Abstract

SARS-CoV-2 main protease (Mpro) is one of the most extensively exploited drug targets for COVID-19. Structurally disparate compounds have been reported as Mpro inhibitors, raising the question of their target specificity. To elucidate the target specificity and the cellular target engagement of the claimed Mpro inhibitors, we systematically characterize their mechanism of action using the cell-free FRET assay, the thermal shift-binding assay, the cell lysate Protease-Glo luciferase assay, and the cell-based FlipGFP assay. Collectively, our results have shown that majority of the Mpro inhibitors identified from drug repurposing including ebselen, carmofur, disulfiram, and shikonin are promiscuous cysteine inhibitors that are not specific to Mpro, while chloroquine, oxytetracycline, montelukast, candesartan, and dipyridamole do not inhibit Mpro in any of the assays tested. Overall, our study highlights the need of stringent hit validation at the early stage of drug discovery.

KEY WORDS: SARS-CoV-2, Antiviral, Main protease, Ebselen, Carmofur, FlipGFP assay, Protease-Glo luciferase assay

Abbreviations: Mpro, Main protease; PLpro, Papain-like protease; FFluc, Firefly luciferase; Rluc, Renilla luciferase

Graphical abstract

FlipGFP and protease-Glo luciferase assays, coupled with the FRET and thermal shift binding assays, were applied to validate/invalidate the reported SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitors.

1. Introduction

SARS-CoV-2 is the causative agent for COVID-19, which infected 229 million people and led to 4.71 million deaths as of September 23, 2021. SARS-CoV-2 is the third coronavirus that causes epidemics and pandemics in human. SARS-CoV-2, along with SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV, belong to the β genera of the coronaviridae family1. SARS-CoV-2 encodes two viral cysteine proteases, the main protease (Mpro) and the papain-like protease (PLpro), that mediate the cleavage of viral polyproteins pp1a and pp1ab during viral replication2, 3, 4. Mpro cleaves at more than 11 sites at the viral polyproteins and has a high substrate preference for glutamine at the P1 site5. In addition, the Mpro is highly conserved among coronaviruses that infect human including SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV, HCoV-OC43, HCoV-NL63, HCoV-229E, and HCoV-HKU1. For these reasons, Mpro becomes a high-profile drug target for the development of broad-spectrum antivirals. Structurally disparate compounds including FDA-approved drugs and bioactive compounds have been reported as Mpro inhibitors6, 7, 8, 9, 10, several of which also have in vivo antiviral efficacy against SARS-CoV-211, 12, 13, 14, 15.

FRET assay is the gold standard assay for protease and is typically used as a primary assay for the screening of Mpro inhibitors. However, the FRET assay conditions used by different groups vary significantly in terms of the protein and substrate concentrations, pH, reducing reagent, and detergent. Reducing reagent is typically added in the assay buffer to prevent the non-specific oxidation or alkylation of the catalytic C145 in Mpro. Nonetheless, many studies do not include reducing reagents in the FRET assay buffer, leading to debatable results16. Regardless of the assay condition, FRET assay is a cell free biochemical assay, which does not mimic the cellular environment; therefore, the results cannot be used to accurately predict the cellular activity of the Mpro inhibitor or the antiviral activity. Moreover, one limiting factor for Mpro inhibitor development is that the cellular activity has to be tested against infectious SARS-CoV-2 in BSL-3 facility, which is inaccessible to many researchers. For these reasons, there is a pressing need of secondary Mpro target-specific assays that can closely mimic the cellular environment and be used to rule out false positives.

In this study, we report our findings of validating or invalidating the literature reported Mpro inhibitors using the cell lysate Protease-Glo luciferase assay and the cell-based FlipGFP assay, in conjunction to the cell-free FRET assay and thermal shift-binding assay. The purpose is to elucidate their target specificity and cellular target engagement. The Protease-Glo luciferase assay was developed in this study, and the FlipGFP assay was recently developed by us and others17, 18, 19, 20. Our results have collectively shown that majority of the Mpro inhibitors identified from drug repurposing screening including ebselen, carmofur, disulfiram, and shikonin are promiscuous cysteine inhibitors that are not specific to Mpro, while chloroquine, oxytetracycline, montelukast, candesartan, and dipyridamole do not inhibit Mpro in any of the assays tested. The results presented herein highlight the pressing need of stringent hit validation at the early stage of drug discovery to minimize the catastrophic failure in the following translational development.

2. Methods and materials

2.1. Protein expression and purification

The tag-free SARS CoV-2 Mpro protein with native N- and C- termini was expressed in pSUMO construct as described previously3.

2.2. Enzymatic assays

The FRET-based protease was performed as described previously2. Briefly, 100 nmol/L of Mpro protein in the reaction buffer containing 20 mmol/L HEPES, pH 6.5, 120 mmol/L NaCl, 0.4 mmol/L EDTA, 4 mmol/L DTT, and 20% glycerol was incubated with serial concentrations of the testing compounds at 30 °C for 30 min. The proteolytic reactions were initiated by adding 10 μmol/L of FRET-peptide substrate [Dabcyl-KTSAVLQ/SGFRKME (Edans)] and recorded in Cytation 5 imaging reader (Thermo Fisher Scientific) with 360/460 filter cube for 1 h. The proteolytic reaction initial velocity in the presence or absence of testing compounds was determined by linear regression using the data points from the first 15 min of the kinetic progress curves. IC50 values were calculated by a 4-parameter dose−response function in Prism 8.

2.3. Thermal shift assay (TSA)

Direct binding of testing compounds to SARS CoV-2 Mpro protein was evaluated by differential scanning fluorimetry (DSF) using a Thermal Fisher QuantStudio 5 Real-Time PCR System as previously described2. Briefly, SARS CoV-2 Mpro protein was diluted into reaction buffer to a final concentration of 3 μmol/L and incubated with 40 μmol/L of testing compounds at 30 °C for 30 min. DMSO was included as a reference. SYPRO orange (1 ×, Thermal Fisher, catalog No. S6650) was added, and the fluorescence signal was recorded under a temperature gradient ranging from 20 to 95 °C with incremental step of 0.05 °C/s. The melting temperature (Tm) was calculated as the mid log of the transition phase from the native to the denatured protein using a Boltzmann model in Protein Thermal Shift Software v1.3. ΔTm was the difference between Tm in the presence of testing compounds and Tm in the presence of DMSO.

2.4. FlipGFP Mpro assay

The construction of FlipGFP-Mpro plasmid was described previously17. The assay was carried out as follows: 293T cells were seeded in 96-well black, clear bottomed Greiner plate (catalog No. 655090) and incubated overnight to reach 70%–90% confluency. 50 ng of FlipGFP-Mpro plasmid and 50 ng SARS CoV-2 Mpro expression plasmid pcDNA3.1 SARSCoV-2 Mpro were transfected into each well with transfection reagent TransIT-293 (Mirus catalog No. MIR 2700) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Three hours after transfection, 1 μL of testing compound was directly added to each well without medium change. Two days after transfection, images were taken with Cytation 5 imaging reader (Biotek) using GFP and mCherry channels via 10 × objective lens and were analyzed with Gen5 3.10 software (Biotek). The mCherry signal alone in the presence of testing compounds was utilized to evaluate the compound cytotoxicity.

2.5. Protease-Glo luciferase assay

pGlosensor-30F DEVD vector was obtained from Promega (Catlog No. CS182101). pGloSensor-30F Mpro plasmid was generated by replacing the original caspase cutting sequence (DEVDG) was with SARS CoV-2 Mpro cutting sequence (AVLQ/SGFR) from BamHI/HindIII sites. The DNA duplex containing Mpro cutting sequence was generated by annealing two 5′-phosphoriated primers: forward: GATCCGCCGTGCGCAGAGCGGCTTTCAGA; and reverse: AGCTTCTGAAGCCGCTCTGCAGCACGGCG. Protease-Glo luciferase assay was carried out as follows: 293T cells in 10 cm culture dish were transfected with pGlosensor-30F Mpro plasmid in the presence of transfection reagent TransIT-293 (Mirus catalog No. MIR 2700) according to the manufacturer's protocol. 24 h after transfection, cells were washed with PBS once, then each dish of cells was lysed with 5 mL of PBS+ 1% Trition-X100; cell debris was removed by centrifuge at 2000 × g for 10 min. Cell lysates was freshly frozen to −80 °C until ready to use. During the assay, 20 μL cell lysate was added to each well in 96-well flat bottom white plate (Fisherbrand Catalog No. 12566619), then 1 μL of testing compound or DMSO was added to each well and mixed at room temperature for 5 min. 5 μL of 200 nmol/L Escherichia coli expressed SARS CoV-2 Mpro protein was added to each well to initiate the proteolytic reaction (the final Mpro protein concentration is around 40 nmol/L). The reaction mix was further incubated at 30 °C for 30 min. The firefly and Renilla luciferase activity were determined with Dual-Glo Luciferase Assay according to manufacturer's protocol (Promega Catalog No. E2920). The efficacy of testing compounds against Mpro was evaluated by plotting the ratio of firefly luminescence signal over the Renilla luminescence signal versus the testing compound concentrations with a 4-parameter dose−response function in Prism 8.

