Abstract

Objectives

Parents often provide advice to their adult children during their everyday interactions. This study investigated young adult children’s daily experiences with parental advice in U.S. families. Specifically, the study examined how receiving advice and evaluations of parental advice were associated with children’s life problems, parent–child relationship quality, and daily mood.

Methods

Young adult children (aged 18–30 years; participant N = 152) reported whether they received any advice and perceived any unwanted advice from each parent (parent N = 235) for 7 days using a daily diary design (participant-day N = 948). Adult children also reported their positive and negative mood on each interview day.

Results

Results from multilevel models revealed that adult children who reported a more positive relationship with their parents were more likely to receive advice from the parent, whereas adult children who had a more strained relationship with their parents were more likely to perceive advice from the parent as unwanted. Receiving advice from the mother was associated with increased positive mood, whereas unwanted advice from any parent was associated with increased negative mood. Furthermore, the link between unwanted advice and negative mood varied by children’s life problems and parent–child relationship quality.

Discussion

Indeed, parental advice is not “the more the better,” especially when the advice is unsolicited. This study highlights the importance of perceptions of family support for emerging adults’ well-being.

Keywords: Emerging adulthood, Intergenerational relations, Life events and contexts, Well-being

Adult children often receive advice from their parents (Antonucci, 2001; Cooney & Uhlenberg, 1992; Fingerman et al., 2009). Parental advice, as one type of informational support, occurs more frequently than tangible support, such as giving or loaning money and helping with housework because advice can occur via multiple methods, including face-to-face interactions, phone calls, text messaging, and e-mail (Fingerman, Cheng, Tighe et al., 2012). However, children’s desire for support and the support received from parents are not always complementary. Although parents may not intend to give unwanted advice, children often perceive advice from their parents as annoying, uninvited, and unhelpful. For example, children may not feel comfortable when their parents suggest how they should conduct their lives or when their parents tell them how to spend their time (Smith & Goodnow, 1999).

Many factors motivate parents to provide advice to their adult children, including the importance of parent–child ties and children’s life difficulties (Fingerman et al., 2009). These factors shape children’s perceptions of received advice, such that children in the midst of life problems experience conflicted feelings toward parental support (Fingerman et al., 2013). Unsolicited parental advice may be regarded as intrusive and unwelcome among adult children, especially in Western cultures that emphasize independence and individualism (Feng & Feng, 2013). However, we know little about how often adult children receive parental advice and how adult children evaluate the advice received from their parents. Finally, little is known about the implications of parental advice for children’s emotional well-being, especially on a daily basis.

Using daily diary data from young adult children, this study focused on one type of social support—parental advice. We contributed to the scientific literature on parent–child relationships by examining (a) whether daily advice received from parents and evaluations of parental advice were associated with children’s life problems and parent–child relationship quality and (b) whether the receipt and evaluation of parental advice had implications for young adult children’s daily mood. We further examined whether the association between adult children’s daily experiences with parental advice and mood was moderated by young adult children’s life problems and parent–child relationship quality.

Adult Children’s Experience With Parental Advice

Research documented changes in the life experiences that define what it means to be a young adult (i.e., late teens and 20s); scholars refer to this period of time as a “transition to adulthood” or “emerging adulthood” (Arnett, 2000; Furstenberg, 2010). Young adults face increasing challenges to gain a foothold in the adult world, including completing their education, obtaining jobs, and successfully negotiating romantic relationships (Furstenberg, 2010). Thus, parents often help their emerging adult offspring transition into adulthood by offering support, including advice (Carlson, 2014; Fingerman, Cheng, Wesselmann et al., 2012). In this study, we are interested in factors eliciting parental advice and under what circumstances parental advice was perceived as unwanted. We investigated whether the receipt and evaluation of parental advice were conditioned by young adult children’s personal life problems and parent–child relationship quality.

Personal Life Problems

Adult children’s life problems shape their experiences with parental advice. According to contingency theory, family members’ needs elicit support from other members (Eggebeen & Davey, 1998; Silverstein et al., 2006) and parents usually mobilize and allocate resources to provide help to their children who have greater needs. Emerging adult children may experience problems relating to unemployment or divorce, which prompt parental support, including advice (Furstenberg, 2010). In response to offspring’s life problems, parents often provide support to help them overcome the difficulty (Fingerman et al., 2009), even though parents tend to have more conflicts with the child suffering problems (Birditt et al., 2010, 2016). During times of uncertainty, adult children also actively turn to their parents for advice and involve parents in their decision-making process (Cooney & Uhlenberg, 1992).

Adult children’s life problems may also have influenced how children evaluate the parental advice they receive. As conceived by Relational Regulation Theory (RRT), stressors affected both the support provider and the receiver’s perception of the support exchanged (Brock & Lawrence, 2014; Lakey & Orehek, 2011). Studies have examined how perceptions of providing support vary when the provider or the receiver is experiencing difficulties (Bangerter et al., 2018). Yet, there remains a lack of knowledge about the perceptions of receiving support in the context of the support receiver’s life situation. Adult children’s life problems may be acute stressors (e.g., involved in a crime) or chronic stressors (e.g., health problems). When young adult children are experiencing life problems, they may be less likely to appreciate their parent’s advice because such advice may imply the adult child is incompetent and incapable of solving their own problems (Bolger et al., 2000; Smith & Goodnow, 1999). Thus, we expected that adult children who experienced life problems were more likely to receive advice and perceive parental advice as unwanted (Hypothesis 1a).

Parent–Child Relationship Quality

Parental advice is received in the context of the affection and conflict present in the parent–child relationship. According to Intergenerational Solidarity Theory, relationships between parents and children are multidimensional (e.g., structural, functional, affectional, and normative) and positive features of relationships often co-occur (Bengtson & Roberts, 1991; Rossi & Rossi, 1990; Silverstein et al., 1995). Intergenerational Solidarity Theory emphasizes affection and cohesiveness between parents and children as “one of the most important motivations for exchange and contact with older parents” (Silverstein et al., 1995, p. 466). Adult children, therefore, are expected to receive more advice when their relationships with parents are more positive and less negative.

