Abstract

Radical cystectomy is the standard of care for patients with nonmetastatic high-risk bladder cancer. Robotic approach to radical cystectomy has been developed to reduce perioperative morbidities and enhance postoperative recovery while maintaining oncologic control. Classically, radical cystectomy in female patient entails anterior pelvic exenteration with removal of the bladder, uterus, fallopian tubes, ovaries, anterior vaginal wall, and urethra. Pelvic organ-sparing radical cystectomy has been adopted in carefully selected patients to optimize postoperative sexual and urinary function, especially in those undergoing orthotopic urinary diversion. In this article, we describe our techniques of both classical and organ-sparing robot-assisted laparoscopic radical cystectomy in female patients. We also review patient selection criteria, perioperative management, and alternative approaches to improve operative outcomes in female patients.

Keywords: robotic radical cystectomy, female cystectomy, bladder cancer, pelvic organ-sparing radical cystectomy, surgical techniques

Featured Video

https://stream.cadmore.media/player/6e9a79e6-4c23-4edd-abcb-9474ce649a00

Indications

Radical cystectomy is the primary treatment option for nonmetastatic muscle-invasive urothelial carcinoma of the bladder (MIBC).1–3 The current standard of care is to offer cisplatin-eligible patients cisplatin-based neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) before radical cystectomy given demonstrated benefits of NAC on cancer-specific mortality and all-cause mortality rates.4–6 Other indications include non-muscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) with factors associated with high risk of progression to muscle-invasive disease such as variant histology report, carcinoma in situ or lymphovascular invasion7,8 in addition to high-risk NMIBC that persists or recurs despite following two induction cycles of intravesical bacillus Calmette Guerin (BCG) or BCG maintenance.3,9–12 In the context of organ-confined bladder cancer, radical cystectomy encompasses three surgical components—extirpative surgery, bilateral lymphadenectomy, and urinary diversion. Bilateral pelvic lymphadenectomy, including removal of common, internal iliac, external iliac, and obturator nodes, is an important part of a radical cystectomy and has been shown to improve control of local and regional disease and provide better long-term oncologic outcomes.13,14 This report will focus on the techniques and outcomes of the extirpative surgery only.

Open and robot-assisted radical cystectomy (RARC) have comparable oncologic outcomes and complication rates when done at experienced centers. The largest randomized control trial (RCT) to date is the RAZOR trial, which showed that RARC is noninferior to open radical cystectomy (ORC) in terms of 3-year progression-free survival (68.4% vs 65.4%),15 overall survival (73.9% vs 68.5%),15 adverse events (67% vs 69%),16 and quality-of-life (QOL) outcomes.16 A Cochrane review of five other published RCT comparing ORC and RARC showed no difference between two surgical approaches regarding time to recurrence, positive surgical margin rates, major postoperative complications, and QOL. The study found RARC may result in lower transfusion rate and shorter hospital stay.17 For both approaches, surgeon experience and institutional volume strongly predict surgical outcomes.18 The choice of surgical approach should be based on the surgeon's experience with RARC, other previous robot-assisted surgeries, or the presence of an experienced mentor to train junior surgeons.

Classical radical cystectomy in a female patient includes total anterior pelvic exenteration inclusive of the bladder, uterus, fallopian tubes, ovaries, anterior vaginal wall, and urethra.1 Since the early 2000s, adoption of orthotopic neobladder (ONB) in women and an effort to improve postoperative sexual and urinary function have motivated urologists to explore less radical surgery. This effort is supported by the fact that direct involvement of the gynecologic organs at the time of radical cystectomy only occurs in around 2.6%–7.5% of women.19–22 Pelvic organ-sparing radical cystectomy (POSRC) refers to the preservation of the uterus, fallopian tubes, ovaries, and anterior vagina, and urethra. The most important factor in choosing to preserve organs is that cancer control is not compromised. Patient selection, therefore, is paramount.

Selection of appropriate candidates for POSRC relies on a thorough preoperative evaluation, including gynecologic history, menopausal status, history of cervical cancer screening, abnormal vaginal bleeding, family history of breast/ovarian cancer, sexual function, and, if applicable, fertility goal. Patients who may benefit most from POSRC are those with good baseline functional status and surgical fitness (usually those of younger age but advanced age is not a contraindication), pre- or perimenopausal, sexually active, and in whom an ONB is planned. Relative contraindication may be those at risk of hereditary ovarian, endometrial, and cervical cancer such as BRCA1/2 mutation carriers and those with Lynch syndrome. Risk-reduction surgeries such as hysterectomy and salpingo-oophorectomy after childbearing and over the age of 40 have been recommended for these patients; thus, they are not appropriate candidates for POSRC.23,24 Bimanual examination under anesthesia must be performed before and after transurethral resection of bladder tumor (TURBT) for clinical staging and evaluation of concomitant gynecologic condition such as pelvic organ prolapse. TURBT must take note of tumor location, specifically evaluating for tumor involvement of the bladder base, trigone, and bladder neck, and ensure adequate sampling of the muscularis propria. Oncologic criteria for POSRC include unifocal organ-confined ≤cT2 tumor that is away from the bladder neck or trigone. The primary oncologic contraindication for POSRC and ONB is the presence of urothelial carcinoma at the urethral margin on intraoperative frozen section at the time of radical cystectomy. Relative contraindications include palpable tumor on bimanual examination and preoperative hydronephrosis.

Preoperative Preparation

The preoperative work-up for a patient with bladder tumor starts with a detailed history and physical examination followed by urine cytology, examination under anesthesia, and TURBT as described in previous section. Screening for smoking and initiation of treatment for smoking cessation should be done at the initial evaluation. Laboratory studies, such as complete blood count, chemistry profile, alkaline phosphatase, and a coagulation panel must be performed. Assessment of the upper tract can be done with CT or MRI urography or retrograde ureteropyelography at the time of transurethral resection. Complete staging evaluation includes imaging of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis with either CT or MRI. Bone and brain imaging are only done if patient has clinical symptoms or laboratory indicators, such as abnormal alkaline phosphatase, concerning for bone or brain metastases. Patient should be counseled regarding different types of urinary diversion, possible complications, risks, benefits, and anticipated lifestyle and psychologic changes. Patient should meet with an enterostomal therapist and have stoma site marking preoperatively even when ONB is planned.

