Abstract

Introduction

Increasingly more pregnant women are living with pre-existing multimorbidity (≥two long-term physical or mental health conditions). This may adversely affect maternal and offspring outcomes. This study aims to develop a core outcome set (COS) for maternal and offspring outcomes in pregnant women with pre-existing multimorbidity. It is intended for use in observational and interventional studies in all pregnancy settings.

Methods and analysis

We propose a four stage study design: (1) systematic literature search, (2) focus groups, (3) Delphi surveys and (4) consensus group meeting. The study will be conducted from June 2021 to August 2022. First, an initial list of outcomes will be identified through a systematic literature search of reported outcomes in studies of pregnant women with multimorbidity. We will search the Cochrane library, Medline, EMBASE and CINAHL. This will be supplemented with relevant outcomes from published COS for pregnancies and childbirth in general, and multimorbidity. Second, focus groups will be conducted among (1) women with lived experience of managing pre-existing multimorbidity in pregnancy (and/or their partners) and (2) their healthcare/social care professionals to identify outcomes important to them. Third, these initial lists of outcomes will be prioritised through a three-round online Delphi survey using predefined score criteria for consensus. Participants will be invited to suggest additional outcomes that were not included in the initial list. Finally, a consensus meeting using the nominal group technique will be held to agree on the final COS. The stakeholders will include (1) women (and/or their partners) with lived experience of managing multimorbidity in pregnancy, (2) healthcare/social care professionals involved in their care and (3) researchers in this field.

Ethics and dissemination

This study has been approved by the University of Birmingham’s ethical review committee. The final COS will be disseminated through peer-reviewed publication and conferences and to all stakeholders.

Keywords: maternal medicine, public health, preventive medicine

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Core outcome set (COS) development in accordance to the COS standards for development.

Extensive patient, public and stakeholder involvement at each stage.

Pragmatic design to make the COS development feasible in the context of multimorbidity.

The applicability of the COS may be limited to high-income countries.

Responder bias may influence the types of outcomes included in the final COS.

Background

Multimorbidity is a state of having two or more long-term physical or mental health conditions.1 Despite an increase in multimorbidity within the general population,2 there is sparse literature for pregnant women with multimorbidity. Studies in the USA have reported that between 0.8% and 13.9% of hospital births were from women with multiple chronic conditions.3 4 Using a list of 79 chronic conditions, our preliminary study found that one in four pregnant women in the UK had active multimorbidity at conception.5

Studies have shown that multimorbidity is associated with increased risk of adverse obstetric outcomes (eg, preterm birth) and severe maternal morbidities as a consequence of childbirth (eg, hysterectomy and eclampsia).3 4 The 2020 UK national maternal mortality review reported that 90% of women who died within a year of pregnancy had multiple health and social problems.6 The leading direct cause of maternal death included thrombosis, thromboembolism and maternal suicide; leading indirect cause of death included cardiac diseases, epilepsy and stroke.6 In addition to acute complications (eg, eclampsia) and chronic complications (progression from gestational diabetes to type II diabetes) for the mother, evidence suggests that pre-existing maternal morbidities and medications taken for these morbidities can lead to offspring complications such as neurodevelopmental disorders and congenital anomalies.4 7–10 Current observational evidence and interventions focus on single morbidities. There is an urgent need for further understanding of the consequence of pre-existing maternal multimorbidity and development of interventions to improve maternity care for these women.11 12

To facilitate future research studies, a core outcome set (COS) is required. This will standardise the outcomes being reported, allow for evidence synthesis and ensure outcomes important to women, their families, carers and health and social care professionals are captured.13 The importance of COS in women’s health is endorsed by the Core Outcomes in Women’s Health initiative.14 The Core Outcome Measures in Effectiveness Trial (COMET) initiative collates resources for COS development and maintains a COS database.15

A recent scoping review identified 26 COSs relevant to maternity service users, of which 3 were related to pre-existing maternal morbidities in pregnancy (diabetes, epilepsy and infertility).16 A search for COS in pregnancy on the COMET database further identified two published COS (depression and rheumatological conditions) and three in progress (cardiac disease, venous thromboembolism and immune thrombocytopenia).15 There is currently no COS for multimorbidity in pregnancy. We propose a pragmatic study design to develop a COS for observational and interventional studies, for pregnant women with pre-existing multimorbidity, covering obstetrics and maternal and offspring outcomes.

