Abstract

Cancer is one of the leading causes of death in the world. It is very important to find drugs with high efficiency, low toxicity, and low side effects for the treatment of cancer. Flavonoids and their derivatives with broad biological functions have been recognized as anti-tumor chemicals. 8-Formylophiopogonanone B (8-FOB), a naturally existed homoisoflavonoids with rarely known biological functions, needs pharmacological evaluation. In order to explore the possible anti-tumor action of 8-FOB, we used six types of tumor cells to evaluate in vitro effects of this agent on cell viability and tested the effects on clone formation ability, scratching wound-healing, and apoptosis. In an attempt to elucidate the mechanism of pharmacological action, we examined 8-FOB-induced intracellular oxidative stress and -disrupted mitochondrial function. Results suggested that 8-FOB could suppress tumor cell viability, inhibit cell migration and invasion, induce apoptosis, and elicit intracellular ROS production. Among these six types of tumor cells, the nasopharyngeal carcinoma CNE-1 cells were the most sensitive cancer cells to 8-FOB treatment. Intracellular ROS production played a pivotal role in the anti-tumor action of 8-FOB. Our present study is the first to document that 8-FOB has anti-tumor activity in vitro and increases intracellular ROS production, which might be responsible for its anti-tumor action. The anti-tumor pharmacological effect of 8-FOB is worthy of further investigation.

Keywords: 8-formylophiopogonanone B, anti-tumor, oxidative stress, apoptosis, cisplatin

Introduction

Cancer is a high death rate disease in modern society. Ever-increasing morbidity of cancer has become a major threat to public health [1]. Despite advances in diagnosis and treatment methods over the years, the treatment of cancer remains a daunting challenge [2]. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) is a major type of head and neck malignancies, which is particularly common in southern China, northern Africa, and Alaska [3–6]. Genetic susceptibility, dietary factors, environmental factors, etc. are the main pathogenic factors of NPC [7]. Currently, radiotherapy (RT) is the standard and primary treatment for NPC and effective in controlling early tumors with a good prognosis. Concurrent chemo-RT has been shown to greatly improve survival [8–11]. However, the cure rate of NPC depends on its stage. When it is in the advanced stage, the cure rate is low. At the time of diagnosis, there are more patients in the advanced stage [12]. Therefore, there is still an urgent need for developing new drugs for NPC therapies.

Flavonoids are low-molecular-weight polyphenols. They are widely found in the plant as secondary metabolites and characterized by a common C6–C3–C6 structure, which is connected by heterocyclic pyran rings and two benzene rings. Flavonoids have attracted extensive attention because of their broad biological activities such as anti-tumor, anti-oxidation, anti-diabetic, anti-virus, and immune regulation [13]. At present, >9000 flavonoids have been identified, some of which have been put into clinical use [14]. Due to its diverse biological activities, the continuous discovery of new and efficient flavonoids is of great significance for the treatment of many diseases. Many studies have shown that flavonoids or flavonoid derivatives play a key role in cancer chemoprevention and chemotherapy. In addition, a large number of epidemiological studies have shown that high intake of flavonoids may be related to the reduction of cancer risk, which provides evidence for the protective effect of flavonoids on cancer [15, 16]. 8-Formylophiopogonanone B (8-FOB; Fig. 1) was first isolated from Asparagaceae. Ophiopogon japonicus is a highly efficient economic crop in China, which is widely distributed in China, Japan, Southeast Asia, and other countries. It has long been used to make health tea for treating various diseases, such as lung disease and diabetes [17, 18]. 8-Formylophiopogonanone B is a class of isoflavonoids rich in the tubers of O. japonicas [19]. So far, there are few reports on 8-FOB bioactivity. Anti-tumor and other biological activities of 8-FOB have not been fully elucidated.

Figure 1.

Chemical structure of 8-FOB.

Superoxide radical (O2−•), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), hydroxyl radical (•OH), and singlet oxygen (1O2) are commonly defined reactive oxygen species (ROS). They are by-products produced by the metabolism of biological systems [20, 21]. ROS plays a dual role in biological systems. The beneficial effects of ROS are reflected in the resistance to infectious agents and in many cell signal transduction. On the contrary, oxidative stress indicated by high concentrations of intracellular ROS may destroy cell structure, including lipids and membranes, proteins, and nucleic acids [22, 23]. It has been reported that basic ROS levels are higher in cancer cells compared with their normal counterparts. On the other hand, cancer cells are more susceptible to intracellular ROS induction [24]. Therefore, enhancing intracellular ROS production is generally considered as an effective method to treat cancers.

Given that flavonoids have a wide range of biological effects, we wonder whether 8-FOB has potential anti-tumor pharmacological action. Therefore, we conducted this study to explore the potential anti-tumor effects of 8-FOB in vitro and the possible mechanism for its pharmacological action in NPC CNE-1 cells.

Materials and Methods

Materials and reagents

8-Formylophiopogonanone (8-FOB, purity ≥98.0%) was purchased from Chengdu Manster Biotechnology Co., Ltd (Chengdu, China). 8-FOB dry powder was freshly dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, USA) and stored at −20°C before use. Cisplatin was purchased from MedChemExpress (St. Louis, MO, USA) and N-acetylcysteine (NAC) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). They were all dissolved in distilled deionized water and stored at −20°C before use.

Six cell lines including human NPC CNE-1 cells, CNE-2 cells,mouse Albino neuroblastoma (Neuro-2a) cells, human hepatocellular carcinoma SK-Hep1 cells, human cervical cancer HeLa cells, and human gastric carcinoma MGC-803 cells were purchased from the Cell Resource Center at the Shanghai Institutes for the Biological Sciences, Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China). All chemicals and assay kits were commercially obtained as described below in detail.

Cell culture

The CNE-1 and CNE-2 cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (PAN, Germany), 100 U/ml penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) at 37°C with 5% CO2 incubator.

