Abstract

Background

Several Rhodobacter sphaeroides have been widely applied in commercial CoQ10 production, but they have poor glucose use. Strategies for enhancing glucose use have been widely exploited in R. sphaeroides. Nevertheless, little research has focused on the role of glucose transmembrane in the improvement of production.

Results

There are two potential glucose transmembrane pathways in R. sphaeroides ATCC 17023: the fructose specific-phosphotransferase system (PTSFru, fruAB) and non-PTS that relied on glucokinase (glk). fruAB mutation revealed two effects on bacterial growth: inhibition at the early cultivation phase (12–24 h) and promotion since 36 h. Glucose metabolism showed a corresponding change in characteristic vs. the growth. For ΔfruAΔfruB, maximum biomass (Biomax) was increased by 44.39% and the CoQ10 content was 27.08% more than that of the WT. glk mutation caused a significant decrease in growth and glucose metabolism. Over-expressing a galactose:H+ symporter (galP) in the ΔfruAΔfruB relieved the inhibition and enhanced the growth further. Finally, a mutant with rapid growth and high CoQ10 titer was constructed (ΔfruAΔfruB/tac::galPOP) using several glucose metabolism modifications and was verified by fermentation in 1 L fermenters.

Conclusions

The PTSFru mutation revealed two effects on bacterial growth: inhibition at the early cultivation phase and promotion later. Additionally, biomass yield to glucose (Yb/glc) and CoQ10 synthesis can be promoted using fruAB mutation, and glk plays a key role in glucose metabolism. Strengthening glucose transmembrane via non-PTS improves the productivity of CoQ10 fermentation.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12934-021-01695-z.

Keywords: R. sphaeroides, Glucose transmembrane, Glucose metabolism, CoQ10 productivity

Introduction

Glucose is a common monosaccharide that is available in abundance. As glucose is cheap and easy to use for microorganisms, it can serve as an ideal source of carbon for producing high-value products, such as CoQ10, through microbial fermentation [1–3]. Studies related to microbial glucose metabolism have always been a hot topic in industrial microbiology [1, 4]. As glucose metabolism pathways have been well established for many microorganisms, many novel biotechnologies, particularly metabolic engineering, synthetic biology, and systems biology, have been applied to modify intracellular metabolic pathways to enhance the glucose utilization efficiency in microorganisms [1, 4, 5]. Besides the functional enzymes for glucose metabolism, glucose utilization also requires a set of genes that encode specific transporters and regulators [5]. Glucose transmembrane is an important step because exogenous glucose cannot go into cells through free diffusion and must rely on a transporter to cross the cell membrane [6]. Recently, researchers have realized the importance of glucose transport efficiency during microbial fermentation and focus on microbial sugar transmembrane studies [6–8]. So far, the sugar transmembrane mechanisms of many industrial microbes are still unknown, limiting metabolic modification of sugar transmembrane in these microbes.

Microorganisms depend on more than one system to transport exogenous glucose; the glucose transmembrane mechanisms for E. coli have been widely investigated [6, 7]. E. coli can use two pathways for glucose transmembrane: phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP): carbohydrate phosphotransferase system (PTS) and non-PTS [6]. The non-PTS include the ATP binding cassette (ABC) system and the major facilitator superfamily (MFS) system. PTSGlc is a multiprotein phosphorelay system that accompanies the import and simultaneous phosphorylation of carbohydrates. Since the discovery of the PTSGlc in E. coli, it has existed in many other bacteria [9]. It has been confirmed that the PTSGlc is primarily composed of enzymes including IICBGlc/IIAGlc(EIIs), HPr, and enzyme I (EI). EI and HPr, the two sugar-nonspecific protein constituents of the PTS, are soluble cytoplasmic proteins participating in the transport of all PTS carbohydrates [6]. EIIs are sugar-specific transporters connecting the common PEP/EI/HPr phosphoryl transfer pathway. PTSGlc is considered an effective way to use glucose because only one phosphoenolpyruvate is coupled with the translocation phosphorylation of glucose when forming an ATP. In contrast, use of glucose through the ABC transporter requires extra ATP for glucose phosphorylation in the carbohydrate kinase reaction [6, 10]. Therefore, PTSGlc is a preferred channel for transferring exogenous glucose into cells in industrial bacteria, such as E. coli, Bacillus subtilis, and Corynebacterium glutamicum [4, 11, 12]. E. coli activates the non-PTS system for glucose transmembrane when exogenous glucose concentration is low (< 1 mM), or PTSGlc function is defective [7]. Some bacteria lacking PTSGlc, such as Pseudomonas putida, utilize the ABC system to transfer exogenous glucose into cells [9].

R. sphaeroides has received significant attention because of its wide biotechnological applications, such as its ability to synthesize a high content of CoQ10, carotenoids, and isoprenoids as a source of pharmaceutical materials [13–16]. CoQ10 is an oil-soluble quinone that has a decaprenyl side chain. So far, it has been widely used in functional food and cosmetics industries because of its antioxidant function. Researchers have recently found that CoQ10 can regulate several genes that play an important role in cholesterol metabolism, inflammatory responses, or both [14]. Moreover, it is beneficial to patients with cardiovascular diseases, hypertension, and Parkinson’s disease [17]. Compared with the methods of animal and plant extraction and chemosynthesis, the production of CoQ10 by microbial fermentation is low-cost, safe, and efficient [16]. Additionally, R. sphaeroides, a CoQ10 producer with high contents of CoQ10, has been widely used in the industrial production of CoQ10. For the commercial production of CoQ10 with microbial fermentation, glucose acts as a major carbon source. Various strategies for guiding the metabolic flux toward CoQ10 biosynthesis have been exploited for R. sphaeroides [16]. Nevertheless, presently, there is little research on improving CoQ10 production by modifying the glucose transmembrane. Although R. sphaeroides has a wide spectrum of carbon source utilization, it had a low glucose consumption rate than E. coli [18, 19]. Fuhrer et al. reported that the glucose uptake rate of R. sphaeroides was 1.8 ± 0.1 mmol/g dry cells weight (DCW)/h, which was only approximately 23.07% as that of E. coil [19]. Therefore, the glucose transmembrane process of R. sphaeroides was a bottle-neck step for glucose metabolism, which may be a new way to further promote the productivity of CoQ10.

Considering the importance of glucose transmembrane for glucose metabolism and poor glucose utilization efficiency of R. sphaeroides, the first potential pathway of glucose transmembrane of R. sphaeroides were analyzed in this work. Later, a deep study was conducted to show the function of these pathways on glucose metabolism. Finally, we evaluated the influence of glucose transmembrane on CoQ10 synthesis efficiency and optimized CoQ10 fermentation by R. sphaeroides by modifying glucose transmembrane. Moreover, R. sphaeroides ATCC 17023 is a paradigmatic organism among isolated R. sphaeroides strains with clear genetic background and mature genetic manipulation tools that we chose as a research object in this study [20].

