Abstract

Objectives: This study explores the heterogeneity in effects of the 2014 Affordable Care Act (ACA) Medicaid expansions on insurance coverage, health care access, and health status of low-income women with dependent children by pre-expansion state-level income eligibility.

Materials and Methods: We employ a quasiexperimental difference-in-differences design comparing outcome changes in Medicaid expansion states to nonexpansion states. We estimate effects separately for three groups of expansion states based on pre-expansion (2013) parent income eligibility: low pre-expansion eligibility (<90% of federal poverty level [FPL]), high eligibility (90% to <138% FPL), and full eligibility (≥138% FPL). Study samples include women with dependent children below 138% FPL from the 2011 to 2018 American Community Survey for the insurance outcomes, and from the 2011 to 2018 Behavioral Risk Surveillance System for the access and health outcomes.

Results: There is stark heterogeneity in changes of health insurance and health care access by pre-expansion income eligibility levels. In comparison to Medicaid non-expansion states, there are large increases in insured rate (9 percentage-points) and Medicaid coverage (16 percentage-points) in expansion states with low pre-expansion eligibility. Insurance changes are much smaller in states with high or full pre-expansion eligibility. Changes in access largely mirror those in coverage. There are no significant changes in health status regardless of pre-expansion eligibility.

Conclusions: The ACA Medicaid expansions increased coverage and access for low-income women with dependent children primarily in states with low pre-expansion parent eligibility, and therefore, reduced differences in these outcomes between expansion states.

Keywords: maternal health, Medicaid expansion, health care reform

Introduction

In March 2010, the federal government passed the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) to increase health coverage and access. One of the key provisions is that states can expand Medicaid for individuals with income below 138% of the federal poverty level (FPL). Twenty-six states plus Washington, D.C. expanded Medicaid in 2014, and 11 more states have expanded by January 2020.1

There is strong evidence that the Medicaid expansions have improved health insurance coverage and health care access for low-income individuals.2–9 However, less is known about the heterogeneous effects the expansions likely have had based on pre-expansion income eligibility. This is especially important for understanding the Medicaid expansion effects on women with dependent children given the extensive pre-expansion differences in parent eligibility between states. Among expanding states, pre-expansion eligibility (in 2013) for parents with dependent children ranged from 16% FPL in Arkansas to 215% FPL in Minnesota.10 Therefore, the proportion of low-income parents likely to gain from the Medicaid expansions varies across expanding states.

This study examines the heterogeneity in Medicaid expansion effects on low-income women with dependent children by the state-level pre-expansion eligibility for parents to more accurately understand changes in coverage, access, and health in this population. Changes in these outcomes can have broader effects on children and households. Children's use of medical care is partly dependent on their parents' access and service use.11,12 Children of insured parents are more likely to see health care providers, receive a well-child visit,13 and have a usual source of health care.14

A handful of studies have reported greater coverage and access to care among women with or without children.15–18 However, most previous research has not considered the likely heterogeneity based on pre-expansion income eligibility. Our study adds to this literature by directly examining this heterogeneity in expansion effects on women with dependent children. We also examine effects on all women 19–64 years of age with dependent children, not only those of reproductive age.

Materials and Methods

Data and sample

We use data from the 2011 to 2018 American Community Survey (ACS) to examine effects on insurance coverage.19 The ACS is an annual survey of a nationally representative sample that is nearly 1% of the U.S. population. Sampled individuals are legally required to respond to the survey. In addition to standard demographic and socioeconomic data, the ACS collects detailed information on current health insurance coverage and source. We evaluate the following five binary measures of health insurance status and type: any insurance, Medicaid coverage, employer-sponsored coverage, independently purchased coverage, and any private coverage (either employer-sponsored or independently purchased coverage).

We also use data from the Behavioral Risk Factors Surveillance System (BRFSS) from 2011 through 2018 to evaluate health care access and health status.20 BRFSS is a cross-sectional telephone survey conducted every month in all 50 states as well as the District of Columbia by using random-digit dialing for both landlines and cell phones. We use three binary measures for health care access: (1) avoiding medical care due to cost in the past 12 months; (2) having at least one personal doctor or health provider; and (3) completing a routine medical checkup in the past 12 months. For health status, we evaluate the following three measures: (1) a five-point Likert scale for general health, (2) number of days in the past 30 days not in good physical health, and (3) number of days during the past 30 not in good mental health.