The Neuro-2a cells, SK-Hep1 cells, HeLa cells, and MGC-803 cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) medium (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (PAN, Germany), 100 U/ml penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) at 37°C with 5% CO2 incubator.

Cell viability assay

Cell viability was measured by the cell counting kit-8 assay (CCK-8, Dojindo, Japan) in 96-well plates. To determine dose- and time-dependent effects on cell viability, 0, 25, 50, 100, and 200 μM 8-FOB and 15 μM cisplatin (as the positive control of cytotoxicity in tumor cells) were added and incubated for 3, 6, 12, 24, and 48 h. Then, 10 μl CCK-8 solution was added to each well and incubated at 37°C for 1 h. Absorbance was recorded at 450 nm by a microplate reader (Infinite M200 PRO, TECAN, Switzerland).

Colony formation assay

CNE-1 cells were seeded in 6-well plates with 2000 cells/well. 50, 100, and 150 μM 8-FOB and 15 μM of cisplatin were added to the culture medium and incubated for 24 h. After washing cells with culture medium for three times, fresh medium was added and then changed every 2 days to maintain cell growth continuously for 14 days. The cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, stained with crystal violet (Bmole Bioscience Inc (BBI), Shanghai, China) for 15 min. Observation on colony formation was performed under an inverted microscope (Leica, Germany).

Measurement of intracellular ROS

Intracellular ROS was detected using Reactive Oxygen Species Assay Kit (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, Shanghai, China) as described previously [25]. Briefly, the CNE-1 cells were seeded in 96-well black plates. Cells were loaded with DCFH-DA fluorescence probe for 20 min at 37°C after different treatments followed by washing with serum-free medium twice. Fluorescence intensity was measured by using a microplate reader (Infinite M200 PRO, TECAN, Switzerland) with an excitation wavelength of 488 nm and an emission wavelength of 525 nm.

Measurement of the mitochondrial membrane potential

The mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) was measured using the JC-1 Assay Kit (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, Shanghai, China) as described previously [26]. The cells were seeded in 96-well black plates. After different treatments, the cells were incubated with JC-1 for 20 min at 37°C and washed twice with Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS, Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, Shanghai, China). The red and green fluorescence intensity were recorded by using microplate reader (Infinite M200 PRO, TECAN, Switzerland) with 560 nm excitation/590 nm emission, and 488 nm excitation/525 nm emission. The ratio of red fluorescence intensity to green fluorescence intensity indicates the change of MMP.

Measurement of ATP levels

The intracellular ATP content was assessed using a CellTiter-Lumi™ Luminescent Cell Viability Assay Kit (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, Shanghai, China). CNE-1 cells were seeded in a 96-well black plates. After different treatments, 100 μl CellTiter-Lumi ™ Luminescent detection reagent was added to the plates and incubated at room temperature for 10 min. The luminescence intensity was detected immediately by a microplate reader (SpectraMax Gemini EM, Molecular Devices, USA).

Determination of 8-OHdG levels

8-Hydroxy-2-deoxy-guanosine (8-OHdG) is known as a by-product of oxidative damage of DNA [27]. 8-FOB-induced DNA damage was determined using a DNA Oxidative Damage ELISA kit (StressMarq, Victoria, Canada) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, after the cells were treated with 8-FOB and cisplatin, the genomic DNA of the cells was extracted with a DNA extraction kit (Tiangen, Beijing, China). The extracted DNA was processed with nuclease P1 (New England Biolabs, USA) and Calf Intestinal Alkaline Phosphatase (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). The absorbance value at 450 nm was detected. The concentration of 8-OHdG was calculated according to the standard curve.

Scratching wound-healing assay

CNE-1 cells were seeded into 96-well plates at a density of 3 × 104/well. When the cell density reached ~90% and a cell monolayer was formed, a line was drawn along the bottom of the culture plate using Woundmaker system (Essen BioScience, USA). After three washes in phosphate buffer saline (PBS) (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, Shanghai, China), cells were treated with different concentrations of 8-FOB and cisplatin. Images of the area of the wounded region lacking cells were taken and analyzed with an Incyte Zoom system (Essen BioScience, USA) at 0, 12, 24, and 48 h.

Cell invasion assay

The transwell chambers (Corning, NY, USA) were coated with liquid Matrigel (Corning, NY, USA) at 37°C for incubation 3 h. CNE-1 cells with serum-free RPMI-1640 medium were seeded into the upper chamber, RPMI-1640 medium (600 μl) with 10% FBS was added to the lower chamber. Next, the cells were placed into an incubator with a saturated humidity of 5% CO2 at 37°C for 24 h. The cells that migrated to the underside of the membrane were fixed and stained with crystal violet, and 10× microscopic fields were counted under an inverted microscope (Leica, Germany).

4′, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole staining

The morphological changes of apoptosis were observed with the fluorescent nuclear dye 4′, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, Shanghai, China). Briefly, the assay was performed on CNE-1 cells treated with the indicated concentrations of 8-FOB and cisplatin. After incubation, the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min, and then stained with DAPI for 10 min. The fluorescence intensity of cells was detected under a fluorescence microscope (Leica, Germany).

Apoptosis assay

Annexin V-fluorescein isothiocyanate (Annexin V-FITC) and propidium iodide (PI) double staining were used to detect apoptotic cells by flow cytometry with the FITC Annexin V Apoptosis Detection Kit I (BD Biosciences, USA) [26]. CNE-1 cells were seeded in 6 cm dishes. After different treatments, cells were harvested,washed twice with cold PBS and resuspended in binding buffer. Then, cells were incubated with Annexin V-FITC (5 μl) and PI (5 μl) for 15 min in the dark. Apoptotic cells were analyzed with the flow cytometry (BD Accuri C6, USA).