Material and methods

Strains, media and growth conditions

All the strains used in this study were summarized in Table 1. R. sphaeroides ATCC 17023 (wild type, WT) was used as the parental strain in this work. The mutant strains were constructed in this background. E. coli JM109 was used as a plasmid host, and E. coli S17-1 was used to conjugate DNA into R. sphaeroides. R. sphaeroides ATCC 17023 and mutant strains were routinely cultivated at 32℃ in medium A (3 g/L glucose, 2 g/L NaCl, 8 g/L yeast extract, 0.256 g/L MgSO4·7H2O,1.3 g/L KH2PO4, 15 μg/L biotin, 1 mg/L thiamine hydrochloride, 1 mg/L nicotinic acid, pH 7.2) as seed (exponentially phase cells, OD600 ≥ 2). R. sphaeroides cultures were incubated at 32℃ in modified Sistrom’s minimal medium (MSMM) lacking succinate and with glucose as an alternative carbon source (6.5 g/L) [18]. Before inoculation the seeds of these strains were washed with sterilized PBS (pH 7.2), and then resuspended with the same solution to adjust the cell density equal (OD600 1). Antibiotics were added into the medium A and MSMM when necessary. E. coli JM109 and E. coli S17-1 were grown at 37 °C in Luria–Bertani (LB) medium with antibiotics when necessary. The concentrations of antibiotics and chemicals used in the construction of plasmids and recombinant strains were as follows: 25 μg/mL kanamycin and 150 μg/mL K2TeO3 for R. sphaeroides, and 100 μg/mL kanamycin for E. coli strains. Lab-scale fermentation of CoQ10 was carried out with medium B containing 40 g/L glucose, 6.3 g/L MgSO4, 4 g/L corn steep liquor, 3 g/L sodium glutamate, 3 g/L (NH4)2SO4, 3 g/L KH2PO4, 2 g/L CaCO3, 1 mg/L nicotinic acid, 1 mg/L thiamine hydrochloride, and 15 μg/L biotin, supplemented with 25 μg/mL kanamycin.

Table 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this work

| Strains and plasmids | Description | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| Wild-type | Rhodobacter sphaeroides ATCC 17025 | Lab preservation |

| Δglk | glk markerless deletion mutant | This work |

| ΔfruAΔfruB | fruAB markerless deletion mutant | This work |

| ΔfruAΔfruB/bp | ΔfruAΔfruB harboring pBBR1MCS-2 | This work |

| ΔfruAΔfruB/galPOP | ΔfruAΔfruB harboring pBBR1MCS-2:: galP | This work |

| ΔfruAΔfruB/tac::galPOP | ΔfruAΔfruB harboring pBBR1MCS-2:: tac::galP | This work |

| ΔfruAΔfruB/tac::glkOP | ΔfruAΔfruB harboring pBBR1MCS-2:: tac::glk | This work |

| E. coli S17-1 | recA, harboring the genes tra, proA, thi-1(pRP4-2-Tc::Mu-Km::Tn7) | Lab preservation |

| Plasmids | ||

| pK18mobsacB | suicide vector, sacB (sucrose sensitivity), Kmr | Lab preservation |

| pBBR1MCS-2 | ori pBBR1, lacZa, Kmr, used for geng over-expression | Lab preservation |

| pBBR1MCS-2::tac | pBBR1MCS-2 harboring the tac promoter | Lab preservation |

| pK18mobsacB::glk-L-R | For glk deletion | This work |

| pK18mobsacB::fruA-L-R | For fruA deletion | This work |

| pK18mobsacB::fruB-L-R | For fruB deletion | This work |

| pBBR1MCS-2::galP | For galP expression | This work |

| pBBR1MCS-2::tac::galP | For galP expression with strong promoter tac | This work |

| pBBR1MCS-2::tac::glk | For glk expression with strong promoter tac | This work |

Plasmids construction

Plasmids used in this study were listed in Table 1, and the related primers and restriction enzymes were presented in Additional file 6: Table S1. pK18mobsacB::glk-L-R was constructed with splicing by overlap extension (SOE) PCR. Briefly, an upstream and downstream fragment of glk was amplified with primer pair glk-L-F/glk-L-R and glk-R-F/glk-R-R using R. sphaeroides ATCC 17025 genomic DNA as template, respectively. The two fragments were joined by SOE PCR to generate a 1,560-bp fragment, which was digested and ligated into the PstI/SphI sites of pK18mobsacB to obtain pK18mobsacB::glk-L-R. The details of experiment were presented in Additional file 1: Fig. S1. An upstream and downstream fragment of fruA was amplified with primer pair fruA-L-F/fruA-L-R and fruA-R-F/fruA -R-R. The two fragments were joined by SOE PCR to generate a 1,819-bp fragment, which was digested and ligated into the SalI/EcoRI sites of pK18mobsacB to obtain pK18mobsacB::furA-L-R. The construction of pK18mobsacB::fruB-L-R obeyed to the same procedure of pK18mobsacB::furA-L-R construction. The two fragments were amplified with primer pair fruB-L-F/fruB-L-R and fruB-R-F/fruA-R-R, and then were joined by SOE PCR to generate a 1399-bp fragment. Afterwards, the fragment was ligated into the EcoRI/SphI sites of pK18mobsacB to obtain pK18mobsacB::furB-L-R. The details of the two plasmids construction were shown in Additional file 2: Fig. S2. The wide host-range conjugative plasmids pBBR1MCS-2 and pBBR1MCS-2::tac were used to construct the over-expression vectors. For the construction of pBBR1MCS-2::tac::galP, the entire open reading frame of galP gene was amplified by PCR with primer pair galPop-F/galPop-R using E. coil K-12 substr. MG1655 genomic DNA as template. After digestion with XbaI/SacI, it was ligated into pBBR1MCS-2::tac to obtain pBBR1MCS-2::tac::galP. The details of pBBR1MCS-2::tac::galP construction were presented in Additional file 3: Fig. S3. Simultaneously, pBBR1MCS-2::galP was obtained following the same method of pBBR1MCS-2::tac::galP construction.

Strains construction

Δglk and ΔfruAΔfruB were constructed as in-frame markerless deletion of almost the entire open reading frames by a two-step recombination strategy, which was based on diparental conjugation as previously described [14]. In short, E. coli S-17 bearing the target plasmid was used as the donor strain, and R. sphaeroides ATCC 17023 was used as the recipient strain. The donor/recipient ratio was 1:7 for conjugation and the colonies resistant to 150 μg/mL K2TeO3 and 25 μg/mL kanamycin were picked and cultivated for plasmid extraction and sequencing verification. For the construction of Δglk, the pK18mobsacB::glk-L-R was transformed into R. sphaeroides ATCC 17023 by diparental conjugation. Clones obtained from single homologous recombination event were selected on kanamycin/K2TeO3 supplemented medium A agar plates, and then grown for 48–72 h in medium without antibiotic, followed by serial dilution and plating onto SMM plates containing 10% (w/w) sucrose to select for a second crossover event. Finally, sucrose-resistant and kanamycin-sensitive colonies were selected as potential positive transformants and verified by PCR using glk-P1/glk-P4 primers. To obtain the mutant ΔfruAΔfruB, ΔfruA was firstly constructed, and then the gene fruB was knocked out of the genome of ΔfruA further. The method was similar to that of the construction of Δglk. The ΔfruAΔfruB was verified by primer pair fruA-P1/fruA-P4 and fruB-P1/fruB-P4. For the construction of ΔfruAΔfruB/tac::galPOP, pBBR1MCS-2::tac::galP was transformed into ΔfruAΔfruB by diparental conjugation, and selected on medium A supplemented with kanamycin (25 μg/mL) and K2TeO3 (150 μg/mL). Afterwards, the resistant clones were selected and verified. Also, other gene over-expression mutants were constructed following the same method. Primers used for mutant strains verification were listed in Additional file 7: Table S2.

