Abstract

Background:

Injuries are common in collegiate Gaelic games, and negative psychological responses to injury, such as fear avoidance and a lack of psychological readiness to return to sport, can affect players during their rehabilitation and their subsequent return to sport. Thus, identifying these responses in players can allow clinicians to address these issues during rehabilitation. This study aimed to examine fear avoidance and psychological readiness to return to sport in collegiate Gaelic games players.

Hypothesis:

Collegiate Gaelic games players will experience similar levels of fear avoidance and psychological readiness to return to sport as other adult athletes.

Study Design:

Cohort study.

Level of Evidence:

Level 3.

Methods:

Male (n = 150) and female (n = 76) players from 1 Irish collegiate institution were recruited. Players that were injured over 1 collegiate season completed the Athlete Fear Avoidance Questionnaire (AFAQ) immediately after the injury and the Injury-Psychological Readiness to Return to Sport (I-PRRS) Scale once cleared to return to sport. An injury report form was also completed. The overall AFAQ (sum of 10 items) and I-PRRS (sum of 6 items/10) scores were calculated.

Results:

Seventy-three injuries (n = 73) occurred, and injured players had a mean overall AFAQ and I-PRRS score of 22.6 ± 5.3 and 46.4 ± 8.8, respectively. Just less than half (47.9%) of players were deemed psychologically unready to return to sport when cleared physically. After severe injuries, significantly higher overall AFAQ scores than mild injuries (P = 0.01) and lower overall I-PRRS than moderate injuries (P < 0.0001) was noted. For the overall scores, no gender differences were observed.

Conclusion:

Fear avoidance and lowered confidence levels before return to sport occurs in collegiate Gaelic games players similar to other student-athletes.

Clinical Relevance:

Identification of fear avoidance or low readiness to return to sport, particularly after serious injury, is important to implement psychosocial support during their rehabilitation.

Keywords: negative psychological response, fear of injury, confidence

Gaelic games are popular Irish field collegiate sports that include Gaelic football and hurling; the female equivalent is Ladies Gaelic football and Camogie. At collegiate level, these sports are 60 minutes in duration 27 with Gaelic football being played with a ball, similar to a soccer ball, that is kicked and hand-passed,23,27 while hurling/Camogie players use a stick called a hurley to hit a small leather ball.2,25 Fifteen players on each team (a goalkeeper, 6 defenders, 2 midfielders, and 6 forwards) compete and a score is achieved by kicking or hitting the ball under or over the crossbar of the opponents goal.25,26 These high-speed contact sports vary between genders by minor rule differences.25,27 Greater contact is permitted in the male sports of Gaelic football and hurling, with a shoulder to shoulder charge allowable. However, in Ladies Gaelic football and Camogie, shouldering is prohibited. Injuries are prevalent, with a match injury rate of 25.1 injuries 27 and 42.5 injuries per 1000 hours 24 noted in male and female collegiate Gaelic footballers, respectively. While no research has examined injury rates for hurling and Camogie at the collegiate level, previous research in elite male hurlers noted a high match injury rate (61.8 injuries per 1000 hours) 2 and 88.2% of Camogie elite and nonelite players sustained an injury the previous season. 25 While much of the focus in research has been on the physical impact that injuries can have on a player, the psychological consequences can also be substantial. 1 Negative psychological responses to injury can affect players throughout the rehabilitation process, from the initial diagnosis through their return to sport. 1 Two key elements of negative psychological response are fear avoidance and a lack of psychological readiness to return to sport. Therefore, identifying the prevalence of these maladaptive responses in players can be helpful for clinicians, such as athletic trainers/therapists, physical therapists, and sports medicine physicians, so they are aware of these responses in the rehabilitation process.