Methods

This study is designed in accordance with the COS standards for development Core Outcome Set-STAndardised Protocol (COS-STAD) recommendations and the protocol follows the COS-STAP statement (online supplemental appendix 1); study findings will be reported following the COS standards for reporting.17–19 The planned start and end dates for the study are June 2021 and August 2022, respectively. The study is registered on the COMET database.20

bmjopen-2020-044919supp001.pdf (58.3KB, pdf)

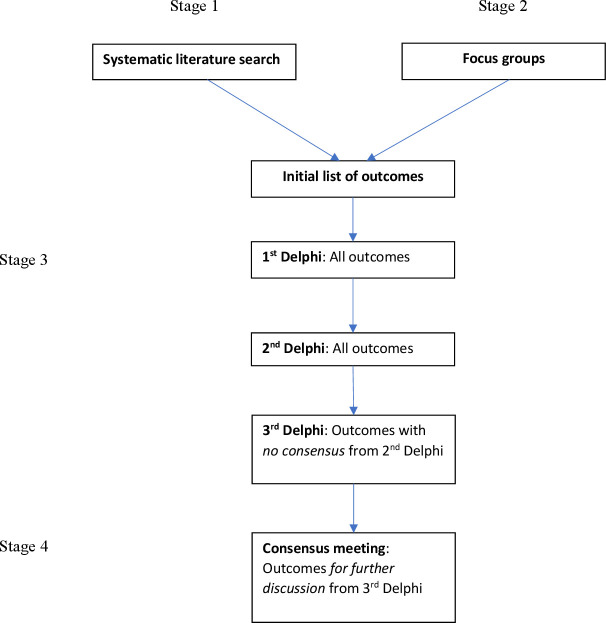

The study will consist of four stages: (1) systematic literature search for reported outcomes for mother and child in studies of pregnant women with multimorbidity; (2) focus groups of women with lived experience of managing pre-existing multimorbidity in pregnancy and/or their partners, and their healthcare/social care professionals; (3) Delphi surveys among stakeholders to prioritise the core outcomes and (4) a consensus meeting to agree on the final COS (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of a core outcome set development method.

Scope of the COS

The population is pregnant women; the exposure is pre-existing multimorbidity, defined as having two or more long-term physical or mental health conditions at conception.1 This does not include pregnancy-related morbidities (eg, gestational diabetes), which will be considered as pregnancy outcomes. The morbidities do not have to be independent of each other. For instance, if a morbidity is a consequence of another morbidity (eg, diabetic eye disease and diabetes), these will be classed as two separate morbidities. The COS will be applicable principally to observational studies but will also inform interventional studies for pregnancy in all settings.

Maternal outcomes will include the antenatal, intrapartum and postpartum period. Offspring outcomes will include the neonatal (first 1 month), infant (first 1 year), prepubertal (2–11 years old), pubertal period (12–18 years old) and adulthood.21 We have included outcomes across the lifespan of the offspring to inform observational studies that take a life-course approach.22 Evidence is emerging that pre-existing maternal morbidities can impact on offspring long-term health in early adulthood.23 Pregnancy outcomes in the rest of this protocol will refer to both maternal and offspring outcomes.

Patient and public involvement

This protocol has been shaped by extensive patient and public involvement (PPI). PPI for this study will be three-tiered: (1) patient representatives in the scientific advisory group (SAG), (2) PPI advisory group and (3) patient and public stakeholders as research participants.

