Abstract

Background

Exclusive breastfeeding is defined as the practice of providing only breast milk for an infant for the first 6 months of life without the addition of any other food or water, except for vitamins, mineral supplements, and medicines. Findings are inconsistent regarding the prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding in Ethiopia. Full-time maternal employment is an important factor contributing to the low rates of practice of exclusive breastfeeding. Empowering women to exclusively breastfeed, by enacting 6 months’ mandatory paid maternity leave can increase the rate of exclusive breastfeeding in the first 6 months of life up to 50%. The purpose of this review was to estimate the pooled prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding and its association with full-time maternal employment in the first 6 months of life for infants in the context of Ethiopia.

Methods

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guideline was used in this systematic review and meta-analysis. All observational studies reporting the prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding and its association with maternal employment in Ethiopia were considered. The search was conducted from 6 November 2020 to 31 December 2020 and all papers published in the English language from 1 January 2015 to 31 December 2020 were included in this review.

Results

Forty-five studies were included in the final analysis after reviewing 751 studies in this meta-analysis yielding the pooled prevalence of EBF 60.42% (95% CI 55.81, 65.02) at 6 months in Ethiopia. Those full-time employed mothers in the first 6 months were 57% less likely to practice exclusive breastfeeding in comparison to mothers not in paid employment in Ethiopia (OR 0.43; 95% CI 0.31, 0.61).

Conclusions

Full-time maternal employment was negatively associated with the practice of exclusive breastfeeding in comparison to unemployed mothers. The prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding in Ethiopia is low in comparison to the global recommendation. The Ethiopian government should implement policies that empower women. The governmental and non-governmental organizations should create a conducive environment for mothers to practice exclusive breastfeeding in the workplace.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13006-021-00432-x.

Keywords: Prevalence, Exclusive breastfeeding, Meta-analysis, Maternal employment, Ethiopia

Background

Breastfeeding is a core part of the 2030 agenda for Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) which is linked with many targets of the SDGs, especially with the third target which deals with ending preventable maternal and neonatal death [1]. Exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) is defined as the practice of providing only breast milk for an infant for the first 6 months of life without the addition of any other food or water, except for vitamins, mineral supplements, and medicines [2]. Currently, the global prevalence of EBF for infants aged zero to 6 months is only 38%, which is far behind to making EBF during the first 6 months of life the norm for infant feeding. Researchers indicate that 11.6% of mortality in children under 5 years of age was contributed by non-exclusive breastfeeding [3, 4].

In 2012, the World Health Assembly endorsed a comprehensive implementation plan on maternal, infant, and young child nutrition with six specified global nutrition targets for 2025.The fifth target aims to increase the rate of EBF in the first 6 months up to 50% and only 31 of 194 countries were practicing according to this endorsement in 2018 [5, 6]. According to the 2015 UNICEF report, the worldwide rate of EBF is low compared to the 2012 World Health Assembly endorsement, with the following EBF rates reported in western and central Africa (25%), East Asia and Pacific (30%), South Asia (47%), Central America and the Caribbean (32%), eastern and southern Asia (51%), least developed countries (46%) and worldwide (38%) respectively [7]. Between 1985 and 1995, global rates of EBF were raised by 2.4%, however, 25 countries raised their rates of EBF by 20% or more after 1995 [8, 9]. Similarly, Cambodia and Malawi showed an increment of EBF from 11 to 74% and 3 to 71% respectively between 1992 and 2010 [10].

Another study conducted in 13 western African countries and sub-Saharan countries showed the prevalence of EBF for infants under 6 months of age ranges from 13.0% in Côte d’Ivoire to 58.0% in Togo and 45.2% in sub-Saharan countries respectively [11, 12]. Besides this, according to the 2016 Ethiopian demographic health survey (EDHS), the prevalence of EBF for infants under 6 months was 58% [13]. According to a study conducted in Latin America and the Caribbean countries, Bangladesh and others, EBF for the first 3 months of life can prevent 55% of infant deaths related to diarrheal disease and acute respiratory infection [14–17].

Similarly, a study conducted in Ghana and Ethiopia showed that the risk of neonatal death was higher for infants with non-exclusive breastfeeding [18, 19]. Inadequate rates of EBF result from different factors such as inadequate maternity leave (shorter paid maternity leave which enforces mother to return to work early before 6 months of infant’s age) [20, 21], workplace policies that don’t support a woman’s ability to breastfeed when she returns to work [22], and caregiver and societal belief which favor non-exclusive breastfeeding before 6 months of age of infants [23–25]. Some evidence showed that empowering women to exclusively breastfeed, by enacting 6 months’ mandatory paid maternity leave, as well as policies that encourage women to breastfeed in the workplace and public can increase the rate of EBF in the first 6 months of life up to 50% [26, 27]. Another piece of evidence showed that longer paid maternity leave helps the mothers to practice EBF effectively [28].

The Indian and Vietnamese governments have been successfully protecting EBF by the implementation of supportive policies that guarantee mothers get 6 months of paid maternity leave and by prohibiting the use of marketing breast milk substitutes with legislation before 6 months of infant’s age [29, 30]. Whereas, contrary to the World Health Organization’s recommendation, the Constitution of Ethiopia and Labour Proclamation recommends employed mothers get fully paid maternity leave of 120 working days only (30 days antenatal and 90 days postnatal leave) and the proclamation doesn’t support women to breastfeed in the workplace and the public area after they return to work [31].

In Ethiopia, many studies have been conducted to determine the prevalence of EBF and its associated factors between 1 January 2015 to 31 December 2020. These studies showed that different maternal and health service-related factors influenced the practice of EBF in addition to maternal employment [32–50]. We selected maternal employment from other factors to investigate its effect on the practice of EBF because of the following reasons: The first reason is that maternal employment was an important factor, which ultimately influences EBF, especially in our country where the Labour Proclamation recommends only 120 working days paid maternity leave which forces mothers to return quickly to their job before 6 months after delivery. The second reason is that the primary studies conducted previously found inconsistent evidence regarding the effect of maternal employment on EBF. Most showed a negative association of maternal employment with EBF with the presence of great variation among them [32–37, 40–50]. Only two studies [38, 39] showed a positive association of maternal employment with EBF.

As far as we are aware, even if there were small and fragmented studies, there is no published systematic review and meta-analysis in Ethiopia, which has investigated the pooled prevalence of EBF and its association with maternal employment using primary studies published between 1 January 2015 to 31 December 2020, which is in line with the third target of the SDGs by 2030. The objective of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to estimate the pooled prevalence of EBF and its association with full-time maternal employment in the context of Ethiopia. This systematic review will generate concrete evidence that helps policymakers and program planners to make an appropriate intervention and remold some policies concerning maternal employment and the practice of EBF for the benefit of mothers and infants in Ethiopia.

Methods

The current systematic review and meta-analysis was reported by using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) [51] guideline to determine the pooled prevalence of EBF practice and its association with maternal employment.

Research question / hypothesis according to CoCoPop (condition, context, population) criteria

What is the prevalence of Exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) and its association with full-time maternal employment among mothers with infants less than 5 years of age in the context of Ethiopia?

Searching strategies

The international databases, including PubMed, Google Scholar, Science Direct, and Cochrane library, Scopus, CINAHL, and Web of Science were systematically searched. The search was conducted using the following keywords: “Prevalence”, “Exclusive Breastfeeding”, “Feeding, Breast”, “Breastfeeding”, “Breastfeeding, exclusive”, “Factors”, “Determinants”, “Maternal employment”, and Ethiopia. The search terms were used separately and in combination using Boolean operators including “OR” or “AND” and the search was conducted from 6 November 2020 to 31 December 2020. All papers published until 31 December 2020 were included in this review.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria

Study area: Only studies conducted in Ethiopia.

Publication condition: Articles published in peer-reviewed journals.

Study design: All observational study designs (Cross-sectional, case-control, and cohort) reporting the prevalence of EBF or associations between maternal employments with EBF were considered.