Patients follow a standardized enhanced recovery clinical care pathway involving preoperative preparation and postoperative management. Preoperative bowel preparation depends on the segment of bowel used for planned urinary diversion. Patients undergoing small bowel diversion do not receive any bowel preparation. For urinary diversion using colon, patient receive a mechanical bowel preparation with magnesium citrate. All patients are placed on a clear liquid diet and carbohydrate loading for 24 hours before surgery. Patients receive one dose of alvimopan, a μ-opioid receptor antagonist, just before surgery to accelerate gastrointestinal recovery after surgery unless there is a contraindication, such as the use of therapeutic doses of opioids for more than seven consecutive days immediately before the starting dose.1,25 A regional transversus abdominis plane (TAP) block is placed in the preoperative area. Patients receive perioperative antibiotics in accordance with the American Urological Association (AUA) Antimicrobial Prophylaxis guideline.26 Unless a drug allergy to cephalosporins is present, the authors typically administer cefotetan within 60 minutes of incision. Patients are placed on mechanical and pharmacologic prophylaxis, that is, intermittent pneumatic compression on lower extremities and subcutaneous heparin, before induction of general anesthesia to prevent thromboembolic complications.1,27

Patient Positioning

After general anesthesia induction, a nasogastric or orogastric tube is placed to decompress the stomach intraoperatively and removed at the completion of the procedure. The patient is placed in supine split-leg position with the arms tucked to the side. Care must be taken to ensure all pressure points are adequately padded. The patient is secured to the operating table with nonslipping pad and chest strap. The patient will be in 28° steep Trendelenburg position during the case, which displaces the bowel cephalad and provides easy access to the pelvis. After patient is positioned and secured to the table, the table is tilted temporarily to steep Trendelenburg position to ensure that patient does not slide toward the head of the table and patient's ventilatory dynamics tolerate the extreme position. The table is then put back in neutral position for port placement.

The patient is prepped and draped from the xiphoid process to the perineum, including the vagina, and lateral to the bilateral anterior axillary lines. An 18F urethral catheter is placed in the sterile field.

Surgical Steps

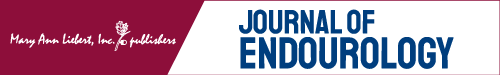

Port placement

A total of six ports are used during the procedure as shown in Figure 1. The 8-mm camera port is positioned ∼5 cm cephalad to the umbilicus. After the camera port placement, a 30° robotic camera is inserted. The abdomen is inspected for injury or adhesion. Subsequent ports are placed under direct observation. Three 8-mm robotic ports are placed in a horizontal line 1 fingerbreadth caudal to the camera port. The left and right ports are approximately one handbreadth from the midline. The right lateral port for the fourth robotic arm is placed at the level of the anterior axillary line. A 12-mm AirSeal® assistant port (ConMed) is placed in the left upper quadrant and another 12-mm assistant port is placed in the left anterior axillary line at the level of the umbilicus. The patient is then placed in 28° steep Trendelenburg position.

FIG. 1.

da Vinci Xi port configuration for radical cystectomy with surgical assistant positioned on the patient's left side. C = camera port.

The da Vinci Xi (Intuitive Surgical) robotic system is docked with the surgical assistant operating from the patient's left side. We utilize fenestrated bipolar in the left robotic arm, monopolar scissors in the right arm, and a Vessel Sealer in the fourth robotic arm.

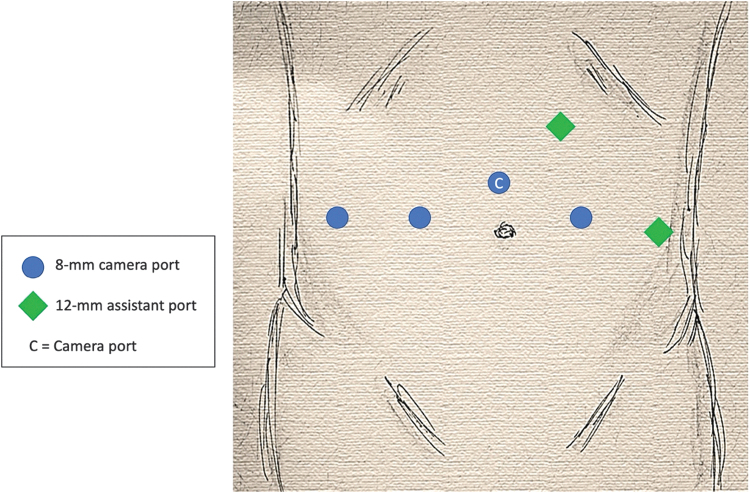

Mobilization and division of the ureters

A 30° lens is used during the procedure. Once ports are placed, the surgeon should orient to the female pelvic anatomy. Dissection usually proceeds with identification and mobilization of the left ureteral (Supplementary Video S1). We incise the white line of Toldt and develop the relatively avascular plan to separate the left colon from the pelvic side wall and reflect the sigmoid colon medially and superiorly out of the surgical field. The left ureter is identified as it crosses the left common iliac artery. The peritoneum overlying the ureter is incised. The ureter is freed from its surrounding structures while preserving adequate periureteral tissue to maintain the vascular supply to the ureter. As the ureter is dissected distally, the adnexa are lifted cephalad, along with the infundibulopelvic (IP) suspensory ligament. The ureter is mobilized distally to the level of the uterine artery, which courses medially and over the ureter. The pelvic vasculature is shown in Figure 2. The ureter is then doubly ligated with locking clips and transected without thermal energy. A suture may be pretied to the crotch of the proximal clip to facilitate its identification and mobilization during the urinary diversion portion. The ureter is dissected free of its cephalad attachments enough to reach the urinary diversion reconstruction. Excess dissection of the ureter should be avoided to minimize devascularization of the ureter. The right ureter is mobilized and divided using a similar technique.

FIG. 2.

Right pelvic vasculature in relation to right distal ureter. The ureter is seen coursing over the right common iliac artery and anterior to the hypogastric artery (also known as internal iliac artery).

