Abstract

Objective:

To better address sociodemographic-related health disparities, this study examined which sociodemographic variables most strongly correlate with self-reported health in patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain.

Design:

This single-center, cross-sectional study examined adult patients followed by a physiatrist for chronic (≥4 years) musculoskeletal pain. Sociodemographic variables considered were race, sex, and disparate social disadvantage (measured as residential address in the worst versus best Area Deprivation Index national quartile). The primary comparison was the adjusted effect size of each variable on physical and behavioral health (measured by Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS)).

Results:

In 1,193 patients (age 56.3±13.0 years), disparate social disadvantage was associated with worse health in all domains assessed (PROMIS Physical Function B −2.4 points [95%CI −3.8–−1.0], Pain Interference 3.3 [2.0–4.6], Anxiety 4.0 [1.8–6.2], and Depression 3.7 [1.7–5.6]). Black race was associated with greater anxiety than white race (3.2 [1.1–5.3]), and female sex was associated with worse physical function than male sex (−2.5 [−3.5–−1.5]).

Conclusion:

Compared to race and sex, social disadvantage is more consistently associated with worse physical and behavioral health in patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain. Investment to ameliorate disadvantage in geographically defined communities may improve health in sociodemographically at-risk populations.

Keywords: Socioeconomic factors, Health status disparities, Chronic pain, Musculoskeletal diseases

INTRODUCTION

Health outcomes are strongly influenced by sociodemographic factors.1 Patient characteristics such as Black race, female sex, and social disadvantage correlate with worse symptom reporting, access to care, and re-hospitalization rates in patients with a variety of medical conditions including cardiopulmonary disease, mental health disorders, and acute and chronic pain.2–4 Disparate morbidity and mortality rates from the COVID-19 pandemic have especially highlighted these issues.5 Multiple underlying phenomena likely contribute to sociodemographic-driven disparities. Systemic racism, sexism, and epigenetics can all influence physical and behavioral health, independent of income level.6–8 Furthermore, intersectional effects of sociodemographic variables such as Black race and female sex can also exacerbate disparities.9,10

In order to design and appropriately prioritize effective interventions to address these disparities, Penman-Aguilar et al. and Alegria et al. advocate for assessment of the relative effects of sociodemographic variables.9 ,11 Relationships between sociodemographic variables and chronic pain are particularly important to explore because 20% of Americans live with chronic pain that interferes with employment, family responsibilities, and wellness,12 and disabling chronic pain disproportionately affects socially at-risk populations.13 ,14 As the standard of care for pain management evolves in response to the opioid crisis, new treatment guidelines should consider ways to also mitigate the disproportionate burden of chronic pain in these select sociodemographic groups.

The purpose of this study was to examine associations between sociodemographic variables (i.e., race, sex, and social disadvantage) and self-reported physical and behavioral health in patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain. The hypothesis was that, consistent with findings in other patient populations, Black race, female sex, and social disadvantage would each independently correlate with worse self-reported physical and behavioral health.

METHODS

This cross-sectional study analyzed electronic medical records from a single tertiary care academic institution in St. Louis, MO, USA. The institution acts as a safety net medical center for the surrounding urban and multi-state rural region. Study procedures were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of the World Medical Association. University Institutional Review Board approval was granted prior to data collection with a waiver of informed consent. Data analysis was performed in 2019 and 2020. Reporting for this study conforms to all STROBE guidelines (see Supplementary Checklist).

Study population

The study population consisted of adult patients (18 years and older) who presented to a board-certified sports medicine physical medicine and rehabilitation physician (physiatrist) for non-operative management of one or more chronic painful musculoskeletal disorders. The study physiatrists exclusively manage musculoskeletal conditions, so for this study, a chronic musculoskeletal disorder was defined as presentation multiple times to one of the eight sports medicine physiatrists at the study institution for musculoskeletal pain in one or more body regions. The clinical presentations had to occur at least once between January 1, 2000 – December 31, 2011 and once between June 22, 2015 – November 1, 2017, which means all patients had pain for a minimum of four years at the time of data analysis. The first time interval was chosen because it represents the period when the physicians accepted the transfer of care for chronic pain management (including opioid management) for any patient. The second interval was chosen because it captured the time when collection of Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS®) measures became standard of care for all patients presenting to the physicians. After an eligible initial presentation, eligible follow-up presentations included visits for routine monitoring / medication refills and for pain flares. All consecutive eligible patients were included. Pediatric patients and those with pain that resolved to the point of not requiring follow-up were excluded from the study.