The outcome of interests: Studies reported data on the prevalence of EBF or the association between EBF and maternal employment were considered.

Language: Articles reported in the English language were considered.

Publication year: only studies published from 1 January 2015 to 31 December 2020 were considered.

Exclusion criteria

Study conducted in women with HIV / AIDS, preterm newborn, and newborn in an intensive care unit

Study with abstracts without full text and qualitative studies, symposium / conference and case reports.

Articles, which were not fully accessed, after at least two email contacts with the primary author, were excluded and experimental, intervention, and review articles were excluded.

Outcome measurement

This systematic review has two main outcomes. The first one is the prevalence of EBF practice, which is defined as the practice of providing only breast milk for an infant for the first 6 months of life without the addition of any other food or water, except for vitamins, mineral supplements, and medicines [2]. The prevalence was calculated from each primary study by dividing the number of women breastfeeding exclusively by the total number of all women who had participated in the study multiplied by 100. The second outcome was to investigate the association between full-time maternal employment and the practice of EBF for which we calculated the Ln odds ratio (Ln OR) meaning the base e logarithm or (loge (OR)) results of the primary studies that examined the relationship between maternal employment and practice EBF.

Data extraction

Two authors (GE and YM) independently assessed the quality of each original study and any disagreements at the time of data abstraction were resolved through discussion and consensus. Data were extracted using a standardized data extraction format, which was adopted from the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) data extraction format [52]. The following data such as primary authors, publication year, and study area, study design, sample size, the prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding, the quality score of each study, the association between maternal employment and EBF with their respective odds ratio (OR), characteristics of study participants and response rate were extracted.

Quality assessment

The Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal tools for use in JBI Systematic Reviews (JBI-MAStARI) was used for critical appraisal of studies [53]. The tool has eight major criteria for critical appraisal of each primary study. Accordingly, primary studies with a score of equal or greater than 50% and above were included in the meta-analysis research.

Statistical analysis

Data were extracted in Microsoft Excel format and analysis was done using STATA version 11 software. We calculated the standard error for each original study using the binomial distribution format. Heterogeneity regarding reported prevalence was assessed by computing p-values for Cochrane Q-statistics and I2 tests. I2 test statistics of 25, 50, and 75% were declared as low, moderate, and high heterogeneity respectively [54]. The test statistic showed that there was significant heterogeneity among the included studies (98.8%; p = < 0.001), and because of this a random-effects meta-analysis model was used to estimate the DerSimonian and Laird pooled effect. To minimize the random variations between primary studies, subgroup analysis was done by region in Ethiopia, sample size, and publication year of primary studies. Besides the above, univariate meta-regression was conducted by considering the same three subgroups as covariates to identify the possible sources of heterogeneity, but none was found to be statistically significant.

We checked publication bias by funnel plot subjectively and Egger’s and Begg’s tests objectively; a p-value of less than 0.05 was used to declare the statistical significance of publication bias [55]. For this meta-analysis pooled prevalence of EBF with a 95% confidence interval (CI) was presented with the forest plot. Accordingly, the size of each box corresponds to the weight of the study, the crossed line refers to a 95% confidence interval of the study, and the Ln OR which is the base e logarithm was applied to examine the association between maternal employment and EBF in Ethiopia.

Results

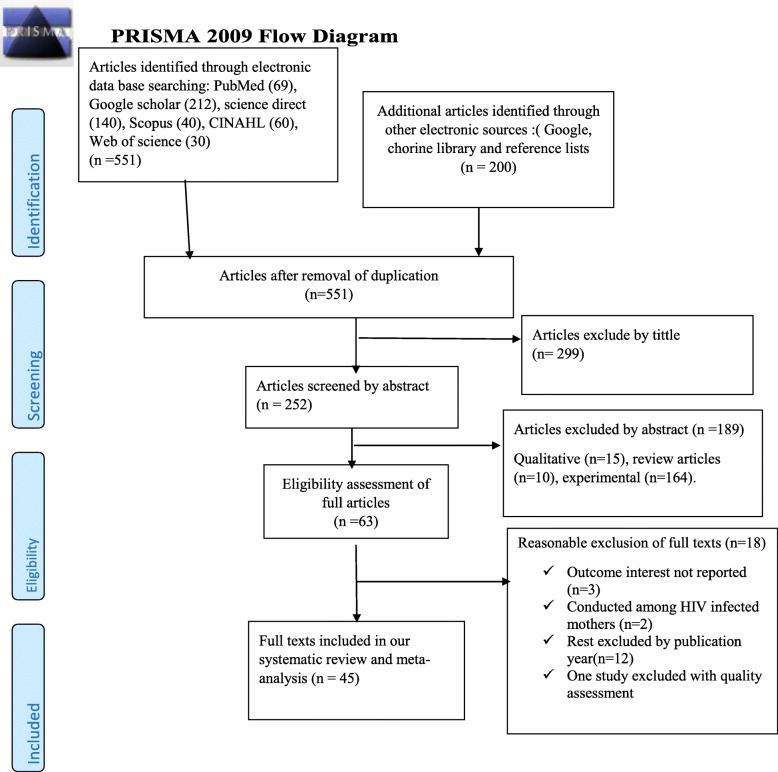

As described in Fig. 1, 751 studies were identified regarding EBF in Ethiopia through PubMed, Google Scholar, Science Direct, Scopus, CINAHL, Web of Science, and others in the first step. Then 200 studies were excluded because of duplication. From the remaining 551 studies, a further 299 articles were excluded as being not relevant to this review on the basis of their titles. The remaining 252 studies were screened by their abstracts yielding an additional 189 studies to be excluded. Moreover, 63 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility based on the preset inclusion criteria, and from these, 18 articles were excluded due to the inclusion criteria. Finally, 45 studies fulfilled the inclusion criteria and were included in the systematic review and meta-analysis.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of studies included in systematic review and meta-analysis, 2020

As shown in Table 1, all 45 of these studies were published between 1 January 2015 to 31 December 2020. Regarding study design most 42 of the studies are cross-sectional study designs. The sample size of the studies ranges from 226 to 5227. The lowest prevalence (29.29%) of EBF was observed in a study conducted in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia [72] whereas the highest prevalence (87.84%) was observed in a study conducted in the Southern Nations, Nationalities, and Peoples (SNNP) and Tigray region, among rural mothers in Ethiopia [81]. From nine regions of Ethiopia, seven regions and two council cities were represented in this meta-analysis. Fifteen of the studies were from Amhara [33–42, 58, 59, 75–77] two from Addis Ababa [64, 73], four from Affar [34, 56, 57, 74] four from Oromia [44, 60, 61, 80], twelve from SNNP [45–47, 62–65, 67–70, 72], one from Tigray [71], two from Somalia [48, 79], two from Harari [43, 78], one from nationwide [49], one from Diredawa [50] and one from SNNP and Tigray [81]. No studies were reported from Benishangul Gumiz and Gagmbela in this review research. Regarding the quality score of each primary study, the score was between the lowest (4) and highest (8) (Additional file 1) and almost all primary studies had a sufficient response rate.

Table 1.