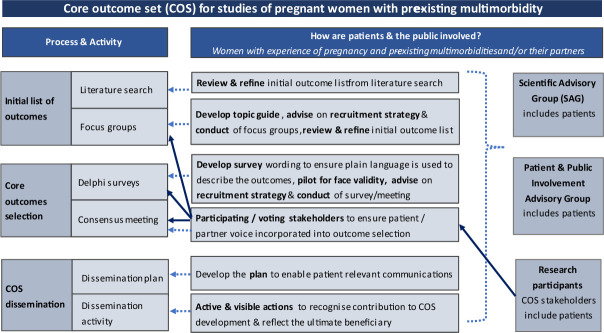

The SAG consists of clinicians (specialists in maternal and fetal medicine, obstetrics, perinatal mental health, general practice and public health), researchers and women representatives collaborating on a larger project studying pregnant women with multimorbidity (MuM-PreDiCT).24 NM, a women representative from the SAG, has advised on the study design, co-authored this protocol and created figure 2 that illustrates the PPI in the COS development.25

Figure 2.

Description of patient and public involvement in the core outcome set development.

Stage 1: systematic literature search

A pragmatic approach to identifying a list of initial outcomes will be adopted given the wide range of potential multimorbidities. We will first identify outcomes from published COS for pregnancy and childbirth and published COS for multimorbidity from the COMET database.26–29 We will then conduct a systematic literature search for reported outcomes in published studies of pregnant women with multimorbidity.

Search strategy

The following databases will be searched: Cochrane library, Medline, EMBASE and CINAHL. Relevant key search terms will include pregnancy (population and maternal outcomes), multimorbidity (exposure) and offspring (offspring outcomes) derived from previous literature.28 30 31

Study selection and data extraction

The inclusion criteria are: systematic reviews, interventional studies, observational studies, qualitative studies and patient-reported outcome measures (PROM) studies; studies reporting pregnancy, maternal and offspring outcomes; and studies of pregnant women with multimorbidity. The exclusion criteria are ongoing studies with no published outcomes, editorials, commentaries, narrative reviews, case reports, case series, diagnostic accuracy studies, laboratory studies and animal studies. No time or language limits will be applied. Full text screening will be conducted by two independent reviewers.

Two reviewers will extract the following data from included studies: author, year of publication, study design, PROM domains, types of outcomes, definition of and measurement tools for the outcomes. Any discrepancy between the two independent reviewers for study selection and data extraction will be resolved with a third reviewer.

Stage 2: focus groups

Outcomes identified in the published literature may represent outcomes considered as important to researchers.13 Therefore, focus groups will be conducted to ensure the capture of outcomes considered as important to women with lived experience of managing pre-existing multimorbidity in pregnancy and/or their carers/partners (two focus groups), and healthcare/social care professionals involved in their care (one focus group). The synergistic discussion in focus groups will allow participants to consider outcomes which are important to others and stimulate in-depth discussions.32

We will aim to include six–eight participants per focus group. Sampling will be purposive and guided by the sampling matrix to provide a broad representation of stakeholders and characteristics (table 1). Recruitment channels are listed in table 2. Involvement of the underserved population will be guided by our PPI advisory group and the MuM-PreDiCT group’s strategy for diverse representation.5

Table 1.

Sampling matrix for the focus groups, Delphi surveys and consensus meeting

| Characteristics | Target/minimum numbers* | ||

| Focus groups | Delphi surveys47 | Consensus meeting | |

| (1) Women with lived experience of managing pre-existing multimorbidity (two or more long-term conditions) in pregnancy | 12–16 | 50 | 5 |

| Physical health conditions | 6 | 8–10 | 1 |

| Mental health conditions | 3–6 | 8–10 | 1 |

| Ethnic minority | 3–6 | 8–10 | 2 |

| Socioeconomically disadvantaged/marginalised groups (eg, homeless, refugee, asylum seeker, drug and alcohol service users, disabled people or victims of domestic abuse)6 |

3–6 | 8–10 | 1 |

| (2) Healthcare/social care professionals | 6–8 | 50 | 5 |

| Obstetric medicine/maternal medicine | 1–2 | 8–10 | 1 |

| Obstetric | 1–2 | 8–10 | 1 |

| Midwifery/antenatal practitioner | 1–2 | 8–10 | 1 |

| Perinatal mental health | 1–2 | 8–10 | 1 |

| Other: for example, primary care, public health, neonatologist, paediatrician, health visitor, commissioner, maternity service provider, social worker, drug and alcohol service provider and maternity advocate/educator | 2 | 8–10 | 1 |

| (3) Researchers Academics, triallist and journal editors (as future implementers) |

– | 5–10 | 2 |

*NB: Target/minimum numbers are estimates. Due to the overlap of characteristics between participants (eg, physical and mental health conditions, healthcare/social care professionals and researchers), we will continuously review the characteristics of participants so that we can identify any underrepresented groups and target recruitment efforts in these areas.

