heart failure and ventricular tachycardia. She had a clinical history of complete atrioventricular canal repair at 2 years of age, which evolved with mitral regurgitation and left ventricular ejection fraction of 33% (Figure 1A and B). At 19 years of age, she underwent mechanical mitral prosthesis implantation (St Jude-27) and cardiac resynchronization therapy (Boston Scientific). Despite the cardiac interventions and optimized pharmacological treatment, she remained self-limited with New York Heart Association Class III.

Figure 1.

Transthoracic echocardiography two-dimensional images showed left ventricular diastolic diameter 58.0 mm and left ventricular ejection fraction 33.0%, right ventricle with slight dilation and moderate hypertrophy; left ventricular with marked dilation of significant systolic dysfunction with global hypokinesia (A); after 20 days of COVID-19, transthoracic echocardiography performed in an intensive care unit bed (limited window) showed no change in the measurements and left ventricular ejection fraction = 29%; (B) Simpson method.

In January 2020, she reported an unplanned pregnancy, in the 14th week of gestation. At that time, the multidisciplinary team recommended terminating the pregnancy, but she refused. She remained under strict obstetric and clinical care with reinforced comments about the risks of pregnancy and those inherent to anticoagulation. The therapy was maintained with carvedilol 25 mg/day, furosemide 40 mg/day, and warfarin with INR levels between 3.0 and 3.5.

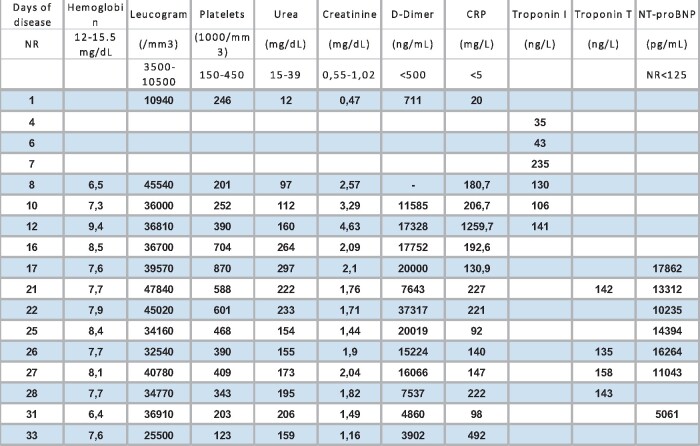

However, the patient then evolved with worsening heart failure until the 30th week of gestation and required hospitalization. The initial management, which included non-invasive positive pressure ventilation, low-dose intravenous furosemide, morphine, adjusted dose of carvedilol to 75 mg/day, improved the patient’s clinical condition. After a week of inpatient hospitalization, she developed a sore throat and cough, and her nasopharyngeal smear was positive for SARS-CoV-2. On examination, she had a temperature of 36°, blood pressure of 115/75 mmHg, heart rate of 85 b.p.m., and oxygen saturation of 97%. The physical examination revealed a decrease in respiratory sounds in the lung bases and a systolic murmur along the left sternal border. The laboratory values timeline, and echocardiographic and tomographic images are shown in Table 1 and Figures 1 and 2, respectively.

Table 1.

Laboratory results at various timepoints presentation

|

Troponin I and T by eletroquimioluminescence method.

Figure 2.

Non-contrast chest computed tomography scan demonstrated multiple ground-glass opacities associated with thickening of interlobular septal and thin interlaced reticulum, with bilateral multifocal distribution and peripheral and posterior predominance, with extent of lung involvement estimated visually of <50% (A). Nineteen days after a positive COVID-19 test, an increase was observed in multiple ground-glass pulmonary opacities, in addition to sparse foci of consolidation, with bilateral multifocal distribution, the extent of pulmonary involvement, estimated visually to be >50% (B).

After 4 days of COVID-19 symptoms, the patient developed fever, myalgia, and hypotension, and she was referred to the COVID-19 intensive care unit (ICU) with a prescription for piperacillin and tazobactam, therapeutic unfractionated heparin, amiodarone, and supportive care with norepinephrine and dobutamine. The worsening of the clinical condition induced acute foetal distress and, consequently, the need for emergency caesarean delivery in the 32nd week of pregnancy. The healthy female baby weighed 1580 g, Apgar 5-7-9, and she tested negative for SARS-CoV-2 infection. The baby was discharged 15 days after birth, and at 6-month follow-up she did not have evidence of complications related to maternal COVID-19.

After delivery, the patient required mechanical ventilation, progressing to failure of multiple organs and septic shock, which were the diagnoses made by the intensive care team. A notable increase in biochemical markers (Table 1) and worsening of the lung tomographic scan were observed (Figure 2A and B). The peripheral cultures, blood cultures, and tracheal secretion were negative. The patient was sedated (midazolam, fentanyl), paralyzed with neuromuscular blockers (cisatracurium), and received lung-protective ventilation in volume control mode (low tidal volume and low driving pressure). Initially, the arterial oxygen partial pressure and fractionated oxygen concentration in the inspired ratio (PaO2/FiO2) was 167 with an FiO2 of 45%, followed by titrated positive end-expiratory pressure of 8, and after a few days, she achieved PaO2/FiO2 of 240.