RNA extraction and RT-qPCR assay

Different growth-phase cells (1 × 107) cultured in MSMM medium were harvested by centrifugation at 8000×g for 3 min at 4 ℃. Total RNA was extracted from R. sphaeroides using a Total RNA Extraction Kit and purified as described by the procedures. Synthesis of cDNA was performed by the reverse transcription reaction according to the HiFiScript cDNA Synthesis Kit instructions. Cham Q Universal SYBR qPCR master mix (Vazyme, Nanjing, China; Q711-02) and the ABI First Step Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction System (Applied Biosystems, San Mateo, CA, USA) were used to perform quantitative polymerase chain reactions under the following reaction conditions: 95 °C for 3 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 10 s, 56 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 30 s. As an internal standard control, the relative abundance of 16S rRNA was used to standardize the results. All assays were performed in triplicate. Primers used in RT-qPCR were listed in Additional file 8: Table S3. The result of RT-qPCR was calculated based on the following formula:

where Gi/A is the gene of interest in sample A, Gc/A is the gene of internal control in sample A, Gi/B is the gene of interest in sample B and Gc/B gene of internal control in sample B.

CoQ10 fermentation in Lab-scale bioreactors

For the lab-scale fermentation of CoQ10, three 1-L quadruple fermentation tanks (Bench-Top Bioreactor Multifors 2 type, INFORS HT, Switzerland) were used. The operation procedure was based on the method of Zhang et al. [13]. Seeds of R. sphaeroides were prepared as above shaking-flask cultivation. Subsequently, 16 mL of seeds were inoculated into tank with 0.8 L sterilizing medium B supplemented with 25 μg/mL kanamycin, and then, cultured at 32 °C for 96 h. The pH was maintained at 7.0. The aeration and agitation protocol were 1 vvm and 400 rpm during the whole fermentation. Bacterial growth (OD600), glucose concentration and CoQ10 titer were detected each 12 h.

Analytical methods

Cultured broth was fetched each 12 h for biomass determination at OD600 by spectrophotometer (MAPADA INSTRUMENTSUV-1800, China) and calculated using a calibration curve which indicated the relationship between OD600 and dry cell weight (DCW) (1OD600 approximately equaled to 0.40 g DCW/L). In this study, 100 mL of cultivated broth were centrifugated to obtain cell pellets, and then used to get dry cells through lyopilization for DCW measuring. Residual glucose was detected by a SBA-40 Biosensor (Biology Institute of Shandong Academy of Sciences, China). pH was measured at the starting and end of cultivation by a SevenCompact™ pH meter S220 (METTLER TOLEDO, China). The method of extraction and quantification of CoQ10 was according to Zhang et al. [13]. In the study, all experiments were repeated three times. The data shown in the corresponding tables and figures were the mean values of the experiments and the error bars indicated the standard deviation. Data was treated via one-way ANOVA method (P < 0.05).Statistical significance was determined using the SAS statistical analysis program, version 8.01 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

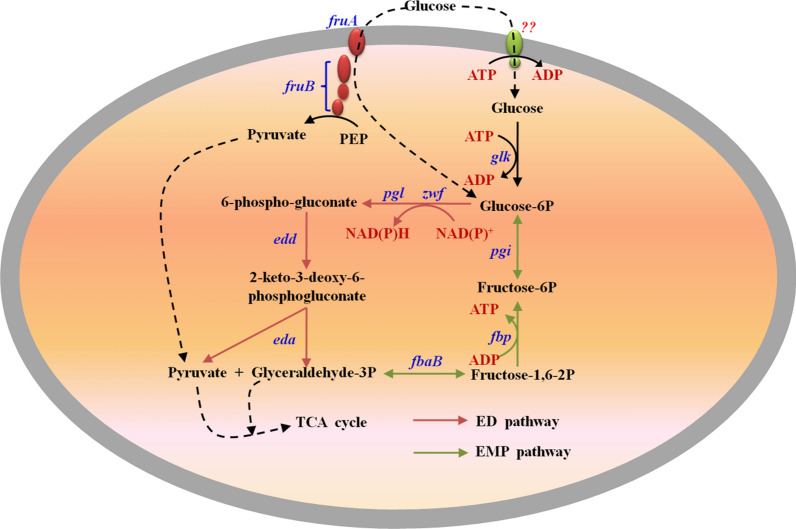

Potential glucose transmembrane pathways for R. sphaeroides ATCC 17023

By retrieving the NCBI database, the only integral PTS, fructose-specific PTS (PTSFru), was found in the genome of R. sphaeroides ATCC 17023, which is encoded by the gene cluster fruAB (RSP_1788 and RSP_1786). fruB encodes EI and HPr, the two sugar-nonspecific protein constituents of the PTS, and fruA encodes the sugar-specific transporter. It was reported that PTSFru encoded by fruAB simultaneously had a function of glucose transmembrane in some E. coil strains [6]. Additionally, fruAB in R. sphaeroides may have a similar function as that of the abovementioned E. coil strains. Glucose transported into cells with non-PTS must be phosphorylated before subsequent metabolism. Although the non-PTS-type glucose-specific transporter in R. sphaeroides ATCC 17023 has not been identified, the enzyme glucokinase (glk, RSP_2875), which plays a role in glucose phosphorylation, exists in the genome [5, 8]. Additionally, the glucokinase activity had been determined in some R. sphaeroides strains when cultured with glucose as the sole carbon source [21]. Considering the above information, R. sphaeroides ATCC 17023 should possess the non-PTS. R. sphaeroides ATCC 17023 metabolizes glucose exclusively with the Entner–Doudoroff pathway (ED) under aerobic and anaerobic conditions because of the lack of phosphofructokinase in the Embden–Meyerhof–Parnas pathway (EMP) [18]. According to the abovementioned analysis, metabolic networks that contain the glucose transmembrane and catabolism were constructed and the result is depicted in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Map of potential glucose transmembrane and metabolism pathways in R. sphaeroides ATCC 17023