Measures

Sociodemographic variables of interest were patients’ self-reported race, biological sex, and degree of social disadvantage, as measured by the 2018 Area Deprivation Index (ADI).4 The ADI was developed by Singh, Kind, and colleagues to rank communities using a composite score derived from 17 variables that quantify various domains such as residents’ income, education, employment, and housing quality. Each 9-digit zip code is assigned an ADI national percentile from 1 to 100, with a larger percentile representing worse social disadvantage. ADI values are systematically missing for zip codes that do not match an ADI (e.g., if offshore) and that represent a post office (PO) box or a business entity responsible for large volume mail delivery. In accordance with published literature and in order to facilitate intuitive, clinically relevant data interpretation, socially disadvantaged communities were defined as those with zip codes in the worst ADI national quartile, and disparate social disadvantage was defined as comparison between communities with zip codes in the most versus least disadvantaged ADI national quartiles.15

Patients’ age, use of chronic opioid therapy for pain management, and health insurance status were also recorded because they are known to be associated with patients’ self-reported health.16 For this study, chronic opioid therapy was defined as maintaining adherence to an opioid contract and receiving repeated opioid prescriptions of a relatively consistent dose and quantity from the study physicians at regular time intervals, which necessitated that patients present for in-person follow-up appointments at least every three months, report they are taking the medication as prescribed, pass random urine drug screens at least annually, and maintain a stable functional level without an escalating opioid dose.

The primary comparison measure was the adjusted effect size of each sociodemographic variable (race, sex, and social disadvantage) on patients’ self-reported physical and behavioral health, as measured by PROMIS®.17 Patients completed the PROMIS Computer Adaptive Test (CAT) measures prior to the physician encounter as standard of care during their clinic visits. Physical health was quantified using PROMIS Physical Function v1.2 (later switched to v2.0) and Pain Interference v1.1, and behavioral health was quantified with the PROMIS Anxiety v1.0 and Depression v1.0 domains. Because PROMIS Physical Function versions 1.2 and 2.0 yield comparable scores, the versions were combined during statistical analysis.18 Of note, the PROMIS Anxiety domain was not collected as standard of care until ten months after implementation of the other domains, which resulted in missing data without systematic bias. Scores for all PROMIS domains are normalized with a mean of 50 and standard deviation of 10, and higher scores represent more of the domain. For instance, compared to the reference population, a score of 60 on PROMIS Depression represents more (worse) depression symptoms than average, but a score of 60 on PROMIS Physical Function represents more (better) physical function than average. The general reference population used to standardize PROMIS scores mirrored the race, sex, age, and education distribution reported from the 2000 United States General Census.19

Minimum meaningful effect sizes on PROMIS scores were estimated based on published within-group minimal clinically important differences (MCIDs) in patients with conservatively managed musculoskeletal pain.20–22 Additionally, any effect size smaller than the standard error of measurement for each PROMIS CAT domain at the study institution was considered to not be clinically meaningful. Therefore, meaningful differences were defined as 2.2 points for Physical Function, 2.0 for Pain Interference, 3.0 for Anxiety, and 3.2 for Depression.

Because race and biological sex are typically fixed variables throughout a person’s lifetime whereas the level of social disadvantage related to a person’s local community can change, a sub-analysis was performed to compare the proportion of patients in each ADI quartile who identified as each race and sex.