We limit the analytical samples from both the ACS and BRFSS to low-income (<138% FPL) women 18–64 years of age with at least one dependent child younger than 18 years old. To select the sample, we compare family income to the FPL in each year considering the number of adults and children. Unlike the ACS which reports exact income, BRFSS records income in ranges. In BRFSS, the income is reported as eight categories: less than $10,000, $10,000 to less than $15,000, $15,000 to less than $20,000, $20,000 to less than $25,000, $25,000 to less than $35,000, $35,000 to less than $50,000, $50,000 to less than $75,000, and $75,000 or more. Therefore, we use the midpoints of these ranges to select the sample (77.2% of the selected sample have income below $25,000, 22.4% have income between 25,000 and $50,000, and 0.4% have higher income). BRFSS did not ask about the total number of adults in the household for respondents in the cell-phone sample during 2011–2013 (about 14% of the total analytical sample). In this case, we assign the number of adults based on reported marital status (two adults for married or cohabitating, one otherwise). In total, the analytical sample includes 584,851 individuals from ACS and 128,110–131,304 individuals from BRFSS (depending on the outcome). We include data from 2011 through 2013 (3 years) as the period before the Medicaid expansions and 2014 to 2018 (5 years) as the postexpansion period. The sample descriptive statistics are in Supplementary Appendix Table SA1 for ACS and Supplementary Appendix Table SA2 for BRFSS.

Research design and statistical analysis

We classify the 26 states plus D.C. that expanded Medicaid in 2014 into 3 groups based on the state pre-expansion (in 2013) income eligibility for parents with dependent children (Supplementary Appendix Table SA3). The first group includes 11 expanding states with eligibility below 90% FPL in 2013, which we refer to as the low pre-expansion eligibility group. The second group includes seven states that had income eligibility above 90% FPL but below 138% FPL in 2013, which we refer to as high pre-expansion eligibility group. The third group includes nine states that already had Medicaid eligibility for parents at 138% FPL or higher in 2013, so which we refer to as the full pre-expansion eligibility group.

We use a difference-in-differences design and ordinary least squares regression to estimate the Medicaid expansion effects. The first model combines all postexpansion years from 2014 to 2018 into one period as shown below:

In Equation (1), is one of the study outcomes described above for person i in state s in year t. is a binary indicator for Medicaid expansion states. The model is estimated separately for each of the three expansion state groups based on pre-expansion eligibility, low, high, and full eligibility, relative to nonexpanding states. For example, when estimating the model for expansion states that had low pre-expansion eligibility, the expansion states that had high or full pre-expansion eligibility are excluded. is a binary indicator for years 2014–2018 with 2011–2013 as the reference period. is the difference-in-differences estimate of the Medicaid expansion effect across 2014–2018. includes is a vector of conceptually relevant individual-level demographic and socioeconomic characteristics associated with coverage and health, including age (which we enter flexibly as either year-by-year dummies in ACS or dummies for the age ranges in BRFSS), race/ethnicity, education, employment status, marital status, foreign-born status, and U.S. citizenship status (last two variables only in ACS data).5,6,18,21 When estimating the model with BRFSS data, the model controls for two additional variables related to BRFSS sampling are included: homeownership status, and whether respondent was selected as a cell phone or landline user, as these are part of BRFSS sampling.22,23 are state fixed effects accounting for time-invariant differences between states, and includes year fixed effects that capture national changes in outcomes over time (shared between expansion and nonexpansion states). The coefficient of the interaction term between a given parental eligibility expansion group and the postexpansion period indicator, , is the estimated Medicaid expansion effect under the ACA in that group of states across the five postexpansion years.

We also estimate the following event study model with year-by-year effects:

includes indicators for 2011, 2012, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017, or 2018 (with 2013 as the reference category). All other variables are as described above. The interactions between expansion status and 2011 and 2012 (relative to 2013) capture differences in outcome pretrends between expansion and nonexpansion states (the difference-in-differences model assumes their coefficients, γ1 and γ2 are null). The coefficients of the postexpansion year interactions, are the effects of the ACA Medicaid expansion in 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017, and 2018, respectively (relative to 2013).