The “fear avoidance model” outlines how a person’s reaction to pain and consequential avoidance behaviors in response to pain can lead to dysfunction. 21 A player experiencing fear avoidance in response to an injury may exhibit behaviors that negatively affect his or her recovery.12,28 If a clinician identifies fear avoidance concerns early in the rehabilitation process, they can address this issue promptly and ensure the player is fully psychosocially supported. 1 At the return-to-sport stage, injured players typically undergo and pass physical, functional, and sports-specific tests to be identified as ready to return to sport. 6 However, ensuring players are not only physically ready but also psychologically ready to return to sport at the end of the rehabilitation process is an important step in patient-centered care and the return-to-sport process. 30 Low confidence, at the end of the rehabilitation, can influence their psychological readiness to return to sport 13 and consequentially their return to sport. 1 Psychological rehabilitation and psychosocial interventions (eg, goal setting, positive self-talk, imagery) may address fear avoidance and confidence issues. Previous research has found that after a cognitive-behavioral intervention during rehabilitation, male athletes after knee surgery experienced less postsurgical pain, anxiety and returned to sport quicker 31 and competitive athletes with long-term injuries displayed an improved mood. 17 However, before implementation, a need for such interventions must first be identified by either the athlete or the clinician.

In comparison with the general population, athletes’ responses to injury could differ because of the important role sport plays in their lives. 9 Therefore, measures specific to the athletic population are required when examining fear avoidance or readiness to return in athletes. The Athlete Fear Avoidance Questionnaire (AFAQ) 9 has been internally and externally validated in the athletic population and measures sport injury related fear avoidance in athletes. Additionally, the Injury Psychological Readiness to Return to Sport (I-PRRS) questionnaire 13 examines the confidence a player has in his or her ability to return to sport and has been found to be valid and reliable. To date, however, there is limited research examining negative psychological responses in the Irish athletic context. The psychological readiness to return to sport in Gaelic games players of any gender or age has yet to be investigated. Just 1 study 28 has examined fear avoidance in Irish athletes, and this focused on male adolescent Gaelic footballers only. However, no previous research has examined fear avoidance in adult and female Gaelic games players. Consequently, gender differences in how players may react to injury has yet to be examined. Therefore, this study aimed to examine fear avoidance after injury and psychological readiness to return to sport in male and female collegiate Gaelic games players. A secondary aim was to investigate whether psychological responses differed between genders or the severity of injury. We hypothesize that collegiate Gaelic games players will experience similar levels of fear avoidance and psychological readiness to return to sport as other adult athletes and that more severe injuries lead to greater negative psychological responses.

Methods

Participants and Procedures

Male (n = 150) and female (n = 76) collegiate Gaelic games players from 1 educational institution were followed over 1 collegiate season. Ethical approval was granted by the Dublin City University research ethics committee. Student athletic therapists and trainers, present at all collegiate trainings and games as part of their collegiate degree, examined any injuries that occurred during collegiate Gaelic games. They then referred the injured participant to an on-campus clinic where they were further examined by a certified athletic therapist or sports medicine physician who confirmed the diagnosis. Immediately after the injury and once the injury diagnosis was provided to the participant (within 24 hours of the injury), the participant completed the AFAQ. An injury report form was also completed by the student athletic therapist and trainer or certified athletic therapist who conducted the assessment. The participant then completed a rehabilitation program either on campus or with a clinician from their own club external to the college. Once the player was cleared for return to sport, the participant completed the I-PRRS questionnaire. For participants who were cleared to play by their own clinician, this was confirmed by the student athletic therapist and trainer before completion of the questionnaire. The severity of injury was also noted once cleared to return to sport and defined similar to previous research in collegiate Gaelic footballers as mild (≤7 days), moderate (8-21 days), or severe (>21 days). 27

Instruments

The AFAQ is a 10-item scale that requires injured participants to rate on a 5-point (1-5) Likert-type scale their agreement with each statement that relates to fear avoidance (Table 1). The score on each of the statements is summated to provide the overall AFAQ score. The higher the score, the greater the fear avoidance noted, with a maximum overall AFAQ score of 50. The I-PRRS measures confidence and psychological readiness to return to sport. Each of the 6 statements are ranked on a scale of 0 to 100, with 0 equating to no confidence at all, 50 moderate confidence, and 100 complete confidence. Each of the 6 statements results are then summated and divided by 10 to provide the overall I-PRRS score, with a maximum score of 60. An overall I-PRRS score of less than 50 indicates they may not be psychologically ready to return to sport. 13 High reliability in the current study for both instruments was evident as the Cronbach α coefficient of 0.70 and 0.84 was noted for the AFAQ and I-PRRS, respectively. The injury report form, previously utilized in Gaelic games26,27 was implemented. This 22-question form required information on the injury event and outcome (eg, sport played, injury diagnosis, mechanism, and severity).

