Abstract

Iodoacetic acid (IAA) is a water disinfection byproduct (DBP) formed by reactions between oxidizing disinfectants and iodide. In vitro studies have indicated that IAA is one of the most cyto- and genotoxic DBPs. In humans, DBPs have been epidemiologically associated with reproductive dysfunction. In mouse ovarian culture, IAA exposure significantly inhibits antral follicle growth and reduces estradiol production. Despite this evidence, little is known about the effects of IAA on the other components of the reproductive axis: the hypothalamus and pituitary. We tested the hypothesis that IAA disrupts expression of key neuroendocrine factors and directly induces cell damage in the mouse pituitary. We exposed adult female mice to IAA in drinking water in vivo and found 0.5 and 10 mg/l IAA concentrations lead to significantly increased mRNA levels of kisspeptin (Kiss1) in the arcuate nucleus although not affecting Kiss1 in the anteroventral periventricular nucleus. Both 10 mg/l IAA exposure in vivo and 20 μM IAA in vitro reduced follicle stimulating hormone (FSHβ)-positive cell number and Fshb mRNA expression. IAA did not alter luteinizing hormone (LHβ) expression in vivo although exposure to 20 μM IAA decreased expression of Lhb and glycoprotein hormones, alpha subunit (Cga) mRNA in vitro. IAA also had toxic effects in the pituitary, inducing DNA damage and P21/Cdkn1a expression in vitro (20 μM IAA) and DNA damage and Cdkn1a expression in vivo (500 mg/l). These data implicate IAA as a hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis toxicant and suggest the pituitary is directly affected by IAA exposure.

Keywords: pituitary, hypothalamus, DNA damage, female reproductive toxicity, water disinfection byproducts

Water disinfection byproducts (DBPs) exemplify a common driver of toxicological research: compounds initially intended for a productive end that have deleterious unintended consequences. Chemicals used to treat water to prevent potentially deadly water-borne illnesses can react with matter already present in the water, forming DBPs. In vitro studies using Chinese Hamster Ovary (CHO) and human epithelial cells have driven discoveries that a range of DBPs have significant genotoxic, cytotoxic, and teratogenic capabilities (Dad et al., 2013; Pals et al., 2013; Plewa et al., 2004, 2010). Despite evidence of potential risk and knowledge of human exposure, DBPs are largely understudied, especially in whole tissue and in vivo contexts.

One such DBP, iodoacetic acid (IAA), is of particular concern. IAA is formed as a byproduct of a reaction between an oxidizing disinfectant, like chlorine, and iodide. As chlorine is widely utilized and iodide occurs naturally in water, there is a high risk of IAA formation in public water supplies (Dong et al., 2019; Richardson, 2005). In the previous in vitro studies, IAA was found to be one of the most cyto- and genotoxic DBPs tested. In cultured fibroblast cell lines, IAA introduced significant DNA damage and when the IAA-treated cells were inoculated into mice in vivo, the mice developed tumors, indicating it has significant tumorigenic potential (Wei et al., 2013). IAA exposure can also induce DNA damage in cultured oocytes (Jiao et al., 2021). In vitro work focused on ovarian follicle cultures shows that IAA can disrupt folliculogenesis and estradiol synthesis (Gonsioroski et al., 2020; Jeong et al., 2016). While existing in vivo studies are very limited, prior research demonstrates early adult exposure to IAA in rodents can lead to decreased ovarian weight and disrupted hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid (HPT) axis function (Xia et al., 2018). Together, there is a strong rationale to think that IAA could have deleterious effects on tissue health and in particular on endocrine tissues. However, this question requires further exploration.

The neuroendocrine system is a vital mediator of interconnected axes in which consequences at any level could mean result in hormonal alterations at another. Yet at present, the hypothalamus and pituitary are unstudied in the context of IAA exposure. Further, they could be prime targets of IAA action. Prior studies from our lab have illustrated that the pituitary is directly sensitive to environmental toxicants that can interfere with cell viability and induce cell cycle arrest through P21/Cdkn1a induction (Weis and Raetzman, 2016, 2019). This may be especially relevant considering IAA’s previously established cyto- and genotoxic mechanisms. Additionally, the hypothalamus and pituitary have been shown to be vulnerable to disruption by endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs), especially during development. Further, this EDC action can be specifically consequential for HPG axis function (Gore et al., 2015). IAA has been shown to act as an EDC with potential estrogenic and androgenic activity (Kim et al., 2020; Long et al., 2021). Not only would it be feasible for IAA to affect the hypothalamus and pituitary, but also such effects could be deleterious for physiology.

We took a 2-pronged approach to address the impact of IAA in the hypothalamus and pituitary: pursuing effects on hormone-related gene and protein expression in both regions and toxic effects in the pituitary. Based on the strength of previously discussed data on the ovaries and ovarian cells, we focused our hormone-regulation experiments on contributions to the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis. In the hypothalamus, kisspeptin-expressing neurons in the arcuate nucleus (ARC) and anteroventral periventricular nucleus (AVPV) act to stimulate the release of gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) from neurons in the medial preoptic area (mPOA). ARC kisspeptin neurons maintain a pulsatile release of GnRH and are negatively regulated by ovarian estradiol feedback during the majority of the estrous cycle. Conversely, AVPV kisspeptin neurons are stimulated by estrogen and induce the GnRH surge that ultimately leads to ovulation. GnRH acts on pituitary gonadotropes, which also receive feedback from the ovaries, to induce the release of luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle stimulating hormone (FSH). It is LH and FSH that are ultimately released into circulation to guide ovarian physiology. As this chain of effectors illustrates, there are numerous points at which IAA exposure could interfere with hypothalamic and pituitary contributions to the HPG axis.

Interrogating these effects will be an important step in understanding and addressing the consequences of IAA exposure. Thus, we tested the hypothesis that IAA acts as an HPG-disrupting toxicant by interfering with the expression of key factors in the hypothalamus and pituitary and leading to cytotoxic and/or genotoxic damage in the pituitary.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

Animal care

For in vivo dosing experiments, cycling female CD-1 (postnatal day 26) were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Charles River, California) and housed at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, College of Veterinary Medicine Animal Facility. For explant culture experiments, CD-1 mice were bred from lines originally obtained from Charles River Laboratories (Charles River) and housed at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Burrill Hall Animal Facility. Both sets of animals were kept under 12 h light-dark cycles and provided ad libitum access to water and Teklad 8664 rodent diet (Envigo). All procedures were approved by the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

In Vivo dosing

Female CD-1 mice were aged to 40 days. At P40, mice were divided into groups and given varying doses of IAA (Sigma-Aldrich) dissolved in drinking water. This exposure mechanism was chosen to best replicate the human context in which the primary source of exposure is drinking water. For initial in vivo dosing, group were as follows: No IAA added (Control), 0.5, 10, 100, or 500 mg/l IAA, corresponding to approximate ingestion levels of 3.48, 69, 490, and 1700 μg of IAA per mouse per day (Gonsioroski et al., 2021). Although human exposure levels have not been well established, prior studies have indicated IAA levels in tap water can be as a high as 2.18 μg/l (Wei et al., 2013), with total haloacetic acid, the class to which IAA belongs, levels as high as 136 μg/l (Srivastav et al., 2020). Overall human exposure to IAA is likely much higher, as food and dermal contact from swimming pools and bath water further introduce DBPs into an individual’s environment (Allen et al., 2021; Chowdhury et al., 2014). Mice were given ad libitum access to this drinking water for 35–40 days. The dosing experiments were repeated with 2 groups: no IAA added (Control) and 500 mg/l IAA and again with 2 groups: no IAA added (Control) and 10 mg/l IAA.

