Abstract

Background: BRAFV600E acts as an ATP-dependent cytosolic kinase. BRAFV600E inhibitors are widely available, but resistance to them is widely reported in the clinic. Lipid metabolism (fatty acids) is fundamental for energy and to control cell stress. Whether and how BRAFV600E impacts lipid metabolism regulation in papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC) is still unknown. Acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC) is a rate-limiting enzyme for de novo lipid synthesis and inhibition of fatty acid oxidation (FAO). ACC1 and ACC2 genes encode distinct isoforms of ACC. The aim of our study was to determine the relationship between BRAFV600E and ACC in PTC.

Methods: We performed RNA-seq and DNA copy number analyses in PTC and normal thyroid (NT) in The Cancer Genome Atlas samples. Validations were performed by using assays on PTC-derived cell lines of differing BRAF status and a xenograft mouse model derived from a heterozygous BRAFWT/V600E PTC-derived cell line with knockdown (sh) of ACC1 or ACC2.

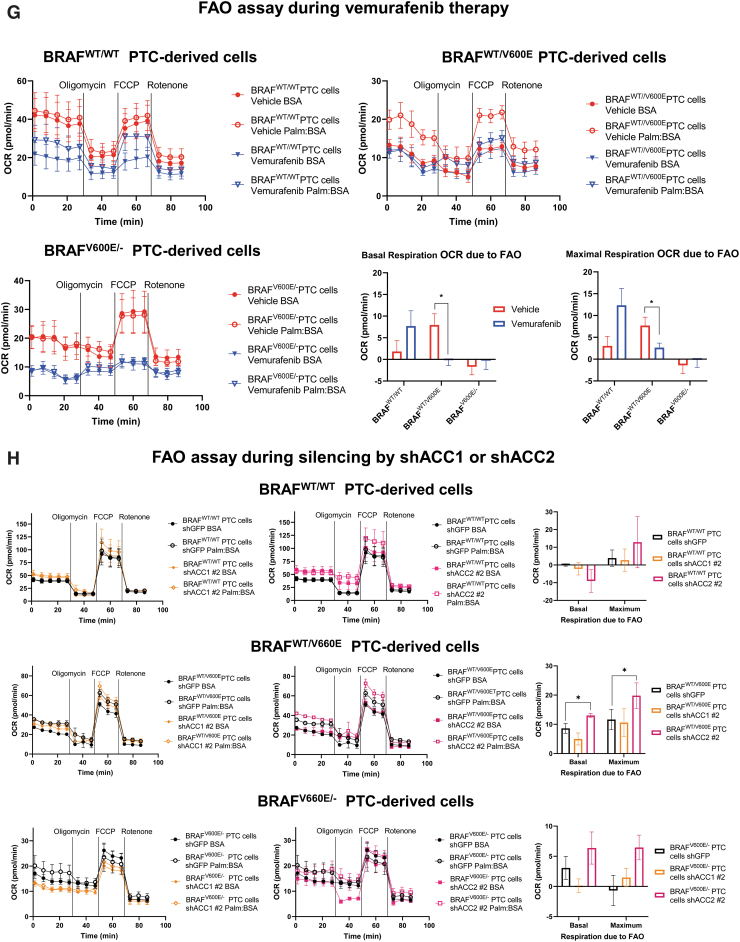

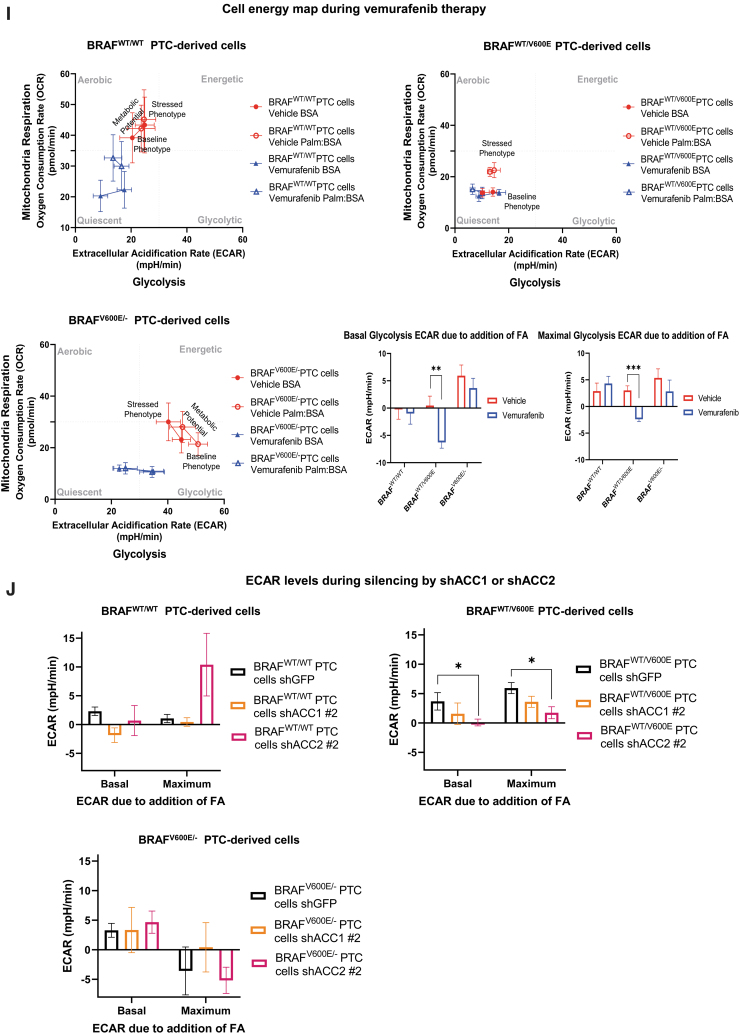

Results: ACC2 mRNA expression was significantly downregulated in BRAFV600E-PTC vs. BRAFWT-PTC or NT clinical samples. ACC2 protein levels were downregulated in BRAFV600E-PTC cell lines vs. the BRAFWT/WT PTC cell line. Vemurafenib increased ACC2 (and to a lesser extent ACC1) mRNA levels in PTC-derived cell lines in a BRAFV600E allelic dose-dependent manner. BRAFV600E inhibition increased de novo lipid synthesis rates, and decreased FAO due to oxygen consumption rate (OCR), and extracellular acidification rate (ECAR), after addition of palmitate. Only shACC2 significantly increased OCR rates due to FAO, while it decreased ECAR in BRAFV600E PTC-derived cells vs. controls. BRAFV600E inhibition synergized with shACC2 to increase intracellular reactive oxygen species production, leading to increased cell proliferation and, ultimately, vemurafenib resistance. Mice implanted with a BRAFWT/V600E PTC-derived cell line with shACC2 showed significantly increased tumor growth after vemurafenib treatment, while vehicle-treated controls, or shGFP control cells treated with vemurafenib showed stable tumor growth.

Conclusions: These findings suggest a potential link between BRAFV600E and lipid metabolism regulation in PTC. BRAFV600E downregulates ACC2 levels, which deregulates de novo lipid synthesis, FAO due to OCR, and ECAR rates. ShACC2 may contribute to vemurafenib resistance and increased tumor growth. ACC2 rescue may represent a novel molecular strategy for overcoming resistance to BRAFV600E inhibitors in refractory PTC.

Keywords: BRAFV600E, ACC1; ACC2; fatty acid synthesis; beta-oxidation; vemurafenib; ROS; mitochondria; seahorse; de novo lipid synthesis

Introduction

The lack of effective treatments for aggressive papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC) represents an unmet clinical need, especially given its rising incidence (1). PTC is the histological type of cancer with the highest frequency (2), and BRAFV600E is the most prevalent mutation driving cancer initiation and progression of PTC (3), while also correlating with increased mortality risk (4) and more aggressive clinic-pathological features with a higher probability of standard therapy failure (5). In 2011, the US Food and Drug Administration approved the first BRAFV600E inhibitor, vemurafenib, but unfortunately, resistance to this targeted therapy is widely reported in patients who initially responded (6). Our understanding of the molecular processes that allow BRAFV600E-positive tumors (including melanoma, colorectal adenocarcinoma, PTC, anaplastic thyroid carcinoma [ATC]) to develop resistance to BRAFV600E inhibitors (including vemurafenib) has advanced in recent years, and many studies have described several mechanisms: over-activation of the PI3K-AKT pathway due to increased c-MET expression (7); invasive processes resulting from epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (8); focal amplifications of chromosome 6, with a minimal region of overlap that includes Met (9); aberrant HER3 overexpression mediated by autocrine loop signaling (10); autocrine interleukin-6 secretion via JAK/STAT3 and the MAPK pathway (11); persistent formation of the eIF4F complex (12); persistent activation of mTOR and hyperactive ERK signaling (13); expression of the BRAFV600E splicing isoform (14); BRAFV600E/K amplifications and non-MAPK alterations (15); ER stress response–mediated autophagy (16); copy number gain of MCL1 and loss of CDKN2A (P16) (17), also showing that CDK4/6 inhibitors, which mimic P16 function, in combination with vemurafenib induced apoptosis in PTC and ATC cells (18); and tetraploidization and amplification of chromosome 5 via mutations in the RNA-binding motifs (RBM) genes family (i.e., RBMX, RBM10) (18). Further, our recent studies of the tumor microenvironment showed that pericytes play an essential role in protecting human thyroid cancer cells from vemurafenib, sorafenib (a tyrosine kinase inhibitor), and combination therapy via TSP-1/TGFβ1 axis (19).

Researchers have begun to devote greater attention to deregulations in cell metabolism, among other hallmarks of cancer (20), to better understand the complexity of tumor biology, and several studies have already shed light on crucial metabolic aspects of various neoplasias (21). However, thyroid cancer metabolism remains poorly characterized, with very few studies focusing on the aerobic glycolytic phenotype or the role(s) of glutamine/amino acids (8) or the metabolic switch to glycolysis driven by PI3K (22). Moreover, lipid metabolism is fundamental for energy and makes available the reducing equivalents that control intracellular (23–26) and microenvironment (27) stress, which may lead to tumor survival (28). Intriguingly, obesity (a multifactorial metabolic disease) is positively associated with greater frequency and higher mortality in thyroid cancer (1,29), but the biological mechanisms underlying these outcomes are completely unknown. One study reported lower lipid levels in thyroid lesions compared with normal thyroid (NT) tissue (30), but it did not detail tumor histotype or genetic events.

Whether and how the BRAFV600E oncogene impacts lipid metabolism regulation in thyroid cancer remains unknown. Acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC) is the rate-limiting enzyme that catalyzes the first committed step in fatty acid synthesis (FAS, which yields derived lipids), the ATP-dependent carboxylation of acetyl-CoA, which produces malonyl-CoA (31,32). Malonyl-CoA is the substrate for fatty acid synthase and is also an allosteric inhibitor of CPT1, the fatty acid transporter in the mitochondria that initiates fatty acid oxidation (FAO) (33); therefore, it is also crucial in regulating FAO. Humans (34) and other mammals have two paralogous genes encoding ACC: ACACA (ACCα or ACC1) and ACACB (ACCβ or ACC2), which are located on different chromosomes (17 and 12, respectively) and are believed to have originated from an ancestral gene duplication (33). Both ACCs belong to the biotin carboxylase protein family, and their enzymatic structure is well conserved, although they differ in N-terminal sequence (33), tissue-specific expression (34), and biological functions (35). ACC1 is primarily expressed in lipogenic tissue, such as liver and adipose (34), and produces malonyl-CoA which is directed to FAS; while ACC2 is prevalent in the heart and skeletal muscle (34), and it inhibits FAO. ACC2 is localized at the outer membrane of mitochondria (36), via its N-terminal sequence (37), while ACC1 is cytosolic. Indeed, the putative role of ACC2 is the inhibition of CPT1 (35), and it therefore performs a different function from ACC1. ACC1 and ACC2 also share post-translational modulation by phosphorylation and subsequent inactivation in two critical serine residues (Ser78 and Ser80 of human ACC1, Ser219 Ser221 of human ACC2) (38,39). AMP-activated kinase (AMPK), a well-described regulator, phosphorylates both ACC proteins (40), and is upstream-regulated by LKB1. Although the LKB1-AMPK axis has been generally described as tumor suppressive (41), AMPK activity as an energy sensor has conversely been shown to be useful to cancer cells in detecting metabolic stress (25). Transcription of ACC genes is mainly regulated by the sterol regulatory element-binding protein (SREBP-1) (42,43), which belongs to a family of helix-loop-helix-leucine zipper transcription factors. Increased de novo lipogenesis and reduced FAO may disturb different metabolic mechanisms and contribute to obesity. ACCs are considered drug targets for obesity, diabetes, and metabolic syndromes (44,45). Their modulation in tumors is more complex: ACC1 is upregulated in different tumor types (46,47), including nonsmall cell lung cancer (48). Conversely, ACC2 expression and/or activation are inhibited in tumors (49,50). ACC2 is stabilized and activated by PHD3 proline hydroxylation. In acute myeloid leukemia, PHD3 is significantly downregulated, which limits ACC2 activity (50). Further, on acidosis, cancer cells activate both FAS and FAO, selectively inhibiting ACC2 by epigenetic suppression (histone deacetylation) of the ACC2 promoter, which results in a direct proliferative advantage for tumor cells (49). Overall, these findings indicate that ACC1 and ACC2 have diverse roles in cancer metabolism, and only ACC1 inhibition is desirable as a drug target (51). However, dual ACC1 and ACC2 inhibitors have shown promising results in nonsmall-cell lung carcinoma preclinical models (52), and they have been tested in the treatment of hepatic steatosis (53).