Table 2.

Stakeholders and recruitment channels

| Stakeholder group | Potential recruitment channels48 49 |

| (1) Patient representatives Women with lived experience of managing pre-existing multimorbidity (two or more long-term physical or mental health conditions) in pregnancy and/or their partners/carers |

|

| (2) Healthcare/social care professionals Any healthcare/social care professionals involved in providing multidisciplinary team care for pregnant women: for example, obstetric physicians, obstetricians, physicians, paediatricians, neonatologists, psychiatrists, primary care clinicians, public health professionals, clinicians of established joint antenatal clinics, perinatal mental health team, drug and alcohol services, social services, midwives, health visitors, dieticians, policy-makers and commissioners |

|

| (3) Researchers Academics, triallist and journal editors (as future implementers) |

The SAG’s personal network, social media (Twitter), the COMET and Core Outcomes in Women’s Health (CROWN) network, the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth group, and peer-reviewed journals of obstetric medicine and obstetrics |

COMET, Core Outcome Measures in Effectiveness Trial; SAG, scientific advisory group.

Based on the advice of our PPI advisory group, the focus groups will be held virtually. Participants will be sent participant information sheets in advance of the meeting and consent will be taken 24 hours later either in electronic form or verbally. The focus group will last for 90 min or until no further new ideas are forthcoming. A topic guide will be developed based on previous literature, and with the guidance of qualitative experts and patient representatives in the SAG and our PPI advisory group.33 34 The focus group will be facilitated by a researcher with qualitative methodology training. The focus group discussion will be recorded using the virtual meeting platform, the recordings will be transcribed and imported to NVivo. Data analysis will be inductive, following a structured, multistage approach to thematic analysis.35

Initial list of outcomes

The initial list of outcomes generated from stages 1 and 2 will be reviewed and refined by the SAG and PPI advisory group to combine outcomes that are clinically and pathophysiologically similar to avoid redundancy.13 36 Pregnancy outcomes will be categorised by: (1) maternal or offspring outcomes and (2) by an established taxonomy of outcomes (mortality/survival, physiological/clinical, life impact/functioning, resource use and adverse events/effects).37

Stage 3: Delphi surveys

The Delphi technique collates stakeholder opinions using sequential surveys. The response is summarised and fed back to stakeholders anonymously in subsequent rounds. Stakeholders consider the collective views before re-rating the outcomes. This provides a mechanism to reconcile different opinions to reach a consensus.13 This study will employ a three-round Delphi survey, which is generally sufficient to reach consensus (figure 1).38 Participants will have the opportunity to suggest additional outcomes that were not included in the initial list.

The surveys will be hosted on a secure platform online. The three groups of stakeholders that will be invited to participate and the recruitment channels are outlined in table 2. There is no recommended sample size for Delphi surveys; instead of basing the sample size on statistical power, this is often a pragmatic choice.13 Previous obstetric COS has achieved sample size of around 20–40 for patients and 50–100 for healthcare professionals.36 39–41 To reach the target sample size, snowballing recruitment will be encouraged. To check for representation, the survey will ask for participant characteristics, including types of long-term conditions constituting multimorbidity, age, ethnicity, education level and socioeconomic status (patient representatives, as outlined in table 1), specialty and job roles (healthcare professionals and researchers). Participant’s name and email contact will be included to avoid duplicate entry, for sending up to 2 personalised reminders (1 week apart) and following up on incomplete response. This information will be kept securely, confidentially and separate from the survey responses.