Statistical analysis

Each PROMIS measure was modeled using multiple linear regression. Independent variables included in each model were patients’ self-reported race (categorized as white, Black, or other), self-reported biological sex (male or female), and disparate social disadvantage (i.e., comparison between the most and least disadvantaged ADI national quartiles).15 Covariates included age (categorized by decade) and current chronic opioid use status (yes or no). The covariates were chosen a priori because of their established effects on physical and behavioral health. Health insurance status was not included as a covariate because it captures essentially the same construct as ADI (e.g., socioeconomic status), and it does not stratify patients as effectively as ADI. Model fits were assessed by inspection of residuals, histograms, and 1:1 plots of observed versus modeled dependent variables. Some outliers were observed for each of the four PROMIS measures, as determined by Cook’s D and DFFITS, so robust variants of each regression were run with a Huber loss function. The pattern of significance did not change, so the traditional regression model results are reported. For the sub-analysis, Pearson’s chi-square tests were performed to compare the race and sex demographic breakdown between each ADI national quartile. Missing data were omitted from all analyses, and p<.05 was set as the level of significance a priori. All data analyses were performed using SAS Base v9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC) and R (4.0.2, Vienne, Austria).

RESULTS

In total, 1,193 patients (mean age 56.3 ± 13.0 years) met the study criteria (Figure 1). The majority of patients self-reported white race (981, 82.2%) and female sex (843, 70.7%), and patients were nearly evenly distributed across all four ADI national quartiles of social disadvantage (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Flowsheet of included patients presenting for evaluation of chronic musculoskeletal pain between 2015 and 2017

Table 1.

Sociodemographics and self-reported health of 1,193 patients evaluated for chronic musculoskeletal pain between 2015–2017.

| Mean (SD) or n (%) |

Missing (n) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (Years) | 56.3 (13.0) | 0 |

| Female Sex | 843 (70.7%) | 0 |

| Race | 0 | |

| White | 981 (82.2%) | |

| Black | 186 (15.6%) | |

| Other | 26 (2.2%) | |

| ADI quartile | 80 | |

| 1 (Least disadvantaged) | 250 (22.5%) | |

| 2 | 271 (24.3%) | |

| 3 | 280 (25.2%) | |

| 4 (Most disadvantaged) | 312 (28.0%) | |

| Insurance | 171 | |

| Private | 511 (51.0%) | |

| Medicare | 464 (46.3%) | |

| Medicaid | 26 (2.6%) | |

| Other | 1 (0.0%) | |

| Chronic Opioid Use | 352 (31.6%) | 80 |

| PROMIS Score | ||

| Physical Function | 37.2 (7.6) | 36 |

| Pain Interference | 63.7 (7.1) | 40 |

| Anxiety | 55.1 (10.5) | 256 |

| Depression | 50.4 (10.4) | 53 |

| Meets Clinically Significant Threshold a | ||

| Anxiety | 237 (25.3%) | 256 |

| Depression | 200 (17.5%) | 53 |

Predetermined thresholds for clinically significant behavioral health disorders are defined as PROMIS Depression ≥ 59.9 and PROMIS Anxiety ≥ 62.3 based on established linkage tables developed by Schalet et al.23 ,24

Abbreviations: ADI (Area Deprivation Index), PROMIS (Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System).