Here, we assessed for the first time the role of ACC1 and ACC2 in PTC of differing BRAF mutation status, and their respective responses to therapy with vemurafenib both in vitro and in vivo. We have shown that ACC2 molecular action may contribute to resistance to BRAFV600E inhibition by modulating both de novo lipid synthesis and FAO, while also modulating the rate of intracellular oxidative stress in PTC-derived cell lines. ACC2, therefore, represents a novel target in the ongoing elucidation of the mechanisms underlying drug resistance for thyroid tumor progression.

Materials and Methods

Details regarding The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) analyses, antibodies, cell cultures, vemurafenib treatment, real-time polymerase chain reaction, primers sequence, protein assays, cell proliferation, shRNAs, lipid assays, intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) assay, transmission electron microscopy, mouse model (mouse protocol was approved and performed in accordance with federal, local, and institutional guidelines at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center [BIDMC], Boston), and ultrasound can be found in Supplementary Data. The use of the following validated human PTC-derived cell lines (also defined here as PTC-derived cells) was approved by the COMS (BIDMC, Boston, MA): BCPAP is homozygous BRAFV600E (defined here as BRAFV600E/−), KTC1 is heterozygous BRAFWT/V600E, and TPC1 has BRAFWT/WT and RET/PTC1 translocation (54).

Statistical analyses

Statistical analysis was carried out by using GraphPad Prism 7 software and Microsoft Excel. Chi-square test, t-student, Fisher's exact test, Mann–Whitney U test, one-way analysis of variance for multiple comparisons tests, and Pearson correlation analysis were used. Data are reported as the averaged value, and error bars represent the standard deviation or standard error of the mean for each group. Results with p-values below 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

ACC1 and ACC2 mRNA expression levels in PTC and NT tissue samples

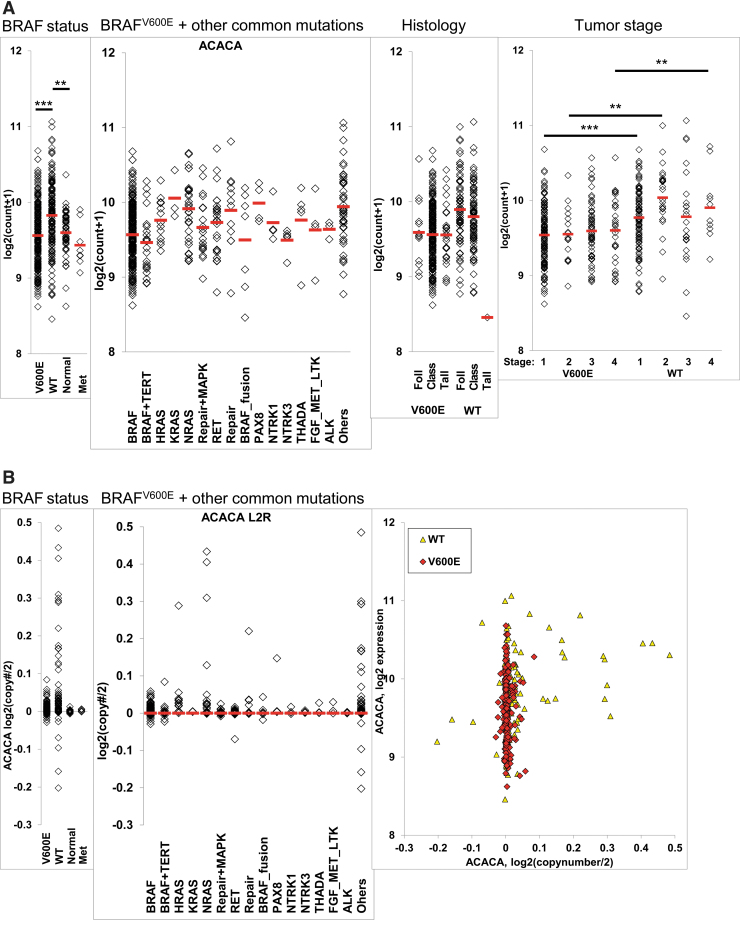

To determine ACC1 and ACC2 expression in PTC and NT clinical samples, we analyzed RNA-expression data from primary human thyroid tumors TCGA and metastasis, dividing the samples into four groups: BRAFWT/V600E-PTC, BRAFWT/WT-PTC, NT tissues, and metastasis. ACC1 mRNA levels were slightly higher on average in BRAFWT-PTC compared with the other groups, but the difference was very small and its expression levels were similar in BRAFV600E-PTC and NT (Fig. 1A). We also compared ACC1 RNA expression levels with other mutations occurring in PTC, to see whether genetic events other than the BRAFV600E mutation might have modulated its transcription levels; no significant associations were found (Fig. 1A). We then investigated whether histology type (classical, tall cell variant, or follicular variant), tumor size, sex, or age were associated with ACC1 expression levels, but we found no statistically significant differences (Fig. 1A). However, ACC1 expression levels were significantly different by BRAFWT and specific tumor stages (Fig. 1A) and also negatively correlated with the quantity (%) of enriched tumor stroma (r = −0.12123, p < 0.01). We next asked whether mRNA expression levels could be influenced by potential DNA copy number variations (CNVs) (Fig. 1B). We found a few copy number gains in BRAFWT-PTC, which positively correlated with ACC1 RNA expression levels (r = 0.2755, p < 0.001), and we observed no significant correlations in BRAFV600E-PTC and NT. We performed the same analysis for ACC2 mRNA expression levels and found that ACC2 levels were two-fold lower in BRAFV600E-PTC compared with BRAFWT-PTC, approximately four-fold compared with NT, and a two-fold difference between BRAFWT PTC and NT (Fig. 1C). Some tumor histological types appeared to be associated with the downregulation of ACC2; however, this association was highly confounded by the presence of BRAFV600E (Fig. 1C), as well as tumor stage. We estimated DNA CNVs (Fig. 1D) and as with ACC1, BRAFWT-PTC showed a few DNA copy number gains that correlated with ACC2 mRNA expression levels (r = 0.45, p < 0.001). We also checked whether age, sex, and tumor size were associated with ACC2 mRNA levels, but none of these factors showed any statistical significance. Finally, we found a negative correlation between ACC2 RNA expression levels and the quantity (%) of enriched tumors (r = −0.14807, p < 0.001) in PTC.

FIG. 1.

ACC1 (ACACA) and ACC2 (ACACB) gene expression in TCGA human PTC and NT tissue samples. (A) Differential ACACA gene expression analysis in BRAFV600E-PTC (V600E) vs. BRAFWT-PTC (WT) human samples (PTC TCGA database) or vs. NT tissue samples, adjusted to other occurring mutations, histological tumor variants, and tumor stage, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. ANOVA test was used. (B) DNA copy number gene estimate and correlation with ACACA (ACC1) expression, Pearson test was used. (C) Differential ACACB (ACC2) gene expression analysis in BRAFV600E-PTC vs. BRAFWT-PTC human samples (PTC TCGA database), or vs. NT tissue samples, adjusted to other occurring mutations, histological tumor variants, and tumor stage, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. ANOVA test was used. (D) DNA copy number gene estimate and correlation with ACACB expression, Pearson test was used. V600E = BRAFV600E-PTC; WT = BRAFWT-PTC. ACC, acetyl-CoA carboxylase; ANOVA, analysis of variance; class, classical; Foll, follicular variant; Met, metastasis; NT, normal thyroid; PTC, papillary thyroid carcinoma; tall, tall cell variant; TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas. Color images are available online.