Table 1.

Athlete Fear Avoidance Questionnaire (AFAQ) and Injury-Psychological Readiness to Return to Sport (I-PRRS) individual statements

| AFAQ |

| I will never be able to play as I did before my injury |

| I am worried about my role with the team changing |

| I am worried what other people will think of me if I don’t perform at the same level |

| I am not sure what my injury is |

| I believe that my current injury has jeopardized my future athletic abilities |

| I am not comfortable going back to play until I am 100% |

| People don’t understand how serious my injury is |

| I don’t know if I am ready to play |

| I worry if I go back to play too soon I will make my injury worse |

| When my pain is intense I worry my injury is a very serious one |

| I-PRRS |

| My overall confidence to play is |

| My confidence to play without pain is |

| My confidence to give 100% effort is |

| My confidence to not concentrate on the injury is |

| My confidence in the injured body part to handle the demands of the situation is |

| My confidence in my skill level/ability is |

Statistical Analysis

All data were entered into SPSS version 25. Data were nonnormal except for AFAQ overall scores. Therefore, a 2-way analysis of variance was conducted between gender (male vs female) and severity (mild vs moderate vs severe) for AFAQ overall score. Effect sizes were calculated using partial eta-squared (h2p) and classified as small (0.01), medium (0.06), and large (0.14). 7 The Mann-Whitney U test was used to examine differences in gender for all individual AFAQ statements, I-PRRS overall score, and I-PRRS individual statements. Effect sizes were calculated and classified as small (r = 0.1), medium (r = 0.3), and large (r = 0.5). 7 Kruskal-Wallis test was used to examine differences between injury severity for the nonparametric data. When significant differences were noted, a post hoc analysis using the Mann-Whitney U test with a Bonferroni adjustment was conducted. Descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation, range) were calculated for all scores. The percentage of participants that scored less than 50 in the I-PRRS overall score was measured, and this was repeated for gender and injury severity variables. A significance level of 0.05 was set.

Results

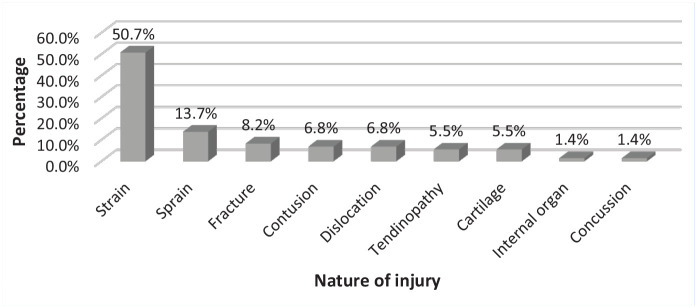

Seventy-three injuries were recorded in the 226 Gaelic games players, with 41 injuries in male players and 32 in female players. Severe injuries were most common (n = 30), followed by moderate (n = 28) and mild (n = 15). In male players, severe injuries were most frequent (n = 21), with moderate (n = 16) and mild (n = 4) injuries less common. In contrast, in female players, moderate injuries occurred most commonly (n = 12), followed by mild (n = 11) and severe (n = 9). Figure 1 displays the nature of injuries that occurred during the season.

Figure 1.

Nature of injury.

AFAQ

The mean overall AFAQ score was 22.6 ± 5.3 (Table 2). For the 2-way analysis of variance, no interaction effect or main effect for gender were noted (P < 0.05) for the overall AFAQ. However, there was a significant main effect for injury severity with a medium effect size (P = 0.02, h2p = 0.12). Post hoc analysis revealed that those with severe injuries demonstrated a significantly higher overall AFAQ score than players with mild injuries (P = 0.01).

Table 2.