Anterior pelvic exenteration

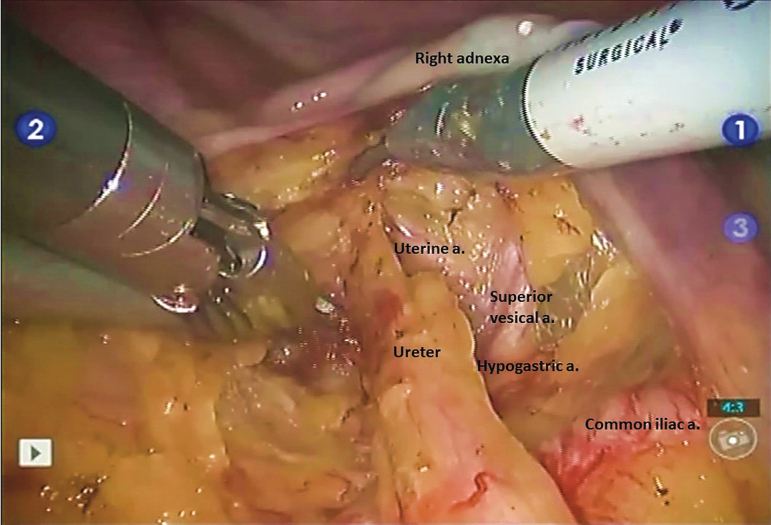

Posterior dissection of the bladder, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, and hysterectomy (Supplementary Video S2, Part 1)

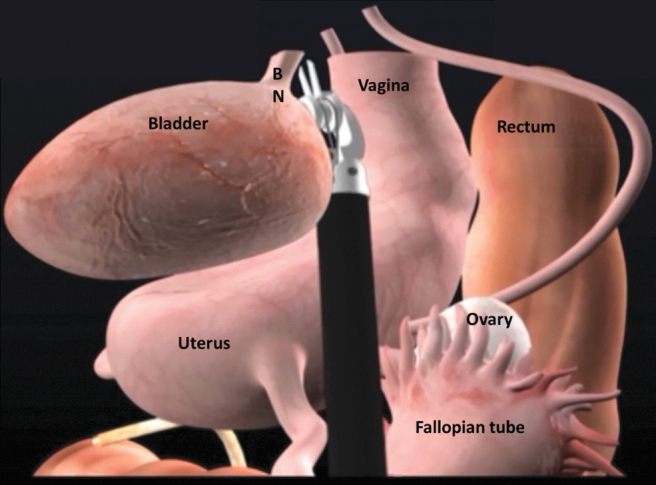

If present, the female pelvic organs can be identified as demonstrated in Figure 3. A medium end anastomosis (EEA) sizer is used for uterine manipulation. Alternatively, a sponge stick can be used. The peritoneum over the vesicouterine pouch is incised. The plane between the anterior vagina and the posterior bladder is developed and continues distally to the level of the bladder neck. With the uterus anteverted and laterally displaced to the contralateral side, the IP suspensory ligament, the ovarian pedicles, and the broad ligaments are identified and divided with the Vessel Sealer. The uterine arteries are ligated with locking clips and divided. Next, peritoneum lateral to the medial umbilical ligaments is incised from the anterior abdominal wall to join the peritoneal dissection over the broad ligament. The paravesical space can be developed with blunt dissection and carried caudally to expose the endopelvic fascia. Next with the uterus anteverted, the peritoneum over the rectouterine pouch is incised and connected with the lateral dissection. This step helps to define the bladder pedicles. In the absence of any cervical pathology report, transcervical hysterectomy may be performed if desired to maximize vaginal length. With the aid of a sponge stick in the vagina, the uterine fundus is transected at the level of the posterior fornix at the level of the cervical insertion. Posterior dissection continues caudally to the level of the bladder neck.

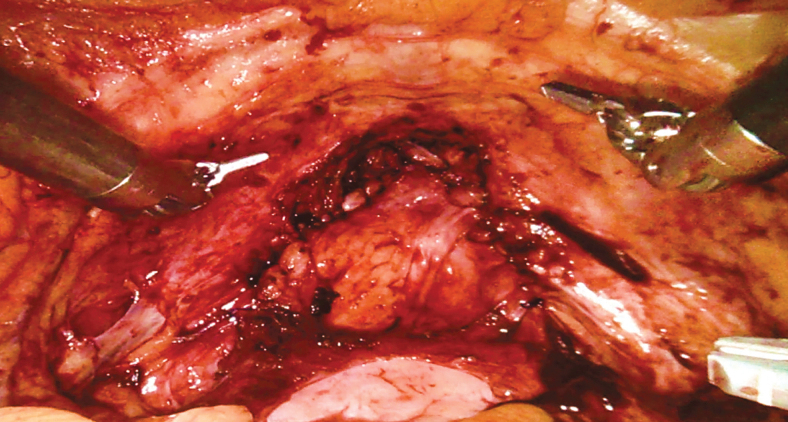

FIG. 3.

Intraoperative view of the female pelvis.

Division of the Bladder Pedicles

Using the fourth arm to retract the bladder anteriorly, the bladder pedicles are placed on stretch and away from the external iliac vessels. The superior vascular pedicles to the bladder are divided using the Vessel Sealer or locking clips (Supplementary Video S3). Branches from the inferior pedicles are then identified, separated into small packets, sealed or clipped, and divided. Connective tissues and small perforating arteries can be dissected and controlled with electrocautery.

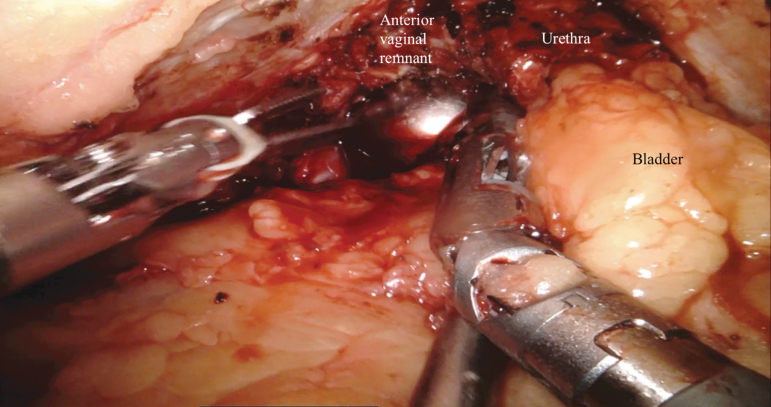

Anterior Dissection of the Bladder and Division of the Urethra

Next, anterior dissection of the bladder is performed. The median umbilical ligament is divided as proximally as possible with electrocautery. The dissection is carried caudally over the anterior surface of the bladder to the pubic symphysis to develop the space of Retzius. The location of the bladder neck can be identified using the balloon of the Foley catheter for reference. The dorsal venous complex (DVC) anterior to the urethra is divided sharply. Hemostasis can be achieved with bipolar cautery or a DVC stitch. Complete urethrectomy can be performed intracorporeally (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Video S4, Part 1). If an orthotopic urinary diversion is planned, the urethra is transected sharply without electrocautery just distal to the bladder neck to ensure preservation of a functional urethral stump. Once the urethra is transected, the urethral catheter is clamped with a locking clip before division to minimize the risk of tumor spillage. The specimen is placed in a 15-mm specimen bag and extracted through the vaginotomy.