2.6. Antiviral assay in Calu-3 cells

The antiviral assay was performed as previously described21. Calu-3 cells (ATCC, HTB-55) were plated in 384 well plates and grown in minimal Eagle's medium supplemented with 1% non-essential amino acids, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, and 10% FBS. The next day, 50 nL of compound in DMSO was added as an 8-pt dose response with three-fold dilutions between testing concentrations in triplicate, starting at 40 μmol/L final concentration. The negative control (DMSO, n = 32) and positive control (10 μmol/L remdesivir, n = 32) were included on each assay plate. Calu-3 cells were pretreated with controls and testing compounds (in triplicate) for 2 h prior to infection. In BSL-3 containment, SARS-CoV-2 (isolate USA-WA1/2020) diluted in serum free growth medium was added to plates to achieve an MOI of 0.5. Cells were incubated with compounds and SARS-CoV-2 virus for 48 h. Cells were fixed and then immunostained with anti-dsRNA (J2) and nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst 33342 for automated microscopy. Automated image analysis quantifies the number of cells per well (toxicity) and the percentage of infected cells (dsRNA + cells/cell number) per well. SARS-CoV-2 infection at each drug concentration was normalized to aggregated DMSO plate control wells and expressed as percentage-of-control:

| POC = % Infectionsample/Avg% InfectionDMSO cont | (1) |

A non-linear regression curve fit analysis (GraphPad Prism 8) of POC Infection and cell viability versus the log10 transformed concentration values to calculate EC50 values for Infection and CC50 values for cell viability. Selectivity index (SI) was calculated as a ratio of drug's CC50 and EC50 values:

| SI = CC50/IC50 | (2) |

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Assay validation using GC-376 and rupintrivir as positive and negative controls

The advantages and disadvantages of the cell lysate Protease-Glo luciferase assay and the cell-based FlipGFP assay compared to the cell free FRET assay are listed in Table 1. To minimize the bias from a particular assay, we apply all these three functional assays together with the thermal shift-binding assay for the hit validation.

Table 1.

Advantages and disadvantages of the three functional assays used in this study.

| Assay | Advantage | Disadvantage |

|---|---|---|

| FRET assay |

|

|

| FlipGFP assay |

|

|

| Protease-Glo luciferase assay |

|

|

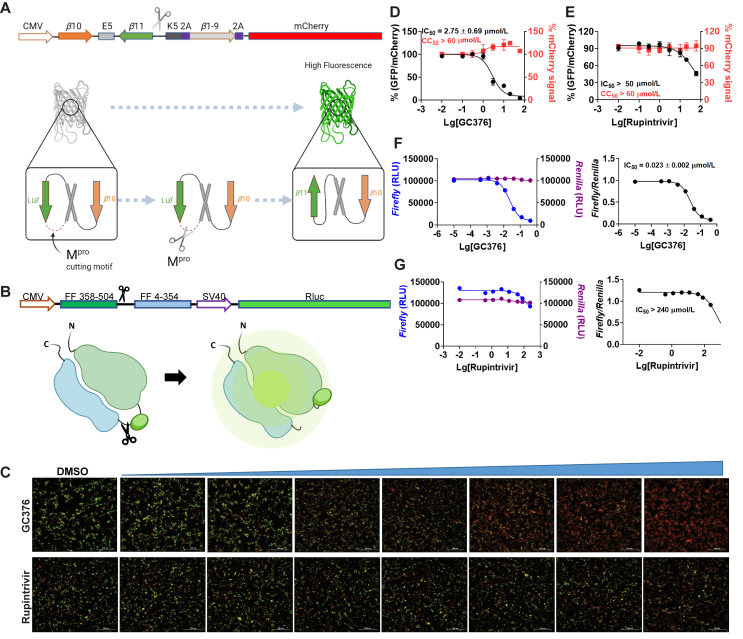

In the cell-based FlipGFP assay, the cells were transfected with two plasmids, one expresses the SARS-CoV-2 Mpro, and another expresses the GFP reporter22. The GFP reporter plasmid expresses three proteins including the GFP β10–β11 fragment flanked by the K5/E5 coiled coil, the GFP β1–9 template, and the mCherry (Fig. 1A). mCherry serves as an internal control for the normalization of the expression level or the quantification of compound toxicity. In the assay design, β10 and β11 were conformationally constrained in the parallel position by the heterodimerizing K5/E5 coiled coil with a Mpro cleavage sequence (AVLQ↓SGFR). Upon cleavage of the linker by Mpro, β10 and β11 become antiparallel and can associate with the β1–9 template, resulting in the restoration of the GFP signal. In principle, the ratio of GFP/mCherry fluorescence is proportional to the enzymatic activity of Mpro. The FlipGFP Mpro assay has been used by several groups to characterize the cellular activity of Mpro inhibitors17,19,20.

Figure 1.

Principles for the FlipGFP and Protease-Glo luciferase assays and assay validation with control compounds. (A) Assay principle for the FlipGFP assay. Diagram of the FlipGFP Mpro reporter plasmid is shown. (B) Assay principle for the Protease-Glo luciferase assay. Diagram of pGlo-Mpro luciferase reporter in the pGloSensor-30F vector is shown. (C) Representative images from the FlipGFP-Mpro assay. Dose-dependent decrease of GFP signal was observed with the increasing concentration of GC-376 (positive control); almost no GFP signal change was observed with the increasing concentration of rupintrivir (negative control). The scale bar is 300 μm. (D) and (E) Dose−response curve of the ratio of GFP/mCherry fluorescence with GC-376 and rupintrivir; mCherry signal alone was used to normalize protein expression level or calculate compound cytotoxicity. (F)–(G) Protease-Glo luciferase assay results of GC-376 and rupintrivir. Left column showed Firefly and Renilla luminescence signals in the presences of increasing concentrations of GC-376 and rupintrivir; Right column showed dose−response curve plots of the ratio of FFluc/Rluc luminescence. The results are mean ± standard deviation from three repeats. Compound concentration, μmol/L.

In the cell lysate Protease-Glo luciferase assay, the cells were transfected with pGloSensor-30F luciferase reporter (Fig. 1B)23. The pGloSensor-30F luciferase reporter plasmid expresses two proteins, the inactive, circularly permuted firefly luciferase (FFluc) and the active Renilla luciferase (Rluc). Renilla luciferase was included as an internal control to normalize the protein expression level. The firefly luciferase was split into two fragments, the FF 4–354 and FF 358–544. The SARS-CoV-2 Mpro substrate cleavage sequence (AVLQ/SGFR) was inserted in between the two fragments. Before protease cleavage, the pGloSensor-30F reporter comprises an inactive circularly permuted firefly luciferase. The cells were lysed at 24 h post transfection, and Mpro and the luciferase substrates were added to initiate the reaction. Upon protease cleavage, a conformational change in firefly luciferase leads to drastically increase in luminescence. In principle, the ratio of FFluc/Rluc luminescence is proportional to the enzymatic activity of Mpro.

To calibrate the FlipGFP and Protease-Glo luciferase assays, we chose GC-376 and rupintrivir as positive and negative controls, respectively. The IC50 values for GC-376 in the FlipGFP and Protease-Glo luciferase assays were 2.75 and 0.023 μmol/L, respectively (Fig. 1C, D, and F). The IC50 value in the FlipGFP assay is similar to its antiviral activity (Table 2), suggesting the FlipGFP can be used to predict the cellular antiviral activity. In contrast, rupintrivir showed no activity in either the FlipGFP (IC50 > 50 μmol/L) (Fig. 1C second row and 1E) or the Protease-Glo luciferase assay (IC50 > 100 μmol/L) (Fig. 1G), which agrees with the lack of inhibition from the FRET assay (IC50 > 20 μmol/L). Nonetheless, rupintrivir was reported to inhibit SARS-CoV-2 replication with an EC50 of 1.87 μmol/L using the nanoluciferase SARS-CoV-2 reporter virus (SARS-CoV-2-Nluc) in A549-hACE2 cells24 (Table 2). The discrepancy indicates that the mechanism of action of rupintrivir might be independent of Mpro inhibition. Overall, the FlipGFP and Protease-Glo luciferase assays are validated as target-specific assays for SARS-CoV-2 Mpro.