Care will be taken in explaining the concept of COS to lay participants, using supporting materials from the COMET website.15 The wording of the survey will be developed using appropriate language commonly used by representatives in the focus groups. The SAG and PPI advisory group will also ensure that plain language is used to describe the outcomes of interest. Outcomes will be presented in alphabetical order to avoid any response effects related to the order of survey items.13 42

Each outcome will be rated on a 9-point Likert scale: 1–3 (not important), 4–6 (important but not critical) and 7–9 (critically important). An ‘unable to score’ option will be provided to allow for participants who may not have the expertise to score certain outcomes.13 The 9-point Likert scale is commonly used in COS studies and recommended by the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation Working Group.13 43

Score criteria for consensus

Consensus in is when ≥70% of all participants rated 7–9 (critically important) for an outcome.

Consensus out is when≥70% of all participants rated 1–3 (not important) for an outcome.

No consensus is for any other scores.

For further discussion is when: (1) ≥70% of all participants rated 4–6 (important but not critical) for an outcome, or (2) when ≥70% of patient representatives have rated 7–9 for an outcome but consensus in is not reached.44

Pilot study

The survey will be piloted before the Delphi rounds to check face validity. It will also inform the time frame required for completion of each Delphi round.

First Delphi

Participants will be sent a participant information sheet explaining the objectives of the COS study. Completion of the online survey assumes implied consent. Participants will be informed that they can withdraw their response from the study within 1 week of submitting the survey. Once the name and contact details are separated from the survey response, it will not be possible to withdraw their survey response.

At the end of the survey, an open question will invite participants to suggest a maximum of two additional outcomes. If a new outcome is suggested by two or more participants, it will then be added to the second Delphi round. Depending on how many new outcomes that will be presented, this criterion may be modified on a pragmatic basis.

Secound Delphi

Participants who responded to the first Delphi round will be invited to participate in the second Delphi. A summary response from the first Delphi stratified by stakeholder groups will be presented for all outcomes.

Third Delphi

Participants who responded to the second Delphi round will be invited to participate in the third Delphi. Outcomes that reached no consensus will be included as options in the third Delphi survey. A summary response from the second Delphi round stratified by stakeholder groups will also be presented. Attrition rate will be calculated for each subsequent rounds.

Stage 4: consensus meeting

At the time of writing, the UK is undergoing social distancing due to the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition, our SAG patient representative has advised that travelling to meetings may not be convenient for mothers with childcare needs. Therefore, the consensus meeting will be conducted through a virtual platform online.

The consensus meeting panel will be purposefully selected from the SAG, PPI advisory group and Delphi survey respondents to ensure representation of a range of backgrounds. In the third Delphi survey, participants will be asked about their willingness to attend the consensus meeting. For meaningful engagement in the consensus meeting, we will aim for 10–15 participants.13 25 42

An experienced facilitator will be the non-voting chair. Summary scores stratified by stakeholder groups will be presented for outcomes that met the ‘for further discussion’ criteria. Nominal group technique will be used to discuss these outcomes.44 45 Participants will be asked to contemplate independently whether these outcomes should be included. Each participant will be invited to voice their reasoning in turn using a round-robin format to avoid domination of the discussion by selected few. This will be followed by an open discussion, after which a final anonymous binary vote of yes/no will be conducted for each of these outcomes. Outcomes that received ≥70% yes votes will be included in the final COS.

Discussion

The proposed COS will be applicable for observational and interventional studies for pregnant women with pre-existing multimorbidity. Further interventional studies are urgently needed to tackle multimorbidity in pregnancy and reduce the associated adverse outcomes. It is, therefore, important to have a predefined COS to inform future research studies to enable valid comparisons between study findings.

Strength

There is currently no COS for studies of pregnant women with multimorbidity. As multimorbidity covers a wide range of diseases, this presents a unique methodological challenge to the COS development. This study aims to adopt a pragmatic approach to make the task manageable while still following the COS-STAD minimum standards. Inclusion of observational studies in generating the initial list of outcomes may detect rare but important clinical outcomes especially for offspring.46

The Delphi surveys, nominal group technique and anonymous final vote in the consensus meeting will encourage participation of all stakeholders and avoid dominance of selected figures. As outlined in figure 2, PPI will have a meaningful role throughout the COS development to ensure accessibility and relevance to patient stakeholder groups and that patient perspectives are represented in the governance of the COS development.25

To widen its applicability, the proposed COS will include both maternal and offspring outcomes and will include outcomes that are common to all pregnant women with multimorbidity. Finally, by creating this COS, we hope to encourage and facilitate urgently needed research for pregnant women with multimorbidity.