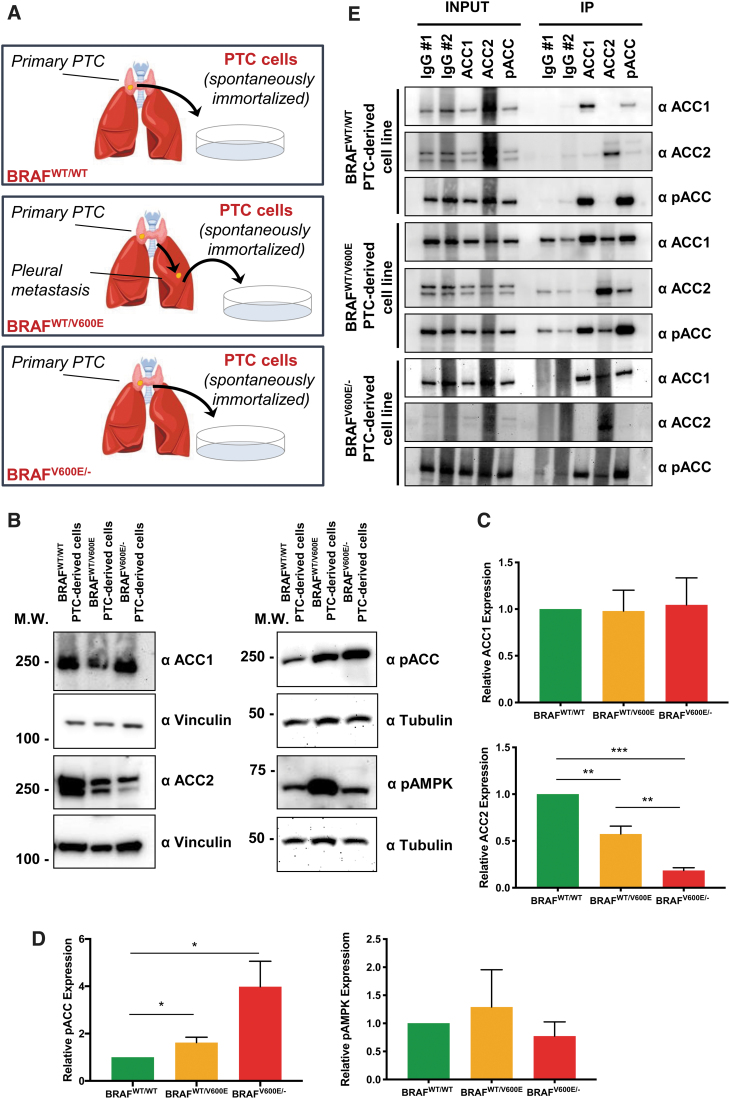

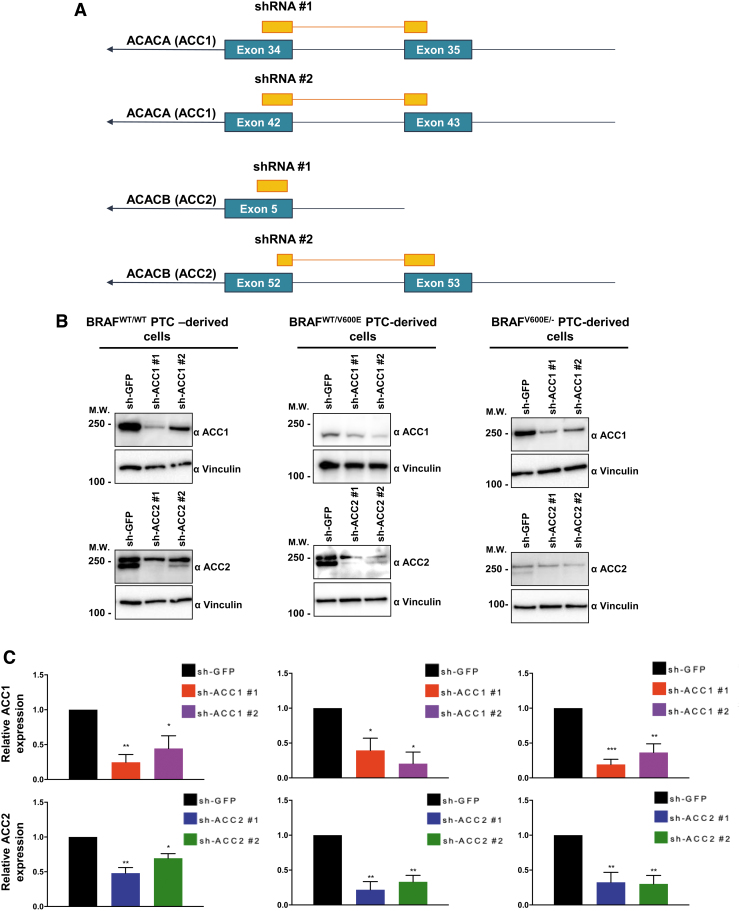

New experimental model based on ACC expression in human PTC-derived cell lines

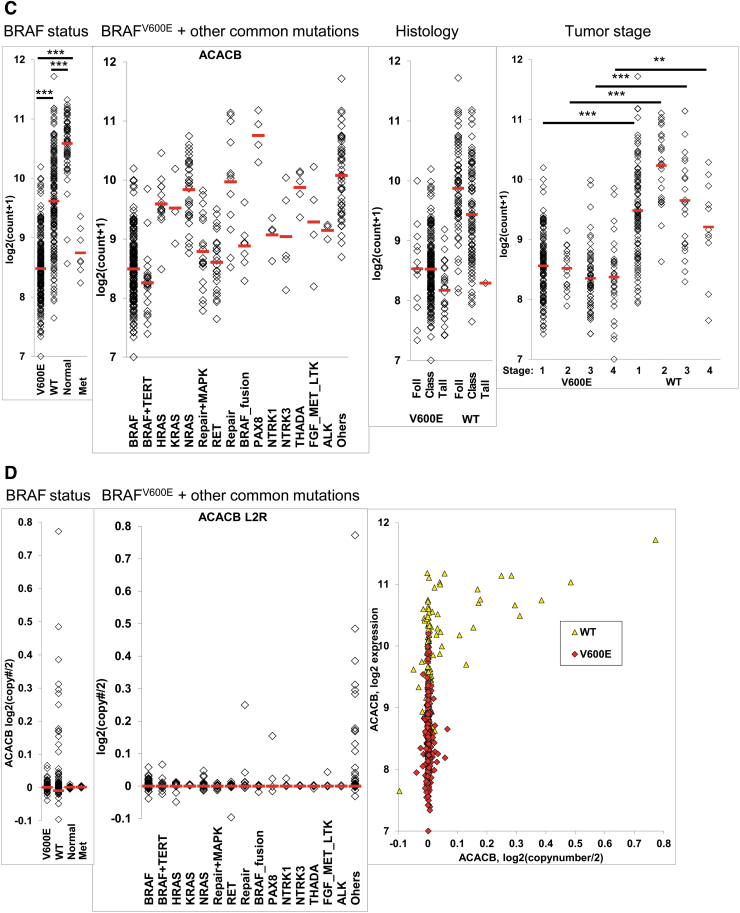

We next wanted to see whether our TCGA analysis was consistent with our in vitro models of PTC (Fig. 2A). We first analyzed ACC1 and ACC2 protein expression at baseline, and we saw that both BRAFV600E PTC-derived cell lines had lower levels of ACC2 compared with BRAFWT/WT; more importantly, these ACC2 decreases looked to be dependent on gene dosage of BRAFV600E (Fig. 2B). Indeed, the BRAFV600/− PTC-derived cell line consistently had less ACC2 protein expression than BRAFWT/V600E. We further analyzed the phosphorylation status of ACC1, ACC2, and AMPK, since post-translational modification is linked to inactivation of these two enzymes, and AMPK is the best-characterized kinase targeting ACC. We found that both heterozygous and homozygous BRAFV600E PTC-derived cell lines have significantly higher ACC phosphorylation levels (1.6- and 4-fold changes, respectively) than the BRAFWT/WT PTC-derived cell line (Fig. 2B–D). In addition, AMPK phosphorylation levels rose 1.3-fold in the heterozygous BRAFV600E PTC-derived cell line only. Due to indistinguishable epitope recognition by pACC antibody on ACC1 versus ACC2 proteins, we were not able to precisely determine which isoform is predominantly phosphorylated in thyroid cancer cells. Thus, we performed selective immunoprecipitation (IP) for ACC1, ACC2, and pACC (Fig. 2E) to first assess each protein phosphorylation level at baseline, and second, since ACC2 produced two close bands in the Western blots (Fig. 2B) [the only known splicing variant is described in adipose tissue (55)], to assess the specificity of the two bands. ACC1 was consistently phosphorylated in all three PTC-derived cell lines (Fig. 2E), while ACC2 was phosphorylated only in the BRAFV600E PTC-derived cell lines, but at a substantially lower rate than ACC1 (Fig. 2E), suggesting that BRAFV600E-positive thyroid tumor cells post-translationally deregulate ACC1 and ACC2 and render them inactive. ACC2 protein expression showed different intensity in the two bands in the IP versus the specific input, which may have been caused by co-migration after the IP process. Further studies will be needed to interpret the biological meaning of the two bands; for all subsequent analyses we have quantified the intensity of both bands, since both were modulated.

FIG. 2.

Characterization of ACC1 and ACC2 expression in PTC-derived cell lines with BRAFWT/WT, heterozygous BRAFWT/V600E, or homozygous BRAFV600E/−. (A) In vitro model of PTC using three spontaneously immortalized PTC-derived cell lines with differing BRAF status (BRAFWT/WT, BRAFWT/V600E, and BRAFV600E/−). (B) Representative WB analysis of three PTC-derived cell lines shows ACC1, ACC2, pACC and pAMPK protein expression levels at baseline. (C, D) Densitometry quantification. (E) IP of ACC1, ACC2, and pACC in PTC cell lysates, analyzed by WB. Five percent input is protein lysate after preclearing and before IP. IgG#1 and IgG#2 are normal rabbit IgG and rabbit mAb IgG, used respectively as negative controls. WB results were validated by at least three independent replicate measurements. These data represent the average ± standard deviation (error bars) of three independent experiments (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001). IP, immunoprecipitation; WB, Western blot. Color images are available online.

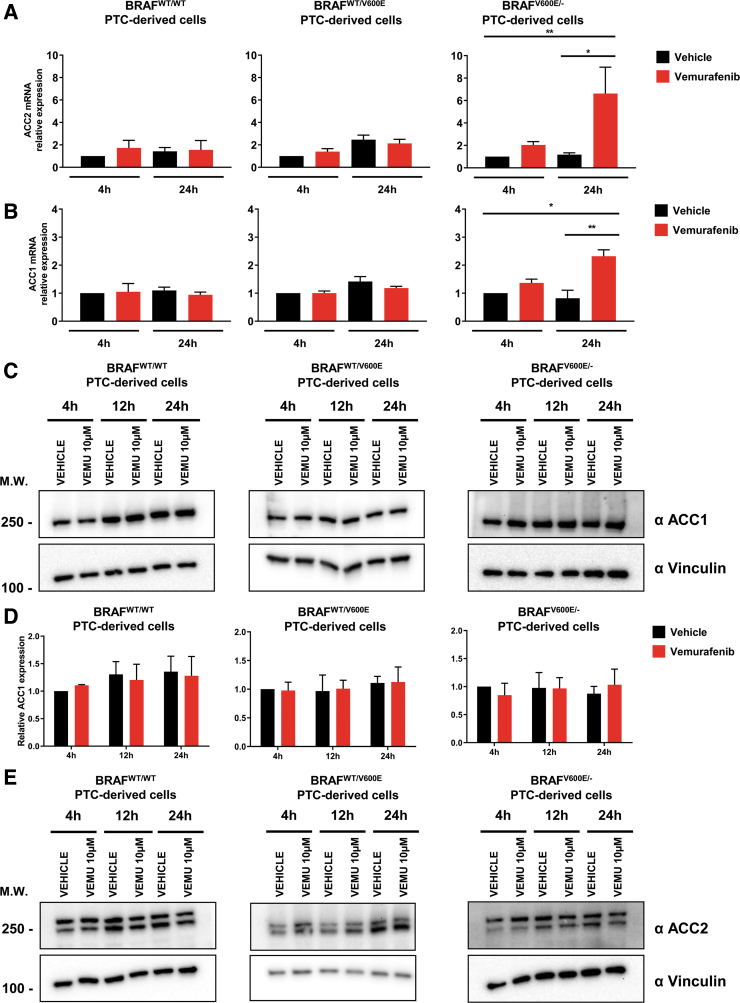

Targeting BRAFV600E with vemurafenib rescues ACC transcriptional levels in a BRAFV600E allelic dose-dependent manner

All clinical samples of PTC are heterozygous for BRAFV600E mutation (3). We next asked whether selectively targeting BRAFV600E with vemurafenib might modify ACC1 and ACC2 mRNA expression levels observed at baseline in our PTC-derived cell lines. We first measured mRNA expression levels at two time points after treatment with vemurafenib, 4 and 24 hours. Our previous studies showed robust effects on pERK1/2 levels by using 10 μM of vemurafenib compared with lower doses (18). Our metabolic assays here in the current study were performed within 12 hours of vemurafenib treatment to avoid the expected elicitation of resistance, as after this time point we have found in KTC1 heterozygous BRAFWT/V600E PTC-derived cell line a substantial rebound of pERK1/2 levels at 24 hours in the surviving tumor cells, and a further rise at 48 hours (18). Also, we analyzed in this current study pERK1/2 levels in the BCPAP homozygous BRAFV600E/− PTC-derived cell line at 4, 12, and 24 hours (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Here, we found that both ACC2 (five-fold) and ACC1 (two-fold) mRNAs were significantly upregulated by vemurafenib in the homozygous BRAFV600E/− PTC-derived cell line at 24 hours (Fig. 3A, B), but not in heterozygous BRAFWT/V600E and BRAFWT/WT. The increases in ACC2 mRNA levels were higher than ACC1 mRNA levels at 4 hours (1.39-fold in heterozygous or 1.22-fold in homozygous) and 24 hours (1.8-fold in heterozygous or 2.48-fold in homozygous) in BRAFV600E PTC-derived cell lines (Fig. 3A, B). In addition, we analyzed ACC protein levels on treatment with vemurafenib at an intermediate time point (12 hours) to better characterize ACC modulation (Fig. 3C–F). ACC1 protein levels showed no change after vemurafenib treatment (Fig. 3C, D), suggesting that potential post-transcriptional and/or post-translational mechanisms may be involved in the impairment of protein stability. In contrast, ACC2 protein levels were upregulated in both heterozygous and homozygous BRAFV600E PTC-derived cell lines over time (at 24 and 12 hours), with no significant difference observed between vemurafenib and vehicle, perhaps due to the low concentration of serum in the culture media during treatment (Fig. 3E, F). Moreover, we found that at 12 hours, ACC2 protein expression showed a rising trend of increased levels after treatment with vemurafenib compared with vehicle in the heterozygous BRAFV600E PTC-derived cell line (Fig. 3E), although this was not statistically significant across different independent experimental replicates (Fig. 3F); these findings suggest that the genetic heterogeneity of these tumor cells may impact the rescue of ACC2 levels during the therapeutic targeting of BRAFV600E.

FIG. 3.

Effects of vemurafenib treatment on ACC1 and ACC2 expression in PTC-derived cell lines. (A, B) ACACB (ACC2) and ACACA (ACC1) gene expression analysis by real-time polymerase chain reaction on PTC-derived cell lines treated with 10 μM vemurafenib (vemu) or vehicle at the indicated time points. (C–H) Representative WB analysis and densitometry quantification of PTC-derived cell lines treated with 10 μM vemurafenib or vehicle at the indicated time points for relative expression of ACC1, ACC2, pACC, and pAMPK. Values represent the average of at least three independent experiments ± standard deviation (error bars) (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001). Relative expression was calculated as ratio between values in each condition divided by the value of vehicle at four hours. Color images are available online.

To better understand the dynamics of post-translational regulation of both ACC1 and ACC2, we analyzed the expression of pACC and pAMPK (a kinase known to be responsible for ACC phosphorylation and inactivation) and found significantly upregulated phosphorylation of both ACC and AMPK in BRAFV600E PTC-derived cell lines at different time points after vemurafenib treatment (Fig. 3G–H). Overall, these results suggest that ACC2 expression is transcriptionally modulated by vemurafenib in a BRAFV600E allelic-dependent manner, and in addition may be regulated by post-transcriptional and/or post-translational mechanisms.