FIG. 4.

Antegrade anterior vaginectomy and urethral dissection. An EEA sizer is used to identify the vaginal wall and maintain pneumoperitoneum. EEA = end anastomosis.

Pelvic organ-sparing radical cystectomy

Modifications to classical radical cystectomy are described hereunder for ONB reconstruction (Supplementary Video S2, Part 2). By definition, an adequate urethral stump is required for ONB. Sparing the vagina, uterus, and their supporting structures improves voiding function by preserving support for the ONB, preventing its backward displacement and angulation of the neobladder-urethral anastomosis.28–30 In addition, preservation of the vagina and uterus help to preserve the autonomic nerves along the lateral wall of the vagina, which may help to improve voiding and sexual function outcomes.30

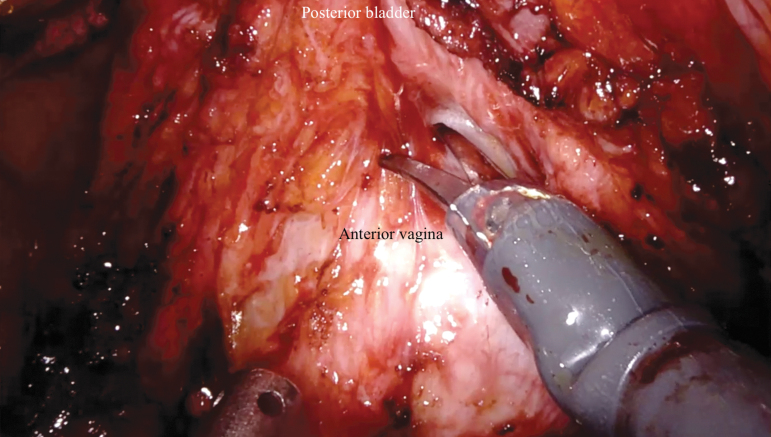

Dissection of the anterior vaginal wall

After the ureters are mobilized, the uterus is retroverted, the peritoneum over the vesicouterine pouch is incised transversely. With the bladder lifted anteriorly, the avascular plan between the anterior surface of the uterus/vagina and the posterior surface of the bladder is developed (Fig. 5). The dissection continues caudally to the level of the bladder neck as illustrated in Figure 6. Care should be taken with dissection around the cervix because there are dense connective tissues at this point. Thinning of the anterior vaginal wall or the bladder should be avoided. With the anterior vagina separated from the posterior bladder, the lateral perivaginal space is developed bilaterally.

FIG. 5.

Avascular plan between anterior vagina and posterior bladder wall. An EEA sizer is used for vaginal manipulation.

FIG. 6.

Schematic illustration of posterior bladder dissection in POSRC. BN = bladder neck; POSRC = pelvic organ-sparing radical cystectomy.

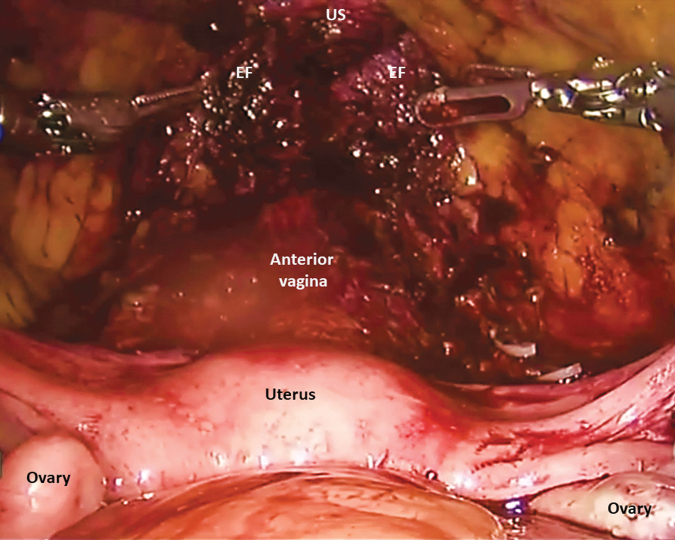

Preservation of the uterus and supporting ligaments

The uterus, the cardinal ligaments containing the uterine arteries, and supporting ligaments are spared (Fig. 7). The previously transected distal ureter is dissected free and delivered under the uterine artery to preserve the cardinal ligament. Limited dissection of the uterus is performed posteriorly, leaving the uterosacral ligaments undisturbed.

FIG. 7.

View of the pelvis after organ-sparing cystectomy has been performed. EF = endopelvic fascia and pubourethral ligament are intact; US = urethral stump.

