Abstract

Introduction: To determine the effects of a novel lifestyle intervention combining lifestyle behavioral education with the complementary–integrative health modality of guided imagery (GI) on dietary and physical activity behaviors in adolescents. The primary aim of this study was to determine the incremental effects of the lifestyle education, stress reduction GI (SRGI), and lifestyle behavior GI (LBGI) components of the intervention on the primary outcome of physical activity lifestyle behaviors (sedentary behavior, light, moderate, and vigorous physical activity), as well as dietary intake behaviors, at the completion of the 12-week intervention. The authors hypothesized that the intervention would improve obesity-related lifestyle behaviors.

Materials and Methods: Two hundred and thirty-two adolescent participants (aged 14–17 years, sophomore or junior year of high school) were cluster randomized by school into one of four intervention arms: nonintervention Control (C), Lifestyle education (LS), SRGI, and LBGI. After-school intervention sessions were held two (LS) or three (SRGI, LBGI) times weekly for 12 weeks. Physical activity (accelerometry) and dietary intake (multiple diet recalls) outcomes were assessed pre- and postintervention. Primary analysis: intention-to-treat (ITT) mixed-effects modeling with diagonal covariance matrices; secondary analysis: ad hoc subgroup sensitivity analysis using only those participants adherent to protocol.

Results: ITT analysis showed that the Healthy Eating Index (HEI) increased in the LS group compared with C (p = 0.02), but there was no additional effect of GI. Among adherent participants, sedentary behavior was decreased stepwise relative to C in SRGI (d = −0.73, p = 0.004) > LBGI (d = −0.59, p = 0.04) > LS (d = −0.41, p = 0.07), and moderate + vigorous physical activity was increased in SRGI (d = 0.58, p = 0.001). Among adherent participants, the HEI was increased in LS and SRGI, and glycemic index reduced in LBGI.

Conclusions: While ITT analysis was negative, among adherent participants, the Imagine HEALTH lifestyle intervention improved eating habits, reduced sedentary activity, and increased physical activity, suggesting that GI may amplify the role of lifestyle education alone for some key outcomes. Clinical Trials.gov ID: NCT02088294

Keywords: guided imagery, stress reduction, adolescents, Latino, obesity, lifestyle intervention

Introduction

Latinx adolescents suffer from a high prevalence of obesity1 and obesity-related comorbidities, such as type 2 diabetes.2–4 Insulin resistance, rather than body fat per se, is the primary pathophysiological factor leading to metabolic disease risk.5,6 Therefore, targeting reductions in insulin resistance through changing modifiable lifestyle behaviors, such as eating and physical activity, is key in the prevention of type 2 diabetes in overweight adolescents.7–10

While chronic stress has been linked both to the development of obesity and obesity-related morbidities, previous intervention strategies have not addressed this issue nor have they utilized complementary mind–body modalities to reduce chronic stress as part of an integrative approach to obesity prevention and/or treatment. The authors' previously reported pilot intervention for Latinx adolescents with obesity11 showed that compared with lifestyle education controls, individual Interactive Guided ImagerySM added to lifestyle education acutely reduced the stress biomarker salivary cortisol, reduced sedentary behavior, and increased moderate physical activity compared with lifestyle education alone.11

The authors now describe the primary outcomes of a randomized controlled trial (RCT) in predominantly Latinx adolescents of a novel lifestyle intervention that uses lifestyle behavioral education combined with guided imagery (GI) designed to reduce stress and improve lifestyle behaviors. The primary aim of this study was to determine the incremental effects of the didactic lifestyle education (LS), stress reduction GI (SRGI), and lifestyle behavior GI (LBGI) components of the intervention on physical activity behaviors (including sedentary behavior, light, moderate, and vigorous physical activity) at the completion of the 12-week intervention. The changes in dietary behavior following intervention were also assessed. The authors hypothesized that all intervention arms would show improvement in obesity-related lifestyle behaviors beyond nonintervention control and that SRGI and LBGI arms of the intervention would show greater improvement in these outcomes than LS alone, with the greatest improvement expected in LBGI.

Materials and Methods

Study design

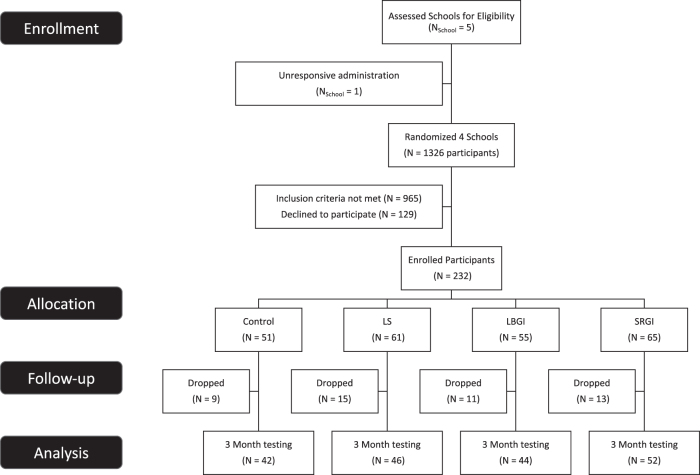

The full Imagine HEALTH protocol has been previously described in detail.12 High school sophomores and juniors, aged 14–17 years, were recruited during in-person study team visits to required classes (History and English) in four urban high schools, prescreened, and subsequently called by study staff for full eligibility screening. Two hundred and thirty-two eligible participants underwent group consenting and enrollment visits (Fig. 1).12 Reasons for exclusion (some participants had multiple reasons) included: inadequate time available (n = 750); incorrect age or grade (n = 19); serious chronic illness or medications (n = 27); eating disorder, psychiatric disorder, cognitive or behavioral disability (n = 29); lack of English fluency (n = 8); prior participation in school council programs (n = 5); sibling in the program (n = 3); concurrent after-school activities that interfere with intervention attendance (n = 214).

FIG. 1.

Consort diagram. GI, guided imagery; LBGI, lifestyle behavior GI; LS, lifestyle education; SRGI, stress reduction GI.

The intervention was conducted in three successive annual waves from January to May, 2015–2017, ending as planned at completion of the intervention. Cluster randomization was performed at the school level. Before each wave, one of the four study arms was randomly assigned to each school. Blocking was implemented such that no school could get the same study arm more than once across the three waves of the study. Across the total duration of the study, each school delivered three of the four different arms of the intervention.

The four intervention arms were: (1) nonintervention “Control” (C); (2) “Lifestyle education” (LS), consisting of 12 weeks of twice weekly 75-min sessions of didactic and experiential education relating to healthy eating (one session per week) and physical activity (one session per week) practices consistent with consensus pediatric recommendations,12–15 in particular emphasizing modification in quality of carbohydrate intake8,16,17 and key concepts of “Intuitive Eating,”18–20 a nondieting approach to healthy eating; (3) “SRGI”, which received the same lifestyle education plus an additional once weekly 75-min group SRGI session for 10 sessions; (4) “LBGI”, which received the same lifestyle education, plus four weekly 75-min group SRGI sessions, followed by six weekly sessions of GI designed to motivate improved eating and activity behaviors. The final two weekly sessions for both the SRGI and LBGI arms contained imagery content that integrated the entire 12-week program. Group GI was delivered in the context of the facilitated group process known as “council,” with specific imagery content as previously detailed.12,21

This study was approved by the Internal Review Board (IRB, #HS-13-00836) of the University of Southern California Health Science Campus. Parents signed informed consent, and participants signed youth assent forms. This trial was registered with Clinical Trials.gov (https://clinicaltrials.gov). Consort checklist can be found in Supplementary Data.