Mean, standard deviation, and range of scores for individual statements and overall AFAQ score for all injured participants, gender, and injury severity

| Gender | Injury Severity | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statement | Total Sample, Mean ± SD (Range) | Male, Mean ± SD (Range) | Female, Mean ± SD (Range) | Mild, Mean ± SD (Range) | Moderate, Mean ± SD (Range) | Severe, Mean ± SD (Range) |

| Never be able to play as I did before my injury | 1.3 ± 0.7 (1-4) | 1.4 ± 0.8 (1-4) | 1.1 ± 0.3 a (1-2) | 1.0 ± 0.0 (1-1) | 1.1 ± 0.3 (1-2) | 1.6 ± 0.9 b (1-4) |

| Worried about my role with the team changing | 2.4 ± 1.1 (1-5) | 2.5 ± 1.1 (1-5) | 2.3 ± 1.1 (1-5) | 2.0 ± 1.1 (1-5) | 2.4 ± 0.9 (1-5) | 2.6 ± 1.3 (1-5) |

| Worried what other people will think of me if I don’t perform at the same level | 2.3 ± 1.1 (1-5) | 2.1 ± 1.1 (1-5) | 2.4 ± 0.9 (1-4) | 1.9 ± 0.9 (1-4) | 2.4 ± 1.2 (1-5) | 2.3 ± 1.0 (1-4) |

| Not sure what my injury is | 1.7 ± 1.0 (1-5) | 1.3 ± 0.7 (1-3) | 2.1 ± 1.3 c (1-5) | 1.9 ± 1.2 (1-4) | 1.6 ± 1.1 (1-5) | 1.6 ± 0.9 (1-4) |

| Believe that my current injury has jeopardized my future athletic abilities | 1.4 ± 0.7 (1-4) | 1.5 ± 0.8 (1-4) | 1.2 ± 0.4 (1-2) | 1.1 ± 0.3 (1-2) | 1.4 ± 0.7 (1-4) | 1.6 ± 0.7 b (1-3) |

| Not comfortable going back to play until I am 100% | 2.8 ± 1.3 (1-5) | 3.1 ± 1.3 (1-5) | 2.5 ± 1.2 (1-5) | 2.2 ± 1.4 (1-5) | 2.9 ± 1.2 (1-5) | 3.1 ± 1.3 (1-5) |

| People don’t understand how serious my injury is | 2.2 ± 1.0 (1-4) | 2.2 ± 1.1 (1-4) | 2.1 ± 1.0 (1-4) | 1.7 ± 0.8 (1-3) | 2.2 ± 1.2 (1-4) | 2.4 ± 0.9 (1-4) |

| I don’t know if I am ready to play | 2.2 ± 1.0 (1-5) | 2.2 ± 1.0 (1-5) | 2.2 ± 1.1 (1-4) | 1.8 ± 0.9 (1-3) | 2.0 ± 1.0 (1-5) | 2.5 ± 1.1 (1-4) |

| Worry if I go back to play too soon I will make my injury worse | 3.2 ± 1.1 (1-5) | 3.3 ± 1.2 (1-5) | 3.1 ± 1.1 (1-5) | 3.1 ± 1.3 (1-5) | 3.0 ± 1.1 (1-5) | 3.5 ± 1.0 (1-5) |

| When my pain is intense I worry my injury is a very serious one | 3.2 ± 1.0 (1-5) | 3.2 ± 1.1 (1-5) | 3.1 ± 0.9 (2-5) | 3.2 ± 1.2 (2-5) | 2.9 ± 1.0 (1-5) | 3.4 ± 0.9 (2-5) |

| Overall AFAQ score | 22.6 ± 5.3 (12-35) | 22.9 ± 5.7 (12-35) | 22.1 ± 4.6 (13-31) | 19.9 ± 4.6 (12-27) | 21.8 ± 5.8 (13-35) | 24.6 ± 4.3 b (15-33) |

AFAQ, Athlete Fear Avoidance Questionnaire.

Significantly less in females than in males.

Significantly greater in severe than in mild injuries; significantly greater in severe than in moderate injuries.

Significantly greater in females than males.

For the individual statements within the AFAQ, male players scored significantly higher with a small effect size in the variable “I will never be able to play as I did before my injury” (P = 0.03, r = 0.25) and female players scored higher with a medium effect size on “I am not sure what my injury is” (P = 0.004, r = 0.33). No significant differences between genders were observed for the other individual statements. For severity, a significant difference was noted (P = 0.002) for “I will never be able to play as I did before my injury,” with post hoc analysis noting that severe injuries scored higher than both mild (P = 0.005, r = 0.42) and moderate injuries (P = 0.009, r = 0.34). A significant difference was also noted for “I believe my current injury has jeopardized my future athletic abilities” (P = 0.02), with severe injuries scoring significantly higher with a medium effect size than mild injuries only (P = 0.008, r = 0.40).

