Abstract

Purpose

A common complication of lumbar puncture (LP) is postural headaches. Epidural blood patches are recommended if patients fail conservative management. Owing to a perceived increase in the number of post-lumbar puncture headaches (PLPHs) requiring epidural blood patches at a regional hospital in our network, the decision was made to switch from 20 to 22 gauge needles for routine diagnostic LPs.

Materials and methods

Patients presenting for LP and myelography at one network regional hospital were included in the study. The patients were contacted by nursing staff 3 days post-procedure; those patients who still had postural headaches after conservative management and received epidural blood patches were considered positive cases. In total, 292 patients were included; 134 underwent LP with 20-gauge needles (53 male, 81 female, average age 57.7) and 158 underwent LP with 22-gauge needles (79 male, 79 female, average age 54.6).

Results

Of 134 patients undergoing LP with 20-gauge needles, 15 (11%) had PLPH requiring epidural blood patch (11 female, 3 male, average age 38). Of 158 patients undergoing LP with 22-gauge needles, only 5 (3%) required epidural blood patches (all female, average age 43). The difference was statistically significant (p < 0.01). Risk factors for PLPH included female gender, younger age, lower body mass index, history of prior PLPH and history of headaches.

Conclusion

Switching from 20-gauge to 22-gauge needles significantly decreased the incidence of PLPH requiring epidural blood patch. Narrower gauge or non-cutting needles should be considered in patients with risk factors for PLPH, allowing for CSF requirements.

Keywords: Lumbar puncture, CSF leak, epidural blood patch, intracranial hypotension

Introduction

A common complication of lumbar puncture (LP) is postural headaches, which is thought to be related to either CSF leak resulting in intracranial hypotension and/or inflammatory response. 1

Conservative treatment (bedrest and hydration) has long been the mainstay for prevention of post-lumbar puncture headaches (PLPH), with epidural blood patches recommended if patients fail conservative management;2–4 however, a number of recent studies have found little difference between early mobilization and bedrest/hydration.5–6 The incidence of PLPH is as high as 32% in some studies.7–9 Needle caliber and tip-design is another area of investigation, and a number of studies have found that smaller caliber needles and non-cutting tip designs may help decrease the incidence of PLPH.10–11

Due to a perceived increase in the number of PLPH requiring epidural blood patches at a regional hospital in our network, the decision was made to switch from 20-gauge Quincke needles to 22-gauge Quincke needles for routine diagnostic LP. In this study, we present data collected in the past 2 years on patients who received LP at our institution, approximately half with 20-gauge needles and half with 22-gauge needles.

Materials and methods

Patients presenting for LP and myelography at one network regional hospital were included in the study. All LPs and myelograms were performed under fluoroscopic guidance by neuroradiologists or physician or radiology assistants. LPs were performed with the bevel of the needle inserted parallel to dural fibers from a right posterior oblique approach. The stylet was replaced before the needle was removed for all LPs. All lumbar punctures in this series were performed with one pass. After the procedure, patients were kept supine (<30 degrees elevation) in the recovery area for 2 hours. At discharge, they were counseled to remain supine (<30 degrees elevation) if they had a postural headache and to maintain good hydration. The patients were subsequently contacted by nursing staff 3 days post-procedure; those patients who still had postural headaches after conservative management and received epidural blood patches were considered positive cases. For patients who had a history of headaches, they were considered positive if the character of headaches was different from their baseline and were postural in nature. Chi-square and Fisher exact probability tests were performed to compare incidences.

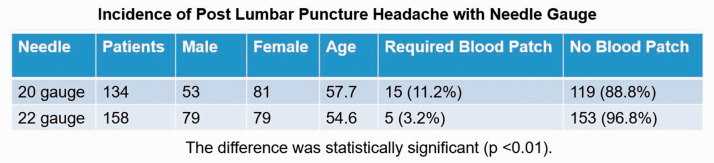

In total, 292 patients that received lumbar punctures from 2018 to 2020 were included in the study; 134 underwent LP with 20-gauge needles (53 male, 81 female, average age 57.7) and 158 underwent LP with 22-gauge needles (79 male, 79 female, average age 54.6) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Patient Demographics and Incidence of Post Lumbar Puncture Headache by Needle Gauge.

Results

Of 134 patients undergoing LP with 20-gauge needles, 15 (11%) had PLPH requiring epidural blood patch (11 female, 3 male, average age 38). Of 158 patients undergoing LP with 22-gauge needles, only 5 (3%) required epidural blood patches (all female, average age 43). The difference was statistically significant (p < 0.01). Risk factors noted in the patients who required epidural blood patches included younger age, documented history of headaches (10), history of prior PLPH (3), normal or below normal body mass index (BMI) (8), and female gender (16). All patients demonstrated significant improvement of symptoms after epidural blood patch with 18 demonstrating complete resolution of symptoms. Successful repeat blood patches were performed on two patients whose symptoms had not completely resolved.

