Abstract

Objective:

Black patients with systemic lupus erythematous (SLE) experience greater disease incidence and severity than White patients yet are underrepresented in SLE clinical trials. We applied Critical Race Theory to qualitatively explore the influence of racism on the underrepresentation of Black patients in SLE clinical trials and to develop a framework for future intervention.

Methods:

We conducted groups in Chicago and Boston with Black adults (age ≥18 years) with SLE and their caregivers. We queried participants’ knowledge about clinical trials, factors that might motivate or hinder trial participation, and how race and experiences of racism might impact clinical trial participation. Focus group responses were transcribed verbatim and analyzed thematically.

Results:

We held four focus groups (N=31); 20 participants had SLE, 11 were caregivers. All participants were Black, 90% were female and the mean age was 54 years. Qualitative analyses revealed several themes that negatively impact trial participation including mistrust related to racism, concerns about assignment to placebo groups, strict study exclusion criteria, and SLE-related concerns. Factors that motivated trial participation included recommendations from physicians and reputable institutions, a desire to help the greater good, and culturally-sensitive marketing of trials.

Conclusion:

Actions to improve clinical trial participation among Black individuals should focus on reframing how trial information is presented and disseminated and on reevaluating barriers that may restrict trial participation. Additionally, researchers must acknowledge and respond to the presence of racial bias in healthcare. Community-Academic Partnerships may help build trust and reduce fears of mistreatment among Black individuals with SLE.

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a complex, multi-system autoimmune disease with significant racial disparities in incidence, prevalence, and severity. Black individuals are 2–4 times more likely to develop SLE than White individuals (1) and have earlier and more abrupt disease onset (2), greater risk of lupus nephritis (2,3), and higher disease-related mortality (4) than White individuals.

Despite high disease burden, Black individuals are underrepresented in SLE clinical trials comprising only 14% of trial participants, despite making up 43% of SLE cases (5). Failure to represent diverse populations in clinical research violates ethical principles of distributive justice, which require that burdens and benefits of research be equitably distributed across racial, ethnic, gender, and social groups (6). Additionally, there may be differences in the safety and efficacy of new medications based on genetic background (7). Although race is a social construct, there is evidence of genetic variability both among Black individuals and between Black and White individuals (8). Without the inclusion of Black patients in clinical trials, research findings related to treatment safety and efficacy will not be generalizable.