Tissue collection

For in vivo experiments, whole brains and pituitary glands were harvested from 75- to 80-day-old IAA-dosed and control female mice in diestrus. Brains were flash frozen on dry ice shortly the following decapitation and stored at −80°C. Regions of interest were dissected from frozen brains. Sectioning caudal to rostral, regions were identified using The Mouse Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates: Fourth Edition (Paxinos and Franklin, 2019). Starting approximately 150 μm caudal of the ARC, 2 overlapping punches were collected, incorporating the ARC, using a 1.25 mm diameter biopsy punch. Punches were approximately 2 mm in depth spanning approximately Bregma −2.91 mm to approximately Bregma −.91 mm. Brains were then sectioned rostrally until morphological markers indicated a region approximately 100 μm caudal to the beginning of the AVPV. A single 1.25 mm diameter, approximately 1 mm-deep, biopsy punch incorporating the AVPV and the medial preoptic nucleus (mPOA) was collected. This punch spanned approximately Bregma −0.11 mm to approximately Bregma 0.89 mm. Sections were collected immediately preceding and following punches to confirm location. For quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) analysis, pituitary glands were collected into RNA Later (Thermo Fisher) and stored at −20°C. For in vivo IHC experiments, pituitary tissue was fixed for 60 min. in 3.7% formaldehyde/phosphate buffered saline (PBS), then cryoprotected in 30% sucrose/PBS before embedding in Optimal Cutting Temperature (Tissue-Tek) and storage at −80°C until sectioning.

Pituitary explant cultures

Whole pituitaries were harvested from female postnatal day 40 or 41 CD-1 mice for in vitro explant culture as described in Weis and Raetzman (2016). For each exposure group, 1 to 4 pituitaries were placed on Millicell CM 6-well plate culture inserts (Millipore) and cultured in DMEM/F12 medium containing 10% charcoal stripped Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS, Sigma), and 10,000 IU Penicillin/10,000 μg/ml Streptomycin (Fisher Scientific). Explants were exposed to varying levels of IAA in culture media based on randomly assigned treatment groups beginning from initial plating and ending at harvest 48 h later. For initial qPCR experiments, IAA treatments were: 0.2 μM IAA, 2 μM IAA, 20 μM IAA, all diluted in DMSO as a vehicle. Control cultures received only 0.1% DMSO. These dosages were chosen to generally correspond with ovary cultures performed in Jeong et al. (2016) and Gonsioroski et al., 2020. Specific values were chosen in order to create a concentration gradient. After establishing a concentration curve in initial experiments, 20 μM IAA was selected for subsequent cultures. For all IHC experiments, comparison groups were 0.1% DMSO (control) and 20 μM IAA. For qPCR analysis, following harvest, explants were submerged in TRIzol and stored at −80°C. These cultures were repeated 4 times such that presented data represent individuals from 4 independent cultures. For IHC analysis, explants were washed in PBS, then fixed in 3.7% formaldehyde/phosphate buffered saline (PBS) for 30 min. before cryoprotecting in 30% sucrose/PBS. They were then embedded in Optimal Cutting Temperature (Tissue-Tek) and stored at −80° C until sectioning. These cultures were repeated 4 times such that presented data represent individuals from 3 to 4 independent cultures.

Immunohistochemistry

All pituitary tissue was sectioned to 12 μm using a cryostat (Leica). For each individual, 3 slides evenly spaced through the tissue with 2 sections on each slide were selected. Immunostaining was performed using antibodies for FSHβ (diluted 1:100, National Hormone and Peptide Program, AF Parlow), LHβ (diluted 1:100, National Hormone and Peptide Program, AF Parlow), P21 (diluted 1:500; BD Pharmingen), and γH2AX (1:500; Cell Signaling). Slides were air dried for 5 min. and fixed in 3.7% formaldehyde/PBS for an additional 10 min. For P21 and γH2AX immunostaining, antigen retrieval was performed by immersing slides in 0.01M sodium citrate pH 6.0 at approximately 95°C for 5 min (in vitro samples) or for 10 min. followed by a 15 min. cooling period (in vivo samples). For P21 staining using 3-3′-diaminobenzidine staining (DAB), slides were submerged in 1.5% hydrogen peroxide in PBS for 20 min (in vitro slides) or 30 min (in vivo slides). For in vivo P21 staining experiments, slides underwent a 1-h block period specific to mouse-on-mouse antibodies in which they were incubated in 2% donkey anti-mouse IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch). Before primary antibody treatment, all slides were blocked for 1 h using 5% normal donkey serum (Jackson ImmunoResearch) diluted in a block containing 3% bovine serum albumen (Jackson ImmunoResearch), and 0.5% Triton-X100 in PBS. Primary antibodies were applied to slides overnight at 4°C. For all stains, a negative control slide was included that substituted incubation in block for primary antibody. Sections were then incubated in biotin conjugated anti-rabbit secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch) for 1 h at room temperature, followed by incubation with streptavidin cy3, for 1h at room temperature. Slides were mounted using antifade mounting medium (0.1M Tris pH 8.5, 20% glycerol, 8% polyvinyl alcohol, 2.5% 1,4-diazabicyclo[2.2.2]octane) containing the nuclear stain 4′,6-Diamidino-2-Phenylindole, dihydrochloride (DAPI), and visualized with a fluorescent microscope (Leica). Sections were then incubated in biotin-conjugated anti-mouse (P21) or anti-rabbit (all others) secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch) for 1 h at room temperature. For P21, following secondary incubation, slides underwent streptavidin-HRP amplification using the Vectastain Elite ABC kit (Vector) and visualization by DAB staining. These slides were then dehydrated and coverslips were affixed using Permount. These slides were visualized using a brightfield microscope (Leica).

Quantification of immunohistochemistry results

FSHβ, LHβ, and in vivo P21 experiments were quantified as follows. For each individual, 6–8 images were be taken of each section on a given slide. In a subset of images, DAPI-positive cells were quantified to determine heterogeneity of total number of cells per image. After determining number of cells per image where largely homogeneous and total number did not significantly differ between individuals, only immunopositive cells were counted and included in analysis. Number of immunopositive cells across images of same slide were averaged together. The 3 slides were summed together to get a representative quantification for each individual. For γH2AX experiments, quantification was performed by counting the total number of immunopositive cells in a given section, averaging the sections of the same slide together, and taking a sum of counts per individual.

RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis

For hypothalamic punches and pituitary glands, RNA extraction was performed using TRIzol reagent according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Life Technologies). Hypothalamic punches were broken up by pipetting up and down in TRIzol. Pituitary glands were homogenized in TRIzol to disrupt the tissue. RNA yield and purity were determined by spectrophotometry. Using the ProtoScript M-MuLV First Strand cDNA synthesis kit (New England BioLabs, Ipswich, Massachusetts), approximately 0.5 μg of RNA was synthesized into cDNA. When limited by the amount of RNA yield, 6 μl of RNA suspended in H2O, the maximum allowed by the kit, was used. A no-enzyme sample was included as a negative control for each set of synthesis reactions.

qPCR

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) was performed on the cDNA samples using gene-specific primers. Results were analyzed using the double change in threshold cycle (ΔΔCT) method as previously described (Goldberg et al., 2011). Gnrh1 and Kiss1 in AVPV/POA mRNA samples were normalized to control gene Ppia. ARC and all pituitary mRNA samples were normalized to Gapdh. Student’s 2-tailed t-tests were performed to ensure there were no significant changes in Ppia nor Gapdh between dosage groups, thus verifying it could suitably be used as a control gene. Primer sequences for each gene are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

qPCR Primer Sequences.

| Gene Name | Forward 5ʹ to 3ʹ | Reverse 5ʹ to 3ʹ |

|---|---|---|

| Bax | TGAAGACAGGGGCCTTTTTG | AATTCGCCGGAGACACTGG |

| Bcl2 | ATGCCTTTGTGGAACTATATGGC | GGTATGCACCCAGAGTGATGC |

| Cdkn1a | TTGGAGTCAGGCGCAGATCCACA | CGCCATGAGCGCATCGCAATC |

| Cga | GTATGGGCTGTTGCTTCTCC | GTGGCCTTAGTAAATGCTTTGG |

| Esr1 | AATTCTGACAATCGACGCCAG | GTGCTTCAACATTCTCCCTCCTC |

| Fshb | TGGTGTGCGGGCTACTGCTAC | ACAGCCAGGCAATCTTACGGTCTC |

| Gapdh | GGTGAGGCCGGTGCTGAGTATG | GACCCTTTTGGCTCCACCCTTC |

| Gapdh | GGTGAGGCCGGTGCTGAGTATG | GACCCTTTTGGCTCCACCCTTC |

| Gnrh1 | AGCCAGCACTGGTCCTATGG | CAGTACATTCGAAGTGCTGGGG |

| Gnrhr | ATGATGGTGGTGATTAGCC | ATTGCGAGAAGACTGTGG |

| Kiss1 | TGCTGCTTCTCCTGT | ACCGCGATTCCTTTTCC |

| Lhb | CCCAGTCTGCATCACCTTCAC | GAGGCACAGGAGGCAAAGC |

| mKi67 | AGTAAGTGTGCCTGCCCGAC | ACTCATCTGCTGCTGCTTCTCC |

| p53 | CCAGCCACTCCATGGCCC | TGCACAGGGCACGTCTTCGC |

| Pdyn | GAGGTTGCTTTGGAAGAAGGC | TTTCCTCTGGGACGCTGGTAA |

| Ppia | CAAATGCTGGACCAAACACAAACG | GTTCATGCCTTCTTTCACCTTCC |

| Tac2 | TTCCACAGAAACGTGACATGC | GGGGGTGTTCTCTTCAACCAC |

Statistical analyses

All statistics were performed using Graph Pad Prism 8.2.1. Variance was assessed using an F-test of equality of variance for 2-group analyses and Bartlett’s test for those with 3 or more groups. With 3 or more groups, significance was determined using a one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s post-hoc analysis when variance was equal and using a Welsh’s ANOVA followed by a Dunnett’s T3 post-hoc analysis when variance was unequal. Post-hoc analyses compared experimental groups to controls. For analyses with a significant difference in variance between 2 groups, statistics were performed on log-transformed data. When only one experimental condition was used, a Student’s t-test was used to compare the experimental group with controls.

RESULTS

Iodoacetic Acid Increases mRNA Expression of the Hypothalamic Hormone Kisspeptin in the Arcuate Nucleus In Vivo While Leaving Other Key Hormones Unchanged

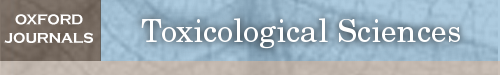

In the hypothalamus, 2 regions, the ARC and the AVPV, express kisspeptin which acts on GnRH neurons to control pulsatile release of GnRH or the GnRH surge, respectively. We assessed kisspeptin (Kiss1) mRNA in both these regions in vivo and found that IAA did not alter expression at any dosage in the AVPV (Figure 1A), but at 0.5 and 10 mg/l IAA significantly increased expression in the ARC (Figure 1B). Finding this change in mRNA in the ARC, we wanted to determine if mRNA of the known autoregulatory peptides released by ARC kisspeptin neurons, neurokinin B (Tac2) and dynorphin (Pdyn), were changed, potentially contributing to the resulting shift in Kiss1 (Navarro et al., 2009). We found no changes in Tac2 mRNA nor Pdyn mRNA (Figs. 1C and 1D). The hypothalamus responds in a homeostatic manner to feedback from estrogen released from the ovaries, which inhibits kisspeptin neurons in the ARC and stimulates them in the AVPV. To assess one indicator of potential contributions of altered sensitivity to estrogen feedback, we assessed mRNA of estrogen receptor-α (Esr1) in the ARC, finding no change between any dosage and controls (Figure 1E). As kisspeptin neurons act on GnRH neurons to stimulate the release of GnRH which ultimately acts on pituitary gonadotropes to release LH and FSH, we also looked at GnRH (Gnrh1) mRNA, which indicated no difference between any condition and controls (Figure 1F).

Figure 1.

Iodoacetic acid (IAA) increases mRNA expression of key hypothalamic hormone kisspeptin in the arcuate nucleus (ARC) although leaving other key hormones unchanged. Female CD-1 mice were exposed to varying levels of IAA in their drinking water for 45 days. mRNA expression of kisspeptin (Kiss1) was assessed in the ARC and found to be significantly increased at 0.5 and 10 mg/l dosages compared with controls (A, N = 9–10). Kiss1 was also assessed in the anteroventral periventricular zone (AVPV) and found unchanged (B, N = 6–8). mRNA expression of the neuropeptides neurokinin B (Tac2) and dynorphin (Pdyn) were similarly unchanged between controls and any IAA condition (C, N = 9; D, N = 6–8). Estrogen receptor-α (Esr1) expression in the ARC was unchanged (E, N = 3–6). Expression of gonadotropin releasing hormone (Gnrh1) was also unchanged (F; N = 10–11). One-way ANOVA for ARC Kiss1, p = .02, *, p ≤ .05 by Dunnett’s post-hoc analysis.