Descriptive summary of 45 studies included in the meta-analysis for estimation of pooled prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding in Ethiopia, 2020

| s.no | Primary author | Publication year | Study area | Study design | Sample size | Prevalence of EBF (%) | Response rate (%) | Association of maternal employment with EBF (OR) | Study participants characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Tsegaye et al. [32] | 2019 | Affar | cross-sectional | 618 | 55 | 98 | 0.8 | mothers who had a child age < 6 months |

| 2 | Liben et al. [56] | 2016 | Affar | cross-sectional | 333 | 81 | 96.2 | – | Mothers who had child age < 6 months |

| 3 | Gizaw et a [57] | 2017 | Affar | cross-sectional | 254 | 74 | 98.5 | – | Mothers who had child age between 6 and 24 months during the first 6 months of life |

| 4 | Asemahagn [33] | 2016 | Amhara | cross-sectional | 332 | 78.9 | 96 | 0.6 | Mothers who had child age 0-6 months |

| 5 | Belachew et al. [34] | 2018 | Amhara | cross-sectional | 472 | 86.44 | 94.6 | 0.334 | Mothers who had child age < 6 months |

| 6 | Biks et al. [58] | 2015 | Amhara | Case-control | 1769 | 30.69 | NR | – |

mothers who exclusively breastfed their infants for the first six months were selected As cases. |

| 7 | Tariku et al. [59] | 2017 | Amhara | Demographic Surveillance | 5227 | 54.5 | NR | – | mothers with children aged less than 59 months |

| 8 | Asfaw et al. [35] | 2015 | Amhara | cross-sectional | 634 | 68.6 | 100 | 0.36 | Mothers who had child age < 12 months |

| 9 | Yeshamble Sinshaw et al. [36] | 2015 | Amhara | cross-sectional | 483 | 61.28 | 100 | 0.4 | Mothers who had child age < 6 months |

| 10 | Mekuria et al. [37] | 2015 | Amhara | cross-sectional | 413 | 60.77 | 97.6 | 0.5 | Mothers who had child age < 6 months |

| 11 | Arage et al. [38] | 2016 | Amhara | cross-sectional | 453 | 70.86 | 96.4 | 1.07 | Mothers who had child age < 6 months |

| 12 | Gebrie et al. [39] | 2019 | Amhara | cross-sectional | 254 | 46.45 | NR | 2.452 | mothers who had a child up to one year |

| 13 | Chekol et al. [40] | 2017 | Amhara | cross-sectional | 649 | 34.82 | 100 | 0.29 | mothers who had a child age 7–12 months |

| 14 | Hunegnaw et al. [41] | 2017 | Amhara | cross-sectional | 478 | 74.26 | 94.4 | 0.49 | mothers who had a child age 6–12 months |

| 15 | Tewabe et al. [42] | 2017 | Amhara | cross-sectional | 405 | 50.12 | 95.7 | 0.33 | Mother who had child age < 6 months |

| 16 | Iffa et al. [43] | 2018 | Harar | cross-sectional | 425 | 40.94 | 100 | 0.1 | mothers who had a child age 0–31 months |

| 17 | Bayissa Z B. et al. [44] | 2015 | Oromia | cross-sectional | 371 | 82.21 | 92.05 | 0.41 | mothers who had child age < 2 years |

| 18 | Kitesa et al. [60] | 2017 | Oromia | cross-sectional | 2222 | 44.32 | 100 | – | mothers who had a child age ≤ 12 months |

| 19 | Sasie D et al. [61] | 2017 | Oromia | cross-sectional | 410 | 70 | 97.4 | – | mothers who had a child age 0–23 months |

| 20 | Anjullo B et al. [62] | 2018 | SNNP | cross-sectional | 330 | 53.93 | 100 | – | mothers who had child age < 6 months |

| 21 | Muze Edris MD, et al. [45] | 2019 | SNNP | cross-sectional | 843 | 56.10 | 99.7 | 0.77 | mothers who had child age < 23 months |

| 22 | Gedion Asnake Azeze et al. [63] | 2019 | SNNP | cross-sectional | 403 | 64.76 | 97.8 | – | mothers who had child age 6-12 months |

| 23 | Sorato M [64] | 2017 | SNNP | cross-sectional | 226 | 40.70 | 92 | – | mothers who had child age 0–12 months |

| 24 | Reddy S et al. [65] | 2016 | SNNP | cross-sectional | 347 | 57.63 | 98.02 | – | mothers who had child age under2years |

| 25 | Bisrat et al. [66] | 2017 | SNNP | cross-sectional | 765 | 49.15 | 90.6 | – | mothers who had child age < 6 months |

| 26 | Sonko A et al. [67] | 2015 | SNNP | cross-sectional | 420 | 70.47 | 99.5 | – | mothers who had child age < 6 months |

| 27 | Adugna et al. [46] | 2017 | SNNP | cross-sectional | 529 | 60.86 | 97.8 | 0.4 | mothers who had child age0- 6 months |

| 28 | Alemu Earsido.et al. [68] | 2017 | SNNP | cross-sectional | 707 | 73.83 | 98 | – | mothers who had child age 0–12 months |

| 29 | Eskezyiaw Agedew Getahu.et al. [47] | 2017 | SNNP | cross-sectional | 562 | 40.56 | 99.11 | 0.44 | mothers who had child age 6-24 months |

| 30 | Lenja et al. [69] | 2016 | SNNP | cross-sectional | 396 | 78.03 | 98 | – | mothers who had child age < 6 months |

| 31 | Kelaye T [70] | 2017 | SNNP | cross-sectional | 421 | 64.84 | 100 | – | mothers who had child age < 6 months |

| 32 | Tadesse et al. [48] | 2019 | Somalia | cross-sectional | 558 | 71.14 | 95.7 | 0.04 | mothers who had child age 3-5 months |

| 33 | Teka et al. [71] | 2015 | Tigray | cross-sectional | 530 | 70.18 | 98 | – | mothers who had child age < 24 months |

| 34 | Shifraw et al. [72] | 2015 | Addis Ababa | cross-sectional | 635 | 29.29 | 98 | – | mothers who had child age ≤ 9 months |

| 35 | Elyas l [73] | 2017 | Addis Ababa | cross-sectional | 380 | 44.21 | 90.3 | – | mothers who were breastfeeding and visited the clinic pediatric clinic |

| 36 | Ahmed et al. [49] | 2019 | EDHS based data | (EDHS) base data | 3861 | 59.90 | NR | 0.94 | mothers who had child age 0–23 months |

| 37 | Nur et al. [74] | 2018 | Affar | cross-sectional | 400 | 78.3 | 97.3 | – | Mothers who had infants aged 0–6 months |

| 38 | Tilksew Ayalew [75] | 2020 | Amhara | cross-sectional | 400 | 57.3 | 95 | – | Mothers who had infants aged 0–6 months |

| 39 | Alebachew et al. [76] | 2017 | Amhara | cross-sectional | 332 | 49.7 | 100 | – | Mothers who had infants aged less than 2 years |

| 40 | Desalew et al. [50] | 2020 | Diredawa | cross-sectional | 704 | 81.1 | 100 | 0.52 (0.321,0.85) | Mothers who had infants aged 6–23 months |

| 41 | Bazie et al. [77] | 2019 | Amhara | cross-sectional | 608 | 46.7 | 95.9 | – | Mothers who had infants aged 6–12 months |

| 42 | Dibisa et al. [78] | 2020 | Harar | cross-sectional | 577 | 45.8 | 97.8 | – | Mothers who had infants aged less than 12 months |

| 43 | Musse Obsiye [79] | 2019 | Somalia | cross-sectional | 570 | 54.91 | 96.28 | – | Mothers of Infants Aged Under Six Months |

| 44 | Mamo et al. [80] | 2020 | Oromia | cross-sectional | 710 | 65.4 | 97.9 | – | Mothers who had infants aged 6–9 months |

| 45 | Hagos et al. [81] | 2020 | SNNP and Tigray | cross-sectional | 584 | 88.00 | 97.33 | – | Mothers of Infants Aged Under Six Months |