Outcome measures

Outcome measures were assessed at baseline (preintervention) and upon completing the 12-week intervention (postintervention).12

Physical activity (primary outcome)

Study participants wore the triaxial Actigraph accelerometer model GT3X+ on their nondominant wrist for 1-week measurement period,12 set to collect movement information at the frequency of 60 Hz. Wear time validation was conducted using the criteria defined by Choi et al.22 and was cross-checked with self-reported nonwear time documented in a paper log. Only participants with at least four valid wear days, defined as 10 or more hours of valid wear time, were included in the data set (5 excluded at baseline, 11 excluded at 3 months). Total minutes spent in sedentary behavior (vector magnitude [VM per 5 sec] <305), light (VM 306–817), moderate (VM 818–1,968), and vigorous (VM >1,968) intensity activities were defined in accordance with thresholds described in Chandler et al.23

Dietary intake

Dietary intake was collected12 using multiple pass dietary recall interviews using the Nutrition Data System for Research (NDS-R version 2014–2017), a well-validated 24-hour recall dietary assessment method.24,25 Main dietary outcome variables for this report included total daily energy (calories), macronutrients, total and added sugars, fiber (soluble and insoluble), glycemic load and glycemic index, and the Healthy Eating Index (HEI)-2015, a validated, composite eating index composed of 13 components that reflect the different food groups and key recommendations in the 2015–2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans.26,27 The mean energy intake was regressed on body mass index (BMI), and recalls from nine participants (seven from baseline and two from post-test) for which the resulting standard residual was >2 were considered implausible and excluded from analysis.

Program adherence

Attendance to intervention sessions was defined as being present for at least 45 min of the 75-min class, inclusive of participation in the GI exercise. Adherence was defined on the individual participant level as attendance by the participant to at least 75% of lifestyle classes and 75% of GI sessions. For the purposes of the intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis, the authors defined adherence a priori at the group level as 80% of participants attending at least 75% of classes. Adherence was monitored throughout the conduct of the intervention, and measures for improving adherence implemented when needed. These included utilizing young adult study staff to build rapport with participants, making multiple text/phone call reminders of class sessions, mailing of holiday/birthday cards, and offering a variety of cash and noncash (gift cards, movie tickets) incentives, scholastic service learning credits, and letters of recognition for personal portfolio use.12

Adverse events

Adverse events and serious adverse events were assigned using standard clinical research definitions and were defined as definitely unrelated, definitely related, probably related, or possibly related to study procedures.12 All adverse events were tracked, documented, and reported to the Independent Monitoring Committee annually.

Secondary study outcomes assessed

Changes in subjective stress, cortisol biomarkers, anthropometrics, and diabetes-related biomarkers were measured and will be addressed in subsequent reports.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were conducted according to the methodology detailed in the study protocol,12 Briefly, the ITT population includes all participants randomized within the schools. Results display differences in sample size from one measurement to the next, as not every student completed every measurement at baseline or 3 months. All analyses were nested within schools to account for the variability shared within school environment. Statistical modeling of continuous outcomes was accomplished through the use of mixed-effects modeling with diagonal covariance matrices, whereas categorical outcomes were compared using generalized estimating equations. Preliminary analyses of preintervention values of outcomes and participant characteristics were compared across groups to assure that randomization was successful across intervention groups. Participant characteristics that were unequal at baseline (evaluated using analysis of variance F, Fisher's exact, or chi-squared tests) were also included as covariates in analyses. Group effects were assessed using omnibus hypotheses across all groups with the primary endpoint of 12 weeks, followed by post hoc comparisons of group effect. A priori covariates included baseline values, sex, ethnicity, race, BMI (dichotomous indicator of normal vs. overweight at baseline), and year in the study. To evaluate possible group effect differences by BMI categories, the interaction term of treatment group by BMI was added in the model, but dropped due to insignificant association with outcomes.

Additional ad hoc analyses were performed. Change dichotomized into positive or negative was performed for the outcomes, in which comparisons were made using c2 tests to examine the prevalence of improvement across groups. Subgroup sensitivity analysis using only those participants adherent to protocol was performed with ITT model, adjusting for school clustering. A priori power was limited to the primary analyses; thus, for pairwise comparisons, the authors present Cohen's d effect sizes to assess the clinical impact of the difference in intervention. The authors also report p-values, so that the reader can apply a post hoc alpha adjustment of their choice.

Results

Demographics and adherence

Figure 1 shows the flow of participants through recruitment, consenting, randomization, intervention delivery, and outcome measurement. Of 232 enrolled participants, 184 (79%) completed at least one primary outcomes measurement visit at the completion of the 12-week intervention (3-month follow-up).

Table 1 shows baseline demographic and clinical characteristics for the four intervention groups. Overall, 64% of participants were in the 11th grade, 66% were female, 94% were Latinx, and 40% had obesity/overweight. There were no baseline differences in weight, BMI, or other physical health variables between the groups. There were significant baseline differences between the groups in age, grade, and race, and these were thus used as covariates in subsequent analytical models.

Table 1.

Participant Baseline Demographics and Clinical Characteristics by Treatment Group

| Control (n = 51) n (%) | LS (n = 61) n (%) | LBGI (n = 55) n (%) | SRGI (n = 65) n (%) | Total (n = 232) n (%) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade | ||||||

| 10th | 11 (22) | 31 (51) | 23 (42) | 19 (29) | 84 (36) | 0.01 |

| 11th | 40 (78) | 30 (49) | 32 (58) | 46 (71) | 148 (64) | |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 38 (75) | 36 (59) | 40 (73) | 40 (62) | 154 (66) | 0.20 |

| Male | 13 (25) | 25 (41) | 15 (27) | 25 (38) | 78 (34) | |

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| Hispanic or Latino | 50 (98) | 56 (92) | 51 (93) | 61 (94) | 218 (94) | 0.76 |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 1 (2) | 4 (7) | 3 (5) | 4 (6) | 12 (5) | |

| Not reported | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 2 (1) | |

| Race | ||||||

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 1 (0) | 0.02 |

| Asian | 1 (2) | 5 (8) | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | 8 (3) | |

| Black or African American | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (3) | 2 (1) | |

| White | 50 (98) | 55 (90) | 46 (84) | 57 (88) | 208 (90) | |

| Other/more than one race | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | 3 (5) | 1 (2) | 5 (2) | |

| Not reported | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (7) | 4 (6) | 8 (3) | |

| BMI category | ||||||

| Underweight (<5th percentile) | 2 (4) | 2 (3) | 2 (4) | 1 (2) | 7 (3) | 0.41 |

| Normal (5–84th percentile) | 28 (55) | 32 (52) | 32 (58) | 25 (38) | 117 (50) | |

| Overweight (85–94th percentile) | 8 (16) | 7 (11) | 9 (16) | 17 (26) | 41 (18) | |

| Obese (95th+ percentile) | 11 (22) | 13 (21) | 8 (15) | 18 (28) | 50 (22) | |

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) |

16.5 ± 0.5 |

16.2 ± 0.7 |

16.3 ± 0.6 |

16.6 ± 0.6 |

16.4 ± 0.6 |

0.01 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) |

107 ± 25 |

108 ± 28 |

106 ± 27 |

111 ± 24 |

108 ± 26 |

0.70 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) |

66 ± 15 |

64 ± 17 |

66 ± 17 |

67 ± 15 |

66 ± 16 |

0.81 |

| Height (cm) |

155 ± 33 |

158 ± 31 |

152 ± 38 |

157 ± 30 |

156 ± 33 |

0.75 |

| Weight (kg) |

66 ± 22 |

66 ± 18 |

61 ± 16 |

68 ± 17 |

65 ± 18 |

0.19 |

| Waist circumference (cm) |

83 ± 23 |

80 ± 23 |

77 ± 23 |

85 ± 20 |

82 ± 22 |

0.27 |

| BMI (kg/m2) |

24.9 ± 6.4 |

24.3 ± 6 |

23.4 ± 5.1 |

25.7 ± 5.4 |

24.6 ± 5.7 |

0.17 |

| BMI z-score | 0.7 ± 1.2 | 0.6 ± 1.2 | 0.4 ± 1.1 | 0.9 ± 1.2 | 0.6 ± 1.2 | 0.21 |

BMI, body mass index.

