Abstract

Low serum 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D (1,25(OH)2D) in end-stage renal disease (ESRD) is considered a consequence of elevated fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23) and concomitant reduced activity of renal 1α-hydroxylase (CYP27B1). Current ESRD treatment strategies to increase serum calcium and suppress secondary hyperparathyroidism involve supplementation with vitamin D analogues that circumvent 1α-hydroxylase. This overlooks the potential importance of 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D) deficiency as a contributor to low serum 1,25(OH)2D. We investigated the effects of vitamin D (cholecalciferol) supplementation (40,000 IU for 12 weeks and maintenance dose of 20,000 IU fortnightly), on multiple serum vitamin D metabolites (25(OH)D, 1,25(OH)2D3 and 24,25(OH)2D3) in 55 haemodialysis patients. Baseline and 12 month data were compared using related-samples Wilcoxon signed rank test. All patients remained on active vitamin D analogues as part of routine ESRD care. 1,25(OH)2D3 levels were low at baseline (normal range: 60–120 pmol/L). Cholecalciferol supplementation normalised both serum 25(OH)D and 1,25(OH)2D3. Median serum 25(OH)D increased from 35.1 nmol/L (IQR: 23.0–47.5 nmol/L) to 119.9 nmol/L (IQR: 99.5–143.3 nmol/L) (P < 0.001). Median serum 1,25(OH)2D3 and 24,25(OH)2D3 increased from 48.3 pmol/L (IQR: 35.9–57.9 pmol/L) and 3.8 nmol/L (IQR: 2.3–6.0 nmol/L) to 96.2 pmol/L (IQR: 77.1–130.6 pmol/L) and 12.3 nmol/L (IQR: 9–16.4 nmol/L), respectively (P < 0.001). A non-significant reduction in daily active vitamin D analogue dose occurred, 0.94 µmcg at baseline to 0.77 µmcg at 12 months (P = 0.73). The ability to synthesise 1,25(OH)2D3 in ESRD is maintained but is substrate dependent, and serum 25(OH)D was a limiting factor at baseline. Therefore, 1,25(OH)2D3 deficiency in ESRD is partly a consequence of 25(OH)D deficiency, rather than solely due to reduced 1α-hydroxylase activity as suggested by current treatment strategies.

Keywords: vitamin D, mineral metabolism, haemodialysis, secondary hyperparathyroidism

Introduction

The kidney is the major site for synthesis of the active form of vitamin D, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D (1,25(OH)2D). The enzyme that synthesises 1,25(OH)2D from precursor 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D), 1α-hydroxylase (CYP27B1), is expressed primarily in the renal proximal tubule (1, 2), and is positively and negatively regulated by parathyroid hormone (PTH) and fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23), respectively (3). While the kidney has a central role in 1,25(OH)2D production, 1α-hydroxylase activity has been found in several other cell types throughout the body including the parathyroid glands, testes, skin, placenta, decidua and macrophages (4, 5). The precise contribution of these extra-renal sites of 1α-hydroxylase activity to circulating levels of 1,25(OH)2D remains unclear.