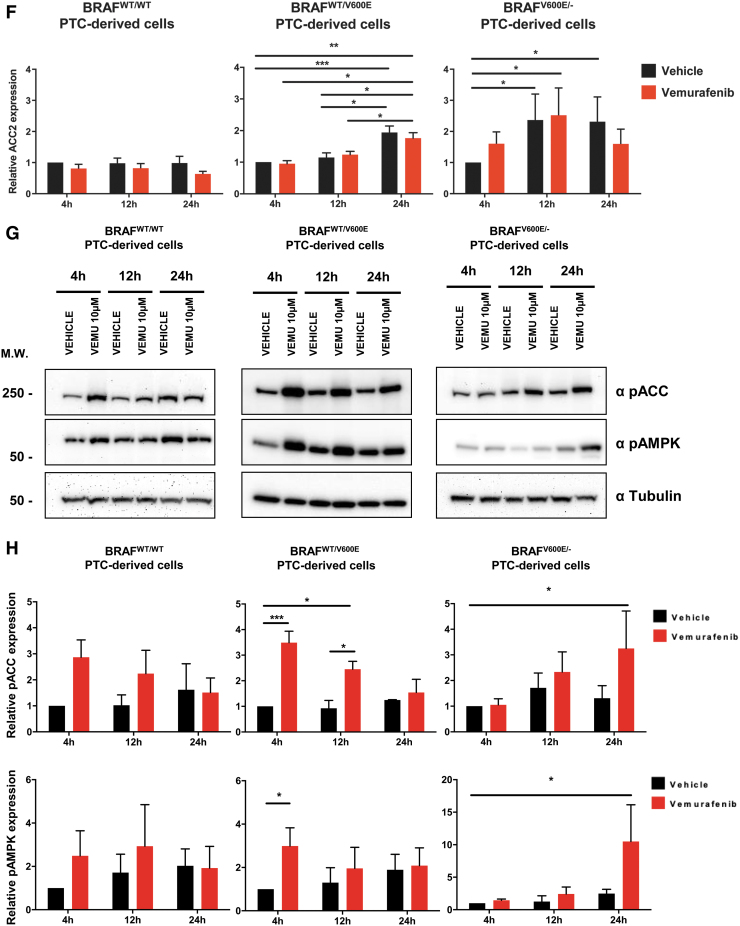

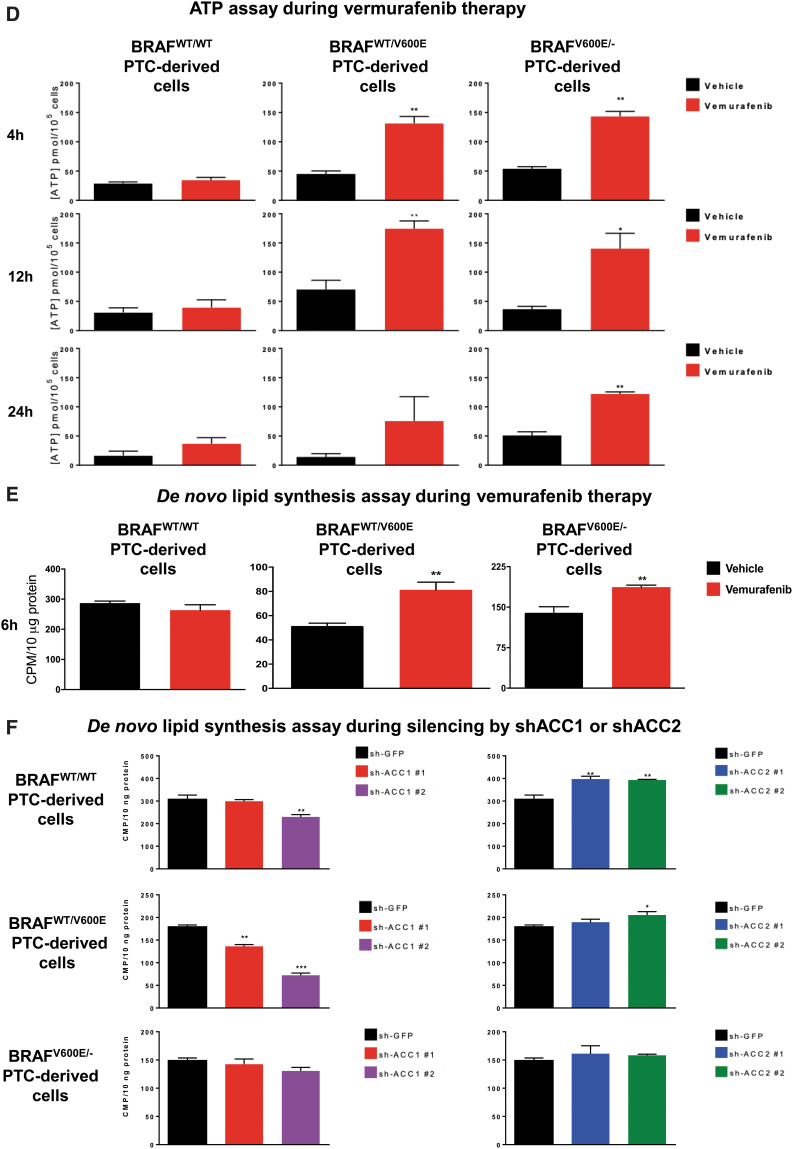

Targeting BRAFV600E with vemurafenib or ACC gene silencing modulates intracellular ATP and NADPH concentrations, de novo lipid synthesis, FAO, and ROS levels

Since ACC2 transcript levels (and to a lesser extent ACC1) are significantly regulated by BRAFV600E activity in PTC clinical samples, we investigated potential biological phenotypes after treatment with a selective BRAFV600E inhibitor (vemurafenib) or using shRNAs (sh) that efficiently target ACC1 or ACC2 (Fig. 4A–C). First we analyzed ATP intracellular concentration at all time points previously selected (Fig. 4D), since ATP is the molecular unit of currency of intracellular energy transfer and one of the fundamental compounds involved in many metabolic processes, including lipid (fatty acid) synthesis and oxidation. We found that vemurafenib-treated BRAFV600E PTC cells significantly increased ATP concentration at different levels at specific time points (Fig. 4D). This phenotype may be explained by the inhibitory effects of vemurafenib on BRAFV600E, which uses ATP as a donor of phosphate groups to downstream MEK1/2-ERK1/2. Knockdown of either ACC1 or ACC2 did not change ATP levels. Intriguingly, when we measured ACC enzymatic activity, we found that de novo lipid synthesis significantly increased (1.58- and 1.34-fold change in heterozygous and homozygous BRAFV600E-derived cell lines, respectively) within six hours in vemurafenib-treated BRAFV600E PTC-derived cells compared with vehicle (Fig. 4E). The de novo lipid synthesis assay was of short duration (six hours) to avoid major morphological changes in the cell structure by vemurafenib treatment.

FIG. 4.