The adjusted daily prescriptions included furosemide, methylprednisolone, and antibiotic therapy with meropenem, fluconazole, polymyxin B, amikacin, and daptomycin. After being in the ICU for 30 days, the patient experienced significant clinical improvement and sustained haemodynamic and respiratory parameters. She was extubated with PaO2/FiO2 of 240, maintaining 94% oxygen saturation with a 2 L/min nasal catheter alternating with non-invasive ventilation with positive pressure. She was conscious and in good clinical condition, which allowed videoconferencing with her family. However, on the 37th day, she experienced a dramatic alteration, declining to acute respiratory failure, low cardiac output, major gastrointestinal and airway bleeding, progressing to death.

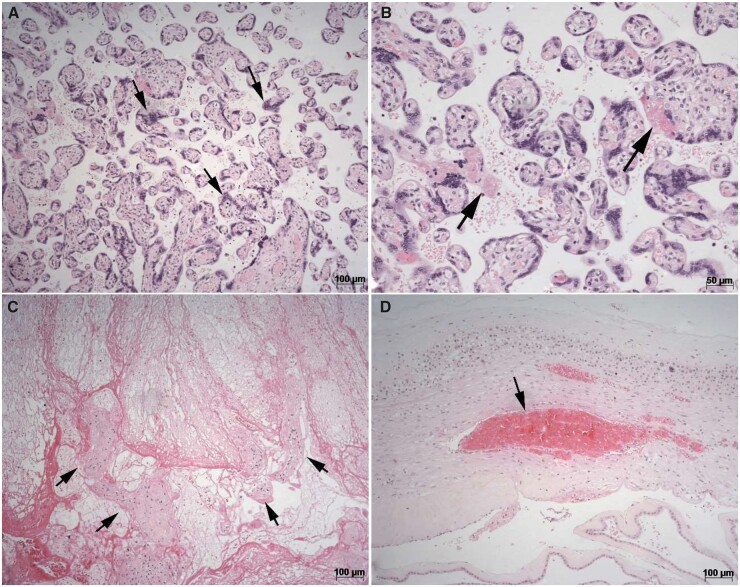

Minimally invasive necropsy guided by ultrasound (per Hospital protocol) confirmed COVID-19, showing diffuse alveolar damage, viral cytopathic effects, small pulmonary thrombi in pulmonary capillaries, acute tubular necrosis, and cerebral oedema. Placental pathological examination showed villous maturation appropriate for gestational age with frequent syncytial knots, mild fibrin depositions, and central and peripheral acute placental infarcts involving ∼20% of the villous tissue. No chronic histiocytic inter villositis or deciduous acute inflammation were noted, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Photomicrographies of placenta histological sections stained by haematoxylin and eosin method: (A) chorionic villous showing increased syncytial knots (arrows) (magnification ×100). (B) Focal and mild perivillous fibrin depositions (arrows) (magnification ×200). (C) Central acute placental infarct showing necrotic villous (arrows) (magnification ×100). (D) Acute thrombosis in chorionic membranes (arrows) (magnification ×100).

Discussion

This case illustrates the disastrous outcome of SARS-CoV-2 infection in a young woman with high-risk congenital heart disease who suffered the impact of COVID-19 during pregnancy. Usually, our approach for pregnant women with complex congenital heart disease that includes hospitalization, therapeutic optimization of heart failure, and strict control of anticoagulation, has enabled maternal survival and successful delivery.9 However, in this case, the maternal evolution was modified by the SARS-CoV-2 infection and its subsequent complications.

COVID-19’s advance from mild–moderate to severe COVID-19 over 5 days observed in this patient was in agreement with a typical timeline reported in the literature for hospitalized patients.10 Moreover, a decrease in total lung capacity and thoracic compliance imposed by the third trimester of gestation contributed to the rapid evolution to diffuse and bilateral devastation of the lung parenchyma and severe respiratory failure (Figure 2A and B).

Another grave complication was septic shock. In fact, a cohort study showed that a group of COVID-19 non-survivors had a significant prevalence of sepsis and septic shock.11 In practice, antibiotic therapy is included in the basic treatment in most patients diagnosed with COVID-19. However, there is insufficient evidence for virus-induced septic shock in patients with COVID-19. This patient, for example, had high levels of white blood cells and PCR despite several negative cultures. Currently, there is an open question about the consumption of some antibiotics in the absence of bacterial infection leading to an inflammatory storm by direct and indirect routes. In fact, studies have supported the restrictive use of antibiotics, and stopping them in patients with culture tests showing no signs of bacterial pathogens.12

In this patient, three thrombogenic factors were combined, including the prothrombotic state of COVID-19, hypercoagulability of pregnancy, and thrombogenicity of mechanical valve prostheses, each contributing to the great risk of thromboembolic events.13 Actually, elevated D-dimer predicted a poor maternal prognosis; therefore, the continuous use of therapeutic unfractionated heparin was mandatory.14