Limitation

The focus groups, Delphi survey and consensus meeting will be conducted in English. Although efforts will be made to encourage international participation, this may limit the generalisability of the findings to high-income countries. The use of online platforms may lead to underrepresentation of the digitally disadvantaged groups. Similarly, responder bias may influence the types of outcomes included in the final COS. To ensure representation of the socially disadvantaged/marginalised group and healthcare/social care professionals with busy work schedules, our approach will be flexible and where necessary/preferred by the participants, we will offer the option of one-to-one interviews instead of focus groups.

As further epidemiological knowledge is gained in identifying common morbidity clusters in pregnant women, the COS may need to be updated to incorporate outcomes specific to these clusters.

Dissemination

The final COS will be fed back to all stakeholders. Patient and public representatives will be encouraged and supported to share the difference they have made. With the guidance of the SAG and the PPI advisory group, a collaborative dissemination plan will be formulated. This will include submitting the findings for publication in a peer-reviewed journal, dissemination at conferences and registering the study on the COMET database.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Twitter: @IngLee17, @ngawai_n, @SineadBr, @nirantharakumar, @maireadblack

K-AE, NM, ST, KN and MB contributed equally.

Contributors: Our authors list includes PPI co-investigators NM and RP. SIL, K-AE, NM, AA-L, AS, AA, BT, CN-P, CY, CM, DOR, HH, JK, KMA, LL, PB, RP, SB, UA, ST, KN and MB conceived the study, contributed to the study design, critically reviewed and revised the protocol drafts, agreed on the final draft manuscript for submission and are accountable for all aspects of the work. SIL led the development of the protocol and drafted the initial manuscript with contribution and supervision from KN, ST, MB, K-AE. LL, BT and MB contributed to the qualitative element of the study design and, together with NM, RP, SB and KMA, advised on the recruitment channels; PPI co-investigator NM designed figure 2.

Funding: This work was supported by Medical Research Council consolidator grant (grant number: MR/V005243/1).

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

References

- 1.The Academy of Medical Sciences . Multimorbidity: a prority for global health research, 2018. Available: https://acmedsci.ac.uk/file-download/99630838

- 2.Whitty CJM, MacEwen C, Goddard A, et al. Rising to the challenge of multimorbidity. BMJ 2020;368:l6964. 10.1136/bmj.l6964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Admon LK, Winkelman TNA, Heisler M, et al. Obstetric outcomes and delivery-related health care utilization and costs among pregnant women with multiple chronic conditions. Prev Chronic Dis 2018;15:E21. 10.5888/pcd15.170397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown CC, Adams CE, George KE, et al. Associations between comorbidities and severe maternal morbidity. Obstet Gynecol 2020;136:892–901. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.MuM-PreDiCT . MuM-PreDiCT resources: research documents, 2021. Available: https://mumpredict.org/portfolio/shared-findings/