Adult children’s evaluation of parental advice may be related to the overall quality of the relationship (Guntzviller et al., 2017). As RRT posited, the characteristics of the relationship between the support provider and receiver influence the support receiver’s appraisals of the support received (Lakey & Orehek, 2011). Moreover, the receiver interprets social partner’s support behavior in the context of relationship quality (Branje et al., 2002; Reis et al., 2000). One study found that individuals tended to give more unsolicited advice to close friends than to distant friends, in part because discussions with close friends about their problems are more likely to be interpreted as a request for support (Feng & Magen, 2016). However, no study investigated the association between parent–child relationship quality and the evaluation of parental advice from the adult child’s perspective. We hypothesized that adult children with better relationship quality with their parents were more likely to receive advice from parents and less likely to perceive parental advice as unwanted (Hypothesis 1b).

Implications of Parental Advice for Children’s Well-Being

Children often need parents’ support in adulthood, and many perceive receiving parental support as normative and beneficial (Arnett, 2000; Fingerman, Cheng, Tighe et al., 2012). Theory and extensive studies documented the health and well-being benefits of receiving social support, especially from significant others (Uchino, 2009). Adult children who received intensive parental support reported better well-being than peers who did not receive intense support from parents (Fingerman, Cheng, Wesselmann et al., 2012). Thus, we expected that adult children would have a better mood (i.e., higher levels of positive mood and lower levels of negative mood) on days when they received advice from parents, compared to days when they did not receive parental advice (Hypothesis 2a).

However, the perception of unsolicited support is emotionally unpleasant or unhelpful because it may imply the support recipient is incompetent (Feng & MacGeorge, 2006; Smith & Goodnow, 1999). The support receiver may have felt a lack of control over the received support and perceive the support provider does not really pay attention to his or her needs. Moreover, adult children, especially younger ones, may perceive parental advice as nagging and intrusive rather than supportive when they thrive to be independent. The imbalance between desired and received support may have negative implications for the relationship between the support receiver and provider, yielding unintended poor outcomes (Reynolds & Perrin, 2004; Wolff et al., 2013). The over-provision of support from family members may be regarded as “too much of a good thing” and has negative consequences for support receivers’ well-being (Brock & Lawrence, 2009; Silverstein et al., 1996). Thus, we expected that adult children would have worse mood (i.e., lower levels of positive mood and higher levels of negative mood) on days when they perceived unwanted advice from parents, compared to days when they did not perceive unwanted advice (Hypothesis 2b).

As RRT further posited, life problems and the quality of relationship may provide a context for better understanding the consequences of support for individual’s well-being (Lakey et al., 2008). Struggling with life problems or having strained relationships with parents may cause adult children to focus more on their distressing situations and thus they may benefit less from the receipt of advice. Moreover, life problems and poor relationship quality may exacerbate children’s negative responses to the perceived unsolicited advice. Thus, we expected the association between receiving parental advice and daily positive mood would be weaker for adult children with life problems and for those with poorer parent–child relationship quality (Hypothesis 3a); the association between perceiving unwanted parental advice and daily negative mood would be stronger for adult children with life problems and for those with poorer parent–child relationship quality (Hypothesis 3b).

The Current Study

Using a daily diary research design, the current study examined young adult children’s daily experience of parental advice (i.e., the receipt of parental advice and the evaluation of such advice) as a function of children’s life problems and parent–child relationship quality. Furthermore, we examined the implications of daily parental advice for adult children’s daily mood. Finally, we investigated whether the associations of the receipt and evaluation of parental advice with children’s daily mood varied by children’s life problems and parent–child relationship quality. Literature has documented the distinctiveness of relations with father and mother for emerging adult offspring (Aquilino, 2006) and young adults respond differently to advice from their father and mother (Carlson, 2014). Thus, we considered young adult children’s daily experience with advice from father and mother separately.

Method

Sample

This study used offspring data from the Family Exchanges Study (FES, Wave 2; Fingerman, 2013). The FES original sample consisted of 633 middle-aged adults (aged 40–60), who were residents of the Philadelphia Metropolitan Area in 2008. To be in the study, participants had to have at least one child older than age 18 and one living parent. The study identified potential participants via listed samples from Genesys Corporation supplemented with random digit dialing within the Philadelphia Primary Metropolitan Statistical Area. Participants provided information regarding their relationships with each parent and grown offspring in the main survey. At the end of the interviews, participants provided contact information for up to three grown children and 75% of those grown children participated (n = 592) in the offspring survey.

In 2013, 455 participants of the original offspring sample and 285 newly recruited offspring participants completed the main interview for the second wave of FES (overall response rate = 59.8%). The second wave of FES invited participants to participate in a daily diary survey and 230 of offspring participants completed the daily diary survey for up to 7 days. In order to capture the experience of young adulthood, we only included offspring participants aged 18–30 in this study (n = 159). After excluding seven offspring participants who had missing information on life problems, the current study analyzed data provided by 152 offspring participants (i.e., young adult children) from 119 families, who provided information about individual and relational characteristics for each of living parents (N = 235; 118 fathers and 117 mothers), along with their interactions with each parent on each interview day (N = 948).

Daily Diary Measures

Daily parental advice

We assessed whether adult children received any advice from each parent by asking “Did your mother/father give you advice or information since (this time/we spoke) yesterday, that is helping with a decision or giving suggestions about things you could do.” In addition to received advice, adult children provided separate reports of unwanted advice from each parent, by asking “Since (this time/we spoke) yesterday, did your mother/father give you unwanted advice?” Answers to both questions were coded dichotomously as 1 = yes and 0 = no.

Daily mood

Adult children rated the extent to which they experienced six positive emotions (e.g., happy, determined, and calm) and nine negative emotions (e.g., lonely, nervous, and distressed) from 1 (none of the day) to 5 (all of the day; Watson et al., 1988). We calculated mean scores for daily positive mood (α = .74) and negative mood (α = .84), respectively.

Main Interview Measures

Life problems

Middle-aged parents reported each adult child’s life problems experienced in the past 2 years using a measure adapted from the Midlife in the United States study (Greenfield & Marks, 2006); offspring’s own reports on their life problems were not available to us. The life problem dimensions tapped in this measure included developmental disability, physical disability, serious health problem or injury, emotional or psychological problem, drinking or drug problem, serious financial problem, death of someone close, trouble with the law or police, victim of a crime, and serious relationship problem. Because of the skewness associated with the number of life problems, we used a dichotomous variable, identifying whether the offspring experienced any life problems (1 = experienced at least one life problem, 0 = did not experience; Birditt et al., 2010).