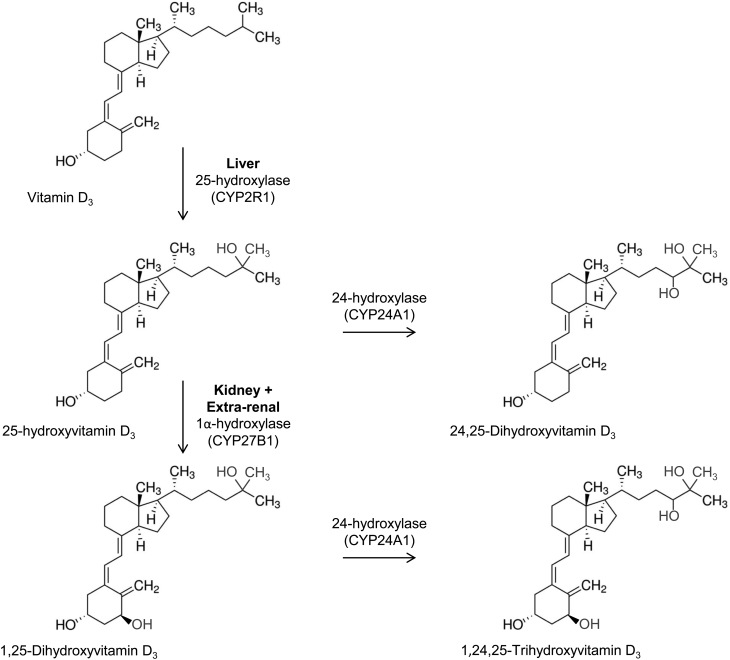

Serum 1,25(OH)2D concentration decreases as chronic kidney disease (CKD) progresses, as a consequence of reduced renal 1,25(OH)2D synthesis (6, 7). This, in turn, contributes to the lack of feedback regulation of PTH that can lead to secondary hyperparathyroidism in CKD, notably in end-stage renal disease (ESRD). To address this, patients with ESRD are routinely prescribed either 1,25(OH)2D (calcitriol), synthetic analogues of 1,25(OH)2D (e.g. paracalcitol) or vitamin D analogues that do not require the action of 1α-hydroxylase (e.g. alfacalcidol). However, patients with ESRD also have low serum levels of the substrate for 1α-hydroxylase (25(OH)D), with reported prevalence rates of 25(OH)D deficiency of up to 95% (8, 9). The significance of this finding is unclear but low serum 25(OH)D may also contribute to impaired feedback regulation of PTH (10). 25(OH)D is a substrate for both activating and catabolic pathways; thus in addition to low serum levels of 25(OH)D and 1,25(OH)2D, CKD patients may also have dysregulated levels of 24,25-dihydroxyvitamin D (24,25(OH)2D). 24,25(OH)2D is the most abundant product of vitamin D catabolism and is produced by the enzyme 24-hydroxylase (CYP24A1) (11). The relative abundance of catabolic vitamin D metabolites such as 24,25(OH)2D in patients with CKD has yet to be fully defined, but it is important to recognise that decreased availability of substrate 25(OH)D may be exacerbated by the stimulatory effect of FGF23 on CYP24A1 (12). With this in mind, recent research in healthy populations suggest that ratios between vitamin D metabolites may provide a more pathophysiologically relevant insight into the metabolism and function of vitamin D (13). An overview of the chemical structures and hydroxylation steps is shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

Vitamin D metabolism – the chemical structures and hydroxylation steps. 25-hydroxylase (25-hydroxylase, CYP2R1) converts vitamin D to 25(OH)D in the liver. 1α-hydroxylase (1α-hydroxylase, CYP27B1) converts 25(OH)D to 1,25(OH)2D in the kidney. Other tissues contain these enzymes, but the liver is the main source of 25-hydroxylase, and the kidney is considered the main source for 1α-hydroxylase. 1,25(OH)2D is further metabolised by 24-hydroxylase (24-hydroxylase, CYP24A1) to 1,24,25(OH)3D. 24-hydroxylase also acts on 25(OH)D to produce 24,25(OH)2D. The production of these metabolites is considered degradation; expression of 24-hydroxylase and 1α-hydroxylase is reciprocal in order to control 1,25(OH)2D levels.

In this study, we hypothesised that ESRD patients undergoing haemodialysis may benefit from supplementation with vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol) to elevate serum 25(OH)D levels in addition to conventional active vitamin D analogues. Based on insight into pathways involved in vitamin D metabolism, we postulated that patients with ESRD, when given sufficient substrate, retain the capacity to generate a significant rise in serum levels of 1,25(OH)2D3

Materials and methods

All aspects of the study received National Health Service ethical approval (reference 14/EE/10 and 14/NS/1012). Patients were included if they were established on haemodialysis for ≥1 month (three sessions per week of 3.5–4 h), had no hospital admissions within the past 4 weeks and had no active malignancy. Patients were excluded if they were already taking cholecalciferol or ergocalciferol. All 202 patients having dialysis at University Hospitals Coventry and Warwickshire (UHCW) satellite dialysis centres meeting the inclusion criteria were invited for recruitment; 81 agreed to participate. Cholecalciferol supplementation was given by the nursing staff, during routine dialysis visits, based on serum 25(OH)D levels. Patients received cholecalciferol, 40,000 IU weekly for 12 weeks if serum 25(OH)D was <50 nmol/L, 20,000 IU fortnightly if serum 25(OH)D was 75–150 nmol/L, and cholecalciferol was stopped if serum 25(OH)D was ≥150 nmol/L. Serum 25(OH)D was measured 3 monthly. The aim was to maintain serum 25(OH)D levels between 75 and 150 nmol/L; the lower target of 75 nmol/L is based on the level defined as sufficient by current Endocrine Society guidelines (14). Active analogue dose was recorded at baseline and study end. Serum calcium was measured monthly and PTH concentration 3 monthly as part of usual care. Blood samples were taken by renal research nurses at routine dialysis sessions, processed and stored at −80°C, for subsequent measurement of serum 25(OH)D, 1,25(OH)2D3 and 24,25(OH)2D3 using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) at baseline (T0) and after 12 months supplementation (T1) (using previously described, quality controlled methods) (15). All samples (T0 and T1) were processed for the measurement of vitamin D metabolites at study end; clinicians were blinded to serum 1,25(OH)2D3 levels during the study. Doses of active vitamin D analogues were modified according to calcium and PTH levels as part of usual practice. Vitamin D metabolite ratios (VMRs): 1,25(OH)2D3:25(OH)D3, 25(OH)D3:24,25(OH)2D3 and 1,25(OH)2D3:24,25(OH)2D3, were calculated. Analysis was carried out using the related-samples Wilcoxon signed rank test and Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient to compare data pre- and post-cholecalciferol supplementation.

Results

Complete data for all parameters at T0 and T1 was obtained for 55 of 81 participants. Reasons for incomplete data were death (n = 15), transplantation (n = 4), change in modality to peritoneal dialysis (n = 1) and haemolysed samples (n = 6). Participants had a median age of 69 (range: 27–76), 50% were male and 93% White. The study population was representative of the local haemodialysis population for all characteristics except for ethnicity; 74% of UHCW haemodialysis patients were White.