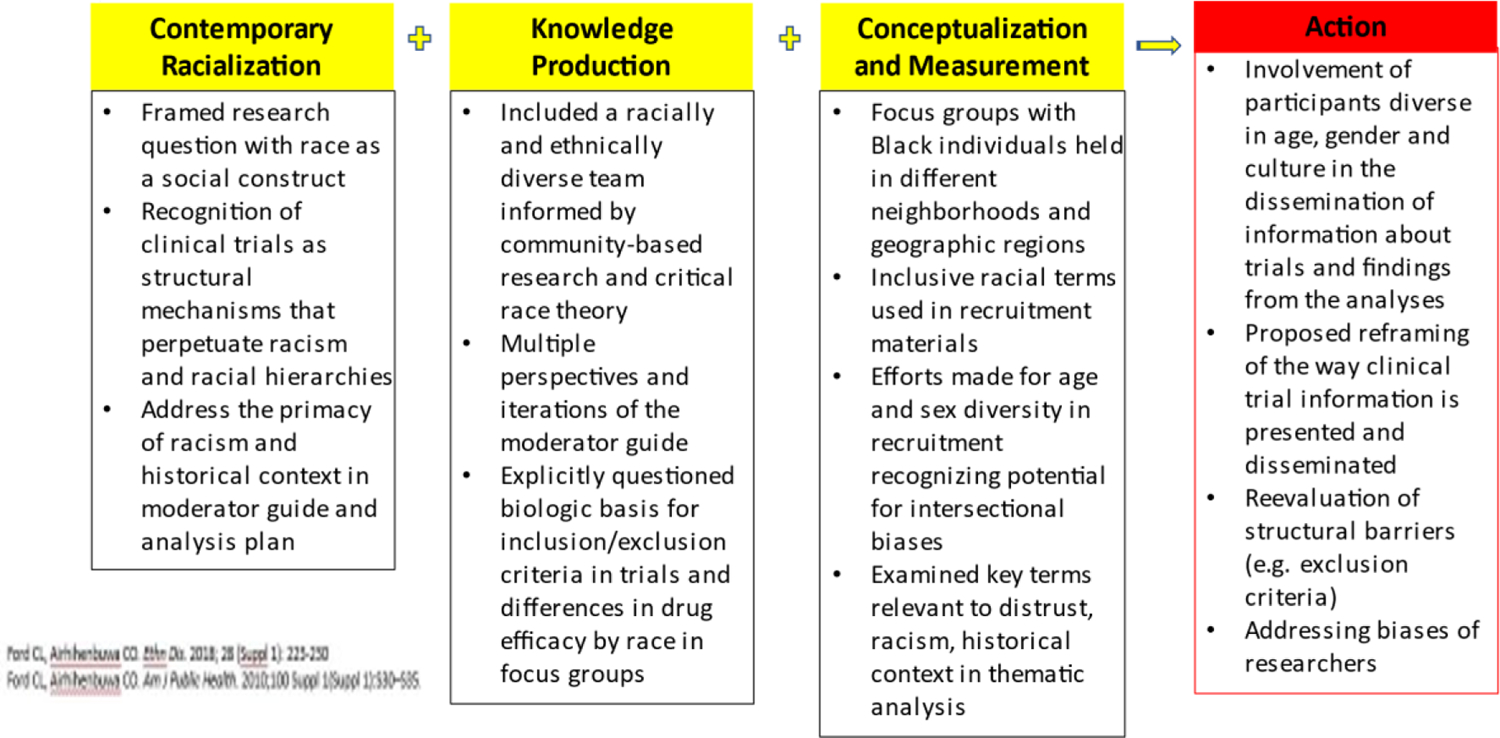

We conducted a systematic review to identify factors impacting the participation of underrepresented groups in rheumatic disease research (9). We found that no studies in the rheumatic disease population discussed the role of racism, despite historical exploitation of Black individuals in research studies and ongoing structural, institutional and interpersonal racism in the United States. To fill this gap, we used Critical Race Theory as a framework to understand clinical trial decision-making among Black SLE patients and their caregivers (10, 11). We applied the Public Health Critical Race Praxis (PHCRP) (11), which adapts Critical Race Theory to public health to understand how exposure to racism may explain in part, the underrepresentation of Black individuals in SLE clinical trials. We applied the four main components of PHCRP (Figure 1): understanding racism as it currently exists within society (“contemporary racial relations”), 2) understanding how pre-existing beliefs about racial groups may shape a project or how the project may reinforce those beliefs (“production knowledge”), 3) recognizing race as a social construct that may intersect with other sources of systemic oppression (“conceptualization and measurement”), and 4) use of the knowledge obtained from research to help stop root causes of inequity (“action”). We used this framework to identify motivating factors, barriers and mediators to trial participation.

Figure 1.

Application of the Public Health Critical Race Praxis (PHCRP) principles in the design and implementation of a qualitative analysis to understand clinical trials participation among Black individuals with lupus

PATIENTS & METHODS

Application of the Public Health Critical Race Praxis

We integrated the four components of PHCRP directly into the research process. We framed our research questions by operationalizing race as a social rather than biologic construct and acknowledged that clinical trials have often functioned as a structural mechanism where racism/racial hierarchies have operated and been perpetuated. A racially diverse, multidisciplinary study team developed the focus group moderator guide, drawing on existing literature and the PHCRP framework. To incorporate diverse perspectives among participants, we held focus groups in two racially, ethnically, and socioeconomically diverse cities.

Participants and Data Collection

We conducted focus groups in Chicago and Boston with Black individuals with SLE aged ≥ 18 years and their caregivers who participated in medical decision making. We included both caregivers and SLE caregivers in our focus groups, as several studies describe the value of including caregiver-patient dyadic units in research designed to improve patient outcomes (12, 13). Participants were identified through community-based networks and organizations in primarily Black neighborhoods, SLE support groups, local and national associations, and hospital clinics. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Northwestern Feinberg School of Medicine (Chicago) and Mass General Brigham (Boston).

Focus groups in both cities were led by experienced Black moderators, who followed the same written guide (Appendix 1). The approximately 90-minute sessions were recorded and transcribed verbatim, and detailed notes were taken. Consistent with the PHCRP, participants were asked about how race and experiences of racial discrimination might impact trial participation, ways to increase Black participation in clinical trials, and their attitudes about clinical trials designed to recruit Black patients.