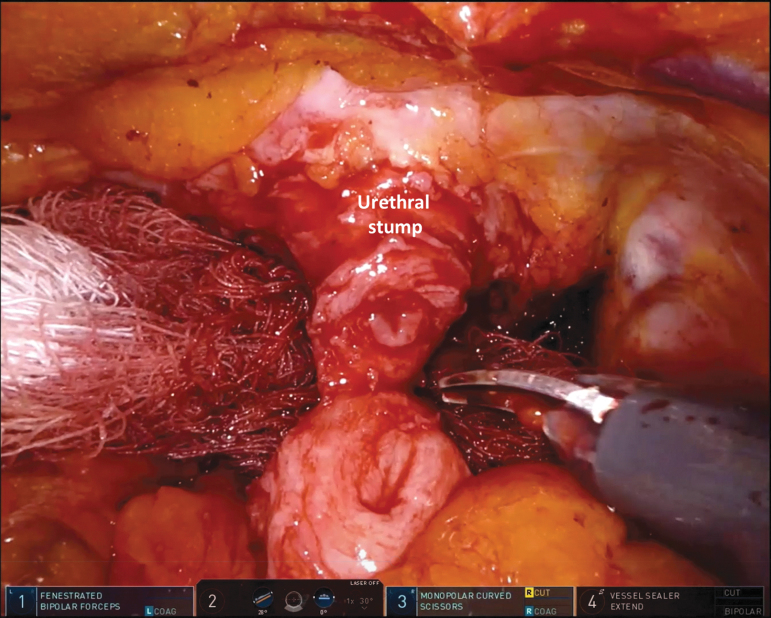

Preservation of the Vagina, Urethra, and Periurethral Tissue

The distal dissection of the bladder neck and proximal urethra is carefully performed to preserve the anterior vagina and periurethral support (Supplementary Video S4, Part 2). The endopelvic fascia is identified, preserved, and serves as a reference for the pelvic floor. Dissection continues anterior to this plane in a caudal direction. Once the bladder neck is separated from the anterior vagina distally, the bladder is mobilized anteriorly as described in the previous section. The location of the bladder neck can be identified using the balloon of the urethral catheter for reference. Connective tissue attachment can be separated using sharp dissection and electrocautery. The DVC is divided sharply anteriorly. Care is taken to preserve the endopelvic fascia and supporting periurethral attachment to the distal third of the urethra to optimize continence with ONB reconstruction (Fig. 8). Once the urethra is transected sharply, the urethral catheter is clamped with a locking clip and divided to minimize risk of tumor spillage. Circumferential full-thickness proximal urethral margin is sent for intraoperative frozen section to rule out malignancy at the urethra margin. Since the vagina is not opened, the specimen is placed in an endocatch bag. The opening of the bag is closed with double locking clips to prevent any tumor spillage and placed in the abdomen. Our techniques of robotic pelvic lymphadenectomy and intracorporeal urinary diversion have been described previously.31–33

FIG. 8.

A functional urethral stump, periurethral supporting tissue attachment to the distal third of the urethra, and the endopelvic fascia should be preserved in patients undergoing ONB. ONB = orthotopic neobladder.

Vaginal Reconstruction

Some posterior dissection of the vagina may need to be performed to bring the posterior vaginal wall toward the anterior remnant for vaginal closure (Supplementary Video S5). The vaginal reconstruction can be performed in a clamshell manner with two layers of running absorbable sutures as shown in Figure 9. Rolling the vaginal remnant into a tube in an effort to preserve vaginal length without adequate preservation of the anterolateral walls can lead to a narrow vaginal canal that is not suitable for sexual intercourse and higher risk of breakdown. At the completion of vaginal reconstruction, manual examination should be done to ensure the vaginal defect is completely closed and intact.

FIG. 9.

Vaginal reconstruction in clamshell manner.

Potential Additional Reconstructive Steps for ONB

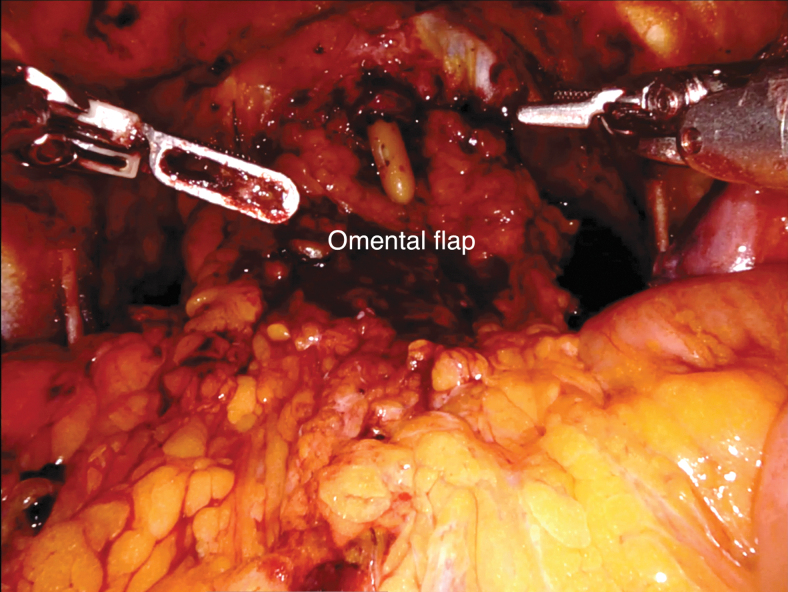

Pedicled omental flap

Neobladder-vaginal fistula has been reported in women undergoing classical radical cystectomy at a rate of 3%–5%.28,34–36 Although neobladder-vaginal fistula is uncommon in POSRC, there are additional steps that can prevent the risk of fistula. First, care must be taken to avoid overlapping suture lines between the vagina and bladder neck. Second, a pedicled omental flap can be harvested to reinforce the vaginal closure and act as an interposing layer between the vaginal stump and urethro-ileal anastomosis, especially in the case of prior pelvic radiation (Supplementary Video S6). An omental flap is easy to harvest and has a reliable blood supply. The greater omentum is dissected from the transverse coon and greater curvature of the stomach to form an omental flap based on the left or right gastroepiploic artery, whereas retaining the gastroepiploic arch. The flap is then tunneled to the pelvic floor and secured to the endopelvic fascia with absorbable barbed suture (Fig. 10).

FIG. 10.

Pedicled omental flap is brought down to the pelvis to reinforce the vaginal closure and interposes between the vagina and urethro-ileal anastomosis in case of ONB.