Meta-analysis

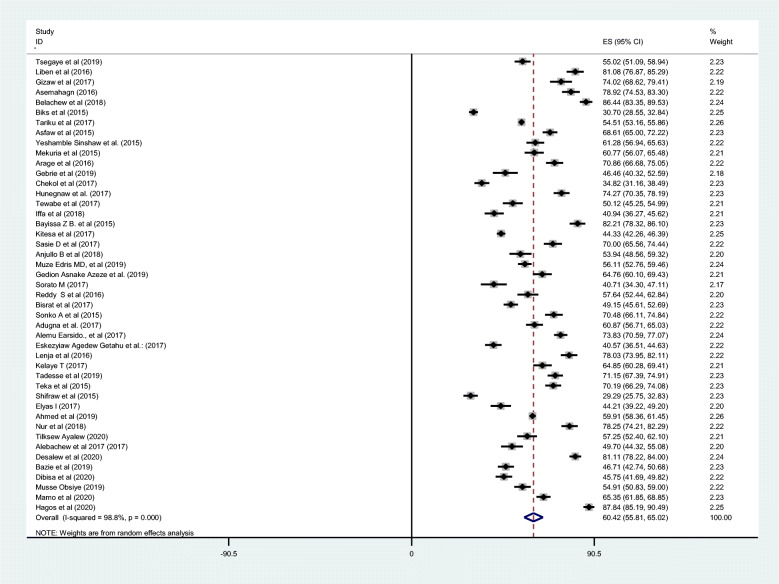

Pooled prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding in Ethiopia

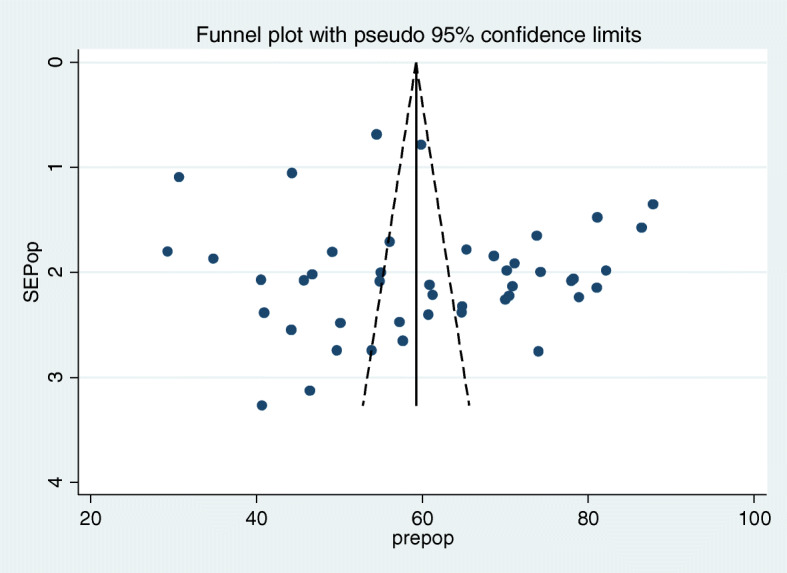

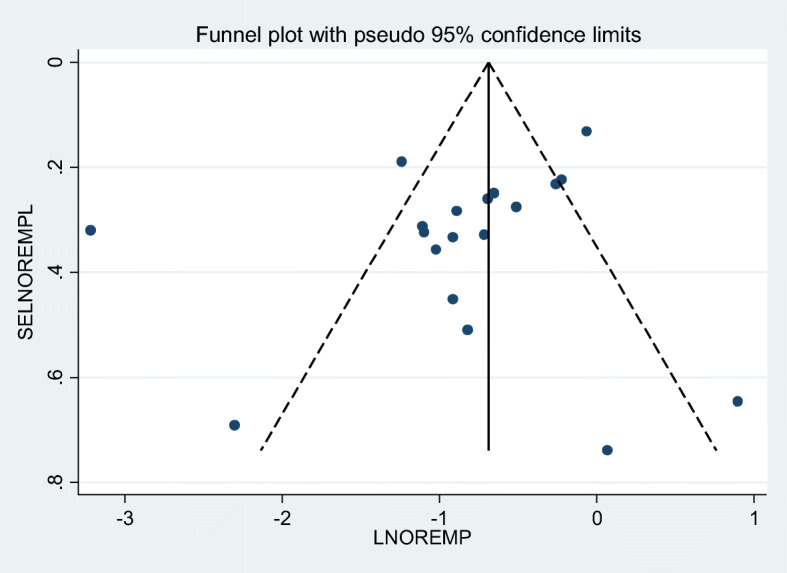

A total of 45 studies of 33,000 breastfeeding women were included to estimate the pooled prevalence of EBF in the current meta-analysis. The pooled prevalence of EBF at 6 months was 60.42% (95% CI: 55.81, 65.02). The I2 test result indicated high heterogeneity among included studies (I2 98.8%; p = < 0.001), and because of this high heterogeneity the random effect meta-analysis model was used (Fig. 2). We also conducted a univariate meta-regression by considering the year of publication, sample size, and region in Ethiopia as covariates to identify the possible sources of heterogeneity, and unfortunately, none was found to be statistically significant (Table 2). Additionally, publication bias was assessed subjectively and objectively using both a funnel plot and Begg’s and Egger’s tests respectively. Even if the funnel plot showed the presence of publication bias (Fig. 3), no publication bias was found according to the results of Begg’s and Egger’s tests for the prevalence of EBF (p = 0.304) and (p = 0.314) respectively.

Fig. 2.

Forest plot displaying the pooled prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding of 45 studies in Ethiopia, 2020

Table 2.

heterogeneity of exclusive breastfeeding prevalence in the current meta-analysis (based on univariate meta-regression considering Year of publication, Sample size, and Regions in Ethiopia as a covariate), 2020

| Variables | Coefficient (individual) | p-value (individual) |

|---|---|---|

| Year of publication | 0.0159 | 0.896 |

| Sample size | 0.000229 | 0.323 |

| Regions in Ethiopia | 0.00339 | 0.960 |

Fig. 3.

Funnel plot for publication bias, with PREPOP represented in the x-axis and standard error of SEPOP on the y-axis, 2020

Subgroup analysis

Subgroup analyses were conducted by splitting all primary studies included in the analysis by region (geographical locations) in Ethiopia, the total sample size, and publication year, to make comparisons between them and as a means of investigating heterogeneity. Accordingly, this systematic review and meta-analysis showed that the highest prevalence of EBF was reported in a study conducted in SNNP and Tigray 87.84% (95% CI: 85.19, 90.48), a study published during (2015–2016) 64.60% (95% CI: 52.90, 76.30) and among studies with a sample size with less than 500 participants (64.15% (95% CI: 58.61, 69.68)) respectively (Table 3).

Table 3.

The subgroup analysis for the prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding by region and year of publication and sample size in Ethiopia, 2020 (n = 45)

| Variables | Characteristics | Number of Included study | Prevalence (95% CI) | I2 | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| By region | Addis Ababa | 2 | 36.64 (22.02,51.26) | 95.6% | < 0.001 |

| Affar | 4 | 72.07 (59.61,84.53) | 97.0% | < 0.001 | |

| Amhara | 15 | 58.10 (49.50,66.71) | 99.0% | < 0.001 | |

| Harari | 2 | 43.49 (38.78,48.20) | 56.9% | < 0.001 | |

| Nationwide | 1 | 59.91 (58.36,61.45) | – | – | |

| Oromia | 4 | 65.43 (47.29,83.56) | 99.2% | < 0.001 | |

| SNNP | 12 | 59.31 (52.49,66.14) | 96.8% | < 0.001 | |

| Somalia | 2 | 63.05 (47.14,78.96) | 97.0% | < 0.001 | |

| Tigray | 1 | 70.19 (66.29,74.08) | – | – | |

| Dire Dawa | 1 | 81.11 (78.22,84.00) | – | – | |

| SNNP and Tigray | 1 | 87.84 (85.19,90.48) | – | – | |

| By the year of publication | 2015–2016 | 13 | 64.60 (52.90,76.30) | 99.2% | < 0.001 |