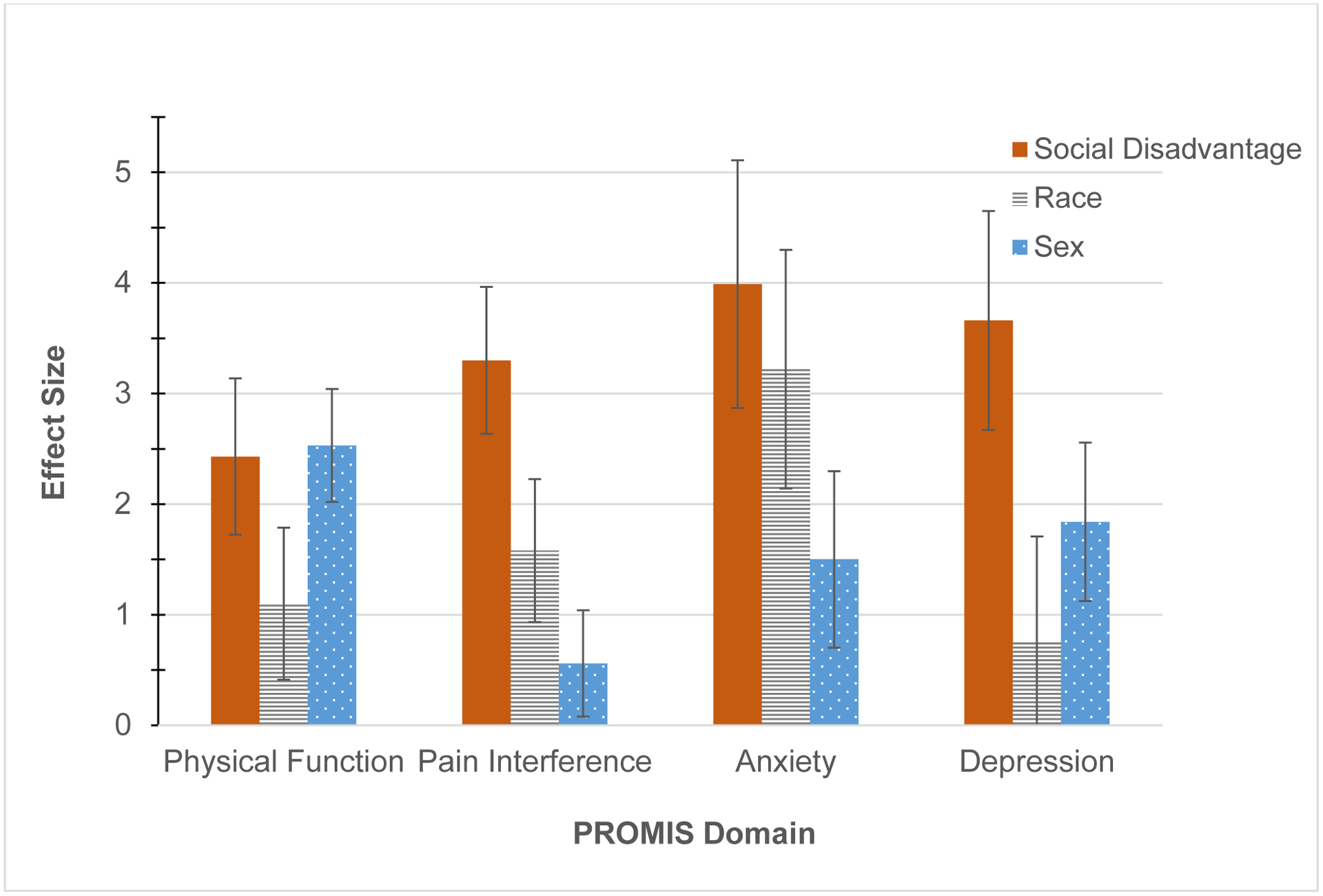

Disparate social disadvantage was independently associated with clinically meaningfully worse self-reported physical and behavioral health in all domains assessed (PROMIS Physical Function B −2.4 points [95% CI −3.8 to −1.0], Pain Interference 3.3 [2.0 to 4.6], Anxiety 4.0 [1.8 to 6.2], and Depression 3.7 points [1.7 to 5.6]) (Table 2, Figure 2). Even when compared to the intermediate national ADI quartiles (Q2 and Q3), pain interference was meaningfully worse in communities scoring in the worst ADI quartile.

Table 2.