I-PRRS

The overall average score for the I-PRRS was 46.4 ± 8.8 (scores ranged between 21 and 58). In total, 47.9% of players displayed a score of less than 50 and so are deemed psychologically unready to return to sport. Male (46.3%, n = 19) and female players (50.0%, n = 16) presented with a similar prevalence of players with scores less than 50. In fact, 70% of players after a severe injury were defined as not psychologically ready to return to play (n = 21), followed by mild injuries (46.7%, n = 7) and moderate injuries (25.0%, n = 7). Table 3 displays the mean, standard deviation, and range for the overall I-PRRS score and individual statements within the I-PRRS.

Table 3.

Mean, standard deviation, and range of scores for individual statements and overall I-PRRS score for all participants, gender, and injury severity

| Gender | Injury Severity | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statement | Total Sample, Mean ± SD (Range) | Male, Mean ± SD (Range) | Female, Mean ± SD (Range) | Mild, Mean ± SD (Range) | Moderate, Mean ± SD (Range) | Severe, Mean ± SD (Range) |

| Overall confidence to play | 79.9 ± 19.2 (30-100) | 81.5 ± 18.7 (30-100) | 77.85 ± 20.0 (40-100) | 74.7 ± 25.3 (30-100) | 88.2 ± 16.6 (30-100) | 74.7 ± 15.5 a (50-100) |

| Confidence to play without pain | 75.5 ± 19.2 (30-100) | 78.1 ± 18.7 (30-100) | 72.25 ± 19.5 (30-100) | 76.0 ± 25.0 (30-100) | 78.9 ± 16.2 (50-100) | 72.0 ± 18.5 (30-100) |

| Confidence to give 100% effort | 88.5 ± 19.2 (20-100) | 86.1 ± 22.5 (20-100) | 91.65 ± 13.7 (50-100) | 90.0 ± 17.7 (40-100) | 90.0 ± 18.5 (20-100) | 86.3 ± 20.9 (30-100) |

| Confidence to not concentrate on the injury | 69.6 ± 21.6 (0-100) | 69.3 ± 22.0 (20-100) | 70.0 ± 21.6 (0-100) | 70.7 ± 22.2 (50-100) | 72.5 ± 19.2 (30-100) | 66.3 ± 23.7 (0-100) |

| Confidence in the injured body part to handle the demands of the situation | 70.6 ± 19.1 (30-100) | 69.0 ± 20.5 (20-100) | 72.5 ± 17.4 (30-100) | 68.0 ± 20.8 (30-100) | 76.8 ± 17.0 (30-100) | 66.0 ± 19.2 (30-100) |

| Confidence in my skill level/ability | 80.7 ± 16.7 (40-100) | 85.4 ± 15.8 (40-100) | 79.4 ± 17.4 (40-100) | 81.3 ± 19.2 (40-100) | 87.5 ± 15.3 (40-100) | 79.0 ± 16.1 (50-100) |

| Overall score | 46.4 ± 8.8 (21-58) | 46.4 ± 9.2 (21-58) | 46.4 ± 8.4 (25-58) | 46.1 ± 10.0 (29-58) | 49.46 ± 8.3 (21-58) | 43.8 ± 7.9 a (25-57) |

I-PRRS, Injury-Psychological Readiness to Return to Sport scale.

Significantly less confidence in severe than in moderate injuries.

No significant differences between genders (P > 0.05) were observed for the overall I-PRRS score or the individual statements. A significant difference for injury severity was noted for overall I-PRRS score (P = 0.006) and “overall confidence to play” (P = 0.003). Mann-Whitney U tests revealed that players with severe injuries demonstrated significantly lower confidence scores than moderate injuries with a medium effect size for both the overall confidence statement (P < 0.0001, r = 0.47) and overall I-PRRS score (P < 0.0001, r = 0.44).