- 6.Knight M, Bunch K, Tuffnell D. Saving lives, improving mothers’ care - lessons learned to inform maternity care from the uk and ireland confidential enquiries into maternal deaths and morbidity 2016-18. Oxford: National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit, University of Oxford, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen S, Zhao S, Dalman C, et al. Association of maternal diabetes with neurodevelopmental disorders: autism spectrum disorders, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and intellectual disability. Int J Epidemiol 2021;50:459–74. 10.1093/ije/dyaa212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Han VX, Patel S, Jones HF, et al. Maternal acute and chronic inflammation in pregnancy is associated with common neurodevelopmental disorders: a systematic review. Transl Psychiatry 2021;11:71. 10.1038/s41398-021-01198-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tomson T, Battino D, Bonizzoni E, et al. Comparative risk of major congenital malformations with eight different antiepileptic drugs: a prospective cohort study of the EURAP registry. Lancet Neurol 2018;17:530–8. 10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30107-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vounzoulaki E, Khunti K, Abner SC, et al. Progression to type 2 diabetes in women with a known history of gestational diabetes: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2020;369:m1361. 10.1136/bmj.m1361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beeson JG, Homer CSE, Morgan C, et al. Multiple morbidities in pregnancy: time for research, innovation, and action. PLoS Med 2018;15:e1002665. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Knight M, Tuffnell D, Kenyon S. Saving lives, improving mothers’ care - surveillance of maternal deaths in the UK 2011-13 and lessons learned to inform maternity care from the UK and Ireland Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths and Morbidity 2009-13. Oxford: National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit, University of Oxford, 2015. https://www.npeu.ox.ac.uk/mbrrace-uk/presentations/saving-lives-improving-mothers-care#saving-lives-improving-mothers-care-surveillance-of-maternal-deaths-in-the-uk-2011-13-and-lessons-learned-to-inform-maternity-care-from-the-uk-and-ireland-confidential-enquiries-into-maternal-deaths-and-morbidity-2009-13 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Williamson PR, Altman DG, Bagley H, et al. The comet Handbook: version 1.0. Trials 2017;18:280–80. 10.1186/s13063-017-1978-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.CROWN . Core outcome in women’s and newborn health, 2020. Available: http://www.crown-initiative.org/core-outcome-sets/

- 15.Comet initiative . Core outcome measures in effectiveness trials, 2020. Available: http://www.comet-initiative.org/

- 16.Slavin V, Creedy DK, Gamble J. Core outcome sets relevant to maternity service users: a scoping review. J Midwifery Womens Health 2021;66:185–202. 10.1111/jmwh.13195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kirkham JJ, Davis K, Altman DG, et al. Core outcome Set-STAndards for development: the COS-STAD recommendations. PLoS Med 2017;14:e1002447. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kirkham JJ, Gorst S, Altman DG, et al. Core outcome Set-STAndardised protocol items: the COS-STAP statement. Trials 2019;20:116. 10.1186/s13063-019-3230-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kirkham JJ, Gorst S, Altman DG, et al. Core outcome Set-STAndards for reporting: the COS-STAR statement. PLoS Med 2016;13:e1002148. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.COMET Database . Core outcome set for studies of pregnancy affected by multimorbidity, 2020. Available: https://cometinitiative.org/Studies/Details/1724

- 21.Williams K, Thomson D, Seto I, et al. Standard 6: age groups for pediatric trials. Pediatrics 2012;129 Suppl 3:S153–60. 10.1542/peds.2012-0055I [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jacob CM, Baird J, Barker M, et al. The importance of a life course approach to health: chronic disease risk from preconception through adolescence and adulthood, 2021. Available: https://www.who.int/life-course/publications/life-course-approach-to-health.pdf?ua=1

- 23.Yu Y, Arah OA, Liew Z, et al. Maternal diabetes during pregnancy and early onset of cardiovascular disease in offspring: population based cohort study with 40 years of follow-up. BMJ 2019;367:l6398. 10.1136/bmj.l6398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.MuM-PreDiCT . Multimorbidity and pregnancy: determinants, clusters, consequences and trajectories 2020, 2020. Available: https://mumpredict.org/

- 25.Moss N, Daru J, Lanz D, et al. Involving pregnant women, mothers and members of the public to improve the quality of women’s health research. BJOG: Int J Obstet Gy 2017;124:362–5. 10.1111/1471-0528.14419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nijagal MA, Wissig S, Stowell C, et al. Standardized outcome measures for pregnancy and childbirth, an ICHOM proposal. BMC Health Serv Res 2018;18:953. 10.1186/s12913-018-3732-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Devane D, Begley CM, Clarke M, et al. Evaluating maternity care: a core set of outcome measures. Birth 2007;34:164–72. 10.1111/j.1523-536X.2006.00145.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Herman D, Lor KY, Qadree A, et al. Composite adverse outcomes in obstetric studies: a systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2021;21:107. 10.1186/s12884-021-03588-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith SM, Wallace E, Salisbury C, et al. A core outcome set for multimorbidity research (COSmm). Ann Fam Med 2018;16:132–8. 10.1370/afm.2178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.ISS H, Guthrie B, Hodgins P. A systematic review of international studies on multimorbidity measures. Prospero 2020 CRD42020172409, 2020. Available: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=172409