Table 2.

Summary of results.

| Compd. | FRET IC50 (μmol/L) | TSA ΔTm (°C) | FlipGFP IC50 (μmol/L) | pGlo-Mpro luciferase (μmol/L) | Anti-viral (μmol/L) Vero CPE |

PDB code | Comment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control compounds | ||||||||

|

0.030 ± 0.008 0.15 ± 0.0325 0.052 ± 0.00726 |

18.302 | 2.75 ± 1.06 | 0.023 ± 0.002 | 3.37 ± 1.682 0.7025 10 ± 4.226 |

6WTT2 6WTJ27 7C6U25 |

Positive control | |

|

>202 >1008 |

0.01 | >50 | >240 | (Nluc)1.87 ± 0.4724 | N.A. | Negative control | |

| HCV protease inhibitors | ||||||||

|

4.13 ± 0.612 2.9 ± 0.628 8.0 ± 1.525 3.129 3.7 ± 1.730 |

6.672 | 18.33 ± 3.54 | 4.49 ± 1.42 | 1.31 ± 0.582 19.628 15.5725 >5030 5.4 (293T)28 |

6XQU29 7C6S25 7COM31 |

Validated Mpro inhibitor | |

|

24.2 ± 6.1 18.7 ± 6.428 1829 17.9 ± 4.530 |

1.03 | 19.9 ± 3.0 | 41.91 ± 6.82 | >5028 20.5 (293T)28 |

6XQS29 7C7P31 7LB732 |

Validated Mpro inhibitor | |

|

5.73 ± 0.672 2.2 ± 0.428 5.129 |

5.182 | 23.8 ± 6.5 | 10.99 ± 1.96 | 7.72 15 (293T)28 |

6XQT29 7D1O33 |

Validated Mpro inhibitor | |

| HIV protease inhibitors | ||||||||

|

>602 234 ± 9830 |

−0.60 | >20 | >240 | (Nluc)9.00 ± 0.4224 19 ± 834 2535 |

N.A. | Not a Mpro inhibitor | |

|

>202 >100030 |

−0.65 | >20 | >240 | > 10035 | N.A. | Not a Mpro inhibitor | |

|

>6036 7.5 ± 0.337 |

0.19 | >60 | >240 | 2.0 ± 0.1238 | N.A. | Not a Mpro inhibitor | |

|

>202 118 ± 1830 |

−0.60 | >10 | >240 | 3.330 (Nluc)0.77 ± 0.3224 3.1 ± 0.0634 |

N.A. | Not a Mpro inhibitor | |

|

>20 6.7 ± 0.639 |

−0.65 | >20 | >240 | (Nluc)2.74 ± 0.2024 | N.A. | Not a Mpro inhibitor | |

| Calcium channel blocker | ||||||||

|

64.2 ± 9.8 4.81 ± 1.8740 |

0.45 | >10 | >240 | N.A. | N.A. | Not a Mpro inhibitor | |

| Hits from drug repurposing | ||||||||

|

0.97 ± 0.272 8.98 ± 2.026 |

6.652 | >60 | 0.60 ± 0.11 | 2.07 ± 0.762 27 ± 1.426 |

6XA43 | Validated Mpro Inhibitor Cell-type dependent |

|

|

0.45 ± 0.062 6.48 ± 3.426 |

7.862 | 38.71 ± 5.66 | 0.79 ± 0.10 | 0.49 ± 0.182 1.3 ± 0.5726 |

6XBH3 | Validated Mpro Inhibitor Cell-type dependent |

|

|

>6041 0.67 ± 0.0916,42 >10026 |

0.1441 | >60 | >60 | 4.67 ± 0.8016,42 >10026 |

7BAK42 | Not a Mpro inhibitor | |

|

>6041 9.35 ± 0.1816 |

0.2141 | >60 | >240 | not active16 | N.A. | Not a Mpro inhibitor | |

|

28.2 ± 9.541 1.82 ± 0.0616 >10026 |

0.3541 | >60 | >240 | >10026 | 7BUY43 | Not a Mpro inhibitor | |

|

>6041 21.39 ± 7.0616 |

−0.1441 | >60 | >240 | not active16 | N.A. | Not a Mpro inhibitor | |

|

>6041 1.55 ± 0.3016 |

−0.2141 | >60 | >240 | not active16 | N.A. | Not a Mpro inhibitor | |

|

>6041 15.75 ± 8.2216 15.0 ± 3.026 |

0.4041 | >20 | >240 | >10026 | 7CA844 | Not a Mpro inhibitor | |

|

>60 0.39 ± 0.1145 0.94 ± 0.2046 |

0.21 | >60 | >240 | 2.92 ± 0.0645 2.94 ± 1.1946 |

N.A. | Not a Mpro inhibitor | |

|

>20036 3.9 ± 0.237 |

0.0936 | >200 | >800 | 1.1347 | N.A. | Not a Mpro inhibitor | |

|

>20036 2.9 ± 0.337 |

0.1636 | >200 | >800 | 2.71 to 7.3648 | N.A. | Not a Mpro inhibitor | |

|

>6036 15.2 ± 0.937 |

0.1636 | >60 | >240 | N.A. | N.A. | Not a Mpro inhibitor | |

|

13.5 ± 1.036 7.3 ± 0.537 |

−0.6836 | >60 | >240 | N.A. | N.A. | Not a Mpro inhibitor | |

|

>6036 Ki = 0.62 ± 0.0537 |

0.2336 | >60 | >240 | N.A. | N.A. | Not a Mpro inhibitor | |

|

29.4 ± 3.236 0.60 ± 0.0137 |

−0.1936 | >60 | >240 | N.A. | N.A. | Not a Mpro inhibitor | |

N.A., not available.

3.2. HCV protease inhibitors

The HCV protease inhibitors have been proven a rich source of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitors2,28,29. From screening a focused protease library using the FRET assay, we discovered simeprevir, boceprevir, and narlaprevir as SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitors with IC50 values of 13.74, 4.13, and 5.73 μmol/L, respectively, while telaprevir was less active (31% inhibition at 20 μmol/L)2. The binding of boceprevir to Mpro was characterized by thermal shift assay and native mass spectrometry. Boceprevir inhibited SARS-CoV-2 viral replication in Vero E6 cells with EC50 values of 1.31 and 1.95 μmol/L in the primary CPE and secondary viral yield reduction assays, respectively (Table 2). In parallel, Fu et al.25 also reported boceprevir as a SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitor with an enzymatic inhibition IC50 of 8.0 μmol/L and an antiviral EC50 of 15.57 μmol/L. The X-ray crystal structure of Mpro with boceprevir was solved, revealing a covalent modification of the C145 thiol by the ketoamide (PDBs: 6XQU29, 7C6S25, 7COM31).

In the current study, we found that boceprevir showed moderate inhibition in the cellular FlipGFP Mpro assay with an IC50 of 18.33 μmol/L (Fig. 2A and B), a more than 4-fold increase compared to the IC50 in the FRET assay (4.13 μmol/L). The IC50 value of boceprevir in the cell lysate Protease-Glo luciferase assay was 4.49 μmol/L (Fig. 2E). In comparison, telaprevir and narlaprevir showed weaker inhibition than boceprevir in both the FlipGFP and Protease-Glo luciferase assays (Fig. 2A, C, D, F, and G), which is consistent with their weaker potency in the FRET assay (Table 2). Overall, boceprevir, telaprevir, and narlaprevir have been validated as SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitors in both the cellular FlipGFP assay and the cell lysate Protease-Glo luciferase assay. Therefore, the antiviral activity of these three compounds against SARS-CoV-2 are likely due to Mpro inhibition. Although the inhibition of Mpro by boceprevir is relatively weak compared to GC-376, several highly potent Mpro inhibitors were subsequently designed as hybrids of boceprevir and GC-37611,17,31 including the Pfizer oral drug candidate PF-07321332, which contain the dimethylcyclopropylproline at the P2 substitution.

Figure 2.