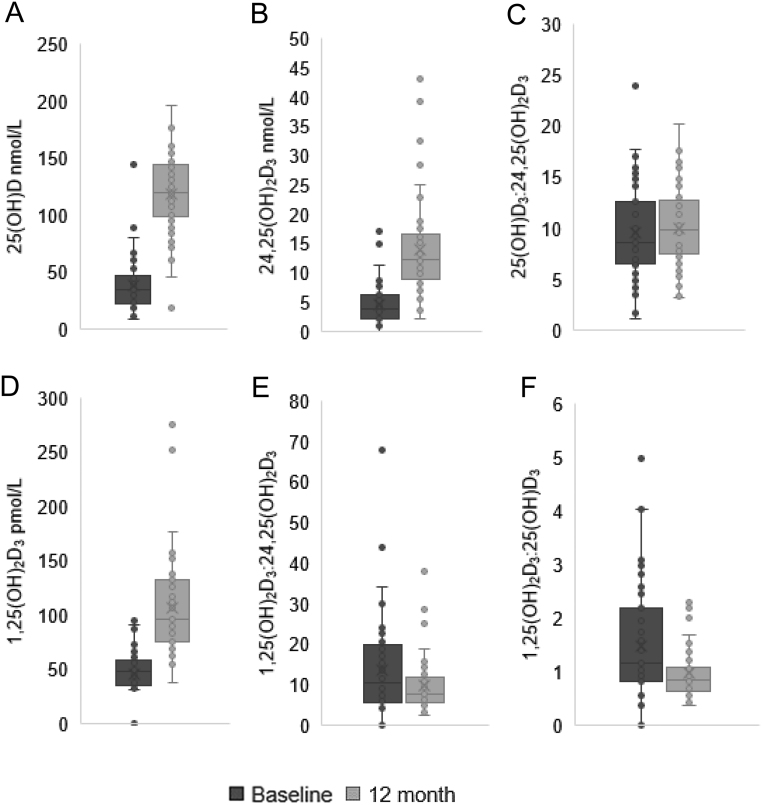

Serum levels of all three vitamin D3 metabolites (25(OH)D3, 1,25(OH)2D3 and 24,25(OH)2D3) showed a significant increase from baseline to 12 months following supplementation with cholecalciferol, P < 0.001 (Fig. 2 and Table 1). This elevation of individual metabolites was associated with a significant reduction in the ratio of 1,25(OH)2D3:25(OH)D3 and 1,25(OH)2D3:24,25(OH)2D3, P = 0.01 and P = 0.05, respectively (Fig. 2 and Table 1). There was no significant change in the ratio of 25(OH)D3:24,25(OH)2D3, P = 0.70. A significant increase in serum calcium occurred, P = 0.001. There was no change in serum PTH (Table 1).

Figure 2.

Serum 25(OH)D, 24,25(OH)2D3 and 1,25(OH)2D3, and the metabolite ratios 25(OH)D3:24,25(OH)2D3, 1,25(OH)2D3:24,25(OH)2D3 and 1,25(OH)2D3:25(OH)D3 at baseline and 12 months. Serum 25(OH)D, 24,25(OH)2D3 and 1,25(OH)2D3 were measured using LC-MS/MS and the ratios 25(OH)D3:24,25(OH)2D3, 1,25(OH)2D3:24,25(OH)2D3 and 1,25(OH)2D3:25(OH)D3 calculated, in patients at baseline, pre-cholecalciferol supplementation (T0), and again at 12 months (T1). (A) Serum 25(OH)D increased: 35.1 nmol/L (23.0–47.5) vs 130.0 nmol/L (99.5–143.3), P < 0.001. (B) Serum 24,25(OH)2D3 increased: 3.8 nmol/L (2.3–6.0) vs 12.3 nmol (9.0–16.4), P < 0.001. (C) No significant change in 25(OH)D3:24,25(OH)2D3: 9.1 (7.0–12.4) vs 10.3 (8.0–12.9) respectively, P = 0.70. (D) Serum 1,25(OH)2D3 increased: 48.3 pmol/L (35.9–57.9) vs 96.2 pmol/L (77.1–130.6), P < 0.001. (E) 1,25(OH)2D3:24,25(OH)2D3 reduced: 10.4 (5.8–19.4) vs 7.9 (5.6–11.9) P = 0.05. (F) 1,25(OH)2D3:25(OH)D3 also reduced: 1.2 (0.8–2.1) vs 0.9 (0.6–1.1), P = 0.01. Wilcoxon signed rank test. Data represent median (IQR), n = 55.

Table 1.

Calcium, parathyroid hormone, vitamin D metabolites and metabolite ratios at baseline and 12 months.

| Serum level/vitamin D metabolite ratio | Baseline (T0) median (IQR) | 12 months (T1) median (IQR) | Wilcoxon signed-rank test (P) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Corrected calcium (mmol/L) | 2.35 (2.23–2.44) | 2.39 (2.32–2.52) | 0.001 |

