Abstract

Psoriasis is a multifactorial immune-mediated disease. The highly effective and eligible treatment for psoriasis is limited, for its specific pathogenesis is incompletely elucidated. Skin microbiota is a research hotspot in the pathogenesis of immune-mediated inflammatory skin diseases nowadays, and it may have significant involvement in the provocation or exacerbation of psoriasis with broadly applicable prospects. It is postulated that skin microbiota alternation may interplay with innate immunity such as antimicrobial peptides and Toll-like receptors to stimulate T-cell populations, resulting in immune cascade responses and ultimately psoriasis. Achieving a thorough understanding of its underlying pathogenesis is crucial. Herein, we discuss the potential immunopathogenesis of psoriasis from the aspect of skin microbiota in an attempt to yield insights for novel therapeutic and preventive modalities for psoriasis.

Keywords: psoriasis, skin microbiota, immunology, pathogenesis, Th17, inflammation

1 Introduction

Psoriasis is a chronic systemic inflammatory disease contributed by genetic, immunological, and environmental factors, with a prevalence rate of 2%–4% of the worldwide population (1). Thus far, psoriasis has no known cure, and innovative biological therapies are of great prospects. Emerging evidence supports the vital role of gut microbiota in psoriasis, and the relevant products such as probiotics have facilitated its treatment improvement, with an encouraging reduction in Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) and lower risk of relapse during follow-up (2, 3). In view of psoriasis being a skin disease, skin microbiota alternation may act more significantly to trigger or exacerbate psoriasis. Current research has put emphasis on the role of skin microbiome in immune-mediated inflammatory skin diseases, including atopic dermatitis, acne vulgaris, vitiligo, and systemic lupus erythematosus (4–8), yet there are certain blank regions in psoriasis. Even though the causal link between skin microbiome and psoriasis remains elusive, evolving knowledge supports its potential role interplaying on T helper cell 17 (Th17) in psoriatic patients, acting on inflammatory cells and cytokine pathways to induce immunity disorder on skin, confirmed by detection of plasma metabolism and bacterial metabolites (9). Furthermore, patients with psoriasis have higher risks of associated comorbidities, such as psoriasis arthritis (PSA), inflammatory bowel disease, periodontitis, cardiometabolic dysfunction, depression, and metabolic syndrome, which may be due to concurrent susceptible locus and aberrant impaired tolerance in response to microbiota (10–14). With the update of whole-genome shotgun (WGS) metagenomic sequencing (15), the assessment accuracy of bacterial species, community diversity, and gene prediction has been greatly optimized in trials. In the forthcoming period, specific skin microbiome signature might be a promising concept for the diagnostic, therapeutic, and preventive strategies for psoriasis. Novel therapeutic modalities that target or restore the altered skin microbiota are valuable adjuncts for the management of psoriasis and its comorbidities. This article describes the potential pathogenesis of psoriasis concerning how skin microbiota interplay with the host immune system, aiming at providing new insights regarding the immunopathogenesis of psoriasis. A good knowledge about their intrinsic and comprehensive interplay is certainly beneficial to form the basis of innovative treatment selection and may help revolutionize an unprecedented era of biologic therapies for psoriatic patients.

1.1 The Widely Accepted Immunopathogenesis of Psoriasis

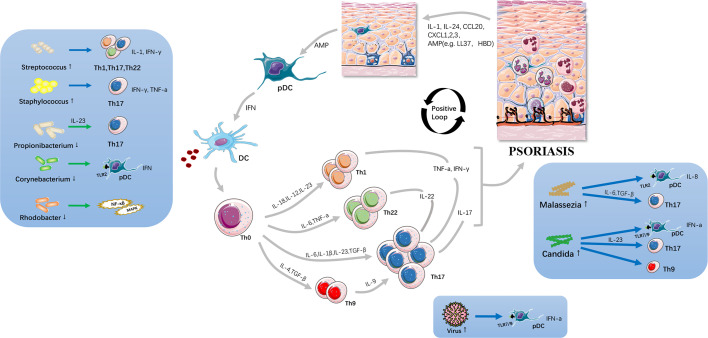

The predominant pathogenesis of psoriasis involves a cross-talk between innate and adaptive immunity through interleukin (IL)-23/Th17 axis and immune responses on resident skin cells (16). It is well recognized that overactive responses of IL-17-producing dermal T cells, namely, Th17 cells, play a significant role in triggering psoriasis (17). Stimulated by antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) such as LL-37 produced by epidermis, dendritic cells (DCs) release IL-12, IL-23, etc., to expand the differentiated Th17 cell populations, in which IL-23 acts significantly (18, 19). Alongside Th1 cells, and Th22 cells, Th17 subsets produce pro-inflammatory mediators such as IL-17A, 17F, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interferon (IFN)-α, and IL-22, leading to hyperproliferation of keratinocytes and immunocyte infiltration on skin to amplify psoriatic inflammation (20, 21). Of note, there is a positive feedback loop that the activated and proliferative keratinocytes subsequently release richer AMPs and cytokines such as IL-1, IL-24, CCL20, and CXCL1–3, serving as chemoattractants to facilitate leukocyte recruitment, angiogenesis, and further keratinocyte proliferation in psoriatic skin (22).

Growing experience has revealed that IL-17 could downregulate filaggrin and genes associated with cellular adhesion to induce skin barrier disruption (23), thereby eliciting a hypoxia environment and the upregulated expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) as part of the pathological basis of psoriasis (24), which is in agreement with the theory that psoriasis could be triggered in the context of reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and a decrease in antioxidant activity (25). On the other hand, markedly higher IL- 9R and IL-9 expression was detected in psoriatic skin lesions. IL-9 would incur micrangium angiogenesis and Th17-associated inflammation by stimulating angiogenic markers (VEGF and CD31) and promote secretion of IL-17, IL-13, IFN-γ, and TNF-α (26). By and large, a psoriasis lesion is provoked by either exogenous skin disruption or endogenous infiltration of activated immunocytes (22). On the basis of preliminary studies indicating the key regulatory function of nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) in TNF production, cell death, immune infiltration, and hyperkeratosis, NF-κB and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathways have been identified to organize psoriatic skin in a Th17-associated manner (27, 28).

1.2 Normal Skin Microbial Community

As the powerful protective barrier, skin is home to diverse immune functions and trillions of microorganisms. Generally, skin microbiota consists of resident and transient flora, along with dynamic characteristics across space and time (29), shouldering their responsibility for host homeostasis on skin principally through effector T cells and DCs (30).

Since microbiota composition is altered in accordance with genetics, site, sampling techniques, etc., there is no uniform standard of healthy skin microbiome. Notwithstanding, 90% of individuals have a “core” commensal microbiome encoding unique products, with remarkable ability to calibrate both innate and adaptive immunity, further completed by Human Microbiome Project (31, 32). On healthy skin, the predominant four phyla are as follows: Actinobacteria (51.8%), Firmicutes (24.4%), Proteobacteria (16.5%), and Bacteroidetes (6.3%); and the three most prevalent genera are Corynebacterium (22.8%; Actinobacteria), Propionibacterium (23.0%; Actinobacteria), and Staphylococcus (16.8%; Firmicutes) (33). With regard to fungi, Malassezia is the predominant flora (34).

1.3 Psoriasis-Associated Microbial Community

Epithelial immune microenvironment regulates the pathogenic inflammatory loop in psoriasis, in which keratinocytes serve as amplifiers and microorganisms as the primary trigger (35). Cutaneous innate immune defenses, including Toll-like receptors (TLRs), pattern recognition receptors, proteoglycan recognition proteins (PGRPs), and antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) have been implicated as potential contributors to psoriasis via Th1/Th17 cell populations in response to cutaneous microbiota (36). TLRs and PGRPs, also called pathogen-recognition receptors (PRRs), are capable of recognizing microbiota and thus altering innate and adaptive immune responses (37). While AMPs, such as LL37, Human β-defensins (HBD), and human S100A7, can not only resist pathogens but also elicit chemotaxis, angiogenesis, and keratinocyte proliferation (22). It has been demonstrated that IL-23 upregulated Human β-defensins (HBD)-2 expression to stimulate keratinocyte proliferation and cytokine production along with Th17 cell expansion, probably involved in the pathogenesis of psoriasis (38).