The average adherence of all intervention groups was 41% (i.e., 41% of participants attended at least 75% of all possible intervention sessions, compared with the a priori adherence target of 80%). The LS group (twice weekly sessions) had 52% adherence, whereas SRGI and LBGI (thrice weekly sessions) had 37% and 33% adherence, respectively (p = 0.04, by chi-squared). For LS, LBGI, and SRGI groups, adherence to nutrition classes was 61%, 42% and 40%, and for physical activity classes was 39%, 27%, and 22%, respectively. Adherence for GI sessions was 45% in LBGI and 38% in SRGI. Despite overall lower adherence in the GI groups, the total number of actual after-school sessions attended per participant in the three intervention groups was not significantly different (13.3 ± 7.6 of 24 total for LS, 16.7 ± 11.9 of 36 total for SRGI, and 17.6 ± 11.3 of 36 total for LBGI). Attendance was higher in the first 6 weeks of the intervention (59% average session attendance for all three groups combined), compared with weeks 7–12 (47% average session attendance).

Lifestyle behaviors: ITT analysis

Table 2 shows the ITT analysis of changes in dietary intake and physical activity outcomes from baseline to postintervention. There were no between-group differences in sedentary behavior or physical activity. A significant increase was seen in the HEI for the LS group compared with nonintervention C (p = 0.02), along with a trend toward an increase in HEI for LBGI versus C (p = 0.08). The LBGI group additionally showed a marginally significant increase in insoluble fiber (p = 0.06). There were no between-group differences in other dietary intake outcomes. There were no differences in any of the ITT outcomes in participants who had overweight/obesity compared with those participants who were normal weight. In the additional post hoc analysis, the percentage of subjects who showed any degree of decrease in sedentary behavior postintervention compared with baseline was 33%, 62%, 29%, and 54% in C, LS, LBGI, and SRGI groups, respectively, with LS and SRGI showing more participants who decreased sedentary behavior than would be expected (p = 0.035). This analysis showed no other significant changes in the other physical activity behaviors or dietary intake outcomes.

Table 2.

Intention-to-Treat Analysis of Dietary Intake and Physical Activity Outcomes

| Group | Baseline Mean ± SD | 3 Months Mean ± SD | n | Changea Mean ± SD | Estimated marginal Mean (95% CI)b | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dietary intake | |||||||

| Energy (kCal/day) | Control | 1,551.8 ± 617.7 | 1,671.6 ± 1,480.3 | 30 | 125.3 ± 1,338.9 | 310.3 (−64 to 684.7) | |

| LS | 1,621 ± 688.2 | 1,652.6 ± 640.7 | 33 | −45.5 ± 624.9 | 173.1 (−198.3 to 544.6) | 0.58 | |

| LBGI | 1,726.6 ± 1,075.3 | 1,672.9 ± 697 | 22 | −86.8 ± 787.8 | 284.7 (−161.8 to 731.2) | 0.92 | |

| SRGI | 1,553.1 ± 634.5 | 1,527.2 ± 597.7 | 27 | −121.1 ± 697.9 | 47.3 (−334.3 to 429) | 0.28 | |

| Carbohydrate (g/day) | Control | 200.6 ± 68.8 | 213.9 ± 148.8 | 30 | 12.8 ± 123.5 | 37.5 (−4.5 to 79.5) | |

| LS | 196.7 ± 76.1 | 207.3 ± 72.8 | 33 | −2.2 ± 72.7 | 20.9 (−20.4 to 62.1) | 0.53 | |

| LBGI | 220.7 ± 126.5 | 210.4 ± 93.1 | 22 | −21 ± 108.4 | 22.8 (−26.4 to 72) | 0.61 | |

| SRGI | 194 ± 80 | 192.3 ± 84.6 | 27 | −9.1 ± 95.4 | 11.9 (−31.3 to 55) | 0.33 | |

| Total sugar (g/day) | Control | 84.1 ± 35.1 | 86.1 ± 44.6 | 30 | 0.5 ± 49.3 | 6 (−13.8 to 25.8) | |

| LS | 84.2 ± 41.9 | 87.2 ± 37.2 | 33 | −1.9 ± 41 | 1.7 (−17.9 to 21.3) | 0.74 | |

| LBGI | 88.3 ± 44 | 95.2 ± 62.6 | 22 | −4.3 ± 69.1 | 8.8 (−14.9 to 32.5) | 0.85 | |

| SRGI | 85.8 ± 49.1 | 85.5 ± 50.5 | 27 | −7.3 ± 60.7 | 2.1 (−18 to 22.2) | 0.76 | |

| Added sugar (g/day) | Control | 47.6 ± 28.7 | 49.8 ± 36 | 30 | 2 ± 42.5 | 8.6 (−6 to 23.3) | |

| LS | 44.8 ± 29.2 | 40.8 ± 29.6 | 33 | −5.3 ± 26.8 | −1.5 (−16 to 13) | 0.30 | |

| LBGI | 47.4 ± 38.4 | 47.7 ± 37.9 | 22 | −3.7 ± 57.4 | 0.8 (−16.7 to 18.3) | 0.46 | |

| SRGI | 47.6 ± 35 | 43.2 ± 42.5 | 27 | −4.1 ± 42.4 | 2.9 (−12 to 17.8) | 0.55 | |

| Soluble fiber (g/day) | Control | 4.9 ± 2.4 | 4.5 ± 3.8 | 30 | −0.5 ± 4 | 0.8 (−0.6 to 2.3) | |

| LS | 4.6 ± 2.6 | 4.8 ± 2.7 | 33 | −0.3 ± 2.8 | 0.4 (−1.1 to 1.9) | 0.66 | |

| LBGI | 4.8 ± 3 | 4.8 ± 2.4 | 22 | −0.1 ± 2.5 | 1.5 (−0.2 to 3.2) | 0.53 | |

| SRGI | 4.3 ± 2.6 | 5.3 ± 5.2 | 27 | 0.5 ± 6.1 | 1.2 (−0.3 to 2.7) | 0.74 | |

| Insoluble fiber (g/day) | Control | 9.4 ± 5.3 | 8.6 ± 5.3 | 30 | −1.2 ± 5.9 | −0.3 (−2.4 to 1.7) | |

| LS | 10.4 ± 6.5 | 10.8 ± 5.8 | 33 | −0.5 ± 4.7 | 0.3 (−1.7 to 2.4) | 0.63 | |

| LBGI | 9.6 ± 5.7 | 11.4 ± 6.2 | 22 | 1.2 ± 5.8 | 2.4 (0 to 4.9) | 0.06 | |

| SRGI | 8.7 ± 4.5 | 10.3 ± 6.4 | 27 | 0.8 ± 5.6 | 0.7 (−1.4 to 2.8) | 0.45 | |

| Total fiber (g/day) | Control | 14.3 ± 7.4 | 13.2 ± 8.8 | 30 | −1.7 ± 9.2 | 0.1 (−4.4 to 4.5) | |

| LS | 15.1 ± 8.9 | 15.7 ± 8.4 | 33 | −0.9 ± 7.1 | 0.4 (−3.4 to 4.3) | 0.86 | |

| LBGI | 14.5 ± 8.6 | 16.2 ± 8.4 | 22 | 1 ± 7.8 | 3.4 (−0.9 to 7.7) | 0.14 | |

| SRGI | 13 ± 6.6 | 15.8 ± 9.8 | 27 | 1.3 ± 9.8 | 1.5 (−2.6 to 5.6) | 0.49 | |

| Total protein (g/day) | Control | 64.5 ± 34.5 | 65.7 ± 61.6 | 31 | −1.3 ± 65.2 | 1.1 (−22.2 to 24.4) | |