Associations between sociodemographic variables and self-reported health in 1,193 patients evaluated for chronic musculoskeletal pain.

| PROMIS domain | n | R2 | Social Variable | B (SE) | 95% CI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Function | 993 | 0.108 | |||||

| Race = Black | −1.1 (0.7) | −2.5 | to 0.2 | .11 | |||

| Sex = Female | −2.5 (0.5) | −3.5 | to −1.5 | < .001 | |||

| ADI = Q2 | −1.0 (0.7) | −2.4 | to 0.3 | .13 | |||

| ADI = Q3 | −1.0 (0.7) | −2.4 | to 0.3 | .13 | |||

| ADI = Q4 | −2.4 (0.7) | −3.8 | to −1.0 | < .001 | |||

| Pain Interference | 988 | 0.088 | |||||

| Race = Black | 1.6 (0.7) | 0.3 | to 2.8 | .015 | |||

| Sex = Female | 0.6 (0.5) | −0.4 | to 1.5 | .25 | |||

| ADI = Q2 | 2.1 (0.6) | 0.9 | to 3.3 | .001 | |||

| ADI = Q3 | 2.2 (0.6) | 0.9 | to 3.4 | < .001 | |||

| ADI = Q4 | 3.3 (0.7) | 2.0 | to 4.6 | < .001 | |||

| Anxiety | 808 | 0.066 | |||||

| Race = Black | 3.2 (1.1) | 1.1 | to 5.3 | .003 | |||

| Sex = Female | 1.5 (0.8) | −0.1 | to 3.1 | .06 | |||

| ADI = Q2 | 1.3 (1.1) | −0.8 | to 3.4 | .22 | |||

| ADI = Q3 | 1.9 (1.1) | −0.2 | to 3.9 | .08 | |||

| ADI = Q4 | 4.0 (1.1) | 1.8 | to 6.2 | < .001 | |||

| Depression | 977 | 0.059 | |||||

| Race = Black | 0.8 (1.0) | −1.1 | to 2.6 | .44 | |||

| Sex = Female | 1.8 (0.7) | 0.43 | to 3.2 | .01 | |||

| ADI = Q2 | 0.8 (1.0) | −1.0 | to 2.7 | .39 | |||

| ADI = Q3 | 1.4 (0.9) | −0.5 | to 3.2 | .14 | |||

| ADI = Q4 | 3.7 (1.0) | 1.7 | to 5.6 | < .001 | |||

A multiple linear regression model is presented for each PROMIS domain. Reference values for the sociodemographic variables of interest include: Race=White, Sex=Male, ADI=Q1 (quartile with the least social disadvantage). Age and chronic opioid use are also covariates in the models. The p-value for all four models was <.001. Boldface indicates statistical significance for the respective independent variable (p<.05).

Abbreviations: PROMIS (Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System), ADI (Area Deprivation Index).

Figure 2.

Relative associations between sociodemographics and health

The y-axis represents the absolute value of each regression coefficient when also controlling for age and chronic opioid status. “Social Disadvantage” depicts the comparison of outcome measures between communities with disparate social disadvantage, which is defined as communities in the most versus least disadvantaged national quartiles of the Area Deprivation Index (Q4 versus Q1). “Race” depicts the comparison of Black versus white. “Sex” depicts the comparison of female versus male. Error bars represent the standard error.

Black race was independently and meaningfully associated with greater anxiety than white race (3.2 points [1.1 to 5.3]), and female sex was associated with worse physical function than male sex (−2.5 points [−3.5 to −1.5]). Furthermore, sub-analysis revealed that, compared to less disadvantaged communities, a relatively greater proportion of Black and female patients lived in the most disadvantaged communities (Worst ADI national quartile: 122/312 (39.1%) Black vs Best quartile: 10/250 (4.0%) Black, p<.001; Worst quartile: 239/312 (76.6%) female vs Best quartile: 164/250 (65.6%) female, p=.036) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Relationships between fixed demographic variables and living in a socially disadvantaged community.

| ADI Quartile | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic n (%) |

Q1 (n=250) |

Q2 (n=271) |

Q3 (n=280) |

Q4 (n=312) |

p-value |

| Black Race | 10 (4.0%) | 14 (5.2%) | 32 (11.4%) | 122 (39.1%) | <.001 |

| Female Sex | 164 (65.6%) | 189 (69.7%) | 197 (70.4%) | 239 (76.6%) | .036 |

Q1 represents the least disadvantaged national quartile, and Q4 represents the most disadvantaged national quartile. Boldface indicates statistical significance when comparing all four quartiles (p<.05).