Ongoing efforts are further completely establishing the pathogenesis of psoriasis and yielding insights for more effective treatment paradigms. Herein, we summarize multiple clinical trials regarding the altered skin microbiota in psoriasis ( Tables 1 – 3 ), shedding light on how skin microbiota influence host innate and adaptive immunity under the inflammatory condition in an effort to unveil the underlying causative association between psoriasis and skin microbiota dysbiosis ( Figure 1 ). As a whole, psoriatic lesions trend to decreased taxonomic and species level diversity in terms of both richness and evenness, whereas with greater intragroup variability. Studies proposed that the altered skin microbiota may promote their translocation into the bloodstream or shed some cell components as inflammagens, thereby driving the systemic inflammation in the host. The commensal skin microbes are reported with weak relevance with disease-related transcripts (50).

Table 1.

Summary of published clinical trials involving skin bacterial microbiota in psoriasis.

| Study | Psoriasis Patients | Healthy Controls | Psoriasis type | Psoriasis severity | Sampling | Method | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Mean or Median Age | Sex ratio (M:F) | Number | Mean or Median Age | Sex ratio (M:F) | |||||

| (9) | 32 | 38.16 (17–74) | – | 29 | 35.53 (23–54) | – | Severe psoriasis (PASI score ≥12) |

PASI: 38.96 ± 2.64 BSA: 24.85 ± 2.82 PGA: 4.41 ± 0.13 |

Swab | 16S rRNA (V3–V4) |

| (39) | 28 | 42.3 ± 14.1 | 11:7 | 26 | 43.6 ± 15.1 | 10:16 | Plaque psoriasis | PASI: 11.1 ± 8.9 | Swab | 16S rRNA (V1–V3) |

| (40) | 8 | – | – | 8 | – | – | – | – | Swab | 16S rRNA |

| (41) | 1 | 50 ± 3 (all subjects) |

1:0 | 1 | 50 ± 3 (all subjects) |

1:0 | – | PASI: 20.0 | Curettage | 16S rRNA (V2–4–8, V3–6,7–9) |

| (42) | 51 | 49.1 ± 16.4 | 39:12 | 37 | – | – | Chronic plaque psoriasis | PASI: 8.7 ± 10.1 BSA: 9.4 ± 13.9 PGA: 6.6 ± 6.9 |

Swab | 16S rRNA (V1–V3) |

| (43) | 10 | 24–60 | 5:5 | 12 | 34–62 | 7:5 | Chronic plaque psoriasis | – | Biopsy | 16S rRNA (V3–V4) |

| (44) | 6 | – | 3:3 | – | – | – | – | BSA: 12 ± 5.7 | Swab | 16S rDNA |

PASI, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index; BSA, Body Surface Area score; PGA, Psoriasis Global Assessment score.

Table 3.

Summary of published clinical trials involving skin fungus microbiota in psoriasis.

| Study | Psoriasis Patients | Healthy Controls | Psoriasis type | Psoriasis severity | Sampling | Method | Diversity | Relative Abundance | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Mean or Median Age | Sex ratio (M: F) | Number | Mean or Median Age | Sex ratio (M: F) | |||||||

| (45) | 12 | 63.8 ± 10.3 (53–78) |

12: 0 | 12 | 59.3 ± 11.6 (55–75) |

– | – | – | Scales collection | 26S rRNA (D1 and D2) |

α: L > H (p < 0.05) |

Filamentous fungi: L > H Malassezia: H > L M. restricta: L > H (p < 0.05) M. globosa: H > L Non-Malassezia yeast: L > H |

| (46) | 6 | 35.8 ± 9.2 (23–50) |

2: 4 | 6 | 42.8 ± 18.9 (27–70) |

3:3 | – | PASI: 7.6 ± 2.6 | Swab | 26S rRNA (D1 and D2) |

– | Malassezia: H > L |

| (47) | 50 | 39 (9–76) |

28: 22 | 50 | – | – | Psoriasis vulgaris Palmoplantar psoriasis Psoriatic erythroderma |

BSA: <3%: 3 subjects 3%–10%: 18 subjects >10%: 29 subjects |

Scotch tape | 26S rRNA | – |

Malassezia: L > U > H (not significant) (Scalp: L > U, p = 0.03) M. japonica: BSA 3%–10% M. globose: BSA 10%–20% M. slooffiae: BSA 10%–20% |

| (48) | 100 | 40.47 ± 11.03 (12–72) | 44: 56 | 50 | 39.90 ± 11.45 (13–63) |

22:28 | Psoriasis vulgaris | – | Swab Biopsy |

26S rRNA (D1 and D2) |

– | Candida: L > U > H |

| (49) | 2 | 33 (F), 58 (M) | 1: 1 | – | – | – | Mild psoriasis | – | Swab | 5.8S rRNA | α: Not significant | Not significant |

| (34) | 3 | 47.7 ± 11.8 (34–55) |

3: 0 | 5 | 35.2 ± 11.3 (21–54) |

2:3 | – | – | Swab | 18S rRNA 5.8S rRNA |

α: Not significant (p = 0.78) | Not significant |

PASI, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index; BSA, Body Surface Area score; PGA, Psoriasis Global Assessment score; L, lesional skin from psoriasis; U, unaffected skin from psoriasis; H, skin from healthy control.

Figure 1.

Potential immunopathogenesis of psoriasis. The altered skin microbiota cause skin barrier disruption and act on innate immune system including Toll-like receptors etc.; and, subsequently drive Th17-associated inflammatory cascades. Large amounts of cytokines are secreted, resulting in immunocyte infiltration, angiogenesis and keratinocyte proliferation thus resulting in initiation and progression of psoriasis. Skin microbiota is viewed as a significant trigger and exacerbator in psoriatic inflammation loop.

1.3.1 Bacteria

Cutaneotype 2, which is enriched for Firmicutes and Actinobacteria, is most prevalent in psoriatic subjects (43, 51). While in the trial of Yerushalmi et al. (37), it displayed a higher relative abundance of Firmicutes and lower relative abundance of Actinobacteria, with decreased alpha diversity, more heterogeneity, and reduced stability ( Tables 1 , 2 ).

Table 2.