Relationship quality

We assessed both positive and negative aspects of relationship quality with each parent (Birditt et al., 2010; Umberson, 1992). Positive qualities of the relationship were measured with two items: “How much does he/she make you feel loved and cared for” and “How much does he/she understand you.” Negative relationship quality included two items: “How much does he/she criticize you” and “How much does he/she make demands on you.” Participants rated each item on a 5-point scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (a great deal). The items were averaged to create positive and negative relationship quality scores (α = .62 for positive relationship quality and α = .79 for negative relationship quality).

Control variables

We considered both adult children’s and their parents’ characteristics that may be associated with children’s experience with parental advice (Fingerman, Cheng, Tighe et al., 2012; Fingerman et al., 2015; Greene & Grimsley, 1990; McDowell et al., 2003). Participants provided information about their age, gender (1 = female, 0 = male), years of education, marital status (1 = married or remarried, 0 = not married), and employment status (1 = working, 0 = not working). Because parents’ characteristics may influence children’s evaluations of their parents’ advice, we also considered parent characteristics, including gender (1 = mother, 0 = father), life problems (1 = at least one life problem, 0 = no life problem; same as children’s life problems), years of education, and rating of health (1 = poor to 5 = excellent).

Analytic Strategy

First, to examine adult children’s daily experiences with parental advice (i.e., receiving advice and perceiving unwanted advice from each of the parents) as the outcome, we employed multilevel models. Participants (Level 3) reported whether they received advice and perceived unwanted advice from each parent (Level 2) on each interview day (Level 1); we estimated three-level logistic regression models to handle the nested structure of the data (SAS PROC GLIMMIX). We examined adult children’s life problems (Hypothesis 1a) and positive or negative parent–child relationship quality (Hypothesis 1b) as key predictors in the models. Models also controlled for adult children’s characteristics (i.e., age, gender, education, marital status, and employment status) and parents’ characteristics (i.e., gender, life problems, education, and health).

Next, we estimated two-level regression models (SAS PROC MIXED) for adult children’s daily mood; adult children (Level 2) reported their mood on each interview day (Level 1). Positive and negative mood were used as the outcome measures in separate models. We examined received parental advice (Hypothesis 2a) and perceived unwanted advice (Hypothesis 2b) as the main predictors, controlling for prior day’s parental advice experience and mood status—given the potential lagged effects (Reis, 2012). Most of the young adult children (97%) in our sample reported on both their father and mother; aggregating parental characteristics at the participant level may mask differences in the effects of ties with mother and father. Therefore, we examined the implications of advice from fathers and mothers for children’s daily mood separately. We also controlled for characteristics of adult children (i.e., age, gender, education, marital status, and employment status).

Finally, we introduced interaction terms between daily advice experience and children’s life problems and relationship quality to examine whether the association between parental advice and adult children’s daily mood was moderated by children’s life problems and parent–child relationship quality (Hypothesis 3a and 3b).

Results

We presented descriptive information of adult children and their parents in Table 1. On average, offspring participants completed 6.66 daily interviews over the 7-day diary period. More than half of adult children had experienced at least one life problem (62%), and they generally reported more positive relationships (M = 4.13; SD = 0.79) and less negative relationships with their parents (M = 2.42; SD = 1.03). On average, 62% and 76% of adult children received advice from their fathers and mothers and 16% and 24% of adult children indicated unwanted advice from their fathers and mothers over the interview week, respectively. The correlation between receiving parental advice and perceiving unwanted parental advice was modest (r = .22, p < .001).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Young Adult Children and Their Parents

| Adult offspring (N = 152) | Parents (N = 235) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Fathers (n = 118) | Mothers (n = 117) | ||

| Variables | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) |

| Individual characteristics | |||

| Demographics | |||

| Age | 24.64 (3.06) | 56.64 (4.53) | 53.98 (5.46) |

| Female, % | 58 | — | — |

| Years of education | 13.96 (1.99) | 14.69 (2.01) | 14.90 (1.82) |

| Working, % | 61 | 81 | 77 |

| Married or remarried, % | 16 | 81 | 82 |

| Rating of healtha | 3.63 (1.00) | 3.21 (1.03) | 3.29 (1.10) |

| Both parents living, % | 97 | — | — |

| Life problemsb, % | 62 | 64 | 68 |

| Relationship quality with parents | |||

| Positive relationship qualityc | — | 3.98 (0.93) | 4.28 (0.64) |

| Negative relationship qualityc | — | 2.34 (0.98) | 2.51 (1.04) |

| Daily characteristics | |||

| Receipt of parental advice | |||

| Had experience at least once that week, % | — | 62 | 76 |

| % of days adult children had experience | — | 21 | 31 |

| Perception of unwanted parental advice | |||

| Had experience at least once that week, % | — | 16 | 24 |

| % of days adult children had experience | — | 3 | 6 |

| Daily mood | |||

| Positive moodd | 3.13 (0.64) | — | — |

| Negative moode | 1.34 (0.44) | — | — |

Note: Participant (adult offspring) N = 152; parent N = 235; participant-parent N = 299; participant-day N = 948.

aRated 1 = poor to 5 = excellent.

b1 = Having at least one life problem and 0 = not having life problems.

cMean scores of two items rated 1 = not at all to 5 = a great deal.

dMean scores of six items rated 1 = none of the day to 5 = all of the day.

eMean scores of nine items rated 1 = none of the day to 5 = all of the day.

Regarding adult children’s daily experience of parental advice (Table 2), multilevel models revealed that children’s life problems were not significantly associated with their receipt or evaluation of parental advice (Hypothesis 1a). Next, for parent–child relationship quality (Hypothesis 1b), young adult children who had more positive relationship quality with parents were more likely to receive advice from the parent (B = 0.57, p < .001 in Model 1). Moreover, young adult children who reported more negative relationships with their parents were more likely to perceive the advice from the parent as unwanted (B = 0.50, p < .001 in Model 4).

Table 2.