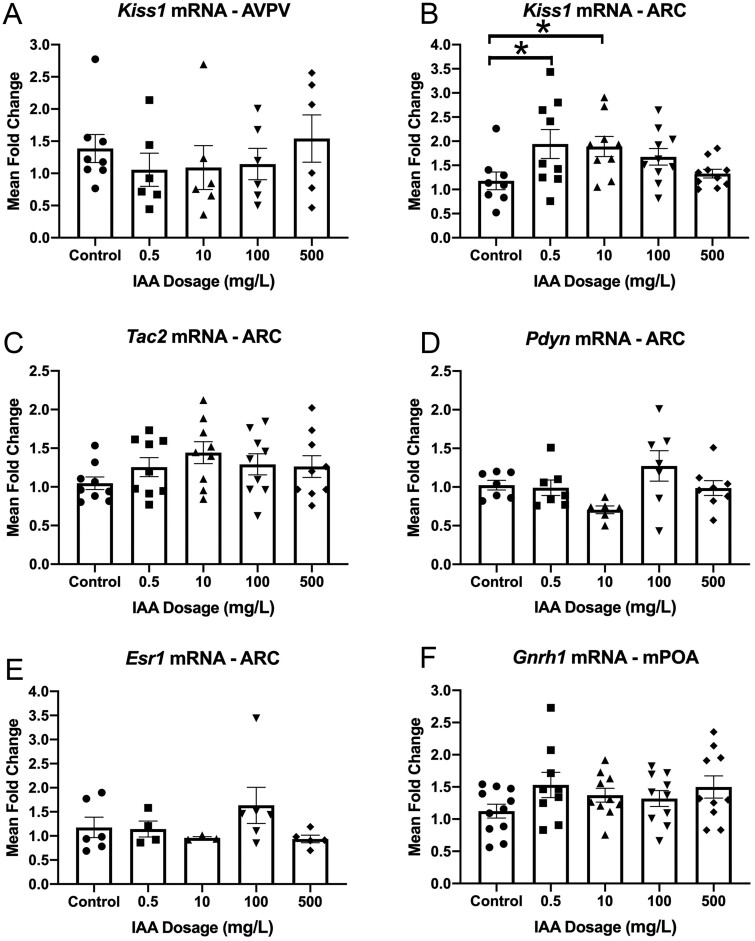

In Vivo, Iodoacetic Acid Significantly Reduced Fshb mRNA and FSHβ Protein Expression, While Preserving Expression of Other Key Reproductive Hormone-Related Genes and Proteins

We wanted to examine IAA’s effects on the pituitary, as it is the other major component of neuroendocrine regulation of reproduction. FSH and LH are made up of a shared alpha-subunit, glycoprotein hormones, alpha subunit (CGA), and differing beta-subunits which determine the final hormone produced. Levels of FSH beta-subunit mRNA (Fshb), were significantly reduced between the control and 10 mg/l IAA conditions (Figure 2A). LH beta-subunit mRNA (Lhb), the expression did not significantly differ between any IAA level and controls (Figure 2B). CGA (Cga) expression was not altered by IAA in vivo (Figure 2C). Observing a significant reduction in mRNA with 10 mg/l IAA exposure, we wanted to observe protein expression of FSHβ at that dosage using IHC (Figs. 2D and 2E). We found a significant reduction in number of FSHβ-positive cells in individuals exposed to IAA compared with controls (Figure 2F). We also assessed protein expression of LHβ, comparing control and 10 mg/l IAA conditions (Figs. 2G and 2H). The numbers of immunopositive cells were not significantly different when quantified (Figure 2I).

Figure 2.

In vivo, IAA significantly reduced FSHβ protein and Fshb mRNA expression although preserving expression of other key reproductive hormone-related genes and proteins. qPCR analysis was performed on pituitary tissue harvested from mice exposed to a range of IAA levels in their drinking water. Fshb mRNA levels were significantly decreased in the 10 mg/l IAA condition compared with controls (A, N = 9–10). mRNA analysis revealed no impact of IAA exposure on Lhb (B, N = 10) or Cga (C, N = 5). Immunohistochemistry (IHC) for FSHβ was carried out on pituitary tissue harvested from mice exposed to either 0 mg/ml or 10 mg/l IAA in their drinking water (D and E, N = 5). The number of positively stained cells were quantified revealing a significant reduction in the IAA exposed group (F, N = 5). IHC for LHβ was performed to compare control and 10 mg/l IAA groups (G and H, N = 4). Quantifying positively stain cells indicated no significant difference between groups (I, N = 4). Negative control for both IHC stains (inset in panel D). One-way ANOVA for Fshb mRNA, p = .04,*, p ≤ .05 by Dunnett’s post-hoc analysis. T-test analysis for FSHβ counts,*, p ≤ .05. Scale bars = 75 μM.

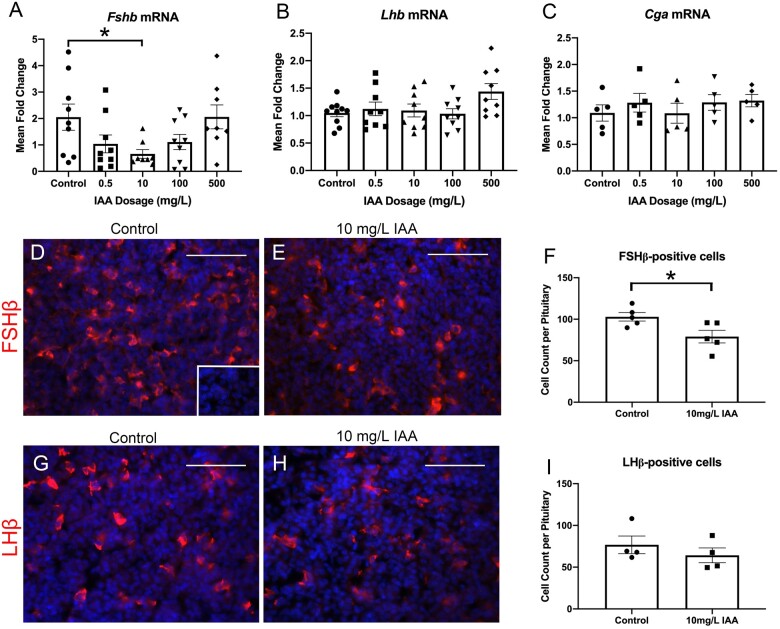

In Vitro, Iodoacetic Acid Significantly Reduces Fshb, Lhb, and Cga, but Not Gnrhr mRNA, as Well as FSHβ, but Not LHβ Protein Expression

To observe the effects of IAA directly on the pituitary in the absence of signals from the hypothalamus and the rest of the reproductive axis, we carried out whole pituitary cultures, exposing explants to varying levels of IAA. Assessing mRNA expression of Fshb on a range of IAA concentrations revealed a significant difference between controls and those exposed to 20 μM IAA (Figure 3A). We also assessed Lhb, comparing control and 20 μM IAA conditions, finding a significant reduction in expression with IAA exposure compared with control (Figure 3B). We found a similar reduction in Cga mRNA levels, but no difference in Gnrhr mRNA expression with IAA exposure compared with control (Figure 3C). Immunohistochemistry for FSHβ suggested an apparent decrease in the number of positively-stained cells between explants exposed to DMSO alone and those exposed to 20 μM IAA (Figs. 3D and 3E). This visual difference was confirmed as a significant reduction by quantifying immunopositive cells (Figure 3F). We also performed immunohistochemistry for LHβ (Figs. 3G and 3H). There was no significant difference between groups when quantifying number of positive cells (Figure 3I).

Figure 3.

In vitro, IAA significantly reduces Fshb, Lhb, and Cga, but not Gnrhr mRNA, as well as FSHβ, but not LHβ protein expression. qPCR analysis for Fshb was performed on explant cultures exposed to a range of IAA concentrations. Fshb mRNA levels were significantly decreased in the 20 μM IAA condition compared with controls (A; N = 9–10). mRNA expression was assessed for Lhb, Cga, and Gnrhr in an explant culture comparing DMSO-only treated explants with those treated with 20 μM IAA. Lhb was significantly reduced in the IAA-treated condition (B; N = 9). Cga was reduced with IAA treatment compared with controls as well, whereas Gnrhr was unchanged between conditions (C; N = 9). An IHC for FSHβ on mice and exposed to either DMSO vehicle alone or 20 μM IAA in culture for 48 h revealed an apparent reduction in FSH-positive cells in the IAA-exposed condition compared with controls (D and E, N = 3). This was verified by quantification (F, N = 3). IHC for LHβ suggested no apparent change between DMSO and 20 μM groups (G and H, N = 4). Quantification showed there was no significant difference in number of protein-positive cells (I, N = 4). Negative control for both IHC stains (inset in panel D). Welsh’s ANOVA for Fshb p = .0003, **, p ≤ .01 by Dunnett’s T3 post-hoc analysis. T-test analyses for Lhb, Cga, and FSHβ, *p ≤ .05; **p ≤ .01. Scale bars = 75 μM.