The standard errors are clustered at the state level, and all analyses are weighted using the sampling weights. Institutional Review Board review is not required for this study that uses deidentified publicly available data.

Sensitivity checks

We do a series of sensitivity checks. The main models exclude five states (all with low pre-expansion eligibility) that expanded Medicaid after 2014 because these states did not experience the Medicaid expansion effects for the entire period of 2014–2018 (Supplementary Appendix Table SA3). In sensitivity analyses, however, we add these five states back. Also, two Medicaid nonexpansion states, Maine and Wisconsin, reduced Medicaid parent eligibility from 200% FPL in 2013 to nearly 100% FPL in 2014. Therefore, we exclude both states in other models. Massachusetts adopted the ACA Medicaid expansion in 2014 with eligibility increasing from 133% to 138% FPL (using the Modified Adjusted Gross Income). In a sensitivity analysis, we switch Massachusetts from the high pre-expansion eligibility group to the full pre-expansion eligibility group. Finally, we limit the BRFSS sample to nonpregnant mothers at survey time since Medicaid eligibility is higher during pregnancy and 2 months after delivery. ACS does not have data on pregnancy status.

Results

Effects on health insurance coverage

Figure 1 shows health insurance coverage and types between 2011 and 2018 for women with dependent children and income below 138% FPL in ACS in expansion states (separately by pre-expansion eligibility) and nonexpansion states. In 2014–2018, expansion states with low pre-expansion eligibility had the largest increase in any coverage and Medicaid coverage compared with nonexpansion states. In contrast, expanding states with high or full pre-expansion eligibility had a smaller increase in Medicaid coverage. Nonexpansion states had an increase in any private coverage relative to expansion states. Overall, insurance coverage trends in 2011–2013 were similar between expansion and nonexpansion states.

FIG. 1.

Health insurance coverage and type by year, state Medicaid expansion status, and state-level pre-expansion eligibility in expansion states, women with dependent children below 138% federal poverty level, ACS 2011–2018. The dashed line with black point mark indicates the changes in the outcome rates from 2011 to 2019 in states that did not adopt the ACA Medicaid expansion in 2014. The solid line with triangle mark indicates the changes in the outcome rates from 2011 to 2019 in states that adopt the ACA Medicaid expansion in 2014. ACS, American Community Survey.

Table 1 shows the difference-in-differences regression estimates of the expansion effects on insurance coverage status and type combining 2014–2018 into one period. These estimates echo the descriptive trends in the graphs. There is stark heterogeneity in coverage status changes based on pre-expansion Medicaid eligibility, with the largest effects among states with low pre-expansion eligibility. Medicaid coverage increased by 16, 9, and 2 percentage points in expansion states with low, high, and full pre-expansion eligibility, respectively (all statistically significant at p < 0.05), compared with nonexpansion states. At the same time, there is a statistically significant decrease in private coverage rates of 6–7 percentage points in all 3 expansion groups and in both employer-sponsored and independently purchased coverage, again compared with nonexpansion states. All sensitivity analyses described above show overall similar results (Supplementary Appendix Table SA4).

Table 1.

Difference-in-Differences Estimates of Affordable Care Act Medicaid Expansion Effects on Health Insurance Coverage of Women with Dependent Children Below 138% Federal Poverty Level by State-Level Pre-Expansion Eligibility Using Data from 2011 to 2018 American Community Survey and Combining Postexpansion Years 2014–2018

| N | Effect | SE | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low pre-expansion eligibility group | ||||

| Any insurance | 336,250 | 0.093a | (0.022) | [0.049 to 0.137] |

| Medicaid coverage | 336,250 | 0.161a | (0.027) | [0.105 to 0.216] |

| Any private coverage | 336,250 | −0.062a | (0.008) | [−0.078 to −0.046] |

| Employer-sponsored coverage | 336,250 | −0.036a | (0.006) | [−0.048 to −0.023] |

| Independently purchased coverageb | 336,250 | −0.028a | (0.006) | [−0.041 to −0.015] |

| High pre-expansion eligibility group | ||||

| Any insurance | 403,830 | 0.031 | (0.021) | [−0.012 to 0.074] |

| Medicaid coverage | 403,830 | 0.092a | (0.019) | [0.053 to 0.132] |

| Any private coverage | 403,830 | −0.067a | (0.006) | [−0.079 to −0.055] |

| Employer-sponsored coverage | 403,830 | −0.037a | (0.005) | [−0.047 to −0.028] |