Discussion

Historically, patients receiving lumbar puncture received several hours of bed rest in the recovery area, and bedrest was recommended for the remainder of the day of the procedure. A number of studies have suggested that there is no significant difference in the incidence of PLPH with bedrest when compared to early mobilization. That being said, several studies have found activities that increase intraabdominal pressure such as vigorous exercise could potentially increase the risk of PLPH,12–13 therefore recommending bedrest or only light activity may have clinical utility.

In our study, patients with younger age, female gender, lower BMI, history of headaches, and history of prior PLPH were risk factors that were commonly seen in patients with PLPH, consistent with published data. 14 Additional risk factors for PLPH seen in the literature included increased opening pressure and anxiety about the procedure. 14

Smaller needle caliber and atraumatic tips were associated with lower risk of PLPH in several studies,10–11 as well as our study. The use of smaller caliber and atraumatic needles should be considered when possible. In discussion with physicians, physician assistants and radiology assistants, common situations where larger needle caliber was required included diagnostic and therapeutic high-volume taps for normal pressure hydrocephalus, diagnostic/therapeutic taps for idiopathic intracranial hypertension, patients with challenging anatomy and anxious patients who were not able to remain still during the procedure. Given the increased risk of PLPH in patients with anxiety and increased intracranial pressure, larger caliber atraumatic needles could be considered in this patient cohort given CSF requirements. A small cohort of patients (all female, typically younger with lower BMI, some with history of PLPH) had PLPH even with 22-gauge needle caliber. Needles with 25 or smaller gauge have been successfully used in some series, although manometry, high-volume taps and intrathecal contrast injection with high viscosity agents may be difficult.10–11 The use of even smaller gauge or atraumatic needles should be considered in high-risk patients.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Warren Chang https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1308-5077

References

- 1.Grände PO. Mechanisms behind postspinal headache and brain stem compression following lumbar dural puncture: a physiological approach. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2005; 49(5): 619–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vilming S, Kloster R, Sandvik L. When should an epidural blood patch be performed in postlumbar puncture headache? A theoretical approach based on a cohort of 79 patients. Cephalalgia 2005; 25(7): 523–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Safa-Tisseront V, Thormann F, Malassine P, et al. Effectiveness of epidural blood patch in the management of post-dural puncture headache. Anesthesiology 2001; 95: 334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.So Y, Park J, Lee P, et al. Epidural blood patch for the treatment of spontaneous and iatrogenic orthostatic headache. Pain Physician 2016; 19: E1115–E1122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arevalo-Rodriguez I, Ciapponi A, Roqué i Figuls M, et al. Posture and fluids for preventing post-dural puncture headache. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016; 3(3): CD009199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tejavanija S, Sithinamsuwan P, Sithinamsuwan N, et al. Comparison of prevalence of post-dural puncture headache between six hour supine recumbence and early ambulation after lumbar puncture in Thai patients: a randomized controlled study. J Med Assoc Thai 2006; 89(6): 814–820. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ahmed SV, Jayawarna C.and Jude E. Post lumbar puncture headache: diagnosis and management. Postgrad Med J 2006; 82: 713–716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuntz M, Kokmen E, Stevens J, et al. Post‐lumbar puncture headaches: experience in 501 consecutive procedures. Neurology 1992; 42(10): 1884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mansutti I, Bello A, Calderini AM, et al. Post-dural puncture headache: risk factors, associated variables and interventions. Assist Inferm Ric 2015; 34(3): 134–141. Italian. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arevalo-Rodriguez I, Muñoz L, Godoy-Casasbuenas N, et al. Needle gauge and tip designs for preventing post-dural puncture headache (PDPH). Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017; 4(4): CD010807. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010807.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zorrilla-Vaca A, Mathur V, Wu CL, et al. The impact of spinal needle selection on postdural puncture headache: a meta-analysis and metaregression of randomized studies. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2018; 43(5): 502–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buddeberg BS, Bandschapp O, Girard T. Post-dural puncture headache. Minerva Anestesiol 2019; 85(5): 543–553. doi: 10.23736/S0375-9393.18.13331-1. Epub 2019 Jan 4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gaiser RR. Postdural puncture headache: an evidence-based approach. Anesthesiol Clin 2017; 35(1): 157–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khlebtovsky A, Weitzen S, Steiner I, et al. Risk factors for post lumbar puncture headache. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2015; 131: 78–81. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2015.01.028. Epub 2015 Feb 7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]