Analyses

Focus group transcripts were analyzed using the constant comparative method (14), an inductive data coding process used for categorizing and comparing qualitative data. After transcription, three researchers reviewed the moderator guide and transcripts to mutually develop a coding system that reflected the overarching themes, subthemes, and proposed actions gleaned from the focus groups. Initial codes were determined after reviewing the transcripts based on the research question of interest and guided by the PHCRP. Specific attention was paid to terms relevant to experiences of discrimination, stigma, historical factors, distrust and structural racism and the ways in which these factors permeated identified themes and subthemes. We used an iterative approach to develop a standard coding framework, which was applied to all text from the focus group transcripts. Two coders independently coded the focus group transcripts using ATLAS.ti (Berlin, Germany). Coding results were then compared for consistency. When interrater agreement was not achieved, the entire team met to discuss findings and to reach final agreement. Transcripts were then recoded with revised codes. Focus groups were conducted until we determined that thematic saturation had been achieved (15). Based on our previous work among Black SLE patients in Boston and Chicago (16), our a priori hypothesis was that there would be differences in attitude, beliefs, and experiences related to clinical trials between participants in the 2 cities. Thus, we stratified our analyses by city.

RESULTS

We conducted four focus groups in Boston and Chicago in 2019. The two focus groups in Boston included 6 and 9 participants, respectively. The two focus groups in Chicago each included 8 participants. All participants identified as Black. Sixty-five percent were diagnosed with SLE (n=20); 11 were caregivers. Twelve percent of participants had a high school education, 23% had attended some college/technical school, and 65% had at least a college degree. Fifty-seven percent of participants were employed. The mean age of all participants was 54 years (range 29–75 years) and 90% of participants were female. The mean age of SLE patients was 51.7 years (range 29–71) and the mean age of SLE caregivers was 59.6 years (range 34–75). There were notable demographic differences between participants from the two cities. Seventy-three percent of Boston participants had previously participated in research, compared to only 43% of Chicago participants. Boston participants had longer disease duration than Chicago participants (mean 24.4 years versus 15.4 years), and 93% of Chicago participants were active in a church/faith community, compared to only 33% of Boston participants. Additionally, 87% of Chicago participants were college educated, compared to 40% of Boston participants (See Supplemental Tables 1 and 2).

Thematic analysis of transcripts resulted in six key themes: skepticism of clinical trials/research (subthemes of trust, racism and historical context, and placebo arms), the greater good, SLE-specific factors, physician/institutional influences, influence of social network members, and trial/research-specific factors (subthemes of exclusion criteria, information presentation/ marketing of studies).

Skepticism of Clinical Trials and Research

Trust, racism, and historical context

A key component of critical race theory is characterizing how racism currently operates within society. We wanted to understand how racism might be perpetuated within healthcare and research settings; therefore, we explored whether racism impacted the way in which our focus group participants experience research and clinical trial participation.

Some participants described general mistrust of clinical trials and medical practice due to historical racism in healthcare and research. They expressed mistrust of research stemming from their knowledge of wrongdoings that occurred during the Tuskegee Syphilis Study (17). For them, the legacy of Tuskegee persisted despite the perceived benefits of clinical research (Table 1, items a-b; hereafter referred to as Table 1a–b).

Table 1.

Participant Concerns Surrounding Trust, Racism, Historical Context, and Placebo Arms

Trust, racism, and historical context

|

Two Chicago focus group participants expressed that research skepticism would be most common for older people, who had more familiarity with the Tuskegee Syphilis Study and more negative past experiences with racism (Table 1c). These participants suggested that more educated Black individuals might be less skeptical about research, suggesting that they may have more knowledge of the healthcare system and would be more likely to take advantage of system benefits (Table 1d–e).

Several participants highlighted other historical instances of racism in medicine, including forced sterilization of Black women (18) and the story of Henrietta Lacks (19). Both were described as having long-term impact on Black healthcare utilization and as reasons to be skeptical of research. Participants were divided about whether these historical situations could occur again. Some thought that there were now significant safeguards to protect research participants from exploitation; others were still skeptical and were therefore hesitant to participate. An overall cultural mistrust of healthcare institutions, leading to less utilization of healthcare services and poorer health outcomes, was highlighted as a consequence of racism in research (Table 1f).