Western blotting

Cultured cells were treated with various concentrations of 8-FOB and cisplatin for 24 h, then washed with ice-cold PBS and lysed in radio-immunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) (Beyotime, Shanghai, China) containing 1% protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, Switzerland). The cell lysates were centrifuged at 20 000 g for 30 min at 4°C, and the supernatants were collected. The protein concentrations were determined by the BCA Protein Assay Kit (Beyotime, Shanghai, China). Sample buffer was added, then boiled for 15 min, resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes according to standard procedures [28]. The membranes were blocked in QuickBlock™ Blocking Buffer (Beyotime, Shanghai, China) for western blot and then incubated with the primary antibodies at 4°C overnight. The primary antibodies used are listed as follows: Bax (1:1000, Proteintech, 50 599-2-Ig), Bcl-2 (1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology, 4223), Cleaved PARP (1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology, 5625), Cleaved-Caspase-3 (1:1000, Merck Millipore, MAB10753), cytochrome c (1:1000, BioWorld, BS5679), and β-Actin (1:5000, Sigma, A5441). The blots were then rinsed and hybridized with HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG or goat anti-mouse IgG for 1 h at room temperature. At last, Luminata Forte Western HRP Substrate (Merck Millipore, USA) was added, using a ChemiDoc XRS+ System to view the protein bands.

Toxicity study in mice

To determine whether 8-FOB oral administration is toxic to liver and kidney, we performed a preliminary in vivo study in mice to examine the toxic damage after 8-FOB administration. Male C57BL/6 mice (20–24 g) aged 8 weeks were supplied by the animal center of the Army Medical University (Chongqing, China). The animals were housed under controlled conditions (22 ± 2°C, 60–70% air humidity, and 12-h light/dark cycle) and received a standard mouse chow and tap water ad libitum during the entire experiment. All animals were allowed to acclimate for 1 week prior to the first treatment. The animal experiments were approved by the Third Military Medical University Animal Care and Use Committee. Mice were randomly divided into three groups (n = 6), which were treated with sterile water (control),0.5% CMC-Na (solvent), and 20 mg/kg 8-FOB (dissolved in 0.5% CMC-Na), respectively by intra-gastric administration for 7 consecutive days. All mice were observed daily for a total of 7 days. After the observation period, Mice in these three groups were sacrificed. Blood, liver, and kidney samples were collected for analysis.

Hematological and biochemical analysis

Hematological parameters including hemoglobin, red blood cell count (RBC), white blood cell count (WBC), platelets, percentage of lymphocytes (LC%), percentage of neutrophils (NP%), and percentage of monocytes (MC%) in mice of three groups were tested with an automatic hematology analyzer (Mindray, BC-2800vet, China). According to the manufacturer’s instructions, the serum levels of alanine transaminase (ALT), aspartate transaminase (AST), blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine (CR), and uric acid (UA) were measured with the commercially available test kits (Rayto, Shenzhen, China), respectively.

Histopathological analysis

Histopathological examination of liver and kidney organs was conducted to assess the toxic effects of 8-FOB. Liver and kidney samples fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde were embedded in paraffin, sectioned at 4 μm and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Stained sections were visualized using a microscope (Eclipse Ci, Nikon, Japan).

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was carried out by using GraphPad Prism 7.0, and the data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation. One-way analysis of variance followed by the Tukey multiple comparison test was employed to test the significance. Student’s t-test was employed to test the differences between the two groups.

Results

8-FOB suppressed cell viability in different type of tumor cells

To investigate the cytotoxic effect of 8-FOB on cancer cell lines (CNE-1 cells, CNE-2 cells, Neuro-2a cells, SK-Hep1 cells, HeLa cells, and MGC-803 cells), we treated these cells with 8-FOB and cisplatin (an effective cytotoxic drug for cancer therapy served as a positive control). The cell viability was measured by CCK-8 assay. The results showed that 8-FOB significantly inhibited viability of these cells in a dose-dependent manner in all six types of tumor cells (Fig. 2). The 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) values for 8-FOB treated on CNE-1 cells, CNE-2 cells, Neuro-2a cells, SK-Hep1 cells, HeLa cells, and MGC-803 cells for 24 h were 140.6, 155.2, 181.9,250.5, 333.9, and 292.6 μM, respectively (Fig. 2A–F). At the same time, cisplatin, as expected, also markedly reduced the viability of these cancer cells. CNE-1 and CNE-2 cells, two types of NPC cells with different degrees of differentiation, are generally used for testing anti-tumor action on NPC. With the lowest IC50 value, 8-FOB showed the most potent effect on CNE-1 cells. In the dose- and time- effects studies, it was found that 8-FOB treatment suppressed cell viability in CNE-1 cells in a dose- and time-dependent manner (Fig. 3A–D). When cells were treated with 50, 100, and 200 μM 8-FOB, the cell viability was significantly decreased at 48 h post treatment (P < 0.01 vs control respectively; Fig. 3D). Overall, these data suggested that 8-FOB significantly suppressed cell viability with the highest potency in CNE-1 cells. Therefore, we focused our attention to explore how 8-FOB exerted cytotoxic anti-tumor effect on CNE-1 cells in the following experiments.

Figure 2.

Dose-dependent cytotoxicity of 8-FOB in CNE-1, CNE-2, Neuro-2a, SK-Hep1, HeLa, and MGC-803 cells. Cell viability was measured by a CCK-8 assay. The calculation of the corresponding mean IC50 fit curve was performed. (A) CNE-1 cells; (B) CNE-2 cells; (C) Neuro-2a cells; (D) SK-Hep1 cells; (E) HeLa cells; and (F) MGC-803 cells. The values are presented as the means ± SD from three independent experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs control (0 μM 8-FOB).

Figure 3.

8-FOB induced time-dependent cytotoxicity and dose-dependent inhibition of colony formation in CNE-1 cells. Cell viability was measured by the CCK-8 assay and colony formation was observed at 14 days post 8-FOB treatment. (A–D) Changes of cell viability after 8-FOB treatment. (E) Inhibition of colony formation. The values are presented as the means ± SD from three independent experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs control (0 μM 8-FOB).