| Independently purchased coverage | 403,830 | −0.030a | (0.005) | [−0.042 to −0.019] |

| Full pre-expansion eligibility group | ||||

| Any insurance | 347,507 | −0.034a | (0.008) | [−0.051 to −0.018] |

| Medicaid coverage | 347,507 | 0.025c | (0.011) | [0.002 to 0.049] |

| Any private coveragea | 347,507 | −0.059a | (0.007) | [−0.073 to −0.045] |

| Employer-sponsored coverage | 347,507 | −0.035a | (0.007) | [−0.050 to −0.021] |

| Independently purchased coveragea | 347,507 | −0.025a | (0.006) | [−0.037 to −0.014] |

These effects are estimated from the difference-in-differences [Eq. (1)] model using the 2011–2018 ACS data. The numbers under column “Effects” represent the change in likelihood of having coverage or coverage type in 2014–2018 versus 2011–2013 as a result of the Medicaid expansions. All regressions control for age, gender, race/ethnicity, education, employment status, foreign-born status, U.S. citizenship status, state, and year fixed effects. Estimates are weighted using sampling probability weights. Standard errors in parentheses are clustered at the state level.

Significant at 1% level.

Indicates that point estimates should be viewed with caution due to differential pretrends in these outcomes that may bias the difference-in-differences estimates.

Significant at 5% level.

ACS, American Community Survey; CI, confidence interval.

The year-by-year difference-in-differences estimates in Supplementary Appendix Table SA5 show similar results overall. The increase in Medicaid coverage and decline in private coverage were greater after 2014, the first year of the expansion, with minimal differences in 2015–2018. There are no significant differences in outcome trends during 2011–2013 between expansion and nonexpansion states, except for independently purchased coverage in expansion states with low pre-expansion eligibility, and any private coverage (and independently purchased coverage) in expansion states with full pre-expansion eligibility when comparing the no parental eligibility expansion group and nonexpanding states (Supplementary Appendix Table SA6). Overall, these pretrend checks plus the plotted trends lend support to the validity of the difference-in-differences DD estimates in most cases.

Effects on health care access

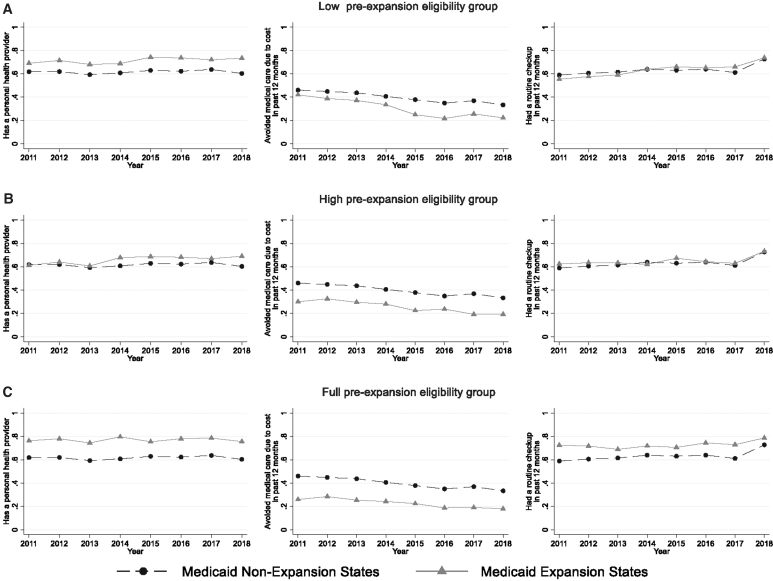

Figure 2 plots the health care access indicators over time for expansion states (by pre-expansion eligibility) compared with nonexpansion states in the BRFSS sample. There is an improvement in all three access measures (personal health provider, cost as a barrier to care, and a routine checkup) in expansion states with low pre-expansion eligibility relative to nonexpansion states. In contrast, there is little difference in trends between expansion states with high or full pre-expansion eligibility compared with nonexpansion states, except for an increase in reporting a personal provider in the former group.

FIG. 2.