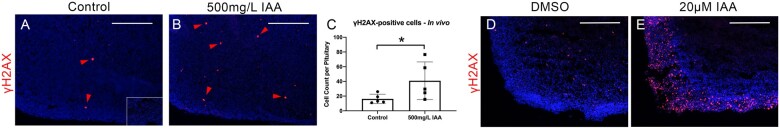

Iodoacetic Acid Exposure Induced DNA Damage Both In Vivo and In Vitro

One potential mechanism for IAA to contribute deleteriously to the health of the tissue is through DNA damage (Jiao et al., 2021). We carried out immunohistochemistry for the marker of DNA damage γH2AX in mice exposed to 500 mg/l compared with controls (Figs. 4A and 4B). Quantifying the number of immunopositive cells in the entire pituitary showed a significant increase in γH2AX in the group exposed to 500 mg/l IAA (Figure 4C). Assessing γH2AX-positivity in our pituitary explant cultures revealed a marked increase in DNA damage in those exposed to 20 μM IAA compared with control (Figs. 4D and 4E).

Figure 4.

IAA increased DNA damage in vivo and in IAA-exposed explants. IHC for the DNA damage marker γH2AX was performed on pituitary tissue collected from adult female mice exposed to 0mg/l IAA or to 500 mg/l IAA in vivo (A and B, N = 5). Quantifying the number of γH2AX-positive cells in the whole pituitary showed a significant increase in the IAA exposed group (C, N = 5). Pituitaries exposed to either DMSO alone or 20 μM IAA in whole explant cultures were also immunostained for γH2AX which revealed a visually marked increase in the number of positive cells (D and E; N = 3). Negative control is shown as an inset in panel A. T-test analysis, *p ≤ .05. Scale bars = 250 μM.

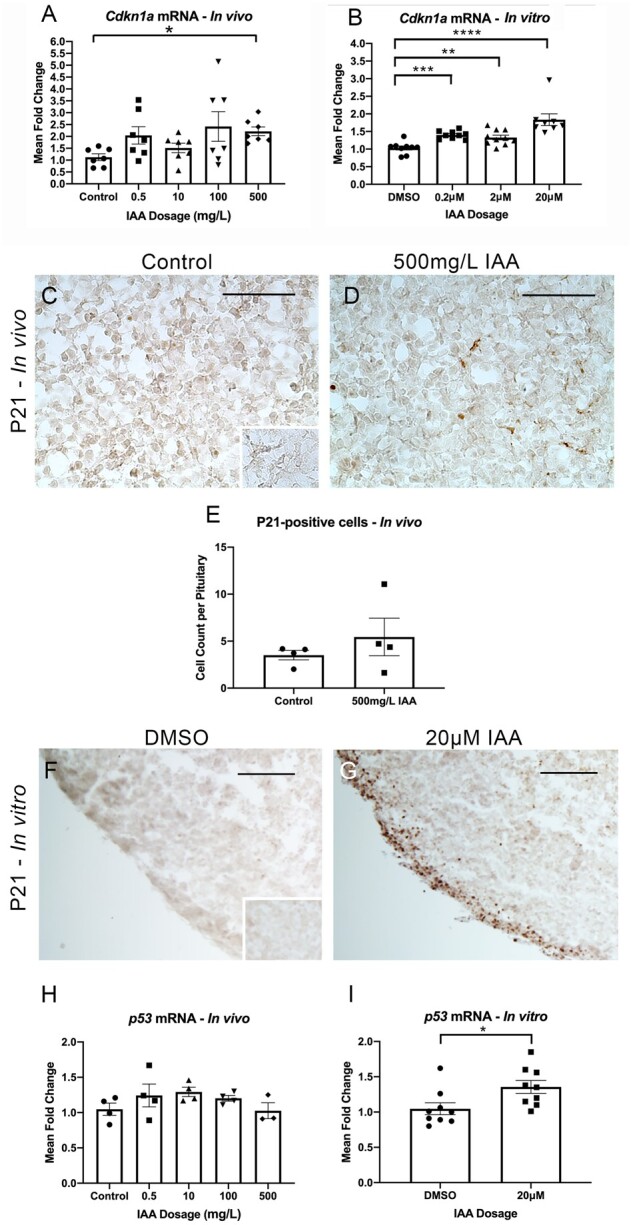

Iodoacetic Acid Increased P21 Protein Expression In Vitro and P21 (Cdkn1a) mRNA Both In Vivo and In Vitro. IAA Also Increased Expression of p53 In Vitro, but Not In Vivo

Prior data from our lab have illustrated that P21 induction may be a particularly relevant component of the pituitary response to toxicants (Weis and Raetzman, 2016, 2019) as well as being induced following DNA damage (Abbas and Dutta, 2009). We assessed P21 mRNA (Cdkn1a) in our in vivo samples, finding a significant increase in expression levels with exposure to 500 mg/l IAA compared with control (Figure 5A). qPCR for Cdkn1a expression in vitro showed increased expression in all exposure groups compared with controls (Figure 5B). Finding an increase in mRNA at 500 mg/l IAA in vivo, we assessed protein expression comparing this group to controls (Figs. 5C and 5D). Quantifying the number of cells immunopositive for P21 showed no significant difference between groups (Figure 5E). In vitro, this assay revealed a strikingly apparent increase in P21-positive cells in the IAA-treated condition compared with controls (Figs. 5F and 5G). DNA damage is associated with p53-mediated induction of P21. Having observed increases in both DNA damage and P21/Cdkn1a, we evaluated mRNA expression of p53. In vivo, we found no significant changes between experimental and control conditions (Figure 5H). In vitro, mRNA expression of p53 was significantly increased with IAA exposure (Figure 5I).

Figure 5.

IAA increased P21 (Cdkn1a) mRNA in vivo and in vitro, and P21 positive cells in vitro. IAA also increased expression of p53 in vitro. mRNA for P21 (Cdkn1a) was significantly higher in mice exposed to 500mg/l IAA in vivo compared with controls (A, N = 7). There was a significant increase in Cdkn1a expression compared with controls at all doses of IAA in vitro (B, N = 8–10). IHC for P21 was performed on control and 500 mg/l IAA-exposed pituitary samples harvested in vivo (C and D, N = 4). The number of positive cells was quantified, finding no difference between groups (E, N = 4). P21 was also assessed in in vitro samples, which indicated a visually marked increase in the number of positive cells in the IAA condition (F and G, N = 3). mRNA expression of p53 was assessed in vivo and showed no change between groups (H, N = 3–4). In vitro, p53 mRNA expression was significantly increased with IAA exposure (I, N = 9). Negative control for IHC stains (inset in panels C and F). Welsh’s ANOVA for Cdkn1a in vivo, p = .005, *p ≤ .05 by Dunnet’s T3 post-hoc analysis. One-way ANOVA for Cdkn1a in vitro, p < .0001, *p ≤ .05; **p ≤ .01; ***p ≤ .001; ****p ≤ .0001 by Dunnett’s post-hoc analysis. T-test for p53, *p ≤ .05. Scale bars = 75 μM (A, B), Scale bars = 250 μM (D, E).