8-FOB inhibited colony formation in CNE-1 cells

Since 8-FOB could effectively suppressed cell viability in CNE-1 cells, we next tested the action of inhibiting colony formation, a well-defined pharmacological marker of anti-tumor. CNE-1 cells were treated with different concentrations of 8-FOB and 15 μM cisplatin as control, the clonogenic potential of the cells dose-dependently was obviously reduced with the increase in 8-FOB concentration (Fig. 3E).

8-FOB suppressed cell migration and invasion in CNE-1 cells

Scratching wound-healing and transwell assay are generally accepted as the indicators to assess tumor cell migration and invasion abilities. Therefore, we further evaluated whether 8-FOB is effective to suppress tumor cell migration and invasion in vitro. CNE-1 cells were treated with 50, 100, and 150 μM 8-FOB and cell migration was recorded at 12, 24, and 48 h after scratching. As shown in the representative images of Fig. 4A and C, 8-FOB dose- and time-dependently inhibited cell migration (P < 0.01 vs control at different times respectively). In evaluation of cell invasion after 8-FOB treatment, it was found that the invasion ability of CNE-1 cells was dose-dependently depressed by 8-FOB treatment. The relative invasion rate of CNE-1 cells was significantly lower than that of control (P < 0.01 vs control, Fig. 4B and D). These data suggested that 8-FOB effectively inhibited cell migration and invasion in CNE-1 cells.

Figure 4.

8-FOB time- and dose-dependently suppressed cell migration and invasion in CNE-1 cells. (A) Representative images of scratching wound-healing assay. (B) Representative images of invaded cells. (C) Time-course changes of wound density. (D) Dose-dependent changes of cell invasion. Scale bar: 80 μm. The values are presented as the means ± SD from three independent experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs control (0 μM 8-FOB).

Figure 8.

Histopathological analysis of liver and kidney in mice with 8-FOB oral administration. Representatives of histopathological changes in mouse liver and kidney. Scale bar: 20 μm.

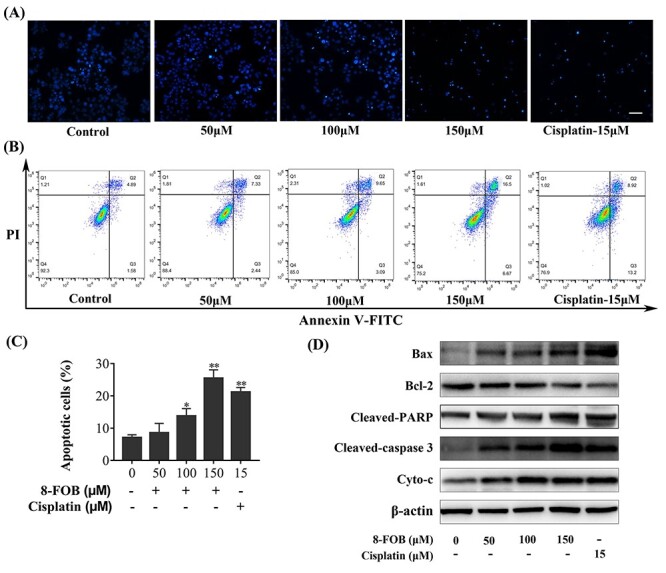

8-FOB induced apoptosis on CNE-1 cells

Cytotoxic effect of anti-tumor agents usually induces cell death in the way of apoptosis. To further investigate whether the suppression of cell viability could induce apoptosis in CNE-1 cells, we performed the flow cytometry analysis to determine apoptotic cells after 8-FOB treatment. After cell nucleus was stained with DAPI, it was found the number of cells stained nucleus was declined compared with control (Fig. 5A). Furthermore, 8-FOB treatment dose-dependently elevated the percentage of apoptotic cells determined at 24 h after treatment (P < 0.05, P < 0.01 vs control at 100 and 150 μM 8-FOB, respectively; Fig. 5B and C). In accordance with the induction of apoptosis, 8-FOB markedly activated apoptotic pathway in CNE-1 cells at 24 h after treatment. The expression of pro-apoptotic protein Bax was obviously upregulated and the expression of anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2 was markedly downregulated (Fig. 5D). Moreover, all markers of apoptosis including cleaved-PARP, cleaved-Caspase-3, and Cyto-c were increased at 24 h after treatment as shown in Fig. 5D. Collectively, these results revealed that 8-FOB induced apoptosis on CNE-1 cells.

Figure 5.

8-FOB induced apoptosis in CNE-1 cells. (A) Morphological observation on apoptotic cells stained by DAPI. Scale bar: 80 μm. (B) Representatives of apoptosis analyzed by flow cytometry. The Annexin V-FITC-/PI- population reflects normal healthy cells (Q4); Annexin V-FITC+/PI- cells, early apoptosis (Q3); Annexin V-FITC+/PI+ cells late apoptosis or necrosis (Q2); Annexin V-FITC-/PI+ cells, necrotic cells (Q1). (C) Quantification of apoptotic cells. (D) Detection of Bax, Bcl-2, Cleaved PARP, Cleaved caspase-3 and Cyto-c expression by western blotting. The values are presented as the means ± SD from three independent experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs control (0 μM 8-FOB).

8-FOB induced ROS generation and mitochondrial dysfunction in CNE-1 cells

ROS produced either from the action of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase (NOX) or from the mitochondrial respiratory chain, was reported to play crucial roles in apoptosis induction [29] and pharmacological action of anti-tumor. It is generally accepted that the elevation of intracellular ROS and during cellular oxidative stress could impair mitochondrial function [30]. 8-OHdG is recognized as one of the most abundant oxidation products in oxidative damage to DNA [31]. Disrupting mitochondrial function in tumor cells is a practical strategy to treat cancers. Therefore, we tried to assess whether 8-FOB could induce ROS generation and mitochondrial dysfunction. As shown in Fig. 6A, 8-FOB dose-dependently increased total intracellular ROS levels (P < 0.05, P < 0.01 vs control at 50, 100, and 150 μM, respectively). To delineate the changes of the mitochondrial function with 8-FOB treatment, we found that 8-FOB suppressed MMP significantly (P < 0.01 vs control; Fig. 6B) and increased oxidative damage to DNA indicated by the elevation of 8-OHdG levels (P < 0.05, P < 0.01 vs control at 100 and 150 μM respectively; Fig. 6D). In the analysis of dose- and time- effects of 8-FOB treatment on intracellular ATP contents, it was demonstrated that 8-FOB markedly reduced intracellular ATP levels in a dose- and time- dependent manner. At 48 h post 8-FOB treatment, the ATP levels in cells treated with 50, 100, and 150 μM 8-FOB were significantly reduced (P < 0.01 vs control; Fig. 6C). These findings suggested that 8-FOB could markedly induce ROS generation and disrupt mitochondrial function.