Summary of bacterial diversity and taxonomic characteristics on psoriatic skin in clinical trials.

| Study | Diversity | Relative Abundance | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phyla level | Family level | Genus level | Species level | ||

| (9) | α: Not significant | – | – |

Lactobacillus: L > H (p < 0.001) Luteimonas: L > H (p = 0.05) Thermomonas: L>H (p = 0.02) Vibrio: L > H (p < 0.05) |

– |

| (39) | α: L > U > H (p = 0.005) β: Not significant |

Actinobacteria: H > U > L Proteobacteria: L > U > H |

– | Propionibacterium: H > U > L |

Propionibacterium acnes: H > U > L (p = 0.0002) Propionibacterium granulosum: H > U > L (p = 0.014) Staphylococcus sciuri: U > L > H (p = 0.032) Staphylococcus aureus: L > U > H (p = 0.007) Staphylococcus pettenkoferi: L > U > H (p = 0.012) Staphylococcus epidermidis: H > U > L (not significant) |

| (40) | α: H > L (p = 0.04) |

Actinobacteria: H > L (p = 0.0001) Firmicutes: L > H (p = 0.009) |

– |

Alloiococcus: L > H (p = 0.01), U > H (p = 0.003) Aerococcus: L > H (p = 0.01) Propionibacterium: H > L (p = 0.08) Gallicola: L > H (p = 0.09), L > U (p = 0.04) |

Acinetobacter spp.: L ≈ U > H Staphylococcus pettenkoferi: L ≈ U > H Streptococcus spp.: L ≈ U > H |

| (41) | – |

Firmicutes: H > L Proteobacteria: L > H |

Streptococcaceae: L > H Rhodobacteraceae: L > H Campylobacteraceae: L > H Staphylococcaceae: H > L Propionibacteriaceae: H > L |

Paracoccus: L > H |

Propionibacterium acnes: H > L Staphylococcus aureus: H > L (p < 0.05) |

| (42) | α: H > U > L (p < 0.05) β: L > U > H (p < 0.05) |

Proteobacteria: H > U > L | – |

Streptococcus: L > U > H Staphylococcus: L > U > H |

– |

| (43) | α: H > L (not significant) β: H > L |

Firmicutes: H > L Proteobacteria: L > H (trunk p = 0.0113) Actinobacteria: H > L (p = 0.034) |

– |

Streptococcus: L > H Staphylococcus: H > L Propionibacteria: H > L (p = 0.061) |

– |

| (44) | α: L > U >H (p < 0.001) |

Firmicutes: L > U > H (p < 0.001) Actinobacteria: H > U > L (p < 0.01) Proteobacteria: H > L ≈ U (p < 0.001) |

– |

Streptococcus: L > U > H (p<0.001) Propionibacterium: H > U > L (p < 0.001) |

Propionibacterium acnes: H > U > L (p < 0.001) Staphylococcus aureus: H > U (p < 0.001) |

L, lesional skin from psoriasis; U, unaffected skin from psoriasis; H, skin from healthy control.

1.3.1.1 Streptococcus

At the genus level, Streptococcus is the most common flora identified in psoriatic skin. Some people developed psoriasis outbreaks following Streptococcus infection. Evidence indicates that throat and nasal streptococcal infection, especially beta-hemolytic Streptococcus pyogenes, is responsible for guttate psoriasis (GP) and chronic plaque psoriasis (CPP). Tonsillectomy is proven to be a feasible strategy for Streptococcus-associated psoriasis, owing to a high frequency of cutaneous lymphocyte-associated antigen (CLA) + tonsil T cells that preferentially express IL-23 receptors, and these cells are postulated to be correlated with Th17, Th22, or Th1 polarization.

Superantigens are powerful T lymphocyte-stimulating agents. Streptococcal peptidoglycan (PG) has been implicated to function as superantigens, binding to class II major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules and Vβ segments of the T-cell receptor to initiate pathological responses and cytokine release in an antigen-specific manner (52). Similarly, streptococcal M proteins and pyrogenic exotoxin A, B, C also act as superantigens, binding directly to HLA-DR molecules on DCs, macrophages, and keratinocytes and activating T-lymphocyte subpopulations that express specific inflammation-associated Vβ families. It has been testified that selective aggregation of Vβ2+ T cells (p < 0.05) can be found in skin biopsies from all patients with GP lesions (53).

After recognizing IL-12 and superantigens that resemble M protein and keratin homologous peptides, CLA+ T cells could migrate to skin and subsequently react with streptococcal epitopes or skin-specific epitopes via molecular mimicry, resulting in psoriatic inflammation. In addition, CLA+ T cells are detected with decreased levels as psoriasis is ameliorated (54).

A preliminary study has demonstrated that dermal Th1 cell populations in GP and CPP lesions can selectively recognize lower MWt proteins (approximately 20–100 kDa) extracted from group A streptococci (GAS) cell wall, thereby increasingly producing IFN-γ in a self-HLA-DR allele-restricted manner. However, the contents of MWt proteins warrant further research to identify, implying that large proportions of Th1 cells specifically target streptococcal PG to initiate or exacerbate psoriatic inflammation (55). To sum up, psoriatic dermal streptococcal-specific CD4+ T-cell lines proliferate and release IFN-γ, IL-1, etc., in response to streptococcal PG (56). The theory of superantigen-activating T cells provides an explanation for 70% of GP patients who develop CPP (51).

1.3.1.2 Staphylococcus

A majority of studies have manifested elevated levels of Staphylococcus on skin of psoriatic subjects. According to a meta-analysis involving 21 eligible studies, the presence of Staphylococcus aureus colonization in psoriatic patients is approximately 4.5 times higher than that of healthy controls (57). In the trial of Balci et al. (58), S. aureus was cultivated from lesional skin in approximately 64% of psoriatic patients, significantly higher than about 30% from non-lesional and healthy control samples, and 60% of patients were detected with Staphylococcus enterotoxins (se) and toxic shock syndrome toxin-1 (TSST-1). Genes encoding sea, seb, sec, sed, Panton–Valentine leukocidin (PVL), exfoliative toxin b (etb), TSST-1, and their carried accessory gene regulatory (agr) locus that regulates protease secretion and promotes S. aureus aggregation to the skin probably act as superantigen for psoriatic attack (59). Keratinocyte expression of HLA-DR that indirectly acting as a mediator binds superantigens, along with its secreted TNF concurrently trigger inflammatory cascades. In the murine experiment performed by Chang et al. (39), strong Th17 polarization was detected in mice colonized with S. aureus while absent in those with Staphylococcus epidermidis or un-colonized controls. Moreover, high PASI scores are significantly correlated with toxin-positive S. aureus colonization (58, 60). Similar to Streptococcus, staphylococcal PG could also be recognized by psoriatic T-cell lines through IFN-γ (56).

Paradoxically, in the trial of Elfatoiki et al. (61), S. aureus colonization was significantly lower in the lesional psoriatic skin than in controls (3% vs. 27.3%) and indicated that Staphylococcus may not be indispensable in provoking psoriasis.

1.3.1.3 Other Bacterial Communities

Consistent with most clinical trials, Yan et al. (62) reported a decreased level of Propionibacterium in psoriasis lesions compared to controls. Propionibacterium can produce propionate and radical oxygenase (RoxP) that reduce oxidative stress and prevent skin inflammation (59). And its immunomodulatory constituents could protect skin barrier against external aggression (44). Hence, the underrepresentation of Propionibacterium may confer incapability to regulate the balance in the oxidant–antioxidant system, resulting in a disordered redox homeostasis. Moreover, Propionibacterium acnes strains have been demonstrated to differentially modulate Th17 cells of varied phenotypes in the presence of IL-2 and IL-23 to maintain homeostasis (63).

Corynebacterium is displayed with decreased abundance in trials. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) may have a direct pathological role through IFN production in psoriasis (64). It is speculated that Corynebacterium possesses an anti-inflammatory capability for negatively regulating “interferon signaling,” thus, its reduction causes a higher propensity to develop psoriasis onset or exacerbation (50).

With preclinical reports indicating that Rhodobacter has the anti-inflammatory capability to produce lycogen to prevent procollagen downregulation and inhibit NF-κB pathway, its decreased abundance is speculated to influence skin barrier and be involved in the pathogenesis of psoriasis (41).

1.3.2 Fungus

Antifungal agents have yielded great efficacy in scalp psoriasis, suggesting the potential role of skin fungus in provocation or deterioration of psoriasis. Imiquimod (IMQ), a TLR7 agonist, has been applied to promote psoriasis-like skin inflammation via the IL-23/IL-17 axis in murine experiments (65). Hurabielle et al. (66) compared two experimental psoriatic models respectively associated with fungus/IMQ (Candida albicans, Malassezia furfur, and Trichophyton mentagrophytes) and IMQ alone, with the findings suggesting that fungal preexposure could significantly allow a better psoriatic model, depending on Th17 responses and neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) ( Table 3 ).