Multilevel Logistic Regression Models for Young Adult Children’s Daily Experience With Parental Advice

| Variables | Received parental advice | Perceived unwanted parental advice | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |||||||||

| B | (SE) | Prob. | B | (SE) | Prob. | B | (SE) | Prob. | B | (SE) | Prob. | |

| Fixed effects | ||||||||||||

| Intercept | −2.94*** | (0.86) | .05 | −3.39*** | (0.87) | .03 | −4.15** | (1.51) | .02 | −3.94** | (1.47) | .02 |

| Life problemsa | 0.07 | (0.23) | .52 | 0.03 | (0.24) | .51 | 0.64 | (0.36) | .66 | 0.43 | (0.36) | .61 |

| Positive relationship qualityb | 0.57*** | (0.14) | .64 | — | — | — | 0.12 | (0.21) | .53 | — | — | — |

| Negative relationship qualityb | — | — | — | 0.18 | (0.09) | .54 | — | — | — | 0.50*** | (0.14) | .62 |

| Covariates | ||||||||||||

| Age | −0.04 | (0.04) | .49 | −0.05 | (0.04) | .49 | −0.05 | (0.06) | .49 | −0.06 | (0.06) | .48 |

| Female | −0.41 | (0.22) | .40 | −0.31 | (0.22) | .42 | −0.11 | (0.33) | .47 | −0.03 | (0.33) | .49 |

| Years of education | −0.12 | (0.06) | .47 | −0.07 | (0.06) | .48 | −0.34*** | (0.10) | .42 | −0.29** | (0.10) | .43 |

| Married or remarried | −0.32 | (0.32) | .42 | −0.18 | (0.33) | .46 | −0.18 | (0.51) | .45 | 0.00 | (0.51) | .50 |

| Working | 0.13 | (0.24) | .53 | 0.13 | (0.25) | .53 | 0.36 | (0.38) | .59 | 0.41 | (0.37) | .60 |

| Parent: Mother | 0.50*** | (0.14) | .62 | 0.61*** | (0.14) | .65 | 0.54 | (0.28) | .63 | 0.48 | (0.27) | .62 |

| Parent: Life problemsa | 0.35 | (0.19) | .59 | 0.37 | (0.20) | .59 | −0.08 | (0.34) | .48 | −0.03 | (0.34) | .49 |

| Parent: Years of education | 0.05 | (0.05) | .51 | 0.06 | (0.05) | .52 | 0.04 | (0.09) | .51 | 0.02 | (0.09) | .50 |

| Parent: Rating of healthc | 0.23* | (0.09) | .56 | 0.28** | (0.09) | .57 | −0.17 | (0.15) | .46 | −0.16 | (0.14) | .46 |

| Random effects | ||||||||||||

| Intercept VAR (Level 2: parent) | 0.34* | (0.15) | — | 0.37* | (0.15) | — | 0.67 | (0.39) | — | 0.47 | (0.38) | — |

| Intercept VAR (Level 3: participant) | 0.93*** | (0.21) | — | 0.99*** | (0.24) | — | 0.89* | (0.45) | — | 0.89* | (0.43) | — |

| −2 (pseudo) Log-likelihood | 8,650.89 | 8,617.36 | 10,903.62 | 11,067.08 |

Note: Participant (adult offspring) N = 152; parent N = 235; participant-parent N = 299; participant-day N = 948. VAR = variance.

a1 = Having at least one life problem and 0 = not having life problems.

b Mean scores of two items rated 1 = not at all to 5 = a great deal.

cRated 1 = poor to 5 = excellent.

*p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Next, we examined the associations between adult children’s experience of parental advice and their daily mood (Hypothesis 2a and 2b). Multilevel models for positive mood (Table 3) showed that receiving advice from mother was associated with higher levels of positive mood (B = 0.09, p < .05 in Model 3), whereas receiving advice from father or perceiving unwanted advice from parents was not significantly associated with children’s positive mood. For negative mood (Table 4), perceiving unwanted advice from father or mother was associated with higher levels of negative mood (B = 0.18, p < .01 in Model 2; B = 0.13, p < .05 in Model 4), whereas receiving parental advice was not significantly associated with adult children’s negative mood.

Table 3.

Multilevel Regression Models for Young Adult Children’s Daily Positive Mood

| Variables | Positive mood by advice from fathers | Positive mood by advice from mothers | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |||||

| B | (SE) | B | (SE) | B | (SE) | B | (SE) | |

| Fixed effects | ||||||||

| Intercept | 1.86*** | (0.12) | 1.87*** | (0.12) | 2.00*** | (0.12) | 2.03*** | (0.13) |

| Received advicea | 0.05 | (0.05) | — | — | 0.09* | (0.04) | — | — |

| Perceived unwanted adviceb | — | — | −0.07 | (0.09) | — | — | −0.07 | (0.08) |

| Covariates | ||||||||

| Prior day: Received advicea | 0.01 | (0.04) | — | — | −0.02 | (0.04) | — | — |

| Prior day: Perceived unwanted adviceb | — | — | 0.13 | (0.10) | — | — | 0.05 | (0.07) |

| Prior day: Positive moodc | 0.40*** | (0.03) | 0.40*** | (0.03) | 0.35*** | (0.03) | 0.35*** | (0.03) |

| Life problemsd | −0.16** | (0.06) | −0.17** | (0.06) | −0.15* | (0.06) | −0.15* | (0.06) |

| Positive relationship qualitye | 0.06 | (0.03) | 0.07* | (0.03) | 0.04 | (0.05) | 0.05 | (0.05) |

| Negative relationship qualitye | 0.05 | (0.03) | 0.05 | (0.03) | −0.01 | (0.03) | 0.00 | (0.03) |

| Age | −0.01 | (0.01) | −0.01 | (0.01) | −0.01 | (0.01) | −0.01 | (0.01) |

| Female | 0.11 | (0.06) | 0.10 | (0.06) | 0.09 | (0.06) | 0.08 | (0.06) |

| Years of education | 0.00 | (0.02) | 0.00 | (0.02) | 0.00 | (0.02) | 0.00 | (0.02) |

| Working | 0.09 | (0.06) | 0.09 | (0.06) | 0.07 | (0.07) | 0.08 | (0.07) |

| Married or remarried | 0.04 | (0.08) | 0.03 | (0.08) | 0.01 | (0.09) | 0.01 | (0.09) |

| Random effects | ||||||||

| Intercept VAR (Level 2: participant) | 0.07** | (0.02) | 0.06** | (0.02) | 0.08** | (0.02) | 0.09*** | (0.02) |

| Residual VAR | 0.19*** | (0.01) | 0.19*** | (0.01) | 0.18*** | (0.01) | 0.18*** | (0.01) |

| −2 Log-likelihood | 1,110.1 | 1,105.7 | 1,110.5 | 1,111.6 |

Note: Participant (adult offspring) N = 152; participant-father n = 149 (participant-day n = 772); participant-mother n = 150 (participant-day n = 781). VAR = variance.

a1 = Received any advice on that day and 0 = did not receive.

b1 = Perceived unwanted advice on that day and 0 = did not perceive.

c Mean scores of six items rated 1 = none of the day to 5 = all of the day.

d1 = Having at least one life problem and 0 = not having life problems.

eMean scores of two items rated 1 = not at all to 5 = a great deal.