Participants also described their current experiences with racism. A lack of physician cultural competency by one participant, while another reported a history of racial bias in assessment and management of her chronic pain (Table 1g). One participant described an experience where people of color were inappropriately tracked in a research study that was supposed to be anonymous (Table 1h). One participant noted skepticism of trials that were only open to Black participants, expressing concern that researchers might have racist motives (Table 1i). Others, despite being skeptical, felt that new therapies needed to be tested among Black individuals to demonstrate their usefulness for the Black population.

Placebo Arms

Focus group moderators explained randomized trials, specifically random assignment to treatment or placebo (control) groups. Reactions to placebo groups were mixed. Some participants recognized that placebo arms were necessary for evaluating treatment effectiveness (Table 1j). Others preferred to get a placebo over a new treatment, as they thought that active treatments would interfere with their current medication regimen (Table 1k). Several participants said they would be disappointed to get assigned to a placebo group, as they wanted the potential benefits of active treatment (Table 1; l–n). One even stated that the risk of getting a placebo would discourage her from participating altogether. Despite possibly being assigned to a placebo, some participants said that they would still participate in order to help others (Table 1o). There was less participant resistance to clinical trials when they compared the current standard treatment to a new treatment (Table 1p).

The Greater Good

Several participants felt that clinical trial participation was of little personal benefit to them. They thought participation would advance science (Table 2a) or help others with SLE (Table 2b–f), including younger people and family members. A few participants specifically wanted to help other Black SLE patients (Table 2g). Some participants thought trial participation was crucial for eliminating SLE racial disparities (Table 2h).

Table 2.

Helping the Greater Good

|

SLE-Specific Factors

Some participants were hesitant to participate in trials because of concerns that trial drugs would interact negatively with their current medications or that new medications might be metabolized in organ systems already impacted by disease (e.g. liver, kidneys). Others feared adding another drug to their already complicated medication regimen (Table 3a). Some participants described great difficulty in receiving their initial SLE diagnosis and in identifying successful treatments. Consequently, they were not interested in receiving experimental medications that might negatively impact their currently stable disease status (Table 3b,c).

Table 3.

SLE-specific Concerns

|

A few participants feared being treated like a “guinea pig” as a result of trial participation or that living with SLE felt like being a part of a large experiment due to frequent clinical visits and specimen collections (Table 3d–e). Several participants felt that that clinical trials added an extra burden to their already burdensome clinical care experience.

Physician and Institutional Influences

Most participants were reluctant to enroll in trials without getting approval from their primary care physicians and their SLE doctors (e.g. rheumatologists or nephrologists; Table 4a). Most participants did not care about being approached for a clinical trial by a physician of the same race or gender (Table 4b); participants were most concerned about being approached by physicians who were credible, trustworthy, good listeners, and culturally competent (Table 4c–e). Two people had participated in trials before based on their rheumatologist’s recommendation. They found comfort in the fact that their physician was often the investigator leading lupus research studies (Table 4f).

Table 4.

The Influence of Physicians, Institutions, and Social Network Members

Physician/Institutional Influences

|

Beyond the physician, participants cared about institutional credibility and reputation. They also wanted institutional presence within the local community beyond conducting research studies (Table 4g,h).

Influence of Social Network Members

Most participants relied on social support from family members, friends, church members, or lupus support group members. Two participants said that their friends/family discouraged research participation due to knowledge of historical racism in research (Table 4i). One participant felt that family members were concerned that participation might cause disease-related setbacks (Table 4j).

Participants usually discussed health-related plans with family members, since they often bear the responsibility of providing illness-related support (Table 4k). While some friends and family discouraged trial participation, some participants stated that their friends and family would be the best people to get them to consider clinical trials. One participant stated that her friends and family had already told her about trials (Table 4l).

Trial/Research-Specific Factors

Exclusion criteria

Several people identified trial exclusion criteria as a barrier to trial participation among Black patients (Table 5a). They felt that researchers failed to explain why they were ineligible for studies. One participant said that the lack of adequate communication made her less interested in future trials and less likely to refer her friends and family to trials (Table 5b). One participant was concerned that she might be excluded from trials because of racial discrimination (Table 5c).

Table 5.

Trial/Research-Specific Factors

Exclusion Criteria

|

Information presentation and “marketing” of studies

Some participants did not know how to get involved in trials. Those familiar with trials emphasized the importance of having detailed trial information, including written descriptions of study drugs, information about prior trial results, and cost. Participants wanted to consult their physicians about trial medications (Table 5d) and to know in advance what role their own physicians would play in the clinical trial process. Several participants worried about whether clinical trial participation would require them to change primary care doctors (Table 5e).