| LS | 68.1 ± 35.1 | 73.7 ± 31.8 | 35 | 4.5 ± 31.6 | 5.9 (−13.8 to 25.6) | 0.64 | |

| LBGI | 65.2 ± 33.1 | 66.3 ± 28.4 | 24 | −3.9 ± 25.5 | 4.3 (−17.9 to 26.6) | 0.78 | |

| SRGI | 64.7 ± 28.6 | 70.3 ± 25.1 | 31 | −5.5 ± 35.7 | −3.8 (−24.9 to 17.4) | 0.63 | |

| Total fat (g/day) | Control | 56.7 ± 31.3 | 62.6 ± 70.5 | 31 | 7.3 ± 67.1 | 10.3 (−15.3 to 35.9) | |

| LS | 64.4 ± 37.7 | 62.1 ± 30.5 | 35 | −7.1 ± 34.6 | 3.1 (−18.8 to 25) | 0.53 | |

| LBGI | 64.2 ± 54.7 | 65.3 ± 37 | 24 | 2.3 ± 43.9 | 13.9 (−10.5 to 38.3) | 0.78 | |

| SRGI | 58.7 ± 32.3 | 55.9 ± 26.1 | 31 | −10.2 ± 33.6 | −4.6 (−28 to 18.7) | 0.19 | |

| Healthy Eating Index | Control | 50.9 ± 11.3 | 49.7 ± 10.2 | 31 | −2 ± 9.8 | −3.2 (−7.3 to 1) | |

| LS | 52 ± 10.1 | 54.7 ± 10.5 | 34 | 3.5 ± 11.6 | 3.5 (−0.6 to 7.6) | 0.02 | |

| LBGI | 49.9 ± 11.4 | 53.4 ± 10.2 | 23 | 2.5 ± 13.8 | 2 (−2.9 to 6.9) | 0.08 | |

| SRGI | 52.5 ± 10.5 | 53.4 ± 12 | 31 | −0.7 ± 13.8 | 0.3 (−3.8 to 4.4) | 0.19 | |

| Glycemic load | Control | 111.2 ± 41.9 | 120 ± 94.1 | 30 | 9.1 ± 77.6 | 25.9 (1.4 to 50.3) | |

| LS | 107.3 ± 43.1 | 111.3 ± 40.5 | 33 | −1.9 ± 42.1 | 12 (−12.1 to 36.2) | 0.39 | |

| LBGI | 123.9 ± 77.3 | 111 ± 49.9 | 22 | −17 ± 66.1 | 9 (−20.2 to 38.1) | 0.33 | |

| SRGI | 107.1 ± 43.5 | 100.6 ± 47.3 | 27 | −8.6 ± 53.1 | 5.6 (−19.5 to 30.6) | 0.20 | |

| Glycemic index | Control | 59.3 ± 4.1 | 58.5 ± 5 | 30 | −0.7 ± 6 | 0.6 (−1.4 to 2.6) | |

| LS | 58.9 ± 4.8 | 57.9 ± 4.5 | 33 | −0.2 ± 6.1 | 0 (−2 to 2) | 0.63 | |

| LBGI | 58.9 ± 4.8 | 57.2 ± 4.8 | 22 | −0.6 ± 6.4 | −1 (−3.4 to 1.4) | 0.26 | |

| SRGI | 59.3 ± 4.3 | 57.1 ± 5.4 | 27 | −1.4 ± 5.9 | −0.3 (−2.4 to 1.7) | 0.48 | |

| Physical activityc | |||||||

| Sedentary behavior (min/day) | Control | 1,085.5 ± 106 | 1,099.4 ± 122.4 | 40 | 18.7 ± 102 | 31.5 (−17 to 80) | |

| LS | 1,079.2 ± 100.2 | 1,084.1 ± 136.9 | 41 | −0.1 ± 101.2 | 13 (−35.5 to 61.4) | 0.54 | |

| LBGI | 1,053.3 ± 75 | 1,052.1 ± 204.6 | 34 | 7.4 ± 204.9 | −3.1 (−56.4 to 50.2) | 0.28 | |

| SRGI | 1,084 ± 114.2 | 1,061.8 ± 150.1 | 34 | 0.6 ± 129.8 | 3.5 (−45.9 to 52.9) | 0.37 | |

| Light activity (min/day) | Control | 21.6 ± 8.7 | 21.4 ± 12.3 | 40 | −1.2 ± 12.1 | 0.6 (−5.1 to 6.3) | |

| LS | 22.2 ± 7.6 | 21.8 ± 12.6 | 41 | −0.2 ± 12.2 | 1.6 (−3.6 to 6.7) | 0.71 | |

| LBGI | 24.4 ± 8.2 | 23.5 ± 13.1 | 34 | −1.8 ± 9.9 | 1.4 (−4.1 to 6.8) | 0.78 | |

| SRGI | 21.2 ± 6.9 | 24.1 ± 14.5 | 34 | 1.4 ± 15.1 | 2.7 (−2.7 to 8.2) | 0.42 | |

| Moderate activity (min/day) | Control | 52.4 ± 17.8 | 48 ± 20.7 | 40 | −6.6 ± 18.8 | −3.8 (−13.4 to 5.7) | |

| LS | 52.9 ± 13.4 | 50 ± 22.9 | 41 | −3.1 ± 18.2 | −0.2 (−8.9 to 8.5) | 0.40 | |

| LBGI | 59.1 ± 14.8 | 53.1 ± 23.2 | 34 | −7.7 ± 17.9 | −2.6 (−11.8 to 6.6) | 0.79 | |

| SRGI | 52 ± 17.6 | 53.5 ± 25.2 | 34 | −2.4 ± 24.3 | 0.3 (−8.9 to 9.4) | 0.36 | |

| Vigorous activity (min/day) | Control | 255.1 ± 86 | 225.6 ± 90.2 | 40 | −36.7 ± 63.8 | −29.5 (−68.1 to 9.1) | |

| LS | 257.4 ± 73.4 | 239.3 ± 95.6 | 41 | −21.2 ± 65.9 | −12.8 (−48 to 22.4) | 0.35 | |

| LBGI | 284.9 ± 54.8 | 243 ± 92.4 | 34 | −48.3 ± 86.5 | −29.5 (−66.9 to 7.9) | 0.99 | |

| SRGI | 261.3 ± 87 | 252.5 ± 107.2 | 34 | −29.8 ± 95.6 | −19.8 (−56.8 to 17.3) | 0.59 | |

| Moderate + vigorous activity (min/day) | Control | 307.5 ± 102.1 | 273.6 ± 108.4 | 40 | −43.3 ± 81.4 | −33.1 (−80.5 to 14.4) | |

| LS | 310.3 ± 84.9 | 289.4 ± 117.2 | 41 | −24.3 ± 82.2 | −12.7 (−56 to 30.7) | 0.35 | |

| LBGI | 344 ± 65.6 | 296 ± 112.8 | 34 | −56 ± 103.5 | −32.3 (−78.4 to 13.8) | 0.97 | |

| SRGI | 313.3 ± 103.5 | 306 ± 130.6 | 34 | −32.2 ± 118.5 | −19.2 (−64.7 to 26.4) | 0.53 | |

Difference score among participants with data for baseline and 3-month assessment. Participants' missing data for baseline and/or 3-month assessments are not included in the table.

Estimated marginal mean for change (difference score). Analyses nested in school. Adjusted for a priori covariates (baseline measurement, sex, Hispanic ethnicity, BMI, and year in study) and baseline characteristics, which were unbalanced between treatment groups (grade, age, and race).

Mean number of minutes per day across 7-day observation period.