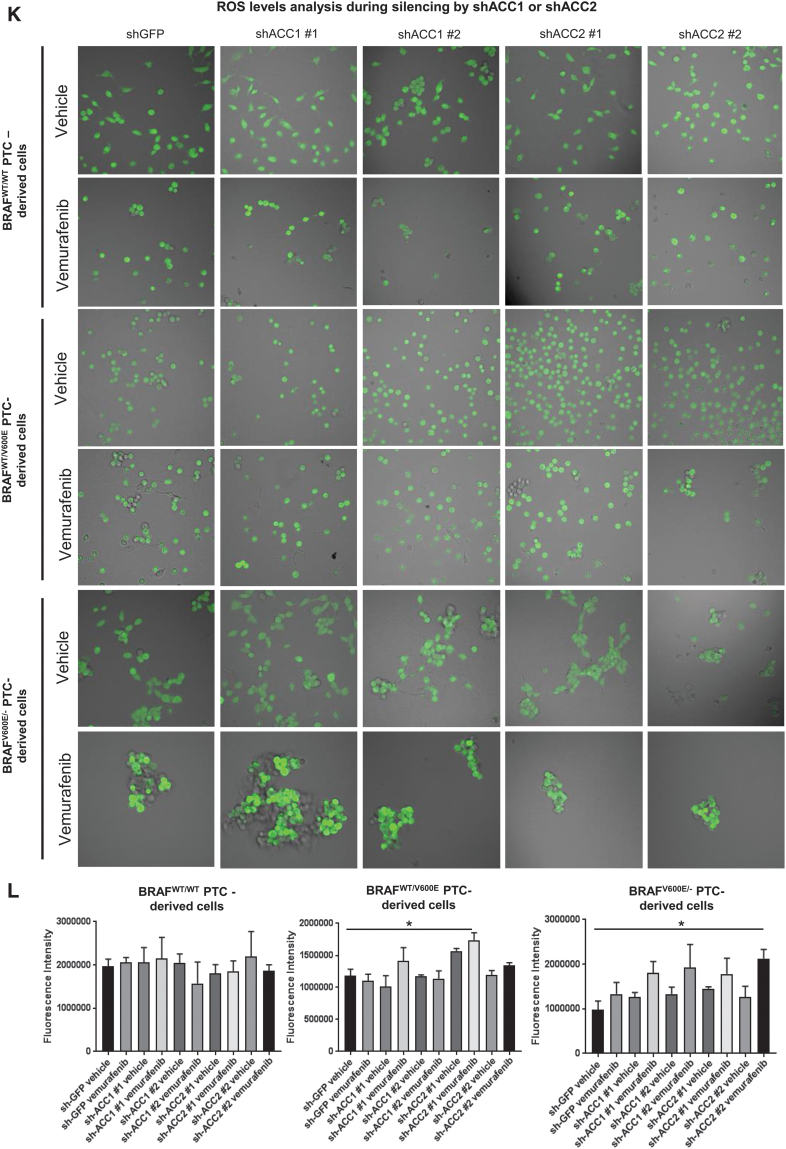

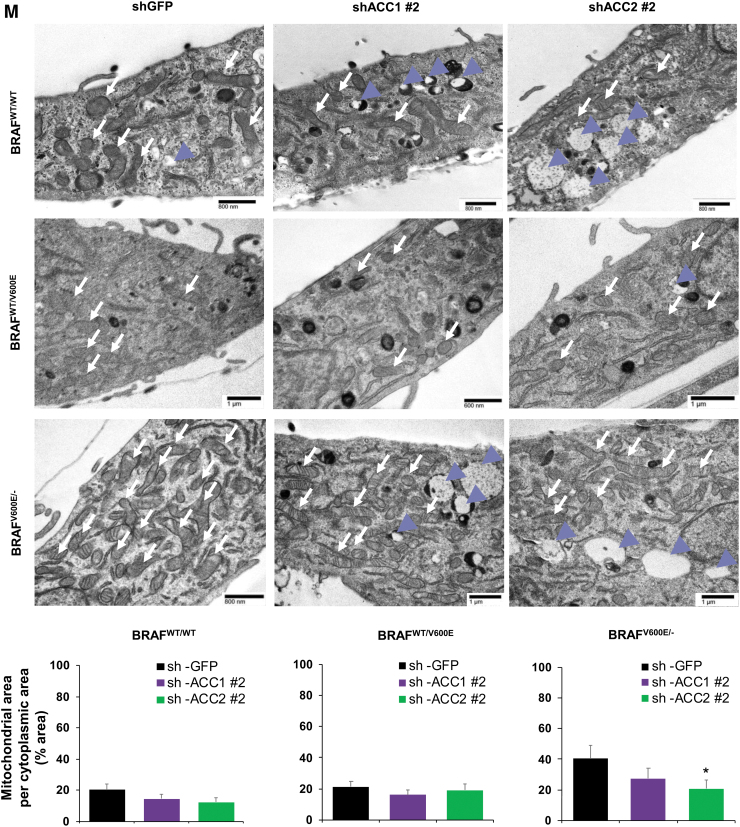

Effects of both vemurafenib treatment and knockdown of ACC1 or ACC2 on ATP levels, de novo lipid synthesis, β-oxidation, and intracellular ROS production in PTC-derived cell lines. (A) Schematic representation of shRNA alignment on ACC genes used for knockdown. (B) Representative WB analysis of knockdown efficiency by using selective shRNA (sh) shACC1 or shACC2 vs. shGFP control in BRAFWT/WT, BRAFWT/V600E, and BRAFV600E/− PTC-derived cell lines. (C) Densitometric quantification of the WB analysis. (D) Luminescence-based ATP detection in PTC cells treated with 10 μM vemurafenib or vehicle at indicated time points. (E) 14C-Acetate de novo lipid synthesis detection in PTC-derived cell lines treated with 10 μM vemurafenib or vehicle at six hours. (F) 14C-Acetate de novo lipid synthesis detection in PTC-derived cell lines with knockdown (shACC1, shACC2, or shGFP [control]) at six hours of incubation. (G) β-oxidation (FAO assay) in PTC-derived cell lines treated with 10 μM vemurafenib or vehicle at 12 hours with or without addition of exogenous palmitate to the assay medium (Palm:BSA vs. BSA). (H) β-oxidation (FAO assay) in PTC-derived cell lines with knockdown of shACC1, shACC2, or shGFP control after 16 hours of postcell seeding, with or without addition of exogenous palmitate to the assay medium (Palm:BSA vs. BSA). (I) The Seahorse XFe96 Analyzer that we have utilized can simultaneously measure the two major energy-producing pathways in live cells: mitochondrial respiration and glycolysis. This Seahorse technology measures mitochondrial respiration and glycolysis under baseline and stress conditions to assess important parameters of cell energy metabolism, including baseline and stressed energy phenotypes. It classifies four relative cell bioenergetic phenotypes: (i) quiescent (cells are not very energetic via either metabolic pathway), (ii) energetic (cells utilize both metabolic pathways), (iii) aerobic (cells utilize mainly mitochondrial respiration), and (iv) glycolytic (cells utilize predominantly glycolysis). Cell energy phenotype maps show: baseline and stressed phenotype for PTC-derived cell lines treated with 10 μM vemurafenib or vehicle at 12 hours. OCR: The rate of decrease of oxygen concentration in the assay medium. OCR is a measure of the rate of mitochondrial respiration. ECAR: The rate of increase in proton concentration in the assay medium. ECAR is a measure of the rate of glycolysis of the cells. Baseline phenotype: OCR and ECAR of cells at starting assay conditions, that is, in the presence of nonlimiting quantity of substrates. Stressed phenotype: OCR and ECAR under induced energy demand, that is, in the presence of stressors. Metabolic potential: increase of stressed OCR over baseline OCR, and stressed ECAR over baseline ECAR. Metabolic potential measures a cell's ability to meet energy demands. Histograms: basal and maximal glycolysis levels assessed by ECAR rates in PTC-derived cell lines treated with 10 μM vemurafenib or vehicle at 12 hours. (J) Basal and maximal glycolysis levels assessed by ECAR rates in PTC-derived cell lines with knockdown of shACC1, shACC2, or shGFP control after 16 hours postcell seeding, with or without addition of exogenous palmitate to the assay medium (Palm:BSA vs. BSA). (K) Intracellular ROS detection with CM-H2DCFDA live staining in shGFP, shACC1, or shACC2 PTC-derived cell lines treated with 10 μM vemurafenib or vehicle at 12 hours. (L) Bar graph values represent the average of mean fluorescence for ROS (images in L) of each cell in the captured images. All values in these image panels of the figure represent either the average ± standard deviation or standard error of the mean (error bars) of at least three independent experiments (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001). (M) Morphometric analysis of the mitochondrial area normalized to cytoplasmic area (% of mitochondria area) in shGFP (control), shACC1 or shACC2 BRAFWT/WT, BRAFWT/V600E, and BRAFV600E/− PTC-derived cell lines through transmission electron microscopy. Data represent mean ± standard error of mean, *p < 0.05. Arrows = mitochondria; arrowheads = lysosome. BSA, bovine serum albumin; ECAR, extracellular acidification rate; FAO, fatty acid oxidation; OCR, oxygen consumption rate; Palm, palmitate; ROS, reactive oxygen species. Color images are available online.

Our shRNA experiments confirmed the specificity of de novo lipid synthesis or FAO (oxygen consumption rate [OCR] and extracellular acidification rate [ECAR]) regulation by ACC1 or ACC2 (Fig. 4F, H, L). As a result of ACC1 or ACC2 molecular action, knockdown (sh) of ACC1 showed significant reductions in de novo lipid synthesis rates mostly in BRAFWT/WT (0.75-fold change, 25% decrease) and heterozygous BRAFWT/V600E (0.76- or 0.4-fold change, 24% and 60%, respectively) cells, which is consistent with the major role played by ACC1 in FAS. Knockdown (sh) of ACC2 instead showed an opposite trend, with significantly increased de novo lipid synthesis rates (1.29-fold change [29%] in BRAFWT/WT and 1.15-fold change [15%] in heterozygous BRAFWT/V600E PTC-derived cells) (Fig. 4F). In contrast, shACC1 or shACC2 did not exhibit any modulation in homozygous BRAFV600E/− PTC-derived cells (Fig. 4F), likely because these cells showed more robust downregulation of basal ACC2 levels (Figs. 2B and 4B) compared with the BRAFWT/WT PTC-derived cell line, and, to a lesser extent, to heterozygous BRAFWT/V600E PTC-derived cells. Results for ACC1 were similar, even if its levels were higher than ACC2 in these cells. In sum, ACC1 or ACC2 knockdown by shRNA had differing impacts in the PTC-derived cell lines; this may be due to additional metabolic genes modulating their regulation of de novo lipid synthesis or β-oxidation. FAO (β-oxidation) was characterized by OCR, and after adding palmitate (PALM):bovine serum albumin (BSA) versus BSA to the assay medium, the BRAFWT/WT PTC-derived cell line showed a preference for oxidative phosphorylation (96% of basal respiration and 93% of maximal respiration) compared with heterozygous BRAFV600E PTC-derived cells. In contrast, 38% of basal and maximum respiration OCR was due to FAO in heterozygous BRAFWT/V600E PTC-derived cells (Fig. 4G). The OCR due to FAO was strongly inhibited in homozygous BRAFV600E/− PTC-derived cells at both basal and maximal respiration (Fig. 4G) compared with heterozygous BRAFWT/V600E PTC-derived cells or BRAFWT/WT PTC-derived cells. Vemurafenib treatment significantly rescued ACC2 mRNA levels compared with vehicle (Fig. 3B) in homozygous BRAFV600E/− PTC-derived cells, although those levels of re-expression were not statistically significant in OCR levels versus vehicle-treated cells (Fig. 4G). Pathways essential for mitochondria respiration may be deregulated in homozygous BRAFV600E/− PTC-derived cells, contributing to the reduction of OCR levels. As a result of this deregulation, these cells may shift to glycolysis. Although OCR due to FAO was higher in the heterozygous BRAFWT/V600E PTC-derived cell line compared with the BRAFWT/WT PTC-derived cell line, critically, their basal respiration OCR due to FAO significantly decreased from 7.95 ± 2.57 pmol/min in the vehicle-treated heterozygous BRAFWT/V600E PTC-derived cells to no utilization of FAO (−0.17 ± 1.26 pmol/min) in vemurafenib-treated heterozygous BRAFWT/V600E PTC-derived cells (p = 0.0154) (Fig. 4G), which also showed a rising trend in ACC2 protein expression levels at 12 hours (Fig. 3E). Similarly, maximal respiration due to exogenous palmitate addition fell significantly, from 7.69 ± 1.92 pmol/min in the vehicle group to 2.64 ± 1.04 in the vemurafenib-treated group (66% decrease, p = 0.0296) (Fig. 4G).

In addition, we found that with silencing (sh) of ACC2 levels both basal and maximum respiration OCR due to FAO were significantly increased (51%, p = 0.0306; 70% p = 0.0341, respectively) in the heterozygous BRAFWT/V600E PTC-derived cell line, while we observed a positive trend in the homozygous BRAFV600E/− PTC-derived cell line (Fig. 4H).

Importantly, mitochondria are both a source and target for oxidative stress. Mitochondrial cellular function can be defined by using a stress test in which the addition of stressors (e.g., vemurafenib, or gene silencing by shRNA, e.g., shACC) can cause alterations in a cell's OCR and bioenergetic profile. With Seahorse technology, we have assessed the levels of FAO through OCR rates (Fig. 4G, H), and glycolysis levels through ECAR rates, as indicators of oxidative stress (measurements of stressed OCR over baseline OCR, and stressed ECAR over baseline ECAR) (Fig. 4I–L). These measurements were performed in vemurafenib-treated PTC-derived cell lines versus vehicle-treated cell lines, or shACC1- or shACC2-transduced PTC-derived cell lines versus shGFP control cell lines with or without addition of exogenous palmitate to the assay medium (Palm:BSA vs. BSA, Fig. 4G–L). In addition to OCR as a metric of energy metabolism, we have also analyzed ECAR (indicator of glycolysis levels after addition of palmitate) rates in three cell lines with different BRAF genetic status. Baseline glycolysis was significantly higher (p < 0.001) in homozygous BRAFV600E/− PTC-derived cells (44.82 ± 3.25 mpH/min) compared with either heterozygous BRAFWT/V600E PTC-derived (14.12 ± 1.40 mpH/min) or BRAFWT/WT PTC-derived cell line (24.87 ± 3.41 mpH/min) (Fig. 4I). Similar results were found in stressed glycolysis (ECAR levels before addition of palmitate), indicating that homozygous BRAFV600E/− PTC-derived cells rely on glycolysis for energy demand. Vemurafenib-treated homozygous BRAFV600E/− PTC-derived cells showed a declining trend in glycolysis (ECAR level), although not at a statistically significant level (Fig. 4I). After utilization of exogenous palmitate, heterozygous BRAFWT/V600E PTC-derived cells showed no significant change in baseline glycolysis (ECAR levels = 14.12 ± 1.40 mpH/min, vehicle Palmitate:BSA) as compared with vehicle BSA (ECAR = 14.58 ± 2.29 mpH/min); while vemurafenib-treated cells showed a significant decrease in glycolysis (ECAR level = −6.27 ± 1.07 mpH/min, p = 0.0085) (Fig. 4I). Similarly, maximal glycolysis due to exogenous palmitate addition was significantly (p = 0.0002) decreased in the vemurafenib-treated heterozygous BRAFWT/V600E PTC-derived cell line (−2.39 ± 0.46 mpH/min) compared with vehicle-treated cells (3.00 ± 0.87 mpH/min), indicating that vemurafenib therapy inhibits glycolysis (Fig. 4I). No changes in ECAR rates were observed in the BRAFWT/WT PTC-derived cell line with vemurafenib treatment (Fig. 4I). In addition, in the heterozygous BRAFWT/V600E PTC-derived cell line with silencing (sh) of ACC2, we observed that after addition of exogenous palmitate, ECAR significantly decreased in both basal (98%, p = 0.031) and maximal glycolysis (71%, p = 0.0177) as compared with shGFP control cells (Fig. 4J), suggesting that ACC2 plays an important role in these metabolic processes.

Collectively, our metabolic data indicate that the heterozygous BRAFWT/V600E PTC-derived cell line uses palmitate for FAO to provide energy (at rates at least two-fold higher than BRAFWT/WT PTC-derived cell line), whereas the homozygous BRAFV600E/− PTC-derived cell line lacks this ability. The homozygous BRAFV600E/− PTC-derived cell line and heterozygous BRAFWT/V600E PTC-derived cell line exhibited lower glucose oxidative phosphorylation levels compared with the BRAFWT/WT PTC-derived cell line. The homozygous BRAFV600E/− PTC-derived cell line showed higher levels of glycolysis compared with both the heterozygous BRAFWT/V600E PTC-derived cell line and the BRAFWT/WT PTC-derived cell line.

Further, deregulations in mitochondrial respiration machinery are known to influence the intracellular rate of ROS in a membrane potential-independent mode. Therefore, we subsequently investigated a possible redox imbalance in the cells, given the role of ACC1 and ACC2 in consuming and reducing co-factors, which play a fundamental role in maintaining ROS in the cytosol. We further investigated a possible redox imbalance in the PTC-derived cell lines, given the importance of ACC1 and ACC2 in the consumption of NADPH (25). Vemurafenib treatment had no effect on NADP/NADPH ratios in the PTC-derived cells (Supplememtary Fig. S2A), while shACC1 or shACC2 significantly increased NADPH concentrations and decreased NADP/NADPH ratios in the heterozygous BRAFWT/V600E PTC-derived cell line (Supplementary Fig. S2B). To determine whether the fine-tuning of lipid metabolism via ACC enzymes and BRAFV600E affects the oxidative stress of PTC cell lines, we assessed intracellular ROS levels in these cells by using live cell staining assays (Fig. 4K, L). We found that ROS fluorescence intensity was significantly higher (1.48- and 2.15-fold change in heterozygous and homozygous BRAFV600E PTC-derived cell lines, respectively) in vemurafenib-treated BRAFV600E PTC cell lines engineered to express shACC2 versus vehicle-treated shGFP cells (control), suggesting that knockdown of ACC2 may accelerate oxidative stress in BRAFV600E-PTC cells (Fig. 4K, L). Compared with the BRAFWT/WT PTC-derived cell line, BRAFV600E PTC-derived cell lines showed a significant increase in the mitochondrial area in a BRAFV600E allelic-dose dependent manner (i.e., homozygous BRAFV600E/− tumor cells, Fig. 4M), and the knockdown of ACC2 significantly deregulated the ratio between the mitochondrial and cytoplasmic area, and also led to substantial increase in lysosomes (Fig. 4M). There is evidence in the literature that mitochondria and lysosomes can elicit functional cross-talk and converge on mitophagy. How ACC2 impacts this regulation is unknown and will be further investigated in future studies.