Discussion

This study aimed to investigate fear avoidance after injury and psychological readiness to return to sport in male and female collegiate Gaelic games players and identify if any differences in psychological response exist between genders or injuries of different severity. The overall AFAQ score in the current study (22.6 ± 5.3) was similar to previous research in male adolescent Gaelic footballers (22.1 ± 7.1), 28 as well as non-Irish collegiate student-athletes (23.7 ± 7.0) 9 and adult athletes (26 ± 8.0). 12 This indicates that male and female collegiate Gaelic games players experience fear avoidance to a similar extent as adolescent athletes nationally 28 and student-athletes and adult athletes internationally in other sports.9,12 Identifying the presence of fear avoidance in Gaelic games players, and all athletes, early in the rehabilitation process is important, as previous research has found that higher fear avoidance can lead to reduced physical function. 12 Therefore, clinicians working with athletes should consider implementing patient-reported outcome measures, such as the AFAQ, across all collegiate Gaelic games players once they become injured. This will help identify if any players are experiencing fear avoidance as this may be a barrier to their recovery. Players demonstrated the highest scores in the statements “I worry if I go back to play too soon I will make my injury worse” (3.2 ± 1.1) and “when my pain is intense I worry my injury is a very serious one” (3.2 ± 1.1). Adolescent male Gaelic games players similarly reported highest scores relating to worries surrounding returning to play too soon and its potential negative impact on their injury (2.6 ± 1.3). 28 Multifactorial strategies based on the biopsychosocial model, including physical rehabilitation, education on pain and fear of movement, and mindfulness meditation, have been shown to improve fear avoidance beliefs. 16 Thus, clinicians who encounter fear avoidance beliefs with their athletes can incorporate these psychosocial interventions to enhance their rehabilitation outcomes.

Players with severe injuries demonstrated greater fear avoidance than those with minor injuries in the current study. This may be expected, as players with serious injuries may have higher pain scores after injury and their physical function may be impacted to a greater extent. Previous research has found that higher fear avoidance is noted in those with reduced physical function 12 and higher pain scores. 28 While gender did not impact overall AFAQ scores, male players were found to worry significantly more than female players about their ability to perform as they did before their injury. Goal setting allows the athlete to have a clear direction and focus on their rehabilitation plan, 32 and has been shown to improve their self-efficacy and self-confidence during rehabilitation.10,11 Therefore, collaborating with male Gaelic games players in particular to generate both long- and short-term goals throughout the rehabilitation process should be key for all clinicians. End-stage rehabilitation exercises should also incorporate sport-specific skill elements to enhance their self-perceived level of confidence along with physical sport-specific return-to-play criteria. Female players reported significantly more uncertainty around what the injury is than male players. Patients can sometimes have difficulty comprehending their diagnosis 19 and being unsure of what their injury is, with previous research finding that after an appointment with a general practice physician, patients did not understand between 7% and 47% of information relating to the diagnosis. 29 This is concerning, as poor health literacy can affect their overall health outcome.3,8 To ensure athletes fully understand the information given to them, clinicians could ask the athlete to repeat back to them at the end of the session their understanding of the diagnosis and what it means. 20 This may allow the clinicians to clarify any misunderstandings in their comprehension of not only the diagnosis but also its impact on their health and athletic performance long term. Encouraging patients to ask questions and avoiding technical terms when explaining the injury could also aid their comprehension. 20 While it is unclear to why female players were less confident in knowing exactly what their injury was, it is worth noting that patients who perceive that their clinician has greater empathy toward them display higher health literacy. Thus, prioritizing these techniques in female athletes in particular may be beneficial. 5