BMI, body mass index; GI, guided imagery; LBGI, lifestyle behavior GI; LS, lifestyle education; SRGI, stress reduction GI.

Lifestyle behaviors: sensitivity analysis (adherent participants only)

Table 3 shows the post hoc sensitivity analysis of changes in dietary intake and physical activity outcomes from baseline to postintervention, performed only on those participants who achieved the adherence goal of attending 75% of all intervention sessions. Stepwise larger reductions in sedentary behavior were observed in LS (d = −0.41, p = 0.07), LBGI (d = −0.59, p = 0.04), and SRGI (d = −0.73, p = 0.004) compared with C (Fig. 2). Combined moderate + vigorous physical activity (MVPA) increased in the SRGI group (d = 0.58, p = 0.001 vs. C) and was also higher in LS (d = 0.36, p < 0.05) compared with C. Light physical activity was higher in SRGI versus C (d = 0.38, p = 0.03). The HEI improved in the LS and SRGI groups, with a moderate effect size compared with C. The glycemic index was significantly reduced in the LBGI group, with a large effect size (d = −0.84, p = 0.01), and showed a moderate effect size reduction in SRGI, although nonsignificant (d = −0.48, p = 0.12). There were no significant effects observed in the other dietary variables assessed.

Table 3.

Sensitivity Analysis of Dietary Intake and Physical Activity Outcomes

| Group | Baseline Mean ± SD | 3 Months Mean ± SD | n | Changea Mean ± SD | Estimated marginal Mean (95% CI)b | p-Value | Cohen's d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dietary intake | ||||||||

| Energy (kCal/day) | Control | 1,551.8 ± 617.7 | 1,671.6 ± 1,480.3 | 30 | 125.3 ± 1,338.9 | 49.1 (−344.5 to 442.8) | ||

| LS | 1,701.2 ± 778.5 | 1,732.8 ± 593.5 | 26 | −43.5 ± 626 | 26 (−399.1 to 451.2) | 0.93 | −0.02 | |

| LBGI | 1,718.6 ± 638.8 | 1,836.2 ± 780.4 | 13 | −69.8 ± 842.3 | 25.5 (−543.5 to 594.4) | 0.94 | −0.02 | |

| SRGI | 1,541.1 ± 692 | 1,502.9 ± 636.6 | 17 | −155.3 ± 741.2 | −202.5 (−701.5 to 296.5) | 0.39 | −0.24 | |

| Carbohydrate (g/day) | Control | 200.6 ± 68.8 | 214 ± 148.8 | 30 | 12.8 ± 123.5 | 7.5 (−30.9 to 45.9) | ||

| LS | 207.9 ± 81.6 | 216.9 ± 62.6 | 26 | −2.3 ± 68.6 | 1 (−40.4 to 42.4) | 0.81 | −0.06 | |

| LBGI | 225.1 ± 100.8 | 228.9 ± 100.6 | 13 | −21.8 ± 110.5 | −10.1 (−67.4 to 47.3) | 0.61 | −0.17 | |

| SRGI | 189.7 ± 87.6 | 195.4 ± 91.2 | 17 | −7.8 ± 96 | −12.4 (−62.2 to 37.4) | 0.51 | −0.19 | |

| Total sugar (g/day) | Control | 84.1 ± 35.1 | 86.1 ± 44.6 | 30 | 0.5 ± 49.3 | −4.3 (−21.6 to 12.9) | ||

| LS | 89.9 ± 41.8 | 93.7 ± 37.3 | 26 | −1.7 ± 41.5 | 0 (−18.4 to 18.5) | 0.73 | 0.09 | |

| LBGI | 92.9 ± 46.4 | 113.9 ± 71.6 | 13 | 9.2 ± 76.4 | 16.8 (−9.4 to 43) | 0.19 | 0.44 | |

| SRGI | 85.2 ± 52.6 | 87.6 ± 54.8 | 17 | −5.3 ± 59.1 | −5.2 (−27.9 to 17.6) | 0.95 | −0.02 | |

| Added sugar (g/day) | Control | 47.7 ± 28.7 | 49.8 ± 36 | 30 | 2 ± 42.5 | 0.4 (−12.8 to 13.7) | ||

| LS | 47 ± 29.8 | 42.6 ± 30.5 | 26 | −7.5 ± 29.3 | −7.4 (−21.6 to 6.8) | 0.42 | −0.22 | |

| LBGI | 45.6 ± 46.4 | 50.1 ± 45.3 | 13 | −6.2 ± 69.7 | −1.4 (−21.6 to 18.8) | 0.88 | −0.05 | |

| SRGI | 42.4 ± 34.2 | 43.2 ± 42.5 | 17 | −5.3 ± 43.7 | −6.4 (−24 to 11.3) | 0.54 | −0.19 | |

| Soluble fiber (g/day) | Control | 4.9 ± 2.4 | 4.5 ± 3.8 | 30 | −0.5 ± 4 | −0.4 (−1.9 to 1) | ||

| LS | 4.7 ± 2.8 | 5 ± 2.4 | 26 | 0 ± 2.8 | 0 (−1.5 to 1.6) | 0.65 | 0.12 | |

| LBGI | 5.3 ± 2.4 | 5.5 ± 2.8 | 13 | 0.2 ± 2.9 | 0.4 (−1.8 to 2.6) | 0.53 | 0.21 | |

| SRGI | 3.9 ± 2.7 | 6.3 ± 6.4 | 17 | 1.9 ± 7.1 | 1.5 (−0.5 to 3.4) | 0.12 | 0.48 | |

| Insoluble fiber (g/day) | Control | 9.4 ± 5.3 | 8.6 ± 5.4 | 30 | −1.2 ± 5.9 | −1.6 (−3.3 to 0.2) | ||

| LS | 11 ± 6.7 | 11.5 ± 4.8 | 26 | −0.3 ± 4.9 | 0.3 (−1.6 to 2.1) | 0.16 | 0.38 | |

| LBGI | 11 ± 4.8 | 12.5 ± 6.7 | 13 | 1.2 ± 6.7 | 1.5 (−1.1 to 4.1) | 0.06 | 0.64 | |

| SRGI | 8.6 ± 5.7 | 10.7 ± 6.1 | 17 | 1.1 ± 4.7 | 0.6 (−1.7 to 2.9) | 0.13 | 0.46 | |

| Total fiber (g/day) | Control | 14.3 ± 7.4 | 13.2 ± 8.8 | 30 | −1.7 ± 9.2 | −2.1 (−5 to 0.8) | ||

| LS | 15.8 ± 9.4 | 16.6 ± 7 | 26 | −0.5 ± 7.3 | 0.2 (−2.9 to 3.3) | 0.29 | 0.28 | |

| LBGI | 16.4 ± 6.8 | 18 ± 9.3 | 13 | 1.2 ± 9 | 1.7 (−2.7 to 6.1) | 0.15 | 0.48 | |

| SRGI | 12.7 ± 8 | 17.1 ± 10.5 | 17 | 3 ± 10.7 | 2.2 (−1.7 to 6) | 0.08 | 0.53 | |

| Total protein (g/day) | Control | 64.5 ± 34.5 | 65.7 ± 61.6 | 31 | −1.3 ± 65.2 | 2 (−26.4 to 30.3) | ||

| LS | 71.4 ± 37.7 | 78.3 ± 29.5 | 28 | 4.6 ± 32.7 | 7.6 (−18.3 to 33.5) | 0.64 | 0.08 | |

| LBGI | 72.8 ± 30.2 | 71.1 ± 30.8 | 13 | −8.4 ± 23 | 6.9 (−26.4 to 40.2) | 0.74 | 0.07 | |

| SRGI | 70.4 ± 34.6 | 68.1 ± 21.7 | 19 | −6.5 ± 34.5 | −4.7 (−32.7 to 23.4) | 0.60 | −0.09 | |