- 31.Brouwer ME, Williams AD, van Grinsven SE, et al. Offspring outcomes after prenatal interventions for common mental disorders: a meta-analysis. BMC Med 2018;16:208. 10.1186/s12916-018-1192-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Keeley T, Williamson P, Callery P, et al. The use of qualitative methods to inform Delphi surveys in core outcome set development. Trials 2016;17:230. 10.1186/s13063-016-1356-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Retzer A, Sayers R, Pinfold V, et al. Development of a core outcome set for use in community-based bipolar trials-A qualitative study and modified Delphi. PLoS One 2020;15:e0240518. 10.1371/journal.pone.0240518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Viau-Lapointe J, D'Souza R, Rose L, et al. Development of a core outcome set for research on critically ill obstetric patients: a study protocol. Obstet Med 2018;11:132–6. 10.1177/1753495X18772996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006;3:77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Al Wattar BH, Tamilselvan K, Khan R, et al. Development of a core outcome set for epilepsy in pregnancy (E-CORE): a national multi-stakeholder modified Delphi consensus study. BJOG 2017;124:661–7. 10.1111/1471-0528.14430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dodd S, Clarke M, Becker L, et al. A taxonomy has been developed for outcomes in medical research to help improve knowledge discovery. J Clin Epidemiol 2018;96:84–92. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.12.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Custer RL, Scarcella JA, Stewart BR. The Modified Delphi Technique - A Rotational Modification. Journal of Career and Technical Education 1999;15:1–10. 10.21061/jcte.v15i2.702 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Swedish Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Assessment of Social Services . Development of a core outcome set (COS) for treatment of depression during or after pregnancy (antenatal and postpartum depression), 2020. Available: https://www.sbu.se/314e

- 40.Egan AM, Bogdanet D, Griffin TP, et al. A core outcome set for studies of gestational diabetes mellitus prevention and treatment. Diabetologia 2020;63:1120–7. 10.1007/s00125-020-05123-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Egan AM, Galjaard S, Maresh MJA, et al. A core outcome set for studies evaluating the effectiveness of prepregnancy care for women with pregestational diabetes. Diabetologia 2017;60:1190–6. 10.1007/s00125-017-4277-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Egan AM, Dunne FP, Biesty LM, et al. Gestational diabetes prevention and treatment: a protocol for developing core outcome sets. BMJ Open 2019;9:e030574–e74. 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-030574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.GRADE . Grade handbook: 3. selecting and rating the importance of outcomes, 2013. Available: https://gdt.gradepro.org/app/handbook/handbook.html

- 44.D'Souza R, Villani L, Hall C, et al. Core outcome set for studies on pregnant women with vasa previa (COVasP): a study protocol. BMJ Open 2020;10:e034018. 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-034018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Murphy MK, Black NA, Lamping DL, et al. Consensus development methods, and their use in clinical Guideline development. Health Technol Assess 1998;2:1–88. 10.3310/hta2030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Williamson PR, Altman DG, Blazeby JM, et al. Developing core outcome sets for clinical trials: issues to consider. Trials 2012;13:132. 10.1186/1745-6215-13-132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Harman NL, Bruce IA, Callery P, et al. MOMENT-management of otitis media with effusion in cleft palate: protocol for a systematic review of the literature and identification of a core outcome set using a Delphi survey. Trials 2013;14:70. 10.1186/1745-6215-14-70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Centre for BME Health . Toolkits. increasing participation of black Asian and minority ethnic (BamE) groups in health and social care research, 2021. Available: https://centreforbmehealth.org.uk/resources/toolkits/

- 49.National Institute for Health Research . Improving inclusion of under-served groups in clinical research: guidance from include project. v1.0, 2020. Available: https://www.nihr.ac.uk/documents/improving-inclusion-of-under-served-groups-in-clinical-research-guidance-from-include-project/25435

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2020-044919supp001.pdf (58.3KB, pdf)