| Parathyroid hormone (pmol/L) | 27.0 (16.0–43.5) | 29.0 (14.0–42.5) | 0.81 |

| 25(OH)D3 (nmol/L) | 35.1 (23.0–47.5) | 119.9 (99.5–143.3) | <0.001 |

| 1,25(OH)2D3 (pmol/L) | 48.3 (35.9–57.9) | 96.2 (77.1–130.6) | <0.001 |

| 24,25(OH)2D3 (nmol/L) | 3.8 (2.3–6.0) | 12.3 (9–16.4) | <0.001 |

| 1,25(OH)2D3:25(OH)D3 | 1.2 (0.8–2.1) | 0.9 (0.6–1.1) | 0.01 |

| 25(OH)D3:24,25(OH)2D3 | 9.1 (7.0–12.4) | 10.3 (8–12.9) | 0.70 |

| 1,25(OH)2D3:24,25(OH)2D3 | 10.4 (5.8–19.4) | 7.9 (5.6–11.9) | 0.05 |

Serum corrected calcium, parathyroid hormone, 25(OH)D3, 1,25(OH)2D3 and 24,25(OH)2D3 were measured at baseline, pre-cholecalciferol supplementation (T0) and again at 12 months (T1), n = 55. A significant increase was seen from T0 to T1 in calcium and all three vitamin D metabolites. Median calcium remained within target range. The was no change in parathyroid hormone levels. A significant reduction in 1,25(OH)2D3: 25(OH)D3 and 1,25(OH)2D3: 24,25(OH)2D3 occurred but no significant change was seen from baseline to 12 months in 25(OH)D3: 24,25(OH)2D3.

There was no correlation between serum 25(OH)D and 1,25(OH)2D3 at T0 or T1, rho = 0.165, P = 0.23, and rho = 0.180, P = 0.19, respectively. There was also no correlation between serum calcium and serum 25(OH)D at T0 or T1, rho = 0.092, P = 0.10, and rho = 0.106, P = 0.11. Serum 1,25(OH)2D3 did not correlate with calcium at baseline but there was a weak, significant correlation at study end (T1), rho = 0.094, P = 0.50 and rho = 0.288, P = 0.033, respectively. Mean prescribed daily active vitamin D analogue dose reduced from 0.94 at T0 to 0.77 µg at T1 (P = 0.73). Forty-four of 55 patients (80%) were prescribed an active vitamin D analogue at baseline and 41 of 55 (75%) were prescribed an active vitamin D analogue at 12 months. The prescribed dose of active vitamin D analogue reduced during study follow-up in 14 patients, did not change in 25 patients, and increased (or was commenced) in 7 patients. 1-Alfacalcidol accounted 91% of active analogue prescriptions (Table 2).

Table 2.

Active analogue type and dose at baseline and 12 months.

| Active analogue | Baseline (µmcg) mean ± s.d. (n) | 12 month (µmcg) mean ± s.d. (n) | Wilcoxon signed-rank test (P) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1-Alfacalcidol | 0.76 ± 1.30 (n = 40) | 0.58 ± 0.95 (n = 37) | 0.103 |

| Paricalcitol | 8.00 (n = 1) | 8.00 (n = 1) | N/A |

| Calcitriol | 0.92 ± 0.95 (n = 3) | 0.79 ± 1.05 (n = 3) | 0.180 |

| Total combined | 0.94 ± 1.64 (n = 44) | 0.77 ± 1.43 (n = 41) | 0.73 |

Forty-four of 55 (80%) subjects were prescribed an active analogue at the start of the study. 1-Alfacalcidol accounted for 91% of active analogue prescriptions (40 of 44), three patients were prescribed calcitriol and only one patient was prescribed paricalcitol. There was no significant change in active analogue use during the 12-month study period, n = 55.

Discussion

This is the first study to date, to assess the impact of vitamin D supplementation on the serum vitamin D multi-metabolite profile and vitamin D metabolite ratios in ESRD. One of the pathophysiological consequences of CKD is the reduced renal capacity to synthesise 1,25(OH)2D, reportedly due to reduced expression of renal CYP27B and concomitant reduction of 1α-hydroxylase activity in the face of elevated levels of FGF23 (6, 12). In the current study, serum 1,25(OH)2D3 concentrations were low at baseline (median 48.3 pmol/L, IQR: 35.9–57.9, normal reference range 60–108 pmol/L) (16) despite 80% of patients receiving vitamin D analogues to promote 1,25(OH)2D activity in the context of elevated PTH levels. This suggests that vitamin D analogues may be utilised immediately rather than being stored in a serum 1,25(OH)2D pool. A possible explanation for this, yet to be demonstrated in the literature, is that a sudden increase in 1,25(OH)2D3 following active analogue administration is met with a catabolic response (by increased 24-hydroxylase activity) in a bid to minimise the risk of hypercalcaemia. This may, in turn, cause 1,25(OH)2D3 to be metabolised to its less-active 24-hydroxylated catabolite 1,24,25(OH)3D3. This metabolite was not measured in the current study but levels of 24,25(OH)2D3 are frequently used as a general marker of 24-hydroxylase activity. In the current study, the circulating levels of 24,25(OH)2D3 (3.8 nmol/L, 2.3–6.0 nmol/L) were similar to previously reported serum values for healthy individuals (17). However, this level increased three-fold following vitamin D supplementation highlighting further capacity for 24-hydroxylation of vitamin D metabolites that may rapidly counteract elevation of 1,25(OH)2D3 levels following administration of active analogues.

A lack of consensus on optimal serum levels of 25(OH)D has hindered the management of vitamin D deficiency (18, 19). The UK Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition (SACN) guidance recommends serum levels of 25(OH)D ≥25 nmol/L, with supplementation advised for those below this level (20). Most of the participants in the current study would, therefore, not have met the SACN criteria for supplementation at baseline. However, prevention of different chronic disease states may require different serum 25(OH)D concentrations (21). Data from the current study suggest that patients with ESRD may need higher serum 25(OH)D to facilitate optimal 1α-hydroxylase activity; in this study, most patients achieved normal serum 1,25(OH)2D3 concentration with serum 25(OH)D ≥75 nmol/L (the level defined as sufficient by the Endocrine Society) (14).