| 2017–2019 | 32 | 58.74 (53.89,63.59) | 98.5% | < 0.001 | |

| By sample size | < 500 | 24 | 64.15 (58.61,69.68) | 97.2% | < 0.001 |

| 500–1000 | 17 | 58.33 (49.99,66.67) | 98.9% | < 0.001 | |

| ≥1000 | 4 | 47.38 (35.86,58.90) | 99.4 | < 0.001 |

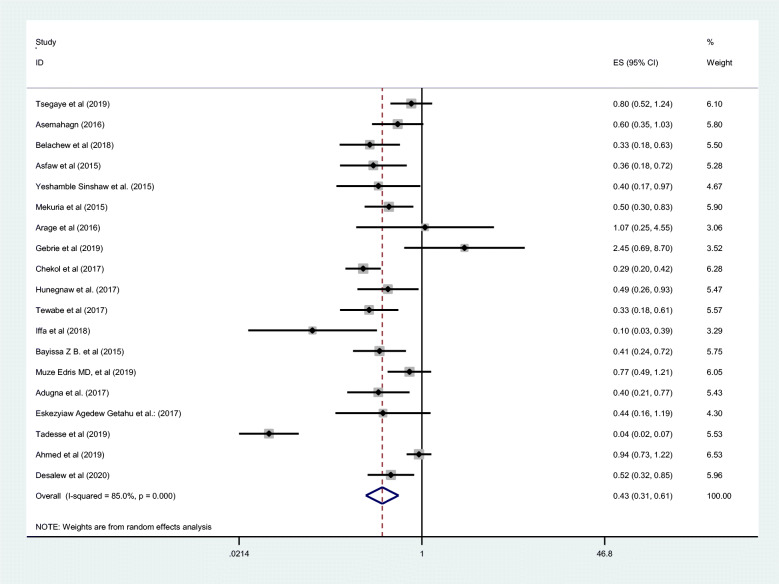

Association between maternal employment and exclusive breastfeeding in Ethiopia

We examined the association between maternal employment and EBF practice using 19 studies [32–50] in this meta-analysis and the findings showed that the practice of EBF was negatively associated with maternal employment (OR 0.43; 95% CI 0.31, 0.61). High heterogeneity (I2 = 85.0% and p-value < 0.000) was observed across the included studies and a random effect meta-analysis model was applied to examine the association between maternal employment and EBF in Ethiopia (Fig. 4). We also assessed publication bias subjectively using the funnel plot and objectively using Begg’s and Egger’s tests. While the funnel plot showed the presence of publication bias, Begg’s and Egger’s tests showed the absence of significant publication bias (p- value = 0.363 and p = 0.684) respectively (Fig. 5).

Fig. 4.

The pooled odds ratio of the association between maternal employment and exclusive breastfeeding in Ethiopia in 2020

Fig. 5.

Funnel plot for publication bias, with LNOREMP represented in the x-axis and standard error of LNOREMP on the y-axis, 2020

Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis research was conducted to determine the pooled prevalence of EBF and its association with maternal employment in Ethiopia using a study published between 1 January 2015 and 31 December 2020. According to the results of 45 studies included in this meta-analysis, the pooled prevalence of EBF in Ethiopia is 60.42% (95% CI: 55.81, 65.02). The overall prevalence of EBF in this study is similar to the result of the 2016 Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey (EDHS) result (58%) [13], and the result of a meta-analysis conducted in Ethiopia (59.3%) [82]. This finding could be attributed to similarities in socio-demographics, methodologies, and the characters of individual studies included in both review and EDHS reports. But, the overall reported prevalence of EBF in this review is higher than the result of meta-analysis result conducted in Iran (49.1%) [83] and 29 Sub-Saharan African (SSA) countries, which showed the prevalence of EBF to be 23.70% in Central Africa and 56.57% in Southern Africa [84]. The pooled prevalence of EBF in this review is also higher than the results of the study conducted in 27 Sub-Saharan African countries (36%) [85], the Demographic and Health Survey of Tanzania (22.9%) [86], Demographic and Health Survey of Madagascar (48.8%) [87] and the study conducted in developing countries (39%) [88]. This variation might be because of methodological differences, differences in infants and maternal socio-demographic characteristics, economics, health service utilization, the gap of the year in which the study was conducted, and the number of studies included in the review. But the overall prevalence of EBF in our review is lower than the result of the primary study conducted in Indian regions, which indicated the prevalence of EBF was 79.2% in southern India and 68.0% in northeastern India respectively [89], the Nepal Demographic and Health Survey result was 66.3% [90], and the result of the study conducted in Ghana, 64% [91].

Based on the subgroup analysis, the highest (87.84%) and lowest (36.64%) prevalence of EBF was reported in a study conducted among rural mothers of SNNP and Tigray region and Addis Ababa City respectively. This regional variation might be because of differences in socio-demographics, and the difference in numbers of the studies included in the two regions during analysis. In addition to the above, the participants of a study conducted in SNNP and Tigray region were rural resident mothers, and according to different kinds of literature being rural in residence for breastfeeding mothers is associated with a high prevalence of EBF practice [66, 77, 92].

We also performed a subgroup analysis using a year of study publication. Accordingly, the highest (64.60%) and lowest (58.74%) prevalence of EBF were reported in studies published during 2015–2016 and 2017–2020 respectively. This difference could be attributed to the difference in coverage of health information regarding EBF and effective utilization of health extension workers, adherence to the national and international policy by health institutions [93]. Besides, we conducted subgroup analysis using the total sample size of the study, and the highest (64.15%) and lowest (47.38%) prevalence of EBF was reported among studies with a sample size less than 500 and greater than or equal to 1000 respectively. This difference might be associated with a difference in the number of primary studies included in each category during analysis (24 primary studies in the category of the sample size of < 500 and four primary studies in the category of the sample size of ≥1000) respectively. One of the greatest threats to the validity of meta-analytic results is publication bias which generally leads to effect sizes being overestimated and the dissemination of false-positive results [94–96] and because of this, we assessed publication bias and possible sources of heterogeneity using Begg’s and Egger’s tests and univariate meta-regression respectively and no publication bias was found.

Full-time maternal employment was negatively associated with the practice of EBF among mothers who returned to work before 6 months in this systematic review and meta-analysis research (OR 0.43; 95% CI 0.31, 0.61). This result is in line with the results of a study conducted in 19 developing countries [97], another study conducted in Iran [98], a study conducted in developing countries [99], and a final study conducted in low and middle-income countries [100]. This similarity could be attributed to mothers who returned to work before 6 months postnatally and who have less frequent contact with their baby and employed mothers who begin liquid and solid based supplementation of food before the recommended age of starting weaning food which will result in the decreased practice of EBF [101]. Some evidence showed that employed mothers face unique barriers to practice EBF and returning to work too early after birth has been shown to affect the practice of EBF. Different kinds of literature showed that the more we increase the legislated duration of paid maternity leave, the more the mothers’ practice EBF and this will result in the higher prevalence of EBF [20, 102, 103].

Limitations of the study

This review has certain limitations. The majority of the primary studies included in the review were cross-sectional studies which might affect the outcome variable because of other confounding factors. Studies published in a language other than English were not included in the review and the review addressed only one associated factor (maternal employment) with EBF. The review included some studies with a small sample size which might affect the pooled report of EBF. The last the last limitation is that the study protocol was not registered at the international prospective register of systematic reviews (PROSPERO).

Conclusions

Full-time maternal employment was negatively associated with the practice of EBF in comparison to unemployed mothers. The prevalence of EBF in Ethiopia is low in comparison to the global recommendation. Based on our review findings, we recommended that the Ethiopian government should increase legislated paid maternity leave after delivery beyond currently paid maternity leave and implement policies that empower women. The governmental and non-governmental organizations should create a conducive environment for employed mothers to practice EBF at the workplace.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1. Quality score of included and excluded studies in this review to estimate the pooled prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding in Ethiopia, 2020.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- AIDS

Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome

- CI

Confidence Interval

- EBF

Exclusive breastfeeding

- EDHS

Ethiopian demographic health survey

- HIV

Human immunodeficiency virus

- HSTP

Health Sector Transformation Plan

- JBI

Joanna Briggs Institute

- JBI-MAStARI

Joanna Briggs Institute Meta-Analysis of Statistics Assessment and Review Instrument

- MMR

Maternal mortality ratio

- NM

Neonatal mortality

- OR

Odds ratio

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- PROSPERO

International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews

- SDG

Sustainable development goal

- SNNP

Southern Nations, Nationalities, and Peoples

- SSA

Sub-Saharan Africa

- UN

United Nations

- UNICEF

United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund

- WHO

World Health Organization

Authors’ contributions

GE: Conception of the research protocol, study design, literature review, data extraction, data analysis, interpretation, and drafting of the manuscript. YM: data extraction, quality assessment, data analysis, and reviewing the manuscript. Both authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Funding

No funding was received from any organization.