*p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Table 4.

Multilevel Regression Models for Young Adult Children’s Daily Negative Mood

| Variables | Negative mood by advice from fathers | Negative mood by advice from mothers | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |||||

| B | (SE) | B | (SE) | B | (SE) | B | (SE) | |

| Fixed effects | ||||||||

| Intercept | 0.71*** | (0.06) | 0.71*** | (0.06) | 0.75*** | (0.06) | 0.74*** | (0.06) |

| Received advicea | 0.00 | (0.03) | — | — | −0.01 | (0.03) | — | — |

| Perceived unwanted adviceb | — | — | 0.18** | (0.07) | — | — | 0.13* | (0.06) |

| Covariates | ||||||||

| Prior day: Received advicea | 0.02 | (0.03) | — | — | 0.01 | (0.03) | — | — |

| Prior day: Perceived unwanted adviceb | — | — | −0.01 | (0.07) | — | — | −0.03 | (0.05) |

| Prior day: Negative moodc | 0.41*** | (0.03) | 0.41*** | (0.03) | 0.41*** | (0.03) | 0.42*** | (0.03) |

| Life problemsd | 0.02 | (0.04) | 0.02 | (0.04) | 0.02 | (0.04) | 0.02 | (0.04) |

| Positive relationship qualitye | −0.03 | (0.02) | −0.03 | (0.02) | −0.01 | (0.03) | −0.01 | (0.03) |

| Negative relationship qualitye | 0.04 | (0.02) | 0.03 | (0.02) | 0.03 | (0.02) | 0.02 | (0.02) |

| Age | 0.00 | (0.01) | 0.00 | (0.01) | 0.00 | (0.01) | 0.00 | (0.01) |

| Female | 0.02 | (0.04) | 0.02 | (0.04) | 0.00 | (0.04) | 0.00 | (0.04) |

| Years of education | 0.01 | (0.01) | 0.01 | (0.01) | 0.01 | (0.01) | 0.01 | (0.01) |

| Working | 0.06 | (0.04) | 0.06 | (0.04) | 0.04 | (0.04) | 0.03 | (0.04) |

| Married or remarried | −0.05 | (0.05) | −0.05 | (0.05) | −0.04 | (0.05) | −0.04 | (0.05) |

| Random effects | ||||||||

| Intercept VAR (Level 2: participant) | 0.03** | (0.01) | 0.03** | (0.01) | 0.03** | (0.01) | 0.03** | (0.01) |

| Residual VAR | 0.10*** | (0.01) | 0.10*** | (0.01) | 0.10*** | (0.01) | 0.10*** | (0.01) |

| −2 Log-likelihood | 571.7 | 561.8 | 575.2 | 567.2 |

Note: Participant (adult offspring) N = 152; participant-father n = 149 (participant-day n = 772); participant-mother n = 150 (participant-day n = 781). VAR = variance.

a1 = Received any advice on that day and 0 = did not receive.

b1 = Perceived unwanted advice on that day and 0 = did not perceive.

c Mean scores of nine items rated 1 = none of the day to 5 = all of the day.

d1 = Having at least one life problem and 0 = not having life problems.

e Mean scores of two items rated 1 = not at all to 5 = a great deal.