1.3.2.1 Malassezia

Patch testing with inactivated Malassezia has been demonstrated to be capable of inducing clinically and histologically psoriasis-like lesions (67). Malassezia produces lipases and phospholipases that impair epidermal barrier, chemoattractants for polymorphonuclear leukocytes, as well as cross-reactive allergens leading to sensitization. In the study of Rudramurthy et al. (47), M. furfur is the predominant species (70.6%). Malassezia yeasts could do damage to the skin and stress predisposed keratinocytes then secondarily amplify AMPs. On the other hand, the study of Baroni et al. (68) showed a TLR2-dependence of IL-8 and HBD-2 in M. furfur-treated keratinocytes. Additionally, TLR2 can pair with TLR1 or TLR6, thus leading to large amounts of cytokine induction and ultimately chronic systemic inflammation in psoriasis (68).

Higher serum levels of IgG and significantly lower IgA against M. furfur were reported in patients developing psoriasis vulgaris. Antibodies to some constituents of Malassezia are also found in psoriatic lesions. It is also suggested that M. furfur can upregulate the expression of transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1, integrin, and heat shock protein 70 (HSP70) in an AP-1-dependent manner in human keratinocytes, thereby modulating cell cycle acceleration and favoring the exacerbation of psoriasis (69).

Previous studies showed that M. furfur could invade skin barrier and modulate immunomodulatory cytokine synthesis by downregulating IL-1α and by inhibiting IL-6 and TNF-α and by upregulating IL-10 and TGF-β1, thereby enhancing inflammatory responses (70).

1.3.2.2 Candida

A meta-analysis revealed that Candida possesses significantly higher detection rates on mucosal membranes in psoriasis compared with controls (71). Another evaluation manifested that Candida could be isolated from 15% of psoriatic patients while 4% in controls. The serum IgM, IgG, and IgA against C. albicans were also prominently less in patients (p < 0.05), whereas no definite evidence has demonstrated the association between serum antibodies and its colonization with PASI (p > 0.05) (48). Whereas recent study holds that Candida colonization is positively associated with PASI (72).

In a murine experiment, neutrophil infiltration is notably observed in groups with preexposure to C. albicans. It is proposed that driven by candidal colonization, polarized IL-17-producing T cells including Th17, Tc17, and γδ T cells accumulate to concurrently promote IMQ pathology and exacerbate psoriasis-like skin inflammation in a dectin-1/Langerhans cell-dependent manner (66). In response to the skin barrier disruption, LCs recognize C. albicans yeasts through the C-type lectin receptor (CLR) dectin-1 and induce Th17 immune responses in the context of IL-6 (69, 70). C. albicans would stimulate nociceptors and could induce the neuropeptide calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) via CLR dectin-1, and as a result drive dermal DCs and T cells to produce IL-23 and IL-17, which may lead to the occurrence of psoriasis (73, 74). The study found that in mice deficient in LCs, C. albicans is incapable of promoting neutrophil recruitment and IMQ-induced Th17 cell accumulation. Similarly, in mice deficient in dectin-1 or the gene encoding its downstream adaptor molecule CARD9, enhanced inflammation associated with preexposure to C. albicans was also abolished. Therefore, a Langerhans cell/dectin-1 axis plays a central role for the activated Th17 pathway in C. albicans/IMQ-treated mice (66).

It is also acknowledged that C. albicans-associated experimental psoriasis is characterized by enhanced neutrophil response and NET-mediated pathology. NET, the aberrant neutrophil activation/death, could be triggered by skin microorganisms through various downstream effector proteins (75). In the absence of NETosis inhibitor, psoriatic symptoms are exacerbated (76). NETs activate pDC accumulation to sense microbial DNA via TLR9 and TLR7 signaling, thus promoting type I IFN expression and may constitute a fundamental trigger of autoimmune pathology (77); in this process, LL-37 also potentiates TLR9 activation (78). In the clinical trial conducted by Hu et al. (79), NET parameters were positively correlated with PASI.

Nakajima et al. (80) also found that in murine models, C. albicans topical association significantly enhanced skin inflammation via promoting IL-17A production from CD4+ effector T cells in the skin and lymph nodes. It is also indicated that the surface proteins of C. albicans may act like superantigens and trigger Th17 activation through pro-inflammatory cytokines especially IL-23, which are essential for host defense against C. albicans. Additionally, IL-17 recruits neutrophils to resist Candida through direct phagocytosis, NET formation, and a substantial number of AMPs (81). Th9 cell populations, which produce large amounts of IL-9, increase in psoriatic skin lesions and connect the innate and adaptive immune system against C. albicans infection (82). In C. albicans/IMQ-treated samples, functional analysis manifested more significant enrichment for cytokine–cytokine receptor interaction along with positively regulatory genes associated with MAPK cascade, which could be seen enriched in human psoriasis as well.

1.3.3 Virus

The role of virus in psoriasis is more obscure. PDCs infiltrate inflammatory psoriatic skin and produce large amounts of IFN-α on viral stimulation via TLR-7 and TLR-9, subsequently triggering T-cell cascade to potentiate Th1 cell bias and initiate psoriasis (20).

Previous cohort studies have revealed that people obtaining human papillomavirus (HPV) infection exhibited a 1.177 times greater risk of subsequently developing psoriasis particularly inverse psoriasis than did those in the healthy population, in which age acted as a prominent modifier (83). In the trial of Favre et al. HPV DNA was detected in 91.7% of 48 psoriatic skin samples. HPV5, HPV36, and HPV1 were 89.4%, 84.2%, and 42.1%, respectively, disclosing that psoriasis may be a reservoir for HPV5 (84). Simeone et al. (85) performed a clinical trial on 11 psoriatic patients, with the results showing the presence of HPV5 in 64% psoriatic keratinocytes, and concluded that viral replication in the psoriatic keratinocytes may trigger epidermal hyperproliferation along with antigen stimulation and lead to an autoimmune cascade. In hairs of psoriatic patients, the most prevalent HPV type in all tested samples was HPV-38, followed by HPV-25 (86).

With regard to psoriatic patients infected with hepatitis C virus (HCV), Chun et al. (81) found significantly higher LL37, TLR9, and IFN-y expression in lesional skin. It has been proposed that the cutaneous load of HCV infection is positively associated with PASI via detecting HCV protein and RNA expression in serum (82, 87).

For another, Teng et al. (88) proposed that the inverted CD4+/CD8+ ratio could induce keratinocytes aberrantly to express HLA-DR through IFN-γproduction in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-associated psoriasis.

1.3.4 Other Microorganisms

In addition to the aforementioned skin microbiota, evolving knowledge indicates that there is still a wide range of microorganisms predisposing patients to developing psoriasis, such as Helicobacter pylori, Porphyromonas gingivalis, Chlamydiae, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), which presumably function as superantigens to initiate T-cell responses (89).

2 Discussion

Given the concern that the efficacy of off-the-shelf treatment products for psoriasis is limited hitherto, fully understanding the pathogenesis of psoriasis remains a priority for future research. Microbiome research is very prevalent at present. Whether the skin dysbiosis consists in the primary etiological significance or is secondary to psoriasis (or both) has yet to be completely characterized. Moreover, no consensus microorganisms have been directly identified. The generally accepted viewpoint holds that the altered microbiota probably serves potentially as a trigger or exacerbator for psoriasis. This review summarizes the outcome of multiple preceding clinical trials relevant to the altered skin microbiome in psoriatic patients, with a primary focus on mechanisms underlying how they interplay with the host immune system.