Health care access by year, state Medicaid expansion status, and state-level pre-expansion eligibility in expansion states, women with dependent children below 138% federal poverty level, BRFSS 2011–2018. The dashed line with black point mark indicates the changes in the outcome rates from 2011 to 2019 in states that did not adopt the ACA Medicaid expansion in 2014. The solid line with triangle mark indicates the changes in the outcome rates from 2011 to 2019 in states that adopt the ACA Medicaid expansion in 2014. BRFSS, Behavioral Risk Factors Surveillance System.

Table 2 reports the difference-in-differences estimates for the three health care access measures. There are statistically significant improvements in all three access measures in expansion states with low pre-expansion eligibility: personal health provider (+3 percentage-points); cost as a barrier to care (−7 percentage-points); and routine checkups (+6 percentage-points). In expansion states with high pre-expansion eligibility, there is also an increase in reporting a personal health provider (+7 percentage-points), but small and statistically insignificant changes in the two other access measures. Similarly, changes in access are small in expansion states with full pre-expansion eligibility, with the only marginally significant (p < 0.1) change being an increase in reporting cost as a barrier to care (+2 percentage-points). Results from the sensitivity checks (described above) are similar (Supplementary Appendix Table SA7).

Table 2.

Difference-in-Differences Estimates of Affordable Care Act Medicaid Expansion Effects on Health Care Access of Women with Dependent Children Below 138% Federal Poverty Level by State-Level Pre-Expansion Eligibility Using Data from 2011 to 2018 Behavioral Risk Factors Surveillance System and Combining Postexpansion Years 2014–2018

| N | Effects | SE | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low pre-expansion eligibility group | ||||

| Has a personal health provider | 84,854 | 0.034a | (0.015) | [0.002 to 0.065] |

| Avoided medical care due to cost in past 12 months | 84,900 | −0.068b | (0.018) | [−0.105 to −0.031] |

| Had a routine checkup in past 12 months | 82,544 | 0.057b | (0.015) | [0.027 to 0.088] |

| High pre-expansion eligibility group | ||||

| Has a personal health provider | 83,961 | 0.069a | (0.027) | [0.014 to 0.124] |

| Avoided medical care due to cost in past 12 months | 84,016 | −0.004 | (0.014) | [−0.033 to 0.025] |

| Had a routine checkup in past 12 months | 81,853 | −0.010 | (0.012) | [−0.034 to 0.014] |

| Full pre-expansion eligibility group | ||||

| Has a personal health provider | 83,192 | 0.007 | (0.013) | [−0.018 to 0.033] |

| Avoided medical care due to cost in past 12 months | 83,252 | 0.020c | (0.010) | [−0.002 to 0.041] |

| Had a routine checkup in the past 12 months | 81,251 | −0.018 | (0.011) | [−0.041 to 0.006] |

These effects were estimated from the difference-in-differences [Eq. (1)] model using the 2011–2018 BRFSS data. The numbers under column “Effects” represent the changes in health care access measures during 2014–2018 versus 2011–2013 as a result of the Medicaid expansions. All regressions controlled for age, gender, race/ethnicity, education, employment status, home ownership, cell phone sample status, state, and year fixed effects. Estimates are weighted using sampling probability weights. Standard errors in parentheses are clustered at the state level.

Significant at 5% level.

Significant at 1% level.cSignificant at 10% level.

BRFSS, Behavioral Risk Factors Surveillance System.

Supplementary Appendix Table SA8 shows the year-by-year difference-in-differences estimates. These results generally echo those from the model combining postexpansion years. In expansion states with low pre-expansion eligibility, effects are generally more prominent after 2014, although not all estimates are statistically significant. The year-by-year models also show no statistically significant differences in access pre-expansion trends between expansion and nonexpansion states (Supplementary Appendix Table SA9).

Effects on health status

Figure 3 shows the trends in the three health status measures over time in the BRFSS sample. These trends are largely similar between expansion states irrespective of pre-expansion eligibility and nonexpansion states, suggesting no evidence of expansion effects on these health outcomes in this population.

FIG. 3.

Health status by year, state Medicaid expansion status, and state-level pre-expansion eligibility in expansion states, women with dependent children below 138% federal poverty level, BRFSS 2011–2018. The dashed line with black point mark indicates the changes in the outcome rates from 2011 to 2019 in states that did not adopt the ACA Medicaid expansion in 2014. The solid line with triangle mark indicates the changes in the outcome rates from 2011 to 2019 in states that adopt the ACA Medicaid expansion in 2014.