Influence of PTS and non-PTS on bacterial growth and glucose metabolism

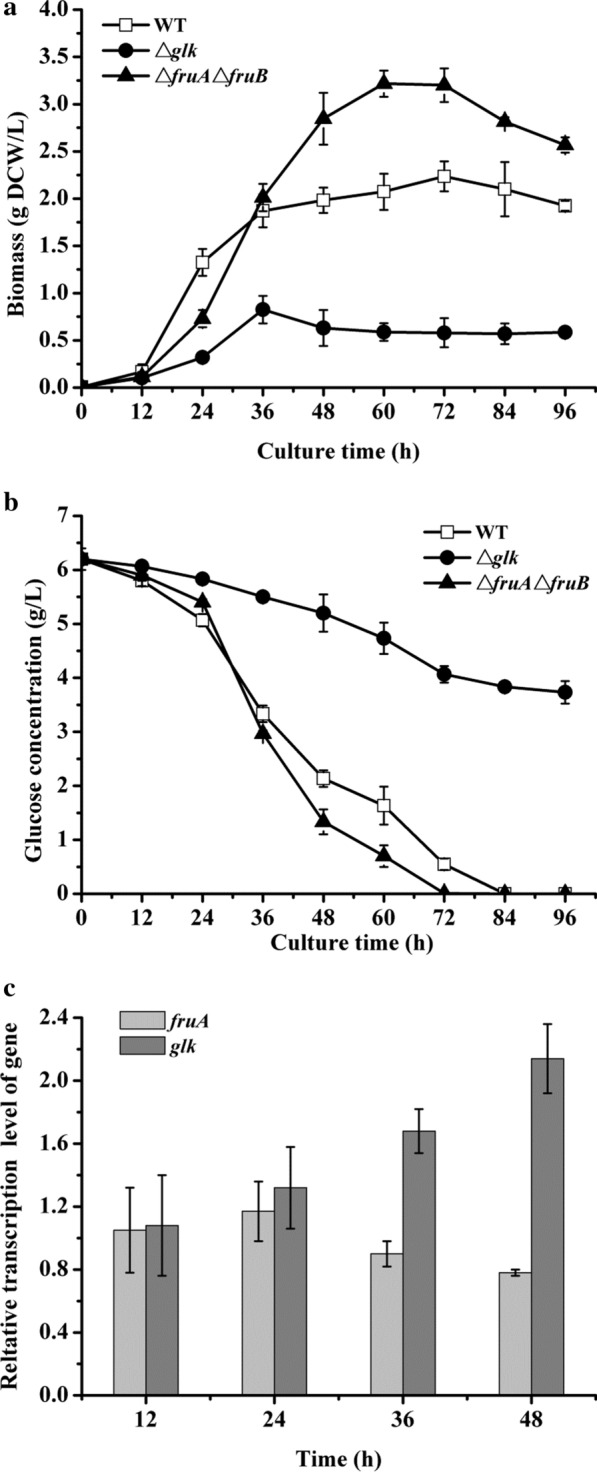

To clarify whether PTS (fruAB), non-PTS, or both of R. sphaeroides ATCC 17023 influences cellular glucose metabolism, two mutants (ΔfruAΔfruB and Δglk) were constructed using an in-frame markerless deletion method. The ΔfruAΔfruB was a mutant with double knock out of fruA and fruB. Considering that no non-PTS type glucose transporter has been identified in R. sphaeroides presently, glk was knocked out to study the function of non-PTS in glucose metabolism. Subsequently, these mutants’ growth and glucose consumption were studied under aerobic incubation using glucose as the sole carbon source (Fig. 2). All mutant strains showed a lag phase at the beginning of cultivation (between 0 and 12 h), which was similar to that of the R. sphaeroides ATCC 17023 (WT) (Fig. 2a). Evident variations were observed among these strains since then. The WT went into an exponential growth phase and displayed a rapid growth rate than others between 12 and 24 h. Furthermore, the ΔfruAΔfruB went into an exponential growth phase though the growth rate was slower than the WT; however, Δglk still showed a slow growth rate. After that, the growth rate of the WT became slower from 36 to 72 h, going into a decline phase at 72 h. ΔfruAΔfruB showed a faster growth rate between 24 and 36 h, and then the rate gradually slowed. The stationary growth phase was observed at approximately 60 h, and the decline phase appeared at 72 h for ΔfruAΔfruB. In contrast, Δglk continually kept a slow growth status between 24 and 36 h and went into a long stationary growth phase till the end of the experiment. Interestingly, the Biomax obtained by ΔfruAΔfruB was 3.22 ± 0.04 g DCW/L, which was much higher than that of the WT (Biomax was 2.23 ± 0.07 g DCW/L) (Table 2). Although the Δglk showed a typical bacterial growth process, both the growth rate and Biomax were much weaker than the WT during the whole culture process that the Biomax was 0.82 ± 0.01 g DCW/L achieved by the Δglk.

Fig. 2.

Growth and glucose metabolism of the WT and the mutant strains cultured in the MSMM, and RT-qPCR assay of the fruA and glk in the WT at different culture time. a Growth curves, b glucose concentration curves, and c relative transcription level

Table 2.

Growth and glucose consumption assay of the R. sphaeroides mutant strains and WT

| Strain | Time (h) | Glucose metabolism (g/L) | Biomax* (g DCW/L) | rglc** (g/L/h) | Yb/glc*** (g/g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | 84b | 6.21 ± 0.21a | 2.23 ± 0.07b (72 h) | 0.074 ± 0.003b | 0.36 ± 0.02b |

| Δglk | 96a | 2.47 ± 0.04b | 0.82 ± 0.01c (96 h) | 0.026 ± 0.001c | 0.33 ± 0.01c |

| ΔfruAΔfruB | 72c | 6.19 ± 0.16a | 3.22 ± 0.04a (60 h) | 0.086 ± 0.002a | 0.52 ± 0.03a |

*Biomax the maximum biomass; **rglc the average glucose consumption rate; ***Yb/glc biomass yield to glucose consumption vs. the Biomax. Statistics analysis was performed based on one-way ANOVA method and the data in the same column with the same letters (a–c) meant no significant difference (P ≤ 0.05)

Additionally, glucose concentration was determined simultaneously (Fig. 2b). At the beginning of cultivation (0–12 h), the strains showed slow glucose consumption rates (rglc) that fit the characteristics of the lag phase. During the culture time between 12 and 24 h, the WT and ΔfruAΔfruB sped up glucose consumption, though ΔfruAΔfruB had a little slower consumption rate than the WT. The result could explain the reason why ΔfruAΔfruB grew slower than the WT. Afterward, the residual glucose concentration in the group with ΔfruAΔfruB was less than the WT. Finally, ΔfruAΔfruB exhausted the glucose within 72 h, which was 12 h earlier than the WT. Compared with the WT, Δglk showed a low ability on glucose consumption during the entire process. After incubation for 96 h, there was still 3.73 ± 0.21 g/L residual glucose in the medium. The rglc of Δglk was only 0.026 ± 0.001 g/L/h, whereas the rglc of the ΔfruAΔfruB could get to 0.086 ± 0.002 g/L/h, which was approximately 1.18 times that of the WT (Table 2). Besides the rglc, the Yb/glc of the ΔfruAΔfruB was also promoted, approximately 43.4% higher than that of WT. Additionally, we constructed the mutant strains, ΔfruA and ΔfruB. The results revealed that the two mutants showed similar growth and glucose metabolism status as those of the ΔfruAΔfruB (unpublished data). Summarily, glk mutation seriously inhibited the growth and glucose metabolism of R. sphaeroides. Considering that glk is a vital gene involved in non-PTS, we speculated that the non-PTS played a major role in transporting glucose for R. sphaeroides ATCC 17023 during the entire process. However, deleting fruAB also influenced bacterial growth and glucose metabolism. The depressing effect of the fruAB mutation on growth appeared at the early incubation phase (12–24 h), whereas it showed a promotion effect on growth at the later phase (24–72 h). The influence of fruAB mutation on growth could be indirectly explained by the status of glucose metabolism. Therefore, we supposed that both the PTS and non-PTS had influence on glucose metabolism at the early culture phase. The relative transcriptional level of the fruA and glk in WT during cultivation was determined by RT-qPCR to verify the hypothesis further. The result was depicted in Fig. 2c, both fruA and glk showed an increasing tendency in the early culture phase (12–24 h). After that, the transcriptional level of fruA showed a decreased tendency since 36 h, whereas the glk still kept increasing from 36 to 48 h. Additionally, ΔfruAΔfruBΔglk was obtained through deleting the gene glk on the basis of ΔfruAΔfruB. Comparing with Δglk, both growth and glucose utilization were inhibited further at the early culture phase (Additional file 4: Fig. S4). To sum up, the results illustrate that both non-PTS and PTS have a function on glucose metabolism during the early phase, and the non-PTS played an important role in glucose metabolism.