When asked about ideal recruitment tools, participants mentioned YouTube videos and infomercials (Table 5f). A few participants wanted researchers to train trusted community leaders and liaisons to talk about SLE clinical trials instead of the researchers themselves (Table 5g–i). They found this to be crucial in overcoming issues of trust within the Black community. One participant suggested that people who had SLE would be the most credible recruiters for clinical trials.

Several participants stressed the importance of in-person meetings before, during, and after clinical trial enrollment (Table 5j). They wanted to meet with other SLE patients, their caregivers, and their healthcare teams in diverse locations (e.g. schools, churches, lupus support group meetings, hospitals) to talk about their clinical trial experiences.

Identifying Fears, Motivating Factors, Structural Barriers and Mediators of Clinical Trial Participation

We identified specific motivating factors, fears, structural barriers and mediators of clinical trial participation among Black SLE patients. A desire to help the greater good was an important facilitator of research participation in our sample. Many participants expressed motivation to participate in order to help others, including their family members, children with SLE, the Black community, and science in general. Participants were also motivated to participate if they could see some personal benefit, such as being assigned to an active treatment that improved their health. Participant fears included potentially being treated like a guinea pig during a trial, reliving previous historical mistreatment of Black individuals in research, and being misled during research participation. Fears regarding placebos were mixed. Some participants feared receiving a placebo rather than active treatment, while at least one person expressed a preference for placebos due to fears of exacerbating existing health issues via new treatments. Structural barriers that impacted clinical trial participation included racism, [which traversed many of the key themes identified), researcher biases, and study exclusion criteria, which often alienated Black SLE patients from clinical trial participation. With respect to mediators, participants were more likely to participate in trials if they were recommended by their physicians or if they were conducted by community-engaged healthcare institutions. Some participants required the full support of their friends and family members in order to participate in research, especially since their loved ones were involved in their ongoing care and disease management. Appropriate presentation of clinical trials to potential participants also served as a mediator. Participants wanted transparency on why Black participants were being targeted for clinical trials as well as clear, ongoing information about the trials, from the consent process, through study completion, and beyond.

DISCUSSION

Guided by critical race theory and the PHCRP, focus group participants explored contemporary racialization as it applies to clinical trial participation. Our moderator guide was designed to allow participants to address the role of race and discrimination, past and present, in research. Most participants wanted open discussion and felt that it was a critical consideration for trial participation. While there were differences in some sociodemographic factors of participants between cities, themes and quotes paralleled each other. The explicit goal of this work was to give a voice to underrepresented populations, through focus group participation. Additionally, we included a racially and ethnically diverse team of researchers at every stage of the study. In terms of the PHCRP focus on conceptualization and measurement, we considered the number of individuals included within each focus group, keeping the size small enough to allow for comfort discussing difficult topics. We also aimed for participation diversity with respect to geography to explore its interaction with race. Finally, consistent with the PHCRP framework, focus group participants discussed actionable ways to reduce barriers and improve trial representation. Through direct discussions with these groups, we can move closer to increasing clinical trial participation among Black patients.

Racism and discrimination are frequently discussed in the context of healthcare and clinical trials, as racism-related barriers to research participation have been well-documented (20, 21). The historical exploitation of Black individuals in research studies has embedded mistrust of researchers and the research process in Black communities (22, 23, 24, 25, ). Modern-day structural, institutional, and interpersonal racism toward Black individuals is an ongoing concern.

Our findings build on prior work in this area. In our systematic review (9), we observed that community engagement and ongoing discussions with social network members were crucial for promoting clinical trial participation among patients from underrepresented groups. Trust in physicians was a key theme in most studies included in the review, as several studies demonstrated that physician trust impacted willingness to participate in clinical trials.

Strengths of this study include deliberately devoted attention to the role of racism exposure in willingness to participate in clinical research using a theoretical framework specifically designed to detect and evaluate racism as a contributor to racial health disparities. While prior studies have investigated the role of race in under-enrollment (26, 27, 28), we aimed to explicitly address the role of racism as a key factor. The degree to which issues related to racism would have been raised as a prominent issue without us explicitly asking is unknown, but the degree and depth of discussions suggests that by explicitly raising it, we provided a forum that made it acceptable for racism to be discussed. We used PHCRP to frame our study design, data collection, and analyses in order to robustly describe the role of racism in trial participation.