Similar to the descriptive graphs, the difference-in-differences estimates in Table 3 show no statistically significant changes in health combining postexpansion years. Sensitivity checks also show similar results (Supplementary Appendix Table SA10). The year-by-year models show an increase in days not in good physical health in some years in states with less than full pre-expansion eligibility (Supplementary Appendix Table SA11); but there are significant differential pretrends between these states and nonexpansion states in this outcome (Supplementary Appendix Table SA12). There is also an increase in days not in good mental health in states with high pre-expansion eligibility in 2014 and 2018.

Table 3.

Difference-in-Differences Estimates of Affordable Care Act Medicaid Expansion Effects on Health Status of Women with Dependent Children Below 138% Federal Poverty Level by State-Level Pre-Expansion Eligibility Using Data from 2011 to 2018 Behavioral Risk Factors Surveillance System and Combining Postexpansion Years 2014–2018

| N | Effects | SE | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low pre-expansion eligibility group | ||||

| Self-rated health (1–5, poor to excellent) | 84,897 | 0.003 | (0.026) | [−0.050 to 0.056] |

| Days in the past 30 not in good physical healtha | 83,622 | 0.263 | (0.366) | [−0.486 to 1.013] |

| Days in the past 30 not in good mental health | 83,871 | 0.213 | (0.364) | [−0.531 to 0.957] |

| High pre-expansion eligibility group | ||||

| Self-rated health (1–5, poor to excellent) | 84,011 | 0.016 | (0.037) | [−0.059 to 0.092] |

| Days in the past 30 not in good physical healtha | 82,816 | 0.180 | (0.430) | [−0.705 to 1.065] |

| Days in the past 30 not in good mental health | 83,001 | −0.136 | (0.356) | [−0.869 to 0.596] |

| Full pre-expansion eligibility group | ||||

| Self-rated health (1–5, poor to excellent) | 83,222 | 0.028 | (0.054) | [−0.083 to 0.138] |

| Days in the past 30 not in good physical health | 81,926 | −0.100 | (0.331) | [−0.779 to 0.578] |

| Days in the past 30 not in good mental health | 82,172 | 0.023 | (0.427) | [−0.852 to 0.899] |

These effects were estimated from the difference-in-differences [Eq. (1)] model using the 2011–2018 BRFSS data. The numbers under column “Effects” represent the changes in health status during 2014–2018 versus 2011–2013 as a result of the Medicaid expansions. All regressions controlled for age, gender, race/ethnicity, education, employment status, home ownership, cell phone sample status, state, and year fixed effects. Estimates are weighted using sampling probability weights. Standard errors in parentheses are clustered at the state level.

Indicates that point estimates should be viewed with caution due to differential pretrends in these outcomes that may bias the difference-in-differences estimates.

Discussion

This study provides evidence on heterogeneity of the ACA Medicaid expansion effects on coverage and access to care among low-income women with dependent children by the state pre-expansion eligibility for parents. As expected, expansion states with low pre-expansion eligibility (below 90% FPL) had the largest increase in Medicaid take-up. In these states, Medicaid coverage increased by 16 percentage points on average, whereas the uninsured rate declined by 9 percentage points. The difference between the change in Medicaid coverage and any insurance is a decline in private coverage. In contrast, Medicaid take-up increased by 6 percentage points in states with high pre-expansion eligibility (90–<138% FPL) with little change in the uninsured rate, again due to a decline in private coverage. There is a small increase in Medicaid coverage in states with full pre-expansion eligibility by 2.5 percentage points. This increase might reflect a “welcome-mat” effect, whereby previously eligible women with dependent children who had not enrolled in Medicaid are participating, perhaps due to greater awareness about Medicaid eligibility, similar to evidence for increased Medicaid coverage among children.24

There are sizable declines in private insurance coverage in expansion states irrespective of pre-expansion eligibility. Some of these might be crowd-out (switching) from private (especially independently purchased coverage) to Medicaid coverage. But it is also due to greater take-up of private coverage through the exchange market and employers in nonexpansion states. Because of the individual mandate (effective for all study years), low-income mothers in nonexpansion states are more likely to seek private coverage than their counterparts in states that expanded Medicaid. These changes in private coverage are within range of estimates from general samples of low-income individuals or childless adults.2,3

The heterogeneity in expansion effects on access by state pre-expansion eligibility largely mirror that in coverage. There is an increase in having a personal health provider, not reporting cost as a barrier to care, and having a routine checkup in expansion states with low pre-expansion eligibility but little change in other expansion states especially in the last two measures. Future work to examine whether contextual factors (such as availability of providers who participate in Medicaid) or individual characteristics (such as time costs and knowledge about providers) contribute to heterogeneity in access changes (beyond differences in coverage gains) is relevant.