Abbreviation: ADI (Area Deprivation Index).

DISCUSSION

This study examined associations between sociodemographic variables and self-reported health in patients who presented to a physiatric practice for chronic musculoskeletal pain. Disparate social disadvantage was the single variable consistently associated with meaningfully worse physical and behavioral health in all domains assessed. Contrary to the study hypothesis, Black race was only independently associated with worse anxiety symptoms, and female sex was only independently associated with worse physical function. However, Black race and female sex were disproportionately represented in the most disadvantaged communities.

The study findings are consistent with established literature, but they also address gaps identified by Penman-Aguilar et al. and Alegria et al. regarding identification of which sociodemographic variables most strongly influence health and outcomes and should therefore be prioritized when designing interventions.9 ,11 ,14 The findings build on previous work by Wright et al., which also demonstrated that social environment is associated with both physical and behavioral health in patients presenting for orthopedic conditions.15 In contrast to Wright’s analysis, this study specifically focused on patients with chronic pain who were managed by non-operative specialists. These patients are less likely than the general orthopedic population to have spontaneous pain resolution or to be candidates for a surgical intervention, so it is possible the psychological and long-term social burden of these patients’ musculoskeletal conditions may be greater. Furthermore, this study incorporated race into the discussion of important sociodemographic variables, whereas race was not a focus in Wright’s study. Because the study institution is located in a region with an especially deep-rooted history and persistence of racial segregation and race-related health disparities,25 associations between race and self-reported health were particularly important to examine. Black patients are less likely to be prescribed controlled substances, be screened for depression, or receive behavioral health care.26

The study findings can be interpreted as encouraging because, unlike a person’s race or sex, social disadvantage can be systematically modified on a large scale. Targeted intervention to address upstream social factors such as education, housing, employment, income support, nutrition support, care coordination, and provider biases are effective means to improving overall health, facilitating treatment adherence, and reducing healthcare expenditures.27 ,28 That is, genetic and epigenetic variables may indeed play some role in health disparities,8 but based on the study findings, strategic efforts to create opportunities and improve geographic neighborhoods may be the most important type of intervention to achieve health equity in the chronic pain population. Even the higher anxiety levels in Black patients may be addressed by tackling societal issues such as housing discrimination and exposure to disproportionate police violence.29

The study results also highlight the importance of interpreting PROMIS scores within the context of the geographic or patient population of interest. That is, during development, the PROMIS domain scores were standardized using a population with a demographic distribution that mirrored the 2000 United States General Census, which was 12.3% Black, 75.1% white, and included people with a wide variety of educational levels. In contrast, the metro region around the study institution clinic sites is 29.9% Black,30 and the distribution of this study population was 15.6% Black. Therefore, average PROMIS Anxiety scores in the community surrounding the study institution may be worse than a T-score of 50. Until health equity is achieved across the entire sociodemographic spectrum, healthcare providers striving to practice personalized medicine should consider interpreting a patient’s PROMIS scores within the context of his/her sociodemographics, rather than simply comparing patients’ T-scores to the general U.S. population. That is, the “average” person represented in the U.S. Census likely is not very representative of patients in sociodemographic minorities. It is important to keep in mind that social variables may be influencing patients’ self-reported health as much, if not more than, the condition for which they present for medical attention.

Limitations

There are several study limitations. First, the demographic distribution required that race categories were condensed to White, Black, and Other, and biological sex was recorded as a binary variable and could not take into account gender identity. Second, the patient population was derived from a single department of a single institution. Nevertheless, the sample size was large, and the study institution draws from a diverse, multi-state urban and rural catchment area. These factors should be considered when interpreting the generalizability of the study. Third, the variables examined in this study only accounted for a modest proportion of the variance observed for each health measure (R2 = 0.06–0.11). This was to be expected since the purpose of the study was to evaluate relative associations between sociodemographic variables and health, rather than to create a prediction model or to capture all potential variables which could be influencing health (such as more detailed features of patients’ musculoskeletal conditions). Finally, this cross-sectional study cannot establish causality between sociodemographic variables and self-reported health.