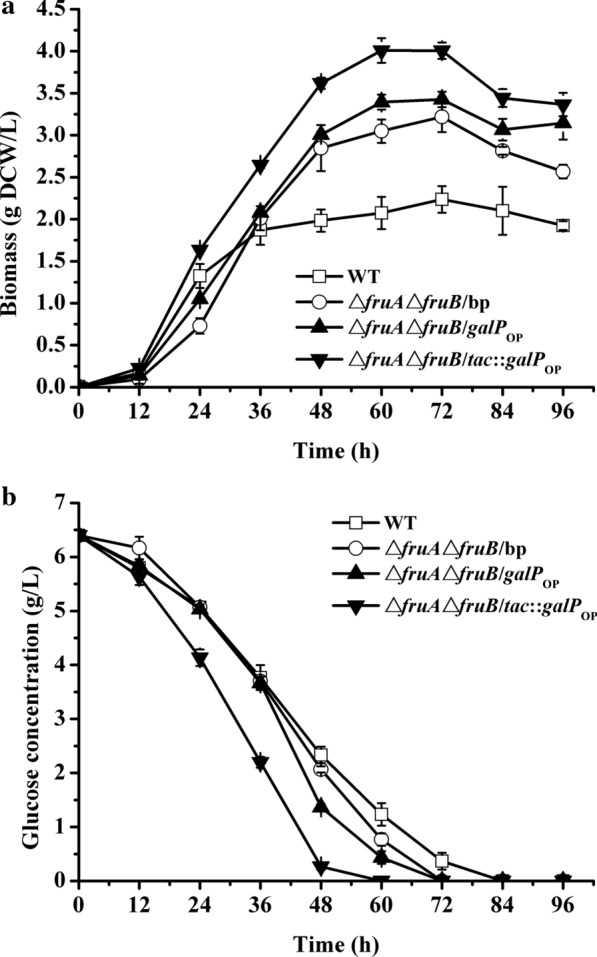

Enhancing the non-PTS pathway to promote cellular glucose metabolism

According to the above study, blocking the non-PTS inhibited the glucose metabolism of R. sphaeroides ATCC 17023. Whether over-expressing the non-PTS-type glucose transporter helps in improving glucose catabolism. In this section, the galactose:H+ symporter (galP) from E. coil K-12 substr. MG1655 was selected for the study. First, three mutants, ΔfruAΔfruB/bp, ΔfruAΔfruB/galPOP, and ΔfruAΔfruB/tac::galPOP, were constructed with the over-expression vectors, pBBR1MCS-2 and pBBR1MCS-2::tac. The ΔfruAΔfruB/bp was directly introduced to the blank plasmid in ΔfruAΔfruB. The ΔfruAΔfruB/galPOP was introduced to the plasmid, only harboring the gene, galP. The ΔfruAΔfruB/tac::galPOP is inserted with a strong promoter tac before the gene galP based on the pBBR1MCS-2::tac. Subsequently, these mutant strains were separately cultivated with glucose as the carbon source, and the biomass and glucose concentration was determined every 12 h. The ΔfruAΔfruB/bp showed almost no difference from that of ΔfruAΔfruB in growth and glucose metabolism (Fig. 3). This means that the plasmid introduction did not influence bacterial growth and glucose metabolism. Compared with ΔfruAΔfruB/bp, the growth rate of ΔfruAΔfruB/galPOP was increased at the early phase (12–24 h), but the growth status was the same as that of ΔfruAΔfruB/bp between 24 and 48 h (Fig. 3a). From 48 h, the biomass achieved by ΔfruAΔfruB/galPOP was higher than that of ΔfruAΔfruB/bp though the growth trends were similar. The higher biomass achieved by ΔfruAΔfruB/galPOP could be explained by the faster glucose consumption rate than the ΔfruAΔfruB/bp during this period. The result also suggested that the over-expression of galP could improve cellular glucose metabolism. For ΔfruAΔfruB/tac::galPOP, the growth improved further than ΔfruAΔfruB/galPOP at the early phase (12–24 h), and then, it still kept a fast growth status than others until the time glucose was nearly exhausted. Additionally, the biomass quantity achieved was higher than that of ΔfruAΔfruB/galPOP. The Biomax was 4.01 ± 0.15 g DCW/L achieved by ΔfruAΔfruB/tac::galPOP, which was the highest value among these strains. For glucose metabolism, ΔfruAΔfruB/tac::galPOP exhausted the glucose in the medium within 60 h, and the rglc reached 0.107 ± 0.003 g/L/h (Table 3). Furthermore, glk was overexpressed in ΔfruAΔfruB (ΔfruAΔfruB/tac::glk). However, both the growth and glucose metabolism decreased compared with ΔfruAΔfruB/bp (Additional file 5: Fig. S5). Additionally, the result suggested that the original glk transcriptional level was fitting for glucose metabolism. Maybe, over-expression of the glk produced excessive glucose-6-P, which is toxic to cells.

Fig. 3.

Growth and glucose metabolism of the WT and the mutant strains cultured in the MSMM. a Growth curves and b glucose concentration

Table 3.

Growth and glucose metabolism of R. sphaeroides strains

| Strain | Time (h) | Glucose metabolism (g/L) | Biomax* (g DCW/L) | rglc** (g/L/h) | Ybio/glc*** (g/g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | 84b | 6.21 ± 0.21a | 2.23 ± 0.07d (72 h) | 0.074 ± 0.003c | 0.36 ± 0.02b |

| ΔfruAΔfruB/bp | 72c | 6.18 ± 0.32a | 3.21 ± 0.11c (72 h) | 0.086 ± 0.002b | 0.52 ± 0.02c |

| ΔfruAΔfruB/ galPOP | 72c | 6.21 ± 0.12a | 3.43 ± 0.17b (72 h) | 0.086 ± 0.008b | 0.55 ± 0.05b |

| ΔfruAΔfruB/tac::galPOP | 60a | 6.20 ± 0.17a | 4.01 ± 0.15a (60 h) | 0.103 ± 0.003a | 0.65 ± 0.07a |

*Biomax the maximum biomass; **rglc the average glucose consumption rate; ***Ybio/glc biomass yield to glucose consumption versus the Biomax. Statistics analysis was performed based on one-way ANOVA method and the data in the same column with the same letters (a–d) meant no significant difference (P ≤ 0.05)