*p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

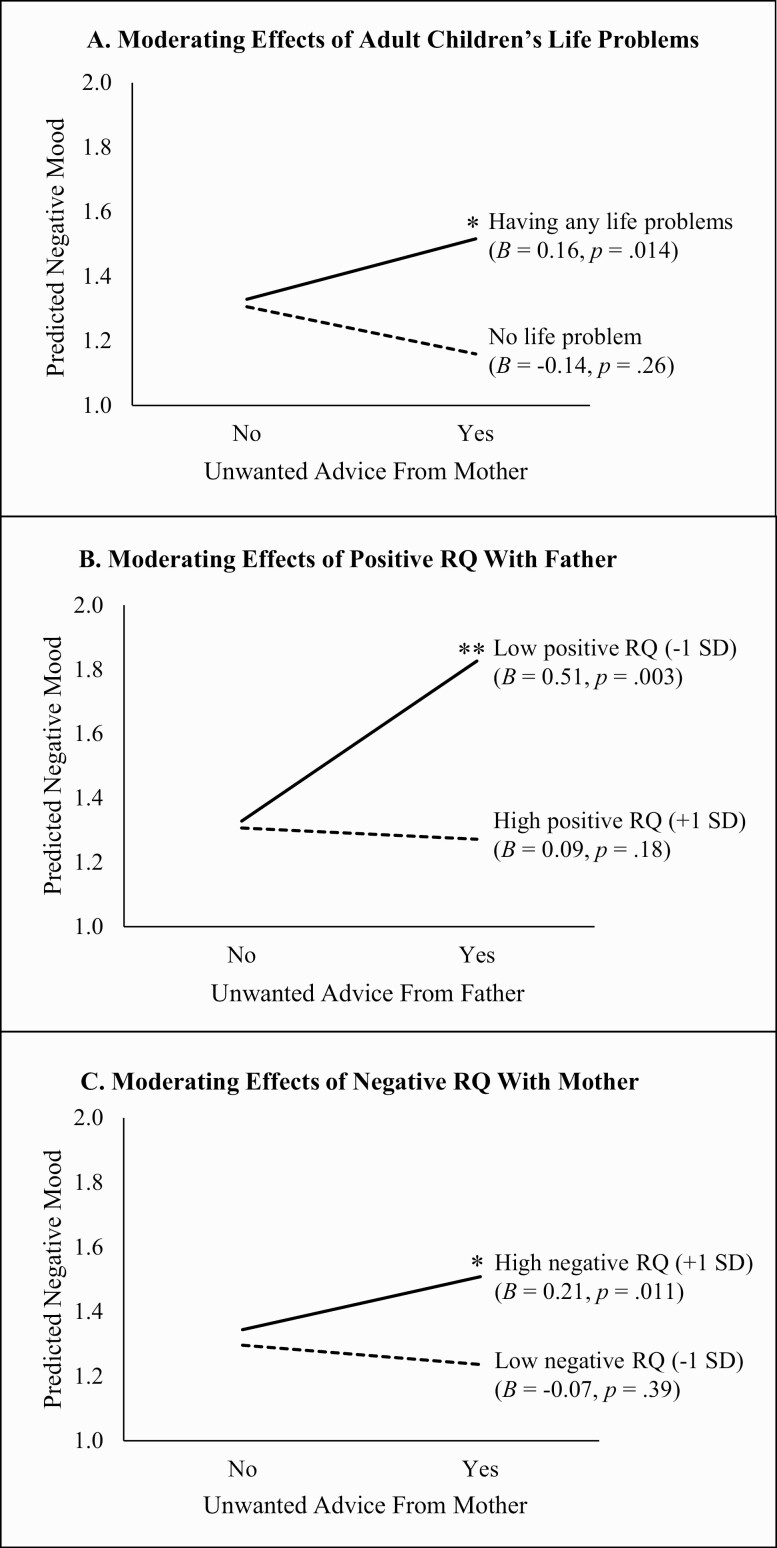

Last, we examined whether the associations between adult children’s experience of parental advice and their daily mood varied by children’s life problems and parent–child relationship quality (Hypothesis 3a and 3b). We found no significant moderation effect of life problems or parent–child relationship quality for the association between parental advice and children’s positive mood (not shown). For children’s negative mood, we found three significant moderation effects of life problems and relationship quality (Supplementary Table 1). First, children’s life problems moderated the association between unwanted advice from mothers and negative mood (interaction term B = 0.31, p = .040). According to the simple slope analyses (Robinson et al., 2013), unwanted advice from mothers was associated with higher levels of negative mood for adult children with life problems (B = 0.16, p = .014), but not for adult children who had no life problems (B = −0.14, p = .26; Figure 1A). Second, positive quality moderated the association between unwanted advice from fathers and negative mood (interaction term B = −0.28, p = .007). Specifically, unwanted advice from fathers was associated with higher levels of negative mood for adult children who had lower levels of positive relationship quality with fathers (B = 0.51, p = .003), but not for children who reported higher levels of positive relationship quality (B = 0.09, p = .18; Figure 1B). Finally, negative parent–child relationship quality moderated the association between unwanted advice from mothers and negative mood (interaction term B = 0.11, p = .027). Thus, unwanted advice from mothers was associated with higher levels of negative mood for adult children who had higher levels of negative relationship quality with mothers (B = 0.21, p = .011); but there was no such significant association for children who reported lower levels of negative relationship quality with mothers (B = –0.07, p = .39; Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

Moderating effects of children’s life problems (A) and parent–child relationship quality (B and C) for the association between unwanted parental advice and daily negative mood. RQ = relationship quality. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Discussion

Adult children receive different types of support from their parents during their emerging adulthood; however, they do not always benefit from such support. Focusing on a particular type of parent support, parental advice, this study contributed to the literature on intergenerational family support by examining young adult children’s receipt of advice and their evaluation of the adequacy of advice from their parents on a daily basis. Moreover, prior studies focused on the amount of family support for family members’ well-being. This study expanded on prior research by examining the appraisal of received parental support and its association with daily mood among adult children. Findings from this study suggested that personal life problems and parent–child relationship quality were important factors in shaping adult children’s experience with parental advice and daily mood.

Receiving and Evaluating Advice From Parents

Within the framework of contingency theory and RRT, this study examined the associations of children’s life problems and parent–child relationship quality with adult children’s experience of parental advice. We found that life problems of adult children were not related to the receipt or evaluation of parental advice. This finding was not consistent with the contingency theory, which argued that children’s needs evoke a response by parents in the form of providing advice. It was probably due to the unique feature of parent-to-adult child advice, in that such advice occurs more often compared to other forms of social support (Fingerman, Cheng, Tighe et al., 2012). Parents may have advised their children on how to deal with problems, how to succeed in their careers, and even how to make choices in everyday life. Thus, unlike other forms of instrumental support, including monetary support, adult children were likely to receive advice from their parents regardless of the children’s achievements or problems.

Although studies demonstrated that offspring in the midst of life problems expressed conflicted feelings regarding parents’ support (Fingerman et al., 2013), we found that having life problems was only marginally significant regarding how children perceived the adequacy of parental advice (B = 0.64, p = .07 in Model 3 of Table 2). It was possible that adult children who encountered life problems may need parental advice to solve their problems, and thus they may not perceive parental advice negatively. Future research should examine how children evaluate the usefulness of parental advice when children were experiencing multiple life problems or were heavily affected by a specific crisis.

Next, we examined links between parental advice and parent–child relationship quality. Results suggested that adult children were more likely to receive advice when they had more positive relationships with their parents. This finding was consistent with Intergenerational Solidarity Theory, such that parents tended to provide more support, including advice, to children to whom they felt closer. Findings suggested that adult children were more likely to perceive advice from parents as unwanted when they had more negative relationships with their parents. This result provided evidence for RRT that relationships between the support receiver and the advice provider affect the receiver’s appraisals of received advice (Lakey & Orehek, 2011). Poor parent–child relationships may not have stopped parents from providing support but rather fostered children’s negative responses to such received support (Fingerman et al., 2013).

Parental Advice and Daily Mood

Social support studies have recognized the importance of received and perceived support for persons’ well-being (Uchino, 2009). This study contributed to the literature by examining how the evaluation of adequacy of parents’ support is associated with adult children’s well-being. In line with the literature on the benefits of receiving social support, we found that receiving advice from mothers was related to better daily mood. However, other studies found nonsignificant or even negative associations between received support and recipients’ subjective well-being (Reinhardt et al., 2006). The discrepancy in support studies may have been due to the failure to include the recipient’s appraisals of received support in the analysis. How individuals evaluated the received support from family members, non-kin, and social partners may have had different consequences for their well-being.