ACC2 knockdown contributes to resistance to vemurafenib therapy in a xenograft mouse model derived from a heterozygous BRAFWT/V600E PTC cell line, leading to increased tumor cell growth

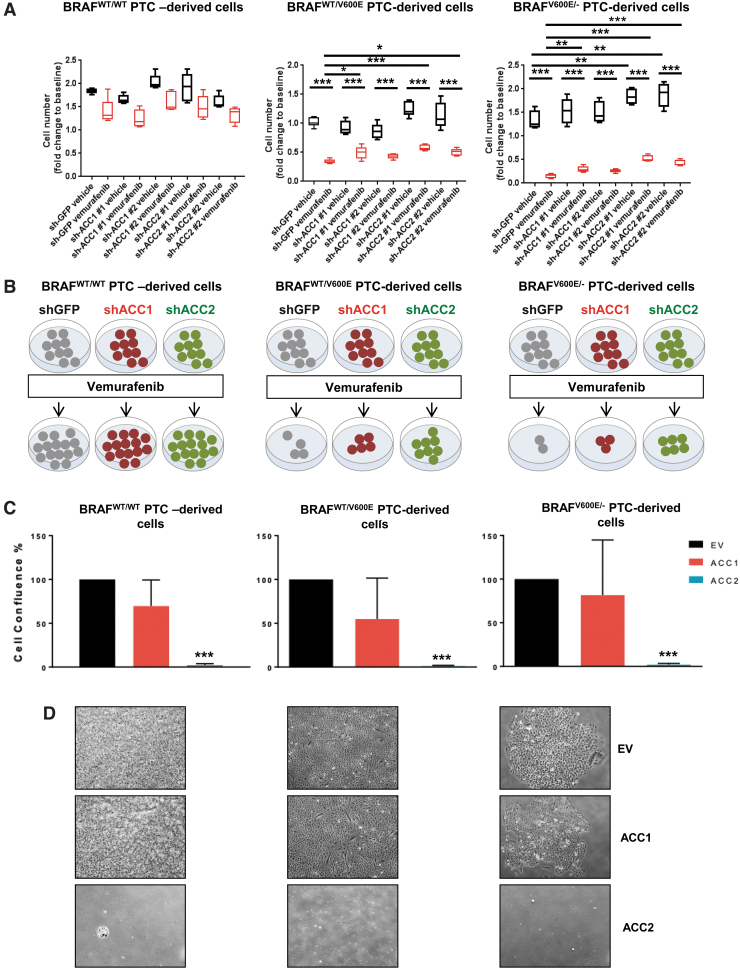

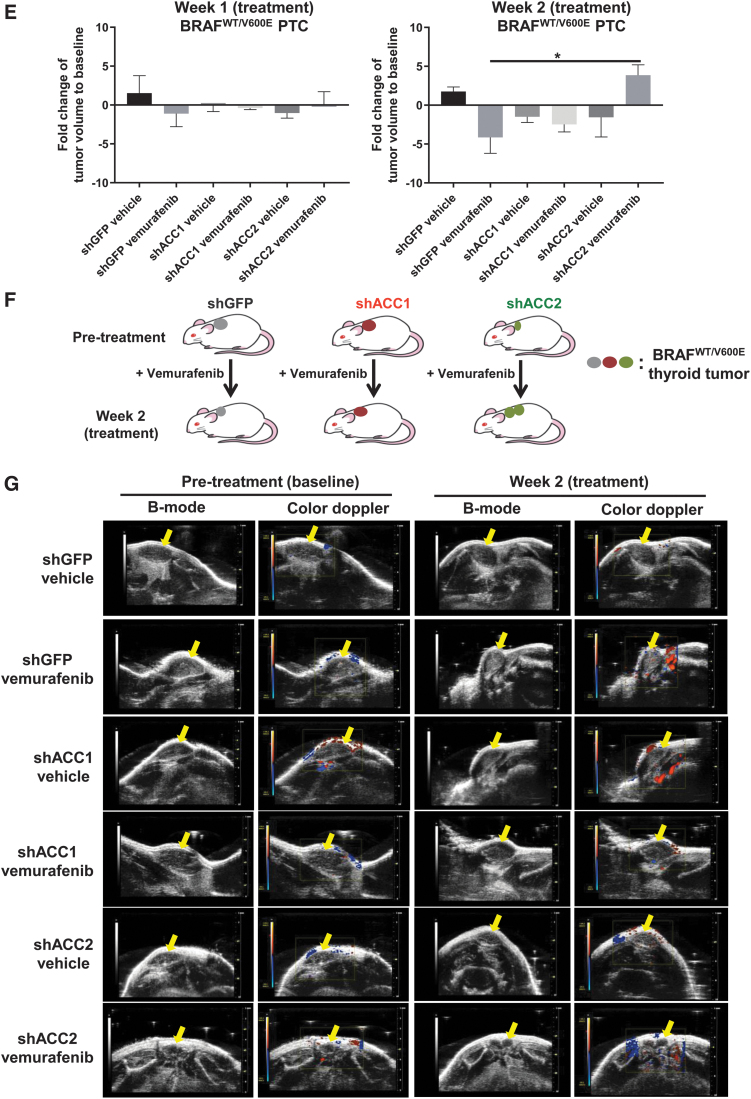

Since deregulation of oxidative stress thresholds could contribute to abnormal tumor growth (56), we performed selective knockdowns of ACC1 or ACC2 (Fig. 4A–C) and assessed cell proliferation (Fig. 5A, B). Cell proliferation significantly increased in shACC2 BRAFV600E PTC-derived cell lines treated with vemurafenib (i.e., 1.75 [shACC2 #1] and 1.45 [shACC2 #2] fold changes in the heterozygous BRAFWT/V600E cells, and 3.46 [shACC2 #1] and 2.8 [shACC2 #2] fold changes in the homozygous BRAFV600E/− cells) compared with shGFP vemurafenib-treated cells, with no significant change in BRAFWT/WT PTC cells (Fig. 5A, B). Results from ACC1 knockdown were not as robust across all cell lines (Fig. 5A, B). These results suggest that reduction of ACC2 levels through the BRAFV600E pathway may reduce the inhibitory effect of vemurafenib against thyroid tumor cell viability, and may lead to drug resistance. Further, we selectively overexpressed either ACC1 or ACC2 and found that exogenous expression of ACC2 potently impairs PTC-derived cell lines proliferation, leading to cell growth arrest at a rate of nearly 100% (Fig. 5C, D) whereas the same cell lines engineered with ACC1 overexpression showed a similar proliferation rate to empty vector (control cells).

FIG. 5.

Effects of knockdown or overexpression of ACC1 or ACC2 on tumor cell proliferation in PTC-derived cell lines. (A) Cell proliferation assay with final measurements at day 5 in PTC-derived cell lines treated for 16 hours with 10 μM vemurafenib or vehicle. Box plots show the average cell number and the range minimum to maximum with whisker plotting the standard error, one-way ANOVA test (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001). (B) Representation of cell growth of shGFP, shACC1, and shACC2 thyroid tumor cells treated with vemurafenib compared with baseline (pretreatment). (C, D) PTC-derived cell lines transduced with EV (empty vector, control), ACC1, or ACC2 for overexpression for 20 days. Data are plotted as cell confluence percentage quantified by bright-field light microscopy at magnification 4 × . Values represent the average ± standard deviation (error bars) of three independent experiments (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001). (E) Tumor volume was measured by using ultrasonography, averaged ± standard error of mean in each group during the two weeks of treatment and plotted through histograms as fold changes, that is, their final size values divided by baseline tumor size values. All six groups (shGFP, shACC1, shACC2, treated with vemurafenib, or vehicle) were compared. Fold changes of tumor size (tumor size at week 2/tumor size at pretreatment) were calculated for all groups (one-way ANOVA test, *p < 0.05). (F) Representation of tumor growth of shGFP, shACC1, and shACC2 thyroid tumors treated with vemurafenib at week 2 and compared with pretreatment (baseline). (G) Representative images of B-mode and color Doppler to analyze tumor size and tumor vascularity. Yellow arrows highlight hypoechoic tumor region in the subcutaneous area. EV, empty vector. Color images are available online.

To assess the impact of ACC1 and ACC2 on tumor growth, and their effects on vemurafenib therapy, we have established the first xenograft mouse model by using the heterozygous BRAFWT/V600E human PTC-derived cell line (i.e., KTC1) engineered with knockdown of either ACC1 or ACC2 (Fig. 5E–G). After two weeks of vemurafenib treatment (Fig. 5E–G), we found no statistical differences in tumor size between the groups of mice implanted with shGFP, shACC1, or shACC2 BRAFWT/V600E human KTC1 cells. Intriguingly, only shACC2 BRAFWT/V600E KTC1 tumors treated with vemurafenib showed increased growth and higher volume (1.44-fold change, p < 0.05) compared with pretreatment baseline, in contrast to the trend observed in vemurafenib-treated shGFP tumors (Fig. 5E–G). shGFP (0.64-fold change) or shACC1 (0.83-fold change) BRAFWT/V600E KTC1 tumors treated with vemurafenib showed decreased tumor volume compared with their baseline. All vemurafenib-treated tumors showed solid nodular components independent of their ACC1 or ACC2 knockdown. Color Doppler sonography displayed blood flows in the peritumoral area within two weeks of treatment in shGFP, shACC1, and shACC2 tumors (Fig. 5G) and showed no statistically significant differences between these groups.

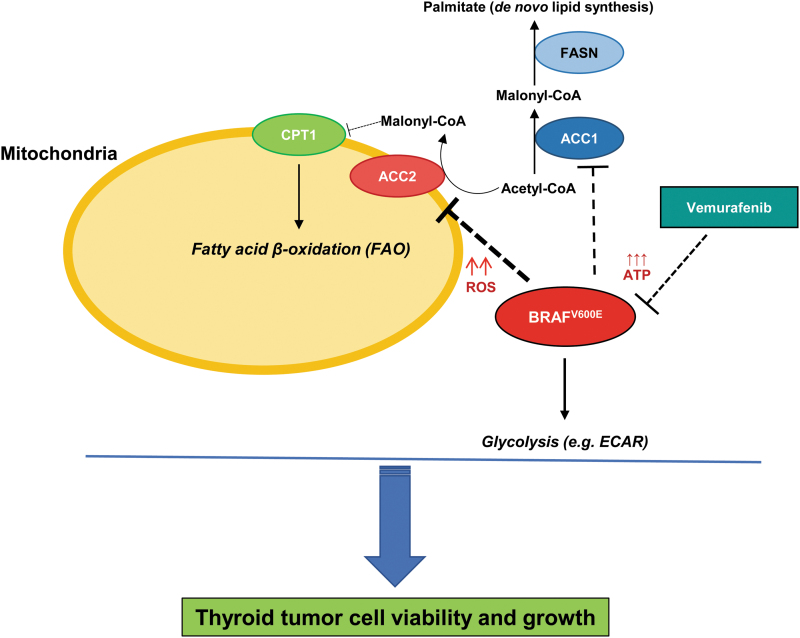

Overall, our findings suggest that downregulation of ACC2, through BRAFV600E, sustains thyroid tumor cell growth (Fig. 6).

FIG. 6.

Experimental metabolic model of ACC genes' functions for thyroid carcinoma cell growth. Schematic representation of molecular model of functions between BRAFV600E, ACC1, and ACC2 in human thyroid tumor cell metabolism. Arrows represent modulation, dashed lines represent inhibition, and upward arrows represent increased levels (i.e., ROS and ATP). CPT1, carnitine palmitoyltransferase I; FASN, fatty acid synthase. Color images are available online.