This study was not without limitations. Many of our participants were older and had been living with lupus for years; thus, we did not capture the perspective of young, newly diagnosed individuals. Ninety percent of focus group participants were female; therefore, the perspectives of Black men were limited. Although SLE is more common in women than men, there still may be intersectionality between race and gender that we could not explore. We relied on convenience samples of Black patients who primarily attended urban SLE clinics run by study researcher-clinicians. Thus, their attitudes and experiences may be different from those of patients less connected to academic research centers. Additionally, Chicago participants were primarily middle-class Black patients whose perspectives may not represent those of Black patients from other classes. We did not clearly differentiate between SLE patients and their caregivers in our analyses. It is possible that we did have some increased affirmation of perspectives because of the caregivers’ presence. Because of the small sample size and the sensitive nature of the topics discussed, we did not present separate data for patients and caregivers, or attribute quotes directly to specific individuals. We did this to preserve complete anonymity, which was part of our commitment to our participants.

Additionally, while our study included Black participants from two diverse metropolitan areas (Boston and Chicago) we did not specifically design the study to address diverse perspectives among Black participants. Because this distinction was not incorporated into the study design, we are not able to make specific inferences about group differences. Finally, our findings may not be generalizable to Black patients living in other geographic areas, including the American South, Europe, or rural settings within the United States. Although we cannot generalize to all Black patients, we did achieve considerable diversity in our sample through the recruitment of patients from the two cities, as patients across cities were different with respect to age, disease duration, education, research experience, and church/faith community involvement. Despite these differences, discussions and themes were consistent across cities.

In considering Black participation in SLE clinical trials, researchers should recognize the role that disease burden may play in both study eligibility and desire for participation. Black patients tend to have more severe disease manifestation than White patients, which may be either a barrier or a facilitator of trial participation. Sicker patients may be more overwhelmed with their disease and its impact on their quality of life, potentially making them less likely to participate. Alternatively, if their current treatment regimen is not working or causing side effects, they may want to try something else. Likewise, differences in disease severity may contribute to concerns about receiving placebo. Finally, given that SLE trials may have strict criteria that exclude sicker patients, researchers should re-examine how study exclusion criteria impact potential Black participants..

Consistent with the PHCRP framework, we identified whow researchers can promote SLE trial participation in Black communities. Researchers must acknowledge and respond to historical and current issues related to racial bias in healthcare. Engagement with stakeholders (e.g. trusted physicians, friends, family members) is crucial for establishing trust and reducing fears of mistreatment and discrimination among Black SLE patients. Our participants desired clear and open communication about all aspects of SLE clinical trials before, during, and after trial participation. To gain trust, researchers must address their own implicit biases and invest in Black communities beyond just achieving their research goals. They should form authentic community-academic partnerships that actively engage community leaders in the research process. Such partnerships can foster clinical trial competency within community spaces and provide an important step toward increasing trial participation.

Supplementary Material

Significance and Innovation.

We applied the Public Health Critical Race Praxis, an adaptation of Critical Race Theory, to explicitly explore the role of both historical injustices and ongoing structural and interpersonal racism on under-representation of Black individuals in SLE clinical trials.

Through focus groups in two U.S. cities with Black SLE patients and caregivers, we documented the pervasive role racism and distrust play in the decision to enroll in trials.

We identified factors that can reduce barriers to enrollment, including community engagement, strong provider-patient relationships and trust building, and culturally sensitive study documents

Acknowledgments

This work was sponsored by a grant from the Department of Health and Human Services, Office for Minority Health (1 CPIMP181168-01-00)