The mean I-PRRS overall score in the current study (46.4 ± 8.8) was similar to previous research in collegiate student-athletes in the United States (45.3 ± 9.6) 13 but higher than a single case study of an elite professional soccer player (31). 22 However, when cleared to return to sport physically, just under half of all collegiate Gaelic games players scored less than 50 in the I-PRRS and so may be psychologically unready to return to sport. This is concerning, as low psychological readiness to return to sport may impact players’ performances after injury, increase competitive anxiety, and ultimately increase the likelihood of reinjury.14,15 Gender did not affect Gaelic games players’ psychological readiness to return to sport. However, lack of psychological readiness to return to sport was magnified for those who suffered a severe injury as 70% were deemed unready to return to sport. Severe injuries can display more serious and extended negative psychological responses,1,18,33 and clinicians should be mindful to engage in psychological rehabilitation with patients with severe injuries. Clinicians should also be aware of when to refer to a psychologist, sports medicine physician, or local general practitioner to access further mental health help and be proactive in these referrals when required. Players with mild injuries (taking ≤7 days to return to sport) did not demonstrate significantly lower confidence than moderate injuries, but a higher percentage were deemed psychologically unready to return to sport (46.7% vs 25.0%). This may have been related to a worry surrounding their quick return to sport and potentially these players may have been under pressure to return quickly to sport because of important games in the near future. In contrast, players with moderate injuries (that varied in their return between 8 and 21 days) perhaps were more confident in their return and had more time to complete a more graded return to sport and psychologically process their injury. Further investigation on the reasoning behind lower confidence in players with a minor injury is required. Players were least confident in their ability to not concentrate on the injury (69.6 ± 21.6) and in the injured body part to handle the demands of the situation (70.6 ± 19.1). Previous research in professional rugby players after anterior cruciate ligament injury found that the predominant aim of players was to build confidence in their injured knee before return to sport. 4 Thus ensuring players build their confidence in the specific injured body part by sequentially completing clinical tasks, right up to sport specific movements that test and target the injured limb functionally, is critical before return to sport.

Limitations

There are a number of limitations to the current study. First, no pain score was measured at the same time as the AFAQ. Previous research has found that AFAQ postinjury is higher in those with higher pain scores in adolescent Gaelic footballers, 28 and so future studies should examine pain using a visual analogue scale score concurrently. Second, data were collected from 1 institution only and a relatively small number of injuries were reported. When collecting the data, authors aimed to ensure the AFAQ and I-PRRS were implemented at clearly defined time points in the rehabilitation process. However, not all Irish institutions’ Gaelic Athletic Association teams have clinicians or student clinicians present at all training sessions and games. The authors were confident that the participants from the recruited institution in this study could feasibly complete the forms in the appropriate time limit because of the presence of student athletic therapists and trainers at all training and games. Future studies should aim to recruit a larger cohort from multiple institutions to ensure generalizability of results. Finally, 1 season was prospectively followed in the current study, and so injuries that lead to time-loss beyond the season were not included in the current study. Thus, future studies should examine the psychological impact of injuries across multiple collegiate seasons.

Conclusion

Fear avoidance and low confidence levels were noted in male and female collegiate Gaelic games players, with just under half of all players identified as psychologically not ready to return to sport, even when cleared to do so physically. Fear avoidance and confidence levels noted in Irish male and female collegiate players were similar to previously reported. The AFAQ and I-PRRS can be helpful to identify those at risk of fear avoidance and low readiness to return to sport after an injury. Clinicians can then address these highlighted issues during rehabilitation by working with the athlete to undertake problem focused coping strategies to ensure players are psychologically ready to return to sport. Clinicians should be aware that players with severe injuries demonstrated more fear avoidance and lowered confidence, and so incorporating psychological rehabilitation may be of particular importance to this population. During rehabilitation, focusing on both physical and psychological elements is necessary and before return to sport implementing a physical and psychological readiness to play battery of tests may be beneficial in collegiate Gaelic games.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to the players and management of DCU Dóchas Éireann for their assistance in data collection and in particular Interim Head of Gaelic Games in DCU, Mr Paul O’Brien.

Footnotes

The authors report no potential conflicts of interest in the development and publication of this article.