Moreover, we found that life problems of adult children, as well as parent–child relationship quality, moderated the link between daily mood and unwanted parental advice. Strained relationships with parents not only were associated with children’s negative interpretations of parental advice, but also exaggerated young adult children’s negative response to unwanted parental advice. Positive personal relationships make the advice provider more persuasive and the advice recipients were more likely to report better evaluation of received advice (Bonaccio & Dalal, 2006). However, when the child had a poor relationship with parents, parental advice may be communicated in a negative manner. Unwanted advice may even have exaggerated tensions with parents and thus lead to worse mood for adult children.

Adult children suffering life problems reported worse mood on days when they perceived unwanted advice from mothers. One possibility was that fathers and mothers tend to provide different types of advice to their children (McDowell et al., 2003). While fathers provided advice regarding academic or career choices, mothers often provided advice about work–life balance and relationship concerns (Carlson, 2014). Advice from mothers may be perceived as intrusive or nagging by emerging adults. When adult children were exposed to life problems, they were more likely to express negative responses to inadequate support. In addition, adult children in the midst of problems may want to solve their life problems by themselves to show their independence (Smith & Goodnow, 1999). Thus, adult children may have perceived mothers’ advice negatively when they were experiencing difficulties.

Prior studies focused on the implications of actual support exchanges for family members’ well-being, but largely ignored the appraisal aspect of family support (Bianchi et al., 2008). Parents and adult children often engage in intensive support exchanges. Findings of this study call for attention to be paid to family support behaviors that may result in negative responses. Providing support, such as advice, may not have improved the support receiver’s well-being. Rather, family members who perceived inadequate or unwanted advice may have felt distressed in the face of such “good will.”

Limitations and Directions for Future Research

Several limitations were present in this study. First, we measured adult children’s received advice and perceptions of unwanted advice from parents using a one-item scale and specific types of advice were not available. Future research is needed to differentiate various types of parent advice and children’s appraisals regarding each type of advice. Second, the measure of life problems was limited; life problems, specifically pertaining to emerging adults, were not included in the scale, such as education and career development problems. Third, parents’ reports of children’s life problems may contain reporting bias due to parents’ limited knowledge about their offspring’s lives. Finally, more research is needed to examine the potential reciprocal associations between parental advice, parent–child interactions, and children’ mood on a daily basis.

In conclusion, this study contributed to the literature on intergenerational family support by examining how young adult children received and evaluated parental advice in everyday life. The findings suggested that adult children’s daily experience with parental advice should be understood in the context of children’s life problems and parent–child relationship quality. Providing parental advice to adult children was not always characterized as “the more the better.” When the received advice is perceived as “too much of a good thing,” parental advice may become a risk factor for children’s emotional well-being. Family counselors, social workers, and therapists should consider the role of support appraisals in their practice to promote better family relationships and individual well-being.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

Data for this study are available at the National Archive of Computerized Data on Aging (https://www.icpsr.umich.edu/icpsrweb/NACDA/studies/37317).

Funding

This study was supported by grants from the National Institute on Aging (NIA), R01AG027769, Family Exchanges Study II (K. L. Fingerman, principal investigator) and R03AG048879, Generational Family Patterns and Well-Being (K. Kim, principal investigator). This research also was supported by grant 5 R24 HD042849, awarded to the Population Research Center (PRC) at The University of Texas at Austin by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD).

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

References

- Antonucci, T. C. (2001). Social relations: An examination of social networks, social support, and sense of control. In Birren J. E. & Schaie K. W. (Eds.), Handbook of the psychology of aging (5th ed., pp. 427–453). Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Aquilino, W. S. (2006). Family relationships and support systems in emerging adulthood. In Arnett J. J. & Tanner J. L. (Eds.), Emerging adults in America: Coming of age in the 21st century (pp. 193–217). American Psychological Association. doi: 10.1037/11381-008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett, J. J. (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55(5), 469–480. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.55.5.469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bangerter, L. R., Polenick, C. A., Zarit, S. H., & Fingerman, K. L. (2018). Life problems and perceptions of giving support: Implications for aging mothers and middle-aged children. Journal of Family Issues, 39(4), 917–930. doi: 10.1177/0192513X16683987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bengtson, V. L., & Roberts, R. E. (1991). Intergenerational solidarity in aging families: An example of formal theory construction. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 53(4), 856–870. doi: 10.2307/352993 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi, S. M., Hotz, V. J., McGarry, K., & Seltzer, J. A. (2008). Intergenerational ties: Theories, trends, and challenges. In Booth A., Crouter A. C., Bianchi S. M., & Seltzer J. A. (Eds.), Intergenerational caregiving (pp. 3–43). The Urban Institute Press. [Google Scholar]