Sacrocolpopexy

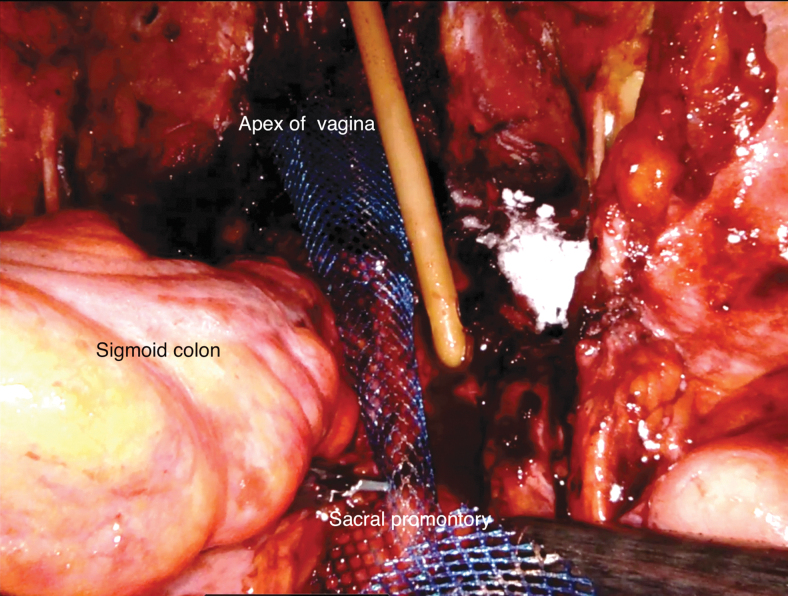

In patients with prior hysterectomy or those who require classical radical cystectomy, the removal of reproductive organs and their supporting tissues may result in weakening of the pelvic floor and may put patients at risk of bowel herniation through the vaginal wall. In addition, patients who undergo ONB after classical radical cystectomy may be at high risk of urinary retention, potentially from angulation of the neobladder-urethral anastomosis caused by backward displacement of the neobladder. One way to reduce the risk of pelvic organ prolapse and urinary retention in patients who undergo ONB is to perform concomitant abdominal sacropolpopexy after RARC and pelvic lymph node dissection are completed (Supplementary Video S7). The sigmoid colon is retracted atraumatically to the left side to expose the sacral promontory. An incision is made in the posterior peritoneum over the sacral promontory to expose the anterior spinous ligament, extending caudally along the right lateral aspect of the rectum to the posterior vagina to create a longitudinal peritoneal flap. Using an EEA sizer as vaginal probe to identify the apex of the vagina, the anterior leaflet of a Y-shaped soft polypropylene mesh is sutured to the anterior vaginal remnant using a running 2–0 barbed suture. The posterior leaflet of the mesh is sutured to the posterior vaginal remnant in a similar manner. The tail of mesh is then secured to the anterior spinous ligament at the level of the sacral promontory using interrupted nonabsorbable sutures such as 2–0 Gore-tex suture. Care must be taken to avoid suturing the middle sacral vessel traversing over the promontory and excessive tension of the mesh. The previously created peritoneal flap is then used to cover the mesh using running 2–0 Vicryl sutures (Fig. 11).

FIG. 11.

Suspension of the vaginal apex to the sacral promontory using a Y-shaped polypropylene mesh.

Postoperative care

All patients follow a standardized enhanced recovery after cystectomy pathway postoperatively. Components of this pathway include removal of nasogastric/orogastric tube at the end of the procedure before the patient leaves the operating room, discontinuation of antibiotics within 24 hours, early enteral feeding, aggressive mobilization and incentive spirometry, active prevention of nausea, narcotic-sparing multimodal pain management, and prophylaxis of thromboembolic events. Patients are started on sips of water and ice chips on the day of surgery. They are subsequently advanced to full liquid diet on postoperative day (POD) 1 and regular diet on POD 2 or 3 if patient tolerates full liquid without abdominal distention or nausea. Selective opioid receptor blockade with alvimopan is initiated preoperatively and continued until return of bowel function for up to 14 doses postoperatively. Patients are mobilized out of bed on POD 0. Ambulation with assistance begins on POD1. Narcotic-sparing pain management regimen composes of TAP block preoperatively, scheduled acetaminophen, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medication, and gabapentin. Oral and intravenous opioid medication may be given as needed for breakthrough pain. Gastrointestinal prophylaxis with a proton pump inhibitor and deep venous thrombosis (DVT) prophylaxis with low molecular weight heparin are instituted immediately postoperatively. Pharmacologic DVT prophylaxis is continued for 28 days in the postoperative period.

Early postoperative rehabilitation program includes inpatient evaluation and education by wound ostomy nurses (if applicable), physical, occupational, and respiratory therapists. Postoperative follow-up and drain management are based on the type of urinary diversion patients undergo.

Troubleshooting

The Pasadena consensus panel on best practices in RARC suggested that there is no absolute contraindication for RARC.18 The panel recognizes that there are certain challenging cases that should be performed by surgeons with extensive experience in RARC. These cases include obese patients, those with multiple prior lower abdominal surgeries, and those with prior pelvic radiation. Prior studies have shown that obese patients have similar operative times, blood loss, and complication rates as patients with normal body mass index undergoing RARC.37,38 In general, the authors have not found the need to modify our technique in obese patients and the use of bariatric trocars is rarely necessary. On the contrary, RARC in obese patients may help to circumvent some of the challenges with surgical exposure and access to the deep pelvis encountered during ORC. Patients with prior abdominal surgeries may have significant adhesion. Hasson technique is preferred for access during initial insufflation and trocar placement. Extensive laparoscopic or robotic lysis of adhesion may be needed before complete trocar placement. In case of prior pelvic radiation, care should be taken with posterior dissection to avoid rectal injury. In addition, patients should be counseled on the increased risk of complications and urinary function after ONB caused by poor tissue qualities from prior radiation.39,40

Outcomes

Retrospective studies and prospective RCT have compared oncologic outcomes and complication rates between RARC and ORC. ORC and RARC have comparable oncologic controls and complication rates; RARC is associated with lower blood loss, transfusion rate, and shorter hospital stay.16,18,41 There is a paucity of studies comparing classical radical cystectomy and POSRC cystectomy in female patients, even more limited data with robotic approach. Similarly, functional outcomes among women undergoing radical cystectomy for bladder cancer are poorly studied. In a systematic review by Smith et al., only 40% of studies assessed sexual function in women using validated questionnaires.42 Table 1 summarizes oncologic, urinary function, and sexual function outcomes from select retrospective studies of women undergoing POSRC and ONB urinary diversion.

Table 1.

Oncologic, Urinary Function, and Sexual Function Outcomes in Women Undergoing Pelvic Organ-Sparing Radical Cystectomy

| Study | No. of patients | Surgical approach | Median follow-up, months (range) | Oncologic outcomes |

Urinary function |

Sexual function |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Local recurrence, n (%) | Distant metastasis, n (%) | 5-year DSS, % | 5-year OS, % | Daytime continence, n (%) | Night-time continence, n (%) | CIC, n (%) | Sexual activity, n (%) | Satisfaction, n (%) | Mean FSFI | ||||

| Koie et al.29 | 30 | Open | 35.1 (4–98) | 1 (3) | 5 (17) | 70 | NR | 28 (93) | 24 (80) | 0 | NR | NR | NR |

| Ali-El-Dein et al.30 | 15 | Open | 70 (37–99) | 1 (7) | 2 (13) | 80 | 80 | 13 (100) | 12 (92) | NR | 12 (100) | 12 (100) | 18 |

| Wishahi et al.45 | 13 | Open | 132 (60–180) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 100 | 100 | 9 (69) | NR | 4 (31) | 12 (92) | 11 (85) | 23.7 |

| Moursy et al.46 | 18 | Open | 70 (39–95) | 0 (0) | 3 (17) | 88 | 88 | 17 (100) | 2 (88) | 4 (24) | 18 (100) | 14 (82) | NR |

| Tuderti et al.47 | 11 | Robotic | 28 (IQR 14–51) | NR | NR | NR | NR | 91 | 86 | 3 (27) | 8 (73) | NR | 26.2 |

Patient Consent Statement

The author(s) have received and archived patient consent for video recording/publication in advance of video recording of procedure.