The field of the psoriatic skin microbiome is relatively new, and there are few studies on the specific and novel therapies targeting skin microbiome, thus leaving us considerable room to excavate. The manipulation of skin microbiome for treatment efficacy that preliminary research mentioned mostly refers to the conventional therapeutic options such as topical or systemic antibiotics that reduce susceptible bacterial species. Additionally, narrow-band ultraviolet radiation (NB-UVB) and balneotherapy have been demonstrated to induce an alteration of lesional skin microbiota and the improvement of psoriatic progression (90, 91). On the other hand, there is a direct link between gut and skin microbiota (92). Human skin microbiome composition can also be modulated through manipulated therapy of the gut microbiome (93). Researchers hold that probiotics may exert immunomodulatory effects on skin and can strengthen its barrier function against hazardous flora (94). Navarro-López et al. (95) had performed probiotic therapy on 80 psoriatic patients, with PASI75 reaching 66.7% and lower risk of relapse during follow-up compared to placebo group. Moreover, skin microbiome transplantation to diseased skin has yet to be regarded as another possible approach (96). Given the aforementioned encouraging efficacy on blocking disease progression, it is expected that more skin microbiome-related intervention to alleviate or cure this dermatosis would be developed in future research. For example, transdermal drug delivery must produce a milder side effect profile than current systemic medications. Besides, complement therapeutics are under investigation to potentially modulate the skin microbiota and even treat psoriasis (97).

Unlike atopic dermatitis, it is more than likely that the potential pathogens of psoriasis involve multiple species. Much about the potential role of viruses in psoriatic inflammation remains unclear. In future research, the upmost challenge might be to identify the extent to which skin microbiome plays a role in psoriatic pathogenesis and be modulated, and we should also identify one or several microbes that exert predominant influence on psoriasis, therefore enhancing the accuracy of modulation. Nevertheless, the heterogeneous parameters including genetics, diet, treatment exclusion, and taxonomic levels probably render the results reported in clinical trials less authentic and comparable. Furthermore, even in a single specific trial, the site- and microenvironment-based matching between lesion and control samples might be absent. As discussed, the preliminary studies only elaborate the correlative relationship between skin microbiome and psoriatic state as a whole. In the forthcoming decades, further experimentation to validate their definite association, and performed on isolated microbes, presents a principal direction. For one thing, a new set of standardized analysis protocol, including study population, sampling and processing methodology, would be a useful first step to interpret microbiome data. For instance, healthy people who have a common living background with psoriatic patients ought to be enrolled in a control group to reduce the bias. For another, in terms of taxonomic levels, it is critical to apply strain-level rather than species-level resolution approaches to unravel the microbial signatures associated with psoriasis; particularly, there are still vast unprofiled and undetermined regions about cutaneous viruses. It is proposed that gene transcriptomics is a suitable predictor of disease severity. Nevertheless, there is another tough problem regarding whether the sequence reads in skin swabs could map to specific functional genomes, thus making microorganisms classifiable (98). It still remains difficult to identify the specific driven genes. A substantial number of large-scale prospective longitudinal clinical trials and proof-of-concept experiments in murine models are also required to trace the dynamics of microbial populations during the onset and progression of psoriasis, which may give some enlightenment to predictive approaches for therapeutic responses through particular transcriptomic and microbial biomarkers with disease severity.

Notably, it is hypothesized that skin microbiome composition is associated with the development of psoriatic comorbidities. Initial studies show that its reduced diversity, which may weaken the skin protective function to trigger an immune response, might be a signature for psoriatic patients with a higher risk to develop PSA. It also showed that antibiotics have the potential to reduce the risk of comorbidities in psoriatic patients (96, 99). Whether the skin microbiota is involved in its comorbidity association remains to be further explored. It is expected to develop preventative measures to intervene to halt the progression of PSA.

Taken together, endeavors should be made in seeking out the deeper association between skin microbiome and developing microbiota-related interventions to mitigate psoriasis, such as selective modulation of isolated microbiota via intraindividual or interindividual skin microbiota transplantation, facilitating gut–skin cross-talk via prebiotics, and manipulating microbial pathways by targeting microbial metabolites through pharmacologic inhibitors, and hence, eventually improving clinical outcomes of psoriatic patients. In addition, the characteristics of chronic inflammation, along with its relevant metabolic comorbidity, concurrently indicate the significance of metabolomics in psoriasis. The extent to which skin microbiota play a role in the pathogenesis in psoriasis and which it can be modulated is certainly a critical consideration, and the potential function of skin microbiota on regulating global metabolism in psoriasis is a promising field. Hopefully, microbiome-specific targeted treatments or even curative paradigms for this dermatosis will come true in the upcoming period.

3 Conclusion

Psoriasis is mediated by immunological and external factors as a commonly seen chronic dermatosis in the population. Given the previous findings, the existing immunopathogenesis for psoriatic inflammation mainly involves IL-23/Th17 axis, along with large amounts of cytokines and immunocytes. Also, skin microbiota could regulate the cutaneous immune tolerance. In psoriatic skin, it is observed that the microorganism composition has altered, which interplays with host innate and adaptive immunity and potentially constitutes the pathogenesis of psoriasis. Some treatments regarding modifying the skin microbiome have been manifested to yield certain efficacy in psoriasis, whereas this field is relatively new and there is a series of challenges existing in future research. It is expected that this potential pathogenesis could be verified and that novel therapeutics targeting the skin microbiome could be figured out to improve the clinical outcome of psoriatic patients.