Data presented here also indicate that ESRD patients retain a significant capacity for 1α-hydroxylase activity, with synthesis of 1,25(OH)2D3 occurring in a substrate (25(OH)D3)-dependent fashion. Previous studies have also described the potential for synthesis of 1,25(OH)2D3 in ESRD patients. Jean et al. demonstrated a rise in serum 1,25(OH)2D3 in response to cholecalciferol supplementation but not within the normal reference range (45 ± 13 pmol/L at study end) (22). Patients had lower baseline serum 1,25(OH)2D3 than the current study and active vitamin D analogue use was an exclusion criteria (22). Other studies also demonstrated increased serum 1,25(OH)2D3 in response to cholecalciferol supplementation, with larger increases seen in patients receiving concomitant alfacalcidol (23). Again, the increased serum 1,25(OH)2D3 in these patients did not reach normal range but this could have been due to the short intervention period of 8 weeks (23). Whether cholecalciferol as a sole therapy is sufficient remains unknown; concurrent active analogue therapy is shown to be safe (not associated with increased risk of hypercalcaemia) (24, 25, 26), and may be required to maintain target serum 1,25(OH)2D3.

Cholecalciferol supplementation increases the inactive substrate 25(OH)D rather than directly increasing 1,25(OH)2D. Increase in serum 25(OH)D and 24,25(OH)2D3 are disproportionate to 1,25(OH)2D3 increase, demonstrating the known tight regulation of 1,25(OH)2D3 synthesis and secretion (in response to calcium and parathyroid hormone) (27). Therefore optimising 25(OH)D through cholecalciferol supplementation will not result in unlimited 1,25(OH)2D and severe hypercalcaemia. An increase in median calcium was seen in this study, but this was not clinically relevant. In addition, the absence of correlation between calcium and 25(OH)D, and 1,25(OH)2D3 and 25(OH)D, supports the documented safety of cholecalciferol supplementation in ESRD (28, 29). Other studies have reported no change in serum calcium in response to cholecalciferol supplementation (23, 24, 25, 26, 30).

Metabolite ratios have been shown to be useful markers of altered vitamin D metabolism. For example a high 1,25(OH)2D:25(OH)D ratio can help diagnose sarcoidosis and a high 25(OH)D:24,25(OH)2D3 ratio can be used to diagnose loss of CYP24A1 (24-hydroxylase) function (31, 32, 33, 34). The metabolite ratio offers insight above that of a single metabolite measurement; a low 24,25(OH)2D3 could simply reflect low 25(OH)D whereas a high 25(OH)D:24,25(OH)2D3 ratio is a viable marker of altered 24-hydroxylase activity (31). A moderate elevation of 25(OH)D:24,25(OH)2D due to reduced activity of 24-hydroxylase is seen in CKD and bone disorders (35, 36, 37). Evidence suggests the value of using 25(OH)D:24,25(OH)2D in assessment and management of both fracture risk and CKD risk (38, 39). Serum 1,25(OH)2D3 is not routinely measured clinically (40, 41); yet in ESRD 1,25(OH)2D3 deficiency is routinely assumed, and active analogue treatment is routinely prescribed (42). A low serum 1,25(OH)2D3 in the presence of a high 1,25(OH)2D3:25(OH)D ratio would indicate that 25(OH)D is limiting synthesis and secretion of 1,25(OH)2D3, suggesting that treatment could include serum 25(OH)D repletion. Results here support the findings of Tang and colleagues who reported an inverse correlation between 1,25(OH)2D:24,25(OH)2D and serum 25(OH)D in healthy young adults (13). Data suggest sufficient serum 25(OH)D provides for maintenance of 1,25(OH)2D and 24,25(OH)2D in relative proportion (within the normal range). In contrast, when 25(OH)D is lacking, 1,25(OH)2D:24,25(OH)2D increases as the production of serum 1,25(OH)2D is prioritised over 24,25(OH)2D. Therefore, it appears that, in the presence of low 25(OH)D, the 24,25(OH)2D pathway is partially inactivated to conserve 25(OH)D for production of 1,25(OH)2D. The same study also demonstrated that low 25(OH)D (<50 nmol/L), normal 1,25(OH)2D and high 1,25(OH)2D:24,25(OH)2D was associated with a significantly higher serum PTH (13). It is anticipated that treatment with active analogues, for suppression of PTH, would increase the 1,25(OH)2D:24,25(OH)2D and, therefore, may be counterproductive. Whereas treatment focusing on optimising 25(OH)D would induce 1α-hydroxylase and 24-hydroxylase, increasing 1,25(OH)2D and 24,25(OH)2D in a regulated fashion, in turn reducing the 1,25(OH)2D:24,25(OH)2D ratio; as shown here. Measurement of vitamin D metabolites and calculation of the metabolite ratios could, therefore, offer insight into the prevention and management of SHPT in CKD. Serum PTH did not change in this study but this may be due to established secondary hyperparathyroidism in this patient cohort which results in parathyroid hyperplasia reducing sensitivity to calcium and 1,25(OH)2D through downregulation of vitamin D receptors and calcium sensing receptors (43, 44). Optimisation of serum 25(OH)D earlier in the progression of CKD may delay the onset, and minimise the severity, of secondary hyperparathyroidism (10). The recognition for the need to treat 25(OH)D deficiency in the management of secondary hyperparathyroidism has grown in recent years, yet in ESRD the emphasis has remained on active analogue treatment (42).