Recommended Videos from Videourology

1. Videourology 2016 Vol. 30, No. 4.

Robotic Radical Cystectomy and Extended Pelvic Lymph Node Dissection in a Female Patient.

Geoffrey S. Gaunay and Lee Richstone.

https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/vid.2015.0070.

2. Videourology 2017 Vol. 31, No. 3.

Sexual Sparing Robot-Assisted Radical Cystectomy in Female: Technique Step-by-Step.

Franco Gaboardi, Marco Grillo, Giuseppe Saitta, Giovanni Passaretti, Salvatore Smelzo, Nazareno Suardi, and Giovannalberto Pini.

https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/vid.2016.0067.

3. Videourology 2014 Vol. 28, No. 1.

Female Organ-Sparing Robotic Cystectomy: A Step-by-Step Anatomic Approach.

Alvin C. Goh, Andre Abreu, Miguel Mercado, Rene Sotelo, Golena Fernandez, Monish Aron, Inderbir Singh Gill, and Mihir Desai.

Supplementary Material

Abbreviations Used

- AUA

American Urological Association

- BCG

bacillus Calmette Guerin

- CIC

clean intermittent catheterization

- CT

computed tomography

- DSS

disease-specific survival

- DVC

dorsal venous complex

- DVT

deep venous thrombosis

- EEA

end anastomosis

- EF

endopelvic fascia and pubourethral ligament are intact

- FSFI

female sexual function index

- IP

infundibulopelvic

- IQR

interquartile range

- MIBC

muscle invasive bladder cancer

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- NAC

neoadjuvant chemotherapy

- NMIBC

non-muscle invasive bladder cancer

- NR

not reported

- ONB

orthotopic neobladder

- ORC

open radical cystectomy

- OS

overall survival

- POD

postoperative day

- POSRC

pelvic organ-sparing radical cystectomy

- QOL

quality of life

- RARC

robot-assisted radical cystectomy

- RCT

randomized controlled trial

- TAP

transversus abdominus plane

- TURBT

transurethral resection of bladder tumor

- US

urethral stump

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Funding Information

The Ruth L Kirschstein Research Service Award (T32CA082088).