Validation/invalidation of hepatitis C virus NS3/4A protease inhibitors boceprevir, telaprevir, and narlaprevir as SARS CoV-2 Mpro inhibitors using the FlipGFP assay and Protease-Glo luciferase assay. (A) Representative images from the FlipGFP-Mpro assay. Dose-dependent decrease of GFP signal was observed with the increasing concentration of boceprevir, telaprevir or narlaprevir. The scale bar is 300 μm. (B)–(D) Dose−response curve of the GFP and mCherry fluorescent signals for boceprevir (B), telaprevir (C) or narlaprevir (D); mCherry signal alone was used to normalize protein expression level or calculate compound toxicity. (E)–(G) Protease-Glo luciferase assay results of boceprevir (E), telaprevir (F) or narlaprevir (G). Left column shows Firefly and Renilla luminescence signals in the presences of increasing concentrations of boceprevir, telaprevir or narlaprevir; Right column shows dose−response curve plots of the ratio of FFluc/Rlu luminescence. Renilla luminescence signal alone was used to normalize protein expression level. The results are mean ± standard deviation from three repeats. Compound concentration, μmol/L.

3.3. HIV protease inhibitors

HIV protease inhibitors, especially Kaletra, have been hotly pursued as potential COVID-19 treatment at the beginning of the pandemic. Kaletra was first tested in clinical trial during the SARS-CoV outbreak in 2003 and showed somewhat promising results based on the limited data49. However, a double-blinded, randomized trial concluded that Kaletra was not effective in treating severe COVID-1950,51. In SARS-CoV-2 infection ferret models, Kaletra showed marginal effect in reducing clinical symptoms, while had no effect on virus titers52.

Keletra is a combination of lopinavir and ritonavir. Lopinavir is a HIV protease inhibitor, and ritonavir is used as a booster. Ritonavir does not inhibit the HIV protease and it is a cytochrome P450-3A4 inhibitor53. When used in combination, ritonavir can enhance other protease inhibitors by preventing or slowing down the metabolism. In cell culture, lopinavir was reported to inhibit the nanoluciferase SARS-CoV-2 reporter virus with an EC50 of 9 μmol/L24. In two other studies, lopinavir showed moderate antiviral activity against SARS-CoV-2 activity with EC50 values of 19 ± 8 μmol/L34 and 25 μmol/L35. As such, it was assumed that lopinavir inhibited SARS-CoV-2 through inhibiting the Mpro. However, lopinavir showed no activity against SARS-CoV-2 Mpro in the FRET assay from our previous study (IC50 > 60 μmol/L)2. Wu et al.54 also showed that lopinavir was a weak inhibitor against SARS-CoV Mpro with an IC50 of 50 μmol/L. In the current study, we further confirmed the lack of binding of lopinavir to SARS-CoV-2 Mpro in the thermal shift assay (ΔTm = −0.60 °C, Table 2). The result from the FlipGFP assay was not conclusive as lopinavir was cytotoxic. Lopinavir was not active in the Protease-Glo luciferase assay. Taken together, lopinavir is not a Mpro inhibitor.

Ritonavir was not active in both the FlipGFP Mpro and the Protease-Glo luciferase assays, which is consistent with the lack of activity in the FRET assay and the thermal shift binding assay (Table 2). Therefore, ritonavir is not a Mpro inhibitor.

We also tested additional HIV antivirals including atazanavir, nelfinavir, and cobicistat. Atazanavir and nelfinavir were reported as a potent SARS-CoV-2 antiviral with EC50 values of 2.0 ± 0.1238 and 0.77 μmol/L24 using the infectious SARS-CoV-2 and the nanoluciferase reporter virus (SARS-CoV-2-Nluc), respectively. A drug repurposing screening similar identified nelfinavir as a SARS-CoV-2 antiviral with an IC50 of 3.3 μmol/L30. Gupta et al.39 showed that cobicistat inhibited Mpro with an IC50 of 6.7 μmol/L in the FRET assay. Cobicistat was also reported to have antiviral activity against SARS-CoV-2 with an EC50 of 2.74 ± 0.20 μmol/L using the SARS-CoV-2-Nluc reporter virus24. However, our FRET assay showed that nelfinavir and cobicistat did not inhibit Mpro in the FRET assay (IC50 > 20 μmol/L), which was further confirmed by the lack of binding to Mpro in the thermal shift assay (Table 2). The results of atazanavir, nelfinavir, and cobicistat from the FlipGFP assay were not conclusive due to compound cytotoxicity (Fig. 3A–F). None of the compounds showed inhibition in the Protease-Glo luciferase assay (Fig. 3G–K).

Figure 3.

Validation/invalidation of HIV protease inhibitors lopinavir, ritonavir, atazanavir, nelfinavir, and cobicistat as SARS CoV-2 Mpro inhibitors using the FlipGFP assay and Protease-Glo luciferase assay. (A) Representative images from the FlipGFP-Mpro assay. The scale bar is 300 μm. (B)–(F) Dose−response curve of the GFP and mCherry fluorescent signals for lopinavir (B), ritonavir (C), atazanavir (D), nelfinavir (E), and cobicistat (F); mCherry signal alone was used to normalize protein expression level or calculate compound cytotoxicity. (G)–(K) Protease-Glo luciferase assay results of lopinavir (G), ritonavir (H), atazanavir (I), nelfinavir (J), and cobicistat (K). Left column shows Firefly and Renilla luminescence signals in the presences of increasing concentrations of lopinavir, ritonavir, atazanavir, nelfinavir, and cobicistat; Right column shows dose−response curve plots of ratio of FFluc/Rluc luminescence. Renilla luminescence signal alone was used to normalize protein expression level. None of the compounds shows significant inhibition in the presence of up to 240 μmol/L compounds. The results are mean ± standard deviation from three repeats. Compound concentration, μmol/L.

Collectively, our results have shown that the HIV protease inhibitors including lopinavir, ritonavir, atazanavir, nelfinavir, and cobicistat are not Mpro inhibitors. Nonetheless, given the potent antiviral activity of lopinavir, atazanavir, nelfinavir, and cobicistat against SARS-CoV-2, it might worth to conduct resistance selection to elucidate their drug target(s).

3.4. Bioactive compounds from drug repurposing

Several bioactive compounds have been identified as SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitors through either virtual screening or FRET-based HTS. We are interested in validating these hits using the FlipGFP and the Protease-Glo luciferase assays.

Manidipine was identified as a SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitor from a virtual screening and was subsequently shown to inhibit Mpro with an IC50 of 4.81 μmol/L in the FRET assay40. No antiviral data was provided. When we repeated the FRET assay, the IC50 was 64.2 μmol/L (Table 2). Manidipine also did not show binding to Mpro in the thermal shift assay. Furthermore, manidipine showed no activity in either the FlipGFP assay or the Protease-Glo luciferase assay (Fig. 4A, B, and F). Therefore, our results invalidated manidipine as a SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitor. A recent study independently confirmed our results and suggested that manidipine might form colloidal aggregates55, leading to inactivation of Mpro. In the presence of 0.05% Tween-20, manidipine was not active against Mpro in the FRET assay (IC50 > 100 μmol/L).

Figure 4.

Validation/invalidation of manidipine, calpain inhibitors II and XII, and ebselen as SARS CoV-2 Mpro inhibitors using the FlipGFP assay and Protease-Glo luciferase assay. (A) Representative images from the FlipGFP-Mpro assay. The scale bar is 300 μm. (B)–(E) Dose−response curve of the GFP and mCherry fluorescent signals for manidipine (B), calpain inhibitor II (C), calpain inhibitor XII (D), and ebselen (E); mCherry signal alone was used to normalize protein expression level or calculate compound cytotoxicity. (F)–(I) Protease-Glo luciferase assay results of manidipine (F), calpain inhibitor II (G), calpain inhibitor XII (H), and ebselen (I). Left column shows Firefly and Renilla luminescence signals in the presences of increasing concentrations of lopinavir, ritonavir, atazanavir, nelfinavir, and cobicistat; Right column shows dose−response curve plots of the ratio of FFluc/Rluc luminescence. Renilla luminescence signal alone was used to normalize protein expression level. (J)–(K) Antiviral activity of remdesivir (J), calpain inhibitor II (K), and calpain inhibitor XII (L) against SARS-CoV-2 in Calu-3 cells. The results are mean ± standard deviation from three repeats. Compound concentration, μmol/L.