References

- 1. Ardern CL, Taylor NF, Feller JA, Webster KE. A systematic review of the psychological factors associated with returning to sport following injury. Br J Sports Med. 2013;47:1120-1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Blake C, O’Malley E, Gissane C, Murphy JC. Epidemiology of injuries in hurling: a prospective study 2007-2011. BMJ Open. 2014;4:1-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Briggs AM, Jordan JE. The importance of health literacy in physiotherapy practice. J Physiother. 2010;56:149-151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Carson F, Polman R. Experiences of professional rugby union players returning to competition following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Phys Ther Sport. 2012;13:35-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chu C-I, Tseng C-CA. A survey of how patient-perceived empathy affects the relationship between health literacy and the understanding of information by orthopedic patients? BMC Public Health. 2013;13:155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Clover J, Wall J. Return-to-play criteria following sports injury. Clin Sports Med. 2010;29:169-175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cohen JW. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2nd ed. Lawrence Erlbaum; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 8. DeWalt DA, Hink A. Health literacy and child health outcomes: a systematic review of the literature. Pediatrics. 2009;124(suppl 3):S265-S274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dover G, Amar V. Development and validation of the Athlete Fear Avoidance Questionnaire. J Athl Train. 2015;50:634-642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Evans L, Hardy L. Injury rehabilitation: a goal-setting intervention study. Res Q Exerc Sport. 2002;73:310-319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Evans L, Hardy L. Injury rehabilitation: a qualitative follow-up study. Res Q Exerc Sport. 2002;73:320-329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fischerauer SF, Talaei-Khoei M, Bexkens R, Ring DC, Oh LS, Vranceanu A-M. What is the relationship of fear avoidance to physical function and pain intensity in injured athletes? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2018;476:754-763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Glazer DD. Development and preliminary validation of the Injury-Psychological Readiness to Return to Sport (I-PRRS) Scale. J Athl Train. 2009;44:185-189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Heil J. Psychology of Sport Injury. Human Kinetics; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hsu C-J, Meierbachtol A, George SZ, Chmielewski TL. Fear of reinjury in athletes: implications for rehabilitation. Sports Health. 2017;9:162-167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jay K, Brandt M, Jakobsen MD, et al. Ten weeks of physical-cognitive-mindfulness training reduces fear-avoidance beliefs about work-related activity. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95:e3945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Johnson U. Short-term psychological intervention: a study of long-term-injured competitive athletes. J Sport Rehabil. 2000;9:207-218. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Johnston L, Carroll D. The context of emotional responses to athletic injury: a qualitative analysis. J Sport Rehabil. 1998;7:206-220. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kadakia RJ, Tsahakis JM, Issar NM, et al. Health literacy in an orthopedic trauma patient population: a cross-sectional survey of patient comprehension. J Orthop Trauma. 2013;27:467-471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kountz DS. Strategies for improving low health literacy. Postgrad Med. 2009;121:171-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lethem J, Slade PD, Troup JD, Bentley G. Outline of a fear-avoidance model of exaggerated pain perception: I. Behav Res Ther. 1983;21:401-408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. McCall A, Ardern CL, Delecroix B, Abaidia A, Dunlop G, Dupont G. Adding a quick and simple psychological measure of player readiness into the return to play mix: a single player case study from professional football (soccer). Sports Perform Sci Rep. 2017;8:1-3. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Murphy JC, O’Malley E, Gissane C, Blake C. Incidence of injury in Gaelic football: a 4-year prospective study. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40:2113-2120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. O’Connor S, Bruce C, Teahan C, McDermott E, Whyte E. Injuries in collegiate ladies Gaelic footballers: a 2-season prospective cohort study. J Sport Rehabil. Published online May 29, 2020. doi: 10.1123/jsr.2019-0468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. O’Connor S, Leahy R, Whyte E, O’Donovan P, Fortington L. Understanding injuries in the Gaelic sport of camogie: the first national survey of self-reported worst injuries. Int J Athl Ther Train. 2019;24:243-248. [Google Scholar]

- 26. O’Connor S, McCaffrey N, Whyte EF, Moran KA. Epidemiology of injury in male adolescent Gaelic games. J Sci Med Sport. 2016;19:384-388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. O’Connor S, McCaffrey N, Whyte EF, Moran KA. Epidemiology of injury in male collegiate Gaelic footballers in one season. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2017;27:1136-1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. O’Keeffe S, Chéilleachair NN, O’Connor S. Fear avoidance following musculoskeletal injury in male adolescent Gaelic footballers. J Sport Rehabil. 2019;29:413-419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ong LML, de Haes JCJM, Hoos AM, Lammes FB. Doctor-patient communication: a review of the literature. Soc Sci Med. 1995;40:903-918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Podlog L, Banham SM, Wadey R, Hannon JC. Psychological readiness to return to competitive sport following injury: a qualitative study. Sport Psychol. 2015;29:1-14. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ross M, Berger R. Effects of stress inoculation training on athletes’ postsurgical pain and rehabilitation after orthopedic injury. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1996;64:406-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Schwab Reese LM, Pittsinger R, Yang J. Effectiveness of psychological intervention following sport injury. J Sport Health Sci. 2012;1:71-79. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Smith A, Scott S, Wiese D. The psychological effects of sports injuries coping. Sports Med. 1990;9:352-369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]