Figure 6.

8-FOB induced intracellular oxidative stress, DNA damage and mitochondrial dysfunction in CNE-1 cells. (A) Dose-dependent changes of total intracellular ROS levels determined at 24 h. (B) Dose-dependent changes of MMP determined at 24 h. (C) Time- and dose-dependent changes of cellular ATP levels. (D) Dose-dependent changes of 8-OHdG level determined at 24 h. The values are presented as the means ± SD from three independent experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs control (0 μM 8-FOB).

NAC treatment suppressed intracellular ROS elevation and apoptosis in CNE-1 cells

It is well-known that increased ROS production could consequently impair mitochondrial function and induce apoptosis. To elucidate whether ROS production is responsible for cytotoxic effects of 8-FOB and apoptosis induction, we further used N-acetylcysteine (NAC), a potent ROS scavenger treating CNE-1 cells and assessed 8-FOB induced cytotoxicity. NAC is a thiol-containing antioxidant that has been used to mitigate various conditions of oxidative stress by scavenging intracellular ROS. Its antioxidant action is believed to originate from its ability to stimulate glutathione (GSH) synthesis, therefore maintaining intracellular GSH levels [32, 33] and scavenging ROS [34]. We found that NAC treatment significantly protected 150 μM 8-FOB-induced cell viability decline (P < 0.01 vs 150 μM 8-FOB; Fig. 7A). 1 mM NAC treatment markedly suppressed 150 μM 8-FOB-induced intracellular ROS elevation (P < 0.01 vs 150 μM 8-FOB; Fig. 7B). Moreover, NAC treatment significantly inhibited 8-FOB-induced apoptosis (P < 0.01 vs 150 μM 8-FOB; Fig. 7C and D). Furthermore, we verified the anti-tumor effects of 8-FOB treatment in another NPC cell line. Results indicated that 150 μM 8-FOB treatment significantly suppressed cell viability, elevated intracellular ROS level and induced apoptosis in CNE-2 cells (P < 0.01 vs control; Fig. 7E, F, G, and H).

Figure 7.

NAC treatment protected against 8-FOB induced cytotoxicity in CNE-1 cells. (A) Cell viability was preserved by NAC treatment. (B) Suppression of intracellular ROS elevation by NAC treatment. (C and D) Inhibition of 8-FOB induced apoptosis by NAC treatment. To further verify whether 8-FOB is effective in other type of NPC cells, we used CNE-2 cells to test its anti-tumor efficacy (Fig 7E–H). The values are presented as the means ± SD from three independent experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs control (0 μM 8-FOB); ## P < 0.01 vs the 8-FOB group.

8-FOB treatment showed no toxicity on hepatic and renal function

The changes of hepatic and renal function are usually used to screen the toxic effects of chemical agents in the model of in vivo animal study. To preliminarily understand whether 8-FOB is toxic to the liver and kidney, we conducted the experiments to observe hepatic and renal toxicities in C57/6 J mice. During the acute phase of 7 days’ observation, we found no death and toxic signs occurred in 8-FOB treated mice. The behaviors, food/water intakes, and body weights (Table 1) were as normal as the control. As shown in Tables 1 and 2, there were no significant changes in hematological and biochemical indexes. Histopathological observation on the liver and kidney showed no morphological change (Fig. 8). Taken together, there are no toxic effects observed in mice with 8-FOB treatment.

Table 1.

Body weight and hematological parameters of mice with different treatments

| Parameters | Treatment | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Solvent | 8-FOB | |

| Body weight (g) | 22.04 ± 2.04 | 22.65 ± 1.244 | 22.47 ± 1.144 |

| Hemoglobin (g/l) | 143.7 ± 3.502 | 139.8 ± 9.538 | 141.5 ± 8.826 |

| RBC (1012 l−1) | 8.697 ± 0.2455 | 8.438 ± 0.6162 | 8.718 ± 0.5645 |

| WBC (109 l−1) | 5.283 ± 2.332 | 5.267 ± 2.693 | 5.933 ± 1.583 |

| Platelets (109 l−1) | 987.2 ± 219.2 | 1027 ± 136.3 | 1020 ± 152.9 |

| LC (%) | 74.02 ± 2.175 | 73.87 ± 3.396 | 76.38 ± 4.034 |

| NP (%) | 21.88 ± 2.178 | 22.23 ± 3.04 | 20.03 ± 3.456 |

| MC (%) | 4.1 ± 0.1633 | 3.9 ± 0.2066 | 3.583 ± 0.2428 |

The values are presented as the means ± SD (n = 6). **P < 0.01 and *P < 0.05 vs control.

Table 2.

Biochemical parameters of mice with different treatments

| Parameters | Treatment | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Solvent | 8-FOB | |

| ALT (U l−1) | 33.23 ± 4.594 | 30.58 ± 12.36 | 30.68 ± 6.423 |

| AST (U l−1) | 135.6 ± 23.43 | 137.6 ± 24.94 | 131 ± 36.21 |

| BUN (mg dl−1) | 21.92 ± 2.047 | 20.96 ± 1.147 | 19.93 ± 2.138 |

| CR (μmol l−1) | 12.92 ± 1.756 | 10.94 ± 1.367 | 14.09 ± 3.047 |

| UA (μmol l1) | 269.9 ± 54.09 | 242.1 ± 77.76 | 202.6 ± 51.31 |

The values are presented as the means ± SD (n = 6). **P < 0.01 and *P < 0.05 vs control.