There is no evidence of discernable effects on health in this population, in contrast to recent evidence of improvement in self-rated health in the broader population of low-income adults.9,25 Self-reported health status depends on many factors (access/use of care, perceived risk, financial security, diagnosed medical problems, mental health, and health behaviors), which can change in different ways with gaining Medicaid coverage.26 Furthermore, meaningful health gains may take time to observe even with increased access and use of services. Examining other health outcomes and longer periods in future work is important.

Medicaid eligibility is higher during pregnancy—average income eligibility was 197% FPL across states in 2013—but drops back to prepregnancy eligibility level 2 months after pregnancy. This discontinuity in insurance coverage for many low-income women may reduce access to high-quality postpartum care.27 Our findings suggest that the ACA Medicaid expansions have reduced differences in coverage and access to care of low-income women (<138% FPL) with dependent children between expansion states. Particularly in expansion states with low pre-expansion eligibility, the findings imply a decline in the proportion of women experiencing coverage discontinuity shortly after delivery. These findings provide a picture of potential changes in coverage and access for low-income women in nonexpansion states if these states choose to expand their Medicaid coverage. Some states have aimed at extending pregnancy-based Medicaid coverage from 60 days to 12 months postpartum.28 Our study provides evidence for a complementary approach that extends income eligibility to women at any time. This coverage may also improve preconception care and child health.

Limitations

The study outcomes are self-reported and may involve errors. It is unlikely though that there are differential errors or biases in reporting across states or expansion status. If so, such errors may inflate standard errors and reduce statistical significance but are unlikely to bias the expansion effect estimates. Another limitation is that income is reported in categories in BRFSS so that there might be misclassifications of Medicaid expansion eligibility for some individuals. Again, such errors are unlikely to differ by Medicaid expansion status. Finally, the data are from cross-sectional samples and we cannot follow the same individuals over time. Longitudinal data can provide further insights about the dynamics of changes in outcomes for the same individuals (such as switching insurance type).

Conclusions

The study shows heterogeneity in effects of the ACA Medicaid expansions on coverage and access to health care of low-income women with dependent children based on the state-level pre-expansion eligibility for parents. Expansion states with low pre-expansion eligibility had the largest gains in coverage and access. These findings indicate that the Medicaid expansions have reduced differences between expansion states in health insurance coverage of low-income women with dependent children and their access to care. There is little evidence of changes in health status in this population thus far.

Supplementary Material

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Funding Information

This study was supported by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, grant 1R03 DE02804101.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Appendix Table SA1

Supplementary Appendix Table SA2

Supplementary Appendix Table SA3

Supplementary Appendix Table SA4

Supplementary Appendix Table SA5

Supplementary Appendix Table SA6

Supplementary Appendix Table SA7

Supplementary Appendix Table SA8

Supplementary Appendix Table SA9

Supplementary Appendix Table SA10

References

- 1. The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. Status of State Action on the Medicaid Expansion Decision. The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. State Health Facts Web site. Published 2020. Available at: https://www.kff.org/health-reform/state-indicator/state-activity-around-expanding-medicaid-under-the-affordable-care-act/ Accessed February 2, 2020.