Availability of data and materials

Datasets used for this study and other supplementing materials are available from the corresponding author on request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.United Nations . Transforming our world, the 2030 agenda for sustainable development. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization . Infant and young child feeding, model chapter for textbooks for medical students and allied health professionals. 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Black RE, Victora CG, Walker SP, Bhutta ZA, Christian P, De Onis M, et al. Maternal and child undernutrition and overweight in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet. 2013;382(9890):427–451. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60937-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization . World health statistics, Geneva 27, Switzerland. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization . Sixty-fifth World Health Assembly, Geneva. 2012. pp. 21–26. [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization . Global nutrition targets 2015, policy brief series. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization/ United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund . Breastfeeding Advocacy Initiative For the best start in life. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 8.United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund . Breastfeeding on the world agenda. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization . Essential nutrition action: improving maternal, newborn, infant, and young child health and nutrition, Geneva 27, Switzerland. 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund. Improving Exclusive Breastfeeding Practices by using Communication for Development in Infant and Young Child Feeding Programmes. 2011-2012. Available from:https://resourcecentre.savethechildren.net/node/12984/pdf/3.2._communication_manual_for_improving_breastfeeding_practices_unicef_2010.pdf

- 11.Agho KE, Ezeh OK, Ghimire PR, Uchechukwu OL, Stevens GJ, Tannous W, Fleming C, Ogbo F, Global Maternal and Child Health Research collaboration (GloMACH) Exclusive breastfeeding rates and associated factors in 13 “Economic Community of West African States” (ECOWAS) countries. Nutrients. 2019;11(12):3007. doi: 10.3390/nu11123007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ayuk TB, Bassogog CB, Nyobe C. The determinants of exclusive breastfeeding in Cameroon, Sub-Saharan Africa. Trends Gen Pract. 2018;1(3):1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey. 2016. Available from: https://dhsprogram.com/publications/publication-fr328-dhs-final-reports.cfm

- 14.Walters DD, Phan LTH, Mathisen R. The cost of not breastfeeding, global results from a new tool. Health Policy Plan. 2019;34(6):407–417. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czz050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Betrán AP, De Onís M, Lauer JA, Villar J. Ecological study of effect of breastfeeding on infant mortality in Latin America. BMJ. 2001;323(7308):303–306. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7308.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arifeen S, Black RE, Antelman G, Baqui A, Caulfield L, Becker S, et al. Exclusive breastfeeding reduces acute respiratory infection and diarrhea deaths among infants in Dhaka slums. Pediatrics. 2001;108(4):e67. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.4.e67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lauer JA, Betra AP. Deaths and years of life lost due to suboptimal breastfeeding among children in the developing world: a global ecological risk assessment. Public Health Nutr. 2006;9(6):673–685. doi: 10.1079/PHN2005891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Edmond KM, Zandoh C, Quigley MA, Amenga-Etego S, Owusu-Agyei Delayed breastfeeding initiation increases risk of neonatal mortality. Pediatrics. 2006;117(3):e380. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.The Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, Ministry of Health. National newborn and child survival strategy document brief summary 2015/16–2019/20. https://www.unicef.org/ethiopia/media/391/file/Child%20Survival%20Strategy%20in%20Ethiopia%20.pdf. Accessed 19 May 2020.

- 20.Chai Y, Nandi A, Heymann J. Does extending the duration of legislated paid maternity leave to improve breastfeeding practices ? Evidence from 38 low-income and middle-income countries. BMJ Glob Health. 2018;3(5):e001032. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-001032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mirkovic KR, Perrine CG, Scanlon KS. Paid maternity leave and breastfeeding outcomes. Birth. 2016;43(3):233–239. doi: 10.1111/birt.12230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund. Let’s make it work !, Breastfeeding in the workplace. 2018. Available from: https://www.healthynewbornnetwork.org/hnncontent/uploads/Mother_BabyFriendlyWorkplaceInitiativeC4D_web1_002_.pdf

- 23.Wanjohi M, Griffiths P, Wekesah F, Muriuki P, Muhia N, Musoke RN, Fouts HN, Madise NJ, Kimani-Murage EW. Sociocultural factors influencing breastfeeding practices in two slums in Nairobi, Kenya. Int Breastfeed J. 2017;12(1):5. doi: 10.1186/s13006-016-0092-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Osman H, El Zein L, Wick L. Cultural beliefs that may discourage breastfeeding among Lebanese women, a qualitative analysis. Int Breastfeed J. 2009;4(1):12. doi: 10.1186/1746-4358-4-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Swigart TM, Bonvecchio A, Théodore FL, Zamudio-Haas S, Villanueva-Borbolla MA, Thrasher JF. Breastfeeding practices, beliefs, and social norms in low-resource communities in Mexico: insights for how to improve future promotion strategies. PLoS One. 2017;12(7):e0180185. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0180185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.World Health Organization and United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund . Global nutrition targets 2025, Breastfeeding policy brief. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 27.World Health Organization and United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund . Global breastfeeding scorecard, enabling women to breastfeed through better policies and programs. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 28.United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund . Expanding Viet Nam’s maternity leave policy to six months : an investment today in a stronger, healthier tomorrow. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ministry of Law and Justice . The maternity benefit (amendment), an act further to amend the Maternity Benefit, new delhi. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 30.International Cooperation Department, Ministry of Labour, Invalids, and Social Affairs of Vietnam. 2012;https://www.ilo.org/dyn/natlex/docs/MONOGRAPH/91650/114939/F224084256/VNM91650.pdf. Accessed 17 May 2020.

- 31.Ahmad I. Ethiopian Decent Work Check 2021. Available from:http://www.wageindicator.org/documents/decentworkcheck/africa/ethiopia-english.pdf