Discussion

Since the initial observations of Otto Warburg (57) describing the aerobic glycolysis phenotype in tumor cells, the characterization of cancer cell metabolism has made huge progress with increasing research attention in recent years (21). BRAF is an ATP-dependent cytosolic kinase that regulates the MAPK (MEK1/2 and ERK1/2) signaling pathway; the BRAFV600E-MEK-ERK pathway is characterized by the loss of negative feedback inhibition and is potently causative of PTC cell dedifferentiation (58). Fortunately, BRAFV600E-selective inhibitors (e.g., vemurafenib) are clinically available for treatment of BRAFV600E-positive tumor patients; however, drug resistance mechanisms are still an important issue in oncology (6,9,10,19,59). Balance and inter-functions between de novo lipid synthesis (e.g., FAS) and FAO, and their connection to prime genetic events such as the BRAFV600E mutation, still need to be deeply investigated. Lipids are an important energy resource for cells: They are crucial for membrane biogenesis, and their oxidative catabolism provides ATP and reducing equivalents in the form of NADH, both of which are essential to controlling environmental stress and promoting survival (25,28). ACC2 expression was downregulated in BRAFV600E-PTC clinical samples and in BRAFV600E-PTC-derived cell lines compared with BRAFWT-PTC, whereas ACC1 levels were not. We also found an upregulation of ACC2 mRNA levels (and to a lesser extent ACC1) in a BRAFV600E allelic-dosage-dependent manner in PTC-derived cells when treated with vermurafenib. So it is likely that ACC genes' expression is influenced by the BRAFV600E pathway. Further studies will be needed to test this mechanism-based hypothesis and the role of ACC2 in primary resistance exhibited by BRAFV600E-PTC cells. The IP of ACC2 indicated that its phosphorylation may occur only in BRAFV600E-PTC-derived cells, suggesting that BRAFV600E may also orchestrate post-translational regulations of ACC2 (and ACC1, in part). Intriguingly, levels of phosphorylated (p) ACC (known to be inactive) increased in both heterozygous and homozygous BRAFV600E tumor cells when we used vemurafenib. However, the majority of ACC2 levels may be nonphosphorylated in BRAFV600E-PTC cell lines, as suggested by our IP studies, which showed that most of the phosphorylation targeted the ACC1 protein. Therefore, it is likely that ACC2 is functionally more active than inactive (because less phosphorylated), and it contributes to downregulation of FAO and upregulation of de novo lipid synthesis. This may lead to decreased tumor cell survival. Phosphorylated ACC showed a positive trend with levels of phosphorylated AMPK, which is a crucial energy sensor that works as a metabolic checkpoint for most eukaryotic cells (60). A critical metabolic function of all cells is balancing ATP consumption and ATP production. AMPK is a highly conserved sensor of intracellular adenosine nucleotide levels that is activated when reductions in ATP production determine relative increases in AMP or ADP. One major mechanism of AMPK includes phosphorylation of ACC1 and ACC2 to inhibit FAS and promote FAO (61). Moreover, AMPK can be activated by direct phosphorylation (Thr-172 of AMPKalpha) from the tumor suppressor LKB1 serine/threonine kinase (62). Interestingly, the AMPK pathway and its target pACC are upregulated in PTC compared with NT samples (63). Early in vemurafenib treatment, BRAFV600E PTC-derived cell lines reversed their metabolic phenotype: de novo lipogenesis increased and FAO due to OCR decreased along with ECAR rates. This metabolic mechanism may counterbalance potential over-activation of oxidative stress (i.e., ROS levels), which may lead to cytotoxicity toward BRAFV600E-thyroid tumor cells. Critically, knockdown of ACC2 levels led to significantly increased BRAFV600E tumor cell proliferation and ROS production during vemurafenib therapy, indicating that silencing of this gene may enhance tumor survival and proliferation. Importantly, our xenograft mouse data further showed that human BRAFV600E-thyroid tumor cells became less responsive to vemurafenib within two weeks, and they ultimately exhibited increased tumor growth when the ACC2 gene was knocked down. Meanwhile, overexpression of ACC2 (but not ACC1) led to strong inhibition of proliferation in PTC-derived cell lines. The role of ROS in cell biology emerges as a double-edged sword, as ROS can trigger tumor cell proliferation or death. There is evidence that cellular levels of ROS are of critical importance in thyroid carcinoma (64). What matters most regarding ROS depends on the threshold required for its maintenance in tumor cells.

Collectively, our work has demonstrated for the first time that the downregulation of ACC2 levels via BRAFV600E plays a critical role in PTC-derived cells, and establishes favorable conditions for thyroid tumor cell proliferation. These findings suggest a potential link between BRAFV600E and lipid metabolism regulation in PTC. Silencing of ACC2 may contribute to BRAFV600E inhibitor (e.g., vemurafenib) resistance and increased tumor growth. ACC2 rescue may represent a novel molecular strategy for overcoming resistance to BRAFV600E inhibitors.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Rork Kuick (University of Michigan) for downloading and organizing (see details in Materials and Methods) ACACA (ACC1) and ACACB (ACC2) TCGA copy number and RNA-seq data. Veronica Valvo was recipient of a PhD fellowship from the MIUR and UCSC (Roma, Italy). The authors thank Stephanie Li and Elizabeth McGonagle (undergraduate students) for technical assistance. They thank Maria Ericsson (Harvard Medical School, Boston) for the cell block preparation for the transmission electron microscopy.

Authors' Contributions

Conception and design: C.N.; Writing the article: V.V. and C.N.; Editing the article: all authors; Revision of the article: all authors; Development of methodology: V.V., A.I., T.R.K., C.P., Z.Z., X.L., and C.N.; Acquisition of data: V.V., A.I., T.R.K., C.P., Z.Z., I.E.S., S.D.B., X.L., and C.N.; Analysis and interpretation of data: all authors.

Author Disclosure Statement

Carmelo Nucera was NIH ad hoc peer reviewer. No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed by the other authors.

Funding Information

Carmelo Nucera (Principal Investigator, Human Thyroid Cancers Preclinical and Translational Research at the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center [BIDMC/Harvard Medical School]) was awarded grants by the National Cancer Institute/National Institutes of Health (1R01CA181183-01A1 and R01CA248031-01), the American Thyroid Association (ATA), and ThyCa:Thyroid Cancer Survivors Association Inc., for Thyroid Cancer Research. Carmelo Nucera was also a recipient of the BIDMC/CAO Grant (Boston, MA).

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Lim H, Devesa SS, Sosa JA, Check D, Kitahara CM. 2017. Trends in thyroid cancer incidence and mortality in the United States, 1974-2013. JAMA 317:1338–1348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lloyd RV, Osamura RY, Klöppel G, Rosai J. 2017. WHO Classification of Tumours of Endocrine Organs. Available at https://www.iarc.who.int/news-events/who-classification-of-tumours-of-endocrine-organs/ (accessed June 28, 2017).