Improving CoQ10 productivity of R. sphaeroides

The CoQ10 content of these mutants was determined, and the result is presented in Table 4. Compared with the WT, Δglk, ΔfruAΔfruB, and ΔfruAΔfruB/tac::galPOP synthesized a low content of CoQ10 when incubated for 24 h; especially, the CoQ10 content of Δglk was 3.12 ± 0.04 mg/g DCW. After that, CoQ10 content of ΔfruAΔfruB and ΔfruAΔfruB/tac::galPOP was increased after 48 h, whereas the CoQ10 content of the WT and Δglk showed a slight reduction. As incubation proceeded (48–96 h), the CoQ10 content of the WT and Δglk stopped reducing and increased. Simultaneously, ΔfruAΔfruB and ΔfruAΔfruB/tac::galPOP increased in the CoQ10 content. Finally, the CoQ10 content of ΔfruAΔfruB and ΔfruAΔfruB/tac::galPOP reached 5.02 ± 0.18 and 5.11 ± 0.14 mg/g DCW, respectively. The maximum CoQ10 content of ΔfruAΔfruB/tac::galPOP was increased by 29.4% than the WT. It can be proposed that the mutation of fruAB improved Yb/glc and bacterial rglc but also enhanced the CoQ10 synthesis of R. sphaeroides. Moreover, strengthening glucose transportation by over-expressing galP showed little help to strengthen CoQ10 synthesis.

Table 4.

The CoQ10 content of WT and mutants cultured in SMM

| Culture time (h) | CoQ10 content (mg/g DCW) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | Δglk | ΔfruAΔfruB | ΔfruAΔfruB/tac::galPOP | |

| 24 | 3.79 ± 0.11a | 3.12 ± 0.04d | 3.23 ± 0.17c | 3.43 ± 0.16b |

| 48 | 3.62 ± 0.06b | 2.53 ± 0.33c | 3.65 ± 0.05b | 3.76 ± 0.21a |

| 72 | 3.83 ± 0.13b | 2.85 ± 0.05c | 4.97 ± 0.15a | 5.01 ± 0.33a |

| 96 | 3.95 ± 0.21c | 3.02 ± 0.19d | 5.02 ± 0.18b | 5.11 ± 0.14a |

Statistical analysis was performed based on one-way ANOVA and the data with the same letters (a–e) means no significant difference (P ≤ 0.05) for each line

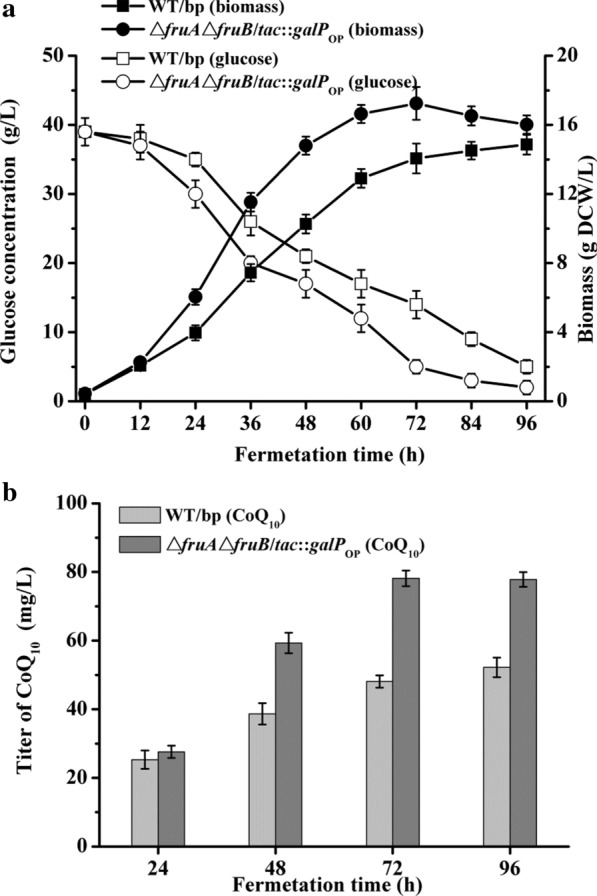

Although galP over-expression in ΔfruAΔfruB played no role in promoting the CoQ10 synthesis ability of R. sphaeroides, the strategy can promote glucose metabolism rate, which shortens the fermentation time. The inactivation of fruAB improved Yb/glc and the bacterial CoQ10 synthetic ability. Considering the advantages of the two strategies, ΔfruAΔfruB/tac::galPOP was applied to CoQ10 fermentation in a lab-scale tank (1 L), evaluating whether the CoQ10 fermentation is improved. ΔfruAΔfruB/tac::galPOP showed an evident improvement in growth compared with the WT/bp during the fermentation process (12–72 h) (Fig. 4a). The Biomax of ΔfruAΔfruB/tac::galPOP was harvested at 72 h of fermentation, which was 24 h earlier than the WT/bp. Moreover, the value of the Biomax reached 17.24 ± 0.97 g DCW/L, which was promoted by approximately 16% higher than that of the WT/bp (14.85 ± 0.57 g DCW/L). Simultaneously, the glucose concentration in the medium was almost exhausted after 72 h for ΔfruAΔfruB/tac::galPOP (< 5 g/L), whereas there was more than 10-g/L residual glucose residual for the WT/bp. In the aspect of CoQ10 synthesis (Fig. 4b), the yield gradually increased as the fermentation proceeded for both strains. At 48 h incubation, the yield of ΔfruAΔfruB/tac::galPOP showed a higher level than that of the WT/bp, and the phenomenon lasted to the end. The maximum CoQ10 titer of ΔfruAΔfruB/tac::galPOP reached 78.14 ± 2.31 mg/L, which was approximately 49.76% higher than that of the WT/bp. Moreover, ΔfruAΔfruB/tac::galPOP achieved the maximum CoQ10 titer at 72 h, which was 24 h earlier than the WT/bp.

Fig. 4.

Comparison of the growth, glucose metabolism and titer of CoQ10 of the WT and the ΔfruAΔfruB/tac::galPOP cultured in the fermentation medium B. a Growth and glucose concentration curves, and b Titer of CoQ10 during fermentation