| Total fat (g/day) | Control | 56.7 ± 31.3 | 62.6 ± 70.5 | 31 | 7.3 ± 67.1 | 19.6 (−11.6 to 50.9) | ||

| LS | 66.8 ± 43.3 | 64.7 ± 30.6 | 28 | −6.9 ± 33.8 | 12 (−16.9 to 40.8) | 0.58 | −0.09 | |

| LBGI | 61 ± 24.2 | 74.3 ± 46.8 | 13 | 6.9 ± 54.1 | 31.7 (−4.5 to 68) | 0.47 | 0.16 | |

| SRGI | 57.5 ± 32.8 | 52.6 ± 28.1 | 19 | −10.6 ± 33.3 | 1.4 (−29.7 to 32.5) | 0.21 | −0.23 | |

| Healthy Eating Index | Control | 50.9 ± 11.4 | 49.7 ± 10.2 | 31 | −2 ± 9.8 | −2.7 (−6.7 to 1.4) | ||

| LS | 52.1 ± 9.6 | 55.9 ± 9.9 | 27 | 4.5 ± 11.6 | 4 (−0.3 to 8.4) | 0.02 | 0.59 | |

| LBGI | 53.4 ± 13.2 | 53.8 ± 11.4 | 13 | 1.7 ± 16.9 | 1.4 (−4.6 to 7.3) | 0.26 | 0.36 | |

| SRGI | 54.5 ± 10 | 56.1 ± 12.8 | 19 | 1.1 ± 15.3 | 3.4 (−1.7 to 8.4) | 0.05 | 0.54 | |

| Glycemic load | Control | 111.3 ± 41.9 | 120 ± 94.1 | 30 | 9.1 ± 77.6 | 6.6 (−17 to 30.1) | ||

| LS | 112.7 ± 45.4 | 116.6 ± 35.8 | 26 | −2 ± 37.7 | −0.8 (−26.2 to 24.7) | 0.66 | −0.11 | |

| LBGI | 121.9 ± 62.7 | 116.6 ± 55.9 | 13 | −21.8 ± 69.1 | −15.9 (−51.1 to 19.2) | 0.29 | −0.35 | |

| SRGI | 104.5 ± 49 | 100.9 ± 50.7 | 17 | −10.5 ± 53.9 | −12.5 (−43.1 to 18) | 0.30 | −0.30 | |

| Glycemic index | Control | 59.3 ± 4.1 | 58.6 ± 5 | 30 | −0.7 ± 6 | −0.3 (−2 to 1.3) | ||

| LS | 58.6 ± 4.5 | 58.4 ± 4.3 | 26 | −0.1 ± 5.8 | −0.2 (−2 to 1.5) | 0.95 | 0.02 | |

| LBGI | 57.4 ± 5.3 | 54.4 ± 3.5 | 13 | −3.7 ± 5.6 | −4.1 (−6.7 to −1.6) | 0.01 | −0.84 | |

| SRGI | 58.5 ± 5 | 56.1 ± 4.3 | 17 | −2.4 ± 5.6 | −2.5 (−4.7 to −0.3) | 0.12 | −0.48 | |

| Physical activityc | ||||||||

| Sedentary behavior (min/day) | Control | 1,085.5 ± 106 | 1,099.4 ± 122.4 | 40 | 18.7 ± 102.1 | 22.1 (−16.7 to 61) | ||

| LS | 1,063.4 ± 79.9 | 1,043.2 ± 108.5 | 30 | −25 ± 97.2 | −27.6 (−71.5 to 16.3) | 0.07 | −0.41 | |

| LBGI | 1,022.3 ± 66.4 | 985.4 ± 165.4 | 17 | −39.3 ± 168.1 | −48.9 (−105.3 to 7.5) | 0.04 | −0.59 | |

| SRGI | 1,047.9 ± 81.3 | 989 ± 95.1 | 21 | −64 ± 88.8 | −65.5 (−116.4 to −14.6) | 0.004 | −0.73 | |

| Light activity (min/day) | Control | 21.6 ± 8.7 | 21.4 ± 12.3 | 40 | −1.2 ± 12.1 | −1.8 (−8.2 to 4.7) | ||

| LS | 22.8 ± 5.1 | 23.9 ± 12.5 | 30 | 1.6 ± 12 | 2.6 (−3.7 to 8.9) | 0.14 | 0.23 | |

| LBGI | 28.5 ± 10.5 | 27.9 ± 12.7 | 17 | −0.8 ± 9.1 | 0.6 (−7.1 to 8.3) | 0.51 | 0.13 | |

| SRGI | 22.9 ± 5.2 | 30.6 ± 13.9 | 21 | 7.5 ± 15.7 | 5.2 (−1.6 to 11.9) | 0.03 | 0.38 | |

| Moderate activity (min/day) | Control | 52.4 ± 17.8 | 48 ± 20.7 | 40 | −6.6 ± 18.8 | −7.5 (−17.2 to 2.2) | ||

| LS | 55.3 ± 9.4 | 55.2 ± 20.6 | 30 | 0 ± 18.3 | 2.3 (−7.2 to 11.8) | 0.03 | 0.34 | |

| LBGI | 66.7 ± 14.6 | 62.6 ± 18.6 | 17 | −4.4 ± 12.6 | −2.6 (−14.3 to 9) | 0.37 | 0.18 | |

| SRGI | 56.3 ± 14.1 | 65.8 ± 18.9 | 21 | 9.3 ± 21.2 | 7.1 (−3.1 to 17.3) | 0.003 | 0.53 | |

| Vigorous activity (min/day) | Control | 255.1 ± 86 | 225.6 ± 90.2 | 40 | −36.7 ± 63.8 | −44.2 (−78.9 to −9.4) | ||

| LS | 271.4 ± 60.7 | 266.2 ± 73.8 | 30 | −10.3 ± 65.7 | −7.4 (−41.4 to 26.5) | 0.03 | 0.36 | |

| LBGI | 298.4 ± 40.1 | 278.2 ± 64.7 | 17 | −19.4 ± 56.8 | −24 (−65.4 to 17.4) | 0.28 | 0.20 | |

| SRGI | 279.9 ± 64.4 | 297.8 ± 66.9 | 21 | 19.6 ± 59.6 | 13.3 (−23.3 to 49.8) | 0.001 | 0.58 | |

| Moderate + vigorous activity (min/day) | Control | 307.5 ± 102.1 | 273.6 ± 108.4 | 40 | −43.3 ± 81.4 | −51.6 (−95.3 to −7.8) | ||

| LS | 326.7 ± 67.8 | 321.4 ± 92.9 | 30 | −10.3 ± 82.1 | −4.9 (−47.5 to 37.8) | 0.02 | 0.36 | |

| LBGI | 365.2 ± 46.7 | 340.8 ± 76.5 | 17 | −23.8 ± 68.2 | −27.1 (−79.2 to 25) | 0.30 | 0.20 | |

| SRGI | 336.2 ± 77.2 | 363.6 ± 82.6 | 21 | 28.9 ± 79.3 | 20.6 (−25.3 to 66.6) | 0.001 | 0.58 | |

Difference score among participants with data for baseline and 3-month assessment. Participants' missing data for baseline and/or 3-month assessments are not included in the table.

Estimated marginal mean for change (difference score). Analyses nested in school. Adjusted for a priori baseline measurement.

Mean number of minutes per day across 7-day observation period.

GI, guided imagery; LBGI, lifestyle behavior GI; LS, lifestyle education; SRGI, stress reduction GI.

FIG. 2.

Changes in sedentary behavior and physical activity. Bars depict mean ± 95% confidence interval. p-Value versus Control: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01. GI, guided imagery; LBGI, lifestyle behavior GI; LS, lifestyle education; SRGI, stress reduction GI.