- 32.Tsegaye M, Ajema D, Shiferaw S, Yirgu R. Level of exclusive breastfeeding practice in remote and pastoralist community, Aysaita. Int Breastfeed J. 2019;14(1):6. doi: 10.1186/s13006-019-0200-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Asemahagn MA. Determinants of exclusive breastfeeding practices among mothers in azezo district, Northwest Ethiopia. Int Breastfeed J. 2016;11(1):22. doi: 10.1186/s13006-016-0081-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Belachew A, Tewabe T, Asmare A, Hirpo D, Zeleke B, Muche D. Prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding practice and associated factors among mothers having infants less than 6 months old, in Bahir Dar, northwest, Ethiopia. BMC Res Notes. 2018;11(1):768. doi: 10.1186/s13104-018-3877-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Asfaw MM, Argaw MD, Kefene ZK. Factors associated with exclusive breastfeeding practices in Debre Berhan district, Central Ethiopia. Int Breastfeed J. 2015;10(1):23. doi: 10.1186/s13006-015-0049-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sinshaw Y, Ketema K, Tesfa M. Exclusive breastfeeding practice and associated factors among mothers in Debre Markos town and Gozamen district, east Gojjam zone. J Food Nutr Sci. 2015;3(5):174–179. doi: 10.11648/j.jfns.20150305.12. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mekuria G, Edris M. Exclusive breastfeeding and associated factors among mothers in Debre Markos, Northwest Ethiopia. Int Breastfeed J. 2015;10(1):1. doi: 10.1186/s13006-014-0027-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Arage G, Gedamu H. Exclusive breastfeeding practice and its associated factors among mothers of infants less than six months of age in Debre Tabor town, Northwest Ethiopia. Adv Public Health. 2016;3426249:1–7. doi: 10.1155/2016/3426249. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gebrie YF, Dessie TM, Jemberie NF. Logistic regression analysis of exclusive breastfeeding practice among mothers in Amanuel town, northwest, Ethiopia. Am J Data Mining Knowledge Discovery. 2018;3(2):13–19. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chekol DA, Biks GA, Gelaw YA, Melsew YA. Exclusive breastfeeding and mothers’ employment status in Gondar town, Northwest Ethiopia. Int Breastfeed J. 2017;12(1):27. doi: 10.1186/s13006-017-0118-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hunegnaw MT, Gezie LD, Teferra AS. Exclusive breastfeeding and associated factors among mothers in Gozamin district, Northwest Ethiopia. Int Breastfeed J. 2017;12(1):30. doi: 10.1186/s13006-017-0121-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tewabe T, Mandesh A, Gualu T, Alem G, Mekuria G, Zeleke H. Exclusive breastfeeding practice and associated factors among mothers in Motta town, east Gojjam zone, Amhara regional state, Ethiopia. Int Breastfeed J. 2017;12(1):12. doi: 10.1186/s13006-017-0103-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Iffa MT, Serbesa ML. Assessment of the influence of mother’s occupation and education on breastfeeding and weaning practice of children in public hospital, Harari regional state Ethiopia. Fam Med Medical Sci Res. 2018;7(03):3. doi: 10.4172/2327-4972.1000234. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bayissa ZB, Gelaw BK, Geletaw A, Abdella A, Yosef A, Tadele K. Knowledge and practice of mothers towards exclusive breastfeeding and its associated factors in ambo woreda west shoa zone, Oromia region, Ethiopia. Int J Res Dev Pharm Life Sci. 2015;4(3):1590–1597. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Edris MM, Atnafu NT, Abota TL. Magnitude and determinants of exclusive breastfeeding among children age less than 23 months in bench Maji zone, Southwest Ethiopia. Int J Pediatr Child Care. 2019;2(1):1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Adugna B, Tadele H, Reta F, Berhan Y. Determinants of exclusive breastfeeding in infants less than six months of age in Hawassa, an urban setting, Ethiopia. Int Breastfeed J. 2017;12(1):45. doi: 10.1186/s13006-017-0137-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Getahun EA, Hayelom DH, Kassie GG. Exclusive breastfeeding practice and associated factors in Kemba woreda, southern Ethiopia. Int J Sci Technol Soc. 2017;5(4):55–61. doi: 10.11648/j.ijsts.20170504.11. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tadesse F, Alemayehu Y, Shine S, Asresahegn H, Tadesse T. Exclusive breastfeeding and maternal employment among mothers of infants from three to five months old in the Fafan zone, Somali regional state of Ethiopia. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):1015. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-7345-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ahmed KY, Page A, Arora A, Ogbo FA. Trends and determinants of early initiation of breastfeeding and exclusive breastfeeding in Ethiopia. Int Breastfeed J. 2019;14(1):40. doi: 10.1186/s13006-019-0234-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Desalew A, Sema A, Belay Y. Exclusive breastfeeding practice and its associated factors among mothers with children aged 6-23 months in Dire Dawa, eastern Ethiopia. J Midwifery Reprod Health. 2020;8(4):2419–2428. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JPA, Clarke M, Devereaux PJ, Kleijnen J, Moher D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000100. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Munn Z, Tufanaru C, Aromataris E. Data extraction and synthesis. Am J Nurs. 2014;114(7):49–54. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000451683.66447.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Moola S, Munn Z, Tufanaru C, Aromataris E, Sears K, Sfetcu R, et al. Checklist for analytical cross-sectional studies. Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer’s Manual. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rücker G, Schwarzer G, Carpenter JR, Schumacher M. Undue reliance on I2 in assessing heterogeneity may mislead. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8(1):79. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-8-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, Rothstein HR. A basic introduction to fixed-effect and random-effects models for meta-analysis. Res Synth Methods. 2010;1(2):97–111. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Liben ML, Gemechu YB, Adugnew M, Asrade A, Adamie B, Gebremedin E, Melak Y. Factors associated with exclusive breastfeeding practices among mothers in dubti town, Afar regional state, Northeast Ethiopia. Int Breastfeed J. 2016;11(1):4. doi: 10.1186/s13006-016-0064-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gizaw Z, Woldu W, Bitew BD. Exclusive breastfeeding status of children aged between 6 and 24 months in the nomadic population of Hadaleala district, Afar region, Northeast Ethiopia. Int Breastfeed J. 2017;12(1):38. doi: 10.1186/s13006-017-0129-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Biks GA, Tariku A, Tessema GA. Effects of antenatal care and institutional delivery on exclusive breastfeeding practice in Northwest Ethiopia. Int Breastfeed J. 2015;10(1):30. doi: 10.1186/s13006-015-0055-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tariku A, Alemu K, Gizaw Z, Muchie KF, Derso T, Abebe SM, Yitayal M, Fekadu A, Ayele TA, Alemayehu GA, Tsegaye AT, Shimeka A, Biks GA. Mothers’ education and antenatal care visit improved exclusive breastfeeding in Dabat health and demographic surveillance system site. PLoS One. 2017;12(6):e0179056. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0179056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kitesa B. Assessment of exclusive breastfeeding and associated factors among antenatal care and non-antenatal care mothers in Ethiopian great rift valley. J Human Anatomy. 2017;1(3):000113. doi: 10.23880/JHUA-16000113. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sasie SD, Oljira L, Demena M. Infant and young child feeding practice and associated factors among mothers/caretakers of children aged 0-23 months in Asella town, south East Ethiopia. J Fam Med. 2017;4(5):1122. doi: 10.26420/jfammed.2017.1122. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Anjullo B, Haile J. Factors associated with exclusive breastfeeding practices at Arba Minch town, South Ethiopia. Adv Res. 2018;17(5):1–14. doi: 10.9734/AIR/2018/46020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Azeze GA, Gelaw KA, Gebeyehu NA, Gesese MM, Mokonnon TM. Exclusive breastfeeding practice and associated factors among mothers in Boditi town, southern Ethiopia. Int J Pediatr. 2019. 10.1155/2019/1483024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 64.Sorato MM. Levels and predictors of exclusive breastfeeding among rural mothers with children age 0-12 months in rural kebeles of Chencha district, Snnpr, Gamo Gofa zone, Ethiopia. Int J Pediatr Neonatal Health. 2017;1(3):77–90. doi: 10.25141/2572-4355-2017-3.0077. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Surender R, Teshome A. Determinants of exclusive breastfeeding practice among mothers of children under two years old in Dilla Zuria district, Gedeo zone, Snnpr, Ethiopia. J Pregnancy Child Health. 2016;3:1. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bisrat Z. Factors associated with early initiation and exclusive breastfeeding practices among mothers of infants age less than 6 months. J Pediatr Neonatal Care. 2017;7(3):00292. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sonko A, Worku A. Prevalence and predictors of exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months of life among women in Halaba special woreda, southern nations, nationalities and Peoples’ region, Ethiopia. Arch Public Health. 2015;73(1):53. doi: 10.1186/s13690-015-0098-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Alemu E, Wondoson A, Nebiyu D. Prevalence and determinants of exclusive breastfeeding practices among infants in Hossana town, southern Ethiopia. EC Gynaecol. 2017;4(3):69–79. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lenja A, Demissie T, Yohannes B, Yohannis M. Determinants of exclusive breastfeeding practice to infants aged less than six months in Offa district, southern Ethiopia. Int Breastfeed J. 2016;11(1):32. doi: 10.1186/s13006-016-0091-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kelaye T. Assessment of prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding practice and associated factors among under six-month-old children selected woreda south nation nationality of people regional state, Ethiopia. J Nutritional Health Food Sci. 2017;5(6):1–7. doi: 10.15226/jnhfs.2017.001111. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Teka B, Assefa H, Haileslassie K. Prevalence and determinant factors of exclusive breastfeeding practices among mothers in Enderta woreda, Tigray, North Ethiopia. Int Breastfeed J. 2015;10(1):2. doi: 10.1186/s13006-014-0028-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Shifraw T, Worku A, Berhane Y. Factors associated exclusive breastfeeding practices of urban women in Addis Ababa public health centers, Ethiopia. Int Breastfeed J. 2015;10(1):22. doi: 10.1186/s13006-015-0047-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Elyas L, Mekasha A, Admasie A, Assefa E. Exclusive breastfeeding practice and associated factors among mothers attending private pediatric and child clinics, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Int J Pediatrics. 2017. 10.1155/2017/8546192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 74.Nur A, Kahssay M, Woldu E, Seid O. Factors associated with exclusive breastfeeding among mothers of infants less than 6 months of age in dubti district, Afar region, Ethiopia. J Public Health Catalog. 2018;1(4):120–126. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ayalew T. Exclusive breastfeeding practice and associated factors among first-time mothers in Bahir Dar city, Northwest Ethiopia. Heliyon. 2020;6(9):e04732. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e04732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Alebachew F, Natnael G, Tessema NT. The prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding and associated factors among mothers of less than two years children in Kurkur kebele, Dessie town. J Gynecol Obstetr. 2016;4(6):72–80. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bazie E, Birara A. G/Hanna E. exclusive breastfeeding prevalence and associated factors an institutional-based cross-sectional study in Bahir Dar Northwest Ethiopia. Int J Homeopathy Nat Med. 2019;5(1):42–49. doi: 10.11648/j.ijhnm.20190501.17. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mulatu Dibisa T, Sintayehu Y. Exclusive breastfeeding and its associated factors among mothers of <12 months old child in Harar town, eastern Ethiopia. Pediatric Health Med Therapeutics. 2020;11:145–152. doi: 10.2147/PHMT.S253974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Obsiye M. Determinants of exclusive breastfeeding practices among mothers of infants aged under six months in Jigjiga town, eastern Ethiopia. Int J Sci Basic Appl Res. 2019;46(2):62–74. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Mamo K, Dengia T, Abubeker A, Girmaye E. Assessment of exclusive breastfeeding practice and associated factors among mothers in west Shoa zone, Oromia, Ethiopia. Obstetr Gynecol Int. 2020. 10.1155/2020/3965873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 81.Hagos D, Tadesse AW. Prevalence and factors associated with exclusive breastfeeding among rural mothers of infants less than six months of age in southern nations, nationalities, peoples, and Tigray regions, Ethiopia. Int Breastfeed J. 2020;15(1):25. doi: 10.1186/s13006-020-00267-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Alebel A, Tesma C, Temesgen B, Ferede A, Kibret GD. Exclusive breastfeeding practice in Ethiopia and its association with antenatal care and institutional delivery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Breastfeed J. 2018;13(1):31. doi: 10.1186/s13006-018-0173-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ranjbaran M, Nakhaei MR, Chizary M, Shamsi M. Prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding in Iran : systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Epidemiol Res. 2016;3(3):294–301. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Issaka AI, Agho KE. Prevalence of key breastfeeding indicators in 29 sub-Saharan African countries : a meta-analysis of demographic and health surveys (2010 -2015) BMJ Open. 2017;7(10):e014145. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Berde AS, Yalc S. Determinants of exclusive breastfeeding in sub-saharan Africa: a multilevel approach. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2016;30(5):439–449. doi: 10.1111/ppe.12305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Victor R, Baines SK, Agho KE, Dibley MJ. Determinants of breastfeeding indicators among children less than 24 months of age in Tanzania: a secondary analysis of the 2010 Tanzania demographic and health survey. BMJ Open. 2013;3(1):e001529. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Rakotomanana H, Gates GE, Hildebrand D, Stoecker BJ. Situation and determinants of the infant and young child feeding (IYCF) indicators in Madagascar : analysis of the 2009 demographic and health survey. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):812. doi: 10.1186/s12889-017-4835-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lauer JA, Betrán AP, Victora CG, De OM, Barros AJD. Breastfeeding patterns and exposure to suboptimal breastfeeding among children in developing countries: review and analysis of nationally representative surveys. BMC Med. 2004;2(1):26. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-2-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ogbo FA, Dhami MV, Awosemo AO, Olusanya BO, Olusanya J, Osuagwu UL, Ghimire PR, Page A, Agho KE. Regional prevalence and determinants of exclusive breastfeeding in India. Int Breastfeed J. 2019;14(1):20. doi: 10.1186/s13006-019-0214-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Khanal V, Sauer K, Zhao Y. Exclusive breastfeeding practices in relation to social and health determinants : a comparison of the 2006 and 2011 Nepal demographic and health surveys. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):958. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Tampah-Naah AM, Kumi-Kyereme A. Determinants of exclusive breastfeeding among mothers in Ghana. Int Breastfeed J. 2013;8(1):13. doi: 10.1186/1746-4358-8-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Habtewold TD, Mohammed SH, Endalamaw A, Akibu M, Sharew NT, Alemu YM, Beyene MG, Sisay TA, Birhanu MM, Islam MA, Tegegne BS. Breast and complementary feeding in Ethiopia: new national evidence from systematic review and meta-analyses of studies in the past 10 years. Eur J Nutr. 2019;58(7):2565–2595. doi: 10.1007/s00394-018-1817-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.The Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, Ministry of Health . Health sector transformation plan (HSTP) 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Rothstein HR, Sutton AJ, Borenstein M. Publication bias in meta-analysis: prevention, assessment, and adjustments. Appl Psychol Meas. 2009;33(1):74–76. doi: 10.1177/0146621608327804. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Lane DM, Dunlap WP. Estimating effect size: bias resulting from the significance criterion in editorial decisions. Br J Math Stat Psychol. 1978;31(2):107–112. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8317.1978.tb00578.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Nuijten MB, Van Assen MALM, Veldkamp CLS, Wicherts JM. The replication paradox: combining studies can decrease the accuracy of effect size estimates. Rev Gen Psychol. 2015;19(2):172–182. doi: 10.1037/gpr0000034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Balogun OO, Dagvadorj A, Anigo KM, Ota E, Sasaki S. Factors influencing breastfeeding exclusivity during the first 6 months of life in developing countries: a quantitative and qualitative systematic review. Maternal Child Nutr. 2015;11(4):433–451. doi: 10.1111/mcn.12180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Saffari M, Pakpour AH, Chen H. Factors influencing exclusive breastfeeding among Iranian mothers:a longitudinal population-based study. Health Promotion Perspect. 2017;7(1):34–41. doi: 10.15171/hpp.2017.07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Rahman N, Kabir R, Sultana M, Islam M, Alam MR, Dey M, et al. Exclusive breastfeeding practice, survival function and factors associated with the early cessation of exclusive breastfeeding in developing countries. Asian J Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;3(1):38–49. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Oddo VM, Ickes SB. Maternal employment in low- and middle-income countries is associated with improved infant and young child feeding. Am J Clin Nutr. 2018;107(3):335–344. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/nqy001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Xiang N, Zadoroznyj M, Tomaszewski W, Martin B. Timing of return to work and breastfeeding in Australia. Pediatrics. 2016;137(6):e20153883. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-3883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Navarro-Rosenblatt D, Garmendia ML. Maternity leave and its impact on breastfeeding: a review of the literature. Breastfeed Med. 2018;13(9):589–597. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2018.0132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Steurer LM. Maternity leave length and workplace policies’ impact on the sustainment of breastfeeding: global perspectives. Public Health Nurs. 2017;34(3):286–294. doi: 10.1111/phn.12321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1. Quality score of included and excluded studies in this review to estimate the pooled prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding in Ethiopia, 2020.

Data Availability Statement

Datasets used for this study and other supplementing materials are available from the corresponding author on request.