Discussion

For many bacteria, PTSGlc is the first-selected pathway to transport exogenous glucose [6, 22]. After that, some other sugar-specific-PTSs, such as the PTSFru (fruAB), have been identified with the same function as that of the PTSGlc [6, 23]. In R. sphaeroides ATCC 17023, no PTSGlc-encoding genes are identified presently, but it has a PTSFru encoding gene cluster (fruAB). It is revealed that glucose metabolism and bacterial growth were influenced by the mutation of the fruAB in R. sphaeroides ATCC 17023 (Fig. 2). Interestingly, the result of fruAB mutation revealed two effects on bacterial growth during the whole culture process. It showed an inhibition effect at the early cultivation phase (12–24 h) and displayed a promoting effect at the late phase at 36 h. Finally, the Biomax received by ΔfruAΔfruB was much higher than that of the WT. The glucose metabolism of ΔfruAΔfruB also displayed a fit change characteristic vs. that of the growth change. Additionally, RT-qPCR assay revealed that the transcription level of the fruA in the WT kept a relatively high level at the early cultivation phase (12–24 h) and then decreased at 36 h. With the comprehensive analysis of the results, we supposed that the PTSFru in R. sphaeroides ATCC 17023 majorly joined in the glucose metabolism at the early cultivation phase. The PTSGlc is considered an effective way to utilize glucose because only one PEP is coupled with the translocation-phosphorylation of PTS carbohydrates when forming one ATP [6, 22]. In contrast, glucose utilization through a non-PTS transporter requires extra ATP to phosphate a carbohydrate molecule in the carbohydrate kinase reaction. Regarding energy consumption, bacteria synthesize cellular skeleton materials at the early cultivation phase, requiring a large amount of energy; thus, the PTS type system may be a good choice for saving energy at the early growth phase. As cultivation continued, the function of fruAB was weakened. The result might be due to the energy production ability of the bacteria, which is not as a limiting factor for cell growth after the lag phase. The high biomass achieved by ΔfruAΔfruB meant that more carbon fluxed to cellular assimilation metabolism. For the native glucose utilization pathway in E. coli, half of the PEP produced is used for glucose uptake and phosphorylation. PEP is an essential precursor for synthesizing many chemicals, such as succinate, malate, and aromatic compounds. In this sense, fruAB mutation might reduce PEP catabolism, which helps to synthesize cytoskeleton substances after the lag growth phase. The similar phenomenon is also found in the mutation of PTSNtr in P. putida, which is due to the enhancement of anabolism [16]. The phenomenon obtained from fruAB mutation is interesting though the mechanism is unclear. In future studies, more efforts will be put on disclosing the mechanism for promoting growth and its use.

The non-PTS composes of sugar transporters and glucokinase (glk). Glucose transports into cells by non-PTS in a non-phosphorylated form and then phosphorylated by the glucokinase for subsequent metabolism. A glk gene exists in the genome of R. sphaeroides ATCC 17023. The result revealed that the mutation of glk decreased bacterial growth when cultured in the medium with glucose as the sole carbon source. In addition, a poor glucose consumption status was observed for the mutant Δglk. RT-qPCR assay revealed that the transcriptional level of glk in WT kept an increased tendency as the cultivation continued. The above results revealed that the non-PTS played an important role in controlling glucose metabolism of R. sphaeroides ATCC 17023 during the culture process, especially since exponential growth phase, though the corresponding sugar-specific transporters were still unidentified. The result agrees with other R. sphaeroides strains [18].

Galactose permease (galP) is a galactose:H+ symporter belonging to the MFS [8]. It was reported that the E. coli PTS−glucose+ strain could transport glucose by a non-PTS mechanism as fast as its WT parental strain [23]. Further research showed that the gal regulon genes, which encode non-PTS transporter and enzymes for galactose metabolism, are enhanced in this mutant; furthermore, rapid glucose consumption depends on the low-affinity GalP. However, the over-expression of a heterogeneous galP in ΔfruAΔfruB improved the decrease in growth generated by the fruAB mutation at the early cultivation phase (Fig. 3). Alternatively, it could enhance glucose metabolism and promote biomass accumulation during the entire cultivation process. The results further illustrated that R. sphaeroides ATCC 17023 glucose metabolism mainly relied on the non-PTS. Additionally, it suggested the glucose transmembrane was an important limitation for the glucose metabolism of this bacterium. Furthermore, over-expressing glk was harmful to bacterial growth (Additional file 5: Fig. S5); bacterial glucose metabolism was also inhibited. Excessive glucose-6-p might be accumulated in the cytoplasm because of the over-expression of glk, which has toxic effect on bacterial metabolism. Finding an appropriate expression level of glk may solve the question.

Mutation of the fruAB influenced glucose metabolism and mediated the synthesis of CoQ10 in R. sphaeroides ATCC 17023. Presently, the mechanism of fruAB mutation on increasing bacterial CoQ10 synthesis is unknown. PEP is an important precursor for synthesizing aromatic compounds by the shikimate pathway. Aromatic compounds are vital sources of the benzene ring of CoQ10. Additionally, we previously knocked out the pyruvate kinase (pykA) of R. sphaeroides ATCC 17023, transforming PEP to pyruvate. The mutant showed higher CoQ10 content than that of the WT (unpublished data). Considering the relationship between PEP and CoQ10, we supposed that PTSFru inactivation might reduce the catabolism quantity of PEP, which was promoted more PEP flow to CoQ10 synthesis. However, the CoQ10 content of ΔfruAΔfruB/tac::galPOP showed no evident increase compared with that of ΔfruAΔfruB. The result suggested that only enhancing glucose transport cannot promote bacterial CoQ10 synthesis ability.

Conclusion

The two sugar transmembrane pathways in R. sphaeroides ATCC 17023 influenced growth and glucose metabolism. The PTSFru mutation revealed two effects on bacterial growth: inhibition at the early cultivation phase and promotion later. glk mutation decreased growth and glucose metabolism. Additionally, compared with the non-PTS, PTSFru had a relationship with CoQ10 synthesis that destroying the PTSFru could enhance bacterial CoQ10 synthesis ability. Enhancing glucose transport of the non-PTS with over-expressing a galactose:H+ symporter (galP) in ΔfruAΔfruB relieved the inhibition effect and enhanced growth. Moreover, the over-expression of galP has little effect on enhancing bacterial CoQ10 synthesis ability. According to the functional study of fruAB and glk, CoQ10 fermentation was improved through several modifications in glucose metabolism (constructed the ΔfruAΔfruB/tac::galPOP) and was verified as available for fermentation in 1 L bioreactors. Summarily, our study provided a new guidance for improving CoQ10 productivity of R. sphaeroides.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Fig. S1 (a) Construction flowchart of the glk gene deletion vector pK18mobsacB::glk-L-R; (b) Construction of glk gene deletion vector pK18mobsacB::glk-L-R; and (c) Filtration and verification of Δglk.

Additional file 2: Fig. S2 (a) Construction flowchart of the fruB gene deletion vector pK18mobsacB::fruB-L-R; (b) Construction of glk gene deletion vector pK18mobsacB:: fruA-L-R; (c) Construction of glk gene deletion vector pK18mobsacB:: fruB -L-R; (d) Filtration and verification of ΔfruA; and (e) Filtration and verification of ΔfruAΔfruB.

Additional file 3: Fig. S3 (a) Construction flowchart of the galP gene overexpression vector pBBR1MCS-2::tac:;galP; (b) Construction of he galP gene overexpression vector pBBR1MCS-2::tac:;galP; and (c) Filtration and verification of the ΔfruAΔfruB/tac::galPOP.

Additional file 4: Fig. S4 Growth and glucose metabolism of the WT and the mutant strains cultured in the MSMM. (a) Growth curves and (b) glucose concentration curves.

Additional file 5: Fig. S5 Growth and glucose metabolism of the ΔfruAΔfruB/bp and the ΔfruAΔfruB/tac::glk cultured in the MSMM.

Additional file 6: Table S1 Primers and restriction enzymes used in this study.

Additional file 7: Table S2 Primers used for mutant strains verification.

Additional file 8: Table S3 Primers used for RT-qPCR amplification.