Adverse events

The intervention was well tolerated with relatively few adverse events, only four of which were categorized as serious adverse events (one event each of pain in hands and feet, appendicitis, torn knee ligament, and suicidal ideation), none of which were deemed related to the protocol.

Discussion

The Imagine HEALTH intervention sought to determine the effects of group GI added to a didactic, health-promoting lifestyle curriculum, with primary outcomes of physical activity behaviors, while also assessing dietary intake. To the best of the authors' knowledge, this is the first fully powered RCT lifestyle intervention studying the effect of GI on obesity-related lifestyle behaviors in an adolescent population. There is also little to no literature on the uses, acceptability, and cultural relevance of GI in a Latinx adolescent population beyond the authors' prior studies, which demonstrated feasibility, acceptability, and efficacy in this population despite their being mostly naive to mind–body modalities.11,21 The relaxation and positive imagery that is encompassed in GI is thought to attenuate psychoneuroendocrine pathways that affect the stress response.28 Beyond stress reduction, GI and related mind–body therapies have also been used to promote behavior change in adults with eating disorders and obesity.29–31 The authors reasoned that GI may offer a developmentally appropriate behavioral therapy in teens, in that it involves affective components known to influence adolescent behaviors, as well as elements of mindfulness.32–35

The ITT analysis showed no group differences in sedentary behavior or physical activity and showed significant improvement in the HEI only in the LS education group. Therefore, the primary analysis did not support the hypothesis that GI would augment intervention effects on obesity-related lifestyle behaviors. The nutrition curriculum focused on improving carbohydrate quality8,36 from simple, refined sugars to complex carbohydrates and fiber, which has demonstrable health benefits for Latinx teens,16,37 combined with the process of intuitive eating,20 and is fully consistent with pediatric and adolescent dietary guidelines.13 Intuitive eating promotes a healthy nonrestrictive relationship with food through the utilization of hunger and fullness cues and promoting eating satisfaction,20 and studies have linked it to good health outcomes in young adults.18,19 To the best of the authors' knowledge, this is the first time intuitive eating has been used in a specific lifestyle intervention, although the similar concept of mindfulness-based eating has been used successfully in dietary interventions in adults.38,39 The present study design does not allow us to determine which specific intervention components mediated the change seen in the HEI, but supports future research to determine the specific effects of these approaches to healthy eating in adolescent populations.

The sensitivity analysis, showing additional positive lifestyle behavior changes for adherent participants, suggests that poor adherence obscured potential benefits of this intervention. The findings of decreased sedentary behavior and increased MVPA are consistent with the pilot findings using individualized (i.e., nongroup) GI.11 The greatest decrease in sedentary activity and increase in MVPA were observed in the SRGI group, conforming to the hypothesis that GI would augment the outcomes occurring from didactic lifestyle education alone, but in contrast to the expectation that the LBGI intervention would be the most efficacious. This suggests that the LBGI imagery content meant to promote healthy dietary and physical activity behaviors may be overly complex and more difficult to deliver in group than the more straightforward SRGI. The nonspecific effect of SRGI on lifestyle behaviors may have been achieved by teaching teens a way to balance and center that could subsequently lead to improved real-time behavior choices, or improved attention to the didactic education elements of the program. This is important in considering future interventions since in our experience SRGI was easier to conceptualize and deliver than the LBGI curriculum and represents a therapeutic modality that can potentially be learned and used relatively easily by primary care providers to augment conventional allopathic practices.

In terms of dietary outcomes, the sensitivity analysis replicated the ITT finding of improvement in the HEI in the LS group, without an additional effect from the GI. GI did decrease the glycemic index in the LBGI group (large effect, d = 0.84) and the SRGI group (moderate effect, d = 0.48), without change in the LS group. This could be important since a low glycemic index diet has been effective in both adolescents with obesity9 and adults with diabetes,40,41 and future work could seek to confirm this finding.

Participant adherence was suboptimal in all intervention groups. Thus, a majority of the participants did not receive the intended “dose” of intervention, limiting the capacity to interpret negative findings. This occurred despite our: (1) recognizing this challenge in an adolescent study population facing a high study burden; (2) substantial efforts to boost attendance throughout the conduct of the intervention; and (3) pilot intervention suggesting that we would be able to meet adherence goals.21 However, the pilot was limited to 6 weeks, and in the current study, the authors clearly saw a drop in attendance in the latter half of the full 12-week intervention. The interactions with participants did not suggest that this was due to loss of interest in the intervention in these latter weeks, but was rather linked to increasing intensity of school demands and approaching final examinations toward the end of the intervention. Changes in the future to improve adherence could include limiting the program to a maximum of two afternoons a week, supported by the higher adherence rate in the LS group (two sessions per week versus three sessions per week in SRGI and LBGI), shortening the intervention to 6–8 weeks, delivering the intervention during required classroom time, or delivering parts of the intervention remotely using technological platforms. Beyond the poor adherence issue to explain the modest findings of lifestyle behavior change in the ITT analysis immediately upon completing the intervention, it may be that effects may yet be seen after a longer period of time, as other lifestyle intervention studies in adolescents have shown changes only after 6–12 months of intervention.36,10,42,43

Strengths of this study include the fact that this was a well-designed RCT using a mind–body modality in a highly innovative, safe, lifestyle intervention. The authors worked with a greatly understudied adolescent population subjected to great health disparities and approached the intervention from the standpoint of promoting healthy lifestyle behaviors in a population of youth of all body sizes. The authors utilized robust study methodologies and recruitment procedures, which included collaboration with outside community groups and the local school district to deliver the intervention, along with rigorous outcome measures (accelerometry and multiple dietary recalls).12 The primary limitation of the study was the poor participant adherence, thereby limiting the degree to which conclusions can be made regarding the effectiveness of GI in this study. Generalizability of results is uncertain beyond the predominantly Latinx, lower socioeconomic, adolescent study population. Finally, although physical activity was objectively measured using wrist-worn accelerometers, interpreting the results by the absolute amount may be misleading, given the challenges related to the accuracy of classifying data from wrist-worn accelerometer collected in free-living environment.44 Therefore, the current study interpreted the findings in terms of the magnitude of change before and after the intervention.

In conclusion, the Imagine HEALTH lifestyle intervention did not show an effect of GI on lifestyle behaviors in the primary ITT analysis. Subsequent post hoc analyses of adherent participants did suggest that GI can amplify the role of didactic lifestyle education for sedentary behavior and physical activity. Future attempts at similar interventions must account for the difficulties encountered in delivering such a complex holistic intervention to an adolescent population.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the collaboration of the nonprofit group SOS-Mentor and their commitment to improving eating and exercise behaviors among youth, the administration, and staff of the involved high schools and LA Unified School District, and the nutrition departments of Pepperdine College and California State University Los Angeles. The authors are grateful to their hardworking research staff and the many students at all academic levels who took part in this work. The authors would especially like to thank the students who took part in this study, and their families, for their participation and for teaching us so much.