- 2. Wehby GL, Lyu W. The impact of the ACA Medicaid expansions on health insurance coverage through 2015 and coverage disparities by age, race/ethnicity, and gender. Health Serv Res 2017;53:1248–1271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kaestner R, Garrett B, Chen J, Gangopadhyaya A, Fleming C. Effects of ACA Medicaid expansions on health insurance coverage and labor supply. J Policy Anal Manage 2017;36:608–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Miller S, Wherry LR. Health and access to care during the first 2 years of the ACA Medicaid expansions. N Engl J Med 2017;376:947–956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Courtemanche C, Marton J, Ukert B, Yelowitz A, Zapata D. Early impacts of the Affordable Care Act on health insurance coverage in Medicaid expansion and non-expansion states. J Policy Anal Manage 2017;36:178–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Simon K, Soni A, Cawley J. The impact of health insurance on preventive care and health behaviors: Evidence from the first two years of the ACA Medicaid expansions. J Policy Anal Manage 2017;36:390–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wherry LR, Miller S. Early coverage, access, utilization, and health effects associated with the Affordable Care Act Medicaid Expansions: A quasi-experimental study Medicaid expansions and coverage, access, utilization, and health effects. Ann Intern Med 2016;164:795–803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lyu W, Shane DM, Wehby GL. Effects of the recent Medicaid expansions on dental preventive services and treatments. Med Care 2020;58:749–755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Courtemanche C, Marton J, Ukert B, Yelowitz A, Zapata D. The impact of the Affordable Care Act on health care access and self-assessed health in the Trump Era (2017–2018). Health Serv Res 2020;55(Suppl 2):841–850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. Medicaid Income Eligibility Limits for Parents, 2002–2020. State Health Facts website. Published 2020. Available at: https://www.kff.org/medicaid/state-indicator/medicaid-income-eligibility-limits-for-parents/Accessed November 2020.

- 11. Isong IA, Zuckerman KE, Rao SR, Kuhlthau KA, Winickoff JP, Perrin JM. Association between parents' and children's use of oral health services. Pediatrics 2010;125:502–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ku L, Broaddus M. Coverage of parents helps children, too. Washington, DC: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Davidoff A, Dubay L, Kenney G, Yemane A. The effect of parents' insurance coverage on access to care for low-income children. Inquiry 2003;40:254–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Guendelman S, Wier M, Angulo V, Oman D. The effects of child-only insurance coverage and family coverage on health care access and use: Recent findings among low-income children in California. Health Serv Res 2006;41:125–147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Daw JR, Sommers BD. The Affordable Care Act and access to care for reproductive-aged and pregnant women in the United States, 2010–2016. Am J Public Health 2019;109:565–571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lee LK, Monuteaux MC, Galbraith AA. Women's Affordability, access, and preventive care after the Affordable Care Act. Am J Prev Med 2019;56:631–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Johnston EM, Strahan AE, Joski P, Dunlop AL, Adams EK. Impacts of the Affordable Care Act's Medicaid expansion on women of reproductive age: Differences by parental status and state policies. Womens Health Issues 2018;28:122–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Margerison CE, MacCallum CL, Chen J, Zamani-Hank Y, Kaestner R. Impacts of Medicaid expansion on health among women of reproductive age. American J Prev Med 2020;58:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ruggles S, Flood S, Goeken R, et al. IPUMS USA: Version 10.0 [dataset]. Minneapolis, MN: IPUMS, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Behavioral risk factor surveillance system survey data. Atlanta, Georgia: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2011–2018. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lyu W, Wehby GL. The impacts of the ACA Medicaid expansions on cancer screening use by primary care provider supply. Med Care 2019;57:202–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wehby G, Lyu W, Shane D. The impact of the ACA Medicaid expansions on dental visits by dental coverage generosity and dentist supply. Med Care 2019;57:781–787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lyu W, Wehby GL. The impacts of the ACA Medicaid expansions on cancer screening use by primary care provider supply. Med Care 2019;57:202–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ugwi P, Lyu W, Wehby GL. The effects of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act on children's health coverage. Med Care 2019;57:115–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Semprini J, Lyu W, Shane DM, Wehby GL. The effects of ACA Medicaid expansions on health after 5 years. Med Care Res Rev 2020. [Epub ahead of print]; DOI: 10.1177/1077558720972592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Soni A, Wherry LR, Simon KI. How have ACA insurance expansions affected health outcomes? Findings from the literature. Health Aff (Millwood) 2020;39:371–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gordon SH, Sommers BD, Wilson IB, Trivedi AN. Effects of Medicaid expansion on postpartum coverage and outpatient utilization. Health Aff (Millwood) 2020;39:77–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Eckert E. It's past time to provide continuous Medicaid coverage for one year postpartum. Health Affairs Blog 2020. Available at: https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20200203.639479/full/ Accessed November 1, 2020.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.