Prescribers have historically promoted active vitamin D analogues to circumvent apparent lack of 1α-hydroxylase activity (and associated 1,25(OH)2D levels) in ESRD yet results here demonstrate otherwise. By their very nature, active vitamin D analogues promote hypercalcaemia. Cholecalciferol is safer and may provide for management of both 25(OH)D and 1,25(OH)2D deficiencies. Is it time to approach vitamin D deficiency in CKD differently by supplementing the substrate and, if indicated by suboptimal serum PTH response, adding in the active analogue? For example, analogous to the management of anaemia where it is routine to administer iron loading initially before concluding a lack of erythropoietin. The focus on active vitamin D analogues for the treatment of 1,25(OH)2D deficiency in ESRD not only overlooks 25(OH)D deficiency, but also vitamin D metabolism as a whole. This risks patients’ missing out on potential non-bone, as well as bone related benefits of serum 25(OH)D (45, 46, 47, 48).

This study is limited by the absence of a control group, so a randomised controlled trial is required to: (i) confirm findings; (ii) explore potential clinical benefits of cholecalciferol repletion; (iii) investigate whether concurrent active analogue therapy is required or whether cholecalciferol is effective as a sole treatment (can calcium and parathyroid hormone levels remain stable without the need for an active vitamin analogue in ESRD?). Whilst research is steering towards more comprehensive analysis of metabolites (49, 50), at present the clinical usefulness of the multi-metabolite assay in ESRD requires further research and measurement of serum 25(OH)D concentration remains the sole marker of vitamin D status (14). The results presented here offer new insight into vitamin D metabolism in ESRD, specifically demonstrating that haemodialysis patients retain the capacity to significantly increase serum 1,25(OH)2D. Conventional oral vitamin D (cholecalciferol) supplementation may, therefore, provide a cheap and safe strategy for the management of vitamin D homeostasis in ESRD patients.

Declaration of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest that could be perceived as prejudicing the impartiality of the research reported.

Funding

This work was supported in part by a grant from the British Renal Society and Kidney Patient Association, and the UK CRN (Study ID numbers: 17213 and 17275).

Consent

Consent has been obtained from each patient or subject after full explanation of the purpose and nature of all procedures.

References

- 1.Brunette MG, Chan M, Ferriere C, Roberts KD. Site of 1,25(OH)2 vitamin D3 synthesis in the kidney. Nature 1978276287–289. ( 10.1038/276287a0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zehnder D, Bland R, Walker EA, Bradwell AR, Howie AJ, Hewison M, Stewart PM. Expression of 25-hydroxyvitamin D-1α-hydroxylase in the human kidney. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 199910 2465–2473. ( 10.1681/ASN.V10122465) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haussler MR, Whitfield GK, Kaneko I, Forster R, Saini R, Hsieh JC, Haussler CA, Jurutka PW. The role of vitamin D in the FGF23, klotho, and phosphate bone-kidney endocrine axis. Reviews in Endocrine and Metabolic Disorders 20121357–69. ( 10.1007/s11154-011-9199-8) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zehnder D, Bland R, Williams MC, McNinch RW, Howie AJ, Stewart PM, Hewison M. Extrarenal expression of 25-hydroxyvitamin D3-1α-hydroxylase. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 200186888–894. ( 10.1210/jcem.86.2.7220) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zehnder D, Evans KN, Kilby MD, Bulmer JN, Innes BA, Stewart PM, Hewison M. The ontogeny of 25-hydroxyvitamin D(3) 1alpha-hydroxylase expression in human placenta and decidua. American Journal of Pathology 2002161105–114. ( 10.1016/s0002-9440(1064162-4) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Levin A, Bakris GL, Molitch M, Smulders M, Tian J, Williams LA, Andress DL. Prevalence of abnormal serum vitamin D, PTH, calcium, and phosphorus in patients with chronic kidney disease: results of the study to evaluate early kidney disease. Kidney International 20077131–38. ( 10.1038/sj.ki.5002009) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Craver L, Marco MP, Martínez I, Rue M, Borràs M, Martín ML, Sarró F, Valdivielso JM, Fernández E. Mineral metabolism parameters throughout chronic kidney disease stages 1-5 – achievement of K/DOQI target ranges. Nephrology, Dialysis, Transplantation 2007221171–1176. ( 10.1093/ndt/gfl718) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saab G, Young DO, Gincherman Y, Giles K, Norwood K, Coyne DW. Prevalence of vitamin D deficiency and the safety and effectiveness of monthly ergocalciferol in hemodialysis patients. Nephron: Clinical Practice 2007105c132–c138. ( 10.1159/000098645) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huish SA, Fletcher S, Dunn JA, Hewison M, Bland R. Prevalence and treatment of hypovitaminosis D in the haemodialysis population of coventry. Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology 2016164214–217. ( 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2016.02.009) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jean G, Vanel T, Terrat JC, Chazot C. Prevention of secondary hyperparathyroidism in hemodialysis patients: the key role of native vitamin D supplementation. Hemodialysis International 201014486–491. ( 10.1111/j.1542-4758.2010.00472.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.St-Arnaud R, Chapter JG. Chapter 6 – CYP24A1: structure, function, and physiological role. In Vitamin D (Fourth Edition), pp. 81–95. Academic Press, 2018.( 10.1016/B978-0-12-809965-0.00006-9) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Quarles LD.Role of FGF23 in vitamin D and phosphate metabolism: implications in chronic kidney disease. Experimental Cell Research 20123181040–1048. ( 10.1016/j.yexcr.2012.02.027) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tang JCY, Jackson S, Walsh NP, Greeves J, Fraser WD. The dynamic relationships between the active and catabolic vitamin D metabolites, their ratios, and associations with PTH. Scientific Reports 201991–10.( 10.1038/s41598-019-43462-6) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holick MF, Binkley NC, Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Gordon CM, Hanley DA, Heaney RP, Murad MH, Weaver CM. & Endocrine Society. Evaluation, treatment, and prevention of vitamin D deficiency: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 2011961911–1930. ( 10.1210/jc.2011-0385) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jenkinson C, Taylor AE, Hassan-Smith ZK, Adams JS, Stewart PM, Hewison M, Keevil BG. High throughput LC-MS/MS method for the simultaneous analysis of multiple vitamin D analytes in serum. Journal of Chromatography: B, Analytical Technologies in the Biomedical and Life Sciences 2016101456–63. ( 10.1016/j.jchromb.2016.01.049) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bouillon R.Comparative analysis of nutritional guidelines for vitamin D. Nature Reviews: Endocrinology 201713466–479. ( 10.1038/nrendo.2017.31) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hassan-Smith ZK, Jenkinson C, Smith DJ, Hernandez I, Morgan SA, Crabtree NJ, Gittoes NJ, Keevil BG, Stewart PM, Hewison M. 25-Hydroxyvitamin D3 and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 exert distinct effects on human skeletal muscle function and gene expression. PLoS ONE 201712 e0170665. ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0170665) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heaney RP.What is vitamin D insufficiency? And does it matter? Calcified Tissue International 201392177–183. ( 10.1007/s00223-012-9605-6) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosen CJ, Taylor CL. Common misconceptions about vitamin D – implications for clinicians. Nature Reviews: Endocrinology 20139 434–438. ( 10.1038/nrendo.2013.75) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition (SACN) SACN vitamin D and health report, 2016. (available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/sacn-vitamin-d-and-health-report) [Google Scholar]