- Birditt, K. S., Fingerman, K. L., & Zarit, S. H. (2010). Adult children’s problems and successes: Implications for intergenerational ambivalence. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 65(2), 145–153. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbp125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birditt, K. S., Kim, K., Zarit, S. H., Fingerman, K. L., & Loving, T. J. (2016). Daily interactions in the parent–adult child tie: Links between children’s problems and parents’ diurnal cortisol rhythms. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 63, 208–216. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2015.09.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger, N., Zuckerman, A., & Kessler, R. C. (2000). Invisible support and adjustment to stress. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79(6), 953–961. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.79.6.953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonaccio, S., & Dalal, R. S. (2006). Advice taking and decision-making: An integrative literature review, and implications for the organizational sciences. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 101(2), 127–151. doi: 10.1016/j.obhdp.2006.07.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Branje, S. J., van Aken, M. A., & van Lieshout, C. F. (2002). Relational support in families with adolescents. Journal of Family Psychology, 16(3), 351–362. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.16.3.351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brock, R. L., & Lawrence, E. (2009). Too much of a good thing: Underprovision versus overprovision of partner support. Journal of Family Psychology, 23(2), 181–192. doi: 10.1037/a0015402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brock, R. L., & Lawrence, E. (2014). Intrapersonal, interpersonal, and contextual risk factors for overprovision of partner support in marriage. Journal of Family Psychology, 28(1), 54–64. doi: 10.1037/a0035280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson, C. L. (2014). Seeking self-sufficiency: Why emerging adult college students receive and implement parental advice. Emerging Adulthood, 2(4), 257–269. doi: 10.1177/2167696814551785 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cooney, T. M., & Uhlenberg, P. (1992). Support from parents over the life course: The adult child’s perspective. Social Forces, 71(1), 63–84. doi: 10.1093/sf/71.1.63 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eggebeen, D. J., & Davey, A. (1998). Do safety nets work? The role of anticipated help in times of need. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 60(4), 939–950. doi: 10.2307/353636 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feng, B., & Feng, H. (2013). Examining cultural similarities and differences in responses to advice: A comparison of American and Chinese college students. Communication Research, 40(5), 623–644. doi: 10.1177/0093650211433826 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feng, B., & MacGeorge, E. L. (2006). Predicting receptiveness to advice: Characteristics of the problem, the advice-giver, and the recipient. Southern Communication Journal, 71(1), 67–85. doi: 10.1080/10417940500503548 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feng, B., & Magen, E. (2016). Relationship closeness predicts unsolicited advice giving in supportive interactions. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 33(6), 751–767. doi: 10.1177/0265407515592262 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fingerman, K. L. (2013). Family Exchanges Study Wave 2, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 2013. Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor], 2019-07-31. doi: 10.3886/ICPSR37317.v1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fingerman, K. L., Cheng, Y.-P., Cichy, K. E., Birditt, K. S., & Zarit, S. (2013). Help with “strings attached”: Offspring perceptions that middle-aged parents offer conflicted support. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 68(6), 902–911. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbt032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fingerman, K. L., Cheng, Y.-P., Tighe, L., Birditt, K. S., & Zarit, S. (2012). Relationships between young adults and their parents. In Booth A., Brown S. L., Landale N. S., Manning W. D., & McHale S. M. (Eds.), Early adulthood in a family context (pp. 59–85). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Fingerman, K. L., Cheng, Y.-P., Wesselmann, E. D., Zarit, S., Furstenberg, F., & Birditt, K. S. (2012). Helicopter parents and landing pad kids: Intense parental support of grown children. Journal of Marriage and Family, 74(4), 880–896. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2012.00987.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fingerman, K. L., Kim, K., Davis, E. M., Furstenberg, F. F., Jr, Birditt, K. S., & Zarit, S. H. (2015). “I’ll give you the world”: Parental socioeconomic background and assistance to young adult children. Journal of Marriage and Family, 77(4), 844–865. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fingerman, K., Miller, L., Birditt, K., & Zarit, S. (2009). Giving to the good and the needy: Parental support of grown children. Journal of Marriage and Family, 71(5), 1220–1233. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2009.00665.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fingerman, K. L., Pitzer, L. M., Chan, W., Birditt, K., Franks, M. M., & Zarit, S. (2011). Who gets what and why? Help middle-aged adults provide to parents and grown children. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 66(1), 87–98. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbq009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furstenberg, F. F., Jr. (2010). On a new schedule: Transitions to adulthood and family change. Future of Children, 20(1), 67–87. doi: 10.1353/foc.0.0038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene, A. L., & Grimsley, M. D. (1990). Age and gender differences in adolescents’ preferences for parental advice: Mum’s the word. Journal of Adolescent Research, 5(4), 396–413. doi: 10.1177/074355489054002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield, E. A., & Marks, N. F. (2006). Linked lives: Adult children’s problems and their parents’ psychological and relational well-being. Journal of Marriage and Family, 68(2), 442–454. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2006.00263.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guntzviller, L. M., MacGeorge, E. L., & Brinker, D. L., Jr. (2017). Dyadic perspectives on advice between friends: Relational influence, advice quality, and conversation satisfaction. Journal Communication Monographs, 84(4), 488–509. doi: 10.1080/03637751.2017.1352099 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lakey, B., Cohen, J. L., & Neely, L. C. (2008). Perceived support and relational effects in psychotherapy process constructs. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 55(2), 209–220. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.55.2.209 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lakey, B., & Orehek, E. (2011). Relational regulation theory: A new approach to explain the link between perceived social support and mental health. Psychological Review, 118(3), 482–495. doi: 10.1037/a0023477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDowell, D. J., Parke, R. D., & Wang, S. J. (2003). Differences between mothers’ and fathers’ advice-giving style and content: Relations with social competence and psychological functioning in middle childhood. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 49(1), 55–76. doi: 10.1353/mpq.2003.0004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reinhardt, J. P., Boerner, K., & Horowitz, A. (2006). Good to have but not to use: Differential impact of perceived and received support on well-being. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 23(1), 117–129. doi: 10.1177/0265407506060182 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reis, H. T. (2012). Why researchers should think “real world”: A conceptual rationale. In Mehl M. R. & Conner T. S. (Eds.), Handbook of research methods for studying daily life (pp. 3–21). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Reis, H. T., Collins, W. A., & Berscheid, E. (2000). The relationship context of human behavior and development. Psychological Bulletin, 126(6), 844–872. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.6.844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, J. S., & Perrin, N. A. (2004). Mismatches in social support and psychosocial adjustment to breast cancer. Health Psychology, 23(4), 425–430. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.4.425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, C. D., Tomek, S., & Schumacker, R. E. (2013). Tests of moderation effects: Difference in simple slopes versus the interaction term. Multiple Linear Regression Viewpoints, 39(1), 16–24. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi, A. S., & Rossi, P. H. (1990). Of human bonding: Parent–child relations across the life course. Aldine de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein, M., Chen, X., & Heller, K. (1996). Too much of a good thing? Intergenerational social support and the psychological well-being of older parents. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 58(4), 970–982. doi: 10.2307/353984 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein, M., Gans, D., & Yang, F. M. (2006). Intergenerational support to aging parents: The role of norms and needs. Journal of Family Issues, 27(8), 1068–1084. doi: 10.1177/0192513X06288120 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein, M., Parrott, T. A., & Bengtson, V. L. (1995). Factors that predispose middle-aged sons and daughters to provide social support to older parents. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 57(2), 465–475. doi: 10.2307/353699 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J., & Goodnow, J. J. (1999). Unasked-for support and unsolicited advice: Age and the quality of social experience. Psychology and Aging, 14(1), 108–121. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.14.1.108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchino, B. N. (2009). Understanding the links between social support and physical health: A life-span perspective with emphasis on the separability of perceived and received support. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 4(3), 236–255. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6924.2009.01122.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umberson, D. (1992). Relationships between adult children and their parents: Psychological consequences for both generations. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 54(3), 664–674. doi: 10.2307/353252 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(6), 1063–1070. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff, J. K., Schmiedek, F., Brose, A., & Lindenberger, U. (2013). Physical and emotional well-being and the balance of needed and received emotional support: Age differences in a daily diary study. Social Science and Medicine, 91, 67–75. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.04.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.