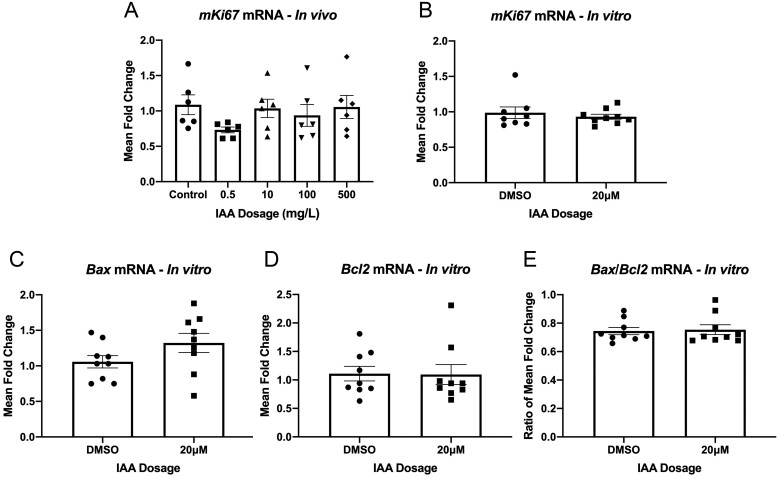

Iodoacetic Acid Had No Effect on Proliferation as Assessed by mKi67 mRNA Levels, or Apoptosis Assessed via Bax and Bcl2 Levels

As P21 is a cell cycle arrester, we wanted to determine the influence of its activation by IAA on proliferation and cell death. mRNA of the proliferative marker Ki67 (mKi67) was unchanged by any IAA exposure level in vivo (Figure 6A) or in our explant culture (Figure 6B). P21 is known to have a dynamic influence on apoptosis, at times promoting it and at others inhibiting it (Kreis et al., 2019). To observe whether IAA altered cell death, we assessed expression levels of the pro-apoptotic marker Bax (Figure 6C) and the anti-apoptotic marker Bcl2 (Figure 6D), neither of which were altered by IAA exposure to 20 μM IAA in vitro. Often, the ratio of Bax to Bcl2 mRNA is reported as an indicator of apoptosis in the tissue. This ratio was not altered by IAA in our in vitro context (Figure 6E).

Figure 6.

IAA had no effect on proliferation as assessed by mKi67 mRNA levels, nor did affect apoptosis assessed via Bax and Bcl2 levels in vitro. qPCR analysis for the proliferative marker Ki67 (mKi67) was unchanged in any IAA exposure level in vivo (A; N = 6). mKi67 expression was similarly unaffected by IAA exposure in explant culture (B; N = 8–9). mRNA levels for the pro-apoptotic Bax (C; N = 9) and the anti-apoptotic Bcl2 (D; N = 9) were unchanged in vitro. The ratio of Bax to Bcl2 was also unchanged by IAA exposure in vitro (E; N = 9).

DISCUSSION

Epidemiological studies have linked increased DBP exposure to negative impacts on sperm morphology and concentration in males, and menstrual cycle length and follicular phase length in women (Villanueva et al., 2015). In cell lines and mouse ovarian cells, IAA has been shown to have toxic effects. However, little is known about neuroendocrine contributions to negative reproduction-related outcomes with IAA exposure. Thus, we studied how IAA affects the hypothalamus and pituitary to better understand its potential to disrupt the HPG axis.

In hypothalamic tissue harvested from mice exposed to a range of IAA dosages in their drinking water, we first focused on Kiss1 in the ARC and the AVPV. IAA reduced expression of Kiss1 mRNA in the ARC (0.5 and 10 mg/l IAA), the seat of the GnRH pulse generator. Kiss1 mRNA reduction is not likely due to local changes in autoregulatory peptides because Tac2 and Pdyn were not affected by IAA exposure (Moore et al., 2018; Navarro et al., 2009). Additionally, ovarian estrogen, acting through estrogen receptor-α (Esr1), is one of the primary negative regulators of Kiss1 ARC expression. However, we found no change in Esr1 mRNA with IAA and analysis of sera collected in a parallel study indicated estradiol was unchanged at the dosages at which we observed Kiss1 reduction (Gonsioroski et al., 2021). These data suggest that Kiss1 repression by IAA occurs either directly on Kiss1 or through an unidentified mechanism. Despite the change in Kiss1, we found no change in Gnrh1 mRNA in response to IAA, although we did not explore protein level changes or shifts in pulsatility. Collectively, our data reveal IAA disrupts hypothalamic contributions to the HPG via reducing ARC Kiss1 mRNA expression.

In the pituitary, the 2 central factors in reproductive control are FSH and LH, which influence ovarian steroid hormone production, and guide follicle maturation and ovulation, respectively. Thus, they are prime targets for HPG axis interference. Both in vivo (10 mg/l IAA) and in vitro (20 μM IAA), Fshb mRNA expression and the number of FSHβ-positive cells were significantly reduced with IAA exposure. Seeing changes in both contexts suggest IAA targets the pituitary directly. We cannot be certain how these findings translate to circulating FSH levels. The most accurate assessment would require frequent serum collections representing the entire estrous cycle—during which peak FSH expression occurs in the early morning of estrus (Ongaro et al., 2021)—rather than the single diestrus time point collected from these mice (Gonsioroski et al., 2021). However, a reduction in both mRNA and protein suggests the possibility that the ovaries could see reduced FSH levels. With long-term exposure, such a reduction could lead to impaired ovarian follicle development and reduced ovarian estradiol synthesis (Bernard et al., 2010). This could potentially compound the direct ovarian impact of IAA revealed by prior in vitro studies (Gonsioroski et al., 2020; Jeong et al., 2016). We do not know the ultimate consequence of this observation for fertility in general; however, there was a borderline-significant change in estrous cyclicity with the same IAA exposure in which we observe FSHβ/Fshb reduction, potentially indicating a contribution of pituitary effects to HPG dysregulation (Gonsioroski et al., 2021).

The mechanism by which IAA leads to these changes in FSHβ/Fshb is currently unknown. Paradoxically, if Kiss1 mRNA reduction were the causal mechanism for the reduction in vivo, it should lead to an increase, not a decrease in expression. Similarly, the change does not appear to be due to ovarian estradiol feedback; levels were unaffected in the dosages at which we observed FSHβ/Fshb reductions (Gonsioroski et al., 2021). Pursuing this in future studies will provide valuable insight.

Interestingly, the number of LHβ-positive cells and Lhb mRNA in vivo were unchanged by IAA. One of the primary mechanisms by which gonadotropins are regulated is through GnRH pulse frequency; LH synthesis is favored by quick pulses and FSH synthesis is favored by slow ones (Coss, 2018; Thompson and Kaiser, 2014; Tsutsumi and Webster, 2009). Observing a shift in FSHβ, but not LHβ expression suggests a regulatory mechanism specific to FSH and that ovulatory and other LH-driven reproductive functions may be spared. Several FSH-regulating factors that could underly this outcome have been characterized. Ovarian and pituitary activins promote FSH synthesis, whereas ovarian inhibins and ubiquitously expressed follistatins inhibit it (Bernard et al., 2010). Analysis of sera harvested from the same mice used in this study showed no difference in inhibin B with IAA exposure (Gonsioroski et al., 2021) although inhibin A was not assessed. Future experiments will be vital to clarifying the mechanisms by which IAA influences FSHβ/Fshb.