Funding

This study was funded by the Project was Supported by the Foundation (No. 202012) of Qilu University of Technology of Cultivating Subject for Biology and Biochemistry, National Natural Science Foundation of China (31800108), Natural Science Foundation of Shandong (ZR2019QC019), Key Technology Research and Development Program of Shandong (2019GHY112026), and Key Research and Development Plan of Shandong Province (2018YYSP018).

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Yuying Yang and Lu Li have equal contribution to the study

Contributor Information

Zhengliang Qi, Email: qizhengliang@qlu.edu.cn.

Xinli Liu, Email: vip.lxl@163.com.

References

- 1.Li F, Zhao Y, Li B, Qiao J, Zhao G. Engineering Escherichia coli for production of 4-hydroxymandelic acid using glucose-xylose mixture. Microb Cell Fact. 2016;15:90. doi: 10.1186/s12934-016-0489-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tong X, Oh EK, Lee BH, Lee JK. Production of long-chain free fatty acids from metabolically engineered Rhodobacter sphaeroides heterologously producing periplasmic phospholipase A2 in dodecane-overlaid two-phase culture. Microbial Cell Fact. 2019;18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Wang S, Fang Y, Wang Z, Zhang S, Wang X. Improving l-threonine production in Escherichia coli by elimination of transporters ProP and ProVWX. Microb Cell Fact. 2021;20:58. doi: 10.1186/s12934-021-01546-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wurm DJ, Veiter L, Ulonska S, Eggenreich B, Herwig C, Spadiut O. The E. coli pET expression system revisited-mechanistic correlation between glucose and lactose uptake. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2016;100:8721–8729. doi: 10.1007/s00253-016-7620-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Poblete-Castro I, Binger D, Rodrigues A, Becker J, Martins dos Santos VAP, Wittmann C. In-silico-driven metabolic engineering of Pseudomonas putida for enhanced production of poly-hydroxyalkanoates. Metabol Eng. 2013;15:113–123. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2012.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Luo Y, Zhang T, Wu H. The transport and mediation mechanisms of the common sugars in Escherichia coli. Biotechnol Adv. 2014;32:905–919. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2014.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wurm DJ, Hausjell J, Ulonska S, Herwig C, Spadiut O. Mechanistic platform knowledge of concomitant sugar uptake in Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) strains. Sci Rep. 2017;7:45072. doi: 10.1038/srep45072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fordjour E, Adipah FK, Zhou S, Du G, Zhou J. Metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) for de novo production of l-DOPA from d-glucose. Microb Cell Fact. 2019;18:74. doi: 10.1186/s12934-019-1122-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chavarría M, Kleijn RJ, Sauer U, Pflüger-Grau K, Lorenzo VD. Regulatory tasks of the phosphoenolpyruvate-phosphotransferase system of Pseudomonas putida in central carbon metabolism. MBio. 2012;3:e00028–e112. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00028-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lu J, Tang J, Liu Y, Zhu X, Zhang T, Zhang X. Combinatorial modulation of galP and glk gene expression for improved alternative glucose utilization. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2012;93:2455–2462. doi: 10.1007/s00253-011-3752-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ikeda M. Sugar transport systems in Corynebacterium glutamicum: features and applications to strain development. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2012;96:1191–1200. doi: 10.1007/s00253-012-4488-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gonzy-Tréboul G, Zagorec M, Rain-Guion MC, Steinmetz M. Phosphoenolpyruvate:sugar phosphotransferase system of Bacillus subtilis: nucleotide sequence of ptsX, ptsH and the 5′-end of ptsI and evidence for a ptsHI operon. Mol Microbiol. 2010;3:103–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1989.tb00109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Su A, Chi S, Li Y, Tan S, Qiang S, Chen Z, Meng Y. Metabolic redesign of Rhodobacter sphaeroides for lycopene production. J Agric Food Chem. 2018;66:5879–5885. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.8b00855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang J, Gao D, Cai J, Liu H, Qi Z. Improving coenzyme Q10 yield of Rhodobacter sphaeroides via modifying redox respiration chain. Biochem Eng J. 2018;135:98–104. doi: 10.1016/j.bej.2018.04.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen X, Jiang X, Xu M, Zhang M, Huang R, Huang J, Qi F. Co-production of farnesol and coenzyme Q10 from metabolically engineered Rhodobacter sphaeroides. Microb Cell Fact. 2019;18:98. doi: 10.1186/s12934-019-1145-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee S, Tan TS, Kawamukai M, Chen ES. Cellular factories for coenzyme Q10 production. Microb Cell Fact. 2017;16:39. doi: 10.1186/s12934-017-0646-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Raizner AE, Quiones MA. Coenzyme Q10 for patients with cardiovascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77:609–619. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Imam S, Noguera DR, Donohue TJ. CceR and AkgR regulate central carbon and energy metabolism in Alphaproteobacteria. MBio. 2015;6:e02461–e12414. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02461-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fuhrer T, Fischer E, Sauer U. Experimental identification and quantification of glucose metabolism in seven bacterial species. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:1581–1590. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.5.1581-1590.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Luo Y, Ge M, Wang B, Sun C, Wang J, Dong Y, Xi J. CRISPR/Cas9-deaminase enables robust base editing in Rhodobacter sphaeroides 2.4.1. Microbial Cell Fact. 2021;19:93. doi: 10.1186/s12934-020-01345-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Szymona M, Doudoroff M. Carbohydrate metabolism in Rhodopseudomonas sphreoides. J Gen Microbiol. 1960;22:167–183. doi: 10.1099/00221287-22-1-167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kyselova L, Kreitmayer D, Kremling A, Bettenbrock K. Type and capacity of glucose transport influences succinate yield in two-stage cultivations. Microb Cell Fact. 2018;17:132. doi: 10.1186/s12934-018-0980-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saier MH., Jr Families of transmembrane sugar transport proteins. Mol Microbiol. 2000;35:699–710. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01759.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Fig. S1 (a) Construction flowchart of the glk gene deletion vector pK18mobsacB::glk-L-R; (b) Construction of glk gene deletion vector pK18mobsacB::glk-L-R; and (c) Filtration and verification of Δglk.

Additional file 2: Fig. S2 (a) Construction flowchart of the fruB gene deletion vector pK18mobsacB::fruB-L-R; (b) Construction of glk gene deletion vector pK18mobsacB:: fruA-L-R; (c) Construction of glk gene deletion vector pK18mobsacB:: fruB -L-R; (d) Filtration and verification of ΔfruA; and (e) Filtration and verification of ΔfruAΔfruB.

Additional file 3: Fig. S3 (a) Construction flowchart of the galP gene overexpression vector pBBR1MCS-2::tac:;galP; (b) Construction of he galP gene overexpression vector pBBR1MCS-2::tac:;galP; and (c) Filtration and verification of the ΔfruAΔfruB/tac::galPOP.

Additional file 4: Fig. S4 Growth and glucose metabolism of the WT and the mutant strains cultured in the MSMM. (a) Growth curves and (b) glucose concentration curves.

Additional file 5: Fig. S5 Growth and glucose metabolism of the ΔfruAΔfruB/bp and the ΔfruAΔfruB/tac::glk cultured in the MSMM.

Additional file 6: Table S1 Primers and restriction enzymes used in this study.

Additional file 7: Table S2 Primers used for mutant strains verification.

Additional file 8: Table S3 Primers used for RT-qPCR amplification.