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Chang SS, Bochner BH, Chou R, et al. Treatment of non-metastatic muscle-invasive bladder cancer: AUA/ASCO/ASTRO/SUO guideline. J Urol 2017;198:552–559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Witjes JA, Bruins HM, Cathomas R, et al. European Association of Urology guidelines on muscle-invasive and metastatic bladder cancer: Summary of the 2020 guidelines. Eur Urol 2021;79:82–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Flaig TW, Spiess PE, Agarwal N, et al. Bladder cancer, version 3.2020, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2020;18:329–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Neoadjuvant cisplatin, methotrexate, and vinblastine chemotherapy for muscle-invasive bladder cancer: A randomised controlled trial. International collaboration of trialists. Lancet 1999;354:533–540. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. International Collaboration of Trialists, Medical Research Council Advanced Bladder Cancer Working Party (now the National Cancer Research Institute Bladder Cancer Clinical Studies Group), European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Genito-Urinary Tract Cancer Group, et al. International phase III trial assessing neoadjuvant cisplatin, methotrexate, and vinblastine chemotherapy for muscle-invasive bladder cancer: Long-term results of the BA06 30894 trial. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:2171–2177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Grossman HB, Natale RB, Tangen CM, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy plus cystectomy compared with cystectomy alone for locally advanced bladder cancer. N Engl J Med 2003;349:859–866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kamat AM, Gee JR, Dinney CPN, et al. The case for early cystectomy in the treatment of nonmuscle invasive micropapillary bladder carcinoma. J Urol 2006;175(3 Pt 1):881–885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sylvester RJ, van der Meijden APM, Oosterlinck W, et al. Predicting recurrence and progression in individual patients with stage Ta T1 bladder cancer using EORTC risk tables: A combined analysis of 2596 patients from seven EORTC trials. Eur Urol 2006;49:466–5; discussion 475–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fernandez-Gomez J, Madero R, Solsona E, et al. Predicting nonmuscle invasive bladder cancer recurrence and progression in patients treated with bacillus Calmette–Guerin: The CUETO scoring model. J Urol 2009;182:2195–2203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Martin-Doyle W, Leow JJ, Orsola A, Chang SL, Bellmunt J. Improving selection criteria for early cystectomy in high-grade t1 bladder cancer: A meta-analysis of 15,215 patients. J Clin Oncol 2015;33):643–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chang SS, Boorjian SA, Chou R, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of non-muscle invasive bladder cancer: AUA/SUO guideline. J Urol 2016;196:1021–1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Babjuk M, Burger M, Compérat EM, et al. European Association of Urology guidelines on non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer (TaT1 and carcinoma in situ)—2019 update. Eur Urol 2019;76:639–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Herr HW, Bochner BH, Dalbagni G, Donat SM, Reuter VE, Bajorin DF. Impact of the number of lymph nodes retrieved on outcome in patients with muscle invasive bladder cancer. J Urol 2002;167:1295–1298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Abdollah F, Sun M, Schmitges J, et al. Stage-specific impact of pelvic lymph node dissection on survival in patients with non-metastatic bladder cancer treated with radical cystectomy. BJU Int 2012;109:1147–1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Venkatramani V, Reis IM, Castle EP, et al. Predictors of recurrence, and progression-free and overall survival following open versus robotic radical cystectomy: Analysis from the RAZOR trial with a 3-year followup. J Urol 2020;203:522–529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Parekh DJ, Reis IM, Castle EP, et al. Robot-assisted radical cystectomy versus open radical cystectomy in patients with bladder cancer (RAZOR): An open-label, randomised, phase 3, non-inferiority trial. Lancet 2018;391:2525–2536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rai BP, Bondad J, Vasdev N, et al. Robotic versus open radical cystectomy for bladder cancer in adults. Cochrane Urology Group, ed. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2019;4:CD011903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wilson TG, Guru K, Rosen RC, et al. Best practices in robot-assisted radical cystectomy and urinary reconstruction: Recommendations of the Pasadena Consensus Panel. Eur Urol 2015;67:363–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chen ME, Pisters LL, Malpica A, Pettaway CA, Dinney CP. Risk of urethral, vaginal and cervical involvement in patients undergoing radical cystectomy for bladder cancer: Results of a contemporary cystectomy series from M. D. Anderson Cancer Center. J Urol 1997;157:2120–2123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chang SS, Cole E, Smith JA, Cookson MS. Pathological findings of gynecologic organs obtained at female radical cystectomy. J Urol 2002;168:147–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ali-El-Dein B, Abdel-Latif M, Mosbah A, et al. Secondary malignant involvement of gynecologic organs in radical cystectomy specimens in women: Is it mandatory to remove these organs routinely? J Urol 2004;172:885–887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Djaladat H, Bruins HM, Miranda G, Cai J, Skinner EC, Daneshmand S. Reproductive organ involvement in female patients undergoing radical cystectomy for urothelial bladder cancer. J Urol 2012;188:2134–2138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Daly MB, Pilarski R, Berry M, et al. NCCN guidelines insights: Genetic/familial high-risk assessment: Breast and ovarian, version 2.2017. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2017;15:9–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gupta S, Provenzale D, Llor X, et al. NCCN guidelines insights: Genetic/familial high-risk assessment: Colorectal, version 2.2019. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2019;17:1032–1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lee CT, Chang SS, Kamat AM, et al. Alvimopan accelerates gastrointestinal recovery after radical cystectomy: A multicenter randomized placebo-controlled trial. Eur Urol 2014;66:265–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lightner DJ, Wymer K, Sanchez J, Kavoussi L. Best practice statement on urologic procedures and antimicrobial prophylaxis. J Urol 2020;203:351–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Forrest JB, Clemens JQ, Finamore P, et al. AUA Best Practice Statement for the prevention of deep vein thrombosis in patients undergoing urologic surgery. J Urol 2009;181:1170–1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chang SS, Cole E, Cookson MS, Peterson M, Smith JA. Preservation of the anterior vaginal wall during female radical cystectomy with orthotopic urinary diversion: Technique and results. J Urol 2002;168(4 Pt 1):1442–1445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Koie T, Hatakeyama S, Yoneyama T, Hashimoto Y, Kamimura N, Ohyama C. Uterus-, fallopian tube-, ovary-, and vagina-sparing cystectomy followed by U-shaped ileal neobladder construction for female bladder cancer patients: Oncological and functional outcomes. Urology 2010;75:1499–1503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ali-El-Dein B, Mosbah A, Osman Y, et al. Preservation of the internal genital organs during radical cystectomy in selected women with bladder cancer: A report on 15 cases with long term follow-up. Eur J Surg Oncol 2013;39:358–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Goh AC, Aghazadeh MA, Krasnow RE, Pastuszak AW, Stewart JN, Miles BJ. Robotic intracorporeal continent cutaneous urinary diversion: Primary description. J Endourol 2015;29:1217–1220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Dason S, Goh AC. Contemporary techniques and outcomes of robotic cystectomy and intracorporeal urinary diversions. Curr Opin Urol 2018;28:115–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Matulewicz RS, Chesnut GT, Huang CC, Bochner BH, Goh AC. Evolution in technique of robotic intracorporeal continent catheterizable pouch after cystectomy. Urol Video J 2019;4:100020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ali-El-Dein B, el-Sobky E, Hohenfellner M, Ghoneim MA. Orthotopic bladder substitution in women: Functional evaluation. J Urol 1999;161:1875–1880. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Granberg CF, Boorjian SA, Crispen PL, et al. Functional and oncological outcomes after orthotopic neobladder reconstruction in women. BJU Int 2008;102:1551–1555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lee CT, Hafez KS, Sheffield JH, Joshi DP, Montie JE. Orthotopic bladder substitution in women: Nontraditional applications. J Urol 2004;171:1585–1588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Butt ZM, Perlmutter AE, Piacente PM, et al. Impact of body mass index on robot-assisted radical cystectomy. JSLS 2008;12:241–245. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ahmadi N, Clifford TG, Miranda G, et al. Impact of body mass index on robot-assisted radical cystectomy with intracorporeal urinary diversion. BJU Int 2017;120:689–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bochner BH, Figueroa AJ, Skinner EC, et al. Salvage radical cystoprostatectomy and orthotopic urinary diversion following radiation failure. J Urol 1998;160:29–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Zlatev DV, Skinner EC. Orthotopic urinary diversion for women. Urol Clin North Am 2018;45:49–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bochner BH, Dalbagni G, Marzouk KH, et al. Randomized trial comparing open radical cystectomy and robot-assisted laparoscopic radical cystectomy: Oncologic outcomes. Eur Urol 2018;74:465–471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Smith AB, Crowell K, Woods ME, et al. Functional outcomes following radical cystectomy in women with bladder cancer: A systematic review. Eur Urol Focus 2017;3:136–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Rosen R, Brown C, Heiman J, et al. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): A multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. J Sex Marital Ther 2000;26:191–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Meston CM. Validation of the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) in women with female orgasmic disorder and in women with hypoactive sexual desire disorder. J Sex Marital Ther 2003;29:39–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wishahi M, Elganozoury H. Survival up to 5–15 years in young women following genital sparing radical cystectomy and neobladder: Oncological outcome and quality of life. Single-surgeon and single-institution experience. Cent Eur J Urol 2015;68:141–145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Moursy EES, Eldahshoursy MZ, Gamal WM, Badawy AA. Orthotopic genital sparing radical cystectomy in pre-menopausal women with muscle-invasive bladder carcinoma: A prospective study. Indian J Urol 2016;32:65–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Tuderti G, Mastroianni R, Flammia S, et al. Sex-sparing robot-assisted radical cystectomy with intracorporeal padua ileal neobladder in female: Surgical technique, perioperative, oncologic and functional outcomes. J Clin Med 2020;9:577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.