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, in patients presenting with chronic musculoskeletal pain, social disadvantage was associated with worse physical function, pain interference, anxiety, and depression symptoms, whereas Black race was only associated with more anxiety symptoms, and female sex was only associated with worse physical function. However, patients of Black race and female sex were more likely to live in socially disadvantaged neighborhoods. If these findings are confirmed with prospective investigation, the results support that strategic investment to ameliorate disadvantage in geographically defined communities may be an effective strategy to improving health in these at-risk populations.

Supplementary Material

What is Known:

Sociodemographic characteristics such as Black race, female sex, and high social disadvantage correlate with disparities in care and worse outcomes across numerous health domains.

What is New:

Compared to race and sex, in patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain, social disadvantage is more consistently associated with worse self-reported physical and behavioral health. However, patients of Black race and female sex are more likely to live in socially disadvantaged neighborhoods. The results support that strategic investment into geographically defined, disadvantaged communities may be an efficient strategy to improve health in patients with multiple sociodemographic risk factors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This authors thank Lee Rhea, PhD, and Matthew Schuelke, PhD (Washington University), for their assistance with statistical analysis for this study.

Funding for the project:

This study was supported by the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation and by grant K23AR074520 from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (Dr. Cheng). Neither funding body had any role in the study design; collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data; writing of the report; or decision to submit the report for publication.

Footnotes

Competing interests:

None of the authors have conflicts of interest or competing interests to disclose.

Financial benefit to the authors:

None of the authors expect financial benefit from this study or manuscript.

Previous presentations:

Data reported in this manuscript have been partially presented in abstract/poster format at the 2021 Association of Academic Physiatrists (AAP) Annual Meeting. The dataset used in this study has also been used for another manuscript that is currently under review at another journal. The data analyses in the two manuscripts do not overlap.

REFERENCES

- 1.Meyer PA, Penman-Aguilar A, Campbell VA, Graffunder C, O’Connor AE, Yoon PW. Conclusion and future directions: CDC Health Disparities and Inequalities Report - United States, 2013. MMWR Suppl 2013;62(3):184–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mossey JM. Defining racial and ethnic disparities in pain management. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res 2011;469(7):1859–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asada Y, Whipp A, Kindig D, Billard B, Rudolph B. Inequalities in multiple health outcomes by education, sex, and race in 93 US counties: why we should measure them all. Int J Equity Health 2014;13:47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kind AJH, Jencks S, Brock J, et al. Neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage and 30-day rehospitalization: a retrospective cohort study. Ann. Intern. Med 2014;161(11):765–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dorn AV, Cooney RE, Sabin ML. COVID-19 exacerbating inequalities in the US. Lancet 2020;395(10232):1243–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paradies Y, Ben J, Denson N, et al. Racism as a Determinant of Health: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS One 2015;10(9):e0138511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Molix L Sex differences in cardiovascular health: does sexism influence women’s health? Am. J. Med. Sci 2014;348(2):153–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Horvath S, Gurven M, Levine ME, et al. An epigenetic clock analysis of race/ethnicity, sex, and coronary heart disease. Genome Biol. 2016;17(1):171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Penman-Aguilar A, Talih M, Huang D, Moonesinghe R, Bouye K, Beckles G. Measurement of Health Disparities, Health Inequities, and Social Determinants of Health to Support the Advancement of Health Equity. J. Public Health Manag. Pract 2016;22 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):S33–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bey GS, Jesdale B, Forrester S, Person SD, Kiefe C. Intersectional effects of racial and gender discrimination on cardiovascular health vary among black and white women and men in the CARDIA study. SSM Popul Health 2019;8:100446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alegría M, NeMoyer A, Falgàs Bagué I, Wang Y, Alvarez K. Social Determinants of Mental Health: Where We Are and Where We Need to Go. Current psychiatry reports 2018;20(11):95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dahlhamer J, Lucas J, Zelaya C, et al. Prevalence of Chronic Pain and High-Impact Chronic Pain Among Adults - United States, 2016. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report 2018;67(36):1001–06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Janevic MR, McLaughlin SJ, Heapy AA, Thacker C, Piette JD. Racial and Socioeconomic Disparities in Disabling Chronic Pain: Findings From the Health and Retirement Study. J. Pain 2017;18(12):1459–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Green CR, Hart-Johnson T. The association between race and neighborhood socioeconomic status in younger Black and White adults with chronic pain. J. Pain 2012;13(2):176–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wright MA, Adelani M, Dy C, OʼKeefe R, Calfee RP. What is the Impact of Social Deprivation on Physical and Mental Health in Orthopaedic Patients? Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res 2019;477(8):1825–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goesling J, Lin LA, Clauw DJ. Psychiatry and Pain Management: at the Intersection of Chronic Pain and Mental Health. Current psychiatry reports 2018;20(2):12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cella D, Yount S, Rothrock N, et al. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS): progress of an NIH Roadmap cooperative group during its first two years. Med. Care 2007;45(5 Suppl 1):S3–S11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.PROMIS Score Cut Points. Secondary PROMIS Score Cut Points 2019. http://www.healthmeasures.net/score-and-interpret/interpret-scores/promis/promis-score-cut-points.