In addition to disrupting hormone production, IAA has been shown to have direct toxic influences on ovarian tissue and in various cell types. Therefore, we examined the potential for cyto- and genotoxic effects in the pituitary both systemically in vivo and directly in vitro. IAA exposure substantially increased DNA damage in vitro and at 500 mg/l IAA in vivo, as evidenced by an increase in cells immunostaining for γH2AX. This finding is in line with other studies, most notably genotoxicity observed in ovarian cells (Plewa et al., 2010; Jiao et al., 2021). Aggregated DNA damage has been linked to premature cellular aging, which can include telomere attrition, changes in gene expression, and impaired DNA damage repair (López-Otín et al., 2013). Further, evidence suggests that DNA damage is a key contributor to pituitary tumorigenesis (Ben-Shlomo et al., 2020; Chesnokova et al., 2008; Chesnokova and Melmed, 2020). These prior data would suggest that IAA could contribute to a tumorigenic environment or potentially to dysfunction resulting from the consequences of premature aging in the pituitary, especially with persistent exposure.

DNA damage induces the cell-cycle arrester P21 (Cdkn1a), which is important in the context of pituitary response to cellular damage. Studies suggest it aids in constraining pituitary tumor growth and may contribute to the observation that pituitary tumors, unlike most types of tumors, are frequently benign (Chesnokova et al., 2008; Chesnokova and Melmed, 2009). In 2 studies from our lab on pituitary phytoestrogen exposure, Cdkn1a was increased (Weis and Raetzman, 2016, 2019), suggesting it is part of the pituitary response to select toxicant exposure. Expression of Cdkn1a was significantly increased following IAA exposure both in vivo and in vitro. These data mirror the effect that IAA had on Cdkn1a expression in ovarian follicle cultures (Gonsioroski et al., 2020) although not in in vivo ovaries collected from the same animals in which we see induction in the pituitary (Gonsioroski et al., 2021). Assessing P21-immunopositivity in vitro revealed a marked increase in P21-positive cells. In vivo there was no significant difference in the number of P21-positive cells. It may be the case that in the systemic context, IAA affects P21 at too subtle a degree to be observable in our assay. However, with longer-term exposure, as could be the case with everyday drinking water, P21 protein could be induced, especially because we do see consequences at the mRNA level. DNA damage induces P21 through p53, P21’s primary transcriptional regulator (Huarte, 2016; Jung et al., 2010; Karimian et al., 2016). Interestingly, we observed an increase in p53 mRNA expression in vitro where DNA damage and P21 were obviously induced, but not in vivo where P21 changes were not apparent. This might suggest that IAA introduces DNA damage which then invokes P21 although this will require future study.

P21 pathway’s primary action is to arrest the cell-cycle, decreasing proliferation. It can also stimulate DNA repair and apoptosis (Abbas and Dutta, 2009; Herranz and Gil, 2018). We assessed both proliferative (mKi67) and apoptosis-related mRNAs (Bax and Bcl2). Surprisingly, mKi67 was not altered in vivo or in vitro, where P21 induction was obvious at both the mRNA and protein levels. P21/Cdkn1a induction by IAA may be insufficient to lead to cell-cycle arrest in enough cells to detectably alter mRNA. In adulthood, cells in the rodent pituitary show limited proliferation (Laporte et al., 2020) and this may contribute to subtlety of effects. In vitro analysis showed that apoptosis was also not affected by IAA exposure. These data would suggest that IAA-induced DNA damage and P21 activation would not ultimately affect the number of cells in the tissue, but may still affect their function through P21’s involvement in gene transcription (Abbas and Dutta, 2009). Interestingly, it also shows that unlike in previous cell culture and ovarian experiments, IAA may not be cytotoxic in the pituitary (Dad et al., 2013; Gonsioroski et al., 2020, 2021; Plewa et al., 2004, 2010). Notably, body, uterine, ovarian, and liver weights were unchanged in these mice, suggesting any cytotoxicity in these tissues is also insufficient to change overall organ weight (Gonsioroski et al., 2021).

It appears that the mechanisms by which IAA induced DNA damage and P21/Cdkn1a, and those by which it reduced FSHβ/Fshb are independent, as they occurred at different exposure levels. It is common when studying toxicants to see lower dose effects that are not observed at higher dosages and vice versa (Vandenberg, 2014). One proposed mechanism for this involves the toxicant interfering with hormone receptor activity until a certain exposure concentration at which the body recognizes it and clears it from the system relieving the burden, or shuts down the receptor, reversing the effect. At higher levels, the toxicant might induce more broad toxic effects such as genotoxicity, as is reflected in our DNA damage results, through a mechanism distinct from how it acts at lower doses.

Prior to this study, virtually nothing was known about how IAA influences neuroendocrine systems. Our data reveal that IAA decreases the expression of key mRNA related to reproduction including kisspeptin in the ARC of the hypothalamus and Fshb in the pituitary, as well as reduces the number of FSHβ-positive cells, a key component of the hormone necessary for guiding ovarian follicle maturation. We have also shown that IAA can introduce DNA damage and induce P21/Cdkn1a expression in the pituitary. These data provide an important foundation for further study of IAA as a reproductive environmental toxicant.

DECLARATION OF CONFLICTING INTERESTS

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Tyler Smith for his assistance with immunohistochemistry image analysis.

FUNDING

This work was supported by NIH R21 ES028963 and NIH T32 ES007326.