Figure 9.

Graphical Abstract Schematic diagram of anti-tumor action of 8-FOB treatment in CNE-1 cells.

Discussion

In our present study, we demonstrated that 8-FOB has anti-tumor effects in six types of tumor cells. The most potent anti-tumor effect appeared in CNE-1 cells with the lowest IC50 value. The anti-tumor effects of 8-FOB were characterized by suppressing cell viability, inhibiting cell migration and invasion, producing oxidative DNA damage, and inducing apoptosis. In exploring the pharmacological mechanisms of anti-tumor action, we revealed that 8-FOB treatment resulted in the increased production of intracellular ROS and disrupted mitochondrial function. As a naturally existed isoflavonoid compound, 8-FOB has many unappreciated biological actions for clinical use. Our study is the first to document the in vitro anti-tumor effect of 8-FOB treatment in tumor cells.

Given that oncology is currently one of the most active therapeutic fields, the research and development of anti-tumor drugs has aroused great interest worldwide. At present, many anti-tumor drugs are used in clinical practice, but there are many problems, such as low therapeutic efficiency, high toxicity, poor selectivity, and drug resistance of cancer cells. Looking for new anti-tumor drugs with high selectivity and low side effects is still the focus of new anti-tumor drug development. It takes a lot of time and money to screen the huge amount of natural extracts and synthetic compounds for finding the effective candidates. In vitro studies conducted in cancer cell models are generally accepted as an important approach to screen drug candidates and evaluate the drug-ability. Whether 8-FOB could have anti-tumor action is still puzzling. There are no data to document this issue in previous studies on biological actions of 8-FOB. Our study provided the evidence that 8-FOB shows anti-tumor effect in vitro and might be worthy of being considered as an effective candidate for further investigation in innovative drug research.

Cancer is a multifactorial heterogeneous disease and the leading cause of death worldwide. The main obstacle to increasing life expectancy in the 21st century is to treat cancer patients effectively [35, 36]. Abnormal cell growth, strong migration, and invasion capabilities are the main characteristics of cancer [37]. Developing anti-tumor drugs from natural products is one of the major strategies in combating human cancers [38]. Among all kinds of natural products, flavonoids have attracted much attention because of their excellent pharmacological activities. There are growing evidences from epidemiological and laboratory studies that dietary flavonoids can reduce the risk of developing certain types of cancers [39]. It has been reported in the literature that plant-derived bioactive compounds are important preparations for preventing and/or reducing various human diseases (such as cancer, inflammation, cardiovascular, and neurodegenerative diseases) [40]. Among these plant bioactive ingredients, flavonoids and flavonoid derivatives account for a large proportion. In recent years, flavonoids and their synthetic analogues, as the effective candidates of anti-tumor drugs, have been extensively studied. Flavonoids such as quercetin, genistein, or flavopiridol have entered advanced clinical trials. Some of these flavonoids have been used in a variety of oncology indications [41, 42]. It is reported that flavonoids can exert their anti-tumor effects because of their abilities to block cell cycle, destroy mitotic spindle formation [43], and induce apoptosis [44]. For instance, Hesperidin can induce the expression of cytochrome c, APAF-1, and caspase-3 and caspase-9 in gastric cancer cells and reduce the ratio of Bax to Bcl-2, resulting in apoptosis of tumor cells [45]. Baicalin can inhibit cancer growth by inhibiting the activity of CDC2 kinase and reducing the expression of cyclinB1 and D1 protein [46, 47]. Experimental and clinical studies supported that flavonoids and their synthetic analogues are the promising anti-tumor agents. Thus, as a kind of flavonoids, 8-FOB with potent in vitro anti-tumor action as shown in our present study could be considered as an anti-tumor agent. Further in vivo investigation conducted in animals should be carried out to verify the efficacy of 8-FOB in the treatment of cancers.

Induction of cytotoxicity in tumor cells is a major effective strategy for developing anti-tumor drugs. In vitro pharmacological actions of anti-tumor drugs are usually characterized by the cytotoxic effects that are indicated by inhibiting cell viability, suppressing cell migration and invasion, disrupting mitochondrial function, eliciting intracellular ROS production, and inducing apoptosis. We used these cytotoxic indicators to assess 8-FOB efficacy as an anti-tumor agents. First, we found that 8-FOB shows a more potent effect in suppressing cell viability in CNE-1 cells than in other types of cancer cells. The cytotoxic effects of 8-FOB are time- and dose-dependent and are comparable with the cisplatin treatment. Second, we demonstrated that 8-FOB treatment effectively inhibits cell migration and invasion of malignant behaviors in cancer cells. Since cell migration and invasion is a pivotal process for cancer metastasis, it is worthy of exploring the effect of 8-FOB treatment on cancer metastasis in vivo. Third, it was found that 8-FOB treatment increases intracellular ROS production, impairs mitochondrial function, results in DNA damage, and hence induces apoptosis. These cytotoxic events may be responsible for the mechanism of anti-tumor action. Finally, it could be speculated that elevated ROS production after 8-FOB treatment plays a crucial role in cytotoxic effects of 8-FOB treatment since NAC, a well-defined intracellular ROS scavenger, efficiently preserves cell viability reduction, reduces intracellular ROS level, and antagonizes apoptosis. It has been generally accepted that apoptosis can effectively prevent the development of cancer, and evading apoptosis is an important feature of resistance to drug therapy in many cancers [48]. Therefore, developing apoptosis-inducing drugs is currently an effective strategy to treat cancers. Our study experimentally demonstrated 8-FOB is a potent apoptosis-inducing agent in tumor cells. Furthermore, in evaluating 8-FOB safety by oral administration, mice with 8-FOB given intra-gastric administration at relatively high dose showed no significant changes in hematological, and biochemical indexes in peripheral blood. No histopathological changes were observed in liver and kidney. These findings suggested oral 8-FOB administration is relatively safe and has no obvious side effects in vivo.