In the same screening which we identified boceprevir as a SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitor, calpain inhibitors II and XII were also found to have potent inhibition against Mpro with IC50 values of 0.97 and 0.45 μmol/L in the FRET assay2. Both compounds showed binding to Mpro in the thermal shift and native mass spectrometry binding assays. The Protease-Glo luciferase assay similarly confirmed the potent inhibition of calpain inhibitors II and XII against Mpro with IC50 values of 0.60 and 0.79 μmol/L, respectively (Fig. 4G and H). However, calpain inhibitor II had no effect on the cellular Mpro activity as shown by the lack of inhibition in the FlipGFP assay (IC50 > 60 μmol/L, Fig. 4A and C), while calpain inhibitor XII showed weak activity (IC50 = 38.71 μmol/L, Fig. 4A and D). A recent study by Cao et al.45 using a Mpro trigged cytotoxicity assay similarly found the lack of cellular Mpro inhibition by calpain inhibitors II and XII. These results contradict to the potent antiviral activity of both compounds in Vero E6 cells2. It is noted that calpain inhibitors II and XII are also potent inhibitors of cathepsin L with IC50 values of 0.41 and 1.62 nmol/L, respectively3. One possible explanation is that the antiviral activity of calpain inhibitors II and XII against SARS-CoV-2 might be cell type dependent, and the observed inhibition in Vero E6 cells might be due to cathepsin L inhibition instead of Mpro inhibition. Vero E6 cells are TMPRSS2 negative, and SARS-CoV-2 enters cell mainly through endocytosis and is susceptible to cathepsin L inhibitors56. To further evaluate the antiviral activity of calpain inhibitors II and XII against SARS-CoV-2, we tested them in Calu-3 cells using the immunofluorescence assay (Fig. 4J, K, and L). Calu-3 is TMPRSS2 positive and it is a close mimetic of the human primary epithelial cell57. As expected, calpain inhibitors II and XII displayed much weaker antiviral activity against SARS-CoV-2 in Calu-3 cells than in Vero E6 cells with EC50 values of 30.34 and 14.78 μmol/L, respectively (Fig. 4K and L). These results suggest that the FlipGFP assay can be used to faithfully predict the antiviral activity of Mpro inhibitors. The lower activity of calpain inhibitors II and XII in the FlipGFP assay and the Calu-3 antiviral assay might due to the competition with host proteases, resulting in the lack of cellular target engagement with Mpro.

In conclusion, calpain inhibitors II and XII are validated as Mpro inhibitors but their antiviral activity against SARS-CoV-2 is cell type dependent. Accordingly, TMPRSS2 positive cell lines such as Calu-3 should be used to test the antiviral activity of calpain inhibitors II and XII analogs.

Ebselen is among one of the most frequently reported promiscuous Mpro inhibitors. It was first reported by Jin et al.16 that ebselen inhibits SARS-CoV-2 Mpro with an IC50 of 0.67 μmol/L and the SARS-CoV-2 replication with an EC50 of 4.67 μmol/L. However, it was noted that no reducing reagent was added in the FRET assay, and we reasoned that the observed inhibition might be due to non-specific modification of the catalytic cysteine 145 by ebselen. To test this hypothesis, we repeated the FRET assay with and without reducing reagent DTT or GSH, and found that ebselen completely lost the Mpro inhibition in the presence of DTT or GSH41. Similarly, ebselen also non-specifically inhibited several other viral cysteine proteases in the absence of DTT including SARS-CoV-2 PLpro, EV-D68 2Apro and 3Cpro, and EV-A71 2Apro and 3Cpro41. The inhibition was abolished with the addition of DTT. Ebselen also had no antiviral activity against EV-A71 and EV-D68, suggesting that the FRET assay results obtained without reducing reagent cannot be used to predict the antiviral activity. In this study, we found that ebselen showed no inhibition in either the FlipGFP assay or the Protease-Glo luciferase assay (Fig. 4A, E, and I), providing further evidence for the promiscuous mechanism of action of ebselen. Another independent study by Gurard-Levin et al.26 using mass spectrometry assay reached similar conclusion that the inhibition of Mpro by ebselen is non-specific and inhibition was abolished with the addition of reducing reagent DTT or glutathione. In contrary to the potent antiviral activity reported by Jin et al.16, the study from Gurard-Levin et al.26 found that ebselen was inactive against SARS-CoV-2 in Vero E6 cells (EC50 > 100 μmol/L). Chen et al.58 reported that ebselen and disulfiram had synergistic antiviral effect with remdesivir against SARS-CoV-2 in Vero E6 cells. It was also proposed that ebselen and disulfiram act as zinc ejectors and inhibited not only the PLpro59, but also the nsp13 ATPase and nsp14 exoribonuclease activities58, further casting doubt on the detailed mechanism of action of ebselen.

Despite the accumulating evidence to support the promiscuous mechanism of action of ebselen, several studies continue to explore ebselen and its analogs as SARS-CoV-2 Mpro and PLpro inhibitors42,60,61. A number of ebselen analogs were designed and found to have comparable enzymatic inhibition and antiviral activity as ebselen. MR6-31-2 had slightly weaker enzymatic inhibition against SARS-CoV-2 Mpro compared to ebselen (IC50 = 0.824 vs. 0.67 μmol/L); however, MR6-31-2 had more potent antiviral activity than ebselen (EC50 = 1.78 vs. 4.67 μmol/L) against SARS-CoV-2 Mpro in Vero E6 cells. X-ray crystallization of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro with MR6-31-2 (PDB: 7BAL) and ebselen (PDB: 7BAK) revealed nearly identical complex structures. It was found that selenium coordinates directly to Cys145 and forms a S–Se bond42. Accordingly, a mechanism involving hydrolysis of the organoselenium compounds was proposed. Similar to their previous study, the Mpro enzymatic reaction buffer (50 mmol/L Tris pH 7.3, 1 mmol/L EDTA) did not include the reducing reagent DTT. Therefore, the Mpro inhibition by these ebselen analogs might be non-specific and the antiviral activity might arise from other mechanisms42.

Overall, it can be concluded that ebselen is not a specific Mpro inhibitor, and its antiviral activity against SARS-CoV-2 might involve other drug targets such as nsp13 or nsp14.

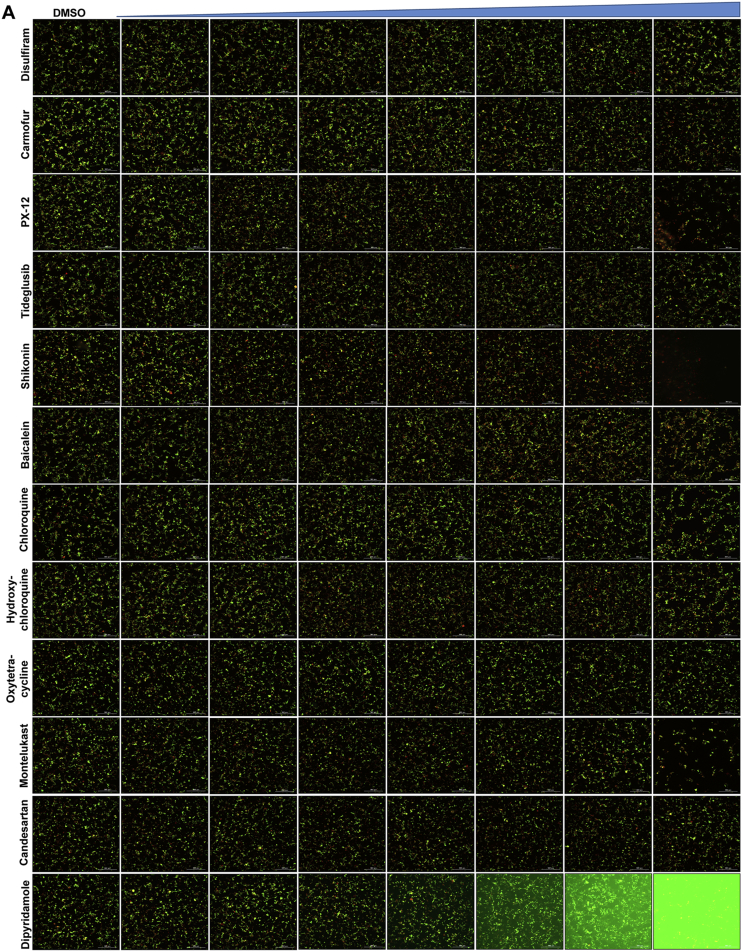

Disulfiram is an FDA-approved drug for alcohol aversion therapy. Disulfiram has a polypharmacology and was reported to inhibit multiple enzymes including urease62, methyltransferase63, and kinase62 through reacting with cysteine residues. Disulfiram was also reported as an allosteric inhibitor of MERS-CoV PLpro64. Yang et al. reported disulfiram as a Mpro inhibitor with an IC50 of 9.35 μmol/L. Follow up studies by us and others showed that disulfiram did not inhibit Mpro in the presence of DTT or GSH26,41. In this study, disulfiram had no inhibition against Mpro in either the FlipGFP assay or the Protease-Glo luciferase assay (Fig. 5A, B and N).