Author Contributions

This study was conceived and designed by YC. Screening of papers and data extraction were performed by XL and CO. Writing of the first draft of the article was performed by XL, CO, JZ, and JL. Tables and figure were prepared by XL, CO, FZ, and YZ. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- 1. Parisi R, Symmons DP, Griffiths CE, Ashcroft DM, Identification, Management of P et al. Global Epidemiology of Psoriasis: A Systematic Review of Incidence and Prevalence. J Invest Dermatol (2013) 133(2):377–85. doi: 10.1038/jid.2012.339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Polak K, Bergler-Czop B, Szczepanek M, Wojciechowska K, Fratczak A, Kiss N. Psoriasis and Gut Microbiome-Current State of Art. Int J Mol Sci (2021) 22(9):4529. doi: 10.3390/ijms22094529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Navarro-Lopez V, Nunez-Delegido E, Ruzafa-Costas B, Sanchez-Pellicer P, Aguera-Santos J, Navarro-Moratalla L. Probiotics in the Therapeutic Arsenal of Dermatologists. Microorganisms (2021) 9(7):1513. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms9071513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Catinean A, Neag MA, Mitre AO, Bocsan CI, Buzoianu AD. Microbiota and Immune-Mediated Skin Diseases-an Overview. Microorganisms (2019) 7(9):279. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms7090279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Edslev SM, Agner T, Andersen PS. Skin Microbiome in Atopic Dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol (2020) 100(12):adv00164. doi: 10.2340/00015555-3514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Li CX, You ZX, Lin YX, Liu HY, Su J. Skin Microbiome Differences Relate to the Grade of Acne Vulgaris. J Dermatol (2019) 46(9):787–90. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.14952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ganju P, Nagpal S, Mohammed MH, Nishal Kumar P, Pandey R, Natarajan VT, et al. Microbial Community Profiling Shows Dysbiosis in the Lesional Skin of Vitiligo Subjects. Sci Rep (2016) 6:18761. doi: 10.1038/srep18761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Huang C, Yi X, Long H, Zhang G, Wu H, Zhao M, et al. Disordered Cutaneous Microbiota in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. J Autoimmun (2020) 108:102391. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2019.102391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chen D, He J, Li J, Zou Q, Si J, Guo Y, et al. Microbiome and Metabolome Analyses Reveal Novel Interplay Between the Skin Microbiota and Plasma Metabolites in Psoriasis. Front Microbiol (2021) 12:643449. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.643449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Eppinga H, Konstantinov SR, Peppelenbosch MP, Thio HB. The Microbiome and Psoriatic Arthritis. Curr Rheumatol Rep (2014) 16(3):407. doi: 10.1007/s11926-013-0407-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Olejniczak-Staruch I, Ciazynska M, Sobolewska-Sztychny D, Narbutt J, Skibinska M, Lesiak A. Alterations of the Skin and Gut Microbiome in Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis. Int J Mol Sci (2021) 22(8):3998. doi: 10.3390/ijms22083998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Vlachos C, Gaitanis G, Katsanos KH, Christodoulou DK, Tsianos E, Bassukas ID. Psoriasis and Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Links and Risks. Psoriasis (Auckl) (2016) 6:73–92. doi: 10.2147/PTT.S85194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bunte K, Beikler T. Th17 Cells and the IL-23/IL-17 Axis in the Pathogenesis of Periodontitis and Immune-Mediated Inflammatory Diseases. Int J Mol Sci (2019) 20(14):3394. doi: 10.3390/ijms20143394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Xiao S, Zhang G, Jiang C, Liu X, Wang X, Li Y, et al. Deciphering Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis and Corresponding Genetic and Metabolic Dysregulation in Psoriasis Patients Using Metagenomics Sequencing. Front Cell Infect Microbiol (2021) 11:605825. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2021.605825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ranjan R, Rani A, Metwally A, McGee HS, Perkins DL. Analysis of the Microbiome: Advantages of Whole Genome Shotgun Versus 16S Amplicon Sequencing. Biochem Biophys Res Commun (2016) 469(4):967–77. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.12.083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Boehncke W-H, Schön MP. Psoriasis. Lancet (2015) 386(9997):983–94. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(14)61909-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cai Y, Fleming C, Yan J. New Insights of T Cells in the Pathogenesis of Psoriasis. Cell Mol Immunol (2012) 9(4):302–9. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2012.15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Girolomoni G, Strohal R, Puig L, Bachelez H, Barker J, Boehncke WH, et al. The Role of IL-23 and the IL-23/TH17 Immune Axis in the Pathogenesis and Treatment of Psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol (2017) 31(10):1616–26. doi: 10.1111/jdv.14433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bettelli E, Oukka M, Kuchroo VK. T(H)-17 Cells in the Circle of Immunity and Autoimmunity. Nat Immunol (2007) 8(4):345–50. doi: 10.1038/ni0407-345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nestle FO, Conrad C, Tun-Kyi A, Homey B, Gombert M, Boyman O, et al. Plasmacytoid Predendritic Cells Initiate Psoriasis Through Interferon-Alpha Production. J Exp Med (2005) 202(1):135–43. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lowes MA, Suárez-Fariñas M, Krueger JG. Immunology of Psoriasis. Annu Rev Immunol (2014) 32(1):227–55. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032713-120225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Buchau AS, Gallo RL. Innate Immunity and Antimicrobial Defense Systems in Psoriasis. Clin Dermatol (2007) 25(6):616–24. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2007.08.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gutowska-Owsiak D, Schaupp AL, Salimi M, Selvakumar TA, McPherson T, Taylor S, et al. IL-17 Downregulates Filaggrin and Affects Keratinocyte Expression of Genes Associated With Cellular Adhesion. Exp Dermatol (2012) 21(2):104–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2011.01412.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Elias PM, Arbiser J, Brown BE, Rossiter H, Man M-Q, Cerimele F, et al. Epidermal Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Production is Required for Permeability Barrier Homeostasis, Dermal Angiogenesis, and the Development of Epidermal Hyperplasia. Am J Pathol (2008) 173(3):689–99. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.080088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Okayama Y. Oxidative Stress in Allergic and Inflammatory Skin Diseases. Curr Drug Targets Inflammation Allergy (2005) 4(4):517–9. doi: 10.2174/1568010054526386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Singh TP, Schon MP, Wallbrecht K, Gruber-Wackernagel A, Wang XJ, Wolf P. Involvement of IL-9 in Th17-Associated Inflammation and Angiogenesis of Psoriasis. PloS One (2013) 8(1):e51752. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Matsumoto R, Dainichi T, Tsuchiya S, Nomura T, Kitoh A, Hayden MS, et al. Epithelial TRAF6 Drives IL-17–Mediated Psoriatic Inflammation. JCI Insight (2018) 3(15):e121175. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.121175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Grinberg-Bleyer Y, Dainichi T, Oh H, Heise N, Klein U, Schmid RM, et al. Cutting Edge: Nf-κb P65 and C-Rel Control Epidermal Development and Immune Homeostasis in the Skin. J Immunol (2015) 194(6):2472–6. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1402608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Costello EK, Lauber CL, Hamady M, Fierer N, Gordon JI, Knight R. Bacterial Community Variation in Human Body Habitats Across Space and Time. Science (2009) 326(5960):1694–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1177486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Naik S, Bouladoux N, Linehan JL, Han SJ, Harrison OJ, Wilhelm C, et al. Commensal-Dendritic-Cell Interaction Specifies a Unique Protective Skin Immune Signature. Nature (2015) 520(7545):104–8. doi: 10.1038/nature14052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Integrative HMPRNC . The Integrative Human Microbiome Project. Nature (2019) 569(7758):641–8. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1238-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ahmed N, Huse SM, Ye Y, Zhou Y, Fodor AA. A Core Human Microbiome as Viewed Through 16S rRNA Sequence Clusters. PloS One (2012) 7(6):e34242. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Grice EA, Kong HH, Conlan S, Deming CB, Davis J, Young AC, et al. Topographical and Temporal Diversity of the Human Skin Microbiome. Science (2009) 324(5931):1190–2. doi: 10.1126/science.1171700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Paulino LC, Tseng CH, Strober BE, Blaser MJ. Molecular Analysis of Fungal Microbiota in Samples From Healthy Human Skin and Psoriatic Lesions. J Clin Microbiol (2006) 44(8):2933–41. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00785-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Dainichi T, Kitoh A, Otsuka A, Nakajima S, Nomura T, Kaplan DH, et al. The Epithelial Immune Microenvironment (EIME) in Atopic Dermatitis and Psoriasis. Nat Immunol (2018) 19(12):1286–98. doi: 10.1038/s41590-018-0256-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Langan EA, Griffiths CEM, Solbach W, Knobloch JK, Zillikens D, Thaci D. The Role of the Microbiome in Psoriasis: Moving From Disease Description to Treatment Selection? Br J Dermatol (2018) 178(5):1020–7. doi: 10.1111/bjd.16081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Yerushalmi M, Elalouf O, Anderson M, Chandran V. The Skin Microbiome in Psoriatic Disease: A Systematic Review and Critical Appraisal. J Trans Autoimmun (2019) 2:100009. doi: 10.1016/j.jtauto.2019.100009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Fry L, Baker BS, Powles AV, Fahlen A, Engstrand L. Is Chronic Plaque Psoriasis Triggered by Microbiota in the Skin? Br J Dermatol (2013) 169(1):47–52. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Chang H-W, Yan D, Singh R, Liu J, Lu X, Ucmak D, et al. Alteration of the Cutaneous Microbiome in Psoriasis and Potential Role in Th17 Polarization. Microbiome (2018) 6(1):154. doi: 10.1186/s40168-018-0533-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Yan D, Chang H, Singh R, Lai K, Afifi L, Lu X, et al. 633 Role of the Cutaneous Microbiome in the Pathogenesis of Psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol (2017) 137(5):S109. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2017.02.655 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Drago L, De Grandi R, Altomare G, Pigatto P, Rossi O, Toscano M. Skin Microbiota of First Cousins Affected by Psoriasis and Atopic Dermatitis. Clin Mol Allergy (2016) 14(1):2. doi: 10.1186/s12948-016-0038-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Alekseyenko AV, Perez-Perez GI, De Souza A, Strober B, Gao Z, Bihan M, et al. Community Differentiation of the Cutaneous Microbiota in Psoriasis. Microbiome (2013) 1(1):31. doi: 10.1186/2049-2618-1-31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Fahlén A, Engstrand L, Baker BS, Powles A, Fry L. Comparison of Bacterial Microbiota in Skin Biopsies From Normal and Psoriatic Skin. Arch Dermatol Res (2011) 304(1):15–22. doi: 10.1007/s00403-011-1189-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Gao Z, Tseng CH, Strober BE, Pei Z, Blaser MJ. Substantial Alterations of the Cutaneous Bacterial Biota in Psoriatic Lesions. PloS One (2008) 3(7):e2719. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Takemoto A, Cho O, Morohoshi Y, Sugita T, Muto M. Molecular Characterization of the Skin Fungal Microbiome in Patients With Psoriasis. J Dermatol (2015) 42(2):166–70. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.12739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Jagielski T, Rup E, Ziółkowska A, Roeske K, Macura AB, Bielecki J. Distribution of Malassezia Species on the Skin of Patients With Atopic Dermatitis, Psoriasis, and Healthy Volunteers Assessed by Conventional and Molecular Identification Methods. BMC Dermatol (2014) 14(3):3. doi: 10.1186/1471-5945-14-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Rudramurthy SM, Honnavar P, Chakrabarti A, Dogra S, Singh P, Handa S. Association Ofmalasseziaspecies With Psoriatic Lesions. Mycoses (2014) 57(8):483–8. doi: 10.1111/myc.12186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Taheri Sarvtin M, Shokohi T, Hajheydari Z, Yazdani J, Hedayati MT. Evaluation of Candidal Colonization and Specific Humoral Responses Against Candida Albicans in Patients With Psoriasis. Int J Dermatol (2014) 53(12):e555–e60. doi: 10.1111/ijd.12562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Paulino LC, Chi-Hong T, Blaser MJ. Analysis of Malassezia Microbiota in Healthy Superficial Human Skin and in Psoriatic Lesions by Multiplex Real-Time Pcr. FEMS Yeast Res (2010) 3):460–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2008.00359.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Fyhrquist N, Muirhead G, Prast-Nielsen S, Jeanmougin M, Olah P, Skoog T, et al. Microbe-Host Interplay in Atopic Dermatitis and Psoriasis. Nat Commun (2019) 10(1):4703. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-12253-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Macias ES, Pereira FA, Rietkerk W, Safai B. Superantigens in Dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol (2011) 64(3):455–72; quiz 73-4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.03.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Leung D, Travers JB, Giorno R, Norris DA, Kotb M. Evidence for a Streptococcal Superantigen-Driven Process in Acute Guttate Psoriasis. J Clin Invest (1995) 99(5):2106. doi: 10.1172/JCI118263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. El Ferezli J, Jenbazian L, Rubeiz N, Kibbi A-G, Zaynoun S, Abdelnoor AM. Streptococcussp. Andstaphylococcus Aureusisolates From Patients With Psoriasis Possess Genes That Code for Toxins (Superantigens): Clinical and Therapeutic Implications. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicology (2008) 30(2):195–205. doi: 10.1080/08923970801946808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Sigurdardottir SL, Thorleifsdottir RH, Valdimarsson H, Johnston A. The Association of Sore Throat and Psoriasis Might be Explained by Histologically Distinctive Tonsils and Increased Expression of Skin-Homing Molecules by Tonsil T Cells. Clin Exp Immunol (2013) 174(1):139–51. doi: 10.1111/cei.12153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. GÖÇMen JS, ŞAhİNer N, KoÇAk M, Karahan ZC. PCR Investigation of Panton-Valentine Leukocidin, Enterotoxin, Exfoliative Toxin,and Agr Genes in Staphylococcus Aureus Strains Isolated From Psoriasis Patients*. Turkish J Med Sci (2015) 45:1345–52. doi: 10.3906/sag-1408-54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Baker BS, Laman JD, Powles A, van der Fits L, Voerman JSA, Melief MJ, et al. Peptidoglycan and Peptidoglycan-Specific Th1 Cells in Psoriatic Skin Lesions. J Pathol (2006) 209(2):174–81. doi: 10.1002/path.1954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Ng CY, Huang YH, Chu CF, Wu TC, Liu SH. Risks for Staphylococcus Aureus Colonization in Patients With Psoriasis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Br J Dermatol (2017) 177(4):967–77. doi: 10.1111/bjd.15366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Balci DD, Duran N, Ozer B, Gunesacar R, Onlen Y, Yenin JZ. High Prevalence of Staphylococcus Aureus Cultivation and Superantigen Production in Patients With Psoriasis. Eur J Dermatol (2009) 19(3):238–42. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2009.0663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Allhorn M, Arve S, Brüggemann H, Lood R. A Novel Enzyme With Antioxidant Capacity Produced by the Ubiquitous Skin Colonizer Propionibacterium Acnes. Sci Rep (2016) 6(1):36412. doi: 10.1038/srep36412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Tomi NS, Kranke B, Aberer E. Staphylococcal Toxins in Patients With Psoriasis, Atopic Dermatitis, and Erythroderma, and in Healthy Control Subjects. J Am Acad Dermatol (2005) 53(1):67–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.02.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Elfatoiki FZ, El Azhari M, El Kettani A, Serhier Z, Othmani MB, Timinouni M, et al. Psoriasis and Staphylococcus Aureus Skin Colonization in Moroccan Patients. Pan Afr Med J (2016) 23:33. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2016.23.33.7198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Yan D, Issa N, Afifi L, Jeon C, Chang HW, Liao W. The Role of the Skin and Gut Microbiome in Psoriatic Disease. Curr Dermatol Rep (2017) 6(2):94–103. doi: 10.1007/s13671-017-0178-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Agak GW, Kao S, Ouyang K, Qin M, Moon D, Butt A, et al. Phenotype and Antimicrobial Activity of Th17 Cells Induced by Propionibacterium Acnes Strains Associated With Healthy and Acne Skin. J Invest Dermatol (2018) 138(2):316–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2017.07.842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Reizis B, Colonna M, Trinchieri G, Barrat F, Gilliet M. Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells: One-Trick Ponies or Workhorses of the Immune System? Nat Rev Immunol (2011) 11(8):558–65. doi: 10.1038/nri3027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. van der Fits L, Mourits S, Voerman JS, Kant M, Boon L, Laman JD, et al. Imiquimod-Induced Psoriasis-Like Skin Inflammation in Mice is Mediated via the IL-23/IL-17 Axis. J Immunol (2009) 182(9):5836–45. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Hurabielle C, Link VM, Bouladoux N, Han SJ, Merrill ED, Lightfoot YL, et al. Immunity to Commensal Skin Fungi Promotes Psoriasiform Skin Inflammation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA (2020) 117(28):16465–74. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2003022117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Lober CW, Belew PW, Rosenberg EW, Bale G. Patch Tests With Killed Sonicated Microflora in Patients With Psoriasis. Arch Dermatol (1982) 118(5):322–5. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1982.01650170036019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Baroni A, Orlando M, Donnarumma G, Farro P, Iovene MR, Tufano MA, et al. Toll-Like Receptor 2 (TLR2) Mediates Intracellular Signalling in Human Keratinocytes in Response to Malassezia Furfur. Arch Dermatol Res (2006) 297(7):280–8. doi: 10.1007/s00403-005-0594-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Kashem SW, Igyarto BZ, Gerami-Nejad M, Kumamoto Y, Mohammed JA, Jarrett E, et al. Candida Albicans Morphology and Dendritic Cell Subsets Determine T Helper Cell Differentiation. Immunity (2015) 42(2):356–66. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.01.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Doebel T, Voisin B, Nagao K. Langerhans Cells - the Macrophage in Dendritic Cell Clothing. Trends Immunol (2017) 38(11):817–28. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2017.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Pietrzak A, Grywalska E, Socha M, Rolinski J, Franciszkiewicz-Pietrzak K, Rudnicka L, et al. Prevalence and Possible Role of Candida Species in Patients With Psoriasis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Mediators Inflamm (2018) 2018:9602362. doi: 10.1155/2018/9602362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Ovčina-Kurtović N, Kasumagić-Halilović E, Helppikangans H, Begić J. Prevalence of Candida Species in Patients With Psoriasis. Acta dermatovenerologica Croatica (2016) 24(3):209–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Kashem Sakeen W, Riedl Maureen S, Yao C, Honda Christopher N, Vulchanova L, Kaplan Daniel H. Nociceptive Sensory Fibers Drive Interleukin-23 Production From CD301b+ Dermal Dendritic Cells and Drive Protective Cutaneous Immunity. Immunity (2015) 43(3):515–26. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.08.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Maruyama K, Takayama Y, Kondo T, Ishibashi KI, Sahoo BR, Kanemaru H, et al. Nociceptors Boost the Resolution of Fungal Osteoinflammation via the TRP Channel-CGRP-Jdp2 Axis. Cell Rep (2017) 19(13):2730–42. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Papayannopoulos V. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps in Immunity and Disease. Nat Rev Immunol (2018) 18(2):134–47. doi: 10.1038/nri.2017.105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Zabieglo K, Majewski P, Majchrzak-Gorecka M, Wlodarczyk A, Grygier B, Zegar A, et al. The Inhibitory Effect of Secretory Leukocyte Protease Inhibitor (SLPI) on Formation of Neutrophil Extracellular Traps. J Leukoc Biol (2015) 98(1):99–106. doi: 10.1189/jlb.4AB1114-543R [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Guiducci C, Tripodo C, Gong M, Sangaletti S, Colombo MP, Coffman RL, et al. Autoimmune Skin Inflammation is Dependent on Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cell Activation by Nucleic Acids via TLR7 and TLR9. J Exp Med (2010) 207(13):2931–42. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Lande R, Gregorio J, Facchinetti V, Chatterjee B, Wang YH, Homey B, et al. Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells Sense Self-DNA Coupled With Antimicrobial Peptide. Nature (2007) 449(7162):564–9. doi: 10.1038/nature06116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Hu SC-S, Yu H-S, Yen F-L, Lin C-L, Chen G-S, Lan C-CE. Neutrophil Extracellular Trap Formation is Increased in Psoriasis and Induces Human β-Defensin-2 Production in Epidermal Keratinocytes. Sci Rep (2016) 6(1):31119. doi: 10.1038/srep31119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Nakajima S, Harrison O, Merrill E, Linehan J, Belkaid Y. 648 Candida Albicans Colonization Exacerbates Skin Inflammation in a Murine Model of Psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol (2017) 137(5):S112. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2017.02.670 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Chun K, Afshar M, Audish D, Kabigting F, Paik A, Gallo R, et al. Hepatitis C may Enhance Key Amplifiers of Psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol (2017) 31(4):672–8. doi: 10.1111/jdv.13578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Farag AGA, Elshayb EE, Sharaky DRA, Elashafey EN, Khadra AAEA. Role of HCV Infection in Psoriasis: A Clinical and Immunohistochemical Study. J Clin Diagn Res (2019) 13(5):WC01–6. doi: 10.7860/jcdr/2019/39627.12833 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Chen M-L, Kao W-M, Huang J-Y, Hung Y-M, Wei JC-C. Human Papillomavirus Infection Associated With Increased Risk of New-Onset Psoriasis: A Nationwide Population-Based Cohort Study. Int J Epidemiol (2020) 49(3):786–97. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyaa027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Stephens GL, Swerdlow B, Benjamin E, Coyle AJ, Humbles A, Kolbeck R, et al. IL-9 is a Th17-Derived Cytokine That Limits Pathogenic Activity in Organ-Specific Autoimmune Disease. Eur J Immunol (2011) 41(4):952–62. doi: 10.1002/eji.201040879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Simeone P, Teson M, Latini A, Carducci M, Venuti A. Human Papillomavirus Type 5 in Primary Keratinocytes From Psoriatic Skin. Exp Dermatol (2005) 14(11):824–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2005.00358.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Wolf P, Seidl H, Back B, Binder B, Hofler G, Quehenberger F, et al. Increased Prevalence of Human Papillomavirus in Hairs Plucked From Patients With Psoriasis Treated With Psoralen-UV-a. Arch Dermatol (2004) 140(3):317–24. doi: 10.1001/archderm.140.3.317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Gabr SA, Berika MY, Alghadir AH. Apoptosis and Clinical Severity in Patients With Psoriasis and HCV Infection. Indian J Dermatol (2014) 59(3):230–6. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.131377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Teng Y, Xie W, Tao X, Liu N, Yu Y, Huang Y, et al. Infection-Provoked Psoriasis: Induced or Aggravated (Review). Exp Ther Med (2021) 21(6):567. doi: 10.3892/etm.2021.9999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Rademaker M, Agnew K, Anagnostou N, Andrews M, Armour K, Baker C, et al. Psoriasis and Infection. A Clinical Practice Narrative. Australas J Dermatol (2019) 60(2):91–8. doi: 10.1111/ajd.12895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Assarsson M, Duvetorp A, Dienus O, Soderman J, Seifert O. Significant Changes in the Skin Microbiome in Patients With Chronic Plaque Psoriasis After Treatment With Narrowband Ultraviolet B. Acta Derm Venereol (2018) 98(4):428–36. doi: 10.2340/00015555-2859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Sophie S, Christian O. Skin Microbiome in Patients With Psoriasis Before and After Balneotherapy at the Thermal Care Center of La Roche-Posay. J Am Acad Dermatol (2016) 74(5):AB276. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.02.1062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Salem I, Ramser A, Isham N, Ghannoum MA. The Gut Microbiome as a Major Regulator of the Gut-Skin Axis. Front Microbiol (2018) 9:1459. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Paetzold B, Willis JR, Pereira de Lima J, Knodlseder N, Bruggemann H, Quist SR, et al. Skin Microbiome Modulation Induced by Probiotic Solutions. Microbiome (2019) 7(1):95. doi: 10.1186/s40168-019-0709-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Benhadou F, Mintoff D, Schnebert B, Thio HB. Psoriasis and Microbiota: A Systematic Review. Diseases (2018) 6(2):47. doi: 10.3390/diseases6020047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Navarro-Lopez V, Martinez-Andres A, Ramirez-Bosca A, Ruzafa-Costas B, Nunez-Delegido E, Carrion-Gutierrez MA, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Oral Administration of a Mixture of Probiotic Strains in Patients With Psoriasis: A Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. Acta Derm Venereol (2019) 99(12):1078–84. doi: 10.2340/00015555-3305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Thio HB. The Microbiome in Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis: The Skin Perspective. J Rheumatol Suppl (2018) 94:30–1. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.180133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Chehoud C, Rafail S, Tyldsley AS, Seykora JT, Lambris JD, Grice EA. Complement Modulates the Cutaneous Microbiome and Inflammatory Milieu. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA (2013) 110(37):15061–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1307855110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Oh J, Byrd AL, Deming C, Conlan S, Program NCS, Kong HH, et al. Biogeography and Individuality Shape Function in the Human Skin Metagenome. Nature (2014) 514(7520):59–64. doi: 10.1038/nature13786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Wilson FC, Icen M, Crowson CS, McEvoy MT, Gabriel SE, Kremers HM. Incidence and Clinical Predictors of Psoriatic Arthritis in Patients With Psoriasis: A Population-Based Study. Arthritis Rheum (2009) 61(2):233–9. doi: 10.1002/art.24172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]