REFERENCES

- Abbas T., Dutta A. (2009). P21 in cancer: Intricate networks and multiple activities. Nat. Rev. Cancer 9, 400–414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen J. M., Plewa M. J., Wagner E. D., Wei X., Bollar G. E., Quirk L. E., Liberatore H. K., Richardson S. D. (2021). Making swimming pools safer: Does copper−silver ionization with chlorine lower the toxicity and disinfection byproduct formation? Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, DOI: 10.1021/acs.est.0c06287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Shlomo A., Deng N., Ding E., Yamamoto M., Mamelak A., Chesnokova V., Labadzhyan A., Melmed S. (2020). DNA damage and growth hormone hypersecretion in pituitary somatotroph adenomas. J. Clin Invest. 130, 5738–5755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard D. J., Fortin J., Wang Y., Lamba P. (2010). Mechanisms of FSH synthesis: What we know, what we don’t, and why you should care. Fertil. Steril. 93, 2465–2485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesnokova V., Melmed S. (2020). Peptide hormone regulation of DNA damage responses. Endocr. Rev. 41, 519–537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesnokova V., Melmed S. (2009). Pituitary tumour-transforming gene (PTTG) and pituitary senescence. Hormone Res. 71, 82–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesnokova V., Zonis S., Kovacs K., Ben-Shlomo A., Wawrowsky K., Bannykh S., Melmed S. (2008). p21Cip1 restrains pituitary tumor growth. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 17498–17503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury S., Al-hooshani K., Karanfil T. (2014). Disinfection byproducts in swimming pool: occurrences, implications and future needs. Water Res. 53, 68–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coss D. (2018). Regulation of reproduction via tight control of gonadotropin hormone levels. Mol Cell. Endocrinol. 463, 116–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dad A., Jeong C. H., Pals J. A., Wagner E. D., Plewa M. J. (2013). Pyruvate remediation of cell stress and genotoxicity induced by haloacetic acid drinking water disinfection by-products. Environm. Mol. Mutagen. 54, 629–637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong H., Qiang Z., Richardson S. D. (2019). Formation of iodinated disinfection byproducts (I-DBPs) in drinking water: Emerging concerns and current issues. Acc. Chem. Res. 52, 896–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg L. B., Aujla P. K., Raetzman L. T. (2011). Persistent expression of activated Notch inhibits corticotrope and melanotrope differentiation and results in dysfunction of the HPA axis. Dev Biol. 358, 23–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonsioroski A., Meling D. D., Gao L., Plewa M. J., Flaws J. A. (2020). Iodoacetic acid inhibits follicle growth and alters expression of genes that regulate apoptosis, the cell cycle, estrogen receptors, and ovarian steroidogenesis in mouse ovarian follicles. Reprod. Toxicol. 91, 101–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonsioroski A., Meling D. D., Gao L., Plewa M. J., Flaws J. A. (2021). Iodoacetic acid affects estrous cyclicity, ovarian gene expression, and hormone levels in mice. Biol. Reprod. DOI: 10.1093/BIOLRE/IOAB108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gore A. C., Chappell V. A., Fenton S. E., Flaws J. A., Nadal A., Prins G. S., Toppari J., Zoeller R. T. (2015). EDC-2: The Endocrine Society’s second scientific statement on endocrine-disrupting chemicals. Endocr. Rev. 36, E1–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herranz N., Gil J. (2018). Mechanisms and functions of cellular senescence. J. Clin. Invest. 128, 1238–1246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huarte M. (2016). P53 partners with RNA in the DNA damage response. Nat. Genet. 48, 1298–1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong C. H., Gao L., Dettro T., Wagner E. D., Ricke W. A., Plewa M. J., Flaws J. A. (2016). Monohaloacetic acid drinking water disinfection by-products inhibit follicle growth and steroidogenesis in mouse ovarian antral follicles in vitro. Reprod. Toxicol. 62, 71–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiao X., Gonsioroski A., Flaws J. A., Qiao H. (2021). Iodoacetic acid disrupts mouse oocyte maturation by inducing oxidative stress and spindle abnormalities. Environ. Poll. 268, 115601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung Y. S., Qian Y., Chen X. (2010). Examination of the expanding pathways for the regulation of p21 expression and activity. Cell. Signal. 22, 1003–1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karimian A., Ahmadi Y., Yousefi B. (2016). Multiple functions of p21 in cell cycle, apoptosis and transcriptional regulation after DNA damage. DNA Repair 42, 63–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreis N. N., Louwen F., Yuan J. (2019). The multifaceted p21 (Cip1/Waf1/CDKN1A) in cell differentiation, migration and cancer therapy. Cancers 11, 1220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D. H., Park C. G., Kim Y. J. (2020). Characterizing the potential estrogenic and androgenic activities of two disinfection byproducts, mono-haloacetic acids and haloacetamides, using in vitro bioassays. Chemosphere 242, 125198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laporte E., Vennekens A., Vankelecom H. (2020). Pituitary remodeling throughout life: Are resident stem cells involved? Front. Endocr. 11, 604519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long K., Sha Y., Mo Y., Wei S., Wu H., Lu D., Xia Y., Yang Q., Zheng W., Wei X. (2021). Androgenic and teratogenic effects of iodoacetic acid drinking water disinfection byproduct in vitro and in vivo. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 3835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-Otín C., Blasco M. A., Partridge L., Serrano M., Kroemer G. (2013). The hallmarks of aging. Cell 153, 1194–1217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore A. M., Coolen L. M., Porter D. T., Goodman R. L., Lehman M. N. (2018). KNDy cells revisited. Endocrinology 159, 3219–3234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro V. M., Gottsch M. L., Chavkin C., Okamura H., Clifton D. K., Steiner R. A. (2009). Regulation of gonadotropin-releasing hormone secretion by kisspeptin/dynorphin/neurokinin B neurons in the arcuate nucleus of the mouse. J. Neurosci. 29, 11859–11866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ongaro L., Alonso C. A. I., Zhou X., Brûlé E., Li Y., Schang G., Parlow A. F., Steyn F., Bernard D. J. (2021). Development of a highly sensitive ELISA for measurement of FSH in serum, plasma, and whole blood in mice. Endocrinology 162, bqab014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pals J., Attene-Ramos M. S., Xia M., Wagner E. D., Plewa M. J. (2013). Human cell toxicogenomic analysis linking reactive oxygen species to the toxicity of monohaloacetic acid drinking water disinfection byproducts. Environ. Sci. Technol. 47, 12514–12523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Franklin K. (2019). Paxinos and Franklin’s the Mouse Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates, Compact, 5th ed.Academic Press, Cambridge, MA. [Google Scholar]

- Plewa M. J., Simmons J. E., Richardson S. D., Wagner E. D. (2010). Mammalian cell cytotoxicity and genotoxicity of the haloacetic acids, a major class of drinking water disinfection by-products. Environ. Mol. Mutagen. 51, 871–878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plewa M. J., Wagner E. D., Richardson S. D., Thruston A. D., Woo Y. T., McKague A. B. (2004). Chemical and biological characterization of newly discovered iodoacid drinking water disinfection byproducts. Environ. Sci. Technol. 38, 4713–4722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson S. D. (2005). New disinfection by-product issues: Emerging DBPs and alternative routes of exposure. Global NEST J. 7, 43–60. [Google Scholar]

- Srivastav A. L., Patel N., Chaudhary V. K. (2020). Disinfection by-products in drinking water: Occurrence, toxicity and abatement. Environ. Poll. 267, 115474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson I. R., Kaiser U. B. (2014). GnRH pulse frequency-dependent differential regulation of LH and FSH gene expression. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 385, 28–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsutsumi R., Webster J. G. (2009). GnRH pulsatility, the pituitary response and reproductive dysfunction. Endocr. J. 56, 729–737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandenberg L. N. (2014). Non-monotonic dose responses in studies of endocrine disrupting chemicals: Bisphenol A as a case study. Nonlinear. Biol. 12, 259–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villanueva C. M., Cordier S., Font-Ribera L., Salas L. A., Levallois P. (2015). Overview of disinfection by-products and associated health effects. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2, 107–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei X., Wang S., Zheng W., Wang X., Liu X., Jiang S., Pi J., Zheng Y., He G., Qu W. (2013). Drinking water disinfection byproduct iodoacetic acid induces tumorigenic transformation of NIH3T3 cells. Environ. Sci. Technol. 47, 5913–5920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weis K. E., Raetzman L. T. (2016). Isoliquiritigenin exhibits anti-proliferative properties in the pituitary independent of estrogen receptor function. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 313, 204–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weis K. E., Raetzman L. T. (2019). Genistein inhibits proliferation and induces senescence in neonatal mouse pituitary gland explant cultures. Toxicology 427, 152306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia Y., Mo Y., Yang Q., Yu Y., Jiang M., Wei S., Lu D., Wu H., Lu G., Zou Y., et al. (2018). Iodoacetic acid disrupting the thyroid endocrine system in vitro and in vivo. Environ. Sci. Technol. 52, 7545–7552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]