Authors' Contributions

All coauthors have reviewed and approved the article before submission. M.J.W.: Study conceptualization/design; methodology; investigation; supervision; funding acquisition; drafting initial article; review/editing article. Q.A.: Investigation; supervision; funding acquisition; review/editing article. D.S.-M.: Study conceptualization/design; methodology; investigation; supervision; funding acquisition; review/editing article. J.N.D.: Methodology; supervision; review/editing article. C.K.F.W.: Methodology; investigation; supervision; drafting initial article; review/editing article. K.G. and M.P.: Investigation; review/editing article. N.B.W.: Data curation; formal analysis; drafting initial article. L.D.: Data curation; formal analysis; review/editing article. C.J.L.: Data curation; formal analysis; drafting initial article; review/editing article.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Funding Information

This work was sponsored by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health, R01AT008330, and supported by grants UL1TR001855 and UL1TR000130 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Science (NCATS) of the U.S. NIH. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Lawman HG, et al. Trends in obesity prevalence among children and adolescents in the United States, 1988–1994 through 2013–2014. JAMA 2016;315:2292–2299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Goran MI, Bergman RN, Avila Q, et al. Impaired glucose tolerance and reduced beta-cell function in overweight Latino children with a positive family history for type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2004;89:207–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Weigensberg MJ, Ball GD, Shaibi GQ, et al. Decreased beta-cell function in overweight Latino children with impaired fasting glucose. Diabetes Care 2005;28:2519–2524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Toledo-Corral CM, Vargas LG, Goran MI, Weigensberg MJ. Hemoglobin A1c above threshold level is associated with decreased β-cell function in overweight Latino youth. J Pediatr 2012;160:751–756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cruz ML, Shaibi GQ, Weigensberg MJ, et al. Pediatric obesity and insulin resistance: Chronic disease risk and implications for treatment and prevention beyond body weight modification. Annu Rev Nutr 2005;25:435–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Haffner SM, Miettinen H, Gaskill SP, Stern MP. Decreased insulin action and insulin secretion predict the development of impaired glucose tolerance. Diabetologia 1996;39:1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Shaibi GQ, Ball G, Weigensberg MJ, et al. Effects of resistance training on insulin sensitivity in overweight Hispanic adolescent males. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2006;38:1208–1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Davis J, Ventura E, Shaibi G, et al. Reduction in added sugar intake and improvement in insulin secretion in overweight Latina adolescents. Metab Syndr Relat Disord 2007;5:183–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ebbeling C, Leidig M, Sinclair K, et al. A reduced-glycemic load diet in the treatment of adolescent obesity. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2003;157:773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ebbeling CB, Feldman HA, Chomitz VR, et al. A randomized trial of sugar-sweetened beverages and adolescent body weight. N Engl J Med 2012;367:1407–1416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Weigensberg MJ, Lane CJ, Ávila Q, et al. Imagine HEALTH: Results from a randomized pilot lifestyle intervention for obese Latino adolescents using Interactive Guided ImagerySM. BMC Complement Altern Med 2014;14:28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Weigensberg MJ S-MD, Wen CKF, Davis JN, et al. Protocol for the Imagine HEALTH study: Guided imagery lifestyle intervention to improve obesity-related behaviors and salivary cortisol patterns in predominantly Latino adolescents. Contemp Clin Trials 2018;72:103–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gidding S, Dennison B, Birch L, et al. Dietary recommendations for children and adolescents: A guide for practitioners: Consensus statement from the American Heart Association. Am Heart Assoc 2005;112:2061–2075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lichtenstein A, Appel L, Brands M, et al. Diet and lifestyle recommendations revision 2006: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association Nutrition Committee. Circulation 2006;114:82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Barlow S. Expert committee recommendations regarding the prevention, assessment, and treatment of child and adolescent overweight and obesity: Summary report. Pediatrics 2007;120(Supplement):S164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Davis J, Kelly L, Lane C, et al. Randomized control trial to improve adiposity and insulin resistance in overweight Latino adolescents. Obesity 2009;17:1542–1548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hasson RE, Adam TC, Davis JN, et al. Randomized controlled trial to improve adiposity, inflammation, and insulin resistance in obese African American and Latino youth. Obesity 2012;20:811–818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hawks SR, Madanat HN, Merrill RM. The intuitive eating scale: Development and preliminary validation. Am J Health Educ 2004;35:90–99. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tylka TL. Development and psychometric evaluation of a measure of intuitive eating. J Couns Psychol 2006;53:226–240. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tribole E, Resch E. Intuitive Eating, Third edition. New York: St. Martins Press, 2012. (First edition 1995). [Google Scholar]

- 21. Weigensberg MJ, Provisor J, Spruijt-Metz D, et al. Guided imagery council: Feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary effects of a novel group-based lifestyle intervention in predominantly Latino adolescents. Glob Adv Health Med 2019;8:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Choi L, Ward SC, Schnelle JF, Buchowski MS. Assessment of wear/nonwear time classification algorithms for triaxial accelerometer. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2012;44:2009–2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chandler JL, Brazendale K, Beets MW, Mealing BA. Classification of physical activity intensities using a wrist-worn accelerometer in 8-12-year-old children. Pediatr Obes 2016;11:120–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. National Coordinating Center. Nutrition Data System for Research (NDSR). Program 2.9, food Databse 11A, Nurient Database S26 ed. Minnesota: University of Minnesota, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Johnson RK, Driscoll P, Goran MI. Comparison of multiple-pass 24-hour recall estimates of energy intake with total energy expenditure determined by the doubly labeled water method in young children. J Am Diet Assoc 1996;96:1140–1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. U.S. Department of Agriculture. How the HEI is scored. Online document at: https://www.fns.usda.gov/how-hei-scored, accessed April 26, 2021.

- 27. Reedy J, Lerman JL, Krebs-Smith SM, et al. Evaluation of the healthy eating index-2015. J Acad Nutr Diet 2018;118:1622–1633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hart J. Guided imagery. Altern Complement Ther 2008;14:295–299. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Esplen MJ, Garfinkel PE, Olmsted M, et al. A randomized controlled trial of guided imagery in bulimia nervosa. Psychol Med 1998;28:1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kristeller JL, Hallett C. An exploratory study of a meditation-based intervention for binge eating disorder. J Health Psychol 1999;4:357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pawlow LA, O'Neil PM, Malcolm RJ. Night eating syndrome: Effects of brief relaxation training on stress, mood, hunger, and eating patterns. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2003;27:970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Naparstek B. Staying Well with Guided Imagery. New York, NY: Warner Books Edition, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Spruijt-Metz D. Adolescence, Affect and Health. East Sussex, United Kingdom: Psychology Press Ltd., 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Radzik M, Sherer S, Neinstein LS. Psychosocial development in normal adolescents. In: Neinstein LS, Gordon KM, Katzman DK, Rosen DS, Woods ER, eds. Adolescent Healthcare. Vol. 4. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, 2002:52. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Spruijt-Metz D, Gallaher P, Unger J, Anderson CA. Meanings of smoking and adolescent smoking across ethnicities. J Adolesc Health 2004;35:197–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Davis J, Ventura E, Tung A, et al. Effects of a randomized maintenance intervention on adiposity and metabolic risk factors in overweight minority adolescents. Pediatr Obes 2012;7:16–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ventura E, Davis J, Byrd-Williams C, et al. Reduction in risk factors for type 2 diabetes mellitus in response to a low-sugar, high-fiber dietary intervention in overweight Latino adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2009;163:320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Daubenmier J, Kristeller J, Hecht FM, et al. Mindfulness intervention for stress eating to reduce cortisol and abdominal fat among overweight and obese women: An exploratory randomized controlled study. J Obes 2011;2011:651936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kristeller JL, Wolever RQ. Mindfulness-based eating awareness training for treating binge eating disorder: The conceptual foundation. Eating Disord 2010;19:49–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Zafar MI, Mills KE, Zheng J, et al. Low-glycemic index diets as an intervention for diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr 2019;110:891–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Augustin LS, Kendall CW, Jenkins DJ, et al. Glycemic index, glycemic load and glycemic response: An International Scientific Consensus Summit from the International Carbohydrate Quality Consortium (ICQC). Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2015;25:795–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Savoye M, Shaw M, Dziura J, et al. Effects of a weight management program on body composition and metabolic parameters in overweight children: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2007;297:2697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Neumark-Sztainer DR, Friend SE, Flattum CF, et al. New moves‚Äîpreventing weight-related problems in adolescent girls: A group-randomized study. Am J Prev Med 2010;39:421–432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kerr J, Marinac CR, Ellis K, et al. Comparison of accelerometry methods for estimating physical activity. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2017;49:617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.