Considering our results as well as other previous research results, we speculated that 8-FOB could induce the apoptosis of CNE-1 cells through accumulation of ROS, which leads to mitochondrial dysfunction. Then, we measured indicators related to oxidative stress. The results of this study showed that 8-FOB cause a significant increase in ROS production in tumor cells. At the same time, MMP and ATP production markedly declined. 8-OHdG is the main product of ROS attacking DNA. It is used as a biomarker for quantitative assessment of DNA oxidative damage [49]. In order to explore whether the increase in ROS production mediates the DNA damage response, we measured the changes in 8-OHdG levels. The results showed that 8-OHdG also increased in a concentration-dependent manner. In addition, 8-FOB did not show obvious in vivo side effects in mice. Based on the above results of our research, 8-FOB appears to be a safe and effective candidate as a bioactive phytochemical agent with the potential for the treatment of cancers. There exist some limitations in our present study. Our current study is limited to in vitro study of six types of tumor cells. Preliminary results from these cells could provide some clues to further our effort in assessment of the anti-tumor efficacy of 8-FOB treatment. In vivo anti-tumor efficacy of 8-FOB treatment needs to be verified in mouse xenograft tumor model in the future. Furthermore, whether 8-FOB treatment results in toxic effects in the body needs further assessments in experimental animal models. A clear understanding of 8-FOB toxicity is of importance for its safe clinical use.

Conclusions

Our present study demonstrated that 8-FOB has the anti-tumor effects in six types of cancer cells. The anti-tumor effects are characterized by the suppression of cell viability, inhibition of migration and invasion, and induction of apoptosis. Elevating intracellular ROS production, impairing mitochondrial function, and damaging DNA are responsible for the anti-tumor pharmacological actions. 8-FOB as a naturally existed flavonoids is worthy of further investigation for developing anti-tumor drugs. The in vivo efficacy of anti-tumor action and its molecular mechanisms need further studies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr H-F Pi for his constructive advice on experiment design, Dr C.-H. Chen for his instruction on statistical analysis, and Dr Lei Zhang for her help in biochemical analysis.

Contributor Information

Ya-jing Zhang, Medical College, Guangxi University, 100 University East Road, Xixiangtang District, Nanning, Guangxi, 530004, P. R. China.

Zhen-lin Mu, Medical College, Guangxi University, 100 University East Road, Xixiangtang District, Nanning, Guangxi, 530004, P. R. China.

Ping Deng, Department of Occupational Health, Third Military Medical University, 30 Gaotanyan Zhengjie, Shapingba District, Chongqing, 400038, P. R. China.

Yi-dan Liang, Medical College, Guangxi University, 100 University East Road, Xixiangtang District, Nanning, Guangxi, 530004, P. R. China.

Li-chuan Wu, Medical College, Guangxi University, 100 University East Road, Xixiangtang District, Nanning, Guangxi, 530004, P. R. China.

Ling-ling Yang, Department of Occupational Health, Third Military Medical University, 30 Gaotanyan Zhengjie, Shapingba District, Chongqing, 400038, P. R. China.

Zhou Zhou, Department of Environmental Medicine, and Department of Emergency Medicine of the First Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang University, 866 Yuhangtang Road, Xihu District, Hangzhou, Zhejiang, 310000, P. R. China.

Zheng-ping Yu, Medical College, Guangxi University, 100 University East Road, Xixiangtang District, Nanning, Guangxi, 530004, P. R. China.

Authors’ contributions

Y.J.Z., Z.L.M., P.D., Y.D.L., L.C.W., and L.L.Y. initiated the project with guidance from Z.Z. and Z.P.Y. All experiments were performed by Y.J.Z., Z.L.M., P.D., Y.D.L., and L.L.Y. Y.J.Z., Z.Z., and L.C.W. contributed to the analysis and interpretation of the data. Y.J.Z. and P.D. prepared the figures and wrote the manuscript. Z.P.Y. and Z.Z. conducted critical revision of the manuscript and approval of the article. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81872596), and Open Grants from Key Laboratory of Electromagnetic Radiation Protection, Ministry of Education, China (No. 2017DCKF005).