- 21.Muscogiuri G.Vitamin D: past, present and future perspectives in the prevention of chronic diseases. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2018721221–1225. ( 10.1038/s41430-018-0261-4) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jean G, Souberbielle JC, Chazot C. Monthly cholecalciferol administration in haemodialysis patients: a simple and efficient strategy for vitamin D supplementation. Nephrology, Dialysis, Transplantation 2009243799–3805. ( 10.1093/ndt/gfp370) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marckmann P, Agerskov H, Thineshkumar S, Bladbjerg EM, Sidelmann JJ, Jespersen J, Nybo M, Rasmussen LM, Hansen D, Scholze A. Randomized controlled trial of cholecalciferol supplementation in chronic kidney disease patients with hypovitaminosis D. Nephrology, Dialysis, Transplantation 2012273523–3531. ( 10.1093/ndt/gfs138) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mose FH, Vase H, Larsen T, Kancir ASP, Kosierkiewic R, Jonczy B, Hansen AB, Oczachowska-Kulik AE, Thomsen IM, Bech JNet al. Cardiovascular effects of cholecalciferol treatment in dialysis patients – a randomized controlled trial. BMC Nephrology 201415 50. ( 10.1186/1471-2369-15-50) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Delanaye P, Weekers L, Warling X, Moonen M, Smelten N, Medart L, Krzesinski JM, Cavalier E. Cholecalciferol in haemodialysis patients: a randomized, double-blind, proof-of-concept and safety study. Nephrology, Dialysis, Transplantation 2013281779–1786. ( 10.1093/ndt/gft001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seibert E, Heine GH, Ulrich C, Seiler S, Kohler H, Girndt M. Influence of cholecalciferol supplementation in hemodialysis patients on monocyte subsets: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Nephron: Clinical Practice 2013123209–219. ( 10.1159/000354717) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bland R.Calcium homeostasis and bones. In MRCOG Part One: The Official Companion to the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists Revision Course, 1st ed., pp. 83–98. Eds Fiander A, Thilaganathan B. London: RCOG Press, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vieth R.Vitamin D supplementation, 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations, and safety. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 199969842–856. ( 10.1093/ajcn/69.5.842) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition and Allergies (NDA). Scientific opinion on the tolerable upper intake level of vitamin D. EFSA Journal 201210 2813.( 10.2903/j.efsa.2012.2813) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Armas LA, Andukuri R, Barger-Lux J, Heaney RP, Lund R. 25-Hydroxyvitamin D response to cholecalciferol supplementation in hemodialysis. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 201271428–1434. ( 10.2215/CJN.12761211) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kowalska E, Rola R, Wójcik M, Łaszcz N, Płudowski P, Wierzbicka A, Janiec A, Książyk J, Halat P, Ciara Eet al. Analysis of vitamin D3 metabolites in survivors of infantile idiopathic hypercalcemia caused by CYP24A1 mutation or SLC34A1 mutation. Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology 2021208105824. ( 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2021.105824) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rohmer J, Hadjadj J, Bouzerara A, Salah S, Paule R, Groh M, Blanche P, Mouthon L, Monnet D, Le Jeunne Cet al. Serum 1,25(OH)2 vitamin D and 25(OH) vitamin D ratio for the diagnosis of sarcoidosis-related uveitis. Ocular Immunology and Inflammation 202028341–347. ( 10.1080/09273948.2018.1537399) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hilderson I, Van Laecke S, Wauters A, Donck J. Treatment of renal sarcoidosis: is there a guideline? Overview of the different treatment options. Nephrology, Dialysis, Transplantation 2014291841–1847. ( 10.1093/ndt/gft442) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dinour D, Beckerman P, Ganon L, Tordjman K, Eisenstein Z, Holtzman EJ. Loss-of-function mutations of CYP24A1, the vitamin D 24-hydroxylase gene, cause long-standing hypercalciuric nephrolithiasis and nephrocalcinosis. Journal of Urology 2013190552–557. ( 10.1016/j.juro.2013.02.3188) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bosworth CR, Levin G, Robinson-Cohen C, Hoofnagle AN, Ruzinski J, Young B, Schwartz SM, Himmelfarb J, Kestenbaum B, de Boer IH. The serum 24,25-dihydroxyvitamin D concentration, a marker of vitamin D catabolism, is reduced in chronic kidney disease. Kidney International 201282693–700. ( 10.1038/ki.2012.193) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stubbs JR, Zhang S, Friedman PA, Nolin TD. Decreased conversion of 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 to 24,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 following cholecalciferol therapy in patients with CKD. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 201491965–1973. ( 10.2215/CJN.03130314) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Edouard T, Husseini A, Glorieux FH, Rauch F. Serum 24,25-dihydroxyvitamin D concentrations in osteogenesis imperfecta: relationship to bone parameters. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 2012971243–1249. ( 10.1210/jc.2011-3015) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Figueres ML, Linglart A, Bienaime F, Allain-Launay E, Roussey-Kessler G, Ryckewaert A, Kottler ML, Hourmant M. Kidney function and influence of sunlight exposure in patients with impaired 24-hydroxylation of vitamin D due to CYP24A1 mutations. American Journal of Kidney Diseases 201565122–126. ( 10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.06.037) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ginsberg C, Katz R, de Boer IH, Kestenbaum BR, Chonchol M, Shlipak MG, Sarnak MJ, Hoofnagle AN, Rifkin DE, Garimella PSet al. The 24,25 to 25-hydroxyvitamin D ratio and fracture risk in older adults: the cardiovascular health study. Bone 2018107124–130. ( 10.1016/j.bone.2017.11.011) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lips P.Relative value of 25(OH)D and 1,25(OH)2D measurements. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research 2007221668–1671. ( 10.1359/jbmr.070716) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Webb AR.Who, what, where and when – influences on cutaneous vitamin D synthesis. Progress in Biophysics and Molecular Biology 20069217–25. ( 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2006.02.004) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD-MBD Update Work Group. KDIGO 2017 clinical practice guideline update for the diagnosis, evaluation, prevention, and treatment of chronic kidney disease-mineral and bone disorder (CKD-MBD). Kidney International Supplements 201720171–59.( 10.1016/j.kisu.2017.04.001) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Slatopolsky E, Brown A, Dusso A. Pathogenesis of secondary hyperparathyroidism. Kidney International: Supplement 199973S14–S19. ( 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.07304.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brown EM, Wilson RE, Eastman RC, Pallotta J, Marynick SP. Abnormal regulation of parathyroid hormone release by calcium in secondary hyperparathyroidism due to chronic renal failure. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 198254172–179. ( 10.1210/jcem-54-1-172) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Boudville N, Inderjeeth C, Elder GJ, Glendenning P. Association between 25-hydroxyvitamin D, somatic muscle weakness and falls risk in end-stage renal failure. Clinical Endocrinology 201073299–304. ( 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2010.03821.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kiss Z, Ambrus C, Almasi C, Berta K, Deak G, Horonyi P, Kiss I, Lakatos P, Marton A, Molnar MZet al. Serum 25(OH)-cholecalciferol concentration is associated with hemoglobin level and erythropoietin resistance in patients on maintenance hemodialysis. Nephron: Clinical Practice 2011117c373–c378. ( 10.1159/000321521) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Srisakul U, Gilmartin C, Akkina S, Porter A. 302 Effects of vitamin D repletion on hemoglobin and the dose of an erythropoiesis stimulating agent. American Journal of Kidney Diseases 201157 A92. ( 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.02.305) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Matias PJ, Jorge C, Ferreira C, Borges M, Aires I, Amaral T, Gil C, Cortez J, Ferreira A. Cholecalciferol supplementation in hemodialysis patients: effects on mineral metabolism, inflammation, and cardiac dimension parameters. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 20105905–911. ( 10.2215/CJN.06510909) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tuckey RC, Cheng CYS, Slominski AT. The serum vitamin D metabolome: what we know and what is still to discover. Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology 20191864–21. ( 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2018.09.003) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jenkinson C.The vitamin D metabolome: an update on analysis and function. Cell Biochemistry and Function 201937408–423. ( 10.1002/cbf.3421) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

This work is licensed under a

This work is licensed under a