The bleeding that preceded this maternal death is also described in severely ill patients. The coagulopathy mechanisms in COVID-19 are not fully understood, but the tendency to bleed is uncommon. Major bleeding was frequent in critically ill patients using therapeutic unfractionated heparin, particularly at the gastrointestinal site, as occurred in this case.15

The pathological findings in the placenta showed poor vascular perfusion without inflammatory signals of infection by SARS-CoV-2. Vertical transmission seems to be possible but occurs in a minority of cases of maternal COVID-19 infection in the third trimester.15

Women with high-risk heart disease should always be discouraged from becoming pregnant, which should be stressed in the COVID-19 era.8

Lead author biography

Walkiria Samuel Avila has completed PhD from the Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo (FMUSP). She is a Coordinator of the Heart Disease and Pregnancy Research at Instituto do Coração do Hospital das Clinicas-FMUSP. She is a Member of the Deliberative Council of the Department of Cardiology of Women of the Brazilian Society of Cardiology. She is a Fellow of European Heart Society (FESC).

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at European Heart Journal - Case Reports online.

Slide sets: A fully edited slide set detailing this case and suitable for local presentation is available online as Supplementary data.

Consent: The authors confirm that written consent for submission and publication of this case report including images and associated text has been obtained from the patient in line with COPE guidance.

Conflict of interest: None declared.

Funding: None declared.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Estela Azeka (MD, PhD) was involved in monitoring the patient since the patient’s childhood; Ludhmila Abrahão Hajjar (MD, PhD) supervised and cared for the patient during her stay in the ICU; the obstetric team at the Hospital das Clínicas of the Faculty of Medicine of the University of São Paulo for obstetric care and delivery of the baby; Dr Protasio Lemos da Luz for reviewing the manuscript.

References

- 1. Ssentongo P, Ssentongo AE, Heilbrunn ES, Ba DM, Chinchilli VM.. Association of cardiovascular disease and 10 other pre-existing comorbidities with COVID-19 mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLos One 2020;15:e0w38215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. World Health Organization (WHO). Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Pandemic. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019 (23 April 2020).

- 3. Schwartz DA, Graham AL.. Potential maternal and infant outcomes from (Wuhan) Coronavirus 2019-nCoV infecting pregnant women: lessons from SARS, MERS, and other human coronavirus infections. Viruses 2020;12:194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Phoswa W, Khaliq OP.. Is pregnancy a risk factor of COVID-19? Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2020;252:605–609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Takemoto MLS, Menezes MO, Andreucci CB, Knobel R, Sousa LAR, Katz L.. Maternal mortality and COVID-19. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2020;16:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Brasil. Ministério da Saúde/Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde/Coordenação Geral do Programa Nacional de Imunizações/Grupo Técnico-Influenza. Brasilia; Maio; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Marques-Santos C, Avila WS, Carvalho RCM, Lucena AJG, Freire CMV, Alexandre ERG. et al. Position statement on COVID-19 and pregnancy in women with heart disease department of women cardiology of the Brazilian Society of Cardiology—2020. Arq Bras Cardiol 2020;115:975–986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Diller GP, Gatzoulis MA, Broberg CS, Aboulhosn J, Brida M, Schwerzmann M. et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 in adults with congenital heart disease: a position paper from the ESC working group of adult congenital heart disease, and the International Society for Adult Congenital Heart Disease. Eur Heart J 2021;42:1858–1865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Avila WS, Rossi EG, Ramires JA, Grinberg M, Bortolotto MR, Zugaib M. et al. Pregnancy in patients with heart disease: experience with 1,000 cases. Clin Cardiol 2003;26:135–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wang F, Qu M, Zhou X, Zhao K, Lai C, Tang Q. et al. The timeline and risk factors of clinical progression of COVID-19 in Shenzhen, China. J Transl Med 2020;18:270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hantoushzadeh S, Norooznezhad AH.. Possible cause of inflammatory storm and septic shock in patients diagnosed with (COVID-19). Arch Med Res 2020;51:347–348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sieswerda E, de Boer MGJ, Bonten MMJ, Boersma WG, Jonkers RE, Aleva RM. et al. Recommendations for antibacterial therapy in adults with COVID-19—an evidence based guideline. Clin Microbiol Infect 2021;27:61–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Iba T, Levy JH, Levi M, Thachil J.. Coagulopathy in COVID-19. J Thromb Haemost 2020;18:2103–2109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nadkarni GN, Lala A, Bagiella E, Chang HL, Moreno PR, Pujadas E. et al. Anticoagulation, bleeding, mortality, and pathology in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. J Am Coll Cardiol 2020;76:1815–1826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kotlyar AM, Grechukhina O, Chen A, Popkhadze S, Grimshaw A, Tal O. et al. Vertical transmission of coronavirus disease 2019: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2021;224:35–53.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.