References

- 1. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin 2015;65:5–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL et al. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin 2015;65:87–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. McDermott AL, Dutt SN, Watkinson JC. The aetiology of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci 2001;26:82–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wei WI. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Lancet 2005;365:2041–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chua MLK, Wee JTS, Hui EP et al. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Lancet 2016;387:1012–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Akbas U, Koksal C, Kesen ND et al. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma radiotherapy with hybrid technique. Med Dosim 2019;44:251–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Turati F, Bravi F, Polesel J et al. Adherence to the Mediterranean diet and nasopharyngeal cancer risk in Italy. Cancer Causes Control 2017;28:89–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lee AW, Sze WM, Au JS et al. Treatment results for nasopharyngeal carcinoma in the modern era: the Hong Kong experience. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2005;61:1107–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cosmopoulos K, Pegtel M, Hawkins J et al. Comprehensive profiling of Epstein-Barr virus microRNAs in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. J Virol 2009;83:2357–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chen SJ, Chen GH, Chen YH et al. Characterization of Epstein-Barr virus miRNAome in nasopharyngeal carcinoma by deep sequencing. PLoS One 2010;5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zhang L, Chen QY, Liu H et al. Emerging treatment options for nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Drug Des Devel Ther 2013;7:37–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Yao K, Shao J, Zhou K et al. Grape seed proanthocyanidins induce apoptosis through the mitochondrial pathway in nasopharyngeal carcinoma CNE-2 cells. Oncol Rep 2016;36:771–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. D'Andrea G. Quercetin: A flavonol with multifaceted therapeutic applications? Fitoterapia 2015;106:256–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cirmi S, Ferlazzo N, Lombardo GE et al. Chemopreventive agents and inhibitors of cancer hallmarks: may citrus offer new perspectives? Nutrients 2016;8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cao Y, DePinho RA, Ernst M et al. Cancer research: past, present and future. Nat Rev Cancer 2011;11:749–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Luo X, Yu X, Liu S et al. The role of targeting kinase activity by natural products in cancer chemoprevention and chemotherapy (Review). Oncol Rep 2015;34:547–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chen MH, Chen XJ, Wang M et al. Ophiopogon japonicus--a phytochemical, ethnomedicinal and pharmacological review. J Ethnopharmacol 2016;181:193–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zhao JW, Chen DS, Deng CS et al. Evaluation of anti-inflammatory activity of compounds isolated from the rhizome of Ophiopogon japonicas. BMC Complement Altern Med 2017;17:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zhou CX, Zou L, Mo JX et al. Homoisoflavonoids from Ophiopogon japonicus. Helvetica Chimica Acta 2013;96:1397–405. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sato H, Shibata M, Shimizu T et al. Differential cellular localization of antioxidant enzymes in the trigeminal ganglion. Neuroscience 2013;248:345–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Navarro-Yepes J, Zavala-Flores L, Anandhan A et al. Antioxidant gene therapy against neuronal cell death. Pharmacol Ther 2014;142:206–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Poli G, Leonarduzzi G, Biasi F et al. Oxidative stress and cell signalling. Curr Med Chem 2004;11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Valko M, Izakovic M, Mazur M et al. Role of oxygen radicals in DNA damage and cancer incidence. Mol Cell Biochem 2004;266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tong L, Chuang C-C, Wu S et al. Reactive oxygen species in redox cancer therapy. Cancer Lett 2015;367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Li JJ, Tang Q, Li Y et al. Role of oxidative stress in the apoptosis of hepatocellular carcinoma induced by combination of arsenic trioxide and ascorbic acid. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2006;27:1078–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zhang D, Liu J, Gao J et al. Zinc supplementation protects against cadmium accumulation and cytotoxicity in Madin-Darby bovine kidney cells. PLoS One 2014;9:e103427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fraga CG, Shigenaga MK, Park JW et al. Oxidative damage to DNA during aging: 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine in rat organ DNA and urine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1990;87:4533–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pi H, Li M, Xie J et al. Transcription factor E3 protects against cadmium-induced apoptosis by maintaining the lysosomal-mitochondrial axis but not autophagic flux in Neuro-2a cells. Toxicol Lett 2018;295:335–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Blaser H, Dostert C, Mak TW et al. TNF and ROS crosstalk in inflammation. Trends Cell Biol 2016;26:249–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Qian JY, Deng P, Liang YD et al. 8-Formylophiopogonanone B antagonizes paraquat-induced hepatotoxicity by suppressing oxidative stress. Front Pharmacol 2019;10:1283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zhao M, Howard E W, Guo Z et al. p53 pathway determines the cellular response to alcohol-induced DNA damage in MCF-7 breast cancer cells. PLoS One 2017; 12: e0175121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Moldeus P, Cotgreave IA. N-acetylcysteine. Methods Enzymol 1994;234:482–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gurer H, Ozgunes H, Neal R et al. Antioxidant effects of N-acetylcysteine and succimer in red blood cells from lead-exposed rats. Toxicology 1998;128:181–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Aruoma OI, Halliwell B, Hoey BM et al. The antioxidant action of N-acetylcysteine: its reaction with hydrogen peroxide, hydroxyl radical, superoxide, and hypochlorous acid. Free Radic Biol Med 1989;6:593–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM et al. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin 2011;61:69–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I et al. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2018;68:394–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ranjan A, Ramachandran S, Gupta N et al. Role of Phytochemicals in Cancer Prevention. Int J Mol Sci 2019;20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Butler MS. Natural products to drugs: natural product-derived compounds in clinical trials. Nat Prod Rep 2008;25:475–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Neuhouser ML. Dietary flavonoids and cancer risk: evidence from human population studies. Nutr Cancer 2004;50:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ahmadi A, Shadboorestan A, Nabavi SF et al. The role of hesperidin in cell signal transduction pathway for the prevention or treatment of cancer. Curr Med Chem 2015;22:3462–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lin TS, Ruppert AS, Johnson AJ et al. Phase II study of flavopiridol in relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukemia demonstrating high response rates in genetically high-risk disease. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:6012–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lazarevic B, Boezelijn G, Diep LM et al. Efficacy and safety of short-term genistein intervention in patients with localized prostate cancer prior to radical prostatectomy: a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind Phase 2 clinical trial. Nutr Cancer 2011;63:889–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Beutler JA, Hamel E, Vlietinck AJ et al. Structure-activity requirements for flavone cytotoxicity and binding to tubulin. J Med Chem 1998;41:2333–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kuntz S, Wenzel U, Daniel H. Comparative analysis of the effects of flavonoids on proliferation, cytotoxicity, and apoptosis in human colon cancer cell lines. Eur J Nutr 1999;38:133–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Zhang J, Wu D, Vikash et al. Hesperetin induces the apoptosis of gastric cancer cells via activating mitochondrial pathway by increasing reactive oxygen species. Dig Dis Sci 2015; 60: 2985–2995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Chao JI, Su WC, Liu HF. Baicalein induces cancer cell death and proliferation retardation by the inhibition of CDC2 kinase and survivin associated with opposite role of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase and AKT. Mol Cancer Ther 2007;6:3039–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Wu JY, Tsai KW, Li YZ et al. Anti-bladder-tumor effect of baicalein from scutellaria baicalensis georgi and its application in vivo. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2013;2013:579751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kelly GL. The essential role of evasion from cell death in cancer. Adv Cancer Res 2011;111:39–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Li J, Lu S, Liu G et al. Co-exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, benzene and toluene and their dose-effects on oxidative stress damage in kindergarten-aged children in Guangzhou, China. Sci Total Environ 2015;524-525:74–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.