Figure 5.

Validation/invalidation of disulfiram, carmofur, PX-12, tideglusib, shikonin, baicalein, chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine, oxytetracycline, montelukast, candesartan, and dipyridamole as SARS CoV-2 Mpro inhibitors using the FlipGFP assay and Protease-Glo luciferase assay. (A) Representative images from the FlipGFP-Mpro assay. The fluorescent background for dipyridamole at high drug concentrations (last row) was caused by the fluorescence emission from the compound itself. The scale bar is 300 μm. (B)–(M) Dose−response curve of the ratio of GFP/mCherry fluorescent signal for disulfiram (B), carmofur (C), PX-12 (D), tideglusib (E), shikonin (F), baicalein (G), chloroquine (H), hydroxychloroquine (I), oxytetracycline (J), montelukast (K), candesartan (L), and dipyridamole (M); mCherry signal alone was used to normalize protein expression level or calculate compound cytotoxicity. (N)–(Y) Protease-Glo luciferase assay results of disulfiram (N), carmofur (O), PX-12 (P), tideglusib (Q), shikonin (R), baicalein (S), chloroquine (T), hydroxychloroquine (U), oxytetracycline (V), montelukast (W), candesartan (X), and dipyridamole (Y). Left column shows Firefly and Renilla luminescence signals in the presences of increasing concentrations of disulfiram, carmofur, PX-12, tideglusib, shikonin, baicalein, chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine, oxytetracycline, montelukast, candesartan, and dipyridamole; Right column shows dose−response curve plots of the ratio of FFluc/Rluc luminescence. Renilla luminescence signal alone was used to normalize protein expression level. The results are mean ± standard deviation from three repeats. Compound concentration, μmol/L.

Similar to disulfiram, carmofur, PX-12 and tideglusib, which were previously claimed by Jin et al.16 as Mpro inhibitors, showed no inhibitory activity in either the FlipGFP or Protease-Glo luciferase assay (Fig. 5A, C, D, E, O–Q), which is consistent with their lack of inhibition in the FRET assay in the presence of DTT.

Shikonin and baicalein are polyphenol natural products with known polypharmacology. Both compounds showed no inhibition in either the FlipGFP or the Protease-Glo luciferase assay (Fig. 5A, F, G, R, and S), suggesting they are not Mpro inhibitors. These two compounds were previously reported to inhibit SARS-CoV-2 Mpro in the FRET assay16, 45, 46 and had antiviral activity against SARS-CoV-2 in Vero E6 cells. However, our recent study showed that shikonin had no inhibition against SARS-CoV-2 Mpro in the FRET assay in the presence of DTT41. Studies from Gurard-Levin et al.26 using FRET assay and mass spectrometry assay reached the same conclusion. X-ray crystal structure of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro in complex with shikonin showed that shikonin binds to the active site in a non-covalent manner44.

In addition to the proposed mechanism of action of Mpro inhibition, Zandi et al.65 showed that baicalein and baicalin inhibit the SARS-CoV-2 RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. Overall, shikonin and baicalein are not Mpro inhibitors and the antiviral activity of baicalein against SARS-CoV-2 might involve other mechanisms.

A recent study from Li et al.37 identified several known drugs as SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitors from a virtual screening. The identified compounds include chloroquine (IC50 = 3.9 ± 0.2 μmol/L; Ki = 0.56 ± 0.12 μmol/L), hydroxychloroquine (IC50 = 2.9 ± 0.3 μmol/L; Ki = 0.36 ± 0.21 μmol/L), oxytetracycline (IC50 = 15.2 ± 0.9 μmol/L; Ki = 0.99 ± 0.06 μmol/L), montelukast (IC50 = 7.3 ± 0.5 μmol/L), Ki = 0.48 ± 0.04 μmol/L), candesartan (IC50 = 2.8 ± 0.3 μmol/L; Ki = 0.18 ± 0.02 μmol/L), and dipyridamole (Ki = 0.04 ± 0.001 μmol/L). The discovery of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine as Mpro inhibitor was particularly intriguing. Several high-throughput screenings have been conducted for Mpro30,66, and chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine were not among the list of active hits. In our follow up study, we found that none of the identified hits reported by Luo et al. inhibited Mpro either with or without DTT in the FRET assay5. In corroborate with our previous finding, the FlipGFP and Protease-Glo luciferase assays similarly confirmed the lack of inhibition of these compounds against Mpro (Fig. 5A, H–M, T–Y). Therefore, it can be concluded that chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine, oxytetracycline, montelukast, candesartan, and dipyridamole are not SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitors. Other than the claims made by Luo et al., no other studies have independently confirmed these compounds as Mpro inhibitors.

4. Conclusions

The Mpro is perhaps the most extensive exploited drug target for SARS-CoV-2. A variety of drug discovery techniques have been applied to search for Mpro inhibitors. Researchers around the world are racing to share their findings with the scientific community to expedite the drug discovery process. However, the quality of science should not be compromised by the speed. The mechanism of action of drug candidates should be thoroughly characterized in biochemical, binding, and cellular assays. Pharmacological characterization should address both target specificity and cellular target engagement. For target specificity, the drug candidates can be counter screened against unrelated cysteine proteases such as the viral EV-A71 2Apro, EV-D68 2Apro, the host cathepsins B, L, and K, caspases, calpains I, II, and III, etc. Compounds inhibit multiple cysteine proteases non-discriminately are most likely promiscuous compounds that act through redox cycling, inducing protein aggregation, or alkylating catalytic cysteine residue C145. For cellular target engagement, the FlipGFP and Protease-Glo luciferase assays can be applied. Both assays are performed in the presence of competing host proteins at the cellular environment. Collectively, our study reaches the following conclusions: 1) for validated Mpro inhibitors, the IC50 values with and without reducing reagent should be about the same in the FRET assay; 2) validated Mpro inhibitors should show consistent results in the FRET assay, thermal shift binding assay, and the Protease-Glo luciferase assay. For compounds that are not cytotoxic, they should also be active in the FlipGFP assay; 3) compounds that have antiviral activity but lack consistent results from the FRET, thermal shift, FlipGFP, and Protease-Glo luciferase assays should not be classified as Mpro inhibitors; 4) compounds that non-specifically inhibit multiple unrelated viral or host cysteine proteases are most likely promiscuous inhibitors that should be triaged. 5) X-ray crystal structures cannot be used to justify the target specificity or cellular target engagement. Promiscuous compounds have been frequently co-crystallized with Mpro including ebselen, carmofur, and shikonin (Table 2). Overall, we hope our studies will promote the awareness of the promiscuous SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitors among the scientific community and call for more stringent hit validation.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseasess at the National Instiute of Health (NIH, USA; grants AI147325, AI157046, and AI158775) and the Arizona Biomedical Research Centre Young Investigator grant (ADHS18-198859, USA) to Jun Wang. The SARS-CoV-2 antiviral assay in Calu-3 cells was conducted by Drs. David Schultz and Sara Cherry at the University of Pennsylvania (USA) through the NIAID preclinical service under a non-clinical evaluation agreement.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chinese Pharmaceutical Association and Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences

Author contributions

Chunlong Ma performed the FlipGFP assay, Protease-Glo luciferase assay, and thermal shift assay with the assistance from Haozhou Tan. Juliana Choza and Yuyin Wang expressed the Mpro and performed the FRET assay. Jun Wang wrote the draft manuscript with the input from others; Jun Wang submitted this manuscript on behalf of other authors.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Hu B., Guo H., Zhou P., Shi Z.L. Characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2020;19:141–154. doi: 10.1038/s41579-020-00459-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ma C., Sacco M.D., Hurst B., Townsend J.A., Hu Y., Szeto T., et al. Boceprevir, GC-376, and calpain inhibitors II, XII inhibit SARS-CoV-2 viral replication by targeting the viral main protease. Cell Res. 2020;30:678–692. doi: 10.1038/s41422-020-0356-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sacco M.D., Ma C., Lagarias P., Gao A., Townsend J.A., Meng X., et al. Structure and inhibition of the SARS-CoV-2 main protease reveal strategy for developing dual inhibitors against Mpro and cathepsin L. Sci Adv. 2020;6 doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abe0751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gao X., Qin B., Chen P., Zhu K., Hou P., Wojdyla J.A., et al. Crystal structure of SARS-CoV-2 papain-like protease. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2021;11:237–245. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2020.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rut W., Groborz K., Zhang L., Sun X., Zmudzinski M., Pawlik B., et al. SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitors and activity-based probes for patient-sample imaging. Nat Chem Biol. 2021;17:222–228. doi: 10.1038/s41589-020-00689-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ghosh A.K., Brindisi M., Shahabi D., Chapman M.E., Mesecar A.D. Drug development and medicinal chemistry efforts toward SARS-coronavirus and COVID-19 therapeutics. ChemMedChem. 2020;15:907–932. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.202000223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ullrich S., Nitsche C. The SARS-CoV-2 main protease as drug target. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2020;30:127377. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2020.127377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vatansever E.C., Yang K.S., Drelich A.K., Kratch K.C., Cho C.C., Kempaiah K.R., et al. Bepridil is potent against SARS-CoV-2 in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021;118 doi: 10.1073/pnas.2012201118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gao S., Huang T., Song L., Xu S., Cheng Y., Cherukupalli S., et al. Medicinal chemistry strategies towards the development of effective SARS-CoV-2 inhibitors. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2022;12:581–599. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2021.08.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xiang R., Yu Z., Wang Y., Wang L., Huo S., Li Y., et al. Recent advances in developing small-molecule inhibitors against SARS-CoV-2. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2022;12:1591–1622. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2021.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Owen D.R., Allerton C.M.N., Anderson A.S., Aschenbrenner L., Avery M., Berritt S., et al. An oral SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitor clinical candidate for the treatment of COVID-19. Science. 2021;374:1586–1593. doi: 10.1126/science.abl4784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Drayman N., DeMarco J.K., Jones K.A., Azizi S.A., Froggatt H.M., Tan K., et al. Masitinib is a broad coronavirus 3CL inhibitor that blocks replication of SARS-CoV-2. Science. 2021;373:931–936. doi: 10.1126/science.abg5827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Caceres C.J., Cardenas-Garcia S., Carnaccini S., Seibert B., Rajao D.S., Wang J., et al. Efficacy of GC-376 against SARS-CoV-2 virus infection in the K18 hACE2 transgenic mouse model. Sci Rep. 2021;11:9609. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-89013-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dampalla C.S., Zheng J., Perera K.D., Wong L.R., Meyerholz D.K., Nguyen H.N., et al. Postinfection treatment with a protease inhibitor increases survival of mice with a fatal SARS-CoV-2 infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021;118 doi: 10.1073/pnas.2101555118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shi Y., Shuai L., Wen Z., Wang C., Yan Y., Jiao Z., et al. The preclinical inhibitor GS441524 in combination with GC376 efficaciously inhibited the proliferation of SARS-CoV-2 in the mouse respiratory tract. Emerg Microb Infect. 2021;10:481–492. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2021.1899770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jin Z., Du X., Xu Y., Deng Y., Liu M., Zhao Y., et al. Structure of Mpro from SARS-CoV-2 and discovery of its inhibitors. Nature. 2020;582:289–293. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2223-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xia Z., Sacco M., Hu Y., Ma C., Meng X., Zhang F., et al. Rational design of hybrid SARS-CoV-2 main protease inhibitors guided by the superimposed cocrystal structures with the peptidomimetic inhibitors GC-376, telaprevir, and boceprevir. ACS Pharmacol Transl Sci. 2021;4:1408–1421. doi: 10.1021/acsptsci.1c00099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ma C., Sacco M.D., Xia Z., Lambrinidis G., Townsend J.A., Hu Y., et al. Discovery of SARS-CoV-2 papain-like protease inhibitors through a combination of high-throughput screening and a FlipGFP-based reporter assay. ACS Cent Sci. 2021;7:1245–1260. doi: 10.1021/acscentsci.1c00519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Froggatt H.M., Heaton B.E., Heaton N.S. Development of a fluorescence-based, high-throughput SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro reporter assay. J Virol. 2020;94 doi: 10.1128/JVI.01265-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li X., Lidsky P., Xiao Y., Wu C.-T., Garcia-Knight M., Yang J., et al. Ethacridine inhibits SARS-CoV-2 by inactivating viral particles. PLoS Pathog. 2021;17:e1009898. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1009898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kitamura N., Sacco M.D., Ma C., Hu Y., Townsend J.A., Meng X., et al. Expedited approach toward the rational design of noncovalent SARS-CoV-2 main protease inhibitors. J Med Chem. 2022;65:2848–2865. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.1c00509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang Q., Schepis A., Huang H., Yang J., Ma W., Torra J., et al. Designing a green fluorogenic protease reporter by flipping a beta strand of GFP for imaging apoptosis in animals. J Am Chem Soc. 2019;141:4526–4530. doi: 10.1021/jacs.8b13042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wigdal S.S., Anderson J.L., Vidugiris G.J., Shultz J., Wood K.V., Fan F. A novel bioluminescent protease assay using engineered firefly luciferase. Curr Chem Genom. 2008;2:16–28. doi: 10.2174/1875397300802010016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xie X., Muruato A.E., Zhang X., Lokugamage K.G., Fontes-Garfias C.R., Zou J., et al. A nanoluciferase SARS-CoV-2 for rapid neutralization testing and screening of anti-infective drugs for COVID-19. Nat Commun. 2020;11:5214. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-19055-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fu L., Ye F., Feng Y., Yu F., Wang Q., Wu Y., et al. Both boceprevir and GC376 efficaciously inhibit SARS-CoV-2 by targeting its main protease. Nat Commun. 2020;11:4417. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-18233-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gurard-Levin Z.A., Liu C., Jekle A., Jaisinghani R., Ren S., Vandyck K., et al. Evaluation of SARS-CoV-2 3C-like protease inhibitors using self-assembled monolayer desorption ionization mass spectrometry. Antivir Res. 2020;182:104924. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2020.104924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vuong W., Khan M.B., Fischer C., Arutyunova E., Lamer T., Shields J., et al. Feline coronavirus drug inhibits the main protease of SARS-CoV-2 and blocks virus replication. Nat Commun. 2020;11:4282. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-18096-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bafna K., White K., Harish B., Rosales R., Ramelot T.A., Acton T.B., et al. Hepatitis C virus drugs that inhibit SARS-CoV-2 papain-like protease synergize with remdesivir to suppress viral replication in cell culture. Cell Rep. 2021;35:109133. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2021.109133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kneller D.W., Galanie S., Phillips G., O'Neill H.M., Coates L., Kovalevsky A. Malleability of the SARS-CoV-2 3CL Mpro active-site cavity facilitates binding of clinical antivirals. Structure. 2020;28:1313–1320.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2020.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jan J.T., Cheng T.R., Juang Y.P., Ma H.H., Wu Y.T., Yang W.B., et al. Identification of existing pharmaceuticals and herbal medicines as inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021;118 doi: 10.1073/pnas.2021579118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Qiao J., Li Y.S., Zeng R., Liu F.L., Luo R.H., Huang C., et al. SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitors with antiviral activity in a transgenic mouse model. Science. 2021;371:1374–1378. doi: 10.1126/science.abf1611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kneller D.W., Phillips G., Weiss K.L., Zhang Q., Coates L., Kovalevsky A. Direct observation of protonation state modulation in SARS-CoV-2 main protease upon inhibitor binding with neutron crystallography. J Med Chem. 2021;64:4991–5000. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.1c00058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bai Y., Ye F., Feng Y., Liao H., Song H., Qi J., et al. Structural basis for the inhibition of the SARS-CoV-2 main protease by the anti-HCV drug narlaprevir. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2021;6:51. doi: 10.1038/s41392-021-00468-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hattori S.I., Higshi-Kuwata N., Raghavaiah J., Das D., Bulut H., Davis D.A., et al. GRL-0920, an indole chloropyridinyl ester, completely blocks SARS-CoV-2 infection. mBio. 2020;11 doi: 10.1128/mBio.01833-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Choy K.-T., Wong A.Y.-L., Kaewpreedee P., Sia S.F., Chen D., Hui K.P.Y., et al. Remdesivir, lopinavir, emetine, and homoharringtonine inhibit SARS-CoV-2 replication in vitro. Antivir Res. 2020;178:104786. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2020.104786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ma C., Wang J. Dipyridamole, chloroquine, montelukast sodium, candesartan, oxytetracycline, and atazanavir are not SARS-CoV-2 main protease inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021;118 doi: 10.1073/pnas.2024420118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li Z., Li X., Huang Y.Y., Wu Y., Liu R., Zhou L., et al. Identify potent SARS-CoV-2 main protease inhibitors via accelerated free energy perturbation-based virtual screening of existing drugs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117:27381–27387. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2010470117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fintelman-Rodrigues N., Sacramento C.Q., Ribeiro Lima C., Souza da Silva F., Ferreira A.C., Mattos M., et al. Atazanavir, alone or in combination with ritonavir, inhibits SARS-CoV-2 replication and proinflammatory cytokine production. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2020;64 doi: 10.1128/AAC.00825-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gupta A., Rani C., Pant P., Vijayan V., Vikram N., Kaur P., et al. Structure-based virtual screening and biochemical validation to discover a potential inhibitor of the SARS-CoV-2 main protease. ACS Omega. 2020;5:33151–33161. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.0c04808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ghahremanpour M.M., Tirado-Rives J., Deshmukh M., Ippolito J.A., Zhang C.H., Cabeza de Vaca I., et al. Identification of 14 known drugs as inhibitors of the main protease of SARS-CoV-2. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2020;11:2526–2533. doi: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.0c00521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ma C., Hu Y., Townsend J.A., Lagarias P.I., Marty M.T., Kolocouris A., et al. Ebselen, disulfiram, carmofur, PX-12, tideglusib, and shikonin are nonspecific promiscuous SARS-CoV-2 main protease inhibitors. ACS Pharmacol Transl Sci. 2020;3:1265–1277. doi: 10.1021/acsptsci.0c00130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Amporndanai K., Meng X., Shang W., Jin Z., Rogers M., Zhao Y., et al. Inhibition mechanism of SARS-CoV-2 main protease by ebselen and its derivatives. Nat Commun. 2021;12:3061. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-23313-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jin Z., Zhao Y., Sun Y., Zhang B., Wang H., Wu Y., et al. Structural basis for the inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 main protease by antineoplastic drug carmofur. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2020;27:529–532. doi: 10.1038/s41594-020-0440-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li J., Zhou X., Zhang Y., Zhong F., Lin C., McCormick P.J., et al. Crystal structure of SARS-CoV-2 main protease in complex with the natural product inhibitor shikonin illuminates a unique binding mode. Sci Bull (Beijing) 2021;66:661–663. doi: 10.1016/j.scib.2020.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cao W., Cho C.C.D., Geng Z.Z., Ma X.R., Allen R., Shaabani N., et al. Cellular activities of SARS-CoV-2 main protease inhibitors reveal their unique characteristics. bioRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1101/2021.06.08.447613. Available from: [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Su H.X., Yao S., Zhao W.F., Li M.J., Liu J., Shang W.J., et al. Anti-SARS-CoV-2 activities in vitro of Shuanghuanglian preparations and bioactive ingredients. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2020;41:1167–1177. doi: 10.1038/s41401-020-0483-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang M., Cao R., Zhang L., Yang X., Liu J., Xu M., et al. Remdesivir and chloroquine effectively inhibit the recently emerged novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in vitro. Cell Res. 2020;30:269–271. doi: 10.1038/s41422-020-0282-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu J., Cao R., Xu M., Wang X., Zhang H., Hu H., et al. Hydroxychloroquine, a less toxic derivative of chloroquine, is effective in inhibiting SARS-CoV-2 infection in vitro. Cell Discov. 2020;6:16. doi: 10.1038/s41421-020-0156-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chu C.M., Cheng V.C., Hung I.F., Wong M.M., Chan K.H., Chan K.S., et al. Role of lopinavir/ritonavir in the treatment of SARS: initial virological and clinical findings. Thorax. 2004;59:252–256. doi: 10.1136/thorax.2003.012658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cao B., Wang Y., Wen D., Liu W., Wang J., Fan G., et al. A trial of lopinavir–ritonavir in adults hospitalized with severe Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1787–1799. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Group R.C. Lopinavir–ritonavir in patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19 (RECOVERY): a randomised, controlled, open-label, platform trial. Lancet. 2020;396:1345–1352. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32013-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Park S.J., Yu K.M., Kim Y.I., Kim S.M., Kim E.H., Kim S.G., et al. Antiviral efficacies of FDA-approved drugs against SARS-CoV-2 infection in Ferrets. mBio. 2020;11:e01114–e01120. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01114-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zeldin R.K., Petruschke R.A. Pharmacological and therapeutic properties of ritonavir-boosted protease inhibitor therapy in HIV-infected patients. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2004;53:4–9. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkh029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wu C.Y., Jan J.T., Ma S.H., Kuo C.J., Juan H.F., Cheng Y.S.E., et al. Small molecules targeting severe acute respiratory syndrome human coronavirus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:10012–10017. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403596101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.O'Donnell H.R., Tummino T.A., Bardine C., Craik C.S., Shoichet B.K. Colloidal aggregators in biochemical SARS-CoV-2 repurposing screens. bioRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1101/2021.08.31.458413. Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hu Y., Ma C., Szeto T., Hurst B., Tarbet B., Wang J. Boceprevir, calpain inhibitors II and XII, and GC-376 have broad-spectrum antiviral activity against coronaviruses. ACS Infect Dis. 2021;7:586–597. doi: 10.1021/acsinfecdis.0c00761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hoffmann M., Kleine-Weber H., Schroeder S., Kruger N., Herrler T., Erichsen S., et al. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell. 2020;181:271–280.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chen T., Fei C.Y., Chen Y.P., Sargsyan K., Chang C.P., Yuan H.S., et al. Synergistic inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 replication using disulfiram/ebselen and remdesivir. ACS Pharmacol Transl Sci. 2021;4:898–907. doi: 10.1021/acsptsci.1c00022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sargsyan K., Lin C.C., Chen T., Grauffel C., Chen Y.P., Yang W.Z., et al. Multi-targeting of functional cysteines in multiple conserved SARS-CoV-2 domains by clinically safe Zn-ejectors. Chem Sci. 2020;11:9904–9909. doi: 10.1039/d0sc02646h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Weglarz-Tomczak E., Tomczak J.M., Talma M., Burda-Grabowska M., Giurg M., Brul S. Identification of ebselen and its analogues as potent covalent inhibitors of papain-like protease from SARS-CoV-2. Sci Rep. 2021;11:3640. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-83229-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sun L.Y., Chen C., Su J., Li J.Q., Jiang Z., Gao H., et al. Ebsulfur and ebselen as highly potent scaffolds for the development of potential SARS-CoV-2 antivirals. Bioorg Chem. 2021;112:104889. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2021.104889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Galkin A., Kulakova L., Lim K., Chen C.Z., Zheng W., Turko I.V., et al. Structural basis for inactivation of Giardia lamblia carbamate kinase by disulfiram. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:10502–10509. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.553123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Paranjpe A., Zhang R., Ali-Osman F., Bobustuc G.C., Srivenugopal K.S. Disulfiram is a direct and potent inhibitor of human O6-methylguanine–DNA methyltransferase (MGMT) in brain tumor cells and mouse brain and markedly increases the alkylating DNA damage. Carcinogenesis. 2013;35:692–702. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgt366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lin M.H., Moses D.C., Hsieh C.H., Cheng S.C., Chen Y.H., Sun C.Y., et al. Disulfiram can inhibit MERS and SARS coronavirus papain-like proteases via different modes. Antivir Res. 2018;150:155–163. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2017.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zandi K., Musall K., Oo A., Cao D., Liang B., Hassandarvish P., et al. Baicalein and baicalin inhibit SARS-CoV-2 RNA-dependent-RNA polymerase. Microorganisms. 2021;9:893. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms9050893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhu W., Xu M., Chen C.Z., Guo H., Shen M., Hu X., et al. Identification of SARS-CoV-2 3CL protease inhibitors by a quantitative high-throughput screening. ACS Pharmacol Transl Sci. 2020;3:1008–1016. doi: 10.1021/acsptsci.0c00108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]