- 19.Liu H, Cella D, Gershon R, et al. Representativeness of the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System Internet panel. J. Clin. Epidemiol 2010;63(11):1169–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee AC, Driban JB, Price LL, Harvey WF, Rodday AM, Wang C. Responsiveness and Minimally Important Differences for 4 Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System Short Forms: Physical Function, Pain Interference, Depression, and Anxiety in Knee Osteoarthritis. J. Pain 2017;18(9):1096–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kroenke K, Yu Z, Wu J, Kean J, Monahan PO. Operating characteristics of PROMIS four-item depression and anxiety scales in primary care patients with chronic pain. Pain Med. 2014;15(11):1892–901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen CX, Kroenke K, Stump TE, et al. Estimating minimally important differences for the PROMIS pain interference scales: results from 3 randomized clinical trials. Pain 2018;159(4):775–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schalet BD, Cook KF, Choi SW, Cella D. Establishing a common metric for self-reported anxiety: linking the MASQ, PANAS, and GAD-7 to PROMIS Anxiety. J. Anxiety Disord 2014;28(1):88–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Choi SW, Schalet B, Cook KF, Cella D. Establishing a common metric for depressive symptoms: linking the BDI-II, CES-D, and PHQ-9 to PROMIS depression. Psychol. Assess 2014;26(2):513–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oliveri R. Setting the stage for Ferguson: Housing discrimination and segregation in St. Louis. Mo L Rev. 2015;80:1053. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hahm HC, Cook BL, Ault-Brutus A, Alegría M. Intersection of race-ethnicity and gender in depression care: screening, access, and minimally adequate treatment. Psychiatr. Serv 2015;66(3):258–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Taylor LA, Tan AX, Coyle CE, et al. Leveraging the Social Determinants of Health: What Works? PLoS One 2016;11(8):e0160217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Anastas TM, Miller MM, Hollingshead NA, Stewart JC, Rand KL, Hirsh AT. The Unique and Interactive Effects of Patient Race, Patient Socioeconomic Status, and Provider Attitudes on Chronic Pain Care Decisions. Ann. Behav. Med 2020;54(10):771–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bor J, Venkataramani AS, Williams DR, Tsai AC. Police killings and their spillover effects on the mental health of black Americans: a population-based, quasi-experimental study. Lancet 2018;392(10144):302–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bureau USC. QuickFacts. Secondary QuickFacts. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/stlouiscitymissouricounty. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.