REFERENCES

- [1].McCarty DJ, Manzi S, Medsger TA Jr, Ramsey-Goldman R, Laporte RE, Kwoh CK. Incidence of systemic lupus erythematosus race and gender differences. Arthritis & Rheumatism: Official Journal of the American College of Rheumatology. 1995; 38:1260–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Somers EC, Marder W, Cagnoli P, Lewis EE, DeGuire P, Gordon C, Helmick CG, Wang L, Wing JJ, Dhar JP, Leisen J. Population-based incidence and prevalence of systemic lupus erythematosus: the Michigan Lupus Epidemiology and Surveillance program. Arthritis & Rheumatology. 2014;66:369–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Bastian HM, Roseman JM, McGwin G Jr, Alarcon GS, Friedman AW, Fessler BJ, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus in three ethnic groups. XII. Risk factors for lupus nephritis after diagnosis. Lupus. 2002;11(3):152–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Lim SS, Helmick CG, Bao G, Hootman J, Bayakly R, Gordon C, Drenkard C. Racial disparities in mortality associated with systemic lupus erythematosus—Fulton and DeKalb Counties, Georgia, 2002–2016. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2019; 68:419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Falasinnu T, Chaichian Y, Bass MB, Simard JF. The representation of gender and race/ethnic groups in randomized clinical trials of individuals with systemic lupus erythematosus. Current Rheumatology Reports. 2018; 20:20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research, 1979. Available at https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/regulations-and-policy/belmont-report/read-the-belmont-report/index.html. Accessed August 26, 2020.

- [7].Ortega VE, Meyers DA. Pharmacogenetics: implications of race and ethnicity on defining genetic profiles for personalized medicine. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2014; 133:16–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Burchard EG, Ziv E, Coyle N, Gomez SL, Tang H, Karter AJ, Mountain JL, Pérez-Stable EJ, Sheppard D, Risch N. The importance of race and ethnic background in biomedical research and clinical practice. New England Journal of Medicine. 2003; 348:1170–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Lima K, Phillip CR, Williams J, Peterson J, Feldman CH, Ramsey-Goldman R. Factors associated with participation in rheumatic Disease-Related research among underrepresented populations: a qualitative systematic review. Arthritis Care & Research. 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Solórzano DG. Critical race theory’s intellectual roots. Handbook of Critical Race Theory in Education. 2013:48–68. [Google Scholar]

- [11].Ford CL, Airhihenbuwa CO. The public health critical race methodology: praxis for antiracism research. Social Science & Medicine. 2010; 71:1390–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Jolly M, Thakkar A, Mikolaitis RA, Block JA. Caregiving, dyadic quality of life and dyadic relationships in lupus. Lupus. 2015; 24: 918–926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Patient and caregiver perceptions of lymphoma care and research opportunities: A qualitative study. Cancer. 2019; 125: 4096–4104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Glaser BG. The constant comparative method of qualitative analysis. Social Problems. 1965; 12:436–45. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Urquhart C Grounded theory for qualitative research: A practical guide. Sage; 2012. November 16. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Phillip CR, Mancera-Cuevas K, Leatherwood C, Chmiel JS, Erickson DL, Freeman E, Granville G. Implementation and dissemination of an African American popular opinion model to improve lupus awareness: an academic–community partnership. Lupus. 2019; 28: 1441–1451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Brandt AM Racism and research: the case of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study. Hastings Center Report. 1978:21–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Rodriguez-Trias H Sterilization abuse. Women & Health. 1978; 3:10–5.10307175 [Google Scholar]

- [19].Corbie-Smith G, Thomas SB, George DM. Distrust, race, and research. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2002; 162:2458–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Scharff DP, Mathews KJ, Jackson P, Hoffsuemmer J, Martin E, Edwards D. More than Tuskegee: understanding mistrust about research participation. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2010; 21:879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Hughes TB, Varma VR, Pettigrew C, Albert MS. African Americans and clinical research: evidence concerning barriers and facilitators to participation and recruitment recommendations. The Gerontologist. 2017; 57:348–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Luebbert R, Perez A. Barriers to clinical research participation among African Americans. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2016; 27:456–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Alsan M, Wanamaker M. Tuskegee and the health of black men. The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 2018; 133:407–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Corbie-Smith G, Thomas SB, Williams MV, et al. Attitudes and beliefs of African Americans toward participation in medical research. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 1999; 14:537–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Brandon DT, Isaac LA, LaVeist TA. The legacy of Tuskegee and trust in medical care: is Tuskegee responsible for race differences in mistrust of medical care? Journal of the National Medical Association 2005; 97:951–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Anjorin A, Lipsky P. Engaging African ancestry participants in SLE clinical trials. Lupus Science & Medicine. 2018;5:e000297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Arriens C, Aberle T, Carthen F, et al. Lupus patient decisions about clinical trial participation: a qualitative evaluation of perceptions, facilitators and barriers. Lupus Science & Medicine 2020; 7:e000360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Lim SS, Kivitz AJ, McKinnell D, et al. Simulating clinical trial visits yields patient insights into study design and recruitment. Patient Preference &Adherence 2017; 11:1295–307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.