- 3. Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network 2014. Integrated genomic characterization of papillary thyroid carcinoma. Cell 159:676–690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Xing M, Alzahrani AS, Carson KA, Viola D, Elisei R, Bendlova B, Yip L, Mian C, Vianello F, Tuttle RM, Robenshtok E, Fagin JA, Puxeddu E, Fugazzola L, Czarniecka A, Jarzab B, O'Neill CJ, Sywak MS, Lam AK, Riesco-Eizaguirre G, Santisteban P, Nakayama H, Tufano RP, Pai SI, Zeiger MA, Westra WH, Clark DP, Clifton-Bligh R, Sidransky D, Ladenson PW, Sykorova V. 2013. Association between BRAF V600E mutation and mortality in patients with papillary thyroid cancer. JAMA 309:1493–1501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Xing M, Westra WH, Tufano RP, Cohen Y, Rosenbaum E, Rhoden KJ, Carson KA, Vasko V, Larin A, Tallini G, Tolaney S, Holt EH, Hui P, Umbricht CB, Basaria S, Ewertz M, Tufaro AP, Califano JA, Ringel MD, Zeiger MA, Sidransky D, Ladenson PW. 2005. BRAF mutation predicts a poorer clinical prognosis for papillary thyroid cancer. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 90:6373–6379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Solit DB, Rosen N. 2011. Resistance to BRAF inhibition in melanomas. N Engl J Med 364:772–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Byeon HK, Na HJ, Yang YJ, Kwon HJ, Chang JW, Ban MJ, Kim WS, Shin DY, Lee EJ, Koh YW, Yoon JH, Choi EC. 2016. c-Met-mediated reactivation of PI3K/AKT signaling contributes to insensitivity of BRAF(V600E) mutant thyroid cancer to BRAF inhibition. Mol Carcinog 55:1678–1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Byeon HK, Na HJ, Yang YJ, Ko S, Yoon SO, Ku M, Yang J, Kim JW, Ban MJ, Kim JH, Kim DH, Kim JM, Choi EC, Kim CH, Yoon JH, Koh YW. 2017. Acquired resistance to BRAF inhibition induces epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in BRAF (V600E) mutant thyroid cancer by c-Met-mediated AKT activation. Oncotarget 8:596–609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Knauf JA, Luckett KA, Chen KY, Voza F, Socci ND, Ghossein R, Fagin JA. 2018. Hgf/Met activation mediates resistance to BRAF inhibition in murine anaplastic thyroid cancers. J Clin Invest 128:4086–4097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Montero-Conde C, Ruiz-Llorente S, Dominguez JM, Knauf JA, Viale A, Sherman EJ, Ryder M, Ghossein RA, Rosen N, Fagin JA. 2013. Relief of feedback inhibition of HER3 transcription by RAF and MEK inhibitors attenuates their antitumor effects in BRAF-mutant thyroid carcinomas. Cancer Discov 3:520–533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sos ML, Levin RS, Gordan JD, Oses-Prieto JA, Webber JT, Salt M, Hann B, Burlingame AL, McCormick F, Bandyopadhyay S, Shokat KM. 2014. Oncogene mimicry as a mechanism of primary resistance to BRAF inhibitors. Cell Rep 8:1037–1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Boussemart L, Malka-Mahieu H, Girault I, Allard D, Hemmingsson O, Tomasic G, Thomas M, Basmadjian C, Ribeiro N, Thuaud F, Mateus C, Routier E, Kamsu-Kom N, Agoussi S, Eggermont AM, Desaubry L, Robert C, Vagner S. 2014. eIF4F is a nexus of resistance to anti-BRAF and anti-MEK cancer therapies. Nature 513:105–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hanly EK, Bednarczyk RB, Tuli NY, Moscatello AL, Halicka HD, Li J, Geliebter J, Darzynkiewicz Z, Tiwari RK. 2015. mTOR inhibitors sensitize thyroid cancer cells to cytotoxic effect of vemurafenib. Oncotarget 6:39702–39713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Poulikakos PI, Persaud Y, Janakiraman M, Kong X, Ng C, Moriceau G, Shi H, Atefi M, Titz B, Gabay MT, Salton M, Dahlman KB, Tadi M, Wargo JA, Flaherty KT, Kelley MC, Misteli T, Chapman PB, Sosman JA, Graeber TG, Ribas A, Lo RS, Rosen N, Solit DB. 2011. RAF inhibitor resistance is mediated by dimerization of aberrantly spliced BRAF(V600E). Nature 480:387–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Johnson DB, Menzies AM, Zimmer L, Eroglu Z, Ye F, Zhao S, Rizos H, Sucker A, Scolyer RA, Gutzmer R, Gogas H, Kefford RF, Thompson JF, Becker JC, Berking C, Egberts F, Loquai C, Goldinger SM, Pupo GM, Hugo W, Kong X, Garraway LA, Sosman JA, Ribas A, Lo RS, Long GV, Schadendorf D. 2015. Acquired BRAF inhibitor resistance: a multicenter meta-analysis of the spectrum and frequencies, clinical behaviour, and phenotypic associations of resistance mechanisms. Eur J Cancer 51:2792–2799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wang W, Kang H, Zhao Y, Min I, Wyrwas B, Moore M, Teng L, Zarnegar R, Jiang X, Fahey TJ, 3rd 2017. Targeting autophagy sensitizes BRAF-mutant thyroid cancer to vemurafenib. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 102:634–643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Duquette M, Sadow PM, Husain A, Sims JN, Antonello ZA, Fischer AH, Song C, Castellanos-Rizaldos E, Makrigiorgos GM, Kurebayashi J, Nose V, Van Hummelen P, Bronson RT, Vinco M, Giordano TJ, Dias-Santagata D, Pandolfi PP, Nucera C. 2015. Metastasis-associated MCL1 and P16 copy number alterations dictate resistance to vemurafenib in a BRAFV600E patient-derived papillary thyroid carcinoma preclinical model. Oncotarget 6:42445–42467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Antonello ZA, Hsu N, Bhasin M, Roti G, Joshi M, Van Hummelen P, Ye E, Lo AS, Karumanchi SA, Bryke CR, Nucera C. 2017. Vemurafenib-resistance via de novo RBM genes mutations and chromosome 5 aberrations is overcome by combined therapy with palbociclib in thyroid carcinoma with BRAF(V600E). Oncotarget 8:84743–84760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Prete A, Lo AS, Sadow PM, Bhasin SS, Antonello ZA, Vodopivec DM, Ullas S, Sims JN, Clohessy J, Dvorak AM, Sciuto T, Bhasin M, Murphy-Ullrich JE, Lawler J, Karumanchi SA, Nucera C. 2018. Pericytes elicit resistance to vemurafenib and sorafenib therapy in thyroid carcinoma via the TSP-1/TGFbeta1 axis. Clin Cancer Res 24:6078–6097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. 2011. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell 144:646–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pavlova NN, Thompson CB. 2016. The emerging hallmarks of cancer metabolism. Cell Metab 23:27–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Antico Arciuch VG, Russo MA, Kang KS, Di Cristofano A. 2013. Inhibition of AMPK and Krebs cycle gene expression drives metabolic remodeling of Pten-deficient preneoplastic thyroid cells. Cancer Res 73:5459–5472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Medes G, Thomas A, Weinhouse S. 1953. Metabolism of neoplastic tissue. IV. A study of lipid synthesis in neoplastic tissue slices in vitro. Cancer Res 13:27–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Carracedo A, Weiss D, Leliaert AK, Bhasin M, de Boer VC, Laurent G, Adams AC, Sundvall M, Song SJ, Ito K, Finley LS, Egia A, Libermann T, Gerhart-Hines Z, Puigserver P, Haigis MC, Maratos-Flier E, Richardson AL, Schafer ZT, Pandolfi PP. 2012. A metabolic prosurvival role for PML in breast cancer. J Clin Invest 122:3088–3100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Jeon SM, Chandel NS, Hay N. 2012. AMPK regulates NADPH homeostasis to promote tumour cell survival during energy stress. Nature 485:661–665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Carracedo A, Cantley LC, Pandolfi PP. 2013. Cancer metabolism: fatty acid oxidation in the limelight. Nat Rev Cancer 13:227–232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Auciello FR, Bulusu V, Oon C, Tait-Mulder J, Berry M, Bhattacharyya S, Tumanov S, Allen-Petersen BL, Link J, Kendsersky ND, Vringer E, Schug M, Novo D, Hwang RF, Evans RM, Nixon C, Dorrell C, Morton JP, Norman JC, Sears RC, Kamphorst JJ, Sherman MH. 2019. A stromal lysolipid-autotaxin signaling axis promotes pancreatic tumor progression. Cancer Discov 9:617–627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Schafer ZT, Grassian AR, Song L, Jiang Z, Gerhart-Hines Z, Irie HY, Gao S, Puigserver P, Brugge JS. 2009. Antioxidant and oncogene rescue of metabolic defects caused by loss of matrix attachment. Nature 461:109–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kitahara CM, McCullough ML, Franceschi S, Rinaldi S, Wolk A, Neta G, Olov Adami H, Anderson K, Andreotti G, Beane Freeman LE, Bernstein L, Buring JE, Clavel-Chapelon F, De Roo LA, Gao YT, Gaziano JM, Giles GG, Hakansson N, Horn-Ross PL, Kirsh VA, Linet MS, MacInnis RJ, Orsini N, Park Y, Patel AV, Purdue MP, Riboli E, Robien K, Rohan T, Sandler DP, Schairer C, Schneider AB, Sesso HD, Shu XO, Singh PN, van den Brandt PA, Ward E, Weiderpass E, White E, Xiang YB, Zeleniuch-Jacquotte A, Zheng W, Hartge P, Berrington de Gonzalez A. 2016. Anthropometric factors and thyroid cancer risk by histological subtype: pooled analysis of 22 prospective studies. Thyroid 26:306–318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tian Y, Nie X, Xu S, Li Y, Huang T, Tang H, Wang Y. 2015. Integrative metabonomics as potential method for diagnosis of thyroid malignancy. Sci Rep 5:14869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wakil SJ, Titchener EB, Gibson DM. 1958. Evidence for the participation of biotin in the enzymic synthesis of fatty acids. Biochim Biophys Acta 29:225–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hunkeler M, Hagmann A, Stuttfeld E, Chami M, Guri Y, Stahlberg H, Maier T. 2018. Structural basis for regulation of human acetyl-CoA carboxylase. Nature 558:470–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Barber MC, Price NT, Travers MT. 2005. Structure and regulation of acetyl-CoA carboxylase genes of metazoa. Biochim Biophys Acta 1733:1–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Abu-Elheiga L, Jayakumar A, Baldini A, Chirala SS, Wakil SJ. 1995. Human acetyl-CoA carboxylase: characterization, molecular cloning, and evidence for two isoforms. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 92:4011–4015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. McGarry JD, Leatherman GF, Foster DW. 1978. Carnitine palmitoyltransferase I. The site of inhibition of hepatic fatty acid oxidation by malonyl-CoA. J Biol Chem 253:4128–4136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Abu-Elheiga L, Brinkley WR, Zhong L, Chirala SS, Woldegiorgis G, Wakil SJ. 2000. The subcellular localization of acetyl-CoA carboxylase 2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97:1444–1449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ha J, Lee JK, Kim KS, Witters LA, Kim KH. 1996. Cloning of human acetyl-CoA carboxylase-beta and its unique features. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 93:11466–11470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Abu-Elheiga L, Almarza-Ortega DB, Baldini A, Wakil SJ. 1997. Human acetyl-CoA carboxylase 2. Molecular cloning, characterization, chromosomal mapping, and evidence for two isoforms. J Biol Chem 272:10669–10677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hwang IW, Makishima Y, Kato T, Park S, Terzic A, Park EY. 2014. Human acetyl-CoA carboxylase 2 expressed in silkworm Bombyx mori exhibits posttranslational biotinylation and phosphorylation. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 98:8201–8209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Fullerton MD, Galic S, Marcinko K, Sikkema S, Pulinilkunnil T, Chen ZP, O'Neill HM, Ford RJ, Palanivel R, O'Brien M, Hardie DG, Macaulay SL, Schertzer JD, Dyck JR, van Denderen BJ, Kemp BE, Steinberg GR. 2013. Single phosphorylation sites in Acc1 and Acc2 regulate lipid homeostasis and the insulin-sensitizing effects of metformin. Nat Med 19:1649–1654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Zheng B, Jeong JH, Asara JM, Yuan YY, Granter SR, Chin L, Cantley LC. 2009. Oncogenic B-RAF negatively regulates the tumor suppressor LKB1 to promote melanoma cell proliferation. Mol Cell 33:237–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Shimano H, Horton JD, Hammer RE, Shimomura I, Brown MS, Goldstein JL. 1996. Overproduction of cholesterol and fatty acids causes massive liver enlargement in transgenic mice expressing truncated SREBP-1a. J Clin Invest 98:1575–1584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Horton JD, Shah NA, Warrington JA, Anderson NN, Park SW, Brown MS Goldstein JL. 2003. Combined analysis of oligonucleotide microarray data from transgenic and knockout mice identifies direct SREBP target genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100:12027–12032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kusunoki J, Kanatani A, Moller DE. 2006. Modulation of fatty acid metabolism as a potential approach to the treatment of obesity and the metabolic syndrome. Endocrine 29:91–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lenhard JM 2011. Lipogenic enzymes as therapeutic targets for obesity and diabetes. Curr Pharm Des 17:325–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Karantanos T, Karanika S, Wang J, Yang G, Dobashi M, Park S, Ren C, Li L, Basourakos SP, Hoang A, Efstathiou E, Wang X, Troncoso P, Titus M, Broom B, Kim J, Corn PG, Logothetis CJ, Thompson TC. 2016. Caveolin-1 regulates hormone resistance through lipid synthesis, creating novel therapeutic opportunities for castration-resistant prostate cancer. Oncotarget 7:46321–46334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Zhan Y, Ginanni N, Tota MR, Wu M, Bays NW, Richon VM, Kohl NE, Bachman ES, Strack PR, Krauss S. 2008. Control of cell growth and survival by enzymes of the fatty acid synthesis pathway in HCT-116 colon cancer cells. Clin Cancer Res 14:5735–5742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Svensson RU, Shaw RJ. 2016. Lipid synthesis is a metabolic liability of non-small cell lung cancer. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol 81:93–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Corbet C, Pinto A, Martherus R, Santiago de Jesus JP, Polet F, Feron O. 2016. Acidosis drives the reprogramming of fatty acid metabolism in cancer cells through changes in mitochondrial and histone acetylation. Cell Metab 24:311–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. German NJ, Yoon H, Yusuf RZ, Murphy JP, Finley LW, Laurent G, Haas W, Satterstrom FK, Guarnerio J, Zaganjor E, Santos D, Pandolfi PP, Beck AH, Gygi SP, Scadden DT, Kaelin WG Jr., Haigis MC. 2016. PHD3 loss in cancer enables metabolic reliance on fatty acid oxidation via deactivation of ACC2. Mol Cell 63:1006–1020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Corbet C, Feron O. 2017. Emerging roles of lipid metabolism in cancer progression. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 20:254–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Svensson RU, Parker SJ, Eichner LJ, Kolar MJ, Wallace M, Brun SN, Lombardo PS, Van Nostrand JL, Hutchins A, Vera L, Gerken L, Greenwood J, Bhat S, Harriman G, Westlin WF, Harwood HJ Jr., Saghatelian A, Kapeller R, Metallo CM, Shaw RJ. 2016. Inhibition of acetyl-CoA carboxylase suppresses fatty acid synthesis and tumor growth of non-small-cell lung cancer in preclinical models. Nat Med 22:1108–1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Harriman G, Greenwood J, Bhat S, Huang X, Wang R, Paul D, Tong L, Saha AK, Westlin WF, Kapeller R, Harwood HJ Jr. 2016. Acetyl-CoA carboxylase inhibition by ND-630 reduces hepatic steatosis, improves insulin sensitivity, and modulates dyslipidemia in rats. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113:E1796–E1805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Schweppe RE, Klopper JP, Korch C, Pugazhenthi U, Benezra M, Knauf JA, Fagin JA, Marlow LA, Copland JA, Smallridge RC, Haugen BR. 2008. Deoxyribonucleic acid profiling analysis of 40 human thyroid cancer cell lines reveals cross-contamination resulting in cell line redundancy and misidentification. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 93:4331–4341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Castle JC, Hara Y, Raymond CK, Garrett-Engele P, Ohwaki K, Kan Z, Kusunoki J, Johnson JM. 2009. ACC2 is expressed at high levels in human white adipose and has an isoform with a novel N-terminus [corrected]. PLoS One 4:e4369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Aggarwal V, Tuli HS, Varol A, Thakral F, Yerer MB, Sak K, Varol M, Jain A, Khan MA, Sethi G. 2019. Role of reactive oxygen species in cancer progression: molecular mechanisms and recent advancements. Biomolecules 9:735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Warburg O 1956. On the origin of cancer cells. Science 123:309–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Fagin JA, Wells SA Jr. 2016. Biologic and clinical perspectives on thyroid cancer. N Engl J Med 375:1054–1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. McGonagle ER, Nucera C. 2019. Clonal reconstruction of thyroid cancer: an essential strategy for preventing resistance to ultra-precision therapy. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 10:468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Hardie DG 2007. AMP-activated/SNF1 protein kinases: conserved guardians of cellular energy. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 8:774–785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Hardie DG, Pan DA. 2002. Regulation of fatty acid synthesis and oxidation by the AMP-activated protein kinase. Biochem Soc Trans 30(Pt 6):1064–1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Shaw RJ, Kosmatka M, Bardeesy N, Hurley RL, Witters LA, DePinho RA, Cantley LC. 2004. The tumor suppressor LKB1 kinase directly activates AMP-activated kinase and regulates apoptosis in response to energy stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101:3329–3335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Vidal AP, Andrade BM, Vaisman F, Cazarin J, Pinto LF, Breitenbach MM, Corbo R, Caroli-Bottino A, Soares F, Vaisman M, Carvalho DP. 2013. AMP-activated protein kinase signaling is upregulated in papillary thyroid cancer. Eur J Endocrinol 169:521–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Xing M 2012. Oxidative stress: a new risk factor for thyroid cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer 19:C7–C11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.